Abstract

Non-equilibrium plasma-assisted ammonia synthesis is investigated through enhanced active species production with ferroelectric discharge. Time-resolved in-situ diagnostics of femtosecond two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering, and laser absorption spectroscopy, as well as optical emission spectroscopy, were conducted to probe the key intermediate species, such as H and N radicals as well as N2(ν), ions, and NH3 to achieve better understanding of non-equilibrium energy transfer and ammonia formation. The results reveal that ferroelectric discharge improved ammonia yield by four times. Results also show that ferroelectrics not only enhanced ions (N2+) production, radicals (N, H) number density, but also increased the N2 vibrational temperature. Further plasma modeling identified the couplings between elevated radical and ion production and enhanced vibrational excitation reactions, e.g., N + H2(ν)→NH + H, N2(ν)+H → NNH, N2+ + H2 → H + N2H+, and N2H++e→NH + N, facilitated by ferroelectric discharge. These findings provide critical insight into the mechanism of ferroelectric plasma catalysis and highlight their potential in advancing energy-efficient chemical synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-equilibrium plasma catalysis powered by renewable electricity is emerging as a promising strategy for green and efficient manufacturing by enabling new reaction pathways compared to conventional high-temperature equilibrium processes. Plasma technologies have demonstrated great potential in fields such as catalysis1, material synthesis2, combustion3,4, etc. Non-equilibrium plasmas produce excited species, radicals, as well as space and surface charges, which lower kinetic barriers and facilitate chemical reactions across gas-liquid-solid interfaces—often at reduced temperatures5. Despite its advantages, low-temperature plasma manufacturing faces several challenges. Firstly, the complexity of plasma chemistry, characterized by numerous types of reactive species and competing reaction pathways, hinders the kinetic understanding of the mechanism of plasma-assisted chemical synthesis. Additionally, the conversion efficiency of low-temperature plasma processes remains significantly lower than that of the conventional high-temperature methods. For example, plasma-assisted catalysis produces only 15-30 g of NH3 per kWh of energy input6, compared to 500 g-NH3/kWh for the Haber-Bosch process7. Therefore, a new method to control plasma generation and chemistry is needed.

In terms of plasma chemistry, vibrationally excited species, radicals, and ions are all believed to play critical roles in plasma-assisted ammonia synthesis, as supported by experimental and computational studies. Vibrationally excited nitrogen, N2(ν), is expected to enhance the dissociative adsorption rate on catalyst surfaces, thereby generating more adsorbed nitrogen species compared to ground-state N28,9. Adamovich et al. further demonstrated that applying a sub-breakdown radio frequency (RF) waveform alongside nanosecond discharges increased the vibrational temperature of N2, correlating with higher ammonia yields10. Complementary to this, Koel and Sundaresan’s parametric analysis showed that copious amounts of N2(ν) lead to markedly higher dissociative adsorption rates on catalytic metal surfaces11. On the other hand, although N and H radicals are present in relatively small quantities due to their high formation energy, their high reactivity enables them to directly participate in surface reactions, enhancing overall reaction rates and unlocking alternative pathways8. Bruggeman and Bhan12 highlighted the importance of radicals by demonstrating that surface reactions enable higher and more selective conversion to NH3 than gas-phase reactions alone and H is required to produce NH3. On the ionic side, Carrasco et al13. mapped the dominant ion-molecule channels in low-pressure H2/N2 plasmas and showed that reactions initiated by N2+ and H3+ (formed rapidly from H2+) efficiently supply NH/NH2 precursors that accelerate NH3 formation. However, simultaneous in-situ diagnostics of H, N, and N2(ν) in non-equilibrium plasma synthesis of ammonia are rarely conducted.

To promote efficient plasma-surface interaction and control plasma chemistry, recent efforts have focused on integrating ferroelectric materials, which possess spontaneous electric polarization and strong surface charge production. Studies on ferroelectric packed-bed plasma-catalytic systems for ammonia synthesis have demonstrated both higher efficiency and improved yields14,15. However, the fundamental properties and kinetics of ferroelectric barrier discharges (FBD) remain insufficiently explored. Existing investigations have primarily focused on the electrical behavior16,17 and spatial discharge patterns18 within FBD plasmas, leaving a knowledge gap in understanding the connections between ferroelectric polarization and plasma chemistry. Gómez—Ramírez et al19. explored how ammonia synthesis efficiency and certain electronically excited plasma species—mainly N2*, N*, NH* and N2+* (*denotes electronically excited states)—respond to applied voltage and frequency, electrode gap, and the type of ferroelectric material. However, due to the constraint of the packed bed geometry, their analysis primarily targeted the overall process performance without resolving the transient kinetics of radicals or vibrationally excited species. Notably, our previous study has reported that ferroelectric polarization-induced surface charges significantly enhance the electric field during N2 gas breakdown and prolong the afterglow period20, suggesting the potential for further improving plasma-assisted chemical manufacturing. However, although ferroelectric barrier discharges’ properties are significantly different from those of normal DBD, critical investigations into time-sensitive plasma chemistry, specifically regarding radicals and vibrational excited species for ammonia synthesis, are still lacking. These open questions continue to hinder the development of FBD plasma manufacturing.

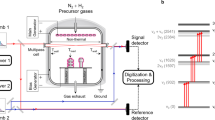

This work advances the fundamental understanding of N2/H2 ferroelectric barrier discharges by using advanced time-resolved laser diagnostics to capture the instantaneous evolution of plasma chemistry of radicals and vibrationally excited states. Ferroelectric polarization and surface charge behavior are directly correlated with the production dynamics of key active species, including ground-state radicals, ions and vibrationally excited molecules. It is demonstrated that N2/H2 FBDs generate significantly higher surface charge densities—on the order of 10-1 µC cm-2—exceeding those of conventional dielectric barrier discharges by at least an order of magnitude. To examine the ion production in FBD and Al2O3 DBD, we performed optical emission spectroscopy (OES) measurements. To quantify radical productions, vibrational excitations and ammonia synthesis, we employed time-resolved in-situ diagnostics: femtosecond two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence (fs-TALIF) for N and H radicals, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) for N2(ν), and laser absorption spectroscopy (LAS) for NH3. It is found that the production of NH3, as well as N and H radicals and ions (N2+*), is significantly promoted. The high electric field induced by the high surface charge from the ferroelectrics promotes both N and H radical peak number densities by at least a factor of two. Additionally, results also show that the vibrational excitation of N2 is enhanced in FBD, and it shows the vibrational temperatures of 1595 K and 885 K for pure N2 and N2/H2 mixtures in FBD, while no detectable bands of ν ≥1 could be seen in Al2O3 DBD. Parametric investigations of active species generation and NH3 production in FBD and Al2O3 DBD with different flow rates and N2/H2 ratios further confirm the generality of these trends. Further plasma kinetic modeling highlights the critical role of coupling reactions between radicals and vibrationally excited species—such as N + H2(ν)→NH + H, N2(ν)+H → NNH—in the reaction network. Ion chemistry featuring N2+, H2+ and N2H+ could also be a major contributor, with its prominence increasing at higher E/N as ionic pathways become more active. These findings reinforce the conclusion that the synergy among elevated radical and ion production, enhanced vibrational excitation, and potential plasma-surface interactions mediated by ferroelectric polarization fundamentally alters plasma kinetics and facilitates low-temperature plasma-driven chemical reactions. Our study delves into the plasma chemistry of ferroelectric barrier discharge, providing a deeper understanding of its underlying science, and facilitating its application in plasma-assisted processes.

