Abstract

The African Early Pleistocene is a time of evolutionary change and techno-behavioral innovation in human prehistory that sees the advent of our own genus, Homo, from earlier australopithecine ancestors by 2.8-2.3 million years ago. This was followed by the origin and dispersal of Homo erectus sensu lato across Africa and Eurasia between ~ 2.0 and 1.1 Ma and the emergence of both large-brained (e.g., Bodo, Kabwe) and small-brained (e.g., H. naledi) lineages in the Middle Pleistocene of Africa. Here we present a newly reconstructed face of the DAN5/P1 cranium from Gona, Ethiopia (1.6-1.5 Ma) that, in conjunction with the cranial vault, is a mostly complete Early Pleistocene Homo cranium from the Horn of Africa. Morphometric analyses demonstrate a combination of H. erectus-like cranial traits and basal Homo-like facial and dental features combined with a small brain size in DAN5/P1. The presence of such a morphological mosaic contemporaneous with or postdating the emergence of the indisputable H. erectus craniodental complex around 1.6 Ma implies an intricate evolutionary transition from early Homo to H. erectus. This finding also supports a long persistence of small-brained, plesiomorphic Homo group(s) alongside other Homo groups that experienced continued encephalization through the Early to Middle Pleistocene of Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oldest fossils assigned to our genus are ~2.8 million years old (Myr) from Ethiopia and signal a long history of Homo evolution in the Rift Valley1,2,3. There is evidence of multiple Homo lineages in Africa by 2.0–1.9 million years ago (Ma) and an archaeological and paleontological record of expansion to more temperate habitats in the Caucasus and Asia between 2.0 and 1.8 Ma4 (Fig. 1). The last appearance datum for the more archaic Homo habilis species (or “1813 group”) is ~1.67 (OH 13) or ~1.44 Ma, if KNM-ER 42703 is correctly attributed to H. habilis5, which is uncertain6. The archetypal early African Homo erectus fossils from Kenya (i.e., KNM-ER 3733, 3883; and the adolescent KNM-WT 15000) already present a suite of traits that distinguish them from early Homo taxa by 1.6–1.5 Ma, including larger brains and bodies, smaller postcanine dentition, more pronounced cranial superstructures (e.g., projecting and tall brow ridges), a relatively wide midface and nasal aperture, deep palate, and projecting nasal bridge1,6,7,8,9,10,11. The only evidence for H. erectus sensu lato in Africa before 1.8 Ma are fragmentary or juvenile fossils12,13,14, while fossils expressing both ancestral H. habilis and more derived H. erectus s.l. morphological traits are only known from Dmanisi, Georgia at 1.77 Ma15,16. Thus, H. erectus emerged from basal Homo between 2.0 and 1.6 million years ago, but when, where (Africa or Eurasia), and how it occurred remain unclear. An expanded fossil record also documents significant variation in endocranial volume17,18 and craniofacial6,8 and dentognathic morphology19,20 throughout the Early Pleistocene, which extends to the Middle Pleistocene with the addition of small-brained Homo lineages to the human tree.

The solid bars of the timeline indicate well-established first and last appearance data; the horizontal stripes indicate possible extensions of the time range based on fragmentary or juvenile fossils. Diagonal lines signal earlier archaeological presence in those regions. The question mark indicates a possible date of <1.49 Ma for the Mojokerto, Indonesia site cf.22,23,24,25. The horizontal gray bar represents the time range associated with DAN5/P1. Colors on the map indicate presence of fossils matching taxa or geographic groups of H. erectus as indicated in the timeline. Surface renderings of the best-preserved regional representatives of archaic or small-brained Homo fossils (beginning at top and continuing clockwise): D2700, KNM-ER 1813, KNM-ER 1470, KNM-ER 3733, SK 847, OH 24, KNM-WT 15000, and DAN5/P1. All surface renderings visualized at FOV 0° (parallel). Map was generated in “rnaturalearth” package68 for R.

The initial announcement of DAN5/P1 assigned it to H. erectus on the basis of derived neurocranial traits21. Subsequent analyses of neurocranial shape and endocranial morphology confirmed affinity with H. erectus but also noted similarities to early (pre-erectus) Homo fossils such as KNM-ER 181317,18. Only limited information about the partial maxilla and dentition was presented in the original description21. Yet, facial and dental traits are increasingly important in early Homo systematics, given overlap in brain size among closely related hominins6,8,22. The DAN5/P1 fossil is a rare opportunity to evaluate neurocranial, facial, and dental anatomy in a single Early Pleistocene Homo fossil and thus has significant implications for this discussion.

Here we present a new cranial reconstruction of the 1.6–1.5 Myr DAN5/P1 fossil from Gona, Ethiopia. This study demonstrates that the small-brained adult DAN5/P1 fossil (598 cm3 21) presents a previously undocumented combination of early Homo and H. erectus features in an African fossil.

Results

DAN5/P1 cranial reconstruction

Physical and virtual reconstructions of the DAN5/P1 neurocranium were presented previously17,21. The face reconstruction, which is new, involves 3D surface models generated from micro-computerized tomographic (µ-CT) scans of the left and right maxillae (hemi-palates), left infraorbital fragment of the maxilla, left zygomatic fragment containing the frontal process, right P3, and left P4-M3 (the left P3 was recovered, but not µ-CT scanned) (Fig. 2a, b). The right P3 was originally misidentified as a right P4 21 (Supplementary Note 1). The preserved fragments of the face were joined together along sutures (e.g., left infraorbital and zygomatic) or postmortem breaks (e.g., left infraorbital and hemi-palate) and the teeth were positioned with reference to dental alveoli and interdental wear facets (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1). The reconstruction applied standard virtual reconstruction techniques (e.g., repositioning and reflection of elements and landmark-based superimposition23) to fit together the five bony fragments and five postcanine teeth. There were many anatomical constraints which limited the way in which these fragments could be assembled. For example, the frontal process of the infraorbital fragment must be oriented to articulate with the frontal bone at the frontomaxillary suture, but the fragment must also align with the contours implied by the maxilla (including the zygomatic root) with which it was originally continuous. Its final position must also accommodate the zygomatic bone along the zygomaxillary suture. Such considerations applied to each element. The face was then hafted onto the neurocranium to produce a largely complete cranium (Fig. 2e, f); an alternative reconstruction with a more posteriorly positioned face was also generated (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Original fossil fragments of face: a right and left hemimaxillae, b left infraorbital region and left frontal process of the zygomatic bone. c Inferior and d anterior-oblique views showing surface renderings of original pieces in anatomical position after removal of matrix via segmentation and virtual reconstruction of face. Colors serve to highlight individual fragments manipulated in the reconstruction process. Arrow indicates the left zygomatic root, which was displaced during the fossilization process (seen in a) and re-positioned with reference to the corresponding morphology on the right during the virtual reconstruction (seen in (d); Supplementary Fig. 1). e Anterior and f lateral views of cranial reconstruction in Frankfort Horizontal after duplicating and reflecting pieces across the midline and positioning face on cranial vault. All surface renderings visualized at FOV 0° (parallel). Photographs copyright M. Rogers.

Face morphology

In lateral view, the face is gently sloping anteriorly from below the projecting supraorbital torus, with a concave “nasocanine contour” (sensu24) (Fig. 2f). Many face dimensions in DAN5/P1 overlap with early Homo and early H. erectus from Africa and Eurasia (Table 1), but the superior facial and nasal heights of DAN5/P1 are absolutely short compared to African H. erectus and similar to, e.g., OH 24 (H. habilis) and D4500 (Dmanisi H. erectus).

