Abstract

Dielectric waveguides are an emerging platform for terahertz (THz) integrated circuits, but a key challenge for dense integration is the realization of terminations that enable both multi-port device characterization and elimination of electromagnetic interference. Here, we demonstrate a compact, broadband termination by coating silicon waveguides with ultrathin single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) films. Fabricated via a floating-catalyst (aerosol) chemical vapor deposition process, film thicknesses vary from 2 to 53 nm and are characterized in 140-220 GHz. A 53 nm thick film introduces up to 47 dB of attenuation while maintaining over 20 dB reflection loss, confirming nearly reflection-free absorption. Shielding analysis shows absorption dominates over reflection, and a record specific shielding efficiency of 5.5 × 109 dB cm2 g−1 is achieved. This approach offers a footprint-efficient solution for high-density THz circuits without bulky, radiative terminations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dielectric waveguides have emerged as a leading platform in terahertz (THz) and sub-THz bands, owing to their intrinsically low-loss propagation, strong mode confinement, and compatibility with CMOS fabrication processes1,2,3. In particular, high resistivity float-zone intrinsic silicon is virtually lossless in the THz range, offers a high refractive index contrast (nSi = 3.42) for tight modal confinement and sharp bending, and can be patterned with nanometer precision using mature, high volume CMOS foundry techniques, enabling monolithic integration4. Moreover, the surface wave modes supported by open dielectric waveguides have a significant fraction of their electromagnetic energy residing in the evanescent field extending to their cladding, making them inherently sensitive to changes in the surrounding environment5,6,7. This property is ideal for on-chip sensing8 and evanescent coupling9. Various all-silicon platforms have been proposed, with recent advances including silicon photonic crystal waveguides that exploit engineered bandgaps10, effective medium cladding waveguides that tailor dispersion via subwavelength patterning11, unclad waveguides that are entirely cladded by the ambient air12, topological waveguides13 that offer extremely sharp bends, and others. Together, these platforms pave the way towards fully integrated THz circuits14,15.

A key challenge in complex THz networks on these platforms is the realization of well-matched terminations. Without proper termination, reflections at device discontinuities can cascade, degrading performance and altering the intended operation profile. Additionally, terminations are necessary for characterization of multi-port devices, such as directional couplers, where the unused ports must be terminated with matched loads. The conventional solution employed is usually an adiabatic or impedance-matched tapering of the waveguide cross-section to free space, gradually expanding the guided mode to induce radiation losses, operating as a dielectric rod antenna16. However, the efficiency of these structures depends on the length of the tapering, therefore consuming valuable chip area, and can radiate power into undesirable directions, complicating packaging, limiting integration density and creating electromagnetic pollution. Moreover, such tapers introduce points of mechanical fragility: the thin tips are prone to chipping or fracture during handling and packaging, which can permanently degrade circuit performance17.

Since many of the conventional microwave approaches for terminations do not scale down well to THz systems for a variety of reasons (such as thermal incompatibility of materials with standard CMOS processes, or fabrication complexity for realizing tapered geometries in microscales), a number of novel nanocomposites have gained significant interest for their absorption properties in the THz regime, such as graphene-based composites18,19, Mxene composites20,21, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)22,23, among others.

In particular, single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) films, with their exceptional electrical conductivity and tunable optoelectronic properties, have been used in a variety of THz devices, such as varactors24, modulators25, detectors26, polarizers27, arrays of spiral zone plates28, and others. Additionally, CNTs have demonstrated excellent absorption capabilities, from the microwave up to the visible regime29,30,31. In most of these studies however, the CNT-based absorbers are used either inside a hollow waveguide or in a free-space spectroscopic configuration. Studies in the infrared region have demonstrated interaction of SWCNT with guided waves in SWCNT-coated dielectric waveguides for saturable absorbers32,33. However, it is unclear whether these materials are effective absorbers of surface-wave modes propagating in a THz dielectric waveguide, where only part of the guided field overlaps with the films. Our approach targets directly these dielectric waveguide modes in low THz frequencies.

In this work, we introduce an ultracompact termination strategy based on polymer-free SWCNT thin films, produced via aerosol chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and dry-transferred onto silicon dielectric rod waveguides (DRW). SWCNT networks exhibit broadband absorption well into the THz regime, with tunable surface conductivities via film thickness control. By coating the waveguide with SWCNT films, we achieve strong, localized attenuation of the surface-guided wave without significantly altering the waveguide geometry or footprint. This approach preserves the high-index contrast and modal confinement of the silicon platform, while providing a broadband, reflection-free termination element that is orders of magnitude more compact than conventional tapers.

