Abstract

Given the urgency of climate change and the need for an energy transition, global coal power generation is rapidly declining. However, coal transition strategies optimized for cost-benefit and aligned with climate targets remain underexplored. Here, we develop a Plant-level Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Dynamic Optimization Model to conduct a cost-benefit optimization analysis for India’s coal-fired power plants, through which the study proposes differentiated phaseout roadmaps aligned with the 1.5 °C and 2 °C climate targets. Our findings suggest that ambitious climate targets can yield more significant economic benefits, and more aggressive coal power retirement strategies are economically feasible. For example, Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh could achieve the total net benefits of 171 and 110 billion US dollars in the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios. Furthermore, incorporating social benefits into the evaluation will enhance the feasibility of the coal phaseout and reinforce India’s decarbonization commitments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Economies worldwide are threatened by the losses and damages caused by climate change, making climate mitigation a global concern. India, the third-largest carbon-emitting country globally, derives more than half of its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from coal power1,2,3. Therefore, coal power plays a pivotal role in achieving emission mitigation goals. For the world to have a chance of meeting the Paris Agreement’s temperature target, India needs to transition away from fossil fuels quickly4,5,6.

The phaseout of coal power will result in both positive and negative effects. From one perspective, this transition may cause carbon-intensive assets to depreciate or retire before their expected lifetimes, resulting in stranded assets7,8. Studies have also found that India faces a high risk of stranded assets9,10. Additionally, the phaseout of power plants will interrupt their profitability, leading to cumulative profit losses over their expected lifespan. This interruption affects the financial stability of the power plant, as the revenue streams expected during the remaining operational years are lost. Furthermore, with the acceleration of the energy transition, the coal mining industry and related sectors supporting coal-based power generation will lose market share and employment opportunities, resulting in decreased tax revenues in coal-dependent regions11. From another perspective, this transition will generate social benefits by avoiding carbon emissions and thereby mitigating current and future climate damages. These avoided damages include impacts on agricultural production, reduced labor productivity, property losses, increased frequency of disasters, and induced migration12,13. In addition, actions to reduce carbon emissions often decrease associated air pollutants, yielding co-benefits for air quality and public health14,15. Recent findings suggest that the negative impacts of climate change are concentrated in developing economies, commonly referred to as low- and middle-income economies according to the World Bank’s classification16. Among them, India bears the highest social cost of carbon (SCC)17,18. Hence, these developing economies will implement higher carbon taxes for the nation’s benefit18. Overall, these positive and negative effects, crucial for India’s coal power transition, remain unclear. In future coal power planning, it is essential to fully consider both benefits and losses to conduct a comprehensive assessment of decisions.

The Indian government is actively accelerating the deployment of renewable energy to achieve the target outlined in its updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), aiming for 500 gigawatt (GW) of non-fossil fuel installed capacity by 203019. As a result, India ranked fourth globally in renewable energy capacity in 202320. However, despite these efforts, the country remains heavily reliant on coal. As of 2020, the total installed capacity of operational coal-fired power plants was 233 GW, with an additional 53 GW of planned and under-construction units expected to come online by 2030. Moreover, with ~20% of its coal consumption reliant on imports, rising global coal prices are likely to intensify future coal supply pressures, substantially driving up the cost of coal-fired power generation and highlighting the urgent need to reduce India’s overreliance on coal21,22.

Global and regional studies have utilized unit-level data, considering the heterogeneity of various factors and revealing the pathways for fossil fuel phaseout23,24,25,26,27. However, most evaluations are based on the multi-criteria decision analysis method for energy planning and scenario comparisons28. These studies usually consider each criterion and assign relative weights for decision aggregation, where the weights are often subjective and preference-based. Moreover, investigations on stranded assets due to coal power transition9,29,30,31 also generally believe that ambitious climate policies will lead to more stranded assets, but largely ignore the economic benefits of carbon emission reduction. A few studies have considered the carbon benefits of eliminating coal power and conducting cost-effectiveness analysis32, but the optimal solution has yet to be provided. Although the cost-benefit analysis can provide a comprehensive evaluation by converting all impacts into monetary terms33, coal power transitions will always be challenging regarding cost and benefit in the future. If the costs and benefits are incorporated into comprehensive assessments of coal facilities’ retirement and new construction, it will help promote coal power transition policies in developing countries consistent with the Paris Agreement.

Despite substantial progress in renewable energy capacity expansion and a clearly defined strategic intent to develop renewable energy over the next decade, the timeline and pathway for India’s transition away from coal remain uncertain, particularly regarding the specific retirement schedule of individual coal-fired power plants. To fill this research gap, this study formulates a dynamic optimization problem to determine the optimal retirement schedule for India’s coal-fired power plants under the national carbon emission reduction pathway (CERP) established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In this context, this study develops the Plant-level Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Dynamic Optimization Model (MIND-Plant). The model incorporates the evolution of the power system under 1.5 °C and 2 °C climate target scenarios, balancing environmental benefits (carbon emission reductions and avoided health risks), economic costs (profitability losses and stranded asset risks), and social risks (tax and employment impacts). The optimization is performed iteratively using the Gurobi Optimizer version 10.0.3 to generate a progressive power plant retirement schedule, designing a gradual coal phaseout pathway aligned with India’s energy transition goals. Specifically, the model assigns a binary decision variable to each power unit, indicating whether it should retire in a given year. It then calculates the cumulative impacts across four dimensions from the retirement year until the end of its expected lifespan. The optimization process maximizes overall benefits and minimizes total costs, balancing these impacts to determine the optimal retirement year for each unit, ultimately solving the global optimum of this nonlinear problem. This study applies the optimization framework to analyze India’s coal power transition, and the results revealed optimal coal phaseout pathways from 2020 to 2060 under different climate targets. The findings indicated that to achieve the 1.5 °C and 2 °C climate goals, the average operational lifespan of India’s coal-fired power plants will be reduced by 12 years and 5 years, respectively. The plant-level coal phaseout roadmap developed in this study could guide the orderly retirement of India’s coal power plants and contribute to achieving India’s carbon reduction commitment under the 2030 NDC, providing a scientific basis for power transition pathways and policy formulation.

