Abstract

As a powerful oxidant, atomic oxygen (O) holds considerable promise for a variety of biomedical and industrial applications. However, the inability to quantify solvated oxygen atoms has prevented the determination of the fundamental parameters governing its behaviour in relevant aqueous environments. Here, we directly image ground-state oxygen atoms in water using femtosecond two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence. Measurements show that oxygen atoms persist for tens of microseconds in water, penetrating hundreds of micrometres into the liquid. This observed longevity has significant implications, suggesting a need to re-evaluate existing models of solvated atomic oxygen reactivity and transport. Beyond atomic oxygen, this technique is broadly applicable to other solvated atomic species of interest, including nitrogen (N) and hydrogen (H). This work establishes that radical atomic species can be quantified in liquid with ultrafast laser spectroscopy, providing the basis for the determination of key properties including reaction rates, chemical lifetimes, and Henry’s law constants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several recent studies have demonstrated the potential of atomic oxygen (O) for a variety of uses in biomedicine and chemistry1,2,3,4, primarily due to its oxidative capacity5. These nascent applications are often contingent on O atoms reacting in liquid6,7,8. However, the behaviour of O in aqueous environments (Oaq) remains enigmatic, as little is known about its reaction rates9, diffusion coefficients, or transport from the gas phase10,11. This lack of understanding persists due to the inability to accurately measure concentrations of O in liquid, an issue compounded by the absence of the aforementioned chemical reference data12. Attempts to characterise Oaq with chemical probes have proven problematic, as O often degrades the probes or reacts indistinguishably from other reactive oxygen species (ROS)13,14,15. Understanding the dynamics of solvated O requires a selective and quantifiable diagnostic capable of spatial and temporal resolution. The prerequisites for such a method include the ability to probe the atomic ground state, where the vast majority of O atoms reside at room temperature, as well as a mandate to leave the ambient liquid environment unperturbed.

Optical techniques applied to the liquid phase are natural candidates for the direct detection of solvated O. Of these, two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence (TALIF) offers the highest degree of spatiotemporal resolution and can measure atoms in the ground state. TALIF is commonly used to quantify several reactive atomic species in the gas phase, including O16,17, N18, and H19,20. In O, it relies on the simultaneous absorption of two photons tuned to the O(2p4 3PJ) → O(3p 3PJ) resonance. In the absence of other de-excitation mechanisms, O(3p 3PJ) fluoresces at 844.6 nm with a radiative lifetime of ~35 ns21. The principal challenge for applying TALIF in liquid is obtaining a detectable signal, as the liquid phase strongly limits the efficiency of both the excitation and the fluorescence of the atomic species. Excitation is inherently limited by the pulse energy that can be applied without appreciably heating the liquid, while the highly collisional liquid environment rapidly quenches the laser-excited state. However, with a sufficiently fast excitation and detection scheme, it is possible to overcome these constraints.

Here, we demonstrate that solvated O atoms can be imaged using a femtosecond (fs) laser for TALIF in liquid. With fs-TALIF, the limitations of existing methods for measuring Oaq can be effectively addressed. Direct measurements highlight the stability of O atoms in water, suggesting a chemical lifetime of at least tens of microseconds. With an induced flow, this allows Oaq to reach depths of several hundred micrometres. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations are also used to approximate the collisional quenching rate of laser-excited Oaq. This enables estimates of solvated O densities, along with a Henry’s law constant. These results establish fs-TALIF as a viable technique for directly quantifying solvated atomic species and provide a framework for determining the fundamental parameters that govern their behaviour.

Results and discussion

Detection of solvated O atoms

Detection of an atomic species using TALIF is fundamentally about two processes: the efficiency of excitation and the effective branching ratio, which describes the fraction of laser-excited atoms that subsequently emit a photon in the wavelength region of interest21. The primary constraints for applying TALIF in liquid concern these processes, as limitations on pulse energy restrict excitation efficiency, while the highly collisional environment results in a very low branching ratio. However, both of these can be addressed using an ultrafast (fs) laser17.

For excitation of ground-state O to occur, two photons with the appropriate combined energy must concurrently reside within the absorption cross section of the atom. Assuming an identical beam geometry and pulse energy, a laser pulse that is n-times faster will produce an n-fold higher density of photons. As TALIF is a two-photon process, this will increase instantaneous two-photon absorption by a factor of n2 and the total number of excitation events by n over the duration of the laser pulse. As a result, a faster laser proportionally increases the excitation efficiency. This is of particular importance for aqueous environments where the laser should not considerably heat (or boil) the target liquid. The use of a femtosecond laser allows for a lower pulse energy while still achieving sufficient excitation for detection.

The second major limitation in applying TALIF in a liquid environment is the high collisional frequency compared to the gas phase. This has consequences for both the two-photon excitation and the effective branching ratio. Considering the vibrational modes of H2O, nearly all collisions between Oaq and H2O likely result in the quenching of laser-excited O. If a laser pulse is not appreciably faster than the rate of collisional de-excitation, two-photon pumping will not sufficiently populate the upper state to allow for detection of the fluorescence signal. Moreover, the highly collisional environment raises the detection threshold considerably. For solvated O atoms, collisional quenching occurs several orders of magnitude more frequently than radiative de-excitation21, so the resultant effective branching ratio is very small. This makes the additional excitation efficiency provided by the ultrafast laser critical for Oaq detection.

