Abstract

How physical neuronal networks, bound by spatio-temporal locality constraints, can perform efficient credit assignment, remains an intriguing question. Both backward- and forward-propagation algorithms rely on assumptions that violate this locality in various ways. We introduce Generalized Latent Equilibrium (GLE), a framework for fully local spatio-temporal credit assignment in physical, dynamical neuronal networks. From an energy based on neuron-local mismatches, we derive neuronal dynamics via stationarity and parameter dynamics as gradient descent. The result is an online approximation of backpropagation through space and time in deep networks of cortical microcircuits with continuously active, local synaptic plasticity. GLE exploits dendritic morphology to enable complex information storage and processing in single neurons, as well as their ability to react in anticipation of their future input. This “prospective coding” enables the computation of spatio-temporal convolutions in the forward direction and the approximation of adjoint variables in the backward stream.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world in which we have evolved appears to lie in a Goldilocks zone of complexity: it is rich enough to produce organisms that can learn, yet also regular enough to be learnable by these organisms in the first place. Still, regular does not mean simple; the need to continuously interact with and learn from a dynamic environment in real-time faces these agents—and their nervous systems—with a challenging task.

One can view the general problem of dynamical learning as one of constrained minimization, i.e., with the goal of minimizing a behavioral cost with respect to some learnable parameters (such as synaptic weights) within these nervous systems, under constraints given by their physical characteristics. For example, in the case of biological neuronal networks, such dynamical constraints may include leaky integrator membranes and nonlinear output filters. The standard approach to this problem in deep learning (DL) uses stochastic gradient descent, coupled with some type of automatic differentiation (AD) algorithm that calculates gradients via reverse accumulation1,2. These methods are well-known to be highly effective and flexible in their range of applications.

If the task is time-independent, or can be represented as a time-independent problem, the standard error backpropagation (BP) algorithm provides this efficient backward differentiation3,4,5. We refer to this class of problems as spatial, as opposed to more complex spatio-temporal problems, such as sequence learning. For the latter, the solution to constrained minimization can be sought through a variety of methods. When the dynamics are discrete, the most commonly used method is backpropagation through time (BPTT)6,7. For continuous-time problems, optimization theory provides a family of related methods, the most prominent being the adjoint method (AM)8, Pontryagin’s maximum principle9,10, and the Bellman equation11.

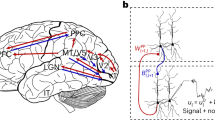

AM and BPTT have proven to be very powerful methods, but it is not clear how they could be implemented in physical neuronal systems that need to function and learn continuously, in real time, and using only information that is locally available at the constituent components12. Learning through AM/BPTT cannot be performed in real time, as it is only at the end of a task that errors and parameter updates can be calculated retrospectively (Fig. 1). This requires either storing the entire trajectory of the system (i.e., for all of its dynamical variables) until a certain update time, and/or recomputing the necessary variables during backward error propagation. While straightforward to do in computer simulations (computational and storage inefficiency notwithstanding), a realization in physical neuronal systems would require a lot of additional, complex circuitry for storage, recall and (reverse) replay. Additionally, it is unclear how useful errors can be represented and transmitted in the first place, i.e., which physical network components calculate errors that correctly account for the ongoing dynamics of the system, and how these then communicate with the components that need to change during learning (e.g., the synapses in the network). It is for these reasons that AM/BPTT sits firmly within the domain of machine learning (ML), and is largely considered not applicable for physical neuronal systems, both biological and artificial. (We use the term neuronal to differentiate between physical, time-continuous dynamical networks of neurons and their abstract, time-discrete artificial neural network (ANN) counterparts).

a To illustrate the different learning algorithms, we consider three neurons within a larger recurrent network. The neuron indices are indicative of the distance from the output, with neuron i + 1 being itself an output neuron, and therefore having direct access to an output error ei+1. b Information needed by a deep synapse at time t to calculate an update \({\dot{w}}_{i-1,k}^{(t)}\). Orange: future-facing algorithms such as BPTT require the states \({r}_{n}^{({t}^{+})}\) of all future times t+ and all neurons n in the network and can therefore only be implemented in an offline fashion. These states are required to calculate future errors \({e}_{n}^{({t}^{+})}\), which are then propagated back in time into present errors \({e}_{n}^{(t)}\) and used for synaptic updates \({\dot{w}}_{i-1,k}^{(t)}\propto {e}_{i-1}^{(t)}{r}_{k}^{(t)}\). Purple: past-facing algorithms, such as RTRL, store past effects of all synapses \({w}_{jk}^{({t}^{-})}\) on all past states \({r}_{n}^{({t}^{-})}\) in an influence tensor \({M}_{n,j,k}^{({t}^{-})}\). This tensor can be updated online and used to perform weight updates \({\dot{w}}_{i-1,k}^{(t)}\propto {\sum}_{n}{e}_{n}^{(t)}{M}_{n,i-1,k}^{(t)}\). Note that all synapse updates need to have access to distant output errors. Furthermore, the update of each element in the influence tensor requires the knowledge of distant elements and is thus itself nonlocal in space. Green: GLE operates exclusively on present states \({r}_{n}^{(t)}\). It uses them to infer errors \({e}_{n}^{(t)}\) that approximate the future backpropagated errors of BPTT.

Instead, theories of biological (or bio-inspired) spatio-temporal learning focus on other methods, either by using reservoirs and foregoing the learning of deep weights altogether, or by using direct and instantaneous output error feedback, transmitted globally to all neurons in the network, as in the case of FORCE13 and FOLLOW14. Alternatively, the influence of synaptic weights on neuronal activities can be carried forward in time and associated with instantaneous errors, as proposed in real-time recurrent learning (RTRL)15. While thereby having the advantage of being temporally causal, RTRL still violates locality, as this influence tensor relates all neurons to all synapses in the network, including those that lie far away from each other (Fig. 1). The presence of this tensor also incurs a much higher memory footprint (cubic scaling for RTRL vs. linear scaling for BPTT), which quickly becomes prohibitive for larger-scale applications in ML. Various approximations of RTRL alleviate some of these issues16, but only at the cost of propagation depth. We return to these methods in the Discussion, as our main focus here is AM/BPTT.

Indeed, and contrary to prior belief, we suggest that physical neuronal systems can approximate BPTT very efficiently and with excellent functional performance. More specifically, we propose the overarching principle of generalized latent equilibrium (GLE) to derive a comprehensive set of equations for inference and learning that are local in both time and space (Fig. 1). These equations fully describe a dynamical system running in continuous time, without the need for separate phases, and undergoing only local interactions. Moreover, they describe the dynamics and morphology of structured neurons performing both retrospective integration of past inputs and prospective estimation of future states, as well as the weight dynamics of error-correcting synapses, thus linking to experimental observations of cortical dynamics and anatomy. Due to its manifest locality and reliance on rather conventional analog components, our framework also suggests a blueprint for powerful and efficient neuromorphic implementation.

We thus propose a new solution for the spatio-temporal credit assignment problem in physical neuronal systems, with substantial advantages over previously proposed alternatives. Importantly, our framework does not differentiate between spatial and temporal tasks and can thus be readily used in both domains. As it represents a generalization of latent equilibrium (LE)17, a precursor framework for bio-plausible, but purely spatial computation and learning, it implicitly contains (spatial) BP as a subcase. For a more detailed comparison to LE, see section “Discussion”.

