Abstract

Optical anisotropy, a fundamental physical property for polarization control, has long presented a critical consideration in the development of optical materials, particularly in terms of its modulation mechanisms and performance optimization. In the mid- to far-infrared region, simultaneously achieving large birefringence and broad transparency within a single material remains a major challenge. Herein, we report the synthesis of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 (HGSC), a crystalline material featuring linear [Hg3Se2] structural units. HGSC demonstrates a large birefringence of 0.871 at 546 nm, accompanied by the broadest transparency window among Hg-based chalcogenide single crystals (0.4 to 25 µm). Theoretical calculations reveal that the significant birefringence of HGSC originates from the well-aligned linear [Hg3Se2]2- clusters, which exhibit the highest polarizability anisotropy (δ = 430) among all reported birefringence-active functional units. The demonstration of [Hg3Se2]2- clusters as an effective bifunctional unit offers new opportunities for designing infrared photonic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Birefringent materials achieve polarization separation by exploiting the angular difference in total internal reflection between ordinary (o) and extraordinary (e) light, have been widely used as polarization modulators in optical imaging, remote sensing and laser communication systems1,2,3,4,5. Over the past few decades, a variety of birefringent materials have been developed, including commercially available crystals such as YVO4, TiO2, CaCO3, MgF2 and α-BaB2O46,7,8,9,10. However, the intrinsic absorption beyond 5 μm limits their applications in the mid- to far-infrared (IR) regions. In addition, polarization devices requiring high extinction ratios, excellent stability and compact integration demand materials with pronounced optical anisotropy11,12,13,14. Despite these advances, achieving both broad IR transparency and large birefringence within a single material remains challenging, as these properties originate from fundamentally different physical mechanisms15. The IR optical transparency of a material is largely determined by its lattice vibrational characteristics, particularly phonon modes in the mid- to far-IR regions, whereas birefringence originates from anisotropy in its electronic structure and polarizability response16,17,18,19. Consequently, designing structural units that simultaneously suppress phonon-induced absorption and amplify electronic anisotropy represents a promising strategy for high-performance birefringent materials.

To achieve large birefringence, various strategies have been developed, such as introducing planar π-conjugated units20,21, linear units22,23,24,25,26,27,28 or elements containing stereo-electronic lone pairs (As3+, Sb3+, Sn2+)29,30. Mercury (Hg) is a distinctive element whose pronounced relativistic effects lead to significant contraction of the 6s orbital, thereby facilitating electronic rearrangements and enabling the formation of linear multinuclear metal clusters such as Hg22+ and Hg32+. Among these, the linear Hg22+ cluster has been experimentally demonstrated to serve as an effective structural unit capable of significantly enhancing optical anisotropy31,32. Our group revealed that the polarization anisotropy of linear units is markedly superior to that of conventional functional building blocks, with [Hg2I2] exhibiting the highest value among known birefringence-active clusters33. Kong et al. reported linear [Hg2O2] as a birefringence-active structural unit, successfully constructing a layered structure with significant optical anisotropy. This strategy effectively mitigated the mutual cancellation of anisotropic effects, resulting in the compounds Hg4(Te2O5)(SO4) and HgI2HgII(Te2O4)2(HPO4)2 exhibiting notable birefringence of 0.542 and 0.444 at the wavelength of 546 nm, respectively34,35. Our group has revealed that the incorporation of well-aligned linear [Hg2S2]2- clusters significantly enhances the optical anisotropy of the Hg4InS2Cl5 compound, achieving the largest experimental birefringence of 0.35 for Hg-based thiohalides at a wavelength of 546 nm36.

In addition to their ability to form highly anisotropic linear units, Hg-based multinuclear clusters also provide a promising strategy for enhancing IR transparency. As a heavy metal element, Hg forms relatively soft metal-ligand bonds with lower stiffness compared to typical transition metals, resulting in reduced optical phonon energies and consequently suppressing high-frequency IR absorption. To circumvent the near-IR absorption typically associated with oxygenated acid salts, chalcogenides were selected in this study as the preferred anionic framework for structural design. A survey of the ICSD [Version 5.4.0 (build 20250403-0947)] database reveals that, to the best of our knowledge, there are no existing reports on the synthesis or properties of the [Hg3Q2] unit (Q = S or Se). The rational design and synthesis of multinuclear clusters with Hg32+ represents a promising direction for further exploration.

In this paper, a Hg-based thiohalide compound, Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 (HGSC), was successfully synthesized, which contains linear [Hg3Se2] units. Millimeter-sized single crystals were grown using the chemical vapor transport method (CVT). As a structural unit with linear geometry, the [Hg3Se2]2- anionic multinuclear cluster exhibits the highest polarization anisotropy (δ = 430) to date, thereby producing significant birefringence gain. However, birefringence measurements in the IR region typically rely on large, optically homogeneous crystals, which are difficult to obtain at the early stage of material exploration. To address this, we proposed and validated an alternative approach that enables reliable evaluation of birefringence in small-sized crystals. The HGSC crystal demonstrates large birefringence of 0.871 at 546 nm and approximately 0.4 in the mid-IR region. Theoretical calculations indicate that the pronounced optical anisotropy in HGSC originates from the well-aligned linear [Hg3Se2] units. Furthermore, HGSC also demonstrates a broad IR transparency range from 0.4 to 25 µm, which is the widest reported among Hg-based chalcogenide single crystals. Benefiting from its linear coordination and multinuclear cluster configuration, the [Hg3Se2] unit also leads to additional physical behaviors such as reversible thermochromism. This work reveals the structure-property relationship of the linear [Hg3Se2] unit while addressing the intrinsic challenges of birefringence characterization in millimeter-sized crystals in the mid- to far-IR region.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and structure of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 crystal

