Abstract

Optimal transport theory, originally developed in the 18th century for civil engineering, has since become a powerful optimization framework across disciplines, from generative AI to cell biology. In physics, it has recently been shown to set fundamental bounds on thermodynamic dissipation in finite-time processes. This extends beyond the conventional second law, which guarantees zero dissipation only in the quasi-static limit and cannot characterize the inevitable dissipation in finite-time processes. Here, we experimentally realize thermodynamically optimal transport using optically trapped microparticles, achieving minimal dissipation within a finite time. As an application to information processing, we implement the optimal finite-time protocol for information erasure, confirming that the excess dissipation beyond the Landauer bound is exactly determined by the Wasserstein distance — a fundamental geometric quantity in optimal transport theory. Furthermore, our experiment achieves the bound governing the trade-off between speed, dissipation, and accuracy in information erasure. To enable precise control of microparticles, we develop scanning optical tweezers capable of generating arbitrary potential profiles. These results provide guiding principles for information processing with saturating the trade-off.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consider the problem of transporting a pile of sand to another location (Fig. 1a). In 1781, Gaspard Monge posed a deceptively simple yet fundamental question1: Given the initial and final shapes of the sand piles and the cost of transporting each grain between any two positions, what is the most efficient way to minimize the total cost? This question in engineering laid the foundation for optimal transport theory, which was later formalized in applied mathematics through the incorporation of probability theory. A central concept in this framework is the Wasserstein distance, which quantifies the difference between two probability distributions in terms of the minimal transportation cost required to transform one into the other2,3. In recent years, optimal transport theory has found applications across various disciplines, including thermodynamics4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Notably, it has been shown to establish fundamental bounds on finite-time dissipation (Fig. 1b, c), where the Wasserstein distance exactly characterizes the minimal dissipation in such processes.

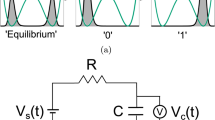

a Transport of a sand pile in one dimension. Optimal transport is a transport protocol that minimizes the cost of transport. When the cost is defined based on the transport distance, the optimal transport of moving a sand pile in one dimension is achieved when the positional order is maintained so that the sand grains at the leftmost location are transported to the leftmost location, and so on. b Stochastic thermodynamics describes the thermodynamics in thermal fluctuating systems12 -- 14. We think of transporting a probability distribution pi(x) to pf(x) within the time duration τ. Exemplified transport processes are shown on the right, which are the targets of this paper. c Geometric space with the Wasserstein distance (left). With the optimal transport in one-dimensional systems, each segment in the distribution is linearly transported without changing the positional order (right). d We experimentally implement the optimal transport by using a microscopic particle with a diameter of 0.5 μm trapped by a potential with a dynamically changing profile. We developed scanning optical tweezers that generate an arbitrary potential profile under the constraints determined by the device (see SI Section S1). Right: examples of transport. Distribution of the particle positions (color) and potentials reconstructed from the experiments (solid curves).

Let us start with a simple scenario in which a microparticle is immersed in a thermal environment (heat bath) at temperature T. Due to thermal fluctuations, the particle undergoes stochastic motion, with its state described by a time-dependent probability distribution, denoted as pt(x). Here, t represents time, and x is the particle’s position. Optimal transport theory provides a natural framework for optimizing the evolution of these probability distributions. Such stochastic thermodynamic systems form the foundation of modern thermodynamics—often referred to as stochastic thermodynamics—which applies not only to a microparticle but also to a wide range of experimental systems, including electric circuits and molecular motors12,13,14.

The second law of thermodynamics states that the thermodynamic work W must always be greater than or equal to the nonequilibrium free-energy change ΔF15, which implies that the dissipated work, defined as wd ≡ W − ΔF, satisfies wd ≥ 0. This thermodynamic dissipation, which is equivalent to the entropy production multiplied by T, vanishes only in the quasi-static limit requiring an infinitely long operation time. In finite-time processes, however, wd remains strictly positive due to unavoidable dissipation16. Assume a transport of a system described by an overdamped Langevin equation from an initial state pi(x) to a final state pf(x) within a finite-time duration τ. Optimal transport theory refines the second law by providing a universal bound on finite-time dissipation:

where the equality is achievable for any given duration τ7,10. Here, \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{{{\rm{i}}}},{p}_{{{\rm{f}}}})\ge 0\) represents the Wasserstein distance, which is determined solely by pi(x) and pf(x) and does not depend on τ (see “Wasserstein distance and transport protocols” section in Methods). \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{{{\rm{i}}}},{p}_{{{\rm{f}}}})\) quantifies the distance between the distributions pi(x) and pf(x) in terms of the cost of the transport task between them. Intuitively, \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{{{\rm{i}}}},{p}_{{{\rm{f}}}})\) linearly scales with the traveling distance. γ is the particle’s friction coefficient. A key feature of \({w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) is its inverse proportionality to τ: the greater the speed ∝ 1/τ is (i.e., the shorter the operation time τ is), the greater the additional dissipation is. In terms of geometry, the thermodynamically optimal transport that minimizes dissipation is realized by transport along a geodesic connecting pi and pf with a uniform velocity, as illustrated in Fig. 1c (left)2,3.

A particularly important application of the second law of thermodynamics is in determining the fundamental energy cost of information processing15. For example, the Landauer bound7,17,18,19,20,21 states that erasing one bit of information from a binary symmetric memory requires a minimum work of \(W={k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T\ln 2\), where kB is the Boltzmann constant. This minimum equals the free-energy change ΔF between the initial symmetric double-peak distribution corresponding to 0 and 1 states and the final single-peak distribution corresponding to the 0 state (Fig. 1b). The Landauer bound itself, in the limit τ → ∞, was experimentally demonstrated in 2012 using optically trapped microparticles22, and various other experiments on the thermodynamics of information23,24,25,26,27, including implementations of Maxwell’s demons have been conducted28,29. It is then desirable to establish an achievable bound for finite-time processes. This can be addressed using optimal transport theory7: applying Eq. (1) to information erasure, where \({w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}=W-{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T\ln 2\), yields

The finite-time correction on the right-hand side vanishes in the limit τ → ∞, recovering the original Landauer principle17.

