Abstract

Prime editing (PE) enables the precise installation of intended base substitutions, small deletions or small insertions into the genome of living cells. While the use of Cas9 nickase can avoid DNA double-strand breaks (DSB), undesired insertions and deletions (indels) often accompany the correct edits, particularly when PE activity increased. Here we show that the anti-CRISPR (Acr) protein AcrIIA5 can significantly enhance PE activity by up to 8.2-fold while markedly reducing byproduct indels. Further investigation reveals that AcrIIA5 can promote PE across various approaches (PE2, PE3, PE4, PE5, and PE6), edit types (substitutions, insertions and deletions), and endogenous loci. Mechanistically, AcrIIA5 appears to inhibit the re-nicking activity of PE complex rather than enhancing the core editing machinery itself, suggesting a distinct mode of interaction with Cas9. Overall, we demonstrate that a known “inhibitor” Acr protein can unexpectedly acting as an “enhancer” of CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing, providing an effective strategy to optimize PE specificity and activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gene editing tools enable targeted changes in the genome of living cells, advancing the life sciences and therapeutic applications1. Programmable nucleases, such as ZFNs2, TALENs3, or CRISPR/Cas nucleases4,5,6, induced targeted DSBs, which can either promote non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated random insertions and deletions (indels), or facilitate homology-directed repair (HDR)-mediated precise corrections in the presence of donor DNA templates. However, DSBs have been proven to carry significant risks, including large DNA rearrangements7,8, deletions8,9, or translocations10, which pose non-negligible safety concerns. Instead, base editors, composed of a deaminase and a Cas protein, can install base transitions like C-to-T11 or A-to-G12, or base transversions like G-to-T13 or T-to-G14,15 without introducing DSBs. However, despite the advantages above, base editors have suffered from insufficient product purity11,13,14,15,16, undesired bystander editing11,12 and off-targeting17,18, severely undermining the accuracy and security.

Advantageously, PE system can precisely install base substitutions, DNA insertions, or DNA deletions in genomes without the need for DSBs or donor DNA templates19. The commonly used PE2 system minimally consists of a modified PE2 protein (Cas9-H840A nickase fused with an engineered Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, M-MLV RT) and a pegRNA that contains both a spacer sequence and a 3’ extension encoding the desired edit. Guided by pegRNA, the PE2 protein binds the target DNA and nicks the PAM-containing strand, forming an exposed 3’ end that pairs to the primer binding site (PBS) in the pegRNA extension. Then, M-MLV RT synthesizes the corresponding sequences guided by RT template (RTT) in pegRNA extension, into the nicked non-target strand (NTS), and the edits are ultimately incorporated into the genome.

To improving PE2 editing efficiency, another sgRNA was introduced in PE3 system to nick the non-edited strand19, while another MLH1dn was fused with PE2 protein in PE4 system to inhibit DNA mismatch repair (MMR) which lead to non-mutated edit20. PE6 systems, which utilized engineered Cas9 proteins or different types of RT, have also demonstrated improved efficiency in certain edits21. Despite avoiding DSBs, PE systems still resulted in noticeable undesired indels which were significantly increased in PE3 or PE5. Besides, PE4 performs well in MMR-active cell strains like K562, but showed marginal improvements in MMR-inactive cell strains like HEK293T. Additionally, MLH1dn fused in PE4 was relatively large (752 amino acids), complicating its incorporation into adeno-associated viruses (AAV), which have a limited encapsulation capacity.

Phage-derived anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins are a class of small proteins (usually <150 amino acids) that strongly inhibit various Cas proteins through diverse mechanisms22. Among them, AcrIIA5 can effectively block the DNA cleavage activity of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9)23,24,25,26 and its derived base editors27.

In this study, we identify that AcrIIA5 can enhance the activity of PE, and consequently develop the AcrIIA5-assisted PE (aPE) system, showing significantly improved editing efficiency and decreased indels simultaneously. We further confirm that aPE performs well across different architectures (PE2, PE3, PE4, PE5, and PE6) and endogenous loci, enhancing substitutions, deletions, and insertions by up to 8.2-fold, 3.2-fold, and 5.2-fold, respectively. Meanwhile, we also observe that aPE can produce variable editing outcomes at different positions within the same target site. Further analyses reveal that edits causing PAM-silencing tended to decrease aPE editing efficiency, whereas edits at PAM-proximal or PAM-distal positions generally benefit from aPE. This position-dependent effect is likely due to AcrIIA5 preventing re-targeting and re-nicking by the SpCas9-H840A of the PE complex. Notably, this regulatory mechanism appears to be unique to AcrIIA5 among tested Acr proteins, highlighting its potential as a versatile modulator for PE systems.

Results

AcrIIA5 can enhance PE activity

The anti-CRISPR protein AcrIIA5 can inhibit the gene editing ability of Type II Cas9 by suppressing its cleavage activity25,26. To explore the potential of AcrIIA5 in regulating the CRISPR/Cas9 and its derived systems, we co-delivered it with SpCas9, base editors, and the PE2 system into human HEK293T cells in equimolar (Fig. 1a–c). To eliminate transfection-related effects caused by additional AcrIIA5-expressing plasmid load, we also delivered an equal amount of an empty vector pcDNA3.1(-) without AcrIIA5 as control.

a–c Schematic representation of the expressed SpCas9, CBEs, PE2 and AcrIIA5, and the editing efficiencies of SpCas9 (a), hA3A-CBE (b), and PE2 (c). Each was co-delivered with either an empty vector or a plasmid expressing AcrIIA5. Editing efficiencies (d) and indels (e) of PE2 with different dose of vector or AcrIIA5 for HEK3, +1 T-to-A edit. The dotted red line indicates the baseline level of PE2 alone without co-transfected any vectors. Base conversion efficiencies (f) and indels (g) of PE2 and aPE2 at the +1 to +6 positions in HEK3 target. h Comprehensive editing efficiency comparison of PE2 and aPE2 for base conversions at HEK2, HEK3, HEK5, and HEK6 targets. i Comprehensive indels comparison of PE2 and aPE2 for edits HEK2, HEK3, HEK5 targets. All experiments were conducted in HEK293T cells. The data in (a–g) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

After SpCas9 induces DSBs in the target DNA, cells repair the breaks via NHEJ pathway, resulting in the formation of indels4,5,6. We observed that SpCas9 caused indels of 71.6% at HEK3 locus, while the indels decreased to 20.6% with AcrIIA5 co-transfected (Fig. 1a), indicating that AcrIIA5 significantly inhibited the SpCas9 activity.

The cytosine base editor (CBE), composed of SpCas9-D10A and deaminases, can convert specific cytosines (C) in the target DNA to thymine (T). We observed that CBEs with cytosine deaminases such as hA3A28,29, hA3Bctd30, hA3Gctd31, and mAPOBEC111 as catalytic cores induced efficient C-to-T conversions at positions C3, C4, C5, and C9 in HEK3 locus (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the addition of AcrIIA5 significantly decreased these C-to-T conversions, indicating that AcrIIA5 effectively inhibited the activity of these CBEs.

The PE2 system enables the introduction of the +1 T-to-A conversion at HEK3 target guided by a specific pegRNA. Surprisingly, when AcrIIA5 was co-delivered with the PE2 into HEK293T cells, the intended T-to-A editing efficiency increased from 6.7% to 9.8%, suggesting that AcrIIA5 may enhance the activity of the PE system (Fig. 1c).

Previous reports have proven that varying doses of AcrIIA5 can inhibit SpCas927 and base editors26 to different extents. Therefore, we hypothesized that the dosage of AcrIIA5 might similarly affect the performance of PE system. Then, we co-delivered AcrIIA5 and the PE2 system into HEK293T cells at molar ratios of 0.1/0.2/0.3/0.4/0.5/0.6/0.8/1.0/1.5/2.0/2.5/3.0 to introduce +1 T-to-A at HEK3 locus (Fig. 1d). The results showed that the PE2 alone caused conversion of 6.7%, and co-delivery with varying doses of the empty vector resulted in similar efficiencies.

In stark contrast, different doses of AcrIIA5 had a significant impact on PE2 activity, with the maximum +1 T-to-A conversion reached 24.9% at 0.1 AcrIIA5:PE2 molar ratio. As the molar ratio increased from 0.1 to 3.0, the PE2 efficiency gradually decreased from 24.9% to 8.8%. Additionally, PE2 alone led to 1.4% indels, which remained stable when co-delivered with different doses of the empty vector (Fig. 1e). Theoretically, the indels should decrease with increasing AcrIIA5 dosage. However, even at low molar ratios of 0.1 and 0.2, the indels significantly dropped to 0.5-fold and 0.14-fold of the original rate, respectively.

These results confirmed that AcrIIA5 can enhance the performance of the PE2 by improving activity and decreasing indels. Hence, we named this system as aPE. Considering that with the increasing dosage of AcrIIA5, the increase of PE2 efficiency gradually declined, thus we selected 0.1 molar ratio of AcrIIA5:PE in subsequent tests except other explanations, aiming to achieve the optimal enhancement of PE activity.

