Abstract

Selective extraction of KCl from complex salt lake brines remains a challenging task due to the presence of competing ions and the high energy requirements of conventional separation methods. To overcome these limitations, we have developed a biomimetic separation system that integrates three-dimensional (3D) covalent organic framework (COF) membranes with redox-mediated energy harvesting. These COF membranes are designed with sub-nanometer cavity channels decorated with oxygen-containing groups, which enable fine-tuning of electrostatic potential. This design allows for the simultaneous separation of anions and cations through valence-dependent short-range interactions. By coupling the COF membranes with Ag/AgCl redox pairs, the system converts the salinity gradient across the membrane into an internal electric field, facilitating autonomous ion transport without the need for external energy input. The system achieves over fivefold higher flux rates for K+ and Cl⁻ (2.6 and 3.2 mol m–2 h–1, respectively) and demonstrates outstanding separation performance with Cl–/SO42– = 332, K+/Mg2+ = 60, K+/Na+ = 7, and K+/Li+ = 11, substantially exceeding the passive diffusion ratios of 253, 27, 3, and 5, respectively. This work presents a sustainable, scalable approach for extracting valuable resources from complex brines, combining innovative biomimetic membrane design with redox-assisted process engineering, offering a promising solution to the energy and selectivity challenges in industrial ion separation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potassium (K) is an essential element for life, playing a crucial role in agriculture, healthcare, and chemical manufacturing1,2. As the primary compound, potassium chloride (KCl) is vital for global food security, public health, and clean energy technologies3. However, the primary sources of potassium, natural salt lake brines, are chemically complex, containing high concentrations of competing ions such as Mg2+, Na+, Li+, and SO42–4. Extracting KCl from these brines is technically challenging due to the need to separate both cations and anions, a task that conventional techniques often struggle to accomplish5,6,7. Traditional methods, such as evaporation crystallization and ion-exchange resins, are hindered by their high energy consumption and limited ion selectivity. Membrane-based separation offers a more energy-efficient alternative, providing benefits such as lower energy requirements, minimal secondary pollution, and flexible design configurations8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. A common strategy to enhance ion selectivity in membranes involves incorporating fixed charges. Positively charged membranes tend to repel multivalent cations like Mg2+ more effectively than monovalent ions like K+ or Na+, thereby promoting the separation of monovalent ions. Conversely, negatively charged membranes are more effective for anion separation. However, these membranes show reduced performance when separating ions of opposite charge due to electrostatic attraction, making their selectivity highly dependent on the relative charge of the ions and the membrane fixed charge26,27,28,29,30. While membrane-based methods are generally more energy-efficient than traditional approaches, the energy costs associated with pressure- or electricity-driven membrane processes remain a significant bottleneck31,32.

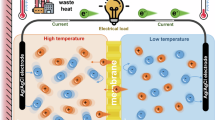

To tackle the dual challenges of selective ion screening and high energy consumption, significant advancements in both membrane materials and separation mechanisms are essential. Biological ion channels offer powerful inspiration, as they achieve exceptional ion selectivity through non-covalent interactions such as ion-dipole and ion-π interactions within sub-nanometer channels. Ion transport in these systems is driven by the electric potential difference across cell membranes, enabling highly efficient translocation with minimal energy input33,34,35,36,37,38. Inspired by these biological systems, we propose covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as a platform for developing biomimetic membranes. COFs exhibit exceptional structural tunability, allowing precise control over pore size, geometry, and surface chemistry39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. This versatility enables the design of membrane environments that closely mimic natural ion-selective channels48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. In previous work, we employed 2D COFs with optimized layer stacking to strengthen ion-π interactions. These aromatic frameworks provide zwitterionic-like charge distributions, allowing selective interaction with both cations and anions61. Notably, the strength of these interactions increases with ion valence, enabling effective discrimination between mono- and divalent ions regardless of their charge signs. However, the planar eclipsed stacking typical of 2D COFs often limits access to potential binding sites. To overcome this limitation, we developed 3D COF membranes featuring cavity structures tailored to the size of hydrated ions. This geometric confinement enhances ion-dipole and ion-π interactions, particularly for multivalent ions, leading to significantly improved separation performance (Fig. 1).

a Biological ion channels achieve precise ion selectivity through noncovalent interactions, regulated by the electric potential difference across cell membranes (red: positive potential; blue: negative potential). b Schematic of a 3D COF membrane with subnanometer pores and zwitterionic-like charge distributions (red: positive potential; blue: negative potential). This architecture strengthens valence-dependent short-range interactions and integrates redox pairs, enabling conversion of the salinity gradient into an electric field to drive autonomous ion transport without external energy input.

Building on this strategy, we synthesized a family of isostructural 3D COF membranes using tetra-amine and triangular aldehyde monomers to form sub-nanometer pores. To refine electrostatic interactions and improve ion selectivity, we incorporated oxygen-containing functional groups into the pore walls. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and transition-state theory indicate that this design lowers the energy barrier for K+/Cl⁻ transport while effectively excluding Mg2+/SO42– ions through a combination of steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion. To replicate the ion transport mechanisms of biological membranes, we integrated redox-active electrodes that exploit the natural salinity gradient between feed and receiving chambers. This configuration generates an internal electric field, enabling energy-autonomous ion transport. Among the various membranes developed, the COF-TFB-OMe featuring methoxy-functionalized pores exhibited outstanding selectivity when tested with simulated brine from the Salar de Atacama. It achieved separation ratios of Cl⁻/SO42– = 332, K+/Mg2+ = 60, K+/Na+ = 7, and K+/Li+ = 11, representing improvements of 1.3-, 2.2-, 2.3-, and 2.2-fold over diffusion dialysis, respectively, ranking it among the top-performing systems (Supplementary Table 1). These results stem from two synergistic mechanisms: (1) a build-in electric field generated by osmotic energy that accelerates K+ transport, and (2) redox-induced selective migration of Cl⁻ ions. Consequently, the system achieved K+ and Cl⁻ fluxes of 2.6 and 3.2 mol m–2 h–1, respectively, more than five times higher than passive diffusion, and 1.3 times greater than fluxes obtained using an external electric field. Through the integrated design of membrane structure and transport processes, this work offers a promising strategy for sustainable, energy-efficient resource recovery from complex brines.

