Abstract

One-step removal of multiple impurities implemented by adsorptive separation is an efficient and simple process to afford high purity products, but is hindered by the lack of advanced porous materials that could capture different types of molecules. Herein, a series of novel metal-organic frameworks ZU-921 to ZU-924 with cooperative binding environment of integrated aromaticity surface and fluorine/oxygen electronegative sites are designed, and ZU-921 is presented as the demonstration that solves the long-standing challenge in one-step propylene (C3H6) purification from the C3 quaternary mixture. The selective recognition ability towards alkyne, allene, alkane than alkene implemented by ZU-921 is attributed to the optimal interaction contribution from polarizability and dipole/quadruple moments that is realized by the fine-tuned density of parallelly-distributed electronegative sites via ligand engineering strategy. Ultra-high purity (99.99%) C3H6 could be directly obtained from the C3 quaternary mixture (C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 1 v/1 v/3 v/95 v) with the productivity of 17.27 L/kg derived from the 10-times scale-up column (1.0 cm × 50 cm) breakthrough experiment. This work not only presents a common strategy in advanced adsorbents design for multiple impurities capture but also provides an energy-efficient alternative for C3H6 purification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple impurity capture is the essential step in gas purification, determining the gas purity, and is closely associated with the energy cost of the process1,2,3,4,5. Polymer-grade (>99.5%) propylene (C3H6) is the critical bulk commodity, and its purification involves the removal of complex impurities with similar properties, like propyne (C3H4, ~1%), propadiene (C3H4 (PD), ~1%), and propane (C3H8, ~3%)6,7. Currently, the purification of alkene relies on the tandem separation process in industry, including catalytic hydrogenation (noble-metal catalyst at high temperature and pressure) and cryogenic distillation (over 100 trays at 243 K and 0.3 MPa). The energy-intensive nature of the above separation process has spurred research into the development of nonthermal-driven separation technology8,9.

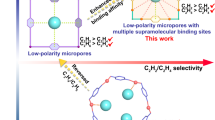

Adsorptive separation is recognized as a potentially energy-saving alternative to solve challenging separations, and considerable achievements have been gained along with the continuous development of advanced porous materials10,11, like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)12,13,14,15,16,17, covalent-organic frameworks (COFs)18,19, etc.20,21,22,23. Benefiting from their demonstrated fine-tuning ability of pore size and pore chemistry, tailor-made porous materials towards C3H6 purification have been developed, such as binary mixtures of C3H4/C3H624,25, and C3H6/C3H826,27,28, ternary mixtures of C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H629,30. In detail, the designed porous materials, decorating the pore surface with polar groups, like anions31, open metal sites32, are able to preferentially adsorb the molecules with higher dipole/quadrupole moments, and remove trace alkyne from C3H6 mixtures, as well as the selective capture of C3H6 from C3H8. Constructing an alkane trap to introduce high-density weak interaction sites can enhance the binding affinity with C3H8, and realize the selective capture of C3H8 from C3H6 mixtures33,34, but fail to simultaneously capture the C3H4, C3H4(PD) with lower polarizability. Controlling pore size to create molecular sieves that could exclude molecules of large size, achieving the separation of C3H4 and C3H6 from C3H4/C3H6 and C3H6/C3H8 mixtures, respectively35,36,37,38. However, despite the above progress, one-step C3H6 purification from quaternary C3 mixtures containing C3H4, C3H4(PD), and C3H8 via a single physisorbent still remains a grand challenge39.

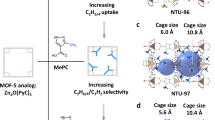

To realize one-step C3H6 purification, the adsorbents are expected to show higher binding affinity towards all C3 alkyne, allene, and alkane than alkene. However, as revealed by the physiochemical properties of the four gases, they have very similar properties, especially for C3H6 and C3H8. The polarizability, dipole/quadrupole moments, and molecular size of C3H6 all lie between C3H4/C3H4 (PD) and C3H8. Meanwhile, C3H8 shows the highest polarizability but the lowest dipole/quadrupole moments, while the condition is reversed for C3H4 and C3H4(PD). The fact indicates that the different binding sites or environments and their fine-tuning are required to realize the preferential accommodation of C3H4, C3H4(PD), and C3H8 than that of C3H6 in the confined channel, posing a daunting challenge to the design of porous materials (Fig. 1a and Fig. S1). In detail, to fulfill the target of simultaneous capture of C3H4, C3H4 (PD), and C3H8, the design of porous materials needs to overcome two great challenges. (1) Creating a molecular trap that shows preferential adsorption towards C3H8 than C3H6, the small polarizability difference between C3H8 and C3H6 makes it challenging (polarizability: C3H8 62.9–63.7 × 10−25 cm3 vs C3H6 62.6 × 10−25 cm3)33,34,40, the C3H8/C3H6 selectivity of most reported C3H8-selective materials is around 1.541,42. (2) Creating the cooperative binding environment that recognizes molecules via both polarizability and dipole/quadrupole moments43,44. Different affinity sequences of the four C3 gases could be realized via fine-tuning the interaction contribution from the different kinds of binding sites32 (Fig. 1b, c). Through the exploitation of more H interaction sites of C3H8 than C3H6 and higher electropositivity H atoms of C3H4, C3H4(PD) than C3H6, porous materials with an optimal cooperative binding environment rationally show the weakest C3H6 affinity. Following this idea, the fluorine/oxygen polar binding sites are integrated into the aromatic-based alkane trap that is mainly dominated by the dispersion/induction interactions based on polarizability.

