Abstract

Small mammals harbor a diverse array of potentially zoonotic pathogens. To date, however, metagenomic surveys of these species have primarily focused on viruses, with limited attention directed to bacterial and eukaryotic pathogens. Additionally, the ecological determinants of pathogen diversity within these mammals have not been systematically examined. Herein, we employed a metatranscriptomics approach to survey the pathogen infectome—defined as the set of microorganisms infecting the host—across 2408 individual samples, representing lung, spleen, and gut from 858 animals in Guangdong province, China, considering the impact of host species, tissue, season, and geographic location on pathogen diversity. We identified 76 potential pathogen species, comprising 29 RNA viruses, 12 DNA viruses, five bacteria, and 30 eukaryotic pathogens, including 33 that are newly discovered. Distinct tissue tropisms were identified, suggesting varied transmission routes. Individual animals carried an average of one pathogen, with 10 pathogens widely distributed among mammalian orders. Total pathogen richness was largely influenced by geographic region, followed by host species and season, while zoonotic pathogen richness was primarily driven by host species. Collectively, these data provide insights into the structure of the pathogen infectome and the drivers of pathogen diversity and transmission in these key mammalian disease reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small mammals, including rodents (order Rodentia) and shrews (order Eulipotyphla), are major reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens that pose significant risks to human health. These pathogens include hemorrhagic fever viruses (such as arenaviruses and hantaviruses), that can have a mortality rate of up to 81%1; plague and fever-causing bacteria (e.g., Yersinia pestis, Rickettsia, and Leptospira), which can lead to serious disease but are only sporadically detected in China2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9; and various endoparasites (e.g., Toxoplasma), that can infect humans but depend on rodents for part of their life cycle10. Beyond the pathogens they carry, the public health risk posed by small mammals is amplified by their close contact with humans11,12,13,14. Indeed, despite significant improvements in hygiene and sanitation over the past two decades, pathogens associated with small mammals can be transmitted through direct animal contact, via their excretions, contaminated water and food, or through blood-sucking fleas and ticks3,9,15,16,17,18.

As small mammals can serve as reservoirs for important pathogens and sometimes closely interact with humans, modern pathogen discovery has increasingly focused on these animals. The goal of these studies is to identify the diversity of potential pathogens, although most have concentrated on viruses. Earlier studies using PCR assays with primers designed from conserved regions of viral genomes led to the discovery of numerous new rodent- and shrew-associated viruses within all major families of mammalian viruses, and which often formed host-associated virus clusters on phylogenetic trees19,20,21,22,23,24,25. The known diversity of viruses in these hosts was further expanded with the use of viral-particle enrichment metagenomics26,27,28 and meta-transcriptomics29,30,31,32. For example, 206 virus species were identified in a study of 3055 individuals from 50 rodent species, establishing the core virome of these mammals in China26. Similarly, a meta-transcriptomic survey of the shrew lung virome revealed more novel than known viruses33. Notably, some studies also discovered pathogens related to those that cause disease in humans, such as the Mojiang virus—a close relative of the Hendra and Nipah viruses discovered in an abandoned mine shaft26,34. Collectively, these studies provide a broad-scale investigation of the virome in rodents and shrews, expanding our understanding of viral diversity and identifying potential emerging human pathogens.

Large-scale sampling and sequencing has also greatly advanced studies of virus ecology and evolution32,35,36,37. These studies have compared viral diversity across regions and host species, revealing strong host-virus associations, with geographic factors playing a secondary role in shaping virus diversity26,33,38. Importantly, cross-species virus transmission has also been documented, commonly between different host species and less frequently among host families and orders39,40. Despite these findings, ecological comparisons have generally been conducted at a broad scale, often lacking study designs that account for host species, geographic location, temporal distribution, and adequate replication across variables. Moreover, many studies have relied on samples pooled from multiple individuals, sometimes mixing host species within a single sample, thereby complicating the analysis of cross-species virus transmission. Additionally, the focus on viral diversity has overshadowed investigations into the presence and abundance of other pathogen types, such as bacteria and eukaryotic pathogens, leaving major gaps in our understanding of their ecological roles and interactions.

Herein, we describe a large-scale survey of small mammals and their associated pathogens in Guangdong province in southern China. Guangdong is located in the subtropical climate zone and boasts high biodiversity. Historically, Guangdong has been an epicenter for the emergence of SARS and other infectious disease outbreaks of importance41. Additionally, as a major gateway for both domestic and international trade, Guangdong often plays a major role in the spread of infectious diseases. Our study comprises a broad geographic survey conducted in winter, as well as a year-long monthly survey in two cities, encompassing small mammal populations from both domestic and rural settings. We perform meta-transcriptomic sequencing on individual lung, spleen, and gut samples from single animals. With these data in hand, we systematically compare mammalian pathogens across all major microbial groups – RNA viruses, DNA viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotic pathogens—examining their distribution across different organs, host species, geographic locations, and seasons. The data generated provide valuable insights into pathogen diversity under varying conditions, and reveal key factors driving pathogen evolution and transmission.

Results

Large-scale sampling across space, time, hosts, and tissues

We conducted a systematic survey of small mammals and their associated pathogens (i.e., those microbes, including viruses, known or likely to be associated with disease) across Guangdong province, China (Fig. 1a). The survey comprised two parts: the first involved winter-season sampling across nine regions in Guangdong province to compare pathogen diversity among geographic locations, while the second comprised year-round sampling at two specific sites—Anpu and Zhanjiang, both located in southwestern Guangdong and home to regional plague monitoring centers—to assess the impact of seasonal variation (Table 1). In total, 858 individual animals were collected. Sampling was conducted at both agricultural and residential settings within each region. As such, the sampled animals are considered representative of the terrestrial small mammal populations with potential relevance to human exposure.

a Pie charts show the distribution of host species across sampling locations. The size of each pie chart reflects the sample size, and the colors represent the species composition. b Phylogenetic relationships of the species sampled (denoted by solid circles) and related mammalian species. c Distribution of host species by sampling location. d Seasonal distribution of host species in Anpu and Zhanjiang, Guangdong province, China.