Results

Membrane synthesis and characterization

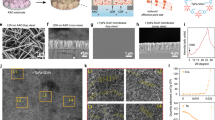

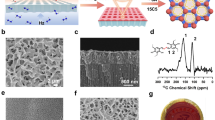

To implement our biomimetic strategy for selective KCl recovery, we synthesized a series of 3D COF membranes with sub-nanometer channels. These membranes were fabricated via interfacial polymerization on the polyacrylonitrile (PAN) substrate. The reaction took place at 35 °C over 3 days, involving the contact of an organic phase containing aldehyde monomers with an aqueous phase containing tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)methane (TAM) and acetic acid on opposite sides of the PAN support. Condensation between TAM and three different triangular aldehydes 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (TFB), 2,4,6-trimethoxybenzene-1,3,5-tricarbaldehyde (TFB-OMe), and 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol (TFB-OH) resulted in distinct membrane colors: light green (COF-TFB), orange (COF-TFB-OMe), and yellow (COF-TFB-OH) (Supplementary Fig. 1). While these COFs share a common topology and pore structure, they differ in functional groups (–H, –OMe, –OH), enabling us to systematically investigate how pore-wall chemistry influences ion interactions, thereby mimicking the selective environments of biological ion channels (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Comprehensive structural characterization confirmed successful membrane formation. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and solid-state 13C NMR spectra confirmed the complete formation of imine (C = N) bonds in COF-TFB and COF-TFB-OMe. In contrast, COF-TFB-OH exhibited β-ketoamine linkages, as evidenced by a characteristic carbonyl peak at 185.3 ppm and new C–N and C = C vibrational bands in the FTIR spectra (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4)58,62. Electrostatic potential (ESP) simulations revealed notable differences in both the magnitude and spatial distribution of surface charges within the membrane cavities, indicating distinct short-range ion interaction profiles (Fig. 2a). Zeta potential measurements further quantified the influence of surface chemistry, showing values of -1.8, -10.7, and -6.4 mV for COF-TFB, COF-TFB-OMe, and COF-TFB-OH, respectively. These values align with the electron-donating nature of the functional groups (Fig. 2b). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed the successful formation of continuous, defect-free COF layers on the PAN substrate. The membrane thickness slightly increased with bulkier substituents, 300 nm for COF-TFB, 320 nm for COF-TFB-OH, and 400 nm for COF-TFB-OMe (Supplementary Figs. 5–8). Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns revealed crystallinity in all membranes, though the WAXS signals were relatively weak. This is primarily due to the thinness of the COF layers on the PAN substrate, which reduces diffraction intensity. Notably, when using COF-TFB-OMe, stacking two membranes significantly enhanced the WAXS signal. After detaching the COF layer from the PAN substrate using DMF treatment and performing powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) measurements, we observed a substantial increase in diffraction peak intensity, with peaks corresponding to a simulated cubic lattice (space group I-43d) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9). N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms, analyzed using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, showed that as the steric bulk of the substituents increased, BET surface areas declined from 909 m2 g–1 (COF-TFB) to 855 m2 g–1 (COF-TFB-OH) and 787 m2 g–1 (COF-TFB-OMe) (Fig. 2d). Pore size distributions determined via nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) indicated uniform pore diameters centered around 5.8 Å for all variants (Fig. 2d, inset). Positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS) further confirmed pore size tuning, detecting a consistent reduction in cavity size from 6.4 Å in COF-TFB to 5.9 Å in COF-TFB-OMe (Fig. 2e). This trend reflects increasing steric hindrance from –H to –OMe groups, demonstrating our ability to precisely tailor ion-sieving architectures. The small discrepancy between NLDFT and PALS arises because NLDFT relies on averaged density profiles across pore walls, which may obscure subtle variations caused by encapsulated or substituted groups. In contrast, PALS directly probes the interconnected free volume, making it more sensitive to local structural changes. Nevertheless, both techniques consistently confirm the presence of uniform pore channels and provide strong evidence for the crystalline nature of the synthesized COF membranes. Importantly, all measured pore sizes were smaller than the hydrated diameters of both K+ (6.62 Å) and Cl⁻ (6.64 Å), confirming the spatial confinement necessary for selective ion transport (Supplementary Fig. 10)63,64.

a Schematic of the synthetic pathway and chemical structures of COF-TFB, COF-TFB-OMe, and COF-TFB-OH, along with ESP maps projected onto their van der Waals surfaces. b Zeta potential of the membranes measured in 1 mM KCl at pH 6.5. c WAXS patterns, including a magnified region and a simulated PXRD pattern based on the I-43d space group. d N2 sorption isotherms collected at 77 K; inset displays pore size distribution derived using the NLDFT method. e Pore size distribution determined via PALS.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

Prior to experimental validation, we performed MD simulations to investigate ion transport behavior through the synthesized COF membranes. The dynamics of monovalent ions (K+, Cl–) and divalent ions (Mg2+, SO42–) were analyzed under binary salt conditions (0.5 M each) (Supplementary Figs. 11–13). Ion trajectories along the z-axis were tracked, with membrane interfaces marked by gray dashed lines. Among the membranes studied, COF-TFB-OMe exhibited the highest translocation probabilities for both K+ and Cl⁻ (Fig. 3a, b). Snapshot analyses revealed distinct ion permeation behaviors: K+ and Cl⁻ rapidly traversed COF-TFB-OMe, whereas Mg2+ and SO42– showed significantly reduced mobility (Fig. 3c, d, and Supplementary Figs. 14–16). Hydration shell analysis indicated partial dehydration of ions upon entering the membrane channels, particularly in COF-TFB-OMe, where the smaller pore size led to more pronounced disruption of ion solvation (Supplementary Fig. 17). Remarkably, despite having the smallest pore size, COF-TFB-OMe achieved the highest diffusion coefficients `of 1.1 × 10–5 cm2 s–1 for K+ and 1.8 × 10–5 cm2 s–1 for Cl⁻. Notably, Cl⁻ diffusion in COF-TFB-OMe even exceeded its bulk diffusion rate (1.5 × 10–5 cm2 s–1), indicating favorable ion-membrane interactions. In contrast, diffusion of Mg2+ (2.5 × 10–6 cm2 s–1) and SO42– (2.7 × 10–6 cm2 s–1) was significantly suppressed, resulting in enhanced monovalent/divalent ion selectivity compared to other COF variants, indicative of the exceptional selectivity of COF-TFB-OMe for KCl transport (Fig. 3e–g).

a, b Ion trajectories along the z-axis for (a) Cl⁻ and SO42–, and (b) K+ and Mg2+ ions passing through various membranes. c, d Simulation snapshots illustrating the transmembrane transport behavior of (c) Cl− and SO42– ions and (d) K+ and Mg2+ ions across COF-TFB-OMe. Color scheme: cyan, COF-TFB-OMe membrane; blue, Cl⁻; red and yellow, SO42–; purple, K+; bright yellow, Mg2+. e–g Mean square displacement (MSD) curves for the four ions in (e) COF-TFB, (f) COF-TFB-OMe, and (g) COF-TFB-OH membranes. Dashed lines represent self-diffusion coefficients, while solid lines correspond to transmembrane diffusion coefficients.

