Abstract

Intricate interactions between light and matter form the foundation of photonics innovation. This study presents a light-induced self-adaptive growth strategy for engineering multiscale ordered photonic crystal structures in perfluorosulfonic acid ionomer films. By incorporating anthracene-functionalized quaternary ammonium salts into the polymer matrix, UV irradiation triggers anthracene photodimerization, initiating localized phase separation and directional aggregation of nanoparticles along the light propagation path. The resulting nanoparticle columns exhibit programmable vertical or tilted configurations controlled by the incident light angle, establishing a bidirectional feedback loop where evolving structures modulate light propagation to guide subsequent growth. Using patterned photomasks, angle-dependent structural colors are achieved through selective reflection governed by incomplete photonic bandgaps. Furthermore, anisotropic PC architectures enable tunable light scattering and programmable grating devices, demonstrating potential applications in functional optical materials and LED displays. This fabrication strategy overcomes the static limitations of conventional photonic crystals, providing a versatile platform for creating programmable photonic architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interaction between light and matter has long been a cornerstone of modern photonics1,2,3,4,5. Leveraging its spatiotemporal precision6,7, light excitation enables controlled material restructuring through phase transitions8,9,10,11, molecular rearrangements12,13,14, and nanoscale organization15,16,17,18. These light-induced structural adaptations correspondingly modify optical phenomena including reflective properties19,20,21, and emissive behaviors22,23,24, establishing a dynamic bidirectional relationship where light actively configures and is reconfigured by the evolving material architecture. This mutual interaction is pivotal for advanced technologies such as adaptive optics25,26,27, reconfigurable photonic devices28,29,30, and smart displays31,32. For instance, in PCs, the periodic arrangement of dielectric materials generates photonic bandgaps that selectively reflect or transmit specific wavelengths of light33,34,35. The dual capacity to both initiates and continuously regulates structural order via photonic inputs opens avenues for designing optically addressable materials with real-time property tuning. Yet, achieving this dynamic light-structure-light feedback loop remains a significant challenge, as it demands precise spatiotemporal control over both light-driven structural evolution and the resulting optical response.

Natural and synthetic systems provide some examples of light-structure interactions. For example, plant phototropism relies on asymmetric auxin distribution under directional light36,37, causing stem curvature that optimizes light harvesting—establishing a continuous feedback loop where structure modifies light absorption, which further refines growth. Similarly, chameleon skin contains tunable guanine nanocrystals whose light-triggered reorganization alters both color and reflectance38,39, enabling real-time camouflage. In engineered materials, researchers have developed various platforms to harness light for structural control40,41,42,43. For instance, by designing topological PC structures using electron-beam lithography, robust topological resonant modes immune to structural perturbations have been achieved, enabling wavefront manipulation based on disorder44. Likewise, the integration of movable atoms with nanophotonics using optical tweezers has established a promising platform for developing quantum light nodes for large-scale atomic quantum processors45. These examples illustrate light’s versatility in guiding structural evolution and tailoring optical properties46,47. Nevertheless, despite these advancements, critical challenges remain in achieving spatiotemporal control over light-induced structural growth. Specifically: (1) Light-driven structural evolution often introduces scattering or defects that disrupt the optical functionality governed by photonic bandgaps48,49. (2) Light serves merely as a structural initiator50, neglecting bidirectional interactions where structures dynamically modulate light propagation. This unidirectionality hinders the realization of adaptive, feedback-driven photonic materials. (3) Structural evolution and optical feedback face inherent limitations, including energy dissipation51, kinetic metastability52, and multifunctional integration within monolithic systems. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches that enable precise control over light-structure interactions.

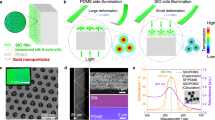

Here, we propose a light-induced self-adaptive growth strategy for generating PC column structures via precise spatiotemporal control of reaction-induced phase separation in perfluorosulfonic acid (PFSA) ionomer films. By integrating An-Am into the polymer matrix enables UV-triggered photodimerization, inducing localized phase separation and directional nanoparticle growth along the light propagation path (Fig. 1). Crucially, the directionality of structural evolution is governed by the angle of incident light, enabling the programmable alignment of PC columns into vertical or tilted configurations. This directional growth is underpinned by supramolecular interactions, where ionic clusters act as nucleation sites for nanoparticle aggregation. In contrast to static systems, our approach establishes bidirectional feedback: the growing structures modulate light propagation, influencing subsequent growth patterns and optical effects. To demonstrate this, we fabricated patterned structures with angle-dependent structural colors using photomasks, wherein selective reflection is governed by PC column orientation. Our strategy, which combining light-guided fabrication with self-adaptive optical responses, paving the way for smart photonic materials capable of real-time environmental adaptation, where light and structure co-evolve in a feedback-driven loop.

a UV-controlled growth of PC particle column structures. b Molecular structure of film constituents and supramolecular interactions between them. c Schematic diagram of the PC particle columns self-adaptive growth mechanism. d 3D fluorescence distribution maps of micro-sized vertical grating (top) and tilted grating (bottom) constructed inside the films. Scale bars: 10 μm. e Complementary PC patterns controlled by different modes of particle column structure within the film and corresponding 3D fluorescence distribution maps. Intermediate scale bar: 1 cm, Left/right scale bars: 5 μm.

