Abstract

The tremendous costs of disposal and potential environmental problems caused by waste catalysts bring about an urgent need for catalyst regeneration without loss of catalytic activity and stability. Here, we report on a simple and reproducible method to regenerate waste ozonation catalysts by carbonization of self-doped biological secretions to synthesize highly active and stable carbon-based nano-single-atom-site catalysts (NSASCs), Cu@graphitic carbon (GC)-Al2O3, converting waste catalysts into a sustainable resource. Specifically, Cu metal atoms are dispersed on the GC-Al2O3 composite support in the form of Cu1–C3 and Cun–Cun, primarily because the adsorption of biological secretions enhances the dispersibility of the metal nanoparticles. The pilot-scale demonstration reduces the average chemical oxygen demand (COD) of effluent in the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system from 79.56 to 30.01 mg L−1, demonstrating enhanced catalytic activity and stability relative to the pristine fresh catalyst. The combined experimental and theoretical investigations reveal that the Cu1–C3 sites promote the formation of *Oad, while the Cun–Cun sites induce the generation of O2•− and 1O2 from *Oad, contributing to catalytic synergism in both radical and non-radical pathways. Additionally, the life cycle assessment confirms the economic feasibility and sustainability of the regeneration strategy. Our findings propose a general approach to reactivating waste catalysts, which can also inspire biological secretions in atom dispersal modulation and modification of other materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wide application and development of heterogeneous catalysts in petrochemical, power, and environmental remediation industries result in a vast production of waste catalysts1,2,3. Taking ozonation catalysts utilized in wastewater treatment as an example, more than 1.2 million tons of catalysts are replaced in China each year, resulting in hazardous solid waste treatment costs exceeding US$400 million4. Regeneration is the environmentally and economically preferred option for dealing with waste catalysts as it minimizes the use of raw materials and reduces the need for ultimate recovery or disposal, which aligns with both the global sustainable development goals. However, regeneration methods that restore active sites, such as in-situ air- and water-backflushing, suffer from secondary pollution and poor stability5,6. Thus, there is an urgent need for a catalyst regeneration strategy without loss of catalytic activity and stability.

Waste ozonation catalyst (Al2O3-based) in this study was collected from China’s largest petrochemical wastewater treatment plant (Fig. 1a). Al2O3-based catalyst is the most widely applied ozonation catalyst with a market share of 58%. Our previous work found that the predominant material deposited on the surface and pores of the waste ozonation catalyst was biological secretions, specifically extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)7. This is mainly attributed to the catalyst trapping microbial secondary metabolites released from the front-end biological treatment unit during catalytic ozonation. The EPS naturally exhibits strong adhesion to the catalyst’s supporting material, causing catalyst deactivation. But it also shows great potential as a carbon source to produce carbon-supported catalysts. Furthermore, the diverse array of functional groups (such as aromatic structures, carboxyl, hydroxyl, methoxy, peptide carbonyl, and phenolic groups) provides various adsorption sites for EPS8. EPS adsorption could also promote the dispersibility of metal nanoparticles and improve their stability9. Inspired by the properties of EPS, our proposed innovative approach is to leverage the deposited EPS from waste catalysts, in conjunction with the metal species, to fabricate carbon-supported nano-single-atom-site catalysts (NSASCs) for enhanced catalytic performance.

a Manual clearing, bagging, and collecting of waste catalysts. b Schematic illustration of a waste catalyst regeneration strategy. c SEM image, (d) HRTEM image (Inset: the size distribution of Cu SAs/NPs), (e-f) Aberration-corrected HAADF–STEM images, (g-h) HRTEM images of Cu (111) and C (002), and (i) HAADF–STEM image with EDS mappings of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 sample.

The primary barrier to catalysts application on a large scale is the balancing dilemma of pursuing better catalytic activity and keeping the stability of catalysts under working conditions. NSASCs that incorporate both nanoparticles (NPs) and single-metal-atom (M1) sites are considered a promising solution to the activity–stability tradeoff under operational conditions10. NSASCs combine the advantages of both nanocatalysts and single-atom catalysts by adsorbing different types of reactants via the electron-deficient M1 sites and the electron-rich NP sites11,12,13, resulting in synergistic catalytic effects. Zero-valent metal atoms in NSASCs exhibit high instability, necessitating bonding with link atoms such as C, N, O, and S on the support to form a stable coordination environment14,15,16,17,18. In recent years, increased attention has been paid to the research of biomass-derived carbon materials that serve as excellent support of NSASCs due to the advantages of biomass as a carbon source, such as low cost, environmental friendliness, renewability, and the presence of abundant surface functional groups19,20,21,22. Wan et al. synthesized Cu sub-nanoparticles (<1.0 nm) carbon catalysts from sawdust waste, revealing that the Cu‒V‒C (V represents vacancy defects) configuration could stabilize Cu sites due to the vacancy defects of biomass-derived carbon23. Self-doped EPS from waste ozonation catalysts during long-term operation inherently possess elements such as C and N, expected to act as biomass for carbon-based catalysts synthesis, converting waste ozonation catalysts into highly active and stable NSASCs.

