Abstract

Sacrificial sodium-rich salts pre-sodiation is a safe and promising approach to supplement sodium-ion batteries with additional capacity for energy density enhancement. However, high-cost from additional solvent and low-utilization-ratio caused by loose electrical contact limit its practical application in slurry-coated electrodes. Herein, we demonstrate a dry-processing method to enable complete sodium oxalate decomposition and solvent-free production of thick electrodes. Distinct to particle aggregation in slurry-coated electrodes, a homogenous mixture of Na2C2O4 and conductive agents is generated and wraps Na3V2(PO4)3 particles after high-speed shear-mixing and hot-calendaring of dry-processing method, constructing intimate and durable electronic pathways, thus realizing theoretical decomposition capacity of Na2C2O4 in thick electrodes (54 mg cm-2). This strategy increases the lifespan by 200 cycles and energy density by 82.5% for all-dry-processing sodium-ion batteries with areal capacity of 5.4 mAh cm-2, which highlights the vital role of exploiting mechanical and thermal effects of dry-processing method in sustainable fabrication of high-energy sodium-ion batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) are promising candidates to achieve low-cost energy storage due to unlimited sodium source and sustainable electrode materials1,2,3. However, the widely application of SIBs is still limited due to the relatively low energy density compared to lithium-ion batteries, of which an important and solvable origin is low capacity caused by low initial coulombic efficiency (60–85%) of hard carbon (HC) negative electrode4,5. Pre-sodiation, by sacrificially decomposing sodium-rich compounds to sodium-ions, could effectively address the problem by compensating the irreversible capacity loss of negative electrode and saving sodium inventory of positive electrode6. On the other hand, pre-sodiation is the necessary procedure to solve the sodium deficiency of layered transition metal oxide (TMO) positive electrodes. Compared to O3-type, P2-type TMOs are promising positive electrode materials for SIBs due to their excellent ionic conductivity and cycling stability; while the capacity of the synthesized materials cannot be greater than 2/3 of the maximal value with retaining P2-type structure7. Instead, it is verified pre-sodiation can simultaneously replenish the capacity and retain P2 structure by electrochemical reaction8,9. However, new issues arise as using pre-sodiation, i.e., whether the pre-sodiation agents are safe during electrode production, whether the reaction products are non-toxic and easy to remove, and whether the pre-sodiation reaction damage the electrode structure10. Hence, it remains challenging to develop practical pre-sodiation methods that comply with existing manufacturing processes and do not interfere with the original battery performance.

Intensive work has been done to develop novel pre-sodiation materials and methods. Based on the reaction type11, these methods could be generally divided into electrochemical pretreatment12, chemical reaction13 and sacrificial sodium-rich salts14,15. Electrochemical pretreatments need to pre-cycle the negative electrodes in half cell to form stable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), then disassemble the half-cell to harvest the electrodes, and reassemble the full cell, which is only applicable in laboratory research. Chemical reaction methods achieve pre-sodiation by direct contact with sodium metal or soaking in sodium-containing organic solution. This method needs the manipulation of metallic sodium and can only be carried out in a glove box, which will inevitably increase production costs and safety issues. As comparison, sacrificial salts were added into the positive electrode during electrode production and in situ decomposed to sodium-ions during charging, which is the cost-effective and safe pre-sodaition method for SIBs16,17.

Various sodium-rich salts have been screened to use as pre-sodiation sacrificial salts, such as inorganic salts of NaN318, NaCrO219, and organic salts of Na2CO320, Na2C2O421, of which the scope is to find non-toxic salts with high capacity and low decomposition potential22. However, the capacity of these salts is generally lower than 400 mAh g–1. Therefore, the main research directions are increasing the capacity utilization ratio and reducing the decomposition potential. The common methods are reducing size to increase reaction surface area23, constructing abundant contact with conductive carbon24, adding catalyst to decrease reaction energy25. As a result, the particle size of the sacrificial reaction agents is generally reduced to lower than 5 μm21,25,26,27. Considering the mass ratio of sacrificial salts is typically over 10% of positive electrode materials28,29, introducing small-sized salts into the electrodes slurry for coating requires a large amount of solvent for dispersion30, which limit the electrode mass loading. Importantly, the organic solvent incurs high electrode production cost: (1) a large amount of energy from removing the solvent during drying the slurry-coated electrode; (2) high capital expense from multiple condensers or distillation towers to recycle the solvent; (3) detailed process and equipment controls to avoid explosion risks from highly flammable solvents. Moreover, the dissolved binder, polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), coated on the active material surfaces would increase the cell resistivity, thus reducing device energy and power densities. Also, sacrificial salts are tend to agglomerate in the slurry during drying process, which would form large voids in the PVDF film network by the produced gases during decomposition, which may cause damage of the electrode structure31. The disconnect with conductive carbon network cuts down the electronic pathways, hindering the fully decomposition of sacrificial salts. As elucidated in Fig. 1a, pre-sodiation using sacrificial salts may not be compatible with slurry-coating electrodes, yet to be taken seriously and addressed.

a–d and dry-processing e–h electrode, respectively. a Dispersing materials in solvent. b Slurry-coating and drying processes of slurry-coating electrodes. c Sectional structure of slurry-coating electrode before pre-sodaition. d Sectional structure of slurry-coating electrode after pre-sodaition. e Dry-mixing the powders in commercial blender. f Hot calendaring the electrode to reduce thickness and laminate with current collector. g Sectional structure of dry-processing electrode before pre-sodaition. h Sectional structure of dry-processing electrode after pre-sodaition.

Dry-processing electrode is an effective way to solve all the issues in slurry-coating electrodes, as shown in Fig. 1b. Dry-processing electrodes are made by dry-mixed powder at high speed (typically over 18,000 rpm) to make binder fibrillation, and then undergoing multiple hot rolling (100~200 °C) to obtain the required thickness and compacted density, and finally hot-calendared with current collector under low pressure to obtain electrode products32,33,34. Benefit from higher mechanical strength of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) fiber network compare to PVDF, dry-processing method produces electrodes with high thicknesses for high mass loading and large compacted density for close connection with the conductive agents35, which may facilitate complete sacrificial salts decomposition. In contrast, the electrode tap density of slurry-coating electrodes is low because the pressure used in the final roll-press is limited to prevent wrinkles in the current collectors, which in turn results in high resistance, low energy density, and poor cycle life. Importantly, as integrating with pre-sodiation, the voids generated by decomposition of sacrificial salts could adjust the porosity of dry-processing electrodes, which may accelerate the ion diffusion process29,36. Therefore, synergistic use dry-processing method and sacrificial salts pre-sodiation is expected to enable sustainable, high-capacity electrode production for high-energy-density and low-cost SIBs.

