Abstract

Millennial-scale climate cycles persist throughout greenhouse climates, yet the mechanisms remain unclear. Here, using proxy reconstructions, we present centennial-resolution geological records from early Campanian greenhouse deposits in both mid-latitude East Asia and low-latitude Southern Atlantic. These records document pronounced millennial ( ~ 1–6 kyr) wet-dry climate cycles. The amplitude modulation relationship between the most prominent ~4–5-kyr cycles (corresponding to the ¼ precession cycle) and eccentricity aligns perfectly with the theoretically calculated equatorial insolation cycles, demonstrating the climate effect of this predicted insolation forcing on global climate. Other millennial cycles primarily emerge from these ~4–5-kyr cycles via nonlinear amplitude modulation and combination tones. Proxy reconstructions and theoretical calculation thus converge to demonstrate that during this warm greenhouse period, precession can directly and indirectly stimulate millennial climate cycles. The deterministic link between astronomical parameters and millennial climate cycles implies that high-frequency climate oscillations may be predictable in future greenhouse-like climates, particularly under anthropogenic warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

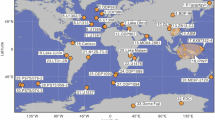

Earth’s climate has oscillated across multiple timescales1, from multimillion-year icehouse-greenhouse transitions to orbital-scale glacial-interglacial cycles. Superimposed on these gradual changes are abrupt millennial-scale climate cycles (1–10 kyr), demonstrating inherent climate instability. The most well-documented examples of millennial climate variabilities are the Pleistocene Dansgaard-Oeschger2 and Heinrich events3, manifested as abrupt temperature increases in Greenland and episodic iceberg discharges in the North Atlantic. These events were described within the context of the Quaternary icehouse world, especially during glacials, and they are thus mostly linked to cryospheric dynamics such as ice-sheet oscillations and concomitant ocean circulation shifts4. In the last decades, emerging evidence reveals that high-frequency climate oscillations persisted even during ancient greenhouses world5,6,7,8,9 (Fig. 1). In greenhouse climates, where polar ice sheets are minimal or absent, the generation of millennial climate cycles is hypothesized to arise from different mechanisms, including millennial shifts in monsoon intensity6,10 and oceanic redox conditions9, and nonlinear response to orbital forcing5,8. A key unresolved question is whether astronomical forcing can directly excite millennial climate cycles under such warm ice-free backgrounds. Theoretical models posit that the climate response to the largest amplitude of the seasonal cycle of insolation at the equator due to precession (equatorial insolation) could trigger millennial climate cycles, especially at ~5 kyr11. Yet empirical validation has been hindered by the paucity of well-dated, high-resolution paleoclimate datasets from deep-past greenhouse stages. Quaternary archives, while temporally precise, conflate millennial cycles caused by this theoretical insolation forcing with those triggered by ice dynamics (e.g., Heinrich events)3,11.

A Modern geographic location of records which preserved millennial-scale climate cycles throughout the Mesozoic and Paleozoic Eras, and of study sites related in this study. The detailed information of these records, including paleogeographic locations and chronologies, are compiled in Table S1. The world map was generated using the geom_map function in the R package ggplot270. B The latitudinal extent of continental ice sheets, excluding Alpine glaciers71. C The temporal distribution of millennial-scale climate cycles reported throughout the Mesozoic and Paleozoic Eras.

The early Late Cretaceous exemplifies a greenhouse climate12,13, offering an ideal candidate to study climate dynamics in warm, high-CO2 regimes. The Songliao Basin (SLB) in East Asia presents a unique opportunity for high-resolution analysis, with nearly the entire Late-Cretaceous terrestrial strata recovered during the International Continental Scientific Drilling Project14. Here, we target the early Campanian (83.428–83.538 Ma) deep-lacustrine rhythmic deposits of the lower Nenjiang Formation (K2n1+2; 1137.84–1145.2 m interval) from the SK2 borehole of the basin (46°14′26.89″N, 125°21′47.03″E) (Figs. 1, S1). The rhythmic deposition is primarily characterized by alternating black siliceous mudstone/shale and gray laminated calcareous mudstone (Fig. S2). This stratigraphic interval was selected because the strata were deposited in a geological setting (deep-lacustrine environment) where autogenic noise in the ‘source-to-sink system’ is expected to be minimal15, and its finer-grained mudstones better preserve allogenic signals than coarser deposits16. To quantify this rhythm, we present centennial-resolution ( ~ 1-cm stratigraphic spacing; ~0.14-kyr temporal spacing) grayscale and X-ray fluorescence (XRF)-derived element ratios, Rb/Sr and log (Ca/Ti) (Fig. 2, S1). Grayscale effectively captures lithological variation, with higher values indicating greater carbonate content and lower values reflecting enrichment in organic-rich siliceous sediments (Figs. S1, S2). Rb/Sr tracks chemical weathering intensity, since Rb is relatively immobile, whereas Sr is readily leached during weathering17; higher Rb/Sr values thus reflect stronger weathering18,19. Ca content primarily reflects carbonate deposition (Fig. S2), which tends to be chemically precipitated in shallow lakes under arid conditions, while Ti represents terrigenous clay input to deeper lakes and is resistant to diagenesis20. Accordingly, the Ca/Ti is a proxy for lacustrine salinity and lake levels, with higher values signifying a more arid climate and lower lake levels19,20,21.

Moreover, previous studies of coeval low-latitude South Atlantic marine successions recovered from the DSDP–516 F borehole (30°16′35.4″S, 35°17′6″W; paleolatitude ~25 °S) during Leg 72 (Fig. 1) revealed semi-precessional and millennial climate cycles7,22. However, these analyses were conducted on the stratigraphic domain with poor chronological constraints. Thus, for a comparable analysis from a marine setting, a high-quality and high-resolution color reflectance (L*) ( ~ 1.5-cm stratigraphic spacing; ~0.63-kyr temporal spacing) from this core (80.702–81.472 Ma)7 was reinvestigated after refining its chronology using magnetostratigraphy23 and cyclostratigraphy (Fig. 2, Figs. S3, S4; see “Methods”). By synthesizing these terrestrial-marine datasets, we aim to identify significant millennial climate cycles in different deposition settings of the greenhouse period, investigate their mechanisms, and explore their climate implications.

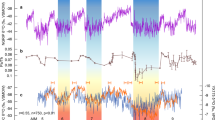

A–C Grayscale, log (Ca/Ti), and Rb/Sr datasets from the SK2 borehole with their ~95.2-kyr (0.0105 ± 0.0035 cycle/kyr), ~22-kyr (0.0455 ± 0.0095 cycle/kyr), and ~4–5-kyr (0.215 ± 0.055 cycle/kyr) filters. D The astronomically-tuned L* datasets (blue) based on TimeOpt chronology (Fig. S4) and anchoring to the magnetostratigraphic age at 1145.132 m (80.702 Ma), with precessional filters (0.054 ± 0.011 cycles/kyr). E The evolutive power spectra of L* using the EHA method62, with ~405-kyr filter of tuned L*. F The selected intervals of tuned L* showing quadripartite structure, in which every precession cycle (0.054 ± 0.011 cycles/kyr) includes two semi-precessional (0.1 ± 0.02 cycle/kyr) and four quarter-precessional (0.215 ± 0.055 cycle/kyr) cycles. The quarter-precessional cycles in L* are most prominent at peaks of the 405-kyr filter of L*, indicating an intermodulation relationship between quarter-precessional cycles and long eccentricity.

