Abstract

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) play a crucial role in heterogeneous catalysis due to their efficient atomic utilization and unique catalytic properties. Despite significant progress in SAC synthesis and application, accurately identifying SACs surface features at the atomic scale remains challenging. This study employs a state-of-the-art approach combining atom-resolved secondary electron (SE) and annular dark-field (ADF) imaging using a probe-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) to investigate single vanadium (V) and tungsten (W) atoms immobilized on TiO2 nanoplatelets. Our results demonstrate that both V and W atoms are clearly visible in SE images, while only W atoms are detectable in ADF images. These findings demonstrate that SE imaging offers distinct Å-scale height contrast and atomic mass contrast for supported single atoms, greatly complementing current STEM imaging techniques in identifying surface features of nanomaterials. The combined use of ADF and SE imaging techniques enables precise identification and differentiation of supported heteroatoms, providing valuable insights into their surface topography and elemental contrast. This research highlights the utility of advanced imaging techniques in studying single-atom catalysts, thereby supporting innovations in catalyst design and application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To date, single-atom catalysts (SACs) have emerged as focal points in heterogeneous catalysis due to their exceptional ability to enhance atomic utilization efficiency and confer distinctive physicochemical properties through heteroatom-support interactions, leading to unprecedented catalytic performance1,2. Despite considerable achievements in the synthesis and applications of SACs, our comprehensive understanding of their structure-activity relationships and underlying mechanisms remains limited. This limitation stems primarily from the lack of precise geometric and surface location information for supported atoms at the atomic scale, a challenge that becomes even more pronounced in double or triple single-atom catalysts (denoted as DACs and TACs) in heterogeneous catalysis3,4,5,6. While several characterization methods available for SACs, such as EXAFS and CO-DRIFT7,8, are widely used, they suffer from limited spatial resolution and provide only averaged information. In contrast, the current microscopic approach of employing atomically resolved high-angle annular dark-field imaging with aberration corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-STEM) has become common to directly image the dispersed states of deposited single atoms on support materials9. However, directly interpreting the bright spots observed in HAADF-STEM images presents a challenge as they represent the projection of atomic columns perpendicular to the image plane10. Consequently, the enhanced brightness of single spots may be influenced by various factors, such as surface roughness, and distinguishing single atoms within bulk materials or on the surface can be difficult. Moreover, single atoms or clusters with lighter atom mass are often indistinguishable in STEM images, severely restricting the technique’ s applicability in such cases. Scanning probe microscopes (SPMs) like scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) require flat surfaces, limiting their utility for atomic-scale characterization of nanomaterials11,12. To gain a deeper understanding of the structure-activity relationship of SACs, it is crucial to develop advanced surface characterization techniques that offer higher accuracy in revealing surface atom configurations of nanomaterials regardless their size, shape and compositions.

Recent breakthroughs in atomically-resolved secondary electron (SE) imaging using probe-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) equipped with a secondary detector have opened new possibilities for surface analysis of nanomaterials at atomic scales13,14,15,16. This technique has enabled visualization of surfaces on various nanomaterials at atomic scales, such as nanocarbon-supported uranium single atoms, surpassing the spatial resolution of conventional SEM13. Unlike STEM-ADF imaging, which provides a 2D projection with collapsed z-axis information, SE imaging captures secondary electrons specifically from surface layers. The contrast in SE images stems mainly from two factors: the productivity of secondary electrons and their transmission efficiency from varying depths17,18. Consequently, atoms with higher atomic numbers (Z) or elevated surface positions appear brighter, enabling precise mapping of surface atomic structures with enhanced elemental contrast. Despite of advances in characterizing supported nanocatalysts19,20,21,22, very few studies have utilized atomically-resolved secondary electron imaging techniques in studying single-atom catalysts23,24. Expanding this technique to characterize single atoms on nano-oxides could deepen our understanding of SACs, refine catalyst design principles, and establish a robust framework for probing nanomaterial surface features. Such advancements promise transformative insights into atomic-scale surface properties, driving innovation in heterogeneous catalysis.

