Abstract

Microbialites are lithifying microbial mats that form multi-layered structures via biological carbon (C) uptake and carbonate precipitation. Here we relate C uptake and precipitation rates to taxonomic diversity and functional capacity of bacterial communities in supratidal freshwater microbialites. Diel assays and analysis of functional gene capacity reveal that photosynthesis is bolstered by light-independent, biological C uptake mechanisms, including biomineralization and chemoautotrophy. Through integration of these mechanisms, microbialites can capture inorganic C over a 24-hour cycle at a rate of 7-12 g C m-2 24 h-1. Notably, up to 87 % of the C taken up is precipitated as inorganic carbon, capturing 2.4 − 4.3 kg C m-2 year-1. Based on observed porosity and laboratory-based accretion rates, this equates to 13-23 mm of vertical calcium carbonate accumulation per year. Hence, contemporary microbialites provide a highly effective biological mechanism to precipitate dissolved CO2 as geologically stable carbonate mineral deposits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbialites are lithifying microbial mats formed through the biogenic precipitation of minerals, and their fossils represent the earliest microbial communities on Earth1,2. Microbialites with a distinctive layered structure, known as stromatolites, are well preserved in the fossil record and reflect an intimate connection between microbialites, the global carbon (C) cycle and Earth’s geological evolution3. However, the impact of specific geochemical and biological interactions between these microbial communities and their environment remains difficult to determine in their fossilized remains4. Living microbialites continue to thrive in both temperate and extreme environments (Fig. 1), and therefore provide important insight into fundamental biotic and chemical processes that may have occurred in ancient microbialite systems, and how they influenced the geochemical conditions of the environment4. C autotrophy is arguably the oldest metabolic process on Earth5. In most ancient and living microbialites, oxygenic photosynthesis appears to be the major source of bioavailable C and a key metabolic driver of microbialite formation6,7,8. While oxygenic photosynthesis is considered to have been the major biological C sequestration process taking place, evidence from Archean Strelley Pools formations indicates that non-oxygenic chemoautotrophic forms of C sequestration, such as the Wood-Ljungdahl (WL) pathway, are likely to have occurred in addition to the Calvin cycle9,10. These same pathways and other forms of non-oxygenic, chemoautotrophic C sequestration are proposed to still be active in modern microbialite formations. Functional gene abundances and sulfur isotope distribution patterns in the hypersaline, smooth mat formations of Hamelin Pools, Shark Bay, infer that non-RuBisCO-based forms of autotrophy, such as the 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle (3HP), the WL pathway, and sulfur cycling metabolisms, may be active11,12. Similarly, metagenomic analysis of Bahamian stromatolites suggests that sulfur cycling and methanogenesis may play an important role in the C cycle as well as in stromatolite formation in marine systems13,14,15. Unlike other microbial mats, microbialites precipitate carbonate through biological alkalinization, potentially aided by the trapping and release of cations by exopolymers to form C-containing minerals, such as calcite and aragonite2,16, that can sequester C for extended periods on the order of 106 years17. Notably, in addition to pH (Fig. 1), the chemical activities of carbonate (CO₃²⁻) and calcium (Ca²⁺) also strongly influence microbialite formation. Recent work shows that microbialites often develop in waters oversaturated with respect to metastable CaCO₃ phases such as amorphous calcium carbonate or monohydrocalcite, highlighting that these and other permissive physicochemical conditions may also be required for biogenic precipitation to proceed18,19.

The relative proportions of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) species (CO₂, HCO₃⁻, CO₃²⁻) are shown as a function of pH. Colored bars indicate pH ranges measured across microbialite-bearing environments: Exuma Sound (green), Cuatro Ciénegas (red), Pavilion Lake (blue), and RSA peritidal sites (gray). Vertical dashed lines denote mean pH values for Exuma Sound (red), Republic of South African (RSA) peritidal (black), Pavilion Lake (blue), Lake Untersee (green), Hamelin Pools (cyan), and Cuatro Ciénegas (yellow). Corresponding temperature ranges for each environment are indicated at right. The carbonate equilibrium demonstrates how bicarbonate serves as the dominant species under buffered conditions and drives CaCO₃ precipitation, with CO₂ produced in the reaction being reincorporated into the system23,52,53,54,55,56.

Living microbialites are widely distributed along the southeastern coastline of South Africa20,21,22, southwestern coast of Australia and north coast of Northern Ireland23. These formations occur in the supratidal environment at the terrestrial-marine interface, where calcium-rich hard water from sand dune seeps mixes with tidal ocean waters23,24,25,26. In South Africa, individual microbialite systems may receive distinctly different freshwater nutrient inputs. For example, there is a six-fold difference in the average dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) concentration at Cape Recife (76.6 ± 19.6 μM) and Schoenmakerskop (457.3 ± 333.4 μM), which are only 3 km apart24. Despite these differences, conserved functional guilds of bacteria are shared by both Cape Recife and Schoenmakerskop stromatolites27. The similarities between the functional capacities of these two systems lie in their potential to utilize and assimilate nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus, which likely impact their formation. In addition, the high proportion of metagenomic assembled genomes assigned as Cyanobacteria (40–70%) would suggest these systems have a substantial capacity for oxygenic photosynthesis27. In this study we relate the rates of C uptake to bacterial diversity and functional capacity in contemporary microbialites, quantifying their efficiency to remove dissolved CO2 from their freshwater environment.

Results

Microbialite systems and environmental factors

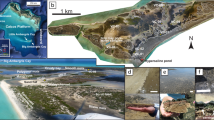

Microbialite formations from four distinct sites along ~ 105 km of the southeastern coastline of South Africa were selected for this study (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the east, near Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth), are the Cape Recife (CR) and Schoenmakerskop (SK) microbialite sites that have been confirmed as stromatolites22,24,25. Thyspunt (TP), near Oyster Bay, is the most westerly site, while OV745 is located ~10 km to the east of TP. At CR, SK, and TP, freshwater flows over a series of fluvial formations along shallow barrage pools in the intertidal zone (Fig. 2A–C). The OV745 site feeds from a small concrete water tank, that overflows to create a ~ 3 m vertical waterfall microbialite formation (Fig. 2D) that terminates in the intertidal zone. The formations at TP and OV745 also show a distinctive layered structure (Fig. 2C, D, inserts), but whether or not they can be classified as stromatolites remains to be confirmed. The formations sampled in this study are distinct from most lake and marine formations in that they are continually fed by undiluted, fresh ground water inflows. The water flowing over the surface is a few mm to a few cm in depth depending on the location. High flow rates (up to 28 L min-1) and relatively consistent pH (~8.5) across season and location (freshwater source to marine influenced end member) highlights the consistent and well mixed nature of these sites26.