Results

Surface charge generation using a lead zirconate titanate (PZT) barrier

As illustrated in Fig. 1a, a ferroelectric barrier discharge is established by incorporating a lead zirconate titanate (PZT) layer to induce rapid electric polarization and generate a large surface charge, therefore enabling control over plasma properties and manipulation of plasma chemistry. For comparison, a conventional dielectric barrier discharge is also constructed by replacing the PZT layer with an alumina (Al2O3) layer of identical dimensions. In both FBD and Al2O3 DBD configurations, the plasma is generated in a plate-to-plate arrangement between two parallel electrodes. Further details regarding the plasma cell design and operational conditions are provided in the Methods section and in our previous study20.

a Cell design. Two plate electrodes are placed in parallel. Because of the enlarged electric field and increasing density of electrons induced by the large surface charge from ferroelectric material, more active species, including radicals and excited molecules, are produced in plasma (Colored spheres denote different species; sizes and separations are not to scale, and the arrangement is illustrative rather than a crystallographic structure). b, c X-ray diffraction patterns of the lead zirconate titanate (PZT) plate and alumina plate, respectively, used in this work. Good consistency with database lines confirms the high purity and good crystallinity of the materials. d–f Surface charge measurements in (d) pure N2, (e) 25%N2/75%H2 and (f) pure H2 (Shaded band: min–max envelope across 10 measured cycles). The maximum surface charges (Q) of FBD are higher than those of Al2O3 DBD. The Q (Ucell) plot is directly measured by placing a reference capacitor in series with the plasma reactor.

The ferroelectric lead zirconate titanate used in this study is a ceramic perovskite material that exhibits a tetragonal P4mm crystal structure (below its Curie temperature). This asymmetric crystal structure results in the displacements of positive and negative charge centers within the unit cell and equips PZT with inherent spontaneous polarization. In contrast, alumina (α-Al2O3) employed in the dielectric barrier discharge possesses a hexagonal corundum structure with the space group \({{\rm{R}}}\bar{3}{{\rm{c}}}\) (no. 167), leaving no spontaneous polarization. The X-ray diffraction patterns of the lead zirconate titanate plate and alumina plate used in this work confirm the high purity and crystallinity of the materials, as shown in Fig. 1(b) and (c). To ensure optimal ferroelectric performance in the FBD configuration, the PZT plate is supplied in a fully poled and application-ready state as explained in the Methods section.

To enable in-situ quantification and comparison of surface charge generation in ferroelectric barrier discharge and dielectric barrier discharge, we adopt the Sawyer-Tower method21. Further methodological details are provided in the Supporting Information Fig. S1 and in our previous work20. As illustrated in Fig. 1d–f, the ferroelectric PZT barrier accumulates significantly more surface charge than the dielectric alumina barrier across different gas mixtures. In pure N2 (Fig. 1d), the PZT induces a surface charge of 0.09 μC cm−2, whereas the Al2O3 DBD configuration yields a charge of two orders of magnitude lower, at ~10–4 μC cm−2. When 75% H2 is introduced into the gas mixture while maintaining constant pressure and total flow (Fig. 1e), the peak surface charge in the FBD increases to 0.15 μC cm−2. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the rise in electron temperature due to H2 addition22, which promotes the bombardment of energetic particles on the ferroelectric surface and consequently enhances secondary electron emission. The resulting elevated electron energy and density in FBD increase the likelihood of electron-molecule collisions, thereby generating more excited species (both electronic and vibrational) and ions compared to Al2O3 DBD. Additionally, differences in secondary electron emission can be influenced by the materials’ work functions: PZT has a slightly lower work function than alumina (4.5 eV vs. 4.7 eV)23,24. However, when switching to pure H2 (Fig. 1f), the peak surface charge drops to ~0.07 μC cm-2. This reduction is likely due to the non-monotonic behavior of secondary electron yield, which can decrease beyond a certain incident particle energy threshold25. In Al2O3 DBD, the peak surface charge in pure H2 (0.03 μC cm-2), as shown in Fig. 1(f), is noticeably higher than in pure N2 or N2/H2 mixture. This can be attributed to the distinct plasma properties of H2: its lower breakdown voltage and higher ion mobility facilitate more conductive discharge channels, which increase the displacement current and the total transferred charge per cycle26,27,28.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1d–f and Supporting Information Figure S2, the breakdown voltage of the ferroelectric barrier discharge increases with higher N2 concentrations in the gas mixture, in accordance with Paschen’s law29. Notably, when H2 is present, the voltage-charge loop exhibits distortions at both the left and right turning points of the curve. These irregularities are attributed to a voltage drop at the moment of gas breakdown, as evident in Supporting Information Figure S2. This voltage drop arises from an overshoot in the electric field and current, as well as the initiation of micro-discharges during breakdown events30.

Intensified ionization: increased N2 +*/N2* ratio in ferroelectric barrier discharge

In plasma-catalysis research, gas-phase ion chemistry plays a crucial role in reaction processes, not only by directly changing plasma properties but also via radical and intermediate species production. To compare the ion concentrations in FBD and Al2O3 DBD, OES measurements are performed, as shown in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2(a), the spectra display major nitrogen-related emission peaks corresponding to the second positive band N2(C3Πu-B3Πg) and the first negative band N2+(B2Σu+-X2Σg)31,32. In Fig. 2(b), the main observed features include the Balmer-α and Balmer-β atomic hydrogen lines33,34.

OES spectra of FBD and Al2O3 DBD showing (a) nitrogen-related species and (b) hydrogen-related species. Note that panels (a) and (b) use different intensity scales (with b enlarged for clarity), while spectra within each panel share the same scale for vertical comparison. The FBD consistently exhibits higher emission intensities compared to the Al2O3 DBD, particularly for excited molecules and radicals. More importantly, the ionization processes in FBD are significantly enhanced, leading to a greater presence of ionized species, such as N2+*, which are key intermediates in plasma-assisted reactions. This enhancement is attributed to the large electric field present in the ferroelectric barrier discharge, facilitating ionization and promoting a higher density of reactive ions.

The results show that under identical gas compositions, the FBD consistently produces stronger emissions than Al2O3 DBD, including emissions from excited molecules and radicals, but more importantly from different ions. This enhancement is likely due to the higher local electric field and stronger electron acceleration capability in FBD, which leads to higher average electron energies and, consequently, increased electron-impact ionization cross-sections and frequencies. However, an interesting phenomenon was observed: in N2/H2 mixtures, the intensity ratio of N2+* to excited N2* is higher compared to pure N2. To illustrate this more clearly, the peak areas are integrated, as shown in Table 1. The numerical results are consistent with the spectral trends: FBD always gives higher intensities than Al2O3 DBD, and the addition of H2 markedly increases the N2+*/N2* ratio, with the effect being more pronounced in FBD. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S3 and Figure S4, even with different total flow rates (50 sccm and 100 sccm) and N2/H2 ratios (0%, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% N2), the conclusion of enhanced emissions in FBD and increased N2+*/N2* with H2 still holds. This may be attributed to changes in the electron energy distribution function upon H2 addition35, which increases the fraction of high-energy electrons and thus enhances N2 ionization, while the presence of H2 competes for excitation of N2, reducing the relative population of N2* and leading to a higher N2+*/N2* ratio.

Enhanced production of N and H radicals in ferroelectric barrier discharge

Interest in understanding the role of radicals in plasma-assisted ammonia synthesis continues to increase36,37. Figure 3a presents the absolute number densities of N radicals measured by fs-TALIF across different gas compositions in both FBD and Al2O3 DBD plasmas over a single voltage cycle. As shown in Fig. 3a, the time when the peak N radical densities occur coincides with the time at which the applied voltage drops, indicating that most N radicals are generated during gas breakdown. This phenomenon can be attributed to the overshoot of the electric field of FBD at breakdown, which provides sufficient energy for electron-impact dissociation of N2 molecules20. Given that the electric field in FBD is substantially higher than in Al2O3 DBD20, it is expected that the N radical densities in FBD are significantly enhanced compared to Al2O3 DBD. In pure N2, the peak N number density in FBD reaches 1.2 × 1016 cm-3, nearly double that of Al2O3 DBD (6.8 × 1015 cm-3). In N2/H2 mixtures, this difference becomes even more pronounced, with FBD exhibiting a peak value of 1.1 × 1016 cm-3, which is an order of magnitude higher than that of Al2O3 DBD (1.4 × 1015 cm-3). Moreover, the addition of H2 affects the two discharges differently: in FBD, the N radical peak density remains relatively unchanged, whereas in Al2O3 DBD, it drops significantly. This difference could be attributed to two possible mechanisms: (i) electron-impact dissociation of N2: due to the strong electric field induced by the ferroelectrics in different gas mixtures, the electron number density in FBD could remain high. While in Al2O3 DBD the electric field and electron number densities are lower and a portion of the electron energy could be diverted to dissociation of H2 (e + H2 → e + H + H) rather than generating N radicals which require higher energy thresholds38, or vibrational channels such as H2 + N2(ν2) → H2(ν1) + N239. (ii) additional ion-mediated pathways involving hydrogen species in FBD (will be discussed further in kinetics modelling in the last): in FBD, the sustained high E/N drives strong ionization, yielding abundant N2+, H2+ and their protonated products (e.g., N2H+). Consequently, with H2 added, N radicals are also supplied by ion-mediated pathways, most notably dissociative recombination (N2H++e→NH + N), so the net N production remains relatively stable to H2 addition. In contrast, in the Al2O3 DBD, the lower E/N and electron density reduce both ionization and ion-molecule reaction rate, leaving a negligible role of ions on the N production.