Results and discussion

Material and Structural Characterization

SWCNT thin films with optical transmittance values (at 550 nm) of 98%, 96%, 94%, 87%, 79%, and 60% were prepared. Hereafter, each sample will be referred to by its measured optical transmittance at 550 nm. According to34 the thickness of the corresponding SWCNT films can be estimated as approximately 2, 4, 6, 14, 24, and 53 nm, respectively. Figure 1 presents representative structural characterization data drawn from typical SWCNT films in this series. The thin films contain predominantly single-walled carbon nanotubes as directly observed with transmission electron microscopy (TEM; number of walls, Fig. 1c) as well as ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared spectroscopy (UV-Vis-NIR; appearance of the transitions between van Hove singularities, Fig. 1a) and Raman spectroscopy (the presence of radial breathing modes (RBM) characteristic to SWCNT; Fig. 1b). Graphitic sp2-carbon structure manifests itself via the presence of a π-plasmon (Fig. 1a) and a characteristic G mode (Fig. 1b), while the low intensity of a D mode (Fig. 1b; IG/ID=41) verifies low concentration of defects and the high-quality of the produced samples. The films are formed by individual SWCNTs and their agglomerates (bundles; Fig. 1c), while the catalyst remains within the film without any effect on transparency in the visible light range or the conductivity35. The individual nanotubes and their bundles form a randomly-oriented highly porous network, as revealed by scanning electron microscopy, (SEM; Fig. 1d) with uniform spatial distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1b). A more detailed structural characterization of the thin SWCNT films employed here has been carried out in36,37.

Electromagnetic Characterization

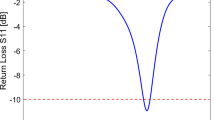

The magnitude of the measured S-parameters of the SWCNT-loaded DRWs are given in Figs. 2, 3, along with an unloaded DRW for reference. The unloaded DRW has an average insertion loss of 0.7 dB across the band, indicating good coupling with the feeding hollow waveguides. Adding the SWCNT films yields extra losses that increase monotonically with thickness, spanning from an average of 3 dB across the band for the thinnest SWCNT-98% (2 nm) sample to an average of 47 dB for the thickest SWCNT-60% (53 nm) sample of 6 mm in length. As expected, the losses also increase with longer SWCNT films, with the corresponding SWCNT-60% sample approaching the noise floor towards the upper half of the band.

Reflection loss (Fig. 3) of the SWCNT-loaded DRWs is very close to that of the unloaded silicon DRW, indicating a good impedance matching and therefore pure attenuation with no extra reflection back to the feeding waveguides, which is particularly important for any absorbing material. Small peaks in ∣S11∣ (e.g. sample SWCNT-87%, 12 mm long) are due to sub-optimal manual alignment between the DRW and the hollow metallic waveguide. The qualified bandwidth, defined as the frequency range for which ∣S11∣ < − 10 dB, covers the entire 140-220 GHz band. Overall, the S-parameters indicate no particular selectivity in frequency for the targeted range, displaying a fractional bandwidth of 44.4%.

The shielding efficiencies of the SWCNT samples are calculated according to38:

and are given in Fig. 4. We observe the primary shielding mechanism to be the absorption, since SER remains sufficiently low across the whole frequency band. Table 1 gives the average reflection and total shielding efficiencies across the band, showing that the average reflection shielding efficiency is between 0.004 dB and 0.05 dB for all samples, while that of an unloaded DRW is 0.02 dB. Additionally, the average across the band total shielding efficiency is above 50 dB and 60 dB for the SWCNT-79% and SWCNT-60% (12 mm long) films, respectively, indicating excellent shielding through absorption.

Similar lossy SWCNT film-covered dielectric waveguides have been proposed before in39,40,41. However, the attenuation was significantly lower than the one presented here. This is because the SWCNT films are now placed parallel to the E-field. Since the \({E}_{11}^{y}\) mode is excited, the main components of the E-field are Ey and Ez (with reference to the axis of Supplementary Fig. 1a), with Ex being significantly weaker and localized at the corners of the waveguide. Therefore, strong surface currents Js = σsEt are induced (where σs the surface SWCNT complex conductivity and Et the tangential electric field at the wide wall of the DRW where the SWCNT films are deposited). In order to calculate the surface conductivity of each sample, a perturbation approach might be followed42. Assuming a single-mode operation and that the loss is primarily ohmic and attributed to the presence of the SWCNT films, the latter can be approximated as a small perturbation to the otherwise lossless unloaded waveguide. Additionally, we assume that the SWCNT film sheet conductivity is uniform (which is confirmed by the uniformity of the samples, i.e. Supplementary Fig. 1b) and neglect its reactive part (assuming SWCNT films introduce only attenuation). The ohmic power loss per unit length due to the presence of the SWCNT films is given by42:

