Abstract

Valleytronics has emerged as a promising platform for energy-efficient and high-speed information processing. However, backscattering-induced valley depolarization remains a fundamental limitation, making valley-polarized waves with backscattering-free propagation highly desirable. Here, we demonstrate a general approach to realize chiral valley edge states in topological photonic crystals, which integrates the robust chiral edge states with valley degree of freedom. By controlling the valley Dirac masses, we selectively confine the chiral edge band around a single valley, enabling backscattering-free propagation while inducing valley polarization. Via engineering Dirac masses in both momentum and real spaces, we propose valley multiplexing as a novel functionality that enables independent and arbitrary control over waves with distinct valley polarizations. Moreover, two key components for valley multiplexing are demonstrated: a valley (de-)multiplexer and a valley-locked waveguide crossing, facilitating low-crosstalk signal routing. By establishing the interplay between topological quantum Hall and valley Hall phases, our work offers a new framework for robust valley-based information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to advantages in energy efficiency, robustness, and high processing speed, valley has been highlighted as a promising degree of freedom (DoF) for information encoding and storage, catalyzing the birth of valleytronics1,2,3 and valley photonics4,5. In certain crystalline materials like graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), valleys refer to a set of local extrema in energy bands, possessing the same energy but inequivalent momenta1. To process information via valley DoF, it is crucial to enable valley wave transport and control valley polarization6,7,8,9. However, since information is encoded in momentum space, the inevitable defect-induced backscattering is a persistent obstacle. This limited robustness of valley polarization mainly originates from its inherent reciprocity. In valleytronics, backscattering leads to inter-valley scattering even with perfect valley initialization10, causing severe valley depolarization and limiting valley lifetime; while in valley photonics, it gives rise to Anderson localization and propagation loss11,12.

Conversely, the quantum (anomalous) Hall phase has long been recognized as a strong topological phase, supporting unidirectional chiral edge states in accordance with the bulk-boundary correspondence13,14,15. Due to the broken time-reversal symmetry and the resulting non-reciprocity, these chiral edge states are entirely immune to backscattering and remain unaffected by defects and interface deformations of any kind. This novel property of backscattering-free transmission offers the potential for addressing the power consumption issue inherent in traditional complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) device technologies, spurring research efforts into the Chern networks16,17,18. Nonetheless, while the existence of chiral edge states is guaranteed by topology, their dispersion configuration in momentum space lacks specific constraints. Consequently, these chiral edge states typically span the Brillouin zone (BZ), without exhibiting valley-dependent characteristics.

Intuitively, integrating chiral edge states with the valley DoF offers a promising solution to not only solve the longstanding valley depolarization issue in valleytronics but also expand the usable DoFs in Chern networks. Although previous theoretical studies have suggested that chiral valley edge states can function as valley filters19,20,21, experimental confirmation remains absent. Beyond chiral valley edge states, the interplay between quantum Hall and valley Hall phases has also been explored22,23, revealing that chiral and valley edge states can coexist within a single system—either in separate bandgaps or within the same bandgap but spatially segregated.

Here, we propose a general approach to realize chiral valley edge states through Dirac mass engineering. In crystalline lattices, valleys can be effectively considered as low-energy massive Dirac quasiparticles, with their topological properties determined by the Dirac masses24,25. Thus, by means of Dirac mass engineering, the chiral edge band can be selectively confined around a single valley, thereby imparting valley-dependent characteristics. Due to the non-reciprocity and backscattering-free propagation, the chiral valley edge states can robustly preserve valley polarization during transmission.

We demonstrate the realization of chiral valley edge states by leveraging hybrid topological photonic crystal systems composed of Chern photonic crystals (CPCs) and valley photonic crystals (VPCs). The resulting unidirectional propagation and robust valley polarization are verified both numerically and experimentally. Furthermore, via precisely engineering Dirac masses in both momentum and real spaces, we introduce a novel functionality termed valley multiplexing, which enables independent and arbitrary control over waves associated with distinct valley polarizations. Two key components for photonic valley multiplexing are exhibited: a photonic valley (de-)multiplexer, serving as the core component enabling valley multiplexing; and a photonic valley-locked waveguide crossing, which facilitates low-crosstalk inter-crossing between waves with different valley-polarizations—a functionality that is difficult to achieve using either pure valleytronic or pure Chern systems.