Ion separation performance evaluation

To experimentally validate the ion transport behavior predicted by MD simulations, we measured the single-salt permeation of 0.1 M KCl, K2SO4, and MgCl2 solutions through PAN, COF-TFB, COF-TFB-OMe, and COF-TFB-OH membranes with an effective area of 2.5 cm2. As anticipated, the PAN support exhibited high permeability for all salts, with fluxes of 0.4 ± 0.02, 0.2 ± 0.01, and 0.2 ± 0.02 mol m–2 h–1 for KCl, K2SO4, and MgCl2, respectively, indicating negligible ion selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 18). In contrast, COF-TFB-OMe demonstrated the highest flux for KCl (0.2 ± 0.03 mol m–2 h–1), which was 121 ± 4 times greater than for K2SO4 and 23 ± 1 times greater than for MgCl2, confirming its strong dual selectivity for K+ over Mg2+ and Cl⁻ over SO42–. COF-TFB, while maintaining a similar MgCl2 flux to COF-TFB-OMe, exhibited a significantly lower KCl flux (0.014 ± 0.001 mol m–2 h–1) and twice the flux for K2SO4, resulting in reduced selectivity (KCl/K2SO4 = 4 ± 1; KCl/MgCl2 = 2 ± 0.2). COF-TFB-OH showed the lowest overall permeability, with a KCl flux 238 ± 18 times lower than that of COF-TFB-OMe and limited selectivity (KCl/K2SO4 = 6 ± 1; KCl/MgCl2 = 2 ± 0.5). These experimental trends align with MD-derived diffusion coefficient ratios for Cl⁻/SO42– and K+/Mg2+, following the order of COF-TFB-OMe > COF-TFB-OH > COF-TFB (Fig. 4a). Notably, COF-TFB-OMe maintained high selectivity across a broad concentration range (0.05–0.5 M), with KCl/K2SO4 selectivity increasing from 117 ± 12 to 140 ± 17 at higher concentrations (Supplementary Figs. 19–21), further demonstrating its robustness. To assess scalability, we fabricated a larger COF-TFB-OMe (13.5 × 11.5 cm2) using the same interfacial polymerization method. Ion separation performance was evaluated at multiple regions across the larger membrane, and the results showed consistent flux and selectivity across the entire surface, comparable to those of the smaller one (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23).

a Salt flux and selectivity of different membranes tested under single-salt conditions (0.1 M for each salt). b Apparent activation energies (\({E}_{a}\)) for electrolyte transport across the COF-TFB, COF-TFB-OMe, and COF-TFB-OH membranes. c Calculated energy barriers for ion transport across the membranes. d Ion flux and selectivity of different membranes under binary-salt systems (0.1 M for each salt). e Comparison of ion flux and selectivity for the COF-TFB-OMe membrane under dialysis and electrically driven conditions in a ternary salt system. f Recyclability test of the COF-TFB-OMe membrane under electro-driven operation over multiple cycles. Error bars in the figures represent standard deviation obtained from three independent experiments using membranes prepared from different batches.

To explore the mechanistic origins of the selectivity differences among these membranes, we conducted temperature-dependent salt flux measurements under concentration-gradient-driven conditions (single-salt solution vs. deionized water). Activation energies (\({E}_{a}\)) were derived from the slopes of linear Arrhenius plots. For all membranes, the \({E}_{a}\) values followed the trend KCl < MgCl2 < K2SO4, consistent with the more energetically favorable transport of monovalent ions. Among the membranes, COF-TFB-OMe exhibited the lowest \({E}_{a}\) for KCl, with activation barriers 10.1 and 13.6 kJ mol–1 lower than those for MgCl2 and K2SO4, respectively, supporting its strong monovalent selectivity. In contrast, COF-TFB-OH displayed a higher KCl activation barrier (37.4 kJ mol–1), only ~5 kJ mol–1 lower than those for MgCl2 and K2SO4, suggesting weak selectivity and low salt flux. COF-TFB exhibited similar \({E}_{a}\) values across all salts (31.5–33.3 kJ mol–1), with the KCl activation energy roughly 6 kJ mol–1 lower than that of COF-TFB-OH. This modest difference, combined with uniformly lower activation energies, accounts for its limited selectivity but significantly higher ion flux of COF-TFB, approximately 16 times greater than that of COF-TFB-OH (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 24).

Mechanistic insights into ion selectivity via transition-state theory

To further elucidate the mechanisms governing ion selectivity within the confined channels of COF membranes, we applied transition-state theory, a molecular-level framework that captures ion diffusion through sub-nanometer pores by accounting for both enthalpic (\(\Delta H\)) and entropic (\(\Delta S\)) contributions between the ground and transition states. Ion selectivity arises from differences in the total energy barrier (\(\Delta G=\Delta H-T\Delta S\)) encountered by individual ions during transport. To decouple cation and anion behavior, we applied an external electric field to induce electrically mediated ion transport. This approach contrasts with concentration-driven transport, which involves the electroneutral movement of salt pairs, and instead allows us to probe ion-specific dynamics. Each ion contribution to the overall current is quantified by its transference number (\({t}_{+}\) for cations, \({t}_{-}\) for anions), determined from membrane potential measurements65. We extracted ion-specific activation energies (\({E}_{a,\pm }\)) from temperature-dependent measurements of membrane conductance and transference numbers, based on the following relationship:

with the associated thermodynamic definitions:

In these equations, \(z\) is ion valence, \(G\) is the total membrane conductance, \({B}_{\pm }\) is the pre-exponential factor, and \(T\) is absolute temperature. \({N}_{a}\), \(h\), \(F\), and \(R\) represent Avogadro constant, Planck constant, Faraday constant, and gas constant, respectively. \(\lambda\) is the assumed jump distance between equilibrium positions (assumed to be 5 Å), \(\delta\) is the membrane thickness, and \({C}_{0}\) is the ion concentration (mol m–3).

