Abstract

Forecasting volcanic eruptions remains a great civil defense challenge in many parts of the world. Although instrumental monitoring networks provide a variety of signals interpretable as eruption precursors, volcano observatories still lack a systemic warning tool that can issue unambiguous real-time alerts to stakeholders. Here, we propose such a tool called “Jerk” that permits real-time detection of subtle ground movements associated with magma injections. The Jerk signals consist of very low frequency transients in both horizontal ground motion and tilt which, we show, are generated by fracture openings prior to an eruption. These signals can be detected using one single broadband seismometer. Implementation of fully automated Jerk detection and analysis at Piton de la Fournaise (La Réunion island) has permitted real-time early warnings for 92% of 24 eruptions that occurred in 2014–2023, with alarm times ranging from a few minutes to 8.5 h before magma reaches the surface. The Jerk tool thus promises to be a successful early warning method for forecasting volcanic eruptions and provides a potential alternative for poorly monitored volcanoes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volcanic eruptions are generally preceded by changes in seismic activity, ground deformation, and gas flux/composition1,2,3,4,5. Yet, interpreting such changes in terms of eruption’s probability and characteristics (timing, duration, magnitude) remains a difficult challenge. Instrumental monitoring networks managed by volcano observatories provide multi-parameter signals that are targeted at eruption forecasting before the occurrence of surface phenomena with the aim of alerting decision-makers in due time. Avoiding premature and/or false alarms is very important to prevent unfortunate consequences such as heavy economic cost and societal disturbances including loss of credibility.

To date, our scientific understanding of magmatic-volcanic processes remains insufficient to implement a truly effective and systematic alert system that could operate independently of human judgment. Although monitoring systems have significantly improved in both quantity and quality over recent decades, quantitative models of volcanic processes remain limited. This deficiency prevents the implementation of fully deterministic, physics-based alert methods6. Since the discovery of the Failure Forecast Method after the 1980 Mount St. Helens disaster7, and given the inherent difficulties in implementing such an approach in real-time8, volcano observatories have increasingly adopted more pragmatic strategies. These favor probabilistic methods grounded on multidisciplinary observations9,10,11. Indeed, statistical implementation of eruption forecasting and alert systems is currently the only operational framework. It allows for the integration of diverse datasets and accounts for uncertainties in both models and interpretation. This, in turn, facilitates communication with decision-makers12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Here we describe a fundamentally different, fully deterministic approach that has been 92% successful in real-time over the last 10 years at Piton de la Fournaise, with 14% of false alarms. It is based on systematic observations of physical quantities derived from a single very broadband seismometer, which automatically triggers an alarm when overcrossing a quantitative threshold. The method enables the detection of shallow rock fracturing that could lead to an eruptive phenomenon: fissure opening with lava or gas emission.

Seismometers have been the first instruments used to monitor volcanoes in real time and are still of primary relevance for volcano monitoring1,4,21,22. New trends and perspectives are provided with innovative observation methods (e.g., Fiber optic sensing23). Volcanic processes generate many seismic signals and waveforms of varying amplitude and frequency content22,24,25. Volcano-tectonic (VT) earthquakes (5 to >40 Hz) are related to brittle fracturing of rocks under the stress generated by magma or fluid migration. These are the most common early precursors of increased volcanic activity26. Long-Period (LP) events (also called Low-Frequency events, 0.2 to 5 Hz) are often emergent signals that occur in swarms of repetitive waveforms27. They have been attributed to various processes such as fluid-filled resonance in fractures or cavities in volcanoes28,29,30,31 and hydrothermal systems32,33, oscillations due to fluid-driven flow34,35, stick-slip models36,37, degassing events38, and low stress drop or slow rupture39. Very-Long Period (VLP, below 0.2 Hz) events are interpreted as due to either heat, gas and magma inertial movement30,31,40,41,42, pit-crater and/or cavity collapse43, and interactions between magma and subterranean water in a volcano plumbing system21. As with all volcano seismic signals, LP and VLP events do not occur at all volcanoes, however, understanding their source mechanisms may provide key information on volcanic unrest and provide early warning of forthcoming eruptions for those where they do occur.

At Piton de la Fournaise (La Réunion island), VT, LP and VLP signals are observed prior to eruptions44,45,46. These signals are recorded either during the pressurization of the shallow magma reservoir located at about 2 km depth below the summit or during the dyke injection from this reservoir, which can be either vertical to the summit or lateral towards one of the volcano’s flanks - over a greater distance than in the first case. In addition to these well-known signals, unusual transients signals in the horizontal velocity component were noticed in recordings of the single very broadband RER station (360 s, see “Methods”), located 8 km away from the summit, prior to several eruptions and/or non-erupting magma intrusions47,48. These transients are not periodic and last for a couple of hours. The lack of signal on the vertical component suggested that these transient events might purely originate from ground tilt induced by pressure variations and/or magma transfer from the reservoir to the surface48,49. Careful analysis of 19 volcanic eruptions at Piton de la Fournaise between 2005 and 2010 showed that these transient events systematically happen as a step in ground motion acceleration and with a variable amplitude (a few µm s−2)48. However, the tilt amplitudes derived from the seismic signal are sometimes one or two orders of magnitude larger than those measured by tiltmeters at the same location50 or than the predicted elastic deformation at such a distance from the source. This discrepancy was previously suspected to reflect an inefficient ground coupling of the tiltmeters47,51.

