Abstract

N-fluoroalkyl compounds are highly valuable in medicinal chemistry. While carbonimidic difluorides have been recognized as valuable intermediates for N-CF3 compounds synthesis, their broader synthetic potential remains largely unexplored due to the limitations of current methodologies, particularly in expanding the scope of N-fluoroalkyl derivatives. Herein, we report the design and synthesis of azidodifluoromethyl imidazolium reagents that enable the in situ generation of carbonimidic difluorides. These intermediates undergo a series of controlled transformations, including chlorination, fluorination, monodefluorination, didefluorination, and subsequent derivatization of N-chlorodifluoromethyl compounds, providing an efficient strategy for the synthesis of structurally diverse N-fluoroalkane and amine derivatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

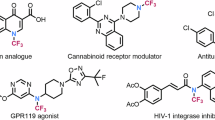

The N-fluoroalkyl compounds have garnered increasing attention due to their distinctive physicochemical properties and broad applicability across pharmaceutical chemistry, agrochemicals, and materials science1,2,3,4,5,6. Notably, N-CF3 and N-CF2H motifs play a crucial role in the design of bioactive molecules, often enhancing metabolic stability, lipophilicity, and bioavailability. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, numerous bioactive molecules incorporate N-fluoroalkyl functionalities7,8,9,10,11, underscoring their significance in drug discovery and development.

Carbonimidic difluorides play a pivotal role in current strategies for synthesizing N-CF3 compounds12,13,14,15,16,17,18. However, existing approaches19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 for their synthesis and modification fail to fully exploit their synthetic potential. Typically, carbonimidic difluorides are prepared either by oxidation of isothiocyanates or isocyanides (Fig. 1, b)29,30,31,32,33, or through chlorine-to-fluorine substitution from carbonimidic dichlorides19,34,35,36,37,38. The pioneering work of Schoenebeck20,21,22,23,24,25, Wilson26, Yi27, and Tlili28 has significantly advanced the application of carbonimidic difluorides in the synthesis of N-CF3 compounds, introducing a series of one-pot transformations from isothiocyanates and AgF. Additionally, carbonimidic difluorides can be generated through defluorination of N-CF3 compounds, which is often regarded as a side reaction19,27. Despite these advances, current methodologies predominantly rely on substituted amines as starting materials for functional group interconversion, often requiring harsh reaction conditions, highly toxic reagents, or excessive fluorine sources, thereby limiting their scope for broader and more versatile applications.

Notably, in 1967, the Ogden group reported a reaction that generated difluoromethylenimino radicals by reacting tetrafluoro-2,3-diaza-1,3-butadiene with hexafluoropropylene (Fig. 1, c)39. This process enables radical amination with polyfluoro-olefins to yield carbonimidic difluorides, offering a route to these compounds without requiring excess fluorine sources. However, limited by unstable difluoromethylenimino radical precursors and harsh activation conditions, the substrate scope of the reaction and related derivatization have not been fully explored. Follow-up studies on difluoromethylenimino radicals have not resolved these issues40,41,42. Thus, we aim to design a bench-stable reagent that can generate difluoromethylenimino radicals, synthesize carbonimidic difluorides under mild conditions, and produce a variety of N-fluoroalkyl derivatives in a one-pot process.

Inspired by the work of Schoenebeck24 and Beier14,43, we envisioned that an azidodifluoromethyl reagent containing a leaving group could undergo single-electron transfer (SET) upon photoexcitation (Fig. 1, d). This process would release difluoromethylenimino radicals, which then react with radical acceptors to generate carbonimidic difluorides in situ. Since this process does not require an excess fluorine source, the carbonimidic difluorides can undergo further transformations such as chlorination (the AgF system is not compatible with chloride ions20,26), fluorination, monodefluorination, and didefluorination reactions, yielding the corresponding N-fluoroalkyl and amine compounds. Our previous work has established that imidazolium salts exhibit significant reactivity in the generation of fluorinated radicals44,45,46,47. In this work, we report the synthesis and application of bench-stable azidodifluoromethyl imidazolium reagents (IMADFs), with the aim of enabling the efficient synthesis of diverse N-fluoroalkyl compounds.

