Abstract

Brucellosis is a neglected zoonotic disease impacting agricultural economies, as well as animal and human health globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, brucellosis is considered endemic in many countries based on serological evidence, although the presence and distribution of specific Brucella species remain unverified due to limited bacteriological confirmation. Due to the economic importance and national/international trade routes, this cross-sectional study investigates Brucella prevalence in 4612 animals (cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs) from slaughterhouses in the Far-North, North, and West regions of Cameroon sampled between February 2021 and May 2023. The analysis includes serology (Rose Bengal Test and indirect Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay), culture, real-time PCR, and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Results show only Brucella abortus is present, primarily affecting cattle (8.3%) and goats (7.3%). NGS reveals the local B. abortus strain is related to the clade from Uganda and Sudan, indicating it is endemic to Africa, rather than introduced from outside the continent. These results confirm the presence of a genetically distinct African lineage and reinforce brucellosis as a major concern for both animal and public health. The study emphasizes the critical need for coordinated surveillance systems to support evidence-based control strategies, enhance disease monitoring, and reduce the risk of transboundary transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease caused by Gram-negative bacteria from the genus Brucella. Currently, three Brucella species are known to cause highly virulent infections in their respective primary animal hosts as well as to humans: Brucella abortus (cattle), Brucella melitensis (sheep and goats), and Brucella suis (swine)1,2,3. Brucellosis is of significant importance in agricultural economies dependent on livestock due to abortion and infertility, a decrease in milk production, as well as delivery of weak offspring, contributing to direct and indirect losses1,3. Commonly, transmission of this bacterium among animals occurs through aerosolization, mainly during contact with infected uterine secretions, fetal membranes, or aborted fetuses3,4. In humans, the disease is associated with substantial morbidity worldwide, with an estimate of 2.1 million new cases per year (potentially as high as 7 million), with the majority of risk occurring in Africa5. Transmission to humans primarily occurs via the consumption of unpasteurized milk products, as well as handling contaminated reproductive tissues such as aborted placentas, which puts animal handlers, abattoir workers, and veterinarians at a higher risk for acquiring the disease1,3. Clinical manifestation is generally characterized by non-specific influenza-like symptoms such as fever, fatigue, sweats, malaise, and arthritis. If left untreated, it can lead to life-threatening conditions such as endocarditis and neurological disorders3,6.

The disease is known to be endemic in many parts of the world, with the majority of the cases likely occurring in Africa, followed by Asia and the Middle East5,7. Despite the population of Africa sustaining the greatest risk of infection, the nature and extent of the disease in this continent remain unknown due to several challenges, including inadequate or non-existent diagnostic capabilities, suboptimal surveillance, and control systems, coupled with low awareness of the disease among veterinary and human health professionals8,9,10.

In this cross-sectional study conducted throughout Cameroon, a country in West Africa where both a comprehensive national brucellosis surveillance system and a vaccination-based control program are lacking, we: (1) isolated and characterized the circulating Brucella species, (2) identified which of the main livestock species are affected (cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs), and (3) estimated associated prevalences in these livestock. This country was strategically selected for this study due to the 1) current unknown status of the disease9, (2) previous assumption that brucellosis is endemic within this region9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, (3) large number of livestock present in the country9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, and 4) porous national borders that provided an opportunity to gain a regional understanding of the disease and its transboundary movement9,10.

Our study identified that cattle are the primary livestock affected, and B. abortus was the only Brucella species detected in the country. Moreover, next-generation sequencing demonstrated that the bacterial isolates were related to the B. abortus Tulya clade originating from the Uganda and Sudan region of eastern sub-Saharan Africa, rather than the well-known 2308, S19, RB51, and 544 strains, indicating that it is an endemic strain that was not imported from outside of the continent.

Results

Between February 2021 and May 2023, serum and submandibular lymph node samples were taken from a total of 4612 animals (cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs) in the Far North, North, and West regions of Cameroon. Test outcomes for culture, real-time PCR, Rose Bengal Test (RBT), and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA) are summarized in Table 1. These results provide a comprehensive overview of Brucella detection across multiple diagnostic platforms and geographic zones.

Bacterial culture and isolation, and real-time PCR analysis

Brucella isolation was achieved in cattle lymph nodes. No bacterial isolation was obtained in other livestock species or tissue specimens. Countrywide, 0.8% (10/1,181) of cattle were culture positive (Table 1). Regionally, 1.0% (4/400) of cattle were positive in the Far North, 0.7% (3/401) in the North, and 0.8% (3/380) in the West (Table 1). When all bacterial isolates were subjected to real-time PCR using species-specific primers (Table 2), all 10 isolates were identified as B. abortus.