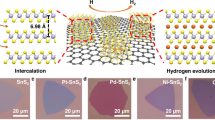

Here, well-dispersed V and W atoms on TiO₂ nanoplatelets, prepared via a wet chemical method, are studied as representative model systems for single-atom catalysts (SACs). Using a probe-corrected transmission electron microscope equipped with annular dark-field (ADF) and secondary electron (SE) detectors, we conducted ADF and SE imaging of the same regions on the TiO₂ nanoplatelets (Fig. 1). By comparing atomically resolved ADF and SE images acquired simultaneously, we found that only the heavier W atoms were more pronounced in ADF images, whereas Ti, V, and W exhibited distinct brightness differences in SE images, following the order W > V > Ti. Corroborated by simulations, we confirmed that when V and Ti have similar secondary electron yields due to their comparable atomic masses, fewer secondary electrons escape from the lower-positioned Ti atoms due to greater absorption, highlighting SE imaging’s Ångström-scale height contrast. Meanwhile, at the same height, the brightness difference between V and W arises from atomic mass contrast, as heavier atoms generate more secondary electrons. The interplay of these two factors grants SE imaging both atomic-scale height sensitivity and elemental contrast. Thus, we have developed a combined characterization method that precisely resolves the surface atomic configurations of SACs by integrating ADF and SE image analysis, providing a strategy for advancing atomic-scale characterization of nanomaterials in future research.

Results and discussion

Anatase TiO2 nanoplatelets were synthesized using the solvothermal method described in our prior research25. These nanosheets feature a distinct square shape and uniform thickness ranging from 5 nm to about 10 nm, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. Subsequently, V and W atoms were immobilized on the prepared TiO2 nanoplatelets using the hydrothermal approach mentioned earlier25. A low-magnification scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image reveals that, following the loading of V and W atoms on the support, the TiO2 nanoplatelets retain their square-shaped morphology, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Additionally, a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image confirms its anatase structure, with its (001) crystal plane perpendicular to the direction of the electron beam, as shown in Fig. 2b26. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping results confirm the uniform dispersion of V and W species on TiO2, without the formation of larger oxide nanoparticles. Moreover, when observed from a side-view perspective, the outermost layer surface appears significantly brighter than the inner part, indicating that deposited V and W atoms with identical elevation form the outermost layer on the TiO₂ surface, as supported by the EDX result (Fig. 2f, g, Supplementary Fig. S2). The averaged structure of VW/TiO₂, as shown in the k³-weighted FT EXAFS spectrum of VW/TiO₂ (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. S3), reveals a first-shell W−O bond (CN ≈ 5) and a second-shell W−V interaction at ≈3.4 Å (CN ≈ 1, Supplementary Table S1), confirming the well-dispersed V and W atoms on TiO₂. These observations provide robust evidence of the precise immobilization of individual V and W atoms onto the exceptionally flat surface of TiO2, ensuring that each atom remains distinct and non-overlapping (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, direct visualization of dispersed V-W species on the surface of TiO2 remains a formidable challenge27,28. Considering the to the atomic masses of W, V, and Ti (183.8, 50.9, and 47.9, respectively), the bright spots observed in STEM images can be unequivocally attributed to W atoms. However, the precise localization of V atoms remains uncertain, as it is widely acknowledged that single atoms with lighter or comparable atomic masses relative to the substrate are often “invisible” in HAADF-STEM or STEM-ADF images29. This instrumental limitation significantly hinders a comprehensive understanding of SACs and is particularly pronounced for newly emerging SACs, such as dual-atom catalysts (DACs), and triple-atom catalysts (TACs), from a microstructural perspective.

a Low-magnification scanning transmission electron microscope annular dark-field (STEM-ADF) image of VW/TiO2; b High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of VW/TiO2, illustrating the support’s anatase structure with the (001) crystal plane perpendicular to the incident electron beam; c Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of V and W species, along with their mixture (d), demonstrating their uniform dispersion on the TiO2 support; e Side-viewed STEM-ADF image of VW/TiO2, revealing bright outer layers with a one-atom thickness on all three TiO2 nanoplatelets; f Magnified STEM-ADF image extracted from the selected area indicated by a dotted square in (e), accompanied by an integrated EDS spectrum of the selected region (the dotted region in (f)), confirming the presence of both V and W within the one-atom-thick outer layer; g EDS mapping of the side-viewed sample, illustrating the distribution of titanium and the co-localization of V and W on the outermost surface of the TiO2 supports, respectively. h k3−Weighted Fourier Transform of the Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (FT EXAFS) spectrum of VW/TiO2. Source data are provided with this paper.