Importantly, the measured \({E}_{a,\pm }\) values closely matched the weighted averages derived from corresponding salt solutions, validating this electrochemical framework (Supplementary Figs. 25–27)65. The \(\Delta H\) reflects specific ion-membrane interactions, such as dehydration, electrostatic interactions, and ligand coordination, that govern ion partitioning and translocation. Interestingly, despite having a smaller average pore size (5.9 Å) than COF-TFB (6.4 Å), COF-TFB-OMe exhibited a lower \(\Delta H\) for K+ transport (18.2 vs. 20.2 kJ mol–1), suggesting that dehydration penalties are offset by favorable interactions within the pore66. We attribute this to a stabilizing microenvironment in COF-TFB-OMe, which facilitates K⁺ entry. DFT calculations confirmed strong K+ interactions with nitrogen and oxygen atoms from imine linkages and methoxy groups in COF-TFB-OMe (Supplementary Fig. 28). Entropy analyses further support this interpretation. The entropic penalty (\(-T\Delta S\)) for K+ transport was higher in COF-TFB-OMe (27.9 kJ mol–1) than in COF-TFB (26.1 kJ mol–1), indicating stronger confinement and reduced ionic mobility in the functionalized pores. For multivalent ions such as Mg2+ and SO42–, COF-TFB-OMe showed the highest \(\Delta H\) and \(-T\Delta S\) values among all tested membranes, resulting in the largest overall energy barriers (Fig. 4c). This dual-functionality, which lowers energy barriers for monovalent ions while increasing them for divalent ions, underscores the potential of COF-TFB-OMe for selective KCl recovery from brine.

Performance of COF membranes in mixed salt systems

We next evaluated the ion separation performance of COF membranes in binary salt systems containing equimolar mixture of KCl/K2SO4 or KCl/MgCl2 (0.1 M each). For COF-TFB-OMe, the Cl⁻ flux remained consistent with that observed in single-salt experiments, while the SO42– flux decreased by 6.1% and the Mg2+ flux increased by 1.4-fold. Consequently, the KCl/K2SO4 selectivity improved from 121 ± 4 to 132 ± 5, whereas the KCl/MgCl2 selectivity decreased from 23 ± 1 to 13 ± 0.3. In contrast, COF-TFB and COF-TFB-OH exhibited minimal selectivity under the same conditions, with KCl/K2SO4 and KCl/MgCl2 selectivity ratios remaining below 4 and 4, respectively. Notably, COF-TFB-OMe not only delivered superior selectivity but also achieved markedly higher KCl permeability, 10 times greater than COF-TFB and 100 times greater than COF-TFB-OH (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30). To further probe its separation behavior, we investigated the impact of feed concentration. As the salt concentration increased from 0.05 to 0.5 M, KCl/K2SO4 selectivity gradually increased from 128 ± 5 to 137 ± 2, while KCl/MgCl2 selectivity showed a slight decline (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32). These contrasting trends point to distinct mechanisms governing anion and cation discrimination. The increased Cl⁻/SO42– selectivity at higher concentrations likely arises from the greater free energy barrier for SO42– transport, which promotes its aggregation in the feed solution. This effect intensifies with concentration, while Cl⁻ transport remains largely unaffected. MD simulations support this, showing a relative increase in Cl⁻ permeability compared to SO42– at elevated concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 33). In contrast, the reduced K+/Mg2+ selectivity under high-salinity conditions is likely due to the constraint of charge neutrality.

Since Mg2+ does not readily aggregate and COF-TFB-OMe preferentially transports Cl⁻, the increased permeation of Cl⁻ at higher concentrations necessitates compensatory Mg2+ transport to maintain charge balance. This, in turn, reduces the membrane ability to distinguish between monovalent and divalent cations (Supplementary Figs. 34 and 35). To evaluate the practical viability of COF-TFB-OMe for KCl recovery, we tested it in a ternary salt mixture (0.1 M equimolar KCl/K2SO4/MgCl2). The membrane maintained strong selectivity, achieving Cl⁻/SO42– and K+/Mg2+ selectivity ratios of 143 ± 1 and 15 ± 1, respectively, with a Cl⁻ flux of 0.5 mol m–2 h–1 (Fig. 4e). Under electrically driven conditions (–1 V across Pt electrodes), Cl⁻ flux increased by >50% without compromising selectivity. Notably, in this electrochemical ion transport process, ion separation is driven by the applied electric field rather than hydraulic pressure. Consequently, water migration is negligible, and the feed-side salt concentration decreases gradually over time, thereby avoiding the progressive salt accumulation and filter cake formation commonly observed in pressure-driven processes. Long-term stability tests confirmed that the membrane exhibited no observable fouling or performance degradation, maintaining consistent flux and selectivity over 10 consecutive cycles, underscoring its robustness and suitability for practical ion separation applications (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 36).

Redox-mediated, energy-autonomous KCl extraction from brine

COF-TFB-OMe exhibits remarkable selectivity for KCl in single-salt, binary, and ternary systems, demonstrating significant potential for extracting KCl from salt lake brines. These natural brines, such as those from Chile’s Atacama Salt Lake, typically contain high concentrations of KCl along with substantial amounts of competing ions like Mg2+ and SO42–. To evaluate the membrane practical performance, we tested it in a synthetic brine replicating the composition of magnesium sulfate-type brine from the Atacama region67. This synthetic brine (per 500 g of solution) contained NaCl (20.3 g), KCl (2.3 g), MgCl2 (41.8 g), LiCl (4.9 g), and K2SO4 (34.5 g). Under passive dialysis conditions, COF-TFB-OMe achieved high ion fluxes for K+ (0.5 mol m–2 h–1) and Cl⁻ (0.6 mol m–2 h–1), with excellent selectivity in receiving solution (Cl–/SO42– = 253; K+/Mg2+ = 27; Fig. 5a).