a The properties difference of C3H4, C3H4 (PD), C3H6, and C3H8, b the illustration of the strategy of adsorbents design. Introducing O/F electronegative sites into the aromatic-based propane trap to form a cooperative binding environment, and controlling the density of introduced electronegative sites to fine-tune the binding affinity sequence of the four C3 gases, c the adsorption behavior of C3H4, C3H4 (PD), C3H6, and C3H8 under the optimal cooperative interaction environments. C3H4 and C3H4 (PD) exhibit higher affinity with O/F than C3H6 due to their higher polarity, while C3H8 could form more dense interactions with the aromatic-based sites and O/F sites than C3H6.

Through controlling the density of parallelly distributed fluorine via a ligand engineering strategy, the contribution of interactions from the dipole/quadrupole moments and polarizability could be fine-tuned. Herein, we solved the challenge of one-step C3H6 purification from the quaternary mixtures using tailor-made ZU-921 (ZU-represents Zhejiang University) featuring orderly lined aromatic surfaces and optimal density of electronegative sites. The selectively adsorbed alkyne, allene, and alkane over alkene molecules are bonded simultaneously via hydrogen-bonding interactions and multiple van der Waals interactions with high selectivity of alkane/alkene (2.03), alkyne/alkene (2.17), and allene/alkene (2.03). High-purity (99.99%) C3H6 could be directly obtained from C3 quaternary mixtures (C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 1 v/1 v/3 v/95) with the productivity of around 17.27 L/kg using ZU-921 as demonstrated by the 10-times scale-up column breakthrough experiments. The molecular-level understanding of the adsorption behavior for C3 gases within the well-defined pore space highlighted the importance of the rational integration of synergistic binding sites to enhance the recognition ability of multiple gases with different properties.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

A series of isostructural ultramicroporous materials, ZU-921 ([Co(IPA-F)(DPG)]n, DPG = meso-α, β-di(4-pyridyl) glycol, IPA-F = 5-fluoroisophthalic acid), ZU-922 ([Co(IPA-CH3)(DPG)]n, IPA-CH3 = 5-methylisophthalic acid), ZU-923 ([Co(BDC-2F)(DPG)]n, BDC-2F = 2,5-difluoroterephthalic acid) and ZU-924 ([Co(BDC-4F)(DPG)]n, BDC-4F = tetrafluoroterephthalic acid) were successfully synthesized through solvothermal reactions of Co(NO3)2·6H2O, meso-α, β-di(4-pyridyl) glycol and their corresponding dicarboxylate acid. The structures of ZU-921 to ZU-924 are isostructural except for the functional groups, as revealed by their similar powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (Fig. S2). The method of Rietveld refinement was adopted to obtain the refinement structures of ZU-921 and ZU-922 based on the parent structure of [Co(IPA)(DPG)]n (IPA = isophthalic acid)45, and the low Rp (0.0143, 0.0142) and Rwp (0.0298, 0.0270) values indicate the high quality of the analyzed structures (Fig. S3, Table S2 and “Structure simulation” section). The PXRD patterns of the synthesized power of ZU-921 and ZU-922 are well matched with the simulated one of the refined structures (Fig. S4). Individually, each Co(II) atom was connected by two pyridine groups and two hydroxyl groups from independent meso-α, β-di(4-pyridyl) glycol ligands to form a 2D layer network, and the 2D layer network was further pillared by the dicarboxylate acid (IPA-F and IPA-CH3, BDC, BDC-2F and BDC-4F) to afford a 3D framework with one-dimensional straight channel (Fig. 2a, b). The pore windows of ZU-921 to ZU-924 are estimated to be 5.6 × 4.4 Å2, 5.6 × 3.8 Å2, 6.1 × 4.0 Å2, and 6.1 × 3.7 Å2 by the model of Connolly surface with probe of diameter 1.0 Å (Fig. 2b)46. The channels of these isostructural materials are featured with the parallel-aligned linearly extending isophthalic acid units, which can provide a big π system and multiple hydrogen bond acceptors for the accommodation of alkane. Through ligand engineering strategy, the surface electrostatic potential of the pore environment could be well fine-tuned via controlling the types and density of functional groups. We could observe that the pore channel shows more negative electrostatic potential with the increased density of polar fluorine functional sites, which would enhance the binding affinity with polar molecules (Fig. 2c). The permanent porosity of the synthesized porous materials was investigated by 77 K N2 and 195 K CO2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (Figs. S5 and S6). The corresponding surface area and pore volume were calculated and summarized in Table S3. The Langmuir surface area and pore volume were determined as 356.6 m2 g−1 and 0.145 cm3 g−1 for ZU-921, and 369.5 m2 g−1 and 0.150 cm3 g−1 for ZU-922, respectively. The pore size distribution (PSD) of ZU-921 and ZU-922 is centered at 4.9 Å and 4.5 Å, respectively, which agrees well with the theoretical pore size from crystal simulation (Figs. 1b and S6). Moreover, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves demonstrated the good thermal stability of ZU-921 and ZU-922, and their decomposition temperatures are up to 280 °C and 300 °C, respectively (Fig. S7). The morphology was investigated using a NOVA 200 Nanolab scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Fig. S8). Additionally, the invariable PXRD patterns and BET results indicate that ZU-921 is stable in different solvents (MeOH, EtOH, MeCN, Acetone, and DMF) and solutions with different pH (pH = 5, pH = 9, pH = 11) (Figs. S9–S11).