Results

Chiral valley edge states

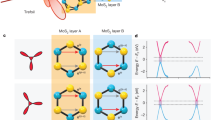

It is well established that topological quantum Hall insulators host gapless unidirectional chiral edge states, in accordance with the bulk-boundary correspondence (Fig. 1a)26,27,28. Nonetheless, these chiral edge states typically span both valleys in momentum space and thus lack valley-dependent characteristics. On the other hand, owing to the time-reversal symmetry, valley Hall insulators support “helical” valley edge states29,30,31, which manifest as two counter-propagating edge modes with distinct valley polarizations (Fig. 1b). Related by time-reversal symmetry, their inherent reciprocity makes the backscattering unavoidable.

a Chiral edge states. The edge band span both valleys and possesses no valley-dependent characteristics. b “Helical” valley edge states with intrinsic reciprocity. The two counter-propagating edge waves contain distinct valley polarizations. c Chiral valley edge states, inheriting both one-way propagation property and valley-dependent characteristics. d Jackiw-Rebbi mode at the domain wall between two lattices with opposite Dirac masses. This mode propagates unidirectionally with its group velocity determined by the signs of Dirac masses on both sides. e Z-shaped bending waveguide for K-valley waves, realized by engineering the spatial distribution of \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\). f A power splitter for K’-valley waves, designed via engineering the spatial distribution of \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\). Background strips represent valley Dirac masses in different domains: color denotes valley polarization, and strip orientation indicates the sign. g Dual-valley multiplexing achieved by precisely coding Dirac mass distributions in both momentum and real spaces. The flow of both valley-polarized waves can be independently and flexibly molded.

Our primary objective in realizing the chiral valley edge state is to confine the chiral edge band around a single valley (Fig. 1c). In the following, we present a general approach based on valley Dirac mass engineering, showing that chiral edge bands can be selectively restricted to a specific valley. These states integrate unidirectional propagation with valley-dependent characteristics, inheriting the advantages of both quantum Hall and valley Hall phases.

Usually, in two-dimensional (2D) graphene-like lattices, valleys refer to a set of inequivalent local extrema in energy bands, located at BZ corners (i.e., the K and K’ points). The eigenstates near a given valley (say, the K valley) are governed by a local Dirac Hamiltonian \({H}_{K}\left({{\boldsymbol{k}}}\right)={v}_{x}{k}_{x}{\sigma }_{x}+{v}_{y}{k}_{y}{\sigma }_{y}+{m}_{K}{\sigma }_{z}\). As such, a valley can be effectively deemed as a massive Dirac quasiparticle, with its topological features characterized by its Dirac mass—\({m}_{K}\). At a domain wall between two lattices with opposite-sign \({m}_{K}\) (see Fig. 1d), a unidirectional K-valley Jackiw-Rebbi mode is topologically ensured, whose propagation direction is determined by the signs of two \({m}_{K}\)32\(.\)

For a single 2D lattice, the Dirac masses on different valleys (\({m}_{K}\) and \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\)) can be separately engineered. This allows us to mold the flows of different valley states independently by spatially encoding the distributions of \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) and \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\), thereby enabling precise control over the valley polarization of chiral edge states. For instance, as shown in Fig. 1e, by engineering \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) but keeping a homogeneous \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\), we can construct a Z-shaped bending waveguide supporting chiral K-valley waves. Conversely, by keeping \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) uniform and engineering \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\), a backscattering-immune power splitter for K’-valley waves can be created (Fig. 1f). More significantly, since the Dirac masses can be discretionarily engineered in both momentum and real spaces and thereby the valley polarization of each chiral edge mode can be independently controlled, it is possible to simultaneously implement a unidirectional K-polarized bending waveguide and a backscattering-immune K’-polarized power splitter within the same structure by simply superposing the distributions of K- and K’-valley masses (Fig. 1g). It is worth emphasizing that, this flexible and comprehensive utilization of both valleys—referred to as valley multiplexing—not only multiplies the transmission capacity but also enables diverse functionalities on a single chip, offering significant potential for high-density integration.

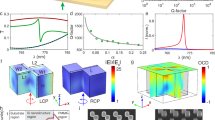

We demonstrate the realization of chiral valley edge states in hybrid topological photonic crystal systems composed of topological CPCs and VPCs, which together provide sufficient DoFs for Dirac mass engineering. For instance, Fig. 2a plots the band structure of a Chern photonic crystal (CPC-1), composed of a honeycomb array of gyromagnetic rods (yttrium iron garnet, YIG). Figure 2b presents the band structure of VPC-1, made from two sets of dielectric rods with different radii. Berry curvatures of the two crystals are encoded in color, reflecting their different valley Dirac masses. Here, we consider the transverse magnetic (TM) polarization. Detailed material information can be found in Method and Supplementary Note 1.