Results

Synthesis and reactivity study of IMADFs

Starting from CF2Br2, the compound undergoes two or three nucleophilic substitutions48, yielding a series of IMADFs. In order to test the reactivity of these reagents, we designed a radical cyclization reaction using phenylvinylbenzoyl chloride for N-fluoroalkyl pyridone synthesis. The 2-pyridone scaffold is commonly found in pharmaceuticals and natural products49,50,51,52. N-fluoroalkyl-substituted 2-pyridones have been shown to enhance the biological activity of molecules10,11. In parallel, chlorodifluoromethyl groups are also widely used in bioactive molecules53,54 and can be further modified to synthesize a variety of difluoromethylene derivatives55,56,57. We began our study with the reaction of 2-(1-phenylvinyl)benzoyl chloride (1a) and IMADF-1 in anhydrous dichloromethane catalyzed by fac-Ir(ppy)3 under 30 W blue LED irradiation. To our delight, the 2-(chlorodifluoromethyl)−4-phenylisoquinolin-1(2H)-one product (2a) was produced after 12 hours in a 30% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Next, we explored the use of different photocatalysts (entries 2-5) and found that Ir(piq)3 improved the yield. Other IMADFs were also tested (entries 6-8), with IMADF-1 being the most effective. Considering that high concentrations might lead to the formation of various byproducts20,35, we reduced the concentration, which significantly improved the yield (entries 9–12). Additionally, we observed that the yield varied with light intensity (entries 13–14), with the 90 W blue light source providing the best results, achieving a 78% GC yield and a 72% isolated yield for the target product. Control experiments confirmed that both the light source and the photocatalyst were essential for these transformations (entries 15 and 16).

With the optimal conditions established, the substrate scope of chlorodifluoromethylamination was examined (Fig. 2). A broad range of benzoyl chlorides (1) with electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents smoothly underwent these transformations to afford the corresponding products (2b-2f) in 53-84% yields. Other aromatic rings, such as naphthalene afforded the corresponding product (2g) in 68% yield. Heteroaromatic acyl chlorides also participated in the reaction, affording the corresponding N-chlorodifluoromethyl-2-pyridone in moderate to good yields, examples include substrates derived from thiophene (2 h), furan (2i), oxazole (2j), imidazole (2k), thiazole (2 l), pyridine (2 m). Other disubstituted and trisubstituted phenylvinylbenzoyl chlorides also demonstrated the feasibility of the reaction (2n and 2o). Notably, monosubstituted alkenylbenzoyl chlorides also successfully yielded the target products in synthetically useful yields (2p-2s). To further demonstrate the potential of this protocol in medicinal chemistry, we synthesized 2-chlorodifluoromethyl-1(2H)-isoquinolone derivatives (2t and 2u), which may function as bioisosteric building blocks for some drugs. Trotabresib, an oral potent inhibitor of bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) proteins, is used for the treatment of high-grade glioma58. Using our strategy, its N-CF2Cl bioisostere was synthesized in 65% yield (2v). The mild conditions tolerated many functional groups, including halides (2b, 2m, 2t, 2u), ethers (2f), nitriles (2c), trifluoromethyl groups (2d, 2s), and sulfonyl groups (2 v). Through the employment of phenylvinylbenzoyl fluorides in the reaction, the corresponding N-CF3 compounds were successfully synthesized. While the yield was less than ideal, the products were still obtained in synthetically useful quantities (3a-3e, 3v).

Reaction conditions: a1a (0.2 mmol in DCM), IMADF-1 (0.3 mmol), Ir(piq)3 (0.006 mmol), 90 W blue LED, 12 h under Ar. bAdditional NaCl (0.2 mmol) was added to the reaction. c1’a (0.2 mmol in DCM), IMADF-1 (0.3 mmol), Ir(piq)3 (0.006 mmol), 4-pyrrolidinopyridine (0.02 mmol), 90 W blue LED, 12 h under Ar.