Adsorption and separation performances

The single-component adsorption isotherms of C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H6, and C3H8 were measured to explore the adsorption performance of ZU-921 to ZU-924 and PCP-BDC (Figs. 3a, b and S12–S17). As depicted in Fig. 3a, b, all the C3H8, C3H4 (PD), and C3H4 adsorption capacities of F-functional ZU-921 are higher than that of C3H6 during the whole pressure range (0–1.0 bar), suggesting its preferential adsorption behavior towards C3H4, C3H4(PD), and C3H8 over C3H6. To our knowledge, this adsorption behavior has not been observed in the reported literature. The ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) method is applied to further evaluate the separation potentials of porous materials6. Considering the impurity content of C3H4, C3H4 (PD), and C3H8 in cracking gas typically account for 0.5–1%, 0.5–1% and 2–3%29,34,47, respectively, the selectivity of C3H8/C3H6 (3 v/97 v), C3H4/C3H6 (1 v/99 v) and C3H4(PD)/C3H6 (1 v/99 v) binary mixtures on ZU-921 to ZU-924 and PCP-BDC were calculated (Fig. S18). As shown in Fig. 3c, ZU-921 exhibited high IAST selectivity for all of C3H8/C3H6 (3 v/97 v), C3H4/C3H6 (1 v/99 v), and C3H4(PD)/C3H6 (1 v/99 v) binary mixture at 298 K and 1.0 bar, which is up to 2.03, 2.17, and 2.03, respectively. Relatively, ZU-922 and PCP-BDC with aromatic-based pore environment exhibited moderate C3H8/C3H6 selectivity (1.49 and 1.75) but failed to selectively capture polar C3H4 and C3H4 (PD). ZU-924 with a high density of polar F-functional sites shows the priority adsorption sequence of C3H4 > C3H4 (PD) > C3H6 > C3H8 (Figs. 3d and S18). The experimental results demonstrate that the introduced density of the polar F-functional group is critical to afford the ideal materials for one-step C3H6 purification. The time-dependent adsorption curves demonstrate that the adsorption rates of all four C3 gases in ZU-921 are close with no obvious kinetic effect, indicating that the good C3H6 purification performance of ZU-921 is governed by the thermodynamic equilibrium mechanism (Figs. S20–S22).

The C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H8, and C3H6 adsorption isotherms of ZU-921 at 298 K with (a) a logarithm scale under the pressure range of 0–1.0 bar, (b) a linear scale under the pressure range of 0–0.06 bar, c the IAST selectivity of C3 binary mixtures on ZU-921, d comparison of the IAST selectivity of C3 binary mixtures for the series of ZU-921 to ZU-924 and PCP-BDC at 298 K, and e comparison of the IAST selectivity of different C3 binary mixtures on ZU-921 with reported benchmark materials for C3 separation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we conducted a detailed comparison study about the adsorption separation performance for four C3 gases of the literature-reported benchmark materials, for example, the C3H4 and C3H4(PD)-selective materials (NKMOF-1-Ni30, NbOFFIVE-2-Cu-i29, SIFSIX-3-Ni24, and ZU-33 (GeFSIX-14-Cu-i)47) and C3H8-selective materials (Ni(ADC)(TED)0.548 and FDMOF-234). The C3H4, C3H4 (PD), C3H6, and C3H8 adsorption isotherms of these materials and their corresponding IAST selectivity of binary mixtures were measured and calculated (Figs. S23–S29 and Tables S4 andS5). None of these materials are able to simultaneously capture C3H4, C3H4 (PD), and C3H8 from C3H6 mixtures (Fig. 3e). In detail, the C3H4 and C3H4(PD)-selective materials with polar sites exhibit outstanding selectivities of C3H4/C3H6 and C3H4(PD)/C3H6, but the C3H8/C3H6 selectivity is lower than 1.0, indicating that the polar sites used to capture polar alkyne and allene are not beneficial for the alkane-selective adsorption. Similarly, the C3H8-selective materials with high-density weak interaction sites fail to capture C3H4 and C3H4(PD), and the C3H8/C3H6 selectivity is always low (≤2.0), revealing that the inert pore environment designed for the C3H8-selective adsorption could not be adapted for the accommodation of polar alkyne and allene. These results indicated that it was of great challenge to construct advanced porous materials that could selectively adsorb polar alkyne and allene, and inert alkane over alkene.