This manuscript is structured as follows: In section “The GLE framework”, we first propose a set of four postulates from which we derive network structure and dynamics. This is strongly inspired by approaches in theoretical physics, where a specific energy function provides a unique reference from which everything else about the system can be derived. We then discuss the link to AM/BPTT in section “GLE dynamics implement a real-time approximation of AM/BPTT”. Additionally, we show how our framework describes physical networks of neurons, with implications for both cortex and hardware (section “Cortical/neuromorphic circuits”). Subsequently, we discuss various applications, from small-scale setups that allow an intuitive understanding of our network dynamics (section “A minimal GLE example” and section “Small GLE networks”), to larger-scale networks capable of solving difficult spatio-temporal classification problems (section “Challenging spatio-temporal classification”) and chaotic time series prediction (section “Chaotic time series prediction”). Finally, we elaborate on the connections and advantages of our framework when compared to other approaches in section “Discussion”.

Results

The GLE framework

At the core of our framework is the realization that biological neurons are capable of performing two fundamental temporal operations. First, as is well-known, neurons perform temporal integration in the form of low-pass filtering. We describe this as a “retrospective” operation and denote it with the operator

where τm represents the membrane time constant and x the synaptic input.

The second temporal operation is much less known but well-established physiologically18,19,20,21,22,23: neurons are capable of performing temporal differentiation, an inverse low-pass filtering that phase-shifts inputs into the future, which we thus name “prospective” and denote with the operator

The time constant τr is associated with the neuronal output rate, which, rather than being simply φ(u) (with u the membrane potential and φ the neuronal activation function), takes on the prospective form \(r=\varphi ({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{u\})\).

In brief, this prospectivity can arise from two distinct mechanisms. On one hand, it follows as a direct consequence of the output nonlinearity in spiking neurons21. In more complex neurons that are capable of bursting, the input slope also directly affects the spiking output24. On the other hand, prospectivity appears when the neuronal membrane (alternatively but equivalently, its leak potential or firing threshold) is negatively coupled to an additional retrospective variable. Such variables include, for example, the inactivation of sodium channels, or slow adaptation (both spike frequency and subthreshold) currents22,23, thus giving neurons access to a wide range of prospective horizons. For more detailed, intuitive explanations of these mechanisms, we refer to the Supplement, section “Biological mechanisms of prospectivity”. For a more technical discussion of prospectivity in neurons with adaptation currents, we refer to section “Prospectivity through adaptation” in the Methods. We also note that in analog neuromorphic hardware, adaptive neurons are readily available25,26,27,28, but a direct implementation of an inverse low-pass filter would evidently constitute an even simpler and more efficient solution.

Importantly, the retrospective and prospective operators \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\) have opposite effects; in particular, for τm = τr, they are exactly inverse, which forms the basis of LE17. In that case, the exact inversion of the low-pass filtering allows the network to react instantaneously to a given input, which can solve the relaxation problem for spatial tasks. However, this exact inversion also precludes the use of neurons for explicit temporal processing in spatio-temporal tasks, which represents the main focus of this work.

We can now define the GLE framework as a set of four postulates, from which the entire network structure and dynamics follow. The postulates use these operators to describe how forward and backward prospectivity work in biological neuronal networks. As we show later, the dynamical equations derived from these postulates approximate the equations derived from AM/BPTT, but without violating causality, with only local dependencies and without the need for learning phases.

Postulate 1

The canonical variables describing neuronal network dynamics are \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}(t)\}\) and \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}(t)\}\), where each neuron is denoted with the subscript i ∈ {1,…,n}.

This determines the relevant dynamical variables for the postulates below. They represent, respectively, the prospective voltages with respect to the membrane and rate time constants. Importantly, each neuron i can in principle have its own time constants \({\tau }_{i}^{x}\), and the two are independent, so in general \({\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}}\,\ne \,{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}\). This is in line with the biological mechanisms for retro- and prospectivity, which are also unrelated, as discussed above.

Postulate 2

A neuronal network is fully described by the energy function

where \({e}_{i}(t)={{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}(t)\}-{\sum}_{j}{W}_{ij}\varphi ({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{j}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{j}(t)\})-{b}_{i}\) is the mismatch error of neuron i. Wij and bi respectively denote the components of the weight matrix and bias vector, φ the output nonlinearity and β a scaling factor for the cost. The cost function C(t) is usually defined as a function of the rate and hence of \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}\}\) of some subset of output neurons.

This approach is inspired by physics and follows a time-honored tradition in ML, dating back to Boltzmann machines29 and Hopfield networks30 as well as computational neuroscience models, such as, e.g., Equilibrium Propagation31 and predictive coding frameworks32. The core idea of these approaches is to define a specific energy function that provides a unique reference from which everything else follows. In physics, this is the Hamiltonian, from which the dynamics of the system can be derived; in our case, it is a measure of the “internal tension” of the network, from which we derive the dynamics of the network and its parameters. Under the weak assumption that the cost function can be factorized, this energy is simply a sum over neuron-local energies \({E}_{i}(t)=\frac{1}{2}{e}_{i}^{2}(t)+\beta {C}_{i}(t)\). Each of these energies represent a difference between a neuron’s own prospective voltage, i.e., what membrane voltage the neuron predicts for its near future (\({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}(t)\}\)), and what its functional afferents (and bias) expect it to be (\({\sum}_{j}{W}_{ij}\varphi ({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{j}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{j}(t)\})+{b}_{i}\)), with the potential addition of a teacher nudging term for output neurons that is related to the cost that the network seeks to minimize (βCi(t)).

Postulate 3

Neuron dynamics follow the stationarity principle

As the two rates of change (the partial derivatives) are with respect to prospective variables, with temporal advances determined by τm and τr, they can be intuitively thought of as representing quantities that refer to different points in the future—loosely speaking, at t + τm and t + τr. To compare the two rates of change on equal footing, they need to be pulled back into the present by their respective inverse operators \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{-}\). It is the equilibrium of this mathematical object, otherwise not immediately apparent (hence: “latent”) from observing the network dynamics themselves (see below), that gives our framework its name. It is also easy to check that for the special case of \({\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}}={\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}\quad \forall i\), GLE reduces to LE17—hence the ‘generalized’ nomenclature.

Postulate 4

Parameter dynamics follow gradient descent (GD) on the energy

with individual learning rates ηθ.

Parameters include θ = {W, b, τm, τr}, with boldface denoting matrices, vectors, and vector-valued functions. These parameter dynamics are the equivalent of plasticity, both for synapses (Wij) and for neurons (\({b}_{i},{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{m}}}},{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}\)). The intuition behind this set of postulates is illustrated in Fig. 2. Without an external teacher, the network is unconstrained and simply follows the dynamics dictated by the input; as there are no errors, both cost C and energy E are zero. As an external teacher appears, errors manifest and the energy landscape becomes positive; its absolute height is scaled by the coupling parameter β. While neuron dynamics \(\dot{u}\) trace trajectories across this landscape, plasticity \(\dot{\theta }\) gradually reduces the energy along these trajectories (cf. Fig. 2). Thus, during learning, the energy landscape (more specifically, those parts deemed relevant by the task of the network, lying on the state subspace traced out by the trajectories during training) is gradually lowered, as illustrated by the faded surface. Ultimately, after learning, the energy will ideally be pulled down to zero, thus implicitly also reducing the cost, because it is a positive, additive component of the energy. Beyond this implicit effect, we later show how the network dynamics derived from these postulates also explicitly approximate gradient descent on the cost.

Network dynamics define trajectories (black) in the cost/energy landscape, spanned by external inputs I and neuron outputs r. Parameter updates (red, here: synaptic weights) reduce the cost/energy along these trajectories. a AM records the trajectory between two points in time and calculates the total update ΔW that reduces the integrated cost along this trajectory. b GLE calculates an approximate cost gradient at every point in time, by taking into account past network states (via retrospective coding, \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\)) and estimating future errors from the current state (via prospective coding, \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\)). Learning is thus fully online and can gradually reduce the energy in real-time, with the (real) trajectory slowly dropping away from the (virtual) trajectory of a network that is not learning (dashed line).