Results

Light-induced adaptive growth strategy for multiscale ordered structure

Figure 1 illustrates the strategy for fabricating multiscale ordered structures in films based on light-induced adaptive growth of nanoparticles. PFSA is a polymer composed of hydrophobic backbone and hydrophilic side chains, which form distinctive ion clusters upon film formation53,54. Its low refractive index and excellent shape memory properties made it the ideal polymeric material. An-Am was chosen as a UV-responsive component critical for phase separation, which synthesis and characterization were provided in detail in Supplementary Fig. 1-4. After mixing An-Am containing anthracene group with PFSA (named as PFSA-An), ammonium ions and sulfonic acid ions formed ionic clusters through supramolecular interaction (Fig. 1b), accompanied by the anthracene group into the polymer side chain, while the remaining An-Am was homogeneously dispersed in the film. Upon irradiation of 365 nm UV light at 80 °C, the dimerization of anthracene, triggered the aggregation of ionic clusters, resulting in the formation of nanoparticles (Fig. 1c, Stage 1). This phenomenon was attributed to reaction-induced phase separation, driven by a reduction in entropy. Heating facilitates molecular migration within the PFSA-An film, thereby promoting the formation of microstructures. With prolonged exposure to light, the phase separation progressively developed into larger nanoparticles (Fig. 1c, Stage 2). The difference in refractive index between An-Am (1.45) and PFSA matrix (1.38) in the phase-separated region further creates an optical waveguide, and subsequent particles preferentially grow in the direction of irradiation, eventually forming PC particle column structures (Fig. 1c, Stage 3 and Fig. 1a). Further, the region where the particle column structures are generated is selectively controlled by using a photomask. For example, when the film was selectively irradiated with different angles of UV light through a strip-shaped micron-pitch photomask, we successfully fabricated vertically and tilt-spaced grating structures inside the film, each consisting of several particle columns (Fig. 1d). In addition, by expanding the exposure area using a macroscopic photomask, particle columns with different orientations were successfully fabricated in the same layer of film, allowing precise control of the viewing angle of the complementary structural color pattern (Fig. 1e). The quaternary ammonium salts An-Am required for this strategy were universal, octyl quaternary ammonium salt was used in our experiments unless otherwise specified.

Self-adaptive growth kinetics of nanoparticles

To elucidate the self-adaptive growth mechanism of PC particles, the growth kinetics of the particles were investigated in Fig. 2. Critically, supramolecular interactions between ammonium and sulfonic acid ions served as the foundation for this self-adaptive growth. FT-IR spectra of PFSA-An film demonstrated that an increase of An-Am content caused a shift of the sulfonate vibration peak to lower wavelengths, confirming the presence of these interactions (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the pure PFSA film, sulfonate grafted on the side chain was assembled into ionic clusters, exhibiting an island-like phase structure. In the PFSA-An film, part of An-Am molecules were bound to these ionic clusters to form nano-aggregation, while others were dispersed in the matrix. Upon irradiation of UV light for initial 2 min, the photodimerization of anthracene groups facilitated the formation of nanoparticles from ionic clusters (Supplementary Fig. 6). The enrichment of N and S elements in these particles stems from the presence of strong supramolecular interactions between ammonium and sulfonate ions, while the growth of free An-Am into the ion clusters leads to the aggregation of additional Cl elements. In contrast, no significant nanoparticle structures or elemental aggregation were observed before UV irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Extending irradiation to 10 min promoted nanoparticle aggregation and proliferation (Fig. 2a). No crystals were detected by XRD testing during this process (Supplementary Fig. 8), further confirming that the particle structure is an aggregation of An-Am rather than crystallization.

a AFM phase diagrams of PFSA and PFSA-An under different UV illumination times. b Changes in Tg of PFSA and PFSA-An under different UV exposure time. c Variation in fluorescence intensity of PFSA-An film at 413 nm under different UV irradiation times. d Optical photographs of PFSA-An film sections with gradient growth in the particle region at different times of UV irradiation (Numerical unit: μm). e Changes in UV-vis reflectance spectra of PFSA-An film under UV irradiation and photographs of the sample before and after 10 min of irradiation. Scale bar: 1 cm.