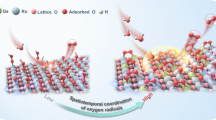

To provide an efficient source of O atoms to a target liquid, O delivery was mediated by the COST Reference Source22, a microscale atmospheric pressure plasma jet (μ-APPJ). A well-studied and reproducible reference source23,24, the COST jet generates O in the active plasma through dissociative collisions between high-energy electrons and molecular oxygen (O2) present in the feed gas25. The O atoms produced in the active plasma are subsequently expelled via the gas flow into the plasma-free effluent (also free of electrons22, metastables9,26, and electric fields22). In this study, peak O densities in the effluent were measured to be around 1.5 × 1015 cm−3, representing a dissociation fraction above 2% at a gas temperature of 350 K. As a continuous-wave source, the plasma delivered a consistent flux of O atoms to a volume of deionised water held in a quartz cuvette 5 mm from the nozzle of the jet. Previous modelling studies of the COST jet10,27, when applied to the operating conditions used here, suggest a total O flux as high as 3 × 1016 s−1 at the water interface. The highest density of solvated O is then expected directly below the deformation zone created by the incident gas flow on the water surface, as shown in Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of the experimental setup with the fs laser incident perpendicular to the water surface. An ICCD image of the water surface during plasma operation is shown at right with error bars denoting the FWHM uncertainty in the location of the interface. With a 2 slm gas flow, the atmospheric pressure plasma jet provided a total O flux at the water surface of up to 3 × 1016 s−1.

Given the constraints for a laser diagnostic to image solvated O atoms, a series of measurements was required for the confirmation of a TALIF signal from Oaq (see Methods). The first measurement recorded the fluorescence with the plasma on and the laser tuned to the two-photon resonance of O (225.7 nm). Next, a laser background was taken at the same excitation wavelength with the plasma off. For the laser background, the gas flow was maintained to ensure a consistent air–water interface between the two measurements. Another measurement was then recorded with the plasma on, but with the ICCD gated after the laser pulse. With the delayed gate, if the fluorescence originates from O, the signal below the water surface should be quickly quenched, while the gas-phase fluorescence would persist due to its longer lifetime. Finally, the first two measurements were repeated with the laser tuned off resonance. For the off-resonance measurements, any observed signal cannot be attributed to O TALIF.

The results of this series of measurements are shown in Fig. 2a–d and conclusively demonstrate the presence of an on-resonance O fluorescence signal, below the water surface, with a laser-excited lifetime significantly shorter than gas-phase O. Fig. 2a shows the on-resonance, plasma-on measurement after subtraction of the 225.7 nm laser background. The background-subtracted signal in the water peaks at ~30 counts s−1 near the interface. It decreases away from the surface but is evident several hundred micrometres into the water. Fig. 2b shows the signal recorded with the ICCD gated 3 ns after Fig. 2a. As expected, it indicates that the fluorescence in water is quickly quenched while the gas-phase signal remains. For the delayed gate, the intensity of the gas-phase fluorescence is approximately halved. This confirms that the signal observed below the water surface in Fig. 2a does not originate from Og, either directly or as a reflection. In Fig. 2c, the ratio of the on-resonance signal and the laser background is shown for pixels below the water surface with a raw intensity of at least 12 counts s−1. The signal-to-background ratio is at least five for the majority of pixels along the laser path and has a clear maximum near the water surface, where Oaq densities should be highest. Coupled with the results of the delayed-gate measurement, the magnitude and spatial extent of the signal-to-background ratio are further evidence that solvated O atoms are responsible for the observed fluorescence below the water surface. Finally, the laser background-subtracted off-resonance measurement is displayed in Fig. 2d. The absence of an off-resonance signal, along with the ultra-narrowband interference filter used on the ICCD, reaffirms that O TALIF is shown in Fig. 2a, b and lends additional confidence that Oaq is being imaged below the water surface.

a The on-resonance, laser background-subtracted O fluorescence signal, recorded with the ICCD gated to capture the laser pulse and TALIF signal in water. The location of the water surface is denoted by the dashed red line. b The time-delayed, on-resonance O fluorescence signal recorded 3 ns after (a). c The signal-to-laser background ratio for (a) for pixels beneath the water surface with a signal of at least 12 counts s−1. d The off-resonance (wavelength centred at 224.7 nm), laser background-subtracted signal, gated to include the laser pulse. e The lifetime of the fluorescence signal above and below the water surface. The surface and the error bars corresponding to the FWHM uncertainty in its location are shown in pink. f Absolute densities of solvated atomic O. Here, (b) has been subtracted from (a) to account for scattering from the intense gas-phase fluorescence.

To further investigate the quenching environment in the gas and liquid phases, a complementary study was performed to record effective lifetimes of laser-excited O with a 0.5 ns ICCD gate. To accomplish this, a technique was used that differentiates the fluorescence of species affected by distinct quenching environments28, where the lifetime and relative signal strength at each pixel are recovered from a series of time-delayed images. The resulting lifetime data are shown in Fig. 2e. Only data with a signal-to-noise ratio of at least 1 are displayed. In the gas phase, effective lifetimes range from 1 to 5 ns, decreasing in proximity to the water surface. This is likely due to the higher concentration of H2O in the gas phase near the liquid, which efficiently quenches laser-excited O20,29. Below the water surface, effective lifetimes are less than 0.25 ns — the detection limit of this technique. This reflects very efficient quenching of the laser-excited species, as would be expected for solvated O atoms. This clear distinction between quenching environments further confirms that the fluorescence observed below the water surface originates from Oaq.