Here we show a regeneration method for ozonation catalysts that combines wet chemical impregnation and carbonization to achieve the controllable synthesis of NSASCs, Cu@GC-Al2O3, by in situ carbonization of self-doped EPS on waste catalysts. Catalyst characterization indicated that the regeneration strategy integrates a robust, high-surface-area support Al2O3, along with graphitic carbon (GC) for active metal immobilization and dispersion. It ensures stable localization of zero-valent metal atoms Cu with both Cu–C3 single atoms (SAs) and Cu–Cu NPs onto the composite support GC-Al2O3, which act synergistically in the nonradical-dominated pathway, exhibiting superior catalytic activity and stability than the pristine fresh catalyst in catalytic ozonation. Furthermore, the life cycle assessment (LCA) results confirm that catalyst regeneration provides significant environmental and economic benefits. The regeneration strategy we investigate proves to be a promising approach for reactivating waste catalysts. Crucially, the concept of recycling self-doped biological secretions provides a perspective for electronic modulation and modification of materials in related fields, promoting waste recovery and sustainable development in different industries.

Results

Synthesis and structure identification of Cu@GC-Al2O3 NSASCs

In our prior investigation, the decrease in catalyst efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the presence of trace metals (Supplementary Table 2) were ascribed to the adsorption and deposition of negatively charged biological secretions—specifically EPS—on the catalyst surface led to significant active-site blockage of catalysts23. To address this problem, we developed a regeneration strategy combining incipient-wetness impregnation (IWI) with carbonization. This strategy converts EPS on the surface and pores of the waste catalyst into GC, facilitating the controlled synthesis of Cu nano-single-atom-site on the GC-Al2O3 framework (Cu@GC-Al2O3). Specifically, as illustrated in Fig. 1b, the waste catalysts were impregnated in a Cu2+ solution of 3.0 wt.% for 8.0 h and then dried to obtain precursors. Subsequently, the precursors were pyrolyzed at 600 °C for 4.0 h under an N2 atmosphere to yield regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalysts. Regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3 exhibits abundant mesopores and a large surface area (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3) illustrated the oblate and helical structures of Cu@GC-Al2O3, consistent with the proposed GC by Wu et al.24. Moreover, Fig. 1h showed lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.34 nm, corresponding to the C (002) plane, further confirming the GC structure formed from EPS carbonization25. The Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst underwent further characterization to elucidate the successful preparation of NSASCs. Supplementary Table 4 shows that Cu contents on the surface (1.0 mm diameter) and inner part (1.0 mm diameter) were 2.74 and 2.62 wt.%, respectively, implying the uniform distribution of active Cu metal. The SEM-energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mappings (Supplementary Fig. 4) of entire cross-section of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst further supported the uniform dispersion of Cu species. Atomic clusters with an average dimension of 10.0 nm (determined by counting 900 Cu SAs/NPs) on Cu@GC-Al2O3 were observed in a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) image (Fig. 1d). An aberration-corrected with high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM) image (Fig. 1e, f) exhibited a high density of small and large bright spots. Among them, the isolated metal atoms appeared as uniform and low-intensity dots, while NPs showed larger and brighter aggregates, verifying the dispersion of Cu species as SAs and NPs on the support. A STEM image (Fig. 1g) displayed lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.21 nm, corresponding to the metallic Cu (111) plane26. HAADF–STEM mapping and Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6) and further reveal the existence of isolated Cu atoms in Cu@GC-Al2O327,28,29. However, it is noteworthy that the elemental mapping (Fig. 1i) presented uniform C, O, and Cu distributions, while no N element was observed, suggesting that N was lower than detect limitation and it has minor impact on the local coordination environment of surface Cu species in our study.

To clarify the origin of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 structural assembly, Cu@GC-Al2O3 composites were investigated by Raman spectra, zeta potential testing, X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS), and thermogravimetry analysis-mass spectrometry (TGA-MS). The intensity ratio of D2 to G bands (ID2/IG) derived from Raman spectra serves as a reliable indicator for assessing structural defects and crystalline qualities in carbon-based materials27,30. Raman ID2/IG ratio decreased from 1.1211 for GC-Al2O3 to 0.6034 for Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that the incorporation of Cu species erased partial defects and enhanced graphitization. Similarly, the ID2/IG ratios of Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalysts regenerated at different temperatures (600 °C, 700 °C, and 900 °C) showed a positive correlation with the catalytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating that the material exhibited the highest graphitization at 600 °C. The broad 2D band around ~2610 cm⁻¹ reflects layer-dependent features31, and the I2D/IG ratio of 0.32 further indicates a multilayer GC structure, in agreement with previous reports suggesting that I2D/IG values below 1.0 correspond to multilayer graphene systems32. The +0.15 eV shift in Al 2p XPS of GC-Al2O3 relative to the fresh catalyst (Fig. 2b) and the negative shift of C‒O peak in C 1 s XPS (Supplementary Fig. 10) mean that electrons are transferred from the Al‒O bond towards the highly electronegative GC33, indicating the formation of partial Al‒O‒C covalent bonds. This phenomenon is similar to one in which Al2O3 induces the orderly deposition of edge-rich graphene carbon to form covalent bonds34. TGA-MS analysis showed that GC@GC-Al2O3 had no detectable CO2 release peak over 501.00 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11), confirming the structural stability of the material. Thus, this Al‒O‒C covalent connection facilitates the improvement of interface bonding strength and overall mechanical properties in the composite support34, consistent with the results that the GC-Al2O3 catalyst exhibited mechanical strength superior to that of pure Al2O3 (Supplementary Table 5). In the pH range of 3 to 9, zeta potential values of GC solutions were all negative, while those of Al2O3 solutions were all positive (Supplementary Fig. 12). This observation underscores the critical role of electrostatic adsorption driven by surface charge density differences in stabilizing heterostructure interfaces35. Moreover, the TGA-MS results showed the loss of NH3 and H2O from GC-Al2O3 was almost twice that from Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 13), as H2O was generated simultaneously once N-containing products were reduced to NH336,37. This is consistent with a red shift in the NH2 or NH peaks and the OH peak of Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 14). The NH2 (or NH) and OH groups that can act as proton acceptors or donors24,38 provided evidence of hydrogen-bonding interactions between GC and Al2O3. In summary, the formation of the GC-Al2O3 composite support might rely on a combination of covalent connection, electrostatic interaction, and hydrogen bonding between Al2O3 and GC. The introduction of Cu promotes the hydrogen-bonding interactions and the graphitization of GC-Al2O3.