Results

Characteristics and retirement pathways of India’s coal power units

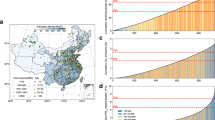

The spatial distribution of coal-fired power plants in India is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Coal power units are located across 21 states, with a total installed capacity of 233 GW as of 2020, primarily concentrated in the western and eastern regions. The top three states in terms of capacity are Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh, with installed capacities of 27 GW, 25 GW, and 24 GW, respectively, accounting for 33% of the national total. Figure 1b illustrates the age structure of operating units, with 57% commissioned between 2000 and 2020, indicating a relatively young fleet. Additionally, ~53 GW of capacity is under construction or planned, and it is expected to come online within the next decade, with Uttar Pradesh leading with about 10 GW.

a Geographic locations and the installed capacities of individual operating units in India. The map is based on factual evidence and displays the non-disputed areas under actual control. b Total installed capacity and age structure of operating units in each state (the baseline year is 2020), as well as the capacity of units under construction or planned (Pipeline). Capacity is expressed in megawatts (MW) at the unit level and in gigawatts (GW) at the state level. c, d India’s coal power capacity pathways consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 °C and 2 °C. The dark lines indicate median pathways, with shaded areas representing the 5th–95th percentile range (light shading) and the 25th–75th percentile range (dark shading). The raw scenario data is sourced from the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Scenario Database68. The base map was obtained from Esri ArcGIS 10.8. Map images © Esri and its licensors. Used under license.

The climate target pathways used in this study (Fig. 1c, d) show the projected trend in India’s coal power capacity, which is expected to peak between 2020 and 2030. The median pathway suggests that to limit warming to 1.5 °C, coal capacity will gradually phase out by around 2045, while for a 2 °C target, it will phase out by around 2055. Under stricter climate goals, coal retirement will accelerate to achieve higher emissions reduction targets.

Multidimensional effects of coal power phaseout based on cost-benefit analysis

We conducted a cost-benefit analysis using a dynamic optimization approach, incorporating environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Carbon and health benefits reflect the advantage dimension, while tax & employment and plant losses correspond to the cost aspect. The model determined the optimal retirement year for each unit and the optimal values for each objective. Figure 2a, b illustrates the trade-offs in cost-benefit for operating and pipeline coal units under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C climate targets. The blue solid lines represent the results for each dimension under the assumed lifetime of 40 years. The shaded areas indicate the uncertainty range results, accounting for an expanded assumed lifetime of 35–45 years, as well as variations in other parameters (see the uncertainty analysis section in “Methods”). Stricter climate targets result in higher plant losses and tax & employment losses, amounting to 516 billion US dollars (USD) (range: 377–723) under the 1.5 °C scenario, and 253 billion USD (range: 171–415) under the 2 °C scenario. However, these stricter targets also yield substantially higher carbon and health benefits, reaching 1879 billion USD (range: 1218–2946) for 1.5 °C, and 1055 billion USD (range: 589–1906) for 2 °C. This highlights the economic advantages of pursuing ambitious temperature goals. Figure 2c, d presents the results for individual units across dimensions, with the black line representing the value assumed for the 40-year lifetime. Significant variation exists between different units in all scenarios. Generally, large-capacity units, especially those exceeding 600 megawatts (MW), have a more substantial impact on carbon benefits, consistent with their high emissions and energy consumption. This highlights the critical role of larger plants in impacting overall metrics and guiding decision-making. Additionally, health impacts are influenced by the regional background characterization factors of local pollutants, as measured per disability adjusted life years (DALYs) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a, b Total costs and benefits of all units under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios, showing the cumulative values from early retirement to the end of the assumed lifetime. The shaded areas represent the range of uncertainty. c, d The cumulative values for each unit across four dimensions, with units sorted from left to right in increasing order. The bar colors represent the installed capacity of each unit (in gigawatt, GW). The four dimensions include carbon benefits, health benefits, plant losses, and tax & employment losses, all measured in billion US dollars (USD). The results include both operational and pipeline units.

Phaseout roadmap for coal power units

Based on the optimization, we developed an optimized retirement schedule for each unit and mapped it spatially. Panels a and b of Fig. 3 show the spatial distribution of operating and pipeline units in different states across four time periods (2020–2030, 2030–2040, 2040–2050, 2050–2060) under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios. Grey or red dots represent operational units that continue operating or retire within each period. In contrast, green or yellow dots indicate new pipeline units that start operation or quit shortly after. The 1.5 °C target requires higher retirement rates, with 484 operation units (105 GW) and 36 pipeline units (24 GW) phased out between 2020 and 2030, even for larger plants, especially in the Eastern Coal Belt. This trend continues to increase between 2030 and 2040 (gradually increasing numbers of red and yellow dots). New units are also expected to retire before 2050, thereby increasing the risk of stranded assets. In contrast, the 2 °C target allows for a more gradual retirement process, with more early retirements concentrated after 2030 (represented by more red dots). Moreover, the units have average lifetimes shortened to 28 and 35 years (Fig. 3c). These results highlight that achieving the 1.5 °C target demands faster emissions reductions and large-scale early retirements, while the 2 °C target allows more time for adjustment.

a, b The retirement year of individual coal power units. Operating units refer to those still in operation in the baseline year 2020, while pipeline represents units that are planned or currently under construction. The grey, red, green, and yellow dots represent operation units that have not yet been retired, operation units that have retired, commissioned pipeline units that have not yet been retired, and retired pipeline units, respectively. The size of the circles indicates the installed capacity (in megawatt, MW). The labels in the upper-right corner of each map indicate the number of retired units by type and their total capacity (in gigawatt, GW). The map is based on factual evidence and displays the non-disputed areas under actual control. c The actual lifetime of each unit under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios. d, e Cost-benefit outcomes for each state under two scenarios, ranked in descending order by net value from top to bottom. The benefits include carbon and health benefits, while the costs encompass plant loss and tax & employment loss. The base maps were obtained from Esri ArcGIS 10.8. Map images © Esri and its licensors. Used under license.

