Abstract

Acoustic black holes (ABHs) offer broadband wave-manipulation capabilities beyond conventional acoustic metamaterials (AMs) but are fundamentally limited by compromised structural stiffness, high-precision machining requirements and high cut-on frequencies. Here, we break these limitations by adopting a power-law density-tailored composite, ρ-ABH. Analytical derivation, wave-energy analysis, and coupled-system modeling demonstrate that both the cut-on and threshold frequencies of ρ-ABHs are reduced to one-fifth of those in conventional ABHs, enabling operation at deep-subwavelength scales (λ/11). This breakthrough arises from a remarkable wavelength compression and energy density amplification. The inertial-grading-induced amplitude decay also mitigates the fatigue and fracture risks inherent to conventional ABHs. The device experimentally entails efficient wave absorption at ultra-low and -broadband frequencies (25–1200 Hz) and with a 24.5 Hz threshold. Our approach overcomes fundamental frequency-scale constraint in AMs and vibroacoustic engineering, and circumvents manufacturing challenges via controllable material synthesis, offering a pathway for next-generation noise and vibration mitigation technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acoustic metamaterials (AMs)1,2,3,4,5,6 hold transformative potential for manipulating sound and vibration waves, particularly in low-frequency regimes critical for aerospace, transportation, and precision engineering. While locally resonant (LR) AMs achieve subwavelength low-frequency wave control1, their inherently narrow bandwidth necessitates complex multi-unit integration with limited efficacy6,7,8,9. Alternative approaches leveraging nonlinear chaotic or thermoacoustic mechanisms enable ultra-broadband attenuation10,11,12 but suffer from structural intricacy, acute parameter sensitivity, and operational instability. Consequently, realizing efficient, broadband, subwavelength low-frequency wave control remains a fundamental challenge.

Inspired by wave trapping via astrophysical black holes (Fig.1a), acoustic black holes (ABHs) exploit power-law thickness tailoring to trap flexural waves via vanishing phase velocity13,14. Unlike narrowband LR metamaterials, ABHs allow for broadband wave manipulation in lightweight structures through this trapping mechanism, entailing unique phenomena including slow wave effects13,14, wave focusing15,16,17, and enhanced damping18,19,20. These properties underpin applications in vibration control21,22,23, sound radiation suppression24,25, noise insulation26, and energy harvesting27,28,29, etc. Nevertheless, ABH functionality is constrained by the cut-on frequencies requiring structural dimensions comparable to operational wavelengths. Although composite strategies (sandwich structures30, phononic crystal31,32, double-leaf33,34, spiral designs35,36, etc.) have been attempted to improve low-frequency performance, they fail to overcome this causality-governed fundamental scale-frequency bottleneck. Innovative mechanism is required to go beyond the current structural design paradigm.

a Schematical diagram of the black hole in astronomy. The red arrow depicts the trajectory of light that cannot escape the black hole’s event horizon. b Schematical diagram of the proposed ρ-ABH. c The reduced-order model of the ρ-ABH. d–g Dispersion curves of the ρ-ABH: real and imaginary parts of Ki (i = 1, …, 4) are plotted versus the dimensionless wavenumber Kf x0.

In principle, a proper tailoring of the material properties would allow for the manipulation of the wave propagation. As such, functionally graded materials also offer alternative solutions37,38,39,40,41, such as stiffness-tailored37, modulus-graded38 or thickness-modulus-bi-tailored39 designs. However, manufacturing complexities limit their implementation40,41, and crucially, the effects of density tailoring on wave control in the context of ABH–specially in terms of the impact on cut-on frequency reduction, amplitude modulation, damping enhancement, and wave absorption–remain unexplored. Compared with conventional structural/thickness tailoring or modulus/stiffness tailoring, density-tailoring offers a key advantage: alleviating the limitations of conventional thickness/modulus-tailored ABHs, in which the thinnest/softest sections typically undergo vibration with excessive amplitude, thus compromising or even jeopardizing the structural stiffness and leading to problems like structural fatigue, which is detrimental to the durability/integrity of the structures. Meanwhile, the proposed solution offers an alternative to the existing solutions to manipulate wave propagation in ABHs. Furthermore, the material-based density control approach overcomes critical limitations inherent in existing ABH manufacturing—such as high-precision requirements, gradient discontinuities, and complex/meticulous geometric variations—by enabling tunable impedance gradients through compositional adjustment. This strategy not only ensures smoother impedance variation but also expands design flexibility, thereby facilitating practical engineering implementation.

Here, we report a deep-subwavelength ABH metamaterial (ρ-ABH) via power-law density tailoring. Analytical modeling demonstrates that a fourth-order density gradient induces unprecedented wave compression and energy accumulation, redshifting the cut-on frequency to one-fifth that of the conventional thickness-tailored ABHs (h-ABHs) and enabling deep-subwavelength operation at λ/11 (where λ is the incident wavelength). When implemented as a dynamic vibration absorber (ρ-ABH-DVA), this design achieves threshold-exceeding dual-ultra (ultra-low-frequency and ultra-broadband) damping/absorption. Pioneering fabrication and experimental validation confirm these dual ultra-properties. Integrated analytical, wave-energy, and experimental analysis establish that density tailoring–not geometric modification–enables this deep-subwavelength breakthrough, resolving the core frequency-scale trade-off in acoustic metamaterials and conventional vibroacoustic control.