The supraorbital torus is vertically thick and projecting with a continuous post-toral sulcus; this morphology is typical of H. erectus. The height of the torus at mid-orbit is within the range of other small African fossils assigned to H. erectus (Supplementary Table 9). The strong arching of the torus contributes to the circular orbit. An arched torus is variably expressed in small-brained Homo fossils (e.g., KNM-ER 1813 and KNM-OL 45500; Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). The inferior orbital margin is sharp and the frontal process of the zygomatic faces more anteriorly than antero-laterally. The ratio of cheek height to facial length in DAN5/P1 is similar to both H. habilis and early H. erectus (Table 1). Its nearly vertical midface with weakly everted nasal margins resembles early Homo and D2700 more so than other H. erectus25 and differs from the more rounded form in KNM-ER 3733 and KNM-ER 3883 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The well-developed maxillary sulcus seen in DAN5/P1 (Supplementary Fig. 5a) is more common in H. erectus than early Homo. The position of the anterior border of the maxillary zygomatic process at the P3/P4 level in DAN5/P1 is more anterior than in adult H. erectus, but was described similarly for H. naledi26. The nasal aperture does not show the widening typical of African H. erectus (Table 1). Nasal breadth is similar in DAN5/P1 and the early Homo KNM-ER 1805 fossil, but DAN5/P1 has a shorter nasal height and taller alveolar clivus than KNM-ER 1805. The subnasal clivus transitions smoothly to the nasal floor with no spinal or lateral crests; cresting is common for most early Homo / H. erectus fossils as well as H. naledi, but low topography of the nasal sill is documented in the adolescent KNM-WT 15000 and the Dmanisi sample27,28. There is a blunt anterior nasal spine, with no indication of anterior projection as in H. naledi28, although this region could be damaged.

The palate is large relative to endocranial volume, which aligns DAN5/P1 with early Homo and basal H. erectus from Eurasia, rather than East African H. erectus (Table 1). The DAN5/P1 palate has parallel molar rows and the preserved anterior alveoli suggested vertically oriented incisor roots (Supplementary Fig. 5c). However, it does not resemble the long, narrow dental arcade implied by the reconstruction of the OH 7 H. habilis specimen6. Its palate depth is in the range of H. erectus and at the high end of variation for early Homo. The incisive canal opens well behind the central incisors, which is primitive for the genus Homo16.

The nasoalveolar clivus is moderately prognathic and the squared-off anterior maxilla has a stout, rounded canine jugum that forms the “corner” of the palate. The canine alveolus housed a short, conical canine root. While short canine roots are said to be a H. erectus feature8, root length is variable and not fully characterized in Pleistocene Homo. For example, both OH 65 (early Homo)29 and D2700 (early H. erectus) fossils have longer canine roots. The canine jugum does not contribute to the lateral nasal aperture as it does in the Dmanisi sample, H. floresiensis, some early Homo (e.g., OH 24), and some African H. erectus (KNM-ER 3733). The DAN5/P1 clivus projects slightly beyond the level of the canine jugum in lateral view, which is typical for early Homo and early H. erectus1. The maxillary flexion, maxillary sulcus, canine jugum, moderately prognathic subnasal clivus, and more anterior origin of the maxillary zygomatic process in DAN5/P1 differ from the condition described for ATE7-1, a Spanish fossil recently assigned to H. aff. erectus30. A thin crest extends superiorly from the jugum toward the zygomatic root and demarcates a deep, round fossa between the lateral body of the maxilla and the anterior zygomatic process (Supplementary Fig. 5b). A similar morphology was described for the early Homo fossil A.L. 666-11 and the fossa is also seen in some Dmanisi fossils. The maxillary sinus extends into the zygomatic process laterally and the frontal process of the maxilla superiorly and septa partition the sinus anteriorly. More detailed discussion of the maxillary sulcus and its relationship to surrounding features can be found in Supplementary Note 2 and comparisons of DAN5/P1 to less complete hominins are detailed in Supplementary Note 3.

Some description of the teeth was provided in the original announcement21. We also present additional description (Supplementary Note 1), photographs (Supplementary Fig. 6) and crown dimensions (Supplementary Table 8).

Cranial shape and midface topography

Analysis of cranial (face and vault) shape using 3D landmarks demonstrates a broadly archaic-to-modern trajectory of shape differences along Principal Component (PC) 1. Low-scoring early Homo have a relatively smaller vault and longer, more prognathic face and clivus and a transversely flatter cheek compared to more derived Homo species on PC 1 (Fig. 3). There is separation of H. erectus and H. floresiensis from other Homo species, particularly Middle Pleistocene Homo and H. habilis, on PC 2. The second PC reflects the characteristic long, low vault that is wide inferiorly in H. erectus (and H. floresiensis), combined with relatively tall orbits, vertically shorter face below the orbits, and a long palate with moderate alveolar prognathism. The third PC mostly reflects unique anatomy of Neanderthals. DAN5/P1 is within the H. erectus range of variation and plots close to the adolescent (KNM-WT 15000) and subadult (D2700) H. erectus fossils in the subspace of PCs 1 and 2 and close to D2700 on PC 3 as well. As a group, these three fossils score lower than other H. erectus fossils and overlap H. habilis on PC 1, implying a higher face to neurocranium ratio compared to KNM-ER 3733. DAN5/P1 is the nearest neighbor for several H. erectus fossils in full shape space and is itself most similar to the subadult H. erectus fossil KNM-WT 15000. Of the adult fossils, DAN5/P1 is closest to KNM-ER 1813 in full shape space. The DAN5/P1 alternative reconstruction yields substantially similar results, while our reconstruction of the less complete LES1 H. naledi fossil is aligned with early Homo (Supplementary Note 4; Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8).

Ordinations of a PCs 1 and 2 and b PCs 1 and 3 with inset showing landmarks used in analysis (Supplementary Data 1). Convex hulls indicate group membership. Colors are as follows: Early Homo = orange, H. erectus = red, H. floresiensis = pink, Mid-Pleistocene Homo = magenta, H. neanderthalensis = purple and early H. sapiens = light blue. The black star represents DAN5/P1. Arrows in a point in the direction of nearest neighbors in full shape space (colored = within-group neighbors and black dashed = between-group neighbors). DAN5/P1 is most similar to the juvenile KNM-WT 15000 H. erectus fossil. Shape differences from the negative (left) to positive (right) ends of the PC axes are shown as warpings of the DAN5/P1 surface and are illustrated parallel to each axis. Specimen abbreviations: prefix K KNM-ER, prefix WT KNM-WT, S17 Sangiran 17, Zkd_T Zhoukoudian recon, Petr Petralona, Kabw Kabwe, SH5 Sima de los Huesos V, Ferr La Ferrassie, Chap La Chapelle aux Saints, Sc1 Saccopastore 1, Sk5 Skhul V, prefix Q Qafzeh, JI1 Jebel Irhoud 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We observe good taxonomic resolution based on a separate analysis of the midface, with the strongest contrasts between “early Homo“ (e.g., H. habilis) and Neanderthals on PC 1 (Fig. 4). The majority of the early Homo and H. erectus fossils separate from each other along PC 1 and DAN5/P1 is within the early Homo range on this component. The one Indonesian and two Kenyan fossils assigned to H. erectus have higher PC 1 scores, while the D2700 fossil from Dmanisi is close to both H. habilis and geologically younger members of H. erectus. Low-scoring individuals like DAN5/P1 have transversely flat midfaces, an anterior origin of the zygomatic process, a more sloped subnasal clivus and a narrower, non-projecting nasal region. The face is shallower antero-posteriorly and the anterior palate is wider and more squared off. PC 2 serves to highlight unique aspects of the early modern human face, particularly compared to H. naledi. H. habilis, H. erectus, and DAN5/P1 have more intermediate scores. This third PC contrasts the more sloping face and shorter subnasal clivus of H. naledi compared to the taller and more upright face with a projecting nasal bridge of H. erectus, H. floresiensis and KNM-ER 1805 (an early Homo fossil of uncertain species attribution). DAN5 scores lower than all H. erectus on PC 3 and near to OH 24 and KNM-ER 1813 (both H. habilis). DAN5/P1 is closest in full shape space to KNM-ER 1813 (H. habilis), but also quite similar to OH 24, the subadult D2700, and the adolescent KNM-WT 15000. Further development of the face in the adolescent KNM-WT 15000 fossil would have made it more like KNM-ER 3733, placing it further from DAN5/P1 on PC 2 as an adult (Supplementary Note 4; Supplementary Fig. 8).

