Abstract

Brown adipocytes facilitate non-shivering thermogenesis, which is critical for maintaining energy balance and heat production in response to environmental stimuli. Here, we delineate the physiological and biochemical role of etoposide-induced 2.4 (Ei24) in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. We generated Ei24 adipocyte-specific knockout (EiaKO) mice that exhibited brown adipose tissue hypertrophy, lipid accumulation, and various mitochondrial abnormalities. Despite mitochondrial defects, uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression and activity remained unchanged. However, those impairments caused lethal hypothermia in mice subjected to cold challenge, underscoring the key role of Ei24 in mitochondrial functions. Mechanistically, Ei24 deficiency disrupted cristae structure, dissipated mitochondrial membrane potential, and reduced matrix pH, leading to severe ATP depletion. We further identify the C-terminal region of Ei24 as essential for supporting ATP synthase function. Those bioenergetic defects not only destabilized the mitochondrial environment necessary for efficient UCP1-mediated thermogenesis, but also impaired ATP-dependent futile cycles such as SERCA-mediated calcium cycling and creatine substrate cycling. Together, our findings indicate that Ei24 functions as a thermogenic regulator that ensures mitochondrial ATP synthesis and structural integrity, enabling both coupled and uncoupled respiration in brown adipose tissue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unlike white adipocytes, brown adipocytes are specialized in energy expenditure and are distinguished by their characteristic brown hue due to an abundance of mitochondria. These cells engage in sequential energy-consuming processes, particularly in response to cold exposure or hormonal cues1,2,3. Facilitating mitochondria-dependent thermogenesis, brown adipocytes metabolize stored fat to generate heat, making them pivotal for thermoregulation4. Moreover, in addition to their role in thermogenesis, brown adipocytes act as metabolic hubs, adapting to physiological demands and environmental shifts5,6.

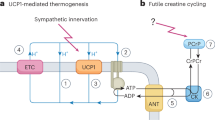

A hallmark of brown adipocyte mitochondria is their expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which is central to their thermogenic function7,8. UCP1 is responsible for the uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in mitochondria9. It utilizes the proton gradient created by the electron transport chain (ETC) to drive heat generation instead of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis10, which allows brown adipocytes to regulate body temperature efficiently during cold exposure.

The activity of UCP1 is tightly regulated by various factors, including fatty acids, purine nucleotides, and hormonal or environmental stimuli11,12,13,14. Furthermore, the integrity and activity of these mitochondria are critical for their effective heat production15. These regulatory mechanisms and background environment highlight the adaptability of brown adipocytes to external demands. Thus, proper regulation of UCP1 expression is pivotal, as its thermogenic activity has been linked to metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes by facilitating stored lipid sources16,17.

The etoposide-induced 2.4 kb (Ei24) transcript, also known as p53-induced gene 8 (PIG8), was identified as a target gene of p5318. The role of Ei24 as a tumor suppressor is evident based on its impact on cancer cell proliferation and survival, which stems from its interactions with key apoptotic regulators, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target in oncology19,20,21. Further investigations revealed a significant role of Ei24 in basal autophagy, which is essential for cellular homeostasis22,23. In subsequent studies, the involvement of the Ei24 protein in degrading RING E3 ligases via autophagy was investigated22,24. Additionally, its regulatory impact on metabolic processes suggests that it plays a major role in maintaining energy homeostasis and contributing to metabolic diseases25. These insights underscore the diverse functional spectrum of Ei24, ranging from fundamental cellular processes to key implications in disease pathogenesis, including in cancer and metabolic disorders. Specifically, gene set enrichment analysis of tumor datasets from melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and breast cancer revealed that tumors with high Ei24 expression were significantly enriched for hallmark gene sets related to fatty acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 1a-c). Furthermore, gene set analysis in adipocytes showed strong association between Ei24 expression and gene networks involved in adipogenesis and fatty acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 1d). These observations prompted us to investigate the physiological role of Ei24 in metabolically active tissues, particularly brown adipose tissue, where fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial thermogenesis are critical.

In this study, we explored the role of Ei24 in brown adipocytes and demonstrated its involvement in mitochondrial respiration and thermogenesis within brown adipocytes. Notably, this function of Ei24 is independent of UCP1 expression and its activity, revealing an additional layer of complexity in brown adipocyte thermogenesis and metabolism.

Results

Adipocyte-specific depletion of Ei24 induces brown adipose tissue hypertrophy

To understand the role of Ei24 in mature adipocytes, we generated Ei24-conditional knockout mice (EicKO) using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system (Fig. 1a). EicKO mice were then crossed with transgenic mice expressing adiponectin-specific Cre recombinase, where Cre activity was controlled by the adipose tissue-specific adiponectin promoter (Ei24f/fAdipoqCre, hereafter EiaKO mice)26. Elimination of the Ei24 gene was confirmed by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based amplification, DNA sequencing, and protein and mRNA expression analyses (Fig. 1b,c). In EiaKO mice, both the mRNA- and protein-expression levels of Ei24 were specifically attenuated within adipose tissues, including brown adipose tissue (BAT), inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT), and epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT).

a Schematic diagram showing the gene constructs used to generate Ei24f/f AdipoqCre mice. Exons 3–10 of Ei24 were floxed, and the mice were crossed with transgenic mice expressing Adiponectin-Cre. Ei24 protein abundance (b) and, mRNA expression (c) was analyzed in tissues from 16-week-old male, wild-type control (Ei24f/f) and EiaKO (Ei24f/f AdipoqCre) mice. For reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) analysis, five biologically independent samples grouper group (wild-type control and EiaKO) were analyzed, and results were normalized to Actb mRNA expression. Body weight (d) and tissue weight-to-body weight ratios (e) were measured for various adipose tissue depots (iBAT, iWAT, and eWAT) in control and EiaKO mice (n = 5 mice per group). f Representative images of dissected iBAT and iWAT from 16-week-old male and female wild-type control and EiaKO mice were obtained. g Cross-sectional areas (cm2) of BAT samples represented in f (n = 3 biological replicates per group, scale bar, 10 mm). The data shown represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses of the data presented in panels (c–e) and (g) were performed using two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Ei24 depletion did not significantly alter the body weights of mice of either sex (Fig. 1d). Notably, in both male and female EiaKO mice, the proportional weight of interscapular brown adipose tissue (iBAT) increased by >2-fold when normalized to body weight (Fig. 1e). In contrast, the average weights of both iWAT and eWAT in the EiaKO mice did not differ significantly from those of wild-type mice. Notably, the volume and cross-sectional area of brown adipose tissue correlated with increased weights (Fig. 1f, g). Taken together, these data suggest that targeted depletion of Ei24, specifically in adipocytes, triggered hypertrophy in BAT but not in iWAT and eWAT.

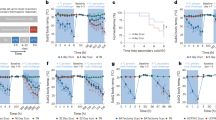

Physiological and metabolic effects of Ei24 KO, leading to lethal hypothermia

As we observed distinctively enlarged iBAT, which is responsible for non-shivering thermogenesis, we next investigated the thermogenic capability of EiaKO mice. Thermoregulation in cold conditions was assessed by monitoring the core body temperatures of mice in a 4 °C environment (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, all EiaKO mice experienced significant hypothermia and failed to survive acute cold stress, whereas the wild-type mice survived, exhibiting only a minor decrease in body temperature (Fig. 2b, c). The absence of innate thermal adaptation in EiaKO mice suggests that the Ei24 gene influenced thermogenic efficiency. However, Ei24 depletion in adipocytes did not affect the overall lifespan of mice under normal housing conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b).

a Experimental schedule for acute cold stress following a 6 h pre-fasting period. b Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of 16-week-old male wild-type and EiaKO mice exposed to a 4 °C cold environment after 6 hours of fasting. (n = 10 mice per group). c The core body temperatures of wild-type control and EiaKO mice were monitored via rectal thermometry during cold exposure (n = 10 biological mice per group). Mice were euthanized if their core body temperature dropped below 30 °C. d H & E staining of BAT was performed before and after the mice were exposed to a cold environment (4 °C for 2 h without pre-fasting). Scale bars, 100 µm. e The body weight of each mouse was measured before and after a 6 h fasting period and then again after a h cold exposure (n = 6 mice per group). f Serum free fatty acid concentrations of wild-type and EiaKO were measured before and after cold exposure (n = 6 mice per group). Note that mice used in Fig. 2b, c were distinct from those used in Fig. 2e,f and Supplementary Fig. 2d. Experimental conditions also differed between groups, as detailed in Fig. 2a. g Western blot analysis of protein lysates from BAT was performed to evaluate the expression levels of UCP1 and phosphorylated PKA substrates in both wild-type and EiaKO mice before (naïve) and after (cold) exposure to a cold environment (4 °C for 2 h without pre-fasting). Representative results reproduced independently at least twice. h Thermal images (top panel) and quantitated average surface temperatures (bottom panel) of 12-week-old wild-type and EiaKO mice were obtained 1 h after intraperitoneal administration of saline or 1 mg/kg CL316,243 (n = 4 mice per group). The data shown represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for b two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for c and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests for e, f and h.