Cox1 gene analysis identified nine species across six genera: Rattus, Bandicota, Berylmys, Mus, Niviventer, and Suncus, belonging to two mammalian orders—Rodentia and Eulipotyphla (Fig. 1b). R. norvegicus (Rattus norvegicus) was the most commonly sampled species (N = 240), followed by B. indica (Bandicota indica, N = 195), R. tanezumi (Rattus tanezumi, N = 151), S. murinus (Suncus murinus, N = 118), and R. losea (Rattus losea, N = 92). While species composition varied significantly among geographic locations, it remained relatively stable across different seasons (Fig. 1c, d, Table 1).

Microbes and pathogens revealed through meta-transcriptomics

We performed meta-transcriptomic sequencing of the lung, spleen, and gut tissues from all 858 individual animals to capture potential pathogens associated with respiratory, blood-borne, and gastrointestinal transmission routes. As each individual and tissue comprised a separate sequencing library, this resulted in the generation of 2408 sequencing libraries and 10.2 Tbp of total data. The median sequencing depth per library was 42.85 Gbp. From this data set, we identified over 217 species of eukaryotic viruses, spanning 13 viral RNA supergroups and four DNA viral families (Supplementary Fig. 1). Anelloviridae exhibited the highest detection rate (30.4%), while the greatest viral species richness was observed in the Partiti-Picobirna (n = 68) and Narna-Levi (n = 33) supergroups (Supplementary Fig. 2). For bacteria, Cutibacterium, Pseudomonas, and Cupriavidus were the most prevalent genera in the lung and spleen, whereas Helicobacter, Prevotella, and Bacteroides predominated in the gut (Supplementary Fig. 3).

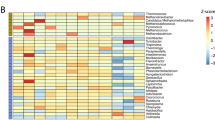

With respect to known and potential pathogens, we detected 80 species of potential mammalian RNA viruses, 20 potential mammalian DNA viruses, five pathogenic bacterial species, and 30 eukaryotic species associated with or closely related (> 95% nucleotide identity at marker genes) to fungal and parasitic pathogens. These pathogens spanned 15 viral, four bacterial, and 17 eukaryotic families. Viruses from the families Picobirnaviridae42,43 and Anelloviridae44,45 were excluded as potential pathogens due to unknown hosts or unspecific pathogenicity. Consequently, the pathogen infectome of the sampled mammalian species, based on the tissues analyzed here, comprised 76 microbial species: 29 RNA viruses, 12 DNA viruses, five bacteria, and 30 eukaryotic pathogens (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 1, 4–7 and Supplementary Data 1–3).

The heatmap (left panel) illustrates the distribution of pathogens across host species, sampling sites, seasons, and tissues, with color intensity indicating the positivity rate of each pathogen. The histogram (middle panel) shows the overall pathogen positivity rate, while the scatter plot (right panel) displays the level of pathogen abundance (i.e., positivity rate).

Newly identified pathogens and their positive rate landscape

Among the 41 potential mammalian viral pathogens discovered, 18 were newly identified species, with the remainder representing existing species (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). Most novel viral pathogens were identified from the RNA virus family Arteriviridae (N = 5) and the DNA virus family Parvoviridae (N = 6). Notably, a novel orbivirus, provisionally named Guangdong rodent orbivirus, was divergent from all known orbiviruses, forming a distinct sister lineage (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, that this virus was identified in lung and spleen at a high abundance (up to 723 RPM) suggests that it is likely to be a bona fide mammalian virus. Additionally, novel members of the bacterial genus Bartonella and eukaryotic genera such as Giardia, Spironucleus, Brachylaima, and Hepatozoon were identified and confirmed through analyses of marker genes, occupying distinct positions on phylogenetic trees (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 4).

Pathogen positivity was defined as the proportion of individuals testing positive in at least one of three tissues—lung, spleen, or gut—out of the total number of individuals in each group. Overall, no significant differences in positivity rates were observed among the four pathogen types, although eukaryotic and RNA viral pathogens exhibited significantly higher richness than bacterial and DNA viral pathogens (Supplementary Fig. 8). Among RNA viruses, Guangdong rodent arterivirus 1 had the highest positive rate (9.2%), followed by zoonotic pathogens like Rat hepatitis E virus (9.0%), Wenzhou mammarenavirus (8.7%), Betacoronavirus HKU24 (4.9%), and Seoul orthohantavirus (3.5%). For DNA viruses, parvoviruses—particularly Rat minute virus 2a—exceeded 20% positivity, while adenoviruses were less common (2.8%) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 4). Eukaryotic pathogens showed a high overall positivity (40.8%, 259/634), with Pneumocystis (10%) and Angiostrongylus cantonensis (7.6%) among the most common (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 4). Other notable parasites included Strongyloides, Nippostrongylus, Tritrichomonas, Trypanosoma, and Giardia. Zoonotic species such as Cryptosporidium ubiquitum and Babesia microti were also detected. In comparison, bacterial pathogens were less common, with Bartonella (6%) and Chlamydia (2.4%) being the most common (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 4).

Tissue tropism suggests multiple transmission pathways

The mammal-associated pathogens identified here were associated with distinct tissue tropisms and potential transmission signatures. The gut exhibited the highest overall pathogen diversity (Fig. 3a, b), particularly for RNA viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotic parasites, while the spleen showed the lowest (Fig. 3c). DNA viral diversity, however, was comparable between the gut and spleen. Despite this, pathogen abundance did not always mirror pathogen diversity. In particular, lungs harbored the highest burden of eukaryotic pathogens, highlighting the importance of respiratory tissues in parasitic infections (Fig. 3c).

a Bar graph showing the number of RNA viruses, DNA viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotes detected in the gut, spleen, and lung samples. b Venn diagram showing the overlap of pathogen species between tissues. c Comparisons of pathogen richness (top panel) and abundance (bottom panel) across three tissues. The comparisons were performed based on a Wilcoxon test, with the following symbols indicating statistical significance: not significant (ns), p > 0.05, * p <= 0.05, ** p <= 0.01, *** p <= 0.001, **** p<= 0.0001. d Comparisons of pathogen abundance across three tissues. e Tissue tropism of the 12 most abundant zoonotic pathogens. The lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles, whisker extends were calculated using 1.5 * IQR or 1.58 * IQR / sqrt(n) (a roughly 95% confidence interval for comparing medians).

