Abstract

Subtle changes in molecular backbone geometry impact intermolecular interactions and performance of organic solar cells. Here, three isomeric small-molecule acceptors (NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3) are investigated to reveal how different fused-ring configurations control molecular packing, electronic coupling, and film formation. Structural and spectroscopic analyses show that the linearly fused NaO1 forms a compact three-dimensional packing network with large and balanced electronic couplings (>24 meV) across multiple directions, while the more curved analogues exhibit excessive crystallization and phase segregation. In-situ optical measurements demonstrate that NaO1 promotes fast and continuous structural evolution during film formation, resulting in smooth morphology and homogeneous phase distribution. These structural and dynamic advantages facilitate efficient charge generation and transport, accompanied by reduced non-radiative energy loss, ultimately achieving an efficiency of 20.07% for non-halogenated ternary devices. Our findings highlight how fused-ring isomerism decisively governs structure–packing–performance relationships in organic solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, organic solar cells (OSCs) have achieved remarkable progress, with power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) surpassing 20%, primarily driven by continuous advancements in the molecular design and structural optimization of high-performance small-molecule acceptors (SMAs)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. As the core photoactive component in OSCs, the molecular packing behavior of SMAs plays a crucial role in determining exciton diffusion efficiency, charge carrier mobility, and the nanoscale morphology of the active layer, thereby critically influencing overall device performance16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. For example, the prototypical acceptor Y6 features a donor–acceptor (push–pull) architecture combined with tight π–π stacking (with an interplanar distance of approximately 3.3 Å), forming a three-dimensional interpenetrating network34,35,36. This structure not only enhances intramolecular charge transfer but also facilitates efficient charge transport, enabling device efficiencies exceeding 18%37,38. Notably, its derivative L8-BO further improves charge transport and reduces energy losses by optimizing the average π–π stacking distance and modulating the molecular packing mode1,5. These advances underscore that precise control over intermolecular interactions and optimization of crystalline packing are key strategies for overcoming performance bottlenecks in OSCs.

Structural isomerization has emerged as an effective strategy for modulating molecular packing in organic semiconductors, owing to its precise control over molecular conformation21,25,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. By altering side-chain branching positions (e.g., 2-ethylhexyl vs. 3-ethylhexyl), halogen substitution sites on terminal groups (e.g., ortho-, meta-, or para- positions of F/Cl), or the orientation of core substituents, researchers have been able to fine-tune intermolecular non-covalent interactions21,25,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. For example, our previous work revealed that positional changes of methyl groups significantly affected intermolecular hydrogen bonding, leading to notable differences in device performance (18.4% for Qo2 and 16.7% for Qo3) and stability between two acceptors25. In the BTIC-BO4Cl system, shifting the chlorine atom from the γ- to the δ-position enhanced intermolecular π⋅⋅⋅π, Cl⋅⋅⋅S, and Cl⋅⋅⋅N interactions, thereby improving phase purity and charge transport characteristics in the blend films48. However, most of these studies focus on substituent-level modifications, while relatively little attention has been paid to isomerization of the fused-ring core, which can induce more pronounced structural and packing changes. Experimental studies have shown that linear and angular isomers of naphthodithiophene exhibit distinct packing motifs: linear-fused structures tend to adopt lamellar or layered stacking with stronger in-plane π–π interactions, while angular-fused analogs display tilted molecular orientations that weaken intermolecular coupling and hinder charge transport. Such backbone-level conformational control offers opportunities for the rational design of next-generation organic optoelectronic materials.

Herein, we report the rational design and synthesis of three isomeric SMAs (NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3) by modulating the fusion configuration of electron-deficient units within their central cores. These isomers exhibit distinct molecular conformations that enable a comprehensive investigation of how backbone-level isomerization affects molecular packing, electronic coupling, and device performance. Systematic characterization—including single-crystal X-ray diffraction, transient spectroscopy, grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS), and atomic force microscopy (AFM)—reveals that the linearly fused NaO1 forms a highly interconnected 3D packing network and large, balanced electronic coupling constants (>24 meV across multiple stacking modes), leading to efficient charge transport. Devices based on PM6:NaO1, processed entirely with o-xylene, achieved a high PCE of 19.11%. In contrast, the more twisted NaO2 exhibited excessive crystallinity and phase separation, resulting in a markedly lower PCE of 7.77%. Importantly, leveraging the favorable optoelectronic properties of NaO1, we further incorporated it into a non-halogenated ternary blend (PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1), which delivered a PCE of 20.07% and an enhanced fill factor (FF) of 80.3%, attributed to reduced non-radiative loss and accelerated charge transfer. These findings underscore the critical role of fused-ring isomerization in regulating molecular conformation and intermolecular packing, thereby establishing clear structure-packing-performance relationships that are essential for the rational design of high-efficiency OSCs.

Results

Material design and properties

The chemical structures of the three electron acceptors are shown in Fig. 1a, and their synthetic routes are illustrated in Fig. 1b, the Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Supplementary Data 1. Two isomeric starting materials, 2,3-dihydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]naphthalen-1-one and 2,3-dihydro-1H-cyclopenta[b]naphthalen-1-one, were oxidized with selenium dioxide to efficiently afford compounds 1 and 2. Subsequently, the BT core was reduced using lithium aluminum hydride (LiAlH4) to yield a key diamine intermediate. This diamine was then subjected to keto-amine condensation reactions with compounds 1 and 2, respectively, to construct three central cores. Notably, the condensation between the diamine intermediate and the asymmetric compound 1 could occur at either the α/β or β/γ positions, leading to two isomeric core structures. Although the two cores exhibited very similar polarities, they were successfully separated and purified by column chromatography, with an approximate product ratio of 1:3 for Core1 to Core2. Next, the three cores were subjected to formylation reactions using N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) in the presence of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) as a base, affording three distinct dialdehyde intermediates. Finally, the target SMAs were synthesized via Knoevenagel condensation. The molecular structures of NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3 were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry as detailed in the Supporting Information.

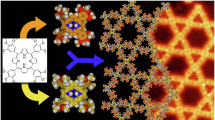

To investigate the impact of different fused-ring configurations on molecular packing behavior, single crystals of the three isomeric SMAs were obtained via recrystallization from mixed solvents. We then systematically analyzed how variations in the electron-donating arm affects their packing modes and π–π stacking distances. As shown in Fig. 2a, all three NaO-series acceptors exhibit a characteristic “banana-shaped” conformation, similar to that of Y6, primarily attributed to intramolecular S⋅⋅⋅O non-covalent interactions (NaO1, CCDC: 2463998; NaO2, CCDC: 2463999; NaO3, CCDC: 2464000) (Supplementary Data 2). The torsion angles between the central core and end groups are small and comparable across the three molecules, indicating good molecular planarity. Notably, NaO1 displays the shortest intramolecular S⋅⋅⋅O distances (2.59 and 2.61 Å), compared to NaO2 (2.67 and 2.67 Å), NaO3 (2.65 and 2.76 Å), and even Y6 (2.66 and 2.65 Å), suggesting a possible contribution from n→σ* hyperconjugation that further stabilizes the molecular conformation.