From a state-level perspective (Fig. 3d, e), our retirement strategy reveals that Chhattisgarh could achieve the net benefits of 171 billion USD in the 1.5 °C scenario, retiring 83% of its installed capacity (25 GW) between 2030 and 2040. Similarly, Uttar Pradesh demonstrates the net benefits of 110 billion USD in the 2 °C scenario, retiring 48% of its installed capacity (15 GW) between 2040 and 2050. In addition, Maharashtra yields the most significant benefits in both scenarios but also incurs the highest costs. Specifically, under the 2 °C scenario, plant losses, and tax & employment losses are estimated at 83 and 31 billion USD, respectively, increasing to 110 and 42 billion USD under the 1.5 °C scenario (the results for each state are summarized in Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Fig. 6). These findings underscore the need for each region to adopt a flexible and tailored transition plan to effectively manage the risks associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy.

National and state-level environmental benefits

We developed unit-level retirement pathways based on climate target constraints and cost-benefit optimization. Annual avoided CO₂ emissions and health impacts were calculated for each coal unit under the retirement strategy, with results aggregated at the national and state level. On the national scale (Fig. 4a, b), the more ambitious 1.5 °C scenario achieves significantly higher cumulative avoided CO₂ emissions of 26 Gt (range: 20–33) and health impacts of 1.3 million DALYs (range: 1.0–1.6) compared to the 2 °C scenario, which achieves 15 Gt (range: 10–21) and 0.71 million DALYs (range: 0.4–1.0) by the latter half of the Century. Additionally, the 1.5 °C scenario achieves a faster emission reduction rate, with the gap between the two scenarios widening over time, highlighting the long-term benefits of more stringent climate goals. Peak annual avoided CO₂ emissions are projected at 1.09 Gt (range: 1.02–1.13) by 2043 (range: 2040–2044) under the 1.5 °C scenario and 0.74 Gt (range: 0.57–0.95) by 2048 (range: 2045–2054) under the 2 °C scenario. Beyond these peaks, scenarios assuming a 45-year operational lifetime yield more significant cumulative avoided CO₂ emissions and health impacts than those considering a 35-year operational lifetime, due to the extended service time of coal units, leading to more substantial cumulative reductions.

a, b National results. c, d Results for the top 14 states ranked by installed capacity. The solid lines show results under the 40-year lifetime assumption, while the shaded areas indicate the range across lifetime scenarios (35–45 years). CO2 emissions are expressed in gigatonnes (Gt) at the national level and in million tonnes (Mt) at the state level. Health impacts are measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

At the state level, the 14 states shown in the Fig. 4c, d account for 95% of India’s total installed capacity (Supplementary Fig. 4), with notable regional differences in benefits and losses. States with higher capacities, such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Maharashtra, show more significant reduction potential, with cumulative avoided CO₂ emissions projected to reach 4.6–9.3 Gt (2 °C) and 8.4–13.6 Gt (1.5 °C) by 2080. In contrast, northern states like Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan have lower capacities, resulting in smaller avoided emissions. Additionally, an estimated 53 GW of new capacity expected by 2030 is likely to accelerate emissions reductions across most states thereafter. Avoided health impacts vary with location, population density, and baseline pollution levels. West Bengal, for example, has the highest regional particulate matter health impact factors (Supplementary Fig. 5) and thus the most significant cumulative avoided health impacts, estimated at 182 (range: 116–261) and 65 (range: 36–113) thousand DALYs under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios, respectively.

Discussion

The low-carbon transition of the power industry is crucial for mitigating climate change. This study demonstrates that, under both the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios, the benefits of carbon emissions reduction and health improvements generally outweigh the losses in tax revenue, employment, and power units’ profitability, with more ambitious climate targets proving to be more cost-beneficial. Based on the MIND-Plant model, the study further proposed the unit-level optimized retirement plan, revealing regional disparities under different climate targets: under the 1.5 °C scenario, more units need to be retired between 2020 and 2030, concentrated in the north, west, and east; under the 2 °C scenario, the retirement process is more gradual. These regional differences highlight the need for developing differentiated regional policies that provide adequate support and forward-looking planning for the more affected regions during the transition process, thereby mitigating potential resistance.

Although India’s coal capacity pipeline, including announced, pre-licensed, and licensed projects, has declined by 85% since 2014 (from 250 GW to 36 GW)22, some regions remain heavily reliant on coal for economic development, employment, and fiscal revenue, particularly in the Eastern Coal Belt11,34,35. These areas are therefore more vulnerable to the risk associated with the coal phaseout. For instance, under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios, Maharashtra is projected to incur combined losses in power plant assets, tax revenues, and employment amounting to 152 and 114 billion USD, respectively (Fig. 3d, e). To ensure a just and sustainable energy transition, the government should prioritize targeted financial compensation, workforce retraining, and employment support for the regions most affected by the transition.

Regional transition strategies are not only determined by spatial deployment, but also by the timing of interventions. Energy infrastructure, once established, tends to create long-term dependence on pathways. Hence, delayed decisions can reduce the flexibility of the power system and constrain future transition options29. India’s current operating coal power plants are relatively young, with an average age of 17 years. To align with the 1.5 °C and 2 °C climate targets, the average retirement age would be brought forward to 28 and 35 years, respectively. Our analysis outlined a structured coal transition pathway that includes the gradual phaseout of existing coal power plants starting in 2020 and the cessation of new coal power construction after 2030. Without such interventions, India’s coal capacity is projected to continue expanding. Emissions from these plants could undermine India’s NDC target and impede effective long-term climate mitigation. If the power sector continues along its current trajectory, more costly measures, such as the deployment of carbon capture and storage or large-scale carbon dioxide removal technologies, will be required to offset rising emissions36. Moreover, the construction of proposed coal plants will result in resource lock-in and miss opportunities for potential investment in renewable energy37. Hence, cancelling planned coal power projects should be prioritized to prevent carbon lock-in, while simultaneously pursuing a strategic and regionally tailored phaseout of existing coal power plants. This strategy can also promote future technological innovation and policy development, ultimately contributing to the achievement of global climate mitigation goals.

