Abstract

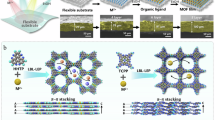

Widespread deployment of NH3-adsorbing MOF materials remains challenging due to the significant energy-penalty of regeneration. In this work, we address this limitation by integrating photothermal technologies into a bipyridinium-functionalized MOF matrix, enabling effective NH3 desorption in a more eco-friendly and sustainable manner. This MOF adsorbent exhibits selective NH3 capture via specific hydrogen bonding interactions, rendering it suitable for purifying effluent gases in industrial NH3 synthesis. The NH3 adsorption process is accompanied by an obvious color change due to the formation of bipyridinium radicals through an electron transfer reaction between NH3 molecules and bipyridinium ligands. This distinctive property endows the MOF with favorable NH3 detection capabilities. Furthermore, the colored MOF matrix functions as an exceptional photothermal medium under 808 nm laser irradiation, effectively facilitating the release of captured NH3 molecules through light-triggered localized heating. Importantly, the synthesis of this MOF material can be scaled up to gram-level with minimal complexity using a straightforward one-pot reflux method, significantly enhancing its practical applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) constitutes a crucial industrial and agricultural resource, with over 150 million tonnes manufactured globally each year. It has been prevalently found in refrigerant gases, pesticides, plastics, and other chemical substances1,2,3. Nevertheless, NH3 is a colorless gas with high toxicity and corrosiveness, capable of inducing ocular irritation and upper respiratory tract infections even at very low concentrations. Consequently, the selective capture, storage and detection of NH3 are of paramount significance for environmental and health considerations4,5,6.

As a revolutionary class of crystalline porous materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are distinguished by their highly customizable designs7,8,9. The reticular architecture of MOFs with functionalized organic linkers provides plenty of possibilities for fine-tuning their molecular-level interactions with target guest molecules. This versatility has spurred researchers to investigate MOFs as innovative adsorbents capable of capturing a wide array of toxic substances. Although significant progress has been made in enhancing the adsorption capacity and selective separation capabilities of MOF-based NH3 adsorbents10,11,12, there has been relatively less focus on achieving efficient desorption with minimal energy expenditure. Typically, adsorbents with high adsorption capacities generally demonstrate strong interactions with the NH3 molecule. Consequently, the desorption temperature is often elevated (typically ranging from 150 to 250 °C under vacuum)13,14, which makes the adsorption-desorption recycling process both energy-intensive and incompatible with mild conditions. In this context, simultaneously achieving high adsorption capacity and developing a more sustainable desorption process remains a challenge but is urgently needed.

Photothermal conversion represents a direct strategy to harnessing solar energy by transforming photon energy into heat15,16,17. The integration of photothermal performance with MOF materials offers an attractive opportunity to promote NH3 desorption process with low energy consumption. Upon exposure to light, the localized heat generated by photothermal centers can trigger the release of adsorbed NH3 molecules by disrupting their binding interactions. However, the majority of currently reported photothermal MOF adsorbents rely on exogenous photothermal species such as metal nanoparticles and redox graphene18,19. The uneven distribution of these photothermal species in the MOF composites often leads to suboptimal desorption efficiency. Therefore, advancing a strategy to design MOF adsorbents with enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency and rapid temperature rise will significantly improve complete NH3 release capabilities.

In this work, we present a neoteric NH3-adsorbing MOF material ([Zn(Bpybc)(NDC)]·0.5DMF·3H2O, Zn-Bipy) synthesized using the benzenedicarboxyl-functionalized bipyridinium ligand (1,1ʼ-bis(4-carboxybenzyl)−4,4ʼ-bipyridinium dichloride, H2BpybcCl2) and 1,4-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid (H2NDC). It is found that Zn-Bipy can effectively capture NH3 molecules within its uncoordinated carboxylate O atom-decorated pore structure through hydrogen bonding interactions. Such hydrogen bond-dominated adsorption behavior grants Zn-Bipy marked selectivity over other gas molecules like H2 and N2 at room temperature. This property enhances its potential for purifying effluent gases in industrial NH3 synthesis, leading to a lower NH3 equilibrium concentration and thereby increasing the conversion yield. Significantly, this adsorption process is accompanied by an obvious color evolvement due to the redox property of the bipyridinium ligand, in which radical species are formed through electron transfer reaction with NH3 molecules. Such a vapochromic characteristic endows the MOF material with distinctive NH3 detection capabilities, whether in crystalline or membrane form, with a rapid response time of just 1 second and a low detection limit of 1.05 ppm. The desired stability and near-infrared (NIR) absorption of the bipyridinium radicals generated within this colored MOF matrix contribute to its high photothermal performance, with a top-tier conversion efficiency of 80.75%. This enables effective NH3 release via light-triggered localized heating (Fig. 1), outperforming traditional thermal desorption in terms of sustainability and environmental friendliness. More importantly, this MOF material can be facilely prepared on a large scale (˃10 g) using a one-pot reflux process, positioning it as a compelling candidate for real-world applications.