DMA measurements traced the film’s glass transition temperature (Tg), revealing molecular chain dynamics during light-induced nanoparticle evolution (Fig. 2b). Two distinct phase transition temperatures were identified in the PFSA film: a high temperature of 135 °C corresponding to the main chain Tg, and a low temperature of 20 °C associated with the side chain Tg. The incorporation of anthracene groups into the side chain enhanced the chain rigidity, resulting in an increase of the side chain Tg to 34 °C. Conversely, free An-Am acted as the small molecular plasticizer, reducing the Tg of the main chain to 125 °C. The photodimerization-induced growth of nanoparticles increased in both the main chain and side chain Tg. As the irradiation time extended, the continuous aggregation of nanoparticles increased the Tg of the main chain and side chain to 153 °C and 81 °C, respectively. Fluorescence spectroscopy was used to further investigate the particle’s self-adaptive growth processes (Supplementary Fig. 9). As photodimerization progressed, the anthracene groups were continuously consumed, theoretically leading to a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity55,56. However, an initial rapid increase was observed at the beginning of the irradiation and then decreased continuously (Fig. 2c). The possible reason for this anomaly was to show that, in the absence of UV irradiation, the anthracene groups were concentrated in ionic clusters. The π-π stacking induces an aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) effect that suppresses the full manifestation of fluorescence57,58,59. Under UV irradiation, anthracene dimerization partially disrupts the ACQ effect, resulting in a temporary enhancement of fluorescence intensity within the initial few minutes. These experimental findings elucidate the particle generation mechanism across multiple dimensions: (1). Initial ionic clusters in film due to supramolecular interactions. (2). The growth of the particles primarily focused on the initial aggregated structures, wherein free Am-Am initially merged following light-induced anthracene dimerization, leading to the subsequent growth of ionic clusters (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The influence of adaptively grown particles on the optical effects of films was explored in a series of experiments. Observation of the vertical cross-section of the sample using a super depth 3D microscope revealed that the particulate region strongly scattered light, appearing whitish. Anthracene absorbed UV energy and produced a shielding effect. In the early stages of UV irradiation, the surface-layer anthracene first absorbed UV energy and underwent a dimerization reaction. After the upper-layer anthracene dimerized, the lower layer began to react, indicating a progressive process. This progression resulted in an increase in the depth of the particles from 41.8 μm to 80.5 μm with prolonged UV exposure (Fig. 2d). In contrast, non-irradiated film remained structurally uniform. The effect of these PC particles on the structural color was assessed by UV-vis reflection spectroscopy (Fig. 2e). The PFSA film exhibited a reflectance of 5.5% at 400 nm and showed no structural color (Supplementary Fig. 11). Similarly, the PFSA-An film also lacked structural color. However, due to absorption by anthracene around 400 nm, its reflectance decreased to 3.3%. After UV irradiation, the PFSA-An film showed a reflection peak at 520 nm and reached its maximum intensity at 15 min, indicating that the increased number of particles enhanced the structural color. The width broadening of the reflection peak suggested a wider particle size distribution during the growth process. A similar trend was observed in PFSA-An film with different An-Am contents under identical conditions. However, when the content increased to 12 wt.%, the reflectance decreased from 12.4% to 11.1%, accompanied by a red shift of 41 nm in the reflection peak. These changes arise from the increased phase separation scale and reduced structural order at higher An-Am concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 12). For the following investigations, PFSA-An with 10 wt.% An-Am content and 10 min of UV exposure were selected, with particle sizes ranging from predominantly 100 to 180 nm (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Bidirectional feedback of light and PC particle column structure

The light-induced growth of the PC structure initiated a bidirectional feedback loop where the evolving nanoparticle columns modulated light propagation to guide their subsequent growth. The reaction-induced phase separation occurred exclusively along the light path, demonstrating a strong dependence on the direction of illumination. Varying the incident light angle enabled precise programming of particle column configurations—producing either vertical or tilted architectures (Fig. 3a). After UV light is scattered by the particle structures, the energy of the UV light along the original optical path remains higher than the energy in scattered directions. As a result, subsequent particles preferentially grow and align along this direction, forming initial particle column structures. Although scattered light would theoretically cause structural disorder, the refractive index difference between the PFSA and An-Am enables the particle columns to function like optical fibers, confining the scattered light within the columns. This creates a bidirectional feedback loop of UV light - particle column, leading to aligned growth of the particle columns along the optical path. For the sake of illustration, we define the direction perpendicular to the film as Mode Ⅰ and the direction inclined to the film as Mode Ⅱ.

a Two modes of UV-induced particle column growth. b SEM images of Mode Ⅰ particle columns distribution in different planes (X-Z plane and Y-Z plane). Scale bars: 5 μm. c SEM images of Mode Ⅱ (45°) particle columns distribution in different planes (X-Z plane and Y-Z plane). Scale bars: 5 μm. d Length (ΔL) variation of particle column growth with different UV exposure times and corresponding laser scattering patterns in Mode Ⅰ. Laser light is perpendicular to surface of sample. Results are shown as mean ± SD, n = 3. e Height (ΔH) variation of particle column growth and the corresponding laser scattering patterns for different UV exposure times in Mode Ⅱ (45°). Laser light is perpendicular to surface of sample. Results are shown as mean ± SD, n = 3. f Laser scattering test method for Mode Ⅰ sample and changes in light scattering patterns at different rotation angles. θR represents the rotation angle of the incident laser. g Laser scattering test method for Mode Ⅱ (45°) sample and changes in light scattering patterns at different rotation angles. θR’ represents the rotation angle of the incident laser.

To further demonstrate the dependence of the particle columns on the direction of UV irradiation, the morphology of the PC columns structure in Mode Ⅰ and Mode Ⅱ were observed by microscope in three views, where the front view, side view, and top view represent the X-Z, Y-Z, and X-Y planes, respectively. For Mode Ⅰ, both front and side views of the PC particle column structure showed a rectangular shape with a width of 1.5 μm, and the internal particles are arranged in a linear configuration. (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 15), and the top view exhibited a uniform circular distribution (Supplementary Fig. 14a), indicating the cylindrical structure. In continuous observation along the Z axis, circular particle distributions were detected at a depth of 5 μm from the surface, which disappeared beyond the length of the particle columns, confirming their vertical alignment (Supplementary Fig. 14c and Movie 1). Interestingly, the width of the circular particles remained consistent and the length (ΔL) grew to 27.5 μm under different UV irradiation times, suggesting that the growth of the PC columns occurred mainly in the length direction (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 14e). In contrast, Mode Ⅱ assumed the dependence of the self-adaptive growth direction on the incidence angle of UV light, so tilting the UV exposure at 45° along the X axis was used to irradiate the film. The front view revealed that the orientation of the PC particle columns closely aligned with the incident angle, while the side view displayed uniformly distributed elliptical aggregates of similar width to those in Mode Ⅰ (Fig. 3c). The top view showed that, rather than circular shapes, the inclined PC structures appeared as parallel short bars (Supplementary Fig. 14b), confirming the presence of tilted columns. The continuous observations along the Z axis also demonstrated that the construction and disappearance of the parallel short bars were similar to those in Mode Ⅰ, with the key difference being their tilted arrangement (Supplementary Fig. 14d and Movie 2). The height (ΔH) increased to 26.2 μm with the increase of UV irradiation time (Fig. 3e). These results support our assumption that the growth of PC particle columns was light direction-dependent. Layer-by-layer scanning of particle columns under two modes, followed by 3D reconstruction, revealed a clear contrast in their orientation (Supplementary Fig. 16). Similarly, PC particle columns with different tilted states were produced by varying the angle of incident UV light at 30° and 60°, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 17).

