Abstract

The rich physics of magic angle twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) results from the Coulomb interactions of electrons in flat bands of non-trivial topology. While the bands’ dispersion is well characterized, accessing their topology remains an experimental challenge. Recent measurements established the local density of states (LDOS) as a topological observable. Here, we use scanning tunnelling microscopy to investigate the LDOS of TBG near a defect. We observe characteristic patterns resulting from the Dirac cones having the same chirality within a moiré valley. At higher energies, we observe the Lifshitz transition associated with the Dirac cones mixing. Our measurements provide a full characterization of TBG’s band structure, confirming the main features of the continuum model including the renormalization of the Fermi velocity, the role of emergent symmetries and the topological obstruction of the wavefunctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

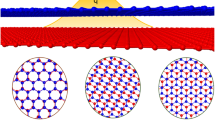

The flatbands of twisted graphene layers are a fantastic playground to study the effect of strong electronic correlations leading to an extraordinary diverse gallery of phases1, including correlated insulators2,3 superconductivity3,4,5 and strange metals6,7 depending on electron density, temperature, electric and magnetic fields. The flatness of the bands is not the only characteristics relevant to TBG physics. Their non-trivial topology is also crucial. This topology can be grasped in reciprocal space, where the Brillouin zone of one layer is twisted with respect to that of the other (Fig. 1a), defining a mini-Brillouin zone (mBz). Since graphene has two valleys of opposite chirality, TBG also has two mini-valleys. These are independent because the moiré potential varies over length scales too large to couple them8 despite they fold on top of each other in the mBz. Each mini-valley contains two Dirac cones originating from different layers and that hybridize to form the flatbands. Theory shows that the symmetry of the inter-layer hopping enforces these two Dirac cones to have the same chirality (Fig.1a)9. This prevents the low-energy description of TBG by a two-Wannier orbital model, which necessarily has Dirac cones of opposite chirality within a mini-valley. This is known as the topological obstruction10,11. This topology is responsible for the emergence of orbital magnet3,12 and Chern insulator states13,14,15,16 and could be involved in the superconducting state17,18. It is therefore highly desirable to determine experimentally the topology of the non-interacting bands in order to settle solid foundations for the description of the strongly correlated electron physics. We have recently used the quasiparticle interference (QPI) pattern of the LDOS near point defects to access Dirac electrons’ topology in graphene19,20,21,22. Here, following the suggestion of ref. 23, we show that this is also relevant to determine the relative chirality of the Dirac cones within a mini-valley of TBG.

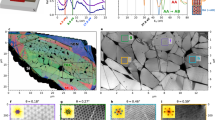

a The Brillouin zones of the top (blue hexagon) and bottom layer (yellow hexagon) are rotated by the twist angle θ. This defines the two moiré mini-valleys (purple and green hexagons), which are folded on top of each other in the mini-Brillouin zone (black hexagon). In each mini-valley, the Dirac cones coming from different layers have the same chirality, indicated by the rotating arrows. b STM topograph of 4.3° TBG (Vb = 200 mV, it = 100 pA). A point defect is visible near the center of the image. The scale bar is 3 nm. The colored stars correspond to the locations of the spectroscopic measurements presented in Fig. 2a. c Larger field of view of the local density of states image around the point defect at the center of the image. The image was measured at the same tunneling conditions. The scale bar is 10 nm. The dashed square corresponds to the area of the image of (b). d Possible inter-cone back-scattering within mini-valley + (top). Expected FFT of the top layer QPI signal for Dirac cones of the same (center) or opposite (bottom) chirality. e The position of the observed defect is identified by the red dot and labeled D. The position of other defects studied in Fig. 2 is marked by dots of other colors. f Modulus of the Fast Fourier Transform of the image in (c). The reciprocal lattice vectors G1 and G2 of the moiré are indicated, and the mBz is shown in orange. The scale bar is 1 nm−1.