In this study, we experimentally realize thermodynamically optimal transport that minimize thermodynamic dissipation. Our experimental platform consists of a Brownian microparticle confined in a dynamically controlled potential, serving as a prototypical thermodynamic system (Fig. 1d; see also Fig. S1). To achieve the precise control required for optimizing distribution dynamics, we built a custom optical tweezer system capable of generating arbitrary potential profiles (within the constraints of the device) through precisely engineered laser scanning patterns (see Methods). The method is general and can be applied to a wide range of systems, including feedback control and simultaneous manipulation of multiple Brownian particles.

We first investigate a simple transport problem: the translation and compression of a Gaussian distribution. This scenario, due to its simplicity and experimental feasibility, provides a clear demonstration of optimal transport by allowing direct comparisons between optimal and non-optimal protocols. In particular, our experiment reveals the geometric structure of the optimal transport by experimentally achieving the geometrical lower bound of the dissipated work. Specifically, the realized optimal transport corresponds to uniform-speed motion along a geodesic in the space of probability distributions, which is equipped with the Wasserstein metric. Furthermore, we demonstrate that optimal transport theory provides a method to evaluate dissipated work, even for non-optimal protocols based solely on the distribution dynamics.

Then, we perform the experiment on information erasure, which is the primary focus of this paper. To implement the optimal information erasure, we dynamically vary the potential profile from an initial double-well configuration to a final single-well one. This setup has been numerically studied in overdamped systems7,20,21, suggesting a significant reduction in dissipation with full potential control by optimal transport20. Our experiment reaches the theoretical bound given by Eq. (2), namely the optimal finite-time correction to the conventional Landauer bound, expressed by the Wasserstein distance, within experimental errors.

Another crucial aspect of information processing is accuracy. Typically, increasing speed increases dissipation (and thus energetic cost) and reduces accuracy11,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Such trade-offs between energy cost, speed (i.e., 1/τ), and accuracy are commonly observed in biological systems, including sensory adaptation32 and information replication30,31. In our study, using the model experimental platform, we achieve the fundamental bound of this trade-off by implementing optimal information-erasure protocols with several different values of accuracy. This demonstration reinforces the universality of such trade-off in thermodynamic information processing.

Results

We begin by implementing a translation and compression protocol—a simple yet highly controllable process — to experimentally characterize optimal transport. Next, we realize the optimal transport for information erasure, marking the first experimental demonstration of finite-time thermodynamically optimal information processing. To accurately measure probability distributions and quantify physical quantities such as work, we perform extensive repetitions of each protocol, typically exceeding 12,000 repetitions, involving at least three different particles per condition (see Methods).

Optimal translation-compression transport in finite time

Let pi and pf be Gaussian distributions with different means μ and standard deviations d. The Gaussian dynamics enable a detailed quantitative analysis of the transport process. Here, we transport a particle over a mean distance of μf − μi = 300 nm while compressing the distribution with the ratio of di/df = 2, corresponding to the free-energy difference of \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T\ln 2\simeq 0.693\,{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T\). To characterize optimal transport, we implement three distinct protocols: optimal, naive, and gearshift.

We first constructed the optimal protocol for given pi and pf (Fig. 2a–d). If pi and pf are both Gaussian, the intermediate distributions under the optimal transport protocol are always Gaussian, with linearly varying μ and d10. pi and pf are chosen to be the same as the following naive protocol. The dynamics of potential Vt(x) realizing the transport are obtained by numerically solving the Fokker-Planck equation (see SI Section S2.2), which is directly implemented in our experiment. Vt(x) is always harmonic and has a discrete forward jump of the parameters at t = 0 and a backward jump at t = τ (Fig. 2a–c). The first jump compensates for the delay due to viscous relaxation, and the last jump quenches the dynamics to the final target distribution.

Time evolution of probability distributions and potentials (a), mean μ (b), and width d (c). The optimal protocol varies the potential profile so that μt and dt linearly vary. The naive protocol linearly varies the position and stiffness of the potential. The gearshift protocol combines two optimal protocols with different durations (fractions are 2/3 and 1/3) and speeds (ratio of 1 to 4). a Experimentally obtained distributions with Gaussian fittings and potentials for τ = 50 ms. Open and closed circles indicate the centers of distribution and potential, respectively. The dotted curves in optimal and gearshift protocols are the potentials before the jumps of the potential position. d Trajectories in the (μ, d) space, which implements the Wasserstein distance for Gaussian dynamics, for the same data in (a–c). The optimal protocol is characterized by a uniform-speed transport on a geodesic (gray straight line) connecting the initial and final distributions. e The work W vs the protocol speed 1/τ. W was calculated based on Eq. (7). Gray closed symbol corresponds to an experimental run consisting of more than 3000 repetitions for τ ≤ 200 ms and 1500 repetitions for τ = 500 ms for a particle. We performed four runs with four independent particles under each condition to measure the mean values (colored open symbols). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (s.e.m., four samples). The black open circle indicates the mean values of ΔF calculated from the initial and final distributions. The blue solid line indicates the theoretical minimum evaluated using the mean ΔF (0.680 ± 0.007, mean ± s.e.m. of all data of all protocols, 48 samples) as the intercept and the mean of \(\tau {w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) with \({w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) calculated by Eq. (1) as the slope. Some runs show W values lower than this average theoretical minimum (also in Figs. 3d and 4), since the minimum \(\Delta F+{w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) differs from particle to particle even in the same condition due to the particle-dependent variation in γ (Fig. S12). We confirmed that each run satisfies the bound except for a few outliers due to statistical errors (Fig. S13). The colored thin solid lines connect experimental data of naive and gearshift protocols, which are extrapolated to the circle by dotted lines. f Evaluation of wd from distributions without knowing individual trajectories (Eq. (4)). A typical example of gearshift protocol is shown. Inset: schematic of the segmentation. g Comparison of evaluation of wd from recovered potentials (Eq. (7)) and from distributions (Eq. (4)). See SI Section S5 for comparison in more detail.

