Abstract

Structure fires in the wildland–urban interface (WUI) are becoming more frequent and destructive, yet their emissions of air pollutants remain poorly quantified and are not included in national inventories. Here we present a conterminous-scale inventory of WUI-related structure fire emissions in the United States from 2000 to 2020. A small number of highly destructive events dominate structure fire emissions—the 20 most destructive fires account for 68% of total carbon monoxide emissions. Structure fire emissions are more spatially concentrated than vegetation fire emissions, and in several states emissions of specific hazardous air pollutants such as hydrochloric acid exceed those from all anthropogenic sources combined. We show that structure burning in wildfires is strongly influenced by fire-conducive weather, and destructive structure fires are more likely to occur in forested and urbanized landscapes. These results reveal structure fires as a major source of toxic air pollution, with important implications for air quality, public health, and fire management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wildland-urban interface (WUI) is the geographic area where wildland vegetation and land developed by human activity come into contact or intermingle1. Fires in WUI have long posed a critical and growing challenge, particularly across the United States (U.S.), as they often involve not only natural vegetation but also the combustion of buildings, infrastructure, vehicles, and other urban materials. This mix of structural and vegetative fuels can produce smoke with distinct chemical composition and toxicity2. Since 2005, WUI fires have destroyed more than 100,000 homes across the U.S3. Recent studies have shown that WUI area, WUI housing, and the fractions of fire counts and burned area within WUI regions are rising4, thus highlighting the increasing prevalence of WUI fires. Moreover, wildfires are growing 250% faster across the West since 20055, challenging fire suppression efforts that can reduce home ignitions. In recent years, several destructive (defined by the number of houses destroyed in fires) WUI fires have highlighted the increasing significance of these WUI fires, including the 2018 Camp Fire in Butte County, California, which burned more than 15,000 structures6; the 2021 Marshall Fire in Boulder County, Colorado, which destroyed more than 1000 structures7; the 2023 Lahaina Fire in Maui, Hawaii, which destroyed more than 2000 structures8; and most recently, the 2025 fires near Los Angeles, California, which are estimated to have destroyed at least 16,000 structures9.

WUI fires differ from wildland fires in several important ways. First, WUI fires occur where human development and wildland areas overlap, and they are often initiated when vegetation fires spread into communities and ignite structures—typically through embers—rather than originating in urban settings. Because of this overlap, human-caused ignitions are more dominant, leading to a higher likelihood and frequency of ignitions compared to those in remote wildlands10,11. Additionally, because WUI fires often occur close to population centers, their emissions can more directly degrade local air quality, resulting in extensive public health impacts10,12,13,14. Fire behavior, environmental drivers, suppression strategies, and management approaches also differ significantly between WUI and wildland fires7,15,16,17,18,19,20. Perhaps most importantly for this study, WUI fires often involve the burning of structures, a key distinction from purely wildland vegetation fires12,14,21.

From the perspectives of atmospheric chemistry, air quality, and public health, structure burning is particularly important to quantify due to the toxic emissions produced from building materials22,23. Compared with vegetation fires, structure fires emit a broader and more complex mix of hazardous pollutants due to the combustion of materials, such as plastics, treated wood, wiring, and household contents. This mixture includes not only criteria pollutants, such as carbon monoxide (CO) and particulate matter (PM), but also volatile organic compounds (VOCs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), acid gases (e.g., hydrochloric acid, HCl), and toxic metals (e.g., lead, Pb)2,14. These pollutants not only degrade outdoor air quality but also infiltrate homes that are adjacent to the burn area, posing health risks to residents in nearby WUI neighborhoods13,23. In this study, we study emissions from burned structures in wildfires and use HCl and Pb as illustrative hazardous pollutants.

Quantifying emissions from burned structures in wildfires is essential for understanding their impacts on atmospheric composition and chemistry, air quality and human health. However, unlike vegetation fire emissions, which have been quantified through extensive modeling and field measurements24,25,26,27, large-scale information on structure fire emissions remains scarce. Quantifying fire emissions requires three key pieces of information: fire occurrence and extent, the mass of fuel burned (can be estimated from fuel load and percent combustion), and emission factors (EFs) for each chemical species (i.e., mass of pollutant emitted per mass of fuel burned)28. Obtaining these data at large scales has historically been challenging and subject to significant uncertainties, even for vegetation fires29. For structure fire emissions, it has only recently become feasible, thanks to the availability of critical datasets including the all-hazards incident records mined from the U.S. National Incident Management System (NIMS)3, structure fuel load data30,31, and recently developed EFs for structure burning14.

Despite remaining uncertainties, we present here a comprehensive inventory of structure burning emissions in wildfires across the conterminous U.S. for the period 2000–2020—named as the Fire Inventory from NCAR—Wildland Urban Interface (FINN-WUI) version32. We further analyze the spatial characteristics, temporal trends, and drivers of structure burning emissions, providing a foundation for future work on atmospheric and health impacts of WUI fires. Note that we do not use formally defined WUI layers (for example, ref. 33) in this analysis. Instead, we characterize events as WUI-related or structure fire emissions based on the co-occurrence of structure loss and wildfire activity. Our estimates focus on structure-impacted wildfires rather than relying on spatially delineated WUI boundaries.

Results

Distributions of emissions from structure burning differ from vegetation burning emissions

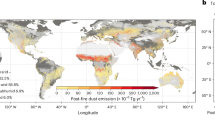

We compare structure burning emissions across the conterminous U.S. from 2000 to 2020 with emissions from vegetation burning. Here, we use CO as an illustration. CO is a major atmospheric criteria pollutant and a widely used tracer for fire emissions, with its EFs being relatively similar between structure and vegetation fires—approximately 70 g/kg of fuel for structure burning and 100 g/kg for biomass burning. The spatial pattern of CO emissions from structure and vegetation fires across the conterminous U.S. reveals both similarities and key distinctions (Fig. 1). From 2000 to 2020, structure fires occur nationwide, with the largest accumulation of burned structural fuel in California and the Southeast (Fig. 1A). In 2020, several structure fire events produce CO emissions exceeding 10⁹ grams (g), with notable hotspots in California (Fig. 1B). While structure fire emissions are episodic and locally intense, their spatial footprint in 2020 closely aligns with vegetation fire emissions within the WUI regions (Fig. 1C) and across all landscapes (Fig. 1D). This resemblance suggests that both structure and vegetation fire emissions may be driven by common factors, such as regional fire weather and broader climatic conditions, which are explored in a later section. The co-occurrence of emission hotspots in areas such as California and the Southeast suggests that fire-conducive environments can simultaneously increase risks across various fuel types and land-use categories. Despite these similar regional patterns, structure fires tend to occur nearer to population centers, often amplifying their impact on air quality and public health10.

A Structure fire distribution from 2000 to 2020 across the conterminous U.S., with circle size representing the total amount of fuel burned for each fire. For visibility, values smaller than 500 t were plotted using the minimum circle size corresponding to 500 t. B Total carbon monoxide (CO) emissions (in grams, g) from structure fires in 2020. C Gridded to 0.25 × 0.25 degrees, CO emissions (g/m²) in 2020 from vegetation fires occurring in the wildland–urban interface (WUI) area derived from a previous study71. D Gridded total vegetation burning CO emissions (g/m²) in 2020, including both WUI and non-WUI areas. CO emission data in (C) and (D) are from the Fire Inventory from NCAR version 2.5 (FINNv2.5).

