Abstract

The nitrogenous compounds play a substantial role in life. Transformation of N2 into high-value nitrogen-containing organic compounds, not through NH3, is of great significance but poses a long-standing challenge. Compared with d-block metals, the derivatization chemistry of rare-earth metal dinitrogen complexes remains elusive. Here we report the single-electron reductions of tetrametallic samarium dinitrogen complex 1 [L4Sm4N2(THF)2] (L = [(CH2)5C(C4H3N)2]2-) in THF with dipyrrolide dianion as the ligand, to obtain ionic complexes 2 and 3, [L4Sm4N2]M(THF)6 (M = K, Na), respectively. Different from 2, 3 could dissolve in Et2O to give complex 4 [L4Sm4N2Na(Et2O)], featuring a side-on coordination of Na to dinitrogen molecule. When upon extended reaction time, a more nucleophilic complex 5 [L4Sm3N2Na3] is achieved. Moreover, further reaction of 5 with many aroyl chlorides to successfully afford corresponding oxadiazole organic compounds from N2, facilitated by rare-earth metal [(N2)4-] unit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen-containing organic compounds are indispensable in human society and widely used in fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, and bioactive molecules. Nowadays, the energy-intensive synthetic ammonia (NH3) produced by Haber-Bosch process is almost the only nitrogen source for artificial N-containing molecules1,2,3,4. Therefore, an ideal synthesis strategy to generate C − N bonds from N2 directly under mild conditions with less fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emission is a grand goal for chemists. Extensive studies on transition metal (TM)-dinitrogen complexes as well as subsequent nitrogen derivatization reactions over the last 50 years, have extended our understanding of the C − N bond construction. However, compared with TMs, the analogous chemistry of rare-earth (RE) metals in this field is still in its infancy5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

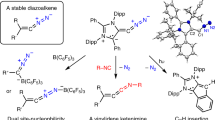

Isolation of the well-characterized dinitrogen complex of f-element metal, [(C5Me5)2Sm2(µ-ƞ2:ƞ2-N2)], was first reported in 1988 by Evans et al.12. So far, although more than 100 crystallographic structures of rare-earth metal dinitrogen complexes, with the exception of the radioactive promethium and readily reducible ytterbium and europium, have been documented, the overwhelming majority fail to serve as the sources of functionalized nitrogen. In the case of [RE(N2)2-], due to the weakly activated molecular N2 ligand, the [(N2)2-] unit is rather regarded as a two-electron reduction reagent with the release of N2, instead of going through potential electrophilic derivatization pathway13,14,15,16. To the best of our knowledge, only three pioneering examples have successfully achieved alkylation of coordinated dinitrogen via more nucleophilic [RE(N2)3-] species until to now (Fig. 1). In 2019, our group reported an example of rare-earth metal-promoted direct conversion of N2 to various hydrazine derivatives with the treatment of [(N2Me2)2-]-bridged discandium complex (I) and carbon-based electrophiles17. When our group expanded scandium to heavier rare-earth metal—lutetium, we succeeded in separating the diazenyl dianion radical [(N2-Me)•2−] (II) under low temperature recently, as the proposed intermediate in the radical disproportionation process18,19. More recently, Mazzanti and co-workers disclosed a thulium [(N2)3-] radical, facilitating N2 functionalization through the similar radical disproportionation reaction to produce [Tm(N2)2-] and [Tm(N2Me2)2-] species (III)20.

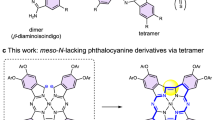

Although rare-earth metal complexes bearing formally [N2]4- units have been synthesized21,22,23, their N2 fragments remain insufficiently reactive, and no conversions into organic nitrogen compounds have been achieved to date. Furthermore, there is considerable interest in developing novel methods for synthesizing nitrogen-containing molecules directly from N2, aiming to access more complex nitrogen-rich compounds beyond the conventional derivatives, such as anilines, amides, nitriles, and hydrazines6,7,8,9,10. In addition, the synergistic effect of polymetallic systems to reduce N2 molecule has been proven an effective way5,24. Herein, we follow the experimental path established by Gambarotta et al. for preparing readily accessible precursor 125. Subsequently, we successfully achieve the isolation of tetranuclear samarium dinitrogen complexes 2, 3 and 4, derived from the single-electron reduction of 1, and trinuclear samarium dinitrogen complex 5. Notably, in complex 5, the dinitrogen moiety exhibits derivatization potential. We investigate the electrophilic reaction of 5 with a variety of aroyl chlorides, yielding oxadiazole derivatives.