Systemic infections were less common: only 25.6% of pathogens were found across all three tissues, with RNA viruses the most common shared agents (Fig. 3d). Most pathogens exhibited clear tissue preferences. Specifically, enteric viruses (e.g., Picornaviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae) dominated the gut, Parvoviridae and Bartonella were enriched in the spleen, and several zoonotic parasites (e.g., Pneumocystis, Angiostrongylus, Trypanosoma) were concentrated in the lungs (Fig. 3d).

These patterns suggest distinct transmission routes—respiratory, fecal–oral, and circulatory—are shaped by pathogen-specific tissue tropism, although further studies are needed to confirm these pathways. The tissue enrichment of most important zoonotic pathogens (Fig. 3e) further underscores the need to consider tissue when assessing transmission risks.

Frequent host switching in small mammals underscores the risk of pathogen spillover

We first assessed pathogen diversity, measured by species richness, in each individual animal. Accordingly, individual animals carried a median of one pathogen species (range: 0-12) across the three tissue types sampled (Fig. 4a). Notably, based on the detection threshold set in this study (i.e., RPM > 1 and additional criteria detailed in the “Methods” section), 30.3% of individual animals showed no detectable pathogens in the tissues sampled. Next, we investigated the factors shaping pathogen composition at the level of individual hosts. Among the variables tested, host phylogenetic relatedness had the strongest effect, accounting for 11.1% of the variation in shared microbial species across samples (Fig. 4b), while other factors had no significant impact. As expected, a significant negative correlation was observed between host genetic distance and the number of shared pathogens (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating that closely related hosts tend to harbor more similar pathogen communities.

a Number of pathogens carried by each individual host. The color bar at the bottom indicates the host species. b Relative contribution of host evolutionary distance, environmental factors and spatial distance to the number of pathogens shared between individuals. c Virus sharing network. Nodes represent hosts or virus species, colored by host species and cross-species transmission potential, and shaped according to pathogen type. Line thickness between nodes reflects the positivity rate in less prevalent hosts, with the network is divided into two subnets based on host order. External nodes highlight pathogens with the potential for cross-order transmission. d Number of pathogens shared among species, genera, families, and orders of different mammalian hosts. Four pathogen types are represented using distinct colors. e Cross-order transmission rates for four pathogen types (left panel) and results of a two-sided Fisher’s exact test comparing pathogen types (right panel), with colors indicating p-values.

We further examined patterns of pathogen transmission across host species, genera, families, and orders. Cross-species transmission appeared to be the rule rather than the exception, with 65.8% of the pathogens detected showing the ability to cross host species barriers and 12.7% able to infect hosts from multiple mammalian orders (Fig. 4c, d). Notably, all the bacterial species identified were capable of infecting multiple host species, underscoring their broad host adaptability.

Pathogens detected in multiple host orders represent those with the broadest host ranges and, consequently, likely pose an elevated zoonotic risk. We identified 10 such cross-order pathogens, comprising two RNA viruses, three DNA viruses, two bacterial species, and three eukaryotic pathogens (Fig. 4c). Notably, eight of these cross-order pathogens were detected in more than two host species and exhibited consistently high positivity rates (Supplementary Fig. 10), highlighting their potential for widespread transmission. Statistical comparison using Fisher’s exact test revealed no significant differences among pathogen types at the species or genus levels, although rates of cross-order transmission were significantly higher for bacteria than for RNA viruses and eukaryotic pathogens (Fig. 4e).

Environmental and host factors shape pathogen dynamics and transmission trends

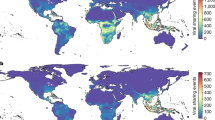

We next analyzed the biological and environmental factors that influence total pathogen richness (Fig. 5a). Geographic region explained the largest proportion of variation in pathogen richness (11.3%, Fig. 5b), followed by host species (6.7%, Fig. 5c), sampling season (6.4%, Fig. 5d), and environmental variables (3.2%), with 72.4% of variation remaining unexplained. Notably, samples from B. indica, along with the towns of Maoming, were associated with higher pathogen richness (Fig. 5c).

a Relative contribution of sampling location, host species, sampling season, and environmental factors to the richness of all pathogens in each individual animal, quantified by the explained deviance in the best model structures (ΔAIC < 2) using generalized linear models (GLMs). b–d Estimated effect size of sampling location (b), host species (c), and sampling season (d) on pathogen richness per individual, presented with estimated mean values and 95% confidence intervals (CI). e Relative contribution of sampling location, host species, sampling season, and environmental factors to the richness of known zoonotic pathogens in each individual animal, quantified by the explained deviance in the best model structures (ΔAIC < 2) using generalized linear models (GLMs). f–h Estimated effect size of sampling location (f), host species (g), and sampling season (h) on the richness of known zoonotic pathogens in each individual animal, presented with estimated mean values and 95% confidence intervals (CI). i Hotspots of human-related pathogens identified using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Variables analyzed include host species, habitat type, sampling region, and sampling time. P-values are indicated within each cell. * p-value < 0.05. ** p-value < 0.01.