Reducing the environmental risks associated with coal power expansion is essential for sustainable development. The continued growth of coal power capacity poses serious threats to environmental quality, including increasing greenhouse gas emissions, worsening air pollution, and depletion of water resources. An early transition away from coal, in line with ambitious climate targets, can substantially mitigate these risks. Increasing urban air pollution and public health issues in India have become important drivers for reducing coal power38,39. If the phaseout strategy in this study is implemented, an estimated 1.0–1.6 million DALYs (1.5 °C) and 0.4–1.0 million DALYs (2 °C) can be avoided. At the same time, cumulative carbon emissions of 1.9–2.3 Gt (1.5°C) and 0.9–1 Gt (2 °C) can be reduced by 2030. This strategy will help India achieve its NDC target of reducing carbon emissions by 1 Gt by 2030. As India prepares to update its 2035 NDC, the findings will also help mobilize international support for a more ambitious and actionable decarbonization roadmap, thereby avoiding a lock-in to a high-carbon development trajectory.

India has introduced policies such as the Production Linked Incentive scheme to support the renewable energy goals40. In parallel, the country aims for non-fossil fuel sources to account for ~50% of total power generation, meeting half of its energy demand by 2030 and reinforcing its commitment to net-zero emissions by 2070. Among them, wind and solar power exhibit high scalability, maturity, and commercial viability in India41, with solar power capacity reaching 92 GW in 202442. While these low-cost renewable energy sources are expected to meet future energy demand, the transition to renewable energy still faces challenges in technology, finance, and infrastructure.

This study primarily focuses on the transition and retirement pathways of coal-fired power units, along with their associated environmental and socioeconomic impacts, while broader topics such as energy security and renewable energy substitution are beyond the scope of this paper. It is essential to note that although the model outlines an framework for coal power retirement, the implementation in the real world is subject to multiple uncertainties, including renewable energy potential, grid flexibility, social acceptance, and political will. In particular, regions with weak regulatory capacity or high fiscal dependence on coal may face stronger political resistance, which could potentially delay the transition process. These potential barriers and critical uncertainties suggest that, while this study represents a exploration of power transition, the actual decarbonization pathway is likely to be more complex than model projections indicate. Future research should adopt interdisciplinary approaches, integrate external variables such as electricity market fluctuations and policy dynamics, and systematically assess the technological potential and feasibility of renewable energy alternatives to provide more comprehensive support for a fair and sustainable power transition.

Methods

Optimization framework

To determine the optimal retirement schedule for coal-fired power plants in India under the CERP set by the IPCC, this study develops the MIND-Plant model to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of both operational and pipeline coal-fired power plants. The Gurobi Optimizer version 10.0.3 is employed as the solver to achieve dynamic optimization through iterative computation. Specifically, the model assumes that a unit retires before the end of its assumed lifetime, and the avoided carbon emissions and PM2.5-related health impacts from the retirement year to the end of its assumed lifetime are considered benefits. However, such early retirement also results in profit loss, stranded assets, tax, and employment losses caused by the premature closure of the unit, which is defined as costs. These costs, together with the avoided carbon emissions and health impacts, constitute the optimization objectives of the model. We monetize the benefits of avoided carbon emissions and health impacts, compare them with the cost, and aggregate these objectives into a single objective function, allowing the model to optimize and solve for the final result.

Based on these objectives, the model incorporates capacity constraints aligned with climate targets and balances the impacts across multiple dimensions to maximize benefits and minimize costs for all units. During the optimization process, a binary decision variable is assigned to each power unit for each year, indicating whether it should retire. It then iteratively calculates cumulative impacts across the four dimensions, spanning from the retirement year to the unit’s assumed end of its lifetime. Through this process, the model aims to maximize the system’s cost-benefit and identify the global optimum for this complex nonlinear problem. Ultimately, the model determines the optimal retirement year for each unit, deriving the optimal value for each dimension, and provides the optimal retirement schedule for each power plant.

The objective functions are as follows:

Where \({x}_{i,t}\) and \({x}_{j,t}\) are binary decision variables indicating whether the operational unit \(i\) or pipeline unit \(j\) retires in year \(t\). The decision variables \({x}_{i,t}\)=1 or \({x}_{j,t}\)=1 if operation unit \(i\) or pipeline unit \(j\) begins retire in year \(t\), and it takes the value of 0 otherwise. \(C{B}_{i,j,t}\), \(H{B}_{i,j,t}\), \(T{J}_{i,j,t}\), and \(P{L}_{i,j,t}\), represent the cumulative carbon benefit, health benefit, tax & employment loss, and plant loss of unit\(\,i\) and \(j\) from retirement year (\({t}_{retire}\)) to the end of the assumed lifetime year (\({Y}_{i,j}+lifetime\)), respectively. \({Y}_{i,j}\) denotes the online year of the operation unit \(i\) and the commission of unit\(\,j\), respectively. \(lifetime\) is the assumed lifespan of 40 years, and we conduct an uncertainty analysis by extending the assumed lifetime range to 35–45 years. These benefits or losses occur after the unit retires. \(I\) and \(J\) represent the fleets in operation and commission, respectively.

Set up constraints

For each year \(t\), the total capacity of all non-retired units aligns with the capacity pathway for the 1.5 °C or 2°C targets. Each unit may be phased out once during the planning period.

Where \(Ca{p}_{i}\) and \(Ca{p}_{j}\) are capacity of unit \(i\) and \(j\), respectively. \({c}_{j,{Y}_{j}}\) is the binary decision variable indicating whether the pipeline unit \(j\) is commissioned in the year \({Y}_{j}\). \({C}_{t}\) is the capacity pathway under the climate targets.  is a non-negative slack variable introduced to allow a certain degree of exceedance. In addition to capacity constraints, it is also necessary to meet assumed lifetime constraints (\(lifetime\)), meaning units that have operated for their designated lifetime must be retired. Formulas (6) and (7) indicate that each unit in operation and pipeline can only be retired once during its lifetime, respectively. Formula (8) suggests that each pipeline unit can only come online once. Under the capacity constraints consistent with climate targets, the model iteratively solves to determine the optimal retirement year for each unit that achieves the maximum cost-benefit. The cumulative impacts across all dimensions from the optimal retirement year to the end of the assumed lifetime can also be obtained.

is a non-negative slack variable introduced to allow a certain degree of exceedance. In addition to capacity constraints, it is also necessary to meet assumed lifetime constraints (\(lifetime\)), meaning units that have operated for their designated lifetime must be retired. Formulas (6) and (7) indicate that each unit in operation and pipeline can only be retired once during its lifetime, respectively. Formula (8) suggests that each pipeline unit can only come online once. Under the capacity constraints consistent with climate targets, the model iteratively solves to determine the optimal retirement year for each unit that achieves the maximum cost-benefit. The cumulative impacts across all dimensions from the optimal retirement year to the end of the assumed lifetime can also be obtained.