With regard to the crystal packing characteristics, the three acceptors exhibit distinctly different stacking modes, yet their π–π stacking distances are comparable, all around 3.35 Å (Fig. 2b–d). The isomer NaO1 form a tight 3D “fabric-like” network. Three distinct stacking modes are found between neighboring molecules: (1) End group-to-core arm stacking (E/C mode): In this mode, the core arm stacks with the end group as well as the thieno[3,2-b]thiophene (TT) unit, resulting in a large π-overlap and a close packing distance of 3.31 Å. (2) End group-to-bridge TT stacking (E/B mode): This configuration features a significant overlap between the end group and the TT unit in a conventional face-to-face arrangement. (3) Alternative end group-to-bridge TT stacking (E/B′ mode): While similar to the E/B mode, this stacking motif differs in the molecular orientation, exhibiting a distinct stacking angle relative to the E/B mode. This packing style is very similar to that of L8-BO reported by Sun and co-workers5, which supported its high performances. The isomer NaO2 and NaO3 possess bent core arm, enabling stronger intermolecular interactions in which multiple arms can simultaneously participate in π–π stacking. The unit cell reveals extensive molecular overlap, indicative of pronounced intermolecular interactions that give rise to robust lamellar structures and promote the formation of a two-dimensional network. Three types of stacking modes are observed: (1) E/C mode: The core arms of adjacent molecules align and interact with each other’s end groups, resulting in significant molecular overlap. This strong interaction is likely to enhance the crystallization tendency of the material. (2) E/C′ mode: An alternative end-group-to-core-arm stacking is observed, particularly in NaO2, where the TT units of neighboring molecules are misaligned. In this case, the end group of one molecule overlaps closer to the core of the neighboring molecule, rather than with its core arm as seen in NaO2. (3) E/E mode: Characteristic of Y6 derivatives, this involves end-group-to-end-group stacking. However, in the presence of other dominant interactions, this stacking becomes significantly distorted, resulting in minimal overlap between the end groups and the TT units.

Furthermore, we calculated the electronic coupling constants (|J|) for the three isomers in different stacking modes. NaO1 exhibits relatively large |J| values across all three stacking configurations (24.4 meV for the E/C mode, 24.7 meV for the E/B mode, and 26.0 meV for the E/B′ mode). In contrast, isomer NaO2 with the most curved core arm shows smaller |J| values compared to NaO1 (0.8 meV for the E/C mode, 18.7 meV for the E/C′ mode, and 23.5 meV for the E/B mode). For NaO3, although a high electronic coupling of 42.7 meV is achieved in the E/B mode, the coupling constants in the other two stacking modes remain relatively low. Compared with the bent-armed NaO2 and NaO3, NaO demonstrates large and balanced electronic couplings, which may be favorable for three-dimensional charge transport49.

To clarify the mechanism behind electronic coupling variations, we note that simple geometric/electrostatic descriptors (average core–arm dihedrals and molecular dipole moments (Supplementary Fig. 11) are similar among NaO1–NaO3 and thus cannot by themselves account for the observed differences in ∣J∣. We therefore analyzed fragment-resolved LUMO distributions for crystallographic dimers in each stacking motif (E/C, E/C′, E/B, E/B′, etc.). For each dimer, we first computed its LUMO and normalized the orbital population over the entire dimer to 100%. We then projected this dimer LUMO onto the two fragments that directly interact in each stacking motif (end-group and core-arm/bridge-TT) and denoted their LUMO shares as WLUMO(1) and WLUMO(2) (percent of the total dimer LUMO; As a compact indicator of the effective LUMO–LUMO interaction between the two fragments, we define an orbital overlap parameter SLL = WLUMO(1) × WLUMO(2). Because SLL is large only when both fragments carry appreciable LUMO density, it correlates with the calculated ∣J∣ and highlights the role of orbital registry (beyond π–π distance alone) in governing coupling.

Consistent with this picture, dimer I (E/C) in NaO2 shows near-zero ∣J∣ because one interacting fragment contributes negligible LUMO weight, whereas NaO3 dimer III (E/E) exhibits the largest ∣J∣ (42.7 meV) (Supplementary Figs. 12-14), directly correlated with the highest LUMO contributions of the two interacting fragments (18.1% and 13.7%) in NaO3 dimer III (E/E mode). In contrast, NaO1 presents moderate and balanced on both interacting fragments (end-group and core-arm/bridge units), yielding uniform ∣J∣ values (24.4, 24.7, 26.0 meV) and thus more isotropic, three-dimensional charge-transport pathways. Taken together, these results suggest that the relative distribution of LUMO density on interacting fragments—and the quality of their orbital registry—represents a major factor behind the variations in electronic coupling among NaO1–NaO3. The stronger and more balanced inter-fragment LUMO interaction in NaO1 across motifs is consistent with its large and isotropic ∣J∣ values and ultimately its good device transport characteristics.

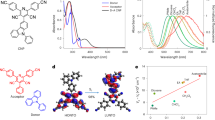

To investigate the influence of varying core-arm bending degrees on the optical and electrochemical properties of the molecules, we measured the absorption spectra of the three acceptors in o-xylene solution, as well as their absorption and electrochemical characteristics in the solid state. As presented in Fig. 3a, the three isomers exhibit nearly identical absorption profiles in solution. However, in o-xylene-treated films, NaO1 displays a significantly red-shifted absorption (Fig. 3b). To further elucidate the nature of the film absorption, the spectra in Fig. 3b were deconvoluted50,51. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the absorption profiles of NaO2 and NaO3 consist of four vibronic peaks. In contrast, the absorption spectra of NaO1 reveals five peaks upon fitting. In addition to the aforementioned four peaks, an extra peak appears at 831 nm. This further red-shifted feature is also ascribed to intermolecular aggregation, and its position implies the formation of additional highly delocalized excitonic states52,53,54,55. Such enhanced exciton delocalization originates from the 3D crystal packing structure of NaO1, which promotes stronger intermolecular electronic coupling and thus facilitates both red-shifted absorption and more efficient charge transport. In addition to the absorption peak positions, we quantitatively compared the absorption coefficients of the three isomers (Supplementary Fig. 16). In solution, the absorption coefficients are 1.08, 1.00, and 1.02 (×105 M−1 cm−1) for NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3, respectively, while in thin films the values are 1.10, 0.87, and 0.98 (×105 cm−1). These results confirm that NaO1 exhibits the strongest absorption strength in both states, which could be resulted from the enhanced exciton delocalization.