As highlighted in landmark studies by Zhu and colleagues, atomically-resolved SE imaging techniques have been instrumental in visualizing the surface topography of various nanomaterials at atomic scales, providing deeper insights into structural properties13,15,30. Experimental and theoretical results have further shown that the yield of secondary electrons in STEM exhibits a proximate Z^0.53 relationship with the atomic number, offering valuable atomic mass contrast capabilities17. However, to the best of our knowledge, this cutting-edge technique has not yet been applied to studying SACs to determine precise surface atom configurations of guest atoms. To address the challenge of identifying V atoms in the VW/TiO2 sample, we employ atomically-resolved SE imaging integrated in STEM for the distingushing V and W single atoms supported by TiO2. Complementing with STEM-ADF images acquired simultaneously, we aim to accurately determine the location and chemical identity of the supported heteroatoms, thereby providing precise microscopic evidence for understanding the surface atomic conformation of this catalyst. In the STEM-ADF image (Fig. 3a), numerous bright spots (denoted as Sa1) and some less bright, indistinct spots (denoted as Sa2) (see Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. S5a, d) can be observed on the well-crystalline TiO2 surface. While these brightest spots are supposed to be W atoms, the identification of the less bright spots as V atoms remains uncertain due to the similar atomic masses of Ti and V, making definitive differentiation challenging. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the ADF image (Supplementary Fig. S5b) confirms the predominant presence of anatase TiO2 with its (001) plane perpendicular to the incident electron beam, indicating that most deposited atoms are align with Ti atom columns.

a STEM-ADF image of VW/TiO2, and corresponding SE image b without any treatment, c filtered SE image after simple Fast Fourier Transform-Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (FFT-IFFT) treatment of (b), d magnified ADF image from the marked region in (a), e Corresponding magnified SE image from the marked region in (b), f Intensity line profiles from the regions in ADF (d) (bottom) and SE (e) (top). Source data are provided with this paper.

In contrast, the corresponding SE image offers richer information about the surface atom configurations. In the SE image, two types of spots with varying brightness are observed in addition to the surface Ti atoms, which appear as the darkest spots. Before analyzing SE images in detail, two critical factors must be considered. Firstly, the TiO2 nanoplatelet’s remarkable flatness, evidenced by the uniform contrast of Ti atoms in the SE image (Fig. 3b, c) and the side-view images (Fig. 2e, f, and Supplementary Fig. S2b, e), suggests that the observed intensity enhancement arises solely from the deposition of guest atoms either V or W. Secondly, the stability of these brighter spots under a 200 keV electron beam at a specific dose rate of 28.5 pA indicates that they correspond to the individual metal atoms, rather than imaging artifacts. These conclusions are further supported by the in-depth analysis in the subsequent simulation section. Overlaying the filtered ADF and SE images (Supplementary Fig. S5i) reveals that the brightest spots in the SE image (denoted as Ss1) coincide with the brightest spots, Sa1, in the ADF image, confirming these as W atoms (Fig. 3a, c, and Supplementary Fig. S5i). Consequently, another set of spots, marked as Ss2—brighter than Ti atoms but dimmer than W deposits—are attributed to V atoms. A comparison between SE and ADF images shows a greater number of Ss2 spots than Sa2, with Ss2 not only overlapping Sa2 but also widely distributed across the TiO₂ surface. Additionally, FFT analysis of the SE image (Supplementary Fig. S5e) confirms the dominant exposure of the (001) plane of anatase TiO₂, further verifying that all introduced atoms, including W and V, are well-aligned with the Ti atom columns.