Results

Synthesis and structural characterization

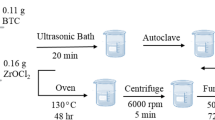

Unlike the traditional synthesis methods for MOF materials, such as the solvothermal and diffusion methods20, Zn-Bipy can be readily obtained through a large-scale reflux procedure (Fig. 2a). Subsequent to filtration, approximately 10 g of the product can be directly procured in a single batch without requiring further purification (Fig. 2b, note: the potential for further amplification by increasing the quantities of raw materials is not limited). Optical and scanning electron microscope (SEM) images disclose that the crystals generated by this approach are smaller in size and present a distinct block-shaped morphology, in contrast to the rod-shaped crystals on the millimeter scale synthesized through the solvothermal method (Supplementary Fig. 1). The high crystallinity and phase purity of these crystals are substantiated by the powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern (Fig. 2c), which aligns closely with the simulated one derived from single crystal diffraction data (Supplementary Table 1). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) are consistent with those of samples produced using the solvothermal method, indicating a highly consistent molecular structure across different synthesis scales (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Even more importantly, the filtered solvent could be directly recycled and fully utilized for at least three times, while still maintaining a comparable yield (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast to the solvothermal route, this reflux method presents a faster, more environmentally favorable, and less intense reaction technique, doing away with the necessity for autoclaves and high-pressure reactions, and thereby indicating a promising perspective for industrial manufacturing.

a Reflux synthesis procedure for Zn-Bipy. b Large-scale production of Zn-Bipy within a single reaction vessel, yielding approximately 10 g of Zn-Bipy product. c PXRD patterns of Zn-Bipy subjected to various treatments: thermal treatment at 200 °C, immersion in boiling water for 24 hours, and synthesized via a scaled-up reflux method. Note that small variations in the relative intensities of diffraction peaks occur due to the effect of crystal orientation. d One-dimensional porous channels of Zn-Bipy as observed along the c-axis. e CO2 adsorption isotherm of Zn-Bipy at 195 K. Insert: pore size distribution plot calculated by NLDFT.

Zn-Bipy displays a two-dimensional (2D) layered architecture featuring a well-defined porous structure with a pore size of ~4.3 Å along the c-axis (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 5), which matches NH3ʼs kinetic diameter of ~2.6 Å in width. The pore walls are decorated with numerous uncoordinated carboxylate O atoms derived from the organic ligands, which are oriented towards the channelʼs interior. The permanent porosity of Zn-Bipy was validated through the CO2 adsorption isotherm at 195 K, which yielded an apparent pore volume of 0.0729 cm3 g⁻1 and a Brunauer- Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of 170.4 m2 g-1 (Fig. 2e). The nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) pore size distribution of Zn-Bipy peaks around 0.3-0.6 nm (insert of Fig. 2e), consistent with the theoretical value from the crystal structure. Benefiting from the absence of water molecules in the coordination environment, Zn-Bipy exhibits exceptional thermal stability, maintaining its structural integrity at temperatures up to 200 °C (Fig. 2c). Moreover, the hydrophobic protection conferred by naphthalene rings surrounding the Zn2+ coordination sites also endows Zn-Bipy desired tolerance to demanding aqueous environments (Supplementary Fig. 6)21,22,23, including exposure to aqueous solutions spanning a wide pH range (3-11) for 24 hours, immersion in boiling water for 24 hours, and prolonged air exposure for 4 weeks (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Figs. 7, 8 and Table 2).

Selective NH3 capture with distinct vapochromic response

Leveraging the potential hydrogen bonding sites provided by the uncoordinated carboxylate O atoms on the pore wall, Zn-Bipy showcases a favorable NH3 adsorption performance, achieving a capacity of 9.67 mmol g-1 (236.97 cm3 g-1) at 25 °C and 1.0 bar (Fig. 3a). Zn-Bipy maintained its crystallinity following NH3 adsorption measurement, as evidenced by the unchanged PXRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 9). The formation of hydrogen bonds between the uncoordinated carboxylate O atom and NH3 is substantiated by the broadened and red-shifted asymmetric stretching peak of the carboxylate group at ~1554 cm-1, in contrast to its position ( ~1567 cm-1) in the original Zn-Bipy spectrum (Fig. 3b)24. The newly formed peak appearing at ~1173 cm-1 after adsorption is indicative of the bending vibration of the N-H bond in the adsorbed NH3 molecule. The isosteric heat (Qst) of NH3 was calculated using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation from the adsorption isotherms at different temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 10). For NH3 in Zn-Bipy, the Qst is moderate, with a value of approximately 24.5 kJ mol-1 at the onset of adsorption (Fig. 3c), which is comparable to some renowned porous materials where hydrogen bond serves as the main interaction, such as cis-HNU38-COF (22.4 kJ mol-1)25.