The spatial extent of the signal below the water surface must also be reasonable to claim that it originates from Oaq. Fig. 2a shows that fluorescence is observed at a depth of several hundred micrometres. To reach this depth, Oaq must have limited reaction pathways in water. It was previously assumed that solvated O would react directly with water molecules to produce hydroxyl radicals. However, molecular dynamics simulations have identified an energy barrier that prevents this reaction30,31, a finding supported by several empirical studies10,13,32. Alternatively, Oaq can react with solvated O2 from the gas phase to form O39,12. In the absence of other reaction partners in DI water, this is the dominant extinction pathway of Oaq9. Assuming that the extended duration of He/O2 gas flow on the small water surface effectively outgases the DI water in the cuvette, the concentration of solvated O2 can be estimated using Henry’s law11. At an effluent temperature of 350 K, the extrapolated concentration of solvated O2 is 2.0 × 1015 cm−3. With a rate constant of k = 5 × 10−12 cm3 s−1 for the reaction between O and O2 in the liquid phase27,33, a chemical lifetime of 100 μs for Oaq can be estimated. As a result, a flow velocity of ~ 1 m/s in the closest half mm to the surface would be sufficient to explain the observed spatial extent of Oaq. Fluid modelling with similar APPJs has indicated that this is realistic near the water surface considering the angled orientation of the plasma jet, the small water volume, and 2 slm flow rate used here27,34,35.

Density calibration of solvated O atoms

The direct detection of solvated O demonstrates that femtosecond TALIF can be used to image atomic species in liquid. However, an accurate density calibration is essential for the successful application of this technique. For TALIF measurements in the gas phase, this is regularly completed with noble gases of known density20. Xenon (Xe), for instance, is often used to calibrate TALIF measurements of O, given its nearly identical two-photon excitation and fluorescence scheme21,36,37,38. An essential feature of this calibration procedure is the ability to establish the effective branching ratio of the two species. In water, the nearly instantaneous collisional quenching of laser-excited O and Xe precludes an accurate in situ determination of their respective branching ratios. Given the additional uncertainties introduced by changes in the experimental setup required for Xe TALIF, an alternative approach to density calibration was considered.

Here, Oaq densities are calibrated by comparing the time-normalised intensities of the TALIF signals in the gas and liquid phases37. This is advantageous as it only requires an estimate of the effective branching ratio for O in liquid, as opposed to a technique incorporating Xe TALIF in liquid. The equation for the density calibration of Oaq is given in equation (1). The subscripts aq and g denote the aqueous and gas phase, respectively, for the effective branching ratios (a), normalised signal intensities (S), and O densities (nO):

Atomic O densities in the gas phase (\({n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}\)) were calibrated using Xe TALIF measurements in accordance with the procedure outlined previously21,37,38. The gas-phase calibration included in situ effective lifetime measurements of laser-excited O and Xe atoms at atmospheric pressure. For the liquid phase, the effective branching ratio of Oaq was estimated with AIMD simulations of solvated O atoms39,40,41,42. By accounting for the diffusion of O in room temperature water and assuming that all collisions result in quenching of the laser-excited state, AIMD simulations estimated the collisional quenching rate of O(3p 3PJ) to be 1.45 × 1011 s−1. The corresponding effective branching ratio (aaq) is then 1.99 × 10−4, almost three orders of magnitude less than the value of ag recorded in situ for the operating conditions used here. With an estimate for aaq, solvated O densities were calculated using equation (1). The result of the calibration applied to the laser background-subtracted measurement (Fig. 2a), is shown in Fig. 2f. Verbatim, it depicts solvated O densities on the order of 1016 cm−3 near the water surface. However, uncertainty in the calibrated densities of Oaq is substantial, based on the assumption that all collisions between Oaq and water molecules result in de-excitation. If collisions occur without quenching, the branching ratio would increase accordingly, reducing the estimated values of \({n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{aq}}}}}}\). Therefore, the calibrated Oaq densities presented here should be interpreted as upper-bound approximations, with accuracy limited by uncertainty in the collisional quenching coefficient of laser-excited Oaq by water.

Spatial mapping of O in water

To further examine O transport at the air–water interface, the laser was scanned horizontally across the region where the gas flow impinges on the surface. The resulting measurements are compiled in Fig. 3a. The density calibration for Oaq was applied for Fig. 3b, c, where \({n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{aq}}}}}}\) is shown as a function of penetration depth.

a A composite of O TALIF measurements from a series of scans across the air–water interface. b Calibrated Oaq densities in the region where the gas flow is nearly perpendicular to the water surface. The depth denotes the distance to the air–water interface. Densities within the FWHM uncertainty of the surface position are not shown. c Oaq densities as a function of depth in the liquid, averaged over ±0.2 mm from the zero position on the x axis of (b).

As expected, the highest concentration of Oaq was found on the left side of the deformation zone, where the gas flow is nearly perpendicular to the surface. This corresponds to the region where x<0.5 mm in Fig. 3a. Here, maximum densities of solvated O are as high as 1016 cm−3 near the surface of the water and decrease with depth. No Oaq is observed beyond a depth of 0.4 mm. On the right side of the deformation zone, where the gas flow is more parallel to the surface, only noise is evident below the air–water interface. In this region, the penetration depth of solvated O is mediated by diffusion rather than the induced flow. Applying the diffusion coefficient estimated by AIMD simulations for Oaq, a 0.5 μm penetration depth is predicted within one chemical lifetime, well below the resolution of this experimental setup. The observed spatial distribution of Oaq is therefore in good agreement with expectations based on the distinct transport regimes for solvated O. These spatially resolved measurements highlight the importance of the induced flow for both the direct detection of Oaq, as demonstrated here, and applications that require penetration depths >1 μm.