Herein, we have developed a dry-processing method to realize dense electrode with high mass loading for realizing complete sacrificial salts decomposition for practical application. The impacts of the electrode production method on distributions of sacrificial salt, Na2C2O4, were evaluated. We reveal that strong mechanical and thermal effect during high-speed shear-mixing and hot-calendaring process forms a homogenous mixture of Na2C2O4 and conductive agents in dry-processing electrode, comparing to particle aggregation in slurry-coating electrode. The formed electrode structure promises intimate and durable electronic migration pathways, which realizes a complete Na2C2O4 decomposition with theoretical capacity of 400 mAh g–1 at low potential of 4.16 V in dry-processing electrodes with a mass loading of 54 mg cm–2. Combined experimental characterization and model simulation, we demonstrate that the gas and voids formed by Na2C2O4 decomposition show synergistic function on increasing the porosity of dry-processing electrode, contributing to faster ion diffusion and larger rate capability. The feasibility of this electrode for large-scale manufacturing without using solvent was illustrated by roll-to-roll production in laboratory. Further, the application of the pre-sodaition dry-processing Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP) positive electrode was verified in SIB cells with dry-processing hard carbon negative electrodes, which exhibited high initial reversible capacity of 100.42 mAh g–1 along with high areal capacity of 5.4 mAh cm–2, and increased the lifespan by 200 cycles and energy density by 82.5% compare to SIB without pre-sodiation. While dry electrode fabrication and sacrificial salts have been separately reported, this work reveals a previously overlooked synergy: mechanical shear and thermal energy during dry processing induce plastic deformation of salts, fundamentally enabling their uniform dispersion and interfacial optimization. The strategy combining sacrificial salts pre-sodiation and dry-processing electrode can effectively boost the energy density and save production cost of SIBs for large-scale manufacturing.

Results

Production of dense presodiation positive electrodes with high loading

To overcome the intrinsic poor electronic conductivity of Na2C2O4, the commercial Na2C2O4 powder was ball-milled to reduce the particle size for enhanced contact with conductive agents. The morphology of ball-milled Na2C2O4 is obtained using scanning electron microscope (SEM) in Fig. 2a, b, which shows polyhedron with reduced particle sizes of ~2 μm. The electrochemical performance of ball-milled Na2C2O4 was further investigated using slurry-coating electrodes with Super P as conductive carbon, where the mass ratio of Na2C2O4, Super P and PVDF was 70:20:10. Using large amount of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent for dispersion, Na2C2O4 particles are evenly distributed in conductive carbon (Fig. 2c), contributing to efficient electron conductive network. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the charge and discharge curves of ball-milled Na2C2O4 electrode in a potential range of 2.5–4.5 V vs Na/Na+ under current density of 0.2 C (1 C = 400 mA g–1). The electrode exhibits initial charge capacity of 365.23 mAh g–1 with seldom no capacity in the subsequent cycles, proving the feasibility as a sacrificial agent for supplementary sodiation. However, the decomposition capacity is lower than the theoretical capacity of Na2C2O4 (400 mAh g–1) and the decomposition potential is high with value of ~4.3 V vs Na/Na+. The morphology of the electrode after cycling was tested to figure out the reason, where abundant voids (yellow circle) and residual Na2C2O4 particles (red circle) are observed in Fig. 2d. The residual Na2C2O4 particles are aggregated together without contact with the conductive agents, indicating the loose and fragile mechanic and electronic network of slurry-coating electrode hindering the full decomposition. The issue would be more announced when part of the Na2C2O4 is decomposed to gas, which would take away part of the conductive agents and cause structural damage31. Therefore, developing electrode structure with strong mechanic and electronic networks is crucial for cathodic pre-sodiation using sacrificial salts containing gas products, among which dry-processing electrodes are promising.

a, b Morphology of ball-milled Na2C2O4. c, d Morphology of Na2C2O4 electrode before and after charge to 4.5 V vs Na/Na+, where the pores and residual Na2C2O4 are highlighted using yellow and red circles. e, f Optical images and g, h height distribution of slurry-coating and dry-processing electrodes adding Na2C2O4. i Contour height of electrodes adding Na2C2O4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. j–m Sectional structure and schematics of slurry-coating and dry-processing electrodes. Where NCO and SP are Na2C2O4 and Super P. n Uniform dry-mixed powder. o Lab-scale roll to roll production of DP electrodes. p Winded DP electrodes.

The effect of ball-milled Na2C2O4 powder on electrode production was evaluated by fabricating two types of electrodes with Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP) as active material: conventional slurry-coating (SC) electrodes and dry-processing (DP) electrodes. Low solid content of 40% was applied in SC electrodes by adding NMP to prepare homogenous slurry with well fluidity for coating, which would further need more time for solvent-evaporating step. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a, a bumpy surface of SC electrode after coating process was observed, which might due to the alkaline Na2C2O4 triggers PVDF gelation37. Moreover, SC electrodes failed to provide sufficient mechanical adhesion for producing high-mass-loading electrodes, which was easy peeled off and powder shedding as the thickness reach ~230 μm shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. As comparison, DP electrodes are produced without using solvent and able to produce electrodes without thickness limitation. We fabricated DP electrodes by dry-mixed all the powders in commercial blender at high speed, where the coupled shear force and thermal effect ensured fibrillation of PTFE and uniform dispersion of powders. Supplementary Fig. 2b shows optical image of the free-standing DP film, which exhibits flat surface. The distinction is more convinced in the height distribution on the electrodes, which was obtained using optical microscopy in Fig. 2e–i. Compare to drastic contour height variation with maximum height difference of ~160 μm for SC electrodes, homogenous contour height was observed on DP electrodes, which only shows maximum height difference of ~35 μm. In summary, DP method realizes fabrication of thick, homogenous and smooth electrode containing Na2C2O4 powder, which is free of using solvent and avoids solvent evaporating and recycle step, demonstrating processability for large-scale and sustainable pre-sodiation electrode production.

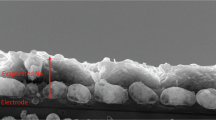

Furthermore, it is worthwhile to compare the electrode structures to illustrate the difference in the effects of the SC and DP methods on mechanical adhesion. The SC and DP electrodes were cut and milling using Ar+ to obtain intrinsic cross-sectional structure38, as shown in Fig. 2j, l, and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. In SC electrodes, loose contact between NVP particles with abundant pores are observed, where the PVDF binder only connects the adjacent active material particles through point-to-point adhesion (as illustrated in Fig. 2k). As comparison, benefiting from the long fiber skeleton formed by PTFE, the NVP particles in DP electrodes shows significantly improved contact with the conductive agents (darker contrast in Fig. 2l). As illustrated in Fig. 2m, The Na2C2O4 powders are closely dispersed in the gaps where the conductive agents are located, contributing to durable and unimpeded electronic pathways. As a result, the thickness of SC electrodes was limited to ~80 μm, of which the mass loading was 11 mg cm–2. DP electrodes can achieve continue production with thickness of ~400 μm and length of ~30 cm (Supplementary Fig. 2b, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2), corresponding to high mass loading of ~54 mg cm–2. According to the calculations in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, the compacted densities of SC and DP electrodes were 1.17 and 1.61 g cm–3, respectively, corresponding to porosities of 60.06% and 45.91%. The massive production of DP electrodes containing Na2C2O4 in the same electrode formula was verified using commercial and low-cost Na[Ni1/3Fe1/3Mn1/3]O2, where the dry-mixed powder, the roll-to-roll hot-calendaring process and winded DP electrodes are shown in Fig. 2n–p and Supplementary videos, respectively. Consequently, we achieve production of dense pre-sodiation positive electrodes with high loading using DP method, thereby establishing intimate electrical contact between NVP, conductive agents and Na2C2O4 powders.