Transport can be geometrically characterized in the distribution space. We observed that the designed optimal protocol realizes the linear translation of the distribution in both μ and d (Fig. 2a–c). Accordingly, we obtained a linear uniform-velocity trajectory in the (μ, d) space (Fig. 2d), where the Euclidean distance is equal to the Wasserstein distance for Gaussian distributions3. The uniform-velocity transport on a geodesic in the distribution space indicates the optimal transport2,10.

The naive protocol was implemented as a reference, where the position and stiffness of a harmonic potential are linearly varied. The particle followed the potential with a time delay owing to viscous relaxation. Therefore, the final position and width of the distribution at t = τ do not reach the equilibrium values for the potential at t = τ. The trajectory in the (μ, d) space significantly deviated from that of the optimal protocol (Fig. 2d).

As a further reference, we also attempted a gearshift protocol, which connects two optimal protocols with different durations and speeds. This protocol realized a transport on the geodesic similarly to the optimal protocol but with a non-uniform speed (Fig. 2d). In this sense, the protocol is not optimal as a whole.

Work

The work W and free-energy change ΔF for transport are evaluated by using the potential Vt, recovered from the experimental trajectories (see Methods), and the distribution pt (Fig. 2e). The optimal protocol achieves the theoretical minimum for finite-time processes given by Eq. (1) within error bars. Accordingly, the energy-speed trade-off wd ∝ 1/τ was observed. ΔF was 0.680 ± 0.007 kBT (mean ± s.e.m. of all data, 48 samples). This corresponds to the compression ratio of \(\exp (\Delta F/{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T)=1.97\), which is close to the designed value of 2. On the other hand, the naive protocol has larger wd and has a slightly nonlinear dependence on 1/τ; this implies that the transport is in the nonlinear-response regime. For a systematic comparison, we also constructed intermediate protocols by linearly interpolating optimal and naive protocols (Fig. S6).

The 1/τ dependence is also observed with the gearshift protocol. This is because the trajectories in the (μ, d) space are similar for different τ. However, W did not reach the theoretical minimum, indicating that wd ∝ 1/τ alone does not necessarily indicate optimal transport.

Evaluation of dissipated work without knowing the potential

The work corresponds to the energy change resulting from the change in the shape of Vt(x) 14. Therefore, it is straightforward to use Vt(x) to calculate dissipated work wd based on Eq. (7) in Methods as practiced above. However, the potential-based “naïve” method uses the drift, that is, the average of the displacement between two successive video frames, to estimate the potential profiles. This essentially requires the trajectories and is not always feasible in experiments, especially if treating complex systems such as biological systems by e.g. pump-probe techniques38,39. In contrast, the optimal transport theory allows the calculation of wd only from the snapshot distributions pt(x) during the process (in the absence of non-conservative force), without using information about the potential profile Vt(x)10. This method does not require individual trajectories, and furthermore, is applicable regardless of whether the process is optimal or not (see Methods).

Consider dividing pt(x) into N short transport segments with time duration [ti, ti+1] (i = 1, 2, …, N) (Fig. 2f, inset). The dissipated work during i-th segment, denoted as wi, is bound by the minimum dissipated work realized by the optimal transport in that segment with the initial distribution \({p}_{{t}_{i}}(x)\) and final distribution \({p}_{{t}_{i+1}}(x)\) as

By taking the summation over i, we obtain \({w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{w}_{i}\ge {\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{w}_{i}^{\min }\). In the limit of ti+1 − ti → 0, we expect that wi converges to \({w}_{i}^{\min }\) since \({p}_{{t}_{i}}(x)\simeq {p}_{{t}_{i+1}}(x)\) if we consider a one-dimensional Euclidean space where non-conservative forces do not exist10. That is, a transport, which is not necessarily optimal, can be considered as a series of short optimal transports. Hence,

Equations (3) and (4) enable us to calculate wd ( ≡ W − ΔF) from pt(x) via Wasserstein distance. \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{{t}_{i}},{p}_{{t}_{i+1}})\) can be calculated in the same way as \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{{{\rm{i}}}},{p}_{{{\rm{f}}}})\) through Eq. (6).

We found that wd computed by this method converges to the value computed using Vt(x) at large N, validating the methodology (Fig. 2f, g). The number of segments N needed for convergence is determined by the curvature and uniformity of the velocity of the whole transport trajectory in the distribution space. See SI Section S5 for further validation of the method.

For the one-dimensional Gaussian dynamics, the distribution space can be represented by a space parameterized only by μ and d, which simplifies our evaluation method (Fig. 2f). In general, however, this method only assumes the absence of non-conservative forces10, and therefore is applicable to more general situations. We will see an application for information erasure later.

Optimal information erasure in finite time

We now turn to the experiment on optimizing information erasure in finite time. Specifically, we consider a situation where one bit of information is encoded in a symmetric double-peak distribution, with logical state 0 assigned to x < 0 and 1 assigned to x ≥ 0 (Fig. 3). The information erasure process transforms the double-peak distribution into a single-peak distribution corresponding to a fixed logical state. Without loss of generality, we focus on resetting to logical state 0, as the symmetric double-peak ensures the symmetry between 0 and 1.

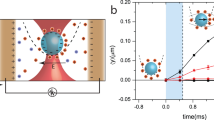

a Kymograph of the probability distributions constructed from 5585 repetitions of information erasure with exemplified trajectories (solid). The cyan dashed curves indicate the tertile and mean of the distribution. b The distribution pt(x) and the recovered potential Vt(x) under the optimal protocol. The optimal potential dynamics changed instantaneously at t = 0 and t = τ, similarly to the translation-compression setup. Each distribution is calculated from 31 successive video frames and spatially smoothened by being convolved with a Gaussian-shape window with a width of 75 nm. c Accuracy of information erasure ητ evaluated as the fraction of 0 at t = τ. The inset is the bit erasure calculated as \(\Delta H\times {\log }_{2}e\) plotted against 1/τ. α is a parameter to control the accuracy and is the height ratio of the two peaks in the final target distribution. With α = 0.5, the potential is unchanged during the transport. d Work. Solid lines correspond to the theoretical minimum for work \(\Delta F+{w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\), where we use the mean \(\tau {w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) for each α as the slope and the mean ΔF for each α as the intercept. Number of samples (particles) is three for each point in (c, d). Gray closed symbols correspond to each run of more than 5000 repetitions. Colored open symbols are the mean of each condition. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (three samples for each).