a Bulk band structure of a Chern photonic crystal (CPC-1), with Berry curvature encoded as color, reflecting that CPC-1 has negative Dirac masses at both valleys. The unit cell of CPC-1 consists of two YIG rods under a biased external magnetic field. b Bulk band structure of a valley photonic crystal (VPC-1). VPC-1 has a positive Dirac mass at K valley and a negative Dirac mass at K’ valley. Its unit cell is composed of two ceramic rods with different radii. c Photonic chiral valley edge waveguide supporting chiral K-valley edge states. To mimic the 2D condition, the photonic crystals are sandwiched between two metallic plates. An external magnetic field is applied to YIG rods by positioning two magnets above and beneath each individual rod. An array of air hole is reserved for experimental excitation and probing. Inset: Closed-view photograph of the sample. A dielectric foam board (n = 1.04) is used to position the rods. d Edge dispersion of the chiral K-valley edge waveguide. Edge band locating around the K valley confirms the exclusive support for K-polarized modes. Measured dispersion (FFT density) is represented by the background color. e Chiral valley edge waveguide supporting K’-polarized modes.

Because their K (K’) valley masses take opposite (same) signs, when we combine these two crystals together (Fig. 2c), the domain-wall between them supports only a chiral K-valley mode propagating to the right (see the red in-gap state in Fig. 2d). Figure 2c exhibits the experimental setup for measuring the chiral valley edge states. To mimic the 2D condition, the photonic crystals are sandwiched between two metallic plates. An external magnetic field of Bext = 0.042 T is applied to YIG rods (along \(\pm z\) direction) by positioning two magnets above and beneath each rod. A dielectric foam board (n = 1.04) is used to position the rods (see inset in Fig. 2c). The dispersion of chiral K-valley edge state is experimentally probed by performing Fourier transform on the measured complex Ez field along the domain wall, as represented by the color plaques in Fig. 2d [see Method and Supplementary Note 2 for detailed experimental setup]. Similarly, we can selectively endow the chiral edge state with K’-valley polarization by utilizing CPC-2 (time-reversal counterpart of CPC-1, featuring positive masses at both valleys) and VPC-1, as shown in Fig. 2e. Notably, since the orientation of Bext is reversed when changing from CPC-1 to CPC-2, the propagation direction of the corresponding edge states flips [see Supplementary Note 3 for more detailed numerical and experimental edge dispersion]. We also validate the robustness of our chiral valley edge states by considering wave transport against position perturbations and several types of obstacles (Supplementary Figs. S10 and S11).

To further present the unique valley multiplexing functionality, two representative photonic devices based on the chiral valley edge states are demonstrated: a photonic valley (de-)multiplexer, serving as the core component enabling valley multiplexing; and a photonic valley-locked waveguide crossing, which facilitates low-crosstalk inter-crossing between waves with different valley-polarizations.

Photonic valley (de-)multiplexer

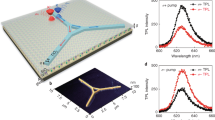

Multiplexer, as a core component of multiplexing techniques33,34, is designed to combine individual signals into a composite one. Transmitting such a composite signal through a shared bus channel not only enhances data transmission capacity but also improves chip space utilization. In the context of valley multiplexing, which aims to merge K- and K’-polarized waves into a single waveguide (i.e., the bus channel), the Dirac mass distributions for two valleys can be deduced as in Fig. 3a. According to the superposed Dirac mass distribution, we construct the photonic valley multiplexer using VPC-1, CPC-1, and CPC-2 (yellow, blue and pink domain in Fig. 3b, respectively).

a Spatial distributions of \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) and \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\), forming two bending waveguides for K- and K’-valley waves, respectively. These two bending waveguides together form the valley multiplexer. b Photonic valley multiplexer. This multiplexer is composed of three types of topological photonic crystals (CPC-1, CPC-2, and VPC-1), realized based on the spatially superposed mass distributions in (a). Insets: Edge dispersion for each domain wall channel. c, d Simulated field profiles when electromagnetic waves are incident from Port 1 and Port 3, respectively. Waves with different valley-polarizations converge into the horizontal bus waveguide without valley flipping. e, f Simulated and measured transmission spectra, reflecting the strong isolation between the K- and K’-valley channels.

As illustrated in Fig. 3b, a Y-junction multiplexer is formed between three domain-wall waveguides. As we mentioned above, a chiral K-valley (K’-valley) edge state is supported at the VPC-1@CPC-1 (VPC-1@CPC-2) domain wall. In addition, since CPC-1 and CPC-2 have opposite masses at both valleys, the CPC-1@CPC-2 domain wall supports two chiral valley edge states, each localized at one specific valley (see inset of Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S9). Thus, the CPC-1@CPC-2 domain wall serves as the bus waveguide, carrying signals with both valley polarizations. Consequently, the downward-propagating K-polarized wave and upward-propagating K’-polarized wave converge into the horizontal bus waveguide. Simulated field profiles in Fig. 3c, d show smooth transmission with no observable scattering into the opposite valley, as confirmed by the Fourier spectra (insets of Fig. 3c, d). Moreover, the simulated (solid lines) and measured (dashed lines) transmission spectra in Fig. 3e, f also verify both the functionality of valley multiplexer and the one-way characteristic of valley chiral edge states. Given that obstacles at the junction point may induce inter-valley scattering, we further provide simulations of the multiplexing process against position perturbation and cavity obstacles (Supplementary Fig. S12).