Results

Synthesis and structure characterization

The transamination reaction of [(Me3Si)2N]2Sm(THF)2 with 1,1-dipyrrolylcyclohexane is performed under an N2 atmosphere to afford THF-insoluble complex 1 as reddish-brown microcrystals in 86% isolated yield on a reproducible way reported by Gambarotta25. The analog 15N-1 was prepared from 15N2 according to a similar procedure. The N − N stretching frequencies of complexes 1 and 15N-1 display at 1092 cm–1 and 1054 cm–1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 31), in agreement with the different mass between 14N2 and 15N2.

Treatment of 1 with 3 equivalents of K in THF for 12 h at room temperature gives the single-electron reduced product, complex 2, isolated as reddish-brown crystals in 71% yield (Fig. 2). 2 is thermally stable and stored at room temperature without any decomposition. The oxidation-reduction properties of 2 were studied using a cyclic voltammetry experiment. 2 only has two reversible oxidation peaks, but no reversible reduction signal is observed (Supplementary Fig. 44), different from the double-electron reduced result presented by Gambarotta’s group25. The Raman spectrum of 2 shows a strong absorption at 1099 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 32), assigned to the N − N stretch. We also attempted to determine through EPR characterization whether 2 contains a nitrogen radical, but no free organic radical was observed, probably due to the magnetic characteristic of 2 or too weak signal (experiments spanning 4 K to room temperature, both solution and pure solid).

The ionic structure of complex 2 is disclosed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Fig. 3). 2 crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/n with two free THF molecules, and is composed of one K counteranion and four [{(CH2)5C(C4H3N)2}Sm] units. The four Sm atoms arrange to form a rhomb-type structure, in which the coordinated dinitrogen is side-on bonded and end-on bonded to every two Sm metals. Each Sm atom adopts both π-bonding mode and σ-bonding mode with two pyrrolyl rings within the same ligand. The N − N distance (1.413(8) Å) in 2 is longer compared to the usual [(N2)3-] bridged rare-earth metal complexes (1.362(9)-1.405(3) Å)19, and similar to those observed in 1 (1.416(4) Å), {[Ph2C(C4H3N)2]Sm}4(THF)2(µ-N2) (1.412(17) Å)26, {[Et2C(C4H3N)2]Sm}4(THF)2(µ-N2) (1.415(6) Å)21, and {[PhMeC(C4H3N)2]Sm}4(DME)2(µ-N2) (1.42(2) Å)21. The distances of Sm1 − O1 (2.593(4) Å) and Sm1 − N1 (2.301(4) Å) in 2 are relatively longer than the corresponding values of 2.5016(16) Å and 2.1563(18) Å in 1. Given the above differences, along with the comparable N − N bond distances and stretching vibrations in complexes 1 and 2, it is likely that the single-electron reduction occurred at samarium centers rather than at the N − N unit. Thus, we propose that the dinitrogen remains [(N2)4-] state rather than adopting an [(N2)5-] moiety.

The reduction of 1 in the presence of 3 equivalents of Na for 5 h leads to the isolation of complex 3 in 87% yield. 3 and 2 are isostructural with the same arrangement and property, except for the different type of alkaline metal. Unlike 2, 3 could dissolve in Et2O to give a new samarium dinitrogen complex 4 as reddish-brown crystals in 69% isolated yield. A 1094 cm–1 N − N vibrational frequency is observed by Raman spectroscopy, and confirmed by preparing the 15N2 coordinated analog 15N-4 with a stretching band at 1058 cm–1 (Supplementary Fig. 34). As shown in Fig. 4, X-ray crystallographic studies reveal the molecular structure of complex 4 in the triclinic system, space group P-1. The Sm atoms, [(CH2)5C(C4H3N)2]2- dianion ligands, and dinitrogen molecule feature a same bonding mode observed in 2. The dinitrogen molecule (N1 − N2, 1.427(3) Å) is also coordinated to

Na atom solvated by one molecule of Et2O, and one of two Sm atoms with end-on bridging N2 is ligated to THF.

After extending the reaction time between 1 and 3 equivalents of Na in THF, we serendipitously obtain complex 5 as reddish- brown blocky crystals in 26% yield. 5 displays considerable stability in solid state and in the solution of THF for two days at room temperature. The cyclic voltammogram of 5 in THF shows three irreversible processes, likely assigned to the dissociation of the oxidation products.