We further analyze intensity line profiles from both ADF and SE images to highlight the observed differences in detail. The intensity profiles across the bare TiO₂ surface show consistent brightness in both ADF and SE images (Supplementary Fig. S6), indicating that all Ti atoms exhibit similar contrast in both imaging modes. In the ADF image (Fig. 2f), the line profile across the heteroatom region identifies three equally bright spots as W atoms and three dimmer spots. Again, determining whether these dimmer spots correspond to vanadium (V) atoms adsorbed on titanium (Ti) columns is challenging, as their brightness closely matches that of bare Ti columns (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. S6). In contrast, the SE image of the same region reveals three distinct atomic species based on intensity variations: The W atoms identified in the ADF image remain the brightest, while spots of equal brightness in ADF exhibit variations in SE intensity, suggesting two as V atoms and one as Ti (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, we conducted a statistical analysis of intensity variations across the atom-resolved STEM-ADF (Fig. 3a) and STEM-SE (Fig. 3b) images. By extracting and compiling histograms of the integrated intensities for individual atomic sites (Supplementary Fig. S7), we quantitatively evaluated the brightness distribution on a per-atom basis in both imaging modes, thereby providing a more rigorous and quantitative assessment of SE imaging contrast in relation to atomic identity. The ADF histogram clearly exhibits a bimodal distribution and can be deconvoluted into two distinct peaks. The second, smaller peak corresponds to 145 of the brightest atomic sites, consistent with direct visual inspection and attributable to W atoms, as previously discussed. The first, broader peak encompasses 833 atomic sites, representing an indistinguishable mixture of Ti and V atoms. In contrast, the SE histogram reveals a distinctly different distribution, with three well-resolved peaks corresponding to atomic sites with low, intermediate, and high brightness. These peaks account for 508, 328, and 145 atoms, which we assign to Ti, V, and W, respectively. This analysis confirms that, by comparing ADF and SE images, we can first identify the brightest W atoms from both modes, and then, using the enhanced contrast in SE imaging, successfully distinguish between Ti and V atoms. Thus, SE imaging provides superior surface sensitivity compared to ADF, leveraging brightness variations to precisely distinguish surface atoms with both spatial accuracy and chemical contrast.

We compared the atomically resolved SE image with the corresponding ADF image from another region to highlight the differences between the two techniques and the advantages of SE imaging for characterizing nanomaterial surfaces at the atomic level (Fig. 4). Within the outlined area (Fig. 4b, dotted rectangle), only two bright spots, assigned as W atoms, are distinctly visible in the ADF image, while other spots exhibit negligible brightness variations. In contrast, the SE image of the same region reveals a more detailed landscape, with five bright spots significantly brighter than the substrate (Fig. 4d, e, and Supplementary Fig. S8h, i). Overlaying the ADF and SE images (Fig. 4e, and Supplementary Fig. S7j, k) shows that the two W atoms identified in the ADF image align with two of the five brightest spots in the SE image, therefore, the remaining three bright spots are attributed to V atoms, which are undetectable in ADF imaging.

a STEM-ADF image and b corresponding STEM-SE image of VW/TiO2, c magnified ADF image and d corresponding SE image of the white-dotted region in (a) and (b), respectively, e colorized overlay of (c) (red) and (d) (yellow), e corresponding magnified of the same region, f intensity profiles from the selected region marked in ADF (c) (bottom) and SE (d) (top), respectively. Source data are provided with this paper.

Clearly, despite their fundamentally different generation mechanisms and collection methods, the synchronously acquired ADF and SE images exhibit both notable similarities and distinctions. This integrated STEM approach, combining SE and ADF image analysis, enables the precise determination of atomic positions (e.g., W, which appears brightest in both ADF and SE images) while also distinguishing specific heteroatoms from support atoms (e.g., V, which is indistinguishable from the TiO₂ support in ADF but shows enhanced brightness in SE). Notably, the contrast difference between V and Ti, which have similar atomic masses but different elevations, highlights Å-scale height contrast. Meanwhile, the brightness of W in SE imaging arises from both atomic mass contrast (as W and V are at the same height) and height contrast relative to Ti, underscoring the complementary strengths of SE imaging in resolving atomic-scale surface features.