The crystal structure of HGSC was analyzed and refined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD) data. HGSC crystallizes in the monoclinic space group C2/c (No. 15). In the asymmetric unit, there are five independent crystallographic Hg atoms, two Ga atoms, two Se atoms, and eight Cl atoms (Supplementary Tables 1–5), and the bond valence method was employed to determine the oxidation states of the various metal elements (Supplementary Table 4). The Hg atoms exhibit three distinct oxidation states: Hg0, Hg+, and Hg2+, with a total composition corresponding to Hg02HgI8HgII8Se8(GaCl4)8. The crystal structure of HGSC consists of three distinct linear units that are interconnected through shared Se atoms, forming a pseudo-tridymite-like topology. This topology preserves the open-framework architecture characteristic of tridymite-like structures, while exhibiting more diverse channel morphologies and a framework constructed from linear chain units rather than conventional tetrahedral building blocks (Supplementary Fig. 1). The Hg-Se bond length in [Hg3Se2] is 2.610 Å, which is longer than the average values in [Hg2Se2] (2.558 Å) and [HgSe2] (2.448 Å). This increase in bond length can be attributed to the larger induced dipole moments of the multinuclear clusters [Hg3Se2]2- and [Hg2Se2]2- compared to the [HgSe2] unit. The Hg-Hg-Hg bond angle is 174.57°, consistent with the known bond angle of Hg32+ cluster. Both the [Hg2Se2] and [HgSe2] units adopt geometries that closely resemble those found in previously reported Hg-based thiohalides (Fig. 1a). Through bridging Se atoms, [Hg3Se2] and [HgSe2] assemble into one-dimensional helical channels extending along the b-axis (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, vertex-sharing between [Hg2Se2] and [HgSe2] units gives rise to chair-like Hg8Se6 conformations (Fig. 1c). These helical chains and chair-like units alternate in an antiparallel stacking sequence along the c-axis, generating two distinct channels of different sizes. The larger channels are defined by [Hg3Se2], while the smaller ones are enclosed by [Hg2Se2]2- clusters (Fig. 1d). Relatively weak electrostatic interactions within the multinuclear cluster structure stabilize [GaCl4] within the cavities of the framework, and the entire three-dimensional framework is formed through axial rotational symmetry around the central Hg atoms (Fig. 1e). The coordination geometry around Ga atoms is nearly ideal tetrahedral, as indicated by Cl-Ga-Cl angles of 104.7° to 114.2° and Ga-Cl bond lengths consistent with those previously reported. Furthermore, owing to its complex structure, the information complexity parameters, including information content (IG), total information content (IG, total), maximum structural information content (IG, max), and information density (ρinf.), are 5.569 bits/atom, 6014.520 bits/unit-cell, 7.044 bits/atom, and 1.678 bits/Å3, respectively37. The information complexity of HGSC is greater than that of most inorganic chalcogenides and may give rise to interesting optical, electrical, and thermal properties.

a Coordination environment of Hg atoms in HGSC. b A one-dimensional helical channel along the b-axis. c A chair-like conformation of Hg8Se6 along the b-axis. d Alternating antiparallel stacking of helical channels and chair-like conformations along the c-axis. e Crystal structure of HGSC viewed along the b-axis.

High-purity HGSC polycrystalline powder samples were synthesized via a stoichiometric solid-state reaction method. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern of the sample matches well with the theoretical one (Supplementary Fig. 2). Single crystals of HGSC were grown using the chemical vapor transport (CVT) method in sealed quartz tubes at 950 °C. Figure 2a presents a schematic representation of crystal growth via CVT. During the growth process, Hg2Cl2 served dual functions as both the transport agent and reagent. Under high-temperature conditions, Hg(I) species in Hg2Cl2 readily undergo disproportionation into Hg(II) and Hg(0). Meanwhile, the excess Hg source maintains a Hg-rich environment, thereby stabilizing the system and preventing decomposition of the desired phase. Millimeter-sized single crystals were obtained, including the (001) and (010) planes (Supplementary Fig. 3). The chemical composition of the obtained single crystals was verified by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), which confirms the presence of Hg, Ga, Se, and Cl (Supplementary Fig. 4). Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) quantitative analysis confirms the molar ratio of Hg: Ga: Se as 18.19: 7.82: 8.27 (Supplementary Table 6), consistent with the results from single-crystal refinement. To further investigate the effect of this chemical composition on the stability of HGSC crystals, experimental studies were conducted. Under atmospheric conditions (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C, relative humidity: 20 ± 5%), HGSC crystals were able to maintain a stable state for three days, after which significant hygroscopic degradation occurred.

a Schematic illustration of the single-crystal growth process via CVT. b UV-Vis-NIR diffuse-reflectance spectrum; the inset shows the optical bandgap estimated from the Kubelka–Munk function. c Transmittance spectrum. d XPS spectrum. e Thermochromic behavior observed upon cooling from 300 K to 77 K. f Temperature-dependent evolution of lattice parameters a, b, and c for HGSC single crystals. g Comparison between experimental and calculated Raman spectrum (λ = 633 nm, T = 298 K); the inset shows an optical micrograph of the HGSC crystal. h Temperature-dependent Raman spectra measured from 83 K to 423 K.