This bidirectional feedback of light and structure enabled continuous structural adaptation, with the growing columns dynamically influencing light scattering and further reflecting the growth process. We investigated the correlation between the height of PC particle columns and the scattering patterns during their self-adaptive growth under Mode Ⅰ and Mode Ⅱ over UV irradiation times ranging from 2 min to 15 min. Figure 3d illustrates that in Mode I, under continuous UV irradiation, the particle column significantly elongates, triggering a more pronounced Mie scattering effect, ultimately forming a clearly visible circular halo. In contrast, the spatially inhomogeneous scattering effect of the tilted particle columns structure in Mode II (45°) results in a curved arc with two symmetric scattering spots (Fig. 3e). In addition, we further investigated the correlation between the laser scattering pattern and the direction of the particle column by rotating the laser incidence angle. In Mode Ⅰ, the laser was parallel to the PC column (θR = 0°), producing a uniform scattering circular pattern (red frame in Fig. 3f). As the angle of incidence increased, the transmitted laser intersected the PC column (θR > 0°), forming a curved arc with two symmetrical scattering spots. On the contrast, in Mode Ⅱ (45°), a uniform scattering pattern was generated only when the laser was aligned with the direction of the prefabricated PC column (θR’ = 45°), otherwise two symmetrical scattering spots can be observed (red frame in Fig. 3g). Furthermore, much like optical fibers, the particle columns guide light preferentially toward the tilted direction. This behavior leads to the re-emergence of symmetric spots in the opposite direction when the incident angle exceeds 45°. The interconversion between the uniform circular scattering spot and the symmetrical two scattering spots during laser rotation indicates that the scattering patterns are directly correlated with the relative orientation between the laser direction and the particle columns. This relationship allows us to determine the specific orientation mode of the particle columns through laser scattering analysis, and further confirms that the direction of UV light incidence determines the structure of the PC columns.

Based on the aforementioned results, we could programmatically control the orientation of the PC column to achieve the desired tilt angle. These programmed structures demonstrated distinct scattering patterns for transmitted light and exhibited characteristic optical properties. In Mode Ⅰ state, when the film was parallel to the background, it produced strong scattering that completely obscured background details. By tilting the film 30° relative to the background, the scattering effect was attenuated, rendering the font “1896” visible (Supplementary Fig. 18a and Movie 3). In Mode Ⅱ (45°) state, with the film parallel to the background, scattering remained weak, making “1896” clearly discernible. Conversely, when tilted to 45° (matching the prefabricated PC column angle), the font became blurred (Supplementary Fig. 18b). Thus, we could customize the film’s scattering pattern at various angles relating to natural light, creating optical devices capable of on-demand light path adjustment.

Patterned PC structures

The periodic PC particle columns constructed through self-adaptive growth exhibited a significant refractive index contrast with the PFSA-An film, which considerably altered the path of light propagation. This PC-type structure formed the basis for the pattern demonstration. In Fig. 4a, employing mask-assisted UV control, we demonstrated that the PC structure based on Mode I displayed different optical patterns and clear boundaries. In addition, by using a digital greyscale mask (ink-dot modulated light entry), it is even possible to produce complex drawing with a 3D effect. The fluorescence variations of these PC patterns, induced by the dimerization of anthracene, further contributed to the recognition of different PC patterns. This self-adaptive growth mechanism made it more likely that the internal particle structures were ordered along the UV direction, generating an incomplete photonic band gap (PBG), allowing light reflection exclusively along the ordered axis, rendering structural color visible only from that specific direction. In contrast, the absence of a PBG in other directions resulted in no structural color formation, and a scattering whitening effect was exhibited (Fig. 4b). As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 19, PFSA-An films irradiated at three different angles (0°, 30°, and 60°) displayed angle-dependent structure color under white light. Only the films viewed precisely at the incident angle revealed the vibrant structural colors, whereas other angles showed significantly weaker color patterns. We combined Mode Ⅰ and Mode Ⅱ to produce an integrated display pattern with dual PC structures oriented in distinct directions. The ‘SJTU’ pattern was generated during the first exposure, using a UV lamp tilted at 45° through a mask, followed by a second exposure at 0° to create a complementary pattern without a mask. This approach enabled structural color observation from two viewing angles within the same film (0° and 45° shown in Fig. 4c). The second exposure did not alter the growth direction of the first exposed PC structures. Supplementary Fig. 20 showed two different types of self-adaptive growth particle column structures in one film. Leveraging this characteristic, we customized multi-level optical patterns in the film through multiple exposures. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 21, consecutive exposures using a stripe mask were employed to create a grid-like PC pattern. It was even feasible to construct composite PC patterns on both sides of the film by sequentially applying photomasks and UV irradiation to each side. Figure 4d displayed the “SJTU” on the front and the “butterfly” on the back, observed at different angles. The construction strategy of PC structure introduced a foundation for multidimensional, multi-angle, and multi-level optical patterns, with promising applications in anti-counterfeiting, holographic imaging, augmented reality, and related fields.

