Abstract

Conventional mRNA vaccines played a crucial role in mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic but remain hampered by inherent instability, transient expression, limited payload capacity, and complex manufacturing, including their reliance on lipid nanoparticle (LNP) encapsulation. To address these challenges, this study describes the Gemini platform, an expression system with a bifunctional eukaryotic–prokaryotic promoter that can be deployed as either a self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) or as a self-amplifying DNA (saDNA) replicon, enabling robust amplification and expression of genetic cargo. Gemini eliminates the requirement for LNPs, exhibits enhanced stability during freeze–thaw cycles and lyophilization, and is compatible with ambient-temperature storage, thereby simplifying production and distribution. It maintains a strong safety profile, supports larger and more complex payloads than conventional mRNA vaccines, and induces prolonged protein expression, as demonstrated by a potent single-dose SARS-CoV-2 Gemini-based vaccine. With rapid, scalable manufacturing and flexibility across saRNA and saDNA formats, Gemini represents a versatile next-generation platform with potential for broad applications in molecular medicine and pandemic preparedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines have demonstrated remarkable advantages in rapid development and adaptability1,2,3,4,5,6,7, yet they face significant challenges, including complex manufacturing requirements, thermal instability, reactogenicity, and limited payload capacity7,8. Notably, a major limitation is their reliance on lipid nanoparticles (LNP) for efficient mRNA delivery, which requires advanced technical infrastructure and raises concerns regarding long-term stability9. Moreover, these issues, together with rare adverse immune reactions10 and waning protection over time, highlight unresolved scientific hurdles in achieving durable and broadly protective vaccine immunity11. Consequently, there is a clear need for innovative platforms capable of achieving sterilizing immunity while overcoming these fundamental limitations.

Self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) delivery platforms present a promising alternative, overcoming many issues associated with conventional mRNA technologies. Recombinant saRNA expression vectors feature engineered replicons that encode and drive high levels of antigen expression12,13. Compared to mRNA technologies, significantly lower doses may be required, as tens of thousands of saRNA copies are synthesized, directing substantial mRNA transcription within recipient cells12. Moreover, saRNA vaccines can be delivered relatively non-invasively via intramuscular injection, similar to mRNA or DNA vaccines13,14.

Self-amplifying vaccines are considered safe and capable of inducing both humoral and cellular immunity while avoiding anti-vector immunity and minimizing the risk of vector genome integration into host genomes13,15. Compared to conventional vaccines, they offer lower intrinsic contamination risk from live infectious agents and improved scalability for mass production15. However, current saRNA vectors share several limitations common to established mRNA platforms: they require technically demanding in vitro transcription, their stability remains uncertain, and conventional paradigms suggest they are reliant on costly, specialized LNPs for cellular uptake and payload protein expression16, with LNPs themselves capable of inducing adverse effects1,2,3,10,17,18,19.

A critical consideration in LNP-based vaccine and therapeutic development is maintaining precise ratios between nucleic acid payloads and LNP formulations20,21,22,23,24,25,26. These ratios are essential for stability, encapsulation efficiency, and effective cellular uptake, and deviations can compromise formulation integrity, reducing efficacy or increasing toxicity. Additionally, LNP physical properties impose practical dosing volume limitations, as higher concentrations can promote aggregation or instability20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Administration restrictions, including maximum injectable volumes in preclinical models and human dosing guidelines, further limit the total deliverable dose and influence LNP-based therapeutic and vaccine design27.

Furthermore, the size of nucleic acid payloads that can be effectively incorporated into LNPs is inherently governed by several physicochemical and structural considerations. LNPs are optimized to encapsulate nucleic acids within particles of a defined size range, typically between 50-150 nm, to maintain stability, prevent aggregation, and ensure efficient cellular uptake18,21,28. Although mRNAs of ~1-2 kb are commonly employed and mRNAs up to ~4–5 kb can be incorporated effectively, longer sequences such as self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) ~ 9-10 kb or plasmid DNA > 10 kb exhibit reduced encapsulation efficiency due to steric hindrance, increased viscosity, and weaker interactions with ionizable lipids, all of which are critical components for nanoparticle formation and subsequent endosomal escape9,15,21,29,30. Moreover, larger nucleic acids tend to produce more polydisperse LNP populations, decreasing particle stability, promoting aggregation, and altering biodistribution, ultimately compromising therapeutic performance21,24. These constraints necessitate careful optimization of LNP composition and nucleic acid length to balance encapsulation efficiency, stability, and in vivo efficacy, potentially requiring alternative delivery platforms for larger genetic payloads.

This study describes the Gemini recombinant expression system, a veratile bi-functional replicon platform capable of functioning as either a self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) or a self-amplifying DNA (saDNA). Gemini can be used with or without LNPs, allowing it to overcome key limitations of conventional vaccine platforms such as the need for LNP encapsulation, multiple dosing, and restricted payload capacity. Beyond vaccines, Gemini also holds broad potential for delivering and expressing recombinant proteins or nucleic acids in diverse nanomedicine applications.

Results

Both Gemini saRNA and saDNA induce amplification in transfected cells

The Gemini platform is a nucleic acid replicon-based, self-amplifying dual-expression vector (herein referred to simply as either saRNA or saDNA). It contains a prokaryotic T7 promoter that drives the in vitro transcription of mRNA to generate the saRNA system for delivery into cells or tissues. The platform also includes a eukaryotic promoter, the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter/enhancer (CMV promoter), which functions in eukaryotic cells and drives transcription of saRNA from the saDNA version in cells or tissues (Fig. 1A, B). To validate the fidelity of the Gemini platform and its amplification capabilities, RT-PCR was used to measure the expression of negative-stranded mRNA in HEK293 cells transfected with either saRNA or saDNA (Fig. 1C). Notably, these transfection experiments were conducted without drug selection, demonstrating efficient uptake and expression. PCR products of the expected size were detected as nested PCR products from total RNA extracted from cells transfected with either saRNA or saDNA (Fig. 1D). The PCR products observed from the first round of PCR verifies that amplification occurred. To further ensure that the production of the negative-strand RNA was not due to primer-independent effects, no PCR products were found in either the initial PCR or subsequent nested PCR when the gene-specific forward primer was omitted during cDNA synthesis (Fig. 1D). This confirms the platform’s fidelity.

A Genomic map of the Gemini 1.0 vector. The vector contains a binary promoter (CMV and T7), replicon protein genes (NSP1-4), a 26S sub-genomic promoter from the Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus, and resistance genes for puromycin (PuroR) and ampicillin (AmpR) for mammalian and bacterial cell culture, respectively. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hfk8ebr). B Delivery mechanisms of Gemini as saDNA or saRNA. (Left panel) saDNA is delivered directly into the cell; it enters the nucleus for transcription then the resulting mRNA is transported to the cytoplasm for translation using the endogenous machinery to express its RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). (Right panel) saRNA is delivered into the cytoplasm for direct translation of its RdRp by the endogenous machinery. The RdRp then transcribes the payload mRNA, allowing for production of the payload protein. saRNA is transcribed in vitro via the T7 promoter with assistance from T7 polymerase. Also, 5’ capping is performed in vitro, before mRNA delivery into the cytoplasm for direct translation of RdRp and subsequent expression of payload mRNA. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hfk8ebr). C, D Establishing Negative-strand RNA synthesis is present post-transfection with naked saRNA-eGFP and naked saDNA-eGFP. C Detection strategy: First-strand synthesis is conducted using a NSP4 region specific primer (purple) with a random nucleotide tag (red) to produce positive strand (+) cDNA. The negative (-) RNA strand is then synthesized as cDNA using primers specific for the eGFP region (green) and the random nucleotide tag, producing a band of about 1.9 kb. A subsequent nested PCR (primers: dark green and fuchsia) then produces a band of 1.4 kb. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/8t59tko). D Expression of both Gemini saDNA and saRNA are demonstrated in vitro through PCR results shown on agarose gel: Total RNA was collected from HEK293 cells transfected with naked saRNA and saDNA expressing eGFP. Transfected HEK293 cells were grown in the absence of subsequent drug selection. Results of the first and nested PCRs are shown when the forward primer was used and not used (i.e., controls). The 1Kb Plus DNA Ladder (Froggobio) in lane 1 indicates the position and sizes of the molecular weight markers in base pairs (bp).