a Raman spectra. b High-resolution Al 2p XPS spectra. c Thermogravimetry analysis-mass spectrometry (TGA-MS) signal profiles (NH3: m/z = 17). d Cu 2p XPS spectra of Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalysts (Inset: Cu LMM Auger spectra). e Normalized Cu K-edge XANES spectra and (f) corresponding k3-weighted Fourier Transform spectra. g EXAFS fitting curve in R space of Cu@GC-Al2O3 site (Inset: the proposed Cu–C3 and Cu-Cu coordination environment). h Wavelet transform of Cu foil, CuPc, CuO, and Cu@GC-Al2O3. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

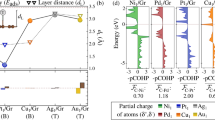

To further elucidate the valence states and local coordination environment of Cu resulting from carbothermal reduction, X-ray diffraction (XRD), XPS, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) analyses were conducted. As shown in Fig. 2d, the Cu 2p XPS spectra of Cu@GC-Al2O3 present two sets of characteristic peaks at binding energies of Cu 2p3/2 (932.83 eV) and Cu 2p3/2 (934.74), corresponding to Cu+/Cu0 and Cu2+ species, respectively15,39. Cu0 and Cu+ were distinguished through Cu-LMM Auger spectra (inset, Fig. 2d), which exhibited a Cu0 peak (918.0 eV) without the Cu+ peak. The XRD results of Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 15) further confirm that the presence of Cu element in the form of Cu0 (JCPDS No. 70-3039)26,40. The Cu2+ signal might be ascribed to the oxidation of Cu0 near the catalyst surface, given that XPS only probed 10 nm below the sample surface35,41. Notably, the predominant presence of thermodynamically stable Cu0 species42 contributes to the stability of Cu@GC-Al2O3. Thus, we can infer the low valance state of Cu species (close to 0)43, which is further evidenced by the X-ray absorption near edge structures (XANES) (the dotted box in Fig. 2e). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) curve of Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Fig. 2f) showed peaks at 1.47 and 2.27 Å, assigning to the first shell Cu–C/N/O scattering and Cu−Cu coordination, respectively. This consistent with the previously reported Metal-N/C/O elements (M-N/C/O) coordination structures for such catalysts15,16,44,45. The Wavelet transform (WT) plot of Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Fig. 2h) displayed an intensity maximum at 7 Å−1 and a weak peak at 4 Å−1, revealing that the number of Cun-Cun clusters in Cu@GC-Al2O3 was significantly higher. EXAFS fitting results showed that the coordination number of Cu–C/N/O (2.8) is between that of CuO (CN = 2.0) and CuPc (CN = 4.0), with the bond length (1.93 Å) slightly shorter than that of CuO (1.96 Å) (Supplementary Table 6). Further structural modeling for a single Cu site was calculated using density functional theory (DFT), and the results showed that the Cu1–C3 configuration aligned well with the EXAFS fitting results compared to Cu–C2N1 and Cu–C1N2. (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Figs. 17–19, and Supplementary Table 7). The weak signal of N 1 s XPS (Supplementary Fig. 20) and the content of heteroatoms (N, P, and S) well below 0.5% (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9) indicated by quantitative elemental analysis suggests that heteroatoms play a minor role in the catalyst structure. Thus, zero-valent metal Cu was successfully dispersed on the composite support of the GC-Al2O3 composite in the form of Cu1–C3 and Cun–Cun.

Pilot-scale demonstrations

Our catalytic ozonation bench experiments showed that the average total organic carbon (TOC) removal of the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system was 59.11%, significantly higher than that of the ozonation with waste catalyst (−53.97%) and GC-Al2O3 catalyst (41.85%) (Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Note 6). This demonstrates the effectiveness of the regeneration strategy in recovering catalyst performance and the contribution of Cu as potential active sites. The catalytic ozonation activity and stability of Cu@GC-Al2O3 in the advanced treatment of actual petrochemical secondary effluent (PSE) were further demonstrated using a pilot-scale reactor for 6 months (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Note 6). As shown in Fig. 3b, c, the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalytic ozonation system exhibited favorable performance in long-term operation. The average chemical oxygen demand (COD) of effluent from the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system decreased deeply from 79.56 mg L−1 to 30.01 mg L−1, while the average COD of effluent from the ozonation (O3) alone and the fresh catalyst/O3 systems were 60.24 mg L−1 and 40.69 mg L−1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 23). Besides, it has been shown that pollutant adsorption on the catalytic surface contributes to the catalytic reaction46,47. Compared with fresh catalyst (adsorption 14.08%) (Supplementary Fig. 24 and Supplementary Table 10), the introduction of GC layers in the regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3 (adsorption 40.53%) enhanced adsorption performance. The ozone-utilization efficiency, expressed as ΔCOD/ΔO348 (Fig. 3d), was found to be 1.14 in the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system as compared to 0.84 using fresh catalyst and 0.45 for O3 alone. Supplementary Table 11 shows that the ozone-utilization efficiency of using Cu@GC-Al2O3 in our ozonation-based pilot-scale application was 47.37‒76.32% higher than the values found in other studies. This finding implies that the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst offered a highly accessible surface area and numerous exposed active sites, facilitating the mass transfer and O3 decomposition. It is further supported by the results (Supplementary Fig. 25) that Cu@GC-Al2O3 exhibited the fastest O3 decomposition rate (k = 1.714 min−1). Additionally, as Cu content rises from 0.5 to 5.0 wt.%, the catalyst activity further increases with a strong positive correlation (R2 = 0.87) (Supplementary Fig. 26). This suggests that Cu SAs/NPs anchored on the carbon skeleton serve as primary active sites. The insignificant increase in Cu5.0@GC-Al2O3 catalyst activity is due to the formation of substantial Cu NPs over Cu (Supplementary Fig. 26c). Moreover, the superior electrochemical performance of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 27) supported the efficient electron transfer from Cu@GC-Al2O3 to O3, generating various active species for pollutant degradation.

