Abstract

The rational design of noncentrosymmetric (NCS) inorganic materials remains a longstanding challenge due to unpredictable solid-state reactions and stringent requirements on symmetry breaking. Although perovskites have been widely used as structural templates for NCS materials, their anti-perovskite counterparts remain unexplored. Here, by incorporating Cs+ and Cd2+ ions into a centrosymmetric Na3Cl[MoO4] template, we introduce a heterocationic strategy tailored for anion-centered anti-perovskites that, modifying the conventional BX6 octahedra, yields the polar molybdate Cs2NaCd2Cl3(MoO4)2. The heterocationic sublattice induces pronounced octahedral distortion, breaks inversion symmetry, and aligns the [MoO4] tetrahedra, resulting in a wide band gap of 4.37 eV, a broad transparency window (0.26–5.42 μm and 6.25–10.46 μm), an SHG coefficient twenty times larger than KH2PO4 (d15 = 9.31 pm/V) and a congruent-melting dynamics, enabling single-crystal growth. This work unveils the potential of heterocationic engineering in anion-centered frameworks demonstrating the design of NCS and polar functional materials with excellent nonlinear optical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rationally designing and synthesizing inorganic functional materials is of vital importance for solid-state chemistry and materials science1,2,3, particularly for compounds exhibiting noncentrosymmetric (NCS) and polar structures. These structures are vital for symmetry-dependent properties such as piezoelectricity, ferroelectricity, pyroelectricity, and second-harmonic generation (SHG)4. However, the inherently unpredictable nature of solid-state synthesis and the stringent requirements for symmetry-breaking make the discovery of new NCS compounds both rare and challenging5,6,7. Perovskites (ABX3; A, B = cations; X = anion) have long served as exemplary templates for achieving NCS structures due to their inherent structural versatility and the ability to accommodate adjustable distortions8,9. To date, more than 100,000 perovskite-type compounds have been synthesized and engineered across diverse fields including catalysis, photovoltaics, and luminescence10,11,12. Within these structures, three primary types of structural distortions have been identified, including tilting of the octahedra, displacement of the A-site ions, and distortion of the octahedra. These distortions not only enhance the structural diversity of perovskites but also offer valuable routes for the rational design of their structures13,14,15,16,17.

In addition to perovskites, anti-perovskites (X3BA; A, B = anions; X = cation), which are ionic position-exchange derivatives of perovskites, have commonly emerged as promising material templates, because they can offer comparable structural flexibility and tunability to perovskites18. Especially because the functional anions or anionic groups of anti-perovskites can be anchored at the A-site, where their distortion and orientation can be finely tuned by the surrounding cationic framework19,20,21. These features are particularly important for designing polar and NCS nonlinear optical (NLO) crystals, which are capable of frequency conversion to extend the laser output range22,23,24,25. In previous research, a series of high-performance anti-perovskite NLO crystals, such as Ae3Q[GeOQ3] (Ae=Ba, Sr; Q=S, Se)26, K3X[B6O10] (X=Cl, Br)27,28, and Sr3[CO3][SnOSe3]29 have been rationally designed within anti-perovskite templates. Despite these advances, these reported anti-perovskite NLO materials primarily rely on structural distortions induced by octahedral tilting (Type-I, such as Na3ClMoO430 and Ba3ClFeS431) or displacement of the A-site ions (Type-II, such as Ba3[TO3][SnOQ3])32. The third mode, octahedral distortion (Type-III), remains unexplored in anti-perovskites, presenting a critical knowledge gap.

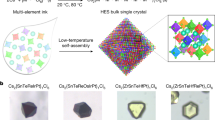

As is well-known, the octahedral distortion in perovskites can typically be achieved by introducing cations with strong Jahn–Teller effects33,34. This strategy, however, is not applicable in anti-perovskites, where the octahedral centers are occupied by anions instead of cations. In this research, we propose a “heterocationic strategy” (analogous to the “heteroanionic” approach in cation-centered compounds35,36,37) that can be employed in anion-centered anti-perovskites to induce obvious octahedral distortion based on the difference of size and electronegativity of various coordinated cations (Fig. 1).

Motivated by these ideas, we chose anti-perovskite molybdate Na3Cl(MoO4) as template to design a new polar and NCS infrared NLO crystal with the following considering: i) the [MoO4] tetrahedron is intrinsically prone to distortion under variations in its local coordination environment, offering a structural basis for symmetry breaking38; ii) molybdate-based compounds can often exhibit broad optical transparency in the mid-infrared (mid-IR) region, moderate birefringence, strong SHG effect, and facile crystal growth39,40. Starting with centrosymmetric a0a0c–-tilted anti-perovskite molybdate Na3Cl(MoO4), we creatively utilize the “heterocationic strategy”, that is, introducing larger Cs+ and aliovalent Cd2+ cations to partly substitute Na+ cations in Na3Cl(MoO4) to construct a strongly distorted B-site octahedral distortion for designing NCS and polar anti-perovskite molybdate, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. Here, Cd2+ serves as a structural and electronic modulator, whereas Cs+ acts as a distortion inducer and symmetry breaker. In its structure, largely distorted heterocationic lattice breaks local symmetry of [MoO4] tetrahedra and constrains their alignment within the octahedral cavity, leading to net polarization along the c-axis. As a result, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 exhibits excellent NLO performances, including: i) a wide band gap of 4.37 eV; ii) strong SHG coefficients (d15 = 9.31 pm/V), over 20 times that of KH2PO4 (KDP, d36 = 0.39 pm/V); and iii) an exceptional transparency range of 0.26–5.42 μm and 6.25–10.46 μm, which is unprecedented among oxide-based molybdates. Additionally, it exhibits congruent melting behavior, enabling the growth of high-quality single crystals up to 18 mm using top-seeded solution growth (TSSG). These properties make [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 promising mid-IR NLO crystal. To gain deeper insight into the origin of these properties, we performed Mulliken population analyses, dipole moment calculations, and the first-principles calculations, which collectively elucidate the structure-composition-property relationships. This work highlights the heterocationic strategy as a highly effective approach for the rational design and synthesis of high-performance functional crystals in anion-centered compounds.