where Rs is the sheet resistance of the SWCNT films and the contour integral runs across the SWCNT films in a transverse cross-section of the waveguide. Since power loss per unit length is PL = 2αP0, with P0 the excitation power and α the attenuation constant, then

where the tangential E-field component is approximated by that of the unloaded DRW. The attenuation constant can be calculated experimentally by \(\alpha=\frac{1}{2L}{{\mathrm{ln}}}\frac{1-| {S}_{11}{| }^{2}}{| {S}_{21}{| }^{2}}\) (Np/m), where L the length of the SWCNT film along the propagation direction.

The tangential E-field component of the unloaded DRW was obtained through full-wave simulations in CST Microwave Studio, and then the extracted sheet resistance was used to simulate a surface impedance boundary on the top of the DRW. Polynomial fitting was used to fit the extracted sheet resistance to the boundary values in CST. In these simulations, the transitions from the hollow metallic waveguides of the frequency extenders to the DRW were included. Figure 5a, b shows the simulated S-parameters for 4 representative samples (SWCNT-98%, SWCNT-96%, SWCNT-94% and SWCNT-79%, 6 mm long) next to the corresponding measured ones. The extracted THz sheet resistance used for the simulations is also given in Fig. 5c, while Fig. 5d shows the DC sheet resistance, measured using a 4-probe method. Although the simulated S-parameters follow the same frequency dependence and relative ordering of the samples, they overestimate the average (across the band) insertion loss by 0.8 dB, 1.8 dB, 2.2 dB and 6.1 dB for the samples SWCNT-98%, SWCNT-96%, SWCNT-94% and SWCNT-79%, respectively. Naturally, the perturbation approach is more accurate for the thinnest samples and less accurate for the thicker ones. Figure 6 shows the simulated electric field magnitude propagating across the loaded DRWs for the same samples, illustrating the attenuation in the SWCNT region.

a Measured (dashed lines) and simulated (solid lines) ∣S21∣ for the samples SWCNT-98%, SWCNT-96%, SWCNT-94%, SWCNT-79% of 6 mm length. b Measured and simulated ∣S11∣ for the same samples. c The corresponding THz sheet resistance extracted using a perturbation approximation. d Measured DC sheet resistance.

The bulk density of the samples was evaluated before43 using extremely precise balances of up to 1 μg precision and calculated as 1.6 ± 0.5 mg/cm3. The specific shielding efficiency (SSE), defined as SE/(ρt), with t the thickness and ρ the density of the material, is calculated as 5.5 × 109 dB cm2 g−1, an unprecedented level showcasing the excellent performance of the ultrathin SWCNT absorbers. Table 2 shows the comparison of key performance figures between the absorber of this work (with reference to the SWCNT-60%, 6 mm long sample) and other selected state of the art shielding materials reported in the literature.

Methods

Sample preparation

Thin films of single-walled carbon nanotubes were produced using a specific case of a floating catalyst CVD with an extreme dilution of a catalyst–the aerosol CVD method37. The aerosol CVD reactor mainly comprised a quartz tube with a diameter of 72.5 mm and a length of 1,300 mm equipped with a three-zone furnace with a length of 1,000 mm to provide ca. 700 mm isothermal zone with a T of 854 ∘C. We employed the Boudouard reaction (CO disproportionation) on the surface of Fe-based nanoparticles to provide a catalytic growth of SWCNTs. The method provides only single-walled carbon nanotubes similar to the predominant growth of single-layer graphene44 via the Boudouard reaction45. During the routine synthesis process, the flow of carbon monoxide (99.999% Linde gas; serves as a carbon source and a carrier gas) was fed to the reactor via three routes: a part of a flow went through a cartridge with a vapor of a volatile catalyst precursor (ferrocene, C10H10Fe, 99%, Sigma Aldrich), the second part mixed with the first one to be fed via an injector to facilitate the catalyst activation46, and, lastly, the third and the most dominant fraction of CO flow was mixed with carbon dioxide (CO2, 99.995%) as a mild etching agent to enhance growth36 was fed into the main quartz tube. When the flow enters the hot zone of the reactor, ferrocene’s transformation into an aerosol of Fe-based catalytic particles is followed by SWCNT growth. Thin films of SWCNT were collected with a simple filtration of the nanotube-containing aerosol with a nitrocellulose membrane (HAWP, Merck Millipore) to obtain a thin film of randomly oriented nanotubes for further dry transfer to any substrate47. Thickness was controlled by adjusting both the collection time and the aerosol flow through the filter.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