Results

Millennial cycles in Cretaceous East Asia

In the depth domain, the grayscale, Rb/Sr and log (Ca/Ti) ratios in SK2 core all display prominent cyclicities with ~0.12–0.52-m cycles. On this timescale, three datasets are phase-coupled with larger grayscale correlating with lower Rb/Sr and higher log (Ca/Ti) (Fig. S1D). An anchored astronomical time scale (ATS) for the K2n1+2 interval of the core, derived from radiometric zircon dating of four bentonite layers and cyclostratigraphic intercorrelations across three boreholes in the SLB24, constrains a sediment accumulation rate (SAR) of ∼6.36 cm/kyr (Fig. S1). With this SAR constraint, the observed cycles correspond to periodicities of ~1.88–8.13 kyr. Using the anchored ATS24, we converted stratigraphic datasets to the time domain (83.428–83.538 Ma) (see Chronology in the “Methods”), revealing distinct cyclic patterns (Fig. 2A–C).

Spectral analysis indicates that both ~100-kyr and ~22-kyr power peaks are prominent in three datasets. The ~100-kyr power peaks in grayscale and the ~22-kyr peaks in log (Ca/Ti) display low confidence levels; nevertheless, both signals are significant in the Rb/Sr datasets (exceeding the 95% confidence level in ML96 robust AR1 model) (Figs. 3A, B, S5). Despite the total length of the datasets being ~110 kyr, the trend of ~100-kyr cycle remains evident (Figs. 2B, C, S6). Besides, the ~100-kyr and ~20-kyr filters in three datasets are phase-coupled (Fig. S6).

A Periodogram power spectra (upper panel) and p-values for the null hypothesis (middle panel), as well as the bicoherence spectra (bottom panel) of grayscale datasets from the SK2 borehole. B, C Same as (A) but for log (Ca/Ti) from the SK2 borehole and L* datasets from the DSDP–16 F borehole. The bicoherence spectral analysis uses four segments with 50% overlap and a Hanning taper. Thick black contours highlight bicoherence results exceeding the 95% confidence level. Because the FDR-corrected p-values for the power peaks at ~1.8–2.5 kyr in Rb/Sr are larger than 0.2, the Rb/Sr bicoherence plot is shown in Fig. S5 instead.

Higher-frequency millennial signals are also prominent in grayscale, with strong spectral peaks at ~5.8 kyr, ~4.5 kyr, ~3.7 kyr, moderate peaks at ~2.6 kyr, ~2.3 kyr, ~1.8 kyr, and weak signals at ~1.2–1.1 kyr (Fig. 3A). Similar millennial cycles occur in log (Ca/Ti), with strong peaks at ~5.7 kyr, ~4.4 kyr, ~3.6 kyr, and moderate peaks at ~2.5 kyr, ~2.0 kyr, ~1.8 kyr, ~1.7 kyr, and weak peaks at ~1.3–1.0 kyr (Fig. 3B). Rb/Sr retains significant millennial cycles only at ~5.8 kyr, ~4.5 kyr, ~3.7 kyr (Fig. S5). All of these peaks surpass 95% confidence levels in both conventional and ML96 robust AR1 models. Moreover, noise model tests using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach25,26 reveal test p-values below 0.05 for these peaks (see “Methods”) (Fig. 3 A, B; Fig. S5), confirming their statistical significance.

Millennial cycles in Cretaceous South Atlantic

Magnetostratigraphic analysis indicates that the interval of DSDP–516 F core between 1125.68 and 1198.44 m corresponds to magnetochron C33r23. This depth-age model yields an average SAR of 2.43 cm/kyr based on the geomagnetic polarity time scale 2020 (GPST 2020) chronology27 (Fig. S3). Under the first-order constraint of this SAR, a floating ATS was established for the L* dataset from 1163.42 to 1145.132 m of the core7 with the TimeOpt algorithm28 (see “Methods”). The acquired floating ATS returns an optimal SAR of 2.37 cm/kyr (Fig. S4) and was anchored at 80.702 Ma, the linearly-interpolated magnetochronology at 1145.132 m. The anchored ATS converts the stratigraphic L* into a continuous time interval of 81.473–80.702 Ma (see Chronology in the Methods for more details).

Spectral analysis of the tuned L* reveals significant power peaks at ~405 kyr, ~107 kyr, ~22.7 kyr, ~18.2 kyr, ~11.3 kyr, ~9.2 kyr, ~5.5 kyr, ~4.8 kyr, and ~4.1 kyr (Figs. 2D–F, 3C). All of these peaks exceed the 90% confidence level in the conventional AR1 model and the 95% confidence level in the ML96 robust AR1 model. Moreover, moderate power peaks at ~1.4 kyr and ~1.3 kyr are also significant (above 95% confidence level of both conventional and ML96 model, the multiple test p-values smaller than 0.1). The test p-values for the power peaks at ~405 kyr, ~22.7 kyr, ~18.2 kyr, ~4.1 kyr are below 0.1 (Fig. 3C). Although the p-values for the peaks at ~11.3 kyr, 9.2 kyr, 5.5 kyr, 4.8 kyr are above 0.1, the tuned L* data clearly show a semipartite and quadripartite structure of precession-related cycles, with each precession cycle comprising two semi-precessional and four quarter-precessional cycles (Fig. 2F). Moreover, the evolutionary correlation coefficients between L* and its ~10-kyr filter (0.095 ± 0.025 cycles/kyr) and between L* and its ~4–5-kyr filter (0.215 ± 0.055 cycles/kyr) display significant eccentricity signals that are phase-locked with the eccentricity in L* datasets (Fig. S7).

Discussions

Orbital and semi-precessional cycles

At 83 Ma, the astronomical cycles of eccentricity and precession exhibit periodicities of ~405 kyr, ~125 kyr, ~95 kyr, ~22.7 kyr, ~21.5 kyr, and ~18.5 kyr29,30. Consequently, power peaks observed in the datasets at ~405 kyr, ~107 kyr, ~100 kyr, ~22.7 kyr, ~22.0 kyr, and ~18.2 kyr can be interpreted as representing long eccentricity, short eccentricity, and precession cycles. Although the ~100-kyr and ~22-kyr signals in grayscale, log (Ca/Ti), and Rb/Sr show different confidence levels, the ~100-kyr and ~20-kyr filters across these datasets are phase-coupled with each other (Fig. S6A, D, G), substantiating their authenticity. This differential expression likely reflects differences in proxy sensitivity to different insolation forcings; for example, local insolation is dominated by precession peaks, whereas tropical insolation is dominated by eccentricity cycles11.