The time-dependent (a) N and (b) H radical number density measurements on FBD and Al2O3 DBD via TALIF diagnostic along the central line of plasma corresponding to the voltage waveform (share the same legends with TALIF results) measurement in different gases (Shaded band: uncertainty from laser-energy jitter). The large electric fields in FBD enhance the N production so that the N number density (nN) is increased by up to one order of magnitude compared to that in Al2O3 DBD. Similarly, the generation of H radicals in FBD increases by up to six times compared to Al2O3 DBD due to a higher electric field. Interestingly, in both FBD and Al2O3 DBD, the number densities of H radicals (nH) counterintuitively grow when N2 is added to H2, possibly because of new reaction pathways, e.g., H2(ν)+N → NH + H. The time-averaged number densities of (c) N and (d) H radicals over a complete voltage cycle, calculated as the integrals of the curves in (a) and (b) divided by the cycle period, demonstrate the enhanced radical generation in FBD.

Figure 3b shows the absolute number densities of H radicals in FBD and Al2O3 DBD plasmas under various gas compositions. Similar to the trend observed for N radicals, the generation of H radicals in FBD is significantly enhanced due to the higher electric field. In pure H2, the peak H radical density in FBD reaches 8.0 × 1016 cm−3, over six times greater than that in Al2O3 DBD (1.2 × 1016 cm−3). In N2/H2 mixtures, the FBD still maintains a notable advantage, with a peak value of 2.1 × 1017 cm−3, nearly double that of Al2O3 DBD (1.2 × 1017 cm−3). Interestingly, in both FBD and Al2O3 DBD, the H radical number density counterintuitively increases upon the moderate addition of N2 to H2. This unexpected behavior may be explained by additional H production pathways facilitated by nitrogen39, such as H2(ν)+N → NH + H and H2 + N2(*) → N2 + H + H, where vibrationally and electronically excited species, as well as direct electron collision in an enhanced electric field contribute to enhanced hydrogen dissociation. In addition, in FBD, ion chemistry could provide complementary sources of H. Charge transfer (N2+ + H2 → N2 + H2+) builds the H2+ pool; subsequent reactions directly and indirectly produce H radical via H2+ + H2 → H3+ + H, e + H2+ → H + H, and e + H3+ → H + H + H (or H2 + H). Recombination reaction of N2H+ with an electron also yields H. Because these ion-mediated pathways scale with ionization, they are far more prominent in the FBD than in the Al2O3 DBD and, together with the excited-species routes, rationalize both the higher H densities in FBD and the counterintuitive rise of H upon introducing N2. Therefore, in pure H2, the steady-state H radical density in Al2O3 DBD remains relatively low, despite the larger Q-Ucell figure area observed in Fig. 1f, without N2 to provide additional excitation channels or ionic pathways for H production.

As a complementary analysis, Fig. 3c, d present the time-averaged N and H radical number densities, respectively, obtained by integrating the transient curves in Fig. 3a, b over one voltage cycle and dividing by the cycle duration. In the N2/H2 mixture, the time-averaged nN in FBD (2.8 × 1015 cm−3) exceeds that in Al2O3 DBD (7.1 × 1013 cm−3) by over two orders of magnitude, while the average nH is almost two times higher (7.4 × 1016 cm−3 vs. 3.8 × 1016 cm−3). Importantly, the trends observed in these time-averaged values are consistent with those in the instantaneous profiles of Fig. 3a, b, reaffirming that both gas composition and discharge configuration have a strong and distinct influence on radical generation. Lastly, peak number densities of N and H radicals were measured across various N2/H2 ratios and total flow rates, as shown in Supporting Information Figure S5. FBD consistently yields more N and H than the Al2O3 DBD under all compositions and flow rates examined. The qualitative dependence on gas composition mirrors the trends discussed above and remains similar across different flow conditions. The only exception arises at very N2-rich mixtures (75% N2), where the H peak decreases, likely because reactive flux is diverted into N-containing pathways, and low availability of H2.

Enhanced production of vibrationally excited N2 in ferroelectric barrier discharge

Besides radicals such as N and H, vibrationally excited N2 has been attracting attention not only from its strong coupling with radical production, but also from its role in energy transfers in plasma-catalytic synthesis of NH3. The presence of vibrationally excited N2 can significantly influence key reaction pathways and enhance overall reaction efficiency. Therefore, quantitative measurements of vibrationally excited N2 temperatures are necessary for key reaction mechanisms and kinetic model validations in plasma-assisted ammonia synthesis.

With advances in laser sources and sensitive detectors, a wide range of laser diagnostics can now quantify vibrational temperatures in plasmas, including spontaneous Raman scattering40, mid-IR laser absorption spectroscopy41, and CARS42. Of these methods, CARS stands out as a powerful technique for plasma diagnostics, owing to its high spatial and temporal resolution. In addition, the coherent signal is less susceptible to plasma emission and improves the signal-to-noise ratio. These features make CARS particularly well-suited for in-situ vibrational and rotational temperatures measurements in plasmas.

To quantitatively measure the vibrational excitation of N2, we utilize a 3-beam fs/ps coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) system for vibrational and rotational temperature measurements43. Figure 4a shows the vibrational CARS spectra of N2 in both Al2O3 DBD and FBD plasmas under pure N2 and 25%N2/75%H2 gas mixtures. The central spectra represent averages over a complete applied voltage cycle (50 μs), while the time-resolved color-filled spectra on the left and right illustrate the temporal evolution of vibrational excitation. In pure N2 FBD, vibrational bands up to ν = 2 are clearly observed, and the spectral profile remains relatively stable throughout the voltage cycle, suggesting consistent vibrational energy distribution. Upon the introduction of H2, the intensity of the N2 hot bands decreases, and a distinct temporal window (12-20 μs) emerges in which the population of vibrationally excited N2(ν) drops significantly. This low vibrational temperature time window coincides with the peak H radical number densities observed in the 25% N2 / 75% H2 FBD case (as shown in Fig. 3a), implying that there is a strong energy transfer between vibrational N2(ν) and H2 during this period, thereby reducing vibrational excitation of N2 molecules. In contrast, vibrational N2(ν) levels of ν ≥ 1 are barely detectable in Al2O3 DBD under both gas compositions, indicating that the population of vibrationally excited N2(ν) is substantially lower in Al2O3 DBD than in FBD. This is likely due to the lower electron number density in dielectric barrier discharges, which limits the excitation of vibrational states compared to ferroelectric barrier discharges.

a Average throughout one complete applied voltage cycle (50 μs) and time-dependent vibrational Q-branch CARS spectra of N2 in FBD and Al2O3 DBD with and without H2 addition (Shaded band: uncertainty from laser-energy jitter). In FBD, N2 vibrational bands up to ν = 2 are observed while vibrational levels ν ≥1 are barely detectable in Al2O3 DBD. b Vibrational temperatures of N2(ν) in FBD. N2 vibrational temperature is lower in N2/H2 mixtures than in pure N2 since the addition of H2 enabled more energy transfer pathways. c Pure-rotational CARS spectra of N2 (averaged throughout one complete applied voltage cycle) in FBD and DBD with and without H2 addition. d Rotational temperatures of N2 in Al2O3 DBD and FBD calculated from pure-rotational N2 CARS spectra. The small variation in rotational temperatures indicates negligible influence of heating from vibrational-translational relaxation between N2(ν) and H2.

