Abstract

Materials typically experience serious microstructure and performance degradations under irradiation in nuclear reactors. To explore radiation-resistant metals with high design flexibility is urgently requested for the safe application of nuclear energy. In this work, we discover an anti-radiation mechanism for this purpose in a gradient nanostructured nuclear grade austenitic stainless steel prepared by a flexible surface nano-crystallization approach. A special 3-dimensional microstructure network, consisting of low-energy grain boundaries, stacking faults, and dislocation networks, is introduced in the nanostructure, so that a large-scale adaptive martensitic transformation mechanism is activated under irradiation even at extremely high radiation doses and high temperatures. Consequently, the radiation resistance is significantly enhanced, while a superior mechanical property is retained, in nanostructured samples compared to coarse-grained counterparts. Results presented in this work thus explore a strategy to prepare radiation-resistant metals in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear energy has received worldwide attention in past decades as a powerful source to solve energy and environmental problems on our planet. To use nuclear energy in a secure manner, the structural materials have to be reliable during their service in nuclear reactors. Moreover, the requirement of extending the life of existing nuclear power plants means much longer service time of materials under the extreme radiation environment in future1,2,3,4,5,6. Therefore, structural materials with enhanced radiation resistance are expected to be developed, and researchers have committed to this issue in recent years. For example, the role of grain boundaries (GBs) to increase radiation resistance has been revealed by experiments and simulations7,8,9. Inspired by such works, decreasing radiation defects by a high density of GBs has been intensively investigated with the development of nanocrystalline (NC) materials10. However, some results insisted that the improvement by GB trapping defects is limited in NC materials, mostly due to the distinct grain growth even under low radiation doses11,12,13. In addition, trapping radiation defects by interfaces between nanosized particles and matrix has become a promising method recently, represented by developing oxide dispersion-strengthened steels14. But this method is limited by its low production efficiency and low batch stability. Similarly, single-phase concentrated solid-solution alloys (e.g., high-entropy alloys, HEAs) have also been suggested to exhibit high radiation resistance15, but their applications are limited by high cost and low stability at high temperatures and high doses16.

It is noted that enhancing radiation resistance means not only decreasing the density of radiation defects but also maintaining the excellent service performance of materials. The local microstructure around interfaces would be changed by absorbing radiation defects, seriously degrading the mechanical properties of materials and leading into failure during service in reactors17,18,19. Therefore, adjusting strategy by controlling both mechanical properties and radiation defect density is crucial to the development of advanced nuclear structural materials. For example, a self-healing approach was introduced in a HEA with transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) effect by balancing radiation induced martensitic transformation with temperature induced reverse transformation, so that a high stability of mechanical properties was achieved in the material under irradiation20.

In this work, through experiments and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we discovered that a gradient nanostructured (GNS) austenitic stainless steel exhibits an extraordinary radiation resistance, including decreased radiation defects and enhanced mechanical properties, even under extremely high radiation doses and high temperatures. Moreover, a novel anti-radiation mechanism through a large-scale phase transformation has been proposed and confirmed.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and microstructure

We used a commercial nuclear grade 304 austenitic stainless steel (304NG), which is widely used in current nuclear reactors and considered as candidate material in future reactors, mostly due to the outstanding performance of mechanical properties, high-temperature resistance, and corrosion resistance, and processed plate samples by using surface mechanical rolling treatment (SMRT) to introduce a GNS surface layer. Both GNS and coarse-grained (CG) samples underwent simultaneous iron ion radiation procedures on a same sample holder, with the maximum radiation dose up to 155 displacements per atom (dpa). Accordingly, the ion implantation range is within 0−4.7 μm while the peak damage is at ~3.96 μm in irradiated samples. Details can be found in “Methods”, Supplementary Figs. 1–4 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. It is noted that ion implantation experiments are highly valuable for understanding fundamental aspects of radiation effects as the 1st step to explore radiation resistant materials under extreme radiation environments, considering the cost, time and protection needed against radiation in neutron irradiations21,22.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations reveal that the surface layer to endure the peak radiation damage consists of lath structure with an average transversal size of 37 ± 13 nm in as-prepared GNS sample (Fig. 1a, b). Through transmission Kikuchi diffraction (TKD) measurements (Fig. 1c), we found that the dominant interfaces between laths are Σ3 (111) GBs and low-angle GBs (LAGBs). Further characterizations by using scanning TEM (STEM) indicate that a few intersecting stacking faults (SFs, with a density of ~7.5 × 1014m−2) are emitted from the GBs into the laths (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 5). Meanwhile, numerous dislocation networks (DNs, as marked in Fig. 1d) exist in the grains. This feature is also revealed by a 3-dimensional (3D) model constructed at atomic scale by simulating SMRT in 304NG (Fig. 1e).

a A cross-sectional TEM image in the near-surface layer. b, c TKD analysis in the boxed zone in (a): b An inverse pole figure, and c a distribution map of GB characters. d A lath structure with delivery SFs (pointed by orange arrows) emitted from GBs and intertwined DNs (pointed by blue arrows). e A 3D atomic model showing the formation of numerous SFs, interfaces, and DNs in a GNS material simulating 304NG (Supplementary Note 1). In (c): red lines, Σ3 (111) GBs; blue lines, LAGBs (5° to 15°); other colored lines, other GBs. In (e), the green, pink, yellow, and blue lines denoting 1/6〈112〉 (Shockley), 1/6〈110〉 (Stair-rod), 1/3〈100〉 (Hirth), and 1/2〈110〉 (Perfect) dislocations, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Radiation induced defects formation

In metals under irradiation, dislocation loops (DLs) are one kind of key defect structures in understanding the resulted properties (e.g., creep, swelling, hardening, and fatigue). Therefore, the density and size of DLs are typically used to estimate the radiation damages in materials under irradiation at low temperatures23,24. In this work, a high density of DLs forms in irradiated CG samples while no remarkable DLs form in irradiated GNS samples even at an extremely high dose of 155 dpa at room temperature, as shown in Fig. 2a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 6. Meanwhile, it is noticed that the mean grain size is still in the nanometer scale in irradiated GNS samples, and distinct martensitic transformation occurs in both groups of samples (as reflected by the increasing diffraction intensity of martensite in the corresponding SAED patterns).