To assess the possibility of using real-time PCR directly on tissues, DNA was extracted from submandibular lymph nodes and subjected to the assay. Using this approach, Brucella was detected in an additional 26 animals (12 cattle, 10 goats, 3 pigs, and 1 sheep) and identified as B. abortus via real-time PCR (Table 1). No cases of B. melitensis or B. suis were identified. The geographic distribution of B. abortus cases by animal species is provided in Table 1.

Next-generation sequencing

All bovine isolates were sequenced and phylogenetically placed despite being only metagenomes alongside the sequence data and the publicly available genomes as described in the methods (Fig. 1). Most of the strains sequenced for this study were closely related to the biovar 3 reference strain, Tulya (Fig. 1). Two strains, BN008 and BO063, were closely related to the strain 2308 reference genome as well as to two vaccine strains (S19 and RB51) (Fig. 1).

Generated from a matrix containing 9721 polymorphic sites. Isolates are from three different sources: whole genome assemblies (black), sequence read archive (red), and sequence data from isolates collected and generated for this study (green). All bootstrap values were 100, excluding the branch highlighted in light blue circle, which was 67. Scale bar indicates 1000 SNPs.

Serological analysis

All serum samples from cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs were analyzed via RBT to determine their rates of seropositivity. In the case of cattle and goats, a series testing strategy was utilized in which RBT was followed by iELISA to increase the specificity of the results. Series testing was only performed in cattle and goats due to the fact that only three pigs and one sheep tested positive by real-time PCR, and neither had culture-positive samples (i.e., true positives). Consequently, iELISA cut-off values could only be determined for cattle and goats, preventing pigs and sheep from being included in this analysis. In this series testing strategy, a serum sample was considered positive only when both RBT and iELISA were positive, while a negative result on either test was classified as negative. In sheep and pigs, in which iELISAs were not used, seropositivity was determined by RBT results.

Culture and real-time PCR were used to establish diagnostic thresholds for iELISA in cattle and goats through a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis. For this analysis, animals that were positive by culture and/or real-time PCR were regarded as true positives, and those that were negative by culture and real-time PCR were regarded as true negatives. The ROC threshold was then chosen as the iELISA value at which the increase in false positive rate exceeded the increase in true positive rate. Since only three pigs and one sheep tested positive by real-time PCR, with none yielding culture-positive samples, a diagnostic threshold for iELISA could not be established for these livestock species. For this reason, pigs and sheep were excluded from iELISA analysis. A summary of RBT and iELISA test outcomes is provided by region in Table 1.

Prevalence estimates and diagnostic test performance

To estimate the overall prevalence of Brucella in cattle and goats throughout Cameroon, while accounting for the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the tests particular to the target population, data from the four tests were analyzed jointly at the country level. This analysis followed the methodology outlined in refs. 19,20. The baseline model19 assumes conditional independence of test results and was extended to a Bayesian context by imposing non-informative prior densities on prevalence and test sensitivities and specificities. The resulting Bayesian model permitted animals with positive real-time PCR or culture tests to be treated as true positives. The resulting posterior mean prevalence estimate for cattle was 8.3%, with a 95% credible interval (CI) of (6.5%, 10.0%). The estimated specificities of the four tests in cattle were 99.6% (RBT), 99.4% (iELISA), 99.9% (real-time PCR), and 99.9% (culture), while the sensitivities were 79.0% (RBT), 76.0% (iELISA), 23.0% (real-time PCR), and 11.0% (culture). For goats, the corresponding estimate for prevalence was 7.3% with a 95% CI of (4.1%, 11.0%). The estimated specificities of the four tests in goats were 99.8% (RBT), 97.6% (iELISA), 99.9% (real-time PCR), and 99.9% (culture), while the sensitivities were 35.0% (RBT), 67.0% (iELISA), 14.0% (real-time PCR), and 1.2% (culture).

Model diagnostics demonstrated conditional dependence between the molecular and serological tests. In cattle, the resulting estimates for prevalence, sensitivity and specificity of the tests under the dependence model (and 95% credible intervals) were as follows: Prevalence – 9.4% (6.0%–14.0%); Sensitivities – 69.0% (49.0%–88.0%, RBT), 65.0% (44.0%–85.0%, iELISA), 22.0% (12.0%–40.0%, real-time PCR), 10.0% (4.5%–20.0%, culture), and Specificities – 99.5% (98.4%–100%, RBT), 99.1% (98.2%–100%, iELISA), 99.9% (99.7%–100%, real-time PCR), 99.9% (99.7%–100%, culture). As expected, the random effects model increased uncertainty in the parameter estimates. However, the prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity estimates from the simpler conditional independence and conditional dependence models showed a high level of consistency.