Results

Exact solution, cut-on frequency redshift and size reduction

The proposed ρ-ABH is sketched in Fig. 1b, which is a circular panel with graded material density along the radial direction. To capture the essential physics of wave propagation mainly along the radial direction, we consider a reduced-order model where the panel retreats to a slender beam representation (Fig. 1c). The beam model is strategically adopted as a necessary and foundational step to rigorously derive the analytical model and solutions, as well as to reveal the fundamental wave properties/mechanisms without the obscuring complexities of 2D or more complex structures, aligned with the research paradigm widely adopted in the field10,13,42. The beam of length \({x}_{0}\) features a non-uniform density \(\rho (x)\) along the x-direction:

where \({\rho }_{0}\) is the density when \(x={x}_{0}\). The governing equation for the transverse vibration of the beam, whose thickness is much smaller than the shear wavelength (thus neglecting rotational inertia and transverse shear effects), writes

where \(w(x,t)\) is the transverse displacement; \(D={E}_{0}b{h}_{0}^{3}/12\) and \(A=b{h}_{0}\) the flexural stiffness and cross sectional area, respectively, with \({E}_{0}\),\(b\) and \({h}_{0}\) being the Young’s modulus, the width and the thickness, respectively.

For the stationary harmonic case,

Substituting Eqs. (1) and (3) into Eq. (2) yields

where \({K}_{f}={(12{\rho }_{0}{\omega }^{2}/{E}_{0}{h}_{0}^{2})}^{1/4}\) is the flexural wavenumber at \(x={x}_{0}\).

When \(p=4\), Eq. (4) becomes a Cauchy–Euler equation whose solution can be represented by

where \({K}_{i}=\frac{3}{2}\pm \sqrt{\frac{5}{4}\pm \sqrt{1+\xi }}\), \(\xi={({K}_{f}{x}_{0})}^{4}\) and \({C}_{i}\) are the undetermined coefficients.

The above model and solution demonstrate that in the wavenumber space, the ρ-ABH can be characterized as a wave-propagating medium governed by four distinct wave components \({K}_{i}\). The dispersion curves of the ρ-ABH, including the real and imaginary parts of \({K}_{i}(i=1,{{\mathrm{...4}}})\), are plotted versus the dimensionless wavenumber \({K}_{f}{x}_{0}\) (Fig. 1d−g). For the time convention \({e}^{j\omega t}\), when \({K}_{f}{x}_{0} > 0.866\) or \(\xi > 9/16=0.5625\), the wavenumber \({K}_{1,2}= \frac{3}{2}\pm {{{\rm{i}}}}\sqrt{-\frac{5}{4}+ \sqrt{1+ \xi }}\) take complex values (Fig. 1d, e), representing propagating waves in the negative and positive x directions, respectively; when \({K}_{f}{x}_{0}\le 0.866\) or \(\xi \le 9/16=0.5625\), \({K}_{3,4}=\frac{3}{2}\pm \sqrt{\frac{5}{4}+\sqrt{1+\xi }}\) take real values (Fig. 1f, g), signaling divergent and convergent evanescent waves, respectively. The cut-on frequency of this ρ-ABH is thus obtained when \({K}_{f}{x}_{0}=0.866\) or \(\xi=9/16=0.5625\) as

which, despite the different value of \(\xi\), takes the same form as that of the conventional thickness power-law ABH or h-ABH, whose thickness function satisfies \(h(x)={h}_{0}{(x/{x}_{0})}^{2}\) and shares the same length and width with those of the ρ-ABH. Note that in Eq. (6), \(\xi=9/16\) (\(\sqrt{\xi }=3/4\)) for this ρ-ABH while \(\xi=225/16\) (\(\sqrt{\xi }=15/4\)) for the h-ABH counterpart. This suggests that the cut-on frequency of the ρ-ABH is much lower than and merely one fifth that of the conventional h-ABH43.

To understand the underlying physics for the redshifted cut-on frequency, recall that \(\xi={({K}_{f}{x}_{0})}^{4}\) in the Cauchy–Euler equation and the cut-on frequency formula for both ρ- and h-ABH is a parameter dependent upon frequency, shape and material parameters. Therefore, \(\xi\) is rewritten as

in which \({\lambda }_{f}\) is the wavelength of the incident wave. From above we know that \(\xi\) for the ρ-ABH is much smaller than that for the h-ABH counterpart. Thus, from Eq. (7), for an equivalent ABH length or x0, ρ-ABH exhibits operational efficacy for incident flexural waves of much larger wavelengths. This means ρ-ABH can deal with incident waves of a much lower frequency than its ρ-ABH counterpart, and thus explains why its cut-on frequency is much redshifted compared with its conventional h-ABH counterpart.

Besides, from Eq. (6), one has

which is proportional to \(\root{{4}}\of{\xi }\). Equation (8) demonstrates that for a ρ-ABH to yield the same cut-on frequency as its h-ABH counterpart, the physical size of the former is reduced to 1/\(\sqrt{5}\) of the latter—less than half. This establishes the theoretical foundation for designing and realizing subwavelength acoustic black holes (ABHs) based on the power-law density tailoring.

Boosting wavelength compression, energy density and decaying amplitude

To further illustrate the physics behind redshifted cut-on frequency and the reduced structural dimension, we reformulate Eq. (5) in a wave-form expression considering \({K}_{1,2}=\frac{3}{2}\pm {{{\rm{i}}}}{k}_{1},{K}_{3,4}=\frac{3}{2}\pm {k}_{2},\) and \({k}_{1}=\sqrt{-\frac{5}{4}+\sqrt{1+\xi }},{k}_{2}=\sqrt{\frac{5}{4}+\sqrt{1+\xi }}\) as

where

represent the two propagating waves in the negative and positive directions, respectively, and

represent the two evanescent waves in the two directions, respectively.