For independent manipulation of valley-polarized modes, a valley de-multiplexer is essential to split different valley waves into designated channels. Notably, since all three channels in Fig. 3b are one-way waveguides, this structure cannot be used as a de-multiplexer by simply impinging waves from the right-hand side. Instead, a photonic valley de-multiplexer can be implemented by its reversed structure as depicted in Fig. 4a. When electromagnetic waves are incident from the left, the two valley components are routed into different channels at the Y-junction (Fig. 4b), demonstrating de-multiplexing functionality. To verify this valley-dependent splitting effect, we compare the Ez-field profiles with the simulated eigen edge modes. As shown in Fig. 4c, d, the upper CPC-1@VPC-1 waveguide field is asymmetric about the edge with a clockwise energy vortex, while the field in lower CPC-2@VPC-1 waveguide is symmetric with two energy vortexes. These features align well with the eigen modes at K/K’ valley, confirming their valley polarization purity (see the eigen modes in Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, we measure the field profiles in the two domain-wall waveguides, respectively, as shown in the right panels of Fig. 4c, d. The measured profiles match well with the simulation results. In addition, we directly measure the field profiles along the CPC-1@VPC-1 and CPC-2@VPC-1 channels and extract their corresponding edge dispersions (Supplementary Figs. S4d and S4e). All our experimental results confirm the pure valley polarization in both channels.

a Schematic diagram of a photonic valley demultiplexer. Insets: Valley Dirac masses of the three photonic crystals involved. b Simulated Ez-field profile at 5.5 GHz, excited by a point source located on the left (yellow star). c Left: Ez-field (color map) and Poynting vector (black arrows) distribution in the CPC-1@VPC-1 waveguide (framed in green box in (b)). The pink circular arrow indicates an energy vortex at the edge. Right: Measured Ez-field profile. The black circles represent the positions of rods. The asymmetric field distribution about the edge matches well with simulation result, indicating K-valley polarization of the propagating wave. d Left: Ez-field and Poynting vector distribution in the CPC-2@VPC-1 waveguide (framed in brown box in (b)). Right: Measured Ez-field profile. The symmetric field distribution indicates the K’-valley polarization. e Refraction of electromagnetic waves from the valley demultiplexer to the empty-waveguide region at 5.57 GHz. Since the edge modes lie below the light cone of air, two acrylic semi-circular lenses (n = 1.45) are positioned at the two exits to couple the beams outward. Measured Ez profiles are plotted in the right panel, aligning well with simulations. Inset: k-space analysis on the out-coupling waves. The red (blue) circles indicate the K-valley (K’-valley) momentum of edge modes, while the black circles indicate the isofrequency contours of the acrylic lenses. The conservation of the tangential component of the wave vector determines the direction of the refracted beam. f Refraction of the electromagnetic waves in another valley demultiplexer where VPC-1 in (e) is replaced by VPC-2 (orange domain).

In valley photonics, valley edge states exhibit topologically protected refraction at the valley-preserving zigzag termination31,35. Since the outgoing beams conserve tangential components of the wave vector, the direction of the refracted beam is determined by the valley polarization of valley edge state. Therefore, this characteristic allows further experimental verification of two channels’ pure valley polarizations, by observing the refraction direction at the waveguide exits. As shown in Fig. 4e, we place an Ez-polarized point source at the CPC-1@CPC-2 waveguide. The excited field is routed by the de-multiplexer and subsequently refracts into the upper and lower empty-waveguide regions. Notably, since the frequencies of our chiral valley edge states lie below the air’s light cone, two acrylic semi-circular lenses are placed at the exits to efficiently couple the beams outward [see supplementary Note 2 for details of the experimental setup]. The resulting output beams exhibit valley-dependent refraction: the measured output beam at the upper-right CPC-1@VPC-1 exit is refracted to the left while the beam at the lower-right CPC-2@VPC-1 exit is refracted to the right. These observed field patterns are consistent with both the k-space analyses and the numerically simulated results. An additional advantage of our approach is the reconfigurability of propagation paths by engineering the Dirac mass distribution. As the simulated and measured results shown in Fig. 4f, by reversing the valley Dirac masses of VPC domain (orange domain, denoted as VPC-2), the propagation paths of the K- and K’ -polarized modes are flipped, enabling flexible routing. We also analyze the robustness of valley de-multiplexer, as presented in Supplementary Fig. S13.