Catalytic ozonation pilot-scale demonstration equipment (a). Changes in long-term water quality indexes, including chemical oxygen demand (COD) (b), total organic carbon (TOC) (c), and ozone-utilization efficiency (d) by the catalytic ozonation of PSE. Reaction conditions: catalyst filling rate = 50%, O3 dosage = 50 mg L−1 h, O2 flow rate ≈ 20 L min−1, influent flow rate = 180 L h−1, hydraulic retention time = 0.95 h, pH not adjusted. The error bars in (b−d) represent the standard deviations of triplicate tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The COD and TOC removal efficiencies stabilized at ~60% and ~56% in the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalytic ozonation system during 6-month pilot-scale demonstrations, respectively (Fig. 3b, c), giving evidence of the excellent stability and reusability of Cu@GC-Al2O3. Notably, no shedding particles were observed in the effluent during catalytic ozonation (Supplementary Fig. 28), suggesting that Cu@GC-Al2O3 presents strong mechanical properties. SEM and HAADF-STEM analyses (Supplementary Fig. 29) detected no significant changes in surface properties or Cu atoms after the 6-month operation. An important advantage of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst is its resistance to metal leaching, evidenced by an average Cu concentration of only 12.44 ug L−1 in the effluent (Supplementary Fig. 30), which is considerably lower than the total copper emission limit for drinking water (1300 ug L−1) stipulated by the US Environmental Protection Agency45. The minimal leaching of Cu is ascribed to the excellent oxidation resistance of Cu (111)40 and the tight constraint of Cu NPs by the Cu‒C bond configuration (Supplementary Fig. 16b). Additionally, Supplementary Table 5 shows that the remarkable strength of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst resulted from the enhanced graphitization of the biological secretions by Cu, leading to a more robust GC-Al2O3 framework. This is further supported by the positive correlation between the ID2/IG ratio and the catalytic activity of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 9). These results demonstrate the excellent activity and stability of Cu@GC-Al2O3 NSASCs in catalytic ozonation for the removal of refractory organics in wastewater.

Catalytic mechanism

To clarify the underlying reasons for the remarkable activity of the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system for actual wastewater treatment, types of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were identified in the bulk phase and on the catalyst surface via electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), reactive oxygen probes, in situ Raman measurements, and quenching experiments (Supplementary Notes 3 and 7). Figure 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 31 demonstrated the absence of •OH signal, whereas the presence of O2•– and 1O2 signals was found in the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system, suggesting the generation of O2•– and 1O241. Figure 4c found that the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system generated substantially more O2•– (89.08 μM) than the O3 alone system (2.10 μM), and 1O2 concentration (198.25 μM) is three times that of the O3 alone system, emphasizing the superior reactivity of Cu–C3 or Cun–Cun sites in O3 dissociation to produce O2•– and 1O2. In addition to the ROS, in situ Raman spectra of Cu@GC-Al2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 32) presented a new band at 949 cm−1 with ozone aqueous solution, implying the generation of surface-adsorbed oxygen species (*Oad). The reduction of adsorbed oxygen (531.77 eV)49 content in Cu@GC-Al2O3 after the reaction further supported the involvement of *Oad (Supplementary Fig. 10f). *Oad features a high oxidation potential of 2.43 V, facilitating the attack of aliphatic compounds containing saturated C–C bonds during advanced oxidation processes50,51. Besides, it has been reported that 1O2 is generated through the oxidation of O2•– via one-electron transfer (Supplementary Note 1)52. The contributions of O2•–, *Oad, and 1O2 for organic removal (phenol, namely PhOH, as the target pollutant) were further evaluated through quenching experiments. tert-Butanol (TBA) and methanol (MeOH) react rapidly with •OH in solution and on the catalyst surface, respectively50,53. The presence of TBA and MeOH barely reduced PhOH removal, indicating that •OH groups were not involved in PhOH degradation (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 33). The addition of 1,4-benzoquinone (p-BQ, scavenging O2•–)41 and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, scavenging *Oad)50 showed different decreases in PhOH removal (Fig. 4d), validating the contributions of O2•– and *Oad to PhOH degradation. A strong inhibitory effect on PhOH degradation was observed during the reaction system with furfuryl alcohol (FFA, scavenging 1O2)19,41, confirming that 1O2 is the dominant active species in organic degradation. Therefore, the degradation of organics by catalytic ozonation with the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst probably represented a synergistic oxidation pathway that relies on both radical (O2•–) and non-radical oxidation (*Oad and 1O2). Previous studies have found that non-radical oxidation pathways mediated by 1O2 reduce the interference of anions in the environmental background53,54. The Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system showed only a 1.75%‒7.07% reduction in TOC removal with the addition of NO3−, Cl−, SO42−, and HCO3− in PSE (Supplementary Fig. 34), confirming its excellent anti-interference properties.