The four postulates above fully encapsulate the GLE framework. From here, we can now take a closer look at the network dynamics and see how they enable the sought transport of signals to the right place and at the right time.

Network dynamics

With our postulates at hand, we can now infer dynamical and structural properties of neuronal networks that implement GLE. We first derive the neuronal dynamics by applying the stationarity principle (Postulate 3, Eqn. (4)) to the energy function (Postulate 2, Eqn. (3)):

where \(\varphi^{{\prime}}_{i}\) is a shorthand for the derivative of the activation function evaluated at \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{u}_{i}\}\). For a detailed derivation, we refer to section “Derivation of the network dynamics” in the Methods. This is very similar to conventional leaky integrator dynamics, except for two important components: first, the use of the prospective operator for the neuronal output, which we already connected to the dynamics of biological neurons above, and second, the additional error term. With this, we have two complementary representations for the error term ei. First, as mismatch between the prospective voltage and the basal inputs (cf. Eqn. (3)), describing how errors couple two membranes, and second, as a function of other errors ej, as given by the error propagation equation (cf. Eqn. (6)). Thus, in the GLE framework, a single neuron performs four operations in the following order: (weighted) sum of presynaptic inputs, integration (retrospective), differentiation (prospective), and the output nonlinearity. The timescale associated with retrospectivity is the membrane time constant τm, whereas prospectivity is governed by τr. This means that even if the membrane time constant is fixed, as may be the case for certain neuron classes or models thereof, single neurons can still tune the time window to which they attend by adapting their prospectivity. This temporal attention window can lie in the past (retrospective neurons, τr < τm), in the present (instantaneous neurons, τr = τm, as described by LE), but also in the future (prospective neurons, τr > τm). These neuron classes can, for example, be found in cortex33,34 and hippocampus35,36; for a corresponding modeling study, we refer to ref. 23. The prospective capability becomes essential for error propagation, as we discuss below, while the use of different attention windows allows the learning of complex spatio-temporal patterns, as we show in action in later sections. Note that for τr = 0, we recover classical leaky integrator neurons as a special case of our framework.

Eqn. (6) also suggests a straightforward interpretation of neuronal morphology and its associated functionality. In particular, it suggests that separate neuronal compartments store different variables: a somatic compartment for the voltage ui, and two dendritic compartments for integrating \({\sum}_{j}\,{W}_{ij}\,{r}_{j}\) and ei, respectively. This separation also gives synapses access to these quantities, as we discuss later on. Further below, we also show how this basic picture extends to a microcircuit for learning and adaptation in GLE networks.

The error terms in GLE also naturally include prospective and retrospective operators. As stated in Postulate 2 (Eqn. (3)), the total energy of the system is a sum over neuron-local energies. If we now consider a hierarchical network, these terms can be easily rearranged into the form (see Methods and SI for a detailed derivation)

where ℓ denotes the network layer and \({\varphi }^{{\prime}}\) denotes the derivative of φ evaluated at \({{{{\boldsymbol{{\mathcal{D}}}}}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{\tau}}}^{{{\rm{r}}}}}^{+}\{{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}_{\ell }\}\). In this form, the connection to BP algorithms becomes apparent. For τr = τm, the operators cancel and Eqn. (7) reduces to the classical (spatial) error BP algorithm, as already studied in ref. 17. When τr ≠ τm, however, the error exhibits a switch between the two time constants when compared to the forward neuron dynamics (Eqn. (6)): whereas forward rates are retrospective with τm and prospective with τr, backward errors invert this relationship. In other words, backward errors invert the temporal shifts induced by forward neurons. As we discuss in the following section, it is precisely this inversion that enables the approximation of AM/BPTT.

As for the neuron dynamics, parameter dynamics also follow from the postulates above. For example, synaptic plasticity is obtained by applying the gradient descent principle (Postulate 4, Eqn. (5) with respect to synaptic weights W) to the energy function (Postulate 2, Eqn. (3)):

where \({v}_{i}={\sum}_{j}\,{W}_{ij}\,{r}_{j}\) is the membrane potential of the dendritic compartment that integrates bottom-up synaptic inputs. Such three-factor error-correcting rules have often been discussed in the context of biological DL (see ref. 37 for a review). For a more detailed biological description of our specific type of learning rule, we refer to ref. 38. Notice that parameter learning is neuron-local, and that we are performing GD explicitly on the energy E, and only implicitly on the cost C. This is a quintessential advantage of the energy-based formalism, as the locality of GLE dynamics is a direct consequence of the locality of the postulated energy function. This helps provide the physical and biological plausibility that other methods lack. In the section “Cortical/neuromorphic circuits”, we discuss how GLE dynamics relate to physical neuronal networks and cortical circuits, but first, we show how these dynamics effectively approximate AM/BPTT.

GLE dynamics implement a real-time approximation of AM/BPTT

The learning capabilities of GLE arise from the specific form of the errors encapsulated in the neuron dynamics, which make the similarity to AM/BPTT apparent, as discussed below. For a detailed derivation of the following relationships, we refer to Methods and the SI.

Just like in GLE, learning in AM/BPTT is error-correcting:

where the continuous-time adjoint variables λ in AM are equivalent to the time-discrete errors in BPTT. While typically calculated in reverse time, as for the backpropagated errors in BPTT, for the specific dynamics of cost-decoupled GLE networks (β = 0 ⇒ e = 0 ⇒ E = 0), it is possible to write the adjoint dynamics in forward time as follows:

Here, we use adjoint operators \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\{x(t)\}=\left(1-\tau \frac{\,{{\mbox{d}}}}{{{\mbox{d}}}t}\right)x(t)\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\{x(t)\}=\frac{1}{\tau }\int_{t}^{\infty }x(s)\,{e}^{\frac{t-s}{\tau }}\,\,{{\mbox{d}}}s\) to describe the hierarchical coupling of the adjoint variables. We note that the adjoint dynamics (Eqn. (10)) can also be derived in our GLE framework by simply replacing \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{\mathrm{m}}}}^{-}\) with \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }_{i}^{{\mathrm{m}}}}^{-}\) in Postulate 3.

Note the obvious similarity between Eqns. (10) and (7). The inner term \({{\bf{\varphi}}}^{{\prime}}_{\ell }\circ {{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}}}_{\ell+1}\) is identical and describes backpropagation through space. The outer operators perform the temporal backpropagation, enacting the exact opposite temporal operations compared to the representation neurons (first retrospective with τr then prospective with τm, cf. Eqn. (6)).

The intuition is as follows. Training ANN on sequential data usually requires unrolling the network in time and then backpropagating errors via AM/BPTT, as given by the adjoint equations (Eqn. (7)). However, these adjoint equations effectively operate in reverse time, i.e., are nonlocal in time and thus not applicable for real-time learning in physical neuronal systems. This nonlocality (noncausality) is due to the operator \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\), which effectively calculates an integral over the future. (The operator \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) is unproblematic in this regard.) By replacing \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) by \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\), GLE solves the noncausality problem. This of course happens at the expense of precision, because the extrapolation carried out by \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) cannot look arbitrarily far into the future. Still, \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) maintains much of the computation performed by \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) in Fourier space, as discussed below. The GLE framework further replaces \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) by \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\). This is not an algorithmic necessity, as \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) is fully local in time, but the resulting dynamics map nicely to the retrospective component of biologically observed neuronal membrane dynamics, which are better described as leaky integrators rather than negative differentiators.