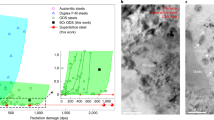

a, b TEM images of the peak damage regions in irradiated a CG and b GNS samples at a dose of 155 dpa. The insets show the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns, in which both austenite (γ) and martensite (α′) are indexed (with more details in Supplementary Fig. 19). c Variations of DLs density and size with radiation dose in CG and GNS samples (Data presented as mean ± SD, N ≥ 3), determined by TEM BF and WBDF observations as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7. And Supplementary Fig. 8 provides an enlarged plot showing the situation at low doses (< 10 dpa). d Correlations of specific radiation defects density (ρNC/ρCG) and radiation dose in different materials due to the formation of nanostructures. The corresponding materials and DLs densities are provided in Supplementary Fig. 9. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To quantify the evolution of defects under irradiation, all the irradiated samples were carefully analyzed by combining TEM bright-field (BF) and weak-beam dark-field (WBDF) observations (Supplementary Fig. 7). Subsequently, the correlations of the density and size of DLs with radiation dose are summarized in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 3. We can see both the mean density and size of DLs (and the corresponding uncertainties) in irradiated GNS samples are typically much lower than those in irradiated CG counterparts at doses >5 dpa. For example, the density is (5.96 ± 0.53) × 1020m−3 and the diameter is 4.69 ± 0.78 nm for DLs in GNS sample at 155 dpa. The mean values are only ~3.8% and ~63%, respectively, of those in CG counterpart after the same irradiation. Meanwhile, the density and size of DLs significantly decrease with increasing dose within the early stage (2–10 dpa, see Supplementary Fig. 8) in irradiated GNS samples, possibly due to the evolution from faulted loops (e.g., 1/3 <111> loops in austenite) to unfaulted loops (e.g., 1/2 <111> loops in martensite). It is interesting to notice this trend is very different from that both the density and size of radiation defects significantly increase with increasing dose within the early stage in irradiated CG counterparts in this work, as well as in other irradiated materials (including nanostructured and CG) reported in previous works25,26,27,28,29,30.

Since the formation of radiation defects depends on material compositions and radiation conditions, and an enhanced radiation resistance is typically reflected by a lower defect density, thus, the ratio of radiation defects density in a NC material to that in its CG counterpart (i.e., specific radiation defects density, ρNC/ρCG) under a same irradiation process can be used to reflect the increment of radiation resistance by forming nanostructures in different alloys. As shown in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 9, the specific radiation defects density in GNS 304NG is much lower than those in other kinds of NC materials under a similar radiation condition. Although the ratio in nano-twinned Ag is also low (~ 0.22) at a low dose (0.12 dpa), it increases rapidly with increasing dose26, possibly due to its low microstructure stability under irradiation. In comparison, the specific radiation defects density of GNS 304NG decreases gradually with increasing dose and reaches ~0.038 at 155 dpa, even lower than that in T91 steel, which is widely used in structural components (such as pressure vessels, pipes and power boilers) in current nuclear reactors27.

In addition to a significantly enhanced radiation resistance to the formation of DLs at room temperature, an enhanced radiation resistance to the formation of voids, which are also a typical kind of recombined radiation-induced defects, has been observed in GNS 304NG samples at high temperatures. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, a large number of voids forms in CG samples after a radiation dose of ~80 dpa at 450 °C, while voids can be rarely observed in GNS counterparts.

Anti-radiation mechanisms

So, what mechanisms enable GNS 304NG steel to achieve such an excellent irradiation tolerance? One should be its specific nanostructures with a high stability. Conventionally, refining microstructure leads to an enhanced radiation resistance, mostly due to the existence of numerous GBs acting as sinks of radiation-induced defects10. However, the instability of refined microstructure is an Achilles heel of traditional NC materials under irradiation, mostly due to the high stored energy of GBs in them. In this work, Σ3 (111) GBs are massively formed in the GNS surface layer. They are typically very stable under heating or irradiation, mostly due to the low stored interfacial energy10,31. Meanwhile, numerous SFs and partial dislocations are formed and possibly lead into a distinct relaxation of GBs32. And they might also promote the annihilation of radiation-induced defects inside grains and reduce GB migration under irradiation (as discussed later). Moreover, the dislocation lines form a 3D network, which might reduce GB migration not only by absorbing radiation-induced defects inside grains but also by interacting with GBs and forming strangleholds on them33. Therefore, such a special microstructure (combining low-energy interfaces, SFs, and DNs) contributes to a high stability from both thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives. And this point has also been confirmed by MD simulations (see Supplementary Note 1). Therefore, the grain size is still within nanometer scale at a very high radiation dose (e.g., 86 ± 26 nm after 155 dpa, see Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 6) at room temperature, or even after irradiation at a high-temperature (e.g., 72 ± 32 nm after 80 dpa at 450 °C, see Supplementary Fig. 10). Meanwhile, the GBs are still mainly composed of low energy ones such as Σ3 interfaces and LAGBs in irradiated GNS samples (Supplementary Fig. 11).