Ordination of a PCs 1 and 2 and b PCs 1 and 3, with inset showing surface landmarks and semilandmarks used in analysis (Supplementary Data 1). Convex hulls indicate group membership. Colors are as follows: Early Homo = orange, H. erectus = red, H. floresiensis = pink, H. naledi: brown, Mid-Pleistocene Homo = magenta, H. neanderthalensis = purple and early H. sapiens = light blue. The black star represents DAN5/P1. Arrows in a point toward nearest neighbors in full shape space (colored if within the same group and black dashed if between members of different groups). Shape differences from the negative (gray) to positive (semi-transparent aqua) ends of c PC 1, d PC 2, and e PC 3 shown as surface warpings based on the DAN5/P1 face. Specimen abbreviations: prefix K KNM-ER, prefix WT KNM-WT, S17 Sangiran 17, Petr Petralona, Kabw Kabwe, Arago Arago 21, SH5 Sima de los Huesos V, Ferr La Ferrassie, Chap La Chapelle aux Saints, Gibr Gibraltar 1, Guat Guattari, Shan1 Shanidar 1, Q6 Qafzeh 6, Floris Florisbad, JI1 Jebel Irhoud 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Dental analyses

Morphological descriptions of individual teeth are provided in Supplementary Note 2. In this section, we report results of the following metric analyses: crown size analyses based on computed crown area, tooth size apportionment analyses (TSA) that examine the relative mesiodistal (MD) and buccolingual (BL) diameters within each tooth row and normalized Elliptic Fourier Analyses (EFA) of the crown contour of each postcanine tooth. The computed crown areas (MD × BL: Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 8) for the DAN5/P1 molars fit comfortably in the range of H. habilis. Both computed and measured crown base areas reveal that M3 is largest, followed by M1 in DAN5/P1 (Supplementary Table 8). DAN5/P1 does not display the M1 < M2 size sequence typical of H. habilis, but this morphology is shared with L894-1 and is not unique among our H. habilis sample. The molars, particularly the M1 and M3 are at the high end of variation for both African and Dmanisi early H. erectus (5). There is a clear trend for premolar size reduction from early Homo to H. erectus, but the premolars of DAN5/P1 are small even in comparison with early African, Georgian, and Indonesian H. erectus.

DAN5/P1 compared to a Pleistocene Homo taxa and individual specimens of b early Homo (n = 22), c Georgian H. erectus (n = 4), and d African H. erectus (n = 9). DAN5/P1 is represented by the black line/dots in all panels. Specimen abbreviations: prefix K KNM-ER, prefix WT KNM-WT, OmoSH1 Omo SH1-1-17, O75–14 Omo 75–14. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The TSA analysis for size-corrected MD and BL crown dimensions of P3‒M3 (Fig. 6a) and P4‒M3 (Supplementary Fig. 9) mostly discriminates between H. habilis and H. erectus, reflecting the proportionally small P3, relatively MD elongated and narrow P4, MD short M1, and large M3 in the former. DAN5/P1 and D4500 have the highest PC 1 scores, but also the most extreme PC 2 scores in the sample. DAN5/P1 differs from D4500 along PC 2 in having particularly narrow premolars bucco-lingually, whereas the M1 is proportionally smaller in D4500 (Fig. 6b). Overall, DAN5/P1, D4500, and H. naledi group with H. habilis, whereas one early Homo specimen, OH 65, and D2700 group with African and Indonesian H. erectus. A previous study also suggested that OH 65 shows affinities with H. erectus in dental arcade shape6, which may reflect large intra-specific variation.

a Ordination of PC 1 and PC 2 of size corrected MD and BL dimensions for P3‒M3 (TSA). Description of changes along each PC are based on PC loadings ≥ |0.6|. b Visual representation of loadings in this PC subspace at the position corresponding to DAN5/P1. White lines represent negative loadings (relatively smaller dimensions) and black lines represent positive loadings (relatively larger dimensions), with thickness corresponding to strength of the loading. c Occlusal views of left postcanine teeth in DAN5/P1 to scale (adherent bone masked in M1 photograph). Convex hulls indicate group membership. Colors are as follows: Early Homo = orange, H. erectus = red, H. naledi = brown. A square differentiates “Sangiran Lower” H. erectus. The black star represents DAN5/P1. Small symbols represent individual fossils. Specimen abbreviations: S4 Sangiran IV, L894 L894-1. Large symbols are group averages for early African H. erectus (EAf_erec), “Sangiran Upper” H. erectus (USang_erec), and H. naledi (H_nal) (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Data 1). Photographs courtesy G. Suwa. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Premolar crown contours differ between early Homo and Early Pleistocene H. erectus from East Africa and Indonesia. Namely, early Homo is characterized by MD long premolars, whereas H. erectus has MD short premolar crowns (PC 1), and DAN5/P1 clusters with the former in this respect (Fig. 7a, b). Molar crown contours tend to separate African and Indonesian samples, but do not effectively distinguish H. habilis from H. erectus in East Africa (Fig. 7c–e). Specifically, MD long (Africa) versus short (Indonesia) crown of M1 and M3 (PC 1), and rectangular (Indonesia) versus rhomboid (Africa) crown of M2 (PC 2) characterize the two regional samples, and DAN5/P1 always clusters with the African sample. The shape of the M3 in DAN5/P1 is most comparable to early Homo rather than H. erectus fossils from Africa. Taken together, DAN5/P1 shows affinities with early Homo, including H. habilis, in premolar and M3 crown shape; its M1 and M2 crown contours are not taxonomically informative.

Plots of PC scores derived from the normalized Elliptic Fourier Analyses (EFAs), based on crown contours of a P3 (n = 17), b P4 (n = 17), c M1 (n = 27), d M2 (n = 19), and e M3 (n = 16). Shape differences along PC axes are shown on left teeth, with mesial directed up, two standard deviations from the origin. Points represent individual fossils (Supplementary Table 3). Convex hulls indicate group membership. Colors are as follows: Early Homo = orange and H. erectus = red. Squares differentiate “Sangiran Lower” H. erectus. Specimen abbreviations: prefix K KNM-ER, prefix S Sangiran, KGA Kenyan Gregory Konso, OH Olduvai Hominid, O75-14 Omo 75–14, L894 L894-1, Omo_SH1 Omo SH1-1-17, N2005 Njg 2005.05, SIX Skull IX (Sangiran). The black star represents DAN5/P1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The DAN5/P1 reconstruction from Gona, Ethiopia, is a complete Early Pleistocene Homo cranium from northeast Africa (only the sixth from Africa; Fig. 1) and provides a high level of detail regarding midface morphology. DAN5/P1 is, to our knowledge, the first African fossil to exhibit a mixture of H. erectus and early Homo features. Some facial and possibly dental traits in DAN5/P1 appear to be derived for H. erectus sensu lato (e.g., deep palate, maxillary sulcus, projecting brow ridge, canine jugum, small premolars), corroborating previous work from the neurocranium (see also refs. 17,21) (Supplementary Table 10). Yet, the DAN5/P1 fossil, like the Dmanisi sample, blurs the boundaries between early Homo taxa (particularly “classic” H. habilis) and H. erectus. DAN5/P1 overlaps H. habilis and early Georgian H. erectus with regard to endocranial volume17,18, relative palate size, and dental dimensions (Figs. 2–4). For example, the M1 and M3 areas of DAN5/P1 are within the range of early Homo and early H. erectus from the Eurasian site of Dmanisi, but among the largest or exceed the values in African H. erectus (Fig. 5). Aspects of facial architecture, including the transversely flat infraorbital region, non-projecting nasal region, and anterior origin of the zygomatic process, are plesiomorphic in DAN5/P1 compared to contemporaneous H. erectus fossils from Kenya, confirmed by direct superimposition of the DAN5/P1 and KNM-ER 3733 faces (Supplementary Fig. 10). Altogether, this suggests that DAN5/P1 better reflects the basal African H. erectus morphology than the archetypal and roughly contemporaneous Kenyan H. erectus fossils (Supplementary Table 11), such as KNM-ER 3733 and KNM-WT 15000.