Results and discussion

Crystal structure

[Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was synthesized via the conventional solid-state reaction using stoichiometric amounts of raw reagents (see Synthesis and Crystal Growth for details). Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed the presence of Cs, Na, Cd, Cl, Mo and O with atomic ratios consistent with the expected composition (Supplementary Fig. 1). Phase purity was verified by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

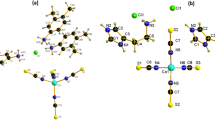

Single-crystal XRD analysis reveals that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 crystallizes in the NCS and polar orthorhombic space group, Pba2 (No. 32) (Supplementary Table 1–4). The asymmetric unit comprises one crystallographic-independent Cs, one Na, one Cd, one Mo, two Cl, and four O atom(s). The Mo6+ cations adopt a tetrahedral coordination with four O atoms, forming [MoO4] groups with the Mo–O distances ranging from 1.698(3) to 1.847(3) Å (Fig. 2a). The Cl– anions exhibit two different coordination environments: the [Cl(1)Cs3NaCd2] and [Cl(2)Cs4Cd2] octahedra. In the former, Cl(1) is coordinated to three Cs+, one Na+ and two Cd2+ cations with the Cl(1)–Cs distances ranging from 3.578(7)–3.761(6) Å, Cl(1)–Na distance being 3.007(6 Å, and Cl(1)–Cd distances ranging from 2.629(8)–2.729(8) Å (Fig. 2b). In the latter, Cl(2) is bonded to four Cs+ and two Cd2+ cations, with Cl(2)–Cs distances ranging from 3.578(7)–3.878(2) and Cl(2)–Cd distances of 2.593(2) Å (Fig. 2c). These heterocationic octahedra are interconnected via edge-, corner-, and face-sharing to form a highly distorted three-dimension (3D) anti-perovskite-like framework, in which the aligned [MoO4] tetrahedra are embedded in the interstitial voids (Fig. 2d). Notably, there exist two topological types of octahedra with different connectivity diagram (CDm)41 in the 2:1 ratio. Bond-valence calculations yield values of 0.90 (Cs+), 0.92 (Na+), 1.98 (Cd2+), 6.14 (Mo6+), 1.94 ~ 2.08 (O2−), and 1.06 (Cl-), consistent with the expected oxidation states42,43.

a–c Basic building units of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2: [MoO4], [Cl(1)Cs3NaCd2] and [Cl(2)Cs4Cd2]. d 3D structure of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. The structural connectivity diagrams of the octahedra forming the anti-perovskite-like framework are shown on the right side; these disordered oxygen atoms and bonds have been omitted for clarity.

Structural evolution of the heterocationic framework

In this work, we elucidate how the heterocationic strategy influences structural symmetry by examining the progressive evolution of heterocationic octahedral frameworks. The transition from the centrosymmetric (CS) parent compound Na3Cl(MoO4) (P4/nmm), to the polar and NCS [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 (Pba2) can be divided into two simple routes: (i) aliovalent cationic substitution and (ii) vacancy and charge compensation. For clarity, a hypothetical intermediate, [NaCdVNa]Cl(MoO4) (where ‘VNa’ denotes a cationic vacancy of Na+ cation), is introduced to describe the structural evolution.

In Na3Cl(MoO4), the X-site of the anti-perovskite framework is uniformly occupied by homogeneous Na+ cations (Fig. 3a), resulting in a minimal distortion (distortion index (D) = 0.019) of [ClNa6] octahedra (Fig. 3b)44. Under such conditions, configurational entropy dominates. Influenced by the shape of the [MoO4] tetrahedron itself, the [ClNa6] octahedra are arranged in antiparallel exhibiting a0a0c– tilt system, resulting in a CS and nonpolar point group 4/mmm. Partial substitution of four Na+ cations in [ClNa6] octahedra by two Cd²+ cations introduces heterocations and creates two cationic vacancies, forming the intermediate [NaCdVNa]Cl(MoO4) (Fig. 3c). Cd2+ was selected as an aliovalent substituent for Na+ owing to its close ionic size and coordination compatibility, which perturbs the local electronic environment and promotes asymmetric Mo–O coordination. The stronger Lewis acidity of Cd2+ and the presence of vacancies induce large local distortions, increasing the octahedral distortion index to D = 0.098 (Fig. 3d). Consequently, the framework undergoes cooperative tilting of adjacent heterocationic octahedra along the c-axis (tilt system a0b–c+), lowering the symmetry to a polar mm2 point group and further guiding the ordered orientation of the A-site [MoO4] groups along the c-axis. To stabilize the vacancy-disrupted framework and achieve charge balance, the [Cs2Cl]∞ chains are introduced, effectively compensating for one Na+ cation and the two associated vacancies. Owing to its considerably larger ionic radius, Cs+ occupies large coordination sites, thereby inducing lattice distortion through elongated Cs–O bonds and lowering the overall symmetry. This leads to the formation of the final compound, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 (Fig. 3e). Due to lower Lewis acid strength and the large ionic radius of Cs+ (1.69 Å) relative to Na+ (0.95 Å), the [ClCs3NaCd2] octahedra exhibit an even larger distortion (D = 0.142), transitioning from a simple corner-sharing network to a more complex structure incorporating corner-, edge- and face-sharing connections (Fig. 3f). Moreover, the smaller [MoO4] tetrahedra, relative to the oversized and distorted anti-perovskite voids, impose additional lattice strain, driving further octahedral tilting and the complete disruption of the original four-fold axis. The synergistic interactions among multi-cations Cs+, Cd2+, and Na+ not only preserve the overall anti-perovskite-like framework but also promote polar alignment of the A-site [MoO4] groups. Clearly, the heterocationic approach obviously increases octahedral distortion, and simultaneously achieves a symmetry-breaking effect similar to that of heteroanionic groups in cation-centered materials45.

Global structures and (b, d, f) local modifications to the octahedron through the transition from (a) the parent Na3Cl(MoO4) with its (b) [ClNa6] octahedron, to (c) the quasi-anti-perovskite [NaCdVNa]Cl(MoO4) and (d) its [ClNa2Cd2VNa2] octahedron, finally to (e) the anti-perovskite [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 and (f) its [Cs4Na2Cd4Cl3] dimer. The distortion index (D) of different octahedra is shown for each structure.

Performance characterization

Despite the progressive increase in octahedral distortion induced by the heterocationic approach, the low global instability index (GII) of 0.086 vu and bond strain index (BSI) of 0.043 vu confirm that all atomic positions in [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 are highly reasonable, resulting in a structurally stable framework46,47. Consequently, the compound exhibits congruent melting behavior. Thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry (TG/DSC) analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3), combined with melting recrystallization experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4) verify that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 undergoes complete melting without decomposition. A high-quality single crystal of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, measuring 18 × 11 × 5 mm3, was successfully grown using the TSSG method with self-flux (Fig. 4a). The obtained crystal exhibited well-faceted growth, with a morphology consistent with predictions based on the Bravais-Friedel-Donnay-Harker (BFDH) model implemented in Mercury program (Supplementary Fig. 5)48. Furthermore, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 exhibits high stability under ambient conditions with no observed deliquescence, and only minor surface dust accumulation was noted after one month of air exposure (Supplementary Fig. 6). Herein, the linear and NLO properties of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 were subsequently investigated based on the obtained high-quality crystals.

a Photograph of a [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 single-crystal sample. b Transmission spectrum of the [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 single crystal, from near infrared to ultraviolet range. c Comparison of the transparency windows of molybdates (red) and other oxide-based NLO materials, including molybdates (orange), niobate (blue), titanates (cyan), borates(purple). Powder SHG measurements at (d) 1064 nm and (e) 2090 nm. The SHG intensity is plotted in arbitrary units (arb. units) to facilitate a direct comparison of the relative intensity. f Demonstration of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 birefringence and cross-polarized images showing interference colors. g Calculated refractive index components of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 at 1064 nm, showing its birefringence. h Performance benchmarking of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 (red) compared to KTP (green) and KDP (blue).