Despite their overall similar regional patterns, CO emissions from structure fires exhibit stronger spatial and event-level concentration across the conterminous U.S., in contrast to the broader distribution of emissions from vegetation fires. As shown in Fig. 2A, average annual CO emissions from states that experienced vegetation burning (2002–2020) are highest in California, Oregon, and several southeastern states, but are distributed across many parts of the country. These emissions include prescribed fire emissions, which are distributed across the southeast. In contrast, structure fire CO emissions (Fig. 2B) are more geographically concentrated, with California alone contributing nearly 5 × 10⁹ g/year ( ~ 69%). Other high-emission states include Tennessee, Texas, and Oregon, where large WUI fires have occurred. To complement our state-level emissions analysis, we normalize structure fire CO emissions by total burned area in each state (Fig. 2C). This reveals where structure burning emissions are disproportionately high relative to overall fire activity. California and Tennessee stand out, highlighting the intensity of structural loss in these states. Other states, such as Colorado, New York, and Michigan, also exhibit elevated structure emission density relative to their total burned area. These results suggest that structure fire emissions are not solely a function of fire size, but also depend on land use, structure density, and fire-urban interactions.

A Average CO emissions (g/year) from vegetation burning (2002–2020) by state. B Average CO emissions (g/year) from structure burning (2000–2020) by state. C Ratio of CO emissions from structure burning in wildfires to total burned area of wildfires by state (2002–2020 average). State order follows (B). D Top 20 most destructive fires in terms of structure fuel loss from 2000 to 2020 across the conterminous U.S., with structure fire CO emissions (bars, left y-axis) and number of structures destroyed (line, right y-axis). Each x-axis label shows the state, year-month, and fire name. Bar colors indicate the U.S. state: CA (yellow), TN (dark blue), TX (orange), CO (green), OR (pink), NM (sky blue).

Figure 2D illustrates the dominant impact of a few extreme events. The 20 wildfires with the highest estimated structure fuel burned between 2000 and 2020 account for a disproportionate share of national burned structure emissions in wildfires. The 2018 Camp Fire in California stands out, with CO emissions from burned structure exceeding 5 × 10⁵ g and nearly 15,000 structures destroyed. These findings demonstrate how a small number of high-impact fires can significantly contribute to national emission totals, reflecting the episodic yet intense nature of structure fire pollution. Emissions of structure burning in wildfires are largely driven by extreme events, which appear to have become more frequent in recent years. Of the top 20 events in Fig. 2C, only 5 occurred during 2000–2010, while 15 occurred between 2010 and 2020. Notably, 12 of them took place in the most recent five years (2016–2020), suggesting a significant upward trend in the frequency of large, high-emission structure burning events (bootstrap test, p- value (p) <0.01). The implications of this trend and the associated year-to-year variability will be analyzed in the next section.

Interannual and seasonal variability of structure burning emissions

Structure fire emissions (blue line in Fig. 3A) exhibit substantial year-to-year variability, with prominent peaks in 2003, 2007, 2016, 2020, and especially 2018—the year of the Camp Fire, which result in nearly 6 × 10¹⁰ g of CO emissions, accounting for 26% of the total emissions from structure burning in wildfires during the 2000–2020 period. The early 2000s are marked by relatively low fire activity and smaller events, while the post-2010 period has a clear increase in both the frequency and scale of wildfires that involve structure burning (Figs. S1 and S2). Vegetation fire emissions in the conterminous U.S. (orange line) are generally an order of magnitude higher and have smaller interannual variability (coefficient of variation for the time series of vegetation fire CO emissions and structure burning CO emissions in wildfires are 0.3 and 1.5, respectively), reflecting the broader spatial extent and frequency of wildland fires. These year-by-year variations show the episodic nature of structure fire pollution and the growing prevalence of large, high-emission events in recent years. Despite the difference in absolute magnitude, the structure and vegetation fire emissions share similar interannual behavior in earlier years. Between 2002 and 2015, structure and vegetation fire emissions were moderately correlated (r = 0.51), suggesting common climatic or environmental drivers. From 2016 to 2020, this correlation weakens (r = 0.33), although the shorter time window limits the statistical confidence of this comparison. The reduced correspondence in recent years may indicate the emergence of factors influencing structure fire emissions that are less aligned with general vegetation fire variation. Long-term averages further emphasize a shifting structure fire regime. Between 2011 and 2020, average annual CO emissions from structure burning are approximately three times greater than those from 2000 to 2010, while emissions from vegetation burning increase by only 14% over the same periods. This disproportionate growth points to an increasing frequency and severity of high-impact structure fires. Notably, the top 20 most destructive events (‘destructive’ refers specifically to destruction of structures in this study) account for 68% of total structure fire CO emissions over the full period, highlighting the extent to which annual totals are shaped by a small number of extreme events. However, these events are becoming less rare. Recent fires—including the 2021 Marshall Fire (Colorado), the 2023 Lahaina Fire (Maui, Hawaii), and the 2025 fires near Los Angeles (California) —signal an ongoing trend toward more frequent, high-emission structure fires.

A Annual CO emissions (in grams, g) from structure burning in wildfires (blue, left axis) and vegetation fires (orange, right axis) across the conterminous U.S. from 2000 to 2020. B Monthly distribution of fire counts expressed as a percentage of total annual fire counts. Lines represent all fire incidents from the all-hazards dataset mined from the US National Incident Management System (ICS-209-PLUS) (green), those involving structure burning (yellow), and the 20 most destructive structure fires (pink).

The monthly distribution of fire incidents highlights important differences between total fire activity, structure-involved fires, and the most destructive events (Fig. 3B). Both total fire incidents and those involving structure burning exhibit similar seasonal patterns, with peak activity in July and August. In contrast, the 20 most destructive structure fires are heavily concentrated in the late summer and early autumn (August to October), a period when overall fire counts begin to decline, but aligns with high wind conditions and often human-related ignitions, particularly in California34. This seasonal asymmetry suggests that the most damaging structure fires tend to occur under different conditions than typical wildland fires. The seasonality of the 20 most destructive structure fires is largely driven by wildfires in the western U.S., with 18 of the 20 events occurring in the West and only 2 in the East. Regional differences in seasonal patterns are further illustrated in Fig. S3. The seasonality of the most destructive structure fires also shifted from a peak in October (2000–2010) to August–September (2011–2020), indicating a trend toward earlier occurrence of most destructive events (Fig. S4). This seasonal asymmetry is consistent with the possibility that the largest structure-loss incidents occur later in the fire season—when fuels are drier and episodic offshore wind events (e.g., Santa Ana/Diablo) could promote rapid WUI fire spread—conditions that may differ from those governing typical summer wildland-fire activity35,36.

