Abstract

Cyclopropane-based aerospace fuels exhibit the excellent volumetric calorific value, leading to broad application prospects in aircrafts. However, due to the highly rigid structure of the cyclopropane (compared to cyclobutane or cyclopentane, etc.) and the difficulty in forming metal-carbene intermediates, there are still significant challenges in the precise synthesis of multi-cyclopropane-based high-energy fuels ( ≥ 2 cyclopropane structures). Herein, via the introduction of bending strain on metal organic complex, we report a single-site Cu/single-walled carbon nanotube catalyst (Cu/SWCNT), which possesses 2.6-fold conversion (up to 77.4%) and 4-fold selectivity (up to 45.7%) as that without bending strain for the preparation of bi-cyclopropane-based fuels from dienes. XAFS and DFT calculations show that bending strain enhances the upward shift of d-band center of β electrons (−4.370 to −4.366), thus promotes the adsorption and activation of CH2N2 and alkenes. Moreover, bending strain elongates Cu-O bonds (1.91 to 1.96 Å), making it easier for CH2N2 to insert and form Fischer carbene intermediates. These two aspects obviously reduce the reaction energy barrier from 40.3 to 33.7 kcal·mol-1 for the cyclopropanation process. Our work provides a method of strain engineering to regulate C-C coupling reactions at the molecular level, and achieve highly efficient cyclopropanation from alkenes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Construction of three-membered carbocycles is at the forefront of scientific research, playing an important role in organic syntheses, as energy materials, biomedicine, etc. Especially, high-energy aerospace fuels as power sources can directly improve the payload and flight distance of space craft. For aerospace vehicles, the electronic devices and equipment need enough space, while leaving very limited volume for fuels1. Compared to common linear chains, cyclobutene- and cyclopentane-based hydrocarbons, cyclopropane-based aerospace compounds have high torsional and angular strains. Their densities would be increased, resulting in a bigger volumetric heating value for the higher performance task2.

At present, the methods for synthesizing cyclopropane-based high-energy fuels mainly include: Simmons-Smith reactions3,4,5,6, diazo-derived carbene complexes7,8, Kishner reaction9, Kulinovich reaction10, et al. Within these, the synthesis of cyclopropane-based aerospace fuels using Fischer carbenes as an intermediate has the advantages of simple reagents, mild conditions, and rapid reaction. However, diazo compounds (for example, ethyl diazoacetate) typically require electron-withdrawing groups (EWG) to stabilize active intermediates, and Fischer carbenes are difficult to form and activate11,12. These issues lead to low conversion and selectivity in cyclopropanation reaction using Fischer carbenes, which is a key challenge for the synthesis of multi-cyclopropane-based aerospace fuels. Using the typical conjugated diene derivatives as examples, the selectivity of Simmons-Smith reactions (2.9 to 23.0%)13,14 and diazo-derived carbene complexes (7.4 to 18.8%)15 is very low for the preparation of multi-cyclopropane-based high-energy aerospace fuels (Fig. 1). The key issue is that the metal centers in catalysts are very difficult to be activated to form metal Fischer carbenes intermediates.

Strain engineering represents an effective strategy for modulating the active centers of heterogeneous catalysts, including single-site catalysts, and various nanostructured materials. This approach can facilitate enhanced mass transport and reactant dissociation16, while also optimizing the adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates17. Single-site catalysts characterized by their atomically precise structures offer exceptional tunability of metal active sites at the atomic level18. In the cyclopropanation reaction of alkenes, the CH2N2 insertion into metal active centers to form Fischer carbenes and carbene transfer are two key steps19,20,21. Further studies are warranted to explore strategies, especially strain engineering, for optimizing metal coordination environments and electronic distributions to advance this catalytic system.

Herein, through the support-induced strain engineering between Cu(acac)2 and single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT), we prepared a novel single-site catalyst Cu/SWCNT and achieved highly efficient generation of diadducts from isoprene and other dienes. Bending strain elongates Cu-O bonds and promotes CH2N2 to form Fischer carbene intermediates. Moreover, the transfer of electrons from SWCNT to Cu leads to an upward shift of the d-band center of β electrons, promoting the adsorption and activation of CH2N2. These results indicate that strain engineering is a valuable strategy to adjust the efficiency of diene cyclopropanations.

Results

Design of catalysts based on strain engineering

Single-site catalysts with metal centers and conjugated bonds can form weak interactions with supports as graphene22,23. Meanwhile, Cu(acac)2 has a typical planar conjugated structure, in which Cu2+ coordinates with acetylacetone in a planar tetragonal shape. Inspired by these, if graphene with a planar structure is bent into carbon nanotubes (CNT), the metal active center will also be subjected to bending strain, which is called support-induced bending strain (Fig. 2). Through density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the angle between the two acetylacetone ligands changed from 180 degrees to 158 degrees after introducing bending strain. To measure “bending strain” quantitatively, strain factor α was defined as follows (θ: the angle between the two planes formed by Cu and the ligands on both sides):

According to Eq. (1), the α of Cu/SWCNT was 12.2%. The independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld (IGMH) and energy decomposition indicated that the dispersion effect between Cu(acac)2 and SWCNT is dominant (Supplementary Fig. 1), which is the typical π-π stacking interaction24,25,26,27,28.

Preparation and characterizations of catalysts

In order to confirm the design of bending strain, Cu(acac)2 / single-walled carbon nanotube complex (Cu/SWCNT) was prepared via a modified impregnation-filtration method (details see “Methods”)29,30. Meanwhile, as a comparison sample, Cu(acac)2/graphene complex (Cu/G) without bending strain was synthesized according to the same method.