Optical Properties and Valence States of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 Crystal

The optical bandgap of HGSC was determined to be 2.559 eV using UV-Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of polycrystalline powder (Fig. 2b). A steep absorption edge at 423 nm further indicates efficient light absorption in the UV region. The photovoltaic conversion ability of HGSC crystals was evaluated. Two copper wires (diameter: 50 μm) were symmetrically fixed on the surface of the HGSC single crystal using highly conductive silver paste to construct a dual-electrode measurement configuration. The sample was illuminated by a monochromatic light source of 350 nm (incident power density: 7 mW/cm2), and the photocurrent-time (I-t) response was recorded using a high-precision digital source meter (model: Keithley 2450, Supplementary Fig. 5). This result suggests that HGSC crystals can effectively generate, separate, and transport photogenerated carriers under UV irradiation, thus providing experimental evidence for their potential application in UV photodetection.

The transmission spectrum of (001)-plane HGSC single crystals reveals an IR transparency extending up to 25 μm (Fig. 2c), covering a broad spectral range that includes the critical atmospheric windows at 3–5 μm and 8–14 μm. This wide IR transparency originates from the electronic configuration and bonding characteristics of the material. First, the fully filled 5 d orbitals of Hg effectively prevent d-d electronic transitions, thereby avoiding absorption in the visible regions38. Second, the valence states of Hg in the [Hg3Se2] and [Hg2Se2] units, typically assigned as 0 or +1, introduce a high proportion of heavy atoms into the lattice, which effectively suppresses multiphonon absorption in the near-IR region. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to verify the presence of multiple valence states of Hg in HGSC. The high-resolution spectra revealed six different components, located at 105.3, 104.8, and 103.8 eV for the Hg 4f5/2 levels, and at 101.2, 100.7, and 99.7 eV for the Hg 4f7/2 levels. These peaks correspond to the oxidation states of Hg0, Hg+, and Hg2+ (Fig. 2d)39,40,41. Furthermore, the wide-range elemental composition of the sample was determined through XPS survey scans (Supplementary Fig. 6). The photoluminescent (PL) propertys of HGSC was further investigated under excitation wavelengths ranging from 300 to 485 nm. The PL spectra recorded at room temperature (298 K) exhibited a prominent emission peak at ~332 nm and a broad green emission band centered at 501 nm (Supplementary Fig. 7). This band spans nearly the entire visible spectrum, highlighting its significant potential for applications in spectral lighting and advanced optoelectronic devices42.

Thermochromic properties of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 crystal

In addition to its unusual valence states, the HGSC compound exhibits reversible thermochromic behavior (Fig. 2e). Upon cooling from 300 K to 77 K, the crystal undergoes a reversible color change from pale-yellow to colorless, which remanied stable over more than 100 thermal cycles (Supplementary Fig. 8), demonstrating the robustness and repeatability of the thermochromic behavior. To explore the origin of this behavior, temperature-dependent single-crystal XRD measurements were conducted from 80 K to 300 K in 15 K increments (Fig. 2f). The results confirm that HGSC retains its crystallographic symmetry throughout this temperature range without undergoing any structural phase transition (Supplementary Tables 7–11). Furthermore, the lattice constants display continuous and anisotropic thermal expansion (αa = 3.177 × 10−5, αb = 2.383 × 10−5, αc = 1.955 × 10−5), suggesting enhanced atomic vibrational amplitudes along specific crystallographic directions due to the ordered alignment of linear building units within the crystal lattice. Among the various mechanisms potentially contributing to thermochromic behavior, phonon dynamics, particularly phonon anharmonicity, can induce band structure renormalization and thereby modulating the material’s optical properties. This occurs as thermally activated lattice vibrations perturb the electronic states, especially near the conduction and valence band edges, resulting in band edge shifts and spectral broadening43. This mechanism is especially relevant in compounds containing heavy metal elements, where the intricate phonon spectrum and strong mass contrast often give rise to enhanced lattice anharmonicity. In electron-phonon coupling, only vibrational modes that induce changes in transition polarizability contribute significantly to the optical response, and these modes can be identified via Raman spectroscopy44. Since HGSC crystals belong to the C2h point group symmetry, the irreducible representations of their phonon modes are given in Eq. (1).

Among these, the Ag and Bg vibrational modes are Raman-active. In HGSC crystals, nine distinct Raman peaks were observed (Fig. 2g). Based on the simulated vibrational eigenmodes, the Ag peaks at 137.10 cm−1 and 215.89 cm−1 correspond to lattice motions primarily influenced by the [Hg2Se2] unit, whereas the Ag mode at 110.70 cm−1 involves substantial contributions from the [Hg3Se2] units (Supplementary Fig. 9a). It is important to emphasize that these assignments do not imply localized molecular-like vibrational modes, but instead reflect collective lattice dynamics predominantly governed by the bonding environments within the Hg-based structural units. In situ variable-temperature Raman spectroscopy was performed under 633 nm laser excitation (Fig. 2h) revealing several phonon modes (ωA, ωB, ωC) with pronounced temperature-sensitive frequencies and intensities, in contrast to temperature-invariant modes (ωD, ωE). To isolate the intrinsic anharmonic contributions to phonon frequency shifts, phonon mode calculations at 143 K were conducted for HGSC, thereby eliminating the confounding effects of thermal expansion (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Moreover, phonon mode calculations indicate that the temperature-sensitive modes originate from the cooperative lattice vibrational modes dominated by the Hg32+ and Hg22+ clusters (Supplementary Fig. 10). This directly links the thermochromic effect to dynamic distortions within the Hg multinuclear clusters, suggesting that the reversible thermochromic behavior observed in HGSC arises from an electron-phonon coupling-dominated mechanism, in accordance with previous reports on InSeI43.