To elucidate the spatially varying properties of waves, the left-going waves \({b}^{-}\) is extracted as the wave function which conforms to42

where \({A}_{E}(x)={x}^{3/2}\) and \({\phi }_{E}(x,t)={k}_{1}\,{{\mathrm{ln}}}\,x+\omega t\) are the amplitude and phase functions, respectively. The wave function is plotted against the spatial variable x at four different frequencies (Fig. 2a). One can see a reduced wave amplitude and compressed wavelength as wave propagates at all frequencies. The wave amplitude decays in the form of \({x}^{-3/2}\) as the wave propagates positively (leftward). This amplitude decay feature is completely different from the amplitude amplification of the h-ABH42 in the form of \({x}^{3/2}\) and that of the E-ABH37 in the form of \({x}^{1/2}\), which, in both cases, are most pronounced near the beam tip (thinnest region of h-ABH and the least stiff part of E-ABH), making the structure vulnerable to fatigue damage and fracture risk. By contrast, the wave amplitude attenuation property of the ρ-ABH, due to the increased inertia near x = 0, allows for avoiding these structural drawbacks. For the phase function, although taking the same form as that of the h-ABH, its spatial variation is different from the latter. This is reflected by the wavenumber \({k}_{E}\) for ρ-ABH, derived as the first-order partial derivative of the phase with respect to the spatial variable x:

a Wave functions of the ρ-ABH vary with frequencies and spatial variable x. b Phase functions of the ρ-ABH and h-ABH at different frequencies. c Logarithmic representation of phase field distributions of the ρ-ABH (light shades) and h-ABH (dark shades) at different frequencies. d Ratio of the compressed wavelengths inside the ρ-ABH and h-ABH. e The normalized time-averaged vibrational energy densities for both ABH types for a constant ABH length. x0 = 0.2 m, h0 = 3 mm, ρ0 = 1 g/cm3, E0 = 2 GPa. The arrows in panels (a) and (c) represent the wave propagation direction.

It is evident that the ρ-ABH displays a larger wavenumber \({k}_{E}\) due to its higher k1. Consequently, over the same distance x, the wave phase accumulates more rapidly within the ρ-ABH.

The phase velocity \({c}_{ph}\) of the flexural waves in the ρ-ABH can also be derived according to a constant phase condition44 as

From Eq. (14), while sharing the same form as the conventional h-ABH38, the ρ-ABH exhibits a smaller phase velocity \({c}_{ph}\) due to its higher k1. Thus, over the same distance x, waves in the ρ-ABH propagate slower than those in an h-ABH under the same frequency, shape and material conditions. This results in a stronger slow-wave effect within the ρ-ABH.

The compressed wavelength within the ABH can be derived as44

From Eq. (15), the compressed wavelength is proportional to x but inversely proportional to k1 (\({\lambda }_{E}\propto \frac{x}{{k}_{1}}\)). Thus, for the same ABH type (constant k1), \({\lambda }_{E}\) is the largest at x = x0 and decreases as wave propagates leftward toward x = 0, demonstrating the inherent wave compression capability of both ABH types. Crucially, because k1 is larger in the ρ-ABH than in the h-ABH, the compressed wavelength \({\lambda }_{E}\) is smaller over any given distance (constant x or x0–x). This enhanced wave compression capability enables the ρ-ABH to compress incident waves of longer wavelength (lower frequency) to the same level as the h-ABH does over an equivalent propagation distance (Fig. 2b), where the two waves with two different frequencies in each subfigure share the same compressed wavelength. This mechanism fundamentally explains the downshifted operating frequency and redshifted cut-on frequency observed in the ρ-ABH.

Beyond the mathematical derivations, the superior wavelength compression capability of the ρ-ABH over the h-ABH is illustrated by the cloud maps of phase filed distributions (Fig. 2c). For an incident wave with the same initial phase at x = x0, the number of wave cycles within the ρ-ABH is consistently greater than that in the h-ABH counterpart at all three frequencies shown. This visually confirms that the ρ-ABH exhibits stronger wave compression. It is noteworthy that above the cut-on frequencies of both ABHs, this enhanced wave compression becomes more pronounced as frequency decreases. This can be attributed to the wavelength ratio \({\lambda }_{E,\rho }/{\lambda }_{E,h}\) increasing at lower frequencies (Fig. 2d). Here, \({\lambda }_{E,h}\) and \({\lambda }_{E,\rho }\) represent the compressed wavelengths inside the ρ-ABH and h-ABH, respectively. For further illustration, the vibrational energy density is then derived for the ρ-ABH. The kinetic and potential energy densities (per unit length) are derived as

The total time-averaged vibrational energy density is thus obtained as the summation of the time-averaged kinetic energy density and the time-averaged potential energy density as

Applying \(\rho (x)={\rho }_{0}{({x}_{0}/x)}^{4}\), the total time-averaged vibrational energy density \({\langle E\rangle }_{\rho }\) writes

For h-ABH with the same incident wave or \(w(x,t)={x}^{3/2}\exp ({{{\rm{i}}}}[{k}_{1,h}\,{{\mathrm{ln}}}\,x +({k}_{1,\rho }-{k}_{{\rm{1,h}}}){{\mathrm{ln}}}\,{x}_{0}+\omega t])\), the total time-averaged vibrational energy density \({\langle E\rangle }_{h}\) are similarly derived as

Equations (19) and (20) reveal that the vibrational energy densities in both ABH types are inversely proportional to x, signifying energy accumulation near the tip of the ABHs (x = 0). To compare the vibrational energy densities in different ABH types, the normalized vibrational energy densities or \(\langle \bar{E}\rangle=\langle E\rangle /(\frac{1}{2}b{h}_{0}{\rho }_{0}{x}^{3})\) for both ABH types for a constant ABH length \({x}_{0}\) are demonstrated (Fig. 2e). It is observed that normalized time-averaged vibrational energy density in ρ-ABH \({\langle \bar{E}\rangle }_{\rho }\) is always above that of its conventional h-ABH counterpart \({\langle \bar{E}\rangle }_{h}\) at all frequencies and locations except the boundary. That is, the relationship \(\frac{ < E{ > }_{\rho }}{ < E{ > }_{h}} > > 1\) holds across the ABH domain (except near the boundary). This indicates that for a given ABH length, the total time-averaged vibrational energy density of a ρ-ABH substantially exceeds that of its conventional h-ABH counterpart. This enhanced energy accumulation stems directly from the ρ-ABH’s superior wave compression capability. Consequently, a ρ-ABH of smaller physical dimensions can achieve energy accumulation equivalent to a larger h-ABH, providing the theoretical foundation for designing and realizing deep-subwavelength ABHs.