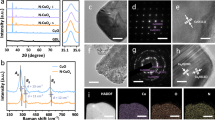

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a, pristine SWCNT has a microstructure with fine and micrometer-sized lengths. After Cu(acac)2 deposition, there is no significant change in the morphology of SWCNT at the micrometer scale for Cu/SWCNT (Supplementary Fig. 2b). TEM and HRTEM images further show that there are no Cu(acac)2 nanoparticles deposited on the surface of SWCNT (Fig. 3a,b). The lattice patterns of bundles, which are formed by strong van der Waals interactions between SWCNTs31, were detected. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the average length between two SWCNTs (including SWCNT diameter d and spacing λ) is 1.73 nm. The SWCNT spacing λ is usually 0.34 nm32, and the average diameter of SWCNT is 1.39 nm. In addition, SWCNTs with a diameter of 1 ~ 2 nm were detected at some locations by atomic force microscope (Supplementary Fig. 3). As mentioned above, SWCNTs in Cu/SWCNT catalyst exist in the form of bundles with a diameter of about 1–2 nm.

a Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image, (b) high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of Cu/SWCNT; (c) Schematic diagram of the stacking structure of SWCNT bundle; (d) Spherical aberration corrected scanning transmission electron microscope under high-angle annular dark field mode (AC HAADF-STEM) image of Cu/SWCNT; (e) Raman spectra of the Cu(acac)2, SWCNT and Cu/SWCNT; (f) Statistical histogram of C–C bonds length in SWCNT and Cu/SWCNT.

AC HAADF-STEM image reveals that Cu atoms are independently and uniformly dispersed on SWCNT, indicating that Cu atoms exist in the form of single site (Fig. 3d). EDS mapping further indicates the uniform distribution of Cu element (Supplementary Fig. 4). Also, XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 5) indicates that there are no diffraction peaks of Cu metals or Cu(acac)2 for Cu/SWCNT. As the comparative sample Cu/G, Cu atoms are loaded on graphene in the form of a single site (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Raman, ATR-FTIR spectra and DFT calculations were employed to explore the possible interactions between Cu(acac)2 and SWCNT. As shown in Fig. 3e, the peaks at ~150 cm−1 (RBM, R bands) are characteristic of single-walled carbon nanotubes, corresponding to the radial respiratory vibration (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The peak at ~1350 cm−1 (D band) corresponds to defect sites. The peak at ~1580 cm−1 (G band) is a tangential mode, which can be mainly divided into G+ peak with atomic displacement along the tube axis and G- peak with atomic displacement along the circumferential direction (Supplementary Fig. 7b)33. The peak at ~2700 cm−1 (2D band) is the second order of boundary phonons34. The mathematical relationship between R-band wavenumber (ωRBM) and carbon nanotube diameter (d) can be established as follows33:

According to Eq. (2), the diameters of carbon nanotubes in the pristine SWCNT and Cu/SWCNT can be calculated as 1.45 ~ 2.03 and 1.44 ~ 2.00 nm, respectively. This indicates that Cu(acac)2 loading has no significant effect on the diameter of SWCNT. The peak intensity ratio of D and G bands (ID/IG) is positively correlated with defect concentration. Compared to pristine SWCNT (0.020), the ID/IG is 0.026 for Cu/SWCNT, indicating the quality of SWCNT is very high, and the chemical structure of SWCNT does not change significantly after Cu(acac)2 loading.

As shown in Fig. 3e, the R, G, and 2D bands of Cu/SWCNT shift to high wavenumbers compared to those of the pristine SWCNT. This indicates that SWCNT is affected by compressive strain, while Cu(acac)2 is subjected to tensile strain in Cu/SWCNT35,36,37. And in Supplementary Fig. 8 for ATR-FTIR, the peak of C-C stretching transition of aromatic hydrocarbons further confirms the existence of bending strain between Cu(acac)2 and SWCNT due to the high wavenumber shift38. These results are also demonstrated through DFT calculations (Fig. 3f). Compared to pristine SWCNT (1.4160 Å), the average length of C–C bonds is 1.4149 Å, indicating that SWCNT is subjected to compressive strain in Cu/SWCNT.

Coordination environment of catalysts

To ascertain the valence state and coordination environment of Cu, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) and DFT calculations were conducted. As depicted in Fig. 4a, the two peaks of Cu 2p1/2 (954.7 eV) and Cu 2p3/2 (934.8 eV) correspond to the spin-orbit doublet of Cu2+ for pristine Cu(acac)239. Moreover, compared to pristine and Cu/G, these two peaks shift to the lower energy for Cu/SWCNT (954.5 and 934.6 eV). This indicates that bending strain enhances the interaction between Cu atoms and SWCNT, which may lead to electron transfer from SWCNT to Cu atoms. DFT calculations (charge density difference and Hirshfeld charge) also confirm this assertion. Charge density difference illustrates that electrons transfer from SWCNT to Cu atoms (Supplementary Fig. 9). The Hirshfeld atomic charge of Cu atom is + 0.535 in Cu/SWCNT, which is lower than that in pristine Cu(acac)2 ( + 0.555) (Fig. 4b). Meanwhile, X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) of Cu foil, Cu2O, Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT indicates that the valence state of Cu atoms in Cu/SWCNT is between Cu+ and Cu2+ (Fig. 4c)40. These results prove that bending strain causes the transfer of electrons from SWCNT to Cu atoms in Cu/SWCNT.

a X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements of Cu 2p of Cu(acac)2, Cu/G and Cu/SWCNT; (b) Atomic-coloring Hirshfeld charge of Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT (for better visualization, the upper color limit of Cu is set to 0.60 a.u.); (c) X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) of Cu K-edge of Cu foil, Cu2O, Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT; (d) Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for Cu foil, Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT.