The Ultraviolet-Visible-Infrared (UV–vis-IR) transmission spectrum of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was measured using a 1-mm-thick crystal wafer at room temperature. As shown in Fig. 4b, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 displays a broad transparent region spanning from 0.26 to 5.42 μm and 6.25 to 10.46 μm, with an average transmittance of approximately 80% within these ranges. The wide absorption peaks observed between 5.42 to 6.25 μm is attributed to the potential multi-phonon absorption, a common characteristic of infrared nonlinear optical crystals49,50,51. The fundamental Mo–O stretching vibration of the [MoO4]2– groups is confirmed at 804 cm–1 by the IR spectrum of a polycrystalline sample (Supplementary Fig. 7a). This assignment was further supported by complementary Raman spectroscopic measurement and the calculated vibrational frequencies, which further revealed the corresponding vibrational signatures of MoO4 units (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). The IR cutoff edge was considerably red-shifted as compared to those of other molybdate compounds (LiNa5Mo9O30: 5.26 μm40, MoO2Cl2: 4.54 μm52, LiVMoO6: 4.95 μm53) and was comparable to those of AgGaS2 (AGS) (13 μm)54 and ZnGeP2 (13 μm)55. To the best of our knowledge, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 is the first molybdate with an IR absorption edge exceeding 10 μm, and its transparent region is one of the widest among all oxide-based NLO materials (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 5).

To further evaluate its optical band gap, the UV–vis transmission spectrum was converted to absorption using the Kubelka-Munk function56, yielding an optical band gap of 4.37 eV (Supplementary Fig. 8). This value is notably larger than those of commercially available IR NLO crystals and other molybdate-based materials, such as AgGaSe2 (1.83 eV)57, ZnGeP2 (1.97 eV)55, LaBrMoO4 (3.31 eV)58, and Ag2Mo3Te3O16 (2.85 eV)59.

Generally, the large band gap implies that the title material may have a high laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) value. Therefore, the powder LIDTs of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 and AGS at the particle-size range of 75−106 μm were evaluated using nanosecond pulsed lasers at 1064 nm (Supplementary Table 6). The results show that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 exhibits a remarkably high LIDT value, approximately 100 times higher than that of AGS. This strong damage resistance is comparable to other oxide-based NLO materials, such as LiNbO3 (0.84 GW/cm2) and LiNa5Mo9O30 (1.2 GW/cm2), suggesting its strong potential for high-power mid-IR laser applications40,60.

Due to its polar structure, the SHG intensities of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 were evaluated using Kurtz and Perry method under 1064 nm and 2090 nm laser irradiation, with KDP and AGS serving as the reference materials, respectively61. As shown in Fig. 4d, 4e, the SHG intensity increases with particle size, indicating its phase-matching (PM) behavior across the near- to mid-infrared region. Notably, for particle sizes in the range of 75–106 μm, the SHG intensity of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 is approximately 3.5 times higher than that of KDP at 1064 nm. Under identical particle-size conditions at 2090 nm, its SHG intensity is about 0.2 times that of AGS, slightly exceeding the SHG intensity observed at 1064 nm. Strong SHG responses were observed at both 1064 nm and 2090 nm fundamental wavelengths, confirming the efficient NLO activity of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 across the near- to mid-infrared region. Furthermore, in accordance with the mm2 point group symmetry and Kleinman’s symmetry rules, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 is predicted to have three independent non-zero components of the second-order NLO susceptibility tensor (dij)62. At a wavelength of 1064 nm, the calculated SHG coefficients are d15 = 9.31 pm/V, d24 = 8.58 pm/V, and d33 = −8.53 pm/V. Notably, d15 is 20 times stronger than the d36 coefficient of KDP (0.39 pm/V)63, which strongly suggests that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 is a potential NLO crystal. It should be noted that the apparent discrepancy between the large calculated d15 value and the moderate powder SHG intensity originates from the strong orientation dependence of the effective nonlinear coefficient (deff) in mm2 symmetry and the relatively large phase-matching angles imposed by the crystal’s small birefringence64,65.

In addition, its birefringence was measured using a cross-polarizing microscope, revealing a first-order yellow interference color under cross-polarized light (Fig. 4f). Based on the Michel−Levy chart, the retardation (R values) was determined to be 280 nm. The [010] crystallographic orientation was determined by analysis conducted using a Bruker SMART APEX III diffractometer (Supplementary Fig. 9). As the crystal thickness used for the measurement is 7.6 μm, the birefringence could be calculated as 0.036, which is sufficient to support PM behavior66. Additionally, the calculated birefringence (Δn) of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was evaluated through the first-principles calculations. The refractive index difference (nz – ny) exceeds (ny – nx), classifying [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 as a positive biaxial crystal with the birefringence of 0.034 @ 1064 nm (Fig. 4g). These results indicate that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 is a promising NLO crystal candidate for dual-wavelength applications (Fig. 4h)67,68.

Structure-property relationships

According to Chen’s anionic group theory, the macroscopic nonlinearity of a NLO crystal arises from the geometrical superposition of the microscopic second-order susceptibility of its NLO-active anionic groups69. Therefore, analyzing the distortion and aligned orientation of the [MoO4] group is crucial to understanding the origin of the SHG response. To elucidate this relationship, we examined the coordination environment of A-site anions or anionic groups across three representative frameworks: the ideal cubic anti-perovskite X3BA, the CS Na3Cl(MoO4) and the NCS [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. In the ideal anti-perovskite X3BA, the A-site anions are coordinated by twelve equivalent X-site cations, forming a regular [AX12] polyhedron with six short and six long A–X bonds, reflecting minimal distortion (Fig. 5a). In [Na3Cl](MoO4), each O2- anion of the [MoO4] tetrahedron bonds to one Mo6+ and three Na+ cations, yielding a nearly ideal [(MoO4)Na12] coordination environment (Fig. 5b), thereby suppressing the distortion of [MoO4] group (Table 1)44. In contrast, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 exhibits a reduced coordination number (from 12 to 9), forming a distinctly asymmetric [(MoO4)Cs4Na2Cd3] configuration (Fig. 5c). The incorporation of multiple cations imposes diverse bonding interactions on the O2– anions, promoting the distortion of the [MoO4] tetrahedra, as reflected in the increased bond length distortion parameters (Table 1). These findings highlight the pivotal role of heterocationic engineering in tailoring the coordination asymmetry and enhancing acentric distortion of A-site group in anti-perovskite-related materials.