Transient breakthrough experiments

Inspired by the unique adsorption behavior and high separation selectivity for C3 binary mixtures of ZU-921, the dynamic breakthrough experiments with mimicking C3 quaternary mixture proportions of cracking gas (C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 1 v/1 v/3 v/95 v) were conducted to evaluate its actual separation ability. The detailed experiment conditions and calculation methods of C3H6 productivity were described in the supporting information (Figs. S30–S31 and Table S13). As described in Fig. 4a, as the C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1 v/1 v/3 v/95 v) mixture flowed through the column packed with ZU-921 under different temperatures (273 K, 298 K and 313 K), the C3H6 always eluted first, and then C3H4, C3H4(PD) and C3H8 broke out simultaneously, indicating good one-pot C3H6 purification performances of ZU-921. Specifically, 15.21 L/kg (99.99%) of C3H6 could be produced directly at 298 K and 1.0 bar (Fig. S32). The simple C3H6 purification process provides a potential energy-saving route to replace the current complex cascade purification ways. In addition, the separation performance towards equimolar C3 quaternary mixture (C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 25/25/25/25 v/v/v/v) on ZU-921 was further explored, and the C3H6 still firstly eluted at the time of 26.5 min/g with the C3H6 (99.5%) productivity of 3.63 L/kg (Figs. 4b and S33 andS34). The roll-up phenomenon of C3H6 indicates that ZU-921 shows the weakest affinity towards C3H6, and all C3H4, C3H4(PD), and C3H8 were almost simultaneously eluted, demonstrating their close binding affinity within ZU-921 (Fig. 4b). We also explored the dynamic breakthrough performance of ZU-922 and FDMOF-2 under the same conditions. As shown in Figs. S35 and S36, C3H6, C3H4, and C3H4(PD) were simultaneously eluted, while C3H8, with the highest adsorption affinity, was well adsorbed. The results showed that ZU-922 and FDMOF-2 could only realize the selective C3H8 capture from C3H6, consistent with the adsorption isotherm results. Considering the complex competitive behavior in multi-component separations, the breakthrough experiments for binary mixtures of C3H8/C3H6 and C3H4/C3H6 were conducted (Figs. S37 andS38). As revealed by the breakthrough experiments of C3H8/C3H6 and C3H4/C3H6 binary mixtures, C3H6 is always first eluted, followed by C3H8 or C3H4, indicating that ZU-921 could selectively capture the C3H4 and C3H8 to produce C3H6 directly. The C3H6 productivity of ZU-921 is up to 10.08 L/kg for the C3H8/C3H6 (50/50) binary mixture (Figs. 4c and S40), lower than FDMOF-2 (21.0 L/kg)34, but exceeding most of the reported materials, BUT-10 (3.95 L/kg)43 and WOFOUR-1-Ni (3.50 L/kg)44 under the same conditions (Fig. S41). Moreover, the breakthrough experiments of C2H2/C2H4 (1/99) and C2H6/C2H4 (50/50) mixtures indicate that ZU-921 shows good C2H6-selective adsorptive performance, but poor C2H2/C2H4 separation performance (Fig. S43).

Dynamic breakthrough curves of ZU-921 for (a) C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v) mixture in Ct/C0 under 273, 298 K and 313 K and 1.0 bar; b C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (25/25/25/25 v/v/v/v) mixture in Ft/F0 under 298 K and 1.0 bar; c C3H8/C3H6 (50/50 v/v) mixture in Ft/F0 under 298 K and 1.0 bar; d Six recycling breakthrough tests for C3H8/C3H6 (50/50 v/v, red) and C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v, light blue) separation with ZU-921 under 298 K and 1.0 bar; e The PXRD patterns and C3H8 adsorption isotherms of ZU-921 after different treatments. (column: 0.46 cm × 15 cm, 1.33 g or 0.46 cm × 25 cm, 2.28 g, flow rate: 2.2 mL min−1). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Given the importance of the recyclability and stability of porous materials for practical applications, the water and thermal stability of ZU-921 were investigated. Even under high humid conditions up to RH = 75%, the breakthrough performance of ZU-921 was invariable (Fig. S39). Meanwhile, the separation performance of ZU-921 was well maintained during the six cycling tests for C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 and C3H8/C3H6 mixtures (Figs. 4d and S44–S46). No obvious structure degradation of ZU-921 was observed after it was exposed to different harsh conditions, such as humid air and high temperature (100 °C), as demonstrated by the invariant PXRD patterns and C3H8 adsorption isotherms (Fig. 4e). The impressive separation performance and the good stability of ZU-921 rendered it a promising adsorbent for one-step C3H6 purification from complex gas mixtures.

10-times scale-up breakthrough experiment

To further evaluate the application potential of ZU-921, we attempted the scale-up synthesis of ZU-921 and conducted the breakthrough experiments using the 10-times scale-up column (1.0 cm × 50 cm, 20.5 g) (Fig. S47). ZU-921 still exhibits impressive purification performance for different C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 mixtures (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v and 25/25/25/25 v/v/v/v) under different gas velocity (Figs. S48 andS49). The calculated C3H6 (99.99%) productivity is around 16.95 L/kg (5.0 mL/min) and 17.27 L/kg (10.0 mL/min) for the C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v) mixture (Figs. 5a, b and S50–S52). The column could be regenerated with nitrogen purge at 393 K for 800 min, and during the five consecutive cycling breakthrough experiments, the separation performance of ZU-921 remained invariable (Figs. 5c, S53–S56). We also evaluated the theoretical energy consumption for the C3H6 production, and the value of the adsorption process is lower than the cascade catalytic hydrogenation and distillation process used in industry (Tables S10–S12).