The fine coordination environment of Cu/SWCNT was analyzed by EXAFS. As shown in Fig. 4d, the peaks of Cu foil and Cu(acac)2 are located at 2.24 and 1.53 Å, respectively. Cu/SWCNT displays a dominant peak at approximately 1.56 Å, which corresponds to the Cu–O coordination41. This indicates that Cu species are atomically anchored on SWCNT. EXAFS fitting data of Cu foil, Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. This coordination involves Cu-O bonds, which are 1.96 Å away from four oxygen atoms (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 1). Compared to Cu(acac)2, the Cu–O bond length increases from 1.91 to 1.96 Å in Cu/SWCNT.

Catalytic activity for cyclopropanations

The catalytic performance of Cu/SWCNT was evaluated for cyclopropanation reactions. As a biomass derivative and the typical conjugated diene, isoprene (IP) was selected as the alkene substrate (Table 1). With different catalysts, IP reacted with CH2N2 to produce the corresponding monoadducts and the diadduct (details see “Methods”). Specially, the Cu/G was evaluated as a comparative sample without bending strain.

The following experiments were conducted on reaction parameters of temperature, CH2N2 dosage, catalyst dosage and solvents (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 11). Under non-catalyst and pristine SWCNT conditions, almost no diadduct were generated (Table 1, entry 1–2), thus it eliminated the interference of substrate SWCNT on catalytic performance. By using 0.8 mol% Cu(acac)2, the diadduct selectivity was 11.4% (Table 1, entry 3). At the same molar amount of Cu, the diadduct selectivity for Cu/G was 12.8% (Table 1, entry 4), which was not significantly enhanced compared to Cu(acac)2. This indicated that there was no significant improvement in catalytic performance in the absence of bending strain. The catalytic performance of Cu/SWCNT was tested at 0 to 40 oC (Table 1, entry 5-9). The conversion was 47.3 to 78.0%, and the diadduct selectivity was 22.7 to 46.5%. These were much higher than those of Cu(acac)2 and Cu/G, indicating that bending strain plays a crucial role in enhancing the catalytic performance. Considering the safety of the experiment, 20 oC was chosen as the proper reaction temperature (Table 1, entry 7). As to the dosage of reactants, the results were shown in Table 1, entry 7,10-13. With the continuous increase of CH2N2 dosage, the diadduct selectivity increased (38.2 to 45.7%) and then decreased (45.7 to 37.5%). The effect of catalytic dosage on the reaction was shown in Table 1, entry 7,14–18. As the amount of catalyst increased, the diadduct selectivity also had a trend of increasing and then decreasing. When the amount of Cu/SWCNT was 0.2–0.6 mol%, the didduat selectivity increased (19.8 to 45.7%) with the increase of active sites. When Cu/SWCNT was as high as 1.0–1.2 mol%, the increase of by-products led to a slight decrease of the diadduct selectivity (45.7 to 41.7%). The optimal reaction conditions are 20 °C, the molar ratio of IP to CH2N2 of 1:4, and the catalyst dosage of 0.8 mol% (Table 1, entry 7).

Under above conditions, the catalytic performance of Cu(acac)2, Cu/G and Cu/SWCNT is shown in Fig. 5a. Compared to Cu(acac)2, the conversion of the reaction increases to ~2.6 times, and the diadduct selectivity increases to ~4.0 times for Cu/SWCNT. As for Cu/G without bending strain, there is no significant improvement in reaction conversion and selectivity. Another two catalysts (Cu/CNT25 and Cu/CNT50) without bending strain also confirmed the hypothesis (Supplementary Figs. 12–14). These results demonstrate the crucial role of bending strain in improving the cyclopropanation reaction.

a reaction conversion, selectivity of monoadducts and diadduct under Cu(acac)2, Cu/G, Cu/SWCNT conditions; (b) mass spectra of two monoadducts and the diadduct; (c) density and volumetric calorific value of IP, the diadduct of IP (IP-D), THI and the diadduct of THI (THI-D); (d) selectivity of diadducts from alkenes with similar structures to IP under different catalysts14,15,44,45 (inset: molecular formulas of diadducts from different alkenes); (e) catalytic activities of Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT using four different alkenes as 1,5-hexadiene, dipentene, tetrahydroindene and dicyclopentadiene (inset: molecular formulas of diadducts from different alkenes).

The structures of two monoadducts and a diadduct are confirmed by the mass spectrum (Fig. 5b). According to the standard spectra42, the mass to charge ratio (m/z) peaks, especially those with the highest and second highest intensity, are consistent with the monoadducts and the diadduct. To verify the effectiveness of the cyclopropanation strategy in increasing the volumetric calorific value of fuels, two kinds of diadducts (IP-D and THI-D) were obtained from IP and THI through distillation (Supplementary Fig. 15a, c). The purity of the IP-D and THI-D is 97.4% and 97.1% (Supplementary Fig. 15b, d), respectively. The structure of THI-D was confirmed by mass spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 16). As shown in Fig. 5c, after the cyclopropanation reaction of alkenes, the density of IP increased from 0.68 to 0.78 g·cm−3, and the density of THI increased from 0.93 to 0.98 g·cm−3. This indicates that the cyclopropaneization strategy can effectively increase the density of compounds. The calorific values of two cyclopropane-based high-energy fuels were determined using an oxygen bomb calorimeter (Supplementary Fig. 17) and shown in Fig. 5c. After the cyclopropanation reaction of alkenes, the volumetric calorific value of IP increases from 31.58 to 33.24 MJ L−1, and that of THI increases from 41.12 to 43.68 MJ L-1. These results indicate that the cyclopropanation reaction can effectively increase the volumetric calorific value of fuels. Compared to commonly used JP-10 fuel (0.94 g cm−3, 39.60 MJ L−1)43, the THI-D possesses a higher density (0.98 g cm−3) and volumetric calorific value (43.68 MJ L−1), exhibiting its potential application as high-energy aerospace fuels.