a NH3, N2 and H2 adsorption isotherms of Zn-Bipy at 25.0 °C. b FT-IR spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. The peak at ~1657 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the amide group within DMF molecules in Zn-Bipy. c Isosteric heat of NH3 adsorption (Qst) for Zn-Bipy. d Optimized structure of the NH3 molecule adsorbed on the uncoordinated carboxylate O site of NDC2- ligand determined through DFT calculations. e Optimized structure of the NH3 molecule adsorbed on the uncoordinated carboxylate O site of Bpybc ligand determined through DFT calculations. f Calculated adsorption energy for these two configurations. g Comparison of specific surface area-normalized NH3 uptake with some representative MOF adsorbents in literature. Corresponding values are provided in Supplementary Table 3. h Breakthrough curves of NH3/N2/H2 (3%:24%:73%, v/v) mixture using Zn-Bipy adsorbent at 25.0 °C. i NH3/H2 and NH3/N2 IAST selectivity of Zn-Bipy at 25.0 °C.

To visualize and structurally comprehend the accommodation details of NH3 molecules, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were executed within the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP). Through a meticulous site-by-site search, the optimal adsorption sites were identified. The calculated structural data elucidated that two of these uncoordinated carboxylate O atoms engage with NH3 molecules through O···H-N hydrogen bonds, featuring O···H distances of 1.82 (Fig. 3d) and 1.71 Å (Fig. 3e), respectively. As depicted in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 11, both the uncoordinated carboxylate O sites exhibit static adsorption energies (Eads) of −0.11 and −0.40 eV, respectively. These negative Eads values emphasize the advantageous binding characteristics of these sites compared to aromatic or alkyl hydrogen sites exhibiting positive Eads values. These findings align well with the formation of hydrogen bonds observed in FT-IR analyses. It is noted that Zn-Bipy exhibits a specific surface area-normalized NH3 uptake of 567.49 mmol cm-2, surpassing some prominent MOF adsorbents reported to date (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Table 3) and ranking second only to the prior benchmark material (LiCl@MIL-53-(OH)2-43.4)13. This highlights the efficacy of carboxylate groups as robust adsorbent sites, offering a metal-free alternative for NH3 capture materials.

The distinct hydrogen bond-dominated adsorption behavior of Zn-Bipy motivated us to explore its potential for purifying effluent gases (H2 and N2) in industrial NH3 synthesis. Even after low-temperature condensation, these streams typically retain around 1–3% NH3. Generally, a lower NH3 concentration at the converter inlet increases the driving force (e.g., the deviation from equilibrium) and therefore boosts the conversion. Zn-Bipy exhibited only trace adsorption of N2 and H2, with uptake capacities of 2.38 cm3 g−1 and 0.40 cm3 g−1 at 25 °C and 1.0 bar, respectively (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 12). Breakthrough studies using a packed column of activated Zn-Bipy under a flow (20 mL min−1) of a ternary NH3/N2/H2 mixture (3%:24%:73%, v/v) at 25 °C clearly demonstrated Zn-Bipyʼs effectiveness in separating this mixture: N2 and H2 eluted immediately, while NH3 was retained for nearly 80 min per gram of adsorbent (Fig. 3h). In addition, Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST) modeling, achieved by fitting isotherms to the dual site Langmuir equation with excellent accuracy (Supplementary Fig. 13), further demonstrated Zn-Bipy’s ability to capture trace NH3 from bulk H2 or N2 streams, as both NH3/H2 and NH3/N2 selectivities increase when the partial pressure or concentration of NH3 decreases in binary mixtures (Fig. 3i)26,27.

Zn-Bipy undergoes a conspicuous color transformation, transitioning from yellow to brown upon NH3 adsorption (denoted as Zn-Bipy-NH3, inset of Fig. 4a). The colored sample exhibits a prominent single-line signal at g = 2.0037 in the electron spin resonance (ESR) spectrum, thereby prompting speculation about the formation of bipyridinium radicals (Fig. 4a)28,29,30. Additional confirmatory evidence for the generation of bipyridinium radicals is provided by the characteristic UV-Vis absorption band that spans both the visible and NIR regions (400–900 nm, Fig. 4b)31,32,33,34. The likelihood of sunlight or vacuum-induced radical formation can be ruled out based on the undetectable ESR signal in the control experiments (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15). Taking into account the redox nature of the bipyridinium moiety of Zn-Bipy, an electron transfer reaction with NH3 molecule is proposed during the adsorption process35,36. Further evidence can be discerned from Raman spectroscopy. After NH3 adsorption, the C=N bond stretching vibration of the bipyridinium moiety at approximately 1645 cm−1 becomes more pronounced, while the pyridine ring stretching vibration at around 1610 cm−1 diminishes significantly (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the stretching modes of the C (pyridine)-C (pyridine) (~1296 cm−1) and the benzylidene skeletal C-C bond (~1173 cm−1) within the bipyridinium moiety are also enhanced. These observations further corroborate the attack of NH3 on the bipyridinium moiety37,38, which initiates an electron transfer reaction leading to the formation of bipyridinium radicals. The radical concentration in Zn-Bipy-NH3 reaches ~0.37%, as determined by ESR spectroscopy using 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPOL) as a standard39.