EiaKO BAT, characterized by the WAT-like unilocular shape of lipid droplets (LDs), exhibited diminished lipid utilization during the cold challenge, in contrast to the significant LD shrinkage observed in wild-type BAT (Fig. 2d). This pronounced difference in the remaining triglyceride (TG) content suggested that knocking out Ei24 impaired the mitochondrial thermogenic system or decelerated fuel-supply mechanisms, including lipolysis, fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and tricarboxylic acid cycling.

Wild-type and EiaKO mice exhibited similar body weight reductions after a 6-hour fast (Fig. 2e). During this fasting period, both groups also showed a comparable, gradual decline in core body temperature, suggesting that shivering thermogenesis was initially sufficient to maintain thermal homeostasis in the absence of cold stress (Supplementary Fig. 2c). However, after 6 hours of fasting, EiaKO mice began to exhibit a more pronounced drop in body temperature compared to wild-type controls. This delayed hypothermic response indicates that prolonged metabolic stress progressively overwhelms the thermogenic capacity of EiaKO mice.

During subsequent cold exposure with ad libitum access to food, the EiaKO mice regained their body weight more effectively, despite having chow-consumption rates comparable to those of wild-type mice (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2d). This weight gain in EiaKO mice suggests an inefficient conversion of food intake into heat, indicating that thermogenesis was impaired in the absence of Ei24. We hypothesized that the LDs stored in BAT were not effectively converted into heat, resulting in excess body weight, highlighting the energy-utilization gap in EiaKO mice. This hypothesis was further supported by the increased levels of circulating free fatty acid (FFA) in the serum (Fig. 2f).

Glucose tolerance test (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) did not reveal any significant differences between wild-type and EiaKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), indicating that glucose utilization and insulin sensitivity were unaffected in the EiaKO mice. The similar outcomes in GTT and ITT suggested that other mechanisms, independent of glucose homeostasis, were responsible for the thermoregulatory deficiencies observed in EiaKO mice. Although extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), a proxy for glycolytic activity, was elevated in EiaKO brown adipocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h), this compensatory glycolytic activation appeared insufficient to significantly impact systemic glucose homeostasis. This likely reflects the relatively low metabolic burden of BAT under basal conditions.

To further assess the systemic metabolic consequences of Ei24 deficiency under non-stressful conditions, we performed metabolic cage analyses in both male and female EibKO mice (Ei24f/fUcp1Cre, hereafter EibKO mice). These experiments revealed no significant differences in respiratory exchange ratio (RER) or energy expenditure between wild-type and EibKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). Consistent with this, glucose and insulin tolerance tests also showed no significant alterations (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), indicating that glucose utilization and insulin sensitivity are largely maintained in EiaKO mice. These findings suggest that the basal metabolic contribution of BAT is limited and that Ei24 deficiency impairs thermogenesis primarily under environmental or metabolic stress, rather than disrupting systemic metabolic homeostasis under baseline conditions.

During cold exposure, β₃-adrenergic signaling activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates downstream target proteins, leading to the induction of UCP1 and other thermogenesis-related genes7. Since previous reports suggesting that dysfunctional in vivo thermogenesis is linked to disrupted UCP1 expression27,28, we hypothesized that alterations in this signaling pathway in EiaKO mice might contribute to reduced thermogenesis. However, PKA-substrate phosphorylation levels in EiaKO remained comparable to wild-type under cold exposure (Fig. 2g), indicating that β₃-AR/PKA activation remained intact. In addition, both wild-type and EiaKO mice exhibited similar UCP1 expression levels before and after cold exposure. These findings indicate that thermogenesis is not solely regulated by UCP1 levels but involves a complex interplay of multiple factors.

Reduced heat generation in the interscapular region was observed in EiaKO mice following injection of CL316,243 (Fig. 2h), a β₃-adrenergic receptor agonist that mimics cold-induced thermogenesis. This occurred despite UCP1 expression levels remaining comparable between EiaKO and wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 3e). These findings suggest that Ei24 plays a crucial role in regulating the body temperature in mice and underscore the importance of further investigating its function in lipid metabolism.

Ablating adipocyte Ei24 induces lipid-droplet accumulation in BAT

Genetic ablation of Ei24 in adipocytes resulted in the formation of enlarged LDs in BAT (Fig. 3a). Analyzing the size distribution, based on quantified data from hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining, revealed a significant increase in the size of LDs in brown adipocytes from EiaKO mice (Fig. 3b). Unlike normal brown adipocytes, which typically contain multiple small LDs, those found in EiaKO mice were considerably larger but fewer in number (Fig. 3b, c). This transition towards a WAT-like phenotype in brown adipocytes prompted us to investigate their lipolytic and lipogenic functions.

a H & E staining of BAT from 16-week-old wild-type control and EiaKO mice. Scale bars, 100 µm. b Size distribution of lipid droplets (LDs) in BAT from control and EiaKO mice. The graph shows quantitative analysis of H & E staining data obtained using ImageJ. Sizes of over 1000 LDs were counted for each genotype. c Average LD size (left panel) and total LD counts (right panel) normalized to the number of nuclei (hematoxylin dots). were quantified from H&E BAT sections (400x magnification). For wild-type control, 2502 LDs were analyzed across 190 nuclei and 544 LDs were analyzed across 290 nuclei for EiaKO. Western blot analysis was conducted to analyze the expression levels of proteins related to lipolysis (d) and lipogenesis (e) in BAT lysates obtained from wild-type mice and EiaKO mice. f Lipolytic and lipogenic rates in differentiated stromal vascular fractions (SVFs) from wild-type and EiaKO mouse BAT were determined by measuring intracellular TG and glycerol levels over time. 10 μM isoproterenol and 1 μg/ml human insulin were used to stimulate in vitro lipolysis and lipogenesis, respectively. Glycerol measurements reflect free glycerol concentration only (n = 3 biological replicates per group; each with 3 technical replicates). g Exogenous fatty acid oxidation (FAO) rate (left panel) and the calculated basal and maximal FAO rates in differentiated wild-type and EiaKO SVFs (right panel). PA: palmitate, ETO: etomoxir. The data shown represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for c, f and g.

Regardless of the tissue type (WAT or BAT), adipose tissue serves as a primary site for storing and breaking down lipid-based nutrients in response to energy demand. Thus, we hypothesized that the dysregulation of either catabolic or anabolic pathways was responsible for the altered LD size and shape resulting from Ei24 depletion. To explore this, we first examined the expression of the lipolytic enzymes, such as adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which participate in the rate-limiting steps of adipose TG hydrolysis. Although the protein and mRNA expression levels of ATGL were elevated in BAT lysates from EiaKO mice (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), the HSL-phosphorylation levels at S660 and S563, which are critical for its enzymatic activity29, remained unchanged. Thus, we did not find any evidence of significantly reduced lipolytic activity that may have contributed to the formation of larger LDs.

Given the lack of major changes in lipolysis, we next examined factors involved in fatty acid handling and synthesis. However, the absence of any change in the expression levels of fatty acid synthase (FASN) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) ruled out this possibility (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Although PPARγ, a key transcriptional regulator of adipogenesis and lipid metabolism, showed only a modest increase in EiaKO BAT, the elevated levels of its downstream target FABP4 suggested a compensatory response to lipid overload resulting from impaired mitochondrial fatty acid utilization (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4c)30,31. Given the role of FABP4 in intracellular fatty acid trafficking and buffering, we speculated that its upregulation may reflect feedback activation of PPARγ signaling under metabolic stress. Accordingly, we further examined whether enhanced lipogenesis contributes to the observed lipid accumulation in EiaKO BAT.