The catalytic performance of Cu/SWCNT was much better than other reported catalysts (Fig. 5d)14,15,44,45. Alkene substrates include IP and other dienes with similar structures. Compared to the Zu–Cu couple, Pd(acac)2 and Cu(OTf)2, the selectivity of Cu/SWCNT is higher, at 45.7%. Furthermore, 1,5-hexadiene ( = HDE, chain alkene without conjugate), dipentene ( = DPE, chain and cyclic alkene), tetrahydroindene ( = THI, cyclic alkene) and dicyclopentadiene ( = DCPD, cyclic alkene) were selected to check the substrate generality of Cu/SWCNT (Supplementary Fig. 18). Compared to Cu(acac)2, the diadduct selectivity was all enhanced (HDE: from 2.3% to 22.1%; DPE: from 5.0% to 23.1%; THI: from 2.7% to 28.0%; DCPD: from 2.8% to 13.6%;) by using Cu/SWCNT (Fig. 5e). This further confirms that bending strain can effectively improve the diadduct selectivity for cyclopropanation reactions from dienes. Meanwhile, Cu/SWCNT possesses good cycling stability (Supplementary Fig. 19). After 6 cycles of utilization, the Cu content of Cu/SWCNT decreased by 21%, while the Cu content of Cu/G decreased by 50% (Supplementary Fig. 20). The morphology of the used Cu/SWCNT did not change obviously in comparison to fresh sample (Supplementary Figs. 21–S23). After reactions, the chemical structure of SWCNT showed a slight change with an ID/IG value of 0.048 (Supplementary Fig. 22c), and the valence state of Cu did not show visible changes either (Supplementary Fig. 22d). Additional experiments revealed that the reaction occurred on the surface of the heterogeneous catalyst Cu/SWCNT (Supplementary Figs. 24, 25). Meanwhile, it has the potential for amplification (Supplementary Table 2).

The bending strain exists in single-site molecular catalysts46,47 and metal-embedded carrier catalysts16. The Cu/SWCNT was a kind of novel molecular catalyst, which applied bending strain to the construction of three-membered carbocycles.

Promotion mechanism of bending strain

To decide cyclopropanation reactions as one-step direct or stepwise reactions, experiments on the relative content of IP and products over time were performed using Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT. In order to slow down the reaction rate and reduce the sampling error during the reaction, the solvent (CH2Cl2) was amplified to 4-fold. As shown in Fig. 6a, in the first 30 s of the reaction, the monoadducts rapidly increased, while almost no diadduct was observed. Until the 3rd minute, the diadduct gradually formed, with a selectivity maintained at around 10% until the end of the reaction. It indicated that the cyclopropanation reactions are stepwise: IP was converted into monoaddcuts, and then the diadduct. In addition, the by-products rapidly decreased after rising within 3 min, showing that the side reaction is reversible. Similar phenomena were also observed for Cu/SWCNT (Fig. 6b). The difference is that the diadduct has already been produced at 30 s, whose conversion and diadduct selectivity are much higher than that of Cu(acac)2. This suggests that bending strain effectively reduces the reaction energy barrier and promotes the reaction kinetics process. The by-products were detected by IR and NMR (Supplementary Figs. 26, S27), and corresponding side reactions were proposed in Supplementary Fig. 26a. IP and CH2N2 undergo 1,3-dipole cycloaddition reaction to form 2-pyrazoline48. The free energy change (∆G) of the two-step reaction was calculated by DFT: the ∆G of steps I and II are −58 and −61 kcal mol−1, respectively (Fig. 6c). This exhibits that the two reactions are thermodynamically spontaneous, and kinetics is the determining factor for the efficiency of the reaction. Due to the high selectivity of monoadducts, the reaction kinetics process of step II was mainly studied.

Time variation curves of conversions and selectivity using (a) Cu(acac)2 and (b) Cu/SWCNT. (c) sketch map of reaction kinetics and thermodynamics. d A molecular dynamics (MD) simulation snapshot of the reaction system using Cu/SWCNT catalyst [red: Cu(acac)2; blue: CH2N2; gray: monoadducts; silver: SWCNT; gray bubbles: CH2Cl2]. e Radial distribution function (RDF) of Cu-C pairs (C atoms referred to C atoms in CH2N2, double bonds in monoadduct, respectively). f projected density of state (PDOS) of Cu2+ d-orbital in Cu/SWCNT (the red, blue dashed lines represent the d-band centers of β, α electrons, respectively). Inset: splitting energy levels of the d-orbital plane tetragonal crystal field of Cu2+.