Both Gemini saRNA and saDNA drive protein expression in transfected cells

To validate Gemini’s ability to drive the expression of clinically relevant payloads, LNP-encapsulated Gemini constructs were initially used for direct comparison to mRNA vaccines, which are most often used in conjunction with LNPs. Subsequent experiments employed naked (non-encapsulated) Gemini constructs, as noted throughout the text. To test Gemini’s ability to drive protein expression, HEK293 cells were initially transfected with either LNP-encapsulated saRNA (LNP-saRNA) or LNP-encapsulated saDNA (LNP-saDNA), both expressing the spike protein from the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Transfection experiments were performed without drug selection to demonstrate the efficiency of uptake and expression (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis 6 days post-transfection confirmed the presence of protein bands of the expected size (Fig. 2B, C). These results were corroborated by flow cytometry performed over a 6 day time course, tracking the expression of spike protein in transfected cells.

A LNP-saDNA and LNP-saRNA expressing the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in HEK293 cells were compared with a conventional LNP-encapsulated plasmid DNA vector and to LNP-mRNA expressing the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on day 2 and 6. Transfected cells were cultured in the absence of subsequent drug selection. Controls were untransfected HEK293 cells. The same protocol was applied to LNP-mRNA expressing the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in a separate experiment. Each transfection was performed in duplicate (n = 2). (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). B Anti-spike Western blot at day 6 after transfection, and (C) Anti-spike Western blot of LNP-mRNA-spike expression over time. D Spike-expressing cells were stained with anti-spike antibody conjugated to Alexa-647, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis on day 2 and 6 post-transfection, using a BD Cytoflex flow cytometer. E Quantitated fraction of cells positive for spike protein (in percentage). Normally distributed data was subjected to student’s t-test and error bars represent standard deviation (SD). p-values are indicated on the graph and p-values <0.05 were considered significant using 95% confidence intervals.

By day two post-transfection, weak spike protein expression was observed in HEK293 cells transfected with LNP-saDNA (6.06% of the total cell population). By day six, this positive fraction significantly increased to 26.0%, suggesting self-amplification of LNP-saDNA (Fig. 2D, E). Similarly, cells transfected with LNP-saRNA showed weak spike protein expression at day two (5.89% of the total cell population). By day six, the positive fraction increased to 33.2%, indicating the self-amplification behaviour of LNP-saRNA (Fig. 2D, E).

In contrast, cells transfected in a separate experiment with a conventional LNP-encapsulated pseudouridine-modified mRNA (LNP-mRNA) encoding the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein initially showed 36.0% positivity for spike protein expression on day two. However, by day six, expression had rapidly waned, with only 6.08% of the cells remaining positive, which was a 6-fold reduction in expression (Fig. 2D, E) in vitro. The LNP-mRNA group experiment was performed separately from the saDNA and saRNA, allowing for only statistical comparisons within groups, however, the marked differences still demonstrate the short-lived expression of conventional mRNA in vitro.

Extended eGFP expression from LNP-encapsulated Gemini saDNA and saRNA in vitro

To compare the payload expression capabilities of the Gemini platforms in vitro, HEK293 cells were transfected with either LNP-saRNA or LNP-saDNA expressing eGFP (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis confirmed protein expression, revealing a protein band of the expected size on day 6 post-transfection and sorting (Fig. 3B). Two days post-transfection, the cells were sorted to obtain 100% eGFP-positive cells. Flow cytometric analysis was performed weekly for up to 4 weeks to assess the duration of expression (Fig. 3D).

A HEK293 cells were transfected with LNP-saDNA or LNPsaRNA expressing eGFP. Two days post-transfection, cells were sorted for eGFP positivity and cultured. eGFP expression was evaluated. Transfected cells were cultured in the absence of subsequent drug selection. Controls were untransfected HEK293 cells. The same protocol was applied to LNP-mRNA expressing eGFP in a separate experiment. Each transfection was performed in duplicate (n = 2). (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). B Anti-eGFP Western blot for LNP-saDNA-eGFP and LNP-saRNA-eGFP at day 6 after sorting, and (C) Anti-GFP Western blot for LNP-mRNA-eGFP expression over time. D Flow cytometric analysis was performed on day 2 post-sorting, then weekly up to 6 weeks to determine eGFP expression using a BD Cytoflex flow cytometer. E Quantitated fraction of positive cells (in percentage). eGFP positive LNP-saDNA and LNP-saRNA cells were compared temporally on day 14 and day 28 using unpaired Student’s t-test, and error bars represent SD. Likewise, eGFP positive LNP-mRNA cells were compared on day 2 and 6. p-values are indicated and p-values <0.05 were considered significant using 95% confidence intervals.

Cells transfected with LNP-saDNA were strongly positive for eGFP at day 14 (98%). By day 28, this positive fraction only slightly decreased to 93%, suggesting stable and long-term expression from the LNP-saDNA self-amplifying platform. In contrast, cells transfected with LNP-saRNA showed 85% positivity at day 14, but by day 28, this fraction significantly dropped to 64%, indicating less stability compared to LNP-saDNA. The difference in the fraction of positive cells between LNP-saDNA and LNP-saRNA was statistically significant at both 14- and 28-days post-transfection (Fig. 3E), with p-values of 0.0015 and 0.0025, respectively.

For comparison and in a separate experiment, cells transfected with conventional LNP-encapsulated pseudouridine-modified mRNA encoding eGFP initially exhibited high eGFP expression (93%) on day two post-transfection. However, by day six, there was a rapid decline in protein expression, as confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 3C), and flow cytometry revealed a near three-fold reduction in eGFP-positive cells (28%) (Fig. 3D). Although comparison between groups is not possible because of these separate experiments, temporal comparisons within each group again demonstrate the short-lived expression of LNP-mRNA, as the p-value for the unpaired t-test between day two and day six was 0.0001 (Fig. 3E).

The Gemini platform expresses payload proteins for an extended period in vivo

To evaluate the dynamics of gene expression in vivo, mice were intramuscularly injected with LNP-saRNA or LNP-saDNA constructs encoding eGFP. eGFP expression was assessed at multiple time points (14-, 28-, and 42 days post-injection) by analyzing muscle tissue (Fig. 4A). This analysis included both qualitative (Fig. 4B) and semi-quantitative assessments (Fig. 4C, D). In these experiments, the Gemini constructs were delivered in a lipid nanoparticle associated form.

A Mice (n = 3, per group per time point) were intramuscularly injected with LNP-saRNA, LNP-saDNA, LNP-plasmid DNA (pDNA) or LNP-mRNA encoding eGFP and were assessed for native eGFP expression both qualitatively and semi-quantitatively. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). B Qualitative analysis: Four sections per sample were assessed, and the one with highest eGFP intensity was chosen per sample; ImageJ software was used to calculate mean intensity and total area for each sample. Representative images shown only, for each group. C, D Four regions from the highest intensity section were selected at random, and subsequently quantified for eGFP intensity, also using Image J. Note, the background has been removed in graphs. C For LNP-saRNA, high levels of eGFP were observed 14 days post injection, with levels appearing reduced at subsequent time points. On the other hand, expression levels from LNP-saDNA continued increasing and appeared highest at the latest time point assessed, 42 days after injection. D Both the LNP-pDNA and LNP-mRNA drive lower eGFP expression in mouse muscle, at day 14 post injection, than LNP-saDNA or LNP-saRNA respectively. Data was subjected to Tukey’s test and error bars represent SEM. p-values <0.05 were considered significant using 95% confidence intervals. For images shown, magnification is 20X and the size bar = 2 mm.

For LNP-saRNA, high eGFP levels were observed 14 days post-injection, which then diminished at later time points (28 and 42 days). The differences were statistically significant compared to the negative control, with p-values < 0.05 for LNP-saRNA on day 14 and for LNP-DNA on day 42 (Fig. 4B, C). In contrast, LNP-saDNA exhibited a progressive increase in eGFP protein expression over time, peaking at 42 days post-injection (Fig. 4B,C). However, comparison of expression on day 14 post-injection showed that both LNP-saDNA and LNP-saRNA drove higher levels of eGFP expression than either LNP-plasmid DNA (pDNA) or LNP-mRNA, respectively.

Notably, eGFP expression from LNP-saDNA persisted robustly for up to 42 days, demonstrating a performance comparable to viral vector platforms, such as recombinant adenoviruses31 and vaccinia viruses32. Despite using a non-viral plasmid format, the self-amplifying saRNA technology in LNP-saDNA enabled long-term protein in vivo expression, lasting over 42 days. In contrast, LNP-saRNA appeared to be suited for applications requiring shorter protein expression durations, typically around 28 days. For example, LNP-saRNA could be used for transient protein therapies, such as short-term vaccination in prime–boost strategies or for driving the expression of proteins that promote tissue repair and regeneration, where prolonged expression is unnecessary.