Valley-locked waveguide crossing

Apart from multiplexer and de-multiplexer, waveguide crossing is another critical component for high-density integrated in photonic chips. As device density and circuit complexity increase, optical waveguide crossings become essential elements that significantly influence the overall performance of photonic chips36,37,38,39,40. Here, we propose a valley-locked waveguide crossing based on valley-dependent Dirac mass engineering. To our best knowledge, crossing between topological waveguides has yet to be proposed or realized so far, whose performance can be effectively improved by topological aspects of robust edge states.

In order to have a K-valley edge mode propagating horizontally and a K’-valley edge mode propagating vertically, we design the Dirac mass distributions for two valleys separately (Fig. 5a), and then construct the valley-locked waveguide crossing via the superposition scheme. As a result, the valley Dirac mass configuration required for each domain is illustrated in Fig. 5b: CPC-1 (blue) and CPC-2 (pink) occupy the upper-left and lower-right regions, while VPC-1 (yellow) and VPC-2 (orange) occupy the lower-left and upper-right. Due to the distinct valley polarizations of edge modes, the two channels are decoupled from each other even at the intersection point, resulting in minimal crosstalk. Furthermore, inheriting the topological protection of chiral edge states, this type of waveguide crossing can effectively minimize both backscattering loss and crosstalk.

a Spatial distributions of \({m}_{K}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) and \({m}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\), forming a horizontal channel for K-valley waves and a vertical channel for K’-valley waves. b Schematic of the valley-locked waveguide crossing, consisting of two CPCs (blue and pink) and two VPCs (yellow and orange). Insets: Valley Dirac masses of the four constituent photonic crystals. c Simulated transmission spectra of the waveguide crossing with electromagnetic waves excited at port 1. The crosstalk is characterized by the difference between S41 (pink line) and S21 (baby-blue line), signifying a crosstalk level below -16.2 dB. d Measured transmission spectra for port 1 excitation, showing average crosstalk about −9.8 dB. e Measured Ez-field profile at 5.57 GHz for port 1 excitation, demonstrating smooth propagation and negligible crosstalk. f Corresponding Fourier density of the field profile in (e), further confirming the valley-locked feature of the crossing. g, h Simulated and measured transmission spectra when electromagnetic waves are excited at port 3. i, j Measured Ez-field profile and corresponding Fourier density for port 3 excitation, confirming K′-valley polarization and low crosstalk.

We validate the performance of the valley-locked waveguide crossing by analyzing its transmission spectra and electromagnetic field profiles. First, we launch electromagnetic waves from port 1, then probe the transmission spectra from all other ports, as shown in Fig. 5c. The pink line plots the crosstalk from port 1 to port 4, which is lower than −16.2 dB within the edge-mode-supported frequency range (highlighted in gray, from 5.20 to 5.67 GHz). Notably, the orange line shows even lower crosstalk from port 1 to port 3, confirming the unidirectional nature of our waveguide channels. Corresponding experimental measurements of transmission spectra are shown in Fig. 5d, indicating an average crosstalk level of approximately −9.8 dB. We scan the near-field pattern around the crossing region hole-by-hole to observe the cross transmission of two valley waves. The measured field profile at 5.57 GHz demonstrates a smooth propagation with negligible crosstalk (Fig. 5e). Besides, a 2D Fourier transform is applied to the measured field profiles to obtain its momentum information. As demonstrated in Fig. 5f, the momentum is concentrated around the K valley, confirming the valley-locked feature of topological waveguide crossing. Similar behaviors are observed when electromagnetic waves are excited from port 3, showing a crosstalk level below −15.7 dB in simulation (Fig. 5g) and an average crosstalk about −11.8 dB in experiment (Fig. 5h). Its momentum distribution concentrates around K’ valley (Fig. 5j). Although there exists some insertion loss and degradation of the crosstalk level in experiment, which may result from the reserved air holes and fabrication imperfections, our findings demonstrate that signals in the two channels maintain distinct valley polarizations, effectively ensuring the low crosstalk in this topological waveguide crossing. We also perform analyses on the robustness of this valley-locked waveguide crossing (Supplementary Fig. S14).

Discussion

In this work, we propose a general strategy for realizing chiral valley edge states which integrate chiral edge states with valley degree of freedom. Our approach is based on Dirac mass engineering for individual valleys, enabling selective confinement of the chiral edge band around a single valley and thus imparting valley-dependent properties. Via precisely configuring the Dirac mass distribution in both momentum and real spaces, we achieve independent control of both valley states along arbitrary pathways, thereby realizing valley multiplexing. To demonstrate this mechanism, we implement two key valley-dependent devices using topological photonic crystals. One is a photonic valley (de-)multiplexer, which is a crucial component for separating or converging modes with distinct valley polarizations. The other is a photonic valley-locked waveguide crossing, which can enhance the performance of densely integrated photonic chips. Both devices are experimentally characterized in the microwave regime.