In addition to probing liquid-phase dynamics, fs-TALIF enables the study of interfacial transport of atomic species. While this experiment was not explicitly designed to determine a Henry’s law constant, one can still be estimated if local equilibrium is reached between the gas and liquid phases near the water surface11. This assumption is likely valid in the present setup, given the steady-state nature of the O flux and induced flow, along with the relatively long chemical lifetime of Oaq in DI water. A dimensionless Henry’s law constant, defined as \({H}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{{{{\rm{CC}}}}}={n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{aq}}}}}}/{n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}\), can then be established from measurements of O on either side of the air–water interface. In this study, O densities appear to reside around 1015 cm−3 above the water, with higher than usual uncertainty due to imaging the fluorescence through the deformed surface. This value for \({n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}\) would give a dimensionless Henry’s law constant of \({H}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{{{{\rm{CC}}}}}\approx 10\). Considering the caveats associated with the absolute calibration of \({n}_{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{{\rm{aq}}}}}}\), this should be regarded as an upper-bound estimate. Nevertheless, the Henry’s law constants for other atomic reactive nonmetals suggest that this value is reasonable. Those with available data have dimensionless Henry’s law constants that fall between hydrogen (H CC = 6.4 × 10−3) and chlorine (H CC = 57), including fluorine (H CC = 0.50), iodine (H CC = 2.0), and bromine (H CC = 30)11. In addition, a recent study modelled the effect \({H}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{\,{{{\rm{CC}}}}}\) would have on phenol consumption in plasma-treated solution27. It was determined that a wide range of prospective Henry’s law constants could give the observed trends in phenol consumption, with model and experiment diverging as \({H}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{{{{\rm{CC}}}}}\) approached 20. This further supports the estimate of \({H}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{{{{\rm{CC}}}}}=10\) derived from direct imaging of O, if appropriately interpreted as an upper-bound value.

Additional studies employing fs-TALIF should make a concerted effort to refine the collisional quenching coefficients of solvated laser-excited atomic species, as the uncertainty in the branching ratio propagates to all other quantities derived from the density calibration. An accurate assessment of the collisional quenching coefficient would allow many currently unknown parameters to be quickly established, including Henry’s law and reaction rate constants, chemical lifetimes, and diffusion coefficients for atomic species of interest. This would aid in the implementation and optimisation of a host of novel applications predicated on solvated reactive atomic species.

In summary, this work demonstrates the direct imaging of ground-state O in liquid using femtosecond TALIF. This technique provides spatiotemporal resolution of solvated O, offering an alternative to existing indirect detection methods. We also introduce an approach for density calibration that utilises AIMDs simulations to estimate the effective branching ratio of laser-excited Oaq. This allows in situ quantification of solvated O without the need to employ inherently problematic chemical probes. Our findings definitively indicate that O atoms are stable in water and persist for tens of μs based on the presence of Oaq several hundred micrometres below the water surface. In addition to atomic O, this non-intrusive approach is applicable to other solvated atomic species of interest, including N and H. This diagnostic has significant implications for determining the fundamental parameters of solvated atomic radicals, including reaction rates, diffusion coefficients, and Henry’s law constants. The determination of these properties will enhance understanding of the behaviour of these species in the aqueous phase and facilitate their use for a variety of biomedical and chemical applications.

Methods

COST reference microplasma source

The atomic oxygen delivered to the water in these experiments was produced by the COST jet, a reference atmospheric pressure plasma jet22. The COST jet is a 13.56 MHz RF plasma source with a 1 mm × 1 mm × 30 mm plasma channel bound by two stainless steel electrodes, along with two quartz panes that allow optical access to the active plasma. Unlike other plasma jets, the COST jet is uniquely suited for selective ROS delivery as the active plasma is not in contact with the ambient air. The perpendicular orientation of the gas flow and electric field ensures that most electrons22,23 and metastables9,26 are restricted to the active plasma. This, along with the expansive literature available for the COST jet as a reference source, makes it an ideal tool to study O atoms9,23.

To give the best opportunity for Oaq detection, the COST jet was configured to maximise O flux at the water surface. To do so, a more aggressive 2 slm flow was employed along with a 0.3% O2 gas admixture in the He feed gas. Although maximum O densities are found at higher O2 admixtures25,29, ozone formation, via reactions between atomic and molecular oxygen, scales with O225. The lower O2 admixture was used to increase the chemical lifetime of O in the gas and liquid phases. In addition, a relatively high voltage of 300 VRMS was applied to the powered electrode to ignite the plasma and optimise O production. Under these operating conditions, the total flux of O atoms at the water surface may exceed 3 × 1016 s−1, depending on the surface loss probability. This value is based on the densities of O measured in the gas phase, in addition to the transport efficiency of O to the liquid target. To achieve the stated flux, 70% of the O produced by the jet would have to reach the water 5 mm from the nozzle. Two modelling studies of O transport in the effluent of a He/O2 COST jet suggest that this is more than reasonable when considering differences in flow rate and O2 admixture10,27.

Xe TALIF measurements for the absolute density calibration of O in the gas phase were performed by flowing a helium/air/xenon admixture through the jet without plasma ignition, similar to the technique used in Myers et al.29. The total concentration of Xe in the feed gas was 0.03%.