Structure burning emissions of toxics can exceed anthropogenic emissions

Structure fires contribute substantially to atmospheric pollutant burdens across the conterminous U.S. Averaged over 2000–2020, structure burning emits a broad suite of pollutants (Fig. 4A), including CO (up to 8 × 10⁹ g/year), total hydrocarbons, particulate elemental carbon, and a diverse range of hazardous air pollutants (e.g., PAHs, VOCs, and trace metals). These emissions, which are largely unaccounted for in current national inventories, can rival or exceed known anthropogenic sources in specific states. To illustrate this, we compare structure burning emissions of HCl and lead (Pb) in 2016–2020 with anthropogenic estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 2020 National Emissions Inventory (NEI). HCl and lead (Pb) are critical pollutants due to their significant health risks. HCl is classified as a respiratory irritant with both acute and chronic health risks upon inhalation by NIOSH37,38. Pb exposure can affect almost every organ and system in the body, especially for children38,39,40. In California and Tennessee, average annual HCl emissions from structure burning in wildfires during 2016–2020 exceed those from anthropogenic sources (Fig. 4B). Moreover, in California, Tennessee, Colorado, and Oregon, structure fire HCl emissions surpass anthropogenic sources in at least one year within that period (Table S1). Notably, in 2018, HCl emissions from structure burning in California were approximately 23 times higher than anthropogenic emissions. Pb emissions from structure burning are also substantial in several states (Fig. 4C). In Tennessee, average annual Pb emissions from structure burning in wildfires during 2016–2020 are roughly three times greater than those from anthropogenic sources. In 2016, Pb emissions from structure burning in Tennessee reached nearly 14 times the anthropogenic total (Table S2). In California, 2018 structure fire Pb emissions are equivalent to 54% of the state’s anthropogenic Pb emissions. In Washington in 2020, Pb emissions from structure burning are equivalent to 28% of anthropogenic emissions, while in Oregon in 2020, they represent 21% (Fig. 4C). More recent wind-driven WUI fire events, such as the 2021 Marshall fire in Colorado, 2023 Lahaina fire on Maui, Hawaii, and the 2025 Los Angeles fire, may have produced even greater emissions, highlighting the growing importance of structure fires as a pollution source, particularly for Pb and HCl.

A Averaged annual structure burning emissions from 2000–2020 across a range of pollutants, displayed with separate y-axes to accommodate wide dynamic ranges. Comparison of 2016–2020 B hydrochloric acid (HCl) emissions and C lead (Pb) emissions from structure fires (green) versus anthropogenic sources reported in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 2020 National Emissions Inventory (NEI) (pink), by state. Structure fire emissions represent annual averages over 2016–2020, with vertical whiskers showing the minimum and maximum across the five years. Abbreviations: THC = total hydrocarbons, PM = particulate matter, Cl = chlorine, H₂S = hydrogen sulfide, HCN = hydrogen cyanide, NH₃ = ammonia, NOₓ = nitrogen oxides, HBr = hydrogen bromide, SO₂ = sulfur dioxide, Sb = antimony, FCDF = furan chlorinated dibenzo furans, and PCDD = polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins.

Drivers of structure-burning emissions

We analyze the land cover type for wildfires involving structure burning (Fig. 5). Fires are first grouped into five categories based on the number of structures impacted. The number of structures impacted is defined as the number of structures destroyed plus 30% of the number of structures damaged, to approximate the partial contribution of damaged structures to overall fuel loss (uncertainties discussed in the Methods section). For each fire in each category, we then overlay the fire perimeter with the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) land-cover type data (MCD12Q1, 500 m resolution) and count the pixels in each land-cover class. Summing the pixel counts across all fires within a category yields the overall fractional land-cover composition shown in Fig. 5. Across all groups, the majority of burned area occurs in shrublands, grasslands, and savannas, regardless of the number of structures impacted. This can be partially explained in that fire can propagate much faster in these types of ecosystems5. However, the fraction of forested land cover tends to increase with the number of structures impacted. For fires that affect more than 100 structures, forests account for 34.5% of the burned area—substantially higher than the 8.4% to 20.1% range observed in fires with 100 or fewer impacted structures. Based on data from 2000–2020, fires occurring in forested landscapes are more frequently associated with higher numbers of structures impacted, which is consistent with a previous study41. However, recent events such as the 2021 Marshall Fire and the 2025 Los Angeles fires—primarily grassland and shrubland fires—highlight that extensive structural losses can also occur in non-forested areas. Another notable pattern is the shift in cropland and urban land fractions. Fires that impact more than 100 structures tend to occur in areas with less cropland and cropland/natural vegetation mosaics (0.24%) and more urban and built-up lands (0.49%) compared to those that impact fewer structures (0.45–2.25% for croplands; 0.11–0.28% for urban areas). Fire size is an important driver of structure loss, as larger fires—often more difficult to suppress—have a greater potential to intersect developed areas and affect more structures than smaller, more easily contained fires. At the same time, the disproportionately high emissions from certain states (e.g., Colorado, New York, Michigan) indicate that factors beyond fire size, such as land use patterns and structure density also influence structure fire emissions.

A Fraction of land cover categories across structure fire events grouped by the number of impacted structures. Land cover classification is based on the MODIS Land Cover Type dataset68. The Forests category includes classes 1–5. Shrublands, Savannas, and Grasslands includes classes 6–10. Croplands & Cropland/Natural Vegetation Mosaics includes classes 12 and 14. Urban and Built-up Lands corresponds to class 13. Other MODIS land cover types not shown—such as Permanent Wetlands, Barren, Water Bodies, and Permanent Snow and Ice (classes 11, 15–17)—are excluded due to negligible representation in the fire footprints. B Zoomed-in view of the top 3% of the y-axis (97–100%) from (A), highlighting minor land cover categories. A year-by-year land-cover composition within structure-involved fires can be found in Fig. S5.

We also analyze the influence of fire weather conditions—represented by the Fire Weather Index (FWI), calculated from the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System (CFFDRS)42—on structure-involved fire activity and emissions. The FWI is a widely used proxy for potential fire intensity that combines the influence of temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, and wind speed on fuel availability for combustion across different fuel classes, along with a proxy for fire spread rate (see the Methods section for details). Fire weather conditions show a significant impact on both the burned area and emissions associated with structure fires over the western and eastern U.S. (western and eastern U.S. is separated by -104° longitude). Correlations are notably higher in the West (Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) = 0.75 for burned area; ρ = 0.67 for emissions) compared to the eastern U.S. (ρ = 0.22 for burned area; ρ = 0.18 for emissions) (Fig. 6), indicating that structure fires in the West are more strongly influenced by fire-conducive weather conditions. In contrast, the weaker correlations in the East suggest that other factors—such as land use, local fuel structure, land management, or human activities—may play a more prominent role in regional-scale WUI fire hazard than fire weather. The correlation between FWI and the burned area of wildfires involving structure burning is consistently stronger than that between FWI and emissions. This is partially because fire weather directly influences fire spread, which governs burned area, whereas emissions are additionally affected by the amount and type of structure fuel burned and fire suppression practices. These findings reinforce the role of fire weather as a key driver of structure fire behavior in the western U.S., while also pointing to the need for broader consideration of landscape and human factors in the eastern U.S. Structure-involved fires also exhibit a strong seasonal pattern. For the majority of events—excluding a few highly destructive outliers shown in Fig. 1C—larger burned areas and higher emissions tend to occur in late summer (August–September), coinciding with peak fire weather conditions as indicated by FWI. FWI is a function of the Initial Spread Index (ISI) that represents the potential fire spread rate based on daily weather fluctuations, and a buildup index that represents antecedent conditions from prior months. To assess the sensitivity of our results, we repeat the analysis using ISI alone. While specific correlation values differ slightly, the overall patterns and conclusions remain consistent for FWI and ISI (Fig. S6). This similarity suggests that structure burning in wildfires is primarily influenced by daily weather fluctuations rather than longer-term antecedent conditions.