Here, we demonstrate that these observed transient signals in seismic records at Piton de la Fournaise do not correspond to a simple ground tilt but are directly related to the dynamics of the source that generates more horizontal displacement than tilt at 8-km distance. Because they are related to the derivative of ground acceleration, we called them “Jerk”. The time lapse between these signals and the onset of an eruption varies from a few minutes to a few hours, depending on the depth of fracturing and the magma ascent velocity. Such a time lapse is sufficient to send an early warning alarm, so we implemented an automated real-time detection of these transient signals at the volcano observatory in 2014.

Results

Early-warning system based on the Jerk signal

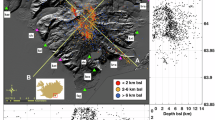

In April 2014, we developed and implemented at OVPF-IPGP (Observatoire Volcanologique du Piton de la Fournaise-Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris) a fully automated process based on the very broadband seismic station data to compute the Jerk signal and send an alarm when it reaches a threshold (Methods: “Computing the Jerk and sending an alarm”). On June 20, 2014, the first automatic alarm was sent at 20:33 UT (see Supplementary Fig. 1), 1 h before the appearance of volcanic tremor (at 21:35 UT) indicating that magma had reached the surface52. At the time of writing, the last recorded Jerk signal occurred on July 2, 2023, 40 min before the ensuing eruption. A clear transient signal of 1.5 nm.s-3 oriented to the summit was detected (Fig. 1) and automatically triggered the sending of an email warning scientists of an imminent eruption. A Jerk signal was systematically observed in real-time conditions for the next eruptions from 2015 to 2023 while the station was operational, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Jerk alarms anticipated the onset of eruptive tremor by up to 8 h (see values in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). On only two occasions (on June 11, 2019 and February 10, 2020; see Supplementary Fig. 1), the alarm arrived too late, i.e., almost synchronous with the eruption onset, and was thus considered a false negative. Note that we included in the list of eruptions the event of May 17, 2017 during which a new fissure opened with gas emissions associated with 4.5 h of seismic tremor. We also observed two Jerk alarms of magma injection but not followed by an eruption (on September 28, 2020 and October 10, 2021). After 10 years of operational experience, our Jerk tool performance is evaluated as 22 successful alarms before 24 eruptions, 2 false negatives (alarm too late), 2 false positives (intrusions without eruption), and 12 true negatives (seismic swarm not followed by an alarm, an eruption, or an intrusion), i.e., a true positive rate of 92% and a false positive rate of 14%. To evaluate the performance of our detection approach, we computed a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (Supplementary Fig. 8), which offers a standard and threshold-independent assessment of the trade-off between sensitivity and false alarm rate. The ROC curve confirms that the threshold of 0.1 nm.s-3 is the optimal threshold, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) is estimated at 0.85.

Example of the jerk signal from the two horizontal components recorded at the RER station before the last eruption at Piton de la Fournaise (July 2, 2023): time series and particle motion. The black arrow indicates the alarm time and the color scale refers to the particle motion time on the map. Contours of the associated lava flows are also shown.

Jerk amplitude is shown for time windows (−10, +4 h) around the eruption. The vertical gray lines indicate the start time of the seismic swarm. Gray boxes indicate the eruption. For all Jerk signals, the red solid outlines stand for the parts above the alarm level threshold (0.1 nm s−3) and inside the azimuth interval. On the right, the Jerk signals are plotted as oriented particle motions (north up) within target circles of 0.5 nm s−3 radius.

The horizontal pendulum seismometer

The Jerk signal usually appears during the most intense phase of the seismic swarm and edifice deformation. As detailed below, it can be considered as an unequivocal signal of magma migration out of the shallow reservoir that usually heralds a forthcoming eruption. Furthermore, the particle motion, oriented towards the volcano with a quasi-linear trajectory, provides a rough indication of the source location (Fig. 1). The Jerk signal is based on the horizontal pendulum principle. The horizontal acceleration53,54 is given by:

where ürad (t) is the horizontal acceleration in the radial translation direction, τrad(t) is the ground inclination or tilt due to rotation around the tangential horizontal axis (corresponding to the tilt radial component), g is the gravitational acceleration, Ωz(t) the rotation around the vertical Z axis, and d is the distance of the mass along the tangential axis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The rotational term Ωz(t) is weak and generally neglected54. The frequency response of the pendulum sensor is dominated by ground displacement at short periods (<100 s), but the tilt becomes a significant part of the signal at longer periods (>360 s)55 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Without any independent knowledge on the origin of ground motion, the recorded signals are the sum of different movements that cannot be differentiated, even though the continuous component can only be explained by ground tilt.