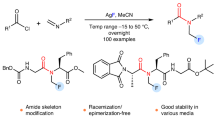

Carbonimidic difluorides not only underwent chlorination and fluorination reactions, but also tunable defluorination reactions (Fig. 3). When styrene was used as radical acceptor, the intermediate imine was stable enough to be detected in the reaction system (see SI for details). Subsequently, secondary amines were used as nucleophiles. The radical addition followed by selective defluorination of carbonimidic difluorides led to the corresponding fluoroformamidines. Such types of moieties have been less studied due to their limited approaches59. We applied our protocol to various styrene derivatives—including electron-withdrawing (6b), electron-donating (6c), disubstituted (6a-6d), trisubstituted (6e), and monosubstituted (6f)—affording the corresponding fluoroformamidines in 36%-83% yields. Besides morpholine, various nitrogen nucleophiles were evaluated in the monodefluorination reaction. Pyrrolidine (6g) and acyclic secondary amines (6h, 6i) underwent smooth transformation, affording fluoroformamidines in moderate to good yields. Additionally, azoles such as imidazole (6j), pyrazole (6k), pyrrole (6l) and 1,2,3-triazole (6 m) showed reactivity under the conditions, yielding analogous products in comparable yields. The defluorination could proceed further to produce isocyanate (7a), isothiocyanate (7b), and isoselenocyanate (7c), which are important synthons for amine derivatives.

Reaction conditions: a4 (0.2 mmol), IMADF-1 (0.3 mmol), fac-Ir(ppy)₃ (0.006 mmol), 30 W blue LED, 2 h under Ar, then added secondary amine (0.3 mmol), triethylamine (0.3 mmol). bThe ratio of E/Z isomers was determined by NMR. c0.5 mmol IMADF-1 was used and stirred for 5 h. d The ratio of E/Z isomers was determined through isolated yield. epyrrole sodium salt as nucleophile. f The ratio of p1/p2 isomers was determined by NMR. gsilica gel (200 mg) as nucleophile and corresponding urea 7a’ was isolated. hNa2S (0.4 mmol) as nucleophile. iNa2Se (0.4 mmol) as nucleophile.

Synthetic applications of 2a

To demonstrate the practical utility of this chlorodifluoromethylamination, a series of derivatizations were carried out (Fig. 4). A rapid chlorine-to-fluorine substitution was successfully achieved. Within 15 min, N-CF2Cl (2a) was converted to N-CF3 (3a) using KF as the fluorine source. The corresponding difluoromethyl (8) and difluoromethylene (9) compounds were also obtained via radical dechlorination in the presence of AIBN. These results demonstrate the potential of this protocol for late-stage diversification of fluorinated bioactive compounds.

Mechanistic studies

Based on our experimental results and precedents in the literature24, a plausible mechanism for the chlorodifluoromethylamination reaction is proposed (Fig. 5). Initially, photoexcitation of IrIII generates IrIII*. This is followed by a single-electron transfer (SET) reduction of IMADF-1 (E1/2red = -1.05 V vs SCE; see SI for details) with IrIII*, leading to the formation of radical Int-1 and IrIV [Ir(piq)₃, E1/2IV/III* = -1.42 V vs SCE, see SI for details]. Subsequently, the radical Int-1 undergoes N-N bond cleavage to produce the radical Int-2. Next, the imidazole derivative is removed from Int-2 yields Int-3 (difluoromethylenimino radical), which then attacks styrene to furnish the radical Int-4. This intermediate could undergo an intramolecular ring closure reaction and be oxidized by IrIV to generate the cationic intermediate Int-5. Finally, deprotonation of Int-5 results in the formation of N-CF2Cl isoquinolone 2.