Investigation of aPE-introduced base conversions

Previous results have confirmed that aPE2 showed higher editing efficiency in +1 T-to-A edits at HEK3 target. To determine whether this enhancement can extend to other types of base conversions, we unbiasedly tested all possible base mutations across +1 to +6 positions (Fig. 1f). To our surprise, aPE2 exhibited two distinct windows with markedly different outcomes. In the +1 to +4 region, the efficiencies of all aPE2-introduced base conversions were remarkably enhanced compared to PE2, with an average increase of 3.4-fold and a maximum increase of up to 5.3-fold (+4 T-to-C). In contrast, all aPE2-introduced conversions in +5 and +6 location dramatically decreased to average 0.42-fold of PE2. Notably, aPE2-induced indels (average 0.49%) were significantly reduced almost in all base conversions across +1 to +6 compared to PE2 (average 1.28%) (Fig. 1g).

The above results suggested that the improvement of PE2 activity by AcrIIA5 may be influenced more by the position of the edited base than by the type of base conversion. To verify this assumption, we evaluated each base conversion, including both transitions and transversions, at position +1 to +6 in three additional targets. Similar to HEK3 locus, aPE2-introduced conversions efficiencies in +1 to +4 at HEK2 locus increased by an average of 1.9-fold, while conversions at positions +5 and +6 were reduced (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Somewhat differently, aPE2-introduced base conversions efficiencies were only improved in +1 to +3 at HEK5 (average 3.2-fold) (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and HEK6 (average 2.2-fold) (Supplementary Fig. 2c), while those conversions in +4 to +6 regions were inhibited. Meanwhile, almost all indels alongside the edits across the three additional targets obviously decreased (Supplementary Fig. 2d–f).

After analyzing all the edits introduced by PE2 and aPE2 across the four tested targets (Fig. 1h), we observed that the aPE2 activity for base conversions at positions +1 to +4 increased to 2.7-fold, 3.0-fold, 2.5-fold, and 1.9-fold of that observed by PE2, respectively. While the base conversion efficiencies by aPE2 were reduced to 0.42-fold and 0.48-fold of those observed by PE2 at positions +5 and +6. Interestingly, PE2 showed higher editing efficiency at positions +5 and +6 and lower editing efficiency at positions +1 to +4. Moreover, the indels comparison of HEK2, HEK3, and HEK5 (HEK6 was excluded as high background) targets revealed that the average aPE2-induced indels across positions +1 to +6 were reduced to 0.29-fold, 0.26-fold, 0.34-fold, 0.30-fold, 0.54-fold, and 0.45-fold, respectively, of that caused by PE2 (Fig. 1i).

These results confirmed that the enhancement of PE2 activity assisted by AcrIIA5 was independent of the base conversion types and was solely related to the position of the edited base within the targets. Additionally, almost all indels across positions +1 to +6 caused by aPE2 were obviously inhibited compared to PE2, proving the high security and accuracy of aPE2.

Compatibility of aPE with various constructs

As the most commonly used version, PE2 showed limitations in activity. PE3 employed additional sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand, greatly enhancing the PE2 activity19. PE4 showing high activity was engineered through the fusion of PE2 and MLH1dn protein which inhibited the MMR, and PE5 was constructed with the addition of a sgRNA nicking the non-edited strand20. However, PE3 and PE5 usually induced significantly increased indels, reducing the purity of editing outcomes. Besides, although PE4 performed well in MMR-active cell lines like K562, but showed only slight improvement in MMR-inactive cell lines like HEK293T. Considering the outstanding performance of aPE2 in enhancing the editing efficiency and accuracy, we hypothesized AcrIIA5 may also improve the PE3, PE4, and PE5 architectures. Subsequently, we tested these PE and aPE systems at three individual edits in three different targets.

The results indicated that AcrIIA5 can advance the editing efficiency of all tested PE architectures at the HEK2, +3 C-to-A edits (Fig. 2a). Specifically, additional sgRNAs causing –36 nick and –40 nick did not enhance the activity of PE2 or PE4, while only the introduction of +21 nick increased the performance of PE2 and PE4, raising their efficiencies from 23.8% (PE3 + 21 nick) and 28.0% (PE5 + 21 nick), to 31.2% (aPE3 + 21 nick) and 29.2% (aPE5 + 21 nick), respectively. Besides, AcrIIA5 significantly boosted the efficiencies of PE2 (from 16.2% to 37.2%) and PE4 (from 17.0% to 35.6%), suggesting that AcrIIA5’s assistance may be more effective for PE2 and PE4 compared to PE3 and PE5. Additionally, all aPE constructs exhibited significantly reduced indels compared to PE constructs (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similar results can be observed at HEK5, +2 T-to-C edits (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3b) and HEK6, +2 G-to-A edits (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Editing efficiency of PE2, PE3, PE4, and PE5 with or without AcrIIA5 for HEK2, +3 C-to-A (a), HEK5, +2 C-to-T (b), and HEK6, +2 G-to-A (c). d Comprehensive editing efficiency comparison of PE2, PE3, PE4 and PE5 with or without AcrIIA5 for edits of (a–c). e Comprehensive indels comparison of PE2, PE3, PE4 and PE5 with or without AcrIIA5 for edits of (a, b). f Editing efficiency and indels of nSpRY-H840A-based PE2 or aPE2. Targets with GGG, TGC, GAT, and AAA PAM at HEK2 locus were tested. All experiments were conducted in HEK293T cells. The data in (a–c, f) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Comprehensive comparison clearly revealed distinction between PE and aPE systems (Fig. 2d). In the intra-comparison within the PE system, the editing efficiency of PE2 (7.5%), PE4 (8.2%), PE3 (8.6%), and PE5 (10.7%) showed a progressive increase, suggesting that in the MMR-deficient HEK293T cell line, nicking the non-editing strand (PE3) can enhance PE2 activity more effectively than fused MLH1dn (PE4), and these two enhancements were additive (PE5) (Fig. 2d). However, in the intra-comparison within the aPE system, the editing efficiency of aPE2 (19.2%), aPE4 (17.7%), aPE3 (15.6%), and aPE5 (11.6%) showed a progressive decrease.

In the inter-comparison between PE and aPE, aPE exhibited significantly higher editing activity (Fig. 2d). For instance, the average editing efficiencies of aPE2, aPE4, aPE3, and aPE5 were 2.6-fold, 2.2-fold, 1.8-fold, and 1.1-fold higher, respectively, compared to their corresponding PE systems. Notably, PE3 and PE4 only increased PE2 activity to 1.31-fold and 1.05-fold, respectively, which were significantly lower than the 2.6-fold increase achieved by aPE2, indicating that AcrIIA5 was more effective than MLH1dn (PE4) and the additional nicking sgRNA (PE3) (Fig. 2d). Moreover, aPE2 reached 1.8-fold of the activity of PE5 which was considered as the most effective architecture, confirming the strong potency of AcrIIA5.

In the comprehensive statistics of indels, PE2, PE4, PE3, and PE5 showed average indels of 5.05%, 3.04%, 8.09%, and 6.53%, respectively (Fig. 2e), which proved the high efficacy of MLH1dn in reducing by-products and confirmed that the additional nicking sgRNA in PE3 or PE5 would significantly increase the indels. Notably, all aPE constructs exhibited superb decrease of indels compared to according PE constructs (Fig. 2e). For example, aPE2, aPE3, aPE4, and aPE5 showed average indels of 1.11%, 0.77%, 1.47%, and 0.81%, respectively. Notably, MLH1dn reduced indels by 1.66-fold (PE4) and 1.24-fold (PE5) for PE2 and PE3, respectively, while AcrIIA5 reduced indels by 4.5-fold (aPE2) and 5.5-fold (aPE3) for PE2 and PE3, respectively, suggesting that AcrIIA5 was more effective than MLH1dn in reducing by-product indels. Besides, MLH1dn had a length of 752 amino acids (2256 bp), while AcrIIA5 was only 140 amino acids (420 bp). Therefore, AcrIIA5 may be more suitable for integration into AAV vectors with a 4.7 kb packaging limit.

Furthermore, we speculated on the reason for the progressively decreased editing activity observed from aPE2 to aPE5. We guessed that this phenomenon may stem from structural and expression-related constraints inherent to these more complex architectures. In PE4 and PE5, the MMR inhibitor MLH1dn is co-expressed via a P2A self-cleaving peptide. However, the cleavage efficiency of the P2A sequence has been reported to be incomplete in HEK293T cells32. This incomplete cleavage may lead to a subset of SpCas9-RT fusion proteins retaining a covalently linked MLH1dn domain. Given that MLH1dn is a relatively large protein, this residual fusion could introduce steric hindrance that interferes with AcrIIA5’s interaction with SpCas9, thereby diminishing its enhancing effect in PE4 and PE5.