The Jerk seismic signal tracks fracture opening due to magma intrusion. One of the simplest ways to model the static response of a dyke injection is to consider the opening of a vertical dislocation in a homogeneous elastic half-space56. When computing the theoretical tilt and displacements as a function of distance due to a unitary opening of a vertical or horizontal dislocation located at shallow depth, we see that the amplitudes of tilt, vertical and horizontal displacements are inversely proportional to the fourth, third, and second power of the distance, respectively (Fig. 3). At a horizontal distance much greater than the depth of the source, only the horizontal displacement amplitude remains significant, while vertical displacement and tilt both become negligible or at least undetectable at the distal broadband seismic station (RER). Although the response of the sensor amplifies the tilt contribution to the recorded signal, the horizontal displacement contribution largely predominates due to the station distance, for the model chosen.

a Sketch of Piton de la Fournaise (PdF) topography profile, location of RER broadband station, and typical location of the source (either dyke or sill, gray area). b Comparison of theoretical displacements and tilt due to the opening of a dyke and a sill56 as a function of radial distance in logarithmic scale: radial tilt (blue), radial horizontal displacement (green) and vertical displacement (red). Tilt and displacements have different scales (ratio of 100). The two models – a vertical dyke perpendicular to the station (solid lines) and a horizontal sill (dotted lines) – use a dislocation of 100 × 100 m2 at 500 m depth with a 1 m opening in an elastic half-space. The gray vertical area depicts the typical distance interval (4–11 km) between the RER station and eruptive fissures at Piton de la Fournaise.

Interpretation of the Jerk signal

As seen in equation (1), the displacement term contributes to the recorded acceleration as a second derivative, while the tilt term is just a function of time with no derivative. Thus, the time function of dyke opening has a potentially dominant influence on the displacement term and on the final recorded acceleration. A simple dislocation model in elastic half-space produces different displacements and tilt patterns depending on the location, geometry (e.g., dyke or sill) and orientation of the magma intrusion (Fig. 3). Therefore, the Jerk signal can be used as a quantitative indicator of the dynamics of fracturing, because it will only appear in case of strong opening acceleration at the source (see “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 3).

The Jerk signal appears as a deviation of the horizontal component from background noise level (below 0.05 nm.s-3) during the main seismic swarm preceding an eruption. The Jerk signal ends and the horizontal component returns to background when the rate of earthquakes decreases and the dyke is propagating48. Due to the data processing (Methods: Computing the Jerk signal and sending an alarm), the responsiveness of the method can be up to 10–15 min. The time lapse is larger for small Jerk amplitudes. As an illustration, there were two eruptions for which the alarm failed – on June 11, 2019 and February 10, 2020 – since it coincided with the onset of the eruptive tremor (see Supplementary Table 1). Both eruptions occurred close to the summit crater so dyke propagation was short and rapid. A possible explanation is that the Piton de la Fournaise summit crater is located above a collapsed conduit, where materials are less coherent than in other parts of the volcanic edifice57.

Post-processing of past eruptions

In order to further validate the strength of our Jerk tool, we examined the seismic records of previous Piton de la Fournaise eruptions in a standard post-processing approach. This can be simulated in the same numerical conditions as in real time, i.e., using only causal signal processing in the WebObs data monitoring system installed at OVPF-IPGP58. A posteriori analysis of 24 eruptions, which occurred from 1998 to 2010, and for which RER station was operational, confirms a timely Jerk alarm would have been sent for 83% of the events (see Supplementary Table 3). Only three eruptions would not have triggered a Jerk alarm (September 1999, August 2006 and December 2008). The first false negative, before 2001, is coherent with a much lower signal to noise ratio due to lower quality electronics at that time. The 2006 and 2008 eruptions instead took place inside the Dolomieu summit crater and we believe that the magma reached the surface across an already strongly fractured medium, offering little resistance. As a matter of fact, the pre-eruptive seismic swarm was very weak in energy and short in duration, suggesting little fracturing prior to the eruption. Also, these two eruptions took place only a few days (16 and 17, respectively) after the end of a previous eruptive event, implying that the magma feeding system was still open at depth59.

Our overall analysis of 48 eruptions from 1998 to 2023 thus reveals 42 Jerk alarms actually followed by an eruption (Supplementary Tables 1, 3 and Figs. 4, 5). The time lapse between Jerk alarm and an eruption varied from a few minutes to 8.5 h, with an average of 2 h (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Over these 25 years, the success rate of the Jerk method in early eruption warning is somewhat lower than for the 2014–2023 real-time period owing to either alarm lacks (in 1999, 2006, and 2008) or late alarms in case of eruptions in the vicinity of the summit (in 2008, 2019, and 2020), both cases being false negatives (Supplementary Table 3).