Comprehensive birefringence characterization of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32 crystal

To investigate the optical anisotropy of HGSC crystal, detailed observations were conducted using a ZEISS Axio Scope 5 polarizing microscope. Figure 3a presents a schematic diagram of the polarizing microscope setup. When linearly polarized light is incident on the HGSC crystal, its polarization state becomes elliptical polarization due to its birefringence. This birefringence manifests as periodic variations in brightness under cross-polarized conditions as the sample is rotated (Fig. 3b). At a polarization angle of 0°, the crystal reaches an extinction state. As the angle increases, the transmitted light intensity rises, reaching a maximum at 45°; continued rotation of the crystal produces periodic changes in interference colors with a period of 45°. The pale-yellow color of HGSC at room temperature hinders accurate identification of interference fringes. Fortunately, HGSC exhibits pronounced thermochromic properties: as the temperature drops below the critical point (140 K), the crystals become colorless and transparent. This phenomenon effectively eliminates chromatic interference and improves the resolution of interference color fringes. The birefringence of HGSC crystal sample (thickness: 14.030 μm) was characterized at 140 K (Fig. 3c). Using a compensator with both forward and reverse rotations, the optical path difference was measured to be 11756.14 nm at the characteristic wavelength of 546.1 nm (Fig. 3d, e). According to the formula R = Δn × d, the birefringence at 546.1 nm was calculated to be 0.837. The measurement was repeated at 90 K, yielding an increased optical path difference of 12224.52 nm, corresponding to a birefringence of 0.871 (Supplementary Fig. 11). These results indicate that the birefringence of HGSC crystals increases with decreasing temperature.

a Schematic illustration of the optical setup for birefringence measurement using a polarizing microscope. b Polarizing microscopy images of the HGSC crystal under cross-polarized conditions at various rotation angles (0° to 180°, step = 15°). c Microscopic image of the HGSC sample used for measurement, with a thickness of 14 μm. d, e Images captured during positive and negative rotation of the compensator at the characteristic wavelength of 546.1 nm for accurate determination of the optical path difference.

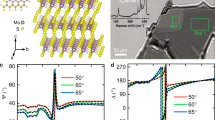

As an IR birefringent material, further characterization of the long-wavelength properties of HGSC is necessary. Nevertheless, such characterization is challenging because newly synthesized crystals are usually limited to millimeter-scale dimensions, which restricts the use of conventional mid-IR birefringence measurements that typically require large and optically homogeneous samples. To address this limitation, we experimentally determined the birefringence of HGSC in the IR region through analysis of the polarization modulation induced by the phase delay between two orthogonal polarization components. In our experiment, b(x)-plane crystals were employed to measure nz-ny (Supplementary Fig. 12). Given that ny and nx are very close (difference of <0.05), the measured nz-ny can be reasonably taken as an approximation of the birefringence nz-nx of the crystal (i.e., Δn = nz-nx ≈ nz-ny). The schematic orientation of the HGSC crystal with respect to the laboratory coordinates is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. Linearly polarized lasers with three typical near-IR wavelengths (1064 nm, 1540 nm, and 3500 nm) were used for the birefringence measurement, enabling a systematic investigation of the polarization evolution during propagation through the as-grown HGSC samples (Fig. 4a). Two HGSC samples with thicknesses of 12.9 μm and 14.0 μm were used for the measurements. The input beam with horizontal polarization was focused and normally incident into the samples. Upon transmission through the crystal, the polarization state of the laser was modulated (Fig. 4b–d), the crystal was functionally equivalent to a retarder. The experimental results reveal that HGSC exhibits large birefringence of 0.517, 0.468, and 0.453 at wavelengths of 1064 nm, 1540 nm, and 3500 nm, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15 and Supplementary Tables 12, 13). A comprehensive survey of reported birefringence values for Hg-based thiohalides and chalcogenides indicates that HGSC ranks among the highest in terms of experimentally measured birefringence (Supplementary Tables 14, 15). These findings verify that HGSC crystal exhibits large and spectrally stable birefringence over a broad IR range, thereby providing critical optical parameters for the design and engineering of polarization-dependent photonic devices.

a Schematic illustration showing the polarization state change of the linearly polarized light propagating through the HGSC crystal. b–d Polarization-dependent intensity of the input light (blue curve) and output light for HGSC crystals with different thicknesses: red for the 12.9 μm sample and yellow for the 14.0 μm sample. Dots represent experimental data, and solid lines denote fitting curves.

The laser damage behavior of HGSC single crystals was investigated using a 1064 nm picosecond-pulse laser. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, no detectable damage was observed in the HGSC crystal when the laser output energy ranged from 0.4 to 2.4 mJ. However, when the energy is increased to 2.8 mJ, microcracks begin to appear at the edges of the crystal. Further increasing the energy to 4.0 mJ results in noticeable cracks within the crystal. Experimental results based on picosecond laser irradiation indicate that HGSC crystals exhibit excellent resistance to laser damage, exceeding that of AgGaS2 by a factor of 3.5.