Although our idea is implemented on a microwave photonic crystal platform, the underlying design principle is general and can be readily extended to other frequency ranges and other physical systems including condensed matter, acoustics and electronic circuits. For example, while we use gyromagnetic material to break time-reversal symmetry here, our main results might be extended to optical frequencies by leveraging Floquet topological insulators41,42,43,44,45. In addition, despite the weak magneto-optic effect of gyrotropic materials in visible regime, the effect is strong enough in terahertz regime to support our scheme46,47,48,49,50. On the other hand, by combining valleytronic and anomalous Hall materials51,52,53,54, similar results can also be observed in condensed matter systems.

We believe that our approach not only addresses the critical limitations in existing valleytronics and Chern networks but also offers promising opportunities for integrating valleytronics concepts into next-generation communication systems. Ultimately, it provides a powerful pathway for substantially boosting transmission capacity through comprehensive utilization of the valley degree of freedom.

During the preparation of this work, we became aware of a related experimental report on chiral valley edge states55. The primary distinction is that our method is based on bulk Dirac mass engineering, whereas their approach relies on boundary modifications.

Methods

Materials

The valley photonic crystals in this work are realized by two kinds of dielectric rods with radii \({d}_{1}=6\,{{\rm{mm}}}\) and \({d}_{2}=7.5\,{{\rm{mm}}}\), arranged in hexagonal lattice with lattice constant \(a=18\,{{\rm{mm}}}\). The material of the rod is ceramic, with relative permittivity of 8.8 and a relative permeability of 1. The Chern photonic crystals in this work are realized by using gyromagnetic rods biased by an external magnetic field. The gyromagnetic rods have radii of \({d}_{0}=6\,{{\rm{mm}}}\), and also are arranged in a hexagonal lattice with lattice constant \(a=18\,{{\rm{m}}}\). The gyromagnetic material is yttrium iron garnet (YIG), a ferrite with relative permittivity 14.6. The relative magnetic permeability of the YIG has the form of

where \({\mu }_{r}=1+({\omega }_{0}+i\alpha \omega ){\omega }_{m}/({({\omega }_{0}+i\alpha \omega )}^{2}-{\omega }^{2})\),\({\mu }_{k}=\omega {\omega }_{m}/({({\omega }_{0}+i\alpha \omega )}^{2}-{\omega }^{2})\), \({\omega }_{m}=4\pi \gamma {M}_{s}\), \({\omega }_{0}=\gamma {\mu }_{0}{H}_{0}\), \(4\pi {M}_{s}=0.195{{\rm{T}}}\) is the saturation magnetization, \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{0}=0.042{{\rm{T}}}\) is the external magnetic field, \(\gamma=1.76\times {10}^{11}\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}{{{\rm{T}}}}^{-1}\) is the gyromagnetic ratio, \(\alpha=0.0001\) is the damping coefficient, and ω is the operating frequency. The Dirac masses of the Chern photonic crystals can be controlled by the direction of the external magnetic field, which can be tuned by the direction of magnets in the experiment. Both the ceramic and YIG rods have a height of 5 mm, and are sandwiched between two metallic plates to mimic the two-dimensional condition. Photonic modes with transverse magnetic polarization are considered in this work.

Experiments

In our microwave experiments, monopole antennas connected to a vector network analyzer (Keysight E5071C) via coaxial cables were employed to excite and probe electromagnetic waves. The antennas used had a length of 13 mm. For all measurements, electromagnetic fields were excited by inserting a source antenna into the sample through reserved air holes.

For edge dispersion measurements, the probe antenna scanned the Ez-field profiles sequentially along the domain walls between photonic crystals through reserved air holes. Edge dispersions (Figs. 2, S4 and S8) were obtained via Fourier transformation of the measured Ez fields. Similarly, Ez fields in Fig. 5e, i were measured by probing each hole individually around the waveguide crossing region, with the corresponding momentum information in Fig. 5f, j extracted through Fourier transformation. The measured FFT spectra in Figs. 2, S4 and S8 are obtained by summing up the k-components in both the first and second BZs. The 2D FFT maps plotted in Figs. 3 and 5 are original spectra in 2D k-space, without BZ folding.

In Fig. 4e, f, electromagnetic fields were excited at the CPC-1@CPC-2 domain wall, directing the waves according to valley polarization into free space, where refracted Ez fields were scanned. To maintain quasi-two-dimensional conditions, a metallic parallel-plate waveguide was constructed in free space to support guided modes. Additionally, since edge mode frequencies lie below the air’s light cone, two acrylic semi-circular lenses were placed at the outputs to facilitate coupling into free space.