Besides, the distinct ~9.2–11.3-kyr signals were recognized in the L* record of DSDP–516 F core, aligning with semi-precessional cycles regarding the periodicities. Semi-precessional cycles are associated with the biannual responses of the intertropical climate to insolation maxima11,22,31,32, involving equatorial maximum insolation and bi-hemisphere maximum insolation11,31,33,34. Equatorial maximum insolation drives climate responses to insolation peaks at both spring and fall equinoxes31,33 (Fig. 4B), typically manifesting as biannual monsoon rainfall maxima in low latitudes6,35. Bi-hemisphere maximum insolation corresponds to climate responses to insolation maxima at both hemispheric summer solstices32,34,36 (Fig. 4B). Convergent circulations along the ocean subsurface at certain depths, e.g., thermohaline, can transport bi-hemispheric summer insolation maxima to the equatorial area, leading to a double response to summer solstices within a precession cycle34,37.

Notably, simple clipping of precession can also produce prominent semi-precessional power peaks in the corresponding spectra; however, the resulting semi-precessional cycle is not a true single and is identified as a spectral artifact32. In the contrary, the comparison of L* with its ~10-kyr filter reveals a clear semipartite structure, with each precession cycle comprising two semi-precessional cycles (Fig. 2F). Moreover, the ~10-kyr variance in L* is high ( > 50%) during intervals when eccentricity is above its average value (Fig. S7). These findings demonstrate the significance of the semi-precessional cycles in L* datasets. Thus, the observed semi-precessional cycles cannot be attributed to precession clipping.

Direct precessional origin of millennial cycles

Here, except for semi-precessional cycles, distinct millennial-scale climate cycles with periodicities of 1–6 kyr are identified in both terrestrial and marine records during the early Campanian. The null hypothesis of stochastic variability and associated testing p-values confirm their statistical confidence (Fig. 3). Researches on millennial-scale climate cycles has long focused on those occurring during the Quaternary icehouse stage, generally attributing them to ice sheet-related dynamics4. However, the Cretaceous represents one of the classical greenhouse climate periods in Earth’s history12,13. The presence of millennial cycles in this ice-free world reinforces that high-frequency climate variabilities are not exclusive to the Quaternary glacial age (but are inherent to Earth’s climate system) and are not solely driven by ice-related dynamics.

In the SK2 datasets, the strongest millennial cycles are centered around 4–5 kyr (Fig. 2 & 3). On this timescale, grayscale, log (Ca/Ti), and Rb/Sr ratios from the SK2 borehole exhibit strong phase coupling with the higher grayscale and log (Ca/Ti) values corresponding to lower Rb/Sr ratios, and vice versa (Fig. 2A–C). Moreover, the petrographic and mineralogical investigations indicate that the intervals with high grayscale and log (Ca/Ti) but low Rb/Sr are associated with gray laminated mudstones rich in calcites of microcrystalline and micritic forms (Fig. S2). In contrast, intervals with low grayscale and log (Ca/Ti) but high Rb/Sr correspond to black mudstones dominated by quartz (Fig. S2). This 4–5-kyr rhythmic alternation between gray laminated calcareous and black siliceous mudstones reflects millennial-scale arid-humid variability. This is because during humid periods, enhanced terrestrial precipitation intensified chemical weathering and raised lake levels, producing higher Rb/Sr and lower log (Ca/Ti). Increased runoff also delivered organic matter and nutrients into the lake, promoting organic-rich shales and lowering grayscale values. Conversely, during arid phases, reduced precipitation lowered weathering intensity and increased lacustrine salinity, favoring chemical precipitation of carbonate, thus with higher log (Ca/Ti) and grayscale values but lower Rb/Sr.

Similar periodicities ( ~ 4.8 kyr) are also evident in the L* datasets from DSDP–516 F (Figs. 2D–F, 3C). The occurrence of these millennial cycles in both marine and terrestrial successions across hemispheres suggests that the ~4–5-kyr cycles should result from external forcing and highlights the pronounced climate instability during this greenhouse period. Detailed demodulation of the ~4–5-kyr cycles in the datasets reveals significant amplitude modulation (AM) that is phase-locked with eccentricity cycles (~100 kyr; ~405 kyr) (Fig. S6). Despite the SK2 datasets covering only ~110 kyr, the ~100-kyr modulation of the ~4–5-kyr cycles remains evident (Fig. S6A–H). These ~4–5-kyr cycles, occurring with an eccentricity envelope, resemble the theoretically-calculated equatorial insolation11.

The equatorial insolation, defined as the largest amplitude of the seasonal cycle of mean irradiance at the equator, is estimated from the difference between mean irradiance at the equinoxes (spring and fall) and at the solstices (summer and winter)11 (Fig. 4A). Theoretically, when climate system is driven by the equatorial insolation, a ~ 5-kyr quarter-precessional cycles would be generated, and the amplitude of these cycles would then be modulated by eccentricity11. Previously, a ~ 5-kyr signal was detected in the Late-Permian equatorial laminated evaporites5, Early-Cretaceous black shale of the western Tethys38, and Quaternary ice-core records of both Greenland and Antarctica39, but lacking mechanism interpretations. Here, our unprecedented Cretaceous datasets, especially those from the SLB, align perfectly with this theoretically-proposed equatorial insolation curve in terms of both periodicity and intermodulation structure (Figs. 2, 4A, C, S6). Thus, our geological reconstructions validate the climate effects of this predicted tropical isolation. Given that equatorial insolation inherently produces 4–5 kyr periodic forcing, the persistent manifestation of such signals in geological archives becomes self-evident.

A The theoretically-proposed largest equatorial seasonal insolation amplitude (termed equatorial insolation). The insolation amplitude is estimated from the differences between the two insolation maxima at spring and fall equinoxes and the two insolation minima at summer and winter solstices, that is, max (SE, FE)-min (SS, WS), where SE, FE, SS, WS denote the spring equinox, fall equinox, summer solstice, winter solstice, respectively11. B The combined effect of equatorial and bi-hemisphere maximum insolation. C The log (Ca/Ti) in the SK2 of SLB. D The periodogram spectra of equatorial insolation. E The periodogram spectra of the combined effect of equatorial and bi-hemisphere maximum insolation at 8 °N/S.

Equatorial insolation essentially reflects the climate response to the largest seasonal amplitude, which coincides with precession-induced insolation maxima at the equator during the two equinoxes and two solstices11. Thus, at least two extra mechanisms could interpret the 4–5-kyr cycles. First, we propose that a climate response to both equatorial and bi-hemisphere maximum insolation could also generate climate cycles analogous to those driven by equatorial insolation, though with opposing climate effects (Fig. 4B). This scenario requires bi-hemisphere maximum insolation at specific latitudes (e.g., ~8°N/S), as at much higher (e.g., 20°N/S) or lower latitudes (e.g., equator), bi-hemisphere maximum insolation is either too strong or too weak to overlap with equatorial maximum insolation (Fig. 4B).