As mentioned earlier, the DLs density significantly decreases with increasing dose from 2 to 10 dpa in the peak damage regions in different irradiated GNS samples (see Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 8). In addition, the decreasing DLs density with increasing dose was also observed in a same irradiated GNS 304NG sample (see Supplementary Fig. 12). In contrast, the DLs density increases with increasing dose in CG counterparts in this work, as well as in other materials under irradiation25,26,27,28,29,30. Therefore, we believe that there should be a more important anti-radiation mechanism in GNS 304NG.

Martensitic transformation occurs in both GNS and CG samples under irradiation, but with totally different features. In the peak damage region in GNS samples, the fraction of martensitic phase increases from ~10% to ~50% after an irradiation of 5 dpa (Supplementary Fig. 13), and reaches almost a complete distribution after 12 dpa (Supplementary Fig. 6) at room temperature. In contrast, a large fraction of austenitic phase is still retained in the peak damage region in irradiated CG samples even after a much higher dose of 155 dpa (Fig. 2a). Therefore, the martensitic transformation occurs much faster and in a broader region in GNS samples than in CG samples in the early irradiation stage. Furthermore, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses reveal that the martensite content increases gradually with dose in irradiated GNS samples, while it is almost constant in irradiated CG samples (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 14). It is noted that the XRD results should reflect the mean phase information in a surface layer of ~5 μm in thickness (larger than the irradiated thickness) due to the absorption of X-ray in the steels34, so that the martensite volume fraction values obtained by XRD (see Fig. 3a) are lower than those obtained by SAED and TKD in peak damage regions (see Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 13). Combining the results obtained by SAED, TKD, and XRD, we can see that the martensitic phase transformation should occur only in the peak damage region in irradiated CG samples at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 6i), while it should occur almost in the entire irradiated region in GNS counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 6j). Moreover, almost no martensite transformation is observed in irradiated CG samples at high temperatures (e.g., 450 °C), while it still occurs vastly in irradiated GNS counterparts, as demonstrated by comparing the corresponding SAED patterns in Supplementary Fig.10. Therefore, an unexpected novel large-scale adaptive martensitic transformation (AMT) from the peak damage region to the surrounding regions in GNS 304NG under irradiation can be suggested for the 1st time. In brief, the AMT process is different from the conventional martensitic transformation process in CG austenitic stainless steels under irradiation in that the AMT process occurs faster, progresses adaptively from the peak damage region to the surrounding regions, and can be activated at high temperatures.

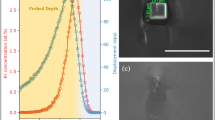

a Variations of α′ fraction (determined by XRD) as a function of radiation dose in GNS and CG samples. The α′ fraction values should reflect the mean volume fractions of martensite in the surface layer of ~5 μm in thickness. b A high-resolution STEM image of GNS sample at a dose of ~2 dpa. The inset shows the fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern of the white boxed area with complete γ phase. c A magnified view of the orange boxed area in (b), showing the transformation in the lattice arrangement from γ to α′ phase. The inset shows the FFT pattern of γ and α′ mixture, indicating the formation of α′ near SFs. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Mostly due to their lower packing densities, body centered cubic (BCC) metals are typically more resistant to radiation damages than face centered cubic (FCC) metals1,10,35. Therefore, the radiation resistance is expected to be enhanced in GNS 304NG after martensitic transformation. In this work, an unexpected contribution is further provided to the extraordinary radiation resistance during the large-scale AMT process itself. As revealed in Supplementary Fig. 15, in comparison with GNS 304 samples, which possess a similar grain size distribution but much larger initial martensite fraction36, the DLs densities in GNS 304NG samples are lower at doses >6 dpa, although they are higher at ~1 dpa mostly due to a much smaller martensite fraction.

In fact, radiation induced martensitic transformation has been observed in such materials as austenitic stainless steels18,19, titanium alloys37, and TRIP alloys20 previously, but much higher radiation doses are required to initiate the transformation. In this work, a significant increase in martensite content is observed in GNS samples under low radiation doses of 1−2 dpa at room temperature. Further characterizations by high-resolution STEM show that the lattice arrangement changes near SFs at first (Fig. 3b, c), implying that the interactions between pre-existing SFs and radiation-induced defects boost the martensitic transformation. Therefore, the excess free energies relating with SFs and radiation-induced defects might provide a primary driving force for martensitic transformation, and the existence of numerous SFs should promote the AMT process widely in GNS 304NG. Meanwhile, no chemical segregation or variation can be detected after phase transformation (Supplementary Fig. 16), confirming that the radiation induced phase transformation should be a process without long-range mass diffusion or implanted ions (due to radiation). Further MD simulations (see Supplementary Note 1) demonstrate that the mechanism of martensitic transformation is dominated by interactions between SFs and radiation-induced defects in irradiated GNS 304NG. And transformation is a 2-step process, conforming to the classical Kurdjumov-Sachs relationship. It is noted that only the BCC (α’) martensitic phase was observed by both TEM and XRD in this work, although the hexagonal close-packed (HCP, ε) martensitic phase might also be evolved from overlapping bundles of SFs on {111} planes in principle38,39. Since lattice rearrangement occurs during phase transformation and might consume a large number of radiation-induced defects, the radiation resistance is therefore significantly enhanced. This agrees with that the GNS 304NG samples show higher radiation resistance than GNS 304 counterparts at doses >6 dpa (Supplementary Fig. 15), when the AMT mechanism is active in the irradiation affected range in GNS 304NG (see Fig. 3a), but the fraction of formed martensite is still much lower than that in GNS 304 (near 100%).