To support the above mechanistic hypothesis, the control experiments were performed. Using diphenylethylene 4a as a trapping agent, the difluoromethylenimino radical was captured, and the formation of adduct 5a was confirmed by 19F-NMR [δ -47.29 and δ -60.29 ppm], GC-MS (m/z = 243.1), HRMS [ESI (m/z) calcd for C15H12F2N (M + H)+ 244.0932, found 244.0931] and IR (C = N: 1805.62 cm⁻¹) (Fig. 6a, see SI for details). Radical clock experiment using cyclopropane 10 and 2 equivalents of KF under the standard chlorodifluoromethylamination conditions resulted in the ring-opening product 11 (28% yield, Fig. 6b). When Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbpy)PF6 (E1/2IV/III* = -0.89 V vs SCE)60 was employed as the photocatalyst, intramolecular cyclization product 12 was predominantly formed, with only trace amounts of the SET product 5a. These results demonstrate that under photoexcitation conditions with weak reducing capacity, nitrene species are generated from cationic IMADF-1 via an energy transfer (EnT) process (Fig. 6c)24,61. The consistently low yields (<5%) observed in both Table 1 (entry 3) and Supplementary Table 2 (entries 4-6) further support this mechanistic pathway. Additional experimental results demonstrate that the neutral IMADF-4 can also undergo the EnT process, yielding the cyclized product 13 instead of 5a (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that the SET process serves as the primary pathway for the chlorodifluoromethylamination reaction. Furthermore, the SET process exhibits a faster reaction rate compared to the EnT process. Luminescence quenching experiments reveal that the excited state photocatalyst (PC*) is quenched by IMADF-1, involving an oxidative quenching catalytic cycle (Fig. 6d). Moreover, difluoromethylenimino radical was confirmed in the photolysis of IMADF-1 via the Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectrum of PBN − NCF2 (Fig. 6e, hyperfine coupling constants: ANα = 7.30 G, AHβ = 5.67 G, ANγ = 3.04 G, AF1δ = AF2δ = 5.67 G, g = 2.0066, see SI for details).

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully developed a highly reactive, bench-stable solid reagent capable of generating difluoromethylenimino radicals under visible-light catalysis. These radicals can then react with radical acceptors to form the corresponding carbonimidic difluorides. Through strategic substrate design, we programmed the synthesis of these compounds, enabling the subsequent preparation of various N-fluoroalkyl compounds and amine derivatives via chlorination, fluorination, and defluorination reactions (mono- and di-). We believe that this protocol will serve as a powerful tool for the preparation of valuable fluorinated amines. Ongoing studies of these reagents are underway in our laboratory.

Methods

General Procedure for Photocatalytic Chlorodifluoromethylamination, Trifluoromethylamination. Unless otherwise specified, all products were obtained using the following methods.

General procedure

Under argon, to an 8 mL flask was added Ir(piq)3 (3 mol%), IMADF-1 (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), 4 mL 0.05 M acyl chloride or acyl fluoride (in DCM) at room temperature. After that, the tube was exposed to a 90 W blue LED and stirred for 12 h until the reaction was completed as monitored by GC-MS analysis. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel or preparative TLC to give the desired product 2 and 3.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Carbonimidic Difluorides and Their Defluorination.

General procedure

Under argon, fac-Ir(ppy)₃ (3 mol%) and IMADF-1 (0.3–0.5 mmol, 1.5–2.5 equivalents) were added to an 8 mL flask. If 4 was solid, it was also added to the flask. A mixture of DCE and AcOiPr (1 mL each) was then added. If 4 was liquid, it was added directly to the flask at room temperature. The reaction mixture was exposed to a 30 W blue LED for 2–5 h, until completion, as monitored by GC-MS analysis. Next, the CH₃CN or THF solution of the nucleophile, along with TEA (triethylamine), was added to the reaction tube. The mixture was stirred at room temperature until the intermediate was fully consumed. Finally, the reaction mixture was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel or preparative TLC to yield the desired product.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files, or from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray structural data of IMADF-1 is deposited in CCDC (No. 2333867 see Supplementary Table 1 for details). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Meanwell, N. A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 61, 5822–5880 (2018).