Carbon benefit

In our study, we use the avoided CO2 emissions from coal units to estimate social benefits, which are calculated in terms of the SCC. The SCC represents the economic cost associated with climate damage caused by emitting an additional tonne of carbon dioxide43. SCC provides a monetary estimate of the marginal damages of climate change.

The cumulative carbon benefits of coal power units are as follows:

Where \(SC{C}_{t}\) is the social cost of carbon in year \(t\), adjusted for growth rate and discount rate. \({E}_{i,j,t}\) is CO2 emissions of unit \(i\) and \(j\) in year \(t\), measured in tonnes. The base SCC in 2020 is fixed at 86 USD tCO2−1, with an annual growth-adjusted rate (g) of 2.2%17,18. The carbon benefit is discounted (\({d}_{scc}\)) at a rate of 3%17. \({t}_{0}\) represents the base year, 2020.

The CO2 emissions from coal power units primarily depend on the capacity, capacity factor, and the type of coal used. Referring to the calculation methods from ref. 44, the annual CO2 emissions (tCO2 year−1) for each power unit are calculated as follows:

Among them,\(\,{G}_{i,j,t}\) is the electricity generation of unit \(i\) and \(j\) in year \(t\), calculated by unit-level capacity (MW), capacity factor (%), and operating hours. We compiled the electricity generation data from each power plant in India using Central Electricity Authority (CEA) Monthly Generation Reports 202045, including annual generation and capacity factor. We matched it with our power unit dataset and used the state average value from the CEA reports for power units that lacked capacity factor data (Supplementary Table 2). \(H{R}_{i,j}\) denotes the heat rate in British thermal unit per kilowatt-hour (Btu kWh−1)46 (Supplementary Table 3), and \(E{F}_{i,j}\) represents the emission factor in kilogram CO2 per terajoule (kgCO2 TJ−1), dependent on coal type47 (Supplementary Table 4). \(c_{1}\) is a unit conversion constant, equal to 9.2427\(\times\)10−6.

Health benefit

As air pollution is a major global cause of premature death, its associated human health impacts have garnered extensive attention48,49. Air pollution from coal power generation contributes to ~80–112 thousand premature deaths annually in India, resulting in substantial economic losses15,50,51. Therefore, we further incorporate the avoided health impacts related to air pollution in our assessment, quantifying them as economic benefits.

We spatially model the health burden and related economic impact caused by primary air pollutant emissions, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Specifically, we estimate the health burden from primary PM2.5 pollution at each facility location using the methods described by Oberschelp et al.52. We then characterize this burden in terms of DALYs, which measure both the years of life lost due to premature mortality and the years lived in less than full health53. We then refer to the methods from Rauner et al.54 to monetize health effects using willingness-to-pay valuation, thereby converting the health impacts associated with air pollution into monetary terms.

Where \(H{B}_{i,j,t}\) is the avoided economic loss in health benefits due to avoiding air pollutant emissions for unit \(i\) and unit \(j\) in year \(t\). \(DAL{Y}_{i,j,t}\) is the disability-adjusted life year caused by exposure to primary PM2.5. \({S}_{i,j,t}\), \(\,{N}_{i,j,t}\), and \(\,{P}_{i,j,t}\) represent the annual primary emissions of SO2, NOx, and PM2.5 at the unit level, measured in kg. \(c{f}_{{\rm{SO}}2}\), \(c{f}_{{\rm{NOx}}}\), and \(c{f}_{{\rm{PM2}}.5}\) are the regional characterization factors for each pollutant emission per DALY, derived from high-resolution global characterization factor maps (Supplementary Fig. 5) with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. These maps are developed using atmospheric transport and chemical models for several major air pollutants52. \({{\rm{V}}}_{{\rm{DALY}}}\) reflects the amount willing to be paid to mitigate the risk of premature death and non-optimal health for 1 year of life, valued at 118,421 USD per DALY54. α is the regional adjustment factor for India (Supplementary Table 5). Economic impacts due to health impacts are discounted at a rate of 5% (\({d}_{hb}\))55.

\({G}_{i,j,t}\) is the electricity generation of each power unit, measured in kWh; \(e{f}_{k}\) is the emission factors for pollutant class \(k\), measured in grams per kWh (g kWh−1) (Supplementary Table 6). Regional emission factors come from the ECLIPSE_V6b_CLE_base emission scenario dataset developed by the GAINS model56. c2 is the constant for converting energy units from Btu to TJ, equal to 1.055 × 10⁻⁹.

Tax and employment loss

Transition away from coal power is likely to have adverse impacts on government tax revenues and local employment. Therefore, tax (\({T}_{i,j,t}\)) and employment losses are incorporated into the optimization model.

In this study, the taxes for coal-fired power plants include direct taxes (\({T}_{direct,i,j,t}\)), indirect taxes (\({T}_{GST,i,j,t}\)), and coal taxes (\({T}_{GST\,{\rm{Compensation}}Cess,i,j,t}\)). The direct taxes primarily consist of income tax, corporate tax, capital gains tax, and securities transaction tax, accounting for 30% of net income. If revenue exceeds Indian Rupee (INR) 10 million, an additional surcharge of 2% is also levied57. The indirect taxes consist of Goods and Service Tax (GST), which has replaced the previous State Value-Added Tax, Central Sales Tax, and Service Tax on Transportation57. The coal tax is an implicit carbon tax levied on mined coal, also known as the Clean Energy Cess or Clean Environment Cess. Since the introduction of the coal tax, the price of coal has increased from INR 50 per tonne in 2010 to INR 400 per tonne in 201658. With the introduction of GST in India in July 2017, the Taxation Laws Amendment Act 2017 abolished the Clean Energy Cess. In its place, the GST Compensation Cess was introduced at a rate of 400 INR per tonne59.