Normalized absorption spectra of NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3 in (a) dilute o-XY solution and b solid state; c CV curves of NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3 in thin films, with ferrocene (Fc/Fc⁺) as the internal reference.; d J–V curves, e EQE curves and integrated current density curves, f Photo CELIV results, g Impedance spectra, h FTPS-EQE spectra, and i EQEEL results for PM6:NaO1, PM6:NaO2, and PM6:NaO3 device.

Electrochemical measurements reveal that NaO1 exhibits lower HOMO and LUMO energy levels compared to NaO2 and NaO3 (NaO1: HOMO/LUMO = –5.62/–3.89 eV; NaO2: –5.49/–3.78 eV; NaO3: –5.60/–3.79 eV) (Fig. 3c). A lower HOMO level is beneficial for providing a larger driving force for exciton dissociation, whereas a lower LUMO level may have a negative impact on the open-circuit voltage. The trend of energy levels obtained from theoretical calculations is somewhat inconsistent with the results from cyclic voltammetry (CV), which could be attributed to the fact that theoretical calculations reflect the energy levels in isolated molecular states, while CV measurements reflect those in aggregated states. At the frequency of 105 Hz, the dielectric constants of NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3 were determined to be 2.82, 2.70, and 2.78 (Supplementary Fig. 17), respectively, confirming that the three isomers exhibit comparable dielectric properties.

Comparisons of binary photovoltaic devices and photophysical processes

Table 1 To evaluate how variations in the core arm angle of the three isomers influence device performance, we fabricated o-xylene-processed organic solar cells using a conventional architecture: ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PM6:acceptors/PFN-Br-MA/Ag. The optimized fabrication parameters are provided in the supporting information. The key device characteristics, including representative J–V curves (Fig. 3d) and performance metrics, are summarized in Table 2.

As anticipated, the NaO1-based device exhibits a lower open-circuit voltage (VOC, 0.915 V) compared to those based on NaO2 (0.953 V) and NaO3 (0.956 V). Nevertheless, it achieves a significantly higher short-circuit current density (JSC, 26.68 mA cm−2) and fill factor (FF, 0.784) than NaO2 (JSC = 11.44 mA cm−2; FF = 0.713) and NaO3 (JSC = 21.74 mA cm−2; FF = 0.745), resulting in an enhanced power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 19.11%. The considerably lower PCE of the NaO2-based device (7.77%) is primarily attributed to its suppressed short-circuit current, which likely stems from weak charge generation.

The external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectrum of the PM6:NaO1 device shows the highest photoresponse across the entire wavelength range of 300–900 nm, with peak EQE values approaching 90% (Fig. 3e), indicating efficient photon-to-electron conversion. In contrast, the PM6:NaO2 device exhibits a significantly lower EQE (below 50%) throughout the spectrum, particularly in the 600–800 nm region, suggesting poor light harvesting or charge generation. The PM6:NaO3 device shows moderate performance with an EQE curve lying between those of NaO1 and NaO2. These results are consistent with the trend observed in the JSC, confirming the better light-harvesting and charge collection abilities of the PM6:NaO1 system.

Furthermore, we evaluate the charge carrier mobility by analyzing the current response under a linearly increasing reverse bias following photoexcitation (Fig. 3f). Among the three devices, the PM6:NaO1 blend exhibits the slowest current transient and the latest peak time, indicating slower carrier extraction but a higher overall charge carrier mobility, calculated to be 1.95 × 10−4 cm2 V−1 s−1. In comparison, the PM6:NaO2 and PM6:NaO3 devices show earlier current peaks and faster decay, with mobilities of 4.95 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1 and 9.05 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1, respectively. To further validate this conclusion, we performed space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements on the binary devices (Supplementary Fig. 18). The extracted hole (μh) and electron (μe) mobilities show a similar trend: for PM6:NaO1, μh = 1.52 × 10−4 cm2 V−1 s−1 and μe = 1.03 × 10−4 cm2 V−1 s−1, indicating balanced transport; for PM6:NaO2, μh = 2.73 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1 and μe = 2.08 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1; and for PM6:NaO3, μh = 6.76 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1 and μe = 5.43 × 10−5 cm2 V−1 s−1. These results confirm that the PM6:NaO1 blend possesses both the highest absolute mobility and the most balanced μh/μe ratio, which directly supports its better charge extraction, higher FF, and overall photovoltaic performance.

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots of PM6:NaOX devices were used to analyze charge transport and recombination behavior (Fig. 3g). The series resistance (Ro), extracted from the high-frequency intercept, is lowest for PM6:NaO1 (79 Ω), compared to PM6:NaO2 (229 Ω) and PM6:NaO3 (482 Ω), indicating better ohmic contact. The charge transfer resistance (Rct), determined from the semicircle diameter, is also smallest for PM6:NaO1 (1152 Ω), suggesting more efficient interfacial charge transfer and lower recombination losses, in line with its better device performance and higher FF. Notably, the low charge mobility and conductivity are attributed to the 2D packing style, which is highly sensitive to crystal defects.

To better understand the differences in VOC among the PM6:NaOX devices, we quantitatively analyzed their energy loss components (Fig. 3h–i). Among the three cells, PM6:NaO1 exhibits the lowest total energy loss (Eloss) of 0.516 eV, primarily due to its significantly reduced radiative recombination loss (0.042 eV) below the bandgap compared to PM6:NaO2 (0.067 eV) and PM6:NaO3 (0.063 eV). In contrast, the non-radiative recombination losses (E3) are relatively similar across all devices—0.218 eV for NaO1, 0.224 eV for NaO2, and 0.222 eV for NaO3—indicating that non-radiative decay pathways are not the major source of variation in Eloss (Supplementary Table 1). This trend is supported by the electroluminescence quantum efficiencies (EQE-EL), where PM6:NaO1 shows the highest value (2.29 × 10−2) than both NaO2 (1.79 × 10−2) and NaO3 (1.93 × 10−2), confirming reduced non-radiative losses. These features collectively contribute to PM6:NaO1’s the trade-off between VOC and JSC.