Clayden, J. Fluorine and amide groups together at last. Nature 573, 37–38 (2019).

Schiesser, S. et al. N-trifluoromethyl amines and azoles: An underexplored functional group in the medicinal chemist’s toolbox. J. Med. Chem. 63, 13076–13089 (2020).

Schiesser, S., Cox, R. J. & Czechtizky, W. The powerful symbiosis between synthetic and medicinal chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 13, 941–944 (2021).

Lei, Z., Chang, W., Guo, H., Feng, J. & Zhang, Z. A Brief review on the synthesis of the N-CF3 motif in heterocycles. Molecules 28, 3012 (2023).

Cui, G. et al. Discovery of N-trifluoromethylated noscapines as novel and potent agents for the treatment of glioblastoma. J. Med. Chem. 68, 247–260 (2025).

Asahina, Y. et al. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of the 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid derivatives having a trifluoromethyl group as a novel N-1 Substituent. J. Med. Chem. 48, 3443–3446 (2005).

Sahu, K. K., Ravichandran, V., Mourya, V. K. & Agrawal, R. K. QSAR analysis of caffeoyl naphthalene sulfonamide derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res. 15, 418–430 (2007).

Kubo, O. et al. Discovery of a novel series of GPR119 agonists: Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of N-(piperidin-4-yl)-N-(trifluoromethyl)pyrimidin-4-amine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 41, 116208 (2021).

Chowdhury, M. A. et al. Synthesis of celecoxib analogues possessing a N-difluoromethyl-1,2-dihydropyrid-2-one 5-lipoxygenase pharmacophore: biological evaluation as dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxygenase with anti-inflammatory activity. J. Med. Chem. 52, 1525–1529 (2009).

Chowdhury, M. A. et al. Synthesis of 1-(methanesulfonyl- and aminosulfonylphenyl)acetylenes that possess a 2-(N-difluoromethyl-1,2-dihydropyridin-2-one) pharmacophore: evaluation as dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxygenase with anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 584–588 (2009).

Liu, S., Huang, Y., Wang, J., Qing, F. L. & Xu, X. H. General synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl compounds with N-trifluoromethyl hydroxylamine reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1962–1970 (2022).

Crousse, B. Recent advances in the syntheses of N-CF3 scaffolds up to their valorization. Chem. Rec. 23, e202300011 (2023).

Baris, N. et al. Photocatalytic generation of trifluoromethyl nitrene for alkene aziridination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202315162 (2024).

Fleetwood, T. D., Kerr, W. J. & Mason, J. Copper-mediated N-trifluoromethylation of O-benzoylhydroxylamines. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202303314 (2024).

Zhang, R. Z., Gao, Y. F., Yu, J. X., Xu, C. & Wang, M. N-CF3 imidoyl chlorides: scalable N-CF3 nitrilium precursors for the construction of N-CF3 compounds. Org. Lett. 26, 2641–2645 (2024).

Zhang, R. Z., Liu, Y., Xu, C. & Wang, M. Direct synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl amides via photocatalytic trifluoromethylamidation,. Nat. Commun. 16, 4964 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. Nitrogen-Based organofluorine functional molecules: synthesisand applications. Chem. Rev. 125, 4603–4764 (2025).

Sheppard, W. A. N-fluoroalkylamines I. Difluoroazomethines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87, 4338–4341 (1965).

Scattolin, T., Bouayad-Gervais, S. & Schoenebeck, F. Straightforward access to N-trifluoromethyl amides, carbamates, thiocarbamates and ureas. Nature 573, 102–107 (2019).

Bouayad-Gervais, S., Scattolin, T. & Schoenebeck, F. N-trifluoromethyl hydrazines, indoles and their derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 11908–11912 (2020).

Turksoy, A., Scattolin, T., Bouayad-Gervais, S. & Schoenebeck, F. Facile access to AgOCF3 and its new applications as a reservoir for OCF2 for the direct synthesis of N-CF3, aryl or alkyl carbamoyl fluorides. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 2183–2186 (2020).