Optical measurements

The laser source used for the fs-TALIF experiments is an amplified femtosecond laser (Solstice ACE, Spectra-Physics), equipped with an optical parametric amplifier (TOPAS Prime Plus, Light Conversion), capable of generating 100 fs pulses with >2 μJ energy/pulse, tunable ~225 nm at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. A fused silica prism was used to separate UV light from all other frequencies, and a 20 cm focal length fused silica lens focused the laser on the surface of the water. The imaging system consisted of a low noise CCD camera (Pixis 512, Princeton Instruments) equipped with a gated double-stage intensifier (Quantum Leap, Stanford Computer Optics) capable of varying gating times as low as 0.3 ns. A variable-focus 50 mm lens (Nikkor) with a spacer provided imaging from a distance of 5–10 cm. Collectively, the imaging system allowed for a minimum ICCD gate of 2.2 ns, utilised for all images presented here. The time delay between the laser excitation and ICCD gating was controlled by a digital delay generator (DG645, Stanford Research Systems).

For TALIF measurements, the laser system was tuned to the appropriate wavelength for two-photon excitation (225.7 nm for O and 224.3 nm for Xe36), and the fluorescence collected by the imaging system was passed through interference filters centred at 844.6 nm for O (bandwidth of 0.8 nm) and 830 nm for Xe (bandwidth of 10 nm). The 0.8 nm ultra-narrowband filter for O was of particular importance for Oaq detection, isolating the fluorescence signal and excluding inelastically scattered laser light from the bulk liquid.

The experimental setup employed to image solvated O atoms is depicted in Fig. 1. It consists of a source of O atoms (the COST jet) incident on a water target, a femtosecond laser with the requisite optics, and an ICCD to collect the fluorescence signal. The effluent of the plasma jet was directed onto a volume of deionised (DI) water in a quartz cuvette. DI water was used to maximise the chemical lifetime of O atoms in the aqueous phase, allowing the best chance for detection. The fs laser was focused on the surface of the water vertically along the z axis and the plasma jet was positioned towards the interface at an angle 22.5 degrees from the normal. The ICCD was then placed along the y axis at a distance of 5 cm from the imaged region. To limit the effect of evaporation on the water level during the course of the measurement, the cuvette was linked to a large external reservoir of DI water (~10 litres). Despite this, slow evaporation does occur, lowering the water level ~35 μm per hour. This is derived from a shift of 22 μm in the water level between two measurements 37 minutes apart. This shift is almost imperceptible over the time scale of a single measurement (~15 minutes), is considerably less than the uncertainty in the location of the interface, and is accounted for by recording the location of the surface periodically over composite measurements. The gas flow from the plasma jet impinging on the air–water interface creates a deformation of the water surface on the order of 1–2 mm. To determine the exact position of the water surface, the ICCD recorded images with microsecond gating times, and the resulting images were processed using edge detection filters. Matlab image processing was able to identify the location of the interface with a half width at half maximum (HWHM) precision of approximately 100 μm. The mean full width at half maximum (FWHM) uncertainty for each measurement is indicated by error bars in Figs. 1, 2e, f, and 3a.

To identify fluorescence from solvated O, a series of measurements was required: First, the TALIF signal was recorded with the laser tuned on-resonance (225.7 nm), plasma source on, and the ICCD gated to include the laser pulse (t = 0 ns). This contained the fluorescence signal from solvated O atoms, as well as contributions from unwanted sources. Next, the laser background was taken with the plasma off (no O atoms) and the same gate delay. To identify the O fluorescence, the laser background was then subtracted from the first plasma-on measurement. The resulting image is displayed in Fig. 2a, with the location of the water surface annotated by the dashed red line.

On-resonance measurements were also performed with a delayed ICCD gate. By gating the ICCD after the laser pulse, it was possible to differentiate the very short-lived TALIF signal originating from solvated O (on the order of picoseconds) and fluorescence from gas-phase O, which has an effective lifetime of several nanoseconds. Fig. 2b shows the background-subtracted image at t = 3 ns. A sharp cutoff in fluorescence is apparent at the water surface, demonstrating the stark difference in lifetimes between the gas- and liquid-phase signals. To account for any contribution of scattered gas-phase O fluorescence to the signal observed below the water surface, the delayed-gate image was subtracted from Fig. 2a before the density calibration was applied. This results in slight differences in the spatial distributions of Oaq in Fig. 2a, f, and 10–20% lower Oaq densities than would be found otherwise.

A complementary study was completed to investigate the temporal dynamics of the O fluorescence in greater detail. For this test, a 4 μJ per pulse UV pump laser was used to generate the fs-TALIF signal from O in the gas and liquid phases. The fluorescence was collected with a PI Max 1024i and an intensifier gate of 0.5 ns, allowing for superior temporal resolution to the 2.2 ns gate used initially. The results, shown in Fig. 2e, confirm the aggressive quenching environment for solvated O atoms with effective radiative lifetimes of < 0.25 ns.

To further validate that solvated O was the source of the recorded signal below the water surface, measurements were also performed with the laser tuned off-resonance (224.7 nm). With the ICCD gated with the laser pulse, no signal was visible after background subtraction (Fig. 2d). The absence of signal off-resonance, coupled with the much faster decay of the on-resonance fluorescence below the water surface, is clear evidence that solvated O is being imaged directly.

To obtain a 2D image of the O distribution both in water and above the surface, the laser beam was scanned horizontally. Measurements were performed at 13 locations, ~125 μm apart. The resulting images were compiled after accounting for the laser background, and only pixels with more than eight counts s−1 of signal were included. The resulting spatial map is shown in Fig. 3a. During this process, care was taken to account for the water evaporation. For Fig. 3b, a spatial map of the densities below the water surface was compiled using the calibrated signals along vectors normal to the interface. As the orientation of the interface is nearly constant in the region of interest, distortion in the x-direction of the 2D image should be minimal. Only points below the HWHM uncertainty in the location of the surface are included in Fig. 3b, c. As a result, the zero position in the y-direction for both figures is defined as the location of the water surface plus the HWHM uncertainty.