Probing the blend film morphology of different binary systems

Apart from the intrinsic properties of the materials, the morphology of the active layer is also critical factor influencing the device efficiency. 2D GIWAXS and AFM were employed to investigate the molecular packing/crystallization behavior and surface morphological features, respectively. As presented in Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Table 2, these three isomeric SMAs predominantly adopt a face-on molecular orientation, which is particularly favorable for NaO1. As the single crystal data of NaO1 suggested a similar packing style to L8-BO, a similar GIWAXS patterned was also observed for neat NaO1 compared to L8-BO thin film with the signature (021) scatterings5. Its blend with the donor polymer displayed moderate crystallization tendency found in most high performance Y6 derivative blends. The minor shift in in-plane and out-of-plane scatterings in the blend compared with the neat NaO1 can be attributed to the superposition with the scattering from the donor polymer. On the other hand, the altered pack style with strong intermolecular packing rendered NaO2 and NaO2 different scattering patten style compared to most known Y6 derivatives, which agreed with single crystal data. Complex in-plane scatterings supported the various intermolecular configurations in the crystal structures. The crystal coherence length (CCL) values were extracted based on the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of scattering peaks found in the GIWAXS line cuts by fitting them to multiple peaks in Gaussian distributions and applying to Scherrer Equation (Supplementary Fig. 19). The CCL calculated for these scatterings is notably higher than that of neat NaO1. The out-of-plane π-π stacking of NaO2 and NaO3 also displayed a complex double peak at a azimuthal angle of 15o off the normal axis, further confirming the multiple mode of molecular stacking. These complex scattering patterns are also found in their blend with the donor polymer. It is noticed that the scatterings of NaO2 are significantly increased in blend with the donor polymer, displaying more higher ordered scatterings with CCL reaching 25.43 nm. PM6:NaO3 blend also displays CCL of 15.12 nm compared to 6.43 nm found in PM6:NaO1 blend. The excessively large CCL in PM6:NaO2 may result in oversized phase separation domains, reduced donor–acceptor interfacial areas, and hindered exciton dissociation, ultimately limiting device performance.

As shown in the AFM height images (Fig. 4c), the strong crystallization tendency and 2D lamellar network structures of NaO2 and NaO3 promote pronounced crystallization, as evidenced by the formation of large crystalline domains. In contrast, the PM6:NaO1 blend film exhibits the smoothest surface, with a low root mean square (RMS) roughness of 1.06 nm, indicating a more homogeneous and uniform morphology. By comparison, PM6:NaO2 and PM6:NaO3 films show increased surface roughness—5.99 nm and 1.40 nm, respectively—reflecting greater phase separation and reduced morphological uniformity. These AFM observations are consistent with the differences in CCL values among the blend films. Furthermore, infrared AFM was employed to investigate the fiber widths of the blend films (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Figs. 20–21). The average fibril diameters by using the full width at half maximum of the line-profile peaks were determined to be 19.9 nm (PM6) and 19.7 nm (NaO1) for the PM6:NaO1 blend, 58.5 nm (PM6) and 40.5 nm (NaO2) for PM6:NaO2, and 23.9 nm (PM6) and 24.7 nm (NaO3) for PM6:NaO3. Notably, the PM6:NaO1 blend features fibrils close to the optimal phase separation length scale (~10–20 nm), which is widely regarded as the most favorable for ensuring efficient exciton dissociation and continuous charge transport pathways20. This finely dispersed nanofibrillar morphology is therefore a key factor underpinning the better charge transport and the higher FF observed in the PM6:NaO1 device, while the coarser domains in PM6:NaO2 and the slightly oversized fibrils in PM6:NaO3 deviate from this optimal range and result in less efficient charge extraction.

To elucidate the structure–process–performance relationship in organic photovoltaic blends, we performed in-situ absorption spectroscopy during spin-coating, complemented by AFM and GIWAXS characterizations56. The three blend systems—PM6:NaO1, PM6:NaO2, and PM6:NaO3—exhibit distinct crystallization dynamics and morphology evolution, which closely correlate with their photovoltaic performance. In the in-situ absorption maps (Fig. 5), all three blends initially display broad and featureless spectra, corresponding to a homogeneous solution state. As spin-coating proceeds, the spectra gradually red-shift, indicating the onset of molecular aggregation and crystallization.

Among them, PM6:NaO1 exhibits a relatively fast spectral evolution, with the acceptor-related absorption band (700–800 nm) beginning to red-shift and stabilizing at approximately 2.4 s. The tracked vibronic peaks show a smooth and continuous transition for both donor and acceptor components. Although GIWAXS reveals that NaO1 exhibits the weakest crystallinity among the three systems, its AFM image indicates the smoothest surface morphology. This homogeneous film formation facilitates efficient charge transport and extraction, resulting in the highest carrier mobility, FF, and PCE among the blends. In contrast, PM6:NaO2 demonstrates the slowest crystallization dynamics, with delayed red-shift of the acceptor peaks and stabilization occurring only at around 3.1 s. The acceptor 0-0 peak in this system stabilizes near 800 nm, indicating stronger intermolecular packing and more extensive aggregation. This is corroborated by GIWAXS results, which show the highest degree of molecular ordering, and by AFM, which reveals a significantly rougher surface. Such over-crystallization likely disrupts film uniformity, leading to discontinuous charge pathways and enhanced recombination losses, ultimately yielding the lowest device performance in terms of charge mobility, FF, and PCE. PM6:NaO3 displays intermediate characteristics. Its in-situ absorption features evolve rapidly, similar to NaO1, with spectral stabilization also occurring at ~2.4 s. However, its final acceptor absorption peak settles around 800 nm, which is blue-shifted compared to NaO1 (~840 nm), probably due to its different aggregation forms. GIWAXS confirms a high level of molecular ordering, comparable to that of NaO2, while AFM reveals a moderately smooth morphology with an RMS roughness of 4.5 nm. Consequently, the device based on PM6:NaO3 delivers balanced performance in terms of charge transport and FF.

To complement the in-situ absorption results, we further monitored the structural evolution of the active layers using in-situ GIWAXS. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, NaO1 exhibited weak scattering consistent with limited crystallinity, with its crystallization occurring before that of the donor polymer. NaO2 displayed strong scattering immediately after spin coating and underwent a complex phase transformation during thermal annealing, eventually forming sharp diffraction peaks. In sharp contrast, NaO3 showed a scattering shift from 4.7 to 3.9 nm−1 during spin coating, suggesting significant structural rearrangement in the early stage of film formation. Minimal further changes were observed during annealing for NaO1- and NaO3-based blends. These distinct crystallization pathways highlight the critical role of crystallization kinetics in determining the final nanostructures, bridging the fast spectral evolution observed in in-situ absorption with the actual structural reorganization captured by GIWAXS.