a ESR spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. Insert: photographs of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. b Solid UV–Vis absorption spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. c Raman spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. d N 1s core-level spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. e O 1s core-level spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption. f Zn 2p core-level spectra of Zn-Bipy pre- and post-NH3 adsorption.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis provides additional evidence supporting the occurrence of electron transfer reaction and hydrogen bond formation between Zn-Bipy and NH3 molecules during the adsorption process. In the native Zn-Bipy sample, the N 1s core-level spectrum can be deconvoluted into two peaks at 400.0 and 401.9 eV, corresponding to the N atoms in DMF and the bipyridinium group, respectively (Fig. 4d). For Zn-Bipy-NH3, the peak of the N atom in the DMF molecule at 400.0 eV is absent, suggesting the complete removal of DMF during the activation process (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). Simultaneously, two new peaks arise at 398.9 and 399.7 eV, which can be attributed to the bipyridinium N radical and NH3 molecule, respectively40,41. No detectable signal is observed for the oxidation product of NH3 molecule, which could be attributed to its low molecular weight or volatile nature, such as N242. Regarding the O 1 s core-level spectrum after NH3 adsorption, the peak of the carboxylate O atom presents a clear shift toward the higher binding energy, from 530.9 to 531.2 eV (Fig. 4e). This shift aligns with the decreased electron density following hydrogen bond formation. Conversely, the core-level spectra of Zn 2p remain unaltered before and after NH3 adsorption (Fig. 4f), suggesting that Zn2+ cations do not significantly contribute to the interaction process. This observation is consistent with the absence of a Zn-N bond signal around 420 cm-1 in the FT-IR spectrum (Fig. 3b). DFT results indicate that NH3 molecules are initially anchored via hydrogen bonds (O···H-N) to the uncoordinated carboxylate O atoms, thereby creating additional binding sites for newly arriving NH3 molecules through H···N-H interactions. While carboxylate O-anchored NH3 molecules remain distant from bipyridinium sites, later-adsorbed NH3 molecules can reside adjacent to the bipyridinium moiety, thus acting as electron donors to facilitate transfer. In addition, NH3 gas molecules in the vicinity directly contact surface bipyridinium moieties, inducing immediate electron transfer.

Colorimetric NH3 detection

The vapochromic characteristics enable Zn-Bipy to have high-performance applications in colorimetric NH3 detection. The color change of Zn-Bipy is rapidly perceptible within a mere second upon exposure to an NH3 atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 18). The Zn-Bipy’s sensing capabilities are further demonstrated through the limit of detection (LOD) calculation using a vapochromic assay based on the Stern-Volmer equation43,44. The linear regression (slope = 0.00273 ppm−1, R2 = 0.9883) highlights its favorable sensitivity towards NH3 detection, with a very low LOD value of 1.05 ppm (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 19). Such LOD value is significantly lower than the immediately dangerous to life or health concentration (IDLH, 300 ppm)45. The NH3-sensing samples can be restored to their original state by refluxing in the mixed DMF and H2O solvent at 105 °C under an O2 atmosphere, as confirmed by various analytical techniques (Supplementary Figs. 18, 20–24). The observed reversibility in the transformation is likely explained by dynamic exchange of NH3 molecules within the pore structure by solvent molecules (DMF and H2O), along with the quenching effect of O2 on the bipyridinium radical46,47,48. Importantly, the NH3-induced chromic switching between the two states demonstrates high stability, maintaining its efficacy for at least four cycles without any significant deterioration in the UV-Vis absorption intensity (Fig. 5b).

a Linear relationship between the increased UV-Vis absorption intensity at 400 nm and concentration of NH3 atmosphere. Insert table: fitting result of UV-Vis absorption intensity at 400 nm as a function of NH3 concentration. b The cyclic colorimetric detection process of Zn-Bipy monitored via the UV-Vis absorption intensity at 400 nm. c SEM image of the cross-section of the Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane. d Visual representation of the Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane. e Visual representation of the Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane under exposure to an NH3 atmosphere. f Flexibility description of the Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane after NH3 exposure (scale bar: 1.0 cm).