To investigate whether the genetic linkage between the PE2 expression cassette and MLH1dn via a P2A sequence affects the regulatory impact of AcrIIA5, we constructed an additional system in which MLH1dn is expressed from a separate plasmid. For clarity, we refer to the original PE4 system as PE2+iMLH1dn (integrated MLH1dn) and the system with independent MLH1dn expression as PE2+sMLH1dn (separate MLH1dn). We then evaluated editing efficiencies across the PE2–PE5 architectures under these modified conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). Consistent with our earlier findings, aPE2 exhibited higher editing efficiency than aPE2+iMLH1dn, and similarly, aPE3 outperformed aPE3+iMLH1dn (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Strikingly, both aPE2+sMLH1dn and aPE3+sMLH1dn showed even greater editing efficiencies than their respective aPE2 and aPE3 counterparts. This unexpected result further supports our hypothesis that incomplete P2A cleavage in PE4 can lead to residual MLH1dn interfering with AcrIIA5–SpCas9 interactions, thereby reducing its regulatory effect. Moreover, the improved performance of aPE systems when MLH1dn is delivered in trans highlights the modularity and extensibility of the aPE platform.

Besides, a recent study reported that the La protein can significantly enhance the editing efficiency of PE systems through binding to the poly(U) at the 3’ end of pegRNA33. Consistent with this, we observed that PE7 increased the HEK3, +1 T-to-A conversion to a level comparable to that of aPE2, although it produced higher indel frequencies than aPE2 (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Interestingly, however, PE7 exhibited markedly reduced activity when combined with AcrIIA5, suggesting that the presence of the La protein may counteract the effect of AcrIIA5. Given that the only difference between PE2 and PE7 is the addition of the La protein, which stabilizes the pegRNA by binding its 3’ poly(U) tail, we hypothesized that this component is a key factor influencing the response of aPE7 to AcrIIA5.

According to previous reports26, AcrIIA5 can bind to sgRNA in SpCas9 complex, suggesting it may also interact with pegRNA. We speculated that AcrIIA5 and La protein might interfere with each other on the pegRNA scaffold. Besides, like iMLH1dn tested above, the La protein alone may also prevent the AcrIIA5-SpCas9 interaction through steric hindrance. To investigate these possibilities, we engineered a system in which the poly(U) tail was removed by inserting a self-cleaving HDV ribozyme between the pegRNA and the poly(U) sequence (Supplementary Fig. 3g). This ribozyme cleaves cotranscriptionally, producing pegRNA transcripts lacking the poly(U) extension. We then compared the editing efficiencies of PE2, PE7, aPE2, and aPE7 systems with or without the poly(U) tail.

We first observed that aPE2 with HDV-cleaved pegRNA exhibited higher editing efficiency than the corresponding PE2 control, confirming that AcrIIA5 functions independently of the poly(U) sequence and does not act through direct binding to it (Supplementary Fig. 3h). Next, we found that PE7 with HDV-cleaved pegRNA restored editing activity to levels comparable to PE2, consistent with La protein requiring poly(U) to exert its function. Notably, aPE7 with HDV-cleaved pegRNA also regained activity similar to aPE2, proving that the size of La protein alone can not prevent the AcrIIA5-SpCas9 interaction through steric hindrance. Together, these results support a refined model in which the poly(U) tail enables La protein binding to the 3’ end of pegRNA, and this bound La protein indirectly interferes with AcrIIA5 function. This spatial interference likely impairs AcrIIA5’s ability to fine-tune the SpCas9–pegRNA complex, ultimately leading to the decreased editing efficiency observed in the aPE7 system.

Overall, we have proven AcrIIA5 was compatible with a wide range of PE architectures. Especially, aPE2 not only demonstrated higher activity than PE3 but also maintained lower indels compared to PE4, reflecting both high editing activity and accuracy.

In addition to introducing extra non-edited strand nicking sgRNAs and MLH1dn proteins that inhibited MMR, modifying the pegRNA, SpCas9-H840A, and RT in the PE systems can also affect editing outcomes. Recent study confirmed that the epegRNA with a 3’ exonuclease protection motif can improve the PE performance34. Furthermore, through extensive amino acid mutations screening and phage-assisted directed evolution, series of novel PE systems were developed, including PE6a (SpCas9-H840A+evoEc48 RT), PE6c (SpCas9-H840A+evoTf1 RT), PE6d (with additional T128N + V223Y + D200C mutations in the M-MLV RT and deletion of the RNase H domain), and PE6e (with additional K918A + K775R mutations in SpCas9-H840A)21.

In this study, by introducing a variety of potentially effective amino acid mutations into the M-MLV RT35 of PE2, we successfully identified mutations such as L139P, E302R, and V223A that can enhance editing efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We hypothesized that combinations of these mutations could further enhance PE2 activity. Consequently, we generated PE2 variants with additional mutations in M-MLV RT, including PE2-PR (additional L139P + E302R), PE2-PA (additional L139P + V223A), PE2-AR (additional V223A + E302R), and PE2-PAR (additional L139P + V223A + E302R). Subsequently, we tested these PE variants with changes in SpCas9 or RT and with the epegRNA with 3’ evopreQ1 motif. The results showed all tested PE variants showed higher activity and lower indels with the assistance of AcrIIA5 in +1 T-to-A edit at HEK3 target (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In detail, aPE variants showed 1.05-fold to 2.40-fold of the PE variants activity. Among them, PE2-PA exhibited the highest initial editing efficiency of 17.76%, which was further increased to 20.33% with the assistance of AcrIIA5, and aPE2 showed highest activity in aPE variants. Similarly to previous results, indels caused by aPE variants substantially decreased to 0.16-fold to 0.40-fold compared to PE variants.

To further assess the generalizability of the aPE strategy, we compared aPE2 with several recently developed PE variants. We tested PE2, PE_Y1836, PEmax**37, PE2_NC38, and PE2_SB39 at three representative loci with or without AcrIIA5 and found that aPE2 consistently outperformed all of these systems (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, each of the tested variants exhibited further improvements in editing efficiency and reductions in indels formation when combined with AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). This enhancement was also evident in epiPE240 (Supplementary Fig. 5e), whose activity and precision were comprehensively elevated by AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 5f, g). In addition, we examined the compatibility of aPE2 with engineered pegRNAs, including apegRNA41 and mpegRNA42 (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). While both designs improved the performance of wtpegRNA-PE2, their combination with aPE2 resulted in even greater activity together with markedly lower indels formation (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). Notably, the indels formation of mpegRNA-PE2 was reduced from 1.81% to 0.29%, and was further decreased to 0.16% by mpegRNA-aPE2, underscoring the critical role of AcrIIA5 in enhancing both activity and specificity across diverse PE architectures.

Additionally, our study found that the enhancement of base conversions by aPE systems might be position-dependent. However, the SpCas9-H840A in the PE system can only recognize NGG PAM, which limited the positions where aPE system can improve. To address this issue, we replaced SpCas9-H840A in aPE2ΔRNaseH with the PAM-less SpRY-H840A, and tested it at several targets with both conventional and non-conventional PAMs (Fig. 2f). The results showed that in the +1 T-to-A edits at targets with the conventional GGG PAM, the PAM-less PE2ΔRNaseH achieved an editing efficiency of 10.33%, which increased to 14.52% with AcrIIA5. At targets with non-conventional PAMs such as TGC, GAT, and AAA, the PAM-less PE2ΔRNaseH achieved editing efficiencies of 2.33%, 5.02%, and 2.96% for +1 A-to-T, +1 C-to-G, and +1 A-to-T edits, respectively. With the assistance of AcrIIA5, these efficiencies were increased to 5.68%, 10.03%, and 6.96%, respectively. Simultaneously, the indels were significantly reduced in all tested edits. Consequently, the compatibility of AcrIIA5 with the PAM-less PE enhanced the applicability of this strategy.

In conclusion, AcrIIA5 was compatible with most known PE architectures, including various engineered pegRNA, RTs, and SpCas9 variants, as well as the addition of extra MLH1dn protein and nicking sgRNA.

Assessment of aPE-introduced deletions and insertions

PE can not only introduce various types of base conversions but also delete small DNA fragments. To validate whether AcrIIA5 can enhance the performance of PE-mediated deletions, we then examined four targets for testing increasing deletion lengths ranging from 1 to 6 nt.

At the HEK3 target (Fig. 3a, b), PE2 showed efficiencies of 17.7%, 20.4%, and 9.1% for 1 nt, 2 nt, and 3 nt deletions, while aPE2 showed that of 38.3%, 42.3%, and 12.5%, respectively. However, aPE2 exhibited lower activity for 4 nt, 5 nt, and 6 nt deletions compared to PE2, suggesting that aPE2-mediated deletions might also be position-dependent. Meanwhile, most unintended indels by aPE2 considerably decreased (Fig. 3c). Similar results were observed at HEK2 (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), HEK5 (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d), and HEK6 (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f) targets, even though there were some distinction about the enhancement potency.