In summary, both LNP-saRNA and LNP-saDNA constructs provided sustained eGFP expression, with LNP-saDNA demonstrating enhanced and prolonged activity. These findings underscore the potential of the Gemini platform for long-term therapeutic applications, offering significant advantages over conventional plasmid DNA (LNP-pDNA) and LNP-mRNA technologies.

Neither Gemini saRNA nor saDNA induce significant genomic integration

To assess the potential for genomic integration, 2-D gel-based methods were used to separate genomic DNA from extrachromosomal DNA33 and employed the properties of the restriction enzyme AscI to detect genomic integration in muscle tissue34. AscI cleaves DNA derived from prokaryotic cells but selectively ignores restriction sites that are CpG methylated in eukaryotic cells (Supplementary Fig. S6). An established agarose gel procedure, neutral-neutral 2D gel35,36, was utilized to distinguish between integrated and extrachromosomal nucleic acids to estimate the in vivo frequency of saRNA and saDNA integration in the genome of mouse muscle cells (Supplementary Fig. S7, Supplementary Table S1). While the saRNA format showed no detectable integration at the muscle injection site, the number of saDNA integrated copies was determined to be ~3.4 × 10-5 per cell genome. Such integration rate in muscle tissue is lower than that of plasmid DNA, (5 × 10-5)37, and adenoviruses, (6.7×10-5)38. As recombinant adenoviruses are widely used clinically and considered one of the safest vaccine vectors available38, this result demonstrates an excellent safety profile for saDNA and mitigates concerns about induced genetic abnormalities, such as those associated with lentiviruses and other commonly used retroviral expression systems (Supplementary Table S2). In conclusion, saRNA was demonstrated not to integrate into the host genome, while saDNA exhibited an integration frequency many orders of magnitude lower than the spontaneous somatic or germline mutation frequency observed in either mice or humans (Supplementary Table S1)39,40. These findings highlight the safety of the Gemini platform, with its integration rates well below thresholds associated with genomic risk, further emphasizing its potential for clinical use.

Stability of naked Gemini saDNA and saRNA to freeze-thaw cycles and lyophilization compared to conventional LNP-encapsulated mRNA vaccine

The stability of vaccine platforms is critical for determining their shelf life, distribution requirements, and overall efficacy. To evaluate the stability of the Gemini platforms in comparison to conventional LNP-mRNA, each vaccine encoding the spike protein from the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was tested against freeze-thaw cycles and lyophilisation.

Freeze-thaw

All three platforms were subjected to multiple freeze-thaw cycles between +20°C and -80°C, followed by analysis via agarose gel electrophoresis. For the freeze-thaw stability test, 2 µg of naked saDNA and saRNA, and 1 µg of LNP-mRNA were used. The LNP-mRNA samples, which had been shipped on dry ice and stored at 4°C overnight, were tested after being subjected to up to five freeze-thaw cycles, with each cycle involving freezing at -80°C and thawing at +20°C. Samples 1 through 5 represented increasing numbers of freeze-thaw cycles (ranging from two to five). Naked saDNA and saRNA samples were mixed with DNA or RNA loading dye and run on 1.2% agarose gels, while the LNP-mRNA samples were analyzed on 0.8% agarose gels to assess the stability of the large molecular weight LNP core structures (Fig. 5A).

A−D Thermal stability of naked saDNA and naked saRNA and a conventional LNP-pseudouridine substituted mRNA vaccines all encoding spike protein from the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A Cartoon of methodology for thermal stability testing. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). Stability of (B) naked saDNA, (C) naked saRNA, and (D) LNP-mRNA was compared after many cycles of freezing and thawing at −80°C and room temperature (RT) respectively. The stability of nucleic acids and lipid structures were examined. For the experiment, each vaccine sample (2 μg for naked saDNA and saRNA and 1 μg for LNP-mRNA, respectively) was subject to freezing and thawing up to 5 times in total (sample number one was frozen and thawed 2X, 3X, 4X and 5X, respectively) and the gel images were documented using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging system (Bio-Rad). E Band intensities of naked saDNA and naked saRNA; (F) Band intensities of intact LNP-mRNA and LNP-dissociated mRNA (free mRNA), where band intensities were semi-quantitated using ImageJ and plotted using GraphPad Prism (V10.1.1). G, H Effect of freeze-drying on different forms of vaccines. G Cartoon of methodology for freeze-drying. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). H Assessment of the effect of naked saDNA, naked saRNA and LNP-mRNA after freeze-drying (lyophilization).

Results indicate that both naked saDNA and saRNA maintained their structural integrity after five freeze-thaw cycles (Fig. 5B, C, E). In contrast, while the mRNA component of the LNP-mRNA remained intact, the LNP structure itself disintegrated after just a single freeze-thaw cycle, releasing free mRNA from the lipid nanoparticle core (Fig. 5D, F). This breakdown of the LNP likely results in the loss of the biological functionality typically provided by the encapsulation, thereby compromising the vaccine’s stability and efficacy.

Lyophilization

The stability of the three vaccine formats under freeze-drying (lyophilization) conditions was also assessed (Fig. 5G). Approximately 2.5 µg of each vaccine sample was freeze-dried in a total volume of 100 µL of Tris-Cl buffer, water, or PBS, using a Labconco FreeZone4.5 L -105C Complete Freeze Dryer System (720401000). The lyophilization parameters included solidification temperatures of -30°C to -40°C, pre-freeze temperatures of -40°C to -50°C, and a vacuum set point between 0.12 and 0.04. After freeze-drying, the samples were stored overnight at -20°C and reconstituted the next day. These reconstituted samples were analyzed on 0.8% TAE-agarose gels alongside non-lyophilized controls to evaluate their structural integrity (Fig. 5H).

The results from the freeze-drying experiments further confirmed the superior stability of the naked saDNA and saRNA formats. Both platforms were successfully reconstituted after freeze-drying without any loss of integrity, whereas the LNP-mRNA formulation failed to remain stable. Upon reconstitution, the LNP-mRNA disassembled into free LNP and mRNA, reinforcing the limitations of LNP-mRNA formulations under such conditions.

Both Gemini platforms exhibit significantly greater stability compared to conventional LNP-mRNA vaccines under both freeze-thaw and freeze-drying conditions. While LNP-mRNA demonstrated vulnerability, breaking down after a single freeze-thaw cycle and disassembling after lyophilization, both naked saDNA and saRNA retained their nucleic acid integrity, making them more robust candidates for vaccine development and distribution, particularly in challenging environmental conditions.

Dose selection for LNP-encapsulated and naked vaccine formulations

The selection of the optimal dose for the LNP-encapsulated Gemini-D and Gemini-R vaccines was guided by a comprehensive review of published literature on LNP-mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Prior studies have evaluated dose ranges between 0.01 µg and 10 µg, with higher doses generally correlating with enhanced immunogenicity. However, the difference in efficacy between 2 µg and 10 µg was not statistically significant41, indicating that a dose within this range would be sufficient to elicit a robust immune response.

Additional constraints influenced the dose selection, including the fixed nucleic acid-to-LNP ratio (2.5:1) required for formulation stability and the maximum allowable injection volume (25 µL per mouse) set by institutional animal care guidelines. Given these factors, 5 µg was determined to be the most suitable dose, which was confirmed in a dose titration study (Fig. 6B). Although this dose balances immunogenicity with formulation and administration limitations, these physiochemical and logistical constraints highlight critical yet often underappreciated factors in the development of LNP-based vaccines and immunotherapies.

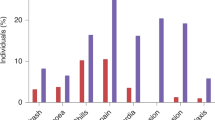

A Graphical outline of dose optimization experiment. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). Antibody responses in 15 week-old K18-hACE2 transgenic mice (n = 4-6 per group) to SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein vaccination using (B) LNP-encapsulated and (C) naked formulations of Gemini saDNA and saRNA. Various doses of the vaccine were tested. The antibody responses were also compared to normal saline injected control (data not shown). Normal serum from age-matched unvaccinated K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were used as background control in the ELISA (data not shown). One way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) statistical test was conducted between groups; ****<0.0001; *<0.01. Analysis and visualization of data was done using GraphPad Prism (10.3.1). D Graphical outline of inflammatory cytokine response experiment, where C57BL/6 J mice were injected intramuscularly in the hind leg with either mRNA-LNP, plasmid DNA, naked saRNA, or naked saDNA (n = 2 per group per timepoint). Serum and leg muscles were collected at 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h. An empty needle poke was included as a control at the 6-h timepoint. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). E−L Cytokine concentrations for TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using the Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) mouse inflammatory cytokine kit: (E−H) in serum and (I−L) at the site of injection (SOI) in leg muscles. Naked saDNA elicited a stronger TNF-α and IL-6 response than plasmid DNA and was comparable to cytokine levels observed for mRNA-LNP in both the serum and SOI. Analysis was performed with CBA Analysis Software, and data was visualized using GraphPad Prism (10.0.0). Normally distributed data was subjected to t-test and error bars represent SD. p-values are indicated on the graph and p-values <0.05 were considered significant using 95% confidence intervals.