To elucidate the influence of central core isomerism on exciton behavior, transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy was carried out with excitation at 500 nm to probe the electron transfer characteristics in the blend films (Supplementary Fig. 23)57. The ground-state bleach (GSB) features of both PM6 and NaOX closely matched their steady-state absorption profiles. The GSB decay kinetics of electron transfer were assessed by probing at 628 nm (Fig. 6a). While the 500 nm excitation used in TAS can excite both donor and acceptor components and thus may involve contributions from both electron and hole transfer, the decay of the donor GSB predominantly reflects the electron transfer dynamics at the donor–acceptor interface, in line with previous reports58. The corresponding biexponential lifetimes for the PM6:NaO1, PM6:NaO2, and PM6:NaO3 blends were summarized in Supplementary Table 3, with PM6:NaO1 exhibiting the shortest decay constants (τ1 = 1.43 ps, τ2 = 24.88 ps), indicating more efficient exciton dissociation and ultrafast hole transfer process. Additionally, under the excitation at 800 nm, a subsequent rise in the PM6 bleach signal at 630 nm following the decay of the NaOX acceptors (Supplementary Fig. 24), suggesting hole transfer from NaOX to PM6. Given the sub-picosecond dynamics observed in all binary blends, the fastest component (<1 ps) can be attributed to an ultrafast hole transfer process from the donor PM6 to the acceptors, enabled by their well-aligned HOMO levels and strong interfacial coupling. While this rapid channel is present in all systems, its subsequent evolution differs: in PM6:NaO1 the ultrafast hole transfer is more effectively followed by stabilized charge separation, whereas in PM6:NaO2 and PM6:NaO3 a larger fraction of carriers recombine or relax before dissociation. The time-resolved kinetics at this wavelength were further analyzed to evaluate hole transfer dynamics, revealing that PM6:NaO1 facilitated more rapid hole transfer compared to its counterparts (Fig. 6b). To further support this observation, exciton diffusion lengths (LD) of the neat acceptor films were estimated using the exciton–exciton annihilation (EEA) method57, yielding values of 30.5 nm (NaO1), 17.9 nm (NaO2), and 19.2 nm (NaO3) (Supplementary Table 4). The relatively long LD of NaO1, in combination with its favorable charge transfer kinetics, contributes to suppressed charge recombination and enhanced FF in devices, consistent with the trends observed in the TA measurements.

a Transient decay profiles of GSB at 628 nm for the blend films upon 500 nm excitation; b Transient decay profiles of GSB at 630 nm for the blend films under 800 nm excitation; c J–V curves, d EQE spectra and the integrated current density curves, e FTPS-EQE spectra, f EQEEL results, and g E3 and energy loss for L8-BO-C4-based binary device and ternary devices; The calculated reorganization energies for h NaO1 and i L8-BO-C4 during the S0 → S1 transition.

Device physics and performance optimization of ternary systems

Considering the high device efficiency and low energy loss of NaO1, we further explored its application potential in non-halogenated ternary OSCs. Using PM6:L8-BO-C41 (Supplementary Fig. 25) as the binary host system, ternary devices were constructed by incorporating NaO1 at varying L8-BO-C4:NaO1 ratios. As shown in Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 5, the PM6:L8-BO-C4 binary device achieved a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 18.76%, with a VOC of 0.881 V and a FF of 0.788. Upon gradually increasing the content of NaO1, both VOC and FF showed steady enhancement. When the ratio of L8-BO-C4 to NaO1 reached 1:1, the device delivered its best performance, with a PCE of 20.07% and an FF of 80.3%. The photocurrent derived from the integrated EQE spectrum (26.62 mA cm−2) confirmed the reliability of the J–V results (Fig. 6d). Notably, the enhancement of the EQE response in the ternary device is mainly concentrated in the donor absorption region. Transient absorption spectroscopy further corroborates this observation, showing a faster decay of donor exciton signals and a stronger growth of charge-induced absorption features in the ternary blend compared to the binary PM6:L8-BO-C4 system.

The operational stability of PM6:L8-BO-C4 and PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 devices was evaluated under three conditions: shelf storage in the dark at room temperature, continuous AM 1.5 G light soaking, and thermal aging at 85 °C (Supplementary Fig. 26). In all cases, the ternary devices exhibit significantly enhanced stability compared to the binary control. For instance, under continuous AM 1.5 G illumination, the ternary device maintains over 85% of its initial PCE after 200 h, whereas the binary counterpart decreases to ~75%. Similarly, during 85 °C thermal stress, the ternary device retains ~86% of the initial PCE after 100 h, while the binary device drops below 70%. These results clearly demonstrate that incorporating NaO1 not only improves efficiency but also effectively enhances operational stability against light and thermal stress.

To further evaluate the scalability of the material, we fabricated large-area OSC modules (aperture area of 16.80 cm² with 8 sub-cells in series, active area of 15.03 cm²) via blade coating under ambient conditions (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Table 6). The PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 ternary modules delivered a PCE of 16.93% (average 16.20 ± 0.49%), compared to 15.20% (average 14.29 ± 0.75%) for the PM6:L8-BO-C4 binary modules. The simultaneous improvements in VOC and FF highlight that the benefits of NaO1 extend from small-area devices to scalable module architectures, underscoring the practical potential of NaO1 in real-world OSC applications. Notably, the achieved efficiency of 16.93% is among the highest values reported for OSC modules at this active-area scale.

FTPS-EQE and EQE-EL measurements further revealed that the incorporation of NaO1 led to a continuous reduction in both non-radiative and total energy losses, thereby accounting for the gradual increase in VOC (Fig. 6e–g). To gain deeper insight into the impact of different central cores on non-radiative energy loss, we analyzed the reorganization energy contributions across various vibrational modes (Fig. 6h, i). In L8-BO-C4, a prominent high-frequency vibrational mode at 1604.9 cm-1—primarily associated with C–C bond stretching within the central core—was identified as a major contributor to the reorganization energy during the S0 → S1 transition. Remarkably, when the central BT unit was substituted with a fused quinoxalinone moiety in NaO1, this vibrational contribution was significantly attenuated (L8-BO-C4: 53.5 meV; T2: 30.2 meV), indicating a suppressed geometric relaxation upon excitation. Moreover, complementary calculations of the S1 → S0 relaxation and the S0→anion transition further confirm that NaO1 consistently exhibits smaller reorganization energies than L8-BO-C4 (Supplementary Fig. 28). These results provide additional evidence that the quinoxalinone-based core effectively mitigates vibrational relaxation across different electronic states. This reduction in vibrational coupling is beneficial for minimizing exciton loss through non-radiative channels, ultimately contributing to lower energy loss. Additionally, the optimal PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 device shows the shortest decay constants (τ1 = 0.99 ps, τ2 = 11.7 ps) and the fastest hole transfer dynamics, which likely contribute to its FF. To further probe charge dynamics, transient photocurrent (TPC) and transient photovoltage (TPV) measurements were performed (Supplementary Fig. 29). The TPC results reveal nearly identical carrier extraction times for the PM6:L8-BO-C4 and PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 devices (0.12 μs vs. 0.13 μs), suggesting comparable charge extractionin in both systems. In contrast, the TPV measurements show that the ternary PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 device exhibits a prolonged carrier lifetime (3.74 μs vs. 2.85 μs), indicating suppressed charge recombination. The observed improvement in TPV is consistent with the enhanced FF and overall PCE in the ternary device.

The charge generation mechanism of the ternary blend was further clarified by steady-state photoluminescence (PL) measurement (Supplementary Fig. 30). Since NaO1 and L8-BO-C4 exhibit similar absorption/PL spectra and a minimal LUMO offset (~0.07 eV), no cascade charge transfer or fluorescence resonance energy transfer is expected between them. Indeed, the PL intensity of their binary blend is close to the arithmetic average of the two pristine acceptors, ruling out inter-acceptor energy transfer. In contrast, all donor–acceptor blends show pronounced PL quenching due to efficient charge transfer at the donor/acceptor interface. Notably, the ternary PM6:L8-BO-C4:NaO1 blend exhibits stronger PL quenching than either binary, consistent with fs-TAS results showing accelerated charge separation, thereby confirming enhanced exciton dissociation in the ternary system.