Recognizing the potential to enhance ion transport using electric fields and the substantial osmotic energy from the concentration gradient between the feed and receiving solutions, we implemented a redox-mediated system powered by this salinity gradient. Using Ag/AgCl electrodes, we established an internal electric field without needing an external power source68,69,70. The electrochemical potential between the Ag (feed side) and AgCl (receiving side) electrodes drives electron flow, capturing Cl⁻ at the feed electrode and releasing it at the receiving electrode. This process is expected to not only increases ion flux but also enhances ion selectivity. However, when the receiving side was filled with H2O and integrated with Ag/AgCl, only a limited increase in ion permeance (less than 5%) was observed. This limitation was primarily due to the internal cell resistance, which was constrained by the low conductivity of the receiving solution. To address this limitation, we increased the KCl concentration in the receiving side, though, in principle, other electrolytes could also be employed. While this adjustment decreased OCV from 108.5 mV at 1 mM KCl to 56.8 mV at 100 mM, it significantly boosted ion flux (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 37). For example, under redox-driven conditions, Cl⁻ and K+ fluxes increased from 0.6/0.5 mol m–2 h–1 (passive dialysis) to 0.9/0.7 (1 mM), 1.9/1.3 (10 mM), and 3.2/2.6 mol m–2 h–1 (100 mM). Selectivity was also enhanced, with Cl–/SO42– = 332 and K+/Mg2+ = 60, outperforming passive dialysis (253/27). Furthermore, the membrane displayed high selectivity against Na+ and Li+ (K+/Na+ = 7; K+/Li+ = 11), leading to a receiving solution composition in which K+ and Cl– accounted for 93.7% of the total ion content, confirming efficient and targeted ion conduction (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 38). The observed K+ selectivity over Na+ and Li+ is attributed to its smaller hydrated radius, which is still larger than the membrane pore size but closer to it than that of Na+ or Li+. In addition, COF-TFB-OMe exhibited moderate Li+/Mg2+ selectivity of 6, suggesting its potential for Li+ enrichment from salt lake brines (Supplementary Fig. 39).

Comparative experiments using Pt electrodes further underscored the advantages of redox mediation. At an applied voltage of 60 mV, comparable to the OCV at 100 mM KCl, Pt electrodes exhibited lower ion fluxes (Cl–: 2.5; K+: 1.9 mol m–2 h–1) and reduced selectivities (Cl–/SO42– = 266; K+/Mg2+ = 55). Increasing the voltage to 1 V enhanced ion fluxes (Cl–: 4.3; K+: 2.5 mol m–2 h–1) but further deteriorated selectivity (Cl–/SO42– = 253; K+/Mg2+ = 47), highlighting the benefits of operating redox-mediated systems at moderate voltages (Fig. 5a). These differences originate from the fundamentally distinct charge-transfer mechanisms of the two electrode types. Pt electrodes rely mainly on non-Faradaic processes (charging/discharging of the electrical double layer), where no redox reaction or direct ion transfer occurs at the electrode interface. As a result, a substantial fraction of the applied transmembrane voltage is consumed in overcoming interfacial capacitance, leaving a relatively weak effective electric field to drive ion migration. In contrast, Ag/AgCl electrodes operate via a reversible Faradaic process (AgCl + e– ⇌ Ag + Cl–), which directly couples charge transfer to Cl– ions. This mechanism enables more efficient charge transport across the interface and generates stronger ionic driving forces under the same applied voltage, thereby benefiting both ion flux and selectivity. Under a positive electric field, K⁺ transport is favored due to its lower energy barrier, while ions with higher hydration energies, such as Mg2+, are effectively suppressed. By contrast, passive dialysis primarily facilitates Cl– transport, with Mg2+ migration occurring only to maintain charge neutrality, consistent with the observed negative OCV (Supplementary Fig. 40). In the redox-mediated system, Cl– is released at the receiving electrode and consumed at the feed electrode through the Ag/AgCl redox couple, significantly enhancing Cl–/SO42– selectivity (Fig. 6a, b). At the feed side, Ag electrodes react with Cl– to form AgCl. Once the electrochemical capacity is depleted, the electrodes can be easily reversed. The Ag+/Cl– system, with its extremely low solubility product constant (\({K}_{{sp}}\) = 1.8 × 10–10)71, allows for efficient electrode regeneration and recycling. As a result, concerns about the high cost and limited capacity of Ag/AgCl electrodes are mitigated due to their reusability (Fig. 6c).

a Schematic showing concentration-driven ion transport across the COF-TFB-OMe membrane. b Schematic illustrating the combined concentration-driven and redox-driven ion transport across the membrane. c Schematic demonstrating the potential for reusing Ag/AgCl electrodes. In this process, AgCl is reduced to Ag, releasing Cl−, while the Ag electrode is oxidized to AgCl in a chloride-containing electrolyte. The electrode can be easily reused by swapping its positions.

It should be noted that the osmotic driving force diminishes as the receiving solution becomes enriched, eventually reaching equilibrium when the OCV approaches zero. Using 100 mM KCl as a reference, we prepared solutions of different concentrations according to the experimentally determined selectivity and found that, at equilibrium, the K+ concentration in the receiving phase was approximately twice that in the feed (Supplementary Fig. 41). This outcome corresponds to more than twofold enrichment, highlighting strong potential for complete KCl recovery from hypersaline brines.

Importantly, coupling the membrane process with redox reactions enables ion transport rates that not only exceed those driven by passive diffusion but also outperform commercial nanofiltration membranes such as NF-270. For instance, at 1 MPa, NF-270 delivers a Cl⁻ flux of ~3.0 mol m–2 h–1 with a Cl⁻/SO42– separation factor of 79, whereas our COF membrane achieves a comparable Cl– flux (~3.2 mol m–2 h–1) but with a much higher Cl⁻/SO42– selectivity of 33272. However, conventional nanofiltration membranes like NF-270 are generally unsuitable for treating highly saline solutions. The large osmotic pressure generated at high salt concentrations necessitates high external pressure, resulting in excessive energy consumption, severe fouling, and scaling. Moreover, their ion selectivity deteriorates under these conditions, and substantial dilution with fresh water is often required, an impractical step in freshwater-scarce regions such as salt lakes. By contrast, our electrically driven ion migration process fundamentally circumvents these limitations. Because it is not constrained by osmotic pressure, it can operate efficiently in high-salinity environments. Furthermore, unlike NF-270, which requires applied pressure and exhibits negligible cation selectivity, our system operates autonomously, without external pressure or voltage, while simultaneously achieving selective separation of both anions and cations.