Potential false positives may also occur, mainly in three specific cases. First, when a technical intervention is performed on the station, one observes high amplitude acceleration variations much above the observed maximum Jerk amplitude of 2.8 nm s−3 which can be quickly dismissed. Second, during major atmospheric perturbations such as cyclones or tropical storms the Jerk signal exhibits a higher noise, sometimes briefly reaching its alarm threshold. This happened, for example, on April 24, 2018 during the tropical storm Fakir which generated wind gusts reaching 185 km/h and rainfall in excess of 400 mm in 12-h at the station site. Under such conditions, however, the Jerk signal particle motion is no longer linear as during magma injection and generally not in the azimuth of the volcano (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, while clearly anticipated by a Jerk signal (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 7), some magma injections do not end up reaching the ground surface48. During the 1998–2023 period we thus identified 3 clear Jerk signals associated with magma injection but not followed by an eruption. While these three cases can be considered as false positives for eruption alarm, we do assert that the Jerk signal is an alert of magma injection stricto sensu. In fact, this signal coincides with seismic swarms and ground deformation (see Supplementary Fig. 7) and simultaneously tracks any magma injection fracturing the volcanic edifice. According to our 10 years of monitoring, when a Jerk alarm appears in real time there is a 100% likelihood of magma shallowing associated with injection/fracturing.

Almost all the eruptions/intrusions at Piton de la Fournaise in that period were systematically preceded by a Jerk signal. Despite a high eruption frequency, the magma always has to open its path to reach the surface. It is also remarkable that the Jerk signal remains quiet during an ongoing eruption. Although this has never yet been observed, the Jerk might also allow for the detection of another new magma injection during the course of an eruption, while the detection and location of small earthquakes become difficult due to the continuous eruptive tremor.

At OVPF-IPGP, the staff on duty is automatically alerted if the number of earthquakes per hour exceeds a threshold. Authorities are alerted of an imminent possible eruption as soon as the seismic swarm becomes intense and is accompanied by rapid ground deformation48,60. Monitoring the earthquake location and the signals recorded by tiltmeters and GNSS stations allows an initial diagnosis of the magma location at depth and of the volcano sector impacted by its propagation. The arrival of a Jerk signal strongly supports this first order analysis of an upcoming eruption. Thanks to this new tool, the observatory staff can confidently validate and communicate their assessment to the authorities who can raise the alert level and close the volcano access. Since 2012 the real-time Jerk alarm has become a very efficient early warning tool of eruptions at Piton de la Fournaise. The process is fully automated from sensor detection to alarm transmission, but has still to be controlled and validated by humans to exclude possible false alarms during station maintenance or weather disturbances such as cyclones. Moreover, with the delivery of a reliable eruption alert from only one broadband seismic station, the Jerk tool opens promising perspectives for eruption forecasting at remote or poorly monitored basaltic volcanoes experiencing recurrent dyking episodes. We are also convinced that any other violent dynamic process leading to fracturing of the medium has the theoretical potential to trigger a jerk-type signal that should be detectable at long distance. This could be tested, for example in the case of the recent eruptive sequence on Iceland’s Reykjanes Peninsula, where deformation signals have been systematically observed before the onset of each eruption61. Testing and deploying this new Jerk method on other volcanoes should thus contribute to improved eruption forecasting and, hence, to volcanic risk mitigation.

Methods

Broadband low noise seismic station

Piton de la Fournaise hosts a unique “very broadband” station RER (“Eastern River”) that belongs to the worldwide Geoscope network62. The station is located 21.17120 °S, 55.73986 °E, and 834 m elevation, at a distance of 8 km from the volcano summit in the N17 azimuth. The station is equipped with two Streckeisen horizontal STS-1H sensors and one vertical STS-1V sensor of 360 s period63. Its sensitivity meets very low-noise level standards64. Since 2010, the station has been upgraded with a feedback electronics Metrozet STS1-E300 and a 26-bit digitizer Quanterra Q330HR. The station is installed in a well-insulated shelter located in the middle of a 4 km long tunnel belonging to the French electricity producer EDF. The mean temperature variation is lower than 0.5°/year. The acceleration signals are dominated by Earth and ocean tides with peak-to-peak values of about 2.10−6 m s−2 on the horizontal components.