The solid-state molecular structure of trinuclear dinitrogen complex 5 is presented in Fig. 5 with a monoclinic space group P21/n. Central µ-ƞ2:ƞ2:ƞ2-N2 unit is bridged across three Sm atoms with an overall butterfly-type arrangement. Two Na atoms are ligated along the N − N axis, and concomitantly σ-bonded to pyrrole rings. Meanwhile, a third Na atom is located at the exterior of the whole molecule, connected to three pyrrole rings with one π-bonding mode and two σ-bonding modes. The N − N bond distance in 5 is stretched to 1.541(3) Å, corresponding to a highly activated N2 molecule with a single bond. This value is comparable to those in four-electron reduced dinitrogen complexes facilitated by rare-earth metals, [{[(CH2)5]4-calix[4]-pyrrole}2Sm3Li2](µ-N2)[Li(THF)2](THF) (1.502(5) Å)22, [(THF)2Li[(Et8-calix[4]-pyrrole)Sm]2(N2Li4)] (1.525(4) Å)23, and [{p-tBu-calix[4](OMe)2(O)2}Sm]3(THF)(µ3-ƞ2:ƞ2:ƞ2-N2)[Na(THF)] (1.611(16) Å)27.

Dynamic magnetic susceptibility measurements are performed on 5 at 1k Oe (Fig. 6). The χmT value at 300 K is 1.4 cm3·mol-1·K, substantially larger than that of 0.27 cm3·mol-1·K predicted for three samarium ions (0.09 cm3·mol-1·K for one free SmIII). This is a common result due to the presence of low-lying J = 7/2 (SmIII, Δ = 1000 cm−1) excited states for SmIII ion, which renders the simple LS coupling scheme insufficient to describe the level population as the temperature is increased and kBT exceeds Δ28. The static magnetic susceptibility data of 5 collected at 10k Oe reveal χmT value of 1.1 cm3·mol-1·K at 300 K, also confirming the existence of temperature-independent paramagnetism. After TIP correction of three Sm ions (χtip = 0.00146 cm3·mol-1·K for each Sm ion), the χmT value at 300 K is equal to 0.28 cm3·mol-1·K, well consistent with three free SmIII ions (0.27 cm3·mol-1·K). In turn, this implies the presence of [(N2)4-] moiety.

Functionalization of complex 5

To date, the total number of rare-earth metal-mediated direct functionalization of N2 to diverse N-containing organic compounds remains relatively limited, and only three examples of methylation have been reported. With 5 in hand, we set out to explore its reactivity with a variety of electrophiles to construct C-N bonds. Treatment of 5 with excess aroyl chlorides leads to the formation of a series of substituted oxadiazole derivatives 6a-6e (Fig. 7). In the same way, reactions utilizing 15N-enriched 15N-5 with benzoyl chloride and 4-methylbenzoyl chloride yield 15N-6a and 15N-6b, separately, confirming that all nitrogen atoms in oxadiazoles originate from coordinated N2. The 15N NMR spectra of 15N-6a and 15N-6b depict apparent singlets at δ 298.77 and 296.54 ppm (see Supporting Information for details, Supplementary Fig. 8 and 11). It is worth mentioning that this represents the direct functionalization of N2 to synthesize oxadiazole derivatives under mild conditions, and simultaneously, it documents the C − N bond formation derived from rare-earth metal [(N2)4-] species.

Attempts to directly isolate the reaction intermediates of 5 with different equivalents of aroyl chlorides were unsuccessful. When the one-pot reaction solution of 5 with benzoyl chloride was quenched with water, high-resolution mass spectra showed the formation of 1,2-dibenzoylhydrazine as a crucial mechanistic intermediate. Upon addition of chlorodicyclohexylborane to this solution, complex 7, incorporating two acyl-cation units, was successfully obtained and characterized. Therefore, based on the experimental results above, we propose that the trinuclear samarium dinitrogen complex 5 mediates the conversion of N2 to oxadiazoles may undergo the following reaction process: (i) sequential nucleophilic addition-elimination reactions of 5 with one and two equivalents of aroyl chlorides; (ii) proton quenching to release organic 1,2-dibenzoylhydrazine; (iii) Lewis acid-promoted intramolecular dehydrative cyclization yielding oxadiazole derivatives (Supplementary Fig. 30).