Function Mechanisms of the DP electrodes on Na2C2O4 decomposition

The chemical compositions of electrodes were characterized to ramifications of different electrode structure on the decomposition of Na2C2O4. Differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) was conducted to monitor the evolution of carbon dioxide (CO2) for elucidating the accurate pathway, as the decomposition of Na2C2O4 only produces CO221,39. Figure 3a shows the correlation between electrode potential and dynamic gas evolution rate. Potential plateaus, ascribed to the decomposition of Na2C2O4, were observed in the potential curves of both SC and DP electrodes, which were started from 4.27 and 4.11 V and were accompanied by the production of CO2. According to the increase point of gas production rate, we found the actual decomposition of Na2C2O4 in DP electrodes begins at 3.51 V, while the onset potential was higher at 3.69 V in the SC electrode, clarifying that dense DP electrodes reduce the reaction overpotential of Na2C2O4 decomposition. Moreover, DP electrode shows larger plateau capacity accompanied by a longer CO2 production period compared to SC electrode, implying a greater proportion of the Na2C2O4 has decomposed in DP electrodes, which were further verified using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) tests. Figure 3b depicts the XRD patterns of SC and DP electrodes after charging to different potentials, which are as prepared, to 3.8 and to 4.5 V. The (410) diffraction peak of Na2C2O4 is chosen to clearly show the residual phases without interference by the signal from NVP, which locates at 2θ = 38.541° and highlighted using orange star. Compared with persistent (410) peak in SC electrodes, the (410) diffraction peak of Na2C2O4 in DP electrodes decreases in intensity as charged to 3.8 V and vanish entirely as charged to 4.5 V, which verifies the complete consumption of Na2C2O4 in DP electrodes. XPS spectra in Fig. 3c, d further corroborate the evolution process observed in the XRD patterns. In C 1s and O 1s spectra, the intensity of C=O bond (289 eV, 531.7 eV) in SC electrodes slightly decreased and maintained a high intensity as charged to 4.5 V, indicating that there was residual Na2C2O4 in the SC electrodes. In contrast, C=O signal vanishes in C 1s spectra and largely reduced in O 1 s spectra for DP electrodes charged to 4.5 V, again confirming the completely decomposition of Na2C2O4 in DP electrodes. The intensities of characteristic peaks ascribed to Na2C2O4 decreased as charging to 3.8 V for both SC and DP electrodes, which is in consistent with that the decomposition of Na2C2O4 starts before 3.8 V in Fig. 3a. In short, complete Na2C2O4 decomposition is achieved in dense DP electrodes, other than in loose SC electrodes, which shows a reduced reaction overpotential and a larger capacity.

To further explore the function mechanism of electrode fabrication method on Na2C2O4 decomposition, electrode structure after pre-sodiation process was comprehensive investigated. Figure 4a, b shows the surface morphology and the corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping images of SC electrode as charged to 4.5 V. From pronounced Na and O signal, severe aggregation of Na2C2O4 particles is observed in the pores between NVP particles. The Na2C2O4 aggregates are separated from the conductive carbon and exhibit an inconsistent distribution with the C signal, indicating that the incomplete decomposition is caused by disconnection of the electronic conductive pathway. Similarly, the remnants of Na2C2O4 clusters are observed in the cross-section of the SC electrode as charged to 4.5 V, which are highlighted in Fig. 4c, d. The dispersion limitations in slurry casting (SC) arise from two sequential effects: slurry-dispersion challenge and drying-induced redistribution. High surface area of Na2C2O4 particles necessitates excess solvent (NMP) to stabilize the dispersion - yet during drying, solvent evaporation generates capillary forces that cause crack formation and material inhomogeneity40,41. Supplementary Fig. 6a, b shows sectional morphology of slurry-coated electrodes after solvent drying, which provides evidence supporting the uneven and separated distribution between Na2C2O4 and conductive agents. Even under elevated calendaring pressure of ~50 MPa, aggregated Na2C2O4 domains persist, which fracture into isolated fragments, losing electrical contact with conductive networks (red arrows in Supplementary Fig. 6h, l).

a, b Morphology and EDX mapping of surface of SC electrodes charged to 4.5 V. The scale bar is 5 μm in Fig. 4b. c, d SEM images of section structure of SC electrodes charged to 4.5 V. e–h Morphology and EDX mapping of section structure of DP electrodes before and charged to 4.5 V. The scale bar is 5 μm in Figs. 4f and 4h. i DSC curves of Na2C2O4. j Force curves under different temperatures of Na2C2O4 during AFM tests. The inserted images are force curves under 200 and 250 °C. k Young’s modulus of Na2C2O4. The inserted image is the photograph of Na2C2O4 during molten tests as heated to 250 °C, which remained solid. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In contrast, no Na2C2O4 particles are observed on surface of DP electrodes as charged to 4.5 V, which is verified by the consistent distribution of Na, V, and P signals in Supplementary Fig. 7. The sectional structure was compared to figure out Na2C2O4 distribution inside the DP electrodes. As shown in Fig. 4e, dense electrode structure with two kinds of contrast is observed in the section of DP electrodes. According to V and C distribution in Fig. 4f, the light and dark phases are NVP and conductive carbon, respectively. Importantly, there is no polyhedron-shaped Na2C2O4 particle, while obvious Na signals are observed distributed in the gap between NVP particles. This Na signal is highly consistent with the C signal, indicating that DP method produces a homogeneous mixture consisting of conductive carbon and Na2C2O4, thus establishing an intimate and permanent electrical contact. Hence, complete Na2C2O4 decomposition is achieved as DP electrodes charging to 4.5 V, showing that the Na signal comes only from the NVP particles, which is the same distribution with the V, O, and P signal (Fig. 4g, h and Supplementary Fig. 8).