Based on the theory explained in Methods, vibrational temperatures of N2 are fitted from the collected spectra as shown in Supporting Information Figure S6. As shown in Fig. 4b, the average vibrational temperatures in FBD are 1595 K and 885 K for pure N2 and N2/H2 mixtures, respectively. These results indicate that the addition of H2 reduces the N2 vibrational temperature, likely due to the introduction of additional energy transfer pathways in the plasma. Furthermore, this observation is confirmed at different total flow rates and gas compositions as shown in Supporting Information Figure S7 and Figure S8. To rule out thermal heating as the source of elevated vibrational temperatures, pure-rotational N2 CARS spectra were collected, as shown in Fig. 4c, to assess the rotational temperature, which approximates the translational temperature. The rotational temperature is modelled by comparing the experimental spectra with theory through a least-squares fitting routine, as shown in Supporting Information Figure S9. As shown in Fig. 4d, the difference in rotational temperature between pure N2 and N2/H2 plasmas is minimal, below 5 K. Furthermore, the rotational temperature differences between FBD and Al2O3 DBD are also minor, within 20 K. These small variations confirm that vibrational excitation is not significantly influenced by gas heating, but rather governed by the plasma’s non-equilibrium excitation dynamics.

Promoted synthesis of NH3 in ferroelectric barrier discharge

Figure 5 compares the time-resolved NH3 production in FBD and DBD using a stoichiometric gas mixture of 25% N2 and 75% H2 at a constant flow rate and pressure of 10 Torr. The NH3 concentrations are measured via laser absorption spectroscopy. Two key observations emerge from the comparison: (i) the incorporation of a ferroelectric barrier significantly enhances the ammonia yield, reaching nearly four times the amount produced in Al2O3 DBD, and (ii) the time required to reach a steady-state NH3 concentration is extended in FBD. Specifically, the steady-state NH3 mole fraction increases from ~150 ppm in Al2O3 DBD to about 550 ppm in FBD. It is worth noting that this enhancement is not limited to this specific condition but is also observed across different total flow rates and mixture compositions, as shown in Supporting Information Figure S10. This enhancement is attributed to the increased production of reactive species—namely N radicals, H radicals, ions (e.g., N2+) and vibrationally excited N2 molecules—in the FBD system. Furthermore, the extended transient time to steady-state NH3 concentration, ~20 seconds in FBD compared to 9 seconds in Al2O3 DBD, suggests the involvement of surface reactions in addition to gas-phase plasma chemistry44. Although surface chemistry is not the primary focus of this study, this observation indicates a synergistic effect between plasma activation and the barrier surface, even in the absence of externally loaded catalysts such as Ni or Co15. Furthermore, to place our NH3 measurements in the context of the global effort to improve the energy efficiency of plasma-assisted ammonia synthesis45,46, they are benchmarked against representative studies as shown in Table 2. However, a strict like-for-like comparison is not intended: system in this work was purpose-built for time-resolved laser diagnostics, with a small discharge area, no catalyst packing, and a low operating pressure and temperature, prioritizing control and observability over throughput.

Gas phase mechanisms in ferroelectric barrier discharge

To gain further insight into the mechanisms underlying the enhanced production of active species and ammonia, plasma kinetic modeling was performed. The modeling results, summarized in Fig. 6, focus on the key gas-phase reaction pathways responsible for the generation of N and H radicals. In N2/H2 plasma, H radicals are primarily generated through direct electron impact dissociation and via collisional H2 quenching involving N2*. Similarly, N radicals are initially formed by electron impact dissociation of N2 and subsequently through radical reactions such as NH + H → N + H2. Consistent with findings from our previous work39, plasma reaction pathways involving vibrationally excited species - H2(ν) and N2(ν) - are identified as important contributors to the production and consumption of radicals, thereby influencing NH3 formation in both the gas phase and on catalyst surfaces. As shown in Fig. 6a and Fig. 6c, H2(ν2, ν3) actively participates in radical chemistry, which serves not only as a dominant N radical consumption source, but also contributes significantly to H radical production, highlighting the critical role of H2(ν) in driving gas-phase ammonia formation. Additionally, Fig. 6b and Fig. 6d illustrate that N2(ν) contributes to the formation of NNH via N2(ν)+H → NNH. NNH may then engage in surface-mediated reaction steps, facilitating NH3 production through interactions with catalytic sites47.

Besides the importance of vibrationally excited species, a comparison between Al2O3 DBD and FBD plasma kinetics reveals notable shifts in reaction pathways, particularly with respect to ion chemistry. In FBD, the higher reduced electric field20 leads to increased electron energy delivery, which significantly enhances the formation and participation of ions. As shown in Fig. 6d, ion-related pathways account for a significant fraction of H radical formation and removal. For instance, H2+ + H2 → H + H3+, H2+ + N2 → H + N2H+ and N2+ + H2 → H + N2H+ together contribute almost 35% of total H generation, a striking contrast to the negligible ion contribution observed in Al2O3 DBD. These pathways reflect the enhanced ionization environment facilitated by higher electron densities and energies in FBD. On the consumption side, H radicals are also actively depleted through charge-transfer or proton-transfer processes involving H+ and other ions. Together, these findings indicate that ionic reactions, both generative and consumptive, play dual roles in shaping the steady-state concentration of H radicals under high-E/N plasma regimes, making them indispensable components in the overall plasma chemical network.

For nitrogen-related chemistry, similar trends are observed. Ion-mediated reaction pathways become more prominent in FBD. For example, the dissociative recombination of N2H+ becomes a non-negligible contributor to N production in FBD, whereas it is nearly absent in Al2O3 DBD, as shown in Fig. 6c,a. This increase in ion participation again reflects the enhanced ionization and electron-impact reactivity under high electric field conditions.

Beyond N and H radicals, NH is also a key intermediate in ammonia synthesis, both in the gas phase and on catalytic surfaces. Path flux analysis of NH is presented in Supporting Information Figure S11. In FBD, the NH flux from N + H( + M) → NH( + M) reaction becomes more prominent, rising from 2.51% to 26.49%, and an additional NH source emerges via the electron-induced decomposition of N2H+, which is absent in Al2O3 DBD, as shown in Figure S11. Overall, the results indicate that FBD reshapes NH generation by enhancing N radical chemistry and introducing new ion-driven channels.

While N2(ν) appears to play a less significant role in gas-phase radical production compared to H2(ν), its potential for preferential adsorption on catalyst surfaces suggests a more influential role in surface reactions. For instance, N2(ν) could lower the apparent barrier for N-N bond cleavage and shift optimal catalysts toward metals that bind N weaklier9. While surface reactions are not the primary focus of this study, surfaces could indeed influence the overall reaction pathways, particularly by serving as a third body (M) in three-body processes such as the hydrogenation of NH and NH2 radicals and changing the catalytic reaction pathways via surface nitridation48. In conventional gas-phase three-body reactions (e.g., NH + H + M → NH2 + M in Fig. 6b and Fig. 6d), the third body stabilizes the product by dissipating excess energy. Analogously, solid surfaces can act as energy sinks, enabling recombination or hydrogenation reactions. The synergistic interactions between plasma-generated species and surface adsorption processes may play a non-negligible role, especially in enhancing the utilization of short-lived intermediates like NH and NH2. Therefore, further studies are necessary to explain the mechanisms by which ferroelectric materials influence surface catalytic behavior, and to better understand their synergistic contributions to NH3 synthesis.