Significantly, Zn-Bipy can be further processed to form a paper-like membrane by employing polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) as the underlying substrate, facilitating user-friendly and practical NH3 detection (Supplementary Fig. 25). The resulting Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane exhibited uniform macroscopic integrity, featuring a smooth surface and exceptional flexibility (Supplementary Figs. 26, 27). As depicted in the low magnification SEM image (Supplementary Fig. 28), the membrane surface is adorned with Zn-Bipy particles, each measuring less than 1 μm, which substantially increases the specific surface area available for NH3 interaction compared to the bulk material. The Zn-Bipy layer and the PTFE substrate have measured thicknesses of approximately 40 and 100 μm, respectively (Fig. 5c). The membraneʼs initial color is yellow (Fig. 5d), and upon exposure to a laboratory-scale NH3 atmosphere (details of which are provided in the Supplementary Information), an immediate and distinct color transformation to light brown was observed within seconds (Fig. 5e). Moreover, the membrane exhibited no deterioration in its flexibility and could still be completely folded in half after the experiment, as clearly shown in the images (Fig. 5f).

Photothermal conversion-assisted NH3 release

The NH3-induced bipyridinium radicals exhibit high air stability for at least 1 week, as confirmed by the retained characteristic UV–Vis absorption peak and ESR signal (Supplementary Fig. 29). Such desired stability and NIR absorption make Zn-Bipy-NH3 highly promising in photothermal conversion upon exposure to 808 nm laser irradiation (0.8 W cm−2). As depicted in Fig. 6a, b, the photothermal temperature of the Zn-Bipy-NH3 powder rapidly increased to a maximum of approximate 110 °C within 5 seconds, and then entered a quasi-steady state (~121 °C). In contrast, under the same irradiation conditions, no obvious temperature increase was observed in Zn-Bipy due to its lack of significant absorption in the NIR region (Supplementary Fig. 30). The photothermal performance of Zn-Bipy-NH3 demonstrates exceptional temperature durability, capable of being repeated for at least six cycles without any noticeable degradation in either the temperature output or the radical signals as observed in the UV-Vis absorption and ESR spectra (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs. 31, 32). The framework structure of Zn-Bipy-NH3 remains intact following photothermal measurement (Supplementary Fig. 33). Moreover, the photothermal temperature of Zn-Bipy-NH3 is linearly dependent on the laser power, indicating exceptional thermal control performance (Supplementary Fig. 34). The absence of luminescence emission from Zn-Bipy-NH3 under 808 nm laser irradiation confirms the predominance of non-radiative transition in this photothermal conversion process (Supplementary Fig. 35). Based on the cooling curve, the photothermal conversion efficiency (η) of Zn-Bipy-NH3 is calculated to be 80.75% (Supplementary Fig. 36), exhibiting superior performance compared to other reported crystalline framework materials (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Table 4). This high conversion efficiency can be reasonably ascribed to the relatively low thermal conductivity arising from the combination of the organic linkers and metal nodes in the structure49,50,51, along with the absence of radiative transition under 808 nm laser irradiation.

a Photothermal images of a heart-shaped pattern formed by Zn-Bipy-NH3 powder under 808 nm laser irradiation. b Photothermal conversion curves of Zn-Bipy and Zn-Bipy-NH3 powders under 808 nm laser irradiation. c Photothermal cycling curves of Zn-Bipy-NH3 powder under 808 nm laser irradiation. d Comparative analysis of photothermal conversion efficiency between Zn-Bipy-NH3 and other MOF materials. Corresponding values are provided in Supplementary Table 4. e Comparison of residual NH3 amount under different conditions: vacuum environment at ambient temperature (blue) and vacuum environment with 808 nm laser irradiation (red). The error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent measurements. f NH3 desorption efficiency under vacuum environment at different photothermal temperatures. The error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent measurements. g Cycles of NH3 adsorption at 25.0 °C.

The localized heating generated by photothermal conversion can enhance the release of adsorbed NH3 molecules by disrupting hydrogen bonding interactions. As illustrated in Fig. 6e, the adsorbed NH3 molecules achieve a desorption efficiency of approximately 59.2% after just 30 min in a vacuum under 808 nm laser irradiation (photothermal temperature: ~150 °C, Supplementary Fig. 37). After 2 h of irradiation, the desorption efficiency exceeded 97%. Conversely, without 808 nm laser irradiation under the same conditions, the desorption efficiency was only 53.7% after 2 h. When the photothermal temperature diminishes, desorption efficiency likewise declines (Fig. 6f), which further underscores the pivotal role of photothermal conversion in expediting the release of NH3 molecules. By employing the photothermal-assisted desorption process, the adsorption behavior can be successfully repeated for at least six cycles without any noticeable reduction in uptake (Fig. 6g). Compared to visible light, NIR irradiation offers superior penetration depth52,53, thereby endowing this desorption technique with greater practicality in complex environments containing translucent barriers. Previous studies have demonstrated that porous materials used for NH3 adsorption often face challenging desorption conditions, typically necessitating elevated temperatures (e.g., 150–250 °C) to overcome the strong affinity interactions. In this context, the present work introduces a more advanced, sustainable desorption strategy with wireless remote control.