The evolutionary contrasts in brain size and face morphology embodied by the broadly contemporaneous DAN5/P1 and Kenyan fossils, KNM-ER 3733 and KNM-WT 15000 (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11) imply complex population structure rather than simple coexistence of two different lineages in the African Early Pleistocene. It is likely that the contrasts documented here signal between-population variation (assuming a single H. erectus species) in eastern Africa at 1.6–1.5 Ma. This view is consistent with previous depictions of H. erectus as a polytypic species across its temporo-spatial range9,31,32. The unique rift basin landscape of the East African Rift System, alongside the potential low population density of early Pleistocene hominins, could lead to population separation between the Horn of Africa and Lake Turkana lineages33,34. In this scenario, the Horn of Africa group retained the more archaic morphology of the population dispersing from Africa ~1.9 Ma, whereas the Kenyan group underwent greater in situ evolution. The more fragmentary Ethiopian H. erectus record may support this north-south division, but the larger-brained BSN/P1 H. erectus fossils from younger deposits at Gona (1.26 Ma) implies subsequent population replacement or in situ evolution (Supplementary Discussion). Other interpretations are, of course, possible. For example, an expanded fossil record could reveal high within-population variation (but see ref. 35 or interbreeding could result in the mosaic of ancestral and more derived features (Supplementary Discussion).

Assuming that the ages for DAN5/P1 (1.6–1.5 Ma), KNM-ER 3733 (~1.6 Ma), and OH 13 (H. habilis; ~1.67 Ma) are correct, the nearly complete adult cranium of DAN5/P1 not only supports the late survival of basal Homo facial and dental morphologies but also highlights the piecemeal nature of H. erectus craniodental evolution. Limitations on dating precision do not entirely preclude a chronology where DAN5/P1 is geologically older than KNM-ER 3733 (Supplementary Discussion). While this can be accommodated within the evolutionary scenario described above, it could also signal rapid anagenetic evolution between the Gona and Koobi Fora populations. DAN5/P1 also presents similarities to the Middle Pleistocene H. naledi species, including a small brain, flat nasal region, anterior origin of the zygomatic process and distinct occipital protuberance (Figs. 3 and S4f) despite its larger cheek teeth (Fig. 5a). These resemblances are interesting, but insufficient to support a specific evolutionary connection between these geographically and temporally distant groups. Nevertheless, DAN5/P1 confirms the presence of small-brained Homo fossils in Africa during the Early to Middle Pleistocene14,32,36,37,38, and future research should clarify the evolutionary importance of the resemblances between DAN5/P1 and H. naledi.

The Gona evidence, along with that from Dmanisi, hints that key behavioral/technological innovations may precede major morphological transformations. Diverse lines of evidence point to a broadened dietary range and access to animal resources at both Gona21 and Dmanisi39,40. Moreover, both Mode 1 (simple cores and flakes) and Mode 2 (Acheulean) stone tools are documented at DAN521. Yet, the endocranial volume of DAN5/P1 and the Dmanisi fossils show minimal expansion over early Homo18 and both DAN5/P1 and D4500 have large molars, including unreduced M3s41 (Fig. 6), and similar scaling of face to neurocranium as in early Homo (Fig. 2). While acknowledging high error associated with body mass estimates from cranial variables42, the relationship between orbital dimensions and body mass in hominoids suggests that DAN5/P1 was smaller than well-known contemporaries from Kenya—KNM-ER 3733 and 3883 and KNM-WT 15000—and more similar to adults from Dmanisi (Supplementary Fig. S11). The fossil pelvis BSN49/P27 also confirms the presence of a small-bodied hominin at Gona 400-700 thousand years after DAN5/P143,44. Although speculative, this pattern implies a dissociation between some morphological changes traditionally associated with H. erectus, and the shift to higher quality foods in the diet and initial appearance of Acheulean technology.

The DAN5/P1 fossil confirms that the emergence of H. erectus was not a simple story. The DAN5 site documents hominins with a combination of ancestral and more derived craniofacial/dental features who made both Mode 1 and Mode 2 stone tools21. The current study also adds data to the ongoing debate about the birthplace of H. erectus. Although some researchers suggest a Eurasian origin because of the earlier occurrence of H. erectus-like cranial features in Georgia45, the basal H. erectus morphology in DAN5/P1 is compatible with local evolution of H. erectus in East Africa.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected from the DAN5/P1 specimen (from the original micro-CT scans and two virtual reconstructions built from the surface renderings based on the same scan data). The cranial fragments and teeth of DAN5/P1 were µCT-scanned by T. Sasaki (Kyoto University Museum) at the National Museum of Ethiopia in 2015 on a SkyScan 1173 benchtop scanner at 100 kV and 31–63 mA with a rotation step of 0.4–0.6. The final resolution was 140 μm/pixel. Surface renderings of the cranial pieces and individual teeth were generated from the µCT scans in Avizo 3D 2021.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; hereafter “Avizo”). In addition to the virtual reconstruction of DAN5/P1 described here, the hominin sample for the comparative analyses included fossils assigned to early Homo, H. erectus sensu lato from Africa and Eurasia (including a virtual reconstruction of KNM-ER 3733, Supplementary Fig. 12), Middle Pleistocene species (including a virtual reconstruction of the small-brained H. naledi LES1, Supplementary Fig. 12, and H. floresiensis), and early H. sapiens (modern humans) (Supplementary Tables 1–3). The comparative sample of Pleistocene hominins included original fossils, virtual reconstructions and research quality casts (Supplementary Tables 1–3; Supplementary Fig. 2), including scan data from the Georgian National Museum, Kenya National Museums, American Museum of Natural History and Ethiopian National Museum.

All individuals were adult with the exception of two subadult specimens—the early adolescent KNM-WT 15000 and the older adolescent D270016—included to expand the small early H. erectus sample. The Indonesian H. erectus sample is from Sangiran, Java, which we divide into two chronological subsamples, “Sangiran Lower” and “Sangiran Upper,” given the demonstrated differences in their tooth crown size and cranio-dental morphology22,46. We exclude KNM-ER 42703 from the East African dental sample because of the severe tooth wear as well as taxonomic uncertainty of this specimen6. Taxonomic status for OH 65 is uncertain6, but we include it in H. habilis as originally proposed29. The late Middle Pleistocene H. naledi from South Africa and H. floresiensis from Indonesia are included because of their small brain size and suggested affinities with both H. habilis and H. erectus47,48.

Virtual reconstruction of DAN5/P1 face

Standard virtual reconstruction techniques were applied to the DAN5/P1 face and cranial reconstruction as reviewed by ref. 23. This involved reflecting missing elements from one side to the other, superimposition of mirrored elements, and repositioning of elements. The following Geomagic Wrap 2024.3.1 (Oqton; hereafter “Geomagic”) tools were utilized: “Duplicate,” “Mirror,” “Manual Registration” for initial superimposition with additional refinement using ‘Global Registration’ or manual repositioning using “Object Mover.”

The matrix cementing the left zygomatic root fragment to the palate on that side21 was manually segmented and removed in Avizo, isolating the two pieces, but also revealing a small fragment that was displaced medially and anteriorly. This was also segmented out separately. Subsequent steps were performed in Geomagic. The right hemipalate was duplicated, mirrored, and aligned with the left palate based on the hard palate contours and dental alveoli (I1, I2, P3, and P4) (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Next, the left zygomatic root was superimposed onto the mirrored right side using local anatomical features (e.g., the vertical crest extended from the canine alveolus, the depression immediately posterior to this crest, the P3 buccal alveolus, and the anterior root of the zygomatic process; Supplementary Fig. 5). The alveolar bone that intervenes between neighboring teeth from the canine to M1 is preserved on the neighboring regions of the palate and zygomatic root, respectively, further confirming the anatomical validity of this repositioning (Supplementary Fig. 1). The small fragment of displaced bone was re-positioned by sliding it posteriorly and laterally to align with the broken edge of the zygomatic root fragment (green in Supplementary Fig. 1).