To summarize, this work demonstrates that the incorporation of a ferroelectric barrier into a non-equilibrium N2/H2 plasma discharge significantly increases the production of active radicals, ions, vibrationally excited nitrogen, and NH3. Results show that the PZT ferroelectric barrier discharge generates surface charge densities at least an order of magnitude greater than the conventional Al2O3 dielectric barrier discharges. OES measurements show that more ions (e.g., N2+*) are generated in FBD. In-situ, time-resolved measurements using fs-TALIF reveal that the ferroelectric barrier leads to N and H radical number densities up to ten times higher than those in Al2O3 DBD. CARS measurements indicate a drastic enhancement of the vibrational excitation of N2(ν) and the N2 vibrational temperature, with detectable populations up to ν = 2 and vibrational temperatures of 1595 K and 885 K for pure N2 and N2/H2 mixtures. In addition, laser absorption measurements reveal that nearly four times higher NH3 was produced in FBD relative to Al2O3 DBD under identical operating conditions. Parametric investigations over a broad range of mixture compositions and flow residence time further confirm the generality of the observed enhancements of active species generation and NH3 production in FBD compared to Al2O3 DBD. Complementary plasma kinetic modeling further reveals the importance of coupling reactions between radicals and vibrational excitation such as H2(ν)+N → NH + H, N2(ν)+H → NNH, and ion chemistry featuring N2+, H2+ and N2H+, supporting the conclusion that the synergy among elevated radical and ion production, enhanced vibrational excitation, and possible plasma-surface interactions facilitated by ferroelectric polarization plays a key role in modifying plasma kinetics and enabling low-temperature plasma reactions. These findings provide not only critical insight into the mechanisms of ferroelectric plasma-enhanced NH3 production, but also clear guidance on controlling non-equilibrium surface charge production, plasma chemistry, and active species for efficient plasma catalysis with ferroelectric materials.

Methods

Plasma discharge configuration

The plasma was generated in a plate-to-plate configuration as shown in Fig. 1a. Both the ferroelectric lead zirconate titanate (Pb(ZrxTi1-x)O3) from Steiner & Martins, Inc., and the dielectric Al2O3 from McMaster-Carr were processed to the dimensions of 4.5 cm × 1.7 cm × 0.12 cm. These two electrodes were separated by a 5 mm gap and enclosed in a 110 mm-long, 24 mm × 11 mm rectangular quartz channel with a wall thickness of 2 mm. In all in-situ diagnostic experiments, both ferroelectric barrier discharge and dielectric barrier discharge were operated using an AC power supply (PVM500/DIDRIVE10, Amazing1) at a frequency of 20 kHz and an applied voltage of 2.6 kV (peak to peak). Nitrogen and hydrogen gases (99.9999%, Airgas USA, LLC) flowed into the quartz cell with a fixed residence time of 0.05 seconds (i.e., 100 sccm total flow rate unless otherwise labeled) between the electrodes at a pressure of 10 torr. For the N2/H2 mixture, the ratio between N2 and H2 is 1:3 (i.e., 25% N2 plus 75% H2) unless otherwise labeled.

To ensure optimal ferroelectric performance in the FBD configuration, the PZT plates are pre-poled prior to operation. According to the manufacturer and standard industrial practice, ferroelectric poling is performed along the thickness direction by applying a high DC electric field at elevated temperature. Standard poling protocols involve heating the ceramic to approximately 100–150 °C (below the Curie temperature 320 °C), immersing it in a dielectric medium such as silicone oil, and applying a DC electric field of 2–4 kV/mm for 10–30 minutes. The field is maintained during cooling to stabilize the spontaneous polarization along the applied axis, thereby ensuring long-range dipole alignment and stable macroscopic response. While the exact parameters are proprietary and not disclosed by the manufacturer, the product is supplied in a fully poled and application-ready state. In this work, all experiments were conducted using the same factory-poled ceramic plate, with no post-processing applied. This uniformity guarantees that all data reflect consistent material conditions and that observed performance trends derive solely from reactor design and operating parameters, not from variability in polarization state.

Electrical measurements

A reference capacitor, Cref = 10 nF (Digi-Key, 399-12395-ND), is placed in series with the plasma cell. The applied voltage Ucell and the voltage drop across the reference capacitor Uref are monitored using two high-voltage probes (Tektronix, P6015A) connected to a digital oscilloscope (Tektronix, TDS 2012B). The total current through the plasma, including any parallel parasitic components, is monitored using a current monitor (Pearson 6585). The equivalent circuit of the system and detailed explanation can be found in our previous work20.

Two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence (TALIF)

Figure 7a shows the experimental setup of in-situ femtosecond two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence (fs-TALIF) for detecting H and N radicals in a ferroelectric barrier discharge. This setup consists of a femtosecond (fs) laser system, an FBD plasma system, and an ICCD camera with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 50 mm lens. The fs laser system consists of a Ti:sapphire oscillator, an ultrafast amplifier, and an optical parametric amplifier (OPA). The OPA (TOPAS NIRUVIS, Light Conversion) outputs UV fs laser pulses with a pulse energy of ~3.7 μJ for H and ~2.7 μJ for N at central wavelengths around 205.1 nm (theoretically at 205.08 nm) for H and 206.7 nm (theoretically at 206.65 nm) for N at 1 kHz via a series of nonlinear optical processes, including second-harmonic generation and sum-frequency generation. The fs laser beam is focused into a rectangular FBD plasma reactor, and excites the 1 s 2S1/2 → 3 d 2D3/2,5/2 transition of the H radical (or the 2p3 4S3/2 → 3p 4S3/2 transition of the N radical)49. The H fluorescence signal at 656.3 nm and the N fluorescence signal at 742–746 nm are separately imaged by an ICCD camera (Princeton Instruments PIMAX-4). For H fluorescence, a bandpass filter with a full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of 10 nm centered at 656 nm is applied in front of the camera lens to block any laser scatter and plasma emissions, while for N fluorescence, a bandpass filter centered at 745 nm with 10 nm FWHM is used. The intensified camera with a 110 ns gate is synchronized with the laser using control electronics to enable time-resolved measurement during a single voltage cycle.

Before using fs-TALIF to study the impact of the ferroelectric discharge on plasma chemistry, we validate the quadratic relationship between the signal and the laser pulse energy. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S12, we plotted the fs-TALIF signal as a function of the square of pulse energy. The fs-TALIF signal of N follows a quadratic relationship with the laser pulse energy under 2.9 μJ. The fs-TALIF signal of H also follows a quadratic relationship with the laser pulse energy under 4.1 μJ. These quadratic relationships validate that our fs-TALIF measurements have negligible photolytic and stimulated emission interferences.

To obtain the absolute concentrations of H and N radicals, the TALIF measurements are calibrated using the same pressure Kr-TALIF measurements, since H, N, and Kr have similar excitation wavelengths with minor changes39. The absolute density of the target species (denoted as Ni) is determined by comparing to the known number density of the calibration Kr (NKr) as follows50,

where \(\eta\) is the quantum efficiency of the camera, \(T\) is the transmission of the signal collection optics at the fluorescence wavelength, \({a}_{2\to 3}=\frac{{A}_{2\to 3}}{{A}_{2}+{{\rm{Q}}}}\) is the fluorescence quantum yield where \({{{\rm{A}}}}_{2\to 3}\) is the Einstein coefficient, \({A}_{2}\) and \(Q\) are the spontaneous emission rate and collisional quenching rate, respectively, and \({A}_{2}+Q=\frac{1}{\tau }+{\sum }_{{{\rm{q}}}}{k}_{{{\rm{q}}}}{n}_{{{\rm{q}}}}\) where \(\tau\) is the natural lifetime of the species. In addition, \({k}_{{{\rm{q}}}}\) is the quenching coefficient of the collisional partner with \({{\rm{q}}}\) taken to be the major species N2 and/or H2, and \({n}_{{{\rm{q}}}}\) is the number density of the collisional partner calculated based on the ideal gas law with the approximate mole fractions. \({\int }_{0}^{\infty }{I}^{2}({{\rm{t}}}){{\rm{dt}}}\) is proportional to the square of the used laser pulse energy, \({\nu }_{0}\) is the central wavelength of the excitation laser, \({\sigma }^{(2)}\) is the two-photon absorption cross section, \(g(\delta \nu )\) is the normalized two-photon absorption line profile, and \({S}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\) is measured fluorescence signal. The above calibration parameters are listed in the Supporting Information Table S1.

Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS)

Hybrid fs/ps coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (fs/ps CARS) is a nonlinear spectroscopic technique that provides spatially and temporally resolved vibrational and rotational temperature measurements in non-equilibrium plasmas. In hybrid fs/ps CARS, two broadband fs pulses (pump and Stokes) cover a broad range of Raman transitions in the target molecule. A narrowband ps probe pulse scatters off the excited Raman coherence and the CARS signal is generated through the nonlinear four-wave mixing process. The non-resonant background is minimized by introducing a time delay to the probe pulse. In our 3-beam hybrid fs/ps CARS system, the vibrational N2 Raman transitions are targeted by the 675 nm and 800 nm pulses. Due to the broadband nature of the fs pulses, the 800 nm pulse is able to effectively excite the pure-rotational N2 Raman coherence. The 400 nm probe pulse samples both the vibrational and pure-rotational Raman coherence simultaneously, and a bandpass filter is used to separate the probe pulse from the CARS signal. A grating-based spectrometer is used to differentiate the vibrational and pure-rotational CARS signal.

The CARS signal intensity is modeled as the square magnitude of the product between the probe electric field (Epr) and the combined resonant (Pres) and non-resonant (Pnres) polarizations43,

where Pnres is modeled as the product between the pump electric field and the complex conjugate of the Stokes electric field (\({{{\bf{E}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{*}\)). The resonant polarization can be expressed as43,51

where \({\tau }_{12}\) is the time delay between the pump and Stokes beams, \({\tau }_{23}\) is the time delay between the Stokes and probe beams, and \({R}_{{{\rm{CARS}}}}\) is the molecular response function. The N2 Q-branch vibrational molecular response function is defined as52,

where \({\omega }_{{{\rm{\upsilon }}},{{\rm{J}}};{{\rm{v}}}+1,{{\rm{J}}}}\) is the transition frequency, \({\varGamma }_{{{\rm{\upsilon }}},{{\rm{J}}};{{\rm{v}}}+1,{{\rm{J}}}}\) is the Raman linewidth, \(\upsilon\) is the vibrational quantum number, and J is the rotational quantum number. The Boltzmann-weighted Raman transition intensity \({I}_{\upsilon,{J;}{\nu }+1,J}\) is defined as53,

where \({a}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) are the Raman polarizability tensor invariants, \(F(J)\) is the Herman-Wallis factor, and \({b}_{J{J}^{{\prime} }}\) is the Placzek-Teller coefficient. It is worth noting that the Raman transition intensity scales with \({\nu }+1\). The N2 S-branch pure-rotational molecular response function is defined in a similar way.

The vibrational and rotational temperatures are calculated from the experimental spectra by comparing with theory through least-squares curve fitting. First, 1000 laser shots were background-subtracted and averaged. The averaged spectrum was then divided by the non-resonant argon spectrum to correct for the Raman excitation efficiency at different wavelengths. The spectrometer grating and the camera’s quantum efficiency were also considered during data processing. For the spectral fitting process, a total of 7 parameters are determined with room temperature reference spectra. These parameters are: probe time delay, probe linewidth, non-resonant background scalar, non-resonant background phase shift, instrument width, and vertical and horizontal shift. After the 7 parameters are known, they are fixed in the simulation. The rotational temperature is then floated and the best-fit values are calculated from the N2 pure-rotational spectra, as shown in Supporting Information Figure S4. After the rotational temperature is known, we fix the rotational temperature and calculate the vibrational temperature from the Q-branch N2 vibrational spectra.

Figure 7c shows the experimental setup of the 3-beam fs/ps coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) system for detecting N2(ν). The Ti:Sapphire amplifier (Astrella, Coherent Inc.) outputs 100 fs pulses centered near 800 nm at 1 kHz. The output pulse energy is ≈ 7 mJ and is divided into three legs. One leg ( ≈ 4 mJ) is used to pump the optical parametric amplifier (TOPAS NIRUVIS, Light Conversion), which is centered at 675 nm to target the Q-branch N2 Raman transitions43. Another 1 mJ is served as the Stokes beam, and the rest of the 2 mJ is used to generate the 400 nm narrowband probe pulse. A second harmonic bandwidth compressor (SHBC) is used to convert the 100 fs beam into a ps-duration probe beam. Two delay lines with linear translational stages are used to achieve optimal timing between the pump, Stokes and probe pulses. Following the planar BOXCARS phase matching scheme43, a 250 mm lens is used to focus the three input beams. In this phase matching scheme, the vibrational CARS signal partially overlaps with the pure-rotational CARS signal, which is generated at the same location as the probe pulse on the collimating lens. The vibrational CARS signal is generated by the pump and Stokes pair, while the pure-rotational signal is generated by the Stokes beam. A 2.5 ps probe time delay is used for the vibrational CARS spectra, while an 8.5 ps probe delay is applied to suppress the non-resonant background of the pure-rotational spectra. Short-pass filters (Semrock) are used to separate the CARS signals from the probe pulse. The CARS signal is focused with a 75 mm lens into a spectrometer (2400 l/mm grating) and sampled by an intensified CCD (ICCD) camera. The spectrometer is centered at 367.50 nm and 393.47 nm for vibrational and pure-rotational CARS, respectively. The vibrational CARS signal can be easily separated from the pure-rotational CARS signal by tuning the spectrometer grating. The camera is synchronized with the fs laser and AC power supply with a delay generator (SRS DG645). For each condition, 50 frames are saved on average, with 20 exposures of 350 ns per frame.

NH3 measurements

Figure 7 (b) shows the experimental setup of laser absorption for time-dependent ammonia measurements. The Ti:Sapphire amplifier (Astrella, Coherent Inc.) outputs 100 fs pulses centered near 800 nm at 1 kHz. The optical parametric amplifier (TOPAS NIRUVIS, Light Conversion) is centered at 201 nm, via a series of nonlinear optical processes including second-harmonic generation and sum-frequency generation, with a pulse energy of ~6 µJ to target the \({\widetilde{{{\rm{A}}}}}^{1}{{{\rm{A}}}}_{2}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\leftarrow {\widetilde{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{1}{{{\rm{A}}}}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) transition of the ammonia ν2 bending mode54. Two mirrors are used to perform 5-pass absorption measurements through the plasma cell with an optical length of 22.5 * 5 = 112.5 cm. The signal is focused with a 125 mm lens into a spectrometer and sampled by an intensified CCD (ICCD) camera. The camera is synchronized with the fs laser and AC power supply with a delay generator (SRS DG645). A gate width of 130 ns is used for the camera. The baseline of the no-plasma condition is used to calculate ammonia concentration based on the Beer-Lambert law: \(-{\mathrm{ln}}\left(\frac{{I}_{t}}{{I}_{0}}\right)=\sigma {Ln}\), where \({I}_{t}\) and \({I}_{0}\) are light intensities after the passage of the cell with and without plasma, \(\sigma\) is the ammonia absorption cross-section, \(L\) is the optical length, and \(n\) is the ammonia number density55.

Optical emission spectroscopy (OES)

The emission spectra from the plasma discharge are acquired by using a miniature spectrometer (Ocean Optics, USB2000 + ) via an optical fiber placed right at the side of the quartz cell wall, with an acquisition time of 1 s. The spectra are background-subtracted.

Plasma kinetic modeling

The path flux analysis in this study is conducted using a hybrid ZDPlasKin-CHEMKIN model developed at Princeton University56,57,58. This model couples the plasma kinetics solver ZDPlasKin59 with the combustion kinetics solver CHEMKIN60 through a time-splitting scheme. Electron impact reaction rate constants and transport parameters are computed using the Boltzmann equation solver BOLSIG + 61, which is integrated into ZDPlasKin. This in-house model has been extensively validated against experimental data in previous studies39,56,62,63, with the governing equations detailed in ref. 56.