Together, these advantages underscore the superior efficiency, robustness, and sustainability of this redox-mediated, energy-autonomous approach for selective KCl extraction from concentrated brine.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed an energy-autonomous system for KCl extraction by combining biomimetic 3D COF membranes with redox-mediated salinity gradient harvesting. The COF-TFB-OMe membrane, featuring sub-nanometer channels and methoxy-functionalized pore walls, demonstrates outstanding dual-ion selectivity through valence-dependent short-range interactions. This unique architecture lowers the enthalpic barrier for monovalent ions (K+, Cl⁻) while increasing the free energy barrier for polyvalent ions (Mg2+, SO42–), enabling precise ion separation even in complex brine matrices. Critically, the system leverages spontaneous Ag/AgCl redox reactions to generate an internal electric field, eliminating the need for external energy input. This self-sustained mechanism significantly boosts ion transport efficiency, delivering over a fivefold increase in fluxes relative to passive dialysis, while achieving exceptional selectivity (Cl⁻/SO42– = 332; K+/Mg2+ = 60; K+/Na+ = 7; K+/Li+ = 11). In contrast to conventional electrodialysis using Pt electrodes, which often sacrifices selectivity to boost flux under high voltages, our redox-mediated approach offers a superior balance of performance and efficiency. The key advantages of this system include: (1) osmotic energy harvesting, enabling net energy output and reducing operational costs; (2) single-step KCl separation, achieving a K+ and Cl⁻ mole fraction of up to 93.7% using simulated Atacama brine; (3) electrode recyclable, supporting long-term operational stability; and (4) high enrichment potential, enabling complete KCl extraction with more than a twofold increase in concentration from the feed solution. Overall, this work represents a significant advancement in sustainable resource recovery from hypersaline brines. By uniting bioinspired membrane design with self-sustaining electrochemical operation, our strategy provides a scalable, energy-efficient solution for extracting high-value minerals in industrial applications.

Methods

Fabrication of COF-TFB

The PAN support was vertically positioned in the center of a custom-made diffusion cell, dividing it into two chambers, each with a volume of 7 cm3. An acetic acid aqueous solution (1 M, 7 mL) containing TAM (37.2 mg, 0.098 mmol) was introduced into one compartment, while the opposite compartment was filled with a 7 mL ethyl acetate-mesitylene solution (V/V = 1/3) containing 7.44 mg (0.046 mmol) of TFB. The reaction was conducted at 35 °C for 3 days. Afterward, the membrane was thoroughly washed with methanol and ethanol to remove unreacted monomers and catalyst.

Fabrication of COF-TFB-OMe

The PAN support was vertically positioned in the center of a custom-made diffusion cell, dividing it into two chambers, each with a volume of 7 cm3. An acetic acid aqueous solution (1 M, 7 mL) containing TAM (57 mg, 0.15 mmol) was introduced into one compartment, while the opposite compartment was filled with a 7 mL ethyl acetate-mesitylene solution (V/V = 1/3) containing 5.7 mg (0.023 mmol) of TFB-OMe. The reaction was conducted at 35 °C for 3 days. Afterward, the membrane was thoroughly washed with methanol and ethanol to remove unreacted monomers and catalyst.

Fabrication of COF-TFB-OH

The PAN support was vertically positioned in the center of a custom-made diffusion cell, dividing it into two chambers, each with a volume of 7 cm3. An acetic acid aqueous solution (1 M, 7 mL) containing TAM (37.2 mg, 0.098 mmol) was introduced into one compartment, while the opposite compartment was filled with a 7 mL ethyl acetate-mesitylene solution (V/V = 1/3) containing 7.44 mg (0.035 mmol) of TFB-OH. The reaction was conducted at 35 °C for 3 days. Afterward, the membrane was thoroughly washed with methanol and ethanol to remove unreacted monomers and catalyst.

Evaluation of ion selectivity tested under dialysis conditions

Ion diffusion tests were carried out using an H-type diffusion cell. Membranes were sandwiched between two polydimethylsiloxane O-rings and sealed in the middle of the cells using clips. The effective diameter of the membrane is 18 mm. In single-salt dialysis diffusion tests, 25 mL of a salt solution was used as the feed solution, and the permeate side was filled with 25 mL of deionized water. To maintain a steady ionic strength during testing, the feed solutions were circulated using a peristaltic pump. The ion concentration of the permeate solution was recorded using a conductivity meter. The transport kinetics were reflected in the linear slope in the plot of ion concentration in the permeate chamber versus operation time. In binary or diversified ion diffusion tests, 25 mL of a salt solution containing an equimolar concentration of various compounds was used as the feed solution, and the permeate side was filled with 25 mL of deionized water. The concentrations of various ions in the permeate side were measured by ion chromatography. The concentration change of the permeate solution over time was obtained based on the linear relationship between the peak area and concentration of electrolyte solutions. A series of electrolyte solutions with various concentrations were prepared, and their peak areas were measured by ion chromatography to derive the calibration curves. After the tests, the membrane was washed with deionized water on the diffusion cell until the conductivity of the water was below 2 μS cm−1. The corresponding ion flux across the membrane was calculated from the concentration change in the permeate side,

where \(J\) (mol m–2 h–1) is the ion flux; \({C}_{t}\) (mol L–1) and \({C}_{0}\) (mol L–1) represent the ion concentration at time 0 and \(t\) (h), respectively; \(V\) (L) is the volume of solution in the permeate side; \({A}_{m}\) is the effective membrane area (m2). The selectivity (\({P}_{B}^{A}\)) of A over B was calculated using the following equation:

where \({J}_{A}\) and \({J}_{B}\) represent the respective fluxes of A and B, while \({C}_{B}\) (mol L–1) and \({C}_{A}\) (mol L–1) are the concentrations of B and A in the feed side, respectively.

Appearant activation energy measurement

The membrane was mounted between the two chambers of an H-shaped diffusion cell with an effective membrane area of 2.5 cm2. 35 mL of KCl, K2SO4, or MgCl2 solution (0.1 M) was used as the feed solution, and the permeate side was filled with 35 mL of deionized water. The permeances (P) of the permeate side at various temperatures were recorded by a conductivity meter. The ion transmission activation energies were calculated by the Arrhenius equation:

whereby \(P\), \(A\), \({E}_{a}\), \(R\), and \(T\) represent the permeance, pre-exponential factor, activation energy, gas constant, and temperature, respectively.