Potential prevalence of B. melitensis in goats: Although no goats tested positive on culture, ten were real-time PCR positive for B. abortus and none for B. melitensis. Letting M denote the population proportion of goats that would test positive for B. melitensis given a positive PCR test, a one-sided confidence interval for M based on observing 0 B. melitensis outcomes out of 10 PCR positives is (0.0%, 25.8%). To estimate the potential prevalence of B. melitensis in goats in this study, we assume that M also describes the proportion B. melitensis among Brucella infected goats (irrespective of PCR positive result) and impose a non-informative Jeffreys’ prior on M. Using the posterior distribution on prevalence obtained from the conditional independence model and the posterior distribution on M based on 0 out of 10 B. melitensis findings in real-time PCR analysis, it follows that the posterior mean estimate of B. melitensis prevalence in goats is 0.3% with a 95% credible interval of (0.0%, 1.3%), indicating that it is possible this Brucella species could present somewhere in the country, but is most likely not endemic.

Discussion

Brucellosis has long been recognized as endemic across Africa, which is considered the region with the highest risk for contracting this disease5. Despite recognition, the full scope and magnitude of brucellosis remain poorly understood21. This study focused on Cameroon and was selected due to its strategic location along livestock trade routes connecting eastern, central, and western Africa, coupled with its porous borders and the large livestock population9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. These factors provided a unique opportunity to examine the regional dynamics of the disease. Although previous research has attempted to address knowledge gaps regarding brucellosis in Cameroon, they have primarily relied on serological methods or small sample sizes, preventing accurate identification of endemic Brucella species and reliable estimation of the disease burden9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

Like most African countries, animal traceability is mostly lacking, and the majority of farming practices are small-scale or transhumant, making it impractical to conduct prevalence studies directly at farms. As a result, slaughter facilities in key livestock trade regions and urban areas were selected as sampling sites, where animals congregate at established locations. At these sites, a random sample of animals from each species was collected to accurately estimate the disease prevalence in the respective regions. It is important to note that these animals showed no clinical signs of infection, as they had been examined by government veterinary inspectors before slaughter. Additionally, the individuals who brought the animals for slaughter were asked about the reasons for doing so. They typically reported selling the animals for cash to support their families, with no mention of disease concerns. Furthermore, the animals brought for slaughter were rarely pregnant or lactating (1.2% of all livestock). Therefore, submandibular lymph nodes were selected for sampling based on previous studies suggesting they are the organs most likely to yield Brucella isolates from naturally infected, non-pregnant, non-lactating livestock22. Brucella isolation in these lymph nodes also strongly correlates with superficial inguinal lymph nodes, the primary site of Brucella isolation in naturally infected, pregnant or lactating females22. Additionally, vaginal swabs were collected to detect potential active infections following recent abortions.

Culture results from submandibular lymph nodes of a sample comprising over 4600 cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs showed that B. abortus is the sole Brucella species endemic to the country, and it was detected across all sampled regions. While literature indicates that B. melitensis remains poorly understood in sub-Saharan Africa22, there is a prevalent misconception about it being endemic across the continent. Given that B. abortus is the sole endemic species detected in Cameroon, it should not be assumed that B. melitensis is endemic to the broader region or to Africa as a whole. Furthermore, isolates were exclusively cultured from cattle, while real-time PCR positive samples were also predominantly from cattle, followed by goats, pigs, and sheep, respectively (Table 1). This suggests that cattle are the primary livestock species responsible for the propagation of this disease in Cameroon, with other species being opportunistically infected. Moreover, several real-time PCR-positive results from lymph nodes were culture-negative, and all vaginal swabs were culture-negative, which could indicate chronic disease or latency. This further emphasizes that the sampling tissues required for effective detection of Brucella in cross-sectional prevalence studies assessing the overall infection burden are different from those used in investigations focused solely on active infections (e.g., vaginal swabs, spleen, placenta, and fetus)2,4.

For the diagnostic strategy, RBT was utilized as a screening tool due to the high sensitivity. To complement RBT, the indirect ELISA was selected due to its superior specificity compared to the serum agglutination test23. This choice was further supported by the fact that our ELISA assay underwent critical validation both in the U.S. and in local settings—an important step that is often overlooked24. Additionally, its ease of implementation in-country, relative to the complement fixation test, made it a more practical option for Cameroon. This approach to estimating prevalence was additionally guided by several considerations: (1) the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the serological assays used have not been previously established in Cameroon, (2) although culture is considered the gold standard for brucellosis diagnosis, its sensitivity is limited, as it requires the host to be bacteremic at the time of sampling, and (3) by employing four different diagnostic tests, we were able to apply Bayesian methods to estimate, not only prevalence, but also the sensitivity and specificity of each assay. This strategy allowed us to generate a more accurate and adjusted prevalence estimate.