Typically, higher compressive residual stresses are introduced in the surface layer by SMRT36, which might promote the AMT process by decreasing the energy barrier of martensitic transformation. In this work, the large-scale AMT and enhanced irradiation resistance still occur in GNS samples at higher temperatures (e.g., 450 °C), when the residual stresses are almost completely released. Therefore, it should be SFs playing the dominant role in the AMT process in GNS 304NG. This point has been clarified by MD simulations of AMT mechanism (Supplementary Note 1). However, it is noted that stresses were introduced to accelerate the martensitic transformation during MD simulations in this work. And changes in residual stresses might occur after irradiation at room temperature. Therefore, further investigations are expected to clarify the relationship between residual stress and the AMT process under irradiation, especially at room temperature.

Mechanical properties

Generally, the new phases are isolated and in-homogeneously distributed in the parent phases in normal austenitic stainless steels after radiation induced martensitic transformation. They will cause stress concentration and result in significant degradations in mechanical properties, e.g., ductility, fatigue, and creep resistance18,19,37,40. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, irradiated CG samples exhibit typical radiation induced surface hardening, i.e., the hardness is markedly raised at the top surface (from ~2.31 GPa to ~4.37 GPa, ΔH/HI ~ 0.89, according to the nanoindentation results) and then decreases sharply along depth after radiation. In comparison, although the surface hardness of GNS samples is also raised (from ~4.93 GPa to ~6.45 GPa, ΔH/HI ~ 0.31) after radiation, the hardening trend is lower and occurs in a much broader region. This should be benefited by the excellent coordinated deformation ability of GNS36,41,42, as well as the large-scale AMT in the surface layer. From previous studies, the sharp surface hardening is typically prone to induce surface embrittlement43,44, while the gradient hardness distribution in a thicker surface layer is expected to result in superior mechanical properties41,42,45.

a Indentation displacement dependence of hardness during nanoindentation tests (Data presented as mean ± SD, N ≥ 5). b Distribution of hardness along depth derived by cross-sectional microhardness tests on GNS and CG samples before and after irradiation (Data presented as mean ± SD, N = 3). The nanoindentation tests were performed on sample surfaces from a planar-view. And the microhardness tests were performed on cross-sectional samples (Supplementary Fig. 3). c Correlations of normalized hardness (H/HI) and depth in GNS and CG samples after irradiation. H and HI denote hardness (or microhardness) measured at a same depth in samples after and before irradiation, respectively. The surface hardness of a sample was estimated from (a) according to the Nix-Gao correction model, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 17. d, e SEM snapshots of micropillars under compression to different engineering strains for GNS samples (d) before and (e) after irradiation, respectively. The solid and doted lines mark two series of major slip traces. The pillar upside is the SMRT/irradiated surface. f Engineering stress-strain curves of micropillar compression tests in (d, e). The compression process of the irradiated GNS sample is shown in Supplementary Video 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As demonstrated by micropillar compression tests (Fig. 4d, f), distinct slip traces form on GNS samples after irradiation at room temperature, which are similar to those form on GNS samples before irradiation, and no fracture occurs after a compression strain to ~22%. These indicate that no surface embrittlement occurs in irradiated GNS samples. Since a high fraction of martensite grains has formed in the surface layer of irradiated GNS samples, we can infer that the radiation induced large-scale AMT process should not degrade the mechanical properties of 304NG. In fact, outstanding mechanical properties, including superior strength-ductility synergy and fatigue resistance, have been observed in GNS austenitic stainless steels (316 L and 304) previously, in which the surface layer is mostly composed of deformation-induced martensitic nano-grains36,46. Thus, this work indicates the special microstructure of GNS (including numerous Σ3 GBs, SFs, and DNs) explores a beneficial martensitic phase transformation under irradiation, which not only decreases the number of radiation defects but also improves the mechanical properties of steels served in reactors.

In summary, a strategy to develop radiation resistant steels with high design flexibility could greatly promote the safe application of nuclear energy. In this work, we discovered a novel radiation induced large-scale AMT mechanism in GNS 304NG with a high density of SFs, Σ3 GBs, and LAGBs (prepared by surface nano-crystallization technologies47 which are low cost and possess high design flexibility, see Supplementary Fig. 18). The AMT mechanism keeps effective under irradiation from low doses to extremely high doses, from low temperatures to high temperatures. The introduction of large-scale AMT changes the detrimental martensitic transformation into a beneficial process under irradiation for the first time, which develops a steel with strong radiation resistance. Therefore, the surface nano-crystallization technique and AMT mechanism present brilliant application potentialities in reactors, especially for core components under high irradiation doses and dose rates. Furthermore, since radiation induced martensitic transformation might occur in different metals such as austenitic stainless steels, titanium alloys, and TRIP alloys, this work provides a novel way to develop super-metals with high radiation resistance to be used in current and future nuclear facilities.

Methods

Samples fabrication

In this work, a nuclear grade austenitic stainless steel 304 (304NG) was studied. As-received plate samples were in a cold-rolled state with a microhardness of ~2.0 GPa. Its chemical composition was (in wt.%) 19.51Cr, 8.87Ni, 1.73Mn, 0.27Si, 0.021 P, 0.04 C, and balance Fe. The initial microstructure consisted of equiaxed grains (around 93% austenite and 7% martensite) with an average size of ~26 ± 10 μm and few deformation twins (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, few dislocations and SFs existed in the grains.

GNS layer with a thickness of ~700 μm was in-situ produced on the surface of 304NG plates by surface mechanical rolling treatment (SMRT). The processing of SMRT has been illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2a. During SMRT, a polished WC/Co ball of 8.0 mm in diameter was pressed into the plate surface with a depth of ap and rolled on the surface along the y direction at a velocity of vy. Subsequently, the ball moved along the x direction at a per step distance of Px and repeated the rolling process. The processing parameters of SMRT in the present work are listed in Supplementary Table 1. It is noted that SMRT is a method implementing severe plastic deformation at the material surface. However, SMRT typically applies higher strain and strain rates in the surface layer, and it shows advantages of low cost and high flexibility in processing large-sized components, compared to conventional severe plastic deformation methods such as equal channel angular pressing and high-pressure torsion1,2,9.