Simulations

The dispersion relations and field patterns were simulated using the finite element software COMSOL Multiphysics. The unit cell of the Chern photonic crystals and valley photonic crystals are hexagonal lattice, of which we applied Floquet boundary conditions on the outer boundaries when calculating the bulk band structures in Fig. 2a, b, S5, and S6. The edge band structure in Fig. 2d, e, S7-S9 was calculated using a supercell with 1 × 14 periods.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding authors.

References

Vitale, S. A. et al. Valleytronics: opportunities, challenges, and paths forward. Small 14, 1801483 (2018).

Rasmita, A. & Gao, W. -b Opto-valleytronics in the 2D van der Waals heterostructure. Nano Res. 14, 1901 (2020).

Ciarrocchi, A., Tagarelli, F., Avsar, A. & Kis, A. Excitonic devices with van der Waals heterostructures: valleytronics meets twistronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 449 (2022).

Xue, H., Yang, Y. & Zhang, B. Topological valley photonics: physics and device applications. Adv. Photonics Res. 2, 2100013 (2021).

Liu, J.-W. et al. Valley photonic crystals. Adv. Phys.: X 6, 1905546 (2021).

Rohling, N. & Burkard, G. Universal quantum computing with spin and valley states. N. J. Phys. 14, 083008 (2012).

Culcer, D., Saraiva, A. L., Koiller, B., Hu, X. & Das Sarma, S. Valley-based noise-resistant quantum computation using Si quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 126804 (2012).

Jiménez-Galán, Á, Silva, R. E. F., Smirnova, O. & Ivanov, M. Lightwave control of topological properties in 2D materials for sub-cycle and non-resonant valley manipulation. Nat. Photonics 14, 728 (2020).

Tyulnev, I. et al. Valleytronics in bulk MoS(2) with a topologic optical field. Nature 628, 746 (2024).

Xu, R., Zhang, Z., Liang, J. & Zhu, H. Valleytronics: fundamental challenges and materials beyond transition metal Chalcogenides. Small 21, 2402139 (2024).

Rosiek, C. A. et al. Observation of strong backscattering in valley-Hall photonic topological interface modes. Nat. Photonics 17, 386 (2023).

Yu, D., Arora, S. & Kuipers, L. Impact of transforming interface geometry on edge states in valley photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 116901 (2024).

Haldane, F. D. Model for a quantum Hall effect without Landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988).

Wang, Z., Chong, Y., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljacic, M. Observation of unidirectional backscattering-immune topological electromagnetic states. Nature 461, 772 (2009).

Chang, C.-Z., Liu, C.-X. & MacDonald, A. H. Colloquium: Quantum anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 011002 (2023).

Ovchinnikov, D. et al. Topological current divider in a Chern insulator junction. Nat. Commun. 13, 5967 (2022).

Zhao, Y. F. et al. Creation of chiral interface channels for quantized transport in magnetic topological insulator multilayer heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 14, 770 (2023).

Yuan, W. et al. Electrical switching of the edge current chirality in quantum anomalous Hall insulators. Nat. Mater. 23, 58 (2024).

Pan, H., Li, X., Zhang, F. & Yang, S. A. Perfect valley filter in a topological domain wall. Phys. Rev. B 92, 041404(R) (2015).

Zhang, X., Li, S., Lan, Z. Gao, W. & Chen, M. L. N. Reconfigurable photonic valley filter in hybrid topological heterostructures. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2400797 (2024).

Gao, P., Zhang, Z. & Christensen, J. Sonic valley-Chern insulators. Phys. Rev. B 101, 020301(R) (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Hybrid topological photonic crystals. Nat. Commun. 14, 4457 (2023).

Liu, J., Liang, L., Xu, M. & Poo, Y. Coexisting valley and chiral edge states in topological photonic crystals. Opt. Express 33, 13887 (2025).

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109 (2009).

Bansil, A., Lin, H. & Das, T. Colloquium: Topological band theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 021004 (2016).

Wang, Z., Chong, Y., Joannopoulos, J. & Soljačić, M. Reflection-free one-way edge modes in a gyromagnetic photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 013905 (2008).

Poo, Y., Wu, R. -x, Lin, Z., Yang, Y. & Chan, C. T. Experimental realization of self-guiding unidirectional electromagnetic edge states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 093903 (2011).

Ndao, B. B. A., Vallini, F., Amili, A. E., Fainman, Y. & Kanté, B. Nonreciprocal lasing in topological cavities of arbitrary geometries. Science 358, 636 (2017).

Ma, T. & Shvets, G. All-si valley-Hall photonic topological insulator. N. J. Phys. 18, 025012 (2016).