We conducted a parallel analysis focusing specifically on known zoonotic pathogens (e.g., Seoul orthohantavirus, Bartonella kosoyi, Angiostrongylus cantonensis amongst others) to assess their immediate public health relevance. In contrast to total pathogen richness, zoonotic pathogen richness was primarily driven by host species (10.9%), with geographic region and season contributing less (2.8% and 0.6%, respectively) (Fig. 5e–h). Hotspot analysis revealed that Angiostrongylus cantonensis was more prevalent in B. indica, particularly in Jieyang and Heyuan, and during autumn (all p < 0.01) (Fig. 5i). Seoul orthohantavirus was most frequently detected in R. norvegicus (all p < 0.01) and during summer (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5i). To further resolve spatial patterns, we controlled for season and host species and compared pathogen positivity rates across locations (Supplementary Fig. 11). This confirmed regional differences and revealed species-specific geographic trends, such as Wenzhou mammarenavirus being more common in B. indica from Anpu (29.3%) and in R. norvegicus from Zhanjiang (30.8%).

Discussion

We conducted a large-scale surveillance of a broad spectrum of pathogens in small mammals, comprising RNA viruses, DNA viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Previous infectome studies have usually taken a smaller scale perspective. For instance, earlier studies have mapped the spectrum of pathogens in the human respiratory system46,47, highlighted shifts in opportunistic pathogens and commensal microbes in the respiratory tract following SARS-CoV-2 infection and their link to differing clinical outcomes47, and demonstrated the importance of pathogen panels over single-pathogen models in explaining diseases in pigs48. Building on these insights, our study employed a meta-transcriptomics approach with a study design encompassing diverse host ranges, geographic regions, seasonal variation, and tissue/transmission types, along with individual-level sequencing. In doing so, we revealed the macro-ecological patterns of diverse pathogens within mammalian species that are key reservoirs for various infectious diseases36,49. Our data provides insights into pathogen diversity, prevalence, seasonal trends, tissue tropism, and potential for cross-species transmission. This metagenomics-based ecological and epidemiological framework represents a powerful tool that can be readily adapted to study pathogens in other organisms or environments, offering valuable data for understanding and mitigating risks of pathogen transmission.

We identified 14 zoonotic pathogens in the small mammals sampled, although most of the pathogens identified were previously known species. For instance, Guangdong province has a relatively high incidence of Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome, with 93–328 cases reported each year between 2015 and 202150. The causative agent, Seoul orthohantavirus, is widespread in the region and constitutes a significant zoonotic threat in Guangdong, with a positivity rate of 3.47%. Wenzhou mammarenavirus is also highly prevalent in rodent populations (8.67%). This virus was initially identified in various small mammals, including rodents and shrews, in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province51. Since then, it has been widely detected across Southern China and Southeast Asia26,29,52,53,54,55,56. Despite its high positivity rate, the impact of Wenzhou mammarenavirus on humans remains unclear. While human seroprevalence is relatively high, viral RNA is rarely found in typical arenavirus-related illnesses, with the exception of a few respiratory cases54. This discrepancy may reflect limited viral adaptation to the human host or that human infections are largely asymptomatic or underdiagnosed.

One surprising finding was the high load of eukaryotic pathogens, all of which were confirmed through the phylogenetic analysis of marker genes. This suggests that the small mammals sampled are highly susceptible to these parasites, which have the potential to infect a variety of mammalian hosts, including humans and livestock57,58,59. Consequently, small mammals may act as key maintenance or amplifying hosts for these parasites58. This raises major public health concerns for two main reasons: (i) unlike viruses, eukaryotic pathogens have the potential to infect many groups of mammals, including humans60, and (ii) the potential transmission routes to humans are diverse, including direct contact, aerosolized particles, contaminated food or water, and arthropod vectors60,61. Additionally, the particularly high diversity of eukaryotic pathogens underscores the importance of adopting new surveillance approaches. Previous surveillance programs often excluded small mammals, and since it is challenging to detect these pathogens directly from the environment or intermediate hosts, monitoring their prevalence in mammalian hosts offers a more effective means of surveillance.

Our study revealed that the richness of pathogens in rodents is influenced by various ecological and biological factors. We observed significant seasonal, geographic, and host-related variations in pathogen diversity. Notably, the highest pathogen richness was found in B. indica, a rodent species more frequently captured in field settings than in residential areas. This is likely due to wild rodents having broader ecological interactions, occupying diverse habitats, and interacting with larger host communities that facilitate pathogen transmission. In contrast, commensal species of the genus Rattus are typically restricted to human dwellings and exhibit narrower ecological niches and lower species diversity, limiting pathogen exposure and spread14,36,58,62. Nevertheless, of the zoonotic pathogens, both B. indica and R. norvegicus exhibited high prevalence, underscoring that residential areas are not exempt from disease risk. Our analysis also revealed distinct host–geography and host–season interactions, highlighting the need to consider pathogen-specific transmission patterns for targeted surveillance and control. Importantly, as a cross-sectional study, our work necessarily only provides a snapshot of pathogen ecology: longitudinal monitoring is essential to capture temporal dynamics and support early detection of both known and emerging zoonoses.

In addition to pathogen richness, we compared pathogen composition across different samples. This revealed that host species is the most important factor shaping pathogen composition, consistent with many other studies of viruses in small mammals26,29,38. Despite this, our study identified several pathogens capable of infecting multiple host species, and, to a lesser extent, multiple host orders. Of particular note, we identified two RNA viruses, three DNA viruses, three bacteria, and two parasites that are capable of transmission between different host orders. Among these, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Klebsiella variicola, and Bartonella kosoyi are well-known zoonotic pathogens with broad host ranges, while Mischivirus E (Mischivirus ehoushre), Brachylaima sp, and Porcine bocavirus are less recognized for their ability to infect both animals and humans or are of unclear pathogenic nature. However, the fact that these viruses can infect both rodents and shrews suggests that they may be host generalists and hence are at threat of zoonotic spillover.