To determine the optimal dose for naked (non-LNP) vaccines, a systematic dose titration study was performed (Fig. 6A, C). Various concentrations were tested, leading to the selection of 100 µg of naked saDNA and 25 µg of naked saRNA for the Gemini platform (Fig. 6C). These values were not arbitrarily chosen to favour naked formulations over LNP-encapsulated vaccines, but rather empirically derived based on immunogenicity data. This approach ensures that the selected doses were appropriate for subsequent comparative analyses between LNP-based and naked self-amplifying vaccine formulations, highlighting how both formulation and dosing strategies critically shape vaccine efficacy (Fig. 6).

Comparison of immune responses between different vaccine formulations

To evaluate the immune responses induced by various vaccine formulations, single dose titrations were performed to determine the optimal dose that elicited the maximal response. These doses were subsequently used to compare the immune responses of naked saDNA and saRNA formats with those of LNP-mRNA vaccines.

First, the short-term cytokine expression by injecting animals intramuscularly and sacrificing them at 2-, 4-, and 6 h post-inoculation was examined. Muscle tissue from the injection site and serum samples were collected for analysis (Fig. 6D). Results indicated that the saDNA group elicited a robust cytokine response, with levels continuing to increase up to the 6-h mark, suggesting a sustained immune response over time. In comparison, the saRNA group exhibited a non-inflammatory, immune-modulating cytokine profile. The mRNA group showed the lowest cytokine levels, while the saDNA group demonstrated the strongest overall response, potentially increasing further with time (Fig. 6E–L). This pattern was consistent with the antibody and T-cell responses observed in subsequent assays.

LNP encapsulation is not required to achieve potent immunogenicity from Gemini saDNA or saRNA vaccines

Current RNA vaccine platforms generally rely on lipid nanoparticle (LNP) encapsulation to protect mRNA or saRNA from RNAse digestion, which adds complexity and cost to the manufacturing process19. Previous studies have demonstrated that LNP encapsulation is necessary for inducing an equivalent antibody response, as shown with the HIV-1 Env gp140 protein model antigen23,40. In contrast, the goal here was to determine whether LNP encapsulation is essential for the immunogenicity of Gemini saDNA and saRNA vaccines using eGFP as a model antigen.

To assess this, the antibody responses of naked and LNP-encapsulated versions of the Gemini formats expressing eGFP in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice was compared (Fig. 7A). A higher dose of naked saDNA (50 µg) outperformed 5 µg of LNP-saDNA in inducing antibody responses (p = 0.0105 vs. p = 0.4038; Fig. 7B). Similar trends were observed for naked saRNA (p = 0.0420) compared to LNP-saRNA (p = 0.3270) (Fig. 7C). This indicates that higher doses of naked formulations can generate strong immune responses to eGFP comparable to, or even exceeding, those of lower-dose LNP-encapsulated versions.

A Graphical outline of the experiments. A single dose of the vaccine constructs (naked saDNA, naked saRNA, LNP-saRNA, LNP-saDNA, or LNP-mRNA) were injected into 15 week-old K18-hACE2 mice (n = 6 per group): and then blood and spleens were collected on day 28. Vaccine payloads were either eGFP or SARS-COV-2 Omicron Spike. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). B−E ELISAs specific for the payload protein were used to measure IgG responses from serum. Normal serum from age-matched unvaccinated K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were used as background control for ELISAs. B ELISA comparison of IgG antibody responses to naked (50 µg) and encapsulated (5 µg) versions of saDNA with eGFP payload. C ELISA comparison of antibody responses to naked (50 µg) and encapsulated (5 µg) versions of saRNA with eGFP payload. D Comparison between IgG antibody response to naked saDNA (100 µg), naked saRNA (25 µg), and LNP-mRNA (5 µg) vaccine in mouse serum 28 days post-injection, where the payload was Omicron spike. Analysis of Variance (one way ANOVA) was conducted between all the groups including normal saline. Multiple comparisons were done comparing normal saline to each group using Dunnett’s post-hoc test. E Comparison between antibody response to LNP-saDNA (5 µg), LNP-saRNA (5 µg), and LNP-mRNA (5 µg) vaccine in mouse serum 28 days post-injection: IgG response. The antibody responses were also compared to the normal saline injected control. Normal serum from age matched unvaccinated K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were used as background control in the ELISA. Analysis of Variance (one way ANOVA) was conducted between all the groups including normal saline. Multiple comparisons were done comparing normal saline to each group using Dunnett’s post-hoc test. F−K ELISPOTs (IFN-γ, IL-4, TNF-α) were used to measure T cell responses to the Omicron spike vaccine payloads. Single cell suspensions of harvested splenocytes were activated with LPS and antigen-presenting cells before being incubated with SARS-CoV-2 spike peptides. For all graphs, Analysis of Variance (one way ANOVA) was conducted between all the groups including normal saline (data not shown), and multiple comparisons were done comparing normal saline to each group using Dunnett’s post-hoc test. F, G IFN-γ ELISPOT response. H, I IL-4 ELISPOT response. J, K TNF-α ELISPOT response. For all graphs, p-values shown on graph; error bars represent SEM.

We extended our studies by analysing IgG responses in mouse serum 28 days post-injection while comparing naked and LNP-encapsulated formulations of Gemini saDNA, saRNA, with benchmark LNP-mRNA vaccines, all encoding Omicron Spike. Across all comparisons, the naked saDNA group stood out, producing a significantly higher IgG response (p = 0.0006). Although naked-saRNA (0.0084) and LNP-mRNA vaccines (0.0125) also showed significantly higher responses than the control, their responses were numerically lower than the naked saDNA (Fig. 7D). While comparing the LNP versions of Gemini vaccines, again the LNP-saDNA group stood out (p = 0.0028) (Fig. 7E). These results were further supported by cytokine analysis, where the IFN-γ ELISPOT response indicated a stronger T cell response in the naked saDNA group (p = 0.0010) compared to the other vaccine formats (Fig. 7F, G).

Both LNP-encapsulated and naked formulations of Gemini saRNA performed similarly in eliciting IL-4 and TNF-α ELISPOT responses (Fig. 7H–K). This suggests that LNP encapsulation may not be necessary for eliciting robust immune responses with Gemini vaccines and higher doses of the naked versions can compensate for the absence of encapsulation.

In conclusion, maximal T cell responses was achieved through vaccination with naked or LNP-encapsulated Gemini saDNA and saRNA formats, demonstrating that the naked Gemini vaccines can achieve comparable immunogenicity with appropriate dosing. These findings highlight the potential for simplifying vaccine manufacturing by omitting LNP encapsulation without compromising immunogenicity.

Significant antibody response induced by both Gemini SARS-CoV-2 spike naked saRNA and naked saDNA vaccine formats

To assess the type of antibody response induced, K18-hACE2 transgenic mice, which express the human ACE2 receptor for SARS-CoV-2, were injected with saRNA or saDNA vectors encoding the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Fig. 8A). A 5 µg dose of each LNP-encapsulated vaccine formulation or a 50 ug dose of each naked vaccine formulation was administered.

A−C Naked saDNA primarily induces IgG antibodies, while naked saRNA primarily induces IgM antibodies. A A single dose of either naked saDNA or naked saRNA expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was injected intramuscular (IM) route into 15 week-old K18-hACE2 mice (n = 4 per group). (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). Antibody concentrations were measured in mouse serum 28 days post-injection for (B) IgG responses, and (C) IgM responses. Error bars represent SEM. D, E Antibody longevity in vivo. To determine if vaccination with either naked saDNA or saRNA formats could result in extended and strong antibody responses, a time-course study was conducted to evaluate this point. D Age-matched K18-hACE2 female mice (n = 6 per group) susceptible to SARS-Cov-2 were injected with a single dose of nucleic acid vaccines through intramuscular (IM) route of injection on day 0. Mice were bled and serum collected on the indicated time points. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). E IgG antibody levels to Omicron spike protein were assessed. ELISA Analysis of Variance (one way ANOVA) was conducted between all the groups including normal saline. Multiple comparisons were done comparing normal saline to each group using Dunnett’s post-hoc test. None of the p-values for naked saRNA were significantly different from the normal saline control. Error bars represent SEM. F, G Neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 pseudo typed virus infected cells. F Neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-Cov-2 were measured using a pseudo typed virus and compared between naked-saRNA vaccine and the naked-saDNA vaccine using serum samples 42 days post-injection (n = 2 per group). The antibody responses were normalized to the normal saline injected control. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). G The data was plotted on a linear scale and paired t-test was conducted between the groups. All treatment groups showed statistically significant differences compared to the unvaccinated control group. Error bars represent SD.