The right and left hemi-palates were then aligned along the median plane to produce a smooth contour of the subnasal clivus and roof of the palate. Both hemi-palates were duplicated and reflected across the midline to produce a more complete palate, into which the left P4 and M1 were positioned based on congruence of the roots and dental alveoli (Fig. 2). The P3 crown and complete M2 and M3 were added to the model based on alignment of corresponding interproximal wear facets and root orientation. The left infraorbital fragment of the maxilla was aligned with the superior border of the left zygomatic process, and the zygomatic fragment was further joined to this piece along the zygomaxillary suture (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). The left infraorbital and zygomatic pieces and all teeth were duplicated and reflected across the midline to create a maximally complete surface (Supplementary Fig. 2a–f).

The face was hafted to the cranial vault by aligning the preserved lateral orbital wall across the frontozygomatic suture (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) on the left and refined by maintaining continuity between the frontal process of the maxilla and the root of the nose and ensuring a reasonable orientation of the occlusal plane. The position of the face is broadly consistent with the expected orthogonal relationship of the posterior maxillary plane and neutral horizontal axis of the orbit (based on the estimated position of the junction of anterior and middle cranial fossae). The final reconstruction yields a mostly complete nasal aperture, orbital margin, infraorbital region, anterior palate, and dental arcade.

Anatomical features constrained many aspects of the reconstruction. While some virtual reconstructions produce multiple reconstructions to account for uncertainty, the complex topography of the fossil fragments constrains their positioning along multiple axes, limiting alternative arrangements that can satisfy well-established anatomical relationships. For example, the incisive canal is preserved on the medial surface of both hemipalates. This confirms good preservation of the median plane on both sides. The intermaxillary suture on the subnasal clivus is also clearly visible on the right and left fragments, where the bone rises to a gentle ridge on either side, further constraining the position of the right and left sides of the palate. As noted above, the left maxillary zygomatic root fragment was initially aligned using the mirrored right side as a guide, but the correct alignment of the canine and premolar alveoli, which are preserved on both the hemipalate and zygomatic root fragment, provides further validation (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c).

Similar considerations were used in the final positioning of the infraorbital fragment (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The medial border preserves the lateral nasal aperture, which should align in the same sagittal plane as the inferior lateral nasal wall preserved more posteriorly on the left hemipalate. The small fragment of the lateral nasal aperture preserved on the right maxilla further dictated the medio-lateral position of the infraorbital fragment. The angulation of this piece in the sagittal plane was determined by the requirement that it meet the frontal bone at the frontomaxillary suture superiorly and be superimposed with the mirrored right inferior nasal aperture inferiorly. There is a narrow projection of bone on the inferior border of the infraorbital fragment that appears to fit between the left hemipalate and zygomatic root fragment. We propose that this confirms that there is a natural join between the infraorbital fragment and the hemipalate/zygomatic root inferiorly. The current reconstruction produces a smooth contour from the infraorbital fragment to the subnasal contour, whereas other alignments would require flexion from the infraorbital plane to the subnasal clivus inferiorly.

Finally, the lateral positioning of the zygomatic fragment was limited by the presence of the orbital portion of the frontal bone, which articulates with the zygomatic bone on the lateral orbit wall. Simultaneously, its medial positioning was limited by the presence of the maxilla with which it also forms an articulation (zygomaxillary suture). This latter articulation also proscribes how anterior or lateral facing the zygomatic fragment can be as it must align with this suture. Moreover, the zygomatic bone preserves the orbital surface, which must be at the same vertical level as the orbital surface of the maxilla more medially. Additionally, the degree to which the zygomatic fragment is ‘hinged’ along the relatively straight zygomaxillary suture is constrained by the requirements that the frontal process aligns with the course of the lateral supraorbital torus, while the frontal process of the maxilla must be oriented to intersect with the frontal bone at the frontomaxillary suture.

The biggest source of uncertainty in the current reconstruction is the hafting of the face on the vault, which we addressed with an alternative reconstruction (see next section). Smaller uncertainties are associated with the relative orientation of the left and right palate and the placement of M2 and M3, which are less constrained than the P3-M1 positions (limitations are also addressed in Supplementary Discussion).

Alternative reconstruction of DAN5/P1

We present an alternative reconstruction for DAN5/P1 that positions the face more posteriorly with respect to the neurocranium (Supplementary Fig. 2i). In order to match the corresponding surfaces of the lateral orbit wall on the face and vault, the face was also shifted slightly inferiorly. The overall impression is not very different, but the vertical face height is greater and less prognathic overall, with a taller orbit and deeper nasal root, and the supraorbital torus projects farther forward ahead of the inferior orbit. Further posterior shifting of the face requires additional downward movement to prevent the frontal and zygomatic bones from overlapping in the lateral orbit, which produces a disproportionately tall orbit that seems unlikely. Even in the original reconstruction, the orbital index (height/breadth) of 0.92 is equal to the highest values reported for H. erectus and early Homo, and a further inferior shift of the face would increase orbit height and create an unusual orbit shape. We re-ran the cranial principal component analysis (PCA) using the alternative reconstruction. The alternative reconstruction did not change the part of the face included in the midface topography analysis.

Strategies for mediating taphonomic distortion

Taphonomic distortion in the KNM-ER 3733 fossil was corrected by first performing a retrodeformation via the procedure described by ref. 49 in the R statistical environment v. 4.5.050 and then manually repositioning the left zygomatic bone to reduce the gap between the zygomatic and frontal bones at the fronto-zygomatic suture in Geomagic (Supplementary Fig. 12a–f). The surface renderings were generated from CT scans provided by the Department of Earth Sciences, National Museums of Kenya. We used a virtual reconstruction of KNM-WT 1500051 that corrected previously described asymmetry of the face and misalignment of the face and vault. The LES1 (H. naledi) cranium is not fully reconstructed physically, but scans of the calvaria, left temporal/occipital piece, maxilla, and nasals provided by J. Martin, and a small piece of the anterior left temporal bone from the Morphosource calvaria scan (Morphosource ID: 000084599; ark:/87602/m4/M84599) were articulated and mirrored across the midline. The nasals were articulated with the frontal and then duplicated and mirrored across the midline. The maxilla articulated with the nasal bones after a small superolateral rotation of the infraorbital piece. The right inferior nasal border and infraorbital region were then duplicated and mirrored to the right side, completing the reconstruction (Supplementary Fig. 12g–l).

Early Homo fossils are rare and poorly preserved, including the original KNM-ER 1470 and OH 24 fossils from Koobi Fora, Kenya, and Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, respectively. Right posterior vault and cranial base landmarks (e.g., asterion and postglenoid process) were reflected from the better-preserved left side in KNM-ER 1470 to avoid the more distorted right side. We used thin-plate spline (TPS) to estimate the position of landmarks in the regions affected by crushing of the superior vault in OH 24 (bregma, coronale, and opisthion). These “solutions” to the problem of taphonomic damage are imperfect, but the benefits of including rare African early Pleistocene fossils outweigh the disadvantages.

Linear craniofacial dimensions

Linear dimensions were acquired from the 3D model of the DAN5/P1 cranial reconstruction in Geomagic and used to generate shape ratios scaled by endocranial volume or superior face length (Table 1).

Landmark acquisition

Three-dimensional (3D) landmarks for the cranial analysis (Supplementary Table 4) and both landmarks and semilandmarks for the midface topography analysis (Supplementary Table 5) were collected from original fossils or casts of Pleistocene Homo fossils (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Data 1). The cranial landmarks were primarily acquired using a Microscribe 3D or Microscribe MX 3D digitizer and from surface renderings generated from CT, µCT, or surface scan data in a smaller number of cases, including the 3D model of the DAN5/P1 cranial reconstruction, using Avizo. All data for the midface analysis were collected from surface renderings in Landmark Editor52. After imputing missing landmark data (see below), the curve and surface semilandmarks were slid by minimizing the bending energy of a TPS deformation between each specimen and the sample mean shape (separately for the cranial and mid-face datasets). After sliding, all landmarks and semilandmarks were symmetrized and converted to shape variables using generalized Procrustes analysis for each dataset independently.