Discussion

We have convincingly demonstrated the sophisticated NH3 capture and low-energy desorption capabilities of a bipyridinium-functionalized MOF material, which can be scaled up to gram quantities (˃10 g) using an easy-operating one-pot reflux method. By harnessing the uncoordinated carboxylate O atoms within the pore wall of the organic ligands, this MOF adsorbent effectively captures a substantial amount of NH3 molecules through hydrogen bonding interactions. Facilitated by such bonding, Zn-Bipy exhibits pronounced adsorption selectivity over other gases like H2 and N2, thereby enhancing its utility for effluent stream purification in industrial NH3 synthesis at room temperature. The redox nature of the bipyridinium ligand leads to an observable color change during the adsorption process, as radical species are formed from electron transfer reaction with NH3 molecule. This vapochromic behavior endows the MOF adsorbent with high-performance NH3 detection capabilities, whether in crystalline or membrane form, characterized by a fast response time and an exceptionally low detection limit. The favorable stability and NIR absorption of the generated bipyridinium radicals confer high photothermal conversion on this colored MOF matrix under 808 nm laser irradiation, facilitating effective NH3 desorption through localized heat. With its practical synthetic feasibility and performance metrics, this MOF material stands out as a rare example with significant potential for real-world application in cutting-edge NH3 adsorption and detection technologies.

Methods

Synthesis of H2BpybcCl2 ligand

The synthesis of H2BpybcCl2 ligand was conducted according to a previous method54. A typical synthesis process proceeds as follows: 4,4′-bipyridine (0.31 g, 2 mmol) and 4-(chloromethyl)benzoic acid (0.85 g, 5 mmol) are dissolved in 20 mL DMF. The solution is degassed with nitrogen gas for 10 min and then stirred at 110 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere for 24 h. After the reaction is complete, the mixture is filtered to collect the solid product. The solid residue is washed with DMF and dried under vacuum overnight, yielding H2BpybcCl2 as a white powder. 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz, Supplementary Fig. 38): δ 9.20 ppm (d, 4H), δ 8.58 ppm (d, 4H), δ 8.07 ppm (d, 4H), δ 7.60 ppm (d, 4H), δ 6.03 ppm (s, 4H).

Synthesis of Zn-Bipy (solvothermal method)

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.059 g, 0.20 mmol), H2BpybcCl2 (0.114 g, 0.23 mmol), and H2NDC (0.043 g, 0.20 mmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of DMF (5 mL) and H2O (5 mL), and then sealed in a Teflon-lined stainless steel vessel after stirring for 10 min. The vessel was heated at 110 °C for 24 h. After slowly cooling down to room temperature, yellow block-shaped crystals were obtained.

Synthesis of Zn-Bipy (reflux method)

In a 500 mL round-bottom flask, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (4.57 g, 15.48 mmol), H2BpybcCl2 (8.21 g, 17.8 mmol), and H2NDC (3.33 g, 15.48 mmol) were added to the mixed solvent (300 mL, with a volume ratio of VH₂O:VDMF = 1:1) under vigorous magnetic stirring. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was refluxed at 110 °C for a period of 3 h. After cooling to room temperature, the yellow precipitate was filtered to separate it from the liquid. Then, the precipitate was centrifuged along with the residual solvents. After being left in the air overnight, a pale-yellow crystalline product (~10.07 g) was obtained.

Synthesis of Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane

Zn-Bipy/PTFE membrane was fabricated via a straightforward surface coating approach. In this method, 90 wt% of ball-milled Zn-Bipy and 10 wt% polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were blended in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP). Subsequently, the mixture was cast onto a commercial PTFE membrane (with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a pore size of 0.45 μm), and then dried in the air for 12 h.

Regeneration protocol of NH3-sensing samples

The NH3-sensing samples (powder, 100 mg) can be transformed back to the initial state through a refluxing process in a solvent mixture of DMF (6 mL) and H2O (6 mL). The reflux reaction is carried out at 105 °C with stirring for 12 h in an O2 atmosphere. After being cooled to room temperature, the suspension is filtered. The resultant product is then air-dried for 12 h, resulting in a pale-yellow powder as the final product.