Our study has several limitations. First, while it represents the largest individual-level sample size to date, it remains limited with respect to the total number of individuals involved. Certain species, such as Mus caroli, Niviventer lotipes, and Berylmys bowersi, are still under-represented, although the total numbers of these animals may be small. Second, although our study focused on mammal-associated viruses—thereby excluding most microbes originating from food, parasites, or co-inhabiting organisms—we cannot entirely exclude the possibility of dietary material from mammalian sources being present in gut samples. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the results. Third, our study may underestimate pathogen diversity, particularly for bacteria and parasites, as we limited identification to known species or genera associated with human or animal disease. More distantly related microbes were excluded, leading to a conservative estimate of diversity. The focus on a limited set of organs also restricts the assessment of zoonotic potential: for instance, liver-specific pathogens like the Chinese liver fluke, endemic to Guangdong, may have been missed63,64,65. Similarly, kidney-tropic paramyxoviruses, including members of the genus Henipavirus, are also likely to have been missed66. Conversely, viral pathogen diversity may be overestimated, as some viruses classified within pathogenic families or genera may not be associated with disease. Fourth, the geographic scope of the study was restricted to Guangdong province, and future research should extend to other regions of China for a broader understanding. As we expand the geographic regions, sampling size, and organ types, we expect to better assess both the zoonotic potential and the ecological correlates of the pathogens carried by these important mammalian disease reservoirs. Finally, our stratification by species and location leads to relatively small sample sizes for certain combinations. Assessing disease prevalence and associated risks in these specific host groups or regions will therefore require more extensive sampling.

Methods

Sample collection

Small mammal samples, comprising rodents (Rodentia) and shrews (Eulipotyphla), were collected in Guangdong province, China, between 2021 and 2022 as part of the Guangdong CDC’s surveillance program for plague and hemorrhagic fever. Sampling was conducted across nine regions—Zhanjiang, Anpu, Maoming, Foshan, Heyuan, Jieyang, Shaoguan, Shenzhen, and Yunfu—each representing different geographical areas and natural habitats within the province. In most regions, collection occurred primarily during the late autumn and winter. However, in Anpu and Zhanjiang, sampling was conducted over the entire 12-month period of 2022.

Each sampling session lasted 3–4 consecutive days, depending on weather conditions, particularly the presence of rain. During each day of sampling, animals were captured using baited cages deployed in both agricultural and residential areas, with 200 cages allocated to each habitat type. A mixture of sweet potato, fried breadsticks, and cooked meat was used as bait to attract rodents. Residential trapping involved placing 2–3 cages at the corners of farmers’ homes, while 2–5 cages were deployed in brushwood or gullies of agricultural areas, with numbers adjusted according to field size. Cages were set at dusk and retrieved the following morning at sunrise. Captured animals were euthanized and then dissected to collect lung, spleen, and gut tissues, which were immediately preserved in RNA Stabilization Solution (ThermoFisher, USA), stored on dry ice, and later transferred to a –80 °C freezer.

All protocols for sample collection and processing were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU-IACUC-MED-2021-B0123)

Sample processing, RNA extraction and sequencing

RNA extraction and sequencing were performed on 2408 tissue samples from 858 individual animals. Each sample, approximately ~5–8 mm in size, was homogenized in 600 μl of lysis buffer using a TissueRuptor (Qiagen, Germany), followed by total RNA extraction with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the MGIEasy RNA Library Prep Kit V3.0 (BGI, China). In brief, RNA was fragmented, reverse-transcribed, and converted into double-stranded cDNA. Unique dual-indexed cDNA molecules were circularized, and rolling-circle replication was employed to generate DNA nanoball (DNB)-based libraries. These libraries were then sequenced on the DNBSEQ T series platform (MGI, China), producing 150-bp paired-end metatranscriptomic reads. The target yield for each sample was 50 Gbp.

Processing of sequencing data

For each sequence data set, the majority of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads were initially removed using URMAP (version 1.0.1480)67. Adapters, duplicate and low-quality reads were filtered out using fastp (version 0.20.1, parameters: -q 20, -n 5,-l 50,-y, -c, -D)68. The reads with low complexity were removed using PRINSEQ++ (version 1.2, options: -lc_entropy = 0.5 -lc_dust = 0.5)69. Residual rRNA reads were further eliminated by mapping to the SILVA rRNA database (Release 138.1)70 using Bowtie2 (version 2.3.5.1)71. Unless otherwise specified, all software was run with default settings.

Molecular identification of host species

The identification of small mammal species was based on de novo assembled contigs containing the cox1 gene sequences. For each sample, open reading frames (ORFs) from the assembled contigs were extracted using ORFfinder (version 0.4.3)72 and compared to cox1 reference sequences from the NCBI RefSeq database using the blastn program (version 2.14.1) with an e-value threshold of 10-10. To ensure accuracy, the core cox1 domain (cd01660) was confirmed using RPSBLAST against the Conserved Domain Database (CDD). Reads were subsequently mapped back to the assembled cox1 sequences to remove assembly errors. To finalize species assignments, a phylogenetic tree incorporating cox1 sequences from this study, along with representative related sequences, was estimated using PHYML 3.0 (version 20120412), employing the GTR + F + Γ4 nucleotide substitution model with SPR branch-swapping73.

Discovery of viruses and viral pathogens

The remaining clean non-rRNA reads were assembled into contigs using MEGAHIT (version 1.2.8)74 with default settings and a minimum contig length of 300 bp. Assembled contigs were then searched against the NCBI nr database using DIAMOND blastx (version 2.0.14)75 with an e-value cutoff of 10−5 to balance high sensitivity and reduce false positives. Contigs were provisionally categorized based on the NCBI taxonomy of the best-matching protein, and viral-related contigs were extracted. Host-related regions in the viral contigs were removed by aligning them against the NCBI RefSeq genome database using the blastn program (version 2.14.1)76 with an e-value cutoff of 10−10. Viral identities were further confirmed by checking for the presence of specific marker genes: the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) for RNA viruses, the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) for the Parvoviridae, the hexon for the Adenoviridae, the capsid protein (CP) for the Circoviridae, and the ORF1 protein for the Anelloviridae. These marker proteins were then aligned and examined manually to ensure they contained the conserved motif(s) of the corresponding protein. New virus species were determined according to the species demarcation criteria established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (Supplementary Data 5). To identify viruses associated with mammalian hosts, phylogenetic analyses were conducted for each virus supergroup (i.e., phylum or class level taxonomic groups). Only viral contigs that clustered within families known to infect mammals77 were classified as mammalian viral pathogens and retained for further analysis.