We experimentally implemented the optimal information erasure protocol that was obtained numerically (Fig. 3). The kymograph clarifies the distribution dynamics (Fig. 3a). The protocol translates the fraction of the distribution in the state 1 to the state 0. The fraction in 0 is slightly compressed leftward to save space for the incoming fraction from 1. As a result, we observed a linear variation of the tertiles and mean of the distribution (dashed curves in Fig. 3a). This is the characteristic of the optimal transport as shown in Fig. 1c (right). The optimal transport dynamics are similar for different τ when time is scaled by τ (Fig. 3b). This is also the characteristic of optimal transport and is realized by different potential dynamics depending on τ. We note that, at t≥τ, the potential was fixed to Vf(x) such that the target final distribution pf(x) is the equilibrium distribution for Vf(x): \({p}_{{{\rm{f}}}}(x)\propto {e}^{-{V}_{{{\rm{f}}}}(x)/{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T}\). We did not observe significant temporal variation in pt(x) after t > τ, supporting that pt(x) reached the target distribution pf(x) at t = τ (Fig. 3a).

The accuracy of the information erasure is measured by the fraction of the state 0 at t = τ, denoted as \({\eta }_{\tau }={\int }_{-\infty }^{0}{p}_{\tau }(x){{\rm{d}}}x\). An almost perfect erasure with ητ = 0.984 ± 0.005 (mean ± standard deviation (s.d.)) was achieved even within finite time (Fig. 3c, α = 1). Because the target final distribution has a tail extending beyond x = 0, perfect erasure is not always expected. In fact, the optimal transport of a perfect erasure (ητ = 1) requires a divergence in the potential to prevent the probability distribution from leaking to the state 1 and is not accessible by experiments20,21. The corresponding bit erasure was 0.88 ± 0.03 bit (mean ± s.d., Fig. 3c, inset), which was quantified as \(\Delta H\times {\log }_{2}e\). Here, \(H(\eta )=-\eta \ln\eta -(1-\eta )\ln(1-\eta )\) is the Shannon information content defined in the natural logarithm, and ΔH = H(η0) − H(ητ). \({\eta }_{0}={\int }_{-\infty }^{0}{p}_{0}(x){{\rm{d}}}x\) was 0.495 ± 0.009 (mean ± s.d.).

Work

We measured the work W during the information erasure process (Fig. 3d, α = 1). W reached the finite-time theoretical minimum given by \(\Delta F+{w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) within error bars, validating the realization of optimal finite-time information erasure. \({w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) is given by Eq. (1). The free-energy difference ΔF corresponds to the Landauer bound, which can be reached in the quasi-static limit (1/τ → 0). ΔF consists of the free-energy change due to the bit erasure, kBTΔH17,22, and the rearrangement of the particle distribution inside the 0 and 1 states40.

The values of wd evaluated solely from the distributions coincided with those from the recovered potential (Fig. 2g), again validating the effectiveness of the distribution-based evaluation of wd with this non-harmonic setup.

Energy-speed-accuracy trade-off

It is generally expected that more accurate control requires more work, and faster control reduces accuracy, implying the trade-off between energy cost wd, speed 1/τ, and accuracy ητ11,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. To control the accuracy, we left a fraction of the distribution at t = τ so that the final distributions have double peaks; the height ratios of the two peaks are α to 1 − α (0.5 ≤ α ≤ 1, see the right panel of Fig. 3c and SI Section S2.5). The distributions are designed so that they are approximately local equilibrium distributions in each well of a double-well potential. The accuracy ητ increases with α. However, α does not solely determine ητ, since the peaks have tails extending beyond x = 0 as mentioned. We observed that the work become smaller with smaller α as well as smaller 1/τ (Fig. 3d), which implies the trade-off between energy cost, speed, and also accuracy. That is, a faster and more accurate process requires more work.

Figure 4 shows our experimental data in a way to clarify that they achieve the bound of the energy-speed-accurary trade-off. The values of τwd for different τ collapsed into a single curve, which corresponds to the finite-time minimum \(\gamma {{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{0},{p}_{\tau })\) predicted by the optimal transport theory (solid line, Eq. (1)). The fact that \(\gamma {{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{0},{p}_{\tau })\) has a finite value independent of τ indicates that τwd does not reach zero even in the quasi-static limit τ → ∞. The ordinary second law only claims the positivity of wd (dotted line). Since ητ depends on \({{\mathcal{D}}}({p}_{0},{p}_{\tau })\), the results demonstrate the trade-off between 1/τ, wd, and ητ.

The dissipated work wd was multiplied by τ to illustrate the trade-off, since wd scales with 1/τ for optimal transport (Eq. (1)). The solid curve indicates the bound by optimal transport theory (Eq. (1)). The symbols are the experimental data. The bound curve was constructed by interpolating the mean of \(\tau {w}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{\min }\) for the data with the same α (indicated by the same colors) by a cubic spline curve. The dotted line corresponds to the bound by the second law. See also Fig. S7. The colors and symbols are the same as those in Fig. 3d. Gray closed symbols correspond to each experimental run of more than 5000 repetitions. Colored open symbols are the mean values in independent runs in each condition (three samples for each). The error bars indicate s.e.m.

Discussion

In this study, we experimentally demonstrated thermodynamically optimal transport by implementing protocols that minimize dissipated work wd. We built a custom optical tweezer system capable of generating arbitrary potential profiles to optimize the distribution dynamics of Brownian microparticles in a thermal environment. We first demonstrated a simple transport problem of translating and compressing a Gaussian distribution, revealing the geometric structure of optimal transport (Fig. 2). We then experimentally applied the optimal transport protocol to information erasure, achieving the finite-time Landauer bound, equivalent to Eq. (2) (Fig. 3). Our experiment achieved the trade-off bound between energy cost, speed, and accuracy (Fig. 4).