a Alignment of the HEK3 reference sequence and representative deletion variants spanning from the +1 position to +6. Numbers above the reference indicate positions relative to the SpCas9 nicking site. Dashed lines represent deleted nucleotides in each variant. b Editing efficiency of PE and aPE2-induced deletions at HEK3 site. c, Indels formation of PE and aPE2-induced deletions at HEK3 site. d Comprehensive editing efficiency comparison of PE2 and aPE2-induced deletions for edits of HEK2, HEK3, HEK5, and HEK6. e Comprehensive indels comparison of PE2 and aPE2-induced deletions for edits of of HEK2, HEK3, HEK5, and HEK6. f Alignment of the HEK3 reference sequence and representative insertion variants at +1 position, with inserted sequences ranging from 1 to 6 nucleotides. Numbers above the reference indicate positions relative to the SpCas9 nicking site. Inserted nucleotides are shown in red for clarity. g Editing efficiency of PE and aPE2-induced insertions at HEK3 site. h Indels formation of PE and aPE2-induced insertions at HEK3 site. i Comprehensive editing efficiency comparison of PE2 and aPE2-induced insertions for edits of HEK2, HEK3, HEK5, and HEK6. j Comprehensive indels comparison of PE2 and aPE2-induced insertions for edits of of HEK2, HEK3, HEK5, and HEK6. All experiments were conducted in HEK293T cells. The data in (b, c, g, h) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The comprehensive analysis revealed that the average aPE2-introduced deletion efficiencies of 1 nt, 2 nt, and 3 nt were 1.73-fold, 1.68-fold, and 1.14-fold of PE2, respectively (Fig. 3d). While PE2 exhibited higher activity than aPE2 in the deletions of 4 nt, 5 nt, and 6 nt. This position-dependent augmentation was highly similar to that observed in base conversion edits, although the latter were achieved by aPE2 with greater efficiency than PE2 at the +1 to +4 positions within the targets. Consistently, aPE2 only showed 0.31-fold, 0.39-fold, 0.57-fold, 0.30-fold, 0.36-fold, and 0.42-fold of indels formation compared to PE2 accompanying the deletions of 1 nt to 6 nt (Fig. 3e), confirming that AcrIIA5 was also highly effective in reducing unintended by-products during deletions.

Previous results validated that the closer a PE-mediated edits was to the +1 position within the target, the more likely it was to be augmented by AcrIIA5 (Figs. 1g, 3d). We then attempted to insert DNA fragments of varying lengths at the +1 position within four different targets. Excellently, most aPE2-mediated insertions at the +1 position showed obvious improvement compared to PE2 (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 7g–i), and all indels were also reduced simultaneously (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 7j–l). The comprehensive analysis showed that the average aPE2-introduced insertion efficiencies of 1 nt to 6 nt were 1.92-fold, 1.37-fold, 1.36-fold, 1.30-fold, 1.24-fold, and 1.14-fold, respectively, compared to PE2 (Fig. 3i), indicating the strong potency of AcrIIA5, although its effectiveness decreased as the length of the inserted fragments increased. Persistently, all insertions by aPE2 decreased to an average of 0.43-fold compared to PE2 (Fig. 3j).

Examination of pathogenic mutations introduced by aPE

PE enables the precise introduction of base conversions, insertions, and deletions, making it highly promising for correcting genetic errors, albeit with limitation of low activity and increased indels when applying PE3 construct. Our previous results showcased that the aPE system possessed strong activity and exceptional security. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate aPE system in manipulating 12 pathogenic mutations21 including both base conversions and deletions.

The results showed that aPE2 exhibited 1.14- to 8.21-fold higher efficiency compared to PE2 in installing a half pathogenic mutation, represented by DMD, c.7098+1G-to-T (Fig. 4a). However, the efficiency of the other half of the mutations was not significantly improved by aPE2. In addition, we observed that the indels in 10/12 edits were reduced by aPE2 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). The holistic statistics showed that aPE2 improved editing efficiency and reduced indels in 50% of the pathogenic mutations (6/12), while 25% of the mutations (3/12) had unchanged efficiency but also reduced indels (Fig. 4b), which meant that aPE2 improved the performance of 75% of the tested pathogenic mutations.

a Installation efficiencies of 12 pathogenic edits induced by PE2 and aPE2. b Analysis of aPE2-induced outcomes compared to PE. “Change” columns mean the fold change of editing efficiency and indels induced by aPE2 compared to those induced by PE2. Editing efficiencies of PE and aPE-induced installation of DMD, c.5287 C > T (c) and NF1, c.1059del (d). All PEs except PE4 were constructed based on PE2 architecture. Evaluation of PE2 and aPE2 activities across different human cell lines. Editing efficiencies of PE2 and aPE2 were measured at two edits (HEK2, +2 G-to-A and HEK3, +1 T-to-A) in HeLa cells (e) and U2OS cells (f). g Schematic illustration of LNP formulations used for delivering PE components (Right). mRNA encoding PE2ΔRNaseH or aPE2ΔRNaseH (co-expressing AcrIIA5) and pegRNA were encapsulated into LNPs for cellular delivery. Editing outcomes using LNP-mediated delivery of PE2 or aPE2 at varying ratios of AcrIIA5 mRNA (0.5-fold and 0.1-fold relative to PE2ΔRNaseH mRNA) (Left). h Schematic of the hPCSK9-intron 1 target site, which is boxed in red dashed lines. i Editing efficiencies (+1 G-to-A) and indels frequencies caused by LNP-PE and LNP-aPE in HepG2 cells. j Secreted PCSK9 protein levels measured by ELISA following editing. k Cellular uptake of Dil-LDL was quantified by flow cytometry, and values were normalized to the control group which was treated with buffer. The data in (a, c–g, i–k) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. P values were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common pediatric neuromuscular disorder, caused by mutations in the largest gene in the human genome, the dystrophin gene43. To further explore the therapeutic potential of aPE system, we attempted to evaluate the efficiency of various aPE variants in correcting the DMD, c.5287 C > T mutation, which converted the 1763rd. amino acid in the dystrophin protein to a stop codon (Fig. 4c). The results exhibited that PE6c had the highest initial editing efficiency of 1.51% and increased to 2.75% with a 1.82-fold enhancement by aPE6c. PE2ΔRNaseH showed an efficiency of 0.69% and increased to 4.49% with the assistance of AcrIIA5, the highest among tested aPE variants, with a 6.56-fold improvement. Meanwhile, all tested aPE variants showed decreased indels (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

Besides, we also examined the installation of NF1, c.1059del mutation related to neurofibromatosis44, by PE or aPE system. The results showed PE6c possessed higher editing efficiency (12.5%) than PE2 (7.4%), and was further enhanced to 17.45% by aPE6c (Fig. 4d). Similar to DMD, c.5287 C > T mutation, the aPE2ΔRNaseH showed the highest editing efficiency of 18.4%. Among them, most edits also exhibited reduced indels by aPE variants, albeit not as pronounced as observed in base conversion type (Supplementary Fig. 8c).

Overall, the aPE systems exhibited excellent performance in installing pathogenic mutations, especially aPE2ΔRNaseH. Additionally, previous results confirmed that aPE functioned effectively in a position-dependent manner rather than in a editing type-dependent manner (Fig. 1h and Fig. 3d), thus the efficiency of installing pathogenic mutations also highlighted the potential in treating according genetic errors.

Assessment of the aPE generalizability in different cell lines

To explore whether the improved performance of the aPE system extends to other cellular contexts, we tested it in additional human cell lines, specifically HeLa and U2OS, by transfecting them with either PE2 or aPE2 systems. Targeted amplicon sequencing at HEK2, +2 G-to-A (Fig. 4e) and HEK3, +1 T-to-A (Fig. 4f) demonstrated that aPE2 consistently achieved higher intended editing efficiencies while maintaining comparable or lower indel frequencies compared to PE2 in both cell lines. These results indicated that the aPE system retains its enhanced performance across different cellular backgrounds, highlighting its broad applicability and potential for diverse biomedical applications.

AAV delivery evaluation of aPE

AAVs are clinically verified and FDA approved for in vivo gene editing applications45. Recent reports shown that PE2 can be divided into two parts and then reconstituted into intact functional PE2 through intein-based trans splicing46. Encouraged by this strategy, we splitted PE2ΔRNaseH and fused it with Npu-intein, then packaged them into AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2 vectors (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Meanwhile, we also constructed AAV_AcrIIA5 containing AcrIIA5 under CMV promoter.

By co-transducting the AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2 into HEK293T cells, we observed the +1 T-to-A editing efficiency of 2.97% at HEK3 target (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Upon adding a high concentration of AAV_AcrIIA5 containing AcrIIA5, the editing efficiency was suppressed to a minimal level. As the concentration of AcrIIA5 gradually decreased, the efficiency increased to 3.00% at 5−5 molar ratio. However, we did not observe any enhancement of PE2 by AcrIIA5. We hypothesized that the split PE2 protein required enough time to reassemble into a functional enzyme; thus, early expression of AcrIIA5 might hinder this process. Therefore, we attempted to add AcrIIA5 12 h after the delivery of AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2. As the concentration of AcrIIA5 decreased, the previously suppressed editing efficiency gradually increased, reaching a peak of 3.73% at 5−5 molar ratio, which was 1.33-fold higher than the PE2 efficiency of 2.80% (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Although delaying AcrIIA5 addition partially restored editing efficiency in the split PE2 system, the overall enhancement remained modest. This result suggested that the reassembly process might still limit the full benefit of AcrIIA5 when using AAV-based delivery. To address this constraint and better leverage the full potential of AcrIIA5, we next explored an alternative delivery strategy using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs).

LNP delivery evaluation of aPE

Unlike AAVs, LNPs allow direct cytoplasmic delivery of full-length mRNA, eliminating the need for protein splitting and subsequent intein-mediated reconstitution. This method enables immediate translation of the complete PE complex, which could minimize premature interactions with AcrIIA5 and maximize editing performance.