First-principles investigation of electronic structure and birefringence of Hg18Ga8Se8Cl32

To elucidate the structural-property relationship of HGSC, the electronic structure was investigated through first-principles calculations. As shown in Fig. 5a, the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) of HGSC are located at different high-symmetry points, indicating that HGSC is an indirect bandgap semiconductor. Owing to the well-known underestimation of bandgaps in Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations caused by exchange-correlation energy discontinuities, the calculated bandgap is 2.110 eV, which is lower than the experimental value of 2.559 eV. Figure 5b illustrates the total density of states (TDOS) and partial density of states (PDOS) of HGSC. The Hg 5d orbitals are primarily localized in the energy range of −8 and −6 eV, whereas the valence band region near the Fermi level (−5 to 0 eV) is predominantly occupied by Hg 6s/ 6p, Ga 4p, Se 4p, and Cl 3p orbitals. The conduction band region, spanning from the Fermi energy level to 4.0 eV, is mainly occupied by Hg 6 s/6p and Se 4s/4p orbitals, with a minor contribution from Cl 3s orbitals. Therefore, the optical properties of HGSC are primarily determined by the Hg 6s/6p, Se 4p, and Cl 3p orbitals. Based on the formula ε(ω) = ɛ1(ω) + iε2(ω) and n2(ω) = ε(ω), the calculated birefringence is 0.808 at 546 nm and 0.443 at 1064 nm (Fig. 5c). Given that birefringence depends on both the intrinsic properties and spatial arrangement of functional units45, the vertically aligned linear clusters in HGSC effectively reduce the cancellation of anisotropic polarizability, resulting in enhanced birefringence. To better elucidate the origin of birefringence, the real-space atom-cutting method was employed to quantitatively assess the contributions of individual linear building units to the optical anisotropy. As depicted in Fig. 5d, the contribution of [Hg2Se2] unit to birefringence is approximately 23.8 %, while the contribution of the [Hg3Se2] unit is about 65.9 %. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 17, the direction of the largest refractive index in the HGSC crystal aligns with the orientation of the linear [Hg3Se2] units, confirming that the significant optical anisotropy arises from their highly oriented arrangement. At the microscopic level, the polarization anisotropy of all linear units in the Hg-based chalcogenides was calculated using Gaussian 0946. To make a more comprehensive comparison, several representative linear birefringence-active units were also evaluated (Fig. 5e). Among them, the [Hg3Se2] unit exhibits the highest polarization anisotropy (δ = 430) to date. Moreover, the Electronic Localization Function (ELF) of HGSC was visualized through first-principles calculations (Supplementary Fig. 18). In linearly coordinated units, the charge distribution around atoms is highly asymmetric, and the distortion of the electron clouds enhances electron localization, thereby amplifying electron displacement polarization. As a result, the [Hg3Se2]2- cluster emerges as one of the most promising functional units for achieving large birefringence.

To fully elucidate the potential of HGSC as a birefringent material in the IR region, we compared the transparency ranges of previously reported Hg-based chalcogenide single crystals (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Table 16). HGSC exhibits a broad transparency range covering the atmospheric windows in the mid- to far-IR, representing the widest range reported among all Hg-based chalcogenide single crystals to date. In addition, Fig. 6b compares the birefringence of HGSC with that of representative commercial materials and state-of-the-art birefringent crystals reported in the literature. HGSC exhibits large birefringence (0.453@3.5 μm), nearly twice that of TiO2 (0.236@3.5 μm), positioning it at the forefront of IR birefringent materials. These findings highlight the potential of HGSC for advanced optical applications in the IR region.

a The comparison of birefringence and transmission range of Hg-based chalcogenide single crystals (dark blue: high optical transparency regions; light blue: transparent regions with significant optical absorption). b Comparison of the birefringence of HGSC with those of representative commercial birefringent crystals and recently reported state-of-the-art materials, the yellow-shaded region denotes the mid-IR spectral range6,8,9,34,54,55,56,57,58.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully synthesized a Hg-based thiohalide HGSC, featuring a pseudo-tridymite-like topological structure that incorporates linear [Hg3Se2] units. This structural feature endows HGSC with excellent optical properties, including large birefringence of 0.871 at 546 nm and broad IR transparency window ranging from 0.4 to 25 μm. Theoretical calculations reveal that the pronounced birefringence of HGSC originates from the well-aligned linear [Hg3Se2] units. The [Hg3Se2] unit exhibits the highest polarization anisotropy among all known birefringence-active units to date. Beyond establishing the structure-property relationship of [Hg3Se2] units, our work also demonstrates effective strategies for reliable optical characterization of small crystals, which will be broadly applicable to emerging birefringent materials. These findings not only deepen the understanding of structure-property relationships in birefringent materials but also provide a valuable design strategy for mid- to far-IR photonic applications.