To assess the seropositivity, the RBT and iELISA assays were used. These assays were selected based on their established ability to accurately detect true positives (sensitivity) and true negatives (specificity) in naturally infected, culture-positive livestock25. To ensure reliable results, these assays were validated and standardized locally, a step often overlooked in international diagnostic studies where assays from Europe are used in places like sub-Saharan Africa without adequate quality control measures, such as establishing region-specific cut-off values21. In cattle and goats, the two species for which iELISA cut-off values could be defined, a series testing strategy was employed to enhance specificity by reducing false positives. For pigs and sheep, where iELISA could not be used due to the absence of culture-positive animals and the low number of real-time PCR positive cases (3 and 1, respectively), seropositivity was determined using RBT results. While seropositivity is informative, it must be interpreted in conjunction with culture and real-time PCR findings, as serology cannot differentiate species but is a very valuable tool for screening purposes. Compared to previous research, the novelty of this study lies in the demonstration that the serological results align with culture and molecular findings, with cattle showing the highest positivity rate, followed by goats, pigs, and sheep (Table 1). Given that RBT and iELISA indirectly assess exposure to Brucella (through the detection of anti-Brucella antibodies), these serological results further reinforce the direct evidence from culture and real-time PCR (bacterial isolation and molecular characterization). This supports the conclusion that cattle are the primary livestock species responsible for transmitting the disease in Cameroon, with other species exposed due to the high prevalence in cattle.

When the regions of Cameroon were analyzed independently, although B. abortus-positive livestock were found across the country, the majority of Brucella culture, real-time PCR, and seropositive cattle were concentrated in the Far North (Table 1). These findings should be interpreted in light of previous studies, which suggest that cattle in this region are largely the result of unregulated international trade from eastern to western Africa, following an informal yet well-established supply chain that crosses multiple porous borders26. Specifically, the Far North region experiences significant cattle and small ruminant movement between Chad and Nigeria, with animals either passing through on their way to western Africa or entering Cameroon and migrating southward due to pastoral practices26. In contrast, the North region, while sharing borders with Chad, Nigeria, and the Central African Republic, experiences less international movement. The West region serves as a major international supply chain hub for animals traveling from Nigeria through the North-West and South-West regions, then throughout the country26.

Given the unregulated movement of livestock, the genomic results from this study suggest that the endemic B. abortus strain in Cameroon may originate from the Sudanese region of eastern sub-Saharan Africa, as the B. abortus genotypes from most samples were closely related to two strains from Sudan, isolated in 1987 and 2005. These isolates are all part of the Tulya clade, named after an isolate from Meyer & Morgan, 197327. This indicates widespread infection with African endemic strains in Cameroon28, consistent with previous findings of African endemic B. abortus strains from West and East Africa29,30. Additionally, due to the highly bustling international trade routes and porous borders, the six neighboring countries likely have similar patterns. Future research should include these countries to provide a more comprehensive assessment of this region of Africa. In contrast, the two samples, BN008 and BO063, (cattle from the North and West regions) which were closely related to the reference strain, are most likely S19 vaccine strains, further supporting the idea of international movement of animals, as Cameroon does not have an authorized national vaccination program for brucellosis nor does it produce them, whereas S19 has been produced in Nigeria.

In Cameroon, B. abortus is the only Brucella species endemic to the country, with cattle being the primary species affected. Other livestock species are likely infected or exposed due to species co-mingling, suggesting that goats and sheep are not the primary sources of infection. Conversely, the role of pigs in brucellosis transmission requires further investigation. Although, due to a lack of reagents and standardized methods, a deeper understanding of the disease in pigs is currently limited. However, at this point, B. suis has not been identified in this region of Africa. In Cameroon, people predominantly consume cow’s milk rather than milk from small ruminants. Considering that handling infected animals and consuming raw dairy products are key contributors to human brucellosis, future research should focus on farmers, dairy consumers, and the distribution of dairy products to the general public. Moreover, control strategies should target the cattle supply chain nationwide. Given the porous borders and unregulated trade, the epidemiological situation in neighboring countries is likely similar. Therefore, control strategies should possibly incorporate an international approach. It is expected that these findings will serve as a foundation for developing effective surveillance and control policies, improving both animal and public health in the future. Additionally, this study will contribute valuable insights to address knowledge gaps and enhance understanding of brucellosis, not only in Cameroon but across Africa as a whole.