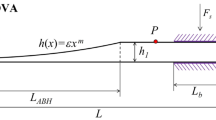

Dual-ultra damping enhancement & wave absorption

In the previous section, a ρ-ABH is designed with its maximal density goes to infinity. In reality, there is always a truncation of the density so that the maximal density takes a finite value, denoted as \({\rho }_{t}\), with the corresponding length of ρ-ABH as \({L}_{ABH}={x}_{0}(1-{({\rho }_{0}/{\rho }_{t})}^{1/p})\). We then use the truncated ρ-ABH as a dynamic vibration absorber (ρ-ABH-DVA) to explore its dynamic, damping enhancement and vibration absorbing characteristics. As shown in Fig. 3a, a ρ-ABH-DVA is attached to a host cantilever beam, forming a combined system. The system is subjected to a transverse harmonic force \(F={F}_{0}\,\sin (\omega t)\) at the free end of the host beam. This ρ-ABH-DVA consists of a connector and a ρ-ABH with p = 4. The latter includes a density power-law section (the color gradient portion in Fig. 3a) with an attached thin viscoelastic damping layer (orange color in Fig. 3a) and a uniform section. The densities, Young’s Moduli and thicknesses of the ABH uniform section and the damping layer are denoted by (\({\rho }_{0}\),\({E}_{0}\),\({h}_{0}\)) and (\({\rho }_{d}\),\({E}_{d}\),\({h}_{d}\)), respectively;\(\,{\eta }_{0}\), η and \({\eta }_{1}\) represent the material loss factor of the ABH uniform section, the damping layer and the host beam, respectively; \(L\), \(H\) and \({l}_{j}\), \({h}_{j}\) denote the length and thickness of the host beam and the connector, respectively; \({l}_{{xj}}\) represents the length of the ABH uniform section. The eigen-frequencies and the driving point mobilities of the combined system are calculated using the reduced multibody system transfer matrix method (RMSTMM, see Methods)45, with the associated topology diagram and derivation process shown in Fig. 3b, c. The calculated first ten eigenfrequencies of the system by RMSTMM and the relative errors compared with those calculated using the COMSOL finite element method (FEM) are shown in Fig. 3d. The calculated mobility of the system, i.e. \({{\mathrm{Mobility}}}=20{\log }_{10}|i\omega Y|/{F}_{0}\), at the driving point is presented in Fig. 3e. It is observed that the eigenfrequencies and mobilites calculated by both the theoretical method or RMSTMM and FEM are in good agreement.

a Schematic diagrams of the combined system. b Topology diagram of the combined system as a planar branched multibody system. c Derivation of the combined system driving-point steady-state response using RMSTMM. d Eigenfrequency validation and relative errors against FEM. e Validation of the driving point mobility against FEM.

Next, based on the validated model and method, we investigate the threshold frequency for damping enhancement by the ρ-ABHs. For the conventional thickness-tailored ABH (h-ABH), a threshold frequency (\(\,{f}_{et-hABH}\)) exists from which the loss factor starts to increase to a high level14. Considering the fact that the length of the h-ABH is one-quarter of the wavelength of the incident flexural wave at \(\,{f}_{et-hABH}\) or18

the threshold frequency \(\,{f}_{et-hABH}\) of the h-ABH could be estimated by

The modal loss factors of different components in the system: conventional h-ABH as a DVA, denoted by h-ABH-DVA, ρ-ABH-DVA, and their respective corresponding combined systems with a host beam are presented (Fig. 4a, b). It is worth noting that although a mass difference exists between the two types of ABH-DVA configurations, key equivalencies have been preserved, mainly in three basic aspects: a) the geometric and material properties of both the host structure and ABH uniform section; b) the dimensional parameters of the ABH graded section, and c) the local phase velocity within the ABH uniform section. As shown in Fig. 4a, the threshold frequency for damping enhancement in the h-ABH-DVA and its combined system is around 17.1 Hz. Based on Eq. (22), the threshold frequency of this ABH is\(\,{f}_{et-hABH}\)\(=25.1\)Hz. Note that the presence of the connectors slightly reduces \({f}_{et}\). From Fig. 4b, the modal loss factor of the ρ-ABH-DVA and that of its corresponding combined system start to increase abruptly from 3.4 Hz, indicating that its threshold frequency \({f}_{et-\rho ABH}\) is ~3.4 Hz, which is only one-fifth of the threshold frequency \({f}_{et-hABH}\) of conventional h-ABH-DVA, i.e.

a Loss factors of conventional h-ABH-DVA, host beam, and their combined system. b Loss factors of ρ-ABH-DVA, host beam, and their combined system. Driving-point mobility of the host beam c without and with the attached h-ABH-DVA, d without and with the attached ρ-ABH-DVA, and e without and with the attached ρ-ABH-DVA of different ABH material loss factors.

From Eqs. (22) and (23), we can estimate the threshold frequency of the ρ-ABH as

The corresponding flexural wave wavelength \({\lambda }_{et-\rho ABH}= 2\pi \root{{4}}\of{{E}_{0}{h}_{0}^{2}/12{\rho }_{0}{(2\pi {f}_{et-\rho ABH})}^{2}}\) at \({f}_{et-\rho ABH}=3.4\)Hz is 1.5088 m, which is \(\sqrt{5}\) times the wavelength of threshold frequency of the h-ABH, i.e.,\({\lambda }_{et-\rho ABH}=\sqrt{5}{\lambda }_{et-hABH}\). Since the lengths of the power-law varying sections for both types of ABH are the same (\({L}_{ABH}=0.1388\) m), this means that a ρ-ABH can control a larger wavelength. And the length of the ρ-ABH approaches one-eleventh of the wavelength of the incident flexural wave at frequency \({f}_{et-\rho ABH}\) as

Equations (23) and (25) demonstrate that the density power-law design achieves a redshift of the threshold frequency and a deep-subwavelength scale. To verify the threshold frequency formula in Eq. (24), the first eigenfrequency of the host beam is set as 3.75 Hz. From the mobility comparison with and without the h-ABH-DVA (Fig. 4c), it is observed that all resonance peaks after \({f}_{et-hABH}\approx 25.1\) Hz are reduced. By contrast, the ρ-ABH-DVA achieves comparable vibration reduction above its much lower threshold frequency \({f}_{et-\rho ABH}\approx 3.4\) Hz (Fig. 4d). These results validate the correctness of the predicted threshold frequency and demonstrate the dual-ultra vibration absorbing performance of the proposed ρ-ABH.