The formulas for calculating tax revenue are as follows:

Where,\(\,{T}_{i,j,t}\) is total tax. \({r}_{direct}\) represents the income tax rate (the value is 32% if \(N{P}_{i,j,t}\) > = INR 10 million, else 30%, assuming 1 USD = 74 INR in 2020).\(\,N{P}_{i,j,t}\) is the net profit of the unit. \({r}_{cess}\) represents the GST Compensation Cess rate, which is INR 400 per tonne. \(LHV\) is the lower heat value, measured in kilocalories per kg (kcal kg−1)46. The tax revenue is discounted at a rate of 10% (\({d}_{tax}\))60.

To assess the losses incurred by India from the gradual phaseout of coal power, the impacts on unemployment are calculated by applying the corresponding employment factors to the installed capacity and electricity generation. The total number of jobs is estimated by multiplying the installed coal capacity by the employment multiplier for the operation and maintenance sector, expressed in jobs per MW61. We use the average real wages in the Indian power sector, as reported by the International Labour Organization, to represent the wages of coal power plant workers62. Employment losses are then monetized and discounted at a rate of 3%17. This section mainly focuses on the direct employment losses resulting from the shutdown of coal power plants, specifically the unemployment of operation and maintenance workers. It excludes jobs in construction, installation, manufacturing, coal mining, and transportation63. Although the retirement of power plants may generate new employment opportunities, this aspect is not considered in this study.

Power plant loss

To meet climate targets, coal-fired power plants are expected to retire early, resulting in plant losses that include foregone profit opportunities (\(P{L}_{i,j,t}\)) and stranded assets (\(S{A}_{i,j,t}\)). We first assess the profitability of each unit. Annual profit is estimated as the difference between annual revenues and costs. Revenues are calculated based on electricity prices and the electricity generation of units.

In this context, \(N{P}_{i,j,t}\) is the annual net profit of unit i and unit j in year t, which is calculated by revenue minus cost (\({C}_{i,j,t}\)). Revenue is measured by electricity prices (\(EP\)) and electricity generation (\({G}_{i,j,t}\)), and the value of \(EP\) in each state as referenced in the reports published by each State Electricity Regulatory Commission64. \({C}_{i,j,t}\) include fuel delivery costs (\({C}_{coal}\), USD per tonne), variable operating and maintenance costs (\({C}_{OM,variable}\), USD kWh−1), fixed operating and maintenance costs (\({C}_{OM,fixed}\), USD kW−1). The units’ profit is depreciated at a discount rate \({d}_{np}\), which is 10%46,60.

Where the coal cost is measured by the delivered coal price \({C}_{coal,cost}\), which includes purchase and transportation costs. \({C}_{OM,fixed,unitary}\) and \({C}_{OM,variable,unitary}\) are referenced from the research of Mallah et al.65.

Second, we explore the risk of stranded assets for units under climate scenarios and consider this as a loss. Unrecovered capital costs are used as a measure of stranded assets. The abandonment value of power plants retired prematurely is calculated as the total capital of the assets multiplied by the portion of the expected lifespan that is abandoned due to early retirement7. Stranded Assets are calculated using the following formula10:

In the formula, \(S{A}_{i,j,t}\) is stranded assets for unit \(i\) and unit j in year \(t\); \(Ca{p}_{i,j}\) represents capacity; L denotes the assumed lifetime; \(R{L}_{i,j}\) stands for retirement age; and OCC represents the overnight capital cost for each power unit (measured in USD per kW), which is estimated based on the research conducted by Dulong et al.9. And the stranded assets are discounted by 5% to the base year (\({d}_{sd}\))9,66. The retirement of units that have operated beyond their fixed lifespan will not result in any stranded assets, as the initial capital cost has been fully paid67. Therefore, we only consider units with \(L\ge R{L}_{i,j}\), otherwise, the stranded assets are zero.

Scenario description

We conducted a bottom-up assessment of environmental emissions and economic characteristics for each coal power unit, while retirement decisions were guided by top-down climate target trajectories. Phaseout strategies consistent with 1.5 °C and 2 °C pathways were designed to evaluate the cost-benefit of coal power units.

We compared the future pathways of coal power capacity under the 1.5 °C and 2 °C targets with the actual operational capacity for each year. This process identifies the surplus capacity exceeding the climate target, which is then sequentially deducted from the actual operational capacity based on cost-benefit maximization decisions. This step is repeated iteratively to ensure that the operational capacity aligns with climate-compatible targets for specific years. The raw data in climate scenarios were obtained from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Working Group III (WGIII) Scenario Database, hosted by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis68, which provided coal power capacity pathways under 1.5 °C and 2 °C scenarios. We use categories C1 (no or limited overshoot) and C2 (high overshoot) for 1.5 °C consistent pathways, and Categories C3 (likely below 2 °C) and C4 (below 2 °C) for 2 °C pathways (see Supplementary Table 1 for descriptions). Power scenarios from seven major integrated assessment models (GCAM, AIM/CGE, MESSAGE-GLOBIOM, IMAGE, REMIND, WITCH, and POLES) were employed to analyze coal power pathways across 379 recent scenarios, encompassing trajectories aimed at limiting average global warming to 1.5 °C and 2 °C by the end of the Century. Since each model generates parameter outputs at 5- or 10-year intervals, we employed second-order polynomial interpolation to derive annual data. The median and range of the results are presented in Fig. 1c, d. We assumed the current operational and pipeline coal fleet would not transition to units equipped with Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage, biomass energy, or natural gas.

Additionally, India’s coal power units are relatively new, with an average operational lifetime of about 17 years. We adopt a typical coal power plant assumed lifetime of 40 years1,69,70, and conduct an uncertainty analysis by extending the assumed lifetime range to 35–45 years. The analysis encompassed the operational capacity in the baseline year of 2020 and the pipeline capacity for the years after that.