In order to study the interaction between catalysts and reactants in detail, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were employed via the GROMACS 2018.8 software49. The reaction system model was established through the PACKMOL software50, which included Cu/SWCNT, CH2N2, monoadducts and CH2Cl2. All topology files were obtained using the Sobtop software51. Before statistical analysis, the reaction system had reached equilibrium (Supplementary Fig. 28). A snapshot of the reaction system is shown in Fig. 6d. Throughout the simulation process (10 ns), the O–Cu–O dihedral angles of both sides in Cu(acac)2 remained bent and tightly adhered to the surface of SWCNT, which indicates that the structure of Cu/SWCNT possesses good stability. Radial distribution function (RDF) analysis is shown in Fig. 6e, and the curve data represent the distance between the monoadducts, CH2N2 and Cu in Cu/SWCNT. There are three CH2N2 adsorption layers located at 0.27, 0.45, and 0.79 nm, but only two monoadduct adsorption layers located at 0.32 and 0.76 nm. This indicates that the interaction between Cu/SWCNT and CH2N2 is stronger. During the catalytic process, Cu/SWCNT will first react with CH2N2, which is consistent with the results in the literature21.

Projected density of state (PDOS) of Cu2+ d-orbital and the d-band centers of β, α electrons were calculated (Fig. 6f). According to the d-band center theory52, the upward shift of the d-band center pushes more antibonding states above the Fermi level, and fewer antibonding states are occupied. The chemical bonding between transition metals and small molecules will be stronger in this way. After being subjected to bending strain, the d-band center of α electrons remains unchanged, while the d-band center of β electrons slightly shifts towards the Fermi level (−4.370 to −4.366). The XPS, XAFS and DFT results (Figs. 5a–c, Supplementary Fig. 5) show that electrons of SWCNT transfer to Cu, which is the reason for the d-band center shift of β electrons. This proves that charge transfer causes the d-band center of β electrons to shift upward, promoting the chemical adsorption of Cu and CH2N2. Combining experiments and Mayer bond-order calculations (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 29), the bond order of Cu–O decreases (0.565 to 0.561 a.u.) and the Cu–O bond length increases (1.91 to 1.96 Å) in Cu/SWCNT. This will facilitate the insertion of CH2N2 into Cu–O bonds for Cu/SWCNT catalyst, thereby forming Cu = C Fischer carbene intermediates. These results indicate that bending strain can elongate the Cu–O bond length, promote CH2N2 insertion, and form Cu = C Fischer carbene intermediates.

It was experimentally proven that bending strain had an effect on Cu = C carbenes (in situ DRIFTS, Supplementary Figs. 30, 31). The cyclopropanation reaction mechanism of step II is proposed in Fig. 7. The reaction mainly involves two processes21: (1) Formation of Cu = C carbenes. CH2N2 inserts into the catalyst 1 to form the structure 2, which is stabilized by hydrogen bonding between C–H and O atom. Subsequently, through the transition state TS1, N2 desorbs to form the Fischer carbene 3. (2) Absorption of the C–C double bond. Monoadducts were adsorbed on the 3, forming adsorption state 4. (3) Cyclopropanation of monoadducts. The product underwent a [2 + 1] synergistic addition with Cu-carbene, i.e., a 3-center transition state TS2. After that, structure 5 was formed, resulting in the formation of the diadduct. The energy change curve of the reaction pathway was calculated using CP2K software53 and the PBE/TZVP-MOLOPT-GTH method54. The intermediate configurations of the reaction are shown in Supplementary Figs. 32, 33. As depicted in Fig. 7 inset, compared to pristine Cu(acac)2 (40.7 kcal mol−1), the reaction energy barrier (TS2) is 33.7 kcal mol−1 for Cu/SWCNT. This illustrates that bending strain can effectively reduce the reaction energy barrier of the cyclopropanation reaction from dienes. The lower reaction energy barrier accelerates the reaction kinetics process (Fig. 6a,b), thus improving the conversion of IP and the selectivity of diadduct (Fig. 5a).

Discussion

The bending strain between Cu(acac)2 and single-walled carbon nanotube (Cu/SWCNT) was constructed to highly catalyze cyclopropanation reactions of dienes. Compared to pristine Cu(acac)2 without bending strain (conv. 29.5%; sel. 11.4%), single-site Cu/SWCNT exhibited the conversion up to 2.6 times (77.4%) and the diadduct selectivity up to 4.0 times (45.7%). Moreover, Cu/SWCNT possesses good substrate applicability as its catalytic performance is significantly improved with using the other four diene substrates (HDE, DPE, THI and DCPD). The resulting cyclopropane-based THI-D (0.98 g cm−3, 43.68 MJ L−1) is a promising candidate applied for high-energy aerospace fuels. The experiments show that the cyclopropanation reaction of IP is a stepwise reaction, and Cu/SWCNT first reacts with CH2N2 instead of IP. Bending strain promoted cyclopropanation reaction of the monoadducts and improved the diadduct selectivity: (1) bending strain induces the d-band center of β electrons to shift upward for Cu/SWCNT (-4.370 to -4.366), enhancing the chemical adsorption of CH2N2 and alkenes. (2) bending strain elongates the Cu–O bond length (1.91 to 1.96 Å), promotes CH2N2 insertion to form Cu = C Fischer carbene intermediates. Both aspects can effectively reduce the reaction energy barrier of the cyclopropanation process (40.3 to 33.7 kcal mol−1) and accelerate the reaction kinetics process. However, precise control of bending strain has not yet been achieved. This can be achieved through controlled synthesis (floating catalysis, etc.) and high dispersion (functionalized grafting, etc) of SWCNTs. This work unravels that “bending strain” is an efficient strategy to improve the efficiency of cyclopropanation reactions, and provides a prospective pathway for industrial applications of high-energy aerospace fuels.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Copper (II) acetylacetonate [Cu(acac)2], dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), ethanol (CH3CH2OH), ethyl acetate (CH3COOC2H5), sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium hydroxide (KOH), magnesium sulfate anhydrous (MgSO4), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), N-methylurea, isoprene (IP), 1,5-hexadiene (HDE), dipentene (DPE), tetrahydroindene (THI) and dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) were purchased from Aladdin. High purified single-wall carbon nanotube (SWCNT, diameter 1–2 nm), multi-wall carbon nanotube (MWCNT, diameter ~25 nm and ~50 nm), and graphene (thickness 1–5 nm) were purchased from XFNANO. Deionized water was self-made in the laboratory. Unless otherwise stated, reagents and solvents were commercially obtained and used without further purification.