Data availability

The main data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. The fitting results in Supplementary Fig. 13 were derived from the adsorption data at 25 °C using IAST++ software55. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fu, X. et al. Calcium-mediated nitrogen reduction for electrochemical ammonia synthesis. Nat. Mater. 23, 101–107 (2024).

Snyder, B. E. R. et al. A ligand insertion mechanism for cooperative NH3 capture in metal-organic frameworks. Nature 613, 287–291 (2023).

Jiang, F. et al. A straightforward solvent-pair-enabled multicomponent coassembly approach toward noble-metal-nanoparticle-decorated mesoporous tungsten oxide for trace ammonia sensing. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313547 (2024).

Song, X. et al. Self-healing hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks for low-concentration ammonia capture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 627–634 (2024).

Carné-Sánchez, A. et al. Ammonia capture in rhodium(II)-based metal-organic polyhedra via synergistic coordinative and H-bonding interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 6747–6754 (2023).

Freddi, S. et al. Chemical defect-driven response on graphene-based chemiresistors for sub-ppm ammonia detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200115 (2022).

Sengupta, D. et al. Integrated CO2 capture and conversion by a robust Cu(I)-based metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27006–27013 (2024).

Jiang, L. et al. Constructing isoreticular metal-organic frameworks by silver–carbon bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22930–22936 (2024).

Meng, L. et al. Coassembly of complementary polyhedral metal-organic framework particles into binary ordered superstructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21225–21230 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Fabrication of robust and cost-efficient Hoffmann-type MOF sensors for room temperature ammonia detection. Nat. Commun. 14, 7261 (2023).

Kim, D. W. et al. High ammonia uptake of a metal-organic framework adsorbent in a wide pressure range. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22531–22536 (2020).

Rieth, A. J. & Dincă, M. Controlled gas uptake in metal-organic frameworks with record ammonia sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3461–3466 (2018).

Shi, Y. et al. Anchoring LiCl in the nanopores of metal-organic frameworks for ultra-high uptake and selective separation of ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212032 (2022).

He, X., Gao, S., Peng, R., Zhu, D. & Yu, F. A novel topological indium-organic framework for reversible ammonia uptake under mild conditions and catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 14501–14507 (2024).

Raziq, F. et al. Isolated Ni atoms enable near-unity CH4 selectivity for photothermal CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21008–21016 (2024).

Cui, X. et al. Photothermal nanomaterials: a powerful light-to-heat converter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6891–6952 (2023).

Xiong, R. et al. Photothermal nanomaterial-mediated photoporation. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 631–643 (2023).

Zhou, P. et al. Sunlight assisted highly efficient desorption of ammonia by redox graphene hybrid metal-organic framework photothermal conversion adsorbents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 336, 126348 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Visible light triggered CO2 liberation from silver nanocrystals incorporated metal-organic frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 4815–4821 (2016).

Higuchi, M. et al. Design of flexible lewis acidic sites in porous coordination polymers by using the viologen moiety. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8369–8372 (2012).

Kubi, G. A. et al. Non-peptidic cell-penetrating motifs for mitochondrion-specific cargo delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 17183–17188 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. A copper(II)-paddlewheel metal-organic framework with exceptional hydrolytic stability and selective adsorption and detection ability of aniline in water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 27027–27035 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Polymer-metal-organic frameworks (polyMOFs) as water tolerant materials for selective carbon dioxide separations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 920–925 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Ammonia capture within zirconium metal-organic frameworks: reversible and irreversible uptake. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 20081–20093 (2021).

Tian, X. et al. Efficient capture and low energy release of NH3 by azophenol decorated photoresponsive covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202406855 (2024).

Walton, K. S. & Sholl, D. S. Predicting multicomponent adsorption: 50 years of the ideal adsorbed solution theory. AIChE J. 61, 2757–2762 (2015).

Jiang, Y. et al. Benchmark single-step ethylene purification from ternary mixtures by a customized fluorinated anion-embedded MOF. Nat. Commun. 14, 401 (2023).

van den Bersselaar, B. W. L. et al. Stimuli-responsive nanostructured viologen-siloxane materials for controllable conductivity. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312791 (2024).

Yang, X.-D. et al. Long-lived multiple charge separation by proton-coupled electron transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215591 (2023).

Sui, Q. et al. Piezochromism and hydrochromism through electron transfer: new stories for viologen materials. Chem. Sci. 8, 2758–2768 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. The green box: selenoviologen-based tetracationic cyclophane for electrochromism, host–guest interactions, and visible-light photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9118–9128 (2023).

Li, D.-H. et al. Photo-activating biomimetic polyoxomolybdate for boosting oxygen evolution in neutral electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312706 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Photo responsive electron and proton conductivity within a hydrogen-bonded organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308418 (2023).