Monthly total burned area of wildfires that involved structure burning (top row) and CO emissions from burned structures (bottom row) are plotted against monthly mean FWI, with each point representing a month during the 2000–2020 time period. Results are shown for the conterminous U.S. (A, D), the western U.S. (B, E), and the eastern U.S. (C, F). Point color indicates calendar month. Points are colored by month using a continuous color scale arranged to reflect the progression of the annual cycle, with the color of December and January appearing near close to each other. Spearman rank correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values (p) quantify the strength and significance of the associations between FWI and fire outcomes. Spearman rank correlation is used due to non-linear relationships between compared variables and its robustness to outliers. All y-axes are log-scaled. Analysis is restricted to events with non-zero structure burning numbers.

Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive assessment of emissions from burned structures in wildfires across the conterminous U.S., revealing a major but previously unaccounted source of hazardous air pollutants with implications for air quality and public health.

Temporal and spatial patterns of structure fires

The interannual variability and the seasonality together show that temporal patterns of structure and vegetation fires are becoming increasingly decoupled, even though they historically seem to respond to similar large-scale environmental conditions (Fig. 3A; 2002–2015). This suggests the potential for a growing influence of distinct drivers behind high-impact structure fires. Unlike vegetation fires, which are often governed by broad-scale climatic patterns20, destructive structure fires may be more sensitive to localized factors such as land-use change and WUI expansion. ref. 5. analyzed annual wildfire data across the contiguous U.S. for 2001–2020 and found that fast-spreading fires—those growing more than 1620 ha ( ≈ 4000 acres) within a single day—accounted for 78% of structures destroyed and 61% of suppression costs. These differences underscore the need for targeted strategies in forecasting, emission modeling, and risk mitigation that take into account the unique dynamics of structure fire behavior.

Overall, the results indicate that large destructive fires are more likely to occur in forested zones with higher urban and built-up land areas from 2000 to 2020. This shift toward higher proportions of developed and forested land covers within the perimeters of more destructive fires highlights that landscape context plays a critical role in the level of destructiveness of structure fires, and that structure fire risk could be amplified in those land cover types and/or the ability to manage/suppress fires in forested regions may be challenged, even though savanna, shrubland, and grasslands are still the dominant land cover affected. These findings contribute additional knowledge to the conclusions of ref. 11, who suggested annual structure number loss was well explained by area burned from human-ignited fires, while the decadal number of structure loss was explained by state-level structure abundance in flammable vegetation.

In the West, structure-involved fire activity aligns closely with fire-conducive weather (higher FWI–burned-area/emissions correlations), underscoring the role of meteorology and fast-spreading events. In the East, weaker weather–fire relationships point to land-use configuration, local fuel structure, and human activities as relatively stronger determinants of structure losses and emissions.

High-impact events and regional outliers

Four states—California, Colorado, Oregon, and Tennessee—each have at least one year during 2016–2020 in which structure-fire HCl exceeded the state’s anthropogenic total (NEI). Elsewhere, structure-fire HCl is generally lower than anthropogenic totals. While most states remain below anthropogenic totals, structure-involved wildfires occur across most states of the country (Fig. 1A), and severe events can occur outside the West (e.g., the 2016 Tennessee fires). Tennessee does not appear to have a distinctly elevated baseline climate, land cover, or WUI extent relative to neighboring states43,44. Its exceedance is dominated by a single late-season, wind-driven incident with extensive structure loss45,46, indicating that it is possible that similar fire events could occur in other states given similar fuels, weather, and WUI exposure, even if such events are not observed during our analysis period. A small number of such rare, high-impact incidents contribute disproportionately to annual structure fire emissions, highlighting the importance of preparedness and rapid response capacity for tail-risk events.

Air quality and health implications

This study reveals structure fires as a previously under-quantified but significant source of air pollution, with important implications for regional air quality and public health assessments. Beyond the substantial air pollutant emissions they produce, structure fires may have disproportionately greater health impacts compared to other anthropogenic emissions due to the potential for greater exposure to hazardous air pollutants. Because structure-burning emissions are often driven by extreme events, they are intensely concentrated both in time and space and can produce exceptionally high local pollutant concentrations that, depending upon atmospheric dispersion and wind direction, may be more likely to directly impact urban areas. Furthermore, populated locations adjacent to structure fires do not always evacuate if not at immediate risk of fire. This was exemplified in the Eaton fire where the concentrated smoke plume impacted parts of Pasadena that were not evacuated and less than two miles from active fire47. In addition, NEI anthropogenic emissions are annual totals, which may be emitted at low concentrations throughout the year, while structure fire emissions are typically concentrated over much shorter timeframes—often lasting only hours to days. As a result, the pollutant concentrations during structure fires can be substantially higher, leading to more acute exposures in areas impacted by the smoke plume. The potentially greater short-term exposure may lead to increased health risks for nearby populations23, although this is still an active area of research. While direct comparisons remain limited, existing evidence suggests that structure fire smoke contains higher proportions of certain toxicants, potentially increasing risk14,23. These features of structure-burning emissions further emphasize the importance of accounting for structure fires in both emissions inventories and public health evaluations.

Limitations, uncertainties, and future directions

While our estimates provide a nationwide assessment of structure fire emissions, several limitations should be noted. These include uncertainties in structure fuel load estimates, the fraction of fuel burned in damaged structures, hindcasting of historical building counts, and EFs for certain pollutants. Additional limitations, along with quantitative sensitivity analyses, are discussed in detail in the Uncertainty section.

Human activities are responsible for approximately 97% of wildfire ignitions that threaten homes (that are within 1 km of the fire perimeter)48. Our findings further demonstrate that these structure-involved wildfires can emit substantial quantities of hazardous air pollutants that can impact air quality and human health. This study provides a nationwide estimate of emissions from burned structures in wildfires across the conterminous U.S., offering insights into their magnitude, spatial and temporal characteristics, and potential drivers. Our findings highlight that while structure fires contribute a smaller share of total fire emissions than vegetation fires, they can emit high levels of hazardous air pollutants. The growing frequency of large, high-emission structure fires—often occurring in WUI landscapes—emphasizes the need for targeted fire management strategies that consider both land use and fire weather influences.

These results call for greater integration of structure fire emissions into national emission inventories, health impact assessments, and air quality modeling. Mitigation strategies should account for the distinct spatial patterns, potential drivers, and types and quantities of air pollutants emitted by structure fires relative to wildland fires. We note that several uncertainty factors are involved in our estimates of structure fire emissions. Future work should focus on reducing these uncertainties by further improving the characterization of EFs and refining estimates of burned structure fuel. Additional studies should also explore expanding FINN-WUI to understand global WUI fire emissions when relevant information becomes available. From 1992–2015, there were 59 million homes within one kilometer of a wildfire perimeter48. Given documented increases in WUI extent and housing4, the potential for structure-involved wildfires and associated toxic emissions is likely to grow, highlighting the importance of integrating these findings into both mitigation planning and air quality management strategies. It is likely that the confluence of warming and continued development in the WUI to increase future home losses--making quantification of wildfire risk to buildings and their potential emissions critical.