In our SE imaging analysis, unlike the ADF approach, we focus on two crucial aspects: the distinct height contrast across multi-Angstroms and the significant atomic mass contrast for atoms at the same elevation. This approach effectively enables us to discern between different types of single metal atoms on support surfaces by observing contrast variations atom-to-atom, thereby providing precise atomic configurations of catalyst surface in relation to their surface-dependent activity. However, it is crucial to gain an insightful understanding of how these factors shape electron interactions and influence the microscopy imaging process. Given the extensive research by Zhu and others on secondary electron production and yield mechanisms in STEM17, numerical simulations of atomically-resolved SE images have been proved to be a reliable tool for quantitatively analyzing contrast variations between atoms observed in experiments. Therefore, we conduct atomic resolution SE simulations of TiO2 supported single V and/or W atoms, which can provide a robust foundation for affirming our observations and enhancing the trust in our research outcomes.

A simulated focused electron probe, using the experimental optical parameters (details provided in the supporting information), scans over the sample. For each probe position, the probe intensity distributions at different depths of the sample is calculated using a multislice algorithm to account for the dynamical scattering effect31. The SE emission from different atoms at a given depth is then calculated by multiplying the atoms’ object function with the calculated beam intensity distributions at that depth31. These emission signals from the same depth are then integrated to form a single pixel SE signal corresponding to that probe position, following an absorption correction. The final 2D SE image is created by scanning the probe across the sample.

The SE object function L(r) of a single atom was calculated from the angular distribution of the inelastic amplitude, following the approach of Zhu and others17. The calculated SE object functions of single W, V, Ti and O atoms are plotted in Fig. 5a (with incident beam energy 200 keV, and averaged energy loss E = 6.75 × Z, where Z is the atomic number).

a Radial profile of the SE object functions of W, V, Ti and O atoms positioned at the origin, b structure model of W and V atoms located on the (001) lattice plane of TiO2 substrate, c ADF image and e SE image of W and V atoms on the 6.8 nm TiO2 substrate, d ADF image and f SE image of W and V atoms on the 10.5 nm TiO2 substrate. Source data are provided with this paper.

For a given single probe position \({{{\bf{p}}}}\), the SE emission distributions at the depth of the nth slice \({I}_{n}^{{SE}}\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\) is written as the product of the probe intensity distributions \({I}_{n}\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\) at that depth and the SE object function \({L}_{n}\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\), where \({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}\) is a two dimensional in-plane position vector.

and the total emitted SE signal \({S}_{n}({{{\bf{p}}}})\) from the slice n according to the probe position \({{{\bf{p}}}}\) is calculated by integrating \({I}_{n}^{{SE}}\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\) across the entire plane of the nth slice.

However, the emitted SE signal will decrease due to absorption as SE travel through the sample toward the detector above. The signal drop can be modeled by an exponential factor \({T}_{n}\left({{{\bf{p}}}}\right)\)

Where \(\left|{z}_{n}-{z}_{0}\left({{{\bf{p}}}}\right)\right|\) is the thickness of the absorption layer, and \({z}_{0}\left({{{\bf{p}}}}\right)\) is the top surface of the structure. MFP denotes the mean free path of SE in absorption material. In this case, we use a uniform MFP = \(5\mathring{\rm A}\) for TiO2.

Therefore, the total SE signal emitted from different slices collected by the SE detector is thus the sum of absorption corrected signal emitted from different slices along the beam direction,