Dynamic breakthrough curves of ZU-921 for C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v) mixture in Ft/F0 at a 5.0 ml min−1, b 10.0 ml min−1, and c the recycling tests for C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 (1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v, red; 25/25/25/25 v/v/v/v, light blue) after the regeneration under 393 K with the N2 flow rate of 20.0 mL min−1. (column: 1.0 cm × 50 cm, 20.5 g). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Modeling simulation studies

To reveal the molecular-level adsorption behavior of C3 gases within the channel of ZU-921, we performed detailed modeling studies using the first-principles dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT-D) method45. As shown in Figs. 6 and S57, all the C3 gases prefer to adsorb along the extending direction of the channel to get enough interactions with the parallel-arranged 5-fluoroisophthalic acid. In detail, C3H4 and C3H4(PD) are adsorbed in almost the same location. Each C3H4 molecule could interact with two negative fluorine atoms and two uncoordinated oxygen atoms via multiple cooperative hydrogen bonds (two C–H•••O (2.46 Å and 2.83 Å), two C–H•••F (2.73 Å and 2.98 Å) and C ≡ C–H•••F (2.40 Å)) (Fig. 6a). The C3H4(PD) molecule is bounded by two C = C–H•••O (2.55 Å and 3.06 Å) and three C = C–H••• F (2.64 Å, 3.09 Å and 3.13 Å) (Fig. 6b). While the C3H8 is inclined to interact with the paralleled three 5-fluoroisophthalic acid units via multiple van der Waals forces (six C–H•••C 2.76–3.08 Å) and multiple H-bonding interactions (C–H•••O 2.74 and 3.18 Å, C–H•••F 2.80, 2.83 and 3.10 Å) (Fig. 6c). In contrast, the interactions between ZU-921 and C3H6 are only provided by one C–H•••O (2.73 Å) and two C–H•••F (2.55 Å and 2.70 Å) and three C–H•••C (2.74–2.95 Å) interactions (Fig. 6d). The binding energies of C3 gases on ZU-921 follow the sequence of C3H8 (−56.43 kJ/mol) > C3H4(PD) (−55.20 kJ/mol)≈C3H4 (−54.64 kJ/mol) > C3H6(−52.96 kJ/mol), which is consistent with the calculated Qst values of C3 gases based on their adsorption isotherms (Fig. S19). The results confirmed that ZU-921 could form a higher affinity with C3H8, C3H4, and C3H4 (PD) than C3H6. Simulation studies reveal that the polar fluorine, aromaticity sites, and uncoordinated oxygen are the keys to forming a synergistic binding environment for the simultaneous recognition of C3H4, C3H4 (PD), and C3H8 gases with different properties (Fig. S58).

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate the selective capture ability of ultramicroporous adsorbent ZU-921 for alkane, allene, and alkyne, achieving one-step C3H6 purification from C3 quaternary mixtures. The above remarkable progress in multiple impurities capture is attributed to the well-defined pore chemistry via ligand engineering strategy, the integrated binding sites of orderly lined aromatic units, as well as the quantified density of polar fluorine functional sites, enabling the exquisite control of priority affinity sequence of different molecules. Benefiting from the rational binding sequence, high-purity C3H6 (99.9% or 99.99%) could be easily obtained via a simple adsorption-desorption process from complex C3 mixtures. Our work not only presents an effective method to design advanced adsorbents for the simultaneous removal of multiple impurities but also demonstrates the great potential of adsorptive separation with tailor-made porous materials to simplify the complex separation process.

Methods

Chemicals

All reagents were analytical grade and used as received without further purification. Co(NO3)2·6H2O, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, isophthalic acid (IPA), 5-fluoroisophthalic acid (IPA-F), 5-methylisophthalic acid (IPA-CH3), terephthalic acid (BDC), 2,5-difluoroterephthalic acid (BDC-2F) and tetrafluoroterephthalic acid (BDC-4F) methanol (MeOH), and dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co. Ltd., Meso-α,β-Di(4-pyridyl) Glycol (DPG) was purchased from TCI Co. Ltd. 2,5-bis(trifluoromethyl) terephthalic acid (BDC-(CF3)2) and 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane (DABCO) were purchased from Aladdin. Ultrahigh purity grade He (99.999%), N2 (99.999%), C3H4 (99.9%), C3H4 (PD, 99.9%), C3H6 (99.99%), C3H8 (99.99%), and mixed gas (C3H4/C3H6 = 1/99, v/v, C3H6/C3H8 = 50/50, v/v, C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 = 1/1/3/95, v/v/v/v, C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 = 25/25/25/25, v/v/v/v) were purchased from Shanghai Wetry Standard gas Co., Ltd. (China) and used for all measurements.

Material synthesis

PCP-IPA-X33,49 and the comparison materials of FDMOF-234, Ni(ADC)(TED)0.548, NKMOF-1-Ni30, NbOFFIVE-2-Cu-i29, SIFSIX-3-Ni24, and ZU-3347 were synthesized according to the previously reported procedure.

ZU-921 (PCP-IPA-F)

81 mg DPG was dissolved in DMF/MeOH (1:1, 30 mL) at 60 °C, and 75 mg IPA-F and 109 mg Co(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 5 mL MeOH. Then, the two solutions were mixed and heated at 80 °C for 24 h to yield as-synthesized ZU-921, with the yield reaching up to 82% (based on DPG ligand).