We further investigate the role of material damping in ABH structure itself for vibration suppression, and present the velocity mobility response when the material damping of the density power-law varying section of the ABH is altered, with the loss factors of damping layers fixed at η = 0.6 (Fig. 4e). It is observed that increasing the material loss factor reduces all resonant peaks, albeit to different degrees. This demonstrates that the inherent material damping of the ABH itself can also effectively attenuate resonance peaks and suggests that utilizing high-dissipative materials such as polymers for ABH fabrication can provide additional vibration damping benefits.

Dual-ultra features in 2D ρ-ABH plate

We then extend the study of redshifted threshold frequency and dual-ultra damping enhancement properties from the 1D ρ-ABH beam to a 2D plate and its combined system with a host plate. This section presents a comparative evaluation of the modal loss factors and damping enhancement threshold frequencies between the 2D ρ-ABH and conventional h-ABH plates when used as DVAs on a host plate. The material parameters of the ρ-ABH, the connector and the host structure remain consistent with the 1D case, while the geometrical parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

As shown in Fig. 5a, a circular ρ-ABH plate, acting as a DVA, is attached to a polygonal host plate, forming a combined system. This ρ-ABH-DVA system consists of a connector (identical to the 1D configuration) and a circular ρ-ABH plate with power-law exponent p = 4. The latter includes a density power-law section (indicated by color gradient) attached with a thin viscoelastic damping layer (depicted by the dotted curves) and a uniform section. The eigenfrequencies of the combined system calculated using the COMSOL shell and solid mechanics models are presented (Fig. 5b). It is observed that the eigenfrequencies calculated by both models are in good agreement.

Next, we investigate the modal loss factors and threshold frequencies for damping enhancement of the 2D ρ-ABHs with a thin damping layer acting as a DVA based on the validated COMSOL solid mechanics model. The modal loss factors are presented for different components: conventional h-ABH as a DVA (denoted by h-ABH-DVA), ρ-ABH-DVA, and their respective corresponding combined systems (Fig. 5c, d). Similar to the 1D case, three fundamental equivalences are maintained between the two types of 2D ABH-DVAs: a) the geometric and material properties of both the host plate and ABH uniform section; b) the dimensional parameters of the ABH graded section, and c) the local phase velocity within the ABH uniform section.

From Fig. 5c, the modal loss factors of the h-ABH-DVA and its corresponding combined system start to increase abruptly from 9.44 Hz, suggesting a threshold frequency of 9.44 Hz. Similarly, the modal loss factors of the ρ-ABH-DVA and its corresponding combined system increase abruptly starting from 1.93 Hz (Fig. 5d), suggesting a threshold frequency of 1.93 Hz. This reduction to one-fifth of the threshold frequency is consistent with the 1D beam case, thus confirming the redshifted threshold for damping enhancement in the proposed ρ-ABH-DVA in 2D case and demonstrating its dual-ultra damping enhancement performance.

Fabrication and experimental validation

The ρ-ABH is then fabricated using the principles of composite materials. The raw material for this ABH consists of high-density tungsten particles uniformly dispersed within low-density PU polymer composed of a softer PU rubber and a harder PU resin with mass ratio \({R}_{2}={M}_{{{{\rm{resin}}}}}/{M}_{{{{\rm{rubber}}}}}\). The mass ratio of tungsten to PU is denoted as \({R}_{1}={M}_{tungsten}/{M}_{{{{\rm{PU}}}}}\). The total weights of PU and the composite material are \({M}_{{{{\rm{PU}}}}}={M}_{{{{\rm{resin}}}}}+{M}_{{{{\rm{rubber}}}}}=({R}_{2}+1){M}_{{{{\rm{rubber}}}}}\) and \({M}_{{{{\rm{total}}}}}={M}_{{{{\rm{PU}}}}}+{M}_{tungsten}=({R}_{1}+1){M}_{{{{\boldsymbol{P}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{U}}}}}\). The specimens of each material are shown in Fig. 6a. Since the densities of PU rubber and PU resin are equivalent, the densities of their respective mixtures with the tungsten are identical46. The approach we take to obtain the ρ-ABH material is as follows. Firstly, tungsten particles are mixed with two PU materials separately, both in the ratio of R1, with the mass of tungsten powder and two PUs as \({{M}}_{{{{\rm{resin}}}}}={{M}}_{{{{\rm{rubber}}}}}=0.5{{M}}_{{{{\rm{PU}}}}}={{{0.5}}}{{M}}_{{tungsten}}/{{{{R}}}}_{{{{\bf{1}}}}}\). From this, we can obtain composite material samples with different proportions of \({R}_{1}\). By measuring the mass and volume of each sample, we can derive the mass density corresponding to different values of \({R}_{1}\). The material parameters of each sample are then tested using a Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA). Subsequently, we adjust the ratio \({R}_{2}\) of the PU resin to PU rubber and remix the samples with different \({R}_{2}\) values while keeping \({R}_{1}\) constant. This process ultimately yielded samples possessing different densities but consistent Young’s moduli. In other words, we manipulate the density of the composite material without altering its Young’s modulus. The sample numbering, preparation, and testing are shown in Fig. 6b−f. Detailed preparation procedures are provided in the Supplementary Note 3.