a EPR analysis for O2•– detection with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as a trapping agent. b EPR analysis for 1O2 detection with 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinol (TEMP) as a trapping agent. c ROS production. d PhOH degradation processes in the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system. e Relative energy profile of the proposed intermediates and transition state (TS) in the interaction of O3 and the Cu1–C3 or the Cun–Cun. f Relative energy profile of the proposed intermediates and TS in the interaction of O3 and the Cu1–C3–*Oad or Cun–Cun–*Oad. g The mechanism of Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 reaction. The error bars in (c, d) represent the standard deviations of triplicate tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Utilizing DFT calculations within the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), we unveiled the synergistic transformation pathway of O3 into radical and non-radical ROS at the atomic level. O3 rapidly bonded with the central Cu atom in Cu1-C3 SAs (or Cun–Cun NPs), yielding Cu1–C3–*Oad (or Cun–Cun–*Oad) and free 1O2 species (Fig. 4e). The production of Cu1–C3–*Oad requires overcoming an energy barrier of 3.06 eV, which is lower than the production of Cun-Cun–*Oad (3.34 eV). Furthermore, Supplementary Fig. 35 shows that Cu atoms closer to carbon units in Cun–Cun NPs were more positively charged (+0.2582, +0.0014, and −0.0413), strongly explaining the easier formation pathway of *Oad at the Cu1–C3 site compared to the Cun–Cun site. In addition, *Oad, a crucial intermediate in catalytic reactions, could react with O3 molecules to form O2•– and 1O250,55. Figure 4f and Supplementary Fig. 36 demonstrated that O3 was captured by *Oad to generate O2•– and 1O2 species, subsequently released into the bulk solution. The generation of 1O2 species and O2•–species from Cun–Cun–*Oad requires a lower energy barrier of 2.44 eV and 2.51 eV, respectively, compared to Cu1–C3–*Oad (4.31 eV and 4.34 eV, respectively). Therefore, in the Cu@GC-Al2O3/O3 system, the Cu1–C3 sites promoted the formation of *Oad, while Cun–Cun sites triggered the generation of O2•– and 1O2 from *Oad (Fig. 4g). Furthermore, we summarized the activation pathways of O3 at the active sites on the catalyst surface schematic diagrams (Supplementary Fig. 37): (i) O3 adsorption on electron-rich Cu-C3 and/or Cun-Cun sites, (ii) electron transfer to form Cu‒C3‒*Oad and/or Cun‒Cun‒*Oad intermediates, (iii) Subsequent reaction of these intermediates with O3 to decompose into 1O2 (major) and/or O2•–. Cu1–C3 SAs and Cun–Cun NPs synergistically improved the catalytic ozonation activity of the Cu@GC-Al2O3 NSASCs.

LCA and economic assessment

To confirm the potential of the proposed regeneration strategy as a sustainable alternative to waste catalysts, we conducted a comparative analysis between two approaches: (1) Landfill disposal of waste catalysts and the production of fresh catalysts (disposal–production); (2) Regeneration from waste catalysts to self-doped Cu@GC-Al2O3 NSASCs through the pyrolysis of biological secretions (regeneration). The assessment was conducted based on the application of 27,662 tons of Al2O3-based catalyst in 84 petrochemical wastewater treatment plants promoted by our research group (Supplementary Data 1). The analysis employed a cradle-to-gate LCA methodology to account for environmental impact56,57. In Fig. 5a, the regeneration approach contributes 83.83%–99.62% less to all environmental impact categories compared to disposal–production approach. Particularly noteworthy is the superior performance of the regeneration strategy in reducing global warming potential (89.79% lower than disposal–production). Specifiof cally, carbon emissions from Al2O3 support preparation and IWI in the fresh catalyst production are 4.53 and 1.67 times higher than the total emissions from the regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 38). The significant reduction in carbon emissions during IWI in the Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst is mainly attributed to a 5.0 wt.% decrease in the required Cu loading, achieved through the pyrolysis of biological secretions for Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst preparation. Furthermore, the carbon footprint analysis (Fig. 5b, c) shows that IWI (including electric 33.95% and copper ore 15.91%) is the major contributor to regeneration, while the main source of disposal–production is Al2O3 support preparation (including electric 13.23%, natural gas 7.98%, and NaCl materials 30.13%). This aligns with a study on waste-derived catalysts58. Overall, the regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst can utilize raw materials from waste catalysts and requires lower copper loading, significantly reducing the utilization of various chemical agents and energy consumption, thus minimizing environmental impacts.

Supplementary Table 14 presents the subdivided costs for the two strategies of regeneration and disposal–production. The total cost for these two strategies, implemented in 84 petrochemical wastewater treatment plants, amounts to US$87,525,198.23 and US$48,220,834.44, respectively. This signifies a 44.91% reduction in costs with this regeneration strategy compared to disposal–production strategy. Specifically, the regeneration strategy not only reduces the production of carrier (25.71%) but also avoids the landfill disposal of wasted catalysts (13.30%). These results emphasize the potential of the proposed regeneration strategy for waste catalysts, warranting further development from both economic and environmental perspectives.