Coordination environment of the A-site anion or anionic groups (white) in (a) the ideal anti-perovskite X3BA, (b) Na3Cl(MoO4) and (c) [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. d, e Orientation of the [MoO4] tetrahedron in the unit cell and (f, g) its spatial arrangement in the lattice, for (d, f) Na3Cl(MoO4) and (e, g) [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. Elements on the lattice are labeled by colored circles as shown in the legend. The crystal reference frame of [MoO4] (a–c) is indicated by the colored axis. The thick red arrows indicate the orientation of the dipole moment of these [MoO4] groups (f, g).

Beyond the local distortion, the heterocationic superlattice strongly influences the global spatial orientation of A-site groups. In Na3Cl(MoO4), where the octahedra framework are compositionally homogeneous, the [MoO4] tetrahedra exhibit a diagonally reversed orientation (Fig. 5d). Driven by the principle of local electroneutrality and in conjunction with the a0a0c– tilt system, adjacent [MoO4] tetrahedra are arranged in antiparallel, which results in a CS structure (Fig. 5f). However, the introduction of Cs+ and Cd2+ cations in [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 alters this behavior. The presence of three Cd2+ cations in the equatorial plane exerts strong Coulombic attraction, ‘pinning’ three O2− atoms within the same plane (Fig. 5e), thereby promoting a coherent orientation of the [MoO4] groups. Simultaneously, the tilt system transitions from a0a0c− to a0b+c−, favoring a net polar alignment of the [MoO4] tetrahedra along the [001] direction (Fig. 5g). These show that heterocationic approach is an efficient strategy to achieve “symmetry-breaking” and “structure-directing” of the A-site anion group in anti-perovskites.

To better indicate that, Mulliken population (MP) analysis based on first-principles calculations was performed (Supplementary Table 7)70 and the dipole moments of individual structural units within the unit cell were evaluated using the Debye equation (Supplementary Table 8)71. The MP results reveal that the longer Na–O and Cs–O bonds are characterized by relatively low overlap populations (−0.05 ~ 0.14 and −0.1 ~ −0.04, respectively), indicating their predominantly ionic nature. In contrast, the Cd–O bonds exhibit comparatively higher overlap populations (0.21–0.25), reflecting enhanced covalency and stronger Cd2+ and O2– interactions. This disparity in bonding strengths leads to an electrostatically asymmetric environment around the [MoO4] tetrahedron. Notably, one triangular face of [MoO4] unit is preferentially stabilized through stronger bonding of three equatorially positioned Cd2+ cations (Fig. 5e), effectively anchoring the tetrahedron within the cavity and promoting ordered alignment. To study the structural orientation, the dipole moments of [MoO4] units for a unit cell were projected along the [001], [100] and [010] crystallographic directions. As summarized in Supplementary Table 8, the dipole projections along [100] and [010] are both negligible (0.00 Debye), whereas a substantial net dipole of –10.77 Debye is observed along [001], confirming dominant polarization along the c-axis. These findings reinforce that the structural polarity in [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 originates primarily from the cooperative alignment of dipolar units, most notably the [MoO4] groups, within the asymmetric multi-cationic octahedral framework.

To further investigate the optical properties, the electronic structures of title compound was studied using the first-principles calculations72. The results show that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 has an indirect band gap of 3.19 eV (Fig. 6a). The calculated band gap is obviously smaller than the experimental one, which can be attributed to the discontinuity of exchange-correlation energy73. Typically, this calculation method yields band-gap value that is 30–50% smaller than those obtained experimentally74,75. The total and partial density of states (DOS) analysis indicates that the top of valence band (VB) is dominated by O 2p, Cl 2p and Cd 4 d orbitals, while the bottom of conduction band (CB) consists primarily of O 2p, Mo 4d and Cd 5s orbitals. There is a clear hybridization behavior between these orbitals (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the element-projected DOS indicates evident hybridization among Cd 4d, Mo 4d, and O 2p orbitals, especially near the top of the valence band. Although Cd2+ (d10) and Mo6+ (d0) are typically considered electronically inert in directional bonding, the observed orbital overlap implies the presence of weak yet vital covalent interactions. These interactions enhance the local polarization around the [MoO4] tetrahedra and promote their alignment along the c-axis. Therefore, the structural orientation, dictated by both electrostatic and covalent factors, plays a critical role in establishing the NCS lattice and the resulting NLO properties.

a Electronic band structure of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. b The total (gray) and partial (colored) density of states, projected on the constitutional atoms of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, as indicated in the panels of the plot. c Maps of the electron localization function of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 along (001) slices. The isosurface value is set to 0.005 eV Å−3 and the label of the color scale represents the normalized ELF. d Calculated infrared (IR) absorption spectra of [MoO4] tetrahedron and [MoO4Cd3] group. The peaks correspond to the vibrational resonances obtained from Gaussian calculations for the [MoO4] tetrahedron and and [MoO4Cd3] groups.

To gain further insight into the electronic structure and charge distribution, the electron localization function (ELF) was employed. As shown in Fig. 6c, pronounced lobe-shaped and asymmetric electron density distributions are localized around the oxygen atoms, a characteristic signature of highly polarized covalent Mo–O bonds76,77. This reflects strong directional covalency and charge separation, resulting in strong local dipole moments. The directional lone-pair-like orbitals on oxygen are highly polarizable under external fields, enhancing microscopic hyperpolarizability. Furthermore, the cooperative alignment of these Mo–O units in the NCS lattice leads to additive macroscale dipoles, breaking inversion symmetry and facilitating strong SHG response. Thus, MoO4 groups act as key SHG-active motifs. In contrast, the electron density around Cs+ and Na+ ions is more symmetrically distributed, characteristic of ionic bonding with negligible contribution to the SHG response. However, it is worth considering whether Cd2+ ions with the unique d10 orbital will have an impact on the NLO properties?