To investigate the SWCNT film morphology (spatial distribution, alignment, impurities), a Quattro S scanning electron microscope in secondary electron (SE) mode at a 2 kV accelerating voltage was used.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The morphology of SWCNT networks (the number of walls, their structure, and bundling degree) was observed with the FEI Tecnai G2 F20 transmission electron microscope. For the sample collection, a TEM lacey Cu-300 grid was placed on a filter, and nanotubes with the aerosol flow coming from the reactor outlet were deposited directly on a grid.

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy was employed to assess the quality of SWCNT films. Thermoscientific DXRxi Raman Imaging microscope operated at an excitation wavelength of 532 nm and a laser power of 0.1 mW.

UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-Visible-Near-infrared spectroscopy served to assess SWCNT structure (S11, S22, M11, etc. transitions between the van Hove singularities directly relate to diameter distribution), possible doping (suppression of the transitions), and film thickness (based on the absorbance at 550 nm). Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer Lambda 1050 was used to register spectra in the range of 200–1800 nm with a spectral resolution of 2 nm.

Electromagnetic Characterization

For electromagnetic characterization, a vector network analyzer (VNA, Rohde & Schwarz ZVA-24) was connected to two frequency extender units (Rohde & Schwarz ZC220) to up-convert the frequency to 140-220 GHz. Thru-Offset-Short-Match (TOSM) calibration48 was used at the flanges of the frequency extenders to correct for systematic errors. The DRWs are carefully inserted into the hollow metallic waveguides of the extenders using computer-controlled 3-axis positioner stages with micrometer accuracy. Care has been taken to align the DRW into the hollow waveguide opening and minimize generation of higher order modes49. By placing the DRW with their wide side parallel to the E-field of the hollow waveguide, the fundamental mode \({E}_{11}^{y}\) is excited7. A low-permittivity foam was used as a supporting structure to hold the DRW parallel to the feeding waveguides. Supplementary Fig. 1a shows a schematic of the DRW with the SWCNT layer on top, while Supplementary Fig. 1d shows the actual measurement setup in the lab.

The DRWs are 1 mm wide and were etched on a 200 μm high-resistivity float-zone silicon wafer using standard deep reactive ion-etching (DRIE) process. A 6 mm-long coupling spike is employed on both ends of the DRW in order to couple the THz waves from the hollow metallic waveguides of the frequency extenders. In total, the DRWs are 32 mm-long.

DC sheet resistance was measured with a Jandel RM3000 four-point probe station operated in current-source, voltage-sense mode. For each film, measurements were performed at least three times and the reported values are the average. The drive current was adjusted between 0.01 and 1 mA depending on the film conductivity.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the figshare repository under accession code: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30391714. Simulation files can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors.

Code availability

Scripts used for processing and plotting the data make use of open-source Python libraries, and can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Lioubtchenko, D., Tretyakov, S. & Dudorov, S. Millimeter-wave waveguides Vol. 114 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2003).

Carpintero, G., Garcia-Munoz, E., Hartnagel, H., Preu, S. & Raisanen, A. Semiconductor terahertz technology: devices and systems at room temperature operation (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

Nagatsuma, T., Ducournau, G. & Renaud, C. C. Advances in terahertz communications accelerated by photonics. Nat. Photonics 10, 371–379 (2016).

Headland, D., Fujita, M., Carpintero, G., Nagatsuma, T. & Withayachumnankul, W. Terahertz integration platforms using substrateless all-silicon microstructures. APL Photonics 8 (2023).

Smirnov, S. et al. Sub-thz phase shifters enabled by photoconductive single-walled carbon nanotube layers. Adv. Photonics Res. 4, 2200042 (2023).

Chicherin, D., Sterner, M., Lioubtchenko, D., Oberhammer, J. & Räisänen, A. V. Analog-type millimeter-wave phase shifters based on mems tunable high-impedance surface and dielectric rod waveguide. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 3, 533–538 (2011).