The R1–ρ (R2 = 0.52) curve obtained from the tests is presented in Fig. 7a. After multiple mixing, preparation, and measurement cycles, different density values are stabilized around seven values (Fig. 7a), with a maximum error within 3%. By adjusting \({R}_{2}\), the storage modulus of the samples with different densities are all maintained within 100 ~ 200 MPa, and could all reach around 140 MPa (Fig. 7b−h). Additionally, the loss factors of the samples with different densities are all around 0.4 (see Supplementary Note 3). For the material curing, a step-by-step curing method is adopted to ensure that each material section of the ρ-ABH is effectively cured into a single unit and maintain structural strength (see Supplementary Note 4). Consequently, we obtain the ABH material samples with varying density gradients but constant modulus. Based on composite material principles, this method eliminates the need for micron-level geometric precision required by traditional h-ABHs. It transforms manufacturing from ultra-precision machining to controllable material synthesis—a more scalable and practical approach for engineering applications. The rest of the ABH sample and the combined system parameters are referring to Methods. Based on these parameters, the threshold frequency of the designed ABH is obtained as 24.5 Hz using Eq. (24). The host beam is designed such that its first eigenfrequency (27.2 Hz) is slightly higher than the ABH’s threshold frequency, in order to validate the ABH’s damping performance above the threshold frequency and across the entire frequency range.

a Measured density power-law material R1–ρ curve. b–h Measured R2-E curves for samples with different densities: b ρ = 2000 kg/m3, R1 = 0.95, c ρ = 3000 kg/m3, R1 = 2.11, d ρ = 4000 kg/m3, R1 = 3.41, e ρ = 5000 kg/m3, R1 = 5, f ρ = 5500 kg/m3, R1 = 6.61, g ρ = 6500 kg/m3, R1 = 8.59, h ρ = 7500 kg/m3, R1 = 11.

Finally, we present the measured driving-point mobilities from the tests conducted on a vibration isolation platform. One end of the host beam is clamped by a bench vise with the other end free, creating a clamped-free boundary condition. The connection position of the ρ-ABH-DVA is located at 60% of total length of the host beam from the clamped end. The measured mobility is compared with that predicted by the RMSTMM (Fig. 8a). The detailed measurement process is detailed in Methods. Agreement is observed between the two, which validates the proposed theoretical method. The deviations can be attributed to the neglected rotational inertia and shear deformation effects in the model, the dynamic variation of damping with frequency in the theoretical model as well as the material synthesis imperfections. The measured driving-point mobilities of the host beam without and with the ρ-ABH-DVA are also compared (Fig. 8b). It shows that with the deployment of the ρ-ABH-DVA, all resonance peaks of the host beam within the concerned frequency range are markedly suppressed. Specifically, the first resonance peak is reduced by 7.4 dB, with an average reduction of 13.6 dB across all resonance peaks. These findings demonstrate that the ρ-ABH-DVA can effectively suppress vibration responses of the host beam across a broad frequency range above its redshifted threshold frequency, thereby validating its excellent dual-ultra wave absorption performance.

Discussion

Acoustic metamaterials (AMs) offer unprecedented potential for manipulating acoustic and elastic waves in noise and vibration control applications. While conventional thickness-tailored ABH metamaterials—which overcome the narrowband limitation of conventional AMs and enable broadband wave manipulation with lightweight structures—have attracted substantial interest, they still face several constraints. These include difficulties in operating at deep-subwavelength scales within low-frequency regimes, inherent structural weakening, and ultra-precision machining requirements. Here, we transcend these limitations through a paradigm-shifting approach: deep-subwavelength ABH metamaterials (ρ-ABH) engineered via power-law density tailoring. Integrated theoretical and experimental analyses demonstrate that ρ-ABH achieves a fivefold redshift in both the cut-on frequency and the damping-enhanced threshold frequency compared to conventional thickness-tailored ABHs, arising from unprecedented wave compression induced by fourth-order density gradients. This breakthrough unlocks dual-ultra vibration damping/absorption at a deep-subwavelength scale of λ/11, where energy accumulation is amplified by over an order of magnitude. Furthermore, the inertial grading mechanism induces intrinsic wave amplitude decay, in stark contrast to the amplitude amplification exhibited by thickness- or modulus-tailored ABHs. Through avoiding structural weakening by design, ρ-ABH eliminates the fatigue and fracture risks inherently associated with stiffness-reduced regions in conventional ABHs. Systematic parameter studies further quantify the influence of key factors on performance metrics, identify their influential ranges and provide practical guidelines for implementation (see Supplementary Note 2). Critically, composite-fabricated ρ-ABH as a DVA experimentally validates this exceptional dual-ultra performance. This breakthrough design addresses the critical frequency-scale bottleneck inherent in both metamaterial designs and conventional vibroacoustic control, eliminates inherent fatigue and fracture vulnerabilities of traditional ABH designs, and transforms the formidable manufacturing challenge of ABH from one of ultra-precision machining to controllable material synthesis—paving the way for next-generation vibration and noise mitigation technology. It is also noteworthy that this study primarily focuses on the underlying physical principles and experimental realization of a ρ-ABH. Further investigation into other applications such as wave isolation will be pursued as future research topics.