Methods

Synthesis and crystal growth

The reagents including Hg2Cl2 (Aldrich, 99.9%), HgCl2 (Aexchem, 99.99%), HgSe (Aldrich, 99.99%), Ga2Se3 (Aldrich, 99.999%) are analytical grade and obtained from commercial sources without further purification. (Notice: Due to the toxicity of Hg2Cl2, HgCl2, and HgSe, all handling processes should be conducted in a glove box to ensure operational safety.) The millimeter-sized HGSC single crystals were grown using the chemical vapor transport method (CVT). A mixture of HgCl2 (0.1936 g, 3 mmol), Hg2Cl2 (0.5610 g, 5 mmol), HgSe (0.0664 g, 1 mmol), and Ga2Se3 (0.1789 g, 2 mmol) was prepared. A Hg-rich environment was created within a sealed tube by employing an excess of Hg2Cl2. The raw material mixture was placed into a quartz tube, which was sealed under high vacuum (~10−3 Pa) using an oxygen-methane torch. The sealed tube was then transferred to a computer-controlled furnace, and the temperature distribution was as follows: The furnace temperature was gradually increased to 400 °C within 15 h. It was then held at 400 °C for 10 h, followed by an increase to 950 °C within 48 h, and kept at this temperature for 10 days. Subsequently, the temperature was reduced to 300 °C at a rate of 1 °C/h, and finally gradually cooled down to room temperature within 24 h. Through the above process, a pale yellow pseudo-tridymite-like topological structure can be obtained. Hg in Hg2Cl2 is in the +1 oxidation state and readily undergoes disproportionation, rendering Hg2Cl2 a potential reductant and a reservoir of Hg species under CVT conditions. By contrast, Hg in HgCl2 is in the +2 oxidation state, where Hg(II) acts as a soft Lewis acid that preferentially coordinates with selenide, thereby facilitating Hg-Se bond formation. Under high-temperature conditions, Hg(I) undergoes a disproportionation reaction, converting into Hg(II) and Hg(0).

Characterization

High-optical quality crystal (HGSC, 0.091 × 0.068 × 0.092 mm3) was selected under a polarizing microscope and used for single-crystal X-ray data collection. Single-crystal XRD data were collected using a Bruker D8 VENTURE single-crystal X-ray diffractometer with Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at room temperature (298 K) and low temperature (143 K). Data integration, cell refinement, and absorption corrections were performed using the program SADABS47. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined on F2 by full-matrix least-squares techniques using the program suite SHELXTL48. Solutions were checked for missed symmetry using PLATON49. The crystal data yielded Rint = 0.0605, and the structure solution parameters are R1 = 0.0462, wR2 = 0.1114, GOF = 1.095. Powder XRD data were collected with a Bruker D2 PHASER diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation with λ = 1.5418 Å, 2θ = 5 to 70°, scan step width = 0.02°, and counting time = 1 s/step). IR transmittance spectrum was recorded on a Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 Fourier transform IR spectrometer in the range 400–4000 cm−1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of HGSC powder samples was collected on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. Samples were analyzed under high vacuum (pressure <10−9 mbar). Survey scans and high-resolution scans were collected, with binding energies of all scans were corrected according to the C 1 s binding energy at 284.8 eV. The optical diffuse-reflectance spectra of HGSC were recorded at room temperature on a Shimadzu SolidSpec-3700DUV spectrophotometer. The measured wavelength range was 200–2600 nm. To figure out the experimental band gap, the diffuse reflection data were converted into absorption data by the Kubelka-Munk function F(R) = K/S = (1 − R)2/2 R, where R represents the reflection coefficient, K is the absorption value, and S is the scattering coefficient. To verify the presence of Hg32+ and Hg22+, selected HGSC crystals were placed on a glass slide and irradiated with a 633 nm laser. Raman spectra were recorded in the range of 40–1000 cm−1 using an iHR550 Raman spectrometer equipped with a 633 nm He-Ne laser (5 mW), and the temperature during measurements was controlled using a Linkam THMS600 hot-cold stage system. To determine the chemical compositions, the EDS spectra and mappings of the compounds were tested on a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-7610F Plus, Japan) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Oxford, X-Max 50). Under standard testing conditions, the photovoltaic conversion ability of HGSC crystals was evaluated. Two copper wires (diameter: 50 μm) were symmetrically fixed on the surface of the HGSC single crystal using highly conductive silver paste to construct a dual-electrode measurement configuration. The sample was illuminated by a monochromatic light source of 350 nm (incident power density: 7 mW/cm2), and the photocurrent-time (I-t) response was recorded using a high-precision digital source meter (Keithley 2450). The birefringence of HGSC was measured using a polarizing microscope (ZEISS Axio Scope.5 pol) equipped with a Berek compensator under a light source with an average wavelength of 546.1 nm. The interference color during the measurement was classified as first-, second-, or higher-order to ensure measurement accuracy, as their boundary lines were relatively clear compared to subsequent interference colors. Crystals with high optical quality were selected for scanning under the polarizing microscope. The LIDT of HGSC single crystals was measured using a picosecond-pulsed laser (1064 nm, 29 ps). The input laser intensities were raised from 0.4 mJ until damage occurred, and the laser energy was recorded.

Computational methods

The electronic structures, density of states, and birefringence of the title compounds were evaluated using the plane-wave pseudopotential method implemented in the CASTEP software based on DFT50. HGSC was optimized by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional of generalized gradient approximation (GGA)51, while the following orbital electrons were treated as valence electrons: Hg 6s25d10, Ga 4s24p1, Se 4s24p4, and Cl 3s23p5, respectively. The plane-wave cutoff energy for HGSC was set to 800 eV during the calculation, and Monkhorst-Pack k-point meshes (2 × 3 × 1) with a density of less than 0.04 Å−1 in the Brillouin zone were adopted. The default values of the CASTEP code were used for the other calculation parameters and convergence criteria52. A scissor operator correction of 0.449 eV was applied in the Raman spectra calculations; the plane-wave cutoff energy was set to 800 eV; and a (2 × 2 × 1) Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was employed to ensure adequate convergence of the phonon frequencies and electronic structure. To calculate the birefringence, the complex dielectric function, ε(ω) = ε1(ω) + iε2(ω) was computed from the PBE wave functions. The imaginary component of the dielectric function ε2 can be estimated from the electronic structures, and its real part is determined using the Kramers-Kronig transform, which is employed to derive the refractive indices and ultimately obtain the birefringence Δn; the optical properties were scissor-corrected. The anisotropy of the polarizability (Δα) was calculated using the Gaussian 09 revision D.01 program. The GaussView5 software was used to visualize the output file53.