Cai, L.-X. et al. Water-soluble redox-active cage hosting polyoxometalates for selective desulfurization catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4869–4876 (2018).

Li, L. et al. Advances in viologen-based stimulus-responsive crystalline hybrid materials. Coor. Chem. Rev. 518, 216064 (2024).

Li, S.-L. et al. X-ray and UV dual photochromism, thermochromism, electrochromism, and amine-selective chemochromism in an anderson-like Zn7 cluster-based 7-fold interpenetrated framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12663–12672 (2019).

Chen, C., Rao, H., Lin, S. & Zhang, J. A vapochromic strategy for ammonia sensing based on a bipyridinium constructed porous framework. Dalton Trans. 47, 8204–8208 (2018).

Nijem, N. et al. Tuning the gate opening pressure of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for the selective separation of hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15201–15204 (2012).

Nakayama, A., Kimata, H., Marumoto, K., Yamamoto, Y. & Yamagishi, H. Facile light-initiated radical generation from 4-substituted pyridine under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 56, 6937–6940 (2020).

Sang, Y.-F., Zeng, H., Xu, L.-J. & Chen, Z.-N. Radical hybrids with multiple responses to thermal stimuli via electron transfer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2206459 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Methylviologen-templated layered bimetal phosphate: a multifunctional X-ray-induced photochromic material. Chem. Sci. 5, 4237–4241 (2014).

Kaneko, M., Katakura, N., Harada, C., Takei, Y. & Hoshino, M. Visible light decomposition of ammonia to dinitrogen by a new visible light photocatalytic system composed of sensitizer (Ru(bpy)32+), electron mediator (methylviologen) and electron acceptor (dioxygen). Chem. Commun. 3436–3438 (2005).

Yu, X. et al. Ln-MOF-based hydrogel films with tunable luminescence and afterglow behavior for visual detection of ofloxacin and anti-counterfeiting applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311939 (2024).

Chen, C., Sun, J.-K., Zhang, Y.-J., Yang, X.-D. & Zhang, J. Flexible viologen-based porous framework showing x-ray induced photochromism with single-crystal-to-single-crystal transformation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14458–14462 (2017).

Islamoglu, T. et al. Metal-organic frameworks against toxic chemicals. Chem. Rev. 120, 8130–8160 (2020).

Huang, Y.-R. et al. Thermal-responsive polyoxometalate-metalloviologen hybrid: reversible intermolecular three-component reaction and temperature-regulated resistive switching behaviors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16911–16916 (2021).

Sun, C. et al. Design strategy for improving optical and electrical properties and stability of lead-halide semiconductors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2805–2811 (2018).

Okeyoshi, K. & Yoshida, R. Polymeric design for electron transfer in photoinduced hydrogen generation through a coil–globule transition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 7304–7307 (2019).

Lan, W. et al. The influence of light-generated radicals for highly efficient solar-thermal conversion in an ultra-stable 2D metal-organic assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401766 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Metalloligand nickel bis(dithiolene) based metal–organic frameworks for efficient photocurrent and photothermal conversion. ACS Mater. Lett. 6, 4051–4057 (2024).

Su, J. et al. Persistent radical tetrathiafulvalene-based 2D metal-organic frameworks and their application in efficient photothermal conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 4789–4795 (2021).

Han, C., Kunda, B. K., Liang, Y. & Sun, Y. Near-infrared light-driven photocatalysis with an emphasis on two-photon excitation: concepts, materials, and applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307759 (2024).

Ravetz et al. Development of a platform for near-infrared photoredox catalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 2053–2059 (2020).

Sun, Y.-Q., Zhang, J., Ju, Z.-F. & Yang, G.-Y. Two-dimensional noninterpenetrating transition metal coordination polymers with large honeycomb-like hexagonal cavities constructed from a carboxybenzyl viologen ligand. Cryst. Growth Des. 5, 1939–1943 (2005).

Lee, S., Lee, J. H. & Kim, J. User-friendly graphical user interface software for ideal adsorbed solution theory calculations. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 35, 214–221 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22171020). X.X. thanks the Basic Research Project of Qinghai Province (2024-zj-754). X.D.Y. is grateful for the support from the Henan Provincial Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities (25A150002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D.Y. and H.L. conducted most of the experiments and analyzed the data. Y.S. and W.D. assisted in data analysis. Y.W. and X.X. contributed to the computational simulation. X.D.Y. and J.Z. directed the project and conceived the idea. X.D.Y. and J.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all of the authors. All of the authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript and discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shou-Tian Zheng, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, XD., Lv, H., Sun, Y. et al. Photothermal-assisted NH3 release in a bipyridinium-functionalized metal-organic framework adsorbent. Nat Commun 16, 11426 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66380-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66380-w