We first in vitro transcribed full-length PE2ΔRNaseH and AcrIIA5 mRNAs and encapsulated them with pegRNA in LNPs for co-delivery into HEK293T cells (Fig. 4g). Our results demonstrated that LNP-mediated delivery of PE2ΔRNaseH mRNA alone resulted in an intended editing efficiency of 7.5% at the HEK3, +1 T-to-A edit. When co-delivered with AcrIIA5 mRNA at molar ratios of 0.5 and 0.1 relative to PE2ΔRNaseH, the editing efficiency of the aPE2 system increased to 11.1% (1.48-fold of PE2ΔRNaseH) and 13.5% (1.80-fold of PE2ΔRNaseH), respectively, representing a notable enhancement compared to PE2ΔRNaseH alone. Moreover, the frequency of undesired indels was consistently lower in the aPE2ΔRNaseH groups than in the PE2ΔRNaseH-only group. These results suggest that LNP-based delivery of the full-length aPE system is both feasible and effective, enhancing its therapeutic potential.

Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and gain-of-function mutations or elevated expression of PCSK9 (Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9) have been firmly established as key drivers of impaired LDL clearance through enhanced degradation of LDL receptors (LDLRs)47. Therapeutic strategies that disrupt PCSK9 function have shown substantial clinical benefit, underscoring this gene as a highly relevant target for evaluating genome editing tools47. To assess the therapeutic potential of the aPE system, we examined its performance at the PCSK9 locus in hepatocyte HepG2 cells. We selected the intron 1 splice donor site GT for introducing a + 1 G-to-A mutation to disrupt the PCSK9. The results showed that LNP-delivered PE (mRNA-PE2ΔRNaseH) achieved a + 1 G-to-A substitution with an efficiency of 8.9%, whereas LNP-aPE (co-delivery of AcrIIA5 and PE2ΔRNaseH mRNAs at a 0.1:1 ratio) markedly improved the editing efficiency to 24.7%, while maintaining low indels (Fig. 4i). This precise disruption of the GT splice donor site resulted in a functional knockdown of PCSK9. ELISA analysis showed that secreted PCSK9 protein levels caused by LNP-aPE were reduced by 32.6% relative to the control group and by 21.3% compared with LNP-PE treatment (Fig. 4j). Functionally, this translated into enhanced LDL clearance, as measured by flow cytometry with fluorescently labeled Dil-LDL. Compared with controls, LNP-PE increased LDL uptake by 8.5%, while LNP-aPE further boosted Dil-LDL internalization by 18.0%, proving that LNP-aPE editing of PCSK9 could effectively restore the capacity for LDL metabolism in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 10). Together, these results demonstrated that the LNP-aPE system can precisely and efficiently disrupt PCSK9 splicing in hepatocyte-derived cells, leading to a tangible reduction of PCSK9 activity and improved LDL uptake. Considering the critical role of PCSK9 in hypercholesterolemia, these results highlight the translational promise of aPE for therapeutic editing at clinically relevant loci.

PBS is not the determinant of aPE activity

While the above results confirmed that the aPE system can enhance editing efficiency across multiple delivery strategies, we also observed that its effect varied at certain target sites. To better understand the factors underlying this variability, we further investigated the sequence and thermodynamic properties associated with aPE activity. We first analyzed the maximum fold increase of aPE (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). The results indicated that when a target showed Tm value between 50 to 55 °C, the PE efficiency was more likely to be enhanced by AcrIIA5. Conversely, when target characterized with Tm value around 65°C, the PE efficiency can not be enhanced by AcrIIA5 and may even be inhibited.

In fact, since the PBS sequence in pegRNA is partially complementary to the spacer, the modulation of PE system activity by AcrIIA5 might also be related to PBS (Supplementary Fig. 11c). To test this hypothesis, we adjusted the PBS length in pegRNAs responsible for HEK3 + 1 T-to-A (Supplementary Fig. 11d), HEK2 + 4 G-to-A (Supplementary Fig. 11e), and HEK2 + 5 G-to-A (Supplementary Fig. 11f) to alter their Tm values. The results showed that varying the PBS length led to different changes in PE editing efficiencies for these edits. However, the effect of AcrIIA5 in enhancing or inhibiting these edits remained consistent, though the degree of the effect varied slightly. Notably, indels were significantly reduced across all edits (Supplementary Fig. 11g–i). These findings confirmed that altering the PBS length did not obviously affect AcrIIA5’s ability to regulate PE activity, thereby alleviating constraints in pegRNA design when using aPE.

RTT is not the determinant of aPE activity

As previously mentioned, the regulation of PE-mediated base conversions by AcrIIA5 was position-dependent, aligning with the statistical findings that the edited base closer to +1 position was more likely to be improved by AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 11j). In fact, we have defined a fixed 14 nt RTT length when designing pegRNA. Thus, the base edited at a specific position also indicated a corresponding RHA (Right homology arm) (Supplementary Fig. 11a), meaning that PE activity with longer RHAs were more possible to be enhanced by AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 11j). To examine this hypothesis, we altered the RHA lengths for several PE-mediated edits, expecting that shortening the RHA might suppress edits originally enhanced by AcrIIA5, while extending the RHA might boost edits originally inhibited by AcrIIA5.

However, the results showed that neither extending nor shortening the RHA obviously altered AcrIIA5’s regulatory effect on the respective edits, whether they were base conversions (Supplementary Fig. 11k, i and Supplementary Fig. 12a–f) or DNA deletions (Supplementary Fig. 12g, h). We also observed that the indels decrease caused by aPE was not significantly affected by varying RHA lengths (Supplementary Fig. 12). These findings indicated that RHA length in pegRNA was not a determining factor in AcrIIA5’s regulation on PE activity, suggesting that RTT length did not need to be a concern when designing pegRNAs for aPE systems.

Mechanistic insights into the position-dependent effect of aPE

Since we have confirmed that the pegRNA composition is not the determinant of aPE activity, we put our focus on the position itself. Specifically, the key issue lies in explaining the observed phenomenon that PE2 exhibits higher editing efficiency at the +1 to +3/ + 4 positions, but significantly lower efficiency at the +5 or +6 positions. Considering that protein abundance might directly influence PE outcomes, we first examined the expression levels of PE2 protein in the presence or absence of AcrIIA5 using Western blot analysis at the HEK2 locus across the +1 to +6 positions (Supplementary Fig. 13). The results showed that aPE2 exhibited expression levels comparable to those of PE2 across +1 to +6 positions, indicating that AcrIIA5 does not interfere with PE2 protein expression. Therefore, the changes in editing efficiency observed between PE and aPE systems are not attributable to differences in protein abundance.

Next, considering that the aPE system exhibited a sharp decrease in editing activity at the +5 and +6 positions, which correspond to the PAM sequence, we guessed that edits within or outside the PAM region might differentially influence aPE activity. To test this hypothesis, we further evaluated the impact of AcrIIA5 co-expression on PE2 at PAM downstream positions, specifically from +7 to +14, at the HEK2 locus (Fig. 5a, b). Interestingly, the editing efficiencies of aPE2 were consistently higher than that of PE2 across all positions in this region. Besides, we also examined aPE2-mediated insertions and deletions at positions downstream of the PAM sequence. The results showed that aPE2 consistently achieved higher activity than PE2 for these edits as well (Supplementary Fig. 14).

a Base conversion efficiencies of PE2 and aPE2 at positions +7 to +14 at the HEK2 locus. b Indel at the same +7 to +14 positions as in (a). c Editing efficiencies of single-base conversions at positions +1 to +5 at the HEK2 locus. d, Editing efficiencies at positions +1, +2, +3, and +4 when co-edited with a + 5 G-to-A substitution at the same locus, representing conditional base conversions. e Base conversion efficiencies at the +5 position using SpCas9-PE2 (N+4G+5G+6 PAM) and SpG-PE2 (N+4G+5N+6 PAM), with or without AcrIIA5. f Base conversion efficiencies at the +6 position under the same conditions as in (e). g Proposed mechanism for AcrIIA5 enhance PE activity. In the PE system (left), the edited strand remains susceptible to re-cleavage by SpCas9 after the initial editing event. In contrast, in the aPE system (right), co-expression of AcrIIA5 partially inhibits SpCas9 activity, thereby reducing re-cleavage of the edited strand. h Correlation between DeepSpCas9 scores and aPE:PE fold change. i Editing efficiencies of PE and aPE systems at the selected loci with high or low DeepSpCas9 score. All experiments were conducted in HEK293T cells. The data in (a–f) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, we examined the combined effects of PAM-proximal and PAM-silencing edits (Fig. 5c, d). When only PAM-proximal positions (+1 to +4) were edited, aPE2 showed higher efficiency than PE2. In contrast, at the PAM-silencing position (+5), the editing efficiency of aPE2 was lower than that of PE2. Notably, when PAM-proximal edits were introduced together with a PAM-silencing mutation, the editing efficiency of aPE2 was significantly reduced compared to PE2. These findings suggest that PAM-silencing edits may be a key factor influencing the editing outcome of the aPE system. To probe this hypothesis in more detail, we utilized SpG, an engineered variant of SpCas9 that recognizes a relaxed N+4G+5N+6 PAM, to construct an SpG-based PE2 system with expanded targetable regions. We then evaluated the editing outcomes of both SpCas9-PE2 (mainly N+4G+5G+6 PAM and slightly N+4G+5A+6 PAM) and nSpG-PE2 at the +5 and +6 positions (Fig. 5e, f).