Methods

This study combines geospatial estimates of combustible material (Combustible mass of the building stock in the conterminous United States (COMBUST)31 and high-resolution building count data to reconstruct structure fuel loads over two decades. Fire incident data from the all-hazards dataset mined from the US NIMS (ICS-209-PLUS), paired with fire perimeters from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS) database of large fires, enable event-level attribution of structure loss (including structures destroyed and damaged). These structural parameters are linked with EFs compiled by ref. 14 to estimate pollutant release. A flowchart for estimating emissions from structure burning in WUI fires using the ICS-209-PLUS, COMBUST, MTBS, built-up property locations (BUPL), and Microsoft Building Footprints (MSBF) datasets can be found in Fig. S7. For comparison and validation, we leverage the FINNv2.5 dataset to assess vegetation fire emissions and the EPA NEI to benchmark structure fire emissions against traditional anthropogenic sources. Together, this integrated framework allows us to generate a national structure fire emissions inventory for the 2000–2020 time period, analyze spatial and temporal patterns, and examine potential key environmental drivers. MODIS land cover data and FWI data are used to assist analysis.

COMBUST

The structure fuel in a WUI fire is all the combustible material that is consumed in the fire, which can be wooden structures, furnishings, personal items, etc. The COMBUST dataset31 estimates the structure fuel load, by estimating the combustible mass of the building stock, enumerated in grid cells of 250 × 250 m, including building material, building contents, gas stations, and refineries. The combustible mass of building material is derived from remote-sensing-based data on building volume and building mass, disaggregated by building material components, available for the conterminous U.S. at 10 m spatial resolution for the year 201849. For the production of COMBUST, non-flammable materials from the ref. 49 data were excluded, and mass estimates were resampled to a 250 m grid. The combustible mass of building contents in COMBUST was derived using a method proposed by ref. 50, estimating the mass of flammable building contents based on building indoor area and building function derived from the Zillow Transaction and Assessment Dataset (ZTRAX), a property dataset commonly used in environmental research51. More details are provided in the supplement (Text S1).

MSBF building counts

The MSBF building counts dataset is a derived product from Microsoft’s USBuildingFootprints geospatial vector dataset52. While USBuildingFootprints vector data have been extracted from overhead imagery using deep learning, the MSBF dataset represents an aggregated version of the USBuildingFootprints dataset, aggregated into grid cells of 250 × 250 m, aligned to the COMBUST grid, reporting the number of buildings per grid cell across the conterminous United States. The MSBF building counts are available as part of the COMBUST Plus dataset, accompanying the COMBUST combustible mass estimates, reflecting the approximate U.S. building stock in the year 2020.

Historical settlement data compilation for the U. S. (HISDAC-US) BUPL dataset

HISDAC-US is a collection of gridded datasets measuring different components (building density, building indoor area, settlement age, and building function) over long time periods (i.e., 1810–2020), using large amounts of geocoded building construction year information and other property-level attributes from the ZTRAX dataset53,54. One component of HISDAC-US is the BUPL dataset55, providing semi-decadal, gridded estimates of building densities across the conterminous U.S. from 1810 to 2020 at 250-m grid resolution. HISDAC-US BUPL data captures urbanization processes such as land development, densification and expansion of the built environment56 and is enumerated in the same 250-m grid as the COMBUST dataset.

Incident status summary form plus (ICS-209-PLUS) dataset

The ICS-209-PLUS dataset3 is based on publicly available ICS-209 forms from the U.S. NIMS, comprising daily reports for 34,478 wildland fire incidents from 1999 to 2020. ICS-209 reports are completed for significant incidents and include fields for structures threatened, damaged, and destroyed57. Although only ~1–2% of wildfires become large incidents, they account for ≈95% of the nation’s burned area each year3; consequently, ICS-209-PLUS covers the events responsible for most area burned and underpins NICC’s published ‘structures destroyed’ statistics58. ICS-209-PLUS provides various information on fires, including the number of structures destroyed and the number of structures damaged during a specific fire. In addition, ICS-209-PLUS also provides fire ID, fire source ignition type, and fire point of origin and discovery date. Note that the ICS-209-PLUS dataset only includes burned structures in wildfires and does not include municipal fires.

Fire perimeters

For fire perimeters, we use data from the MTBS Burned Areas Boundaries for 1984–2024 dataset from the USDA Forest Service59. Fire shape for a fire is matched with fires from the ICS-209-PLUS dataset using the fire identifier. MTBS provides consistent assessments of fire size and severity across the conterminous U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. The dataset includes wildfires and prescribed burns that exceed 1,000 acres in the western U.S. and 500 acres in the eastern U.S., covering all land ownership types.

EFs for structure burning

We estimate pollutant emissions by multiplying burned structure fuel with median EFs from a previous study14. We use EFs in units of g kg⁻¹ of structure fuel burned. ref. 14. compiled twenty-eight (28) of the 92 references reported EFs for a total of 346 test conditions covering a range of chemical species that were included in the urban fuel emission factor compilation. We use the median values of the structure fire EFs in our estimation. A concise summary of the EFs used in this study is provided in Table S3.

Fire Inventory from NCAR version 2.5 (FINNv2.5)

FINN provides daily global estimates of pollutant emissions from open fires with a high spatial and temporal resolution for use in air quality, atmospheric composition, and climate modeling applications26. FINNv2.5 uses active fire detections from both MODIS at 1 km resolution and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) at 375-m spatial resolution for the calculation of fire emissions. We use gridded FINNv2.5 data during 2002–202060 with resolution of 0.1 degree \(\times\) 0.1 degree for analysis. In addition, specifically for the year 2020, we also use processed data from our previous study10 which separate FINN vegetation fire emissions to WUI vegetation fire emissions and wildland vegetation fire emissions.

EPA NEI anthropogenic emissions

The U.S. EPA NEI is the most comprehensive and widely used dataset for characterizing anthropogenic emissions in the U.S61. It provides detailed estimates of a broad range of pollutants, including greenhouse gases, criteria air pollutants, and hazardous air pollutants, from major human-related sources such as transportation, industrial processes, power generation, and residential fuel use. The NEI is updated every three years and integrates reported emissions data, activity-based estimates, and standardized modeling techniques. Emissions are typically reported at the county level, enabling spatially resolved analyses. Owing to its consistency and scope, the NEI serves as a critical resource for air quality modeling, regulatory planning, and tracking emissions trends. In this study, we compare structure burning emissions of selected pollutants—specifically HCl and Pb—to NEI anthropogenic emissions for 2020 from the 2020 Air Toxics Screening Assessment (AirToxScreen)62, highlighting the magnitude and relevance of structure burning as a previously unaccounted source of pollution.

FWI and Initial Spread Index (ISI)

FWI from CFFDRS is used in this study due to its widespread use in both operational and research communities, its representation of potential fire hazard as a function of fuel aridity and fire weather—including sensitivities to temperature, precipitation, humidity, and wind speed—and its demonstrated empirical relationships with burned area and extreme fire events across diverse global regions42,63,64,65,66. The FWI integrates the effects of fuel availability through a buildup index that combines three different classes of fuel moisture with the potential rate of fire spread (i.e., ISI). The buildup index incorporates information (e.g., from antecedent precipitation and temperature) on time scales of a couple months to the previous day, and ISI represents daily fluctuations in weather. We calculated daily FWI using the 1/24° gridMET dataset on its native grid67, following the methodology of previous studies65,66. Inputs include daily total precipitation, maximum temperature, minimum relative humidity, and mean wind speed, in place of traditional local noon values, as in prior studies. Calculated FWI is then spatially averaged for regional scale comparisons with WUI fire burn area and CO emissions. We additionally considered ISI from the CFFDRS that is a proxy for fire spread rate based on wind speed and fine-fuel moisture that responds more quickly to meteorological variability.