Results

Observation of quasiparticle interferences near a defect in TBG

Figure 1b shows a scanning tunneling microscope topograph of twisted graphene layers prepared at the surface of SiC as described in ref. 24. The image reveals a typical moiré pattern resulting from the alternation of aligned (AA) and Bernal (AB) stacking regions. The twist angle, determined from the moiré period D = 3.25 nm, is θ ≃ 4.3°. A defect lies at the center of the image without much influence on the rest of the image. On the contrary, it strongly affects the energy-resolved LDOS image (see “Methods”). Figure 1c reveals periodic LDOS modulations centered on the defect, indicating that it acts as an elastic scatterer for electrons. The signal manifests in reciprocal space as circles centered on the corners KM and \(K{{\prime} }_{M}\) of the mBZ (Fig. 1f). This demonstrates inter-cone scattering within a mini-valley because the wave vector of the signal links states of neighboring Dirac cones. The circular shape follows from the enhanced weight of back-scattering in the scattering between circular constant energy contours25. This is illustrated in Fig. 1d, where colored vectors represent the scattering between initial state q and final state −q belonging to neighboring Dirac cones at low energies \(E=\hslash {v}_{F}^{*}q\) (ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, \({v}_{F}^{*}\) the Fermi velocity). Varying the orientation θq of the initial state q, the apices of these vectors trace out circles of radius 2∥q∥ around the scattering directions ΔK1, ΔK2, and ΔK3 (Fig. 1d). However, we observe only part of the expected 2q-circles, which therefore appear as 2q-arcs. We will now show that this is how the topological obstruction of wave functions manifests in this interferogram.

Determination of the relative chirality of Dirac cones

For twist angles below 10°, the electronic structure of TBG supports a four-band continuum description in which the electrons behave as massless relativistic fermions with identical chirality in a given mini-valley23. The moiré potential renormalises the Fermi velocity8,9,26. This non-interacting band structure can be probed at the experimental twist angle since the bands are still dispersing23. The wave functions characterize the charge distribution in the moiré unit cell and capture the four sublattice degrees of freedom. This allows for the description of scatterers localized at the scale of the moiré lattice, as in our experiment. We determine the LDOS modulations in the upper layer due to back-scattering between nearest-neighbor Dirac cones of the same chirality (Supplementary Section I). At large distances from the scatterer, they exhibit the universal oscillations

where the complex number \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}\) captures the elastic scattering in all orders and depends on the specific position r0, sublattice structure, symmetry, and strength of the defect. The algebraically decaying oscillations give rise to a 2q-circle centered on ΔKn in the FFT. The intensity along the 2q-circles is modulated by \({{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{n}({\theta }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}})=\xi+\chi \cos \left({\theta }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}}+{\phi }_{n}\right)\). This intensity factor results from the STM tip coupling to the incoming and outgoing wave functions in the upper layer (Supplementary Sections IC and ID). The band index satisfies χ = +1 (−1) in the conduction (valence) band, and the valley index ξ = ±1 denotes the chirality. The phase ϕn = (1−n)2π/3 depends on the orientation of the scattering wave vector ±ΔKn. Remarkably, the intensity factor \({{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{n}\) predicts zeros of intensity that are independent of the defect specificities. Along the 2q-circles, \({{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{n}\) vanishes once at the angle θq=π−ϕn [2π]. The QPI contribution from the mini-valley of opposite chirality exhibits the same behavior so that the signal of the two valleys simply adds up (Supplementary Section ID). The QPI expected within the four-band continuum description aligns perfectly with the experiments. We note that the 2q-arcs were not resolved in ref. 23, which considered the sum of the LDOSs of the two layers, while the STM tip only probes that of the top layer.

Alternatively, TBG can also be modeled by exponentially localized Wannier orbitals centered at the AB and BA regions27,28. The corresponding two-band continuum model produces similar band dispersion but with two Dirac cones of opposite chiralities within each mini-valley. A localized scatterer would then induce LDOS modulations with the same asymptotic behavior as in Eq.(1), but with a modified intensity factor \({{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{n}({\theta }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}})=1+\cos \left(2{\theta }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}}+{\phi }_{n}\right)\) (Supplementary Section IE). Consequently, the FFT of the QPI patterns would also consist of 2q-circles, but with two extinctions as was observed in graphene19,20,29. Therefore, the observation of 2q-arcs is compelling evidence that the Dirac cones within a mini-valley have the same chirality and cannot be derived from a two-band Wannier representation, thus confirming the topological obstruction of the wave functions.