The physical properties of Na2C2O4 were tested to explain the change in Na2C2O4 morphology. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curve (Fig. 4i) shows no obvious endothermic peak as heating to the 300 °C, indicating the Na2C2O4 remained solid during fabrication of DP electrodes21, which is verified by the fact that Na2C2O4 remained solid during the melting point test (Fig. 4k). Further, the Young’s modulus of Na2C2O4 were tested using atomic force microscopy (AFM), showing a sharp drop in value at high temperatures in Fig. 4j, k and Supplementary Table 3. Specifically, Young’s modulus decreased to 71.3 and 30.3 MPa as the temperature is 100 and 150 °C, while it exhibits a high value of 609.7 MPa at 25 °C. Optical and SEM images of the material powder before and after dry-processing were compared in Supplementary Figs. 10 and11, in order to illustrate the enhanced Na2C2O4 dispersion in electrodes by salt deformability. The mixed powder appears uniformly gray, indicating that the Na2C2O4 and electrode materials are mixed evenly. After high-speed dry-mixing, Na2C2O4 particles exhibit rougher surface and decreased particle size (from ~2 μm to ~1 μm) than original state, confirming deformation. Different from Na2C2O4 aggregation inside slurry-coated electrodes in Supplementary Fig. 6, the bright white Na2C2O4 particles are evenly distributed on the surface of NVP particles. Moreover, the deformed Na2C2O4 particles were also inserted into the interior of the aggregated VGCF, which improves the dispersity of Na2C2O4 in VGCF. Importantly, the high roller pressure and heat during hot-calendaring at 120 °C further promote Na2C2O4 deformation and compress the mixture to form interlocked structure of VGCF and Na2C2O4, which appeared as a mixture of C–Na element distribution without the observed polygonal morphology of Na2C2O4 (Fig. 4e). This indicates that the mechanical and thermal effects of DP method play critical roles in intimate dispersing sacrificial salts, which deform the particles by shear force and the accompanying heat during high-speed dry-mixing process as well as compress the mixture during hot-calendaring process42.

Electrochemical properties of presodiation positive electrode

Having clarified the function mechanisms of DP electrodes on Na2C2O4 decomposition, the electrochemical performance of pre-sodiantion positive electrodes was further evaluated using half-cell. Figure 5a shows the initial two potential curves of SC and DP electrodes, which in initial cycle were charged to 4.5 V under 0.2 C, and in second cycle were charged to 3.8 V under 0.1 C. The decomposition of Na2C2O4 was observed as a plateau in initial cycle of both electrodes, of which distinct characteristics could be found. The decomposition of Na2C2O4 in SC electrodes shows noticeable high potential plateau at 4.36 V with limited capacity of 29.76 mAh g–1 based on the mass of NVP. The decreased electrode mass corresponds to a low decomposition capacity of 249.1 mAh g–1 based on the mass of Na2C2O4 (Supplementary Table 4), which is significantly short of theoretical value of 400 mAh g–1. Same incomplete Na2C2O4 decomposition was observed in SC electrodes calendared under 50 MPa, which show limited decomposition capacity of 250.1 mAh g–1, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12. The results indicate the Na2C2O4 decomposition in SC electrodes is incomplete and has sluggish kinetics with large overpotential, attributing to the Na2C2O4 aggregation and fragile electrical contact. In contrast, DP electrodes significantly reduce the plateau potential of Na2C2O4 to 4.16 V. Importantly, the decomposition of Na2C2O4 maintains a relatively stable potential, showing a flat plateau in the range of 4.16–4.23 V, indicating improved reaction kinetics with low overpotential. The decreased electrode mass corresponds to a capacity of 399.8 mAh g–1, which is equivalent to the capacity of the complete decomposition of Na2C2O4 (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 5). The performance of DP electrodes containing 20 wt% Na2C2O4 was further evaluated by analyzing decomposition capacity, electrode mass change and elemental distribution in Supplementary Figs. 14–16. Specifically, DP electrodes with 20 wt% Na2C2O4 maintain effective pre-sodiation with a decomposition capacity of 394.28 mAh g–1 based on the mass of Na2C2O4 (Supplementary Table 6). A comparative analysis of various pre-sodiation/lithiation positive electrode using sacrificial additives is presented in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 7, highlighting the advantages of our pre-sodiation positive electrode fabricated by DP method in both decomposition capacity and positive electrode mass loading for practical sodium supplementation.

a Potential curves of slurry-coating and dry-processing electrodes during presodiation process. The inserted graph compares the decomposition capacities of Na2C2O4, which was calculated based on the decreased electrode mass. b Literature summary of pre-sodiation/lithiation positive electrode using sacrificial additives by positive electrode mass loading and decomposition capacity of additives. The source of the literature data shown in this figure can be found in Supplementary Table 7. c Rate performances of dry-processing electrodes with and without presodiation. d–f EIS results from symmetric cells tests and corresponding resistances. g, h Potential curves during GITT tests and corresponding ion-diffusion properties and IR-Drops. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The rate performances of electrodes with and without pre-sodiation were evaluated and shown in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 17–19, which were charged to 4.5 V and 3.8 V in the initial cycle, respectively. DP electrode with pre-sodiation shows higher capacities of 100.9, 82.55, 48.17 and 105.98 mAh g–1 under current densities of 0.3, 0.5, 1.0 and back to 0.3 C than DP electrodes without pre-sodiation, which are 93.65, 67.17, 39.73 and 93.86 mAh g–1. As comparison, slightly reduced capacity value of ~1.47 mAh g–1 with severe increased voltage overpotential of ~0.0301 V are observed in SC electrode with pre-sodiation compare to SC electrode without pre-sodiation. These results indicate Na2C2O4 decomposition can improve reaction kinetics in DP electrodes, but deteriorate the performance of SC electrodes, which are further investigated by resistance analyzes.

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was tested using symmetric cells with two identical electrodes, which obtains the intrinsic resistances from the tested electrodes without the interference from sodium metal as testing in half-cells43. The EIS profile of DP and SC electrodes are shown in Fig. 5d, e and fitted using the equivalent circuit model (summarized in Supplementary Tables 8–11), which composed of ohmic resistance (Rohm), charge transfer resistance (RCT) and diffusion resistance (W). For comparison between SC and DP electrodes, the higher absolute impedance in DP electrodes versus SC counterparts is primarily attributable to differences in electrode thickness. Specifically, the DP electrode’s 5 times greater thickness inherently elevates its absolute impedance, even assuming identical intrinsic conductivity. Hence, absolute impedance comparisons across different electrode constructing method are less meaningful, and the resistance is compared between electrodes manufactured by the same procedure. For both SC and DP electrodes, Rohm increases by ~2 Ohm after pre-sodiation, which may due to the accumulation of side-reaction products of electrolytes during charging to 4.5 V. Larger RCT is also observed in SC electrodes after pre-sodiantion than SC electrodes without pre-sodiantion, causing larger internal polarization. In contrast, DP electrodes after pre-sodiantion show a reduced RCT from 118.1 to 107.1 Ohm of DP electrodes without pre-sodiation, which proves the fast kinetics obtained by Na2C2O4 decomposition, contributing to larger capacities under high current densities. The different results are caused by fact that Na2C2O4 was completely removed from the DP electrode and generates pores for enhanced electrolytes infiltration, while a certain amount of non-conductive Na2C2O4 remained in the SC electrode to hinder the electron transfer, as observed in Fig. 4a–d. The resistance relationship is consistent with the overpotentials of potential profiles in rate tests (Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18), where DP electrodes after pre-sodiation show lower overpotential than that of DP electrodes without pre-sodiantion, but SC electrodes after pre-sodiation show higher overpotential. The degrees of Na2C2O4 decomposition were further verified by weighing the electrode before and after charging to 4.5 V. As shown in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, the decreased mass was 62% of the Na2C2O4 added into SC electrode. In contrast, the decreased mass was equal to 99.82% of the Na2C2O4 added into DP electrode, again proving the complete Na2C2O4 decomposition by DP method. The consistency with chemical characterization, morphology observation and electrochemical performance verifies the synergistic effect of DP method and sacrificial salts pre-sodiation for high sodium utilization ratio and improved electrode performance.