To further examine lipid metabolism, the in vitro lipolytic and lipogenic rates were assessed by quantitative analysis of cellular TG and free glycerol concentrations after isoproterenol and insulin treatment (Fig. 3f). The initial TG concentrations were elevated in differentiated EiaKO stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells, mirroring the lipid accumulation observed in BAT from EiaKO mice. Nevertheless, ablating Ei24 did not significantly alter the rate of lipolysis, as indicated by the free glycerol, which is a byproduct of TG breakdown. Despite ATGL upregulation in EiaKO BAT, lipolysis appeared to depend more on HSL expression and phosphorylation. Similarly, the rate of TG synthesis in the absence of Ei24 was similar to that observed in wild-type brown adipocytes. Thus, it appears that neither altering the lipolytic rate nor the lipogenic rate directly influenced the increase in LD sizes in BAT from EiaKO mice.

Metabolic adaptation and FAO dysfunction in EiaKO mice

The balance between lipogenesis, lipolysis, and FAO in BAT determines its overall lipid content and influences its ability to dissipate energy as heat32. Therefore, we examined FAO in EiaKO mice. The levels of Cpt1a, a rate-limiting enzyme that regulates the rate of FAO, were not significantly altered in the naïve state of EiaKO BAT compared to that in wild-type BAT (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4a). We analyzed the overall expression of FAO-related genes under naïve and cold-stimulated conditions to assess how the pathways responded to increased energy demands. The expression of FAO-related genes, including that of Cpt2 and mitochondrial acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (Vlcad, Lcad, Mcad, and Scad), was less responsive to environmental stimuli (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Notably, the basal level of Cpt1a was higher in naïve EiaKO mice. However, the anticipated increase in Cpt1a expression upon cold stimulation was not observed in the EiaKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 4d), suggesting that the adaptive response of the FAO pathway was impaired under thermogenic stress.

The FAO rate was assessed by measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) following the supply of palmitate (a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid) as a substrate in the presence or absence of etomoxir, which inhibits CPT1 activity. Interestingly, the adipogenic differentiation-induced SVF extracted from BAT of EiaKO mice showed lower exogenous and endogenous FAO than the corresponding SVF from wild-type mice (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4e). The results suggested that significant alterations occurred in metabolic pathways, particularly those regulating β-oxidation, in EiaKO BAT. Overall, these findings highlight the profound effects of mitochondrial anomalies on cellular energy homeostasis.

Ei24 ablation induced crista dysmorphia and abnormal mitochondrial accumulation

We further determined whether this biochemical defect was associated with the structural phenotype of mitochondria in EiaKO BAT. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that the expanded cytosolic area of EiaKO brown adipocytes was filled with small dysmorphic mitochondria (Fig. 4a). The loss of Ei24 disrupted the structures of cristae, with approximately 57% of mitochondria from EiaKO BAT showing broken or empty ultrastructure (Fig. 4a, b). As evident in the TEM images, the quantified mitochondrial area within the brown adipocytes of EiaKO mice was significantly reduced (p < 0.001) to less than half of that in wild-type brown adipocytes (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, along with these morphological abnormalities, the number of mitochondria was nearly 2-fold higher in EiaKO BAT. Correspondingly, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number per nuclear DNA count (which represents the abundance of mitochondria) also increased in the BAT of EiaKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To elucidate the potential molecular mechanisms underlying the observed mitochondrial dysfunction and accumulation, we assessed the expression levels of key proteins involved in mitochondrial biogenesis using western blot (WB) analysis. The expression of PGC1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis33, was similar in BAT from both wild-type and EiaKO mice (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 5b), suggesting that the increased mitochondrial abundance was not due to heightened mitochondrial biogenesis. This possibility was further corroborated by a substantial decrease in the expression of PRDM16, a protein crucial for regulating brown fat cell identity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Increased mitochondrial levels of transcription factor A (TFAM) may indicate a cellular attempt to manage or rectify mitochondrial dysfunction, which was apparent in their morphology. We interpreted increased voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) in EiaKO BAT as a marker of mitochondrial abundance per cell. Although previous results have underscored the critical role of Ei24 in maintaining the integrity of mitochondria-associated membranes and their interactions with VDAC134, we did not investigate the changes in VDAC1 in detail.

a Intracellular structures of brown adipocytes from control and EiaKO mice were observed using transmission electron microscope (TEM) (n = 3 biological replicates per group). Top panels show overviews (scale bar: 10 µm) and enlarged views (scale bar: 2 µm). 3k and 12k represent 3000x and 12,000x TEM magnitude respectively. Bottom panel presents enlarged images from a different representative field (scale bar: 2 µm). Variations in mitochondria morphology are denoted by color-coded arrow heads: normal mitochondria (green), small mitochondria (yellow), and broken mitochondria (red). b Average number of BAT mitochondria from wild-type and EiaKO mice are shown for each morphological category. Each bar represents the average number of mitochondria within randomly selected cytosolic area in analyzed images (n ≥ 5 images from 3 biological replicates per group). The mitochondria are classified into three categories based on the observed morphology. Normal: mitochondria exhibiting a morphology comparable to the predominant form observed in wild-type samples. Small: mitochondria of size smaller than 50% of those in the normal category. Broken cristae: mitochondria whose cross-sections showed >50% loss in the ultrastructure. c Average size (2-dimensional area) of the mitochondria was calculated using ImageJ. In total, 176 mitochondria from wild-type mice and 136 from EiaKO mice were analyzed. d Western blot analysis of protein lysates from BAT obtained from wild-type and EiaKO mice. e Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was assessed using the 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1) dye (left panel). Resting ΔΨm was quantified as the JC-1 ratio (590/520; right panel). f Mitochondrial matrix pH was measured in differentiated BAT. The pH of the resting mitochondrial matrix was quantified (right panel). Figure e and f show representative results of four independent biological replicates per group. Each experiment included 4 technical replicates for e and 10 technical replicates for f. g Cellular ATP concentrations in differentiated BAT SVFs from wild-type and EiaKO mice (n = 6 biological replicates per group) treated with either glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) or mitochondrial respiration inhibitor Oligomycin (Oligo), or both. h Cellular ATP concentrations were assessed in differentiated BAT SVFs (n = 3 biological replicates per group) following a 6-h treatment with the autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ). The relative luminescence units (RLUs) were normalized to the measured protein concentrations from equally cultured and differentiated cells. The data shown represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA for b unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for c, e–g, and one-way ANOVA for h.

The proton-motive force (PMF) across the mitochondrial inner membrane was measured to evaluate the overall functionality and health of mitochondria in brown adipocytes ex vivo. Our findings revealed significant depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in EiaKO compared with that in wild-type cells (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, we observed a pronounced decrease in the mitochondrial matrix pH in EiaKO cells (Fig. 4f), suggesting that protons accumulated within the mitochondrial matrix rather than migrating to the intermembrane space, resulting in depolarization34.

To comprehensively assess the OXPHOS capability of mitochondria, we measured ATP concentrations and tracked the origin of ATP. ATP levels were significantly reduced in differentiated brown adipocytes derived from BAT SVFs of EiaKO mice than those in wild-type control cells (Fig. 4g). Moreover, treatment with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), a glucose analog that inhibits glycolysis, further diminished the overall ATP levels in EiaKO BAT. These findings suggest that ATP production in EiaKO BAT primarily occurs via the glycolytic pathway, and this was further supported by the increased ECAR (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h). This increase in glycolytic rate of EiaKO cells suggests that a compensatory mechanism counterbalances the reduced ATP production in cells lacking Ei24 with impaired mitochondria.

In addition, white adipocytes in EiaKO mice exhibited substantial expansion of the cytosolic area and an increase of the morphologically defective mitochondrial population within (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Additionally, we observed significantly lower ΔΨm and mitochondrial matrix pH values, which correlated with reduced cellular ATP concentrations in iWAT from EiaKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c–e). These iWAT alterations mirrored the mitochondrial dysfunction and morphological changes observed in BAT.

As the failure of removal of old and defective mitochondria leads to severe cellular dysfunction35, we next investigated whether mitophagy was impaired in Ei24 depleted-BAT. Mitophagy was assessed using mt-Keima, a pH-dependent fluorescent probe that detects mitochondria within autolysosomes. Following treatment with the mitophagy activator carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), the fluorescence signals indicating active mitophagy activity were considerably lower in mature EiaKO brown adipocytes than those in wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). To determine whether Ei24 might regulate mitochondrial respiration independently of its conventional role in autophagy, we examined the effect of autophagy ablation on ATP synthase activity. Our results showed that treatment with the autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine, did not alter the cellular ATP concentration (Fig. 4h), indicating that ATP synthase activity was relatively unaffected during acute autophagy inhibition. This finding suggests that although Ei24 ablation contributed to the accumulation of malfunctioning mitochondria by inhibiting mitophagy, Ei24 potentially played an autophagy-independent role in regulating cellular energy production.