All four sites are shallow, groundwater-fed formations. A Cape Recife; (B) Schoenmakerskop; (C) Thyspunt and (D) Cape St Francis OV745. Samples were collected from the freshwater inflows at each site. Inserts show the lithified structure of stromatolite formations. E Nutrient concentrations of the freshwater entering microbialite systems.

The four microbialite systems in this study (including the two stromatolites) are distinguished by the different nutrient properties of their freshwater inflows (Fig. 2E), notably with respect to dissolved nitrogen levels. Most of the total dissolved nitrogen in the four systems occurs in the form of NO3− (69–85%), with SK having the highest NO3− concentration (328.01 µM), followed by CR (69.71 µM), OV745 (31.49 µM) and TP with the lowest concentration (12.28 µM). While excessively high for most natural water bodies, NO3− levels between 200 µM − 300 µM are relatively common for ground water in the dune fields around Gqeberha28. Concentrations of NH4+ and PO43− were generally low, but varied between the systems, while SK and OV745 received substantially more dissolved organic C (DOC) than the other two systems (Fig. 2E). The nutrient concentrations at the four sites were found to be chemically distinct from one another (Supplementary Fig. 2), confirming that they receive separate and unique inflows and highlighting the diversity of geochemical environments in which these microbialites thrive.

Microbial community diversity analysis

Non-metric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS) plots of 16S rRNA gene Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU0.03) showed distinct bacterial communities at the four sites, with two major clusters: SK together with CR in one cluster and OV745 in another (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table 1). The samples from TP were separated from the other clusters, but there were too few replicates to consider them a definitive group. Consistent with a previous study27, the clustering of SK with CR bacterial communities infers that nutrient availability may not be the principal determinant of diversity at these formations. Overall, taxa belonging to 44 Eubacteria phyla were detected, with the majority of dominant OTUs classified as Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, or Proteobacteria (Fig. 3B). Cyanobacteria were the most abundant OTUs at all sites, with several shared between CR and SK. OTU 1, of the family Phormidiaceae, was present in nearly all samples and was dominant at OV745, comprising up to 63% of the total reads (Fig. 3B).

A Non-metric MultiDimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination diagram of 16S rRNA Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU0.03) in samples collected from the inflows at each microbialite site. B Phylogenetic classification and relative abundance of the 50 most numerically abundant OTUs. CR-2018, SK-2018, OV745-2018, and TP-2018 samples were collected in January 2018, while OV745-2019 samples were collected in January 2019, and CR-2019 and SK-2019 sampling were conducted in August 2019.

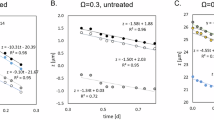

Carbon uptake

Photosynthesis is accepted to be the major factor driving microbialite formation6. In addition, the transformation of dissolved inorganic C (DIC) into carbonate minerals through alkalinization also contributes to particularly high rates of C uptake in these systems. The DIC pool at the study sites is dominated (98%) by bicarbonate (HCO3−)26 making it an ideal source for tracking C uptake29,30. Daytime bicarbonate (H13CO3−) 13C stable isotope tracer experiments were used to measure the C uptake of microbialite communities at CR, SK, TP and OV745, representing four contrasting nutrient regimes. H13CO3− uptake was observed in samples from all the sites (Fig. 4A). The highest specific uptake rates (the measurement of uptake of 13C into particulate C (PC) over time) were detected at CR (0.0132 ± 0.0019 h−1), followed by OV745 (0.0097 ± 0.0013 h−1), SK (0.0065 ± 0.0012 h−1) and TP (0.0012 ± 0.0001 h−1) (Fig. 4A, and Supplementary Table 2). There was no significant difference in C uptake rates between OV745 and SK, however, all other site combinations were significant with the largest difference observed between TP and CR (p = 0.00002; Supplementary Table 3). With the exception of ammonium, none of the nutrients measured correlated with the specific 13C uptake rates (Supplementary Fig. 3, and Supplementary Table 4). While CO2 uptake and release were not directly measured in this study, the use of 13C stable isotope tracer methods is a well-established method for assessing C uptake in aquatic systems29.

A In situ specific carbon uptake rates measured using 13C tracer. B Carbon energy metabolism gene clusters (KO) present in the metagenomes of stromatolite samples used for carbon uptake experiments. Listed are the relative abundances of genes/clusters involved in photosynthesis, photosynthesis-antenna proteins, photosynthetic carbon fixation, methane metabolism, and other carbon fixation pathways in prokaryotes. CR Cape Recife, SK Schoenmakerskop, TP Thyspunt, OV745: Cape St Francis.

Analysis of shotgun metagenome sequence data from all four sites revealed the presence of genes involved in photosynthesis, as well as genes that may represent alternative routes for C uptake. The relative abundance of genes associated with oxygenic photosynthesis was higher at CR, SK and TP compared to OV745 (Fig. 4B, and Supplementary Table 5). Contrary to expectations, the relative abundances of photosystem and photosynthetic pigment genes at OV745 were lower than that observed for SK, which has similar, but on average lower, C-specific uptake rates. However, we noted that carbonic anhydrases, specifically gene cynT (K01673), were abundant in all sampled sites. Taxonomic classification of bacterial contigs showed that genes encoding CAs were primarily from Cyanobacteria (Coleofasciculaceae Oscillatoriaceae and Chamaesiphonaceae), Proteobacteria (Desulfobulbaceae) and Bacteriodetes (Cytophagales) phyla (Supplementary Table 5). There was a similar high abundance of a gene predicted to encode trimethylamine-corrinoid protein Co-methyltransferase (K14083) assigned to the Proteobacteria (Rhodobacteraceae and Desulfovibrionaceae) and Chloroflexi in all formations except for CR that could be indicative of the potential for some methanogenic capacity. The presence of genes associated with both branches of the WL pathway, mainly from Desulfobulbaceae, Cytophagales, the cyanobacterial Chamaesiphonaceae and Leptolyngbyaceae families as well as unclassified Chloroflexi (Supplementary Table 5) highlight the capacity for chemoautotrophic C fixation in all formations and, in particular, at OV745 (Fig. 4B).