This was followed by principal components analysis of the superimposed cranial landmarks (41 total) or midface landmark/semlandmarks (12 and 81 total, respectively). We present PC ordinations overlaid with nearest neighbor connections calculated in full shape space. For the midface analysis, the KNM-ER 1805 fossil was projected onto the PC axes calculated from the remainder of the sample, as it suffered some taphonomic damage. Loadings on PCs were used to “warp” the surface of the DAN5/P1 surface rendering to visualize shape change in the cranium and midface analyses. Landmark and semilandmark data were processed and analyzed in RStudio v. 1.4.171753 primarily using “Morpho” v. 2.1254 and “geomorph” v. 4.0.1055,56 packages for R ordinations were produced with “ggplot2” v. 4.0.057.

Missing landmark estimation

Landmark estimation was considered on a case-by-case basis and tailored solutions were used in some cases (discussed below). Otherwise, landmarks were estimated using standard protocols58. Missing bilateral landmarks and semilandmarks were estimated by mirroring the preserved side (reflected relabeling) in the “Morpho” package for R. Missing landmarks and semilandmarks lacking a bilateral counterpart were estimated by deforming the sample average onto the deficient configuration using TPS interpolation in the “geomorph” package for R (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). In the cranial analysis, the TPS procedure was performed for the H. sapiens and non-H. sapiens (i.e., archaic) samples separately. In addition, four landmarks were included in the cranial TPS procedure to improve these estimates (frontomalaretemporale, parietal notch, canine-P3 interdental, M1–M2 interdental) but dropped before GPA and subsequent cranial shape analyses. Five or fewer unique landmarks were estimated for any one fossil in the cranial analyses. The average percentage of missing data was 6.9% (s.d. 2.8%) for the cranial analysis and 8.2% (s.d. 10.1%) for the midface analysis (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7).

Some minimal landmark estimation was deemed necessary to fully capture the face shape of DAN5/P1 in the cranial analysis. The nasoalveolar clivus and anterior palate of DAN5/P1 was superimposed with a surface model of the A.L. 666-1 maxilla, which was better preserved anteriorly, to establish the likely position of alveolare (Supplementary Fig. 2f). A small segment of well-preserved buccal alveolar bone between the P4 and M1 was isolated and repositioned between M2 and M3 to acquire the M2-M3 inter-dental landmark (Supplementary Fig. 2h). A second paired landmark, zygomaxillare inferior, captures the transverse orientation of the cheek in this fossil. The landmark was imputed using the TPS method based on reference to the rest of the non-H. sapiens cranial sample and its reasonableness was validated by comparison to the surface model of the face reconstruction. A similar approach of reconstructing alveolar bone for recording inter-dental landmarks was applied to the KNM-ER 3733 virtual reconstruction described previously. Likewise, a local alignment of the naseoalveolar clivus and anterior palate of OH 24 and A.L. 666-1 was used to establish the position of prosthion for the former.

With regard to the cranial analysis, LES1 is the most complete cranium available for H. naledi, which is of special interest given its similarly small endocranial volume and previously noted similarity to early Homo and H. erectus. However, the LES1 reconstruction (Supplementary Fig. 12g–l) would require TPS estimation of six unique landmarks, including all midline landmarks from the posterior neurocranium (opisthion, inion and lambda), which does not meet the criterion for inclusion in Fig. 2. The DH1 (H. naledi) vault, which was similar in morphology to LES1, was used to estimate the position of these midline points (Fig. S12k, l) in LES1 and the landmark configuration was projected onto the previously calculated axes from Fig. 3 and presented below.

For the midface analysis, two fossils require special mention. KNM-ER 3733 is the sole adult African H. erectus with a reasonably complete facial skeleton and LES1 is the only H. naledi with a preserved face. However, the face is damaged and requires estimation of a number of landmarks and semilandmarks in both cases (Supplementary Table 7). The nature of damage in KNM-ER 3733 allows for primarily interpolation among existing regions, but it remains the case that some error is introduced during the missing data estimation. For LES1, most missing data was located on the lateral maxilla and frontal process of the zygomatic. However, the FMT and FMO landmarks were present on the frontal bone and helped to anchor the height and breadth of the upper face. We performed a direct comparison of the DAN5/P1 and KNM-ER 3733 surfaces after scaling the latter to 86% of its original size (based on centroid size from the mid-face analysis) to validate topographic differences.

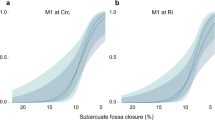

Assessing facial maturation in KNM-WT 15000

The young adolescent KNM-WT 15000 would have undergone additional facial development given its un-erupted third molars, based on analogy with extant hominoids59. We computed linear regressions of the Procrustes shape coordinates on the natural logarithm of centroid size in ontogenetic samples of Pan troglodytes (n = 12) and recent H. sapiens (n = 81) using the “RRPP” package v. 2.1.060,61 for R. We then used these two regressions to predict the adult shape of KNM-WT15000 by “growing” the fossil along each trajectory to the mean size of an adult chimp and human, respectively (developmental simulation62). This assumes a similar pattern of face development in H. erectus and either P. troglodytes or H. sapiens. The midface topography analysis was re-run with the estimated adult face shape of KNM-WT 15000.

Body mass estimation

Body mass was estimated in DAN5/P1, LB1, KNM-WT 15000, D4500, D3444, and D2700 based on the published least square regression equations based on hominoid data for orbital height and orbital area (height × breadth) as outlined in ref. 63. These were among the most reliable predictors among the cranial dimensions evaluated in that study. This was combined with estimates for other fossil hominins from the same ref. 63 and plotted alongside body mass estimates from supero-inferior femoral head diameter (or the equivalent acetabular diameter) presented in ref. 64 for additional context.

Dental analyses

Dental measurements of DAN5/P1 were based on 3D surface models produced from the CT scan (Supplementary Data 1). Prior to measurement, slight distortion of the glued connections in the right P3 crown had been virtually restored using Avizo 3D 2021.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MD and BL diameters of the teeth of DAN5/P1 were obtained using MeshLab 2022.02, while the same measurements for the comparative specimens were collected using a digital caliper (Mitsutoyo Inc.) and recorded to the nearest 0.1 mm. PCA of size-adjusted MD and BL diameters of the P3‒M3 or P4‒M3 crowns was used to investigate the “TSA” in the tooth row. The size-adjustment of the variables was done by dividing each measurement by the geometric mean of all the dimensions considered (MDs and BLs for P3‒M3 or P4‒M3). This method follows the previous study65 but differs from that study in that, for PCA, we use variance-covariance matrix rather than correlation matrix for the already size-adjusted variables. Visualization of TSA for DAN5/P1 and D4500 in the subspace of PCs 1 and 2 was calculated by first scaling the PC 1 and 2 eigenvectors by the PC 1 and 2 scores for DAN5/P1 and D4500, respectively; line thickness in Fig. 6b is then proportional to the sum of the scaled eigenvectors for each fossil.

Occlusal crown contours of maxillary premolars and molars were analyzed by normalized (i.e., size-standardized) EFA. Crown contours of DAN5/P1 were extracted from their 3D surface models as viewed from infinite distance, using Avizo and Geomagic. Those for the comparative specimens were taken from standardized photographs of high-quality plaster casts. A 100 mm macro lens was used for the photography to minimize parallax effect as detailed elsewhere66. In cases where interproximal wear on a tooth was minimal and the original occlusal contour could be assessed confidently with reference to the surrounding unworn enamel, we manually reconstructed the contour. The contours were taken from the better-preserved side. Comparisons were made on the images from the right teeth or horizontally flipped images of the left teeth. The crown contour of each tooth was captured with a tooth placed so that its cervical line is horizontal (whenever a marked enamel extension was present, it was not taken into account to orientate the cervical reference plane). To compute normalized elliptical Fourier descriptors (EFDs), each premolar crown was aligned along the long axis of its first ellipse, and each molar crown was aligned along its MD axis. EFDs and PCAs of the normalized EFDs were conducted using the software SHAPE v. 1.367.