Optimization of stochastic systems has been studied in diverse approaches41. In the literature of stochastic thermodynamics, one of the typical setups involves optimizing the protocol for varying control parameters, which are often a limited set of potential parameters, to minimize the work. This setup is referred to as optimal control42,43 and has been successfully implemented in experiments to reduce dissipation26,27,44,45,46,47,48. The finite-time information erasure has attracted particular interest in this context. For instance, an underdamped memory structure has been implemented with nano-mechanical systems by controlling the distance between the wells of double-well potentials26,27. Notably, fast optimal protocols are found to be adiabatic, with no heat exchange with the environment, which was proven to offer an efficient strategy27. For information erasure implemented with a quantum dot, an optimal protocol for controlling the energy level has been derived in the slow linear-response regime based on a so-called thermodynamic metric and experimentally implemented46.

In contrast, optimal transport seeks the optimal evolution of the distribution itself, connecting prescribed initial and final distributions8,10,49. The distribution-based optimization in optimal transport presumes full controllability of the underlying potential. Consequently, the two approaches, optimal transport and optimal control, generally yield distinct protocols. An exceptional case is Gaussian dynamics, where the full distribution is characterized solely by its mean and variance (Fig. 2), and thus optimal transport and optimal control differ only in boundary conditions (See also SI Section S4). We note that optimization of full distributions has also been studied in the context of stochastic control50,51, with different choices of cost functions from optimal transport. That being said, optimal transport theory would have a special relevance in stochastic thermodynamics, since the cost function of optimal transport is precisely equivalent to dissipation8,10.

We note that there is yet another approach to finite-time thermodynamic trade-offs, called thermodynamic uncertainty relations (TURs)33,52, which have been tested and used to estimate dissipation from experimental data53,54. However, the bounds provided by TURs are often unachievable through experiments. In contrast, the framework based on optimal transport theory provides an achievable bound (Eq. (1)) along with its optimal protocol, as experimentally demonstrated in this study.

Meanwhile, modern computers generate vast amounts of dissipation55,56. In the long term, their energetic efficiency will be fundamentally constrained by thermodynamic laws, such as the Landauer bound14,15,17 and its finite-time refinement (Eq. (2)). Our experiment highlights the crucial role of optimizing temporal dynamics in approaching such fundamental bounds. Given that CMOS technology underpins modern computing and operates far from the quasi-static limit, a fundamental challenge is whether its architecture can achieve such thermodynamic bounds57,58. While our study serves as a proof-of-concept, it is expected to provide guiding principles for the design of more energy-efficient computing devices.

Application of optimal transport to biological phenomena is another intriguing challenge. Scalability may become an issue in complex systems involving a large number of degrees of freedom, where relevant distributions are generally inaccessible. Nonetheless, complex phenomena can often be captured by a reduced set of primary degrees of freedom, as in the modeling of molecular motor dynamics59,60 or cellular migration61, thereby making the application of optimal transport approaches feasible.

Methods

Experimental setup

An infrared laser with a wavelength of 1064 nm (Spectra-Physics (MKS Instruments), MA) was focused through a 100 × objective lens (NA1.40, Evident, Japan), specialized for a near-infrared laser, equipped to an inverted microscope (Evident) to create an optical trap (Fig. S1). The laser power was adjusted by an attenuator (ThorLabs, NJ). The typical laser power at the sample was 3 mW, which was measured by an optical power meter (ThorLabs).

We trapped a silica particle with a diameter of 500 nm (Micromod, Germany) diluted by distilled water in an observation chamber with a height of 20 μm. The trap position was approximately 6 μm from the bottom glass surface. The chamber was made by sticking two pieces of coverslips (Matsunami, Japan) together with double-sided tape (Teraoka, Japan). The inlet and outlet of the channel were sealed with nail polish (DAISO, Japan) to prevent evaporation. The particle images were taken by a high-speed camera (Basler, Germany) at 4 kHz with an exposure time of 60 μs under LED illumination (ThorLabs). The room temperature was 24 ± 1 °C. The experiments were controlled by LabVIEW software (NI, TX).

The laser focal point was scanned by an electro-optical deflector (Conoptics, CT) at 16 kHz to create a trapping potential. The translation speed was controlled so that the mean light intensity at each position is proportional to the designed value of the potential at each position. We deconvolved target potential profiles by Gaussian intensity profile that approximates the laser spot to obtain the scan pattern under constraints that the total power is fixed, the spatial scanning range is limited, and the mean time duration residing at each position is positive (Fig. S4, see SI Section S1 for details).

We repeated more than 3000 repetitions for τ≤200 ms and 1500 repetitions for τ = 500 ms in each run of the translation-compression protocols for a single particle and 5000 repetitions in each run of the information-erasure protocols for a single particle. We conducted at least three runs with three different particles under each condition (actual numbers are specified in the figure captions). Each cycle of the repetitions consists of the following steps (Figs. S2 and S3); initial manipulation, pre-transport equilibration, transport, and post-transport equilibration. The initial manipulation step is only used in the information erasure, which is intended for fast relaxation to the equilibrium of the initial state between 0 and 1.

The particle position was evaluated as the centroid of the particle image, (X, Y) = [∑i, j(si, j − sth)x(xi, yi)]/∑i, j(si, j − sth), where si, j is the pixel intensity at position (i, j). The threshold intensity sth is determined as the top 20% of the intensity distribution of the whole image. This fraction-based thresholding is expected to reduce the noise due to the temporal illumination variation. The sum was taken for the pixels in the largest cluster of the pixels with intensities larger than sth, which was further processed by erosion and dilation, to reduce the effect of noise. The precision evaluated as the s.d. of the centroid of a particle fixed on a glass surface was 6.2 nm. This value is a composite value including other effects such as the oscillation of the camera, microscope body, and microscope stage.

There are multiple possibilities for generating arbitrary-shape potentials, including holographic tweezers62,63 and feedback tweezers64,65. The present method employs a relatively simple experimental setup, where the primary requirement is only the ability to scan the laser faster than the particle’s relaxation time in the optical trap.