Permselectivity analysis by GHK model

The COF-TFB-OMe membrane was installed in the nanofluidic devices, with each chamber filled with different electrolytes to establish a concentration gradient ranging from 0.1 M to 0.01 M (based on cation concentration). The mobility ratio (\({\mu }^{+}/{\mu }^{-}\)) of cations (\({\mu }^{+}\)) to anions (\({\mu }^{-}\)) was calculated using the GHK equation:

In this equation, \({z}_{+}\) and \({z}_{-}\) represent the valences of cations and anions, respectively; \({E}_{{diff}}\) is the voltage at zero current, \(F\) is the Faraday constant, \(T\) is the absolute temperature, \(\Delta\) represents the concentration gradient, here 10, and \(R\) is the universal gas constant.

Electro-driven ion permeation test

Electro-driven ion permeation tests were conducted at an input voltage of −1 V, applied across Pt electrodes, using an H-type diffusion cell. The feed chamber was filled with 25 mL of a solution containing KCl, MgCl2, and K2SO4 (each at 0.1 M), while the other chamber was filled with 25 mL of deionized water. To maintain a constant ionic strength throughout the testing, the feed solutions were circulated using a peristaltic pump. Ion concentrations in the permeated chamber were subsequently analyzed using ion chromatography.

Redox-mediated, energy-autonomous KCl extraction from brine

The test was conducted using a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes in the H-type diffusion cell.The feed chamber was filled with 25 mL of artificial salt lake containing NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, LiCl and K2SO4, while the opposite chamber was filled with 25 mL of KCl solution with concentrations gradually increasing (0, 1, 10, 100, 1000 mM). To maintain a constant ionic strength throughout the experiment, the feed solutions were circulated using a peristaltic pump. Ion concentrations in the permeated chamber were then analyzed using ion chromatography.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplemental Information. Additional data related to this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Brownlie, W. J. et al. Global food security threatened by potassium neglect. Nat. Food 5, 111–115 (2024).

Liu, G. & Martinoia, E. How to survive on low potassium. Nat. Plants 6, 332–333 (2020).

Türk, T. & Kangal, M. Extraction of KCl from potassium feldspar by various inorganic salts. Minerals 13, 1342 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Research status and development trends of inorganic salt lake resource extraction based on bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 17, 121 (2024).

Tomiyama, T., Yamaguchi, M., Shudo, Y., Kawamoto, T. & Tanaka, H. Adsorption selectivity of nickel hexacyanoferrate foam electrodes and influencing factors: extraction of a 98% potassium fraction solution from pseudo-seawater. Water Res. 283, 123796 (2025).

Zhao, X. et al. Enhanced hybrid capacitive performance for efficient and selective potassium extraction from wastewater: Insights from regulating electrode potential. Water Res. 281, 123570 (2025).

Zhou, Y., Hu, C., Liu, H. & Qu, J. Potassium-ion recovery with a polypyrrole membrane electrode in novel redox transistor electrodialysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 4592–4600 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Aromatic-aliphatic hydrocarbon separation with oriented monolayer polyhedral membrane. Science 386, 1037–1042 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Bioinspired hierarchical porous membrane for efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 5, 71–80 (2021).

Sengupta, B. et al. Carbon-doped metal oxide interfacial nanofilms for ultrafast and precise separation of molecules. Science 381, 1098–1104 (2023).

Ding, L. et al. Effective ion sieving with Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes for production of drinking water from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 3, 296–302 (2020).

Shen, J. et al. Fast water transport and molecular sieving through ultrathin ordered conjugated-polymer-framework membranes. Nat. Mater. 21, 1183–1190 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Fluorine-rich poly(arylene amine) membranes for the separation of liquid aliphatic compounds. Science 387, 208–214 (2025).

Lee, T. H. et al. Microporous polyimine membranes for efficient separation of liquid hydrocarbon mixtures. Science 388, 839–844 (2025).

Yao, Y. et al. More resilient polyester membranes for high-performance reverse osmosis desalination. Science 384, 333–338 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Nanofiltration membranes with ultra-high negative charge density for enhanced anion sieving and removal of organic micropollutants. Nat. Water 3, 704–713 (2025).

Zuo, P. et al. Near-frictionless ion transport within triazine framework membranes. Nature 617, 299–305 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. Regulate ion transport in subnanochannel membranes by ion-pairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 17144–17151 (2025).

Mo, R.-J. et al. Regulating ion affinity and dehydration of metal-organic framework sub-nanochannels for high-precision ion separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2145 (2024).

Wang, A. et al. Selective ion transport through hydrated micropores in polymer membranes. Nature 635, 353–358 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Solvent-responsive covalent organic framework membranes for precise and tunable molecular sieving. Sci. Adv. 10, eads0260 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Sustainable polyester thin films for membrane desalination developed through interfacial catalytic polymerization. Nat. Water 3, 430–438 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Synthesis of two-dimensional ordered graphdiyne membranes for highly efficient and selective water transport. Nat. Water 3, 307–318 (2025).

Lim, Y. J., Goh, K. & Wang, R. The coming of age of water channels for separation membranes: from biological to biomimetic to synthetic. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 4537–4582 (2022).

Shi, X. et al. Selective liquid-phase molecular sieving via thin metal-organic framework membranes with topological defects. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 483–493 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Controllable ion transport by surface-charged graphene oxide membrane. Nat. Commun. 10, 1253 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Covalent organic framework membranes for efficient separation of monovalent cations. Nat. Commun. 13, 7123 (2022).

Guo, B.-B. et al. Double charge flips of polyamide membrane by ionic liquid-decoupled bulk and interfacial diffusion for on-demand nanofiltration. Nat. Commun. 15, 2282 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Giant blue energy harvesting in two-dimensional polymer membranes with spatially aligned charges. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310791 (2024).

Wang, G., Shao, L. & Zhang, S. Membrane-ion interactions creating dual-nanoconfined channels for superior mixed ion separations. Adv. Mater. 37, 2414898 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Advanced ion transfer materials in electro-driven membrane processes for sustainable ion-resource extraction and recovery. Prog. Mater. Sci. 128, 100958 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Solar transpiration-powered lithium extraction and storage. Science 385, 1444–1449 (2024).