In the simulation, the specimen structure is modeled according to the experimental observations, where the TiO₂ [001] unit cell is laterally tiled to form the substrate with a z-direction thickness of 6.8 nm or 10.5 nm, and 5 W atoms and 3 V atoms are positioned on its top surface at a 1 Å distance (Fig. 5b). A corresponding ADF image under the same conditions is also simulated for comparison (Fig. 5c, d). The contrast in the ADF image is related to the sample thickness and atomic number Z 32. In the simulated ADF images (Fig. 5c, d), a well-known Z-contrast effect, where the ADF signal is proportional to the nth power of the atomic number Z, is evident, as W atoms appear much brighter than Ti and V, while the brightness of V and Ti is almost indistinguishable. The variation in thickness has little effect on the observed contrast. This observation is consistent with the experimental ADF images. In contrast, the contrast in the SE image is primarily related to the number of secondary electrons excited at the sample surface and the probability of the secondary electrons overflowing the surface potential barrier. As shown in the simulated SE images (Fig. 5e, f), the contrast of V is slightly higher than that of the neighboring Ti atoms but remains significantly lower than that of W. In contrast to the simulated ADF images, the simulated SE images clearly show that the contrast follows the order W » V > Ti, which is in good agreement with the experimental results. Although we also note that the SE brightness difference between V and W atoms in the experimental images is ~1.5-fold (see Supplementry Figs. S7, S9), which lower than the simulated twofold difference, this likely results from additional factors such as detector efficiency and other instrumental limitations that significantly influence experimental measurements. This finding is significant because it not only highlights how our approach allows for the clear identification of anchored single metal atoms but also distinguishes different elemental atoms on supports, which is critical for understanding the complex surface geometries of single-atom catalysts (SACs).

In summary, this study, we employed a combination of atom-resolved secondary electron (SE) and annular dark-field (ADF) imaging techniques using a probe-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) to investigate single vanadium (V) and tungsten (W) atoms immobilized on TiO2 nanoplatelets. Our results demonstrated that SE imaging is highly effective in identifying both V and W atoms anchored on the oxide surface, providing distinct height contrast and atomic mass contrast. In contrast, ADF imaging cannot distinguish single atoms with similar atomic masses, such as V and Ti, a common challenge encountered in most STEM studies. These findings highlight the complementary strengths of SE and ADF imaging techniques in providing detailed insights into the spatial distribution and chemical environment of single metal atoms. Although its broader application is limited by signal-to-noise constraints and the requirement to identify suitable local regions for analysis, SE imaging, in particular, proved advantages in visualizing deposited lighter atoms and offering superior surface sensitivity. This capability is critical for the accurate characterization of single-atom catalysts (SACs), as it enables the differentiation of various metal atoms on nano supports and contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of their structure-catalytic property relationship. Notably, titania-supported vanadium-based catalysts (e.g., V₂O₅–WO₃/TiO₂ and V₂O₅/TiO₂) are widely used in selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOₓ, with broad industrial and environmental significance. In these systems, vanadium serves as the primary active center, but direct atomic-scale identification of surface V atoms has long been hindered by their similar atomic mass to Ti, and structural information has typically relied on non-spatially resolved techniques such as IR, Raman, and EXAFS.25, 27 The SE imaging approach developed in this study enables direct identification of heteroatoms and their positions on the TiO₂ surface. The successful application of these advanced imaging techniques underscores their potential in driving innovations in catalyst design and application.

Methods

Characterizations

The aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) used in this work is a probe-corrected scanning/transmission electron microscope (Hitachi HF5000), which is equipped with a secondary electron (SE) detector mounted above the pole piece, enabling the simultaneous acquisition of SE, annular dark field (ADF) and bright field (BF) images with a working voltage of 200 kV. The convergence Angle is 23 mrad and ADF detector collection angle is 40–120 mrad. The imaging parameters in STEM mode: HR mapping mode using the number 4 condenser aperture whose diameter is 25 μm, the probe current is ~28.2 pA under 9 μA emission current. The pressure of the column was around 1.9 × 10−5 Pa. The image resolution is 1024*1024. This instrument was also equipped with dual Oxford Instruments XEDS detectors (2 ×100 mm2) for EDS analysis. All images in this work are raw and unprocessed unless otherwise specified. The SE detector is positioned above the objective lens to capture surface-emitted electrons for high-resolution imaging. In the Hitachi system, the detector is positively biased at 10 kV to efficiently collect low-energy secondary electrons (SE) generated at the specimen surface, enabling ultrahigh-resolution SE imaging. Additionally, a 50 eV bias is applied to fine-tune the collection ratio between SE and backscattered electrons (BSE). More details about the SE detector can be found in the literature13.