Yeh, C. & Shimabukuro, F. I. The essence of dielectric waveguides (Springer, 2008).

Stewart, G. & Culshaw, B. Optical waveguide modelling and design for evanescent field chemical sensors. Optical Quantum Electron. 26, S249–S259 (1994).

Huang, W.-P. Coupled-mode theory for optical waveguides: an overview. J. Optical Soc. Am. A 11, 963–983 (1994).

Withayachumnankul, W., Fujita, M. & Nagatsuma, T. Integrated silicon photonic crystals toward terahertz communications. Adv. Optical Mater. 6, 1800401 (2018).

Gao, W. et al. Effective-medium-cladded dielectric waveguides for terahertz waves. Opt. express 27, 38721–38734 (2019).

Headland, D., Withayachumnankul, W., Yu, X., Fujita, M. & Nagatsuma, T. Unclad microphotonics for terahertz waveguides and systems. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 6853–6862 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Terahertz topological photonics for on-chip communication. Nat. Photonics 14, 446–451 (2020).

Pousi, P., Lioubtchenko, D., Dudorov, S. & Raisanen, A. V. Dielectric rod waveguide travelling wave amplifier based on algaas/gaas heterostructure, 1082–1085 (2008).

Koala, R. A., Fujita, M. & Nagatsuma, T. Nanophotonics-inspired all-silicon waveguide platforms for terahertz integrated systems. Nanophotonics 11, 1741–1759 (2022).

Rivera-Lavado, A. et al. Planar lens–based ultra-wideband dielectric rod waveguide antenna for tunable thz and sub-thz photomixer sources. J. Infrared, Millim., Terahertz Waves 40, 838–855 (2019).

Headland, D. & Carpintero, G. Robust unclad terahertz waveguides and integrated components enabled by multimode effects and matched slot couplers. In IEEE Transactions on Terahertz Science and Technology, Vol. 15, 885–893 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. Graphene-based materials toward microwave and terahertz absorbing stealth technologies. Adv. Optical Mater. 7, 1801318 (2019).

Campion, J. et al. Ultra-wideband integrated graphene-based absorbers for terahertz waveguide systems. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2200106 (2022).

Shui, W. et al. Ti3c2tx mxene sponge composite as broadband terahertz absorber. Adv. optical Mater. 8, 2001120 (2020).

Starchenko, V. V. et al. Electrochemically and optically-switched terahertz electromagnetic interference shielding using mxenes. Phys. Rev. Mater. 9, 074008 (2025).

Xiao, D. et al. Flexible ultra-wideband terahertz absorber based on vertically aligned carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 11, 43671–43680 (2019).

Drozdz, P. A. et al. Highly efficient absorption of thz radiation using waveguide-integrated carbon nanotube/cellulose aerogels. Applied Materials Today 29, (2022).

Generalov, A. et al. Carbon nanotube network varactor. Nanotechnology 26, 045201 (2015).

Burdanova, M. G. et al. Ultrafast, high modulation depth terahertz modulators based on carbon nanotube thin films. Carbon 173, 245–252 (2021).

He, X. et al. Carbon nanotube terahertz detector. Nano Lett. 14, 3953–3958 (2014).

Zubair, A. et al. Carbon nanotube fiber terahertz polarizer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, (2016).

Radivon, A. V. et al. Expanding thz vortex generation functionality with advanced spiral zone plates based on single-walled carbon nanotube films. Adv. Optical Mater. 12, 2303282 (2024).

Singh, S. K., Akhtar, M. J. & Kar, K. K. Hierarchical carbon nanotube-coated carbon fiber: ultra lightweight, thin, and highly efficient microwave absorber. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 10, 24816–24828 (2018).

Mizuno, K. et al. A black body absorber from vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6044–6047 (2009).

Kivistö, S. et al. Carbon nanotube films for ultrafast broadband technology. Opt. Express 17, 2358–2363 (2009).

Gladush, Y. et al. Ionic liquid gated carbon nanotube saturable absorber for switchable pulse generation. Nano Lett. 19, 5836–5843 (2019).

Jeong, H. et al. All-fiber mode-locked laser oscillator with pulse energy of 34 nj using a single-walled carbon nanotube saturable absorber. Opt. Express 22, 22667–22672 (2014).

Ermolaev, G. A. et al. Express determination of thickness and dielectric function of single-walled carbon nanotube films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 231103 (2020).