Limitations

While this study provides critical insights into the prevalence and molecular characterization of B. abortus in Cameroon, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design and reliance on slaughterhouse sampling may not fully capture the epidemiological dynamics of brucellosis in the broader livestock population, particularly in remote or subsistence farming communities. The absence of a national livestock traceability system further constrained our ability to determine the geographic origin and movement history of sampled animals, limiting inferences about transmission pathways and regional disease burden. Additionally, although multiple diagnostic techniques were employed (i.e., culture, real-time PCR, RBT, and iELISA), each has inherent limitations in sensitivity and specificity. Culture, considered the gold standard, demonstrated low sensitivity due to the requirement for bacteremia at the time of sampling. Real-time PCR, while more sensitive, may detect DNA from non-viable organisms, complicating interpretation in the context of active infection. Additionally, iELISA cut-off values were only validated for cattle and goats, excluding pigs and sheep from more specific serological analysis due to the lack of culture-positive samples and limited PCR positivity. Furthermore, while NGS provided valuable phylogenetic insights, the metagenomic nature of the data and the limited number of sequenced isolates may not fully represent the genetic diversity of B. abortus circulating in Cameroon or neighboring countries. Finally, the study focused exclusively on animal hosts and did not assess human exposure or infection, despite the zoonotic nature of brucellosis. Future research should incorporate human serosurveys and risk assessments to better understand the public health implications of endemic B. abortus in Cameroon.

Methods

Sampling strategy

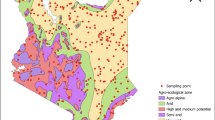

This study was conducted at abattoirs in Maroua, Yagoua, and Kousseri (Far North region), Garoua and Touboro (North region), and Bafoussam and Dschang (West region; see Fig. 2). Abattoirs were selected as sampling sites due to the lack of a traceability system for livestock and cold chain infrastructure for meat in Cameroon. These facilities are rudimentary, open-air setups situated adjacent to local meat markets. They are commonly used for slaughtering livestock, either purchased at live markets or brought directly from farms, primarily because of their proximity to the markets and the absence of refrigerated transport. While slaughtering may also occur at individual households for personal consumption, it is important to emphasize that reliable refrigeration for meat transport is not available. Specific sampling sites were selected based on characteristics including the 1) type of livestock production system, 2) international trade and movement, and 3) population numbers. Specifically, the Far North region was selected based on its shared borders with Chad and Nigeria (Fig. 2) and substantial cattle and small ruminant transhumance activity between the three countries26. Similarly, the North region shares borders with Chad and Nigeria, but also borders the Central African Republic (Fig. 2). Finally, the West region does not share a national border (Fig. 2) but is a supply chain hub for animals traveling from Nigeria through the North West and South West regions and then throughout the country26.

Adult male and female cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs were included in this study due to their economic significance to the country and their susceptibility to the three zoonotic Brucella species. Serum and submandibular lymph nodes were collected from all animals. In addition, a vaginal swab was collected from all females. Tissue selection was based on well-known target organs for Brucella colonization in naturally infected asymptomatic animals to increase the chance of detection22.

The sample size for each livestock species within each study region was determined based on the sparse historical literature originating from Cameroon describing seroprevalences, indicating a likely estimate of 4.0%9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. With a desired precision of ± 2.0% and a 95% confidence interval (CI), 369 animals of each target species from each region were required to achieve the desired study power, resulting in a total of 1107 of each animal species countrywide.

Between February 2021 and May 2023, animals were randomly chosen for sample collection from the livestock brought to each abattoir that day for slaughter. Animal sex was not taken into consideration during the selection process. Following collection, samples were temporarily stored at −20 °C before being transferred to the National Veterinary Laboratory (LANAVET) in Yaoundé for laboratory analysis (Fig. 2). Submandibular lymph nodes collected from each animal were analyzed by bacterial culture and real-time PCR, and isolates were assessed by next-generation sequencing. Serum samples were subjected to the indirect ELISA and Rose-Bengal Tests (RBT).

Bacterial culture and isolation

For bacteriological culture, the entire lymph node was homogenized in 1 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) using an OMNI Tissue Homogenizer and 7 mm hard tissue OMNI TIP plastic homogenizing probes (OMNI International). After homogenization, 200 µL of each sample was spread onto two Farrell’s agar plates. Additionally, vaginal swabs were spread separately onto two Farrell’s agar. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 3–5 days, and bacterial growth was monitored for up to 10 days. Colonies consistent with Brucella spp. phenotypes were then purified by subculture onto Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) and their identity was confirmed by real-time PCR using the methods detailed below.