a Different color patterns under UV control. Scale bars: 0.25 cm. b Schematic diagram of selectively reflected light from incomplete photonic bandgaps produced by particles ordered along the direction of UV illumination. c Constructing particle columns with two angles on the same side of the film to produce complementary structural color patterns. Scale bar: 1 cm. d Constructing particle columns with two angles on each of the two sides of the film and observing two different structural color patterns at different angles on one side of the film. Scale bar: 1 cm.

Construction and application of PC-type grating structures

The diffraction grating is an optical element that disperses light through multi-slit diffraction and consists of a plane with numerous parallel, equally spaced, and uniformly wide slits60. Motivated by the simple and robust characteristics of this strategy, we attempted to use photomasks with a higher resolution to explore the possibility of a self-adaptive growth technique for fabricating grating structures inside the film. As shown in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 22, the arrays of PC particle columns with 5 μm spacing were consistently observed in the film cross-section as well as X-Y plane following either vertical or oblique irradiation (stripe photomask spacing: 5 μm). The laser scattering patterns were consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3f,g, demonstrating the stability of the PC-type grating structure. Additionally, by utilizing different masks and patterns, a variety of customized grating structures were successfully fabricated, including stripe, dot-matrix, and circular patterns, which demonstrated excellent consistency with the mask patterns (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 23). The resulting grating structures split transmitted light into dual virtual images, suggesting their potential for directional imaging applications (Supplementary Fig. 24). The above experimental results demonstrate that adaptive growth of PC structures combined with mask-assisted patterning constitutes an effective and stable strategy for fabricating grating devices. Further, complexed PC grating structures could even be constructed on both sides of the film by sequentially applying photomasks and UV irradiation to each side. The cross-sectional ‘sandwich’ structure confirmed that the PC gratings on opposite sides of the film do not interfere with each other (Supplementary Fig. 25). Notably, constructing this PC-type grating as a secondary structure, complementing the primary PC particle column arrangement, introduced a coloring mechanism to the film (Fig. 5c). When white light was obliquely incident on the film’s surface with vertically aligned PC particle columns, the regions containing these columns predominantly exhibited disordered scattering and reflection. Conversely, regions of the pattern without particle columns emitted diffracted light due to compliance with Bragg’s law, producing vivid rainbow-like colors. In Supplementary Fig. 26, the left region of the film subjected to direct UV irradiation retained the intact PC particle column structure. In contrast, the right region, shielded by a 5 μm stripe photomask, formed a PC-type grating structure. Under 60° oblique incident light and viewed vertically, the intact PC particle column region on the left exhibited no rainbow colors, whereas the right region displayed vibrant colors, underscoring the critical role of the secondary PC-type grating structure. By superimposing a photomask with a macro-patterned design over a grating mask (Fig. 5d), the exposure area of the sample can be selectively controlled to produce a wide range of predictable PC-type grating patterns such as “SJ,” “pentacle,” and other intricate designs with vibrant structural colors (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Movie 4), while at the same time increasing the utilization of the photomask without the need for a separate custom grating-type photomask. In addition, diffraction and interference of the incident light through the PC-type grating structure produce angle-dependent transmitted colors (Supplementary Movie 5). As shown in Fig. 5f, when the film was tilted at 15° (θS), the transmission peak appeared at 485 nm, corresponding to a blue-green hue. Increasing the tilt angle to 30° caused a redshift in the transmission peak to longer wavelengths, resulting in a red appearance.

a Optical micrographs of sections of vertical PC grating samples (top) and tilted PC grating samples (bottom). Left scale bars:10 μm, right scale bars: 50 μm. b Optical photographs of a 10 μm bar PC grating, a 3 μm bar PC grating, a 10 μm dot PC grating, and a 5 μm ring PC grating. Pictures share the same scale bar: 10 μm. c Schematic diagram of the structural color principle of the PC grating. θi represents the angle of the incident light. d represents the spacing between the PC gratings. d Patterns with different structural colors are created by superimposing a macro photomask with a grating pattern photomask. e Photographs of PC gratings with different color patterns. Pictures share the same scale bar: 1 cm. f Transmission spectra of the sample with vertical PC grating at different angles and optical photographs of the corresponding structural color changes. θs represents the rotation angle of the film. g Scrambling and recovering PC grating-type 2D code pattern by shape memory effect. Scale bars: 1 cm.

Leveraging the vivid structural colors of the PC-based grating architecture, we engineered a synergistic integration with the material’s shape memory effect to unlock multifunctional applications. The PFSA exhibited excellent shape memory capabilities61, and was not affected by the PC structure generated after UV light exposure (Supplementary Fig. 27a,b). In addition, the fracture strength of the film increased slightly after exposure, which was attributed to the reinforcement of nanoparticles inside the film (Supplementary Fig. 27d). This dual functionality—shape memory and mechanical resilience—enabled controlled structural reconfiguration, as evidenced by the morphological transition of PC columns from circular to spindle-shaped geometries under tensile stress without structural degradation (Supplementary Fig. 27e,f). As shown in Fig. 5g, the PC-type grating QR code written into the film was readable by a mobile phone. The shape memory effect was then employed to stretch and fix the film, disrupting its ability to display the information. However, after the shape was restored, the information became readable again without compromising the structural color. Furthermore, harnessing the dual shape memory effect allowed multilevel structural control synchronized with 3D shape morphing (Supplementary Fig. 27c,g). Overall, the combination of the self-adaptive growth mechanism and the shape memory effect gives grating structures design flexibility, simplicity, and controllability, and represents an alternative in grating fabrication technology.