After SMRT, these samples were cut into squares (10 × 10 × 1.9 mm3) by wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM). And then electrolytic polishing (in 10% perchloric acid alcohol solution, 20 V, −20 °C, 45 s) was used to remove a surface layer of ~2 μm in thickness from the treated surface, to exclude any possible surface contamination during the sample processing. Finally, GNS 304NG samples were obtained, as revealed in Supplementary Fig. 3. Meanwhile, as-received samples were also cut into squares (10 × 10 × 1.9 mm3) by WEDM. Subsequently, they were successively polished by using 400, 800, and 2000 grit emery papers, followed by electrolytic polishing (in 10% perchloric acid alcohol solution, 20 V, −20 °C, 90 s). Thus, CG counterparts were prepared.

Iron ion radiation

The Fe ion radiation of GNS 304NG samples and CG counterparts was carried out at the ion implantation terminal in the Low Energy Heavy Ion Accelerator Facility (LEAF) platform, at the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, as schematically illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2b. The LEAF could perform homogeneous ion implantation into the sample surface layer within an area up to 50 × 50 mm2 by Fe ion implantation. Thus, up to approximately 25 squared samples were irradiated simultaneously under the same experimental conditions. Firstly, Fe13+ ions with an incident particle energy of 0.69 MeV u−1 were implanted into the samples at a flux of 2.5 × 1011 ions cm−2 s−1. Pre-experiments were performed with 3 different ion fluences, i.e., 5.0 × 1015, 1.0 × 1016, and 5.0 × 1016 ions cm−2, respectively. The radiation induced large-scale AMT was discovered in all these pre-experimental samples. Then, in order to confirm and elucidate this mechanism, we conducted a series of validation experiments with different ion fluxes, energies, and temperatures. For example, Fe10+ ions with an incident particle energy of 0.62 MeV u−1 were applied at a flux of 2.8 × 1011 ions cm−2 s−1, and the sample temperature was controlled to ~80 °C through water cooling. The total implanted Fe10+ ion fluences were within 6.50 × 1014 to 1.625 × 1017 ions cm−2.

High-temperature radiation experiments were also conducted at 350, 400, and 450 °C. For example, during radiation at 450 °C, Fe15+ ions with an incident particle energy of 0.65 MeV u−1 were applied at a flux of 7.0 × 1011 ions cm−2 s−1. The maximum ion fluence was 8.0 × 1016 ions cm−2.

Stopping and range of ions in matter (SRIM) simulation

The distributions of radiation dose and implanted Fe concentration (CFe) along depth from the irradiated surface (w) were derived from

and

where φ was the incident ion fluence, v(w) was the average vacancy generated per unit distance at w for each incident ion, R(w) was the average atomic implantation ion concentration distance at w, M was the atomic number density of the material, D was the unit thickness. Here, v(w) and R(w) were obtained from the SRIM output files (Vacancy.txt and Range.txt, respectively) by using a SRIM-2013 software package, which was used to evaluate how ions lose energy into matter and the final distribution of these ions after they stop within the target based on the Monte Carlo method48. In the present work, we used the Kinchin-Pease model in the SRIM simulation to evaluate Fe ion irradiation (34.68 MeV) in a material simulating 304NG (72 at.% Fe, 19 at.% Cr, and 9 at.% Ni), with a nominal displacement threshold energy of 40 eV for each element49.

The distributions of radiation dose and Fe concentration along depth obtained in the validation experiments are given in Supplementary Fig. 4. And the results of the pre-experiments and high-temperature experiments are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Structure characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations were conducted on an FEI Verios 460 unit under the concentric backscattering mode. TEM and STEM characterizations were carried out in an FEI Talos F200X microscope operated at 200 kV. And high-resolution STEM observations were carried out on a Titan Themis G2-300 double aberration-corrected unit operated at 300 kV.

To acquire the phase and interface information in peak damage regions in GNS 304NG samples before and after irradiation, TKD analysis was carried out on a ZEISS Gemini 300 SEM unit operated at 30 kV with a current of 6.0 nA. In addition, electron back-scattering diffraction (EBSD) analysis was performed on as-received CG samples using an FEI Nova 450 SEM unit operated at 18 kV. The scanning step size was set within 1/5 to 1/10 of the average grain size in EBSD and TKD. The EBSD and TKD data was analyzed by HKL Channel 5 (Version: 5.12.67.0).

Cross-sectional SEM and EBSD samples were firstly electrodeposited with a protective Ni coating, subsequently cut by WEDM, mechanically polished, and finally electrochemically polished in 10% perchloric acid alcohol solution (20 V, −20 °C, 90 s).

Cross-sectional TEM foils were prepared by focused ion beam (FIB) using an FEI Nanolab Helios 650 (Ga+) unit. A Pt layer was deposited to protect the sample surface before FIB milling. A same direction (along the SMRT processing direction x) was sectioned for all samples to exclude the possible effects of texture. And TEM samples were finally polished at low voltage (2 kV) and low current (39 pA) to clean the possible FIB-induced damages.

Radiation defect statistics

In this work, the main radiation-induced defects were DLs in samples irradiated at room temperature. In irradiated CG samples, although there were already few dislocations and SFs before irradiation, and dispersive martensite grains were formed after irradiation, DLs could still be clearly distinguished by WBDF TEM imaging. In irradiated GNS samples, the pre-existence of numerous other kinds of defects (e.g., dislocation tangles and stacking fault tetrahedrons, typically with sizes <3 nm) might bring mistakes in labeling radiation induced DLs. Since preliminary analyses indicated that the size of DLs in GNS 304NG was mostly within the range of 3–6 nm (see Supplementary Fig. 7), we used the following criteria to distinguish DLs:

-

1)

Both the BF and the WBDF TEM images were analyzed.