To illustrate the influence of additional pores generated by Na2C2O4, the ion diffusion properties were investigated. The compacted densities and porosities of SC and DP electrode after pre-sodiation are compared in Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Tables 12 and 13. Tiny effects of generated pores are found for SC electrodes with compacted densities decreased by 0.06 g cm–3 and porosity increased by 2.91%, due to the incomplete Na2C2O4 decomposition and porous nature of original SC electrode. In contrast, DP electrodes show a significant reduced compacted densities from 1.61 to 1.41 g cm–3, of which the porosity increased from 45.91% to 53.84%, showing the feasibility of sacrificial salts pre-sodiation on structural adjustment. The ionic resistances (Rion) were calculated and summarized in Fig. 5f44. Specifically, Rion of DP electrodes decreased from 437 to 372.2 Ohm after pre-sodiation, while similar Rion of SC electrodes were observed before and after pre-sodiation. Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) results also support improved ion-diffusion properties of DP electrodes (Fig. 5g, h), where DP electrode after pre-sodiation exhibits much lower ion diffusion barriers and IR-Drops compare to DP electrode without pre-sodiation45. Hence, it is verified that the decomposition of Na2C2O4 effectively increase the porosity of the dense DP electrodes, thereby enhancing electrolytes infiltration and accelerating ion migration, further contributing to the reduced diffusion resistance and larger capacities.

Effect of sacrificial Na2C2O4 pre-sodiation on DP positive electrode

To evaluate the impact of pores on electrode structure, the morphology of surface and section of DP electrodes were characterized using SEM. The surfaces of DP electrodes before and after Na2C2O4 sacrificial decomposition are compared in Supplementary Fig. 21, which were separated by color segmentation and phase quantification based on contrast to vividly analyze the porosity of surface. The porosity of surface increased from 0.92% to 1.32%, contributing to better penetration of electrolyte into the DP electrodes, which also implies more volume inside the electrode is occupied by pores. Consequently, DP electrodes show increase in thickness from ~410 μm to ~425 μm after pre-sodaition process (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). Importantly, DP electrodes maintained intact and smooth structure without the detachment of active materials, demonstrating that strong mechanical skeleton formed by PTFE fibers is able to withstand internal pressure of the gas generated during pre-sodiation. Detailly, Fig. 6c, d shows that the pore size in DP electrodes was grown from ~250 nm to 1.5 μm after pre-sodiation process, resulting in an increase in the cross-sectional porosity from 6.5% to 9% (Fig. 6e–h and Supplementary Fig. 24), which were confirmed by more positions of sectional structure in Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26. These enlarged pores connected together to build an unobstructed electrolyte migration way along the thickness direction of DP electrodes, as illustrated in Fig. 6i.

a, b Variation of electrode thickness of DP electrodes after presodiation, of which the sectional structures were obtained by Ar-ion milling. c, d sectional structure and pores of DP electrodes before and after presodiation. e- h Color segmentation and phase quantification of electrode materials and pores. i Schematic illustration of the increased porosity without structural failure for enhanced electrolyte infiltration. 2D modeling results in terms of electrolyte concentration and state of sodiation (SOS) for DP electrodes without pre-sodiation (j, l) and with pre-sodiation (k, m). The bottom of electrodes is the location of current collector, and the top is the separator. n The simulated average electrolyte concentration in the pores of DP electrodes during sodiation under current density of 0.1 C, where 1 C is 100 mA g–1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A 2D modeling was conducted to gain insights of the advantages of increased porosity on electrolyte infiltration and ion diffusion. The geometry was re-constructed based on the sectional images in Fig. 6c, d46, which extracted the differences in the structure and number of pores. The variation of electrolyte concentration in the pores during discharging at 0.1 C are shown in Fig. 6j, k and Supplementary Videos 3,4, of which the initial states of both electrodes were set as 1 mol L–1. During discharging, sodium-ions are stored in the NVP particles, consumed in the electrolyte and replenished from separator, resulting in different electrolyte concentrations along the thickness direction. Benefiting from enlarged pore structure, DP electrode with pre-sodiation shows a lighter blue distribution near the current collector and also darker red distribution near separator compare to DP electrode without pre-sodiation. As summarized in Fig. 6n, DP electrode with pre-sodiation maintains average electrolyte concentration of 0.94 mol L–1 at the end of discharge (30,000 s), which is 59% higher than that of DP electrode without pre-sodiation. Consequently, DP electrode with pre-sodiation shows more amount of fully sodiated NVP particles after same discharge time in Fig. 6l, m, which achieves 5.8% higher average sodium concentration in NVP particles than that of DP electrodes without pre-sodiation at the end of discharge (Supplementary Fig. 27e). Under higher current density of 0.5 C (Supplementary Fig. 28), electrolyte concentration gradients between electrode sides intensify for DP electrodes without pre-sodiation; while DP electrode after pre-sodiation maintains high average electrolyte concentration of ~0.90 mol L–1, which shows red distribution throughout electrode thickness. The 2D modeling results verify that the enlarged pores reduce the electrolyte concentration polarization, supporting the enhanced ion diffusion kinetics and rate capabilities of DP electrodes achieved by pre-sodiation process.