MODIS Land Cover Type dataset

Land cover type yearly data from 2001 to 2020 from MODIS/Terra+Aqua (MCD12Q1 v6.1)68 are used for land cover type analysis (Fig. 5) across the conterminous U.S. The original resolution of these data is approximately 500 m.

Obtaining structure numbers for previous years

The fuel load dataset COMBUST provides coverage for all years; however, MSBF and the derived gridded MSBF data are only available for 2020, approximately. To estimate historical building counts for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, we used the 2020 MSBF dataset as a baseline and applied scaling factors derived from historical HISDAC-US BUPL datasets. For each U.S. state, we identified grid cells within state boundaries and computed year-specific scaling factors as the ratio of total BUPL values in the target year to those in 2020. These factors were then used to scale the 2020 MSBF building counts and generate proxy estimates for earlier years. This method assumes that temporal changes in BUPL are proportional to changes in building density, enabling reconstruction of historical building distributions where direct data are lacking. For intermediate years (2001–2004, 2006–2009, 2011–2014, and 2016–2019), we performed linear interpolation at the pixel level using the nearest available years. For example, the estimated structure count for 2002 was derived by interpolating between the 2000 and 2005 values.

Structure burning emission estimates

Structure burning emissions are calculated individually for each fire event recorded in the ICS-209-PLUS dataset. We first filter the dataset to identify fires that involved structural damage or destruction. For each fire, the number of structures destroyed and/or damaged is extracted directly from ICS-209-PLUS. We assume that 100% of the structural fuel is consumed for destroyed structures, and 30% is consumed for damaged structures—an empirically chosen value, with associated uncertainties discussed later.

The total structure fuel burned in each fire is calculated as the number of structures affected multiplied by the fuel load per structure within the fire perimeter and the corresponding burn fraction (100% or 30%). Fuel load per structure is estimated by dividing the total structural fuel load from the COMBUST dataset within the fire boundary by the total number of structures from the MSBF dataset within the same area.

For fires with available fire perimeters from the MTBS dataset—primarily large-scale fires—we use the provided fire shapes (see Figure S8). For smaller fires or those without MTBS coverage, we assume a circular fire footprint centered on the point of origin reported in ICS-209-PLUS (also shown in Figure S8). The area of the circular equals to the reported burned area of the fire reported in ICS-209-PLUS.

In cases where there is a mismatch among ICS-209-PLUS, COMBUST, and MTBS—such as when ICS-209-PLUS reports structure involvement but no structural fuel or building count is found in COMBUST or MSBF—we estimate an average fuel load per structure using an expanding search window centered on the fire’s point of origin. We first attempt to calculate this ratio at a 0.01 degree × 0.01 degree resolution. If either the fuel load or structure count is zero at that scale, we expand to 0.1 degree × 0.1 degree, and if still unavailable, to 1° × 1°. This adaptive method ensures that a fuel load per structure can be estimated for all structure-involved fires in the ICS-209-PLUS dataset. This approach was applied in approximately 10% of fire events, though these account for only less than 1% of the total number of structures impacted.

Uncertainty discussion

The estimation of structure burning emissions and the interpretation of the potential impacts of those emissions involves inherent uncertainties. Health risks from structure burning emissions depend on exposure concentrations, which depend on atmospheric dispersion varying for each fire. We address and quantify uncertainties of the emissions where possible at each step of the estimation process. One potential source of uncertainty arises from the reliance on the ICS-209-PLUS dataset, which serves as the basis for identifying structure fires. While this dataset is expected to capture most wildfires involving structural losses, some events—particularly smaller ones—may be missing. However, ICS-209-PLUS is considered comprehensive for large-scale wildfires, which, as discussed earlier, are the primary drivers of emissions. Therefore, any possible missing small fires are unlikely to contribute significantly to total emissions, and we do not consider this a major source of uncertainty.

Structure fuel load is another potential source of uncertainty. The COMBUST dataset provides lower and upper bounds for the combustible mass of the building stock, which we use to estimate the range of possible emissions. Using 2020 as an example, the central estimate of structure fuel burned is 3.10 × 10⁵ metric tons, resulting in 2.14 × 10¹⁰ g of CO emissions. When applying the lower bound of combustible mass, the estimated fuel burned is 2.63 × 10⁵ metric tons with 1.82 × 10¹⁰ g of CO emissions. Using the upper bound, the estimates increase to 3.78 × 10⁵ metric tons and 2.61 × 10¹⁰ g of CO emissions (Figure S9). These bounds represent a decrease of approximately 15% and an increase of 22% relative to the central estimate. Figure S9 also illustrates the sensitivity of estimates to the method used for calculating fuel load per structure. When using a 0.1° × 0.1° ( ~ 10 km) box around each fire’s center instead of detailed fire perimeters, the estimated total structure fuel burned in 2020 increases from 3.10 × 10⁵ to 3.42 × 10⁵ metric tons—a 10% increase, which remains within the uncertainty range defined by the upper and lower bounds. However, applying coarser approaches such as a 1° × 1° box or state-level average fuel loads leads to much larger increases in estimated fuel burned—49% and 55%, respectively. The similarity between the 1° × 1° and state-average results suggests that the 1° resolution is too coarse to capture local variation. These findings indicate that structures burned in wildfires tend to have lower fuel loads than the overall average. A likely explanation is that the COMBUST dataset includes both commercial and residential buildings, while residential structures are more commonly affected by fires. According to ICS-209-PLUS data from 2000–2020, the number of residential structures destroyed is 20.5 times greater than that of commercial structures. When fire shape data or a 0.1° box is used, the selected burned structures more accurately represent real-world situation and their inherent spatial variation. In contrast, broader averaging approaches overrepresent commercial structures, leading to overestimation of fuel load. Using a conterminous U.S.-wide average fuel load per building yields a higher estimated structure fuel burned (5.68×10⁵ metric tons) compared to using state-level averages (4.79×10⁵ metric tons). This is because structure burning emissions are primarily driven by fires in a few key states. For instance, the average fuel load per building in California is 46 metric tons per structure, which is lower than the national average of 51 metric tons per structure.

We approximate 30% of the structure fuel is burned if a structure is reported to be damaged. We do not expect this assumption will significantly change the results because overall the number of damaged structures is not a large fraction. ICS-209-PLUS reported structures destroyed to be 7.7 times more than the number of structures damaged. To evaluate the sensitivity of this assumption on the emission estimates, we calculate structure burning CO emissions for 2020 assuming 10% and 50% of the structure fuel is burned instead of 30% if a structure is reported to be damaged. The resulting estimates are 2.08 × 10¹⁰ and 2.2 × 10¹⁰ g, which are within a range of ±3% of the annual total.

Another potential source of uncertainty arises from the hindcasting of structure fuel loads for years prior to 2020. While COMBUST provides historical fuel load estimates, the MSBF building count data are only available for 2020. As described earlier, we use the BUPL dataset to derive state-level scaling factors and interpolate building counts at five-year intervals. This step is essential for estimating historical structure fuel loads. Here, we assess the differences that would arise if 2020 COMBUST and MSBF data were used for all years, without applying hindcasting of structure fuel loads. While this does not directly quantify the uncertainty introduced by our hindcasting approach, it provides insight into how changes in structure fuel loads over time can affect emission estimates. As shown in Figure S10, using 2020 structure fuel loads for all the years results in a modest increase in total CO emissions from structure burning over 2000–2020—from 2.25×10⁶ to 2.37×10⁶ metric tons, a 5.5% increase. At the annual level, differences are generally under 20%, except for 2000, 2002, and 2005, which have relatively low total emissions and thus limited influence on the overall total. The largest relative difference occurs in 2000 (35%), with the discrepancy declining over time to 0.25% by 2019. Importantly, HISDAC-US BUPL data model historical building density distribution based on the age of the 2020 building stock suffers from a survivorship bias, as buildings that existed in the past and were destroyed and not rebuilt are not reflected in the data. Hence, structure emissions towards the year 2000 may have been slightly higher than our estimates, thus representing a lower boundary of historical emissions in this regard.