Methods

Methodological framework of RMSTMM

The combined system in Fig. 3a can be regarded as a planar branched multibody system shown in Fig. 3b which is modeled using the RMSTMM: The host beam and the ρ-ABH-DVA are both modeled based on the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory; element 1 is the ρ-ABH beam; element 2 is the connector; element 3 is the connection point between different transmission paths, modeled as a massless virtual element; elements 4 and 5 comprise the host beam. In Fig. 3b, \({O}_{j}{x}_{j}{y}_{j}\) and \(Oxy\) represent the local (for element j) and global inertial coordinate systems, respectively. The state vector for the input and output ends of the jth element is defined as \({{{{\bf{Z}}}}}_{j,P}={[X,Y,{\Theta }_{z},{M}_{z},{Q}_{x},{Q}_{y}]}_{j,P}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\), where P denotes input I or output O. The basic flow of the RSMTMM is as follows. First, the transfer equations and geometrical constraints at the inputs and outputs of each element are determined. Subsequently, according to the topology of the combined system, the elements are assembled to obtain the reduced transfer matrix at each connection, the column vectors of the load function, and the state vectors at the outputs of the system. Finally, the eigenfrequencies and steady-state response of the system at each point are obtained by combining the reduced transformation with the system boundary condition. The RMSTMM formulations are summarized in the Supplementary Note 1. As an example, we use VeroClear from the Stratasys Digital Materials Series 1647 for the uniform parts. The material density gradually varies from VeroClear (density: 1160 kg/m³) according to Eq. (1) with p = 4. All elements have a width of b = 20 mm. Supplementary Table 1 lists the material and geometric parameters of the system.

2D model parameters

The material parameters of the 2D model are kept consistent with those of the 1D case. The associated geometrical parameters are listed to Supplementary Table 2.

Sample and system parameters

For the fabricated sample, the length and the thickness of the ABH part with power-law density variation measure 0.06 m and 0.004 m, respectively. The length li of each discretized density value is calculated by \({l}_{i}={l}_{x,i+1}-{l}_{x,i},i\in [1,6]\) with \({l}_{x,i}={(({h}_{0}/{({\rho }_{i}/{\rho }_{0})}^{0.5}-{h}_{tip})/\varepsilon )}^{0.5}\).

PU resin is selected for the uniform section, with a Young’s modulus of 1 GPa, density of 1070 kg/m3, loss factor of 0.0609 and length and thickness of 0.02 m and 0.004 m, respectively. A viscoelastic damping layer, featuring a thickness of 1 mm, Young’s modulus of 30 MPa, density of 980 kg/m3, and loss factor of 0.6, is attached to the density power-law varying section of the ABH. Aluminum alloy is used for the connector (dimensions: 0.008 m × 0.016 m) and the host beam (dimensions: 0.55 m × 0.01 m), with Young’s modulus of 71 GPa, density of 2810 kg/m3, and loss factor of 0.001.

Measurements of driving-point mobilities

The experimental setup comprised an excitation system and a signal acquisition system. The excitation system employed a signal generator (DG 1022Z) to produce frequency-swept signals ranging from 1 to 1200 Hz. These signals were amplified by a power amplifier (YE5871A) before being transmitted to a modal shaker (JZK-5), which applied sinusoidal excitation forces at the free end of the host beam. An M5 × 5 mm threaded hole was fabricated at the free end to facilitate connection with the shaker via a dual-end stud.

The signal acquisition system utilized an impedance head (CL-YD-331) and a laser scanning vibrometer (Polytec OFV-505) to measure the excitation force and vibration velocity at the driving point. These signals were then transmitted to a PC-based data analysis system through a data acquisition device (INV3062-C12) to calculate the driving-point mobility frequency response of the host beam. A sampling frequency of 3072 Hz was maintained, corresponding to 2.56 times the maximum excitation frequency to ensure data accuracy.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The methodologies and equations required to reproduce the findings and figures are fully described within the manuscript and Supplementary Information.

References

Liu, Z. et al. Locally resonant sonic materials. Science 289, 1734–1736 (2000).

Cummer, S. A., Christensen, J. & Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16001 (2016).

Ma, G. & Sheng, P. Acoustic metamaterials: From local resonances to broad horizons. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501595 (2016).

Chen, Y., Liu, H., Reilly, M., Bae, H. & Yu, M. Enhanced acoustic sensing through wave compression and pressure amplification in anisotropic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 5, 5247 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. All-in-one: An interwoven dual-phase strategy for acousto-mechanical multifunctionality in microlattice metamaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2420207 (2025).

Mei, J. et al. Dark acoustic metamaterials as super absorbers for low-frequency sound. Nat. Commun. 3, 756 (2012).

Li, J., Wang, W., Xie, Y., Popa, B.-I. & Cummer, S. A. A sound absorbing metasurface with coupled resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 91908 (2016).

Jiménez, N., Romero-García, V., Pagneux, V. & Groby, J.-P. Rainbow-trapping absorbers: Broadband, perfect and asymmetric sound absorption by subwavelength panels for transmission problems. Sci. Rep. 7, 13595 (2017).

Duan, M., Yu, C., Xin, F. & Lu, T. J. Tunable underwater acoustic metamaterials via quasi-helmholtz resonance: From low-frequency to ultra-broadband. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 071904 (2021).

Fang, X., Wen, J., Bonello, B., Yin, J. & Yu, D. Ultra-low and ultra-broad-band nonlinear acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 8, 1288 (2017).

Fang, X., Lacarbonara, W. & Cheng, L. Advances in nonlinear acoustic/elastic metamaterials and metastructures. Nonlinear Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-10219-4 (2024).

Maddi, A. et al. Frozen sound: An ultra-low frequency and ultra-broadband non-reciprocal acoustic absorber. Nat. Commun. 14, 4028 (2023).

Mironov, M. A. Propagation of a flexural wave in a plate whose thickness decreases smoothly to zero in a finite interval. Sov. Phys. Acoust. 34, 318–319 (1988).

Pelat, A., Gautier, F., Conlon, S. C. & Semperlotti, F. The acoustic black hole: A review of theory and applications. J. Sound Vib. 476, 115316 (2020).

Huang, W., Ji, H., Qiu, J. & Cheng, L. Wave energy focalization in a plate with imperfect two-dimensional acoustic black hole indentation. J. Vib. Acoust. 138, 61004 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. Acoustofluidic black holes for multifunctional in-droplet particle manipulation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm2592 (2022).