Consistent with our previous findings, the editing efficiency of SpCas9-aPE2 at both +5 and +6 positions was lower than that of SpCas9-PE2. For the nSpG-based system, aPE2 exhibited lower editing efficiency than PE2 at the +5 position, but higher efficiency at the +6 position. This contrasting outcome observed in the nSpG-based system is consistent with its recognition of the N+4G+5N+6 PAM. These observations suggest that PAM-silencing edits are critical modulators of aPE activity and raise the possibility that their position relative to the PAM influences re-targeting dynamics and editing efficiency.

We then attempted to establish a model to explain the mechanism of the aPE system. Previous studies have demonstrated that PAM-silencing edits can enhance PE activity and reduce undesired indel byproducts, presumably by preventing re-recognition and re-nicking of the edited strand19. Such re-nicking can lead to reversion of the desired edit or promote indel formation, especially in the context of PE3 systems. Inspired by these findings, we speculated that the activity of aPE might also be influenced by a similar prevention of re-nicking mechanism. Specifically, for PAM-proximal or distal edits, AcrIIA5 may suppress SpCas9-H840A nicking activity just enough to slow re-targeting of the edited strand, without completely abolishing the initial nicking required for initiating the PE process (Fig. 5g). Moreover, once the intended mutations are installed, the edited targets may exhibit reduced binding affinity for the original SpCas9-H840A-pegRNA complex due to sequence mismatches within the spacer region, making them more resistant to re-targeting and potentially further delaying re-nicking in the presence of AcrIIA5. In contrast, for PAM-silencing edits, the inhibition provided by the PAM mutation itself may already be sufficient to prevent re-nicking. Thus, the additional suppression from AcrIIA5 could overly weaken the initial nicking activity, thereby reducing the overall editing efficiency.

Based on this model, we hypothesized that the performance of aPE is closely tied to the intrinsic DNA cleavage activity of SpCas9 at each tested target site. At loci with high cleavage activity, initial nicking is more likely to occur even in the presence of AcrIIA5, allowing the PE process to proceed efficiently. In such cases, AcrIIA5 may primarily function to suppress excessive re-nicking, thereby enhancing editing precision and efficiency. Conversely, at sites with low SpCas9 activity, AcrIIA5 may overly inhibit nicking, ultimately reducing editing efficiency.

To examine this hypothesis, we next sought to determine whether a correlation exists between SpCas9 cleavage activity and aPE performance. Given that in vitro SpCas9 cleavage assays may not accurately reflect chromatin accessibility and other cellular factors influencing cleavage efficiency in vivo, we turned to a cell-based predictive approach. We utilized DeepSpCas9, a deep learning model which predicts SpCas9 cleavage activity across thousands of genomic loci in HEK293T cells48. By inputting the sequences of our tested loci into this model, we obtained predicted cleavage scores (Fig. 5g), where higher scores indicate stronger SpCas9 activity in cellular contexts. By correlating the DeepSpCas9 scores with the observed fold change in editing efficiency between aPE and PE systems (aPE:PE ratio) (Fig. 5h), we found a strong association that higher predicted SpCas9 activity scores generally linked to greater enhancement by AcrIIA5. Specifically, at target sites with DeepSpCas9 scores above 50, aPE consistently outperformed PE. In contrast, at sites with scores below 50, aPE often showed reduced efficiency compared to PE.

To further validate this correlation, we selected an additional set of four loci with predicted DeepSpCas9 scores >50 and four with scores <50 (Fig. 5i). The results showed that all four high-score loci exhibited enhanced editing efficiency with aPE compared to PE, whereas all four low-score loci showed reduced aPE activity. These findings support the conclusion that the performance of aPE is indeed influenced by initial SpCas9 cleavage activity at the target locus, and that DeepSpCas9 scores can be prospectively used to guide target selection, thereby improving the predictability and applicability of aPE in practical genome editing scenarios.

Molecular basis of AcrIIA5-mediated enhancement of PE activity

We have preliminarily demonstrated the relationship between SpCas9 cleavage activity and aPE performance, but the underlying mechanism remains uncertain. To further explore the molecular basis of this observation and validate our proposed model, we focused on dissecting the individual contributions of SpCas9 and AcrIIA5 to aPE function. As is well known, the generation of indels in the PE system is directly linked to the cleavage activity of SpCas9-H840A. For example, further reducing the cleavage activity of SpCas9-H840A on the non-edited strand significantly decreases indels byproduct49, whereas introducing additional cleavage on the non-edited strand, as in the PE3 architecture, markedly increases indels. Consistent with this, we observed that AcrIIA5 significantly suppressed PE-associated indels across various edits, confirming its inhibitory effect on SpCas9-H840A cleavage. To clarify this, we systematically tested conditions altering the nickase and RT functions. We replaced the SpCas9-H840A with SpCas9-H840A + D10A (dCas9) and Cas9, or discarded the RT in PE2 protein. At HEK5 + 2 C-to-T edit (Fig. 6a), the presence of AcrIIA5 suppressed the indels, confirming AcrIIA5’s inhibitory potency on SpCas9. Furthermore, when SpCas9-H840A was replaced with dCas9, no obvious +2 C-to-T conversion efficiency was observed, regardless of the presence of AcrIIA5, indicating that the enhancement of PE efficiency by AcrIIA5 occurred after the cleavage of the edited strand. We also observed that SpCas9 efficiency was significantly suppressed by AcrIIA5 (from 10.95% to 5.89%), and accordingly, the PE efficiency based on SpCas9 also slightly declined (from 4.09% to 3.31%). However, only when SpCas9-H840A was combined with RT did AcrIIA5 enhanced editing efficiency (from 1.22% to 6.37%) while simultaneously reducing indels (from 0.65% to 0.41%). Similar results that aPE worked only in the presence of SpCas9-H840A and RT were observed in another event at the HEK5 + 6 G-to-T edit (Fig. 6b). These findings confirmed that AcrIIA5 enhances PE activity only when the edited strand is nicked and reverse transcription can proceed, demonstrating that its enhancement effect coexists with its suppression of SpCas9 cleavage.

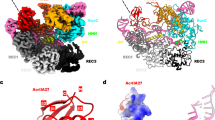

Editing efficiencies and indels of gene editing tools with or without AcrIIA5 for HEK5, +2 C-to-T (a) and HEK5, +6 G-to-T (b). Editing efficiencies and indels of PE2 with different anti-CRISPR proteins for HEK5, +2 C-to-T (c) and HEK5, +6 G-to-T (d). The molar ratio of Acrs:PE2 was 1:1. e Editing efficiencies of AcrIIA5 mutants with stepwise N-terminal deletions and positive-charge residue substitutions in the IDR region, co-expressed with PE2. f Editing efficiencies of AcrIIA5 mutants with point mutations in residues surrounding the α3–α4 loop, co-expressed with PE2. g Mutational rescue screen of individual residues within the 18-amino-acid region that differs between AcrIIA5 and AcrIIA5-D1126. Each mutant was co-expressed with PE2 and tested for the HEK2, +2 G-to-A edit. h Structural model of AcrIIA5. Functionally critical residues identified in (e–g) are highlighted in red and are clustered on one side of the protein. Red dashed lines in (e–g) indicate the editing efficiency of PE2 in the absence of AcrIIA5 co-expression. All experiments were conducted in HEK293T cells. The data in (a–g) were obtained from n = 3 independent biological replicates. Bars represent mean ± s.d. P values were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Given that the enhancing effect of AcrIIA5 on PE efficiency depends on the precise balance between SpCas9 nicking and inhibition, we next sought to investigate whether AcrIIA5 preferentially targets a specific nuclease domain of SpCas9 to exert its regulatory function. Understanding this interaction could help explain how AcrIIA5 selectively reduces undesired indels while still permitting sufficient nicking to enable reverse transcription. To this end, we designed a series of biochemical experiments using SpCas9 variants with distinct catalytic activities (Supplementary Fig. 15). Specifically, we purified wild-type SpCas9, SpCas9-D10A (HNH-active, RuvC-inactive), SpCas9-H840A (RuvC-active, HNH-inactive), and AcrIIA5, and reconstituted SpCas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes with each SpCas9 variant. These RNPs were incubated with a supercoiled pUC57 plasmid substrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of AcrIIA5 (at molar ratios of 0, 0.1, 1.0, and 10 relative to SpCas9). In the absence of AcrIIA5, wild-type SpCas9 mainly converted the supercoiled (SC) plasmid into the linear (LIN) form. Similarly, SpCas9-D10A nicked the targeted strand, producing predominantly open circular (OC) DNA, while SpCas9-H840A, which nicks the opposite strand, also generated OC products, albeit with slightly different efficiency. Upon titration of AcrIIA5, we observed a progressive reduction in cleavage/nicking activity for wild-type SpCas9 and SpCas9-H840A.