A final source of uncertainty lies in the EFs used to convert structure fuel burned into pollutant emissions. In this study, we adopt the median EF values reported by a previous study14, which represent the most comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis currently available. Among all uncertainty sources, EFs may contribute a substantial share to the overall uncertainty in emissions, as they reflect complex combustion processes that vary across structure types, materials, and burn conditions. Given the diversity of buildings and the impracticality of characterizing EFs at the level of individual structures, the use of representative median values is a necessary simplification for regional to national-scale estimation. While this introduces uncertainty, it reflects the best available approach at present. Further refinement of EFs will depend on the availability of more targeted field and laboratory measurements, especially for a wider range of air pollutants and structure types.

This study focuses exclusively on structure-burning emissions from wildfires; emissions from municipal fires are not included. Additionally, emissions from vehicles burned during wildfires are not accounted for, though they may also represent a significant source of hazardous air pollutants. Future research will aim to quantify emissions from burned vehicles to better capture the full spectrum of toxic releases associated with WUI fires.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available without restriction. Source Source Data are provided with this paper and include the numerical values underlying all main and Supplementary Figs. and tables. COMBUST and MSBF building counts data are available at https://zenodo.org/records/1561196431. BUPL is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/hisdacus. ICS-209-PLUS is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19858927.v369. The MTBS data is available at https://www.mtbs.gov. FINNv2.5 is available at https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/d312009/60. EPA NEI anthropogenic emissions are available at https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/national-emissions-inventory-nei. gridMET for FWI and ISI is available at https://www.climatologylab.org/gridmet.html. MODIS Land Cover Type dataset is available at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/. The FINN-WUI product is available at: https://zenodo.org/uploads/1700919532.

Code availability

Code used for analysis in this paper (along with relevant data) can be accessed through: https://zenodo.org/records/1699791970. Code to calculate FWI and ISI can be found on Github (https://github.com/NCAR/fire-indices).

References

Stewart, S. I., Radeloff, V. C., Hammer, R. B. & Hawbaker, T. J. Defining the wildland–urban interface. J. Forestry 105, 201–207 (2007).

National Academies of Sciences, and Medicine. The chemistry of fires at the wildland-urban interface. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press. 2022.

St. Denis, L. A. et al. All-hazards dataset mined from the US National Incident Management System 1999–2020. Sci. Data 10, 112 (2023).

Tang, W., He, C., Emmons, L. & Zhang, J. Global expansion of wildland-urban interface (WUI) and WUI fires: Insights from a multiyear worldwide unified database (WUWUI). Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 044028 (2024).

Balch, J. K. et al. The fastest-growing and most destructive fires in the US (2001 to 2020). Science 386, 425–431 (2024).

Troy, A. et al. An analysis of factors influencing structure loss resulting from the 2018 Camp Fire. Int. J. Wildland Fire 31, 586–598 (2022).

Juliano, T. W. et al. Toward a better understanding of wildfire behavior in the wildland-urban interface: A case study of the 2021 Marshall fire. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101557 (2023).

Roy, D. P. et al. Multi-resolution monitoring of the 2023 Maui wildfires, implications and needs for satellite-based wildfire disaster monitoring. Sci. Remote Sens. 10, 100142 (2024).

Qiu, M., et al. The rising threats of wildland-urban interface fires in the era of climate change: The Los Angeles 2025 fires. The Innovation, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2025.100835.

Tang, W. et al. Disproportionately large impacts of wildland-urban interface fire emissions on global air quality and human health. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr2616 (2025).

Higuera, P. E. et al. Shifting social-ecological fire regimes explain increasing structure loss from Western wildfires. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad005 (2023).

Harries, M. E. et al. A research agenda for the chemistry of fires at the wildland–urban interface: A National Academies consensus report. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 15189–15191 (2022).

Dresser, W. D. et al. Volatile organic compounds inside homes impacted by smoke from the Marshall Fire. ACS EST Air 2, 4–12 (2024).

Holder, A. L., Ahmed, A., Vukovich, J. M. & Rao, V. Hazardous air pollutant emissions estimates from wildfires in the wildland urban interface. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad186 (2023).

Hammer, R. B., Stewart, S. I. & Radeloff, V. C. Demographic trends, the wildland–urban interface, and wildfire management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 22, 777–782 (2009).

Stephens, S. L. et al. Urban–wildland fires: how California and other regions of the US can learn from Australia. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 014010 (2009).

Price, O. & Bradstock, R. Countervailing effects of urbanization and vegetation extent on fire frequency on the wildland urban interface: disentangling fuel and ignition effects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 130, 81–88 (2014).

Ronchi, E., Gwynne, S. M., Rein, G., Intini, P. & Wadhwani, R. An open multi-physics framework for modelling wildland-urban interface fire evacuations. Saf. Sci. 118, 868–880 (2019).

Roos, C. I. et al. Native American fire management at an ancient wildland–urban interface in the Southwest United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018733118 (2021).

Abolafia-Rosenzweig, R., He, C. & Chen, F. Winter and spring climate explains a large portion of interannual variability and trend in western US summer fire burned area. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 054030 (2022).

Cascio, W. E. Wildland fire smoke and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 624, 586–595 (2018).

Silberstein, J. M. et al. Residual impacts of a wildland urban interface fire on urban particulate matter and dust: a study from the Marshall Fire. Air Qual. Atmosphere Health 16, 1839–1850 (2023).

Reid, C. E. et al. Physical health symptoms and perceptions of air quality among residents of smoke-damaged homes from a wildland urban interface fire. ACS EST Air 2, 13–23 (2024).

Kaiser, J. W. et al. Biomass burning emissions estimated with a global fire assimilation system based on observed fire radiative power. Biogeosciences 9, 527–554 (2012).

van der Werf, G. R. et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 697–720 (2017).

Wiedinmyer, C. et al. The Fire Inventory from NCAR version 2.5: an updated global fire emissions model for climate and chemistry applications. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3873–3891 (2023).

Binte Shahid, S., Lacey, F. G., Wiedinmyer, C., Yokelson, R. J. & Barsanti, K. C. NEIVAv1.0: next-generation Emissions InVentory expansion of Akagi et al. (2011) version 1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 7679–7711 (2024).

Seiler, W. & Crutzen, P. J. Estimates of gross and net fluxes of carbon between the biosphere and the atmosphere from biomass burning. Clim. Change 2, 207–247 (1980).

Desservettaz, M. J. et al. Australian fire emissions of carbon monoxide estimated by global biomass burning inventories: Variability and observational constraints. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 127, e2021JD035925 (2022).

Uhl, J. H. et al. COMBUST: Gridded combustible mass estimates of the built environment in the conterminous United States (1975–2020). arXiv preprint, arXiv:2511.08893. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2511.08893 (2025).