To further investigate the contribution of non-photosynthetic mechanisms to C uptake, we focused on OV745, which had a lower abundance of genes associated with photosynthesis, but a relatively high C uptake rate. To assess the contribution of non-photosynthetic C assimilatory pathways, we conducted diel H13CO3− tracer experiments using standardized samples (17 mm diameter and 10 mm depth), allowing us to calculate absolute C uptake rates. Mercuric chloride (HgCl2) was used in parallel control treatments to halt biological (induced) incorporation to determine the fraction of observed uptake that was due to the presence of extracellular organic molecules (influenced) and abiotic precipitation. These experiments confirmed the temporal reproducibility and homogeneity of both C uptake and the metagenomic profile of samples from the OV745 formation. There was no significant difference between uptake rates observed from OV745 samples collected in 2018 and 2019 (p = 0.3025). Daytime C uptake rates were consistent and statistically similar in all four OV745 experiments spanning both years (Fig. 5A) and the patterns of C uptake genes remained similar, with an abundance of genes encoding CAs present as well as several copies of genes involved in proton generation (Fig. 5C).

A Daytime specific H13CO3- uptake rates and (B) night specific H13CO3- uptake rates. The shaded area in (A) delineates C uptake rates measured in 2018. The dashed lines at the bottom of each panel show the H13CO3- uptake rate of samples collected for the night-time experiments (n = 3) amended with HgCl2 to prevent biotic growth and incorporation; these lines indicate the maximal corresponding abiotic carbon uptake rates. C Carbon energy metabolism gene clusters (KO) present in the metagenomes of OV745 stromatolite samples used for diel carbon uptake experiments. Listed are the relative abundances of genes/clusters involved in photosynthesis, photosynthesis-antenna proteins, photosynthetic carbon fixation, methane metabolism, and other carbon fixation pathways in prokaryotes.

Night-time rates (Fig. 5B) represented on average 80% of C uptake observed during the day, with average daytime and night-time rates of 0.0112 ± 0.0030 h−1 and 0.0090 ± 0.0036 h−1, respectively. Furthermore, HgCl2-treated control experiments placed abiotic incorporation/precipitation at only 8 to 12% of the daytime rates and 11 to 15% of the night-time rates (Fig. 5A,B), significantly lower (p < 0.00506) than all 13C uptake measurements, indicating that the rates observed are biologically driven. Since the amount of microbialite sample used in each incubation was known for the 2019 study, we were able to calculate the absolute uptake rate in terms of the surface area of stromatolite formation. In the OV745 system, absolute C uptake was calculated to range from 4.20 to 5.18 g C m−2 12 h−1 during the day and 1.75 to 6.70 g C m−2 12 h−1 at night. When combined, the rates ranged from 6.68 to 11.88 g C m−2 24 h−1 (Fig. 6), corresponding to annual uptakes of 2.44 to 4.34 Kg C m−2 yr−1, or 8.94 to 15.90 Kg CO2 m−2 yr−1.

Rates were estimated from the combined 12-h daytime rates and 12-h nighttime rates in OV745 microbialites measured using the 13C tracer method (see Supplementary Data 1 for full calculations). Error bars: OV745-1 (n = 2); OV745-2 (n = 3); OV745-3 (n = 3).

To confirm that the C taken up by the microbialites was contributing to accretion (defined as the precipitation of mineral inorganic C), additional studies were conducted at OV745 in 2022. Replicate uptake samples collected from the same incubations were acidified and the loss of inorganic C and isotopic enrichment were compared to their non-acidified counterparts. Inorganic C represented 82 ± 6% of the total C, and 87 ± 3 % of the total isotope enrichment observed in bicarbonate uptake was lost with the removal of the inorganic fraction (Supplementary Fig. 4). This means that the majority of the C taken up by the microbialite communities is precipitated as carbonate, which has a higher potential for long term storage.

The accretion of C in mineralized parts of microbialite formations has been estimated in a previous study from the relative proportions of porosity, detrital silicate, and biogenic phosphatic and calcium carbonate precipitates in material from CR22. We have since analysed carbonate material from Cape Recife, Schoenmakerskop and Cape St Francis (OV745) using powder X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD; Supplementary Fig. 4). All spectra indicate that the precipitating phase is calcite rather than another CaCO3 polymorph (aragonite or vaterite).

The amount of C stored in the stromatolites depends on the proportions of calcite, mineral detritus washed in with the freshwater supply, phosphatic microbialite precipitates, and pore space, which we estimated from the evaluation of scanning electron microscope (SEM) imagery (Fig. 7A) and mass balance calculations (see “Methods” section). The C concentration in the analyzed microbialite samples ranged between 5.3 and 9.5 wt% (Fig. 7B). The pore space varied significantly (between 24 and 55.6 vol%). Detrital silicates were typically rare (0–2.3 vol%) and where biogenic phosphate (up to 30 vol% in one selected area) was abundant22, the stored C content was lowest. There is no textural evidence for the authigenic growth of silicate minerals. Typically, the mineralized parts of the stromatolites from CR did not show significant amounts of silicate detritus and phosphate, and in such domains the C contents ranged between 8.2 and 9.5 wt% (average: 8.7 wt% C, corresponding to 32 wt% CO2) with a (water-filled) porosity between 42.0 and 55.6 vol% (average 50.2 vol%). At an average density of 1.85 t m−3, this corresponds to an accretion of 161 kg C m−3 or the equivalent of 592 kg CO2 m−3 in mineralized stromatolite material at CR (Fig. 7B).

A Backscattered Electron images of representative stromatolite samples from Cape Recife. The signal for calcite (Cc) is shown in white, phosphatic stromatolite material (PS) and detrital silicate (DS) are gray and pore spaces (P) appear black. B Estimates of mineral phase and pore space proportions, CO2 and C weight percentages, calculated densities and CO2 and C mass per m3. Calculations are described in the “Methods” section. The calculation spreadsheet is available as Supplemental data 2.

The accretion of 8.94 to 15.90 kg CO2 m−2 yr−1 measured at OV745 equates to the precipitation of 20.3 to 36.2 kg calcite m−2 yr−1. At an observed porosity of ~50 vol% (Fig. 7B) this corresponds to a deposition of 13 to 23 mm thick porous calcite precipitate per year. Under controlled laboratory settings, nascent microbialites cultured from field samples can grow at a rate of ~1 mm in diameter per week (Fig. 8), suggesting that the rate of deposition observed in the field could be even higher under conditions where macro- and micro-nutrients are non-limiting and the water supply is consistent.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between C uptake rates and the underlying metabolic processes in contemporary microbialites. We assessed the relationship between nutrients, microbial diversity, functional genetic potential, and C uptake. We demonstrate that the novelty of the microbialites in this study lies in their ability to biotically sequester C into stable mineral deposits at high rates over the entire diel cycle. The near-continuous high rates, combining multiple uptake mechanisms, may set these South African microbialites apart from non-lithifying microbial mats2,31 and other microbialite systems12,32.