Wasserstein distance and transport protocols

Think of transporting a one-dimensional distribution p(x) to q(x). The transport map \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{p\to q}(x)\) expresses to which position in q a segment at x in p is translated, and relates p with q as \(q(x)= \int {{\rm{d}}}{x}^{{\prime} }p({x}^{{\prime} })\delta (x-{{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{p\to q}({x}^{{\prime} }))\). For given two one-dimensional distributions p(x) and q(x), 2-Wasserstein distance \({{\mathcal{D}}}(p,q)\) is defined as

subject to the Jacobian equation \(\left|\frac{\partial {{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{p\to q}(x)}{\partial x}\right|q({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{p\to q}(x))=p(x)\)3. Here, ∥x − y∥ denotes an Euclidean distance and is ∣x − y∣ in one-dimensional systems. In one-dimensional Euclidean space, the minimization is achieved when each segment in p is translated to q without changing the positional order of the segments3. The preservation of the positional order of the segments means \(\Psi ({{{\mathcal{T}}}}_{p\to q}(x))=\Phi (x)\), where \(\Phi (x)={\int }_{-\infty }^{x}{{\rm{d}}}{x}^{{\prime} }p({x}^{{\prime} })\) and \(\Psi (x)={\int }_{-\infty }^{x}{{\rm{d}}}{x}^{{\prime} }q({x}^{{\prime} })\) are the cumulative distribution functions, and \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}_{p\to q}(x)\) is the optimal transport map, which minimizes the integral in Eq. (5). By changing variables to ϕ = Φ(x), Eq. (5) is rewritten as

where Φ−1 and Ψ−1 are the inverse functions of Φ and Ψ, respectively (see Fig. S11). We calculated the Wasserstein distance based on the expression of Eq. (6) by using the “wasserstein_1d” function of a Python library “POT: Python Optimal Transport”66.

For an overdamped Langevin dynamics, the minimum transport cost is given by Eq. (1). The optimal transport that achieves this minimum is numerically obtained2. In one-dimensional Euclidean space, the optimal transport is a linear transport without changing the positional order, such as leftmost to leftmost and center to center3 (Fig. 1c, right). The potential dynamics that realize this optimal transport are obtained by numerically solving the Fokker-Planck equation. See SI Section S2 for details, including the naive, gearshift, and intermediate protocols.

Evaluation of potential and work

The potential profile was recovered based on a drift velocity from the nonequilibrium trajectories during the transport. The method is based on the fact that the displacement of x in a short time duration is proportional to the potential force − ∂V/∂x on average. By discretizing the Langevin equation \(\gamma \dot{x}=f(x)+\sqrt{2\gamma {k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T}\xi\), we obtain \(\gamma ({x}_{i+1}-{x}_{i})=f({x}_{i})\Delta t+\sqrt{2\gamma {k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T}(B({t}_{i+1})-B({t}_{i}))\). Here, \(f(x)=-\frac{\partial V}{\partial x}\) is the potential force, and ξ is the white Gaussian noise with zero mean and unit variance. B(t) is a Wiener process. We obtain f(xi)Δt/γ by splitting xi into spatial bins and calculating the drift, that is, the average of xi+1 − xi in each bin, since the mean of B(ti+1) − B(ti) is zero. γ was estimated as described below. Then, V(xi) is recovered by integrating f(xi) and then smoothed by a window averaging.

This method is applicable to trajectories that are not settled in equilibrium. We applied the method to the trajectories during transport, where the potential profile varies in time. For each video frame, we use multiple consecutive frames around that frame of all the repetitions in each run for better statistics to obtain the potential profile. We used 21 frames for τ = 50 ms and 100 ms and 41 frames for τ = 250 ms. Slower dynamics with longer τ allow us to use more frames. Figure S5 shows examples of the recovered potentials, which are quantitatively similar to the target potentials. The potential dynamics realized by the optical tweezers are constrained by the diffraction limit. The fact that the minimum dissipated work can still be obtained suggests that the rough transport design determines the dissipated work, and the specific details do not significantly affect it. This tolerance implies the effectiveness of the optimal transport theory in broad practical systems.

The dissipated work wd = W − ΔF = W − Fτ + F0 is calculated using12,14

We calculated these values based on experimental trajectories as follows. Let xk and Vk(x) be the particle position and potential in the k-th frame, respectively. The transport step corresponds to 1 ≤ k ≤ L. k = 0 and k = L + 1 correspond to the last frame of the pre-transport step and the first frame of the post-transport step, respectively. W was calculated as

V0 and VL+1 are the potentials before and after the transport process, respectively. 〈 ⋅ 〉 denotes the average between different repetitions. We obtained wd = W − ΔF by calculating ΔF = ΔV − TΔS, ΔV = 〈VL+1(xL+1) − V0(x0)〉, and \(\Delta S=-{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{\sum }_{j}{p}_{L+1,j}\ln{p}_{L+1,j}+{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{\sum }_{j}{p}_{0,j}\ln{p}_{0,j}\). Here, j specifies the spatial bin, and pk, j is the probability of being in the j-th bin at k-th frame. For the evaluation of pk, j, multiple frames (11 frames) around a target frame were used for better statistics.

Evaluation of friction coefficient

The friction coefficient γ of each particle was measured before the transport experiments. We calculated the power spectrum C(f) of the particle position x(t) from the trajectories of a particle trapped in a harmonic potential, which obeys a Lorentzian spectrum (Fig. S12):

where f is a frequency, f0 = k/(2πγ) is a corner frequency, and k is the trap stiffness. γ is obtained by least-square fitting of fC(f) with the fitting parameters f0 and γ. The multiplication by f biases the fitting weight to the frequency region around f0, which is intended to improve the fitting accuracy.