DNA extraction

A quick lysis preparation for genomic DNA was performed on all bacterial colonies exhibiting Brucella spp. phenotype and growth by collecting a small portion of the colony using a sterile inoculation loop and mixing thoroughly in 50 μL of DNase-free sterile water. The suspensions were heated in a dry bath at 95 °C for 10 min. Genomic DNA from the submandibular lymph node was extracted from every animal, regardless of serological and/or bacteriological status, using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genomic DNA from confirmed Brucella isolates was extracted using Qiagen’s mericon DNA Bacteria Plus Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Molecular analysis

DNA samples extracted from tissues and isolates were analyzed via real-time PCR. Initially, the IS711 insertion sequence was amplified. Upon confirmation of the genus, Brucella species was subsequently identified using species-specific real-time PCR primers (Table 2)31. Briefly, the reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl containing 5 μl of DNA, 12.5 μl of TaqMan Universal Master Mix No AmpErase UNG (Life Technologies), 6.9 μl of DNase-free water, 0.2 μl of each 20 μM forward and reverse primers (Sigma Aldrich), and 0.2 μL of 20 μM FAM Probe (Sigma Aldrich) (Table 2). Real-time PCR was performed using a CFX96 System (BIO-RAD) with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 45 amplification cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and a final elongation of 1 min at 60 °C for IS711 target and 62 °C for species-specific real-time PCR. Genomic DNA from B. abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis were included as positive controls, and DNA-free sterile water as a negative control. Results are reported as Cq values. Samples were considered positive if the Cq value was ≤40. The cut-off value was determined utilizing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using culture and PCR positive samples as True Positive (TP) and samples negative by culture, PCR, and RBT as True Negative (TN).

Next-generation sequencing

The complete sequencing of all Brucella-positive DNA was conducted at the Agricultural Research Council’s Biotechnology Platform (ARC-BTP) in South Africa. The sequencing process followed the MGIEasy protocol (MGI, China). In summary, DNA samples were mechanically fragmented using the E220 Focused-ultrasonicator, generating DNA fragments between 350 and 500 bp, which were subsequently selected and purified using MGIEasy DNA Clean beads. The DNA fragments then underwent end-repair and dATP tailing (ERAT) with the appropriate buffer and enzyme mix, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, to facilitate the ligation of MGIEasy DNA adapters.

Following adapter ligation, the DNA products were cleaned, and each sample underwent seven cycles of PCR amplification using a Bio-Rad thermocycler. The amplified products were purified using magnetic beads and assessed for fragment size distribution with the dsDNA fluorescence kit. The amplicons were then denatured and subjected to single-stranded circularization. Any uncirculated or linear DNA strands were digested with an exonuclease, resulting in a single-stranded circular DNA library.

DNA nanobeads (DNBs) were generated using rolling circle amplification (RCA) technology. The MGIEasy circularization kit (MGI, China) was used for circularized DNA, while the DNBSEQ-G400RS high-throughput sequencing kit (MGI, China) was used for DNBs. Finally, the DNA nanobeads were loaded onto a sequencing chip for PE150 sequencing on the DNBSEQ-G400 (MGI, China).

Synthesis-by-sequencing was carried out on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. The pooled libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq. Read quality was assessed using FastQC v0.11.9 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) and reads containing adapter sequence or low-quality data were trimmed with trimmomatic v0.3932. Samples without adequate coverage for phylogenetic placement were removed from the analyses.

Metagenome sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

High-quality whole genome assemblies representing the diversity of B. abortus were downloaded from the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-ARC), which hosts a large collection of Brucella genomes33. In parallel, sequence read archive (SRA) data34 were downloaded for all available B. abortus genomes that are phylogenetically related to other isolates from Africa based on results from Janke et al., 202328. An orthologous single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) matrix was constructed that included sequences from the assemblies, the SRA data, and the isolates collected and sequenced for this study using the Northern Arizona SNP Pipeline35. Briefly, NASP is a pipeline that aligns genomes to a selected reference, runs SNP discovery, and generates a matrix that contains only polymorphic high-quality loci. For the raw sequence data to be considered high quality, any given site must have 10X coverage, and 90% of the base calls at each SNP position must agree. The final matrix contained 9721 SNPs. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Parsimony (MP) method. Tree 1 out of the 7 most parsimonious trees (length = 9834) is shown. The consistency index was 0.989 (0.981), retention index was 0.998 (0.998), and composite index was 0.988 (0.979) for all sites and parsimony-informative sites (in parentheses). The percentage of parsimonious trees in which the associated taxa clustered together are shown next to the branches. The MP tree was obtained using the Subtree-Pruning-Regrafting (SPR) algorithm36 with search level 1 in which the initial trees were obtained by the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA1237 using up to 7 parallel computing threads and 1000 bootstrap replicates to determine branch support.

Rose Bengal Test (RBT)

Detection of antibodies against smooth strains of Brucella in all serum samples was performed using the Rose Bengal Test (RBT) per the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) Terrestrial Manual2. Specifically, 30 µL of antigen was placed on a diagnostic card, and the same volume of serum was placed beside the antigen. Serum and antigen were mixed thoroughly using a wooden stirrer, and the plate was rocked by hand for 4 min. Agglutination was read immediately, and any visible agglutination was recorded as a positive reaction, while the absence of agglutination was recorded as a negative. A positive and negative control (12-H and 12-N, respectively, U.S. National Veterinary Services Laboratories) were used on each plate.