Discovery of bacterial and eukaryotic pathogens

The remaining contigs were screened against the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) using the rpsblast program (version 2.14.1)76, with an e-value cutoff of 0.01. We targeted contigs containing specific marker genes for identifying eukaryotic microbes, specifically cox1 (cd01663) and EF1a (cd01883), and bacteria, specifically ftsY (TIGR00064), GroEL (TIGR02348), nusG (TIGR00922), rplA (TIGR01169), rplC (TIGR03625), and rpoB (TIGR02013). To facilitate taxonomic identification and to remove false positives, the sequences of these marker genes were then compared against the nt and nr databases with e-values set to 10−10 and 10−5, respectively. For bacterial contigs, reads were mapped back to the homologous gene from the closest relative when applicable, or to the relevant contig if more distantly related, using Bowtie2 (version 2.3.5.1) in ‘end-to-end’ mode71. Species identification for both bacterial and eukaryotic microbes was then conducted through phylogenetic analyses involving these marker genes. Pathogenic microbes were identified based on their relationship to known bacterial and eukaryotic pathogens at the species and genus level.

Quantification of pathogen genomes/transcriptomes

To estimate pathogen abundance, reads were mapped to pathogen genomes (viruses and bacteria) or to a set of marker genes (for eukaryotes) using Bowtie2 (version 2.3.5.1, with end-to-end alignment). Pathogen abundance was measured as the number of reads mapped per million non-rRNA reads (RPM). Two criteria were applied to reduce potential false positives. First, index-hopping, which can occur during high-throughput sequencing when reads are misassigned between samples, was identified using the following rule: if the total read count for a specific virus in a given library was less than 0.1% of the highest read count for that virus in the same sequencing lane, it was considered a false positive due to index-hopping. Second, low-abundance pathogens (RPM < 1) and those with low genome or gene coverage (i.e., less than 300 base pairs) were also likely to be false positives and were excluded35,78.

Phylogenetic analyses

To determine the phylogenetic relationships and taxonomy of newly identified pathogens, representative marker proteins or genes related to those identified in this study were downloaded from NCBI/GenBank. Phylogenetic trees were then estimated at the genus or family level. Sequences were first aligned using the L-INS-i algorithm in MAFFT (version 7.520)79. Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were inferred using PhyML 3.0 (version 20120412)73, with the GTR substitution model used for nucleotide sequence alignments and the LG model used for amino acid sequence alignments. To find the optimal tree topology, we employed the default subtree pruning and regrafting (SPR) topology search algorithm and branch length optimization.

Collection and processing of environmental data for epidemiological analyses

To assess how environmental factors shape pathogen diversity and composition, we collected climate, mammal richness, land-use, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data for each sampling location from publicly available sources. Climate data were obtained from TerraClimate80, utilizing 14 variables to evaluate their influence on rodent pathogens. Definitions of these variables are available at the TerraClimate website (https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html). Mammal richness and land-use data were obtained from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)81, and China’s Multi-Period Land Use Land Cover Remote Sensing Monitoring Dataset (CNLUCC)82, respectively, while NDVI values were derived from publicly available remote sensing satellite data. To address co-linearity among the climate variables, we performed principal component (PC) analysis. The first three PCs—CPC1, CPC2, and CPC3—were used in subsequent statistical analyses, explaining 57.96%, 16.15%, and 11.40% of the total variance, respectively (cumulatively 85.51%). Based on the projection lengths of raw bioclimatic variables onto these PCs, we interpreted the components as follows:

(i) CPC1 primarily reflects negative correlations with temperature, shortwave radiation, evapotranspiration, and precipitation. Lower CPC1 values indicate higher temperatures and greater water evaporation.

(ii) CPC2 is mainly associated with wind and evapotranspiration. Higher CPC2 values suggest increased water evaporation and lower wind speeds, indicating a harsher thermal environment.

(iii) CPC3 captures precipitation variability, with higher values indicating greater fluctuation in precipitation levels.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1.

Assessing environmental and host factors influencing pathogen species richness

To investigate how environmental and host factors influence pathogen species richness, we applied generalized linear models using a negative binomial regression. The factors considered in the analysis included rodent species, environmental characteristics, date, and region of sample collection. Environmental characteristics comprised three principal components as described above (CPC1, CPC2, and CPC3), NDVI, and mammal richness. Model selection was performed based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), evaluating all possible combinations of variables using the MuMIn package in R. The contribution of each variable to model performance was determined by comparing the deviance explained by the full model to that of models where individual variables were removed.

Analysis of pathogen composition and cross-species transmission

We quantified the pathogens shared among animal species and visualized the results using the ComplexUpset package. The pathogen-sharing network was initially constructed using the ggraph package in R, refined through manual adjustments, and visualized using the ggplot2 package. In addition, we investigated the factors influencing pathogen composition (or number of shared pathogens between individual animals) by applying generalized linear models (GLMs), considering host phylogenetic distance, climate variations (Euclidean distance), land use variations, and spatial distance. The effect of each factor was quantified through a model selection process similar to that used in earlier analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject ID PRJNA1238520, and in the China National GeneBank (CNGB) under Sequence Archive ID CNP0004378. The assembled pathogen genomic sequences have been submitted to the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers PV605111–PV605345. The phylogenetic trees and their associated sequence collection and alignments are available in figshare under the link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28087307. Source data files are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All codes used in this study are available at the repository https://github.com/XinGY29/Infectome-Analysis-of-Small-Mammals-in-Southern-China

References

Belhadi, D. et al. The number of cases, mortality and treatments of viral hemorrhagic fevers: a systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010889 (2022).

He, Z. et al. Distribution and characteristics of human plague cases and Yersinia pestis isolates from 4 marmota plague foci, China, 1950–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 2544 (2021).