To investigate the electronic structure of complex 5, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed. As shown in Fig. 8, the spin density distribution of complex 5 indicates that the unpaired electrons are primarily localized on the three Sm centers, with approximately 5.6 α-electrons on each Sm (contributing about 90% of the total spin density, as determined by fuzzy space partitioning). The two N atoms of the N2 unit contribute approximately 6% to the total spin density. This result strongly suggests that the valence states of three Sm centers are closer to +3, with each Sm3+ possessing 5 f-electrons. To further elucidate the bonding nature, we performed a localized orbital locator (LOL) analysis29. Given the approximately symmetric positioning of the three Sm centers around the N2 unit, we selected one Sm–N–N plane for visualization. The LOL map of complex 5 is shown in Fig. 8, where the (3, -1) bond critical points (BCPs) are marked as gray dots. The low electron density values at the Sm–N (3, -1) BCPs, along with positive Laplacian values (∇²ρ(r)) and LOL map, suggest that the Sm–N interactions are predominantly ionic. Additionally, the LOL map clearly reveals the two lone pairs on each nitrogen atom, further supporting this conclusion. Fuzzy bond order (FBO)30 analysis indicates that the bond order of N–N bond is 1.0, while the Sm–N bonds exhibit bond orders of approximately 0.8.

In summary, we have demonstrated the syntheses and structures of ionic tetranuclear samarium dinitrogen complexes 2, 3 and 4, originated from one-electron reduction of neutral precursor 1. Treatment of 1 with excess Na in THF for a long time to afford trinuclear samarium dinitrogen complex 5 with a higher degree of N2 activation. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction, SQUID and DFT are performed to prove the presence of [(N2)4-] moiety. 5 shows a surprisingly outstanding performance in electrophilic derivatization of N2 molecule to give a new N-containing organic compound—oxadiazole derivatives. This process represents a new pathway to construct C − N bond from N2 promoted by rare-earth metal [(N2)4-] species. Working is continuing to explore new reaction systems and the detailed mechanism of N2 functionalization.

Methods

Preparation of complexes 1–5 and 7

Synthesis of 1. THF (10 mL) was added to the mixture of [(Me3Si)2N]2Sm(THF)2 (2.000 g, 3.2 mmol) and 1,1-dipyrrolylcyclohexane (695 mg, 3.2 mmol) in the 40 mL vial containing a magnetic stirring bar, and the resulting dark-brown clear solution was stirred at room temperature for 10 h under an Ar atmosphere. Subsequent exposure to N2 (1 atm) resulted in a dark-brown suspension, which was stirred for an additional 6 h at room temperature. After filtration, complex 1 (1.132 g, 86% yield) was isolated as the brown microcrystalline solid.

Synthesis of 2. In N2 atmosphere glovebox, solid K (70 mg, 1.8 mmol) was added to a mixture of complex 1 (974 mg, 0.6 mmol) and THF solvent (15 mL) in 40 mL vial containing a magnetic stirring bar. After stirring at room temperature for 12 h, the suspension became a dark-brown clear solution. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated to about 5 mL, followed by being stored at -35 °C to give complex 2 (893 mg, 71% yield) as red-brown crystals.

Synthesis of 3. In N2 atmosphere glovebox, solid Na (35 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added to a mixture of complex 1 (811 mg, 0.5 mmol) and THF solvent (15 mL) in 40 mL vial containing a magnetic stirring bar. The suspension was stirred at room temperature for 5 h until the solution became a dark-brown clear solution. Then the resulting solution was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated to about 10 mL, followed by being stored at -35 °C to give complex 3 (904 mg, 87% yield) as red-brown crystals.

Synthesis of 4. Complex 3 (831 mg, 0.4 mmol) was extracted with Et2O, and the filtrate was concentrated and stored at –35 °C to give complex 4 (455 mg, 69% yield) as red-brown crystals.

Synthesis of 5. In N2 atmosphere glovebox, solid Na (35 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added to a mixture of complex 1 (812 mg, 0.5 mmol) and THF solvent (30 mL) in a round bottle containing a magnetic stirring bar. After stirring at room temperature for 12 h, the suspension became a dark-brown clear solution. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was washed with hexane and extracted with large amounts of Et2O. The filtrate was dried in vacuo to get a red-brown powder that was extracted with a THF/Et2O mixed solution. Then the resulting solution was concentrated and stored at –35 °C to give complex 5 (238 mg, 26% yield) as red-brown blocky crystals.