Indirect Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (iELISA)

Serum samples were analyzed for the presence of antibodies against smooth strains of Brucella using an in-house iELISA. The assay was developed and validated in the United States and then validated at LANAVET using local conditions and samples before employment. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 2.5 µg/well of heat-killed B. abortus S19 lysate in coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The following day, plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked with 100 µL of 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS at 37 °C for 2 h. After three washes, sera diluted at 1:1000 for cattle and 1:500 for goats were added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. Plates were washed three times, and anti-bovine IgG coupled to HRP (for bovine and goat sera, respectively) (1:1,000; LGC Clinical Diagnostics, Sera Care) were added to appropriate wells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, o-Phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) peroxidase substrate was added (100 µL/well) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Ledetect 96). A cut-off value was determined utilizing an ROC curve using the culture and real-time PCR positive samples as TP and samples negative by culture, real-time PCR, and RBT as TN. All tests were performed in triplicate, with results presented as mean absorbance values for the three wells. An average absorbance ≥ threshold was recorded as a positive reaction, while absorbance < threshold was recorded as a negative.

Prevalence analysis

The prevalence of Brucella in cattle and goats was assessed using Bayesian models with latent disease indicators and likelihood functions19,20, applying priors for sensitivities, specificities, prevalence, and random effect variance and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for posterior inference. The conditional independence model19 was applied to the outcomes for both cattle and goats, resulting in estimates of sensitivities and specificities as indicated in the main article. In these analyses, animals that tested positive by real-time PCR were considered true positives (all culture-positive animals were also real-time PCR positive). However, model diagnostics indicated that the conditional independence assumption between tests was not valid due to the high likelihood that culture-positive animals were also real-time PCR-positive, and real-time PCR-positive animals were also RBT and iELISA positive. In cattle, four diagnostic tests were performed for each individual—RBT, iELISA, real-time PCR, and culture—enabling the application of the random effects model proposed by Qu et al. 20 to account for dependence among test results. The model classifies subjects into latent disease states (e.g., infected vs. uninfected), treats test outcomes as binary variables (positive/negative), and incorporates a random effect to capture residual correlation among tests beyond what is explained by the latent disease status. In contrast, for goats, only three tests were informative (with all culture tests negative), so the conditional dependence model could not be applied, as four test results are required for identifiability in this model. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R Core Team, 2025)

Ethical compliance

The Texas A&M University (TAMU), Offices of Research Compliance and Biosafety, Animal Welfare Office, and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) evaluated the need for an animal use protocol (AUP). As no manipulation of live animals was performed for the purpose of this study, and animals were not euthanized specifically for the purposes of this research, no AUP was required. LANAVET Cameroon deferred to the TAMU IACUC.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Diagnostic data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and source data file. The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in NCBI’s GenBank in BioProject PRJNA1346423. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Franc, K. A., Krecek, R. C., Hasler, B. N. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health 18, 125 (2018).

WOAH. Brucellosis (Brucella abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis). In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. (ed. WOAH) 355–398, 8 ed: (World Organization for Animal Health, 2018).

Corbel, M. J. Brucellosis in humans and animals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; (2006).

Poester, F. P., Samartino, L. E. & Santos, R. L. Pathogenesis and pathobiology of brucellosis in livestock. Rev. Sci. Tech. 32, 105–115 (2013).

Laine, C. G., Johnson, V., Scott, H. M. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. Global Estimate of Human Brucellosis Incidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 29, 1789–1797 (2023).

Dean, A. S. et al. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1929 (2012).

WOAH. World Animal Health Information System. In: WOAH, editor. (2021).

Akakpo, A. J., Têko-Agbo, A. & Koné, P. (eds). The Impact of Brucellosis on the Economy and Public Health in Africa. In Proc. Conference of the OIE Regional Commission for Africa, Paris, France, 85–98 (2009).

Laine, C. G., Wade, A., Scott, H. M., Krecek, R. C. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Scoping review of brucellosis in Cameroon: Where do we stand, and where are we going? PLoS One 15, e0239854 (2020).

Laine, C. G., Scott, H. M. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Human brucellosis: Widespread information deficiency hinders an understanding of global disease frequency. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010404 (2022).

Shey-Njila, O. et al. Serological Survey of Bovine Brucellosis in Cameroon. Rev. Élev Méd vét Pays trop. 58, 139–143 (2005).

Bayemi, P. H., Webb, E. C., Nsongka, M. V., Unger, H. & Njakoi, H. Prevalence of Brucella abortus antibodies in serum of Holstein cattle in Cameroon. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 41, 141–144 (2009).