The recently developed N2/H2 plasma chemistry for NH3 synthesis57,63,64 is used in this work. This kinetic model has been rigorously validated against experimental measurements of temperature and the number densities of radicals and excited species. It comprises two components: a plasma kinetic sub-mechanism, which includes electrons, ions, and electronically/vibrationally excited species; and a gas-phase sub-mechanism, which accounts for ground-state species. The model includes 50 species, 494 reactions in the plasma kinetic mechanism, and 51 reactions in the gas-phase mechanism. The plasma kinetic sub-mechanism captures key processes such as electron impact vibrational and electronic excitation, dissociation, ionization, attachment, quenching, energy transfer, charge exchange, and both ion-ion and electron-ion recombination. All reactions related to the path flux analysis of N, H, and NH species are listed in the Supporting Information Tables S2–S4.

To simulate the AC dielectric barrier discharge plasma, the methodology developed by van’t Veer et al37. is implemented within the hybrid ZDPlasKin-CHEMKIN framework. Given the filamentary nature of AC plasmas, the model represents micro-discharges by applying periodic triangular pulses of power density. The experimentally measured plasma power is distributed across these pulses, with the peak power, pulse duration, and frequency fitted to experimental data. In this study, 50 triangular pulses, each with a duration of 400 ns at a discharge frequency of 119 kHz, are applied over the full residence time.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the manuscript and the supplementary materials. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ju, Y. & Andrey, S. Plasma Assisted Combustion and Chemical Processing. (CRC Press, 2025).

Ostrikov, K., Cvelbar, U. & Murphy, A. B. Plasma nanoscience: setting directions, tackling grand challenges. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 44, 174001 (2011).

Burger, C. M., Zhang, A. J., Xu, Y., Hansen, N. & Ju, Y. Plasma-assisted chemical-looping combustion: Low-temperature methane and ethylene oxidation with nickel oxide. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 789–798 (2023).

Zhong, H. et al. Kinetic study of plasma-assisted n-dodecane/O₂/N₂ pyrolysis and oxidation in a nanosecond-pulsed discharge. Proc. Combust. Inst. 38, 6521–6531 (2021).

Lele, A. D., Xu, Y. & Ju, Y. Modelling the effect of surface charging on plasma synthesis of ammonia using DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp06050k (2024).

Shah, J. R., Gorky, F., Lucero, J., Carreon, M. A. & Carreon, M. L. Ammonia synthesis via atmospheric plasma catalysis: Zeolite 5A, a case of study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 59, 5167–5176 (2020).

Kim, H. H., Teramoto, Y., Ogata, A., Takagi, H. & Nanba, T. Plasma catalysis for environmental treatment and energy applications. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 36, 45–72 (2016).

Liu, T. W., Gorky, F., Carreon, M. L. & Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A. Energetics of reaction pathways enabled by N and H radicals during catalytic, plasma-assisted NH₃ synthesis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 2034–2051 (2022).

Mehta, P. et al. Overcoming ammonia synthesis scaling relations with plasma-enabled catalysis. Nat. Catal. 1, 269–275 (2018).

Berry, M., Yang, X. & Adamovich, I. V. Ammonia generation in a “hybrid high repetition rate ns pulse/RF discharge sustained over a catalytic surface. in AIAA SciTech Forum and Exposition,https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2024-1826. (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc, AIAA, 2024).

Chen, Z., Koel, B. E. & Sundaresan, S. Plasma-assisted catalysis for ammonia synthesis in a dielectric barrier discharge reactor: key surface reaction steps and potential causes of low energy yield. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 55, 17 (2022).

Bayer, B. N., Bruggeman, P. J. & Bhan, A. Species, pathways, and timescales for NH₃ formation by low-temperature atmospheric pressure plasma catalysis. ACS Catal. 13, 2619–2630 (2023).

Carrasco, E., Jiménez-Redondo, M., Tanarro, I. & Herrero, V. J. Neutral and ion chemistry in low pressure DC plasmas of H₂/N₂ mixtures: routes for the efficient production of NH₃ and NH₄+. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19561–19572 (2011).

Ma, Y., Wang, Y., Harding, J. & Tu, X. Plasma-enhanced N₂ fixation in a dielectric barrier discharge reactor: Effect of packing materials. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 30, 105002 (2021).

Navascués, P., Garrido-García, J., Cotrino, J., González-Elipe, A. R. & Gómez-Ramírez, A. Incorporation of a metal catalyst for the ammonia synthesis in a ferroelectric packed-bed plasma reactor: Does it really matter?. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 11, 3621–3632 (2023).

Patil, B. S. et al. Deciphering the synergy between plasma and catalyst support for ammonia synthesis in a packed dielectric barrier discharge reactor. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 53, 144003 (2020).

Johnson, M. J. & Go, D. B. Ferroelectric crystals for the low-voltage operation of surface dielectric barrier discharges. Appl Phys. Lett. 105, 264102 (2014).

Dunaevsky, A. & Fisch, N. J. Operation of ferroelectric plasma sources in a gas discharge mode. Phys. Plasmas 11, 2957–2963 (2004).

Gómez-Ramírez, A., Cotrino, J., Lambert, R. M. & González-Elipe, A. R. Efficient synthesis of ammonia from N₂ and H₂ alone in a ferroelectric packed-bed DBD reactor. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 24, 065011 (2015).

Xu, Y. et al. Enhancements of electric field and afterglow of non-equilibrium plasma by Pb(ZrₓTi₁₋ₓ)O₃ ferroelectric electrode. Nat. Commun. 15, 3092 (2024).

Spaldin, N. A. A beginners guide to the modern theory of polarization. J. Solid State Chem. 195, 2–10 (2012).

Martínez, H. & Yousif, F. B. Electrical and optical characterization of pulsed plasma of N₂-H₂. Eur. Phys. J. D. 46, 493–498 (2008).

Wang, C. et al. Photocathodic behavior of ferroelectric Pb(Zr, Ti)O₃ films decorated with silver nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 49, 3769–3771 (2013).

Zahid, M. A. et al. Influence of Al₂O₃/IZO double-layer antireflective coating on the front side of rear emitter silicon heterojunction solar cell. Vacuum 200, 110967 (2022).

Horváth, B., Daksha, M., Korolov, I., Derzsi, A. & Schulze, J. The role of electron induced secondary electron emission from SiO₂ surfaces in capacitively coupled radio frequency plasmas operated at low pressures. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol 26, 124001 (2017).

Ivković, S. S., Obradović, B. M. & Kuraica, M. M. Electric field measurement in a DBD in helium and helium–hydrogen mixture. J. Phys. D. Appl Phys. 45, 275204 (2012).

Radmilović-Radjenović, M., Radjenović, B., Klas, M. & Matejčik, Š Breakdown voltage curves in direct current discharges in molecular gases at microgaps. Micro Nano Lett. 7, 232–234 (2012).

Albritton, D. L., Miller, T. M., Martin, D. W. & McDaniel, E. W. Mobilities of mass-identified H₃+ and H+ ions in hydrogen. Phys. Rev. 171, 94–102 (1968).

Babich, L. & Loiko, T. V. Generalized Paschen’s law for overvoltage conditions. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 44, 3243–3248 (2016).

Goldberg, B. M., Shkurenkov, I., Adamovich, I. V. & Lempert, W. R. Electric field in an AC dielectric barrier discharge overlapped with a nanosecond pulse discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol 25, 045008 (2016).

Zhu, X. M. & Pu, Y. K. Optical emission spectroscopy in low-temperature plasmas containing argon and nitrogen: Determination of the electron temperature and density by the line-ratio method. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 43, 403001 (2010).

Cicala, G., De Tommaso, E., Rainò, A. C., Lebedev, Y. A. & Shakhatov, V. A. Study of positive column of glow discharge in nitrogen by optical emission spectroscopy and numerical simulation. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 18, 025032 (2009).

Nunomura, S. & Ezumi, N. Electron temperature characterization of H₂ processing plasma by optical emission spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Express 17, 116001 (2024).

Wróbel, A. M. et al. Remote hydrogen-nitrogen plasma chemical vapor deposition from a tetramethyldisilazane source. Part 1. Mechanism of the process, structure and surface morphology of deposited amorphous hydrogenated silicon carbonitride films. J. Mater. Chem. 13, 731–737 (2003).