An abundance of genes encoding CAs and Nha family cation antiporters were detected in all of the OV745 samples. CAs are used as C concentrating mechanisms to increase the intracellular CO2 levels around RuBisCO for fixation33 and the cation antiporters may play a role in controlling the pH of the microbialite system34. Changes in alkalinity previously measured in the SK formation suggest that mineralization can account for significant C uptake during the day35. This process could continue at night, bolstered by the activity of extracellular CAs that catalyze the precipitation of carbonate minerals through interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−. Extracellular CAs have been identified in the microbialite-forming Microcoleus chthonoplastes, where they have been hypothesized to play a role in CaCO3 formation36, which is noteworthy, as OTU1, the most dominant OTU, was also classified within the family Phormidiaceae, and may represent a close relative fulfilling a similar role in the South African microbialites.

Night-time C uptake may be driven by active HCO3− uptake to fill biological C demand and also biologically-driven mineralization, as a by-product of a system where net metabolic activity is balanced in favor of alkalinisation. We note that we did not measure CO2 fluxes directly in this study. However, the high buffering capacity of the inflow waters and the favorable conditions supporting carbonate equilibrium reactions (Fig. 1) ensures that much of the CO2 released during CaCO3 precipitation is rapidly reincorporated as HCO3− and the small amount of CO2 remaining would likely be quickly consumed by the highly active resident microbial community30. Hence, the lack of CO2 measurements does not diminish our findings as we show that HCO3− is biologically assimilated and precipitated as calcite, supporting microbialite growth and long-term carbon stabilization. Gene products related to H+ transport (Na+:H+ antiporters), H2 production (bidirectional hydrogenases) and electron bifurcation, which can be linked to H+ import, may aid carbonate precipitation by removing H+ 37,38. Supported by the activity of extracellular or intracellular CAs, these mechanisms are likely responsible for the sustained levels of C uptake observed over the full diel cycle. This may also be occurring in other microbialites where night-time uptake has not been measured. Chemoautotrophy has been documented in siliceous stromatolites at night, but the potential for long-term storage of C is limited because they do not precipitate carbonate minerals39.

The daytime uptake rates measured in OV745 samples averaged 11.17 mgC gC−1 h−1 or 396 mg C m−2 h−1 (i.e., 4.75 g C m−2 12 h−1; Fig. 6). These rates are consistent with photosynthetic rate estimates in a previous study using intact stromatolite material from SK35 and are significantly higher than highly productive microbial mats such as those of Tengchong and Little Hot Creek (4.6 mgC gTOC−1 and 1.82 mgC gC−1 h−1 for non-lithifying and lithifying mats, respectively)2,31. The rates measured for OV745 were also higher than other stromatolites, such as Hamelin Pool formations, predominantly formed through carbonate precipitation, and Bahamian formations that are formed through trapping and binding (113 mg C m−2 h−1 and ~10 mg C m−2 h−1, respectively)13,31. When night-time rates are taken into account, and the process is extrapolated to a 24-h day, the absolute rates of C uptake by the OV745 microbialites examined in this study account for 6.68 to 11.88 g C m−2 day−1 or the equivalent of 8.94 to 15.90 kg CO2 m−2 year−1.

By assessing the proportion of bicarbonate uptake that was retained as inorganic vs organic C, and then additionally comparing this to the abiotic precipitation we show that some microbialites are very efficient at C precipitation. Our findings are further supported by daytime rates of CaCO3 precipitation reported by du Plooy et al. 35, who found that the SK stromatolites may be precipitating more than 87 % of their C uptake, the same proportion that we found using an alternative C-based approach. Based on C uptake and accretion rates and the growth of laboratory cultures, we estimate that the OV745 microbialites have the potential of vertical layer growth between 13–23 mm per year under ideal conditions. Actual formational growth in nature is likely lower due to weathering, periods of desiccation and other seasonal fluctuations. These potential growth rates are three to five-fold higher than the maximum rate estimated for the microbialites of the alkaline Clinton Creek formations40 and orders of magnitude higher than the Highbourne Cay and Shark Bay systems (0.33 mm and 0.4 mm year−1), respectively40,41,42. Alkalinity and elevated Mg/Ca ratios have been identified as additional factors that correlate with carbonate precipitation in some freshwater lakes18. The Mg/Ca ratios reported for the inflows of the sites used in our study are low, ranging from 0.15 to 0.2126, suggesting that they are likely not a driving factor in our systems, limiting meaningful comparison due to key hydrological differences (flow rates, ground water dilution, water column depth).

By continuing the daytime C uptake after sunset, and with the ability to convert C removed from freshwater into a geologically stable form that can persist for billions of years, the South African supratidal microbialites may provide one of the most efficient biological mechanisms for long-term C storage observed in nature. Our study raises intriguing new questions about the mechanisms controlling diel C fixation and precipitation in these systems and whether environmental conditions can be adjusted to further increase the rates of C extraction from the C cycle as a potential tool to mitigate C emissions and combatting global environmental change.

Methods

Study site description

All four microbialite systems that are the focus of this study are entirely and directly fed by constant groundwater seep inflows and the water flows along a vertical gradient of microbialite (rock) at flow rates up to 28 L min-1 26. The depth of the water over the microbialites varies from millimeters to centimetres. The Cape Recife (CR) and Schoenmakerskop (SK) sites are within 3 km of each other. Microbialite formations at both sites begin to form at the freshwater inflows in the supratidal zone (Supplementary Fig. 1). At CR these formations follow a long ~8 m stream before branching off into two barrage pool structures, while at SK and Thyspunt (TP), the freshwater inflows run into larger, shallow barrage pools where encrusting microbialites form. The OV745 microbialites at Cape St Francis form below a shallow man-made reservoir (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Freshwater in this system is fast-flowing and the OV745 structure forms a large ~3 m tall waterfall microbialite that ends abruptly just above the subtidal zone (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig 1D). All microbialites sampled for this study s show a thin green surface layer (~1-2 mm think) indicative of cyanobacterial abundance (Fig. 2A-D, insets).

Sample collection and laboratory cultures

Field expeditions were conducted during the austral summer (January 16–18, 2018, and February 20, 2019) and austral winter (July 9-10, 2022). Daytime temperatures in the freshwater microbialite pools typically average between 23 °C and 24 °C during the summer months20 and 16 °C to 18 °C in July. In 2018 microbialite biomass and water samples were collected from the shallow flowing region as the seep water enters each of the four different formations at TP (34˚11'24“S 24˚42'13“E) in the west, followed by OV745 (34˚11'47“S 24˚46'37“E), CR (34˚02'42“S 25˚34'07“E), and SK (34˚02'28“S 25˚32'18“E) (Fig. 2). Additional samples were collected from SK, CR and OV745 in August 2019 for 16S rRNA metabarcoding analysis and from OV745 in July 2022 for C uptake assessments. Samples were removed from the microbialite face, placed in Ziploc plastic bags and stored in a cooler. Ten liters of inflow water were collected in acid-washed plastic bottles. The microbialite and water samples were transported to the field laboratories (~2 h), where water for use in the tracer experiments was filtered through 0.22 µm nylon membrane filters (Pall) under vacuum. Water for nutrient analysis was filtered through 0.3 µm pre-combusted (450 °C for 4 hr) GF-75 filters (Advantec). Biomass samples for DNA analysis were preserved in RNALater (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −20 °C. The remaining biomass was pulverized in filtered site water, and granular particles were removed with a metal sieve before use in 13C tracer experiments. During 2019, OV745 samples were collected with an auger generating samples 17 mm in diameter and 10 mm in depth. Half of the sample was used for 13C tracer experiments, while the remainder was preserved in RNALater for metagenomics analysis and stored at −20 °C.