Where αij (i, j = x, y, z) represents an independent element of the polarization tensor.

Data availability

All the characterization data and experimental protocols are provided in this article and its Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for the structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2428275. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ data_request/cif. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kats, M. A. et al. Giant birefringence in optical antenna arrays with widely tailorable optical anisotropy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12364–12368 (2012).

Niu, S. Y. et al. Giant optical anisotropy in a quasi-one-dimensional crystal. Nat. Photonics 12, 392–396 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. A solution-processable natural crystal with giant optical anisotropy for efficient manipulation of light polarization. Nat. Photonics 18, 922–927 (2024).

Mutailipu, M. et al. Achieving the full-wavelength phase-matching for efficient nonlinear optical frequency conversion in C(NH2)3BF4. Nat. Photonics 17, 694–701 (2023).

Wu, Y. B. et al. Periodically poled nonlinear photonic crystal KTa0.51Nb0.49O3 combining wide transparent range and large quadratic coefficient. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201010 (2022).

Luo, H. T., Tkaczyk, T., Dereniak, E. L., Oka, K. & Sampson, R. High birefringence of the yttrium vanadate crystal in the middle wavelength infrared. Opt. Lett. 31, 616–618 (2006).

DeVore, J. R. Refractive indices of rutile and sphalerite. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 41, 416–419 (1951).

Ghosh, G. Dispersion-equation coefficients for the refractive index and birefringence of calcite and quartz crystals. Opt. Commun. 163, 95–102 (1999).

Dodge, M. J. Refractive properties of magnesium fluoride. Appl. Opt. 23, 1980–1985 (1984).

Solntsev, V. P., Tsvetkov, E. G., Gets, V. A. & Antsygin, V. D. Growth of α-BaB2O4 single crystals from melts at various compositions: comparison of optical properties. J. Cryst. Growth 236, 290–296 (2002).

Mei, H. Y. et al. Colossal optical anisotropy from atomic-scale modulations. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303588 (2023).

Mutailipu, M. et al. Strong nonlinearity induced by coaxial alignment of polar chain and dense [BO3] units in CaZn2(BO3)2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202096 (2022).

Shi, G. Q. et al. Finding the next deep-ultraviolet nonlinear optical material: NH4B4O6F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10645–10648 (2017).

Cui, C. et al. Mid-infrared pulsed nanosecond difference frequency generation of oxide LGN crystal up to 5.7 µm. Opt. Lett. 46, 785–788 (2021).

Chen, H., Wei, W. B., Lin, H. & Wu, X. T. Transition-metal-based chalcogenides: a rich source of infrared nonlinear optical materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 448, 214154 (2021).

Foteinopoulou, S., Devarapu, G. C. R., Subramania, G. S., Krishna, S. & Wasserman, D. Phonon-polaritonics: enabling powerful capabilities for infrared photonics. Nanophotonics 8, 2129–2175 (2019).

Zhang, B. B., Shi, G. Q., Yang, Z. H., Zhang, F. F. & Pan, S. L. Fluorooxoborates: beryllium-free deep-ultraviolet nonlinear optical materials without layered growth. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3916–3919 (2017).

Mutailipu, M. et al. Ba3Mg3(BO3)3F3 polymorphs with reversible phase transition and high performances as ultraviolet nonlinear optical materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3089 (2018).

Chen, M. M. et al. AI2Mg3Ga12S22 (AI = K, Rb): T2-type supertetrahedra coupled with [MgS6] octahedra for designing wide-band gap infrared nonlinear optical materials with well-balanced properties. Sci. China Mater. 68, 1030–1037 (2025).

Mutailipu, M. et al. SrB5O7F3: the first asymmetric alkaline-earth fluorooxoborate with unprecedented [B5O9F3]6- functionalized chromophore. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6095–6099 (2018).

Chen, J. D. et al. Honeycomb layered topology construction for exceptional long-wave infrared nonlinear optical crystals. Mater. Horiz. 10, 2876–2882 (2023).

Zhang, M. S. et al. HgBr2: an easily growing wide-spectrum birefringent crystal. Chem. Sci. 15, 6891–6896 (2024).

Huang, C. M. et al. Expanding the chemistry of borates with functional [BO2]− anions. Nat. Commun. 12, 2597 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Growth and temperature-dependent mechanical and thermal properties of one-dimensional chain structure Hg2Br2 crystals for infrared acousto-optic device application. Cryst. Growth Des. 21, 7034–7042 (2021).

Zhang, H. J. et al. Toward strong UV-Vis-NIR second-harmonic generation by dimensionality engineering of zinc thiocyanates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 28329–28338 (2024).

Li, Y. Q. et al. A highly birefringent metal-free crystal assembled by cooperative non-covalent interactions. Mater. Horiz. 11, 4393–4399 (2024).

Yao, A. G. et al. Homoatomic polychalcogenide nonlinear optical anionic groups with ultra-Large optical anisotropy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 16148–16160 (2024).

Song, M., Xiao, Y., Yang, D. Q., Wang, Y. & Zhang, B. B. Polysulfide anions [Sx]2−(x = 2, 3, 4, 5): promising functional building units for infrared nonlinear optical materials. Small 20, 2310423 (2024).