Scale-up preparation of ZU-921

5.0 g DPG was dissolved in DMF/MeOH (1:1, 1.5 L) at 60 °C, and 4.63 g IPA-F and 6.7 g Co(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 50 mL MeOH. Then, the two solutions were mixed and heated at 80 °C for 24 h to yield as-synthesized ZU-921, with the yield reaching up to 80% (based on DPG ligand).

ZU-922 (PCP-IPA-CH3)

81 mg DPG was dissolved in DMF/MeOH (1:1, 30 mL) at 60 °C, and 75 mg IPA-CH3 and 109 mg Co(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 5 mL MeOH. Then, the two solutions were mixed and heated at 80 °C for 24 h to yield as-synthesized ZU-922, with the yield reaching up to 80% (based on DPG ligand).

ZU-923 (PCP-BDC-2F)

81 mg DPG was dissolved in DMF/MeOH (1:1, 30 mL) at 60 °C, and 80 mg BDC-2F and 109 mg Co(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 5 mL MeOH. Then, the two solutions were mixed and heated at 80 °C for 24 h to yield as-synthesized ZU-923, with the yield reaching up to 77% (based on DPG ligand).

ZU-924 (PCP-BDC-4F)

81 mg DPG was dissolved in DMF/MeOH (1:1, 30 mL) at 60 °C, and 95 mg BDC-4F and 109 mg Co(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 5 mL MeOH. Then, the two solutions were mixed and heated at 80 °C for 24 h to yield as-synthesized ZU-924, with the yield reaching up to 75% (based on DPG ligand).

FDMOF-2

A mixture of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.4 mmol), the BDC-(CF3)2 (0.4 mmol) and DABCO (0.2 mmol), DMF (15 mL), and two drops of HNO3 were added into a 25 mL glass vial. After the mixture was stirred for 30 min, the vial was sealed and heated at 120 °C for 48 h to yield as-synthesized FDMOF-2 with the yield reaching up to 65% (based on BDC-(CF3)2 ligand).

Sample characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were collected using a PANalytical Empyrean series 2 diffractometer with Cu-Ka radiation, at room temperature, with a step size of 0.0167°, a scan time of 15 s per step, and 2θ ranging from 5 to 50°. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) data were collected in a NETZSCH Thermogravimetric Analyzer (STA2500) from 50 to 700 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The morphology was investigated using a NOVA 200 Nanolab scanning electron microscope (SEM). The 195 K CO2 and 77 K N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were obtained on a Micromeritics 3Flex and BSD-660 volumetric adsorption apparatus. The apparent Langmuir surface area was calculated using the adsorption branch with the relative pressure P/P0 in the range of 0.005–0.1. The total pore volume (Vtot) was calculated based on the adsorbed amount of CO2 or N2 at the P/P0 of 0.99. The pore size distribution (PSD) was calculated using the H-K methodology with CO2 adsorption isotherm data and assuming a slit pore model.

Gas adsorption measurements

The C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H6, and C3H8 adsorption-desorption isotherms at different temperatures were measured volumetrically by Micromeritics 3Flex and BSD-660 adsorption apparatus for pressures up to 1.0 bar. Prior to the adsorption measurements, the samples were degassed using a high vacuum pump (<5 μm Hg) at 373 K for over 12 h.

Kinetic adsorption measurement

The time-dependent adsorption profiles of C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H8, and C3H6 were measured using an Intelligent Gravimetric Analyzer (IGA-100, HIDEN, U.K.). The diffusional time constants (D′, D/r2) were calculated by the short-time solution of the diffusion equation assuming a step change in the gas-phase concentration, clean beds initially, and micropore diffusion control:

Where t (s) is the time, Mt (mmol/g) is the gas uptake at time t, Me is the gas uptake at equilibrium (mmol/g), D (m2 s−1) is the diffusivity, and r (m) is the radius of the equivalent spherical particle. The slopes of Mt/Me versus\(\sqrt{t}\) are derived from the fitting of the plots at 298 K and different adsorption pressures.

Breakthrough experimental

The breakthrough experiments were carried out in a homemade apparatus under a standard procedure. First, the samples were degassed under vacuum at 393 K for 12 h and then were introduced to the adsorption column with different sizes (0.46 cm × 15 cm or 0.46 cm × 25 cm, or 1.0 cm × 50 cm). Second, the adsorption column was connected to the homemade apparatus, and the carrier gas (He ≥99.999%) purged the adsorption column for more than 1 h to ensure that the adsorption bed was clean and saturated with He. Third, we switched the carrier gas to the desired gas mixture without any inert gas dilution (C3H4/C3H6 = 1/99, v/v, C3H6/C3H8 = 50/50, v/v, C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 = 1/1/3/95 v/v/v/v, C3H4/C3H4(PD)/C3H8/C3H6 = 25/25/25/25 v/v/v/v). Fourth, the desired gas flows through the column until the concentrations of all the components are consistent with the entrance of the gas mixture (temperature: 298 K, pressure: 1.0 bar). In this process, the eluted gas was passed to an analyzer port and analyzed using gas chromatography (GC490 Agilent) with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD), or gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC2010) with a flame ionization detector (FID). To obtain the breakthrough curves in Ft/F0 (Ft and F0 are the flow rates of each gas at the outlet and inlet, respectively), the gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC2010) with a flame ionization detector (FID) is employed, and the loop capacity of the gas chromatography is 5 mL, and its injection time is 0.3 min. Within the 0–10 mL/min range of inlet gas flow rate (F0), the injection volume would not fill up the capacity of the loop, allowing the outlet gas flow rate (Ft) of each gas to be determined from the peak area. After the breakthrough experiment, the adsorption column was regenerated at 393 K or 423 K with a 20 mL/min N2 flow rate for 10–12 h. Detailed experiment parameters like flow rates, temperatures, and column sizes are provided in every breakthrough curve.