-

2)

Mark the 1/2a <111> DLs according to the directions of related Burgers vectors.

Subsequently, the DLs density and diameter were obtained. Here, the DLs density was calculated from the number of DLs (N) and the volume of observed zone (V) in a TEM foil, i.e., N/V, where V was calculated from length × width × thickness (within 70–110 nm, measured in FIB). The results were averaged from 3 different TEM foils for each irradiated sample. 1–2 images were taken from each foil. It is noted that almost no DLs should be introduced into TEM foils during FIB preparation, as revealed by carefully checking the non-irradiated sample in Supplementary Fig. 5.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

While XRD analysis typically provides phase information in samples with a larger dimension than TEM does, irradiated samples were analyzed on a Bruker D8 Advance XRD diffractometer (16 kW, using Cu Kα radiation) with a scanning angle range of 40–100° and a scanning rate of 2θ = 2° min−1. The fraction of a phase (i.e., γ-austenite or α‘-martensite) was determined from XRD pattern50 according to:

where n was the number of peaks of the phase used in calculation, \({{I}}_{{i}}^{{j}}\) and \({{R}}_{{i}}^{{j}}\) were the integrated intensity and material scattering factor for the j peak of the phase i, respectively.

Mechanical tests

The distribution of microhardness along depth was measured on cross-sectional samples, by measuring microhardness at different depths from the irradiated surface. A Qness Q10A+ microhardness tester equipped with a Vickers indenter was used, with a maximum load of 20 × g and a dwelling time of 10 s. Each microhardness value was averaged from at least 5 measurements.

Meanwhile, nanoindentation tests were conducted on sample surface from a planer view by using an Agilent G200 unit (Berkvoich indenter, strain rate 0.05 s−1). The maximum indentation depth was 2000 nm during a test. The load displacement data obtained during loading were analyzed using a continuous stiffness mode to obtain the indentation displacement dependence of hardness51. Subsequently, the equivalent surface hardness of a sample was estimated from the indentation displacement dependence of hardness according to the Nix-Gao correction model52. At least 5 measurements were performed on a sample.

Moreover, in-situ micropillar compression tests were performed by a Femto-Tools in-situ nanoindentation equipped in a Zeiss Gemini SEM 460 unit. Micropillar samples (with a ~ 3° taper angle) of ~5 μm in the average diameter and ~10 μm in the height (i.e., with a height-to-diameter ratio of 2) were prepared along the irradiation direction from sample surface by FIB. The compression process was loaded at a constant displacement rate (5 nm s−1) up to ~22% of engineering strain under a 10 μm Si-based flat-punch indenter. The force-displacement data was collected during compression testing, and a real-time video was applied to record the deformation process of the compressed micropillar.

Construction an atomic model of GNS 304NG

An atomic model of Fe-Cr-Ni alloy (71.9 at.% Fe, 18.5 at.% Cr, and 9.6 at.% Ni) with gradient nanostructure was set up as GNS 304NG ideal model for MD simulations. Based on our experimental results, the atomic model was set up with a box volume of 34.73 × 30.08 × 40.00 nm3, which contains gradient structure consisted of 4 consecutive layers (in an FCC array) with increasing thickness from top to bottom, similar to experimental samples. Between neighboring layers, Σ3 (111) GBs were built by making the z-direction of every grain at [111] orientation following coincidence site lattice theory. In every layer, there were low-angle GBs between neighboring grains.

To further analyze the mechanism of large-scale AMT, we built the 2nd MD model with a box volume of 8.96 × 9.03 × 9.58 nm3. In this model, two regions were set, including a spherical BCC phase located at the center of model, surrounded by an FCC Fe-Cr-Ni alloy. Furthermore, to explore the role of SFs on extension of large-scale AMT from central BCC phase to surrounded FCC phase, two cross SFs were pre-built in FCC phase but ended at BCC/FCC interface.

MD simulations and visualizations

By choosing this atomic model, we relaxed the sample by conjugate gradient algorithm, which was followed by thermal relaxation to the target temperature (300 K) to get a more energetic stable state.

After conjugate gradient relaxation and subsequent heating, following the classical cascade simulation method7, a primary knock-on atom (PKA) was selected randomly from the topmost layers and was given a kinetic energy to induce further cascade in the system to explore the irradiation tolerance of GNS 304NG model alloy. The energy of PKA was 80 keV and emitting direction was [\(00\bar{1}\)], which could well simulate the ion implantation experiments after considering the Coulomb screening effects as done in this work. A Nosé–Hoover53 thermostat was applied to the outermost layer of the box with a thickness of approximately 3 atomic layers to regulate atomic velocities based on the target temperature. Thus, during cascade simulation, the system was simulated with a microcanonical ensemble (constant particle number, constant volume, and constant energy) and canonical ensemble (constant particle number, constant volume, and constant temperature) to the interior and boundary atoms of the simulation box, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Considering the effects induced by residual stress after SMRT and stresses induced by phase transformation and ion implantation, we firstly carried out tensile simulations with 0.1 Å ps−1 strain rate to accelerate the microstructure evolution after cascade simulations. For the tensile deformation simulations, the applied force was along the z direction. Furthermore, we also carried out shear simulations with 0.1 Å ps−1 strain rate, while the applied force was along the x direction. Two regions with thickness of 20 Å from both surfaces of the simulation boxes were set as rigid bodies, resulting in a fixed box shape under the influence of the tensile or shear force. The other regions of the boxes were mobile during the whole simulation process. For the 2nd MD model as described above, the tensile simulations with 0.1 Å ps−1 strain rate along x direction were also performed after full Conjugate Gradient relaxations.