We perform tight-binding calculations30,31 to investigate numerically this obstruction (see Supplementary Section II for details). We first confirm the relative chirality of Dirac cones by computing the Berry curvature Ω32. We find it to be singular, like in graphene, and it is the same for Dirac cones within a mini-valley consistent with the continuum model (Fig. 3c). We then investigate if our experiments can be reproduced by the numerical model. The position of the defect within the moiré unit cell is determined from Fig. 1e. We combined the spatial dependence of the LDOS and calculated QPI images to determine the best description of the scatterer. Figure 2a, b shows that the scatterer is faithfully modeled by a −1.5 eV deep Gaussian potential extended over σ = 1.5a0 in the two layers (see Supplementary Section III for a discussion of other defects). The size is compatible with experimental data (Fig. 1b) and justifies the assumptions of a point scatterer localized at the moiré scale. Furthermore, the calculations of Fig. 2d–f show that the 2q-arcs are robust against the position of the defect within the moiré unit cell and against the nature of the defect (Fig. 2g). This confirms independently the universal character of the intensity factor of the continuum model and strongly establishes our observation as an experimental proof of the topological obstruction. We note that the position of the defect influences the symmetry of the QPI signal, which is only perfectly C6 symmetric when the defect is centered in the AA regions.

a Experimental local density of states measured from the dI/dV spectroscopy with a set point of Vb = 800 mV and it = 800 pA (top). Corresponding theoretical LDOS (Bottom). The different spectra were measured at the locations indicated by a star of the same color in Fig. 1b. b–g STM images simulated from tight-binding calculations of the QPI signal in the surface layer near a defect (top) and its Fourier transform (bottom). The scale bar is 10 nm in the real space and 1 nm−1 in reciprocal space images. The labels indicate the type of defect, its position (see Fig. 1e), and the presence or absence of heterostrain. In (b–f), the defect is modeled by a Gaussian potential of depth 1.5 eV and width σ = 1.5a0 (a0 is graphene’s lattice constant). In (g), the defect is a non-reconstructed carbon vacancy located in the top layer. The intensity of Fourier transforms is normalized to ease comparison, but the signal from the vacancy is much smaller (see Fig. S3). All the results are displayed for an energy 175 meV below the van Hove singularity, as in the measurement of Fig. 1c.

Reconstruction of the electronic dispersion

The energy dependence of QPIs displayed in Fig. 3 can be exploited to explore the entire band structure with a momentum resolution of 0.01 Å−1 and energy resolution ~10 meV. At low energies, we use the radius of the arcs to retrieve the linear dispersion as was done in graphene20 (Fig. 3d). We find that the Fermi velocity is renormalised to 0.95 × 106 m/s. This is very close to the prediction of the tight-binding calculations from which we expect \({v}_{F}^{*}=0.85{v}_{mono}=0.91\times 1{0}^{6}\) m/s at this twist angle. Here, vmono is the Fermi velocity of monolayer graphene. At higher energies, the Dirac cones anti-cross at the M point of the mBz, forming a van Hove singularity (VHS) at which the Fermi surface undergoes a Lifshitz transition, switching to a star-shaped contour around the Γ point (Fig. 3b). This is reflected in Fig. 3, where a star-shaped signal arises in the FFT-QPI signal, which is well reproduced by the tight-binding calculations (Fig. S4). From these data and the corresponding back-scattering processes described by red and blue arrows in Fig. 3a–c, we can measure the dispersion above the VHS. We compare the experimental data to the results of the numerical model in Fig. 3d and find an overall very good agreement.

a Full energy dependence of the experimental QPI signal, both in real (top row) and reciprocal space (bottom row). The scale bars are 10 nm and 1 nm−1, respectively. In all images, we have kept a constant tunneling resistance of 2 GΩ. b Calculated constant energy contours of the pristine (without defect and strain) TBG lowest energy bands across the Lifshitz transition. The colored arrows indicate the possible back-scattering processes that can be measured from the experiments of (a). c Same data unfolded to the original graphene valleys to explicit the intra-mini-valley scattering process represented by colored arrows. The twist angle has been increased for presentation purposes. d Energy dispersion of TBG reconstructed from the data of (a) (solid squares) and the corresponding images calculated by tight-binding (diamonds). The error bars correspond to the width of 2q-arcs. See Fig. S4 for these images. The colors of the square and diamond correspond to those of the scattering process depicted in (c). This scatter plot is overlaid on the electronic dispersion calculated by tight-binding with (yellow) or without (black) heterostrain. The colored arrows correspond to the scattering processes introduced in (b).