How GLE can perform an online approximation of AM/BPTT is best seen in frequency space, where we can analyze how the combined temporal operators affect individual Fourier components (see also Fig. 3). For a single such component—a sine wave input of fixed angular frequency ω—each operator causes a temporal (phase) shift: the retrospective operator \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) causes a shift of the input signal towards later times, while the prospective operator causes an inverse shift towards earlier times. These phase shifts are exactly equal to those generated by the adjoint operators \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\). Therefore, in terms of temporal shift, the GLE errors are perfect replicas of the adjoint variables derived from exact GD; this is the most important part of the temporal backpropagation in AM.

a Effect of the individual and combined GLE operators \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) with shared time constant τ on a single frequency component of an input current I. \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) generates a negative phase shift (towards later times) and sub-unit gain. \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) is its exact inverse and generates a positive phase shift (towards earlier times) and supra-unit gain. b Phase shift and c gain of all four temporal operators in GLE and AM/BPTT across a wide range of the frequency spectrum. Note how the prospective operators \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\) (orange) have the same shift but inverse gain; the same holds for the retrospective operators \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\) (purple). d Phase shift and e gain of the combined operators as they appear in the neuron dynamics. Here, we choose an example forward neuron (blue) with a retrospective attention window (τm = 10τr). Both the associated GLE errors e (blue) and the adjoint variables λ (dotted) are prospective and precisely invert this phase shift, albeit with a different gain.

In terms of gain, GLE and AM/BPTT are inverted. For smaller angular frequencies ωτ ≲1, this approximation is very good and the gradients are only weakly distorted. We will later see that in practice, for hierarchical networks with sufficiently diverse time constants, successful learning does not strictly depend on this formal requirement. What appears more important is that, even for larger ωτ, GLE errors always conserve the sign of the correct adjoints, so the error signal always remains useful; moreover, higher-frequency oscillations in the errors tend to average out over time, as we demonstrate in simulations below.

Cortical/neuromorphic circuits

As shown above, GLE backward (error) dynamics engage the same sequence of operations as those performed by forward (representation) dynamics: first integration \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\), then differentiation \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\). This suggests that backward errors can be transmitted by the same type of neurons as forward signals39,40, which is in line with substantial experimental evidence that demonstrates the encoding of errors in L2/3 PYR neurons41,42,43,44,45,46. Note that correct local error signals are only possible with neurons that are capable of both retrospective (\({{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{\tau }^{-}\)) and prospective (\({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{\tau }^{+}\)) coding—the core element of the GLE framework.

This symmetry between representation and error suggests a simple microcircuit motif that repeats in a ladder-like fashion, with L2/3 PYR error neurons counterposing L5/6 PYR representation neurons (Fig. 4). Information transmitted between the two streams provides these neurons with all the necessary local information to carry out GLE dynamics. In particular, error neurons can elicit the representation of corresponding errors in dendritic compartments of representation neurons, allowing forward synapses to access and correct these errors through local plasticity. Recent evidence for error representation in apical dendrites provides experimental support for this component of the model47.

Representation neurons form the forward pathway (red), error neurons form the backward pathway (blue). Both classes of neurons are pyramidal (PYR), likely located in different layers of the cortex. Lateral connections enable information exchange and gating between the two streams. The combination of retrospective membrane and prospective output dynamics allow these neurons to tune the temporal shift of the transmitted information. Errors are also represented in dendrites, likely located in the apical tuft of signal neurons, enabling local three-factor plasticity to correct the backpropagated errors.

The correct propagation of errors requires two elements that can be implemented by static lateral synapses. First, error neuron input needs to be multiplicatively gated by the derivative of the corresponding representation neuron’s activation function φ. This can either happen through direct lateral interaction, or through divisive (dis)inhibition, potentially carried out by somatostatin (SST) and parvalbumin (PV) interneuron populations48,49,50,51, via synapses that are appropriately positioned at the junction between dendrites and soma. The required signal \(\varphi^{\prime}\) can be generated and transported in different ways depending on the specific form of the activation function. For example, if φ = ReLU, lateral weights can simply be set to Lb = 1. For sigmoidal activation functions, \(\varphi^{\prime}\) can be very well approximated by synapses with short-term plasticity (e.g., ref. 52, Eqn. 2.80). The second requirement regards the communication of the error back to the error dendrites of the representation neurons; this is easily achieved by setting Lf = 1.

Ideally, synapses responsible for error transport in the feedback pathway need to mirror forward synapses: \({{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}_{\ell }={{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}}\) (cf. Eqn. (7)). This issue is known as the weight transport problem and has been already addressed extensively in literature. While it can, to some extent, be mitigated by feedback alignment (FA)53, improved solutions to the weight transport problem that are both online and local have also been recently proposed54,55,56,57,58. We return to the issue of weight symmetrization in section “Scaling, noise and symmetry”.

We now proceed to demonstrate several applications of the GLE framework. First, we illustrate its operation in small-scale examples, to provide an intuition of how GLE networks can learn to solve non-trivial temporal tasks. Later on, we discuss more difficult problems that usually require the use of sophisticated DL methods and compare the performance of GLE with the most common approaches used for these problems in ML.

A minimal GLE example

As a first application, we study learning in a minimal teacher-student setup. The network consists of a forward chain of two neurons (depicted in red in Fig. 5a) provided with a periodic step function input. The task of the student network is to learn to mimic the output of a teacher network with identical architecture but different parameters, namely, different weights and membrane time constants. Prospective time constants τr are not learned and set to zero for both student and teacher, such that the neurons are simple leaky integrators. The target membrane time constants τm are chosen to be on the scale of the dominant inverse frequency of the input signal, such that they cause a significant temporal shift without completely suppressing the signal. Due to these slow transient membrane dynamics, the task is not solvable using instantaneous backpropagation, but requires true temporal credit assignment instead.

a Network setup. A chain of two retrospective representation neurons (red) learns to mimic the output of a teacher network (identical architecture, different parameters). In GLE, this chain is mirrored by a chain of corresponding error neurons (blue), following the microcircuit template in Fig. 4. We compare the effects of three learning algorithms: GLE (green), BP with instantaneous errors (purple) and BPTT (point markers denote the discrete nature of the algorithm; pink, brown and orange denote different truncation windows (TW)). b Output of representation neurons (ri, red) and error neurons (ei, blue) for GLE and instantaneous BP (BP). Left: before learning (i.e., both weights and membrane time constants are far from optimal). Right: after learning. c Evolution of weights, time constants and overall loss. Fluctuations at the scale of 10−10 are due to limits in the numerical precision of the simulation.

We compare three different solutions to this problem: (1) a GLE network with time-continuous dynamics, including synaptic and neuronal plasticity; (2) standard error BP using instantaneous error signals \({e}_{i}=\varphi^{{\prime}}_{i}{w}_{i}{e}_{i+1}\); (3) truncated BPTT through the discretized neuron dynamics using PyTorch’s autograd functionality for different truncation windows.

We first note that the GLE network learns the task successfully and quickly, in contrast to instantaneous BP (Fig. 5c). To understand why, it is instructive to compare its errors to the instantaneous ones (ei panels in Fig. 5b). The instantaneous errors (BP, dashed lines) are always in sync with the output error, but their shape and timing become increasingly desynchronized from the neuronal inputs as they propagate toward the beginning of the chain, because they do not take into account the lag induced by the representation neurons. Thus, the correct temporal coupling between errors and presynaptic rates required by plasticity (cf. Eqn. (8), see also Eqns. (21), (22), (23), (24) in Methods) is corrupted, and learning is impaired. Note that instantaneous errors are already a strong assumption and themselves require a form of prospectivity17; without any prospectivity, learning performance would be even more drastically compromised. In contrast, the GLE errors gradually shift forward in time, matching the phase and shape of the respective neuronal inputs, and thus allowing the stable learning of all network parameters, weights and time constants alike.

Here, we can also see an advantage of GLE over the classical BPTT solution (Fig. 5c). Despite only offering an approximation of the exact gradient calculated by BPTT, it allows learning to operate continuously, fully online. As discussed above, BPTT needs to record a certain period of activity before being able to calculate parameter updates. If this truncation window is too short, it fails to capture longer transients in the input and learning stalls or diverges (brown and pink, respectively). Only with a sufficiently long truncation window does BPTT converge to the correct solution (orange), but at the cost of potentially exploding gradients and/or slower convergence due to the resulting requirement of reduced learning rates. For a demonstration of the noise robustness of this setup, we refer to section “Small GLE networks” in the Supplement.