Nielsen, C. D., Zivkovic, F. G. & Schoenebeck, F. Synthesis of N-CF3 alkynamides and derivatives enabled by Ni-catalyzed alkynylation of N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 13029–13033 (2021).

Bouayad-Gervais, S. et al. Access to cyclic N-trifluoromethyl ureas through photocatalytic activation of carbamoyl azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6100–6106 (2022).

Zivkovic, F. G., Nielsen, C. D.-T. & Schoenebeck, F. Access to N-CF3 formamides by reduction of N-CF3 carbamoyl fluorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213829 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Synthesis of N-trifluoromethyl amides from carboxylic acids. Chem 7, 2245–2255 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. General access to N-CF3 secondary amines and their transformation to N-CF3 sulfonamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212115 (2022).

Yang, Y., Saffon-Merceron, N., Vantourout, J. C. & Tlili, A. Novel N(SCF3)(CF3)-amines: synthesis, scalability and stability. Chem. Sci. 14, 3893–3898 (2023).

Stevens, T. E. Reaction of isothiocyanates and iodine pentafluoride. Tetrahedron Lett. 17, 16–18 (1959).

Stevens, T. E. Preparation and some reactions of thiobis-N-(trifluoromethyl)amines. J. Org. Chem. 26, 3451–3457 (1961).

Ruppert, I. Organyl isocyanid difluoride R-N=CF2 durch direkt fluorierung von isocyaniden. Tetrahedron Lett. 21, 4893–4896 (1980).

Wu, J. Y. et al. N-Halosuccinimide enables cascade oxidative trifluorination and halogenative cyclization of tryptamine-derived isocyanides. Nat. Commun. 15, 8917 (2024).

Fu, J. L. et al. A mild and practical approach to N-CF3 secondary amines via oxidative fluorination of isocyanides. Nat. Commun. 16, 4873 (2025).

Petrov, K. A. & Neimyscheva, A. A. Karbilamingalogenidy. 2. sintez vtorichnykh aminovs triftormetilnoi gruppoi. Zh. Obsh. Khim. 29, 2169–2172 (1959).

Leverkusen, E. K. Preparation and properties of substances with N- or S-perhalogenomethyl groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 5, 848 (1966).

Kühle, E., Anders, B., Klauke, E., Tarnow, H. & Zumach, G. Neuere methoden der präparativen organischen chemie. umsetzungen von isocyaniddihalogeniden und ihren derivaten. Angew. Chem. 81, 18–32 (1969).

Savchenko, T. I., Petrova, T. D., Platonov, V. E. & Yakobson, G. G. Formation of 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorophenylcarbonimidoyl dichloride by copyrolysis pentafluoroaniline with chloroform. J. Fluor. Chem. 9, 505–508 (1977).

Spennacchio, M. et al. A unified flow strategy for the preparation and use of trifluoromethyl-heteroatom anions. Science 385, 991–999 (2024).

Ogden, P. H. & Mitsch, R. A. Reactions of the difluoromethylenimino radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89, 3868–3871 (1967).

Ogden, P. H. The photolysis of perfluoro-2,3-diazabuta-l,3-diene and perfluoroacyl fluorides. J. Org. Chem. 33, 2518–2521 (1968).

Zheng, Y. Y. & DesMarteau, D. D. Synthesis of 1,1-difluoro-2-azaperhalo-1-butenes and their conversion to oxaziridines. J. Org. Chem. 48, 4844–4847 (1983).

Bauknight, C. W. Jr. & DesMarteau, D. D. Reactions of N-bromodifluoromethanimine. J. Org. Chem. 53, 4443–4447 (1988).

Blastik, Z. E. et al. Azidoperfluoroalkanes: Synthesis and application in copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 346–349 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Integrated redox-active reagents for photoinduced regio- and stereoselective fluorocarboborylation. Nat. Commun. 11, 2572 (2020).