In line with flow cytometry data, the IgG response in serum from mice vaccinated with naked saDNA on day 28 was significantly greater than in the unvaccinated control group (p = 0.0046; Fig. 8B). Although the IgG response to the naked saRNA vaccine was lower than naked saDNA, it still remained higher than the unvaccinated group (p = 0.1019). Conversely, the IgM response exhibited the opposite trend, with significantly higher levels generated by the naked saRNA format (p = 0.0429) compared to the control group (Fig. 8C). In contrast, the naked saDNA vaccine produced a much lower IgM response and was not elevated (p > 0.9999) when compared to the control group (Fig. 8C). Neither vaccine format induced a significant IgA antibody response, and no observable toxicity such as weight loss was detected (p > 0.05, data not shown).

While absolute quantitative estimates of antibody responses are scarce in clinical literature, a few studies38,42 provide relevant comparisons43,44. These studies, which tested thousands of patients, support the findings that LNP-saRNA and LNP-saDNA formats elicit strong antibody responses. Quantitatively, both LNP-saRNA and LNP-saDNA formats produced significantly higher IgG concentrations (400−800 ng/mL) after a single 5 µg dose, compared to the ~200 ng/mL observed in patients recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infections42.

In conclusion, the Gemini saRNA format may offer advantages in vaccine applications where IgM plays a critical role, while Gemini saDNA appears more effective for eliciting strong IgG responses. These differences could be attributed to the distinct Toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling pathways activated by RNA and DNA45, suggesting that the two Gemini formats provide the flexibility to fine-tune immune responses, depending on the desired antibody profile, either IgG or IgM dominant.

Durability of antibody responses induced by naked saDNA and saRNA vaccines

To evaluate the duration of antibody responses elicited by naked saDNA versus saRNA vaccines, a time-course study was conducted (Fig. 8D). Results showed that naked saRNA vaccines induced durable antibody responses for up to 42 days before a noticeable decline (Fig. 8E). In contrast, naked saDNA vaccines maintained robust antibody responses for at least 70 days before beginning to wane (Fig. 8E). Therefore, naked saDNA vaccines demonstrated a longer lasting and more durable antibody response compared to naked saRNA vaccines and were selected for subsequent viral challenge experiments.

Neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 pseudo typed virus

Significant neutralization antibody titers were measured (Fig. 8F) using the SARS-CoV-2 pseudo typed virus titration assay, with similar levels observed between naked saDNA and naked saRNA vaccines (Fig. 8G), as normalized to saline control. This data underscores that naked vaccines induce high-titer antibody responses, trigger cytokine responses, and generate durable, long-lasting immunity.

Effectiveness of naked saDNA in reducing viraemia post-challenge

To assess whether naked saDNA vaccines could outperform LNP-encapsulated saDNA and potentially eliminate the need for LNP delivery systems, a viral challenge experiment was conducted using Delta SARS-CoV-2 and compared the protection given by LNP-encapsulated and naked Omicron-Spike saDNA vaccines. Mice were vaccinated intramuscularly with either LNP-saDNA or naked saDNA on days 0 and 28. After a 5 day interval following the second dose, the mice were challenged with SARS-CoV-2 and euthanized 5 days post-challenge. Blood samples were analyzed for viraemia levels, focusing on nucleocapsid protein concentration (Fig. 9A).

To conclusively establish whether naked saDNA could outperform LNP-saDNA and potentially replace the need for LNP inclusion, a viral challenge experiment was carried out to directly compare the efficacy of LNP-saDNA with that of naked saDNA. A K18-hACE2 mice susceptible to SARS-Cov-2 (n = 5 per group) were injected intramuscularly (IM) with either LNP-saDNA Omicron Spike or naked saDNA Omicron Spike on days 0 and 28. Mice were challenged 5 days post-boost and sacrificed 5 days later. Sera was collected and subjected to ELISA to assess blood viraemia levels based on the concentration of viral nucleocapsid protein. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e32c216). B The viral nucleocapsid concentration in naked saDNA vaccinated mouse blood was significantly different than the unvaccinated control group using unpaired t-test. C The LNP-saDNAgroup was significantly different than the unvaccinated control group using unpaired t-test.

A statistically significant reduction in nucleocapsid protein levels was observed in the serum of mice vaccinated with naked saDNA compared to unvaccinated controls, as determined by an unpaired t-test (p = 0.0041) (Fig. 9B). In comparison, the LNP-saDNA group also showed a significant difference from the control group (p = 0.0230) (Fig. 9C). This study underscores the importance of reduced viraemia, which is closely associated with the severity of COVID-19 and serves as a key indicator of vaccine efficacy. Demonstrating a significant reduction in viraemia supports the potential of naked saDNA vaccines in advancing towards effective sterilizing vaccines.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the Gemini platform represents a promising innovation in vaccine technology by overcoming critical limitations of conventional mRNA1,2,3,30 DNA46, adenoviral47, vaccinia48, and protein-based vaccines49. The Gemini platform combines saRNA (self-amplifying RNA) and saDNA (self-amplifying DNA) formats in a single expression system and offers several notable advantages, including safe delivery, support for larger payloads, the ability to benchmark saRNA and saDNA expression for the same payload, prolonged protein expression, strong neutralizing responses from a single vaccine dose, elimination of dependence on LNPs (lipid nanoparticles), enhanced stability, and simplified manufacturing, storage, and distribution (Fig. 10). Collectively, these features establish Gemini as a versatile platform with broad applications in the development of vaccines and therapeutics.

Challenges of Conventional mRNA Vaccines: Although conventional mRNA vaccines were instrumental in mitigating COVID-19 mortality, their widespread deployment was constrained by technological hurdles such as limited molecular stability, complex and intricate manufacturing processes, and a dependency on lipid nanoparticle (LNP) encapsulation, which posed challenges for production, storage, and global distribution, particularly in resource-limited settings. Overview of Gemini Platform: The Gemini platform represents a novel innovation that employs a bifunctional eukaryotic–prokaryotic promoter, functioning both as a self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) and a self-amplifying DNA (saDNA) replicon, thereby enabling robust amplification and expression of genetic cargo while addressing key limitations of conventional mRNA vaccines. Stability and Storage: Unlike conventional mRNA vaccines that degrade after one freeze-thaw cycle, Gemini demonstrates exceptional stability through five freeze-thaw cycles and can be freeze-dried for powder storage and aqueous reconstitution. LNP Elimination: A critical advantage is bypassing LNP encapsulation requirements essential for conventional mRNA vaccines, simplifying manufacturing, reducing costs, and mitigating LNP-associated toxicity and adverse reactions. Cold Chain Management: While LNP-mRNA vaccines require -20°C to −80°C storage, Gemini formulations remain stable at 2°C to 8°C, reducing logistical challenges in remote settings. Extended Protein Expression: Gemini offers prolonged protein expression exceeding 28 days versus 3 days for conventional mRNA, supporting robust sustained immune responses including humoral antibodies and T-cell responses. Payload Capacity: Capacity reaches 16−20 kb, far exceeding mRNA’s 4 kb limit, enabling complex protein expression and multivalent vaccine development. Safety and Integration: The safety profiles are highly favourable, with integration risks at least five orders of magnitude below FDA-established safety limits. Naked Gemini formats elicit durable antibody responses and demonstrate potential for reducing SARS-CoV-2 viremia and limiting transmission. (Created in BioRender. Fan J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/lrkpjt4).