Small GLE networks

To better visualize how errors are computed and transmitted in more complex GLE networks, we now consider a teacher-student setup with two hidden layers, each with one instantaneous and one retrospective neuron (Fig. 6a). Through this combination of fast and slow pathways between network input and output, such a small setup can already perform quite complex transformations on the input signal (Fig. 6b). From the perspective of learning an input-output mapping, this can be stated as the output neuron having access to multiple time scales of the input signal, despite the input being provided to the network as a constant stream in real time. This is essential for solving the complex classification problems that we describe later.

a Network setup. A network with one output neuron and two hidden layers (red) learns to mimic the output of a teacher network (identical architecture, different input weights to the first hidden layer). Each hidden layer contains one instantaneous (τm = τr = 1) and one retrospective (τm = 1, τr = 0.1) neuron. In GLE, the corresponding error pathway (blue) follows the microcircuit template in Fig. 4. The input is defined by a superposition of three angular frequency components ω ∈ {0.49, 1.07, 1.98}. Here, we compare error propagation, synaptic plasticity and ultimately the convergence of learning under GLE and AM. b Input and output rates (r, red), along with bottom layer errors (e, light blue) and adjoints (λ, dark blue) before and during the late stages of learning. A running average over e is shown in orange. c Phase shifts (compared to the output error e3) and d amplitudes of bottom layer errors and adjoints across a wide range of their angular frequency spectrum before and during learning. The moments “before” and “during” learning are marked by vertical dashed lines in (e). Top: \({e}_{1}^{\,{\mbox{i}}\,}\) and \({\lambda }_{1}^{\,{\mbox{i}}\,}\) for the instantaneous neuron. Bottom: \({e}_{1}^{\,{\mbox{r}}\,}\) and \({\lambda }_{1}^{\,{\mbox{r}}\,}\) for the retrospective neuron. Note that due to the nonlinearity of neuronal outputs, the network output has a much broader distribution of frequency components compared to the input (with its three components highlighted by the red crosses  ). Error amplitudes are shown at two different moments during learning. e Evolution of the bottom weights (\({w}_{0}^{\,{\mbox{i}}},{w}_{0}^{{\mbox{r}}\,}\)) and f of the loss during learning. The vertical dashed lines mark the snapshots at which adjoint and error spectra are plotted above.

). Error amplitudes are shown at two different moments during learning. e Evolution of the bottom weights (\({w}_{0}^{\,{\mbox{i}}},{w}_{0}^{{\mbox{r}}\,}\)) and f of the loss during learning. The vertical dashed lines mark the snapshots at which adjoint and error spectra are plotted above.

To isolate the effect of error backpropagation into deeper layers, we keep all but the bottom weights fixed and identical between teacher and student. The goal of the student network is to mimic the output of the teacher network by adapting its own bottommost forward weights. We then compare error dynamics and learning in the GLE network with exact gradient descent on the cost as computed by AM/BPTT.

While both methods converge to the correct target (Fig. 6b, e), they don’t necessarily do so at the same pace, since AM/BPTT cannot perform online updates, as also discussed above. Also, GLE error propagation is only identical to the coupling of adjoint variables (AM/BPTT) for instantaneous neurons with τm = τr (\({e}_{1}^{\,{\mbox{i}}}={\lambda }_{1}^{{\mbox{i}}\,}\)). In general, this is not the case (\({e}_{1}^{\,{\mbox{r}}}\ne {\lambda }_{1}^{{\mbox{r}}\,}\)), as GLE errors tend to overemphasize higher-frequency components in the signal (cf. also section “GLE dynamics implement a real-time approximation of AM/BPTT” and Fig. 6d). However, this only occurs for slow, retrospective neurons, which only need to learn the slow components of the output signal. For sufficiently small learning rates, plasticity in their afferent synapses effectively integrates over these oscillations and lets them adapt to the relevant low-frequency components. Indeed, the close correspondence to AM/BPTT is reflected in the average GLE errors, which closely track the corresponding adjoints. While it was not necessary to make use of such additional components in our simulations, high-amplitude high-frequency oscillations in the error signals could be mitigated by several simple mechanisms, including saturating activation functions for the error neurons, input averaging in the error dendrites or synaptic filtering of the plasticity signal.

Following the analysis in the previous section, our simulations now demonstrate how GLE errors encode the necessary information for effective learning. Most importantly, GLE errors and adjoint variables (AM/BPTT) have near-identical timing, as shown by the alignment of their phase shifts across the signal frequency spectrum (Fig. 6c). Moreover, for the errors of the retrospective neurons, these phase shifts are positive with respect to the output error, thus demonstrating the prospectivity required for the correct temporal alignment of inputs and errors. The amplitudes of e and λ also show distinct peaks at the same angular frequencies, corresponding to the three components of the input signal that need to be mapped to the output (Fig. 6d). These signals can thus guide plasticity in the correct direction, gradually learning first the slow and then the fast components of the input-output mapping. This is also evinced by Fig. 6e, where the input weights of the retrospective neurons \({w}_{0}^{\,{\mbox{r}}\,}\) are the first to converge. The ensuing reduction of the slow error components provides the input weights of the instantaneous neurons \({w}_{0}^{\,{\mbox{i}}\,}\) with cleaner access to the fast error components—the only ones that they can actually learn—which allows them to converge as well.

Challenging spatio-temporal classification

We now demonstrate the performance of GLE in larger hierarchical networks, applied to difficult spatio-temporal learning tasks, and compare it to other solutions from contemporary ML. An essential ingredient for enabling complex temporal processing capabilities in GLE networks is the presence of neurons with diverse time constants τm and τr (Fig. 7). Each of these neurons can be intuitively viewed as implementing a specific temporal attention window, usually lying in the past, proportionally to τm − τr. More specifically, for a given angular frequency component of the input ω, this window is centered around a phase shift of \(\arctan (\omega {\tau }^{{{\rm{r}}}})-\arctan (\omega {\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}})\approx \omega ({\tau }^{{{\rm{r}}}}-{\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}})\) for ωτ ≲ 1 (cf. Methods). By connecting to multiple presynaptic partners in the previous layer, a neuron thus carries out a form of temporal convolution, similarly to temporal convolutional networks (TCNs)59. Importantly, however, TCNs rely on some additional mechanism that allows for the mapping of temporal signals to spatial representations, for example, by using buffers or delays. In other words, TCNs do not process their input online, but require it to be rolled out in space and then act like a conventional convolutional network, without any temporal dynamics. Furthermore, network depth is an essential prerequisite for solving the tasks discussed below. Deeper networks also allow longer chains of such neurons to be formed, thus providing the output with a diverse set of complex transforms on different time intervals distributed across the past values of the input signal. GLE effectively enables deep networks to learn a useful set of such transforms.

In the simplest case, a single input signal I(t) is fed into a GLE network and all neurons in the bottom layer have access to the same information stream. However, the output of each neuron generates a temporal shift, depending on its time constants τm and τr (as highlighted by the neuron colors). Different chains of such neurons thus provide neurons in higher levels of the hierarchy with a set of attention windows across the past input activity. Synaptic and neuronal adaptation shape the nature of these temporal receptive fields (TRFs). For multidimensional input, neuron populations (gray) encode the additional spatial dimension and neuronal receptive fields become spatio-temporal (STRFs).