Secondly, the climate system is complex; its changes are influenced not only by external forcing but also internal feedbacks40. Transient simulations show that the alternating presence of trees and deserts causes a decrease in the grass fraction during both precession minima and maxima in the African and Asian monsoon regions41. This results in a twice-per-cycle response of grassland areas to precession, producing semi-precessional cycles. Thus, we propose an analogous mechanism, but with forcing originating from equatorial or bi-hemisphere maximum insolation. Accordingly, the twice-per-cycle response of climate components to either equatorial or bi-hemisphere maximum insolation can also induce oscillations similar to those triggered by equatorial insolation, or by the combined effects of equatorial and bi-hemisphere maximum insolation. Regardless of the specific climate process responsible for quarter-precessional cycles, orbital precession, interacting with complex internal feedback, can directly stimulate millennial-scale climate cycles at ~5 kyr.

Indirect precessional origin of millennial cycles

Besides the most prominent ~4–5-kyr cycles, there are two millennial-scale peaks at 1/3.7 (1/3.6) kyr−1, and 1/5.7 (1/5.8) kyr−1 in datasets of the SLB, which bracket the quarter-precessional cycles at 1/4.5 kyr−1 (Figs. 3A, B, S5). These two power peaks can be interpreted as the consequence of amplitude modulation between precession and quarter-precessional cycles. This is because the amplitudes of the ~4–5-kyr cycles are also modulated by the ~22-kyr precession cycle (Fig. S6). According to the amplitude modulation mechanism, two sidebands should form around the ~4.5-kyr peaks: the combination tone (4/18 + 1/22 = 1/3.7) and difference tone (4/18 − 1/22 = 1/5.7) between the modulator (1/22) and carrier (4/18). This interpretation is underpinned by the bicoherence analysis of the grayscale data, which reveals strong coherence at the triad point (1/5.8, 1/22, 1/4.5) in the bicoherence plot (Fig. 3A). However, the ~5.5-kyr signals in the L* may instead reflect the third harmonic of the ~18.2-kyr precessional cycles, as indicated by the triad point (1/9.2, 1/18.2, 1/6.1) in the bicoherence plot (Fig. 3C). Alternatively, they could also arise from the fourth harmonic of the ~22.7-kyr precessional cycles, since 4/22.7 = 1/5.7.

Bicoherence spectra further reveal that the moderate millennial cycles at ~2.6 kyr, ~2.3 kyr, ~2.0 kyr, ~1.8 kyr correspond to the combination tones of precession-related lower-frequent millennial cycles (Fig. 3, S5). For instance, the ~2.6-kyr cycles result from the combination of frequencies at ~1/4.5 kyr−1 and ~1/5.8 kyr−1 (1/2.6 = 1/4.5 + 1/5.8). Similarly, 1/2.3 = 1/4.5 + 1/4.5, 1/2.0 = 1/3.6 + 1/4.4, 1/1.8 = 1/3.6 + 1/3.6. Thus, the cycles below 1/1.8 kyr−1 in this greenhouse period likely stem from the precession harmonics and their high-order nonlinear combination tones.

The millennial-scale power observed between 1/1 kyr−1 and 1/1.7 kyr−1 does not correspond to known astronomical cycles or nonlinear combination tones (Fig. 3). Such high-frequency signals are often affected by bioturbation42. Given the low SAR at DSDP–516 F in the North Atlantic, our bioturbation simulations, based on typical sediment mixing depths of 5–10 cm in the ocean, suggest that these cycles in L* datasets may be entirely smoothed (Fig. S8A). Thus, caution is warranted when interpreting these millennial cycles in the L* record of DSDP–516 F. By contrast, the higher SAR and sampling resolution of the records in the SLB allow millennial cycles, including those at ~1.25 kyr, to be clearly identified (Fig. S8B). Furthermore, the well development of laminations throughout the study interval of SK2 (Figs. S1, 2) indicates minimal mixing by bioturbation, supporting the preservation of such cycles in the SLB, which may reflect a climate response to external forcing such as solar activities43. Nevertheless, the spectral variances in the ~1–1.7 kyr bands is negligible in both SK2 and DSDP–516 F, with most millennial-scale variance resided in the ~1.8–6-kyr band and attributable to the climate response to precession.

Tropical forcing of mid-high latitude climate

The variance of the quarter-precessional cycles in equatorial insolation weakens rapidly with distance from the equator (Fig. S9), indicating a low-latitude origin for these cycles11. This explains their frequent occurrence in low-latitude, monsoon-dominated regions5,32,38. The paleolatitude of the SLB is ~45°N, suggesting that the quarter-precessional signals were transmitted to mid-latitudes via oceanic-atmospheric teleconnections originating at low latitudes, such as paleo-El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events44,45 or monsoon-like systems. Late-Cretaceous ENSO-like variability has also been reported in mid latitudes and even the Arctic46,47, likely transmitted from equatorial latitudes via stratospheric teleconnections47. Although the SLB is a terrestrial basin, multiple lines of evidence, including marine biomarkers48, rhenium-platinum group elements49, and the presence of marine foraminifera50, suggest possible intermittent marine connectivity during deposition, potentially enabling ocean-mediated signal transmission into the basin. Thus, similar to the Pleistocene semi-precessional climate scenario, we posit that the quarter-precessional cycles observed in the SLB most likely result from tropical processes31,32, with the low-latitude response to the equatorial insolation being transmitted to the mid- and high-latitudes via oceanic-atmospheric teleconnections. Further investigation of these teleconnections could be advanced through climate model simulations.

The Cretaceous exemplifies a high-CO₂ greenhouse regime, with atmospheric CO2 concentrations reaching ~1000 ppm during Campanian51. Future carbon emission scenarios project atmospheric CO₂ levels approaching 800 ppm by 210052, comparable to Campanian baselines. CO2-induced greenhouse forcing is regarded as the principal driver of Earth’s warming. Thus, such a trajectory suggests Earth’s climate system may re-enter a sustained greenhouse state51. Here, our proxy reconstructions show that the greenhouse Cretaceous climate displays prominent instability, exhibiting millennial arid-humid climate cycles ( ~ 1–6 kyr). Most of the variance in these millennial-scale cycles can be attributed to precession-induced insolation forcing, both directly and indirectly, via the tropical insolation mechanism. The Earth’s orbit is estimated to remain highly stable for billions of years in the future53. Thus, the close link between astronomical precession and millennial cycles implies that high-frequency climate oscillations, analogous to those of the Cretaceous, could reoccur and be predictable in future warming scenarios, particularly in the context of anthropogenic warming.