For measurements in air, the COST jet was oriented vertically, and the laser beam was focused horizontally to pass through the effluent region. The 2.2 ns ICCD gate was timed concurrently with the laser excitation, and the fluorescence of the atomic species (O or Xe) was imaged. The jet effluent was vertically scanned to give a 2D spatial map of O and Xe, while the time delay between the laser and the ICCD gate was varied to measure the fluorescence lifetimes of O and Xe. The recorded effective lifetimes were then used to calculate the branching ratio for the absolute density calibration21,29,38. The uncertainty in the gas-phase O density calibration with in situ lifetime measurements was previously found to be ~37%29.

Applying the calibration, O densities in the effluent were found to peak at 1.5 × 1015 cm−3 near the nozzle of the jet. In the absence of a liquid target, O densities 5 mm from the nozzle were 76% of their initial value. This supports the assertion that the total O flux at the water surface was as high as 3 × 1016 s−1, which would require 70% of O atoms to reach the liquid. The persistence of O in the effluent is a function of the relatively high flow rate (2 slm) and small O2 admixture (0.3%). For comparison, a 1 slm He, 0.6% O2 gas flow produced a 30% higher initial O density, but only 43% of O atoms remained 5 mm from the nozzle.

Laser-water interaction

As the TALIF signal depends quadratically on laser intensity, it is important to know the influence of the water on the propagation of the femtosecond laser. The linear absorption of the 224–226 nm laser beam in the water was found to be negligible. Using a fused silica cell with water, the transmission of the UV laser beam vertically through varying water thickness was found to be unaffected by the amount of water over several cm. This finding agreed with the reported values for the water UV absorption coefficient43, which is < 0.1 m−1. This indicates that absorption is not a factor within the few mm probed in these experiments.

The laser intensity may also be influenced by the dispersion of the water. In particular, the group velocity dispersion (GVD) leads to an increased pulse width and a reduction in the peak laser pulse intensity. Using the procedure to estimate the pulse increase due to the GVD reported for 100 fs laser pulses in water at 800 nm44,45, the pulse width τ after propagating through a water layer of thickness L is given by:

where τ0 is the initial pulse width and the GVD coefficient G is given by the second-order dispersion of the refractive index n as a function of the wavelength λ:

Using the Sellmeier equation for the dispersion of the index of refraction of water46:

The GVD from equation (3) for water at 225 nm is 330 fs2/mm, and, using equation (2), the pulse width acquires an insignificant increase from 100 fs to 100.1 fs after passing through 0.5 mm of water.

The conclusion from the linear absorption and pulse stretching studies is that the intensity of the pump laser beam is not significantly affected after propagation through the first few hundred micrometres of water. As a result, the fs-TALIF signal accurately maps the spatial distribution of solvated O atoms in the water, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations

To determine the collisional quenching rate and resulting branching ratio of laser-excited O in water, AIMD simulations were performed to estimate the collision frequency of Oaq with the ambient water molecules. The collision frequency is the average number of ballistic collisions per unit time for a given particle within a given medium:

where τc is the collisional frequency, ρmed is the atomic density of the medium of interest, and t is the time of interest. Vcyl is the volume of the collisional cylinder, which is defined as:

where vp is the velocity of the particle and σp is the collisional cross section. The collisional cross section of atomic oxygen is assumed to be 1.9 × 10−15 cm2, which is half that of diatomic oxygen47. The velocity of O in water at room temperature is unknown. The most accurate way to determine how atomic O diffuses in water is by utilising AIMD, which can account for the electronic, short-range van der Waals (vdW), and long-range vdW interactions, while evolving in time through Newton’s equations of motion.

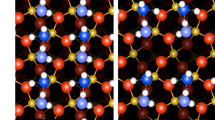

AIMD simulations of liquid water and liquid water with atomic O were performed using the strongly constrained and appropriately normed (SCAN) meta-GGA functional48. SCAN is inherently non-empirical, developed by satisfying all 17 known exact constraints on semilocal exchange-correlation functionals. Thus, the results obtained from SCAN are purely predictive and do not rely on training data. SCAN has been shown to correctly predict liquid water that is denser than ice at ambient conditions. SCAN accurately describes covalent and H bonds due to an improved description of electronic structure and captures intermediate-ranged vdW interactions that further improve the structure and thermodynamics of liquid water49.

Systems were investigated using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)39,40,41,42. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method50,51 was utilised within the density functional theory framework52,53. PAW pseudo-potentials within VASP with the h designation were utilised for all elements. The Gaussian smearing method was used with a width of 0.05 eV to determine the partial occupancies for each wave function. A gamma-centred Monkhorst-Pack541 × 1 × 1 k-point mesh was employed for Brillouin zone sampling. The energy cutoff was increased to 1000 eV to improve the accuracy and stability of the simulations. The electronic self-consistent loop exit criterion was set to 10−4. Simulations are spin-polarised to account for unpaired electrons.

A 90-atom supercell, which includes 30 water molecules, was initially used in the simulations. This original supercell was generated via packmol55 to ensure a reasonable initial structure. Dynamics were carried out in the canonical (NVT) ensemble with a Langevin thermostat to control temperature. The Langevin friction coefficient for the atomic degrees-of-freedom was set to 100 ps−1. The timestep was set to 0.5 fs, and the initial structures were equilibrated at room temperature for 4 ps. The trajectories of the total supercell energy and pressure were analysed as a function of time to ensure that an equilibrated state had been reached, and each of these quantities was oscillating around a given value. While the temperature of interest is room temperature, it has been shown that increasing the equilibration temperature in water by 30 K mimics nuclear quantum effects (NQEs)56. Thus, all calculations were performed at 328 K. The density of water was determined by varying the volume of the supercell, calculating the pressure at each individual volume, fitting a second-order polynomial to the pressure versus volume curve, and identifying the volume at which the pressure is zero. Three simulations were performed at each specified volume, and the system was evolved for 2000 timesteps with a timestep of 1 fs. This method yielded a density of 1.07 g/cm3, which is within 2% of the previously reported value from the SCAN XC potential48.