Importantly, while conventional naked plasmid DNA and RNA vaccines have been explored previously, Gemini’s dual platform is mechanistically distinct in that it leverages self-amplifying DNA (saDNA) and RNA (saRNA) to overcome the nuclear entry and transcriptional inefficiencies that limit conventional plasmid DNA vaccines. Many conventional plasmid vaccines include components derived from SV-40, a simian virus known to carry sequences capable of integrating into host genomes or activating oncogenes, raising long-term safety concerns that are still debated50. By contrast, Gemini contains no SV-40 components, making it inherently safer. Host genome integration rates for Gemini saDNA are lower than those reported for plasmid DNA and adenoviral vectors, and over 5 orders of magnitude lower than the spontaneous germline or somatic mutation rates in mice or humans. Gemini saDNA integration rates remain well below thresholds associated with genomic risk, further supporting its potential for safe clinical use (Supplemental Fig. S7, Supplemental Tables S1 and S2) and Gemini saRNA shows no detectable integration. Moreover, unlike conventional plasmids such as those used in ZyCoV-D, which is delivered via a needle-free injector and given as three 2 mg intradermal doses on Days 0, 28, and 5646, saDNA can be delivered without such an injector and generates replicons that sustain and amplify antigen expression, decoupling immunogenicity from the single input dose. This feature is reflected in the dose-ranging studies, which demonstrate efficient adaptive immune responses at doses significantly lower than conventional DNA vaccines when normalized to functional antigen yield46.

Studies on the Gemini platform demonstrate that, while LNP encapsulation improves transfection efficiency resulting in lower doses, self-amplifying nucleic acids can achieve robust and durable expression without the need for LNP encapsulation. While recent advances in mRNA vaccine technology have incorporated nucleoside modifications such as N1-methylpseudouridine to attenuate innate immune recognition and reduce inflammatory signalling51, the lipid nanoparticles employed for delivery remain intrinsically reactogenic and have been associated with injection-site inflammation and systemic adverse events52,53. The fact that Gemini does not need LNPs to deliver its payload into the cell has several important implications: it may lower the risk of inflammation and related side effects, broaden the range of patient populations who can safely receive nucleic acid–based vaccines, and simplify manufacturing and distribution by obviating the need for specialized microfluidic mixing technologies required for LNP formulation19. In addition, LNPs instability, cold-chain dependency, and manufacturing complexity and associated costs remain major barriers to equitable vaccine distribution21,22,54. By contrast, the Gemini platform offers lyophilization stability, ambient storage, and flexible delivery without specialized equipment, addressing critical global health implementation challenges. In particular, the Gemini formats demonstrate exceptional stability through multiple freeze/thaw cycles and freeze-drying processes (Fig. 5), removing the need for ultra-low storage temperatures and easing distribution logistics, particularly in remote or resource-limited settings. By eliminating these constraints, Gemini could facilitate global vaccine deployment, particularly where cold-chain requirements and formulation complexity pose major barriers.

Crucially, the Gemini platform significantly overcomes a key limitation of LNP-encapsulated nucleic acid vaccines: payload size constraints. Li et al.21 used single-particle imaging (CICS) on a benchmark DLin-MC3-DMA LNP formulation and observed that many particles were empty, while most loaded LNPs contained only ~2 mRNA molecules ( ~ 1.9 kb each), corresponding to ~2–4 kb of total payload per particle. Typically, clinical-grade LNPs encapsulate two–five RNA copies, corresponding to payloads of ~2–5 kb, with aggregate upper limits reaching ~10 kb total per particle under optimized conditions21,22,54. By contrast, a single Gemini vector construct can support expression of a genetic payload of 19 kb (manuscript in preparation), thereby exceeding the inherent payload limitations of traditional mRNA vaccines and enabling delivery of larger, more complex therapeutic sequences for multifarious diseases.

In this study, Gemini payloads encoding either eGFP or the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein were used as model antigens in this study: eGFP enabled direct evaluation of protein expression, whereas SARS-CoV-2 Spike allowed assessment of immune responses in a biologically relevant context, providing proof-of-concept for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Critically, while a conventional Promab LNP-pseudouridine-substituted mRNA vaccine (similar to Moderna’s Spikevax (mRNA-1273)1,2 and Pfizer–BioNTech’s Comirnaty (BNT162b2)3) shows peak in vivo expression in muscle (Fig. 4) within 2 days followed by rapid decline by days 6-7, Gemini platforms provide sustained payload expression over 4 weeks for saRNA and over 6 weeks for saDNA. The transient expression of conventional LNP-mRNA may correlate with observed rapid immunity decline following LNP-mRNA vaccination55,56. The sustained expression profile of Gemini platforms aligns with requirements for prolonged antigen exposure to induce robust B and T lymphocyte responses39,40. Notably, Gemini exhibits a biphasic expression pattern characterized by an initial transient phase followed by a secondary surge in expression. This pattern may result in higher cumulative protein levels compared with conventional constructs and represents a potentially underappreciated biological advantage of self-amplifying systems for vaccine and therapeutic delivery. The data further demonstrate that LNP-encapsulated saDNA supports in vivo expression for over 42 days, comparable to viral vector platforms, whereas LNP-saRNA yields shorter expression windows of ~28 days (Fig. 4), making it more suitable for transient applications. This tunable duration of expression underscores the versatility of the Gemini platform in addressing both long-term therapeutic needs and short-term interventions, thereby extending the scope of nucleic acid vaccines and therapeutics beyond the capabilities of current LNP-mRNA and pDNA systems.

The vaccine efficacy experiments conducted in this study, using a single priming dose without boosting, demonstrate strong performance in three critical indicators: antibody production, T-cell response and viremia reduction. Single doses of either Gemini platforms can exceed antibody endpoint titers to mRNA-1273 vaccines despite eliminating LNPs (Fig. 6). Antibody titers, measured using three-fold serum dilutions, ranged from 1:720 to 1:2160, meeting or surpassing titers reported in humans following mRNA-1273 vaccination57,58,59,60. These results are particularly encouraging in light of the differences between preclinical mouse models and clinical contexts61,62. Analysis of single dose, T lymphocyte responses demonstrated significant increases in gamma-interferon expressing T cells recognizing B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein epitopes (Fig. 7). Notably, for T cell responses, both naked self-amplifying Gemini (without LNP) and LNP-encapsulated Gemini vaccines exceeded the benchmark LNP-mRNA vaccine, demonstrating that self-amplifying systems elicit stronger responses than conventional LNP-mRNA formulations, and that, with appropriate dosing, effective immune responses can be achieved in the absence of LNPs. Generally, in these studies, saDNA constructs favoured Th1 responses while saRNA constructs favoured Th2 responses, with both eliciting stronger responses than conventional LNP-mRNA formats (Fig. 7 F-K); overall, the Gemini platform elicited robust T cell immunity targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike variants. Finally, in viral challenge experiments, a single dose of the naked saDNA vaccine reduced SARS-CoV-2 viremia by 91%, markedly exceeding the 68% reduction achieved with LNP-encapsulated vaccines (Fig. 9B, C). As reduction in viremia is a critical predictor of clinical outcomes and COVID-19 severity63,64,65, these results, combined with high neutralization titers exceeding WHO guidelines, demonstrate the Gemini platform’s dual efficacy in both reducing pathogen replication and eliciting robust protective immunity. In addition, they were achieved with a single dose, suggesting that future prime-boost regimens could further potentiate immune responses.

The robust performance of the naked saDNA format, coupled with the platform’s demonstrated immunogenicity and safety profile, establish Gemini vector-based spike vaccines as highly promising SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates. However, cross-species comparisons of IgG levels should be interpreted with caution due to fundamental differences in antibody kinetics, isotype distributions, and measurement sensitivities between mouse and human immune systems. Mouse IgG responses typically peak earlier and may show different magnitude patterns compared to human responses. Additionally, species-specific differences in antibody glycosylation, half-life, and epitope recognition may affect both the absolute values measured and the functional significance of observed titers66. These comparisons are presented for illustrative purposes to demonstrate relative immune response patterns rather than direct quantitative equivalence with clinical performance. Despite these caveats, these studies are highly encouraging and suggest that the Gemini platform could deliver scalable and broadly accessible vaccines while exceeding immunogenicity benchmarks established by mRNA vaccines. Finally, these findings demonstrate that effective vaccination can be achieved without LNP encapsulation, challenging prevailing paradigms in nucleic acid delivery.

Overall, the innovative features of Gemini position it as a disruptive and versatile next-generation alternative that preserves efficacy while addressing key technical, logistical and regulatory challenges of current nucleic acid vaccines. Gemini offers wide potential for scalable therapeutic applications in molecular medicine and the possibility of advancing vaccine democratization, thereby enhancing global healthcare and pandemic preparedness while promoting equitable access and improved health outcomes.

Methods

Mice and ethical approval

K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were (Jackson Laboratory, 034860) maintained in the Centre for Disease Modelling at the University of British Columbia (UBC). These experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee at UBC, who is responsible for ensuring that all UBC animal researchers conform to the mandatory guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The mice challenged with SARS-CoV-2 were maintained at the Toronto High Containment Facility level 3 (THCF) at the University of Toronto. These experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee (University of Toronto), and also maintained and euthanized under humane conditions in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Mice were maintained under 12 hr light/dark cycles at 20°C ambient temperature.