Laboratory cultures of nascent microbialites were generated from a dilute slurry of pulverized samples resuspended in the freshwater inflow collected from the Schoenmakerskop site in November 2022. The slurry was inoculated into ninety-six well microtiter plates and fed with filtered source water from the site under standard grow lights in a 12-h light-dark cycle. The water was exchanged weekly, and representative microbialites were collected every seven days over the six-week period of incubation.

Uptake measurements

2018: Due to their rock-like structure, sampled microbialite biomass were broken up and strained through a 1.5 mm stainless steel sieve to remove large particles and create a slurry of the live material. Water collected from the freshwater inflows was filtered through a nylon membrane (0.22 µm) and used as a substrate for the microbialite incubations. To ensure that the microbial community did not run out of bicarbonate during the incubation, 1 mL of the slurry (100-500 µg microbialite carbon) was added to 500 mL of filtered station water in acid washed (10% HCl) 500 mL PETG incubation bottles. Due to the remoteness of the sampling sites, samples had to be transported for ~1–2 hr before inoculation into incubation bottles. Each treatment bottle was inoculated with 400 µM 13C-labeled bicarbonate (H13CO3; 99%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). Tracer additions (10% of ambient concentrations) were estimated based on literature values of 4 mM bicarbonate in these systems26. Incubations were set up between 12:30 and 14:50 and terminated before dusk.

Samples were incubated in a microbialite barrage pool or water baths at ambient light and temperature levels for 4 hr. Since reported experiments took place during the austral summer, all daytime incubation periods occurred when ample light was available for photosynthesis. Incubations were terminated by filtering the samples onto pre-combusted (450 °C for 4 hr) 0.3 µm GF-75 filters (Advantec) under gentle (5 psi) vacuum filtration using acid washed (hereafter meaning submerged in 10% HCl for ~24 h followed by at least six rinses with type 1 ultrapure water) 25 mm polysulfone filtration funnels (Pall Corporation). Once on the filter, samples were rinsed with unamended, filtered site water (under vacuum) to wash away unincorporated isotope. Separate dedicated funnels and filtration systems were used to produce filtered site water and to collect samples to determine the natural proportion of 13C in the microbialites at each site. Filters were stored at −20 °C in sterile microcentrifuge tubes until they were dried at 40 °C overnight and analyzed on a Sercon Integra2 isotope ratio mass spectrometer.

The atom percent (atom %) enrichment, the proportion of the total carbon mass that is 13C, of the microbialite mass used in the incubations is 1.0975 for CR, 1.0975 for SK, 1.0970 for OV 745 and 1.0981 for TP. For reference, 13C exists in nature at 1.11%, therefore all samples showed clear and consistent concentrations similar to the expected natural abundance. Any bicarbonate released from the microbialite slurry would have diluted our additions, deflating the actual rates and thus making our estimates even more conservative. This is shown through the use of no-addition controls, prepared from the same slurry, incubated for the same amount of time in the same water but did not receive any H13CO3. The average specific uptake rate for controls treatments was a negligible -0.0001 hr-1.

2019: For the tracer experiment, half-core sections were broken up and strained through a 1.5 mm stainless steel sieve to remove large particles and create a slurry of the live material. To confirm that the use of a slurry did not artificially inflate or deflate rate evaluations, we compared the rates of whole (intact) versus slurry microbialite preparations. This effort revealed no significant difference in specific uptake rates between crushed-slurry and whole microbialite source material (p = 0.4; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Water collected from the freshwater inflow was filtered (0.2 µm) and used as a substrate for the microbialite incubations. The slurry was divided between nine incubation bottles for nighttime experiments and eight incubation bottles for daytime experiments that included two non-labeled controls, one HgCl2-killed control (taken only at night) and three dual labeled algal amino acid treatments (not reported here). Thus, the core area per bottle ranged from 6.3 mm2 to 9.5 mm2 depending upon the number of bottles per experiment (Supplementary Data 1). The portions of samples used in night-time experiments were incubated in filtered site water without tracer additions during the day and then divided between night-time assays before the addition of tracer. Abiotic controls were supplemented with 200 µl of a HgCl2 saturated solution to cease microbial growth allowing for the determination of chemical carbonate precipitation. Each treatment was inoculated with 13C labeled H13CO3− as described above (99%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). All daytime experiments were started by 11:25 am. Night-time experiments started at midnight and incubated in a barrage pool at ambient light and temperature levels for 4 hr. Incubations were terminated by filtering the samples onto pre-combusted 0.3 µm GF-75 filters (Advantec) to collect the tracer enriched biomass. Night-time assays were filtered in the dark before dawn. Temperatures fluctuated in the barrage pool by ~5 °C over the full diel cycle. Filters were stored at -20 °C in sterile microcentrifuge tubes until they were dried at 40 °C overnight and analyzed on a Sercon Integra2 isotope ratio mass spectrometer.

Experiments in 2022 were conducted to assess the proportion of bicarbonate uptake that is incorporated into the inorganic vs organic fraction to assess accretion rates. All methods were the same as those used in 2018 except that these samples were incubated for a full 24 h to obtain net C incorporation.

Rate calculations

Bicarbonate uptake rates were calculated following standard stable isotope tracer methods described in Hama et al. 43 and refined by Collos and Slawyk (1985)44. An extensive study of groundwater chemistry for the region had been conducted by Dodd et al. 26, recording HCO3− concentrations ranging from 4096 µM to 4597 µM for stromatolite inflows. The lowest reported averages (4 mM) of freshwater DIC for these systems26 were used in our calculations to ensure that we did not overestimate C uptake, therefore, the presented rates should be considered a realistic but potential underestimation. The ratio of microbialite mass to water volume (< 1 µg stromatolite C per ml site water) was intentionally low to ensure that bicarbonate would not become depleted. For this study, two different rates were calculated, specific and absolute carbon uptake. For clarity, specific uptake rates are expressed in units of time and are comparable to growth rates. Absolute uptake rates should be interpreted as the amount of time for a specific substrate (HCO3−) to be taken up by a target community in units of carbon per volume (here, converted to mass or area) per unit of time. Specific and absolute uptake rates were calculated as follows:

where v is specific uptake rate (h−1), ρ is absolute uptake rate (g C m−2 h−1), and atom percent (at%) is the percentage of carbon atoms that are 13C.