Performance of all-DP SIBs with sodium replenishment

The application of DP pre-sodiation positive electrode using Na2C2O4 was demonstrated using coin-cell setup SIB full-cell of HC||NVP as testing vehicle. HC electrodes were made by DP method to realize high areal capacity with a mass loading of 23.31 mg cm–2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, DP HC electrodes show an areal capacity of 6.58 mAh cm–2, of which the reversible discharge capacity ratio of anode to cathode is ~1.2:1. Figure 7a and Supplementary Fig. 30 illustrate the successive decomposition of Na2C2O4 in SIB, exhibiting a fluctuating curve in 3.8–4.1 V and flat plateau in 4.1–4.25 V, which is in consistency to the gas evolution and electrochemical properties from DEMS and half-cell tests. SIB without pre-sodiation exhibits low discharge capacity of 63.51 mAh g–1 with a low initial coulombic efficiency of 59.2%, indicating large irreversible capacity, which is consumed by the formation of SEI on HC electrode and side-reaction of PTFE with sodium-ions in negative electrode47. Pre-sodiation compensates the large irreversible capacity of DP HC electrodes (the compensated capacity is summarized in Supplementary Table 14), which enables SIB to deliver higher reversible capacity of 100.42 mAh g–1 along with a high areal capacity of 5.4 mAh cm–2. As shown in Fig. 7b, c, SIB with pre-sodiation achieves consequently high rate capabilities with capacities of 101.52, 83.92, 59.12 and 81.99 mAh g–1 under current densities of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 C and back to 0.3 C. The corresponding voltage curves under various current densities are compared in Fig. 7c, where SIB with presodiation show both enlarged capacity and voltage interval without behavior of sodium plating, ensuring the safety of SIB. This promotes the enhancement of both energy density and power density of SIBs (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Table 15), which are 191.4 Wh L–1 @ 68.36 W L–1 under 1.58 mA cm–2, corresponding to 82.5% increasement of volumetric energy density under similar condition for SIB without pre-sodiation. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig. 31, SIB with pre-sodiation obtains stable cycling with a retained capacity of 76.03 mAh g–1 under 0.2 C after 100 cycles, while SIB without pre-sodiation shows fast capacity decay to 53.32 mAh g–1 after 100 cycles. Detailed voltage curves of SIBs upon cycling are depicted in Fig. 7f, g, which shows a noticeable stability and increase in average voltage for SIB with pre-sodiation, contributing to higher specific energy of 203.8 Wh kg–1 (based on active material mass of positive and negative electrode) with a slower decline rate. More importantly, the specific capacity of SIB with pre-sodiation remained at 61.95 mAh g–1 after 200 cycles, still higher than the capacity of 61.88 mAh g–1 in 4th cycle for SIB without pre-sodiation. These results highlight the enhancement of both cycle lifespan and energy density by using the DP pre-sodaition positive electrode. The improved interfacial passivation and stability by pre-sodiation were further investigated by analyzing the composition and structure of SEI on HC electrodes (Supplementary Figs. 32–34). Depth-resolved XPS and TEM collectively indicate that a Na2CO3-rich SEI was formed under influence of Na2C2O4 decomposition, which are closely arranged at the boundary of HC, contributing to a dense and complete protective layer for enhanced interfacial stability. By contrast, SEI formed without pre-sodiation treatment is organic-rich and does not completely cover the HC boundary. Moreover, high-temperature cycling test (40 °C) were tested to verify the interfacial stability in Supplementary Fig. 35, where SIB with pre-sodiation retained 80.3% and 77.2% capacity after 30 cycles under current densities of 0.1 C and 0.2 C, respectively. Comparing to the state-of-the-art SIBs with sodium replenishment in Fig. 7h and Supplementary Table 12, the DP produced pre-sodiation positive electrode in our work enables all-DP SIB to achieve competitive overall performances, especially in aspects of largest capacity after longest cycling under highest current densities with the highest sustainability and low cost.

a Potential curves in initial two cycles of full cells with/without presodiation. b, c Rate performance and corresponding potential curves under various current densities, where 1 C is 100 mA g–1. d Volumetric energy densities and power densities of full cells, which are calculated based on overall thickness of positive electrode, negative electrode and separator. e Long cycle performance of SIBs under current density of 0.2 C, which were pre-cycled at 0.1 C for stabilization. f Potential curves during cycle tests. g Average voltage and specific energy (based on active material mass of NVP and HC) of full cells during cycling. h Performance comparison of HC||NVP full cells with sodium replenishment. The source of the literature data shown in this figure can be found in Supplementary Table 16. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In conclusion, we achieve sustainable high-capacity positive electrode via synergistic function of dry-processing method and sacrificial Na2C2O4 pre-sodiation for practical SIBs. The uniform dispersion of Na2C2O4 in high mass loading electrodes was achieved via solvent-free DP method, which not only provide sufficient mechanical adhesion for thick electrode without limitation, but also produces a homogenous mixture of Na2C2O4 and conductive agents by shear-force, compression-force and thermal effect. The established electrode structure possesses intimate and durable electric migration pathways, guarantying a low potential of 4.16 V and a high capacity of 399.8 mAh g–1 for Na2C2O4 decomposition. Simultaneously, the produced gas and voids by Na2C2O4 decomposition increased the porosity and adjusted the pore structure of DP electrodes, enabling better electrolyte penetration and ion diffusion for improved rate performance. Coupled with DP HC negative electrodes, the pre-sodation positive electrode made by this approach achieve SIBs with competitive overall performances under high areal capacity of 5.4 mAh cm–2, which deliver high reversible capacity of 101.52 mAh g–1, large energy density of 191.4 Wh L–1 @ 68.36 W L–1 under 1.58 mA cm–2, and stable cycling with retained capacity of 61.95 mAh g–1 after 200 cycles under 0.2 C. The continue manufacturing of the proposed DP electrodes is verified by roll-to-roll production in lab-scale. The present strategy shed lights on the crucial role of mixing and calendaring process of industrial DP method on properties and performance of electrode, which also provide guidelines for producing high-energy-density and low-cost SIBs.

Methods

Electrode preparation

Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP), hard carbon (HC), Super P, vapor-grown carbon fiber (VGCF), PVDF, PTFE were purchased from Shenzhen Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd, China. Sodium metal counter electrode (450 μm thickness and 15.6 mm diameter) was purchased from Canrd Technology. Celgard 2500 and Glass fiber (GF/A, Whatman) were purchased from Canrd Technology. Electrolytes with formula of 1 M NaPF6 in diglyme and 1 M NaClO4 in EC:DEC (1:1 in vol%) with 5% FEC were purchased from DoDoChem, Ins., China, which were used without further treatment. Sodium oxalate (Na2C2O4) was purchased from Sinopharm chemical reagent Co., Ltd, China, which was ball-milled with ethanol as solvent for 4 h at a rotating speed of 500 r min–1 to reduce the particle size.