Methods

Materials from the East Asia (SK2 borehole)

The Songliao Basin (SLB) is one of the largest Mesozoic terrestrial inland basins, with its paleogeographical location being located at ∼45°N during the Cretaceous14. Under the scheme of the International Continental Scientific Drilling Project of Cretaceous Songliao Basin, the SK2 borehole (125°21′47.03″ E, 46°14′26.89″ N) was drilled in the basin to recover the successions, including early Mesozoic to Paleozoic basement, Early Cretaceous strata, and part of Late Cretaceous strata. Of these strata, the Santonian-Campanian lower Nenjiang Formation, including the first and second Member of the Nenjiang Formation (K2n1+2) (correlating to the interval of 1249.32–1145.23 m and 1145.23–1086 m in the SK2 core, respectively), was a set of deep-lacustrine successions, characterized by black mudstones with intercalations of thin carbonate layers, black shales, oil shales, fine sandstones, and bentonites54 (Fig. S1A). These successions were proven to preserve the paleoclimate information, including the contemporary humid/arid climate perturbations and astronomical signals19,24. Especially, the lowest part of the second member of Nenjiang Formation (K2n2) (1145.2–1137.84 m), deposited in the early Campanian24,55 when polar areas were devoid of major glaciation13, consists largely of alternating gray calcareous and black siliceous mudstones (Fig. S1C; Fig. S2). Thus, here we selected this interval as researching materials.

Materials from the South Atlantic (DSDP–516 F borehole)

Borehole DSDP–516 F, drilled on the Rio Grande Rise in the South Atlantic (30°16.59′S, 35°17.1′W) during Leg 72, was designed to acquire the Neogene-Late Cretaceous successions with the purpose of decoding the coeval paleoecologic characteristics of the southwestern Atlantic56. The Rio Grande Rise was located at ~25°S during 84 Ma57. Part of the early-Campanian interval of DSDP–516 F has been subjected to high-resolution climate analysis. Park et al.22. recognized semi-precession cycles in the interval between 1145 m and 1166 m using magnetic susceptibility (MS) datasets. Later, de Winter et al.7. provided high-resolution stratigraphic color reflection proxy (L*) for the interval between 1145.132 m and 1163.42 m, and unveiled millennial-scale cycles. However, their analyses are all implemented on the depth domain, which may induce a large bias when interpreting these cycles, especially for the millennial-scale cycles. This high-resolution L* was reevaluated here using the TimeOpt method28, and periodogram spectral approach, as well as bicoherence spectra58,59.

Chronology

The age model of the K2n1+2 in the SK2 core was established based on the U-Pb chemical abrasion-isotope dilution-thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-ID-TIMS) zircon dating and cyclostratigraphic analysis24. The zircon U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS dating of four bentonite layers in the depositions of K2n1+2 of SK2 core (at depths of 1139.39 m, 1142.49 m, 1218.61 m, and 1236.81 m) yielded ages of 83.35 ± 0.11 Ma, 83.498 ± 0.052 Ma, 84.45 ± 0.14 Ma, and 84.709 ± 0.064 Ma, respectively (Fig. S1). Based on this depth-age model, the average sedimentary accumulation rate (SAR) for the entire K2n1+2 in the SK2 core is ~7.45 cm/kyr. Under this SAR constraint, long-eccentricity signals were recognized and filtered from the Gamma Ray (GR) logging datasets of SK2. Because long-eccentricity cycles have remained stable over the past 250 Ma30, the filtered and interpreted long eccentricity signals in GR were tied to the 405-kyr periodicity to establish a floating astronomical time scale (ATS) for the K2n1+2 in the SK2 core24. This floating ATS was then anchored to the U-Pb age at 1142.49 m, yielding a SAR of ∼6.36 cm/kyr for the studied interval of this study (1137.84–1145.2 m). This tuned SAR agrees with Monte Carlo numerical simulations based on GR datasets from the same core, which estimated an optimal SAR of ∼6.3–7.1 cm/kyr24. In addition, optimal SARs estimated for the K2n1+2 in adjacent cores are ∼6.79 cm/kyr in the SK1S55 and ∼6.6–8.3 cm/kyr in SK1N24. Using this anchored ATS, the stratigraphic grayscale, log (Ca/Ti), and Rb/Sr datasets were transformed into the time domain.

The age model of the DSDP–516 F core was established based on magnetostratigraphic and cyclostratigraphic analyses. Magnetostratigraphy places the 1198.44–1125.68 m interval within magnetochron C33r23 (Fig. S3A). According to the geomagnetic polarity time scale 2020 (GPTS2020)27, the C33n/C33r and C33r/C34n boundaries occur at 79.9 Ma and 82.9 Ma, respectively. This depth-age model yields an average SAR of 2.43 cm/kyr for 1198.44–1125.68 m interval, consistent with Park et al.22. who estimated a SAR of 2.24 cm/kyr. Based on this magnetochronology and linear interpolation, the stratigraphic interval covered by the L* datasets (1163.42–1145.132 m) is approximately dated to 81.456–80.702 Ma (Fig. S3B). Because the timespan of this interval is shorter than two long eccentricity cycles ( ~ 754 kyr), tunning the interpreted long-eccentricity cycle in L* to a ~ 405-kyr periodicity is unreliable. However, previous cyclostratigraphy identified significant eccentricity and precession cycles, particularity with prominent double peaks at precession band in both magnetic susceptibility (MS) and L* datasets7,22. In the theoretical astronomical solution, precession amplitude is modulated by eccentricity. The TimeOpt algorithm28 in the R package Astrochron58 estimates the optimal SAR and constructs the ATS from this modulation relationship. We therefore applied TimeOpt to transform the stratigraphic L* datasets into the time domain. With a Monte Carlo procedure, TimeOpt identifies an optimal SAR within a given range by simultaneously optimizing: (1) eccentricity amplitude modulations within the precession band, and (2) the concentration of spectral power at specified target astronomical periods28. The optimization is quantified by a value, r2opt (Fig. S4F), which is the product of two separated correlations: (1) r2envelope, the correlation between eccentricity cycles and the precession envelope in the reconstructed time-domain datasets (Fig. S4C–E); (2) r2spectral, the correlation between the spectra of datasets and the coeval theoretical astronomical solutions (gray line in Fig. S4B, E). Here, under the constraint of magnetochronology, the tested SAR range for TimeOpt algorithm was set to 0.1–5 cm/kyr, and the target/theoretical eccentricity and precession periodicity were set at 409.6, 132.129, 126.0308, 99.9024, 96.3765, 22.6925, 21.5013, 18.4921, 18.3677 kyr, based on the La04 astronomical solution at 83 Ma30. The resulting floating ATS returns an optimal SAR of 2.37 cm/kyr, and was then anchored at the magnetochronological age of 80.702 Ma at 1145.132 m.