To correct the aliasing effect caused by the finite sampling frequency, we divided the spectrum by a ‘soft’ anti-aliasing filter \(G(f)=\frac{1}{2}\left[1+{G}_{0}(f)\right]\), where \({G}_{0}(f)={\sum }_{m}{\left(\frac{f}{f-m{f}_{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)}^{2}\) is a standard anti-aliasing filter67, and fs = 4 kHz is the sampling frequency. The summation is theoretically taken for − ∞ < m < ∞, but was approximated by the summation in the finite range of − 20 ≤ m < 20. We used G(f) instead of G0(f) to take into account for the effect of the finite exposure time. The particle image is averaged during the exposure time (60 μs) at the camera, which lowers the spectrum at frequencies higher than the frequency corresponding to the exposure time, whereas the aliasing raises the spectrum at high frequencies. However, the anti-aliasing corrections do not significantly affect the estimation of γ in the present experimental setup, with relatively small f0. The corrections by G(f) and also G0(f) on the γ values were estimated to be approximately 0.05%, which is negligible compared to the standard deviation of γ for different measurement runs of the same particle (approximately 1.3%).

The value of γ was 1.01 ± 0.03 kBT s/μm2 (error is the s.d. for different particles). This value is similar to that estimated by Stokes law, γ = 6πηa = 1.05 kBT s/μm2, where η = 0.911 mPa s at 24 °C (average room temperature) is the viscosity of water, and a = 0.25 μm is the particle radius. Since the precise value of a is also not known, the estimation by the Stokes law was used only as a reference.

Data availability

The particle trajectories that support the findings of this study are available in figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2985914968.

Code availability

The Python code to reproduce our results on optimal transport dynamics is openly accessible on GitHub at [https://github.com/stoyabe/OptimalTransport/].

References

G., Monge, Mémoire sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais (De l’Imprimerie Royale, 1781).

Benamou, J.-D. & Brenier, Y. A computational fluid mechanics solution to the Monge–Kantorovich mass transfer problem. Num. Math. 84, 375 (2000).

Villani, C. Optimal Transport: Old and New (Springer, 2009).

Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S. & Bottou, L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2017), Vol. 70 (eds Precup, D. & Teh, Y.W.) 214–223. http://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/conf/icml/icml2017.html#ArjovskyCB17 (PMLR, 2017).

Lipman, Y., Chen, R.T.Q., Ben-Hamu, H., Nickel, M. & Le, M. Flow matching for generative modeling. in Proc. 11th International Conference on Learning Representations.https://openreview.net/forum?id=PqvMRDCJT9t (2023).

Schiebinger, G. et al. Optimal-transport analysis of single-cell gene expression identifies developmental trajectories in reprogramming. Cell 176, 928 (2019).

Aurell, E., Gawȩdzki, K., Mejía-Monasterio, C., Mohayaee, R. & Muratore-Ginanneschi, P. Refined second law of thermodynamics for fast random processes. J. Stat. Phys. 147, 487 (2012).

Aurell, E., Mejía-Monasterio, C. & Muratore-Ginanneschi, P. Optimal protocols and optimal transport in stochastic thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 250601 (2011).

Chen, Y., Georgiou, T. T. & Tannenbaum, A. Stochastic control and nonequilibrium thermodynamics: fundamental limits. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 65, 2979 (2019).

Nakazato, M. & Ito, S. Geometrical aspects of entropy production in stochastic thermodynamics based on Wasserstein distance. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043093 (2021).

Ito, S. Geometric thermodynamics for the Fokker–Planck equation: stochastic thermodynamic links between information geometry and optimal transport. Inf. Geom. 7, 441 (2024).

Seifert, U. Stochastic thermodynamics, fluctuation theorems and molecular machines. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 126001 (2012).

Ciliberto, S. Experiments in stochastic thermodynamics: Short history and perspectives. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021051 (2017).

Peliti, L. & Pigolotti, S. Stochastic Thermodynamics: an Introduction (Princeton University Press, 2021).

Parrondo, J. M. R., Horowitz, J. M. & Sagawa, T. Thermodynamics of information. Nat. Phys. 11, 131 (2015).

Shiraishi, N., Saito, K. & Tasaki, H. Universal trade-off relation between power and efficiency for heat engines. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 190601 (2016).

Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 5, 183 (1961).

Sagawa, T. & Ueda, M. Minimal energy cost for thermodynamic information processing: Measurement and information erasure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 250602 (2009).

Lutz, E. & Ciliberto, S. Information: from Maxwell’s demon to Landauer’s eraser. Phys. Today 68, 30 (2015).

Proesmans, K., Ehrich, J. & Bechhoefer, J. Finite-time Landauer principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 100602 (2020).

Proesmans, K., Ehrich, J. & Bechhoefer, J. Optimal finite-time bit erasure under full control. Phys. Rev. E 102, 032105 (2020).

Bérut, A. et al. Experimental verification of Landauer’s principle linking information and thermodynamics. Nature 483, 187 (2012).

Jun, Y., Gavrilov, M. & Bechhoefer, J. High-precision test of Landauer’s principle in a feedback trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 190601 (2014).

Gavrilov, M. & Bechhoefer, J. Erasure without work in an asymmetric double-well potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 200601 (2016).

Ribezzi-Crivellari, M. & Ritort, F. Large work extraction and the Landauer limit in a continuous Maxwell demon. Nat. Phys. 15, 660 (2019).

Dago, S., Pereda, J., Barros, N., Ciliberto, S. & Bellon, L. Information and thermodynamics: Fast and precise approach to Landauer’s bound in an underdamped micromechanical oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 170601 (2021).

Dago, S., Ciliberto, S. & Bellon, L. Adiabatic computing for optimal thermodynamic efficiency of information processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2301742120 (2023).

Toyabe, S., Sagawa, T., Ueda, M., Muneyuki, E. & Sano, M. Experimental demonstration of information-to-energy conversion and validation of the generalized Jarzynski equality. Nat. Phys. 6, 988 (2010).

Koski, J. V., Maisi, V. F., Pekola, J. P. & Averin, D. V. Experimental realization of a Szilard engine with a single electron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 13786 (2014).

Hopfield, J. J. Kinetic proofreading: A new mechanism for reducing errors in biosynthetic processes requiring high specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 71, 4135 (1974).

Andrieux, D. & Gaspard, P. Nonequilibrium generation of information in copolymerization processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 9516 (2008).