Ei24 is essential for proper ATP synthase function

Considering that Ei24 depletion disrupted the mitochondrial PMF and cellular ATP concentration in BAT, we investigated the potential protein–protein interactions of Ei24 with the OXPHOS machinery. Based on our previous mass spectrometry analysis of Ei2436, we identified a potential interaction between the Ei24 protein and eight different subunits of the ATP synthase complex. Immunoprecipitation followed by WB analysis confirmed protein–protein interactions between Ei24 and ATP5A/B (Fig. 5a) in differentiated wild-type SVFs. None of the representative proteins of complexes I–IV showed any physical interactions with Ei24 under the same conditions. Furthermore, the Ei24–ATP5A/B interaction was enhanced in the presence of forskolin, and isoproterenol potentially activated mitochondrial activity, leading to PKA activation (Fig. 5b). This protein–protein interaction suggests a potential role for Ei24 in the mitochondrial ATP-synthesis pathway, affecting the efficiency and regulation of ATP production in brown adipocytes. Thus, understanding these molecular interactions is critical for explaining the functional impairments observed in EiaKO cells, particularly in terms of energy metabolism and thermogenic responses.

a Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of endogenous Ei24. Differentiated SVF lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-Ei24 antibody and then blotted with either total OXPHOS cocktail antibody (upper panel) or an anti-ATP5B antibody (lower panel). b Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis of endogenous Ei24 after treatment with or without isoproterenol or forskolin. WD indicates lysates prepared after 1 h treatment of followed by washing and incubation for an additional 1 h in the absence of forskolin or isoproterenol. The lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-Ei24 antibody and subsequently blotted using an OXPHOS cocktail antibody. c Schematic of Ei24 truncation and deletion constructs. d Cellular ATP concentrations in differentiated BAT SVFs from wild-type and EibKO mice (n = 3 biological replicates per group) after transfected with full-length Ei24 (FL) or the indicated truncation (F1–F4) and deletion (Δ1–Δ4) mutants. e Immunoblot analysis EI24 in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions isolated from BAT of wild-type mice under basal conditions or following 2-hour cold exposure (4 °C) CYCS (cytochrome c) and VINCULIN were used as markers for mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively. f Immunofluorescence staining of differentiated brown adipocytes for Ei24 (green) and mitochondria (stained with Mitotracker Red, displayed as magenta for visualization) in differentiated SVFs isolated from wild-type mice treated with vehicle or CL316,243 (n = 3 biological replicates per group; scale bar, 20 μm). Manders’ overlap coefficients analysis between Ei24 and Mitotracker Red signals (right panel). g Mitochondrial OCRs of differentiated BAT SVFs derived from BAT of 8-week-old wild-type and EiaKO mice (n = 3 biological replicates per group; each with 3 technical replicates) treated with the β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, CL316,243 (left panel). The basal and maximal OCRs were quantified (right panel). h Cellular ATP concentration changes were measured after control vehicle or CL316,243 treatment. Cells were treated with 1 µM FCCP or 5 µM Oligomycin, as indicated. The cells were washed twice with saline after withdrawing the indicated reagents (n = 3 biological replicates per group). i GDP-inhibited oxygen consumption of isolated mitochondria from BAT were measured. Following baseline measurement, 100 µM palmitates were injected to stimulate activity, and 5 mM GDP was subsequently added to inhibit UCP1 activity. The data represents the difference in OCR between the baseline and GDP-treated conditions, calculated to reflect UCP1-specific inhibition (n = 6 biological replicates per group). j ER calcium uptake capacity in differentiated BAT SVFs (n = 3 biological replicates per group; cultured SVFs are obtained from 12-week old male mice) assessed using F-erCEPIA sensor following CDN1163 treatment. Ei24-deficient cells exhibited a blunted calcium accumulation, suggesting impaired SERCA-mediated calcium cycling. k mRNA expression of creatine cycling–related genes (Ckb, Ckm, Ckmt1, Ckmt2) in BAT under basal and 2 h cold-stimulated conditions (n = 4/group, 12-week-old male mice). RT-qPCR results were normalized to Actb mRNA-expression levels. l ATP concentrations and ADP: ATP ratios were measured over time in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) obtained from Ei24f/f mouse embryos following adenoviral transduction with Cre (n = 4 biological replicates per group; each with 3 technical replicates). Luminescence was accessed in four replicate wells with a single cell line (left panel). Western blot analysis of MEF lysates transfected with pCDNA3.1-Cre (right panel). The data shown represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA for d, g, k, one-way ANOVA for i and a two-tailed Student’s t-test for f, j. Figure a, b and e show representative results which consistently reproduced at least twice.

To further investigate the molecular basis of Ei24 in mitochondrial ATP synthesis, we performed domain mapping analysis using a series of Ei24 truncation and internal deletion (Fig. 5c). Among the four deletion constructs tested, only the construct containing the C-terminal region (aa 293–340; Fragment 4) was capable of rescuing ATP production in Ei24-deficient cells to levels comparable to full-length Ei24 (Fig. d). while internal deletion of this region (Δ4) abolished the ability of Ei24 to restore ATP production. Notably, this functional region lies outside of the predicted transmembrane domain (aa 80–282)37, suggesting that the matrix-facing portion of Ei24 is critical for modulating ATP synthesis.

To determine whether Ei24 localizes within mitochondria, we conducted two independent assays. Subcellular fractionation followed by immunoblotting demonstrated that the presence of Ei24 was increased in the crude mitochondrial fraction of BAT isolated after 2 h cold exposure at 4 °C (Fig. 5e). Additionally, immunocytochemistry (ICC) using the mitochondria-specific marker (MitoTrackerTM Red) demonstrated an increase in co-localization of Ei24 with the mitochondrial structures after CL316,243 treatment (Fig. 5f). These findings further support the presence of a mitochondrial pool of Ei24 and are consistent with its interaction with ATP synthase subunits.

Changes in mitochondrial structures and number reflect alterations in bioenergetics and mitochondrial metabolic activities38. Therefore, we hypothesized that Ei24 depletion could promote mitochondrial dysfunction in BAT under cold exposure. To test this hypothesis, we assessed mitochondrial ETC activity by measuring the OCR of primary BAT cells. Under basal conditions, EiaKO cells exhibited higher maximal OCRs compared to wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 7c). This finding suggests that in the absence of Ei24, increased proton leakage may occur, leading to inefficient respiration, reduced ATP production, and oxygen consumption rates that remain comparable to those of wild-type cells despite underlying dysfunction. However, after CL316,243 treatment, EiaKO cells showed a significantly lower OCR than wild-type cells (Fig. 5g), indicating that overload stress affecting the respiratory chain of Ei24-depleted cells. Moreover, EiaKO cells demonstrated reduced flexibility in modulating ATP synthesis under β3-adrenergic stimulation, whereas wild-type cells effectively adjusted energy production by decreasing ATP synthesis to meet the increased demand for heat generation (Fig. 5h).

Furthermore, mitochondria isolated from EiaKO responded similarly to known activators and inhibitors of UCP1 activity, such as fatty acids and GDP (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 7d). The UCP1-dependent oxygen consumption rates were similar between WT and EiaKO mitochondria, while mitochondria from UCP1-negative tissues showed no response. These findings suggest that although UCP1 expressions and activity remain intact, the absence of Ei24 may have disrupted key aspects of the mitochondrial bioenergetic environments, such as ETC efficiency or the maintenance of the proton gradient, contributing to overall metabolic dysfunction.

To assess whether UCP1-independent thermogenic pathways are also affected in the absence of Ei24, we investigated SERCA-mediated calcium cycling and creatine substrate cycling—the two major ATP-dependent mechanisms that contribute to non-shivering thermogenesis.

During cold exposure or adrenergic stimulation, Ca²⁺ is released from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and actively pumped back by SERCA2b in an ATP-dependent manner39. This continuous cycling of Ca²⁺ creates a futile cycle, which dissipates energy in the form of heat and contributes to non-shivering thermogenesis. Upon pharmacological stimulation of SERCA with CDN1163, wild-type brown adipocytes displayed a robust increase in ER calcium levels, whereas EiaKO cells showed a significantly blunted response (Fig. 5j). This suggests that reduced ATP-dependent calcium uptake or compromised SERCA function in Ei24-deficient cells potentially linked to mitochondrial ATP synthesis.