Discussion

In summary, we systematically explored how fused-ring isomerization in the central core of SMAs governs molecular assembly and photovoltaic performance. By comparing three isomeric acceptors (NaO1, NaO2, and NaO3) with distinct backbone geometries, we revealed that small differences in molecular configuration can result in profound variations in packing motifs, electronic coupling, and solid-state organization. NaO1, featuring a linearly fused core, forms a highly interconnected 3D packing network with favorable π–π stacking and uniform nanofibrillar morphology, facilitating good charge transport and reduced recombination losses. In contrast, the more distorted cores in NaO2 and NaO3 promote excessive crystallization and phase segregation, which hinder efficient exciton dissociation and charge extraction.

Beyond static molecular packing, we also probed the real-time film formation dynamics using in-situ spectroscopy, uncovering that NaO1 exhibits rapid and continuous spectral red-shift during spin-coating, indicative of orderly molecular aggregation and favorable phase evolution. These structural and dynamic advantages of NaO1 translate into a high device efficiency of 19.11% when processed with o-xylene. Further, transient spectroscopy and exciton diffusion analysis confirmed enhanced charge separation kinetics and long exciton diffusion lengths for NaO1, consolidating the link between structural order and functional performance. Moreover, the incorporation of NaO1 as a third component in the PM6:L8-BO-C4 blend further enhances device performance, yielding a PCE of 20.07% with an elevated FF and suppressed non-radiative recombination losses. The approach scales: blade-coated modules (active area 15.03 cm²) reach 16.93%, among the highest reported at this area, and stability improves under light/thermal stress relative to the binary host. Taken together, our findings establish a direct and quantitative connection between backbone isomerism, intermolecular interactions, film morphology, and device-level outcomes. This work not only demonstrates the effectiveness of core-fusion geometry control in tailoring optoelectronic properties but also provides design guidance for developing efficient acceptor materials compatible with non-halogenated processing.

Methods

Device fabrication and testing

Solar cells were fabricated in a conventional device configuration of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PM6:acceptors/PFN-Br-MA/Ag. The ITO substrates were first scrubbed by detergent and then sonicated with deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol, subsequently, and dried overnight in an oven. The glass substrates were treated by UV-Ozone for 30 min before use. PEDOT:PSS (Heraeus Clevios P VP AI 4083) was spin-cast onto the ITO substrates at 4000 rpm for 30 s, and then dried at 170 °C for 15 min in air. The PM6: acceptor blends (1:1.2 weight ratio) were dissolved in ortho-xylene (the total concentration of blend solutions was 22 mg mL−1 for all blends, where 0.5% vol 1,8-diidoooctance was added as additive, and stirred at 100 °C in a nitrogen-filled glove box for 1 h. The blend solution was spin-cast at 2500 rpm for 30 s. The active layers were then treated by 100 °C thermal annealing for 2 min. A thin PFN-Br-MA layer was coated on the active layer, followed by the deposition of Ag (100 nm) (evaporated under 3 × 10−4 Pa through a shadow mask). The current density-voltage (J–V) curves of devices were measured using a Keysight B2901A Source Meter in glove box under AM 1.5 G (100 mW cm−2) using a Enlitech solar simulator. The device contact area was 0.041 cm2, device illuminated area during testing was 0.04 cm2, which was determined by a mask. The EQE spectra were measured using a Solar Cell Spectral Response Measurement System QE-R3011 (Enlitech Co., Ltd.). The light intensity at each wavelength was calibrated using a standard monocrystalline Si photovoltaic cell.

The large-area modules were fabricated with an architecture similar to that of the small-area cells. An aperture area of 16.80 cm2 in OSC modules, with 8 sub cells connected in series, was fabricated on the ITO glass substrates with a size of 5 × 5 cm2. The series interconnection of the module was realized by P1, P2, and P3 lines, which were patterned using a laser etching system with a GH-LS300. The gap between each ITO pattern is defined as P1 with a width of 20 μm. The P1-patterned ITO glass was then cleaned. PEDOT:PSS layer was then deposited on pre-cleaned ITO-coated glass through blade-coating at a speed of 20 mm s-1 and annealed at 150 °C for 15 min under ambient conditions. The active layer was blade-coated at a velocity of 20 mm s−1 and a gap height of 20 µm in the air, giving a ~105-nm-thick active layer. Next, 10-nm-thick C60 and 5-nm-thick BCP layers were deposited by thermal evaporation under 1 × 10-6 mbar. The P2 lines were patterned before Ag deposition, with the corresponding width is around 140 μm. Then, 100 nm thick Ag electrode was thermal evaporated under a pressure of 1 × 10−6 mbar, and the P3 (90 μm) line was formed. The active area of the module was defined by the shadow mask and the aperture mask as 15.03 cm2.

General information

All solvents and reagents were used as received from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise specified. All reactions were heated by metal sand bath (WATTCAS, LAB-500, https://www.wattcas.com). 1H NMR (400 MHz or 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz or 125 MHz) spectra were measured on a MERCURYVX300 spectrometers. Mass spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu spectrometer. High-resolution mass spectrometry was carried out on Thermo Scientific TM Q-Exactive.

Electrochemical characterizations

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were carried out on a CHI voltammetric analyzer at room temperature. Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (n-Bu4NPF6, 0.1 M) was used as the supporting electrolyte. The conventional three-electrode configuration consists of a platinum working electrode with a 2 mm diameter, a platinum wire counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl wire reference electrode. Cyclic voltammograms were obtained at a scan rate of 100 mV/s.

DFT calculations

DFT calculations were performed by using Gaussian 16 at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level, and the long alkyl chain was simplified as methyl. Electronic coupling was obtained by computing various dimer configurations extracted from the crystal structure. Reorganization energies were obtained using MOMAP 2024 A. LUMO orbit distribution analyses were performed with the Multiwfn 3.8.

Single-crystal growth and testing

Diffraction quality crystals were grown by the solvent diffusion method. Acceptors (5 mg) were dissolved in CHCl3 (5 mL) in the 15 mL sample bottle, then 8 mL of methanol or ethanol was added slowly. The bottle was then sealed tightly and left undisturbed for 10 days. The single crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K or 150 K on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å) or Ga Kα radiation (λ = 1.34139 Å).

AFM characterizations

AFM measurements were carried out using a Dimension 3100 Scanning Probe Microscope operated in tapping mode under ambient conditions at room temperature. All thin-film samples were prepared by spin-coating onto glass/ITO substrates.