To investigate the specific role of Cd2+ ions in the NLO properties, we theoretically constructed a fully Ca-substituted model, [Cs2NaCa2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, based on the Cd-structure. This model was subjected to first-principles geometry optimization using a high cutoff energy (860 eV) and a strict convergence criterion (2.0 × 10–6 eV/atom). Although the experimental substitution of Cd with Ca was not achieved due to the high stability and energetically favorable formation of CaMoO4 in this system (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b), this Ca-substituted model relaxed smoothly to a local minimum, confirming the geometric stability of the Ca analogue and its suitability for electronic comparison (Supplementary Table 9). Electronic-structure analysis reveals that the Ca-analogue has slightly larger band gaps (3.36 eV) than [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 (3.19 eV) (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). This can be attributed to the higher electropositivity of Ca2+ and its weaker orbital contribution near the band edges. This trend is consistent with experimental observations in other Ca–Cd isostructural systems, such as CaWO4 (4.94 eV) vs. CdWO4 (4.15 eV)78 and CaMoO4 (3.96 eV)79 vs. CdMoO4 (3.31 eV)80. Furthermore, based on the electronic structures, the NLO coefficients of [Cs2NaCa2Cl]Cl2(MoO4) was also calculated and compared with [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 (Supplementary Table 10). The results clearly show that the Cd-based compound exhibits stronger NLO coefficients than Ca-analogue, confirming that Cd2+ cations indeed contribute positively—though not dominantly—to the NLO properties of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. To visually illustrate the contribution of Cd2+ cations, the PDOS and ELF for each atom in both compounds is provided in Supplementary Fig. 11c–e. The PDOS show that the contributions of Cs, Na, Mo, O and Cl were almost identical, with the main difference arising from the metal cations Ca2+ and Cd2+. In [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, the Cd 3s and 3p orbitals show weak contribution near the Fermi level, while in [Cs2NaCa2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, the Ca2+ contribution near the Fermi level is negligible. In addition, the Cd 4 d orbitals form narrow and deep bands centered around −7 eV, and show weak direct hybridization with the coordinating ions p states (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). Affected by this, Cd2+ ions and their coordinating ions show obvious asymmetric electron density distribution, while Ca2+ exhibits a nearly spherically symmetric electron distribution (Supplementary Fig. 11e), which indicates the unique polarized characteristic of Cd2+ ions. Thus, while the filled Cd 4d10 shell contributes relatively little directly to frontier orbital mixing, it enhances the overall polarizability of the lattice and stabilizes the NCS framework, thereby amplifying the macroscopic second-order susceptibility81. Based on the above analyses, it is clear that the distinct electronic configurations of metal cation have led to fundamentally different structural and NLO behaviors of [Cs2NaCa2Cl]Cl2(MoO4) and [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, although Ca2+ and Cd2+ are close in size. The presence of the polarizable Cd2+ (4d10) center is also indispensable for maintaining both the polar structure and the large NLO response.

To further elucidate the orbital-level origin of the NLO properties, we conducted electron density difference (EDD) analysis via first-principles DFT calculations and also examined the frontier molecular orbitals of the MoO4Cd3 group using Gaussian 0982. The EDD results (Supplementary Fig. 12) reveal distinct charge redistribution, characterized by strong accumulation along Mo–O and Cd–O bonds and negligible depletion around Cs+/Na+, which favor the generation of periodic polarization along the c-axis. This spatial modulation correlates with the frontier orbital asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. 13), where the calculated highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is localized on MoO4 (O 2p orbitals) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) extends toward Cd2+ centers, indicating pronounced characteristics within the MoO4Cd3 groups. Such an orbital arrangement promotes intragroup charge transfer and reinforces the periodic polarization within the Cd-Mo-O layers, providing a direct orbital-level explanation for the observed strong NLO response.

Additionally, we calculated IR vibrational frequency by the Gaussian 09 program on isolated [MoO4] tetrahedra and coordinated [Cd3MoO4] units to elucidate the origin of the unusually broad transparency range up to 10 μm in [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. As shown in Fig. 6d, the IR vibrational modes of isolated [MoO4] tetrahedra are mainly located in the 8–12 μm range, overlapping with the key atmospheric transmission window and thus limiting mid-IR transparency. In contrast, the main vibrational absorption of the [Cd3MoO4] unit exhibits a markedly redshift, with its strongest phonon modes appearing beyond 12 μm. This indicates that the incorporation of heavy, high-electronegativity Cd2+ ions into the anionic framework effectively redshifts the local vibrational frequencies via octahedral distortion and lattice softening, thus expanding the phonon-limited infrared cutoff wavelength from the typical ~5 μm seen in conventional molybdates to as far as 12 μm in this heterocationic system. Notably, a relatively strong absorption is still observed in the 5.42–6.25 μm region (Fig. 4b), which corresponds well with the antisymmetric stretching modes of Mo–O bonds in partially retained or weakly distorted [MoO4] tetrahedra. Together, these results demonstrate that the heterocationic strategy not only introduces distorted anion-centered polyhedra to promote noncentrosymmetry, but also softens lattice dynamics and shifts phonon modes to lower energies, enabling an extended mid-infrared transmission window, which is crucial for IR NLO applications.

To further elucidate the role of phonon-charge coupling in the NLO response of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2, we computed the phonon vibrational spectra using the first principles calculations and evaluated the electron-phonon coupling strength using the Fröhlich polaron model (1) (Supplementary Fig. 14)83,84:

Here, the longitudinal optical phonon frequency is taken as ωLO = 343 cm−1 (from the Raman peak), while the transverse optical phonon frequency is estimated as ωTO ≈ 285 cm−1 (from the phonon spectrum edge). The high-frequency dielectric constant ε∞ = 4.0 is derived from the refractive index (n ≈ 2.0 at 1064 nm), and the static dielectric constant ε0 = 5.7 is obtained using the Lyddane–Sachs–Teller (LST) relation \(\frac{{\varepsilon }_{0}}{{\varepsilon }_{\infty }}=\frac{{\omega }_{{{{\rm{LO}}}}}^{2}}{{\omega }_{{{{\rm{TO}}}}}^{2}}\)). An effective electron mass of m* = 0.7 me, appropriate for a wide-gap semiconductor (Eg = 4.37 eV), yields a Fröhlich coupling constant of α = 0.11. This value indicates weak electron–phonon coupling, which limits its direct impact on nonlinear susceptibility yet effectively suppresses phonon-assisted absorption and scattering. Consequently, it maintains a wide mid-IR transparency window and low losses.

In summary, based on anion-centered anti-perovskite, we innovatively proposed a novel “heterocationic” strategy, which exploits the size and electronegativity differences of multi-cations to construct NCS structures and optimize the functional properties of the material. Selecting anti-perovskite Na3Cl(MoO4) as a template and exploiting the driving forces resulting from multi-cations to optimize the functional group distortion and alignment orientation in anti-perovskites, we obtained a new NCS and polar anti-perovskite molybdate, [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2. It exhibits the widest transparent region covering 0.26–5.42 μm and 6.25–10.46 μm among all molybdates and excellent NLO properties including a large SHG coefficient (d15 = 9.31 pm/V), wide band gap (4.37 eV), moderate birefringence (Δn = 0.034 @1064 nm) and congruently melting behavior, indicating that it is a potential mid-IR NLO candidate. This work not only establishes the viability of heterocationic approach for symmetry breaking in anion-centered systems, but also underscores the broader potential of anti-perovskites as a promising yet underexplored platform for high-performance functional materials. Our findings provide a versatile design paradigm for future discoveries of NCS crystals through targeted distortion engineering in anion-centered architectures.

Methods

Synthesis and crystal growth

Polycrystalline [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was synthesized using a traditional solid-state reaction method by mixing the raw materials CsCl (Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd., 99.9%), NaCl (Tianjin Fu Chen Chemical Co., Ltd., 99%), CdO (Tianjin Fu Chen Chemical Co., Ltd., 99%), and MoO3 (Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd., 99.5%). A mixture of 0.3367 (2.0 mmol) of CsCl, 0.0584 g (1 mmol) of NaCl, 0.2568 g (2 mmol) of CdO, and 0.2879 g (2 mmol) of MoO3 was thoroughly ground, placed into a platinum crucible, and heated in air at 450 °C for 48 h with intermittent regrinding to ensure homogeneity and complete reaction. Thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry (TG/DSC) measurements (Supplementary Fig. 3) and combined with meltingrecrystallization (Supplementary Fig. 4) indicate that [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 melts congruently. When [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was heated to 540 °C, the polycrystalline powder sample completely melted. After the melt was slowly cooled to room temperature, the resulting powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns matched those of the initial polycrystalline sample.