Isotherm fitting

The pure-component isotherms of C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H6, and C3H8 were fitted using a two-site Langmuir-Freundlich model for the full range of pressure (0~1.0 bar).

Here, p is the pressure of the bulk gas at equilibrium with the adsorbed phase (bar), q is the adsorbed amount per mass of adsorbent (mmol g−1), qsat is the saturation capacity (mmol g−1), b is the affinity coefficient (bar−1), and v represents the deviation from an ideal homogeneous surface.

Isosteric heat of adsorption

The isosteric heat of C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H6, and C3H8 adsorption, Qst, defined as

were determined using the pure-component isotherm fits using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. where Qst (kJ/mol) is the isosteric heat of adsorption, T (K) is the temperature, P (bar) is the pressure, R is the gas constant, and q (mmol/g) is the adsorbed amount.

IAST calculations

The selectivity of the preferential adsorption of component 1 over component 2 in a mixture containing 1 and 2 can be formally defined as:

In the above equation, x1 and y1 (x2 and y2) are the molar fractions of component 1 (component 2) in the adsorbed and bulk phases, respectively. We calculated the values of x1 and x2 using the Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST) of Myers and Prausnitz50.

Density functional theory calculations

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using Materials Studio’s CASTEP code45. All calculations were conducted under the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof (PBE). A semiempirical addition of dispersive forces to conventional DFT was included in the calculation to account for van der Waals interactions. Cutoff energy of 544 eV and a 2 × 2 × 3 k-point mesh was found to be enough for the total energy to be covered within 0.01 meV atom−1. The structures of the synthesized materials were first optimized from the refined structures. To obtain the binding energy, the pristine structure and an isolated gas molecule placed in a supercell (with the same cell dimensions as the pristine crystal structure) were optimized and relaxed as references. C3H4, C3H4(PD), C3H6, and C3H8 gas molecules were then introduced to different locations of the channel pore, followed by full structural relaxation. The static binding energy was calculated by the equation:

Structure simulation

The high-quality Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data for Rietveld refinement of ZU-921 and ZU-922 frameworks were collected using a PANalytical Empyrean series 2 diffractometer with Cu-Ka radiation, at room temperature, with a step size of 0.01313°, a scan time of 198.65 s per step, and 2θ ranging from 5 to 90°. As indicated by the similar PXRD patterns and assembled modules, the structure of ZU-921 and ZU-922 is speculated to be isostructural to PCP-IPA except for the different substituted groups (–F, –CH3, and –H) (Fig. S2). We built the initial raw structure of ZU-921 and ZU-922 based on the framework of PCP-IPA using Material Studio. The Rietveld refinement, a software package for crystal determination from the XRD pattern, was performed to optimize the lattice parameters iteratively until the wRp value converges. The Reflex Powder Solve was employed to further optimize the atomic positions, bond length, bond angle, etc. The pseudo-Voigt profile function was used for whole profile fitting, and the Berrar-Baldinozzi function was used for asymmetry correction during the refinement processes. Line broadening from crystallite size and lattice strain was considered.

Data availability

Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2294207 (for ZU-921) and 2294206 (for ZU-922). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data that support the findings of this study are provided as a source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Liao, P.-Q. et al. Controlling guest conformation for efficient purification of butadiene. Science 356, 1193–1196 (2017).

Sholl, D. S. & Lively, R. P. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 532, 435–437 (2016).

Chen, K.-J. et al. Synergistic sorbent separation for one-step ethylene purification from a four-component mixture. Science 366, 241–246 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Designed metal-organic frameworks with potential for multi-component hydrocarbon separation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 484, 215111 (2023).

Zeng, H. et al. Dynamic molecular pockets on one-dimensional channels for splitting ethylene from C2–C4 alkynes. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 108–115 (2024).

Amghizar, I. et al. New trends in olefin production. Engineering 3, 171–178 (2017).

Ren, T. et al. Olefins from conventional and heavy feedstocks: energy use in steam cracking and alternative processes. Energy 31, 425–451 (2006).

Yang, L. et al. Energy-efficient separation alternatives: metal–organic frameworks and membranes for hydrocarbon separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5359–5406 (2020).

Li, J.-R. et al. Metal–organic frameworks for separations. Chem. Rev. 112, 869–932 (2012).

Yaghi, O. M. et al. Introduction to Reticular Chemistry: Metal-Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Yaghi, O. M. et al. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 423, 705–714 (2003).

Cao, J.-W. et al. One-step ethylene production from a four-component gas mixture by a single physisorbent. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–8 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites. Science 362, 443–446 (2018).

Liao, P.-Q. et al. Efficient purification of ethene by an ethane-trapping metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9 (2015).