Discussion

In order to provide the most accurate description of our experiments, we will now discuss the effect of heterostrain, which is ubiquitous in TBG31,33. Our analysis, presented in the Supplementary Section IV, reveals a small uniaxial heterostrain of 0.2% and a biaxial heterostrain of 0.4%. Tight-binding calculations including the full relative arrangement show that this induces a slight distortion of the low-energy bands (Fig. 3d). However, this does not alter the extinctions in the QPI rings (Fig. 2b, c, showing images without and with heterostrain), providing a hint that the topology of TBG is robust against heterostrain as recently proposed34. It will be interesting to verify that this is still the case at a lower twist angle, where strain has an increasing effect33,35.

More importantly, our analysis of the relative arrangement of the layers demonstrates that the moiré lattice is not commensurate with the graphene lattice (Fig. S7). This means that we are certain that translation symmetry is only approximate at the moiré scale. Yet, the continuum model describes our experiments well despite it accounts only for emerging symmetries at the moiré scale and not the exact symmetries at the atomic scale8,10,36.

Finally, we have measured the QPI signal of other point defects in another TBG sample with a similar twist (Supplementary Section V). Surprisingly, we did not measure any signal at the scale of the moiré despite the presence of sizable intervalley scattering at the atomic scale in the top graphene layer. This has to be linked to the internal details of the defects (term \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}\) in Eq. 1). Indeed, tight-binding calculations of Fig. 2b–f reveal that while the 2q-arcs are universal, there can be order of magnitude variations in the amplitude of the signal depending on the details. While the exact nature of the defect we have observed is unknown, it has been crucial to make the QPIs measurable in our experiment.

In conclusion, our work experimentally settles the band structure of twisted graphene layers of moderately low twist angle, where interactions are negligible. We anticipate that QPIs could also be useful to investigate the magic angle regime where strong correlations play an important role.

Methods

STM measurements

The measurements were acquired in a custom-built UHV-STM in a cryogenic environment at 8.4 K and 10−10 mbar. Thermal broadening results in a 2.6 meV broadening that does not affect QPI interpretation. The STM tip is a wire-cut Pt/Ir; the apex is cleaned with field emission and prepared on Ag(111). Density of states maps are taken using Lock-In phase sensitive detection with a 10 mV AC voltage modulation.

Sample fabrication

Multilayer graphene was grown on the C-face of 6H-SiC, a custom-built RF-furnace24. During the first step of the process, SiC was hydrogen etched by exposing it to a 98%Ar 2%H2 dynamic flow, at a temperature of 1600 °C for 30 mn (ramps are 1 h long). Then the graphene was grown on the etched C-face SiC at 1600 °C for 30 mn, with slow ramp rates (3 and 5 h for the up and down ramps, respectively). The sample was then further annealed in the UHV-STM chamber for degassing.

Data availability

The STM data measured in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17360113.

References

Bernevig, B. A. & Efetov, D. K. Twisted bilayer graphene’s gallery of phases. Phys. Today 77, 38–44 (2024).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80 (2019).

Lu, X., Stepanov, P. & Yang, W. et al. Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574, 653 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Magic-angle graphene superlattices: a new platform for unconventional superconductivity. Nature 55, 43–50 (2019).

Stepanov, P. et al. Decoupling superconductivity and correlated insulators in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 375 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Strange metal in magic-angle graphene with near planckian dissipation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 076801 (2020).

Lu, X., Das, I. & Di Battista, G. et al. Quantum critical behaviour in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 633 (2022).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12233 12237 (2011).

de Gail, R., Goerbig, M. O., Guinea, F., Montambaux, G. & Castro Neto, A. H. Topologically protected zero modes in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 045436 (2011).

Zou, L., Po, H. C., Vishwanath, A. & Senthil, T. Band structure of twisted bilayer graphene: Emergent symmetries, commensurate approximants, and wannier obstructions. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085435 (2018).

Song, Z. et al. All magic angles in twisted bilayer graphene are topological. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 036401 (2019).

Serlin, M. et al. Intrinsic quantized anomalous Hall effect in a moiré heterostructure. Science 367, 900–903 (2020).