Single crystals of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 were grown via top-seeded solution growth (TSSG) method. A precursor mixture consisting of the polycrystalline product and additional flux components in a molar ratio of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2: CsCl: NaCl: CdO: MoO3 = 3:1:2:2 was finely ground and placed in a platinum crucible. Next, the mixture was heated to 550 °C for 24 h to achieve a homogeneous melt. Nucleation was induced on a platinum wire as the temperature was decreased to 470 °C at 2 °C/h. Some primary seed crystals were observed on platinum wires. To determine the saturation temperature, the melt was cooled in 3 °C steps until microcrystals formed, then reheated stepwise by 1 °C increments, establishing a saturation point at 476 °C. A large [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 crystal was grown at 476 °C at a cooling rate of 0.1 °C/day, followed by slow cooling to room temperature.

Structural characterization

A transparent, well-faceted single crystal of [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 was selected for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis. Data were collected at 273 K using a Bruker SMART APEX II diffractometer equipped with a 4 K CCD detector and Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). And the collected data were processed using the SAINT software suite85, and the structure was solved and refined by the SHELXTL program to obtain the final crystal structure data86. Subsequently, rational anisotropic thermal parameters for all atoms were obtained by the anisotropic refinement and extinction correction using the full-matrix least-squares techniques on Fo287. Anisotropic displacement parameters were refined for all non-hydrogen atoms. A PLATON program symmetry check confirmed that no additional symmetry elements were present88. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this paper have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. CCDC number 2463604 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.

Physical property measurements

Elemental analysis and spatial elemental distribution were acquired using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) attached to a Quanta FEG 250 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, FEI). The experimentally determined elemental composition was consistent with the theoretical stoichiometry (Supplementary Fig. 1). Phase purity was confirmed by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns collected at room temperature on a Rigaku SmartLab 3 kW diffractometer (Supplementary Fig. 2), confirming the phase purity. Optical transparency in the UV–vis–IR region (190–2500 nm) was measured at room temperature with a Hitachi UV–vis–IR spectrophotometer. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer equipped with an ATR module in the 400–4000 cm−1 range.

Laser-induced damage threshold measurement

The LIDTs of the [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 and AGS powders at the particle-size range of 75 − 106 μm were evaluated with 1064 nm laser using the single-pulse method. The measurements were performed by gradually increasing the laser power until a damaged spot was observed under a microscope. The damage thresholds were derived from the equation I(threshold) = E/(πr2τp ), where E is the laser energy of a single pulse, r is the spot radius, and τp is the pulse width.

The powder SHG measurement

The powder SHG responses for [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 were measured using a modified Kurtz–Perry system with laser radiation at an optical wavelength of 1064 nm and 2090 nm61. Powder samples were sieved into narrow particle-size ranges (54–75, 75–100, 100–125, 125–150, 150–180 and 180–250), and KH2PO4 and AgGaS2 powders sieved to the same size ranges served as the references. The birefringence values were determined using a polarizing microscope with plate-shaped crystals and calculated via the equation R = Δn × d, where R, Δn, and d are retardation, birefringence, and thickness of the crystal, respectively.

Dipole moment calculation

To elucidate the orientation of structural units, the total dipole moments of [MoO4], [Cl(1)Cs3NaCd2] and [Cl(2)Cs4Cd2] units for a unit cell in [Cs2NaCd2Cl]Cl2(MoO4)2 were calculated using the bond-valence method and then projected along the [001], [100] and [010] crystallographic directions43,89. Since the occupancy of disordered oxygen atoms in different positions is close to 50%, the three disordered oxygen atoms were divided into two fully ordered configurations: (O2A, O3, O4A) and (O2, O3A, O4). Dipole moments were calculated separately for both models, then averaged according to the 50% occupancy ratio.

Computation methods

To account for the positional disorder of oxygen atoms, a 1 × 1 × 2 supercell was constructed along the c-axis, where one half adopts the (O2A, O3, O4A) configuration and the other half the (O2, O3A, O4) configuration. All density functional theory (DFT) calculations, including geometry optimization and property analyses, were carried out directly on this supercell to represent the disordered structure. First-principles calculations of electronic structure and optical properties were performed within the framework of plane-wave pseudopotential DFT using the CASTEP code72. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was used, along with norm-conserving pseudopotentials (NCP) were employed90,91. The valence electron configurations included Cs (5p66s1), Na (3s1), Cd (4d105s2), Mo (4d55s1), O (2s22p4), and Cl (3s23p5). A plane-wave cutoff energy of 810 eV and a Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid of 3 × 2 × 3 were used for all simulations92. The electronic structures of MoO4Cd3 group at molecular level were calculated using the DFT method implemented by the Gaussian09 package at the 6–31 G level.

Data availability

The representative data and extended datasets that support the findings of this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Additional data are available from the corresponding author. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structure generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystall graphic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition number 2463604. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center under accession code www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wu, M. et al. Target–driven design of deep–UV nonlinear optical materials via interpretable machine learning. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300848 (2023).

Brammer, L. Developments in inorganic crystal engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 476–489 (2004).

Liu, Y., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. Van der Waals integration before and beyond two-dimensional materials. Nature 567, 323–333 (2019).

Marvel, M. R. et al. Cation-anion interactions and polar structures in the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 13963–13969 (2007).

Halasyamani, P. S. & Poeppelmeier, K. R. Noncentrosymmetric oxides. Chem. Mater. 10, 2753–2769 (1998).

Pearson, R. G. A. Symmetry rule for predicting molecular structure and reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 1252–1254 (1969).

Davies, D. anielW. et al. Computational screening of all stoichiometric inorganic materials. Chem 1, 617–627 (2016).

Young, J., Lalkiya, P. & Rondinelli, J. M. Design of noncentrosymmetric perovskites from centric and acentric basic building units. J. Mater. Chem. C. 4, 4016–4027 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Hybrid germanium bromide perovskites with tunable second harmonic generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208875 (2022).

Yin, W. J., Shi, T. & Yan, Y. Unique properties of halide perovskites as possible origins of the superior solar cell performance. Adv. Mater. 26, 4653–4658 (2014).

Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 338, 643–647 (2012).

Deng, J. et al. Br-I ordered CsPbBr2I perovskite single crystal toward extremely high mobility. Chem 9, 1929–1944 (2023).

Lufaso, M. W. & Woodward, P. M. Jahn–Teller distortions, cation ordering and octahedral tilting in perovskites. Acta Cryst. B 60, 10–20 (2004).

Dolgos, M. et al. Chemical control of octahedral tilting and off-axis A cation displacement allows ferroelectric switching in a bismuth-based perovskite. Chem. Sci. 3, 1426–1435 (2012).