In-situ and ex-situ GIWAXS measurements

In-situ GIWAXS measurements were carried out at beamline 1W1A of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) with an incident beam energy at 8 keV (the fixed grazing angle is 0.2°). The beam center and sample-to-detector distance were calibrated with LaB6. The samples were directly prepared on clean Si substrates with the same conditions as the device preparation. Each GIWAXS image was captured with the exposure time of 10 s during the spin-coating process. Ex-situ GIWAXS measurements were performed at the Complex Materials Scattering (CMS) beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), Brookhaven National Lab. The X-ray beam with an energy of 13.5 keV shone upon the samples with the incident angle of 0.15 deg with respect to the substrate between the critical angles of the organic films and the Si substrate. A custom-made Pilatus-2M detector was placed at the distance of 255 mm from the sample center to capture GIWAXS images with the exposure time of 10 s.

In-situ UV-Vis absorption measurements

In situ UV-Vis absorption measurements were carried out with a DU-100 system. The optical fiber was aligned so that the center of the light is focused on the center of the film. The sampling interval was 10 ms with an integration time of 10 ms per sample point. The average sampling times were adjusted 5 times to obtain smooth absorption curves.

PiFM Measurements

Photo-induced force microscopy (PiFM) results were acquired using a VistaScope microscope from Molecular Vista, inc. All PiFM experiments were excited by a pulsed quantum cascade laser (Block Engineering) with a gap-free narrowband tunable wavenumber of 760-1950 cm−1. The spectral linewidth is ~2 cm-1 with a wavenumber resolution of 0.5 cm−1. The PiFM experiment here was operated at the sideband excitation with the laser-frequency modulated at fm = f1–f0, where f0 is the first mechanical eigenmode resonances of the cantilever that is used for PiF signal detection, while f1 denotes the second ones recorded for the AFM topography of the sample. The probe is an Pt-coated tip with a resonant frequency of ~350 kHz (PPP-NCHPt-MB, Nanosensors).

Transient absorption spectroscopy

For femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy, the fundamental output from Yb:KGW laser (1030 nm, 220 fs Gaussian fit, 100 kHz, Light Conversion Ltd) was split into two light beams. One was introduced to NOPA (ORPHEUS-N, Light Conversion Ltd) to produce a certain wavelength for pump beam, the other was focused onto a YAG plate to generate white light continuum as probe beam. The pump and probe overlapped on the sample at a small angle less than 10°. The transmitted probe light from sample was collected by a linear CCD array. A pump pulse of 800 nm (below 5 μJ/cm2) was employed to excite only acceptors, and after a certain delay time, the relative transmittance change (ΔA) was probed using a white-light continuum. The primary absorption peaks for different acceptors and donors are well separated in the spectral domain, therefore, both the spectral and temporal characteristics of hole transfer dynamics can be extracted.

TPV and TPC measurements

In TPV measurements, OSC devices were subjected to a background light bias provided by a focused quartz tungsten–halogen lamp, with intensity adjusted to replicate operational conditions (i.e., yielding a device voltage equivalent to the open-circuit voltage under solar illumination). Photoexcitation was introduced by 8 ns laser pulses (Oriental Spectra, NLD520) at a wavelength of 518 nm with a spectral width of 3 nm. The TPV response was recorded at open-circuit conditions using a digital oscilloscope. For TPC measurements, signals were collected under short-circuit conditions with the same excitation wavelength but without background light bias.

FTPS-EQE and EL-EQE measurements

Fourier-transform photocurrent spectroscopy external quantum efficiency (FTPS-EQE) measurements were performed using a PECT-600 integrated system (Enlitech) with phase-sensitive detection. The photoresponse signal was amplified by a Stanford Research SR830 lock-in amplifier operated at a modulation frequency of 17 Hz. Electroluminescence external quantum efficiency (EL-EQE) was characterized under controlled carrier injection using a REPS-Pro voltage/current source (Enlitech). Devices were fabricated under optimized conditions with an active layer thickness of 100 ± 5 nm and electrode alignment precision better than 2 μm. The EL-EQE was measured by sweeping the applied voltage from 0 to 1.8 V in 0.1 V increments with a dwell time of 500 ms, enabling systematic investigation of recombination dynamics across the operating bias range. Both FTPS-EQE and EL-EQE employed thermoelectrically cooled InGaAs detectors (900–1600 nm) calibrated against NIST standards, ensuring wavelength-dependent quantum efficiency accuracy within ±1.5%.

Data availability

The experiment data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 2463998 (NaO1), 2463999 (NaO2) and 2464000 (NaO3). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors with high crystallinity and photoluminescence quantum yield enable >20% efficiency organic solar cells. Nat. Mater. 24, 433–443 (2025).

Mou, H. et al. Transient dipole strategy boosts highly oriented self-assembled monolayers for organic solar cells approaching 21% efffciency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 21241–21251 (2025).

Song, C. K. et al. Self-assembled charge-selective interfacial layers for organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17762–17773 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. π-Extended nonfullerene acceptor for compressed molecular packing in organic solar cells to achieve over 20% efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12011–12019 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors with branched side chains and improved molecular packing to exceed 18% efficiency in organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 6, 605–613 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Organic solar cells with 20.82% efficiency and high tolerance of active layer thickness through crystallization sequence manipulation. Nat. Mater. 24, 444–453 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Dipole moments regulation of biphosphonic acid molecules for self-assembled monolayers boosts the efficiency of organic solar cells exceeding 19.7%. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14287–14296 (2024).

Xie, C. et al. Mesoporous organic solar cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 109849 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Amide-based cathode interfacial layer with dual-modification mechanisms enables stable organic solar cells with high efficiency achieving 20%. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 9261–9272 (2025).

Tian, H. et al. Enhancing molecular stacking and fiber morphology of biaxially conjugated acceptors via cyano substitution to achieve 19.71% efficiency in binary organic solar cells. Sci. China. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-025-2671-6 (2025).

Classen, A. et al. The role of exciton lifetime for charge generation in organic solar cells at negligible energy-level offsets. Nat. Energy 5, 711–719 (2020).

Ma, Y. et al. Efficient organic solar cells from molecular orientation control of M-series acceptors. Joule 5, 197–209 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Non-fullerene acceptor with asymmetric structure and phenyl-substituted alkyl side chain for 20.2% efficiency organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 9, 975–986 (2024).

He, C. et al. Manipulating the D: a interfacial energetics and intermolecular packing for 19.2% efficiency organic photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2537–2544 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Exploiting the donor-acceptor-additive interaction’s morphological effect on the performance of organic solar cells. Aggregate 5, e455 (2024).

Ye, L. et al. Quantitative relations between interaction parameter, miscibility and function in organic solar cells. Nat. Mater. 17, 253–260 (2018).

Fu, J. et al. Rational molecular and device design enables organic solar cells approaching 20% efficiency. Nat. Commun. 15, 1830 (2024).

Bei, Q. et al. Benzothiadiazole-based materials for organic solar cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 108438 (2024).