Grayscale extraction

The recovered cores of lower Nenjiang Formation from SK2 core were segmented with 1 m spacing. These segments were cut into two halves, with one of them being polished and covered with transparent crystal resins. These working halves were photographed. After being transformed into 8-bit format of these core photographs, the grayscale data for the lowest part of the second member of Nenjiang Formation (1145.23–1137.84 m) were extracted with 1 cm spacing using the ImageJ software. The scale for grayscale is pixel. The cracks and bentonite layers were ignored.

XRF-core scanning

Based on these working halves, the bulk elemental composition of the lower Nenjiang Formation in the SK2 core was measured at the State Key Laboratory of Biological Geology and Environmental Geology of the China University of Geosciences using an Itrax X-ray Fluorescence Core Scanner (Cox Analytical Instruments). The scanner was operated at a stratigraphic resolution of 3 mm with a Cr tube as the X-ray source. Each scan lasted for 40 s with current and voltage setting of 30 mA and 30 kV. The acquired elements are scaled with counts per second (cps), representing a semi-quantitative result. Data points associated with crocks and bentonites were removed, and the acquired datasets were resampled at 1 cm spacing to align with the resolution of grayscale. Here, the log (Ca/Ti) and Rb/Sr ratios were used due to their high quality.

Thin-section petrography, quantitative XRF, LA-ICP-MS, and XRD analyses

To calibrate the semi-quantitative XRF-core scanning results, and to confirm the petrographic and mineralogical characteristics of the lower Nenjiang Formation of SK2 core in the SLB, four thin-section and twenty-five bulk samples were taken from the box 59 of the core, between 1141.0 and 1141.7 m (Fig. S2). The core samples are preserved in the Cores and Samples Center of Nature Resources of China. Thin-section examination: The four thin-section samples were cut, mounted on glass slides, and ground and polished to a thickness of ~30 μm. Thin sections were examined under a Leica DM2500 polarizing microscope using transmitted light at the Chinese University of Geosciences, Beijing, to identify mineral phases, microstructures, and sedimentary textures. XRF: Bulk-rock major elements (Si, Ca, Ti) were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) using a Bruker S8 TIGER wavelength-dispersive spectrometer. The analytical procedure followed the Chinese industry standard JY/T 016–1996 General Rules for Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. The analytical process generally involved sample powdering by agate abrasion, pellet preparation, and quantitative measurement under standard conditions. Certified reference materials were analyzed together with the samples for calibration and quality control. Analytical precision is better than 5% relative standard deviation (RSD). Detection limits are typically <0.01 wt% for these major elements. LA-ICP-MS: Bulk-rock trace-elements (Rb and Sr) were analyzed by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) using a Thermo Scientific iCAP RQplus ICP-MS instrument. Analytical procedures followed the Chinese industry standard JY/T 015-1996 General Rules for Inductively Coupled Plasma-atomic Emission Spectrometry. In general, powdered rock samples were digested and introduced into the plasma for quantitative analysis. The minimum detection limit for Rb and Sr is 0.01 ppm. Certified reference materials were analyzed together with the samples to monitor instrumental drift and ensure analytical accuracy and reproducibility. XRD: The mineral composition (e.g., calcite and quartz) of bulk mudstones was determined by X-ray diffractometer (XRD) using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer, following the Chinese industry standard SY/T 5163-2010 Analysis Method for Clay Minerals and Ordinary Non-clay Minerals in Sedimentary Rocks by the X-ray Diffraction. Powdered samples were analyzed under standard conditions, and relative mineral abundances were determined by Rietveld refinement. Analytical precision for major mineral phases was generally better than ±2 wt%.

XRF, LA-ICP-MS, and XRD analyses were implemented at the Beijing Beida Zhihui Microstructure Analysis & Testing Center. Prior to analysis, the bulk samples were ground to powders (<200 mesh) by agate abrasion.

Timeseries analysis

The precise recognition of millennial-scale cycles needs high spectral resolution. Thus, we used the periodogram method to detect the periodical components within the datasets. Both conventional autoregressive-1 (AR-1)60 and robust AR-1 noise model testing61 were employed to evaluate spectra against the stochastic null model. To avoid the incorrect rejection of the null hypothesis of stochastic variability during the noise model test (false positives), multiple-testing corrections are necessary. Here, the False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach of Benjamini and Hochberg25,26 was employed to correct the null hypothesis for the periodogram spectra. The evaluative power spectrum of L* datasets was realized using Evolutive Harmonic Analysis (EHA)62 with eha function in the R package Astrochron58, the parameter setting refers to R codes in the Supplementary Information. Periodogram, AR-1 noise model testing, the multiple-testing corrections, and the TimeOpt analysis were realized in the Astrochron package58 based on R codes (Supplementary Information). A bandpass filter63 was employed to isolate the presumed eccentricity, precession, and millennial-scale components from the datasets. The filtered millennial-scale components were then subjected to a Hilbert transform to estimate the amplitude modulation (AM) of millennial cycles, allowing evaluation of the relationship between millennial and astronomical cycles. The Multi-Taper Method (MTM)62 was also used as an alternative to the periodogram spectral method to detect the periodicity in the timeseries. Filter, Hilbert transform, and MTM analyses were implemented in Acycle software64.

Bicoherence spectra

The high-order bicoherence spectrum analysis was utilized to detect the potential nonlinear intermodulation/frequency mixing of different frequencies65,66. The coherence here refers to the coupling of two fundamental frequencies, f1 and f2, to generate a third frequency, f3, where f3 = f1 + f2, with their phases being coupled8,59. To reduce the spurious bicoherence peaks, the bicoherence method based on WOSA spectra67,68 was employed. The bicoherence spectra were realized using the ‘bicoherence’ function in the R-package Astrchron58,59.

Bioturbation simulation experiment

Bioturbation can destroy primary climate signals and even obscure the high-frequency cycles. To assess its impact on detecting millennial-scale components in the SK2 and DSDP–516 F records under their respective sampling and sedimentation rates, we employed the bioturb function in the R package Astrochron42,58. The bioturbation algorithm is a function of mix layer depth (ML), diffusion/bioturbation intensity (G), and sedimentation accumulation rate (v)42. Two scenarios were tested (Fig. S8), representing typical marine mixing depths (5 and 10 cm), with diffusion/bioturbation intensity fixed at G = 1.

Latitudinal evolution of the quarter-precessional variance in the equatorial insolation

The equatorial insolation over the last 400 kyr at latitudes between 20°S and 20°N were initially calculated following the procedure of Berger et al.11. with a 0.1° step. Then, the power ratios at the 5.5-kyr band in these calculated special insolation curves were extracted using the integratePower function in the R package Astrochron58,69. The frequency bandpass was set as 0.18 ± 0.02 cycles/kyr. See the R codes in the Supplementary Information for details.

Data availability

All relevant proxy datasets of SK2 core that support the findings of this research are available in the Supplementary Datasets 1–3. The L* datasets of DSDP–516 F borehole are from de Winter et al.7. and can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.828372.