Discussion

In summary, we establish a pioneering light-driven strategy for on-demand fabrication of reconfigurable PCs in PFSA ionomer films and demonstrate a bidirectional interaction between structural evolution and optical feedback. Through anthracene photodimerization under UV irradiation, the nanoparticles grown within the polymer matrix undergo directional self-assembly along the optical pathway to form vertical or tilted PC columns with programmable geometries that possess self-adaptive properties. Here, light not only initiates phase separation but also directs structural alignment through real-time modulation of nanoparticle aggregation. Most importantly, the evolving PC architecture dynamically alters light propagation, creating a feedback loop that improves subsequent growth patterns, a feature absents in traditional static PCs. This bidirectional interaction facilitates the fabrication of angle-specific structural colors and functional PC-based gratings. Notably, the material’s inherent shape memory properties guarantee mechanical robustness and optical recoverability. This study establishes a foundational framework for adaptive photonic systems with broad implications for reconfigurable optics and responsive material design.

Methods

Materials

The PFSA polymers (Mn=335000) were provided by Dongyue Shenzhou New Materials Co. Ltd. (Shandong, China). Trimethylamine (2 mol/L in THF), N,N-Dimethylaminobutane, N,N-Dimethyloctylamine and 9-Chloromethylanthracene were purchased by Adamas-Beta Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Other chemicals mentioned in this paper were obtained from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of anthracene-containing ammonium salts (An-Am-1)

The An-Am was synthesized using the one-step method outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1. 20 mmol Trimethylamine (10 mL of Trimethylamine-containing THF solution) and 10 mmol 9-chloromethylanthracene (2.27 g) were dissolved in acetone solvent (50 mL) in a round bottom flask. The solution was stirred and refluxed under nitrogen protection for 5 h. After the reaction was completed, the purified product was obtained by several filtration and washing processes using ether and dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The structure of An-Am-1 were confirmed by 1H NMR spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Synthesis of anthracene-containing ammonium salts (An-Am-2)

20 mmol N,N-Dimethylaminobutane (2.02 g) and 10 mmol 9-chloromethylanthracene (2.27 g) were dissolved in acetone solvent (50 mL) in a round bottom flask. The solution was stirred and refluxed under nitrogen protection for 5 h. After the reaction was completed, the purified product was obtained by several filtration and washing processes using ether and dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The structure of An-Am-2 were confirmed by 1H NMR spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Synthesis of anthracene-containing ammonium salts (An-Am-3)

20 mmol N,N-Dimethyloctylamine (3.15 g) and 10 mmol 9-chloromethylanthracene (2.27 g) were dissolved in acetone solvent (50 mL) in a round bottom flask. The solution was stirred and refluxed under nitrogen protection for 5 h. After the reaction was completed, the purified product was obtained by several filtration and washing processes using ether and dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The structure of An-Am-3 were confirmed by 1H NMR spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

The preparation of self-adaptive growth PC film

0.5 g PFSA polymers were dispersed in a mixed solvent of 1 mL DMF and 1 mL anhydrous ethanol at room temperature. After dissolving the required An-Am, with another addition of 0.5 mL deionized water, the mixture was poured into a glass mold and dried thoroughly to obtain a yellowish transparent film named PFSA-An. The film was placed on a heating table at 80 °C and covered with the custom photomask. The programmed films were obtained by controlling the irradiation angle and time of the UV lamp, which were cut into customized shapes for tests.

Characterizations

1H NMR spectra were acquired using a 500 MHz ADVANCE NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard, and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as the solvent at room temperature. FT-IR spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer (U.K.) with a diamond ATR probe. Phase separation of ~1 μm thick films spin-coated on silicon wafers were observed using tapping-mode atomic force microscope (AFM) (Multimode 8, Bruker, Germany). UV absorption spectra were measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (TU-1901, Perkin-Elmer, China). The elemental composition of the particles was examined using transmission electron microscopy (Talos F200X G2, ThermoFisher, USA). UV-vis reflectance spectra were obtained using a UV-vis NIR spectrophotometer (Lamda 950, China). XRD analysis was performed using a multifunctional X-ray diffractometer (D8 ADVANCE Da Vinci, Bruker, Germany). SAXS data was recorded using small-angle X-ray scattering (Xeuss 2.0, Xenocs, France). SEM images were captured using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Apreo 2S, FEI, USA) with gold-coated films. Optical micrographs were taken using a super depth 3D microscope (VHX-7000, Keyence, Japan). The 3D images were acquired using a high-resolution laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica STELLARIS 5, Germany) with an excitation wavelength of 405 nm, by performing layer-by-layer scanning and subsequent reconstruction of the internal structure of the film. Refractive index data were acquired using an ellipsometer (V-VASE, J.A. Woollam, USA) with the film thickness of 10 μm. Fluorescence intensity was measured using an advanced fluorescence steady-state transient measurement system (QM/TM/IM, PTI, USA). To ensure consistency in the experimental procedure, the films were irradiated with UV light under heating conditions at 80 °C before fluorescence testing. Shape memory curves were recorded using a dynamic thermo-mechanical analyzer (DMA 850, TA, USA). The mechanical properties were evaluated using an electronic material testing machine (Instron 3365, Instron, USA). The wavelength of the UV light is 365 nm, and the irradiation intensity is 60 mW·cm-2. The collimation characteristics of the UV light source allow for controlled irradiation at a tilt angle simply by tilting the lamp head.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are available with the manuscript. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Frisk Kockum, A., Miranowicz, A., De Liberato, S., Savasta, S. & Nori, F. Ultrastrong coupling between light and matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 19–40 (2019).