We also analyzed gene expression profiles associated with creatine cycling. Notably, creatine kinase B-type (CKB)—a key cytosolic creatine kinase—was strongly induced by cold exposure in wild-type BAT but failed to respond in EiaKO BAT, despite comparable basal levels (Fig. 5k). Other creatine-related genes (CKM, CKMT1, CKMT2) showed similar or minimal changes. This impaired transcriptional activation of CKB further supports defective engagement of creatine-based thermogenesis under cold stress in Ei24-deficient adipose tissue attributing to lethal hypothermia.

To explore whether Ei24’s role in mitochondrial function extended beyond brown adipocytes, we conducted ATP synthesis assays using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from Ei24 conditional knockout (Ei24f/f) mice. This experiment was designed to assess whether the function of Ei24 in regulating mitochondrial ATP production is conserved across distinct cell types. The results demonstrated a significant impairment in ATP production in EiaKO MEFs compared to controls (Fig. 5l). This suggests that Ei24 plays a fundamental and broadly relevant role in mitochondrial activity, further underscoring its impact on cellular energy metabolism across different lineages.

Hypothermic defects were reproducible in EibKO mice

To eliminate the potential paracrine effects of WAT lacking Ei24 on BAT functionality, we generated Ei24 BAT-specific knockout mice (EibKO) by crossbreeding EicKO mice with UCP1-Cre expressing mice. Efficient genetic ablation was confirmed via WB analysis (Fig. 6a). Both male and female EibKO mice displayed larger BAT sizes and areas than EiaKO mice (Fig. 6b). Morphological analysis using H & E staining revealed that EibKO mice exhibited increased BAT LD sizes without any observable changes in iWAT (Fig. 6c). Notably, during cold exposure, EibKO mice showed a marked reduction in body temperature, resembling the phenotype of EiaKO mice, indicating that the thermogenic and morphological changes in the BAT of EiaKO mice were BAT-specific (Fig. 6d, e). These findings suggested that intrinsic BAT dysfunction is independent of paracrine signaling in WAT.

a Western blot analysis of protein lysates obtained from BAT of male wild-type control and EibKO mice (representative results reproduced independently at least twice). b Images of interscapular BAT (left panel) isolated from male and female wild-type control and EibKO mice, and the calculated cross-sectional areas (right panel) based on the images shown in left panel (n = 6 biological replicates per group). c H & E staining (right panel) and LD size analysis (left panel) of iBAT and inguinal WAT from male wild-type and EibKO mice (n = 3 biological replicates per group; 2000 LDs for BAT, 90 for iWAT; Scale bars, 20 μm). d Core body temperatures of wild-type control and EibKO mice were measured at 25 °C and in a 4 °C environment. e Thermal images (left panel) and average surface temperature (right panel) of wild-type control and EibKO mice were measured at 25 °C and in a 4 °C environment. f Cellular ATP concentrations were measured in differentiated BAT SVFs from wild-type, EiaKO, and EiaKO-Ei24 re-expressed (RE) cells. g Mitochondrial matrix pH was measured in differentiated BAT SVFs from wild-type, EiaKO and EiaKO-RE mice (left panel). The resting mitochondrial matrix pH was quantified in differentiated BAT SVFs from wild-type, EiaKO, and EiaKO-RE mice (right panel). h Relative mitochondrial potentials (ΔΨm) were measured based on the ratio of tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) fluorescence to MitoTracker Green (MTG) fluorescence. Data in f, g are representative of 3 independent biological replicates. i Schematic summary of the effects of Ei24 deficiency in brown adipocytes. EiaKO BAT displayed enlarged lipid droplets and mitochondrial defects characterized by reduced membrane potential (ΔΨm), lowered mitochondrial matrix pH, and impaired fatty acid oxidation (FAO), leading to cold intolerance. Despite these defects, UCP1 expression and its activity remained comparable to controls. Created with Biorender.com56. The data shown represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for the data shown in a-c, one-way ANOVA in d, g and h, and two-way ANOVA for the data shown in e, f.

To further confirm the role of Ei24 in controlling the mitochondrial PMF and ATP synthesis, Ei24 was transiently expressed in differentiated EiaKO cells with an adenoviral vector. The re-expression of Ei24 in Ei24-depleted cells (EiaKO-RE) restored the ATP concentration to levels comparable to those in wild-type cells (Fig. 6f). Similarly, Ei24 re-expression completely rescued mitochondrial pH and ΔΨm (Fig. 6g, h and Supplementary Fig. 7e). These results firmly establish the essential role of Ei24 in maintaining mitochondrial function and bioenergetics in brown adipocytes.

Discussion

We found that Ei24 plays a previously uncharacterized role in BAT thermogenesis, extending beyond its established contribution to autophagy. Using adipocyte-specific (EiaKO) and brown adipocyte-specific (EibKO) Ei24 depletion, we demonstrated that Ei24 plays a key role in maintaining mitochondrial health supporting ATP synthase activity. This interaction was necessary for sustaining the ΔΨm and matrix pH, which is pivotal for efficient ATP synthesis and consequently, energy homeostasis.

Ei24 depletion in BAT led to significant mitochondrial dysfunction, including disruption of cristae architecture and the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria. This impairment was not solely due to hindered autophagy or mitophagy, and it underscored Ei24’s direct involvement in regulating mitochondrial integrity and ATP synthase function. Moreover, the absence of Ei24 diminished FAO and led to the formation of abnormally enlarged LDs in EiaKO mice. Consequently, the thermogenic capacity of EiaKO and EibKO mice was severely impaired, culminating in lethal hypothermia in EiaKO mice under cold stress. These findings highlight the important role of Ei24 in adaptive thermogenesis.

Notably, despite comparable UCP1 expression levels and activity between WT and Ei24 deficient mice, the observed thermogenic impairment in EiaKO and EibKO mice was not attributable to intrinsic UCP1 dysfunction. Instead, it likely stemmed from disruptions in the mitochondrial bioenergetic landscape, including ETC activity and proton gradient maintenance, which are critical for efficient UCP1-mediated heat generation.

Although UCP1-mediated thermogenesis is classically considered ATP-independent, our findings reveal Ei24 is essential for maintaining functional integrity of mitochondria necessitating mitochondrial ATP production and thus ATP dependent thermogenesis. In Ei24-deficient adipocytes, reduced ATP levels were closely accompanied by cristae collapse, membrane depolarization, and decreased substrate oxidation. These structural and functional abnormalities likely impair thermogenic output, even in the presence of comparable UCP1 expressions.

In search of Ei24-dependent thermogenesis mechanism, our findings demonstrate that Ei24 deletion disrupts two well-characterized ATP-dependent, UCP1-independent thermogenic pathways: SERCA-mediated calcium cycling and creatine substrate cycling39,40. Specifically, Ei24-deficient adipocytes showed attenuated ER calcium refilling upon CDN1163 stimulation, suggesting compromised SERCA activity. This defect is likely attributable to mitochondrial ATP depletion but may also reflect a more direct regulatory role, as previous studies have reported physical interactions between Ei24 and SERCA2 (ATP2A2)25. Similarly, we observed a reduced CKB mRNA expression in EiaKO BAT, implying impaired creatine cycling, that may contribute to the hypothermic phenotype observed in both EiaKO and EibKO mice.

These defects may stem not only from ATP deficiency but also from disrupted ER-mitochondrial calcium dynamics. Indeed, recent studies support such a role for Ei24 in inter-organelle communication. For example, Yuan et al. demonstrated that the C-terminal of Ei24 is critical for maintaining MAM integrity by stabilizing the VDAC1–GRP75–IP3R complex, which is essential for autophagy flux (Cell Mol Life Sci., 2020)34. Additionally, Xu et al. further showed that Ei24 preserves ER calcium retention and modulates unfolded protein response via IRE1, implicating it in ER calcium homeostasis (EMBO Rep, 2022)37. Although we did not directly assess MAM structure or Ca²⁺ flux between compartments, our SERCA-related findings suggest that Ei24 contributes to calcium homeostasis at multiple levels.