Code availability

The grayscale extraction was implemented using ImageJ software, downloaded at https://imagej.net. The periodogram spectra, multitest, bicoherence spectra, and bioturbation simulation were analyzed using R package Astrochron, which can be accessed at https://cran.r-project.org/package=astrochron58. The corresponding R codes please refer to the Supplementary Information. The Bandpass filter, Hilbert transform, and MTM spectrum were implemented using the Acycle software64, which can be downloaded at https://acycle.org/.

References

Mitchell, J. M. An overview of climatic variability and its causal mechanisms. Quat. Res. 6, 481–493 (1976).

Dansgaard, W. et al. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364, 218–220 (1993).

Heinrich, H. Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130,000 years. Quat. Res. 29, 142–152 (1988).

Menviel, L. C., Skinner, L. C., Tarasov, L. & Tzedakis, P. C. An ice–climate oscillatory framework for Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 677–693 (2020).

Anderson, R. Y. Enhanced climate variability in the tropics: a 200,000 yr annual record of monsoon variability from Pangea’s equator. Climate 7, 757–770 (2011).

De Vleeschouwer, D., Da Silva, A. C., Boulvain, F., Crucifix, M. & Claeys, P. Precessional and half-precessional climate forcing of Mid-Devonian monsoon-like dynamics. Climate 8, 337–351 (2012).

De Winter, N. J., Zeeden, C. & Hilgen, F. G. Low-latitude climate variability in the Heinrich frequency band of the Late Cretaceous greenhouse world. Climate 10, 1–15 (2014).

Da Silva, A. C. et al. Millennial-scale climate changes manifest Milankovitch combination tones and Hallstatt solar cycles in the Devonian greenhouse world. Geology 47, 19–22 (2019).

Ma, C. et al. Centennial to millennial variability of greenhouse climate across the mid-Cenomanian event. Geology 50, 227–231 (2022).

Pas, D. et al. Millennial-scale climate cycles modulated by Milankovitch forcing in the middle Cambrian (ca. 500 Ma) Marjum Formation, Utah, USA. Geology 52, 605–609 (2024).

Berger, A., Loutre, M. F. & Mélice, J. L. Equatorial insolation: from precession harmonics to eccentricity frequencies. Climate 2, 519–533 (2006).

Huber, B. T., MacLeod, K. G., Watkins, D. K. & Coffin, M. F. The rise and fall of the Cretaceous Hot Greenhouse climate. Glob. Planet. Change 167, 1–23 (2018).

Klages, J. P. et al. Temperate rainforests near the South Pole during peak Cretaceous warmth. Nature 580, 81–86 (2020).

Wang, C. S., Gao, Y., Ibarra, D. E., Wu, H. C. & Wang, P. J. An unbroken record of climate during the age of dinosaurs. Eos 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO158455 (2021).

Hajek, E. A. & Straub, K. M. Autogenic sedimentation in clastic stratigraphy. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 45, 681–709 (2017).

Yang, D. et al. Grain-size component-dependent storage threshold of orbital cycles in alluvial stratigraphy caused by autogenic dynamics. Sedimentology 71, 1686–1704 (2024).

Chen, J., An, Z. S. & Head, J. Variation of Rb/Sr ratios in the loess paleosol sequences of central China during the last 130,000 years and their implications for monsoon palaeoclimatology. Quat. Res. 51, 215–219 (1999).

An, F. Y., Lai, Z. P., Liu, X. J., Fan, Q. S. & Wei, H. C. Abnormal Rb/Sr ratio in lacustrine sediments of Qaidam Basin, NE Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: a significant role of aeolian dust input. Quatern. Int. 469, 44–57 (2018).

Yang, H. F., Huang, Y. J., Ma, C., Zhang, Z. F. & Wang, C. S. Recognition of Milankovitch cycles in XRF core-scanning records of the Late Cretaceous Nenjiang Formation from the Songliao Basin (northeastern China) and their paleoclimate implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 194, 104183 (2020).

Hasegawa, H. et al. Decadal–centennial‑scale solar‑linked climate variations and millennial‑scale internal oscillations during the Early Cretaceous. Sci. Rep. 12, 21894 (2022).

Haberzettl, T. et al. Late Pleistocene dust deposition in the Patagonian steppe—extending and refining the paleoenvironmental and tephrochronological record from Laguna Potrok Aike back to 55 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 2927–2939 (2009).

Park, J., D’Hondt, S. L., King, J. W. & Gibson, C. Late Cretaceous precessional cycles in double time: a warm-earth Milankovitch response. Science 261, 1431–1434 (1993).

Hamilton, N. & Suzyumov, A. E. Late Cretaceous magnetostratigraphy of Site 516, Rio Grande Rise, Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Drilling Project, Leg 72. https://doi.org/10.2973/dsdp.proc.72.132.1983 (1983).

Zhang, Z. F., Huang, Y. J., Li, M. S., Li, X. & Ju, P. C. Obliquity-forced aquifer-eustasy during the Late Cretaceous greenhouse world. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 596, 117800 (2022).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Crampton, J. S. et al. Pacing of Palaeozoic macroevolutionary rates by Milankovitch grand cycles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 115, 5686–5691 (2018).

Ogg, J. G. Chapter 5 - Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale. In Geologic Time Scale 2020 (ed. Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. D., Ogg, G. M.) 159–192 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824360-2.00005-X (Elsevier, 2020).

Meyers, S. R. The evaluation of eccentricity-related amplitude modulation and bundling in paleoclimate data: An inverse approach for astrochronologic testing and time scale optimization. Paleoceanography 30, 1625–1640 (2015).

Berger, A. Long-term variations of daily insolation and Quaternary Climatic Changes. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 2362–2367 (1978).

Laskar, J., Robutel, P. & Joutel, F. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth. Astron. Astrophys. 428, 261–285 (2004).

Short, D. A., Mengel, J. G., Crowley, T. J., Hyde, W. T. & North, G. R. Filtering of Milankovitch cycles by Earth’s geography. Quat. Res 35, 157–173 (1991).

Hagelberg, T. K., Bond, G. & deMenocal, P. Milankovitch band forcing of sub-Milankovitch climate variability during the Pleistocene. Paleoceanography 9, 545–558 (1994).

Berger, A. & Loutre, M. F. Intertropical latitudes and precessional and half-precessional cycles. Science 278, 1476–1478 (1997).

Wu, Z. P., Yin, Q. Z., Berger, A. & Guo, Z. T. Forcing mechanisms of the half-precession cycle in the western equatorial Pacific temperature. Nat. Commun. 16, 1841 (2025).

Verschuren, D. et al. Half-precessional dynamics of monsoon rainfall near the East African Equator. Nature 462, 637–641 (2009).

Sun, Y. B. et al. Suborbital- and millennial-scale monsoon variability during Pleistocene interglacials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2426353122 (2025).