Huang, M. et al. A photoinduced transient activating strategy for late-stage chemoselective C(sp(3))-H trifluoromethylation of azines. Chem. Sci. 13, 11312–11319 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. A practical fluorosulfonylating platform via photocatalytic imidazolium-based SO2F radical reagent. Nat. Commun. 13, 3515 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Photoredox-catalyzed stereo- and regioselective vicinal fluorosulfonyl-borylation of unsaturated hydrocarbons. Chem. Sci. 14, 13893–13901 (2023).

Mykyta, Z. et al. From boom to bloom: synthesis of diazidodifluoromethane, its stability and applicability in the ‘click’ reaction. Chem. Commun. 61, 885 (2025).

Dolle, V. et al. A new series of pyridinone derivatives as potent non-nucleoside human immunodeficiency virus type 1 specific reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 38, 4679–4686 (1995).

Ando, M. et al. Discovery of pyridone-containing imidazolines as potent and selective inhibitors of neuropeptide Y Y5 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 6106–6122 (2009).

Jessen, H. J. & Gademann, K. 4-Hydroxy-2-pyridone alkaloids: Structures and synthetic approaches. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 1168–1185 (2010).

Fioravanti, R., Stazi, G., Zwergel, C., Valente, S. & Mai, A. Six years (2012-2018) of researches on catalytic EZH2 inhibitors: The Boom of the 2-Pyridone Compounds. Chem. Rec. 18, 1818–1832 (2018).

Vaas, S. et al. Principles and applications of CF2X moieties as unconventional halogen bond donors in medicinal chemistry, chemical biology, and drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 66, 10202–10225 (2023).

Yuan, W. J., Tong, C. L., Xu, X. H. & Qing, F. L. Copper-mediated oxidative chloro- and bromodifluoromethylation of phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23899–23904 (2023).

Guidotti, J., Schanen, V., Tordeux, M. & Wakselman, C. Reactions of (chlorodifluoromethyl)benzene and (chlorodifluoromethoxy)benzene with nucleophilic reagents. J. Fluor. Chem. 126, 443–447 (2005).

Wegert, A., Hein, M., Reinke, H., Hoffmann, N. & Miethchen, R. Chlorodifluoromethyl-substituted monosaccharide derivatives-radical activation of the carbon-chlorine-bond. Carbohydr. Res. 341, 2641–2652 (2006).

Lien, V. T. & Riss, P. J. Radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoroalkyl groups: scope and limitations. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 1 (2014).

Moreno, V. et al. Trotabresib, an oral potent bromodomain and extraterminal inhibitor, in patients with high-grade gliomas: A phase I, “window-of-opportunity” study. Neuro. Oncol. 25, 1113–1122 (2023).

Vogel, J. A., Miller, K. F., Shin, E., Krussman, J. M. & Melvin, P. R. Expanded access to fluoroformamidines via a modular synthetic pathway. Org. Lett. 26, 1277–1281 (2024).

Holmberg-Douglas, N. & Nicewicz, D. A. Photoredox-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. Chem. Rev. 122, 1925–2016 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Dong, X., Wu, Y., Li, G. & Lu, H. Visible-light-induced intramolecular C(sp2)-H amination and aziridination of azidoformates via a triplet nitrene pathway. Org. Lett. 20, 4838–4842 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22271147, 22401144, and 22471123). We gratefully acknowledge Heyin Li, Chao Sun, Yifan Li, Zhenlei Zou, and Mengjun Huang for their insightful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., W.Z., and Z.W. (王震) designed this project and analyzed the experiments. Z.W. (王震); Z.W. (王桢); J. L. and L.Y. carried out the experiments. X. G. conducted EPR experiments and data analysis. Z. W. (王震) and W.Z. wrote the manuscript. Y. P. and Y.W. directed the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Petr Beier, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Guo, X. et al. Bench-stable azidodifluoromethyl imidazolium reagents unlock the synthetic potential of carbonimidic difluorides. Nat Commun 16, 11537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66605-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66605-y