Characteristics of coal plants

We utilized unit-level data from the World Electric Power Plants (WEPP) database by S&P Global Platts71, which was cross-validated with the Global Energy Monitor database72, to analyze currently operational coal-fired power plants in India. The unit-level information includes the vintage year, installed capacity, coal type, and location. For units without online years, we estimate the median value of all fleets. Since the WEPP database does not include latitude and longitude information for power plants, we used Google Earth to map each unit’s location based on the physical addresses provided in the WEPP database (Supplementary Fig. 2). And for a few small units that were not visible on satellite imagery, we approximated their location using the geographical coordinates of the respective administrative district. Besides, our unit-level inventory includes 1305 operations (operating in the baseline year of 2020) and 113 pipelines (planned or under construction before 2030) in India, with a combined installed capacity of 233 GW and 53 GW, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Uncertainty analysis

Since the model includes multiple key parameters, we conducted a quantitative uncertainty analysis of them and their impacts on multidimensional outcomes, including assumed lifetime, SCC, capacity factor, and discount rate. The assumed lifetime range was extended to 35–45 years, and the capacity factor was conducted with a ±5% variation. Discount rates were applied to convert future benefits and costs into present values, enabling comparability of cost-benefit outcomes over time. In our model, the discount rate applies to multiple dimensions, including carbon benefits, health benefits, taxes, employment, plant profits, and stranded assets. By defining parameter ranges and performing iterative simulations, we explored the extent to which variations in assumptions influence the results. The specific ranges for each parameter are provided in Supplementary Table 9. Additionally, we performed a comprehensive assessment based on the assumed lifetime range of 35–45 years, incorporating the uncertainty of various parameters. The results of the uncertainty analysis are presented in Supplementary Figs. 9–12.

Data availability

The unit-level data are collected from the World Electric Power Plants database (https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/)71 and the Global Energy Monitor database (https://globalenergymonitor.org/zh-CN/projects/global-coal-plant-tracker/)72. Raw data for climate scenarios are from the IPCC AR6 WGIII Scenarios Database68. The base maps used in this study were generated using Esri-standardized datasets within ArcGIS 10.8. All geospatial processing and visualization were performed by the authors. Map images © Esri and its licensors. Used under license. The data that support the other findings within this article can be obtained from the author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used to process all modeling results and create all related images is publicly available on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1422951073. The model was written in Python (version 3.11.7), and optimization modeling was performed using the Gurobi solver (Version 10.0.3): https://www.gurobi.com/. Spatial data analysis was carried out using the Geopandas package (Version 0.14.3): https://geopandas.org/en/v0.14.3/.

References

Yang, J. & Urpelainen, J. The future of India’s coal-fired power generation capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 226, 904–912 (2019).

Crippa, M. et al. Fossil CO2Emissions of All World Countries-2020 Report. 1–244 (Luxembourg: European Commission, 2020).

Chakravarty, S. & Somanathan, E. There is no economic case for new coal plants in India. World Dev. Perspect. 24, 100373 (2021).

Climate Action Tracker. Country Summary India. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/india/ (2024).

Cui, R. Y. et al. Quantifying operational lifetimes for coal power plants under the Paris goals. Nat. Commun. 10, 4759 (2019).

Ordonez, J. A. et al. India’s just energy transition: Political economy challenges across states and regions. Energy Policy 179, 113621 (2023).

Binsted, M. et al. Stranded asset implications of the Paris agreement in Latin America and the Caribbean. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044026 (2020).

Pfeiffer, A. et al. Committed emissions from existing and planned power plants and asset stranding required to meet the Paris Agreement. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 054019 (2018).

von Dulong, A. Concentration of asset owners exposed to power sector stranded assets may trigger climate policy resistance. Nat. Commun. 14, 6442 (2023).

Edwards, M. R. et al. Quantifying the regional stranded asset risks from new coal plants under 1.5. C. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 024029 (2022).

Montrone, L., Ohlendorf, N. & Chandra, R. The political economy of coal in India – evidence from expert interviews. Energy Sustain. Dev. 61, 230–240 (2021).

Aldy, J. E. et al. Keep climate policy focused on the social cost of carbon. Science 373, 850–852 (2021).

Wang et al. Estimates of the social cost of carbon: a review based on meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 209, 1494–1507 (2019).

West, J. J. et al. Co-benefits of global greenhouse gas mitigation for future air quality and human health. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 885–889 (2013).

Cropper, M. et al. The mortality impacts of current and planned coal-fired power plants in India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2017936118 (2021).

The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (2025).

Ricke, K. et al. Country-level social cost of carbon. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 895–900 (2018).

Richard, S. J. T. Social cost of carbon estimates have increased over time. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 532–536 (2023).

Government of India, Ministry of Power. 500 GW Nonfossil Fuel Target. https://powermin.gov.in/en/content/500gw-nonfossil-fuel-target (2023).

Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century. Renewables 2024 Global Status Report India. https://www.ren21.net/gsr-2024/ (2024).

Ministry of Coal, Government of India. Production and Annual Consumption of Coal in the Country. https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1908840 (2023).

Global Energy Monitor. India Enters an Unnecessary Coal Plant Permitting Spree in 2023. https://globalenergymonitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/India-New-Coal-Permits-August-2023.pdf (2023).

Vinichenko, V. et al. Phasing out coal for 2 °C target requires worldwide replication of most ambitious national plans despite security and fairness concerns. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 014031 (2023).

Maamoun, N. et al. Identifying coal-fired power plants for early retirement. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 126, 109833 (2020).

Fofrich, R. et al. Early retirement of power plants in climate mitigation scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094064 (2020).

Cui, R. Y. et al. A plant-by-plant strategy for high-ambition coal power phaseout in China. Nat. Commun. 12, 1468 (2021).

Muttitt, G. et al. Socio-political feasibility of coal power phase-out and its role in mitigation pathways. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 140–147 (2023).

Figueira, J., Greco, S. & Ehrogott, M. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys (Springer, New York, 2005).

Malik, A. et al. Reducing stranded assets through early action in the Indian power sector. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094091 (2020).

Kefford, B. M. et al. The early retirement challenge for fossil fuel power plants in deep decarbonization scenarios. Energy Policy 119, 294–306 (2018).

Lu, Y. et al. Plant conversions and abatement technologies cannot prevent stranding of power plant assets in 2 °C scenarios. Nat. Commun. 13, 806 (2022).

Yan, X. et al. Cost-effectiveness uncertainty may bias the decision of coal power transitions in China. Nat. Commun. 15, 2272 (2024).