MNIST-1D

We first consider the MNIST-1D60 benchmark for temporal sequence classification. Other than the name itself and the number of classes, MNIST-1D bears little resemblance to its classical namesake. Here, each sample is a one-dimensional array of floating-point values, which can be streamed as a temporal sequence into the network (see Fig. 8a for examples from each class). This deceptively simple setup entails two difficult challenges. First, only a quarter of each sample contains meaningful information; this chunk is positioned randomly within the sample, every time at a different position. Second, independent noise is added on top of every sample at multiple frequencies, which makes it difficult to remove by simple filtering. To allow a direct comparison between the different algorithms, we use no preprocessing in our simulations.

Averages and standard deviations measured over ten seeds. Top row: samples from the a MNIST-1D, b GSC—including raw and preprocessed input—and c CIFAR-10 datasets. d Performance of various architectures on MNIST-1D. Here, we used a higher temporal resolution for the input than in the original reference60. e Performance of various architectures on GSC. f Performance of a (G)LE LagNet architecture on MNIST-1D. For reference, we also show the original results from ref. 60 denoted with the index 0. g Performance of a (G)LE convolutional network on CIFAR-10 (taken from ref. 17) and comparison with BP.

We first note that a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) fails to appropriately learn to classify this dataset, reaching a validation accuracy of only around 60%. This is despite the perceptron having access to the entire sequence from the sample at once, unrolled from time into space. This highlights the difficulty of the MNIST-1D task. More sophisticated ML architectures yield much better results, with TCNs59 and gated recurrent units (GRUs)61 achieving averages of over 90%. Notably, both of these models need to be trained offline, that is, they need to process the entire sequence before updating their parameters, with TCNs in particular requiring a mapping of temporal signals to spatial representations beforehand, and GRUs requiring offline BPTT training with direct access to the full history of the network.

In contrast, GLE networks are trained online, with a single neuron streaming the input sequence to the network and, and the network updating its parameters in real time. The network consists of six hidden layers with a mixture of instantaneous and retrospective neurons in each layer, and a final output layer of ten instantaneous neurons. We use either 53 or 90 neurons per layer, leading to a total of 15 thousand (as the MLP) or 42 thousand parameters, respectively (see Fig. 9b).

a The GLE network used to produce the results in Fig. 8e, where multiple input channels project to successive hidden layers with different time constants. All other networks can be viewed as using a subset of this architecture. b The GLE network trained on the MNIST-1D dataset uses a single (scalar) input channel. This architecture was used to produce the results in Figs. 8d, 10a−c. c “LagNet” architecture used to produce the results in Fig. 10f. It also receives a single input channel, but the weights of the four bottom layers are fixed to identity matrices. This induces ten parallel channels that process the input with different time constants. The MLP on top of this LagNet uses instantaneous neurons and is trained with GLE (which, in the case of equal time constants τm = τr reduces to LE as described in ref. 17). d The GLE network used to tackle spatial problems as per Fig. 10g. All neurons are instantaneous, and the network is equivalent to a LE network.

When faced with short informative signals embedded in a sea of noise, for which the target is always on, even in the absence of meaningful information, the online learning advantage of GLE networks represents an additional challenge to learning. Since only a fraction of each input actually contains a meaningful signal, GLE networks must be capable of remembering these informative combinations of inputs and targets throughout the uninformative portions of their training. However, because they learn continuously, they also do so during uninformative times, which ultimately slows down learning. In contrast, conventional ML models only receive target errors at the end of the sequence or train a readout layer on the unrolled activations of the penultimate layer. Moreover, GLE networks solve a more complex task than conventional models in that they learn both the temporal convolutions and the ultimate classification task simultaneously. This manifests as an increase in convergence time, but not in ultimate performance, as GLE maintains an overall good online approximation of the true gradients for updating the network parameters.

Thus, despite facing a significantly more difficult task compared to the methods that have access to the full network activity unrolled in time, GLE achieves highly competitive classification results, with an average validation accuracy of 93.5 ± 0.9% for the larger network and 91.7 ± 0.8% for the smaller network. The ANN baselines achieve an average validation accuracy of 65.5 ± 1.0% for the MLP, 96.7 ± 0.9% for the TCN and 94.0 ± 1.1% for the GRU, respectively. A more detailed comparison of the performance of GLE with the reference methods can be found in Table D.1 of the Supplement.

Google speech commands

To simultaneously validate the spatial and temporal learning capabilities of GLE, we now apply it to the Google Speech Commands (GSC) dataset62. This dataset consists of 105,829 one-second long audio recordings of 35 different speech commands, each spoken by thousands of people. In the v2.12 version of this dataset, the usual task is to classify ten different speech commands in addition to a silence and an unknown class, which comprises all remaining commands. The raw audio signal is transformed into a sequence of 41 Mel-frequency spectrograms (MFSs); this sequence constitutes the temporal dimension of the dataset and is streamed to the network in real-time. Each of these spectrograms has 32 frequency bins, which are presented as 32 separate inputs to the network, thus constituting the spatial dimension of the dataset. Figure 8e compares the performance of GLE to several widely used references: MLP, TCN, GRU (as used for MNIST-1D) and, additionally, short-term memory (LSTM) networks63—all trained with a variant of BP. Similarly to the MNIST-1D dataset, the GLE network is trained online and updates its parameters in real time, while the reference networks can only be trained offline; furthermore, the MLP and TCN networks do not receive the input as a real-time stream, but rather as a full spectro-temporal “image”, by mapping the temporal dimension onto an additional spatial one. Here, the GLE network receives its input through 32 neurons streaming 32 MFS bins to the network. The network consists of three hidden layers with a mixture of instantaneous and retrospective neurons in each layer, and a final output layer of 12 instantaneous neurons (see Fig. 9a). As with MNIST-1D, we see how our GLE networks surpass the MLP baseline and achieve a performance that comes close to the references, with an average test accuracy of 91.44 ± 0.23%. The ANN baselines achieve an average test accuracy of 88.00 ± 0.25% for the MLP, 92.32 ± 0.28% for the TCN, 94.93 ± 0.25% for the GRU, and 94.00 ± 0.19% for the LSTM, respectively. We thus conclude that, while offering clear advantages in terms of biological plausibility and online learning capability, GLE remains competitive in terms of raw task performance. We also note that, in contrast to the reference baselines, GLE achieves these results without additional tricks such as batch or layer normalization, or the inclusion of dropout layers. A more detailed comparison of the performance of GLE with the reference methods can be found in Table D.1 of the Supplement.

GLE for purely spatial problems

The above results explicitly exploit the temporal aspects of GLE and its capabilities as an online approximation of AM/BPTT. However, GLE also contains purely spatial BP as a subcase, and the presented network architecture can lend itself seamlessly to spatial tasks such as image classification. In cases like this, where temporal information is irrelevant, one can simply take the LE limit of GLE by setting τm = τr for all neurons in the network17 (see Fig. 9d). In the following, we demonstrate these capabilities in two different scenarios. Note that GLE learns in a time-continuous manner in all of these cases as well, with the input being presented in real-time.

First, we return to the MNIST-1D dataset, but adapt the network architecture as follows. The 1D input first enters a non-plastic preprocessing network module consisting of several parallel chains of retrospective neurons. The neurons in each chain are identical, but different across chains: the fastest chain is near-instantaneous with τm → 0, while the slowest chain induces a lag of about 1/4 of the total sample length. The endpoints of these chains constitute the input for a hierarchical network of instantaneous neurons (τm = τr). By differentially lagging the input stream along the input chains, this configuration approximately maps time to space (the output neurons of the chains). This offers the hierarchical network access to a sliding window across the input—hence the acronym “LagNet” for this architecture—and changes the nature of the credit assignment problem from temporal to spatial. While the synaptic weights in the chains are fixed, those in the hierarchical network are trained with GLE, which in this scenario effectively reduces to LE. As shown in Fig. 8f, GLE is capable of training this network to achieve competitive performance with the reference methods discussed above.