In both the heating and loading processes, atomic positions and velocities were integrated and updated at each time-step (1 fs) to maintain a constant temperature. The interatomic potential was based on the semi-empirical model developed with the embedded atom method, a reliable classical atomistic model for simulations of crystal defects in the Fe-Cr-Ni system54. With polyhedral template matching method embedded in an atomic analysis and visualization software called Ovito (version: 3.11.3)55,56,57,58, the phases distribution, SFs, and GBs could be distinguished in the simulation model. Here, SFs were recognized as HCP arrays due to their similar lattice arrangements, which was distinguished by further surrounding lattice analysis. All simulations were carried out using the MD package Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (version: 2 Aug 2023)59.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1719072660.

Code availability

Source code data are provided with this paper. All source codes for this paper are available at the Zenodo repository under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1720117161.

References

Zinkle, S. J. & Was, G. S. Materials challenges in nuclear energy. Acta Mater. 61, 735–758 (2013).

Zinkle, S. J. & Busby, J. T. Structural materials for fission & fusion energy. Mater. Today 12, 12–19 (2009).

Zinkle, S. J. & Snead, L. L. Designing radiation resistance in materials for fusion energy. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 241–267 (2014).

Abram, T. & Ion, S. Generation-IV nuclear power: a review of the state of the science. Energy Policy 36, 4323–4330 (2008).

Busby, J. T. Economic benefits of advanced materials in nuclear power systems. J. Nucl. Mater. 392, 301–306 (2009).

Allen, T., Busby, J., Meyer, M. & Petti, D. Materials challenges for nuclear systems. Mater. Today 13, 14–23 (2010).

Bai, X. M., Voter, A. F., Hoagland, R. G., Nastasi, M. & Uberuaga, B. P. Efficient annealing of radiation damage near grain boundaries via interstitial emission. Science 327, 1631–1634 (2010).

Han, W. et al. Design of radiation tolerant materials via interface engineering. Adv. Mater. 25, 6975–6979 (2013).

Demkowicz, M. J., Hoagland, R. G. & Hirth, J. P. Interface structure and radiation damage resistance in Cu-Nb multilayer nanocomposites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136102 (2008).

Zhang, X. et al. Radiation damage in nanostructured materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 96, 217–321 (2018).

Samaras, M., Derlet, P. M., Van Swygenhoven, H. & Victoria, M. Computer simulation of displacement cascades in nanocrystalline Ni. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 125505 (2002).

Bufford, D. C., Abdeljawad, F. F., Foiles, S. M. & Hattar, K. Unraveling irradiation induced grain growth with in situ transmission electron microscopy and coordinated modeling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 191901 (2015).

Sun, C. et al. Superior radiation-resistant nanoengineered austenitic 304L stainless steel for applications in extreme radiation environments. Sci. Rep. 5, 7801 (2015).

Odette, G. R., Alinger, M. J. & Wirth, B. D. Recent developments in irradiation-resistant steels. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 471–503 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Influence of chemical disorder on energy dissipation and defect evolution in concentrated solid solution alloys. Nat. Commun. 6, 8736 (2015).

Kumar, N. A. P. K., Li, C., Leonard, K. J., Bei, H. & Zinkle, S. J. Microstructural stability and mechanical behavior of FeNiMnCr high entropy alloy under ion irradiation. Acta Mater. 113, 230–244 (2016).

Chang, H. et al. Effect of radiation defects on grain boundary evolution under shock loading. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 31, 698–707 (2024).

Porter, D. L. Ferrite formation in neutron-irradiated type 304L stainless steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 79, 406–411 (1979).

Xu, C. et al. Irradiation-induced BCC-phase formation and magnetism in a 316 austenitic stainless steel. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 610–613 (2020).

Agrawal, P. et al. Irradiation response of innovatively engineered metastable TRIP high entropy alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 574, 154217 (2023).

Mansur, L. K. Correlation of neutron and heavy-ion damage. J. Nucl. Mater. 78, 156–160 (1978).

Du, J. et al. Superior radiation tolerance via reversible disordering-ordering transition of coherent superlattices. Nat. Mater. 22, 442–449 (2022).

Masters, B. C. Dislocation loops in irradiated iron. Nature 200, 254 (1963).

Gao, N., Yao, Z. W., Lu, G. H., Deng, H. Q. & Gao, F. Mechanisms for <100> interstitial dislocation loops to diffuse in BCC iron. Nat. Commun. 12, 225 (2021).

Li, J., Fan, C., Li, Q., Wang, H. & Zhang, X. In situ studies on irradiation resistance of nanoporous Au through temperature-jump tests. Acta Mater. 143, 30–42 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Superior twin stability and radiation resistance of nanotwinned Ag solid solution alloy. Acta Mater. 151, 395–405 (2018).

Shang, Z. et al. He ion irradiation response of a gradient T91 steel. Acta Mater. 196, 175–190 (2020).

Sun, C. et al. In situ evidence of defect cluster absorption by grain boundaries in Kr ion irradiated nanocrystalline Ni. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 44, 1966–1974 (2013).

Duan, J. et al. Effect of grain size on the irradiation response of grade 91 steel subjected to Fe ion irradiation at 300. C. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 13767–13778 (2022).

Etienne, A., Hernández-Mayoral, M., Genevois, C., Radiguet, B. & Pareige, P. Dislocation loop evolution under ion irradiation in austenitic stainless steels. J. Nucl. Mater. 400, 56–63 (2010).

Lu, K. Stabilizing nanostructures in metals using grain and twin boundary architectures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16019 (2016).