Data availability

The DAN5/P1 fossils are curated at the National Museum of Ethiopia (accession code: DAN5/P1). The original surface renderings and 3D reconstruction of DAN5/P1 generated for this study are available under restricted access because additional permission must be obtained from the National Museum of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Heritage Authority (EHA, formerly ARRCH); data requests should be addressed to K.L.B., S.S., and M.J.R. (emails in Supplementary Note 5). Likewise, virtual reconstructions of KNM-ER 3733 generated for the current study and KNM-WT 15000 (published previously) are available by request from K.L.B. after receiving a data user agreement from the National Museums of Kenya. The virtual reconstruction of LES1 generated for the current study is available by request to K.L.B. after receiving permission from University of Witwatersrand. Scan data for other fossil hominins typically requires a data sharing agreement with the institution curating the original (or cast) of that fossil (listed in Supplementary Tables 1–3). Please contact K.L.B. (cranial analyses), S.F. (face analyses), or Y.K. (dental analyses) for more information (emails in Supplementary Note 5). The landmarks and dental dimensions generated in this study are available in the Supplementary Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kimbel, W. H., Johanson, D. C. & Rak, Y. Systematic assessment of a maxilla of Homo from Hadar, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 103, 235–262 (1997).

Villmoare, B. et al. Early homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia. Science 347, 1352–1355 (2015).

Suwa, G., White, T. D. & Howell, F. C. Mandibular postcanine dentition from the Shungura Formation, Ethiopia: crown morphology, taxonomic allocations, and Plio-Pleistocene hominid evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 101, 247–282 (1996).

Baab, K. L. Defining Homo erectus. In Handbook of Paleoanthropology Vol. III: Phylogeny of Hominids (eds Henke, W. & Tattersall, I.) 2189–2219 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015).

Leakey, M. G. et al. New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo. Nature 488, 201 (2012).

Spoor, F. et al. Reconstructed Homo habilis type OH 7 suggests deep-rooted species diversity in early Homo. Nature 519, 83 (2015).

Antón, S. C. Early Homo: Who, When, and Where. Curr. Anthropol. 53, S278–S298 (2012).

Antón, S. C., Potts, R. & Aiello, L. C. Evolution of early Homo: an integrated biological perspective. Science 345, 1236826 (2014).

Antón, S. C. The Middle Pleistocene record: on the ancestry of Neandertals, modern humans and others. In A Companion to Paleoanthropology (ed. Begun, D. R.) 497–516 (Wiley, 2013).

Bilsborough, A. & Wood, B. A. Cranial morphometry of early hominids: facial region. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 76, 61–86 (1988).

Rightmire, G. P. & Lordkipanidze, D. Comparisons of early Pleistocene skulls from East Africa and the Georgian Caucasus: evidence bearing on the origin and systematics of genus Homo. In The First Humans–Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo (eds Grine, F. E., Fleagle, J. G. & Leakey, R. E.) 39–48 (Springer, 2009).

Wood, B. A. Koobi Fora Research Project: Hominid Cranial Remains. Vol. 4 (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Hammond, A. S. et al. New hominin remains and revised context from the earliest Homo erectus locality in East Turkana, Kenya. Nat. Commun. 12, 1939 (2021).

Herries, A. I. R. et al. Contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and early Homo erectus in South Africa. Science 368, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw7293 (2020).

de Lumley, M.-A. & Lordkipanidze, D. L’Homme de Dmanissi (Homo georgicus), il y a 1810000 ans. Comptes Rendus Palevol 5, 273–281 (2006).

Rightmire, G. P., Lordkipanidze, D. & Vekua, A. Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia. J. Hum. Evol. 50, 115–141 (2006).

Baab, K. L., Rogers, M., Bruner, E. & Semaw, S. Reconstruction and analysis of the DAN5/P1 and BSN12/P1 gona early Pleistocene Homo fossils. J. Hum. Evol. 162, 103102 (2022).

Bruner, E., Holloway, R., Baab, K. L., Rogers, M. J. & Semaw, S. The endocast from Dana Aoule North (DAN5/P1): a 1.5 million year-old human braincase from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 181, 206–215 (2023).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Primitive dentognathic morphology of Javanese Homo erectus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 36, 125 (2003).

Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Martinón-Torres, M., Sier, M. J. & Martín-Francés, L. On the variability of the Dmanisi mandibles. PLoS ONE 9, e88212 (2014).

Semaw, S. et al. Co-occurrence of Acheulian and Oldowan artifacts with Homo erectus cranial fossils from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw4694 (2020).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Taxonomic affinities and evolutionary history of the early Pleistocene hominids of Java: dentognathic evidence. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 128, 709–726 (2005).

Lautenschlager, S. Reconstructing the past: methods and techniques for the digital restoration of fossils. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 160342 (2016).

Kimbel, W. H., White, T. D. & Johanson, D. C. Cranial morphology of Australopithecus afarensis: a comparative study based on a composite reconstruction of the adult skull. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 64, 337–388 (1984).

Franciscus, R. G. & Trinkaus, E. Nasal morphology and the emergence of Homo erectus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 75, 517–527 (1988).

Laird, M. F. et al. The skull of Homo naledi. J. Hum. Evol. 104, 100–123 (2017).

Rightmire, G. P., Ponce de León, M. S., Lordkipanidze, D., Margvelashvili, A. & Zollikofer, C. P. E. Skull 5 from Dmanisi: descriptive anatomy, comparative studies, and evolutionary significance. J. Hum. Evol. 104, 50–79 (2017).

Walker, A. C. & Leakey, R. E. F. The skull. In The Nariokotome Homo erectus Skeleton (eds Walker, A. L. & Leakey, R. E. F.) 63–94 (Harvard University Press, 1993).

Clarke, R. J. A Homo habilis maxilla and other newly-discovered hominid fossils from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. J. Hum. Evol. 63, 418–428 (2012).

Huguet, R. et al. The earliest human face of Western Europe. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08681-0 (2025).

Rightmire, G. P. The Evolution of Homo erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Baab, K. L. The role of neurocranial shape in defining the boundaries of an expanded Homo erectus hypodigm. J. Hum. Evol. 92, 1–21 (2016).

Trauth, M. H. et al. Human evolution in a variable environment: the amplifier lakes of Eastern Africa. Quatern Sci. Rev. 29, 2981–2988 (2010).

Bobe, R. & Carvalho, S. Hominin diversity and high environmental variability in the Okote Member, Koobi Fora Formation, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 126, 91–105 (2019).

Wood, B. Human evolution: fifty years after Homo habilis. Nature 508, 31–33 (2014).

Potts, R., Behrensmeyer, A. K., Deino, A., Ditchfield, P. & Clark, J. Small mid-pleistocene hominin associated with East African Acheulean technology. Science 305, 75–78 (2004).

Antón, S. C. The face of olduvai hominid 12. J. Hum. Evol. 46, 335–345 (2004).

Spoor, F. et al. Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya. Nature 448, 688–691 (2007).

Tappen, M., Bukhsianidze, M., Ferring, R., Coil, R. & Lordkipanidze, D. Life and death at Dmanisi, Georgia: taphonomic signals from the fossil mammals. J. Hum. Evol. 171, 103249 (2022).

Pontzer, H., Scott, J. R., Lordkipanidze, D. & Ungar, P. S. Dental microwear texture analysis and diet in the Dmanisi hominins. J. Hum. Evol. 61, 683–687 (2011).

Lordkipanidze, D. et al. A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science 342, 326 (2013).

Elliott, M., Kurki, H., Weston, D. A. & Collard, M. Estimating fossil hominin body mass from cranial variables: an assessment using CT data from modern humans of known body mass. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 154, 201–214 (2014).

Simpson, S. W. et al. A female Homo erectus pelvis from Gona, Ethiopia. Science 322, 1089–1092 (2008).