As a second application to purely spatial problems, we focus on image classification. Since GLE does not assume any specific connectivity pattern, we can adapt the network topology to specific use cases. In Fig. 8g we demonstrate this by introducing convolutional architectures (LeNet-564) and applying them to the CIFAR1065 dataset. With test errors of (38.0 ± 1.3)%, GLE is again on par with ANNs with identical structure at (39.4 ± 5.6)%. We therefore conclude that, as an extension of LE, GLE naturally maintains its predecessor’s competitive capabilities for online learning of spatial tasks.

Scaling, noise, and symmetry

To evaluate the effect of network size on classification performance, we trained GLE networks of different widths and depths on the MNIST-1D dataset (Fig. 10a−c). Because this dataset requires significant depth for neurons to be able to tune their temporal attention windows, good performance can only be reached for depths of four layers and above. The network width plays only a secondary role, with relatively small performance gains for wider layers. The small decline in performance for larger networks is likely caused by overfitting due to overparametrization.

Averages and standard deviations were measured over ten seeds. All figures depict validation accuracy on the MNIST-1D dataset. a Heatmap of scaling in network width and depth. b Learning with 128 neurons per layer across different depths. c Learning in six-layer networks for different layer widths. d Robustness to spatial noise on τm and τr in a six-layer network for two different layer widths n. Zoomed inlay of epoch 60 to 150. e Robustness to correlated noise on all feedforward rates ri for different noise levels corresponding to the fraction of the input signal amplitude. f Robustness to feedback misalignment \({{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}_{\ell }={{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}}+{{\mathcal{N}}}(0,{\sigma }^{2})\) for different noise levels σ. g Final validation accuracy for different noise levels σ plotted against the corresponding alignment angle \(\angle ({{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}_{\ell },{{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}})\) for the individual layers ℓ ∈ [1, …, L − 1]. Note that FA performs better than the largest noise levels, because the constant randomization of feedback weights prevents FA to take effect.

The robustness of GLE to input level noise has already been implicitly demonstrated, as both MNIST-1D and GSC datasets include either explicitly applied noise or implicit measurement noise and speaker variance. However, whether biological or biologically inspired, analog systems are always subject to additional forms of noise. Spatial noise refers to neuronal variability, caused by either natural biological growth processes or fixed-pattern noise in semiconductor photolitography. Temporal noise refers to variability in all transmitted signals, usually due to quantum or thermal effects, and is typically modeled as a wide-spectrum random process. In the following, we discuss the robustness of GLE with respect to both of these effects during learning of the MNIST-1D task.

First, we established baseline performances for two different network sizes without added noise. To model spatial variability, we then introduced Gaussian noise with increasing levels of variance to the time constants, as all other parameters were optimized through learning Fig. 10d. The effect on training accuracy was insignificant, despite the highest simulated noise level of 0.1 being relatively large compared to the time constants ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 (cf. Table 1 in the Methods). The effects of temporal variability were investigated by adding correlated noise to all feedforward rates ri (Fig. 10e). This type of noise can be much more detrimental than spatial variability, as it gradually and irrevocably destroys information while it passes through the network. We noticed a gradual performance decline for noise levels above 2%, with classification performance dropping by about 10% at a noise level of 10%. Note that, across layers, this sums up to a total noise-to-signal ratio of about 60%, which would represent a major impediment for any network model.

While FA53 is known to have issues with scaling in depth (as we shall also see below), several learning algorithms for active weight alignment have been proposed to explain how biological and bio-inspired systems could solve this problem locally. However, these cannot always guarantee a perfect alignment of forward and backward weights \({{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}_{\ell }={{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}}\). We thus study the performance of GLE networks under varying levels of weight asymmetry. To allow a general assessment independent of particular alignment algorithms, we train GLE networks with backward weights that are noisy versions of the forward weights (Fig. 10f). We resample this noise after each epoch, thus making the problem harder by ensuring that the forward weights cannot mitigate this asymmetry by aligning with the feedback weights during forward learning (as in FA). Fig. 10g shows how the performance of GLE degrades gracefully with increasing weight misalignment. In particular, for alignment angles \(\angle ({{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}_{\ell },{{{\boldsymbol{W}}}}_{\ell+1}^{{{\rm{T}}}}) < \!3{0}^{\circ }\), network performance is barely affected. This lies well within the alignment capabilities of multiple alignment algorithms, as we show in section “Bio-plausibility and the weight transport problem” of the Supplement.

Altogether, these results illustrate the robustness of the GLE framework to realistic types of noise, thereby substantiating its plausibility as a model of biological networks, as well as its applicability to suitable analog neuromorphic devices.

Chaotic time series prediction

As a final application, we now turn to a sequence prediction task, where an autoregressively recurrent GLE network (with its output feeding back into its input) is trained to predict the continuation of a time series based on its previous values. To this end, we use the Mackey-Glass dataset67, a well-known chaotic time series described by a delayed differential equation that exhibits complex dynamics. Figure 11a shows the network setup, which consists of four input neurons, two hidden layers with a mixture of instantaneous and retrospective neurons, and one output neuron. Each Mackey-Glass sequence has a length of 20 Lyapunov times λ, with λ = 197 for our chosen parametrization of the Mackey-Glass equation. The first half of the sequence is used for training, while the second half is used for autoregressive prediction. The resulting requirement of predicting the continuation of the time series across ten Lyapunov times (for which initial inaccuracies are expected to diverge by at least a factor of e10) is what makes this problem so difficult. During training, the network’s target y*(t) is given by the next value in the time series x(t + 1) based on the ground truth x(t). After training, the external input x(t) is removed after the first 10 λ and the network needs to predict the second half of the sequence (which it has never seen during training) using its own output as an input. To provide an intuition for how the network learns, we consider its prediction at an earlier and at a later stage of training. Figure 11b shows the target sequence and the network’s output after 40 epochs of training. The network has already learned a periodic pattern that is superficially similar to parts of the sequence, but the output diverges from the target sequence after only half a Lyapunov time. From here, it takes another 100 epochs (Fig. 11c) for the network’s output to closely match the target sequence over the full period of 10 λ. Figure 11d shows the symmetric mean absolute percentage error (sMAPE), a commonly used metric for evaluating the performance of time series prediction models, over the course of training and averaged over 30 different sequences and initializations. The final average sMAPE of 14.25% for our GLE network is on par with the 14.79% for ESNs and 13.37% for LSTMs reported in ref. 66. If we average the lowest sMAPE over the course of training, we find that our GLE networks can achieve an even lower sMAPE of 9.25%.

a GLE network architecture with 93 hidden neurons per layer. Input neurons are delayed w.r.t. each other by Δ = 6 (same units as λ = 197). b, c Target sequence (dashed black) vs. network output (solid blue) after 40 (b) and 138 (c) epochs of training. d sMAPE loss over the course of training for 30 different sequences compared to ESN and LSTM results as described in ref. 66. The best performance for each sequence is marked as a blue dot.

Discussion

We have presented GLE, a novel framework for spatio-temporal computation and learning in physical neuronal networks. Inspired by well-established approaches in theoretical physics, GLE derives all laws of motion from first principles: a global network energy, a conservation law, and a dissipation law. Unlike more traditional approaches, which aim to minimize a cost defined only on a subset of output neurons, our approach is built around an energy function which connects all relevant variables and parameters of all neurons in the network. This permits a unified view on the studied problem and creates a tight link between the dynamics of computation and learning in the neuronal system. The extensive nature of the energy function (i.e., its additivity over subsystems) also provides an important underpinning for the locality of the derived dynamics.