Romanov, S. A., Alekseeva, A. A., Khabushev, E. M., Krasnikov, D. V. & Nasibulin, A. G. Rapid, efficient, and non-destructive purification of single-walled carbon nanotube films from metallic impurities by joule heating. Carbon 168, 193–200 (2020).

Khabushev, E. M., Krasnikov, D. V., Kolodiazhnaia, J. V., Bubis, A. V. & Nasibulin, A. G. Structure-dependent performance of single-walled carbon nanotube films in transparent and conductive applications. Carbon 161, 712–717 (2020).

Khabushev, E. M. et al. Machine learning for tailoring optoelectronic properties of single-walled carbon nanotube films. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 6962–6966 (2019).

Hong, Y. et al. Method and apparatus to measure electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency and its shielding characteristics in broadband frequency ranges. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 1098–1102 (2003).

Nefedova, I. I., Lioubtchenko, D. V., Nefedov, I. S. & Räisänen, A. V. Dielectric constant estimation of a carbon nanotube layer on the dielectric rod waveguide at millimeter wavelengths. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 63, 3265–3271 (2015).

Nefedova, I. I., Lioubtchenko, D. V. & Räisänen, A. V.Propagation constant measurements of silver nanowires, carbon nanotubes and graphene at 75–110 ghz, 640-643 (IEEE, 2014).

Nefedova, I. I., Lioubtchenko, D. V., Nefedov, I. S. & Räisänen, A. V. Conductivity of carbon nanotube layers at low-terahertz frequencies. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 6, 840–845 (2016).

Pozar, D. M.Microwave engineering: theory and techniques (John wiley & sons, 2021).

Krasnikov, D. V. et al. Ethylene-induced welding of single-walled carbon nanotube films to enhance mechanical and optoelectronic properties. Carbon 238, 120230 (2025).

Novikov, I. V. et al. Aerosol cvd carbon nanotube thin films: From synthesis to advanced applications: A comprehensive review. Adv. Mater., 2413777 https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/adma.202413777 (2025).

Grebenko, A. K. et al. High-quality graphene using boudouard reaction. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200217 (2022).

Khabushev, E. M., Kolodiazhnaia, J. V., Krasnikov, D. V. & Nasibulin, A. G. Activation of catalyst particles for single-walled carbon nanotube synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 413, 127475 (2021).

Kaskela, A. et al. Aerosol-synthesized SWCNT networks with tunable conductivity and transparency by a dry transfer technique. Nano Lett. 10, 4349–4355 (2010).

Rumiantsev, A. & Ridler, N. Vna calibration. IEEE Microw. Mag. 9, 86–99 (2008).

Smirnov, S., Xenidis, N., Oberhammer, J. & Lioubtchenko, D. V. Generation of high-order modes in sub-thz dielectric waveguides by misalignment of the transition structure. IEEE, 479–482 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Graphene-based composites combining both excellent terahertz shielding and stealth performance. Adv. Optical Mater. 6, 1801165 (2018).

Xu, S.-T. et al. Active terahertz shielding and absorption based on graphene foam modulated by electric and optical field excitation. Adv. Optical Mater. 7, 1900555 (2019).

Hong, X. et al. High-permittivity solvents increase mxene stability and stacking order enabling ultraefficient terahertz shielding. Adv. Sci. 11, 2305099 (2024).

Pavlou, C. et al. Effective emi shielding behaviour of thin graphene/pmma nanolaminates in the thz range. Nat. Commun. 12, 4655 (2021).

Lin, Z. et al. Highly stable 3d ti3c2t x mxene-based foam architectures toward high-performance terahertz radiation shielding. ACS nano 14, 2109–2117 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Cecilia Aronsson for the fabrication of the dielectric waveguides. N.X., M.R.G., D.L., and J.O. acknowledge the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (Project Number CHI19-0027). A.G.N. acknowledges Russian Science Foundation (Project Number 22-13-00436-П, synthesis and characterization of SWCNTs). This research made use of scikit-rf, an open-source Python package for RF and microwave applications.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.X. conceived the idea, curated the data and wrote the main manuscript. M.R.G. performed the THz measurements. D.K. and N.R. performed material synthesis and structural characterization. D.K. wrote the material and structural characterization part of the manuscript. A.N., J.O., D.L. supervised the project, reviewed the manuscript, acquired funding and provided resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xenidis, N., Rezaei Golghand, M., Raginov, N.I. et al. Ultrathin Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Surface Wave Absorbers for Terahertz Dielectric Waveguides. Nat Commun 16, 10868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66559-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66559-1