Synthesis of carbene precursors

55 mL of concentrated nitric acid (68 wt%, 15.2 mol L−1) was poured into deionized water and stirred, then transferred to a volumetric flask to reach a volume of 500 mL to obtain 10 wt% dilute nitric acid. 100 g of NaNO2 was dissolved in 300 mL of deionized water and stirred evenly. 100 g of N-methylurea (1.35 mol) and 950 mL of dilute HNO3 (10 wt%) were added into a three-necked flask and stirred at 10 °C for 10 min. After the solid was dissolved, 400 g of NaNO2 solution was added dropwise to a three-necked flask. After adding the NaNO2 solution, the reaction was carried out for 30 min. The product was filtered to obtain N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (NMU), which was dried at room temperature in a vacuum drying oven. Finally, the dried product was loaded into a brown bottle to avoid light decomposition.

Preparation of catalysts

The Cu/SWCNT catalyst was prepared through a previously reported impregnation-filtration method29. Typically, 134.8 mg of Cu(acac)2 was dissolved in 150 mL of acetone, followed by ultrasound for 30 min. 0.5 g of SWCNT was added to the solution and sonicated for 30 min to form a homogeneous dispersion. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The solution was filtered under reduced pressure, and the obtained catalyst was then placed in an oven (60 °C) for drying. The Cu/G, Cu/CNT25 and Cu/CNT50 were synthesized using the same procedure, only replacing SWCNT with graphene, MWCNT (~ 25 nm) and MWCNT (~ 50 nm).

Cyclopropanation reactions

4.9 g of KOH (15 eq.) was dissolved in 4.9 mL of deionized water and stirred evenly. Subsequently, under N2 atmosphere and 20 °C conditions, 0.409 g of isoprene (6 mmol, 1 eq), 217.9 mg of 1.40 wt% Cu/SWCNT (0.8 mol%), 18 mL of CH2Cl2, and 9.8 g of KOH solution were added to a three-necked spherical flask. Under stirring conditions, 2.47 g NMU (24 mmol, 4 eq) was slowly added and reacted for 2 h. After the reaction, diluted hydrochloric acid (2 M) was added dropwise to quench the reaction. The reaction solution was filtered and then extracted using CH2Cl2, followed by washing the organic phase with 24 mL of saturated NaCl. At 45 °C, 250 mbar (25 kPa), the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation to obtain a yellow oily product.

Characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) were obtained on a FEI Titan G260-300 with an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. Atomic force microscope (AFM) data was collected by using Bruker MultiMode 8. The Raman spectra were performed on Raman Spectrometer (DXR, 532 nm). X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were performed by Thermo ESCALAB 250XI. And the binding energies were corrected for C 1 s to 284.8 eV. The XPS data were analyzed by the XPSPEAK41 software. The spin-orbit splitting peak was set to 19.75 eV (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The FWHM of Cu(acac)2, Cu/G, and Cu/SWCNT were 1.85, 2.48, and 1.78 eV, respectively. The Chi-square value of Cu(acac)2, Cu/G, and Cu/SWCNT were 5.25, 8.12, and 2.33, respectively. Crystallographic information on the as-prepared samples was recorded using powder X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD, Bruker D8). The load of Cu was measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Agilent 720). After weighing, the sample was added to HNO3, HF, HCl and H2O2, then heated in a 180 °C oven for 8 h to dissolve, finally cooled and transferred for testing. Gas chromatography (GC) was performed by (SHIMADZU). The chromatographic column type is HP-5, the injection volume is 1 μL, and the split ratio is 150:1. X-ray absorption spectra (XAS), including X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of the samples at Cu K-edge, were collected at the Beamline of TLS07A1 in National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Taiwan. The data were analyzed by the Athena and Artemis software. Liquid nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was obtained by the Bruker AV 500 M using CDCl3 as a solvent. Experiments of in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (In situ DRIFTS) were performed in a Bruker INVENIO S spectrometer with a diffuse reflection SharpX reaction chamber under atmospheric conditions. The catalyst powder and the IP were loaded into the reaction chamber, and then the CH2N2/CH2Cl2 solution was purged with N2 (5 mL/min) and passed through it.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) was applied by using the Gaussian 16 (Revision A.03). Unless otherwise stated, all atomic structure relaxation was calculated by the PBE0/6–31 G(d,p) method. Among them, 6–31 G + (d,p) basis set was used for C, O, and H atoms in Cu(acac)2, while SDD pseudopotential and corresponding pseudopotential basis set were used for Cu atoms. The Multiwfn software was employed to process wave function files for electron density, energy decomposition, independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld (IGMH), etc24,25. The energy change curve of the reaction pathway was calculated using CP2K software (version 6.1.0) and the PBE/TZVP-MOLOPT-GTH method. The self-consistent continuum solvation (SCCS) model with a dielectric constant of 9.1 was used to simulate the solvent (CH2Cl2) environments during the reaction process55. All transition state structures had only one imaginary frequency, and the reaction pathway connected reactants and products.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the GROMACS software (version 2018.8). The top files were generated by the sobtop software51. Except for Cu atoms (the UFF force field), other atoms were set to the GAFF force field. Bonded parameters were prebuilt if possible; missing ones were supplemented by the mSeminario method. The initial box size was set to 5.879*5.879*5.879 nm for Cu(acac)2, while the box size was 6.008*6.008*5.158 nm for Cu/SWCNT. Prior to MD simulations, the system was pre-equilibrated to eliminate unreasonable intermolecular contact. For the monoadduct reaction system using the catalysts [Cu(acac)2 and Cu/SWCNT], the number of Cu(acac)2, monoadduct, CH2N2, and CH2Cl2 was 1, 125, 125, 1250, respectively. All molecules were released for relaxation. Using the NPT ensemble, the simulation time for all reaction systems was 10 ns. Hot bath was set as Velocity-rescale (298.15 K), while a pressure bath as Parrinello-Rahman (1 bar). Relative RMSD values of temperature, density and total energy were obtained as 1.0%, 0.9% and 1.3%, respectively. The dynamic step size was 1 fs, and information sampling was conducted every 5000 fs.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30453212). All other data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Zhang, X. et al. Review on synthesis and properties of high-energy-density liquid fuels: hydrocarbons, nanofluids and energetic ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. Sci. 180, 95–125 (2018).