Bu, K. et al. Quantifying structural polarization by continuous regulation of lone-pair electron Expression in molecular crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22469–22475 (2024).

Guo, J. Y., Cheng, S. C., Han, S. J., Yang, Z. H. & Pan, S. L. Sn2B5O9Br as an outstanding bifunctional material with strong second-harmonic generation effect and large birefringence. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2001734 (2021).

Das, A., Das, U. & Das, A. K. Relativistic effects on the chemical bonding properties of the heavier elements and their compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 479, 215000 (2023).

Lei, B. H., Pan, S. L., Yang, Z. H., Cao, C. & Singh, D. J. Second harmonic generation susceptibilities from symmetry adapted Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 187402 (2020).

Tudi, A. et al. Functional modules map of unexplored chemical space: guiding the discovery of giant birefringent materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2409716 (2024).

Li, P. F., Hu, C. L., Li, Y. F., Mao, J. G. & Kong, F. Hg4(Te2O5)(SO4): a giant birefringent sulfate crystal triggered by a highly selective cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7868–7874 (2024).

Li, P. F., Hu, C. L., Mao, J. G. & Kong, F. A giant optically anisotropic phosphate driven by mixed valence mercury units. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401488 (2025).

Ren, Q. X. et al. Hg4InS2Cl5: achieving giant optical anisotropy by introducing well-aligned linear [Hg2S2] units. Adv. Opt. Mater. 13, 2402170 (2025).

Krivovichev, S. V. Which inorganic structures are the most complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 654–661 (2014).

Li, C. et al. Trigonal planar [HgSe3]4- unit: a new kind of basic functional group in IR nonlinear optical materials with large susceptibility and physicochemical stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6135–6138 (2016).

Luo, J. J. et al. Study on the effects of oxygen-containing functional groups on Hg0 adsorption in simulated flue gas by XAFS and XPS analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 376, 21–28 (2019).

Seals, R. D., Alexander, R., Taylor, L. T. & Dillard, J. G. Core electron binding energy study of group IIb-VIIa compounds. Inorg. Chem. 12, 2485–2487 (1973).

Tauson, V. L., Babkin, D. N., Parkhomenko, I. Y. & Men’shikov, V. I. On the mechanism of trace-element uptake during the hydrothermal growth of sulfide mineral crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 49, 149–157 (2004).

Zhang, Y. J. et al. LaMg6Ga6S16: a chemical stable divalent lanthanide chalcogenide. Nat. Commun. 15, 2959 (2024).

Cordova, D. L. M. et al. Sensitive thermochromic behavior of InSeI, a highly anisotropic and tubular 1D van der waals crystal. Adv. Mater. 36, e2312597 (2024).

Hao, H. et al. Anisotropic laser performance in an optically isotropic crystal by phonon engineering. Adv. Photonics Res. 6, 2400149 (2024).

Liu, X., Yang, Y. C., Li, M. Y., Chen, L. & Wu, L. M. Anisotropic structure building unit involving diverse chemical bonds: a new opportunity for high-performance second-order NLO materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 8699–8720 (2023).

Liu, S. Dynamic behavior of chemical reactivity indices in density functional theory: A Bohn-Oppenheimer quantum molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Sci. 117, 477–483 (2005).

Spek, A. L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 7–13 (2003).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT-Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Lin, J. S., Qteish, A., Payne, M. C. & Heine, V. Optimized and transferable nonlocal separable ab initio pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 47, 4174–4180 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Gonze, X. et al. ABINIT: First-principles approach to material and nanosystem properties. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 2582–2615 (2009).

Chen, C. A., Li, Y., Jin, C. C. & Ok, K. M. CsICl2: a record-birefringent inorganic crystal with ultrawide infrared transparency enabled by linear interhalogen ICl2− units. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 26133–26138 (2025).

Li, G. M., Yang, Z. H., Hou, X. L. & Pan, S. L. Chain-like [Sx](x= 2-6) units realizing giant birefringence with transparency in the near-infrared for optoelectronic materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202303711 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. [TeSeS2]2-: the first heterotriple-chalcogenide motifs decode giant mid-far infrared birefringence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 137, e202508555 (2025).

Sinton, W. M. Birefringence of rutile in the infrared. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 51, 1301–1310 (1961).

Chenault, D. B. & Chipman, R. A. Infrared birefringence spectra for cadmium sulfide and cadmium selenide. Appl. Opt. 32, 4223–4227 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China (62305382, 52302011, 22335007, 22361132544), Natural Science Foundation of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2023D01A04, 2022D01B206), Shanghai Cooperation Organization Science and Technology Partnership Program (2023E01001), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024T170994), and the Xinjiang Major Science and Technology Project (2021A01001). Y.W. and C.C. thanks the support from Tianchi Plan of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.R. was responsible for single crystal growth, experimental implementation, auxiliary characterization, and the drafting of the manuscript; C.C. was responsible for the design of optical experiments, experimental data analysis and fitting; X.C. was in charge of LIDT testing; R.A. and Z.Y. handled electronic structure calculations and theoretical simulations of optical properties; Y.W. and S.P. oversaw the design of the research plan and provided overall guidance for the research work. All authors discussed the results and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Boyang Zhao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, Q., Cui, C., Chen, X. et al. [Hg3Se2]2- cluster drives giant optical anisotropy and broad infrared transparency. Nat Commun 17, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66148-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66148-2