Hou, J. et al. Organic solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Mater. 17, 119–128 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. The principles, design and applications of fused-ring electron acceptors. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 614–634 (2022).

Luo, Z. et al. Approaching 20% efficiency in ortho-xylene processed organic solar cells by a benzo[a]phenazine-core-based 3D network acceptor with large electronic coupling and long exciton diffusion length. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407517 (2024).

Cho, Y. et al. CF3-functionalized side chains in nonfullerene acceptors promote electrostatic interactions for highly efffcient organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 758–769 (2025).

Zhu, L. et al. Single-junction organic solar cells with over 19% efficiency enabled by a refined double-fibril network morphology. Nat. Mater. 21, 656–663 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. The development of quinoxaline-based electron acceptors for high performance organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404660 (2024).

Wei, W. et al. Precise methylation yields acceptor with hydrogen-bonding network for high-efficiency and thermally stable polymer solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202315625 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Molecular stacking and aggregation optimization of photoactive layer through solid additive enables high-performance organic solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e2023097 (2023).

Jiang, K. et al. Suppressed recombination loss in organic photovoltaics adopting a planar–mixed heterojunction architecture. Nat. Energy 7, 1076–1086 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Donor-acceptor mutually diluted heterojunctions for layer-by-layer fabrication of high-performance organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 9, 208–218 (2024).

Guan, S. et al. Self-assembled interlayer enables high-performance organic photovoltaics with power conversion efficiency exceeding 20%. Adv. Mater. 36, 2400342 (2024).

Chong, K. et al. Realizing 19.05% efficiency polymer solar cells by progressively improving charge extraction and suppressing charge recombination. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109516 (2022).

Cao, X. et al. O, S, and N bridged atoms screening on 2D conjugated central units of high-performance acceptors. Adv. Mater. 37, 2503131 (2025).

Yang, C. et al. Optimized crystal framework by asymmetric core isomerization in selenium-substituted acceptor for efficient binary organic solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313016 (2023).

Ma, R. et al. Triplet state suppression for energy loss reduction in 20% nonhalogenated solvent processed binary organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 37, 2500861 (2025).

Zhu, W. et al. Crystallography, morphology, electronic structure, and transport in non-fullerene/non-indacenodithienothiophene polymer: Y6 solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14532–14547 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Delocalization of exciton and electron wavefunction in non-fullerene acceptor molecules enables efficient organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 3943 (2020).

Yuan, J. et al. Single-junction organic solar cell with over 15% efficiency using fused-ring acceptor with electron-deficient core. Joule 3, 1140–1151 (2019).

Fan, H. et al. Phenanthrene treatment for o-xylene-processed PM6:Y6-based organic solar cells enables over 19% efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2405257 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Simultaneously optimizing molecular stacking and phase separation via solvent-solid hybrid additives enables organic solar cells with over 19% efficiency. Chin. J. Chem. 42, 3234–3242 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Butterfly effects arising from starting materials in fused-ring electron acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20124–20133 (2020).

Liu, K. et al. The Critical isomerization effect of core bromination on nonfullerene acceptors in achieving high-performance organic solar cells with low energy loss. Adv. Mater. 37, 202413376 (2025).

Lai, H. et al. Molecular skeletons modification induces distinctive aggregation behaviors and boosts the efficiency over 19% in organic solar cells. CCS Chem. 7, 1495–1508 (2025).

Swicka, S. M. et al. Closely packed, low reorganization energy π-extended postfullerene acceptors for efficient polymer solar cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8341 (2018).

Luo, Z. et al. Heteroheptacene-based acceptors with thieno[3,2-b]pyrrole yield high-performance polymer solar cells. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwac076 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Side-chain isomerization on an n-type organic semiconductor ITIC acceptor makes 11.77% high efficiency polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15011–15018 (2016).

Luo, Z. et al. Isomerization strategy of nonfullerene small-molecule acceptors for organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004477 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Effect of isomerization on high-performance nonfullerene electron acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9140–9147 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Signiffcant inffuence of the methoxyl substitution position on optoelectronic properties and molecular packing of small-molecule electron acceptors for photovoltaic cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700183 (2017).

Lai, H. et al. Crystallography, packing mode, and aggregation state of chlorinated isomers for efficient organic solar cells. CCS Chem. 5, 1118 (2023).

Luo, Z. et al. Asymmetric side-chain substitution enables a 3D network acceptor with hydrogen bond assisted crystal packing and enhanced electronic coupling for efficient organic solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4601–4611 (2022).

Yu, L. et al. Influence of solid-state microstructure on the electronic performance of 5,11-bis(triethylsilylethynyl) anthradithiophene. Chem. Mater. 25, 1823–1828 (2013).

Clark, J. et al. Role of intermolecular coupling in the photophysics of disordered organic semiconductors: aggregate emission in regioregular polythiophene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 206406 (2007).

Zafra, J. L. et al. Fingerprints of through-bond and through-space exciton and charge π-electron delocalization in linearly extended [2.2]paracyclophanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3095–3105 (2017).

Liang, L. et al. Strain-enhanced formation of delocalized exciton states in phthalocyanine crystalline thin films. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 8889–8896 (2022).

Jiang, K. et al. Photoluminescent delocalized excitons in donor polymers facilitate efficient charge generation for high-performance organic photovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 16, 3176 (2025).

Guo, S. et al. Molecular-orbital delocalization enhances charge transfer in π-conjugated organic semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306709 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. An isomeric solid additive enables high-efficiency polymer solar cells developed using a benzo-difuran-based donor polymer. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301231 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Upper layer-modulated pseudo planar heterojunction with metal complex acceptor for efficient and stable organic photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 37, 2410880 (2025).

Bi, P. et al. Reduced non-radiative charge recombination enables organic photovoltaic cell approaching 19% efficiency. Joule 5, 2408–2419 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. 22475133 and 22309119), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Nos. 20231120182602001, ZDSYS20210623091813040) and the Shenzhen University 2035 Program for Excellent Research (Grant No. 2024C007). The research used the Complex Materials Scattering (CMS) beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), which is an U.S. DOE Office of Science Facility, at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. We also thank the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shenzhen University for the analytical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. conceived the idea and wrote the manuscript. J.Z. synthesized the NaO-series materials. R.M. and L.C. characterized the small area devices. R.L., J.T., J.F., L.Yu, and L.Ye performed the GIWAXS characterizations and analysis. Z.C. conducted theoretical calculations and analysis. D.L. conducted the TA experiments. L.C. and G.Z. conducted the in-situ absorption spectroscopy characterization. The large-area module devices were characterized by Y.W. and H.C. under the supervision of Y.L. The manuscript was approved by all authors. L.Yu, R.M., G.L., C.Y., and Z.L. provided important insights during the project design and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Ma, R., Li, R. et al. Fused-ring isomerism modulates molecular packing and device performance in non-halogenated organic solar cells. Nat Commun 16, 11480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66573-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66573-3