Na2C2O4 electrodes were slurry-coated on Al foil, of which the mass ratio of Na2C2O4, Super P and PVDF was 70:20:10. Pre-sodiation positive electrodes were made by slurry-coating and dry-processing methods. For slurry-coated positive electrode, slurry composed of NVP, VGCF, Super P, PVDF and Na2C2O4 in a mass ratio of 90:1:3:6:9 was mixed using NMP and coated on Al foil, of which the solid content was around 40%. The electrodes were dried at 80 °C in vacuum for 8 h to remove the NMP. After drying, the electrodes were calendared under pressure of ~10 MPa, of which the thickness was decreased from 120 to 80 μm. The mass loading of slurry-coated electrodes is ~11 mg cm–2. For dry-processing electrode, NVP, VGCF, PTFE and Na2C2O4 were dry-mixed in a mass ratio of 90:4:6:10 using commercial blender, which were mixed in high speed of 18,000 rpm. Then, the uniform powder was hot-calendared under 120 °C to form self-supported film with thickness of ~400 μm, of which the mass loading is ~54 mg cm–2. Dry-processing HC electrodes were fabricated by same procedure, of which the mass ratio of HC, VGCF and PTFE was 95:3:2. The dry-processing HC electrodes were hot-calendared to thickness of ~300 μm, of which the mass loading is ~23 mg cm–2. The positive and negative electrode were punched into disks with diameters of 12 mm and 13 mm for coin cells, respectively. All electrodes were dried at 80 °C in vacuum overnight before use. The separator was punched into disks with diameters of 19 mm, which were dried at 60 °C in vacuum overnight before use.

Electrochemical measurements

All cells were assembled in Ar-filled glovebox with water and oxygen content below 0.1 ppm. Half cells were fabricated using 450 μm sodium metal foil as counter electrode, 1 M NaPF6 in diglyme as electrolytes, and Glass fiber as separator. 100 μL electrolyte was added in half cells to standardize. The ether-based electrolyte is used for reduce the ohmic polarization of sodium metal counter electrode to obtain capacity properties of both positive and negative electrode; while the significant overpotential of sodium metal in ester electrolyte leads to undetected capacity of HC below 0.1 V vs Na/Na+5. Full cells were fabricated using dry-processing NVP as positive electrode and dry-processing HC electrodes as negative electrode, 1 M NaClO4 in EC:DEC (1:1 in vol%) with 5% FEC as electrolytes, and Celgard 2500 as separator. 80 μL electrolyte was added in HC||NVP full cells to standardize. Symmetric cells were fabricated using two same electrodes with Glass fiber as separator, which were used to obtain actual resistance without interference from sodium metal electrodes in half cell. 50 μL electrolyte was added in symmetric cells to standardize. The galvanostatic charge and discharge tests were conducted using Neware battery test system (CT-4008T-5V50mA-164, Shenzhen, China) at room temperature (25 °C). All the electrochemical experiments have been tested three times for reproductivity, and the data reported in the graphs refers to a single cell. Specific capacity was calculated based on the active materials. For the GITT measurements, the ten data points were acquired per second. The volumetric energy densities and power densities during rate tests were calculated based on thickness and area of positive electrode (410 and 425 μm), negative electrode (300 μm), separator (16 μm) and current collectors (2 × 18 μm). The gravimetric energy densities during cycling tests were calculated based on active mass of positive and negative electrode. EIS measurements were performed on BioLogic VMP3 system at room temperature (25 °C), which were conducted using symmetric cell at the open circuit voltage within the frequency of 10–2–106 Hz. The amplitude of potentiostatic perturbation during EIS tests was 10 mV.

Characterization

The cycled coin cells were disassembled in Ar-filled glove box for the preparation of electrode samples. The NVP and HC electrodes were sealed in Ar-filled bag before characterization. SEM and EDX was conducted using Zeiss Sigma 300. Height distribution was measured using optical microscope (KEYENCE, VR-5000). XPS was conducted using Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+. During in-depth XPS test of HC electrodes, the electrodes were etched using Ar-ions. The etching rate was 0.2 nm s–1 (corresponds to the standard Ta2O5 samples). Raman spectroscopy was conducted using Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution, of which the spot size was 1 μm. XRD measurements were carried out on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). DEMS was conducted using mass spectrometer (QAS100, Linglu Instruments). DSC of Na2C2O4 was tested using Netzsch STA 449 F3 under heating rate of 5 °C min–1 in temperature interval of 30–300 °C. Molten point tests of Na2C2O4 were conducted using Buchi M-560 melting point system under heating rate of 10 °C min–1 to 250 °C. Young’s modulus of Na2C2O4 were calculated from force curves under different temperatures tested using AFM, which were conducted using Bruker Dimension XR under temperatures of 25, 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 °C. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) characterizations of SEI were obtained using field-emission transmission electron microscope (TEM, Talos F200X, 200 kV, Thermo Scientific, US).

Modeling

The geometry was re-constructed based on the sectional SEM images, which was figured, meshed and simulated using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2. The electrochemical model equations were derived based on lithium-ion batteries35,48,49. The electrochemical model parameters were set based on literature50,51,52. The equilibrium potentials of dry-processing NVP electrodes were fitted from Supplementary Fig. 17. It was assumed that the electrolyte concentration was uniformly distributed in the entire geometry and the state of sodiation of NVP particles was 10% in initial state.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, J., Li, X., Mi, L. & Chen, W. Emerging presodiation strategies for long-life sodium-ion batteries. Energy Lab. 1, 230008 (2023).

Hirsh, H. S. et al. Sodium-ion batteries paving the way for grid energy storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001274 (2020).

Tarascon, J.-M. Na-ion versus Li-ion batteries: complementarity rather than competitiveness. Joule 4, 1616–1620 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Full-cell presodiation strategy to enable high-performance Na-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302514 (2023).

LeGe, N. et al. Reappraisal of hard carbon anodes for practical lithium/sodium-ion batteries from the perspective of full-cell matters. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 5688–5720 (2023).

Jin, L. et al. Progress and perspectives on pre-lithiation technologies for lithium ion capacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 2341–2362 (2020).

Dewar, D. & Glushenkov, A. M. Optimisation of sodium-based energy storage cells using pre-sodiation: a perspective on the emerging field. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 1380–1401 (2021).

Mortemard de Boisse, B., Carlier, D., Guignard, M., Bourgeois, L. & Delmas, C. P2-NaxMn1/2Fe1/2O2 phase used as positive electrode in Na batteries: structural changes induced by the electrochemical (De)intercalation process. Inorg. Chem. 53, 11197–11205 (2014).

Martinez De Ilarduya, J. et al. NaN3 addition, a strategy to overcome the problem of sodium deficiency in P2-Na0.67[Fe0.5Mn0.5]O2 cathode for sodium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 337, 197–203 (2017).

Jin, L. et al. Pre-lithiation strategies for next-generation practical lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 8, 2005031 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Access to advanced sodium-ion batteries by presodiation: principles and applications. J. Energy Chem. 92, 162–175 (2024).

Moeez, I. et al. Effect of the interfacial protective layer on the NaFe0.5Ni0.5O2 cathode for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 13964–13970 (2020).

Kapaev, R. R. & Stevenson, K. J. Solution-based chemical pre-alkaliation of metal-ion battery cathode materials for increased capacity. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 11771–11777 (2021).