Vector synthesis and preparation of saDNA and saRNA

Fig. 1A illustrates the map of the vector system discussed in this paper, hereinafter referred to as Gemini 1.0. It is based on the T7-VEE-GFP plasmid, a generous gift from Professor Steven Dowdy, at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine,12. The vector consists of the NSP1-4 genes from the Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus, an origin of replication site, a bacterial promoter (26S subgenomic promoter), an Ampicillin resistance (AmpR) gene acting as a selection marker for bacterial culture, a T7 promoter to recruit T7 RNA polymerase for saRNA synthesis, and a human CMV enhancer/promoter, allowing its use as a DNA or RNA vector in humans. The CMV promoter was subsequently cloned into the T7-VEE-GFP plasmid by Synbio Technologies. For the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Spike variant of SARS CoV-2 and B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and eGFP sequences (see Supplementary Fig. S1–5).

The Gemini 1.0 vector was transformed into DH5α Competent E. Coli (NEB, C2987), and plated onto Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing Ampicillin for selection; this was followed by overnight culturing in LB broth at 37°C. Vector DNA was extracted according to the EZ10 Plasmid DNA Minipreps Kit protocol (BioBasic, BS6149). This constituted the naked saDNA version of the Gemini 1.0 platform. To prepare the naked saRNA version, the Gemini 1.0 vector underwent in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase (NEB, M0251L), followed by in vitro 5’ capping and 3’ polyadenylation. Figure 1 describes the self-amplifying platform pathways and in vitro replication process for both the DNA and RNA forms.

mRNA preparation

Pseudouridine substitute LNP-encapsulated mRNAs encoding eGFP (PM-LNP-21) or LNP-B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (PM-LNP-12) mRNA were purchased from Promab Biotechnologies (Richmond, CA, United States). These LNP’s were formulated by Prolab with SM-102, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 at optimal molar concentration for a high rate of encapsulation and efficient mRNA delivery.

The conventional plasmid (pDNA) was either pCMV-T7-EGFP (addgene, plasmid 133962) or pCMV-Spike (addgene, plasmid 173921).

Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) formulation of Gemini saDNA and saRNA formats

The 5 µg dose of Gemini saDNA and saRNA was selected based on a thorough review of published literature on LNP-mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Previous studies have utilized doses ranging from 0.01 µg to 10 µg, with higher doses generally yielding better immunogenicity. However, the difference in efficacy between 2 µg and 10 µg was not statistically significant, suggesting that a dose within this range would be optimal. Additionally, the formulation required a fixed nucleic acid-to-LNP ratio of 2.5:1, which further constrained the selection of an appropriate dose, with 5 µg being the maximum feasible concentration. Moreover, animal facility guidelines imposed a strict maximum injection volume of 25 µL per mouse, limiting the total amount of vaccine that could be administered. Considering these factors, a 5 µg dose was determined to be the most appropriate for the LNP-based vaccine formulations. These constraints represent an often-underappreciated aspect of all LNP-encapsulated vaccines and immune therapies23.

The Encapsula GEN-7036 formulation, which contains a permanently charged cationic lipid (DOTAP-based), was chosen because it does not require a confined impinging jet (CIJ) turbulent mixer like Moderna Spikevax (mRNA-1273)1,2 and Pfizer–BioNTech’s Comirnaty (BNT162b2)3, and other vaccine formulations use. Instead, it can be mixed with nucleic acids at room temperature, and be freshly prepared just prior to injection. Unlike traditional LNPs that encapsulate nucleic acids within their core, permanently cationic formulations such as GEN-7036 primarily associate the nucleic acids on the particle surface. Furthermore, in preliminary head-to-head comparisons, the Encapsula GEN-7036 formulation produced higher antibody levels than the mRNA-1273-like ionizable SM-102 lipid nanoparticle formulation of the same vaccine and dose prepared using CIJ by the CDMO (Ardena Group Ltd.) (manuscript in preparation). Thus, LNP-encapsulated forms of Gemini saDNA and saRNA were prepared by mixing 5 µg of saDNA or saRNA with 18 µL of Genesome lipid solution (DOTAP:Chol:DOPE in a 1:0.75:0.5 ratio; Encapsula Nano Science, GEN-7036) in a 1:2 volume ratio at room temperature as described by the manufacturer. LNP-encapsulated nucleic acids were kept on ice until ready for injection.

LNP-mRNA preparation

Pseudouridine substitute LNP-encapsulated mRNAs encoding eGFP (Promab Biotechnologies, PM-LNP-21) or LNP-B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Promab Biotechnologies, PM-LNP-12) mRNA. These LNP’s were formulated by Promab Biotechnologies with SM-102, DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 at optimal molar concentrations for a high rate of encapsulation and efficient mRNA delivery.

HEK293 cell culture and transfection with Gemini

HEK293 cells (ATCC; CRL-1573) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, 11965-092) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Gibco, A3160702) and 1:100 dilution of penicillin/streptomycin solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, 15140122). Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate 1 day prior to transfection. Transfection was performed with ~2.5 µg of either Gemini saDNA or saRNA using the Lipofectamine™ 3000 protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific, L3000001) and was carried out without drug selection to either kanamycin or puromycin resistance encoded by the Gemini 1.0 vector.

Negative (-) strand mRNA detection

HEK293 cells were harvested 72 h post-transfection. Total RNA was extracted using the PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Ambion, 12183025), and its integrity was checked on a 0.8% agarose gel. Molecular weight marker used was 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (Froggabio, DM015. Thereafter, total RNA was treated with amplification grade DNase I (Invitrogen, 18068015) to remove any residual DNA, followed by first strand cDNA synthesis using either a NSP4 gene-specific forward primer with a random nucleotide tag sequence (5’-cggtcatggtggcgaataaGCGGCCTTTAATGTGGAATG-3) or without any primer according to the SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase protocol (Invitrogen, 18080044). cDNA synthesis was then completed followed by a PCR using an eGFP gene-specific reverse primer (5’-CACCTTGATGCCGTTCTTCT-3’) and the random nucleotide tag-specific forward primer (5’-cggtcatggtggcgaataa-3’) to produce a 1.9 kb band which would be an indication of negative RNA strand. A nested PCR using the forward primer, 5’- CCGAGAGCTGGTTAGGAGATTA-3’, and reverse primer, 5’-GCTTGTCGGCCATGATATAGA-3’ on the first PCR product was then performed to amplify cDNA with a band size of 1.4 kb to verify the correct target sequence (see Fig. 1C). PCRs were run on a Bio-Rad T100 Thermocycler and parameters used for both PCRs were: 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, for 28 cycles.

Flow cytometry sample preparation

HEK293 cells were transfected with either: a) Gemini saDNA expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, or b) a non-self-amplifying DNA plasmid control expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike, or c) LNP- B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus mRNA, or d) the conventional LNP-encapsulated Pseudouridine substitute mRNAs encoding the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, (see Fig. 2 for method overview). Cells were harvested at 2- and 6 days post-transfection as were the FACS samples and resuspended in FACS buffer at a concentration of 1.0 × 106 cells/mL. Subsequently, cells were incubated in FACS buffer for 30 min at 4°C for Fc blocking, centrifuged (240 x g for 4 min at 4°C), and then stained with an anti-receptor-binding domain (RBD) SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (1:100; Invitrogen, 51-6490-82) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Cells were then washed in FACS buffer by centrifuging at 240 x g for 4 min at 4°C) and resuspended in FACS buffer (500 uL/tube). Data was acquired using a BD Cytoflex flow cytometer.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) sample preparation

HEK293 cells were transfected with either: a) Gemini saDNA expressing eGFP, or b) Gemini saRNA expressing eGFP, or c) LNP-encapsulated pseudouridine-substituted mRNAs encoding eGFP (Promab Biotechnologies, PM-LNP-21). Two days post-transfection, cells were sorted for eGFP expression. Cells were then harvested at 14- and 28 days post-transfection using Cellstripper® (Corning, 25-056-CI), and counted using a TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad, 1450102), assessing live cells with a 1:1 dilution with 0.4% Trypan Blue (Gibco, 15250-061). Cells were then resuspended in FACS buffer (1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 2% FBS and 2% normal rabbit serum) at a concentration of 1.0 × 106 cells/mL and incubated in FACS buffer for 30 min at 4°C for Fc receptor blocking. Blocked cells were again centrifuged at 240 x g for 4 min at 4°C, and resuspended in FACS buffer (500 µL/tube).