Scolamacchia, F. et al. Serological patterns of brucellosis, leptospirosis and Q fever in Bos indicus cattle in Cameroon. PLoS One 5, e8623 (2010).

Bayemi, P. H. et al. Bovine Brucellosis in Cattle Production Systems in the Western Highlands of Cameroon. Int. J. Anim. Biol. 1, 38–44 (2015).

Kong, A. T., Nsongka, M. V., Itoe, S. M., Hako, A. T. & Leinyuy, I. Seroprevalence of Brucella abortus in the Bamenda Municipal Abattoir of the Western Highlands, of Cameroon. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 6, 245–251 (2016).

Ojong, B., Macleod, E., Ndip, M. L., Zuliani, A. & Piasentier, E. Brucellosis in Cameroon: Seroprevalence and risk factors in beef-type cattle. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 53, 64 (2016).

Awah-Ndukum, J. et al. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Brucellosis among Indigenous Cattle in the Adamawa and North Regions of Cameroon. Vet. Med. Int. 2018, 1–10 (2018).

Awah-Ndukum, J. et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of brucellosis among slaughtered indigenous cattle, abattoir personnel and pregnant women in Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 18, 1–13 (2018).

Hui, S. L. & Walter, S. D. Estimating the error rates of diagnostic tests. Biometrics 36, 167–171 (1980).

Qu, Y., Tan, M. & Kutner, M. H. Random effects models in latent class analysis for evaluating accuracy of diagnostic tests. Biometrics 52, 797–810 (1996).

Ducrotoy, M. et al. Brucellosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current challenges for management, diagnosis and control. Acta Trop. 165, 179–193 (2017).

Corner, L. A., Alton, G. G. & Iyer, H. Distribution of Brucella abortus in infected cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 64, 241–244 (1987).

Godfroid, J., Nielsen, K. & Saegerman, C. Diagnosis of brucellosis in livestock and wildlife. Croat. Med J. 51, 296–305 (2010).

Vection, S., Laine, C. G. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. What do we really know about brucellosis diagnosis in livestock worldwide? A systematic review. Plos Neglect Trop D. 19, 1–21 (2025).

O’Grady, D. et al. A comparative assessment of culture and serology in the diagnosis of brucellosis in dairy cattle. Vet. J. 199, 370–375 (2014).

Motta, P. et al. Implications of the cattle trade network in Cameroon for regional disease prevention and control. Sci. Rep. 7, 43932 (2017).

Meyer, M. E. & Morgan, W. J. B. Designation of neotype strains and of biotype reference strains for species of the genus Brucella Meyer and Shaw. Int. J. Syst. Evolut. Microbiol. 23, 135–141 (1973).

Janke, N. R. et al. Global genomic diversity of Brucella abortus: spread of a dominant lineage. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1–13 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Original and introduced lineages co-driving the persistence of Brucella abortus circulating in West Africa. Front Public Health 11, 1106361 (2023).

Janke, N. R. et al. Global phylogenomic diversity of Brucella abortus: spread of a dominant lineage. Front Microbiol 14, 1287046 (2023).

Hinic, V. et al. Novel identification and differentiation of Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae suitable for both conventional and real-time PCR systems. J. Microbiol Methods 75, 375–378 (2008).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Olson, R. D. et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D678–D689 (2023).

Leinonen, R., Sugawara, H. & Shumway, M. International Nucleotide Sequence Database C. The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res 39, D19–D21 (2011).

Sahl, J. W. et al. NASP: an accurate, rapid method for the identification of SNPs in WGS datasets that supports flexible input and output formats. Microbial Genomics 2, 1–12 (2016).

Nei, M. & Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; (2000).

Kumar, S. et al. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol Biol Evol. 41, 1–9 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The project or effort depicted was or is sponsored by the Department of the Defense, Defense Threat Reduction Agency. The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the United States federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. Statement per contract. Contract #HDTRA11910032 awarded to AMA-G. We acknowledge the assistance of Microsoft Copilot, powered by GPT-4, for providing basic word processing support (i.e., checking grammar and identifying improvements in writing style) in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K.G.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft; C.G.L.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft; P.G.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; C.O.G.D.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; H.A.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; D.P.D.: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing; W.M.: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing; D.G.-G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing; S.V.: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing; J.D.G.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing; M.K.: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing; V.E.J.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing; J.T.F.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing; A.W.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing; A.M.A.-G.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhiguo Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guela, G.K., Laine, C.G., Gontao, P. et al. Prevalence study in Cameroon identifies Brucella abortus as the endemic Brucella species in livestock. Nat Commun 16, 11600 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66515-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66515-z