Discussion

Industrial wastewater treatment plants with catalytic ozonation and its combined process as advanced treatment units produce over one million tons of waste catalysts annually in China3. However, the present catalyst-activity recovery strategy, such as in-situ backwashing, is energy-consuming and environmentally polluting, which slows down the achievement of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. Here, we proposed a greener catalyst regeneration strategy, which overcomes the unsustainable limitations of carbon nanomaterials that feedstock derived from commercial chemicals (Supplementary Table 15). It is worth noting that all petroleum refining waste catalysts could be applied to this regeneration strategy, underscoring the application potential of this innovative strategy.

Since in-situ backwashing regeneration not only presents low catalyst efficiency, but also causes metal resource loss and secondary pollution5,6,7,59, it is challenging to develop efficient and green catalyst regeneration technologies. This work, unlike most reported Cu SACs on graphene or C3N4, utilizes biological secretions doped from waste catalysts as a carbon source to regenerate into Cu NSASCs. This is the demonstration of converting waste AOP catalysts into NSASCs via bio-carbonization. It is worth noting that over one million tons of waste catalysts could be recycled annually in China alone4, underscoring the application potential of this innovative strategy. Furthermore, as shown by cradle-to-gate LCA, our strategy presents a promising alternative to landfill disposal of waste catalysts, addressing both economic and environmental concerns for society.

To validate the generality of our work, we analyzed another sample from a petroleum refining industry wastewater treatment plant in China (see Supplementary Figs. 39‒40 and Supplementary Table 16 for details). Despite elemental variation in waste catalysts due to the differences in wastewater sources and treatment processes from the two plants, the waste ozonation catalysts adsorbed substantial EPS, an inherent component of biological effluent. The NSASC-2 synthesized from this sample demonstrated a consistent coexistence structure of single-atom and clusters (Supplementary Fig. 39c), and the TOC removal of PSE remained above 50% in 30 cycles, reflecting its excellent activity and stability. (Supplementary Fig. 40).

To extend the generality of our work, we verified the function of EPS secreted by pure cultured microorganisms on atomic dispersion. Typical Pseudomonas and Bacillus subtilis 168 among Gram-negative bacteria and Gram-positive bacteria were respectively selected to culture and produce EPS, and then prepared into Cu@P-EPS-Al2O3 and Cu@B-EPS-Al2O3 through IWI with carbonization (Supplementary Fig. 41 and Supplementary Note 9). Supplementary Fig. 42 shows the remarkable dispersion ability of EPS on Cu, yielding NSASC with Cu1 and Cun. The result gives a great hint to the related material research field, that is, by adjusting the pure culture bacteria to secrete different EPS, we can adjust and realize the atomic dispersion of metal, and prepare fine materials for medicine, industrial catalysis, and other fields.

Methods

Materials

The fresh catalysts (γ-Al2O3 particles as supports and Cu oxides as active components) used in this study were purchased from Kaisai Chemical (Dalian) Co., LTD, and have become waste catalysts after 5 years of continuous operation in the catalytic ozonation unit of China’s largest petrochemical wastewater treatment plant. The waste catalysts were obtained from the same batch sampled on 14th April 2021, with a detailed sampling process depicted in Fig. 1a. The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figs. 1a and 3a. Other materials and reagents are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

Regeneration of catalysts

The waste catalyst was first pretreated by naturally air-drying and then dried in an oven at 105 °C to a constant mass. This step cleverly preserved the self-doped biological secretions (mainly EPS) of the waste catalyst as carbon precursors during the pyrolysis process. The pretreated waste catalyst served as the adsorbent with a water absorption of 1.67 g mL-1. Cu2+ was impregnated controllably by the IWI method based on the result of water absorption, effectively preventing the loss of the deposited biological secretions in the waste catalyst. 100 g of pretreated waste catalysts were dispersed in a 60 ml solution of 3.0 wt.% Cu2+ with continuous shaking at 100 rpm for 1 h, and then left to stand for 8 h to complete the impregnation. The impregnated catalysts were subsequently dried in an oven at 105 °C to obtain precursors. These precursors were pyrolyzed by heating to 600 °C in a tubular furnace under an N2 atmosphere with a heating rate of 10 °C min-1 and kept for 4 h. The regenerated Cu@GC-Al2O3 catalyst was obtained without any further treatment. Regenerated catalysts were prepared with Cu2+ solutions of 0.5, 1.0, and 5.0 wt.%, noted as Cu0.5@GC-Al2O3, Cu1.0@GC-Al2O3, and Cu5.0@GC-Al2O3, respectively. The synthesis of regenerated GC-Al2O3 did not involve the IWI of Cu2+ solution before pyrolysis, compared with the Cu@GC-Al2O3 regeneration process.

Characterization

HRTEM and aberration-corrected HAADF–STEM images were collected with an aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (JEM ARM 200 F, Japan) with a cold field emission gun operated at 80 kV. XPS analysis was obtained by an ESCALAB 250 X-ray photoelectron spectrometer with Al Kα as the excitation source. The carbothermal reduction of the catalysts was analyzed using TGA-MS (Netzsch STA, Germany). The Cu K-edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectra were collected at the BL14W1 station of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Data reduction, data analysis, and EXAFS fitting were performed and analyzed with the Athena and Artemis programs of the Demeter data analysis packages that utilize the FEFF6 program to fit the EXAFS data27,35 (See the Supplementary Notes 3–5 for detailed analysis).