Taken together, these data suggest that Ei24 coordinates multiple layers of thermogenic regulation by maintaining mitochondrial ATP synthesis, supporting ATP-consuming futile cycles, and potentially stabilizing ER–mitochondrial Ca²⁺ signaling. This integrated function may underline the failure of Ei24-deficient BAT to sustain thermogenesis despite intact UCP1 expression.

Recent findings have highlighted the role of autophagy in cellular response to thermogenic demands41,42,43,44; in particular, the transition from white to beige adipocytes necessitates the suppression of mitochondrial autophagy to preserve the mitochondria. Our findings suggested that the observed increase in iWAT mitochondria and the brown-like appearance likely resulted from autophagy inhibition due to knocking out of Ei24, which we termed “fake-browning”. Despite these changes, the primary function of WAT as a lipid storage site was unaffected. This conclusion was supported by the stable weight of iWAT and the unchanged LD size, indicating that the essential lipid-storing functionality of WAT was maintained, even with these substantial mitochondrial and morphological changes.

Our results show functions of Ei24 in ATP synthesis and thermogenesis, highlighting areas for further investigation. Although we established that the Ei24–ATP synthase complex interaction was strengthened under conditions that demand increased thermogenesis and mitochondrial respiration, the specific interaction sites within the ATP synthase complex and the exact mechanisms whereby Ei24 affects within ATP synthase activity remain to be determined. Nonetheless, our domain mapping analysis revealed that the C-terminal region of Ei24 (amino acids 293–340) is both necessary and sufficient to partially restore ATP levels in Ei24-deficient brown adipocytes, suggesting this region plays a crucial role in modulating ATP synthase function. Moreover, the enhanced interactions between Ei24 and ATP synthase in response to thermogenic stimuli suggest that Ei24 plays a complex regulatory role in mitochondrial energy metabolism. However, the mechanism by which Ei24 translocated into mitochondria under these conditions requires further investigation. Future studies on how Ei24 physically contributes to the modulation of ATP synthase may provide critical insights into the regulation of mitochondrial efficiency.

Interestingly, glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity were unaltered in the EiaKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), which may further reflect the relatively minor contribution of BAT to whole-body glucose homeostasis under basal conditions. Furthermore, under standard housing conditions, the lifespans of both male and female EiaKO mice were comparable to those of wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). This suggested that while mitochondrial defects were evident in EiaKO BAT even under naïve conditions, the absence external stimuli did not impose a significant physiological burden that could affect overall survival.

Beyond BAT, our findings indicate that Ei24 plays a role in ATP production in MEFs, raising the possibility that Ei24 may also be functionally critical in cells with high mitochondrial such as myocytes and neuronal cells45,46. Given the essential roles of mitochondria in cognitive functions and physical performance, any perturbations in Ei24 expression within these tissues may lead to substantial impairments, even in the absence of external stressors.

In summary, we showed that Ei24 plays a significant role in BAT thermogenesis by maintaining mitochondrial integrity and supporting ATP synthase activity. This function is essential for optimizing energy utilization and sustaining thermogenic responses under stress, independent of UCP1 expression or activity (Fig. 6i). Mechanistically, we found that the C-terminal domain of Ei24 is critical for restoring mitochondrial ATP synthesis, further underscoring its functional relevance in energy metabolism. Additionally, Ei24 deficiency disrupted multiple ATP-dependent UCP1-independent thermogenic pathways, including SERCA-mediated calcium cycling and creatine substrate cycling, highlighting Ei24’s broad role in coordinating futile cycles. These findings suggest that Ei24 functions as a multifaceted regulator of mitochondrial bioenergetics, beyond its previously characterized roles in autophagy and mitophagy, and underscore its importance in sustaining thermogenesis under physiologically demanding conditions.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yonsei University (approval number IACUC-202011-1170-01). Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Korean Food and Drug Administration and the IACUC. Mice were maintained in the specific pathogen-free facility of the Yonsei Laboratory Animal Research Center and housed at 22–24 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. The animals had ad libitum access to water and food. Food was withdrawn only when required during the defined fasting periods. Unless otherwise stated, all experiments were performed on male mice. Mice were sacrificed at 6–16 weeks of age for related experiments. For cold-stress testing, the mice were individually housed without bedding in a 4 °C cold chamber, while maintaining the light/dark cycle. Their core body and surface temperatures were measured using either rectal thermometry or a thermal imaging camera (FLIR-T530). All mice subjected to the cold-tolerance testing were fasted for 6 h beforehand to ensure metabolic alignment, following previously established protocols47,48,49. Mice undergoing hypothermia were euthanized using CO2 when their core body temperature dropped below 30 °C.

To evaluate the effects of CL316,243 (Sigma-Aldrich) on experimental mice, the compound was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight. The mice were monitored for 1 h post-injection. The control group received an equivalent volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to ensure consistency in handling and injection procedures. For protein or mRNA analysis, mice were euthanized using CO2, and tissues were harvested and stored at -80 °C until use.

Generation of EiaKO and EibKO mice

EicKO mice containing two loxP sites (between exons 2–3 and 10–11 regions of the Ei24 gene) were generated using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. EicKO mice were crossbred with transgenic mice expressing adiponectin- or UCP1-specific Cre to generate EiaKO (Ei24f/f AdipoqCre) and EibKO (Ei24f/f UCP1Cre) mice, respectively. Littermate-control Ei24-floxed mice (wild-type) were used throughout the study. Genomic DNA was extracted from the tail tips of the mice and used to determine their genotypes.

Metabolic parameter measurement

Respiratory exchange ratio (RER) and energy expenditure (EE) were obtained with open-circuit Oxymax/CLAMS (Columbus Instruments Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring system). After 1 day of acclimation, oxygen consumption (VO2, ml/kg/hr) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2, ml/kg/hr) of individual mice were measured every 10 min for 3 consecutive days. The RER was calculated as VCO₂/VO₂, and EE (kcal/hour) was determined using the equation EE = 3.815 × VO₂ + 1.232 × VCO₂.

Glucose- and insulin-tolerance test

Mice were fasted for 6 hours prior to testing. After fasting, body weight was recorded to calculate the required dosage of glucose or insulin for injection. For GTT, mice received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of D-glucose (20% stock solution) at a volume of 10 µL per gram of body weight. For ITT, mice received an i.p. injection of insulin (0.25 U/mL in saline) at a volume of 3 µL per gram of body weight. Blood glucose levels were measured from tail vein blood at baseline (0 min) and 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes post-injection.

Histological and TEM analyses

H & E staining was conducted for histological analysis on 4 µm-thick paraffin sections. For TEM analysis, tissues were minced (1 mm3 in size), fixed for 12 h in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde, washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, post-fixed with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 2 h, and dehydrated using an ascending ethanol series (50, 60 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100%) for 10 min each. The specimens were embedded using a Poly/Bed 812 kit (Polysciences) and polymerized in an electron microscope oven (TD-700, DOSAKA, Japan) at 65 °C for 12 h. Each block was sectioned using a diamond knife in an ultramicrotome, cut into 200 nm semi-thin sections, and stained with toluidine blue for observation. Regions of interest were then cut into 80 nm-thin sections and placed on copper grids, double-stained with 3% uranyl acetate for 30 min and then 3% lead citrate for 7 min, and imaged using a TEM (JEM-1011, JEOL, Japan) at an acceleration voltage 80 kV that was equipped with a Megaview III CCD camera (Soft Imaging System, Germany).

Primary cell isolation

The procedures used to isolate and differentiate SVFs from brown and white adipose tissues were adapted from a previously published method50. Briefly, tissues were obtained from 6–8-week-old mice and digested with collagenase buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.9 g/L d-(+) glucose, 1.5% BSA, and 0.1% type-I collagenase) with stable agitation at 150 x g for 30–60 min at 37 °C. Digestion was stopped by adding PBS and the cells were filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, the SVFs were washed again with PBS. ACK lysis buffer (Gibco) was then added, and the SVFs were incubated for 5 min at room temperature to remove the blood cells, followed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g/L glucose (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) and seeded in a 100 mm cell-culture dish. After 5 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and the medium was replaced with fresh medium. EicKO MEFs were obtained from 13.5-day-old Ei24f/f mouse embryos. The MEFs were prepared and cultured as described previously in ref. 51.