El-Brulsy, R. A., Abd Al-Halim, M. A., Abu-Hashem, A., Rashed, U. M. & Hassouba, M. A. Effect of hydrogen ratio on plasma parameters of N₂-H₂ gas mixture glow discharge. Plasma Phys. Rep. 38, 432–438 (2012).

Hong, J. et al. Kinetic modelling of NH₃ production in N₂-H₂ non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasma catalysis. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 154005 (2017).

Van’t Veer, K., Engelmann, Y., Reniers, F. & Bogaerts, A. Plasma-catalytic ammonia synthesis in a DBD plasma: Role of microdischarges and their afterglows. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 22871–22883 (2020).

Liu, N. et al. Quantitative femtosecond two-photon absorption laser induced fluorescence measurements of hydrogen and nitrogen atoms in an AC dielectric barrier discharge. in AIAA SciTech Forum and Exposition, 2023 https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2023-0351 (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc, AIAA, 2023).

Liu, N. et al. Unraveling nonequilibrium generation of atomic nitrogen and hydrogen in plasma-aided ammonia synthesis. ACS Energy Lett 2031–2036 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.4c00729 (2024).

Lo, A., Cléon, G., Vervisch, P. & Cessou, A. Spontaneous Raman scattering: a useful tool for investigating the afterglow of nanosecond scale discharges in air. Appl. Phys. B 107, 229–242 (2012).

Jelloian, C. C., Bendana, F. A., Wei, C., Spearrin, R. M. & MacDonald, M. E. Nonequilibrium vibrational, rotational, and translational thermometry via megahertz laser absorption of CO. J. Thermophys. Heat. Trans. 36, 266–275 (2021).

Lempert, W. R. & Adamovich, I. V. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering and spontaneous Raman scattering diagnostics of nonequilibrium plasmas and flows. J. Phys. D. Appl Phys. 47, 433001 (2014).

Chang, Z. et al. Hybrid fs/ps CARS for non-equilibrium temperature measurements in N₂/H₂ DC glow discharges. in AIAA SCITECH 2025 Forum https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2025-0795 (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Plasma-enhanced catalytic synthesis of ammonia over a Ni/Al₂O₃ catalyst at near-room temperature: Insights into the importance of the catalyst surface on the Reaction Mechanism. ACS Catal 10780–10793 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.9b02538 (2019).

Qu, Z. et al. Plasma-assisted sustainable nitrogen-to-ammonia fixation: mixed-phase, synergistic processes and mechanisms. ChemSusChem 17, e202300783 (2024).

Simon, J. & Winter, L. R. Plasma-activated co-conversion of N₂ and C₁ gases towards value-added products. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain Chem. 51, 100985 (2025).

Zhao, H. et al. In situ identification of NNH and N₂H₂ by using molecular-beam mass spectrometry in plasma-assisted catalysis for NH₃ synthesis. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 53–58 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Plasma-assisted surface nitridation of proton intercalatable WO₃ for efficient electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis. ACS Energy Lett 3349–3358 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.5c01034 (2025).

Liu, N. et al. Femtosecond two-photon laser induced fluorescence measurements of H and N in plasma assisted NH₃ synthesis. in Optica Sensing Congress (2024).

Gazeli, K. et al. Progresses on the use of two-photon absorption laser induced fluorescence (TALIF) diagnostics for measuring absolute atomic densities in plasmas and flames. Plasma 4, 145–171 (2021).

Stauffer, H. U. et al. Time- and frequency-dependent model of time-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) with a picosecond-duration probe pulse. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 024316 (2014).

Torge Mecker, N. et al. Optimizing hybrid rotational femtosecond/picosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy in nitrogen at high pressures and temperatures. J. Optical Soc. Am. B 37, 1035–1046 (2020).

Chang, Z., Gejji, R. M., Gu, M. & Lucht, R. P. H₂ chirped-probe-pulse femtosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering thermometry at high temperature and pressure. Opt. Express 32, 13701–13719 (2024).

Vaida, V. et al. The ultraviolet absorption spectrum of the Ã1A″₂←X̃1A′₁ transition of jet-cooled ammonia. J. Chem. Phys. 86, 6669–6676 (1986).

Weng, W., Li, S., Aldén, M. & Li, Z. Ultraviolet absorption cross-sections of ammonia at elevated temperatures for nonintrusive quantitative detection in combustion environments. Appl Spectrosc. 75, 1168–1177 (2021).

Mao, X., Chen, Q., Rousso, A. C., Chen, T. Y. & Ju, Y. Effects of controlled non-equilibrium excitation on H₂/O₂/He ignition using a hybrid repetitive nanosecond and DC discharge. Combust Flame 522–535 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2019.05.027 (2019).

Mao, X., Zhong, H., Liu, N., Wang, Z. & Ju, Y. Ignition enhancement and NOₓ formation of NH₃/air mixtures by non-equilibrium plasma discharge. Combust Flame 259, 113140 (2024).

Mao, X., Rousso, A., Chen, Q. & Ju, Y. Numerical modeling of ignition enhancement of CH₄/O₂/He mixtures using a hybrid repetitive nanosecond and DC discharge. Proc. Combust. Inst. 37, 5545–5552 (2019).

Paneheshnyi, S., Eismann, B., Hagelaar, G. J. M. & Pitchford, L. C. Computer code ZDPlasKin. http://www.zdplaskin.laplace.univ-tlse.fr (University of Toulouse, LAPLACE, CNRS-UPS-INP, Toulouse, France, 2008).

Kee, R. J., Rupley, F. M. & Miller, J. A. Chemkin-II: a fortran chemical kinetics package for the analysis of gas-phase chemical kinetics. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/5681118 (1989).

Hagelaar, G. J. M. & Pitchford, L. C. Solving the Boltzmann equation to obtain electron transport coefficients and rate coefficients for fluid models. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 14, 722–733 (2005).

Liu, N. et al. Kinetics of low temperature plasma assisted NH₃/H₂ oxidation in a nanosecond-pulsed discharge. 40, 105353 (2024).

Zhong, H. et al. Understanding non-equilibrium N₂O/NOₓ chemistry in plasma-assisted low-temperature NH₃ oxidation. Combust Flame 256, 112948 (2023).

Mao, X., Zhong, H., Zhang, T., Starikovskiy, A. & Ju, Y. Modeling of the effects of non-equilibrium excitation and electrode geometry on H₂/air ignition in a nanosecond plasma discharge. Combust Flame 240, 112046 (2022).

Erfani, N., Baharudin, L. & Watson, M. Recent advances and intensifications in Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis process. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 204, 109962 (2024).

Shah, J., Wang, W., Bogaerts, A. & Carreon, M. L. Ammonia synthesis by radio frequency plasma catalysis: Revealing the underlying mechanisms. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 1, 4824–4839 (2018).

Gómez-Ramírez, A., Montoro-Damas, A. M., Cotrino, J., Lambert, R. M. & González-Elipe, A. R. About the enhancement of chemical yield during the atmospheric plasma synthesis of ammonia in a ferroelectric packed bed reactor. Plasma Process. Polym. 14, 1600081 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the DOE Plasma Fusion Office grant DE-SC0025371 for ferroelectric plasma discharge, DOE BES grant DE-SC0021135 for laser diagnostics, and NSF grant OIA-2428523 for ammonia synthesis. YJ gratefully acknowledges the support from Tohoku University as a Distinguished Professor (Visiting) and the valuable research discussions with Prof. Kaoru Maruta at Tohoku University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., Z.C., H.B, Z. Sun and W.W. designed and performed the experiments. Y.X. and Z.C. analyzed the experimental data. Z. Shi performed simulation calculations. N.L. provided theoretical input on data interpretation. Y.X. prepared the paper draft. Y.J. supervised the research. All authors discussed the results and the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Paula Navascués, Zefeng Ren and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Chang, Z., Shi, Z. et al. Enhanced production of active species and NH3 using non-equilibrium ferroelectric barrier discharge. Nat Commun 16, 11309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66403-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66403-6