Kopec, W. et al. Direct knock-on of desolvated ions governs strict ion selectivity in K+ channels. Nat. Chem. 10, 813–820 (2018).

Zhao, G. & Zhu, H. Cation-π interactions in graphene-containing systems for water treatment and beyond. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905756 (2020).

Lai, Z. et al. Covalent-organic-framework membrane with aligned dipole moieties for biomimetic regulable ion transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2409356 (2024).

Wang, D.-X. & Wang, M.-X. Exploring anion-π interactions and their applications in supramolecular chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1364–1380 (2020).

Yin, S. et al. Giant gateable thermoelectric conversion by tuning the ion linkage interactions in covalent organic framework membranes. Nat. Commun. 15, 8137 (2024).

Sippel, K. H. & Quiocho, F. A. Ion-dipole interactions and their functions in proteins. Protein Sci. 24, 1040–1046 (2015).

Burke, D. W., Jiang, Z., Livingston, A. G. & Dichtel, W. R. 2D covalent organic framework membranes for liquid-phase molecular separations: state of the field, common pitfalls, and future opportunities. Adv. Mater. 36, 2300525 (2024).

Liu, X., Liu, P., Wang, H. & Khashab, N. M. Advanced microporous framework membranes for sustainable separation. Adv. Mater. 37, 2500310 (2025).

Xian, W., Wu, D., Lai, Z., Wang, S. & Sun, Q. Advancing ion separation: covalent-organic-framework membranes for sustainable energy and water applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 1973–1984 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Covalent organic framework membranes for energy storage and conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 5675–5739 (2025).

Zhao, X., Pachfule, P. & Thomas, A. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for electrochemical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6871–6913 (2021).

Geng, K. et al. Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 120, 8814–8933 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Engineering covalent organic framework membranes for efficient ionic/molecular separations. Matter 7, 1406–1439 (2024).

Knebel, A. & Caro, J. Metal-organic frameworks and covalent organic frameworks as disruptive membrane materials for energy-efficient gas separation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 911–923 (2022).

Diercks, C. S. & Yaghi, O. M. The atom, the molecule, and the covalent organic framework. Science 355, eaal1585 (2017).

Jiang, W. et al. Axial alignment of covalent organic framework membranes for giant osmotic energy harvesting. Nat. Sustain. 8, 446–455 (2025).

Liu, Q. et al. Covalent organic framework membranes with vertically aligned nanorods for efficient separation of rare metal ions. Nat. Commun. 15, 9221 (2024).

Han, J. et al. Fast growth of single-crystal covalent organic frameworks for laboratory X-ray diffraction. Science 383, 1014–1019 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. Free-standing homochiral 2D monolayers by exfoliation of molecular crystals. Nature 602, 606–611 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. High-capacity uranium extraction from seawater through constructing synergistic multiple dynamic bonds. Nat. Water 3, 89–98 (2025).

Zhao, S. et al. Hydrophilicity gradient in covalent organic frameworks for membrane distillation. Nat. Mater. 20, 1551–1558 (2021).

Liu, X., Lin, W., Bader Al Mohawes, K. & Khashab, N. M. Ultrahigh proton selectivity by assembled cationic covalent organic framework nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202419034 (2025).

Hu, Y. et al. Molecular recognition with resolution below 0.2 angstroms through thermoregulatory oscillations in covalent organic frameworks. Science 384, 1441–1447 (2024).

Hong, S. et al. Precision ion separation via self-assembled channels. Nat. Commun. 15, 3160 (2024).

Bao, S. et al. Randomly oriented covalent organic framework membrane for selective Li+ sieving from other ions. Nat. Commun. 16, 3896 (2025).

Kandambeth, S. et al. Selective molecular sieving in self-standing porous covalent-organic-framework membranes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603945 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Self-standing and flexible covalent organic framework (COF) membranes for molecular separation. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1110 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Synthesis of crystalline two-dimensional conjugated polymers through irreversible chemistry under mild conditions. Nat. Commun. 16, 2336 (2025).

Meng, Q.-W. et al. Optimizing selectivity via membrane molecular packing manipulation for simultaneous cation and anion screening. Sci. Adv. 10, eado8658 (2024).

Koner, K. et al. Enhancing the crystallinity of keto-enamine-linked covalent organic frameworks through an in situ protection-deprotection strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316873 (2024).

Liu, M.-L. et al. Microporous membrane with ionized sub-nanochannels enabling highly selective monovalent and divalent anion separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 7271 (2024).

Zhao, C. et al. Unlocking direct lithium extraction in harsh conditions through thiol-functionalized metal-organic framework subnanofluidic membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14058–14066 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Intrapore energy barriers govern ion transport and selectivity of desalination membranes. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd9045 (2020).

Lu, C. et al. Dehydration-enhanced ion-pore interactions dominate anion transport and selectivity in nanochannels. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf8412 (2023).

Zou, S., Fang, L., Shen, S., Tan, Q. & Cheng, S. Resources situation and process research on potassium extraction in typical sulphate-type salt lakes at home and abroad. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 5, 113–118 (2017).

Yang, J. et al. Advancing osmotic power generation by covalent organic framework monolayer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 622–628 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Spontaneous lithium extraction and enrichment from brine with net energy output driven by counter-ion gradients. Nat. Water 2, 1091–1101 (2024).

Liu, P., Kong, X.-Y., Jiang, L. & Wen, L. Ion transport in nanofluidics under external fields. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 2972–3001 (2024).

Tackett, S. L. Potentiometric determination of solubility product constants: a laboratory experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 46, 867 (1969).

Yuan, B. et al. Self-assembled dendrimer polyamide nanofilms with enhanced effective pore area for ion separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 471 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFB3815700 and 2022YFA1503004, Q.S.), the National Science Foundation of China (22421004, Q.S.), and the National Science Foundation of Zhejiang province (LR23B060001, Q.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.S. conceived and designed the research. Q.G., Z.L., and J.Y. performed the synthesis and separation experiments. H.G., Z.X., and L.Z. carried out the computational simulations. S.W. created numerous schematic illustrations and visualized several scientific concepts. S.M. provided critical suggestions. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexander Knebel, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Q., Guo, H., Xing, Z. et al. Energy-autonomous KCl extraction from brine via biomimetic covalent-organic-framework membranes and redox-driven ion transport. Nat Commun 16, 11483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66345-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66345-z