Data processing

The image processing was conducted using Digital Micrograph version 3.40. A fast Fourier transform (FFT) was first applied to the raw images, and the lattice-related diffraction spots in the FFT pattern were selected for inverse FFT (iFFT) to enhance signal-to-noise ratio by suppressing background noise. The final images were then adjusted by optimizing brightness and contrast settings. No additional filtering or image manipulation was performed beyond this standard procedure.

Simulation

For quantitative analysis, we segmented both the ADF and synchronously acquired SE images into periodic red squares of 26 × 26 pixels based on the Ti atomic lattice (Supplementary Fig. S7a, b). Due to image orientation, atomic sites in the lower-left region were excluded from the analysis. Using MATLAB, we extracted each red box, removed the boundary pixels, and calculated the integrated intensity within the central of each box. This process yielded intensity histograms for both the ADF and SE images (Supplementary Fig. S7c, d).

EXAFS

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements, including X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), were collected at beamline BL14W1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) using a 3.5 GeV electron beam with a ring current of 200–300 mA. A fixed-exit monochromator equipped with two flat Si(111) crystals was used for energy selection, while a grazing incidence mirror was employed to suppress harmonic contributions. XANES spectra were recorded with an energy step of 0.5 eV, and EXAFS data were obtained in fluorescence mode using N₂-filled ion chambers. Data processing and analysis were carried out using the IFEFFIT 1.2.11 software package.

Simulations

For STEM simulation, the beam voltage is 200 kV, and an aperture with 23 mrad semi-convergent angle and zero aberrations are used to generate the incident electron beam. The convergent beam is focused on the plane of W and V atoms, and scanned over the central area which covers laterally \(3\times 3\) TiO2 unit cells with a scanning step size \(\sim 0.1\mathring{\rm A}\). The specimen is sliced with a spacing of \(1\mathring{\rm A}\), each slice is sampled with \(512\times 512\) pixels, which corresponds to 225 mrad maximum scattering angle after 2/3 bandwidth limit in the reciprocal space, and the atomic potential is formulated using E. J. Kirkland’s fitting parameters17. The TDS effect for both elastic scattering and SE signals is modeled using frozen-phonon approximation with the mean square atomic displacements of \(0.0064{\mathring{\rm A} }^{2}\) and 32 frozen lattices in total. The elastic scattering signals are collected using high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) detector with 40~210 mrad collection angle, and the SE signals are calculated using Eqs. (4)~(7)17.

Data availability

The experiment data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, A., Li, J. & Zhang, T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 65–81 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. From single-atom catalysis to dual-atom catalysis: A comprehensive review of their application in advanced oxidation processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 351, 127989 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Tailoring atomic strain environment for high-performance acidic oxygen reduction by Fe-Ru dual atoms communicative effect. Matter 7, 1517–1532 (2024).

Hai, X. et al. Scalable two-step annealing method for preparing ultra-high-density single-atom catalyst libraries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 174–181 (2022).

Sui, C. et al. Mn/S diatomic sites in C3N4 to enhance O2 activation for photocatalytic elimination of emerging pollutants. J. Environ. Sci. 149, 512–523 (2025).

Chen, C. et al. An asymmetrically coordinated ZnCoFe hetero-trimetallic atom catalyst enhances the electrocatalytic oxygen reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2298–2308 (2024).

Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Jakub, Z. et al. Local Structure and Coordination Define Adsorption in a Model Ir(1) /Fe3 O4 Single-Atom Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 13961–13968 (2019).

Gu, F. et al. Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Methane to Methanol in Aqueous Medium over Copper Cations Promoted by Atomically Dispersed Rhodium on TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202201540 (2022).

Williams D. B. & Carter C. B. Transmission Electron Microscopy (Springer, 2009).

Therrien, A. J. et al. An atomic-scale view of single-site Pt catalysis for low-temperature CO oxidation. Nat. Catal. 1, 192–198 (2018).

Zhao, R. et al. Structure-sensitive reactivities of O/Cu(100) studied by in situ NAP-STM. Appl. Surf. Sci. 663, 160193 (2024).