Synthesis of 7. In N2 atmosphere glovebox, complex 5 (100 mg, 54.6 µmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of 15 mL THF/Et2O (1/4, v/v) in 40 mL vial containing a magnetic stirring bar. To the frozen solution, kept at the liquid nitrogen bath, was dropped benzoyl chloride (124 µL, 1.1 mmol) via syringe. The resulting mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature slowly. After adding dichlorobis(cyclohexyl)borane (1 M in hexane, 0.6 mL), the solution was continuously stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The solvents were then removed in vacuo, followed by extraction with Et2O. Evaporation of the solvent at room temperature gives a colorless crystalline product 7 (13.8 mg, 43% yield).

General method for the synthesis of organic oxadiazole

In N2 atmosphere glovebox, complex 5 (50 mg, 27.3 µmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of 10 mL THF/Et2O (1/4, v/v) in 40 mL vial containing a magnetic stirring bar. To the frozen solution, kept at the liquid nitrogen bath, was dropped different aroyl chloride (1.4 mmol) via syringe. The resulting mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature slowly and stirred overnight. After quenching with aqueous HCl solution (1 M, 2 mL), the organic solvent was removed in vacuo, and the crude product was purified by thin-layer chromatography to give the corresponding oxadiazole.

Data availability

Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2416110-2416114 (1–5) and 2471742 (7). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The optimized computational structures are provided separately as an excel file labeled “Source Data”. All other data are available in the supporting information or from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this manuscript. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Walter, M. D. Recent Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Dinitrogen Activation. in Advances in Organometallic Chemistry (Academic Press: New York, Vol. 65, Chapter 5, 2016) 261-377.

Nishibayashi, Y. Ed. Transition Metal-Dinitrogen Complexes: Preparation and Reactivity (Wiley−VCH: Weinheim, 2019).

Tanabe, Y. & Nishibayashi, Y. Catalytic nitrogen fixation using well-defined molecular catalysts under ambient or mild reaction conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202406404 (2024).

Shi, X. et al. Synthesis of pyrimidines from dinitrogen and carbon. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwac168 (2022).

Singh, D., Buratto, W. R., Torres, J. F. & Murray, L. J. Activation of dinitrogen by polynuclear metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 120, 5517–5581 (2020).

Kim, S., Loose, F. & Chirik, P. J. Beyond ammonia: Nitrogen-element bond forming reactions with coordinated dinitrogen. Chem. Rev. 120, 5637–5681 (2020).

Lv, Z.-J. et al. Direct transformation of dinitrogen: Synthesis of N-containing organic compounds via N-C bond formation. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 1564–1583 (2020).

Forrest, S. J. K., Schluschaß, B., Yuzik-Klimova, E. Y. & Schneider, S. Nitrogen fixation via splitting into nitrido complexes. Chem. Rev. 121, 6522–6587 (2021).

Zhuo, Q., Zhou, X., Shima, T. & Hou, Z. Dinitrogen activation and addition to unsaturated C-E (E=C, N, O, S) bonds mediated by transition metal complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218606 (2023).

Wang, G.-X., Yin, Z.-B., Wei, J. & Xi, Z. Dinitrogen activation and functionalization affording chromium diazenido and hydrazido complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 3211–3222 (2023).

Wong, A. et al. Catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to silylamines by earth-abundant lanthanide and group 4 complexes. Chem. Catal. 4, 100964 (2024).

Evans, W. J., Ulibarri, T. A. & Ziller, J. W. Isolation and X-ray crystal structure of the first dinitrogen complex of an f-element metal, [(C5Me5)2Sm]2N2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110, 6877–6879 (1988).

Evans, W. J., Lee, D. S., Ziller, J. W. & Kaltsoyannis, N. Trivalent [(C5Me5)2(THF)Ln]2(µ-ƞ2:ƞ2-N2) complexes as reducing agents including the reductive homologation of CO to a ketene carboxylate, (µ-ƞ4-O2C-C=C=O)2-. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14176–14184 (2006).

Evans, W. J., Lorenz, S. E. & Ziller, J. W. Investigating metal size effects in the Ln2(μ-η2:η2-N2) reduction system: Reductive reactivity with complexes of the largest and smallest trivalent lanthanide ions, La3+ and Lu3+. Inorg. Chem. 48, 2001–2009 (2009).