Martínez De Ilarduya, J. et al. Towards high energy density, low cost and safe Na-ion full-cell using P2–Na0.67[Fe0.5Mn0.5]O2 and Na2C4O4 sacrificial salt. Electrochim. Acta. 321, 134693 (2019).

Zou, K. et al. Molecularly compensated pre-metallation strategy for metal-ion batteries and capacitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17070–17079 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. Lattice Engineering on Li2CO3-based sacrificial cathode prelithiation agent for improving the energy density of Li-ion battery full-cell. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312159 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Implanting transition metal into Li2O-based cathode prelithiation agent for high-energy-density and long-life Li-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316112 (2024).

Singh, G. et al. An approach to overcome first cycle irreversible capacity in P2-Na2/3[Fe1/2Mn1/2]O2. Electrochem. Commun. 37, 61–63 (2013).

Shen, B. et al. Manipulating irreversible phase transition of NaCrO2 towards an effective sodium compensation additive for superior sodium-ion full cells. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 553, 524–529 (2019).

Sun, C. et al. A presodiation strategy with high efficiency by utilizing low-price and eco-friendly Na2CO3 as the sacrificial salt towards high-performance pouch sodium-ion capacitors. J. Power Sources 515, 230628 (2021).

Niu, Y.-B. et al. High-efficiency cathode sodium compensation for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001419 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Achieving high-capacity cathode presodiation agent via triggering anionic oxidation activity in sodium oxide. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407720 (2024).

Huang, G. et al. Boosting the capability of Li2C2O4 as cathode pre-lithiation additive for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Res. 16, 3872–3878 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Rich-carbonyl carbon catalysis facilitating the Li2CO3 decomposition for cathode lithium compensation agent. Small 20, 2311891 (2024).

Zhong, W. et al. Scalable spray-dried high-capacity MoC1-x/NC-Li2C2O4 prelithiation composite for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 68, 103318 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Unlocking the decomposition limitations of the Li2C2O4 for highly efficient cathode preliathiations. Adv. Powder Mater. 3, 100215 (2024).

Jo, J. H. et al. New insight into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt as a sacrificing sodium ion source for sodium-deficient cathode materials for full cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 5957–5965 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. A multifunctional cathode sodiation additive for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 25546–25555 (2022).

Hu, L. et al. Sodium acetate as residual-free presodiation additive for enhancing the energy density of sodium-ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 1148–1157 (2024).

Arnaiz, M. et al. Roll-to-roll double side electrode processing for the development of pre-lithiated 80 F lithium-ion capacitor prototypes. J. Phys. Energy 6, 015001 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Controllable long-term lithium replenishment for enhancing energy density and cycle life of lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 1163–1174 (2024).

Tao, R. et al. High-throughput and high-performance lithium-ion batteries via dry processing. Chem. Eng. J. 471, 144300 (2023).

Li, J., Fleetwood, J., Hawley, W. B. & Kays, W. From materials to cell: state-of-the-art and prospective technologies for lithium-ion battery electrode processing. Chem. Rev. 122, 903–956 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Progress in solvent-free dry-film technology for batteries and supercapacitors. Mater. Today 55, 92–109 (2022).

Yao, W. et al. A 5 V-class cobalt-free battery cathode with high loading enabled by dry coating. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1620–1630 (2023).

Fu, X. et al. Rethinking the electrode multiscale microstructures: a review on structuring strategies toward battery manufacturing genome. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301385 (2023).

Xiao, J., Shi, F., Glossmann, T., Burnett, C. & Liu, Z. From laboratory innovations to materials manufacturing for lithium-based batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 329–339 (2023).

Kim, J.-H. et al. Regulating electrostatic phenomena by cationic polymer binder for scalable high-areal-capacity Li battery electrodes. Nat. Commun. 14, 5721 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. High-efficacy multi-sodium carboxylate self-sacrificed additives for high energy density sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 70, 103511 (2024).

Du, Z. et al. Enabling aqueous processing for crack-free thick electrodes. J. Power Sources 354, 200–206 (2017).

Kim, J.-H., Kim, J.-M., Cho, S.-K., Kim, N.-Y. & Lee, S.-Y. Redox-homogeneous, gel electrolyte-embedded high-mass-loading cathodes for high-energy lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 2541 (2022).

Lee, D. et al. Shear force effect of the dry process on cathode contact coverage in all-solid-state batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 4763 (2024).

Qin, N. et al. Over-potential tailored thin and dense lithium carbonate growth in solid electrolyte interphase for advanced lithium ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2103402 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Roll-to-roll solvent-free manufactured electrodes for fast-charging batteries. Joule 7, 952–970 (2023).

Qin, N. et al. Decoupling accurate electrochemical behaviors for high-capacity electrodes via reviving three-electrode vehicles. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2204077 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Coupling of multiscale imaging analysis and computational modeling for understanding thick cathode degradation mechanisms. Joule 7, 201–220 (2023).

Wei, Z. et al. Removing electrochemical constraints on polytetrafluoroethylene as dry-process binder for high-loading graphite anodes. Joule 8, 1350–1363 (2024).

Doyle, M., Fuller, T. F. & Newman, J. Modeling of galvanostatic charge and discharge of the lithium/polymer/insertion cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 140, 1526 (1993).

Fuller, T. F., Doyle, M. & Newman, J. Simulation and optimization of the dual lithium ion insertion cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141, 1 (1994).

Chen, Y., Xu, Y., Sun, X. & Wang, C. Effect of Al substitution on the enhanced electrochemical performance and strong structure stability of Na3V2(PO4)3/C composite cathode for sodium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 375, 82–92 (2018).

Chayambuka, K., Mulder, G., Danilov, D. L. & Notten, P. H. L. Sodium-ion battery materials and electrochemical properties reviewed. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1800079 (2018).

Chayambuka, K., Jiang, M., Mulder, G., Danilov, D. L. & Notten, P. H. L. Physics-based modeling of sodium-ion batteries part I: Experimental parameter determination. Electrochim. Acta. 404, 139726 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Nos. 52307249, Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Province, Nos.23ZR1465900, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities at Tongji University, Nos. PA2022000668/22120220426, Nanchang Automotive Institute of Intelligence & New Energy of Tongji University, Nos. TPD-TC202211-02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Q., J.Z. and L.J. conceived the research idea. N.Q. and L.J. designed the experiments. N.Q., Y.L. and J.C. carried out experiments and characterization. H.Y. and C.F. conducted the modeling and analysis. C.Z. and Z.C. participated in the scientific and figure discussion. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the data analysis. N.Q. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. J.Z. and L.J. supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hyun-Wook Lee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, N., Li, Y., Yang, H. et al. Integrating dry-processing and pre-sodiation enables high-energy sodium ion batteries. Nat Commun 16, 11474 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66492-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66492-3