Inada, H. et al. Atomic imaging using secondary electrons in a scanning transmission electron microscope: experimental observations and possible mechanisms. Ultramicroscopy 111, 865–876 (2011).

Zhu, Y., Inada, H., Nakamura, K. & Wall, J. Imaging single atoms using secondary electrons with an aberration-corrected electron microscope. Nat. Mater. 8, 808–812 (2009).

Brown, H. G., D’Alfonso, A. J. & Allen, L. J. Secondary electron imaging at atomic resolution using a focused coherent electron probe. Phys. Rev. B 87, 054102 (2013).

Saitoh, K. et al. Surface sensitivity of atomic-resolution secondary electron imaging. Microscopy 74, 28–34 (2025).

Wu, L., Egerton, R. F. & Zhu, Y. Image simulation for atomic resolution secondary electron image. Ultramicroscopy 123, 66–73 (2012).

Egerton, R. F. & Zhu, Y. Spatial resolution in secondary-electron microscopy. Microscopy 72, 66–77 (2022).

Zhang, R.-P., He, B., Liu, X. & Lu, A.-H. Hydrogen spillover-driven dynamic evolution and migration of iron oxide for structure regulation of versatile magnetic nanocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25834–25841 (2023).

Xu, M. et al. Boosting CO hydrogenation towards C2+ hydrocarbons over interfacial TiO2−x/Ni catalysts. Nat. Commun. 13, 6720 (2022).

Qin, X. et al. Direct conversion of CO and H2O to hydrocarbons at atmospheric pressure using a TiO2−x/Ni photothermal catalyst. Nat. Energy 9, 154–162 (2024).

Lewis, R. J. et al. Highly efficient catalytic production of oximes from ketones using in situ–generated H2O2. Science 376, 615–620 (2022).

Lin, L. et al. Reversing sintering effect of Ni particles on γ-Mo2N via strong metal support interaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 6978 (2021).

He, B., Tao, X., Li, L., Liu, X. & Chen, L. Environmental TEM Study of the Dispersion of Au/α-MoC: From Nanoparticles to Two-Dimensional Clusters. Nano Lett. 23, 10367–10373 (2023).

Qu, W. et al. An Atom-Pair Design Strategy for Optimizing the Synergistic Electron Effects of Catalytic Sites in NO Selective Reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202212703 (2022).

Ek, M., Ramasse, Q. M., Arnarson, L., Georg Moses, P. & Helveg, S. Visualizing atomic-scale redox dynamics in vanadium oxide-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 8, 305 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Coverage-dependent behaviors of vanadium oxides for chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 22072–22079 (2020).

Kim, T., Burrows, A., Kiely, C. & Wachs, I. Molecular/electronic structure–surface acidity relationships of model-supported tungsten oxide catalysts. J. Catal. 246, 370–381 (2007).

Tieu, P., Yan, X., Xu, M., Christopher, P. & Pan, X. Directly probing the local coordination, charge state, and stability of single atom catalysts by advanced electron microscopy: a review. Small 17, 2006482 (2021).

Hwang, S. et al. Secondary-electron imaging of bulk crystalline specimens in an aberration corrected STEM. Ultramicroscopy 261, 113967 (2024).

Kirkland, E. J. Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy, 2nd ed. (Springer, 2010).

Yamashita, S. et al. Atomic number dependence of Z contrast in scanning transmission electron microscopy. Sci. Rep. 8, 12325 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1500300, 2022YFA1504800), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22072090, 22272106, 62171136, 22476022 and 22276037). XAS at the W L3-edge was performed at beamlines BL14W1 and BL16U1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.R. performed TEM data acquisition and analysis, X.Li. and X.Z. completed the simulation, D.X. synthesized the samples and complete the XAS analysis. G.Z., X.T., C.Z. and L.C. participated in the discussion. X.Liu. initiated and supervised this project, Z.R. and X.Liu. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, Z., Li, X., Xu, D. et al. Discerning single atoms on TiO2 nanoplatelets using STEM-based atomically-resolved secondary electron techniques. Nat Commun 16, 11360 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66442-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66442-z