At a 1:1 molar ratio of AcrIIA5 to SpCas9, both enzymes exhibited a considerable suppression of activity, with most DNA remaining in the SC form. This indicates effective inhibition of both double-strand cleavage and RuvC-mediated nicking. In contrast, SpCas9-D10A retained substantial nicking activity even at AcrIIA5 molar ratios of 0.1 and 1.0, and only at the highest ratio (10:1) did we observe notable reduction in OC product formation. These results suggest that the RuvC domain is more susceptible to AcrIIA5 inhibition than the HNH domain, supporting our hypothesis that AcrIIA5 fine-tunes PE activity by selectively dampening redundant re-nicking events while preserving the initial nicking required to initiate prime editing.

Moreover, the phenomenon that SpCas9-H840A exhibited progressively reduced but not fully abolished nicking activity inhibited by AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 15c), as evidenced by the persistent presence of nicked OC plasmid, indicates that AcrIIA5 cannot completely inhibit SpCas9-H840A. This finding is precisely consistent with our proposed aPE mechanistic model (Fig. 5g), in which such “soft” inhibition is sufficient to prevent excessive re-nicking of the newly edited NTS while still permitting residual nicking of unedited DNA strands to initiate prime editing.

Furthermore, to determine whether this mechanism is unique to AcrIIA5, we tested other anti-CRISPR proteins with distinct inhibition modes. For example, AcrIIA1 reduced SpCas9 activity by degradation50; AcrIIA251 and AcrIIA452 both blocked binding of SpCas9 and target DNA binding by occupying the PAM-interaction region. We applied these Acrs to regulate PE performance and tested them at the HEK5 + 2 and +6 conversion edits. Additionally, we tested AcrIIA5-D1126, which shared 87% homology with AcrIIA5.

The results showed that AcrIIA1 and AcrIIA4 consistently and strongly inhibited PE efficiency at both the +2 and +6 positions, while AcrIIA2 exhibited a weaker inhibitory effect (Fig. 6c, d). Surprisingly, AcrIIA5-D1126 suppressed the +2 C-to-T conversion, whereas AcrIIA5 enhanced this conversion by 1.41-fold. However, AcrIIA5 reduced the +6 G-to-T conversion efficiency from 8.6% to 0.4%, and AcrIIA5-D1126 also lowered this efficiency to 0.8%. Comparatively, AcrIIA5-D1126 decreased the efficiency at the +2 position by 26.4% and at the +6 position by 91.3%, indicating that the activity of AcrIIA5-D1126 was also position-dependent like AcrIIA5. Sequence alignment revealed that the most significant distinction between AcrIIA5 and AcrIIA5-D1126 lied in the N-terminal intrinsically disordered region (IDR) and the α1 region (Supplementary Fig. 16), which have been shown to influence the inhibition of AcrIIA5 to SpCas926, suggesting that they may play a critical role in regulating PE activity, especially considering the starkly different PE editing outcomes by AcrIIA5 and AcrIIA5-D1126. These findings strongly support that AcrIIA5 promotes PE efficiency through its canonical SpCas9 inhibition pathway, which appears to be distinct from other Acr proteins tested.

To pinpoint the specific regions responsible for this effect, we next performed mutational analyses of both AcrIIA5 and SpCas9. We performed a split-function mutation analysis of SpCas9 and AcrIIA5 to investigate whether the observed enhancement of PE2 activity is driven by their interaction. Although no structural complex of SpCas9 and AcrIIA5 has been reported to date, previous studies have identified two key regions through which AcrIIA5 inhibits SpCas926. They include the positively charged N-terminal IDR and α1 helix, and the loop between α3 and α4 along with the surrounding region.

We first conducted stepwise deletions of the N-terminal IDR (Fig. 6e). While short deletions did not significantly impact the function of AcrIIA5, the AcrIIA5Δ7 mutant exhibited a significantly reduced enhancement of PE2 activity compared to wild-type AcrIIA5, indicating that the N-terminal IDR plays a critical role in modulating PE2 activity.

Next, we replaced the positively charged residues with alanine inside IDR. The AcrIIA5KR and AcrIIA5RK mutants showed a modest reduction in their ability to enhance PE2 activity, whereas the AcrIIA5RKR mutant almost completely lost its enhancing effect and even impaired PE2 editing efficiency (Fig. 6e). These findings are consistent with previous in vitro SpCas9 cleavage assays26, which showed that RKR mutations or extended deletions within the IDR abolish the inhibitory function of AcrIIA5, indicating that effective SpCas9 inhibition is essential for its enhancement of PE activity. Furthermore, as reported24, mutations within or near the α3–α4 loop region also abolish AcrIIA5’s inhibitory function. We also introduced alanine substitutions in this region (Fig. 6f), and the resulting mutants showed a marked decrease in aPE2 activity.

Interestingly, we observed a concurrent decline in both editing efficiency and indel suppression when the activity of aPE2 was reduced, suggesting that mutations weakening AcrIIA5’s inhibitory function compromise its dual role in enhancing editing and minimizing byproducts of PE system (Supplementary Fig. 17). In summary, our data confirm that mutations previously shown to disrupt AcrIIA5’s inhibition of SpCas9 in both biochemical and cellular settings also markedly reduce its ability to enhance PE activity. This parallel loss of function indicates that the enhancement of PE activity by AcrIIA5 fundamentally relies on its inhibitory interaction with SpCas9. Thus, although AcrIIA5 appears to act as an enhancer in the context of PE, its effect ultimately stems from its canonical role as a SpCas9 inhibitor.

Additionally, to identify residues critical for the PE2-enhancing function of AcrIIA5, we performed single-point reversion mutations on AcrIIA5-D1126, which differs from wild-type AcrIIA5 by 18 amino acids (Fig. 6g). We aimed to determine whether specific mutations could restore its ability to enhance PE2 activity. The results revealed that K28Q, K29E, and K31D were key mutations that significantly improved the activity of AcrIIA5-D1126 toward wild-type AcrIIA5 levels. When mapping all three functional regions onto the 3D structure of AcrIIA5, we found that they are spatially clustered on the same surface. This observation suggested that these residues may contribute to the interaction with SpCas9 and its subsequent inhibition (Fig. 6h).

To further investigate the key regions in SpCas9 that mediate its interaction with AcrIIA5, we sought to identify specific residues involved in this response. Both our results (Fig. 6e, f) and previous studies26 have demonstrated that positively charged residues in the IDR region of AcrIIA5 are critical for its inhibitory activity. Moreover, our in vitro cleavage assays indicated that the RuvC domain of SpCas9 is likely the primary target of AcrIIA5. Based on this, we hypothesized that AcrIIA5 may interact with negatively charged regions within the RuvC domain through electrostatic forces. To test this, we generated alanine substitutions at a series of candidate acidic residues in the RuvC domain, specifically aspartic acid (D) and glutamic acid (E), and evaluated PE2 editing efficiency with or without AcrIIA5 (Supplementary Fig. 18). Unexpectedly, none of these mutations obviously affected the ability of AcrIIA5 to modulate PE2 activity, suggesting that the tested residues are unlikely to be directly involved in the interaction. This finding indicates that the binding interface between AcrIIA5 and SpCas9 is more complex than initially anticipated, and future studies using high-resolution structural analysis or systematic mutagenesis will be needed to clarify the precise mechanism of AcrIIA5-SpCas9 recognition.

Discussion

Phage-derived anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins have long been recognized as potent inhibitors that phages deploy to counteract bacterial CRISPR/Cas immunity22. Among them, AcrIIA5 is widely known as an effective inhibitor of SpCas9 and its derivative base editors23,24,25,26,27. Strikingly, our study demonstrates that the canonical SpCas9 inhibitor AcrIIA5 can paradoxically serve as a robust enhancer of the PE system, which is unlike the natural “enhancer” PcrIIC1 that boosts the activity of Chryseobacterium Cas953, thus broadening the functional landscape of Acr proteins. Specifically, we showed that AcrIIA5 can boost PE activity by up to 8.2-fold for base substitutions, 3.2-fold for DNA fragment insertions, and 5.2-fold for DNA fragment deletions, while simultaneously reducing undesired indels to minimal levels. This dual role highlights AcrIIA5 as a simple yet powerful modulator for enhancing the precision and efficacy of PE system.

Mechanistically, our results suggest that AcrIIA5 enhances PE efficiency by suppressing redundant re-targeting and re-nicking events while preserving the initial nick required to initiate reverse transcription. Notably, this effect is not determined by the distance from the nick site but rather by whether the edit disrupts the PAM. For non–PAM-silencing edits, including both PAM-distal and PAM-proximal edits, AcrIIA5 consistently increases PE editing efficiency and reduces undesired indels. In contrast, PAM-silencing edits already block re-nicking, and the addition of AcrIIA5 may overly suppress SpCas9-H840A activity, thereby reducing PE editing efficiency.

In practical applications, the small size of AcrIIA5 makes it particularly suitable for use with delivery systems that have limited cargo capacity. Our experiments confirmed that the aPE system can be efficiently delivered through LNP-mediated co-delivery of full-length mRNA, resulting in substantial improvements in editing efficiency in human cells while maintaining low unintended byproduct indels. In addition, the aPE system demonstrated broad compatibility with various PE architectures, from the classical PE2 to more advanced versions such as PE6 and the PAM-less SpRY-derived PE variant, indicating its flexible applicability across different editing strategies. Notably, aPE achieved reliable installation of pathogenic mutations, including disease-relevant edits in the DMD and NF1 loci, as well as efficient splice-disrupting editing at the PCSK9 locus, which collectively support its promising potential for future therapeutic genome editing.