Given this density prediction, a single O atom was inserted into the supercell and equilibrated for 5 ps using the above simulation conditions. Subsequently, diffusion calculations were performed in which the system was evolved for 20,000 steps with a timestep of 1 fs, for a total system time of 20 ps. Ten unique simulations were conducted to gain statistical significance in the results. The mean-squared displacement (msd) and the displacement were determined for the total system, H atoms, O atoms, and the free O atom. This allowed for the determination of both the velocity and the diffusion coefficient. The diffusion coefficient was fit to the msd as a function of time per Einstein’s equation (D = r2/2dt), where d is the number of dimensions, which in this case is three. The velocity is taken as the linear fit to the displacement as a function of time. The first 1 ps was neglected in the determination of the slope of displacements versus time.

Although ten unique simulations were included for the mean-squared displacement as a function of time for an O atom in water at 328 K, there is uncertainty in the data that increases with time. However, a linear trend is observed (R2 = 0.96), indicating reasonably converged diffusive behaviour.

The velocity derived from this set of trajectories was determined to be 2399.5 cm/s, and the diffusion coefficient was calculated as 1.5 × 10−9 m2/s. There are no prior experimental or computational data available for comparison. Using this velocity, the experimental density of water, and the assumed collisional cross section of O, the collisional frequency can be estimated. This method predicts a collisional frequency of 1.45 × 1011 collisions per second. If it is assumed that all collisions result in quenching of the laser-excited state, the effective radiative lifetime of Oaq is 6.9 ps. This is approximately three orders of magnitude lower than the effective lifetime of laser-excited O atoms in the plasma effluent. Uncertainties associated with the prediction of the collisional frequency include the collisional cross section for monatomic O in water and the velocity of O in water determined by AIMD.

Data availability

The experimental data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under the accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15984980.

References

Graves, D. B. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 45, 263001 (2012).

Lu, X. et al. Reactive species in non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasmas: Generation, transport, and biological effects. Phys. Rep. 630, 1–84 (2016).

Hefny, M. M., Nečas, D., Zajíčková, L. & Benedikt, J. The transport and surface reactivity of O atoms during the atmospheric plasma etching of hydrogenated amorphous carbon films. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 28, 035010 (2019).

Korang, J. et al. Photoinduced DNA cleavage by atomic oxygen precursors in aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 3, 12390–12397 (2013).

Marsh, H., O’Hair, E., Reed, R. & Wynne-Jones, W. F. K. Reaction of atomic oxygen with carbon. Nature 198, 1195–1196 (1963).

Bekeschus, S. et al. Oxygen atoms are critical in rendering THP-1 leukaemia cells susceptible to cold physical plasma-induced apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 2791–12 (2017).

Zhang, X., Li, M., Zhou, R., Feng, K. & Yang, S. Ablation of liver cancer cells in vitro by a plasma needle. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 021502 (2008).

Kim, C. H. et al. Effects of atmospheric nonthermal plasma on invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 243701 (2010).

Benedikt, J. et al. The fate of plasma-generated oxygen atoms in aqueous solutions: Non-equilibrium atmospheric pressure plasmas as an efficient source of atomic O(aq). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 12037–12042 (2018).

Hefny, M. M., Pattyn, C., Lukes, P. & Benedikt, J. Atmospheric plasma generates oxygen atoms as oxidizing species in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 404002 (2016).

Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as a solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4399–4981 (2015).

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NDRL/NIST Solution Kinetics Database, [Online]. Available: https://kinetics.nist.gov/solution/. National institute of standards and technology, Gaithersburg, MD. (2002).

Myers, B. et al. Measuring plasma-generated .OH and O atoms in liquid using EPR spectroscopy and the non-selectivity of the HTA assay. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 145202 (2021).

Gorbanev, Y., Stehling, N., O’Connell, D. & Chechik, V. Reactions of nitroxide radicals in aqueous solutions exposed to non-thermal plasma: limitations of spin trapping of the plasma induced species. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 25, 055017 (2016).

Elg, D. T., Yang, I. & Graves, D. B. Production of TEMPO by O atoms in atmospheric pressure non-thermal plasma-liquid interactions. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 475201 (2017).

Bischel, W. K., Perry, B. E. & Crosley, D. R. Two-photon laser-induced fluorescence in oxygen and nitrogen atoms. Chem. Phys. Lett. 82, 85–88 (1981).

Schmidt, J. B., Sands, B., Scofield, J., Gord, J. R. & Roy, S. Comparison of femtosecond- and nanosecond-two-photon-absorption laser-induced fluorescence (TALIF) of atomic oxygen in atmospheric-pressure plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 26, 055004 (2017).

Wagenaars, E., Gans, T., O’Connell, D. & Niemi, K. Two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence measurements of atomic nitrogen in a radio-frequency atmospheric-pressure plasma jet. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 21, 042002 (2012).

Dogariu, A. et al. A diagnostic to measure neutral-atom density in fusion-research plasmas. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 93, 093519 (2022).