Seismic signal acquisition and sensitivity calibration

For the real-time processing, we used the mass position acceleration (POS) output signals from the two horizontal components LMN (northern) and LME (eastern) channels, at 1 Hz sampling rate. The frequency response of POS channels is flat. As the sensitivity factor is not provided by the manufacturer, we calculate it by using the linear correlation factor with the standard velocity channels LHE and LHN after instrumental response removal and conversion in acceleration using the SAC software65. This gives sensitivity factors of 4.02613.109 and 3.80261.109 count/(m s−2) for LMN and LME channels, respectively. Data flux is obtained using the FDSN web-service dataselect protocol request from SeisComP3 waveform database. For the eruptions before 2010, the POS signal was not available; we therefore used the velocity signals manually converted into acceleration, then we applied the same procedure as for real-time POS signals. Note that this processing can be properly done only in post-analysis conditions, since the instrumental response removal implies a preliminary detrend.

Earth and ocean tide removal

Very broadband sensors are sensitive to the subtle low ground movements such as Earth tides and ocean loading. The tides and transient signals have a similar amplitude, so the tidal contributions must be removed to avoid artifacts and false alarms. We calculate the theoretical tides by using the Gotic2 open-source program66 that uses the NA0.99 L model for long-period ocean tides67 and predicts the amplitude and phase of the tilt. Horizontal tidal waves are sensitive to environmental effects such as topography, geology68 or local cavity effects69 that remain mostly unknown. Thus, we adjusted the theoretical tides model for each component by inverting for two empirical additional parameters: the amplitude factor and time shift. Inversion is computed in real-time by minimizing the 12-h period residual using the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm70.

Computing the Jerk signal and sending an alarm

The Jerk signal is derived from the acceleration rate on each horizontal POS component, after the removal of the tide, on a 5-day real-time moving window. In order to be implemented in real-time, minimizing delay and window border effects, the process works in the time domain and uses causal filtering. To avoid spikes due to noisy data, the derivative is computed using a linear trend slope on a sliding window of 900 s length and 60 s resampling rate. The time window length has been minimized to get the best temporal responsiveness while keeping the signal to noise ratio at a reasonable level. The two cartesian components are expressed in polar coordinates, as amplitude and azimuth. The Jerk amplitude is a very stable signal with a background noise usually below 0.05 nm s−3. The amplitude is compared to two different thresholds of 0.1 nm s−3 for alarm level 1, and 0.2 nm s−3 for alarm level 2, based on the statistics of previous observed signals48. The level 1 is used to trigger a first alarm, which suggests a possible Jerk signal but might be reached during high noise level, while the level 2, achieved a few minutes later, validates the occurrence of a real Jerk signal. In addition to the threshold levels, we add a supplementary condition to initiate the alarm: the azimuth must be oriented in the volcano summit direction (N197) within a ±30° angle interval. Each transition from background to level 1, level 1 to level 2 or the reverse sends an automatic email alarm to a group of users, indicating the previous and present state, and a link to the data graph where additional information can be found. Measured temperature at the station is also plotted for checking possible thermal perturbations.

Integration into the observatory operational monitoring system

At the time of Jerk method implementation, OVPF-IPGP was already equipped with the WebObs system58, which has been designed to help scientists in the development and implementation of real-time data processing or modeling methods. Indeed, data import and associated parameters, graphic toolbox, automatic process scheduling, alarm notification and web access to the results are already handled by the system. Thanks to this environment, the Jerk method has been developed and implemented in only a few days and has become immediately operational as a new “proc” module with automatic detection and message alarm capabilities. The efficiency of the Jerk as an early warning system is currently limited by (1) the proper functioning of the seismic station, (2) the requirement of pre-eruptive fracturing (some eruptions might result from “silent” magma injection through a pre-fractured medium, such as for the December 2008 eruption), and (3) the oceanic noise. The positive feedback of the Jerk deployment at OVPF-IPGP suggests that this method deployed with several sensors could allow real time inversion of the various parameters of magma injection source, such as location, orientation and volume, which remain big uncertainties so far.

Synthetic Jerk signal

Assuming that the Jerk signal is generated by the opening of a lateral magmatic injection, we reconstruct the Jerk signal. In linear elastic models, the displacement, tilt and strain are all proportional with dislocation parameters (slip or opening). Here, we introduce the factor η as the ratio between horizontal displacement and tilt, in m rad−1, which is constant for a given source and a given observation point. For a 1-meter opening of a 100 × 100 m source located ~7 km from the observation point, the expected value of η is on the order of −5 × 10⁵ m rad−1 for a vertical dyke oriented N70°E, and approximately −2 × 10⁴ m rad−1 for a horizontal sill.

We compute the response of a horizontal pendulum to the opening of a dyke/sill using different source time functions, all simulating a “smooth” opening step x(t), but with different acceleration variations x’’’(t). The x’’’(t) synthetic signal is constructed from the concatenation of 4 portions of the sin(θ).sin(2θ) derivative function on the [0,π] interval delimited by A to E points: signal starts at θ = 0 (point A), reaches a positive maximum (point B), a negative minimum (point C), a secondary positive maximum (point D), then ends at θ = π (point E). Signal amplitudes at points B to C are adjusted by linear inversion in order to respect the boundary conditions x”(π) = 0 and x’(π) = 0. Resulting signal x(t) gives a smooth ramp in displacement, which is then normalized to the 0–1 m interval of opening. Arbitrary values of B–D positions result in various possible time functions, which combined with the factor η, are used to compute the POS signal as the sum of acceleration and tilt. This produces patterns similar to the observed Jerk signals.