Chen, X.-D., Zhao, F.-L., Chen, M. & Dong, J.-W. Valley-contrasting physics in all-dielectric photonic crystals: Orbital angular momentum and topological propagation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 020202(R) (2017).

Gao, F. et al. Topologically protected refraction of robust kink states in valley photonic crystals. Nat. Phys. 14, 140 (2017).

Jackiw, R. & Rebbi, C. Solitons with fermion number ½. Phys. Rev. D. 13, 3398 (1976).

Dai, D. & Bowers, J. E. Silicon-based on-chip multiplexing technologies and devices for Peta-bit optical interconnects. Nanophotonics 3, 283 (2014).

Khonina, S. N., Kazanskiy, N. L., Butt, M. A. & Karpeev, S. V. Optical multiplexing techniques and their marriage for on-chip and optical fiber communication: a review. Opto-Electron. Adv. 5, 210127 (2022).

Liu, G. G. et al. Observation of an unpaired photonic Dirac point. Nat. Commun. 11, 1873 (2020).

Wu, S., Mu, X., Cheng, L., Mao, S. & Fu, H. Y. State-of-the-art and perspectives on silicon waveguide crossings: a review. Micromachines 11, 326 (2020).

Ma, Y. et al. Ultralow loss single layer submicron silicon waveguide crossing for SOI optical interconnect. Opt. Express 21, 29374 (2013).

Sun, C., Yu, Y. & Zhang, X. Ultra-compact waveguide crossing for a mode-division multiplexing optical network. Opt. Lett. 42, 4913 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Universal multimode waveguide crossing based on transformation optics. Optica 5, 1549 (2018).

Xu, H. & Shi, Y. Metamaterial-based Maxwell’s Fisheye lens for multimode waveguide crossing, Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1800094 (2018).

Rechtsman, M. C. et al. Photonic Floquet topological insulators. Nature 496, 196 (2013).

Leykam, D., Rechtsman, M. C. & Chong, Y. D. Anomalous topological phases and unpaired dirac cones in photonic floquet topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 013902 (2016).

Maczewsky, L. J., Zeuner, J. M., Nolte, S. & Szameit, A. Observation of photonic anomalous Floquet topological insulators. Nat. Commun. 8, 13756 (2017).

Noh, J., Huang, S., Chen, K. P. & Rechtsman, M. C. Observation of Photonic Topological Valley Hall Edge States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 063902 (2018).

Jin, J. et al. Towards Floquet Chern insulators of light. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02003-1 (2025).

Shuvaev, A. M. et al. Giant magneto-optical faraday effect in HgTe thin films in the terahertz spectral range. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107404 (2011).

Chochol, J. et al. Magneto-optical properties of InSb for terahertz applications. AIP Adv. 6, 115021 (2016).

Zhao, D., Fan, F., Tan, Z., Wang, H. & Chang, S. Tunable On-Chip Terahertz isolator based on nonreciprocal transverse edge spin state of asymmetric magneto-plasmonic waveguide. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200509 (2022).

Zhao, D. et al. Terahertz magneto-optical metadevice for active spin-selective beam steering and energy distribution with nonreciprocal isolation. Optica 10, 1295 (2023).

Jia, R. et al. On-chip active non-reciprocal topological photonics. Adv. Mater. 37, e2501711 (2025).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489 (2014).

Vargas, A. et al. Tunable and laser-reconfigurable 2D heterocrystals obtained by epitaxial stacking of crystallographically incommensurate Bi2Se3 and MoS2 atomic layers. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601741 (2017).

Rodenbach, L. K. et al. Bulk dissipation in the quantum anomalous Hall effect. APL Mater. 9, 081116 (2021).

Rosen, I. T. et al. Measured potential profile in a quantum anomalous hall system suggests bulk-dominated current flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 246602 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. One-way valley-robust transport in edge-tailored photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 203803 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62035016), Singapore National Research Foundation Competitive Research Program (Grant No. NRF-CRP23-2019-0007), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2023B1515040023), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (Grant No. 24lgzy007), Research Center for Industries of the Future (RCIF) at Westlake University (Grant No. 210000006022312), Westlake Education Foundation (Grant No.103110736022301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.L., G.-G.L., and W.J.C. initiated the project. J.W.L., G.-G.L., and W.J.C. performed the simulation and analytical analysis. Bo Z., J.W.L., H.C.M. and W.J.C. designed and carried out the experiment, and analyzed the experimental data. B.Z., W.J.C. and J.W.D. supervised this project. J.W.L., G.-G.L, Bo Z., H.C.M., R.L., M.L., X.D.C., B.Z., W.J.C., and J.W.D. discussed the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Guillermo Arregui and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, JW., Liu, GG., Zhang, B. et al. Chiral valley edge states based on Dirac mass engineering. Nat Commun 16, 11256 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66126-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66126-8