Cruz-Morales, P. et al. Biosynthesis of polycyclopropanated high-energy biofuels. Joule 6, 1590–1605 (2022).

Simmons, H. E. & Smith, R. D. A new synthesis of cyclopropanes1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81, 4256–4264 (1959).

Lorenz, J. C. et al. A novel class of tunable zinc reagent (RXZnCH2Y) for efficient cyclopropanation of olefin. J. Org. Chem. 69, 327–334 (2004).

Boyle, B. T., Dow, N. W., Kelly, C. B., Bryan, M. C. & MacMillan, D. W. Unlocking carbene reactivity by metallaphotoredox α-elimination. Nature 631, 789–795 (2024).

Zhang, L., DeMuynck, B. M., Paneque, A. N., Rutherford, J. E. & Nagib, D. A. Carbene reactivity from alkyl and aryl aldehydes. Science 377, 649–654 (2022).

Meshcheryakov, A. P. & Dolgii, I. E. The synthesis of certain compounds having two neighbouring three-member cycles. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 139, 1379–1382 (1961).

Caballero, A., Prieto, A., Díaz-Requejo, M. M. & Pérez, P. J. Metal-catalyzed alkene cyclopropanation with ethyl diazoacetate: control of the diastereoselectivity. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 9, 1137–1144 (2009).

Jie, J. L. Name reactions for carbocyclic ring formations, 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, (2010).

Kulinkovich, O. G. et al. Reaction of ethylmagnesium bromide with esters of carboxylic acids in the presence of tetraisopropoxytitanium. Zh. Org. Khim. 25, 2244–2245 (1989).

Ebner, C. & Carreira, E. M. Cyclopropanation strategies in recent total syntheses. Chem. Rev. 117, 11651–11679 (2017).

Lebel, H., Marcoux, J. F., Molinaro, C. & Charette, A. B. Stereoselective cyclopropanation reactions. Chem. Rev. 103, 977–1050 (2003).

Overberger, C. G. & Halek, G. W. Monomers and polymers, a synthesis of vinyl cyclopropane and dicyclopropyl. J. Org. Chem. 28, 867–868 (1963).

Guerreiro, M. C. & Schuchardt, U. Site and stereoselectivity of the cyclopropanation of unsymmetrically substituted 1, 3-dienes by the Simmons-Smith reaction. Synth. Commun. 26, 1793–1800 (1996).

Dzhemilev, U. M. et al. Reactions of diazoalkanes with unsaturated compounds: 6. Catalytic cyclopropanation of unsaturated hydrocarbons and their derivatives with diazomethane. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. 38, 1707–1714 (1989).

Jiang, K. et al. Rational strain engineering of single-atom ruthenium on nanoporous MoS2 for highly efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 1687 (2021).

Xin, Y. et al. Subtle modifications in interface configurations of iron/cobalt phthalocyanine-based electrocatalysts determine molecular CO2 reduction activities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202420286 (2024).

Abdinejad, M. et al. Eliminating redox-mediated electron transfer mechanisms on a supported molecular catalyst enables CO2 conversion to ethanol. Nat. Catal. 7, 1109–1119 (2024).

Rodríguez-García, C., Oliva, A., Ortuño, R. M. & Branchadell, V. Mechanism of alkene cyclopropanation by diazomethane catalyzed by palladium dicarboxylates. a density functional study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6157–6163 (2001).

Cao, Z. Y. et al. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of cyclopropanes featuring vicinal all-carbon quaternary stereocenters with a CH2F group; study of the influence of C–F···H–N interactions on reactivity. Org. Chem. Front. 5, 2960–2968 (2018).