Schröter, S. et al. The formation of atomic oxygen and hydrogen in atmospheric pressure plasmas containing humidity: Picosecond two-photon absorption laser induced fluorescence and numerical simulations. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 29, 105001 (2020).

Niemi, K., Schulz-von der Gathen, V. & Döbele, H. F. Absolute atomic oxygen density measurements by two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy in an RF-excited atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 14, 375–386 (2005).

Golda, J. et al. Concepts and characteristics of the ’COST reference microplasma jet’. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 84003 (2016).

Gorbanev, Y., Golda, J., Schulz-von der Gathen, V. & Bogaerts, A. applications of the COST plasma jet: more than a reference standard. Plasma 2, 316–327 (2019).

Riedel, F. et al. Reproducibility of ‘COST reference microplasma jets’. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 29, 095018 (2020).

Ellerweg, D., Benedikt, J., von Keudell, A., Knake, N. & Schulz-von der Gathen, V. Characterization of the effluent of a He/O2 microscale atmospheric pressure plasma jet by quantitative molecular beam mass spectrometry. N. J. Phys. 12, 013021 (2010).

Niemi, K., Waskoenig, J., Sadeghi, N., Gans, T. & O’Connell, D. The role of helium metastable states in radio-frequency driven helium-oxygen atmospheric pressure plasma jets: measurement and numerical simulation. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 20, 055005 (2011).

Sgonina, K., Bruno, G., Wyprich, S., Wende, K. & Benedikt, J. Reactions of plasma-generated atomic oxygen at the surface of aqueous phenol solution: experimental and modeling study. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 043303 (2021).

Byrom, L. & Dogariu, A. Classification of quenching regimes in laser-induced fluorescence imaging of radical species. In: Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (2025).

Myers, B., Barnat, E. V. & Stapelmann, K. Atomic oxygen density determination in the effluent of the COST reference source using in situ effective lifetime measurements in the presence of a liquid interface. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 455202 (2021).

Codorniu-Hernández, E. et al. Mechanism of O(3P) formation from a hydroxyl radical pair in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 4740–4748 (2015).

Verlackt, C. C., Neyts, E. C. & Bogaerts, A. Atomic scale behavior of oxygen-based radicals in water. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 11LT01 (2017).

Kläning, U. K., Sehested, K. & Wolff, T. Ozone formation in laser flash photolysis of oxoacids and oxoanions of chlorine and bromine. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1: Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 80, 2969–2979 (1984).

Lietz, A. M. & Kushner, M. J. Air plasma treatment of liquid covered tissue: long timescale chemistry. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 425204 (2016).

Verlackt, C. C. W., Boxem, W. V. & Bogaerts, A. Transport and accumulation of plasma generated species in aqueous solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 6845–6859 (2018).

Heirman, P., Boxem, W. V. & Bogaerts, A. Reactivity and stability of plasma-generated oxygen and nitrogen species in buffered water solution: a computational study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 12881–12894 (2019).

Kramida, A., Ralchenko, Y., Reader, J. & NIST ASD Team. NIST atomic spectra database (ver. 5.8), [Online]. Available: https://physics.nist.gov/asd. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD. (2020).

van Gessel, A. F. H., van Grootel, S. C. & Bruggeman, P. J. Atomic oxygen TALIF measurements in an atmospheric-pressure microwave plasma jet with in situ xenon calibration. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 22, 055010 (2013).

Goehlich, A., Kawetzki, T. & Döbele, H. F. On absolute calibration with xenon of laser diagnostic methods based on two-photon absorption. J. Chem. Phys. 108, 9362–9370 (1998).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Mason, J., Cone, M. & Fry, E. Ultraviolet (250–550 nm) absorption spectrum of pure water. Appl. Opt. 55, 7163–7172 (2016).

Scarborough, T. D., Petersen, C. & Uiterwaal, C. J. G. J. Measurements of the GVD of water and methanol and laser pulse characterization using direct imaging methods. N. J. Phys. 10, 103011 (2008).

Coello, Y., Xu, B., Miller, T. L., Lozovoy, V. V. & Dantus, M. Group-velocity dispersion measurements of water, seawater, and ocular components using multiphoton intrapulse interference phase scan. Appl. Opt. 46, 8394 (2007).

Tilton, L. W. Accurate representation of refractive index of distilled water as a function of wavelength. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 17, 639–650 (1936).

Smirnov, B. M., Son, E. E. & Tereshonok, D. V. Diffusion and mobility of atomic particles in liquid. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 125, 906–912 (2017).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Chen, M. et al. Ab initio theory and modeling of water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 10846–10851 (2017).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Morrone, J. A. & Car, R. Nuclear quantum effects in water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 017801 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This material is based partly upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences Opportunities in Frontier Plasma Science programme under award number DE-SC-0021329 (K.S.), and partly based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant Nos. PHY-2308857 (K.S.) and PHY-2308859 (A.D.). Part of this research used resources of the Princeton Collaborative Low Temperature Plasma Research Facility (PCRF), which is supported by the DOE Office of Science, Fusion Energy Sciences, and managed by the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. This research made use of the resources of the High-Performance Computing Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under Contract No. DE-AC07-05ID14517 (B.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D., S.Y. and K.S. conceived of the research. B.M., A.D., and L.B. performed the experiments. B.M., A.D. and L.B. analysed and visualised the data. B.B. performed the molecular dynamics simulations. K.S. acquired funding for the project. B.M. wrote the original manuscript, and all authors participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, B., Dogariu, A., Beeler, B. et al. Imaging solvated oxygen atoms with a femtosecond laser. Nat Commun 16, 11393 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66196-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66196-8