Guan, L. et al. Light and matter co-confined multi-photon lithography. Nat. Commun. 15, 2387 (2024).

Lininger, A. et al. Chirality in light–matter interaction. Adv. Mater. 35, 2107325 (2022).

Ayuso, D. et al. Synthetic chiral light for efficient control of chiral light–matter interaction. Nat. Photonics 13, 866–871 (2019).

González-Tudela, A., Reiserer, A., García-Ripoll, J. & García-Vidal, F. Light–matter interactions in quantum nanophotonic devices. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 166–179 (2024).

Rajabali, S. et al. Polaritonic nonlocality in light–matter interaction. Nat. Photonics 15, 690–695 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Field-resolved space–time characterization of few-cycle structured light pulses. Optica 11, 846–851 (2024).

Lin, Q. et al. Direct space–time manipulation mechanism for spatio-temporal coupling of ultrafast light field. Nat. Commun. 15, 2416 (2024).

Choi, I. et al. Laser-induced phase separation of silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 7, 13562 (2016).

Bobrin, V. et al. Nano- to macro-scale control of 3D printed materials via polymerization induced microphase separation. Nat. Commun. 13, 3577 (2022).

Li, Y., Zhou, H., Yang, H. & Xu, K. Laser-induced highly stable conductive hydrogels for robust bioelectronics. Nano-micro Lett. 17, 57 (2024).

Peng, S. et al. Kinetics and mechanism of light-induced phase separation in a mixed-halide perovskite. Matter 6, 2052–2065 (2023).

Hong, B. et al. Photoinduced Skeletal Rearrangements Reveal Radical-Mediated Synthesis of Terpenoids. Chem 5, 1671–1681 (2019).

Huang, J. et al. Accessing chiral sulfones bearing quaternary carbon stereocenters via photoinduced radical sulfur dioxide insertion and Truce–Smiles rearrangement. Nat. Commun. 13, 7081 (2022).

Rodrigues, L. et al. A self-catalyzed visible light driven thiol ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7292–7297 (2021).

Pflug, T. et al. Laser-induced positional and chemical lattice reordering generating ferromagnetism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2311951 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Ratnikov, M., Spraggon, G. & Alper, P. Photoinduced rearrangement of dienones and santonin rerouted by amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 904–908 (2017).

Deka, B. et al. Fabrication of the piezoresistive sensor using the continuous laser-induced nanostructure growth for structural health monitoring. Carbon 152, 376–387 (2019).

Lin, K. et al. Light-induced nanowetting: erasable and rewritable polymer nanoarrays via solid-to-liquid transitions. Nano Lett. 20, 5853–5859 (2020).

Sakakura, M., Lei, Y., Wang, L., Yu, Y. & Kazansky, P. Ultralow-loss geometric phase and polarization shaping by ultrafast laser writing in silica glass. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 15 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. Multi-dimensional shingled optical recording by nanostructuring in glass. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2306870 (2023).

Lin, I. et al. Electro-responsive surfaces with controllable wrinkling patterns for switchable light reflection–diffusion–grating devices. Mater. Today 41, 51–61 (2020).

Guo, Q., Li, Y., Liu, Q., Li, Y. & Song, D. Janus Photonic microspheres with bridged lamellar structures via droplet-confined block copolymer co-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202113759 (2021).

Taylor, J., Argyropoulos, C. & Morin, S. Soft surfaces for the reversible control of thin-film microstructure and optical reflectance. Adv. Mater. 28, 2595–2600 (2016).

Mondal, P. et al. Photospintronics: magnetic field-controlled photoemission and light-controlled spin transport in hybrid chiral oligopeptide-nanoparticle structures. Nano Lett. 16, 2806–2811 (2016).

Diedenhofen, S. ilkeL. et al. Controlling the directional emission of light by periodic arrays of heterostructured semiconductor nanowires. ACS Nano 5, 5830–5837 (2011).

Han, X. et al. Orientation-dependent photoion emission from aerosolized nanostructures. Adv. Optical. Mater. 11, 2201260 (2022).

He, C., Antonello, J. & Booth, M. Vectorial adaptive optics. eLight 3, 23 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Intensity adaptive optics. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 128 (2025).

Salter, P. & Booth, M. Adaptive optics in laser processing. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 110 (2019).

Ning, J. et al. Low energy switching of phase change materials using a 2D thermal boundary layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 41225–41234 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Light reconfigurable topological optical phase structure enabled by a photoresponsive chiral system. Adv. Optical. Mater. 11, 2202529 (2023).

Cai, X., Zhou, Z. & Tao, T. Photoinduced tunable and reconfigurable electronic and photonic devices using a silk-based diffractive optics platform. Adv. Sci. 7, 2000475 (2020).