Jian, Z. M. et al. Half-precessional cycle of thermocline temperature in the western equatorial Pacific and its bihemispheric dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 7044–7051 (2020).

Friedrich, O., Nishi, H., Pross, J., Schmiedl, G. & Hemleben, C. Millennial- to centennial-scale interruptions of the oceanic anoxic event 1b (Early Albian, mid-Cretaceous) inferred from benthic foraminiferal repopulation events. PALAIOS 20, 64–77 (2005).

Kravchinsky, V. A. et al. Millennial cycles in Greenland and Antarctic ice core records: evidence of astronomical influence on global climate. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 130, e2024JD042810 (2025).

Rial, J. A. et al. Nonlinearities, feedbacks and critical thresholds within the Earth’s climate system. Clim. Change 65, 11–38 (2004).

Tuenter, E., Weber, S. L., Hilgen, F. J. & Lourens, L. J. Simulating sub-Milankovitch climate variations associated with vegetation dynamics. Climate 3, 169–180 (2007).

Liu, H., Meyers, S. R. & Marcott, S. A. Unmixing deep-sea paleoclimate records: a study on bioturbation effects through convolution and deconvolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 564, 116883 (2021).

Braun, H. et al. Possible solar origin of the 1,470-year glacial climate cycle demonstrated in a coupled model. Nature 438, 208–211 (2005).

Gloersen, P. Modulation of hemispheric sea-ice cover by ENSO events. Nature 373, 503–506 (1995).

Chiang, J. C. H. & Sobel, A. H. Tropical tropospheric temperature variations caused by ENSO and their influence on the remote tropical climate. J. Clim. 15, 2616–2631 (2002).

Davies, A., Kemp, A. E. S. & Pike, J. Late Cretaceous seasonal ocean variability from the Arctic. Nature 460, 254–258 (2009).

Davies, A., Kemp, A. E. S., Weedon, G. P. & Barron, J. A. El Niño-Southern oscillation variability from the late Cretaceous Marca shale of California. Geology 40, 15–18 (2012).

Hu, J. F. et al. Seawater incursion events in a Cretaceous paleo-lake revealed by specific marine biological markers. Sci. Rep. 5, 9508 (2015).

Qin, Z. et al. Rhenium-platinum group elements reveal seawater incursion induced massive lacustrine organic carbon burial. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 384, 168–177 (2024).

Xi, D. P. et al. Late Cretaceous marine fossils and seawater incursion events in the Songliao Basin, NE China. Cretac. Res 62, 172–182 (2016).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Past climates inform our future. Science 370, 680 (2020).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss 2019, 1–77 (2019).

Zeebe, R. E. Highly stable evolution of Earthʼs future orbit despite chaotic behaviour of the solar system. Astrophys. J. 811, 9 (2015).

Feng, Z. Q. et al. Tectonostratigraphic units and stratigraphic sequences of the nonmarine Songliao basin, northeast China. Basin Res. 22, 79–95 (2010).

Wu, H. C. et al. Continental geological evidence for Solar System chaotic behavior in the Late Cretaceous. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135, 712–724 (2022).

Barker, P. F. et al: Shipboard Scientific Party: Site516: Rio Grande Rise, in: Init. Repts. DSDP, 72, edited by: Barker, P. F., Carlson, R. L., and Johnson, D. A., US Govt. Printing Office, Washington, 155–338 (1983).

Moulin, M., Aslanian, D. & Unternehr, P. A new starting point for the South and Equatorial Atlantic Ocean. Earth-Sci. Rev. 98, 1–37 (2010).

Meyers, S. R. Astrochron: an R package for astrochronology. https://cran.r-project.org/package=astrochron (2014).

Sullivan, N. B. et al. Millennial-scale variability of the Antarctic ice sheet during the early Miocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304152120 (2023).

Meyers, S. R. Seeing red in cyclic stratigraphy: spectral noise estimation for astrochronology. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol 27, PA3228 (2012).

Mann, M. E. & Lees, J. M. Robust estimation of background noise and signal detection in climatic time series. Clim. Change 33, 409–445 (1996).

Thomson, D. J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc. IEEE 70, 1055–1096 (1982).

Kodama, K. P. & Hinnov, L. A. Rock magnetic cyclostratigraphy. New analytical methods in earth and environmental science series. Wiley-Blackwell, 1–147 (2014).

Li, M. S., Hinnov, L. & Kump, L. Acycle: time-series analysis software for paleoclimate research and education. Comput. Geosci. 127, 12–22 (2019).

Hagelberg, T., Pisias, N. & Elgar, S. Linear and nonlinear couplings between orbital forcing and the marine δ18O record during the Late Neocene. Paleoceanography 6, 729–746 (1991).

King, T. Quantifying nonlinearity and geometry in time series of climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 15, 247–266 (1996).

Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoustics 15, 70–73 (1967).

Choudhury, S. M., Shah, S. L. & Thornhill, N. F. “Bispectrum and bicoherence” in diagnosis of process nonlinearities and valve stiction. 29–41 (Springer, 2008).

Meyers, S. R., Sageman, B. B. & Arthur, M. A. Obliquity forcing of organic matter accumulation during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol 27, PA3212 (2012).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (Springer, New York, 2016).

Macdonald, F. A., Swanson-Hysell, N. L., Park, Y., Lisiecki, L. & Jagoutz, O. Arc-continent collisions in the tropics set Earth’s climate state. Science 364, 181–184 (2019).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration - National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2024ZD1001105), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42272134 to Y.H., 42488201 to C.W., 42502020 to Z.Z., 42172137 to C.M.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFF0804000 to C.M.), “Deep-time Digital Earth” Science and Technology Leading Talents Team Funds for the Central Universities for the Frontiers Science Center for Deep-time Digital Earth, China University of Geosciences (Beijing) (Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities) (No. 2652023001 to C.W.), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZC20241605 to Z.Z.). Q.Y. is a Senior Research Associate of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique-FNRS (F.R.S.-FNRS) and acknowledges the support of the F.R.S.-FNRS grant n° T.0246.23. Z.Z. gratefully acknowledges the fellowship from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2025M770431). A.-C.D.S. thanks the FNRS support WarmAnoxia (grant T.0037.22).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z., Y.H., Q.Y., and C.W. conceived the study. Z.Z. conducted the analyses and interpretations related to this study. T.W. contributed to the analysis of radioactive chronology. Z.Z. and H.Y. measured the datasets. Z.Z. Led manuscript writing with intellectual contributions from Q.Y., A.-C.D.S., Y.H., E.Y.L., and H.Y., and discussions from C.M., H.C., and T.W. André Berger has checked and confirmed what is said about his theoretical finding of the 1/4 precessionnal cycle.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexander Piotrowski and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Huang, Y., Wang, T. et al. Precession-induced millennial climate cycles in greenhouse Cretaceous. Nat Commun 16, 10696 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66219-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66219-4