Uhl, J. H. et al. COMBUST: Gridded combustible mass estimates of the built environment in the conterminous United States (1975–2020). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15611964 (2025).

Tang, W., et al. (2025). FINN-WUI: Structure-burning emissions from wildland–urban interface fires across the conterminous United States, 2000–2020 (per-fire estimates) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17009195.

Radeloff, V. C. et al. The wildland–urban interface in the United States. Ecol. Appl. 15, 799–805 (2005).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Balch, J. K., Bradley, B. A. & Kolden, C. A. Human-related ignitions concurrent with high winds promote large wildfires across the USA. Int. J. Wildland Fire 27, 377–386 (2018a).

Guzman-Morales, J., Gershunov, A., Theiss, J., Li, H. & Cayan, D. Santa Ana Winds of Southern California: their climatology, extremes, and behavior spanning six and a half decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2827–2834 (2016).

Rolinski, T. et al. The Santa Ana wildfire threat index: methodology and operational implementation. Weather Forecast. 31, 1881–1897 (2016).

NIOSH. Hydrogen Chloride: Acute Exposure Guidelines. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2025-110.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2025-110/

EPA. Health Effects Notebook for Hazardous Air Pollutants. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

World Health Organization. Lead poisoning and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (WHO, 2019).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Basic Information about Lead Air Pollution. https://www.epa.gov/lead-air-pollution/basic-information-about-lead-air-pollution (EPA, 2023).

Radeloff, V. C. et al. Rising wildfire risk to houses in the United States, especially in grasslands and shrublands. Science 382, 702–707 (2023).

Van Wagner, C. E. Development and structure of the Canadian forest Fire Weather Index system. Canadian Forest Service, Forestry Technical Report. (EEA, 1987).

Radeloff, V. C. et al. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 3314–3319 (2018).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen–Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 5, 180214 (2018).

Jiménez, P. A., Muñoz-Esparza, D. & Kosović, B. A high resolution coupled fire–atmosphere forecasting system to minimize the impacts of wildland fires: applications to the chimney tops II wildland event. Atmosphere 9, 197 (2018).

Reilly, M. J., Norman, S. P., O’Brien, J. J. & Loudermilk, E. L. Drivers and ecological impacts of a wildfire outbreak in the southern Appalachian Mountains after decades of fire exclusion. For. Ecol. Manag. 524, 120500 (2022).

Schollaert, C., et al. 2025. Air quality impacts of the January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires: Insights from public data sources. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5c00486.

Mietkiewicz, N. et al. In the line of fire: consequences of human-ignited wildfires to homes in the US (1992–2015). Fire 3, 50 (2020).

Frantz, D. et al. Unveiling patterns in human dominated landscapes through mapping the mass of US built structures. Nat. Commun. 14, 8014 (2023).

Frishcosy, C. C., Wang, Y. & Xi, Y. A novel approach to estimate fuel energy from urban areas. Energy Build. 231, 110609 (2021).

Nolte, C., et al. Data Practices for Studying the Impacts of Environmental Amenities and Hazards with Nationwide Property Data. Land Economics, 102122-0090R. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.100.1.102122-0090R

Microsoft. US Building Footprints [Data set]. Microsoft AI GitHub Repository. https://github.com/microsoft/USBuildingFootprints

Leyk, S. & Uhl, J. H. HISDAC-US, historical settlement data compilation for the conterminous United States over 200 years. Sci. Data 5, 1–14 (2018).

Ahn, Y., Leyk, S., Uhl, J. H. & McShane, C. M. An integrated multi-source dataset for measuring settlement evolution in the United States from 1810 to 2020. Sci. data 11, 275 (2024).

Uhl, J. H. et al. Fine-grained, spatio-temporal datasets measuring 200 years of land development in the United States. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 119–153 (2020).

Leyk, S. et al. Two centuries of settlement and urban development in the United States. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2937 (2020).

NIFC. ICS-209 Program User’s Guide. National Interagency Fire Center. (NIFC, 2023).

NICC. Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2024. National Interagency Coordination Center. (NICC, 2024).

U.S. Geological Survey, USDA Forest Service, & Nelson, K. (2021). Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (ver. 12.0, April 2025) [Data set]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9IED7RZ

Wiedinmyer, C., & Emmons, L. (2022). Fire Inventory from NCAR version 2 Fire Emission [Data set]. Research Data Archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. https://doi.org/10.5065/XNPA-AF09

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). 2020 National Emissions Inventory (NEI) Technical Support Document. Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards. https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/2020-national-emissions-inventory-nei-data, (accessed 5 May 2025).

U.S. EPA. (2024). 2020 AirToxScreen: Assessment Results. https://www.epa.gov/AirToxScreen/2020-airtoxscreen-assessment-results.

Bowman, D. M. et al. Human exposure and sensitivity to globally extreme wildfire events. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0058 (2017).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Williams, A. P., Boschetti, L., Zubkova, M. & Kolden, C. A. Global patterns of interannual climate-fire relationships. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5164–5175 (2018).

Abatzoglou, J. ohnT., Williams, A. P. ark & Barbero, R. enaud Global emergence of anthropogenic climate change in fire weather indices. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 326–336 (2019).

Abatzoglou, J. ohnT. et al. Increasing synchronous fire danger in forests of the western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091377 (2021).

Abatzoglou, J. T. Development of gridded surface meteorological data for ecological applications and modelling. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 121–131 (2013).

Friedl, M., & Sulla-Menashe, D. (2019). MCD12Q1 MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V006 [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12Q1.006.

St. Denis, Lise; et al. (2022). All-hazards dataset mined from the US National Incident Management System 1999-2020. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19858927.v3.

Tang, W. (2025). Code and data for data processing and figure generation for the publication entitled “Emissions from Burned Structures in Wildfires across the Conterminous United States: A Significant Yet Unaccounted Source of Air Pollution” (Version 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16997919.

Schug, F., et al (2023). Map of the global wildland-urban interface (1.1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7941460.

Acknowledgements

This project is primarily funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Atmospheric Chemistry, Carbon Cycle and Climate (AC4) Program (award number: NA22OAR4310204; W.T., L.K.E., C.W., and H.W). This material is based upon work supported by the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is a major facility sponsored by NSF under Cooperative Agreement No. 1852977. Funding for building the HISDAC-US data was provided through the Human Networks and Data Science – Infrastructure program of the US National Science Foundation (award Number 2121976; S.L. and J.K.B.) to the University of Colorado Boulder. The development of the COMBUST dataset was supported by the Open Philanthropy Project. This research also benefited from support provided to the University of Colorado Population Center (CUPC, Project 2P2CHD066613-06) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute of Child Health, Human and Human Development. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or CUPC, or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.T. designed the study, led the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. C.W. and L.K.E. contributed to the study design and interpretation of results. A.L.H. provided emission factor data and contributed to the analysis of hazardous pollutants. J.H.U., M.C., S.L., and J.K.B. developed and provided the COMBUST and BUPL datasets and assisted with data interpretation. R.A.-R. and C.H. contributed to the analysis of fire weather and climate drivers. K.C.B., H.W., and P.F.L. contributed to the interpretation of results. J.T.A. provided fire weather and meteorological data and expertise. All authors discussed the results and contributed to improving the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jihoon Jung and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, W., Wiedinmyer, C., Emmons, L.K. et al. Emissions from burned structures in wildfires as significant yet unaccounted sources of US air pollution. Nat Commun 16, 11443 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66292-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66292-9