Diakoulaki, D. & Karangelis, F. Multi-criteria decision analysis and cost-benefit analysis of alternative scenarios for the power generation sector in Greece. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 11, 716–727 (2007).

Steckel, J. C., Edenhofer, O. & Jakob, M. Drivers for the renaissance of coal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E3775–E3781 (2015).

Steckel, J. C. & Jakob, M. To end coal, adapt to regional realities. Nature 607, 29–31 (2022).

Luderer, G. et al. Residual fossil CO2 emissions in 1.5–2°C pathways. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 626–633 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Quantifying stranded assets of the coal-fired power in China under the Paris Agreement target. Clim. Policy 23, 11–24 (2023).

Gao, M. et al. The impact of power generation emissions on ambient PM2.5 pollution and human health in China and India. Environ. Int. 121, 250–259 (2018).

Venkataraman, C. et al. Source influence on emission pathways and ambient PM2.5 pollution over India (2015–2050). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 8017–8039 (2018).

Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India. Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme: National Programme on High Efficiency Solar PV Modules. https://mnre.gov.in/en/production-linked-incentive-pli/ (2024).

Umamaheswaran, S. & Rajiv, S. Financing large scale wind and solar projects—A review of emerging experiences in the Indian context. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 48, 166–177 (2015).

Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India. Physical Achievements India. https://mnre.gov.in/physical-progress/ (2025).

Pizer, W. et al. Using and improving the social cost of carbon. Science 346, 1189–1190 (2014).

Global Energy Monitor. Estimating Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal Plants. https://www.gem.wiki/Estimating_carbon_dioxide_emissions_from_coal_plants (2023).

Central Electricity Authority, Government of India. Monthly Reports Archive. https://cea.nic.in/monthly-reports-archive/?lang=en (2024).

Central Electricity Authority, Government of India. CDM-CO2Baseline Database. https://cea.nic.in/cdm-co2-baseline-database/?lang=en (2024).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/ (2006).

Southerland, V. A. et al. Global urban temporal trends in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and attributable health burdens: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e139–e146 (2022).

Burnett, R. et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9592–9597 (2018).

Deshmukh, R. & Chatterjee, S. Toward a low-carbon transition in India. Science 378, 595–596 (2022).

Diaz, D. & Moore, F. Quantifying the economic risks of climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 774–782 (2017).

Oberschelp, C., Pfister, S. & Hellweg, S. Globally regionalized monthly life cycle impact assessment of particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 16028–16038 (2020).

Anand, S. & Hanson, K. Disability-adjusted life years: a critical review. J. Health Econ. 16, 685–702 (1997).

Rauner, S. et al. Coal-exit health and environmental damage reductions outweigh economic impacts. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 308–312 (2020).

Haacker, M., Hallett, T. B. & Atun, R. On discount rates for economic evaluations in global health. Health Policy Plan. 35, 107–114 (2020).

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. GAINS South Asia Online. https://gains.iiasa.ac.at/gains/docu.INN/index.menu?open=none (2024).

International Institute for Sustainable Development. India’s Energy Transition: Mapping Subsidies to Fossil Fuels and Clean Energy in India. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/india-energy-transition.pdf (2017).

International Institute for Sustainable Development. The Evolution of the Clean Energy Cess on Coal Production in India. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/stories-g20-india-en.pdf (2018).

Ministry of Finance, Government of India. Climate Watch India Country Platform. https://indiaclimateexplorer.org/climate-policies/CEC/overview (2024).

Prakash, V., Ghosh, S. & Kanjilal, K. Costs of avoided carbon emission from thermal and renewable sources of power in India and policy implications. Energy 200, 117522 (2020).

Pai, S. et al. Meeting well-below 2°C target would increase energy sector jobs globally. One Earth 4, 1026–1036 (2021).

International Labour Organization. Towards an India Wage Report 2017. https://ilo.primo.exlibrisgroup.com (2017).

Sasse, J. P. & Trutnevyte, E. A low-carbon electricity sector in Europe risks sustaining regional inequalities in benefits and vulnerabilities. Nat. Commun. 14, 2205 (2023).

Central Electricity Authority, Government of India. Domestic Electricity LT Tariff Slabs and Rates for all States in India in 2016. https://www.bijlibachao.com/news/domestic-electricity-lt-tariff-slabs-and-rates-for-all-states-in-india-in.html (2017).

Mallah, S. & Bansal, N. K. Allocation of energy resources for power generation in India: Business as usual and energy efficiency. Energy Policy 38, 1059–1066 (2010).

Johnson, N. et al. Stranded on a low-carbon planet: Implications of climate policy for the phase-out of coal-based power plants. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 90, 89–102 (2015).

Tong, D. et al. Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5°C climate target. Nature 572, 373–377 (2019).

Byers, E. et al. AR6 scenarios database. Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5886912 (2022).

Shearer, C., Fofrich, R. & Davis, S. J. Future CO2 emissions and electricity generation from proposed coal-fired power plants in India. Earth’s Future 5, 408–416 (2017).

Shrimali, G. Managing power system flexibility in India via coal plants. Energy Policy 150, 112061 (2021).

S&P Global. World Electric Power Plant Database. https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/commodity/electric-power (2020).

Global Energy Monitor. Global Coal Plant Tracker. https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-coal-plant-tracker/ (2025).

Long, X. et al. Codes for “Ambitious climate targets can make the phaseout of India’s coal-fired power plants cost-beneficial”. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14229510 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 72061147003, Y. W.; no. 52022023, Y. W.; no. 52100210, B. C.) and Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (no. 24KXZNA15, Y. W.). J. M. also acknowledges support from the European Union under the grant agreement no. 101137905 (PANTHEON).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., J.M., B.C., X.L., and P.C. developed the research idea and framework. X.L., B.C., H.X., and J.M. developed models, provided guidance on methods, and managed the estimation process. X.L. did coding, analyzing, and visualization. X.L., Y.W., J.M., B.C., M.D., and P. C. reviewed the results and manuscript. X.L., B.C., M.D., H.X., P.C., J.M., and Y.W. contributed to the development of the manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Long, X., Chen, B., Dai, M. et al. Ambitious climate targets can make the phaseout of India’s coal-fired power plants cost-beneficial. Nat Commun 16, 11594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66580-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66580-4