Notably, our detailed indels profiling revealed two major classes of byproducts (Supplementary Fig. 19a). The first, commonly observed at sites such as HEK3 locus, consists primarily of small deletions occurring near the nick site, consistent with classical NHEJ repair. These deletion events were significantly suppressed upon AcrIIA5 application, indicating its ability to mitigate NHEJ-mediated damage of PE protein. The second class, more prominent at loci such as HEK2 locus, includes both small deletions and a notable frequency of unintended insertions. Sequence analysis revealed that many of these insertions correspond to partial reverse-transcribed RTT sequences, likely inserted at the nick site without displacing the original strand. This pattern suggests a failure of proper strand displacement during PE editing, followed by direct ligation of the RT product via NHEJ machinery (Supplementary Fig. 19b). This failure may be facilitated by a local GC-rich environment that stabilizes the original strand and impairs flap resolution. Importantly, AcrIIA5 also significantly reduced these aberrant insertion events, suggesting that it not only suppresses classical indel formation but may also act at earlier steps to prevent re-targeting or abnormal flap resolution. This dual suppression effect in aPE contributes to more accurate editing with fewer unintended genomic alterations. Furthermore, comprehensive off-target analyses demonstrated that aPE did not induce additional off-target edits beyond those observed with standard PE, indicating that AcrIIA5 does not compromise editing specificity (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Despite its robust performance, the aPE system has certain limitations. If AcrIIA5 is expressed at excessively high levels, it may strongly inhibit PE activity (Fig. 1d). Moreover, we observed that AcrIIA5 enhances PE efficiency to varying degrees across different target loci, and in certain cases, it even appears to reduce PE activity. While DeepSpCas9-guided selection helped identify target sites with higher predicted cleavage activity and generally improved aPE performance, some loci nonetheless displayed inconsistent editing outcomes under the predicted conditions. To address these challenges, we plan to perform large-scale efficiency testing of aPE across a broad range of genomic loci. The resulting dataset will provide a foundation for training specialized deep learning models to more accurately predict aPE activity at diverse target sites, thereby guiding more effective application of aPE across various genomic and therapeutic contexts. Additionally, we introduced point mutations at key residues of AcrIIA5 and performed reversion mutations on AcrIIA5-D1126, which together helped identify critical regions responsible for its activity. However, we were still unable to elucidate the fundamental molecular basis of how the AcrIIA5-SpCas9 interaction regulates the aPE system. We believe that future structural biology studies will be essential for uncovering this underlying mechanism.

Besides, we also found that the improvement in the insertion and deletion of genomic fragments by AcrIIA5 was only modest compared to that observed for base substitutions. We speculated that this is because, as previously observed, PAM-silencing edits significantly reduce aPE activity. Compared to single-nucleotide conversions, insertions and deletions inherently alter the length or structure of the target DNA sequence, which may have a greater impact on the PAM region and adjacent elements. This added structural complexity may limit the extent to which AcrIIA5 can enhance PE editing efficiency, resulting in a smaller improvement in insertions and deletions relative to substitutions.

In conclusion, our finding that AcrIIA5 can act not only as a Cas9 inhibitor but also as a potent enhancer of PE expands the functional scope of Acr proteins and reveals a promising direction for designing context-specific regulators of gene editing. Considering the wide diversity of both known and yet-to-be-characterized Acr families, it is reasonable to expect that further systematic exploration could identify additional Acr proteins capable of precisely modulating various CRISPR-based editing tools, ultimately facilitating safer and more effective therapeutic applications.

Methods

Plasmid cloning

Unless stated otherwise, cloning was performed using the Hieff Clone One Step Cloning Kit (YEASEN). The DNA fragments of AcrIIA1, AcrIIA2, AcrIIA4, AcrIIA5-D1126, AcrIIA5, hA3A, hA3Bctd, hA3Gctd, evoEc48, evoTf1, La, Npu intein, viral nucleocapsid protein, MLH1-SB, and sgRNA scaffolds of SpCas9 were synthesized by GenScript. PCR was performed using Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Vazyme). Site-directed mutagenesis of was performed using Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme).

The DNA fragments of hA3A, hA3Bctd, and hA3Gctd were amplified and cloned into the backbone of pCMV-BE311 (Addgene #73021) to construct CBEs. The DNA fragment of Acrs were amplified and cloned into the backbone of pcDNA3.1(-). The DNA fragments of evoEc48 and evoTf1 were amplified and cloned into the backbone of pCMV-PE219 (Addgene #132775) to construct PE6a and PE6c. The SpRY was cloned from RTW502554 (Plasmid #140003) to construct nSpRY-PE2ΔRNaseH. AAV vectors were constructed based on the backbone of pAAV-EFS-CjCas9-eGFP-HIF1a55 (Plasmid #137929). The sgRNA scaffolds of SpCas9 were cloned into pUC57 under the U6 promoter amplified from the PX459 v2.0 plasmid. Protospacer oligos were phosphorylated by PNK (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cloned into sgRNA expression plasmids by T4 DNA Ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The pegRNA 3’ extension sequences were added in sgRNA expressing plasmids by PCR. The amino acid sequences or nucleotide sequences were list in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2. All newly generated plasmids used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Culture condition and transfection

HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216), HeLa cells (ATCC CCL-2), and U2OS cells (ATCC HTB-96) were kept in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) in 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. HepG2 cells were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (CL-0103) and were kept in HepG2 cell complete medium (Procell, CM-0103).

Cells were seeded into 48-well plates (Corning) at a density of 55,000 cells per well and transfected 18 h after plating. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For each well, 500 ng of SpCas9, CBE, or PE expression plasmid (9753 bp for PE2), 200 ng of pegRNA or sgRNA expression plasmid (3200 bp), and a variable amount of AcrIIA5 expression plasmid (5869 bp) were co-transfected to achieve the desired molar ratio of AcrIIA5 relative to PE2. At a molar ratio of 0.1, the corresponding mass of AcrIIA5 plasmid is ~30 ng, while at a ratio of 3.0, it is ~900 ng. For PE3 conditions, the nicking sgRNA expression plasmid was also included at 200 ng per well. All plasmid ratios refer to molar amounts unless otherwise specified.

Production and transduction of AAV vectors

AAV vectors were packaged in AAVDJ capsids by OBiO Technology and validated using quantitative PCR. The vector titres were 5.82 × 1012, 1.02 × 1013, and 7.36 × 1012 v. g. /mL for AAV_PE_1, AAV_PE_2, and AAV_AcrIIA5, respectively. After diluting AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2 to 5.00 × 1010 and 5.00 × 1010 titres in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco), 10 µL of each was mixed and transduced into HEK293T cells that had been cultured in a 48-well plate to 50% confluence. AAV_AcrIIA5 was diluted to 3.00×1010 first and then serially diluted in 5-fold increments, then 10 μL of each was added to the wells containing HEK293T cells with AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2, either immediately or 12 h later. Besides, an equal volume of medium without AAV_AcrIIA5 was simultaneously added to the control wells containing AAV_PE_1 and AAV_PE_2 for control.

mRNA production and LNP delivery

mRNA of PE2ΔRNaseH and AcrIIA5 were synthesized using the T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit for Co-transcription (Yeasen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, plasmids harboring the coding sequence of PE2ΔRNaseH or AcrIIA5 were first constructed with an upstream inactivated T7 promoter, a 5’-untranslated region (UTR), and a Kozak sequence, as well as a downstream 3’-UTR. PCR was used to generate in vitro transcription templates by restoring the functional T7 promoter and appending a 115-nucleotide poly(A) tail downstream of the 3’ UTR. Then, linearized DNA templates containing the T7 promoter were used for in vitro transcription in a 20 μL reaction system, which included T7 RNA polymerase mix, transcription buffer, canonical and modified nucleotides (ATP, CTP, GTP, and N¹-methyl-pseudouridine-UTP), and a cap analog (GAG). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, and the reaction was treated with DNase I to remove the DNA template, and RNA was purified via lithium chloride precipitation. The RNA pellet was washed with cold ethanol, resuspended in RNase-free water, and quantified by UV spectrophotometry. RNA quality and integrity were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Chemically synthesized pegRNAs (GenScript) were modified with 2’-O-methyl and phosphorothioate linkages at the first three and last three nucleotides, and were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

mRNA and pegRNA was formulated into LNPs using the NeoLNP RNA transfection reagent (SDR8006, Scindy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 400 ng mRNA and 200 ng pegRNA complex were diluted with RNA dilution buffer to a final concentration of 40 ng/μL, and an equal volume of NeoLNP working reagent was added. The mixture was gently pipetted and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to allow complex formation. The resulting mRNA-pegRNA-NeoLNP complexes were then diluted in culture medium to a final mRNA concentration of 20 ng/μL and used immediately for cell transfection. Complexes were applied to cells and incubated under standard culture conditions for 72 h prior to downstream analysis.