We propose two examples of Jerk signals for an opening dyke and sill associated with distinct η values, and different time source functions (see Supplementary Fig. 3). These two sources result in transient positive first movement with undetectable tilt (similar to June 21, 2014 eruption), and negative first movement with significant tilt (similar to August 11, 2019 eruption).

Data availability

Continuous data has been acquired and validated by the Observatoire Volcanologique du Piton de la Fournaise from Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (https://doi.org/10.18715/REUNION.OVPF). All the processed data supporting this work are available at the IPGP Dataverse https://doi.org/10.18715/IPGP.2025.mebk5l9d. Raw data from the RER seismic station can be downloaded from http://geoscope.ipgp.fr. The POS channel data (LM*) after 2010, and lava flow contours are available upon request.

Code availability

The automatic tool software WebObs with Jerk module is available at https://ipgp.github.io/webobs. Earth and ocean tidal program Gotic2 is available at https://www.miz.nao.ac.jp/staffs/nao99/index_En.html.

References

Sparks, R. S. J., Biggs, J. & Neuberg, J. W. Monitoring volcanoes. Science 335, 1310–1311 (2012).

Surono et al. The 2010 explosive eruption of Java’s Merapi volcano—a ‘100-year’event. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 241, 121–135 (2012).

Patanè, D. et al. Insights into magma and fluid transfer at Mount Etna by a multiparametric approach: A model of the events leading to the 2011 eruptive cycle. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 3519–3539 (2013).

Pallister, J. & McNutt, S. R. Synthesis of volcano monitoring. In The encyclopedia of volcanoes 1151–1171 (Academic Press, 2015).

Sigmundsson, F. et al. Fracturing and tectonic stress drive ultrarapid magma flow into dikes. Science 383, 1228–1235 (2024).

Segall, P. Volcano deformation and eruption forecasting. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 380, 85–106 (2013).

Voight, B. A method for prediction of volcanic eruptions. Nature 332, 125–130 (1988).

Boué, A., Lesage, P., Cortés, G., Valette, B. & Reyes-Dávila, G. Real-time eruption forecasting using the material Failure Forecast Method with a Bayesian approach. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 2143–2161 (2015).

Newhall, C. & Hoblitt, R. Constructing event trees for volcanic crises. Bull. Volcanol. 64, 3–20 (2002).

Poland, M. P. & Anderson, K. R. Partly cloudy with a chance of lava flows: forecasting volcanic eruptions in the twenty-first century. J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2018JB016974 (2020).

Lowenstern, J. B. et al. Guidelines for volcano-observatory operations during crises: recommendations from the 2019 volcano observatory best practices meeting. J. Appl. Volcanol. 11, 3 (2022).

Aspinall, W. P., Woo, G., Voight, B. & Baxter, P. J. Evidence-based volcanology: application to eruption crises. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 128, 273–285 (2003).

Marzocchi, W., Sandri, L. & Selva, J. BET_EF: a probabilistic tool for long-and short-term eruption forecasting. Bull. Volcanol. 70, 623–632 (2008).

Marzocchi, W., Garcia-Aristizabal, A., Gasparini, P., Mastellone, M. L. & Di Ruocco, A. Basic principles of multi-risk assessment: a case study in Italy. Nat. Hazards 62, 551–573 (2012). no 2.

Aspinall, W. P. & Cooke, R. M. Quantifying scientific uncertainty from expert judgment elicitation. In Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Natural Hazards (eds Rougier, J., Sparks, S. &Hill, L. J.) 64–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139047562.005 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Thierry, P., Neri, M., Le Cozannet, G., Jousset, P. & Costa, A. Preface: approaches and methods to improve risk management in volcanic areas. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 197–201 (2015).

Dempsey, D. E., Cronin, S. J., Mei, S. & Kempa-Liehr, A. W. Automatic precursor recognition and real-time forecasting of sudden explosive volcanic eruptions at Whakaari, New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 11, 3562 (2020).

Ardid, A., Dempsey, D., Caudron, C. & Cronin, S. Seismic precursors to the Whakaari 2019 phreatic eruption are transferable to other eruptions and volcanoes. Nat. Commun. 13, 2002 (2022).

Ardid, A. et al. Ergodic seismic precursors and transfer learning for short term eruption forecasting at data scarce volcanoes. Nat. Commun. 16, 1758 (2025).

Rey-Devesa, P. et al. Volcanic early warning using Shannon entropy: multiple cases of study. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 128, e2023JB026684 (2023).