Cell culture and adipocyte differentiation

Primary adipocytes (SVFs) were cultured at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in DMEM containing 4.5 g/L glucose (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). After the primary adipocytes reached confluence, they were incubated for an additional 2 days. Differentiation was induced by adding a differentiation cocktail containing 1 μg/mL insulin (#I9278, Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μM rosiglitazone (#R2408, Sigma-Aldrich), 1 nM 3,3’,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (T3; #T2877, Sigma-Aldrich), 2 μM dexamethasone (#D4902, Sigma-Aldrich), and 520 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methaxine (#I5879, Sigma-Aldrich). Terminally differentiated adipocytes were retained in 10% FBS supplemented DMEM.

Adenoviral plasmid design and transduction

The pAd/CMV/V5-Ei24 and pAd/CMV/V5-DEST plasmids were generated using the Gateway cloning system (Thermo Fisher). The plasmids were digested with PacI and purified via phenol–chloroform extraction. Briefly, an equal volume of a phenol: chloroform: isoamyl alcohol solution (#P2069; Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed with the nucleic acid solution and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and precipitated with an equal amount of isopropanol at -60 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min, the resulting pellet containing the purified plasmid DNA was washed using 70% ethanol and air-dried for 5 min.

Purified plasmids were transfected into HEK293A cells (1 × 106 cells in a 6-well plate) using Lipofectamine 2000 to produce adenoviruses capable of expressing Ei24 (AdEi24) and adenovirus DEST (AdDEST). At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were transferred to a sterile 10 cm tissue culture plate. After approximately 80% cytopathic effects were visible (10–13 days post-transfection), the adenovirus-containing cells and medium were harvested and subjected to two freeze–thaw cycles. Crude virus was obtained by centrifuging the cell lysate at 3000 x g for 15 min at room temperature to remove the cellular debris. The viruses were propagated in HEK293A cells and purified via CsCl gradient centrifugation52. Viral particle titers were determined by measuring the optical densities of the samples at 260 and 280 nm using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer.

For viral transduction, cells were infected with AdEi24 at a multiplicity of infection of 20,000 viral particles/cell. After 8 h of incubation at 37 °C, the virus-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh culture medium. Control experiments involved uninfected cells and cells infected with AdDEST.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells and tissues were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (4693116001, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (4906845001, Roche). Protein lysates were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane were blocked in 5% skim milk in TBST for 1 h at RT and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution). Primary antibodies against Ei24 (#42328, Cell Signaling Technology), VINCULIN (sc-73614, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), UCP1 (ab10983, Abcam), LC3 (L8918, Sigma-Aldrich; #4108, Cell Signaling Technology), p62 (H00008878-M01, Abnova), GAPDH (sc-47724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HSP90 (sc-13119, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ATGL (2138S, Cell Signaling Technology), p-HSL (#4137, 4139, and 45804, Cell Signaling Technology) HSL (#4107, Cell Signaling Technology), FABP4 (#3544 T, Cell Signaling Technology), CPT1A (#12252S, Cell Signaling Technology), PPARγ (sc-7273, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PLIN1 (#9349, Cell Signaling Technology), ACC1 (#3676, Cell Signaling Technology), FASN (#3180, Cell Signaling Technology), β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PGC1α, (ab191838, Abcam; #MA5-32563, Thermo Fisher), PRDM16 (pa5-20872, Invitrogen), VDAC (#4661, Cell Signaling Technology; #529536, Calbiochem), p62 (t#5114S, Cell Signaling Technology), vimentin (#5741, Cell Signaling Technology), α-tubulin (sc-5286, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), OXPHOS cocktail (#110413, Abcam), ATP5B (sc-166443, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cytochrome-c (sc-13156, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-AMPK (sc-101630, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and AMPK (sc-74461, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. A rabbit monoclonal anti-TFAM antibody was provided by Professor Chan Bae Park (Department of Physiology, Ajou University School of Medicine). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (#A16066, Invitrogen) and anti-rabbit IgG (#G21234, Innovative Research, Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies at 1:5000 dilution. Protein bands were captured using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad).

RNA extraction and qPCR analysis

Total RNA from homogenized tissue samples or cells was harvested using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (#K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time qPCR was conducted on a CFX ConnectTM real-time system (Bio-Rad) using the SYBR Green real-time PCR master mix (Life Technologies). Gene expression analysis was performed using the 2–ΔΔCt method, using 18S RDNA or Actb as internal reference genes. Primer sequences for mRNA expression and mtDNA quantification are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Mitochondrial Isolation

Crude mitochondria were isolated from brown adipose tissue (BAT) of wild-type (WT) and EiaKO mice by differential centrifugation53. Freshly dissected BAT was finely minced and homogenized in ice-cold Isolation Buffer 1 (225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 0.1 mM EGTA) using a Teflon pestle and glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. The supernatant was collected, centrifuged again at 600 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was subjected to a final centrifugation at 7000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The mitochondrial pellet was washed twice by resuspending in ice-cold IBliver-2 buffer (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and centrifuging at 7,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Mitochondrial protein concentration was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Immunocytochemistry

Following CL316,243 treatment, cells were incubated with Mitotracker Red for 10 minutes at room temperature, then washed twice with ice-cold PBS. Cells were fixed with 100% ice-cold methanol for 15 min at –20 °C, followed by permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. After permeabilization, cells were blocked in 5% BSA in PBST for 1 hour, then incubated with anti-Ei24 antibody (#42328, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (#A-11008, Invitrogen) for 1 h, followed by DAPI counterstaining for 5 minutes at room temperature. Images were acquired using an LSM900 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Manders’ overlap coefficient was calculated using the JACoP plugin in ImageJ.

OCR and ECAR measurements

The OCR was measured using an extracellular flux analyzer XF-96 (Seahorse Bioscience). Primary adipocytes were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in Seahorse 96-well plates coated with collagen I (#A1048301, Thermo Fisher Scientific) the day before the experiment. Cells were incubated with XF DMEM (pH 7.4; #103575-100, Seahorse Bioscience) supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, and 17.5 mM glucose 1 h before taking OCR measurements. The effects of oligomycin (2 μM), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM) (XF-Cell Mito stress test kit, Seahorse Bioscience) on the OCR were measured right after the injection of these compounds in the cells.

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of isolated mitochondria was measured using a Seahorse XF96 Analyzer (Agilent) at 37 °C. Mitochondria (3 µg) were seeded into each well of a Seahorse XF96 cell culture microplate containing 150 µL of Adipocyte Respiration Buffer (125 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 2 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM KH₂PO₄, 5 mM malate, 5 mM pyruvate, and 4% fatty-acid-free BSA). The plate was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to facilitate attachment of mitochondria to the well bottom.

For the UCP1 activity assay, 100 µM palmitate was injected to activate UCP1-mediated proton conductance, followed by 5 mM guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to inhibit UCP1 activity. Baseline OCR, OCR after palmitate injection, and OCR after GDP injection were recorded. The difference in OCR before and after GDP treatment was used as a readout of UCP1-dependent respiration.

For ECAR measurements, cells were incubated with XF DMEM (pH 7.4) (#103575-100) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine for 1 h before the assay. Optimal concentrations of glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (2 μM), and 2-DG (50 mM) (XF-glycolysis stress test kit, Seahorse Bioscience) were added to the medium for ECAR measurements.

For FAO measurements, cells were incubated overnight at 37 °C with substrate-limited medium containing seahorse XF DMEM base medium (pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM l-carnitine, 1.0 mM glutamine, and 1% FBS. The medium was exchanged with FAO assay buffer (4.7 mM KCl, 111 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM l-carnitine, and 50 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C without CO2 before taking the OCR measurements. In separate experiments, the cells were pre-treated with etomoxir (40 μM) for 15 min before adding palmitate-BSA or BSA as a control.

ΔΨm measurements

ΔΨm values were measured using JC-1 or TMRM. When measuring ΔΨm values using JC-1, cells were seeded in 96-well black polystyrene microplates the day before the experiment. The cells were incubated with 500 nM JC-1 in Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate buffer (140 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 2 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES; pH = 7.4) for 30 min and then washed twice. Fluorescence signals were recorded using a fluorescence microplate reader (FlexStation II; Molecular Devices). The ΔΨm was estimated based on the ratio of red fluorescence (aggregates: excitation at 540 nm, emission at 590 nm) to green fluorescence (monomers: excitation at 490 nm, emission at 535 nm).