Atom % excess (at% xs) refers to the percentage of 13C atoms in excess of the natural abundance in the particulate carbon (PC) sample (atom % of PC after incubation minus the atom % of the initial/ ambient PC). DIC (dissolved inorganic carbon) at% xs is the percentage of 13C atoms added with the addition of the 13C labeled HCO3− substrate, the 13C in excess of the natural abundance (atom % of DIC source pool after addition–atom % of the initial/ ambient PC). PC stands for particulate carbon but in the case of [PC] this refers to the mass of particulate carbon (Supplementary Data 1). In 2019, 17 mm × 10 mm cores, with a surface area of 227 mm−2, were divided among replicate bottles, averaging 7.5 mm−2, allowing absolute uptake rates to be calculated based on the surface area and proportion of the core used in replicate studies (Supplementary Data 1). The accretion rate (mm m-2) was estimated based on the total amount of 13C labeled HCO3− that was incorporated into the inorganic (87%) versus organic C fractions (Supplementary Data 1). Differentiation between inorganic and organic fractions was accomplished using the acid fumigation method45. The rate of bicarbonate uptake within the inorganic fraction (Supplementary Fig 3.) was used to confirm movement/precipitation of captured C into the particulate inorganic pool. Composition and porosity from CR22 were used to obtain maximal annual growth estimates detailed below.

C accretion in mineralized parts of microbialites

Stromatolites exhibited varying abundances of pore space, detrital silicates, and biogenic precipitates of calcium phosphate and calcite. Their relative proportions were determined from back scattered electron (BSE) images, on which different phases and pore space show different signal intensities (e.g., calcite white, pore space black, Ca phosphate dark gray, silicate detritus variably light gray). BSE images were converted into 8-bit grayscale images. Using the gray-scale Threshold tool of the ImageJ 1.53k software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij), domains of uniform BSE signal intensity can be selected and converted into area proportions. We determined phase and pore space abundances for seven selected domains from four CR samples (Fig. 7A). Detailed sample descriptions and phase analysis can be found in Büttner et al. 22.

Combining the phase proportions with the known phase compositions22 and phase densities, the CO2 proportion in the bulk sample can be calculated using the Rock Maker software46 (Supplementary Data 2). The software converts the weight percentage of each oxide compound and the abundance of each phase into proportional totals of each oxide species, from which the bulk composition of the whole rock can be obtained by normalization. From the CO2 weight percentage of the whole rock, the weight percentage of carbon (Fig. 7B) was obtained by molar weight conversion. Our calculations assume water-filled pore space. The carbon content of the analyzed stromatolite precipitates increases from 7.3 wt% (average of all data) to 9.4 wt% if the pore space is filled with air. Pore-free calcite has a carbon content of 12 wt%. The relevant parts of the Rock Maker software showing all calculation steps in spreadsheet cell references and the obtained results are available as electronic Supplementary Data 2. Further detail on the elemental content calculations is provided in the associated publication46. Annual growth/ accretion estimates (Supplemental Spreadsheet 1, column AI) are presented in mm per year and were calculated as the annual C mineralization (Kg C m−2 yr−1) divided by the average C content per mm m−2 [161 Kg C m−3 (Fig. 7 and described in Supplemental Spreadsheet 2) divided by 1000 to convert into mm sections over m−2 areas], providing maximal annual growth/ accretion estimates in mm yr−1.

Nutrient analyses

Filtered (0.3 µm GF-75) nutrient samples were stored frozen until analysis. All samples were analyzed in triplicate and are reported as the average ± the standard deviation. Ammonium concentrations were measured using the phenol-hypochlorite method47. Nitrate, NO2− and PO43− concentrations were measured on a Lachat QuikChem 8500 autoanalyzer48. Total dissolved nitrogen (TDN) and dissolved organic C (DOC) concentrations were measured by high-temperature combustion on a Shimadzu TOC-V TNM autoanalyzer49 and instrument calibration was verified using the consensus reference material program at the University of Miami (http://yyy.rsmas.miami.edu/groups/biogeochem/CRM.html). Dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) was calculated by subtracting dissolved inorganic nitrogen (NH4+, NO3−, and NO2−) from TDN.

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from microbialite samples using the Zymo quick-DNA™ fecal/soil microprep kit (Catalog No. D6012) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was extracted from ~500 mg of microbialite material, yielding between 2–4 μg of gDNA. PCR amplification of template DNA was performed as described in Waterworth et al. 27. Samples were sequenced on the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB) Aquatic Genomics Research Platform (AGRP) Illumina Miseq platform, generating ~250 nt amplicon libraries (only forward reads were of a sufficient quality to use in analysis). Data curation was performed using the mothur software platform50 as in Waterworth et al. 27. The 50 most numerically abundant OTUs were used for analysis (Fig. 3B).

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing

gDNA was sequenced using the Ion-Torrent Proton P1 sequencing platform at the Central Analytical Facility of the University of Stellenbosch (Supplementary Taable 6). Metagenomic data was assembled into contiguous sequences with the SPAdes assembler (version 3.12.0)6using the “-iontorrent” and “-only-assembler” options with default kmer values. Scaffolds were classified at kingdom level using Autometa51 and extracted using custom Python script pull_bacterial_contigs.py. Genes were identified in bacterial scaffolds with Prodigal and annotated against the KEGG database using KOFamScan. Reliable KEGG annotations (score > threshold) were extracted and counted per sample using custom Python script strict_kegg_parser.py. In all samples, total identified genes were counted and used to correct KEGG-annotated gene counts to relative gene abundance per sample. Finally, putative taxonomic origin of each annotated gene was assigned using Autometa classifications and counted to determine from which bacteria different metabolisms may stem from. This was achieved using the kegg_tax_count.py script. All scripts for analysis and visualization of this data can be found in the GitHub repo: (https://github.com/samche42/C_uptake_manuscript).

Statistical analysis

The open-source RStudio program (version 0.99.490) was used for all statistical tests. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check whether data were normally distributed; data that were not normally distributed were log-transformed prior to further statistical analyses. Statistical differences were determined using ANOVAs followed by post-hoc Tukey’s tests to determine if the means from different treatments were significantly different from one another. Treatments were considered significantly different if the p value was ≤0.05.