Theoretical calculations

First-principles calculations were carried out based on periodic DFT using a generalized gradient approximation within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerh exchange correction functional with Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). The wave functions were constructed from the expansion of plane waves with an energy cutoff of 500 eV. Gamma-centered k-point of 3 × 3 × 1 has been used for geometry optimization. The consistency tolerances for the geometry optimization are set as 1.0 × 10−6 eV/atom for total energy and 0.05 eV/Å for force, respectively. To avoid the interaction between the two surfaces, a large vacuum gap of 15 Å has been selected in the periodically repeated slabs. The climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) was used for transition state searching. In free energy calculations, the entropic corrections and zero-point energy (ZPE) have been included. The free energy of the species was calculated according to the standard formula:

Where ZPE was the zero-point energy, ΔH was the integrated heat capacity, T was the temperature of the product, and S was the entropy.

LCA methods

The LCA of the landfill disposal-fresh catalyst production strategy and self-doped biological secretions regeneration strategy was conducted using GaBi 10.5 software, the functional unit (FU) is defined as 27662 tons of catalyst. Inventory analyses for both strategies involved background data from the GaBi and Ecoinvent databases, as well as production data collected from the enterprises. Detailed information is shown in Supplementary Tables 12–13 and Supplementary Note 8.

Data availability

All data provided in this manuscript are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, J. G. et al. Beyond fossil fuel–driven nitrogen transformations. Science 360, eaar6611 (2018).

Kim, D. et al. Selective CO2 electrocatalysis at the pseudocapacitive nanoparticle/ordered-ligand interlayer. Nat. Energy 5, 1032–1042 (2020).

Parvulescu, V. I., Epron, F., Garcia, H. & Granger, P. Recent progress and prospects in catalytic water treatment. Chem. Rev. 122, 2981–3121 (2021).

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China.Annual Report of Ecological and Environmental Statistics in China 2022. https://english.mee.gov.cn/ (2025).

Martín, A. J., Mitchell, S., Mondelli, C., Jaydev, S. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Unifying views on catalyst deactivation. Nat. Catal. 5, 854–866 (2022).

He, C. et al. Catalytic ozonation of bio-treated coking wastewater in continuous pilot- and full-scale system: efficiency, catalyst deactivation and in-situ regeneration. Water Res 183, 116090 (2020).

Jin, X. et al. A thorough observation of an ozonation catalyst under long-term practical operation: deactivation mechanism and regeneration. Sci. Total Environ. 830, 154803 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Microalgal extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and their roles in cultivation, biomass harvesting, and bioproducts extraction. Bioresour. Technol. 406, 131054 (2024).

Xu, N., Zhang, X., Guo, P.-C., Xie, D.-H. & Sheng, G.-P. Biological self-protection inspired engineering of nanomaterials to construct a robust bio-nano system for environmental applications. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2179 (2024).

Liang, X., Fu, N., Yao, S., Li, Z. & Li, Y. The progress and outlook of metal single-atom-site catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18155–18174 (2022).

Cao, L. et al. Atomically dispersed iron hydroxide anchored on Pt for preferential oxidation of CO in H2. Nature 565, 631–635 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Proton capture strategy for enhancing electrochemical CO2 reduction on atomically dispersed metal–nitrogen active sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11959–11965 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Importance of species heterogeneity in supported metal catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5108–5115 (2022).

Ji, S. et al. Chemical synthesis of single atomic site catalysts. Chem. Rev. 120, 11900–11955 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Dynamic behavior of single-atom catalysts in electrocatalysis: Identification of Cu-N3 as an active site for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14530–14539 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Regulating electron configuration of single Cu sites via unsaturated N,O-coordination for selective oxidation of benzene. Nat. Commun. 13, 6996 (2022).

Wan, J. et al. In situ phosphatizing of triphenylphosphine encapsulated within metal-organic frameworks to design atomic Co1-P1N3 interfacial structure for promoting catalytic performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8431–8439 (2020).

Yu, F. et al. Electronic states regulation induced by the synergistic effect of Cu clusters and Cu-S1N3 sites boosting electrocatalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214425 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Water decontamination via nonradical process by nanoconfined Fenton-like catalysts. Nat. Commun. 14, 2881 (2023).

Lei, X. et al. High-entropy single-atom activated carbon catalysts for sustainable oxygen electrocatalysis. Nat. Sustain. 6, 816–826 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Single atom catalysts in Van der Waals gaps. Nat. Commun. 13, 6863 (2022).

Wang, Z., Shen, D., Wu, C. & Gu, S. State-of-the-art on the production and application of carbon nanomaterials from biomass. Green. Chem. 20, 5031–5057 (2018).

Wan, Z. et al. Revealing intrinsic relations between Cu scales and radical/nonradical oxidations to regulate nucleophilic/electrophilic catalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212227 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. 2D heterostructured nanofluidic channels for enhanced desalination performance of graphene oxide membranes. ACS Nano 15, 7586–7595 (2021).

Wang, M.-Q. et al. Synthesis of M (Fe3C, Co, Ni)-porous carbon frameworks as high-efficient ORR catalysts. Energy Storage Mater. 11, 112–117 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Photo-Driven hydrogen production from methanol and water using plasmonic Cu nanoparticles derived from layered double hydroxides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213672 (2022).

Huang, F. et al. Insight into the activity of atomically dispersed Cu catalysts for semihydrogenation of acetylene: Impact of coordination environments. ACS Catal. 12, 48–57 (2022).

Lee, B.-H. et al. Reversible and cooperative photoactivation of single-atom Cu/TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 18, 620–626 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Directly transforming copper (I) oxide bulk into isolated single-atom copper sites catalyst through gas-transport approach. Nat. Commun. 10, 3734 (2019).