Skripnikov, L. V. & Titov, A. V. LCAO-based theoretical study of PbTiO3 crystal to search for parity and time reversal violating interaction in solids. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 054115 (2016).

Garcia-Fernandez, P., Aramburu, J. A., Barriuso, M. T. & Moreno, M. Key Role of covalent bonding in octahedral tilting in perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 647–651 (2010).

Balachandran, P. V. & Rondinelli, J. M. Interplay of octahedral rotations and breathing distortions in charge-ordering perovskite oxides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054101 (2013).

Feng, C. et al. Pressure-dependent electronic, optical, and mechanical properties of antiperovskite X3NP (X = Ca, Mg): a first-principles study. J. Semicond 44, 102101 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Antiperovskites with exceptional functionalities. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905007 (2019).

Le, Y. et al. Transparent glassy composites incorporating lead-free anti-perovskite halide nanocrystals enable tunable emission and ultrastable X-ray imaging. Adv. Photonics 5, 046002 (2023).

Han, D. et al. Design of high-performance lead-free quaternary antiperovskites for photovoltaics via ion type inversion and anion ordering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12369–12379 (2021).

Li, M. et al. A hybrid antiperovskite with strong linear and second–order nonlinear optical responses. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211151 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Decoupling the SHG–birefringence trade–off in UV NLO materials via triple–control coordination engineering: achieving synergistic performance optimization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 137, e202509290 (2025).

Tian, Y. et al. Enhanced UV nonlinear optical properties in layered germanous phosphites through functional group sequential construction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409093 (2024).

Dong, X. et al. Unearthing superior inorganic UV second–order nonlinear optical materials: a mineral–inspired method integrating first–principles high–throughput screening and crystal engineering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318976 (2024).

Cui, S. et al. The antiperovskite-type oxychalcogenides Ae3Q[GeOQ3] (Ae = Ba, Sr; Q = S, Se) with large second harmonic generation responses and wide band gaps. Adv. Sci. 10, e2204755 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Crystal growth and optical properties of a noncentrosymmetric haloid borate, K3B6O10Br. CrystEngComm 13, 2899–2903 (2011).

Wu, H. et al. K3B6O10Cl: a new structure analogous to perovskite with a large second harmonic generation response and deep UV absorption edge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 7786–7790 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Sr3[SnOSe3][CO3]: a heteroanionic nonlinear optical material containing planar π–conjugated [CO3] and heteroleptic [SnOSe3] anionic groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201616 (2022).

Han, S., Bai, C., Zhang, B., Yang, Z. & Pan, S. Synthesis, structure and optical properties of two isotypic crystals, Na3MO4Cl (M=W, Mo). J. Solid State Chem. 237, 14–18 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Antiperovskite Chalco-Halides Ba3(FeS4)Cl, Ba3(FeS4)Br and Ba3(FeSe4)Br with spin super-super exchange. Sci. Rep. 5, 15910 (2015).

Yu, Y. et al. Ae3[TO3][SnOQ3] (Ae = Sr, Ba; T = Si, Ge; Q = S, Se) and Ba3[CO3][MQ4] (M = Ge, Sn; Q = S, Se): design and syntheses of a series of heteroanionic antiperovskite-type oxychalcogenides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 26081–26094 (2024).

Halasyamani, P. S. Asymmetric cation coordination in oxide materials: influence of lone-pair cations on the intra-octahedral distortion in d0 transition metals. Chem. Mater. 16, 3586–3592 (2004).

Ok, K. M. & Halasyamani, P. S. Distortions in octahedrally coordinated d0 transition metal oxides: a continuous symmetry measures approach. Chem. Mater. 18, 3176–3183 (2006).

Jin, C. et al. Hydroxyfluorooxoborate Na[B3O3F2(OH)2]·[B(OH)3]: optimizing the optical anisotropy with heteroanionic units for deep ultraviolet birefringent crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20469–20475 (2021).

Yang, Y. C., Liu, X., Lu, J., Wu, L. M. & Chen, L. Ag(NH3)2]2SO4: a strategy for the coordination of cationic moieties to design nonlinear optical materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21216–21220 (2021).

Kageyama, H. et al. Expanding frontiers in materials chemistry and physics with multiple anions. Nat. Commun. 9, 772 (2018).

Bersuker, I. B. Modern aspects of the Jahn−Teller effect theory and applications to molecular problems. Chem. Rev. 101, 1067–1114 (2001).

Zhou, J., Wu, Q., Ji, A., Jia, Z. & Xia, M. Recent progress in nonlinear optical molybdenum/tungsten tellurites: Structures, crystal growth and characterizations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 524, 216332 (2025).

Zhang, W. et al. LiNa5Mo9O30: crystal growth, linear, and nonlinear optical properties. Chem. Mater. 28, 4483–4491 (2016).

Krivovichev, S. V. Structural diversity and complexity of antiperovskites. Coord. Chem. Rev. 498, 215484 (2024).

Brese, N. E. & O’Keeffe, M. Bond-valence parameters for solids. Acta Cryst. B47, 192–197 (1991).

Brown, I. D. & Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the inorganic crystal structure database. Acta Cryst. B41, 244–247 (1985).

Robinson, K., Gibbs, G. V. & Ribbe, P. H. Quadratic elongation: a quantitative measure of distortion in coordination polyhedra. Science 172, 567–570 (1971).

Cui, S. et al. Chiral and polar duality design of heteroanionic compounds: Sr18Ge9O5S31 based on [Sr3OGeS3]2+ and [Sr3SGeS3]2+ groups. Adv. Sci. 11, 2306825 (2023).

Preiser, C., Lösel, J., Brown, I. D., Kunz, M. & Skowron, A. Long-range Coulomb forces and localized bonds. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B B55, 698–711 (1999).

Abudurusuli, A. et al. Li4MgGe2S7: the first alkali and alkaline-earth diamond-like infrared nonlinear optical material with exceptional large band gap. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24131–24136 (2021).

Docherty, R., Clydesdale, G., Roberts, K. J. & Bennema, P. Application of Bravais-Friedel-Donnay-Harker, attachment energy and Ising models to predicting and understanding the morphology of molecular crystals. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 24, 89–99 (1991).

Bendow, B., Lipson, H. G. & Mitra, S. S. Multiphonon infrared absorption in highly transparent MgF2. Phys. Rev. B 20, 1747–1749 (1979).

Lu, D. et al. La3ZrGa5O14: band-Inversion strategy in topology–protected octahedron for large nonlinear response and wide bandgap. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202503341 (2025).

Li, P.-F., Hu, C.-L., Mao, J.-G. & Kong, F. Pb2(SeO3)(SiF6): the first selenite fluorosilicate with a wide bandgap and large birefringence achieved through perfluorinated group modification. Chem. Sci. 15, 7104–7110 (2024).