Mousavi, A., Berggren, M., Hägg, L. & Wadbro, E. Topology optimization of a waveguide acoustic black hole for enhanced wave focusing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 155, 742–756 (2024).

Denis, V., Pelat, A., Gautier, F. & Elie, B. Modal overlap factor of a beam with an acoustic black hole termination. J. Sound Vib. 333, 2475–2488 (2014).

Tang, L., Cheng, L., Ji, H. & Qiu, J. Characterization of acoustic black hole effect using a one-dimensional fully-coupled and wavelet-decomposed semi-analytical model. J. Sound Vib. 374, 172–184 (2016).

Huang, K., Zhang, Y., Rui, X., Cheng, L. & Zhou, Q. A multibody dynamics approach on a tree-shaped acoustic black hole vibration absorber. Appl. Acoust. 210, 109439 (2023).

Krylov, V. V. & Tilman, F. J. B. S. Acoustic ‘black holes’ for flexural waves as effective vibration dampers. J. Sound Vib. 274, 605–619 (2004).

Krylov, V. V. & Winward, R. E. T. B. Experimental investigation of the acoustic black hole effect for flexural waves in tapered plates. J. Sound Vib. 300, 43–49 (2007).

Yao, B. et al. Vibration isolator using graded reinforced double-leaf acoustic black holes - theory and experiment. J. Sound Vib. 570, 118003 (2024).

Ma, L. & Cheng, L. Sound radiation and transonic boundaries of a plate with an acoustic black hole. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 145, 164–172 (2019).

Tang, L. & Cheng, L. Impaired sound radiation in plates with periodic tunneled acoustic black holes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 135, 106410 (2020).

Feurtado, P. A. & Conlon, S. C. Transmission loss of plates with embedded acoustic black holes. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142, 1390–1398 (2017).

Zhang, L., Tang, X., Qin, Z. & Chu, F. Vibro-impact energy harvester for low frequency vibration enhanced by acoustic black hole. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 13902 (2022).

Ji, H., Liang, Y., Qiu, J., Cheng, L. & Wu, Y. Enhancement of vibration based energy harvesting using compound acoustic black holes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 132, 441–456 (2019).

Zhao, L., Conlon, S. C. & Semperlotti, F. Broadband energy harvesting using acoustic black hole structural tailoring. Smart Mater. Struct. 23, 065021 (2014).

Du, X., Huang, D. & Zhang, J. Dynamic property investigation of sandwich acoustic black hole beam with clamped-free boundary condition. Shock Vib. 2019, 6708138 (2019).

Zhu, H. & Semperlotti, F. Phononic thin plates with embedded acoustic black holes. Phys. Rev. B 91, 104304 (2015).

Tang, L. & Cheng, L. Broadband locally resonant band gaps in periodic beam structures with embedded acoustic black holes. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 194901 (2017).

Tang, L. & Cheng, L. Ultrawide band gaps in beams with double-leaf acoustic black hole indentations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142, 2802–2807 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Chen, K., Cheng, Y. & Wei, Z. Lightweight-high-stiffness vibration insulator with ultra-broad band using graded double-leaf acoustic black holes. Appl. Phys. Express 13, 017007 (2020).

Lee, J. Y. & Jeon, W. Vibration damping using a spiral acoustic black hole. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 141, 1437–1445 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Noise reduction of add-on acoustic black holes with different topologies based on combined reduced multibody system transfer matrix method and elementary radiators method. Thin Walled Struct. 214, 113366 (2025).

Mizukami, K., Shiratori, M. & Ogi, K. Fiber-steered acoustic black hole beam with low cut-on frequency and high stiffness. J. Sound Vib. 580, 118396 (2024).

Austin, B., Cheer, J. & Bastola, A. Experimental validation of a multi-material acoustic black hole. Proc. Mtgs. Acoust. 52, 065004 (2023).

Huang, W. et al. Low reflection effect by 3D printed functionally graded acoustic black holes. J. Sound Vib. 450, 96–108 (2019).

Zheng, W., He, S., Tang, R. & He, S. Damping enhancement using axially functionally graded porous structure based on acoustic black hole effect. Materials 12, 2480 (2019).

Bao, Y. et al. Ultra-broadband gaps of a triple-gradient phononic acoustic black hole beam. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 265, 108888 (2024).

Chang, L. & Cheng, L. Wave parameters of an acoustic black hole beam from exact wave-like solutions. J. Sound Vib. 608, 119082 (2025).

Lee, J. Y. & Jeon, W. Wave-based analysis of the cut-on frequency of curved acoustic black holes. J. Sound Vib. 492, 115731 (2021).

Whitham, G. B. Linear and Nonlinear Waves (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Rui, X., Wang, G. & Zhang, J. Transfer Matrix Method for Multibody Systems: Theory and Applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Qu, S. et al. Underwater metamaterial absorber with impedance-matched composite. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm4206 (2022).

Stratasys Ltd. PolyJet Materials Data Sheet, https://www.stratasys.com/siteassets/materials/materials-catalog/polyjet-materials/digital-abs-plus/mss_pj_digitalmaterialsdatasheet_0617a.pdf (2016) (accessed 27-Mar-2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (11874303 to Y.Z.), Equipment Pre-Research Field Fund (Grant Nos. 80910010102 to Y.Z.), and Shuangchuang Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. JSSCBS20210240 to Y.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. conceived the idea, conduct the theoretical calculations, and designed the experimental proposal. Y.Z., X.R. and L.C. supervised and guided the research. W.C. and H.Q. carried out the numerical simulations using RMSTMM & FEM and the experiments. G.W. and F.Y. assisted with the experimental measurements. W.C. and Y.Z. wrote the paper. All authors analyzed the data, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiandong Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Che, W., Qin, H. et al. Deep-subwavelength ultra-low and ultra-broadband acoustic-black-hole metamaterials. Nat Commun 16, 11276 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66172-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66172-2