Nuckolls, K. P. et al. Strongly correlated Chern insulators in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 588, 610 (2020).

Wu, S., Zhang, Z., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Andrei, E. Y. Chern insulators, van Hove singularities and topological flat bands in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 20, 488 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Fractional Chern insulators in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 600, 439 (2021).

Yu, J., Foutty, B. A. & Han, Z. et al. Correlated Hofstadter spectrum and flavour phase diagram in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 835 (2022).

Tian, H., Gao, X. & Zhang, Y. et al. Evidence for Dirac flat band superconductivity enabled by quantum geometry. Nature 614, 440–444 (2023).

Tanaka, M., Wang, J. & Dinh, T. et al. Superfluid stiffness of magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 638, 99–105 (2025).

Brihuega, I. et al. Quasiparticle chirality in epitaxial graphene probed at the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 206802 (2008).

Mallet, P. et al. Role of pseudospin in quasiparticle interferences in epitaxial graphene probed by high-resolution scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045444 (2012).

Dutreix, C. & Katsnelson, M. I. Friedel oscillations at the surfaces of rhombohedral n-layer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 93, 035413 (2016).

Dutreix, C. et al. Measuring the Berry phase of graphene from wavefront dislocations in Friedel oscillations. Nature 574, 219–222 (2019).

Phong, Vo. T. & Mele, E. J. Obstruction and interference in low-energy models for twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 176404 (2020).

Kumar, B. et al. Growth protocols and characterization of epitaxial graphene on SiC elaborated in a graphite enclosure. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 75, 7–14 (2016).

Simon, L., Vonau, F. & Aubel, D. A phenomenological approach of joint density of states for the determination of band structure in the case of a semi-metal studied by FT-STS. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 19, 355009 (2007).

Lopes dos Santos, J. M. B., Peres, N. M. R. & Castro Neto, A. H. Graphene bilayer with a twist: electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 256802 (2007).

Kang, J. & Vafek, O. Symmetry, maximally localized wannier states, and a low-energy model for twisted bilayer graphene narrow bands. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031088 (2018).

Koshino, M. et al. Maximally localized Wannier orbitals and the extended Hubbard model for twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031087 (2018).

Dutreix, C. et al. Measuring graphene’s Berry phase at b = 0 T. Comptes Rendus Phys. 22, 133–143 (2021).

Trambly de Laissardière, G., Mayou, D. & Magaud, L. Localization of Dirac electrons in rotated graphene bilayers. Nano Lett. 10, 804–808 (2010).

Huder, L. et al. Electronic spectrum of twisted graphene layers under heterostrain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 156405 (2018).

Fukui, T., Hatsugai, Y. & Suzuki, H. Chern numbers in discretized Brillouin zone: efficient method of computing (spin) Hall conductances. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 74, 1674–1677 (2005).

Mesple, F. et al. Heterostrain determines flat bands in magic-angle twisted graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 126405 (2021).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J. et al. Topological heavy fermion model as an efficient representation of atomistic strain and relaxation in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 112, 125128 (2025).

Bi, Z., Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Designing flat bands by strain. Phys. Rev. B 100, 035448 (2019).

Lopes dos Santos, J. M. B., Peres, N. M. R. & Castro Neto, A. H. Continuum model of the twisted graphene bilayer. Phys. Rev. B 86, 155449 (2012).

Acknowledgements

V.T.R. and G.T.d.L. acknowledge the support from the ANR Flatmoi project (ANR-21-CE30-0029). TB calculations have been performed at the Centre de Calcul (CDC), CY Cergy Paris Université, and at TGCC-GENCI (Project AD010910784). C.D. acknowledges support from the project TopoMat (ANR-23-CE30-0029) funded by the French National Research Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M., P.M., J.-Y.V., and V.T.R. conceived the experiments. F.M., G.L., P.M., and J.-Y.V. performed the experiments. F.M., V.T.R., P.M., and J.-Y.V. analyzed experimental data. G.T.d.L. performed tight-binding calculations, and C.D. conducted T-matrix analysis of conductance maps. V.T.R. wrote the manuscript with the input of all authors and coordinated the collaboration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesple, F., Mallet, P., Trambly de Laissardière, G. et al. Experimental evidence of the topological obstruction in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat Commun 16, 11478 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66257-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66257-y