Jin, C. et al. Giant mid-infrared second-harmonic generation response in a densely-stacked van der Waals transition-metal oxychloride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310835 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Top-seeded solution growth and characterization of Raman crystal LiVMoO6. RSC Adv. 6, 107519–107524 (2016).

Okorogu, A. O. et al. Tunable middle infrared downconversion in GaSe and AgGaS2. Opt. Commun. 155, 307–312 (1998).

Hesheng, S., Guangqing, Y., Robert, K., Kirby, D. & Aaron, W. Preparation and characterization of several II-IV-V2 chalcopyrite single crystals. J. Solid State Chem. 71, 176–181 (1987).

Landi, S. et al. Use and misuse of the Kubelka-Munk function to obtain the band gap energy from diffuse reflectance measurements. Solid State Commun. 341, 114573 (2022).

Tell, B. & Kasper, H. M. Optical and electrical properties of AgGaS2 and AgGaSe2. Phys. Rev. B 4, 4455–4459 (1971).

Jiao, Z. et al. Heteroanionic LaBrVIO4 (VI = Mo, W): excellence in both nonlinear optical properties and photoluminescent properties. Chem. Mater. 35, 6998–7010 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Hu, C.-L., Hu, T., Kong, F. & Mao, J.-G. Explorations of new second-order NLO materials in the AgI-MoVI/WVI-TeIV-O systems. Dalton Trans. 2009, 5747–5754 (2009).

Bass, M. Nd:YAG laser-irradiation-induced damage to LiNbO3 and KDP. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 7, 350–359 (1971).

Kurtz, S. K. & Perry, T. T. A powder technique for the evaluation of nonlinear optical materials. J. Appl. Phys. 39, 3798–3813 (1968).

Kleinman, D. A. Nonlinear dielectric polarization in optical media. Phys. Rev. 126, 1977–1979 (1962).

PARIKH, K. D., DAVE, D. J., PAREKH, B. B. & JOSHI, M. J. Thermal, FT–IR and SHG efficiency studies of L-arginine doped KDP crystals. Bull. Mater. Sci. 30, 105–112 (2007).

Maker, P. D., Terhune, R. W., Nisenoff, M. & Savage, C. M. Effects of dispersion and focusing on the production of optical harmonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 8, 21–22 (1962).

Armstrong, J. A., Bloembergen, N., Ducuing, J. & Pershan, P. S. Interactions between light waves in a nonlinear dielectric. Phys. Rev. 127, 1918–1939 (1962).

Sørensen, B. E. A revised Michel-Lévy interference colour chart based on first-principles calculations. Eur. J. Mineral. 25, 5–10 (2013).

Hu, C.-L., Han, Y.-X., Fang, Z. & Mao, J.-G. Zn2BS3Br: an infrared nonlinear optical material with significant dual-property enhancements designed through a template grafting strategy. Chem. Mater. 35, 2647–2654 (2023).

Liu, Q. Q., Liu, X., Wu, L. M. & Chen, L. SrZnGeS4: a dual-waveband nonlinear optical material with a transparency spanning UV/Vis and far-IR spectral regions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205587 (2022).

Chen, C. T. et al. Nonlinear Optical Borate Crystals: Principles and Applications. (Wiley-VCH, 2012).

Mulliken, R. S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 23, 1833–1840 (1955).

Debye, P. Polar molecules. By P. Debye, Ph.D., Pp. 172. New York: Chemical Catalog Co., Inc., 1929. $ 3.50. J. Soc. Chem. Ind. 48, 1036–1037 (1929).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Godby, R. W., Schlüter, M. & Sham, L. J. Trends in self-energy operators and their corresponding exchange-correlation potentials. Phys. Rev. B 36, 6497–6500 (1987).

Mao, G. et al. DFT-1/2 and shell DFT-1/2 methods: electronic structure calculation for semiconductors at LDA complexity. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 34, 403001 (2022).

Ernzerhof, M. & Scuseria, G. E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 5029–5036 (1999).

Silvi, B. & Savin, A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 371, 683–686 (1994).

Savin, A., Nesper, R., Wengert, S. & Fässler, T. F. ELF: the electron localization function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36, 1808–1832 (2003).

Lacomba-Perales, R., Ruiz-Fuertes, J., Errandonea, D., Martínez-García, D. & Segura, A. Optical absorption of divalent metal tungstates: correlation between the band-gap energy and the cation ionic radius. J. Appl. Phys. 83, 37002 (2008).

Gancheva, M., Iordanova, R., Koseva, I., Avdeev, G. & Ivanov, P. Direct mechanochemical synthesis of CaMoO4 and Dy3+ doped CaMoO4 nanoparticles and their photoluminescent properties. Ceram. Int. 50, 26361–26370 (2024).

Zhou, L. in, Wang, W. enzhong, Xu, H. aolan & Sun, S. Template-free fabrication of CdMoO4 hollow spheres and their morphology-dependent photocatalytic property. Cryst. Growth Des. 8, 3595–3601 (2008).

Menéndez-Proupin, E., Gutiérrez, G., Palmero, E. & Peña, J. L. Electronic structure of crystalline binary and ternary Cd−Te−O compounds. Phys. Rev. B 70, 035112 (2004).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A. 02 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009).

Fröhlich, H. Electrons in lattice fields. Adv. Phys. 3, 325–361 (1954).

Lautenschlager, P., Garriga, M., Vina, L. & Cardona, M. Temperature dependence of the dielectric function and interband critical points in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 36, 4821–4830 (1987).

Bruker SAINT, Version 8.40B (Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2013).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 64, 112–122 (2008).

Dolomanov, O. V., Blake, A. J., Champness, N. R. & Schröder, M. OLEX: new software for visualization and analysisof extended crystalstructures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 1283–1284 (2003).

Spek, A. L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 7–13 (2003).

Maggard, P. A., Nault, T. S., Stern, C. L. & Poeppelmeier, K. R. Alignment of acentric MoO3F33− anions in a polar material: (Ag3MoO3F3)(Ag3MoO4)Cl. J Solid State Chem. 175, 27–33 (2003).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Rappe, A. M., Rabe, K. M., Kaxiras, E. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Optimized pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 41, 1227–1230 (1990).

Lin, J. S., Qteish, A., Payne, M. C. & Heine, V. V. Optimized and transferable nonlocal separable ab initio pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 47, 4174–4180 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52322202 (H. Y.), 52172006 (H. W.), 22575172 (H. Y.) and 52572012 (H. W.)) and Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (Grant No. 21JCJQJC00090 (H. W.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Y. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and contributed to manuscript writing. H. Y. and H. W. supervised the experiments. S. Y. and H. Y. provided major revisions of the manuscript. Z. H. supervised the optical experiments. J. W. and Y. W. helped the analyses of the crystallization process and the data. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kang Min Ok who co-reviewed with Yunseung Kuk; Bingsuo Zou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Wu, H., Hu, Z. et al. Heterocationic strategy to design a nonlinear optical crystal with a polar anti-perovskite structure. Nat Commun 16, 11446 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66293-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66293-8