Barbieri, R. et al. Yersinia pestis: the natural history of plague. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e00044–e00119 (2020).

Teng, Z. et al. Human Rickettsia felis infections in mainland China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 997315 (2022).

Teng, Z.-Q. et al. Emergence of Astrakhan rickettsial fever in China. J. Infect. 88, 106136 (2024).

Fang, L.-Q. et al. Emerging tick-borne infections in mainland China: an increasing public health threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 1467–1479 (2015).

Qu, J. et al. Aetiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia in adults identified by combined detection methods: a multi-centre prospective study in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11, 556–566 (2022).

Sun, Q. et al. Rodent ecology and etiological investigation in China: results from vector biology surveillance—shandong province, China, 2012–2022. China CDC Wkly 6, 911 (2024).

Parola, P., Paddock, C. D. & Raoult, D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 719–756 (2005).

Matta, S. K., Rinkenberger, N., Dunay, I. R. & Sibley, L. D. Toxoplasma gondii infection and its implications within the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 467–480 (2021).

Pei, S. et al. Anthropogenic land consolidation intensifies zoonotic host diversity loss and disease transmission in human habitats. Nat. Ecol. Evol 9, 99–110 (2024).

Rulli, M. C., D’Odorico, P., Galli, N. & Hayman, D. T. Land-use change and the livestock revolution increase the risk of zoonotic coronavirus transmission from rhinolophid bats. Nat. Food 2, 409–416 (2021).

Mistrick, J. et al. Microbiome diversity and zoonotic bacterial pathogen prevalence in Peromyscus mice from agricultural landscapes and synanthropic habitats. Mol. Ecol. 33, e17309 (2024).

Ecke, F. et al. Population fluctuations and synanthropy explain transmission risk in rodent-borne zoonoses. Nat. Commun. 13, 7532 (2022).

Leung, N. H. & Milton, D. K. New WHO proposed terminology for respiratory pathogen transmission. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 453–454 (2024).

Watson, D. C. et al. Epidemiology of Hantavirus infections in humans: a comprehensive, global overview. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 40, 261–272 (2014).

Ko, A. I., Goarant, C. & Picardeau, M. Leptospira: the dawn of the molecular genetics era for an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 736–747 (2009).

Hill, D. & Dubey, J. P. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8, 634–640 (2002).

Lau, S. K. et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J. Virol. 89, 3076–3092 (2015).

Guo, W.-P. et al. Phylogeny and origins of hantaviruses harbored by bats, insectivores, and rodents. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003159 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Extensive genetic diversity and host range of rodent-borne coronaviruses. Virus Evol. 6, veaa078 (2020).

Drexler, J. F. et al. Evolutionary origins of hepatitis A virus in small mammals. PNAS 112, 15190–15195 (2015).

Kapoor, A. et al Identification of rodent homologs of hepatitis C virus and pegiviruses. MBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio00216-00213 (2013).

Vijaykrishna, D. et al. Long-term evolution and transmission dynamics of swine influenza A virus. Nature 473, 519–522 (2011).

Drexler, J. F. et al. Evidence for novel hepaciviruses in rodents. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003438 (2013).

Wu, Z. et al. Comparative analysis of rodent and small mammal viromes to better understand the wildlife origin of emerging infectious diseases. Microbiome 6, 1–14 (2018).

Williams, S.H. et al Viral diversity of house mice in New York City. MBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio01354-01317 (2018).

Haring, V. C. et al. Detection of novel orthoparamyxoviruses, orthonairoviruses and an orthohepevirus in European white-toothed shrews. Microb. Genom. 10, 001275 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Decoding the RNA viromes in rodent lungs provides new insight into the origin and evolutionary patterns of rodent-borne pathogens in Mainland Southeast Asia. Microbiome 9, 1–19 (2021).

Cui, X. et al. Virus diversity, wildlife-domestic animal circulation and potential zoonotic viruses of small mammals, pangolins and zoo animals. Nat. Commun. 14, 2488 (2023).

Ni, X.-B. et al. Metavirome of 31 tick species provides a compendium of 1,801 RNA virus genomes. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 162–173 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Substantial viral diversity in bats and rodents from East Africa: insights into evolution, recombination, and cocirculation. Microbiome 12, 72 (2024).

Zhang, J.-T. et al. Decoding the RNA viromes in shrew lungs along the eastern coast of China. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 68 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Novel henipa-like virus, Mojiang paramyxovirus, in rats, China, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1064 (2014).

Pan, Y.-F. et al. Metagenomic analysis of individual mosquito viromes reveals the geographical patterns and drivers of viral diversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 947–959 (2024).

Gibb, R. et al. Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems. Nature 584, 398–402 (2020).

Carlson, C. J. et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 607, 555–562 (2022).

Chen, Y.-M. et al. Host traits shape virome composition and virus transmission in wild small mammals. Cell 186, 4662–4675. e4612 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. ZOVER: the database of zoonotic and vector-borne viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D943–D949 (2022).

Olival, K. J. et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546, 646–650 (2017).

Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003).

Wang, D. The enigma of picobirnaviruses: viruses of animals, fungi, or bacteria? Curr. Opin. Virol. 54, 101232 (2022).

Sadiq, S., Holmes, E. C. & Mahar, J. E. Genomic and phylogenetic features of the Picobirnaviridae suggest microbial rather than animal hosts. Virus Evol. 10, veae033 (2024).

Kaczorowska, J. & Van Der Hoek, L. Human anelloviruses: diverse, omnipresent and commensal members of the virome. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 305–313 (2020).

Liang, G. & Bushman, F. D. The human virome: assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 514–527 (2021).

Cheng, M. et al. Deep longitudinal lower respiratory tract microbiome profiling reveals genome-resolved functional and evolutionary dynamics in critical illness. Nat. Commun. 15, 8361 (2024).

Xie, L. et al. The clinical outcome of COVID-19 is strongly associated with microbiome dynamics in the upper respiratory tract. J. Infect. 88, 106118 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. A total infectome approach to understand the etiology of infectious disease in pigs. Microbiome 10, 73 (2022).