X-ray powder diffraction spectroscopy

X-ray powder diffraction patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Discover XRD system housed at the Tebello Nyokong Institute for Nanotechnology Innovation at Rhodes University. The instrument is equipped with a proportional counter, using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å, nickel filter). Data were collected in the range from 2θ = 10° to 60°, scanning at 1.5° min−1 with a filter time-constant of 0.38 s per step and a slit width of 6.0 mm. Samples were placed on a plastic powder specimen holder. The X-ray diffraction data were treated using the Eva (evaluation curve fitting) software. Baseline correction was performed on each diffraction pattern by subtracting a spline function fitted to the curved background.

Data availability

The unassembled metagenomic data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI database under bioproject PRJNA706574 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) and assembled metagenomic data can be accessed on MG-RAST under the accession numbers mgm4790047.3, mgm4790043.3, mgm4784267.3, mgm4784118, mgm4876328.3, mgm4876691.3 and mgm4876904.3. 3. 16S rRNA amplicon library data can be accessed on NCBI under the bioproject PRJNA611746. C uptake and CO2 data and calculations are provided as Excel Spreadsheets in the Supplementary Data 1 and 2.

References

Knoll, A. H., Bergmann, K. D. & Strauss, J. V. Life: The first two billion years. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 371, 20150493 (2016).

Wilmeth, D. T. et al. Environmental and biological influences on carbonate precipitation within hot spring microbial mats in Little Hot Creek, CA. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1464 (2018).

Bosak, T., Knoll, A. H. & Petroff, A. P. The meaning of stromatolites. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 41, 21–44 (2013).

Riding, R. et al. The nature of stromatolites: 3500 million years of history and a century of research. In Advances in stromatolite geobiology. 29–74. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011).

Copley, S. D., Smith, E. & Morowitz, H. J. The origin of the RNA world: co-evolution of genes and metabolism. Bioorg. Chem. 35, 430–443 (2007).

Paterson, D. M. et al. Light-dependent biostabilisation of sediments by stromatolite assemblages. PLoS One 3, 3176 (2008).

Dupraz, C. et al. Processes of carbonate precipitation in modern microbial mats. Earth-Sci. Rev. 96, 141–162 (2009).

Wong, H. L. et al. Disentangling the drivers of functional complexity at the metagenomic level in Shark Bay microbial mat microbiomes. ISME J. 12, 2619 (2018).

Buick, R. The antiquity of oxygenic photosynthesis: evidence from stromatolites in sulfate-deficient Archaean lakes. Science 255, 74–77 (1992).

Flannery, D. T. et al. Spatially-resolved isotopic study of carbon trapped in ∼3.43 Ga Strelley Pool Formation stromatolites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 223, 21–35 (2018).

Ruvindy, R., White, R. A. III, Neilan, B. A. & Burns, B. P. Unravelling core microbial metabolisms in the hypersaline microbial mats of Shark Bay using high-throughput metagenomics. ISME J. 10, 183 (2016).

Bauld, J., Chambers, L. A. & Skyring, G. W. Primary productivity, sulfate reduction and sulfur isotope fractionation in algal mats and sediments of Hamelin Pool, Shark Bay, WA. Mar. Freshw. Res 30, 753–764 (1979).

Reid, R. P., Foster, J. S., Radtke, G. and Golubic, S. Modern marine stromatolites of Little Darby Island, Exuma Archipelago, Bahamas: Environmental Setting, Accretion Mechanisms And Role Of Euendoliths. In Advances In Stromatolite Geobiology. 77–89. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2011).

Casaburi, G., Duscher, A. A., Reid, R. P. & Foster, J. S. Characterization of the stromatolite microbiome from Little Darby Island, The Bahamas using predictive and whole shotgun metagenomic analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1452–1469 (2016).

White, R. A. III, Power, I. M., Dipple, G. M., Southam, G. & Suttle, C. A. Metagenomic analysis reveals that modern microbialites and polar microbial mats have similar taxonomic and functional potential. Front. Microbiol. 6, 966 (2015).

Kaźmierczak, J. et al. CaCO3 precipitation in multilayered cyanobacterial mats: clues to explain the alternation of micrite and sparite layers in calcareous stromatolites. Life 5, 744–769 (2015).

Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions - Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

Zeyen, N. et al. Integrative analysis of the mineralogical and chemical composition of modern microbialites from ten Mexican lakes: What do we learn about their formation? Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 305, 148–184 (2021).

Caumartin, J. et al. The chemical conditions necessary for the formation of microbialites. Geochemical Perspect. Lett. 25, 30–35 (2023).

Smith, A. M. et al. Rock pool tufa stromatolites on a modern South African wave-cut platform: partial analogues for Archaean stromatolites? Terra Nova 23, 375–381 (2011).

Smith, A. et al. The extant shore platform stromatolite (SPS) facies association: a glimpse into the Archean? Biogeosciences 15, 2189–2203 (2018).

Büttner, S. H. et al. Living phosphatic stromatolites in a low-phosphorus environment: implications for the use of phosphorus as a proxy for phosphate levels in paleo-systems. Geobiology 19, 35–47 (2021).

Rishworth, G. M. et al. Functional drivers, value and trajectories of modern supratidal microbialites fed by groundwater. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103364 (2020).

Perissinotto, R. et al. Tufa stromatolite ecosystems on the South African south coast. SAJS 110, 01–08 (2014).

Rishworth, G. M. et al. Environmental influences on living marine stromatolites: Insights from benthic microalgal communities. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 503–513 (2016).

Dodd, C., Anderson, C. R., Perissinotto, R., du Plooy, S. J. & Rishworth, G. M. Hydrochemistry of peritidal stromatolite pools and associated freshwater inlets along the Eastern Cape coast, South Africa. Sediment. Geol. 373, 163–179 (2018).

Waterworth, S. C., Isemonger, E. W., Rees, E. R., Dorrington, R. A. & Kwan, J. C. Conserved bacterial genomes from two geographically distinct peritidal stromatolite formations shed light on potential functional guilds. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 13, 126–137 (2021).

Campbell, E. E. & Bate, G. C. Ground water in the Alexandria dune field and its potential influence on the adjacent surf-zone. Water SA 17, 139–146 (1991).

Cullen, J. J. Primary production methods. Encycl. ocean Sci. 11, 2277–2284 (2001).

Beer, S., Björk, M. and Beardall, J. Carbon Dioxide Vs. Bicarbonate Utilisation. In Research Methods Of Environmental Physiology In Aquatic Sciences. 153-164. Singapore: Springer Singapore (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Carbon fixation by photosynthetic mats along a temperature gradient in a Tengchong hot spring. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 125, 2020JG005719 (2020).