Lan, G., Sartori, P., Neumann, S., Sourjik, V. & Tu, Y. The energy-speed-accuracy trade-off in sensory adaptation. Nat. Phys. 8, 422 (2012).

Barato, A.C. & Seifert, U. Thermodynamic uncertainty relation for biomolecular processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.114.158101 (2015).

Dechant, A. Minimum entropy production, detailed balance and Wasserstein distance for continuous-time Markov processes. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 55, 094001 (2022).

Yoshimura, K., Kolchinsky, A., Dechant, A. & Ito, S. Housekeeping and excess entropy production for general nonlinear dynamics. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013017 (2023).

Vu, T. V. & Saito, K. Thermodynamic unification of optimal transport: thermodynamic uncertainty relation, minimum dissipation, and thermodynamic speed limits. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011013 (2023).

Klinger, J. & Rotskoff, G.M. Universal energy-speed-accuracy trade-offs in driven nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. E 111. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.111.014114 (2025).

Nango, E. et al. A three-dimensional movie of structural changes in bacteriorhodopsin. Science 354, 1552 (2016).

Klebl, D. P. et al. Swinging lever mechanism of myosin directly shown by time-resolved cryo-EM. Nature 642, 519 (2025).

Sagawa, T. Thermodynamic and logical reversibilities revisited. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2014, P03025 (2014).

Bechhoefer, J. Control Theory for Physicists 658 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Schmiedl, T. & Seifert, U. Optimal finite-time processes in stochastic thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 108301 (2007).

Blaber, S. & Sivak, D. A. Optimal control in stochastic thermodynamics. J. Phys. Comm. 7, 033001 (2023).

Barros, N., Ciliberto, S. & Bellon, L. Probabilistic work extraction on a classical oscillator beyond the second law. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 057101 (2024).

Tafoya, S., Large, S. J., Liu, S., Bustamante, C. & Sivak, D. A. Using a system’s equilibrium behavior to reduce its energy dissipation in nonequilibrium processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 5920 (2019).

Scandi, M. et al. Minimally dissipative information erasure in a quantum dot via thermodynamic length. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 270601 (2022).

Maillet, O. et al. Optimal probabilistic work extraction beyond the free energy difference with a single-electron device. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 150604 (2019).

Loos, S. A., Monter, S., Ginot, F. & Bechinger, C. Universal symmetry of optimal control at the microscale. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021032 (2024).

Chennakesavalu, S. & Rotskoff, G. M. Unified, geometric framework for nonequilibrium protocol optimization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 107101 (2023).

Kappen, H. J. Linear theory for control of nonlinear stochastic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 200201 (2005).

Todorov, E. Efficient computation of optimal actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 11478 (2009).

Horowitz, J. M. & Gingrich, T. R. Thermodynamic uncertainty relations constrain non-equilibrium fluctuations. Nat. Phys. 16, 15 (2019).

Song, Y. & Hyeon, C. Thermodynamic uncertainty relation to assess biological processes. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 130901 (2021).

Marsland, R., Cui, W. & Horowitz, J. M. The thermodynamic uncertainty relation in biochemical oscillations. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20190098 (2019).

Ball, P. Computer engineering: Feeling the heat. Nature 492, 174 (2012).

Markov, I. L. Limits on fundamental limits to computation. Nature 512, 147 (2014).

Freitas, N., Delvenne, J.-C. & Esposito, M. Stochastic thermodynamics of nonlinear electronic circuits: A realistic framework for computing around kT. Phys. Rev. X 11. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.11.031064 (2021).

Wolpert, D.H. et al. Is stochastic thermodynamics the key to understanding the energy costs of computation? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2321112121 (2024).

Kawaguchi, K., Sasa, S. -i & Sagawa, T. Nonequilibrium dissipation-free transport in F1-atpase and the thermodynamic role of asymmetric allosterism. Biophys. J. 106, 2450 (2014).

Mishima, T. et al. Efficiently driving F1 molecular motor in experiment by suppressing nonequilibrium variation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 148402 (2025).

Brückner, D. B. & Broedersz, C. P. Learning dynamical models of single and collective cell migration: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 056601 (2024).

Gladrow, J., Ribezzi-Crivellari, M., Ritort, F. & Keyser, U.F. Experimental evidence of symmetry breaking of transition-path times. Nat. Commun. 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07873-9 (2019).

Chupeau, M., Gladrow, J., Chepelianskii, A., Keyser, U. F. & Trizac, E. Optimizing brownian escape rates by potential shaping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 1383 (2019).

Kumar, A. & Bechhoefer, J. Nanoscale virtual potentials using optical tweezers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 183702 (2018).

Albay, J. A. C., Paneru, G., Pak, H. K. & Jun, Y. Optical tweezers as a mathematically driven spatio-temporal potential generator. Opt. Exp. 26, 29906 (2018).

Flamary, R. et al. POT: Python optimal transport. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22, 1 (2021).

Berg-Sørensen, K. & Flyvbjerg, H. Power spectrum analysis for optical tweezers. Rev. Sci. Inst. 75, 594 (2004).

Toyabe, S. Particle trajectories. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29859149 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Takayuki Ariga and Kenji Nishizawa for their technical assistance. This work was supported by JST ERATO Grant Numbers JPMJER2204 and JPMJER2302 (to S.I., T.S., and S.T.), and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22H01141 (to S.I.), JP23H00467 (to S.I.), JP24H00834 (to S.I.), and JP23H01136 (to S.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.O., Y.N., S.I., T.S. and S.T. designed the research and wrote the paper. S.O. performed experiments. S.O., Y.N. and S.T. developed the experimental systems, contributed analytic tools, and analyzed data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interest: a patent application related to the scanning optical tweezers method has been filed in Japan (Japanese Patent Application No. 2024-139284, Inventors: Shoichi Toyabe, Yohei Nakayama, Shingo Oikawa, Sosuke Ito, and Takahiro Sagawa. Institutions: Tohoku University and The University of Tokyo).

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oikawa, S., Nakayama, Y., Ito, S. et al. Experimentally achieving minimal dissipation via thermodynamically optimal transport. Nat Commun 16, 10424 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66519-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66519-9