Planas, F., Costantini, M., Montesinos-Magraner, M., Himo, F. & Mendoza, A. Combined experimental and computational study of ruthenium N-hydroxyphthalimidoyl carbenes in alkene cyclopropanation reactions. ACS catal. 11, 10950–10963 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Heterogeneous molecular Co-N-C catalysts for efficient electrochemical H2O2 synthesis. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 446–459 (2023).

Hutchison, P., Smith, L. E., Rooney, C. L., Wang, H. & Hammes-Schiffer, S. Proton-coupled electron transfer mechanisms for CO2 reduction to methanol catalyzed by surface-immobilized cobalt phthalocyanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20230–20240 (2024).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. X. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: a new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. X. Simple, efficient, and universal energy decomposition analysis method based on dispersion-corrected density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 7023–7035 (2023).

Grimme, S. Do special noncovalent π–π stacking interactions really exist? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 47, 3430–3434 (2008).

Su, J. et al. Strain enhances the activity of molecular electrocatalysts via carbon nanotube supports. Nat. Catal. 6, 818–828 (2023).

Zhu, Q. et al. The solvation environment of molecularly dispersed cobalt phthalocyanine determines methanol selectivity during electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Nat. Catal. 7, 987–999 (2024).

Britz, D. A. & Khlobystov, A. N. Noncovalent interactions of molecules with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 637–659 (2006).

Dai, J., Lu, L., Zhang, C. & Cui, Y. Preparation and characterization of single-walled carbon nanotube and its bundle. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 33, 161–164 (2007).

Jorio, A. et al. Characterizing carbon nanotube samples with resonance Raman scattering. N. J. Phys. 5, 139 (2003).

Ferrari, A. C. & Basko, D. M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 235–246 (2013).

Yoon, D., Son, Y. W. & Cheong, H. Strain-dependent splitting of the double-resonance Raman scattering band in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 155502 (2011).

Del Corro, E., Taravillo, M. & Baonza, V. G. Nonlinear strain effects in double-resonance Raman bands of graphite, graphene, and related materials. Phys. Rev. B 85, 033407 (2012).

Chen, C. et al. Sub-10-nm graphene nanoribbons with atomically smooth edges from squashed carbon nanotubes. Nat. Electron. 4, 653–663 (2021).

Salzmann, C. G. et al. The role of carboxylated carbonaceous fragments in the functionalization and spectroscopy of a single-walled carbon-nanotube material. Adv. Mater. 19, 883–887 (2007).

Zhou, W. et al. In situ tuning of platinum 5 d valence states for four-electron oxygen reduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 6650 (2024).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Direct OC-CHO coupling towards highly C2+ products selective electroreduction over stable Cu0/Cu2+ interface. Nat. Commun. 14, 7681 (2023).

Feng, C. et al. Optimizing the reaction pathway of methane photo-oxidation over single copper sites. Nat. Commun. 15, 9088 (2024).

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standard reference database 69: NIST Chemistry WebBook. https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/.

Chung, H. S., Chen, C. S. H., Kremer, R. A., Boulton, J. R. & Burdette, G. W. Recent developments in high-energy density liquid hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Fuels 13, 641–649 (1999).

Nakhapetyan, L. A., Safonova, I. L. & Kazanskii, B. A. Reaction of isoprene with methylene iodide and a zinc-copper couple. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. 11, 840–841 (1962).

Salomon, R. G. & Kochi, J. K. Copper (I) catalysis in cyclopropanations with diazo compounds. Role of olefin coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 3300–3310 (1973).

Xin, Y. et al. (2025). Subtle modifications in interface configurations of iron/cobalt phthalocyanine-based electrocatalysts determine molecular CO2 reduction activities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 137, e202420286 (2024).

Zhou, B. et al. Electrosynthesis of CO from an electrically pH-shifted DAC post-capture liquid using a catalyst: support amide linkage. Joule 9, 101883 (2025).

Wang, W. et al. Pd/C catalytic cyclopropanation of polycyclic olefins for synthesis of high-energy-density strained fuels. AIChE J. 69, e18085 (2023).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High-performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1, 19–25 (2015).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Lu, T. Sobtop, Version 1.0(dev5), http://sobereva.com/soft/Sobtop (accessed on 18, 8, 2025).

Nørskov, J. K., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F. & Bligaard, T. Density functional theory in surface chemistry and catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci 108, 937–943 (2011).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Burke, K., Perdew, J. P. & Ernzerhof, M. Why the generalized gradient approximation works and how to go beyond it. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 61, 287–293 (1997).

Andreussi, O., Dabo, I. & Marzari, N. Revised self-consistent continuum solvation in electronic-structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 064102 (2012).

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the financial support from the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (grant YSBR-052 to Y.Q.Z.), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (grant No. 2024QNRC001 to Y.Y.C.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. U21A20307 and No.22578433 to Y.Q.Z., grant No. 22308087 to Y.Y.C., grant No. 22178359 to L.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. and X.Y.Z. designed the experiments, and Y.Y. carried out the DFT calculations. Y.Y. synthesized the catalysts and evaluated the catalytic performance, and analyzed the data. Y.Y.C. performed TEM experiments for sample screening and analyzed the data. L.L. did XAFS measurements, XPS experiments and analyzed the data. Y.Q.Z. contributed to characterization analysis. S.J.Z. provided suggestions with project design. Y.Y., Y.Y.C., Y.Q.Z. and S.J.Z. wrote the manuscript, and all the authors contributed to the overall scientific interpretation and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Zhang, X., Cao, Y. et al. Strain engineering of single-site Cu on SWCNTs for highly efficient diene cyclopropanation. Nat Commun 16, 11415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66241-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66241-6