Kang, M. et al. A robust hydrogen-bonded metal–organic framework with enhanced ethane uptake and selectivity. Chem. Mater. 33, 6193–6199 (2021).

Cui, X. et al. Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene. Science 353, 141–144 (2016).

Qazvini, O. T. et al. A robust ethane-trapping metal–organic framework with a high capacity for ethylene purification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5014–5020 (2019).

Jin, F. et al. Bottom-up synthesis of 8-connected three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for highly efficient ethylene/ethane separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5643–5652 (2022).

Kang, C. et al. Covalent organic framework atropisomers with multiple gas-triggered structural flexibilities. Nat. Mater. 22, 1–8 (2023).

Su, K. et al. Efficient ethylene purification by a robust ethane-trapping porous organic cage. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Selective ethane/ethylene separation in a robust microporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 633–640 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Ethylene/ethane separation in a stable hydrogen-bonded organic framework through a gating mechanism. Nat. Chem. 13, 933–939 (2021).

Bereciartua, P. J. et al. Control of zeolite framework flexibility and pore topology for separation of ethane and ethylene. Science 358, 1068–1071 (2017).

Yang, L. et al. A single-molecule propyne trap: highly efficient removal of propyne from propylene with anion-pillared ultramicroporous materials. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705374 (2018).

Li, L. et al. Flexible–robust metal–organic framework for efficient removal of propyne from propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7733–7736 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. Orthogonal-array dynamic molecular sieving of propylene/propane mixtures. Nature 595, 542–548 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Scalable green synthesis of robust ultra-microporous Hofmann clathrate material with record C3H6 storage density for efficient C3H6/C3H8 separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218590 (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Pore distortion in a metal–organic framework for regulated separation of propane and propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19300–19305 (2021).

Yang, L. et al. An asymmetric anion-pillared metal–organic framework as a multisite adsorbent enables simultaneous removal of propyne and propadiene from propylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 13329–13333 (2018).

Peng, Y. L. et al. Robust microporous metal–organic frameworks for highly efficient and simultaneous removal of propyne and propadiene from propylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10209–10214 (2019).

Li, B. et al. An ideal molecular sieve for acetylene removal from ethylene with record selectivity and productivity. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704210 (2017).

Bloch, E. D. et al. Hydrocarbon separations in a metal-organic framework with open iron (II) coordination sites. Science 335, 1606–1610 (2012).

Zhang, P. et al. Ultramicroporous material based parallel and extended paraffin nano-trap for benchmark olefin purification. Nat. Commun. 13, 4928 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Construction of fluorinated propane-trap in metal–organic frameworks for record polymer-grade propylene production under high humidity conditions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207955 (2023).

Liang, B. et al. An ultramicroporous metal–organic framework for high sieving separation of propylene from propane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17795–17801 (2020).

Cadiau, A. et al. A metal-organic framework–based splitter for separating propylene from propane. Science 353, 137–140 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Tailor-made microporous metal–organic frameworks for the full separation of propane from propylene through selective size exclusion. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805088 (2018).

Lin, J. Y. Molecular sieves for gas separation. Science 353, 121–122 (2016).

Xie, X.-J. et al. Surface chemistry regulation in Cu4I4-triazolate metal–organic frameworks for one-step C3H6 purification from quaternary C3 mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30155–30163 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Tuning metal–organic framework (MOF) topology by regulating ligand and secondary building unit (SBU) geometry: structures built on 8-connected M6 (M= Zr, Y) clusters and a flexible tetracarboxylate for propane-selective propane/propylene separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21702–21709 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Propane-selective design of zirconium-based MOFs for propylene purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 219, 115604 (2020).

Yang, S.-Q. et al. Propane-trapping ultramicroporous metal–organic framework in the low-pressure area toward the purification of propylene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 35990–35996 (2021).

Li, J.-R. et al. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504 (2009).

Zhang, P. et al. Synergistic binding sites in a hybrid ultramicroporous material for one-step ethylene purification from ternary C2 hydrocarbon mixtures. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9231 (2022).

Segall, M. et al. First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 2717 (2002).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069 (2015).

Wang, Q. et al. One-step removal of alkynes and propadiene from cracking gases using a multi-functional molecular separator. Nat. Commun. 13, 2955 (2022).

Chang, M. et al. A robust metal-organic framework with guest molecules induced splint-like pore confinement to construct propane-trap for propylene purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 279, 119656 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. Host–guest interaction modulation in porous coordination polymers for inverse selective CO2/C2H2 separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11688–11694 (2021).

Myers, A. L. & Prausnitz, J. M. Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 11, 121–127 (1965).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22122811 and 22438011), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LD25B060002), the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (No. 2024C01202), and the Research Computing Center in the College of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Zhejiang University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X., L.Y., and P.Z. conceived the project idea, designed the research, and co-wrote the manuscript. P.Z. carried out the materials synthesis, adsorption experiments, dynamic breakthrough measurements, and computational simulation. Z.Q. performed the IAST calculation, the material structure characterization, and stability testing. X.S. and X.C. conducted the cycling breakthrough experiment. Y.L. and S.C. performed the energy consumption calculation and the 10-times scale-up preparation of materials. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, P., Qiu, Z., Liu, Y. et al. One-step propylene purification from a quaternary mixture by a single physisorbent. Nat Commun 16, 11316 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66438-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66438-9