Pachfule, P., Shinde, D., Majumder, M. & Xu, Q. Fabrication of carbon nanorods and graphene nanoribbons from a metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 8, 718–724 (2016).

Sun, L. et al. Hetero-site nucleation for growing twisted bilayer graphene with a wide range of twist angles. Nat. Commun. 12, 2391 (2021).

Asif, M. et al. Thickness controlled water vapors assisted growth of multilayer graphene by ambient pressure chemical vapor deposition. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 3079–3089 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. BCN-driven interfacial effect: a novel strategy to remarkably enhance the capacitance of Co3O4/NiO for supercapacitor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 680, 572–580 (2025).

Jiao, Y. et al. Strong and weak interface synergistic enhance the mechanical and microwave absorption properties of alumina. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 680, 1007–1015 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Functional CeOx nanoglues for robust atomically dispersed catalysts. Nature 611, 284–288 (2022).

Lan, T. et al. Unraveling the promotion effects of dynamically constructed CuOx-OH interfacial sites in the selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia. ACS Catal. 12, 3955–3964 (2022).

Lan, T. et al. Selective catalytic oxidation of NH3 over noble metal-based catalysts: State of the art and future prospects. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 5792–5810 (2020).

Zhao, D. et al. Synergy of dopants and defects in graphitic carbon nitride with exceptionally modulated band structures for efficient photocatalytic oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903545 (2019).

Sun, T. et al. Engineering of coordination environment and multiscale structure in single-site copper catalyst for superior electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Nano Lett. 20, 6206–6214 (2020).

Kim, S. J. et al. Flat-surface-assisted and self-regulated oxidation resistance of Cu(111). Nature 603, 434–438 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Janus electrocatalytic flow-through membrane enables highly selective singlet oxygen production. Nat. Commun. 11, 6228 (2020).

Bai, X. et al. Dynamic stability of copper single-atom catalysts under working conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17140–17148 (2022).

Zeng, L. et al. Synergistic effect of Ru-N4 sites and Cu-N3 sites in carbon nitride for highly selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to methane. Appl. Cata. B Environ. 307, 121154 (2022).

Chung, H. oonT. et al. Direct atomic-level insight into the active sites of a high-performance PGM-free ORR catalyst. Science 357, 479–484 (2017).

Xu, J. et al. Organic wastewater treatment by a single-atom catalyst and electrolytically produced H2O2. Nat. Sustain. 4, 233–241 (2021).

Sun, X., Wu, C., Zhou, Y. & Han, W. Using DOM fraction method to investigate the mechanism of catalytic ozonation for real wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 369, 100–108 (2019).

Miklos, D. B. et al. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – a critical review. Water Res 139, 118–131 (2018).

Wei, K. et al. Ni-induced C-Al2O3-framework (NiCAF) supported core-multishell catalysts for efficient catalytic ozonation: a structure-to-performance study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6917–6926 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Mechanisms of thermal decomposition in spent NCM lithium-ion battery cathode materials with carbon defects and oxygen vacancies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 21362–21373 (2024).

Ren, T. et al. Single-atom Fe-N4 sites for catalytic ozonation to selectively induce a nonradical pathway toward wastewater purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3623–3633 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Tailored synthesis of active reduced graphene oxides from waste graphite: Structural defects and pollutant-dependent reactive radicals in aqueous organics decontamination. Appl. Cata. B Environ. 229, 71–80 (2018).

Zhang, L. S. et al. Carbon nitride supported high-loading Fe single-atom catalyst for activation of peroxymonosulfate to generate 1O2 with 100% selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21751–21755 (2021).

Liu, Y., Chen, C., Duan, X., Wang, S. & Wang, Y. Carbocatalytic ozonation toward advanced water purification. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 18994–19024 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Selective removal of organic pollutants in groundwater and surface water by persulfate-assisted advanced oxidation: The role of electron-donating capacity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 13710–13720 (2023).

Yu, G. et al. Insights into the mechanism of ozone activation and singlet oxygen generation on N-doped defective nanocarbons: a DFT and machine learning study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7853–7863 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Evolving wastewater infrastructure paradigm to enhance harmony with nature. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq0210 (2018).

Meng, X., Yang, J., Ding, N. & Lu, B. Identification of the potential environmental loads of waste tire treatment in China from the life cycle perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 193, 106938 (2023).

Gu, C.-H. et al. Upcycling waste sewage sludge into superior single-atom Fenton-like catalyst for sustainable water purification. Nat. Water 2, 649–662 (2024).

Kuang, Y. et al. Ultrastable low-bias water splitting photoanodes via photocorrosion inhibition and in situ catalyst regeneration. Nat. Energy 2, 16191 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (No. 8242044, C. Wu) and the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2020YFC1806302, C. Wu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., C.Wu., and C.Wan. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. L.F., Y.Yuan, Y.Yu, X.J., and Z.L. fabricated the samples and conducted the structure characterization. Y.Zeng performed LCA assessment. X.L. conducted electrochemical experiments. Y.Sun conducted the DFT simulation work. M.X., P.W., H.X., Y.Song, Q.H., and Y.Zhou contributed to the experimental design and data analysis. M.L. and C.Wu. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Fu, L., Yuan, Y. et al. Self-doping of biological secretions for waste catalyst reuse. Nat Commun 16, 10823 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66131-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66131-x

This article is cited by

-

Biomass-Derived Green Synthesis of ZnO/NiO Nanocomposite from Salsola baryosma Extract for Electrocatalytic Formaldehyde Oxidation

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2026)