Chouet, B. & Matoza, R. S. A multi-decadal view of seismic methods for detecting precursors of magma movement and eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 252, 108–175 (2013).

Matoza, R. S. & Roman, D. C. One hundred years of advances in volcano seismology and acoustics. Bull. Volcanol. 84, 86 (2022).

Jousset, P. et al. Fiber optic sensing for volcano monitoring and imaging volcanic processes. In Modern volcano monitoring, (Advances in Volcanology) (eds Spika, Z. & Corentin, C.) (Springer, 2025).

McNutt, S. R. Seismic monitoring of volcanoes: a review of the state-of-the-art and case histories. In Monitoring and Mitigation of Volcano Hazards (eds Scarpa, R. & Tilling, R.I.) 99–146 (Springer, 1996).

McNutt, S. R. Volcanic seismology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 461–491 (2005).

Roman, D. C. & Cashman, K. V. The origin of volcano-tectonic earthquake swarms. Geology 34, 457–460 (2006).

Neuberg, J., Luckett, R., Baptie, B. & Olsen, K. Models and tremor and low-frequency earthquake swarms on Montserrat. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 101, 83–104 (2000).

Aki, K., Fehler, M. & Das, S. Source mechanism of volcanic tremor: fluid-driven crack models and their application to the 1963 Kilauea eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 3, 259–287 (1977).

Ferrazzini, V. & Aki, K. Slow waves trapped in a fluid-filled infinite crack: Implication for volcanic tremor. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 92, 9215–9223 (1987).

Ohminato, T., Chouet, B. A., Dawson, P. & Kedar, S. Waveform inversion of very long period impulsive signals associated with magmatic injection beneath Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 23839–23862 (1998).

Jousset, P. et al. Signs of magma ascent in LP and VLP seismic events and link to degassing: an example from the 2010 explosive eruption at Merapi volcano, Indonesia. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 261, 171–192 (2013).

Cusano, P., Petrosino, S. & Saccorotti, G. Hydrothermal origin for sustained long-period (LP) activity at Campi Flegrei Volcanic Complex, Italy. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 177, 1035–1044 (2008).

Syahbana, D. K. et al. Fluid dynamics inside a “wet” volcano inferred from the complex frequencies of long-period (LP) events: an example from Papandayan volcano, West Java, Indonesia. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 280, 76–89 (2014).

Julian, B. R. Volcanic tremor: nonlinear excitation by fluid flow. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 99, 11859–11877 (1994).

Rust, A. C., Balmforth, N. J. & Mandre, S. The feasibility of generating low-frequency volcano seismicity by flow through a deformable channel. Geol. Soc., Lond., Spec. Publ. 307, 45–56 (2008).

Harrington, R. M. & Brodsky, E. E. Volcanic hybrid earthquakes that are brittle-failure events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06308 (2007).

Pallister, J. S. et al. Faulting within the Mount St. Helens conduit and implications for volcanic earthquakes. Bulletin 125, 359–376 (2013).

Jousset, P. et al. Fibre optic distributed acoustic sensing of volcanic events. Nat. Commun. 13, 1753 (2022).

Bean, C. J. et al. Long-period seismicity in the shallow volcanic edifice formed from slow-rupture earthquakes. Nat. Geosci. 7, 71–75 (2014).

Legrand, D., Kaneshima, S. & Kawakatsu, H. Moment tensor analysis of near-field broadband waveforms observed at Aso Volcano, Japan. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 101, 155–169 (2000).

Waite, G. P., Chouet, B. A. & Dawson, P. B. Eruption dynamics at Mount St. Helens imaged from broadband seismic waveforms: Interaction of the shallow magmatic and hydrothermal systems. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 113, B02305 (2008).

Jolly, A. D., Neuberg, J., Jousset, P. & Sherburn, S. A new source process for evolving repetitious earthquakes at Ngauruhoe volcano, New Zealand. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 215, 26–39 (2012).

Jousset, P. & Rohmer, J. Evidence for remotely triggered microearthquakes during salt cavern collapse. Geophys. J. Int. 191, 207–223 (2012).

De Barros, L. et al. Eruptive fracture location forecasts from high-frequency events on Piton de la Fournaise Volcano. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4599–4603 (2013).

Duputel, Z. et al. Seismicity of La Réunion island. C. R. Geosci. 353, 237–255 (2021).

Duputel, Z. et al. Tracking changes in magma transport from very-long-period seismic signals at Piton de la Fournaise volcano. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 620, 118323 (2023).

Battaglia, J., Aki, K. & Montagner, J.-P. Tilt signals derived from a GEOSCOPE VBB station on the Piton de la Fournaise Volcano. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 605–608 (2000).

Roult, G. et al. A new comprehensive classification of the Piton de la Fournaise activity spanning the 1985–2010 period. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res 241–242, 78–104 (2012).