Pontzer, H. Ecological energetics in early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53, S346–S358 (2012).

Dennell, R. & Roebroeks, W. An Asian perspective on early human dispersal from Africa. Nature 438, 1099–1104 (2005).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Cranial Morphology and Variation of the Earliest Indonesian Hominids. In Asian Paleoanthropology, 143–157 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2011).

Berger, L. R. et al. Homo naledi a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber South Africa. eLife 4, e09560 (2015).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Craniofacial morphology of Homo floresiensis: description, taxonomic affinities, and evolutionary implication. J. Hum. Evol. 61, 644–682 (2011).

Schlager, S., Profico, A., Di Vincenzo, F. & Manzi, G. Retrodeformation of fossil specimens based on 3D bilateral semi-landmarks: Implementation in the R package “Morpho”. PLOS ONE 13, e0194073-10 (2018).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2023).

Baab, K. L. A fresh look at an iconic human fossil: Virtual reconstruction of the KNM-WT 15000 cranium. J. Hum. Evol. 202, 103664-10 (2025).

Wiley, D. F. et al. Evolutionary morphing. In IEEE Visualization Conference 1–8 (IEEE, Minneapolis, MN, 2005).

Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R (Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, 2025).

Schlager, S. Morpho and Rvcg – shape analysis in R: R-packages for geometric morphometrics, shape analysis and surface manipulations. In Statistical Shape and Deformation Analysis (eds Zheng, G., Li, S. & Szekely, G.) 217–256 (2017).

Adams, D., Collyer, M., Kaliontzopoulou, A. & Baken, E. Geomorph: Software for Geometric Morphometric Analyses v. R package version 4.0.10. https://cran.r-project.org/package=geomorph (2025).

Baken, E. K., Collyer, M. L., Kaliontzopoulou, A. & Adams, D. C. geomorph v4.0 and gmShiny: enhanced analytics and a new graphical interface for a comprehensive morphometric experience. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2355–2363 (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2016).

Gunz, P., Mitteroecker, P., Neubauer, S., Weber, G. W. & Bookstein, F. L. Principles for the virtual reconstruction of hominin crania. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 48–62 (2009).

Hanegraef, H., David, R. & Spoor, F. Morphological variation of the maxilla in modern humans and African apes. J. Hum. Evol. 168, 103210-10 (2022).

Collyer, M. L. & Adams, D. C. RRPP: Linear Model Evaluation with Randomized Residuals in a Permutation Procedure. R package version 2.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RRPP (2024).

Collyer, M. L. & Adams, D. C. RRPP: an R package for fitting linear models to high-dimensional data using residual randomization. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 1772–1779 (2018).

McNulty, K. P., Frost, S. R. & Strait, D. S. Examining affinities of the Taung child by developmental simulation. J. Hum. Evol. 51, 274–296 (2006).

Aiello, L. C. & Wood, B. A. Cranial variables as predictors of hominine body mass. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 95, 409–426 (1994).

Grabowski, M., Hatala, K. G., Jungers, W. L. & Richmond, B. G. Body mass estimates of hominin fossils and the evolution of human body size. J. Hum. Evol. 85, 75–93 (2015).

Irish, J. D., Hemphill, B. E., de Ruiter, D. J. & Berger, L. R. The apportionment of tooth size and its implications in Australopithecus sediba versus other Plio-pleistocene and recent African hominins. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 161, 398–413 (2016).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Descriptions of the dental remains of Homo floresiensis. Anthropol. Sci. 123, 129–145 (2015).

Iwata, H. & Ukai, Y. SHAPE: a computer program package for quantitative evaluation of biological shapes based on elliptic Fourier descriptors. J. Heredity 93, 384–385 (2002).

Massicotte, P. & South, A. rnaturalearth: World Map Data from Natural Earth. R package version 1.1.0.9000. https://docs.ropensci.org/rnaturalearth/ (2025).

Holloway, R. L., Broadfield, D. C. & Yuan, M. S. The Human Fossil Record: Brain Endocasts - The Paleoneurological Evidence, Vol. 3 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004).

Kaifu, Y. et al. Unique dental morphology of Homo floresiensis and its evolutionary implications. PLoS ONE 10, e0141614 (2015).

Benazzi, S., Gruppioni, G., Strait, D. S. & Hublin, J.-J. Technical note: virtual reconstruction of KNM-ER 1813 Homo habilis cranium. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 153, 154–160 (2014).

Tobias, P. V. Olduvai Gorge. Vol. 4: The Skulls, Endocasts and Teeth of Homo habilis (Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Neubauer, S. et al. Reconstruction, endocranial form and taxonomic affinity of the early Homo calvaria KNM-ER 42700. J. Hum. Evol. 121, 25–39 (2018).

Brown, B. & Walker, A. The dentition. In The Nariokotome Homo erectus Skeleton (eds Walker, A. & Leakey, R.) 161–194 (Springer-Verlag, 1993).

Vekua, A. et al. A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Science 297, 85–89 (2002).

Martinón-Torres, M. et al. Dental remains from Dmanisi (Republic of Georgia): morphological analysis and comparative study. J. Hum. Evol. 55, 249–273 (2008).

Weidenreich, F. Giant early man from Java and south China. Anthropol. Pap. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 40, 1–143 (1945).

Kaifu, Y. et al. New reconstruction and morphological description of a Homo erectus cranium-Skull IX (Tjg-1993.05) from Sangiran, Central Java. J. Hum. Evol. 61, 270–294 (2011).

Rightmire, G. P. The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene?. J. Hum. Evol. 31, 21–39 (1996).

Woodward, A. S. A new cave man from Rhodesia, South Africa. Nature 108, 371–372 (1921).

Hawks, J. et al. New fossil remains of Homo naledi from the Lesedi Chamber, South Africa. eLife 6, e24232 (2017).

de Ruiter, D. J. et al. Homo naledi cranial remains from the Lesedi chamber of the rising star cave system, South Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 132, 1–14 (2019).

Kubo, D., Kono, R. T. & Kaifu, Y. Brain size of Homo floresiensis and its evolutionary implications. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 280, 20130338 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The Gona research permit was issued by the EHA, and the National Museum, Ministry of Tourism of Ethiopia, and the Afar State. Continuous major awards and grants were made by the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation to S.S. and M.J.R. to support the Gona Project. Additional funding was provided by the EU Marie Curie (FP7-PEOPLE-2011- CIG), and the Ministry of Science & Innovation, Spain through MINECO (HAR2013-41351-P), PALEOAFRICA (PGC2018-095489-B-I00), “GONAH” (HAR2013-41351-P), and the ACHEULOAFRICA (HAR2013-41351-P) projects to S.S. The Wenner-Gren Foundation, the National Science Foundation (SBR-9910974 and RHOI BCS-0321893 to T. White and F.C. Howell), and the National Geographic Society provided partial funding for the Gona Project. Additional funding was provided by Connecticut State University-AAUP Faculty Research grants to M.J.R. We are grateful for project infrastructure support provided by the John and Lois Rogers Trust to S.S. and M.J.R. The hard work of colleagues is acknowledged & the help of Afar colleagues, and assistants from Addis is appreciated. We thank Monica Castro for assistance with the segmentation of CT data and the many colleagues and institutions that allowed access to invaluable fossil and comparative data. Thanks to Jesse Martin for sharing surface scan data with us. Thanks to Gen Suwa for taking photographs of the DAN5/P1 fossils and Hyunwoo Jung for surface scanning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L.B., Y.K. and S.F. designed the research. S.S. and M.J.R. contributed to fossil discovery. K.L.B. and S.F. analyzed the cranial data. Y.K. analyzed the dental data. K.L.B., Y.K. and S.F. wrote the manuscript. S.S. and M.J.R. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Aida Gomez-Robles who co-reviewed with Siri Olsen; and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baab, K.L., Kaifu, Y., Freidline, S.E. et al. New reconstruction of DAN5 cranium (Gona, Ethiopia) supports complex emergence of Homo erectus. Nat Commun 16, 10878 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66381-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66381-9