Lorenz, S. E., Schmiege, B. M., Lee, D. S., Ziller, J. W. & Evans, W. J. Synthesis and reactivity of Bis(tetramethylcyclopentadienyl) Yttrium metallocenes including the reduction of Me3SiN3 to [(Me3Si)2N]− with [(C5Me4H)2Y(THF)]2(μ-η2:η2-N2). Inorg. Chem. 49, 6655–6663 (2010).

Corbey, J. F., Fang, M., Ziller, J. W. & Evans, W. J. Cocrystallization of (μ-S2)2− and (μ-S)2− and formation of an [η2-S3N(SiMe3)2] ligand from chalcogen reduction by (N2)2− in a bimetallic yttrium amide complex. Inorg. Chem. 54, 801–807 (2015).

Lv, Z.-J., Huang, Z., Zhang, W.-X. & Xi, Z. Scandium-promoted direct conversion of dinitrogen into hydrazine derivatives via N-C bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8773–8777 (2019).

Aguilar-Calderόn, J. R., Wei, J. & Xi, Z. The trianionic hydrazido radical (N2)3−: A promising platform for transforming N2. Inorg. Chem. Front. 10, 1952–1957 (2023).

Chen, X., Wang, G.-X., Lv, Z.-J., Wei, J. & Xi, Z. Monomethylation and -protonation of lutetium dinitrogen complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 17624–17628 (2024).

Shivaraam, R. A. K. et al. Dinitrogen reduction and functionalization by a siloxide supported thulium-potassium complex for the formation of ammonia or hydrazine derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414051 (2025).

Bérubé, C. D., Yazdanbakhsh, M., Gambarotta, S. & Yap, G. P. A. Serendipitous isolation of the first example of a mixed-valence samarium tripyrrole complex. Organometallics 22, 3742–3747 (2003).

Guan, J., Dubé, T., Gambarotta, S. & Yap, G. P. A. Dinitrogen labile coordination versus four-electron reduction, THF cleavage, and fragmentation promoted by a (calix-tetrapyrrole)Sm(II) complex. Organometallics 19, 4820–4827 (2000).

Jubb, J. & Gambarotta, S. Dinitrogen reduction operated by a samarium macrocyclic complex. Encapsulation of dinitrogen into a Sm2Li4 metallic cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 4477–4478 (1994).

Gambarotta, S. & Scott, J. Multimetallic cooperative activation of N2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5298–5308 (2004).

Dubé, T., Ganesan, M., Conoci, S., Gambarotta, S. & Yap, G. P. A. Tetrametallic divalent samarium cluster hydride and dinitrogen complexes. Organometallics 19, 3716–3721 (2000).

Dubé, T., Conoci, S., Gambarotta, S., Yap, G. P. A. & Vasapollo, G. Tetrametallic reduction of dinitrogen: Formation of a tetranuclear samarium dinitrogen complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 3657–3659 (1999).

Guillemot, G., Castellano, B., Prangé, T., Solari, E. & Floriani, C. Use of calix[4]arenes in the redox chemistry of lanthanides: The reduction of dinitrogen by a calix[4]arene−samarium complex. Inorg. Chem. 46, 5152–5154 (2007).

Kahn, O. Molecular Magnetism (Wiley-VCH: New York, 1993).

Schmider, H. L. & Becke, A. D. Chemical content of the kinetic energy density. J. Molec. Struct. 527, 51–61 (2000).

Mayer, I. & Salvador, P. Overlap populations, bond orders and valences for ‘Fuzzy’ atoms. Chem. Phys. Lett. 383, 368–375 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22588201 Z.X. and 22201013 J.W.). We thank the Analytical Instrumentation Center at Peking University for the NMR measurements and the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University for the DFT calculations. The authors thank Prof. Wen-Xiong Zhang at Peking University for his valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. carried out the synthesis and characterization of the complexes 1–7. Q.Y. and Y.C. helped with the analysis of crystallographic data and SQUID. J.W. performed DFT calculations and analysed the data. Z.X. and J.W. conceived and conceptualized this project. X.S., J.W., and Z.X. prepared and revised the manuscript. All authors participated in discussions of this research and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, X., Yuan, Q., Chen, Y. et al. Conversion of N2 into oxadiazoles promoted by a multinuclear samarium complex. Nat Commun 16, 11277 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66173-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66173-1