Keesing, F. & Ostfeld, R. S. Emerging patterns in rodent-borne zoonotic diseases. Science 385, 1305–1310 (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. Epidemic characteristics and meteorological risk factors of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in 151 cities in China from 2015 to 2021: retrospective analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 10, e52221 (2024).

Li, K. et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel arenavirus harbored by Rodents and Shrews in Zhejiang province, China. Virology 476, 37–42 (2015).

Wu, J.-Y. et al. Genomic characterization of Wenzhou mammarenavirus detected in wild rodents in Guangzhou City, China. One Health 13, 100273 (2021).

Xie, Q. et al. Epidemiology and Genomic characteristics of arenavirus in rodents from the southeast coast of PR China. BMC Vet. Res. 19, 253 (2023).

Blasdell, K. R. et al. Evidence of human infection by a new mammarenavirus endemic to Southeastern Asia. Elife 5, e13135 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Prevalence of Wēnzhōu virus in small mammals in Yunnan Province, China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007049 (2019).

Tan, Z. et al. Virome profiling of rodents in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China: isolation and characterization of a new strain of Wenzhou virus. Virology 529, 122–134 (2019).

Islam, M. M. et al. Helminth parasites among rodents in the Middle East countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Animals 10, 2342 (2020).

Ibarra-Cerdeña, C.N. et al Rodents as key hosts of zoonotic pathogens and parasites in the Neotropics. In: Ecology of Wildlife Diseases in the Neotropics. (Springer, 2024).

Morand, S. et al. Global parasite and Rattus rodent invasions: the consequences for rodent-borne diseases. Integr. Zool. 10, 409–423 (2015).

Rees, E. M. et al. Transmission modelling of environmentally persistent zoonotic diseases: a systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e466–e478 (2021).

Barillas-Mury, C., Ribeiro, J. M. & Valenzuela, J. G. Understanding pathogen survival and transmission by arthropod vectors to prevent human disease. Science 377, eabc2757 (2022).

Keesing, F. & Ostfeld, R. S. Impacts of biodiversity and biodiversity loss on zoonotic diseases. PNAS 118, e2023540118 (2021).

Lun, Z.-R. et al. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 31–41 (2005).

Keiser, J. & Utzinger, J. Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 5, 1711–1726 (2004).

Tang, Z.-L., Huang, Y. & Yu, X.-B. Current status and perspectives of Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, omics, prevention and control. Infect. Dis. Poverty 5, 14–25 (2016).

Rima, B. et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: paramyxoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 1593–1594 (2019).

Edgar, R. URMAP, an ultra-fast read mapper. PeerJ 8, e9338 (2020).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Schmieder, R. & Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 863–864 (2011).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D38–D51 (2010).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Mihara, T. et al. Linking virus genomes with host taxonomy. Viruses 8, 66 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Individual bat virome analysis reveals co-infection and spillover among bats and virus zoonotic potential. Nat. Commun. 14, 4079 (2023).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. I. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data. 5, 1–12 (2018).

Rodrigues, A. S., Pilgrim, J. D., Lamoreux, J. F., Hoffmann, M. & Brooks, T. M. The value of the IUCN Red List for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 71–76 (2006).

Xu, X. et al China’s multi-period land use land cover remote sensing monitoring data set (CNLUCC). Resource and Environment Data Cloud Platform: Beijing, China, (2018).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC2607501 and 2024YFC2607502 to M.S., and 2021YFC2300905 to Z.-Q.D.), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (2022A1515011854 to M.S.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82341118 and 32270160 to M.S.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20200820145822023 to M.S.), Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (GZNL2023A01001 to M.S.), Open Project of BGI-Shenzhen Shenzhen 518000, China (BGIRSZ20210001 to M.S.), Guangdong Province “Pearl River Talent Plan” Innovation, Entrepreneurship Team Project (2019ZT08Y464 to M.S. and D.-X.W.), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Pathogen Detection for Emerging Infectious Disease Response (2023B1212010010 to X.Z. and J.J.L.) and the Fund of Shenzhen Key Laboratory (ZDSYS20220606100803007 to M.S.). E.C.H. was supported by an NHMRC (Australia) Investigator Award (GNT2017197) and by AIR@InnoHK, administered by the Innovation and Technology Commission, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. We gratefully acknowledge colleagues at BGI‑Shenzhen and the China National Genebank (CNGB) for library construction and sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z., E.C.H. and M.S.; Methodology, G.-Y.X., D.-X.W., X.Z., W.-C.W. and M.S.; Investigation, G.-Y.X., D.-X.W., X.Z., Q.-Q.C., H.-L.Z., W.-Q.Z, P.-B.S, Q.-Y.G., J.-B.K., M.-W.P., W.-C.W. and M.S.; Sample processing, G.-Y.X., M.-W.P., Y.-Q.L., J.W, S.-J.L., J.-X.C., G.-Y.L., X.H., Q.-Y.G., J.-B.K., H.-L.Z., P.-B.S, Z.-R.R., W.-Q. Z., J.-H.L., P.-H.J. and G.-P.K.; Writing – Original Draft, G.-Y.X. and M.S.; Writing – Review and Editing, All authors; Funding Acquisition, D.-X.W., X.Z., Z.-Q.D., and M.S.; Resources (sampling), G.-Y.X., M.-W.P., Y.-Q.L., Q.-Q.C., A.C., Z.P., D.-Q.L., S.-P.G., J.-J.L., W.-Q.L., J.W., J.-J.L., C.-Y.S. and J.-D.C.; Resources (Computational), D.-X.W., J.-H.L., Z.-Q.D., W.-C.W. and M.S.; Supervision, D.-X.W., X.Z., Z.-Q.D. and M.S..

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None declared.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Veasna Duong and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, G., Wang, D., Zhang, X. et al. Infectome analysis of small mammals in Southern China reveals pathogen ecology and emerging risks. Nat Commun 16, 11299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66462-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66462-9