Zhou, X., Li, X. Y. & Lu, K. Enhanced thermal stability of nanograined metals below a critical grain size. Science 360, 526–530 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Li, Z. & Huang, M. Atomistic modeling of the interaction between matrix dislocation and interfacial misfit dislocation networks in Ni-based single crystal superalloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 70, 178–186 (2013).

Wang, Z. B., Lu, J. & Lu, K. Chromizing behaviors of a low carbon steel processed by means of surface mechanical attrition treatment. Acta Mater. 53, 2081–2089 (2005).

Garner, F. A., Toloczko, M. B. & Sencer, B. H. Comparison of swelling and irradiation creep behavior of fcc-austenitic and bcc-ferritic/martensitic alloys at high neutron exposure. J. Nucl. Mater. 276, 123–142 (2000).

Sun, Y. T., Kong, X. & Wang, Z. B. Superior mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of a 304 stainless steel plate with gradient nanostructure. Int. J. Plast. 155, 103336 (2022).

Singh, B. K. & Singh, V. Effect of fast neutron irradiation on tensile properties of AISI 304 stainless steel and alloy Ti–6Al–4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 528, 5336–5340 (2011).

Clement, C. D., Yang, C. & Wharry, J. P. Unexpected deformation-induced martensitic phase transformations in Ni–Cr and Ni–Cr–Fe alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 892, 146029 (2024).

Yang, X.-S., Sun, S. & Zhang, T.-Y. The mechanism of bcc α′ nucleation in single hcp ε laths in the fcc γ → hcp ε → bcc α′ martensitic phase transformation. Acta Mater. 95, 264–273 (2015).

Merezhko, M. S. et al. Macro-Scale strain localization in highly irradiated stainless steel investigated using digital image correlation. Acta Mater. 231, 117858 (2022).

Fang, T. H., Li, W. L., Tao, N. R. & Lu, K. Revealing extraordinary intrinsic tensile plasticity in gradient nano-grained copper. Science 331, 1587–1590 (2011).

Wu, X., Jiang, P., Chen, L., Yuan, F. & Zhu, Y. T. Extraordinary strain hardening by gradient structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7197–7201 (2014).

Li, B. et al. Evaluation of helium effect on irradiation hardening in F82H, ODS, SIMP and T91 steels by nano-indentation method. Fusion Eng. Des. 142, 6–12 (2019).

Hishinuma, A. et al. Current status and future R&D for reduced-activation ferritic/martensitic steels. J. Nucl. Mater. 258-263, 193–204 (1998).

Li, X., Lu, L., Li, J., Zhang, X. & Gao, H. Mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of gradient nanostructured metals and alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 706–723 (2020).

Huang, H. W., Wang, Z. B., Lu, J. & Lu, K. Fatigue behaviors of AISI 316L stainless steel with a gradient nanostructured surface layer. Acta Mater. 87, 150–160 (2015).

Lu, K. & Lu, J. Surface nanocrystallization (SNC) of metallic materials-presentation of the concept behind a new approach. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 15, 193–197 (1999).

Ziegler, J. F., Ziegler, M. D. & Biersack, J. P. SRIM–The stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 268, 1818–1823 (2010).

Nordlund, K. et al. Improving atomic displacement and replacement calculations with physically realistic damage models. Nat. Commun. 9, 1084 (2018).

De, A. K., Murdock, D. C., Mataya, M. C., Speer, J. G. & Matlock, D. K. Quantitative measurement of deformation-induced martensite in 304 stainless steel by X-ray diffraction. Scr. Mater. 50, 1445–1449 (2004).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic-modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 7, 1564–1583 (1992).

Nix, W. D. & Gao, H. Indentation size effects in crystalline materials: a law for strain gradient plasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 46, 411–425 (1998).

Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nose-Hoover chains: the canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635–2643 (1992).

Bonny, G., Castin, N. & Terentyev, D. Interatomic potential for studying ageing under irradiation in stainless steels: the FeNiCr model alloy. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 21, 085004 (2013).

Larsen, P. M., Schmidt, S. & Schiøtz, J. Robust structural identification via polyhedral template matching. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 24, 055007 (2016).

Stukowski, A., Bulatov, V. V. & Arsenlis, A. Automated identification and indexing of dislocations in crystal interfaces. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 20, 085007 (2012).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the open visualization tool. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Faken, D. & Jónsson, H. Systematic analysis of local atomic structure combined with 3D computer graphics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2, 279–286 (1994).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Zhang, S. & Dong, Y. B. Source data for the manuscript: Improved radiation resistance in metals via adaptive martensitic transformation, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17190726 (2025).

Dong, Y. B. Source code for the manuscript: Improved radiation resistance in metals via adaptive martensitic transformation, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17201171 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0510303, Z.B.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11427904, H.W.Z.; 12075141, N.G.), and the CAS-HK Joint Laboratory of Nanomaterials and Mechanics. We thank Profs. K. Lu and H.-J. Jin for fruitful discussion and critical reading of the paper, and Dr. Xiangbing Liu for providing 304NG stainless steel billets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G. and Z.B.W. initiated and supervised the project. N.G. and Z.B.W. designed the experiments. S.Z. and Y.T.S. prepared the samples. S.Z., Y.B.D., and Y.L. conducted radiation experiments. S.Z. and Y.T.S. conducted structural characterizations. S.Z. measured mechanical properties. Y.B.D. performed modeling and simulations. N.G., L.T.S., H.W.Z., and Z.B.W. acquired the funding. All authors discussed and analyzed the results. S.Z., Y.B.D., N.G., and Z.B.W. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jianren Zhou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Dong, Y.B., Sun, Y.T. et al. Improved radiation resistance in metals via adaptive martensitic transformation. Nat Commun 16, 10995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66125-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66125-9