Xie, Z. et al. Realizing photoswitchable mechanoluminescence in organic crystals based on photochromism. Adv. Mater. 35, 2212273 (2023).

Liang, S. et al. Photocontrolled reversible solid-fluid transitions of azopolymer nanocomposites for intelligent nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 36, 2408159 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Multicolor photonic pigments for rotation-asymmetric mechanochromic devices. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107398 (2021).

Hou, Y. et al. Photonic crystal-integrated optoelectronic devices with naked-eye visualization and digital readout for high-resolution detection of ultratrace analytes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209004 (2022).

Xing, Y., Fei, X. & Ma, J. Ultra-fast fabrication of mechanical-water-responsive color-changing photonic crystals elastomers and 3D complex devices. Small 20, 2405426 (2024).

Sullivan, S. et al. Regulation of plant phototropic growth by NPH3/RPT2-like substrate phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding. Nat. Commun. 12, 6129 (2021).

Li, C. et al. FERONIA is involved in phototropin 1-mediated blue light phototropic growth in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 64, 1901–1915 (2022).

Teyssier, J., Saenko, S., van der Marel, D. & Milinkovitch, M. C. Photonic crystals cause active colour change in chameleons. Nat. Commun. 6, 6368 (2015).

Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani, M. et al. Chameleon-like elastomers with molecularly encoded strain-adaptive stiffening and coloration. Science 359, 1509–1513 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Azobenzene-based macrocyclic arenes: synthesis, crystal structures, and light-controlled molecular encapsulation and release. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5766–5770 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. Photocontrollable elongation actuation of liquid crystal elastomer films with well-defined crease structures. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304378 (2023).

Qin, H. et al. Disorder-assisted real–momentum topological photonic crystal. Nature 639, 602–608 (2025).

Tamara, Ð et al. Entanglement transport and a nanophotonic interface for atoms in optical tweezers. Science 373, 1511–1514 (2021).

Zhu, M. et al. Organelle-like structural evolution of coacervate droplets induced by photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 16, 1783 (2025).

Zou, W., Wang, Z., Qian, Z., Xu, J. & Zhao, N. Digital light processing 3D-printed silica aerogel and as a versatile host framework for high-performance functional nanocomposites. Adv. Sci. 9, 2204906 (2022).

Du, G. et al. Efficient modulation of photonic bandgap and defect modes in all-dielectric photonic crystals by energetic ion beams. Adv. Optical. Mater. 8, 2000426 (2020).

Aeby, S., Aubry, G., Muller, N. & Scheffold, F. Scattering from controlled defects in woodpile photonic crystals. Adv. Optical. Mater. 9, 2001699 (2021).

Jang, J., Jo, Y. & Park, C. NIR light-triggered structural modulation of self-assembled prion protein aggregates. Small 21, 2405354 (2025).

Lin, M. et al. Ultrafast non-radiative dynamics of atomically thin MoSe2. Nat. Commun. 8, 1745 (2017).

Azzolina, G. et al. Out-of-equilibrium lattice response to photo-induced charge-transfer in a MnFe Prussian blue analogue. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 6773–6780 (2021).

Guan, P. et al. High-temperature low-humidity proton exchange membrane with “stream-reservoir” ionic channels for high-power-density fuel cells. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh1386 (2023).

Huang, J., Jiang, Y., Chen, Q., Xie, H. & Zhou, S. Bioinspired thermadapt shape-memory polymer with light-induced reversible fluorescence for rewritable 2D/3D-encoding information carriers. Nat. Commun. 14, 7131 (2023).

Shang, H. et al. Integrating photorewritable fluorescent information in shape-memory organohydrogel toward dual encryption. Adv. Optical Mater. 10, 2200608 (2022).

Cornil, J., Beljonne, D., Calbert, J. & Brédas, J. Interchain interactions in organic π-conjugated materials: impact on electronic structure, optical response, and charge transport. Adv. Mater. 13, 1053–1067 (2001).

Xie, H., Zeng, F. & Wu, S. Ratiometric fluorescent biosensor for hyaluronidase with hyaluronan as both nanoparticle scaffold and substrate for enzymatic reaction. Biomacromolecules 15, 3383–3389 (2014).

Mei, J. et al. Aggregation-induced emission: together we shine, united we soar!. Chem. Rev. 115, 11718–11940 (2015).

Bonod, N. & Neauport, J. Diffraction gratings: from principles to applications in high-intensity lasers. Adv. Opt. Photonics 8, 156–199 (2016).

Xie, T. Tunable polymer multi-shape memory effect. Nature 464, 267–270 (2010).

Acknowledgements

X.J. acknowledges the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52025032, 52103144), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFB4001100). M.X. acknowledges the financial support of the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (24ZR1438600). S. Y. acknowledges the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (523B2026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J. and M.X. supervised this research. S.Z., S.Y., M.X. and X.J. conceived the concept and designed the experiments. S.Z. characterized the materials, performed the measurements and wrote the manuscript. S.Z., S.D., W.Y., R.X., G.W. and M.X. carried out the mechanical analysis. J.L., Z.S., X.J., M.X., F.L. and Y.Z. helped with the manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chris Finlayson, Suli Wu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, S., Li, J., Yan, S. et al. Light-induced self-adaptive growth of photonic crystal structures in perfluorosulfonic acid ionomer films. Nat Commun 16, 11267 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66147-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66147-3