Steppe, T. F., Pinckney, J. L., Dyble, J. & Paerl, H. W. Diazotrophy in modern marine Bahamian stromatolites. Microb. Ecol. 41, 36–44 (2001).

Amoroso, G., Sültemeyer, D., Thyssen, C. & Fock, H. P. Uptake of HCO3- and CO2 in cells and chloroplasts from the microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Dunaliella tertiolecta. Plant Physiol. 116, 193–201 (1998).

Rubio, L. et al. Direct uptake of HCO3− in the marine angiosperm Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile driven by a plasma membrane H+ economy. Plant, Cell Environ. 40, 2820–2830 (2017).

du Plooy, S. J., Rishworth, G. M., Perissinotto, R. & Dodd, C. 2020. Nutrient uptake and primary production in lithifying peritidal tufa stromatolites. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 525, 151314 (2020).

Kupriyanova, E. et al. Extracellular carbonic anhydrases of the stromatolite-forming cyanobacterium Microcoleus chthonoplastes. Microbiol 153, 1149–1156 (2007).

Pace, A. et al. Formation of stromatolite lamina at the interface of oxygenic–anoxygenic photosynthesis. Geobiol 16, 378–398 (2018).

Martin, W. F. Hydrogen, metals, bifurcating electrons, and proton gradients: the early evolution of biological energy conservation. FEBS Lett. 586, 485–493 (2012).

Schuler, C. G., Havig, J. R. & Hamilton, T. L. Hot spring microbial community composition, morphology, and carbon fixation: implications for interpreting the ancient rock record. Front. Earth Sci. 5, 97 (2017).

Power, I. M., Wilson, S. A., Dipple, G. M. & Southam, G. Modern carbonate microbialites from an asbestos open pit pond, Yukon, Canada. Geobiol 9, 180–195 (2011).

Planavsky, N. & Ginsburg, R. N. Taphonomy of modern marine Bahamian microbialites. Palaios 24, 5–17 (2009).

Chivas, A. R., Torgersen, T. & Polach, H. A. Growth rates and Holocene development of stromatolites from Shark Bay, Western Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 37, 113–121 (1990).

Hama, T. et al. Measurement of photosynthetic production of a marine phytoplankton population using a stable 13C isotope. Mar. Biol. 73, 31–36 (1983).

Collos, Y. & Slawyk, G. On the compatibility of carbon uptake rates calculated from stable and radioactive isotope data: implications for the design of experimental protocols in aquatic primary productivity. J. Plankton Res. 7, 595–603 (1985).

Komada, T., Anderson, M. R. & Dorfmeier, C. L. Carbonate removal from coastal sediments for the determination of organic carbon and its isotopic signatures, δ13C and Δ14C: comparison of fumigation and direct acidification by hydrochloric acid. Limnol. Oceanog: Methods 6, 254–262 (2008).

Büttner, S. H. Rock Maker: an MS Excel spreadsheet for the calculation of rock compositions from proportional whole rock analyses, mineral compositions, and modal abundance. Mineral. Petrol. 104, 129–135 (2012).

Koroleff, F. et al. Simultaneous Oxidation Of Nitrogen And Phosphorus Compounds By Persulfate. In Methods of Seawater Analysis (Eds. Grosshoff K., Eberhadt M. & Kremling K.) 168-169 (Verlag Chemie, 1983).

Parsons, T. R., Maita, Y. and Lalli, C. M. A Manual Of Chemical And Biological Methods For Seawater Analysis. (Pergamon Press, 1984).

Hansell, D. A. Results and observations from the measurement of DOC and DON in seawater using a high-temperature catalytic oxidation technique. Mar. Chem. 41, 195–202 (1993).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Miller, I. J. et al. Autometa: automated extraction of microbial genomes from individual shotgun metagenomes. Nucl. Acid. Res 47, e57 (2019).

Babilonia, J. et al. Comparative metagenomics provides insight into the ecosystem functioning of the Shark Bay Stromatolites, Western Australia. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1359 (2018).

Andersen, D. T., Sumner, D. Y., Hawes, I., Webster-Brown, J. & McKay, C. P. Discovery of large conical stromatolites in Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Geobiology 9, 280–293 (2011).

Breitbart, M. et al. Metagenomic and stable isotopic analyses of modern freshwater microbialites in Cuatro Ciénegas, Mexico. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 16–34 (2009).

Lim, D. S. et al. Limnology of Pavilion Lake, BC, Canada. characterization of a microbialite forming environment. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 173, 329–351 (2009).

Suosaari, E. P. et al. New multi-scale perspectives on the stromatolites of Shark Bay, Western Australia. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grants from the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) to R.A.D. (NRF GUN 87583; 109680), R.A.D. and T.G.B. (NRF GUN 11612) and the Canada-South Africa Bilateral Mobility Grant for Research Chairs from the International Development and Research Center to R.E.S. (108573-005). E.I.W. and R.-L.A.G. was supported by NRF fellowships (NRF UID 87583), while S.C.W. and X.S.-N. were supported by funding awarded to R.A.D. by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Grant number 6920). The authors acknowledge the South African Center for High Performance Computing (CHPC) for CPU time used to analyse 16S rRNA amplicon library data. The authors thank Gwynneth Matcher (SAIAB) for supporting the analysis of amplicon sequencing data, and Quinn Roberts at the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences and Bigelow Analytical Services at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences for IRMS analysis. The Shallow Marine and Coastal Research Infrastructure is thanked for research infrastructure support. Jonathan Britton (Rhodes University) is thanked for executing the XRD analysis. The authors acknowledge the use of infrastructure/equipment provided by the NRF-SAIAB AGRP and the funding channeled through the NRF-SAIAB Institutional Support System and also acknowledge computational resources and assistance of the UW-M Center for High Throughput Computing in the Department of Computer Sciences. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not attributed to any of the above-mentioned donors. All sampling was conducted under active permits, issued by the South African National Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and the Department of the Environmental Affairs (RES2018/44 and RES2019/31) and the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (RES2022/70) issued to R.A.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.E.S., E.W.I. and R.A.D. conceptualized the study. R.E.S., E.W.I., S.C.W., S.H.B., T.G.B., R.-L.G., X.S.N., S.V. and R.A.D. were involved in sample and data collection. R.E.S., E.W.I., S.C.W., S.H.B. and R.A.D. analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing and revision of the manuscript. This work was funded by grants to R.A.D., R.E.S. and T.G.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Daniel Kurth, Amanda Oehlert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sipler, R.E., Isemonger, E.W., Waterworth, S.C. et al. Integration of multiple metabolic pathways supports high rates of carbon precipitation in living microbialites. Nat Commun 17, 11 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66552-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66552-8