Aki, K. & Richards, P. G. Quantitative seismology: theory and methods. University Science Books, Mill Valley, California (1980).

Peltier, A., Staudacher, T. & Bachèlery, P. Early detection of large eruptions at Piton de la Fournaise. volcano J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 199, 96–104 (2011).

Battaglia, J. Quantification Sismique des Phénomènes Magmatiques Sur Le Piton De La Fournaise Entre 1991 et 2000. PhD thesis, Université Paris 7 (2000).

Beauducel, F., Peltier, A., Villié A. & Suryanto, W. Mechanical imaging of a volcano plumbing system from GNSS unsupervised modeling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089419 (2020).

Rodgers, P. W. The response of the horizontal pendulum seismometer to Rayleigh and Love waves, tilt, and free oscillations of the Earth. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 58, 1385–1406 (1968).

Pillet, R. & Virieux, J. The effects of seismic rotations on inertial sensors. Geophys. J. Int. 171, 1314–1323 (2007).

Wielandt, E. & Forbriger, T. Near-field seismic displacement and tilt associated with the explosive activity of Stromboli. Ann. Geophys. 42, 407–416 (1999).

Okada, Y. Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 75, 1135–1154 (1985).

Gailler, L. S., Martí, A. & Lénat, J. F. Complex structure of Piton de la Fournaise and its underlying lithosphere revealed by magnetotelluric 3D inversion. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 356, 200–210 (2018).

Beauducel, F. et al. WebObs: the missing link between research and real-time monitoring for volcano observatories. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 48 (2020).

OVPF-IPGP. December 2008 monthly bulletin. Institut de physique du globe de Paris, ISSN 2610-5101 (2009).

Peltier, A. et al. Volcano crisis management at Piton de la Fournaise (La Réunion) during the COVID-19 lockdown. Seismol. Res. Lett. 92, 38–52 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Minute-scale dynamics of recurrent dike intrusions in Iceland with fiber-optic geodesy. Science 388, 1189–1193 (2025).

Roult, G. et al. The GEOSCOPE Program: progress and challenges during the past 30 years. Seismol. Res. Lett. 81, 427–452 (2010).

Wielandt, E. & Streckeisen, G. The leaf spring seismometer: design and performance. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 72, 2349–2367 (1982).

Stutzmann, E., Roult, G. & Astiz, L. GEOSCOPE station noise levels. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 90, 690–701 (2000).

Goldstein, P., Dodge, D., Firpo, M. & Minner, L. SAC2000: signal processing and analysis tools for seismologists and engineers. In The IASPEI International Handbook of Earthquake and Engineering Seismology (eds Lee, W.H.K., Kanamori, H., Jennings, P.C. & Kisslinger, C.) (Academic Press, 2003).

Matsumoto, K., Sato, T., Takanezawa, T. & Ooe, M. GOTIC2: a program for computation of oceanic tidal loading effect. J. Geod. Soc. Jpn. 47, 243–248 (2001).

Takanezawa, T., Matsumoto, K., Ooe, M. & Naito, I. Effects of the long-period ocean tide on Earth rotation, gravity and crustal deformation predicted by global barotropic model. J. Geod. Soc. Jpn. 47, 545–550 (2001).

Emter, D. & Zürn, W. Observations of local elastic effects on earth tide tilts and strains. In Earth Tides, Benchmark Papers in Geology Series (ed. Harrison, J.C.) 309–327 (Van Nostrand-Reinhold, 1985).

Lambotte, S., Rivera, L. & Hinderer, J. Vertical and horizontal seismometric observations of tides. J. Geodyn. 41, 39–58 (2006).

Lagarias, J. C., Reeds, J. A., Wright, M. H. & Wright, P. E. Convergence properties of the Nelder-Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J. Optim. 9, 112–147 (1998).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Anne Mangeney for supporting the installation of the Jerk operational alarm system at OVPF-IPGP, Sébastien Bonaimé and Nicolas Leroy from Geoscope for technical assistance on the STS-1 sensor, the OVPF-IPGP staff for maintenance of the RER station, Denis Legrand and Erhard Wielandt for useful discussions about the POS signal, and Patrick Allard, Matilda Thomas, and Nathalie Dourneau for careful proofreading. We thank the Service National d’Observation en Volcanologie (SNOV-CNRS-INSU) for the use of the database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B. and G.R. equally contributed to the conception and data analysis of this work. F.B. proposed the “Jerk” interpretative model and wrote the software module for the WebObs system. G.R. and V.F. post-processed the RER data associated with all the eruptions before 2014. V.F., A.P., P.B., and N.V. contributed to the data acquisition. F.B., G.R., V.F., A.P., and P.J. contributed to the discussion of the model and the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wendy McCausland and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beauducel, F., Roult, G., Ferrazzini, V. et al. Jerk, a promising tool for early warning of volcanic eruptions. Nat Commun 16, 11418 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66256-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66256-z