When measuring ΔΨm using TMRM, cells on coverslips were co-stained with 50 nM TMRM and 100 nM MTG in the culture medium. After a 30 min incubation in the dark at 37 °C, TMRM and MTG solutions were removed and replaced with fresh culture medium for fluorescence measurements. Live-cell imaging was performed at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 using an LSM900 microscope (Carl Zeiss). The raw integrated density values of the TMRM and MTG fluorescence signals were quantified on a per cell basis using the Zen 3.2 software. Mitochondrial ΔΨm values were expressed as the TMRM: MTG fluorescence ratio.

Mitochondrial pH measurements

Mitochondrial matrix pH was measured using pH-sensitive fluorophore SNARF-1 AM acetate (C1272, Thermo Fisher Scientific)54. The cells were cultured in collagen-coated confocal dishes (SPL Life Science, South Korea) placed in a live-cell chamber (containing 5% CO2) for imaging. The cells were incubated in medium containing 5 μM SNARF-1 AM for 30 min at 4 °C. The medium was then discarded, and the cells were washed twice with Krebs–Henseleit buffer (138 mM NaCl, 3.7 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose; pH 7.4). The pHmito values were calibrated using solutions with pH varying from 7.0 to 9.0 (140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 11 mM dextrose, 2 mM EGTA, 12 mM HEPES, 10 μM nigericin). SNARF-1 AM fluorescence was measured at 580 and 640 nm. The cells were perfused with 500 nM NH4Cl and 300 μM FCCP, and images were acquired every 15 s. Confocal images were acquired using an LSM900 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Mitochondrial pH was calculated based on the 640: 580 nm fluorescence ratio according to a calibration curve.

Triacylglycerol and glycerol measurements

The in vitro lipolytic and lipogenic rate were accessed by measuring cellular triacylglycerol and glycerol concentration. Measurements were conducted using Glycerol-GloTM assay kit (J3150, Promega). For evaluation of lipogenic rate, terminally differentiated adipocytes were incubated in serum and glucose-free medium for 4 hours prior to the assay and 1 μg/ml human insulin (#I9278, Sigma-Aldrich) was then added in the media. For the lipolytic rate assay, cells were treated with 10 μM Isoproterenol (I5627, Sigma). Next, the lysis of cells was conducted per the manufacturer’s guidelines, and then substrates and enzymes were added. Glycerol and triacylglycerol levels were measured using luciferase activity and normalized by the included glycerol standard. Free glycerol concentration was calculated using the amount of total glycerol and triacylglycerol.

Cellular ATP measurements

ATP levels were determined using the ATP bioluminescence assay kit HS II (Roche) and the ATP/ADP ratio kit (#MAK135; Sigma Aldrich). For viral Ei24 re-expression, differentiated SVFs from BAT were infected with either a control adenovirus or an adenovirus expressing Ei24 to reintroduce Ei24 expression two days prior to the assay. Cells were treated with oligomycin (5 µM) and 2-DG (50 mM) for 6 h before the assay to inhibit mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis, respectively. Cell lysis was performed using the cell lysis buffer provided in the kit. Luciferase was added to the cells, and signal integration was performed immediately after injection. Relative luminescence unit (RLU) values were normalized to measured protein concentrations in equally seeded, cultured and differentiated samples. Three biologically independent samples were utilized for each data.

ER calcium measurement

To assess ER Ca²⁺ dynamics, G-CEPIA1er (Addgene plasmid #105012) was transfected into brown adipocytes differentiated from SVF cells isolated from wild-type and EiaKO mice. Transfection was performed 48 h prior to imaging. On the day of the experiment, cells were washed three times with Krebs–Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) buffer containing 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5.5 mM glucose. Imaging was conducted under continuous perfusion with Ca²⁺-free KRB containing CDN1163 (5 µM) to evaluate SERCA-mediated Ca²⁺ uptake. Cells were imaged using Olympus IX-73 inverted microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera and LED illuminator. G-CEPIA1er was excited at 460 ± 15 nm, and emission was collected at 535 ± 20 nm. Images were captured and analyzed using MetaFluor 3.1 software (Molecular Devices).

Gene set enrichment analysis

Publicly available microarray data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and analyzed to investigate pathway enrichment associated with altered gene expression. For GSE44095, which profiles adipocytes from wild-type chow-fed mice, phenotype and expression matrices were extracted, and samples were stratified based on Ei24 expression (using quartile-based grouping). Probe IDs were mapped to official gene symbols using the corresponding platform annotation, and differential expression analysis was performed using the limma package in RStudio. Significantly differentially expressed genes were then subjected to pathway enrichment analyses—including KEGG, and Hallmark gene set analyses via clusterProfiler and msigdbr—to identify key metabolic and adipogenic processes. In parallel, three additional cancer datasets (Breast Cancer, GSE3744; Hepatocellular Carcinoma, GSE62043; and Melanoma, GSE3189) were analyzed using GSEA software55 to determine gene set enrichment profiles.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. All the replicate experiments were repeated at least three times. Graphs and statistical comparisons were made by performing unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, multiple comparisons by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and two-way ANOVA using the GraphPad Prism 8 software. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using publicly available datasets, under accession codes GSE44095, GSE3744, GSE62043, and GSE3189. Source data are provided with this paper. Figure 6i was created with BioRender. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cannon, B. & Nedergaard, J. The biochemistry of an inefficient tissue: brown adipose tissue. Essays Biochem 20, 110–164 (1985).

Jacobsson, A., Stadler, U., Glotzer, M. A. & Kozak, L. P. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein from mouse brown fat. Molecular cloning, genetic mapping, and mRNA expression. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 16250–16254 (1985).

Ricquier, D. & Bouillaud, F. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins: from mitochondria to the regulation of energy balance. J. Physiol. 529, 3–10 (2000).

Cannon, B. & Nedergaard, J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277–359 (2004).

Feldmann, H. M., Golozoubova, V., Cannon, B. & Nedergaard, J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 9, 203–209 (2009).

Bastias-Perez, M. et al. Impact of Adaptive Thermogenesis in Mice on the Treatment of Obesity. Cells 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020316 (2020).

Lowell, B. B. & Spiegelman, B. M. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 404, 652–660 (2000).

Park, A., Kim, W. K. & Bae, K. H. Distinction of white, beige and brown adipocytes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 6, 33–42 (2014).

Enerback, S. The origins of brown adipose tissue. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 2021–2023 (2009).

Kozak, L. P. & Anunciado-Koza, R. UCP1: its involvement and utility in obesity. Int J. Obes. (Lond.) 32, S32–S38 (2008).

Fedorenko, A., Lishko, P. V. & Kirichok, Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell 151, 400–413 (2012).

Nicholls, D. G. & Rial, E. A history of the first uncoupling protein, UCP1. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 31, 399–406 (1999).

Fromme, T. et al. Degradation of brown adipocyte purine nucleotides regulates uncoupling protein 1 activity. Mol. Metab. 8, 77–85 (2018).

Bast-Habersbrunner, A. & Fromme, T. Purine Nucleotides in the Regulation of Brown Adipose Tissue Activity. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 118 (2020).

Yoneshiro, T. et al. Brown adipose tissue, whole-body energy expenditure, and thermogenesis in healthy adult men. Obes. (Silver Spring) 19, 13–16 (2011).

Poher, A. L., Altirriba, J., Veyrat-Durebex, C. & Rohner-Jeanrenaud, F. Brown adipose tissue activity as a target for the treatment of obesity/insulin resistance. Front Physiol. 6, 4 (2015).

Chouchani, E. T., Kazak, L. & Spiegelman, B. M. New Advances in Adaptive Thermogenesis: UCP1 and Beyond. Cell Metab. 29, 27–37 (2019).

Gu, Z., Flemington, C., Chittenden, T. & Zambetti, G. P. ei24, a p53 response gene involved in growth suppression and apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 233–241 (2000).

Zhao, X. et al. Apoptosis factor EI24/PIG8 is a novel endoplasmic reticulum-localized Bcl-2-binding protein which is associated with suppression of breast cancer invasiveness. Cancer Res 65, 2125–2129 (2005).

Choi, J. M., Devkota, S., Sung, Y. H. & Lee, H. W. EI24 regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tumor progression by suppressing TRAF2-mediated NF-kappaB activity. Oncotarget 4, 2383–2396 (2013).

Nam, T. W., Park, S. Y., Lee, J. H., Roh, J. I. & Lee, H. W. Effect of EI24 expression on the tumorigenesis of Apc(Min/+) colorectal cancer mouse model. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 514, 1087–1092 (2019).

Tian, Y. et al. C. elegans screen identifies autophagy genes specific to multicellular organisms. Cell 141, 1042–1055 (2010).