Western blot

HEK293 cells were transfected with either: (a) Gemini saDNA or saRNA expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike, or (b) Gemini saDNA or LNP-encapsulated pseudouridine-substituted mRNAs encoding eGFP (Promab Biotechnologies, PM-LNP-21), or (c) LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike variant of SARS-CoV-2 (Promab Biotechnologies, PM-LNP-12). Cells were harvested 72 h post-transfection, lysed in 2X sample buffer supplemented with 5% β-Mercaptoethanol (BME; Bio-Rad, 1610710), and heated at 90°C for 10 min. Subsequently, samples were treated with Benzonase nuclease (Sigma, E1014) for 3 h to remove nucleic acids. A total of 30 µg of protein per well was loaded onto a 4-15% precast SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, 4561083). SDS-PAGE gels were run on the Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN® Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis Cell and the running conditions were as follows: 75 V for 20 min, then 120 V for 2 h, in running buffer (100 mM Tris, 100 mM Tricine, 0.1% SDS). Molecular weight marker used was BLUelf Prestained Protein Ladder (Froggabio, PM008). For Western blot, protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the Bio-Rad Trans-Blot® Cell at 75 V for 3 h in Towbin buffer (2.5 mM Tris, 19.2 mM glycine, 2% (v/v) methanol). Subsequently, the membrane was washed in 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS (PBST), followed by blocking with 5% skim milk in 1% PBST for 2 h. Primary antibodies for ALFA Tag (Nano-tech, N1581) and eGFP (ThermoFisher Scientific, GFP-101AP) were diluted 1:5000 and incubated with the membrane at 4°C overnight. The membrane was then washed three times for 10 min each with 0.1% PBST. Anti-rabbit (ThermoFisher Scientific, 31460) and anti-mouse (Abcam, AB205719) secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were diluted 1:5000 and incubated with the membrane at room temperature for 1 h, followed by three 10 min washes of 0.1% PBST. Subsequent signal detection was conducted on a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Qualitative determination of eGFP expression in injected mouse leg muscles

Two groups of nine 6–12 week-old K18-hACE2 mice were injected with 5 µg of either LNP-saRNA or LNP-saDNA expressing eGFP, by intramuscular injection into the caudal thigh muscle. For each group, mice were sacrificed, at 14, 28 or 42 days post-injection (n = 3 per day of sacrifice). Three mice injected only with saline were used as background controls and sacrificed on day 2 (n = 3). Thigh muscles were excised and immediately frozen on dry ice in Epredia™ Neg-50™ frozen section medium (Fisher Scientific, 36-101-4314). Samples were stored at -80°C until sectioned using a cryostat microtome and counterstained with DAPI at The Centre for Phenogenomics (TCP), University of Toronto. Images were captured at the TCP facility (Fig. 4) and were subsequently assessed for qualitative expression of native eGFP. For each sample, four sectioned layers per sample were assessed, and the one with highest eGFP intensity was chosen per sample. A visual average was ascertained from these images for each time point and a suitable representative image was selected (Fig. 4B).

The highest eGFP intensity images were used to quantify eGFP mean intensity (Fig. 4C, D), utilizing ImageJ software to calculate mean intensity and total area for each sample. Weighted mean intensities were calculated for each vaccine group per time point, as the sum of the individual weighted mean eGFP intensities per sample. The individual weighted means were calculated using the following equation: (area sample / total area per time point) × mean intensity sample.

Immunization of mice

Groups of 15 week-old K18-hACE2 transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory, 034860) were immunized with 5 µg of LNP-encapsulated or 50 µg naked saDNA or saRNA formats expressing the B.1.617.2 (Delta) spike protein variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus or eGFP, or 50 µg naked saDNA or saRNA formats expressing the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) spike variant of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for the sequence). Optimal doses were determined in prior experiments utilizing other Spike constructs (Fig. 6B, C). Mice were immunized by intramuscular injection into the right caudal thigh muscle. Blood samples were taken from the left lateral saphenous vein before vaccination at day 1, and day 28 or day 42 post-initial vaccination. During the study, mice were monitored weekly (or more frequently if needed after injections or blood collection) for any behavioural changes or changes to body condition or weight. A humane endpoint was determined as a 20% overall weight loss or 10% weight loss from previous weight.

Cytokine bead-based array

Blood from mice was collected in 500 µL serum microvette tubes (Sarstedt, 20.1343.100) and centrifuged at 2000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Serum was transferred to a fresh 500 µL microtube. Both leg muscles were collected, cut into small pieces with scissors, then incubated in 1 mL of Pierce™ RIPA Lysis Buffer (Thermofisher, PI89900) for 20 min at 4°C. The sheared tissue was then sonicated with titanium beads for 20 min and centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was transferred to a fresh 5 mL macrotube. Serum and leg muscle supernatants were mixed with 100X Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermofisher, 78443) and 100X Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (Thermofisher, 15140122), and stored at –70°C prior to analysis.

The BD™ Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 CBA Kit (BD Biosciences, 560485) was used to determine cytokine concentrations from the serum and leg muscle supernatants. The protocol provided in the kit was followed. Samples were run on a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer. Data was analyzed using CBA Analysis Software (V1.1.15) and visualized using GraphPad Prism (V10.1.1).

ELISA Protocols

All ELISA assays followed the same general workflow with antigen-specific variations noted below. Coating antigens or antibodies were diluted in coating buffer (0.1 M Carbonate, pH 9.5) and coated onto 96-well plates (Corning, 3369) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed four times with washing buffer (0.1% Tween-20 in 1X PBS), then blocked with blocking buffer (2% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20 in 1X PBS) overnight at 4°C, followed by five washes with washing buffer. Serum samples from immunized mice were serially diluted in blocking buffer. One hundred microliters of each dilution were added to wells and plates were incubated away from light at 37°C for 1 h. After washing, the appropriate secondary detection antibody was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Following additional washes, 100 μL/well of TMB substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific, 34028) was added and incubated away from light at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL/well of stopping solution (0.16 N H2SO4) and absorbance was read at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader. Background absorbance from negative control wells (containing blocking buffer without serum) was subtracted from all sample measurements prior to data analysis and visualization67. Outliers were identified using Grubbs’ test (p < 0.05) and excluded from subsequent analysis.

SARS-CoV-2 Spike ELISA

For Delta strain analysis, SARS-CoV-2 Super Stable Trimer Spike protein (ACROBiosystems, SPN-C52H9-50UG) was used as the coating antigen. For Omicron strain analysis, SARS-CoV-2 RBD of spike protein (Proteogenix, Strain B.1.1.529, PX-COV-P074) was used. Serum samples were collected from mice immunized with either the B.1.617.2 (Delta) or B.1.1.529 (Omicron) spike protein variant. Standard curves were generated using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.0.1). For Delta, a B.1.617.2 SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody standard (ACROBiosystems, S1N-S58A1) was used. For Omicron, a positive control serum was generated in-house by vaccinating mice with Omicron spike protein in alum adjuvant, and quantified antibody from this serum was used to construct the standard curve. Unknown antibody values were interpolated from the respective standard curves and expressed in ng/mL. The secondary antibody used was Goat anti-mouse IgG, HRP-conjugated (Southern Biotech, 1030-05).

SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid ELISA

Nucleocapsid capture antibody (Acrobiosystem, NUN-CH14) was coated at 4.7 µg/mL. Serum samples from SARS-CoV-2 virally challenged mice were diluted 3-fold from 1:240 to 1:2160. A biotinylated anti-nucleocapsid secondary capture antibody (Acrobiosystem, AM223; 1 µg/mL dilution) was applied for 1 h at 37°C, followed by streptavidin-HRP secondary (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 016-030-084; 1:1000 dilution) for 1 h at 37°C. TMB substrate incubation time was 10 min at room temperature. A standard curve was generated from serial 2-fold dilutions of nucleocapsid protein (Acrobiosystems, NUN-C52Hw) ranging from 3.2 ng/mL to 0.05 ng/mL using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.0.2). Unknown sample concentrations were interpolated from the standard curve and expressed in ng/mL.

eGFP ELISA

eGFP protein (Thermofisher Scientific, A42613) was coated at 100 ng/mL. Serum samples from mice immunized with eGFP protein were diluted 3-fold from 1:80 to 1:2160. The Goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific, 31430; 1:4000 dilution) was applied for 1 h at 37°C. TMB substrate incubation time was 20 min at room temperature. An anti-GFP antibody standard (Thermofisher Scientific, GFP-101AP) was used to generate the standard curve using GraphPad Prism (Version 9.4.1). Unknown antibody values were interpolated from the standard curve and expressed in ng/mL.

ELISPOT assay protocols