In combination, these dynamics ultimately yield a local, online, real-time approximation of AM/BPTT—to our knowledge, the first of its kind. Moreover, they suggest a specific implementation in physical neuronal circuits, thus providing a possible template for spatio-temporal credit assignment in the brain, as well as blueprints for dedicated hardware implementations. This shows that, in contrast to conventional wisdom, physical neuronal networks can implement future-facing algorithms for temporal credit assignment. More recently, tentative calls in this direction have indeed been formulated12, to which GLE provides an answer.

In the following, we highlight some interesting links to other models in ML, discuss several biological implications of our model, and suggest avenues for improvement and extension of our framework.

Connection to related approaches

Latent Equilibrium (LE)

As the spiritual successor of LE17, GLE inherits its energy-based approach, as well as the derivation of dynamics from energy conservation and minimization. GLE also builds on the insight from LE that prospective coding can undo the low-pass filtering of neuronal membranes. The core addition of GLE lies in the separation of prospective and retrospective coding, leading to an energy function that depends on two types of canonical variables instead of just one, and to a conservation law that accounts for their respective time scales. The resulting neuron dynamics can thus have complex dependencies on past and (estimated) future states, whereas information processing in LE is always instantaneous. Functionally, this allows neurons to access their own past and future states (through appropriate prospective and retrospective operators), thereby allowing the network to minimize an integrated cost over time, whereas LE only minimizes an instantaneous cost.

Because LE can be seen as a limit case of GLE, the new framework offers a more comprehensive insight into the effectiveness of its predecessor, and also answers some of the questions left open by the older formalism. Indeed, the GLE analysis demonstrates that LE errors are an exact implementation of the adjoint dynamics of the forward system for equal time constants, further confirming the solid grounding of the method, and helping explain its proven effectiveness. Conversely, GLE networks can learn to evolve towards LE via the adaptation of time constants if required by the task to which the framework is applied. While LE also suggests a possible mechanism for learning the coincidence of time scales, GLE provides a more versatile and rigorous learning rule that follows directly from the first principles on which the framework is based. More generally speaking, by having access to local plasticity for all parameters in the network, GLE networks can either select (through synaptic plasticity) or adapt (through neuronal plasticity) neurons and their time constants in order to achieve their target objective.

Thus, GLE not only extends LE to a much more comprehensive class of problems (spatio-temporal instead of purely spatial), but also provides it with a better theoretical grounding, and with increased biological plausibility. Recently68, also proposed an extension of LE by incorporating hard delays in the communication channel between neurons. In order to learn in this setting, they propose to either learn a linear estimate of the future errors (similar to our prospective errors) or to learn an estimate of future errors by a separate network. In contrast to this, GLE implements a biologically plausible mechanism for retrospection, and a self-contained error prediction which we show gives a good approximation to the exact AM solution.

Neuronal least-action (NLA)

Similarly, inspired by physics, but following a different line of thought, the NLA principle69 also uses prospective dynamics as a core component. It uses future discounted membrane potentials \(\tilde{u}={{{\mathcal{I}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{+}\{u\}\) as canonical variables for a Lagrangian L and derives neuronal dynamics as associated Euler-Lagrange equations. A simpler but equivalent formulation places NLA firmly within the family of energy-based models such as LE and GLE, where L is replaced by an equivalent energy function E that sums over neuron-local errors and from which neuronal dynamics can be derived by applying the conservation law \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}_{{\tau }^{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{+}\{\partial E/\partial u\}=0\).

The most important difference to GLE is that NLA cannot perform temporal credit assignment. Indeed, other than imposing a low-pass filter on its inputs, an NLA network effectively reacts instantaneously to external stimuli and can neither carry out nor learn temporal sequence processing. This is an inherent feature of the NLA framework, as the retrospective low-pass filter induced by each neuronal membrane exactly undoes the prospective firing of its afferents.

This property also directly implies that, except for the initial low-pass filter on the input, all neurons in the network need to share a single time constant for both prospective and retrospective dynamics. In contrast, both LE and GLE successively lift this strong entanglement by modifying the energy function and conservation law. LE correlates retro- and prospectivity within single neurons and allows their matching to be learned, thus obviating the need for globally shared time constants, while GLE decouples these two mechanisms, thus enabling temporal processing and learning, as discussed above.

RTRL and its approximations

RTRL70 is a past-facing algorithm that implements online learning by recursively updating a tensor Mijk that takes into account the influence of every synapse wjk on every neuronal output ri in the network. As evident from the dimensionality of this object, this requires storing \({{\mathcal{O}}}({N}^{3})\) floating-point numbers in memory (where N is the number of neurons in the network). Because this is much less efficient than future-facing algorithms, RTRL is rarely used in practice, and the manifest nonlocality of the influence tensor also calls into question its biological plausibility. Nonetheless, several approximations of RTRL have been recently proposed, with the aim of addressing these issues16.

A particularly relevant algorithm of this kind is random feedback online learning (RFLO)71, in which a synaptic eligibility trace is used as a local approximation of the influence tensor, at the cost of ignoring dependencies between distant neurons and synapses. With a reduced memory scaling of \({{\mathcal{O}}}({N}^{2})\), this puts RFLO at a significant advantage over RTRL, while closing the distance to BPTT (with \({{\mathcal{O}}}(NT)\), where T is the length of the learning window). In its goal of reducing the exact, but nonlocal computation of gradients to an approximate, but local solution, RFLO shares the same spirit as GLE. In the following, we highlight several important differences which we consider to give GLE both a conceptual and a practical advantage.

First, the neuron membranes and synaptic eligibilities in RFLO are required to share time constants, in order for the filtering of the past activity to be consistent between the two. In the cortex, this would imply the very particular neurophysiological coincidence of synaptic eligibility trace biochemistry closely matching the leak dynamics of efferent neuronal membranes. In contrast, the symmetry requirements of GLE are between neurons of the same kind (PYR cells), which share their fundamental physiology, and whose time constants can be learned locally within the framework of GLE.

Second, the dimensionality reduction of the influence tensor proposed by RFLO also puts it at a functional disadvantage, because the remaining eligibility matrix only takes into account first-order synaptic interactions between directly connected neurons. This is in contrast to GLE, which can propagate approximate errors throughout the entire network. This flexibility also allows GLE to cover applications over multiple time scales, from purely spatial classification to slow temporal signal processing. Moreover, GLE accomplishes this within a biologically plausible, mechanistic model of error transmission, while admitting a clear interpretation in terms of cortical microcircuits. Finally, GLE’s additional storage requirements only scale linearly with N (one error per neuron at any point in time), which is even more efficient than BPTT.

While both RFLO and GLE are inspired by and dedicated to physical neuronal systems, both biological and artificial, it might still be interesting to also consider their computational complexity for digital simulation, especially given the multitude of digital neuromorphic systems72 and ANN accelerators73 capable of harnessing their algorithmic capabilities. For a single update of their auxiliary learning variables (eligibility traces / errors), both RFLO and GLE incur a computational cost of \({{\mathcal{O}}}({N}^{2})\). Thus, for an input of duration T, all three algorithms—RFLO, GLE, and BPTT (without truncation)—are on par, with a full run having a computational complexity of \({{\mathcal{O}}}({N}^{2}T)\).

State space models (SSMs)

GLE networks are linked to locally recurrent neural networks (LRNNs) (see, e.g., refs. 74). In recent years there has been renewed interest in similar models in the form of linear recurrent units (LRUs)75,76, which combine the fast inference characteristics of LRNNs with the ease of training and stability stemming from the linearity of their recurrence. These architectures are capable of surpassing the performance of Transformers in language tasks involving long sequences of tokens77,78.

More specifically, GLE networks are closely linked to LRUs with diagonal linear layers79 and SSMs80,81, where a linear recurrence only acts locally at the level of each neuron, as realized by the leaky integration underlying the retrospective mechanism. Additionally, the inclusion of prospectivity enables the direct pass-through of input information across layers as in SSMs (see discussion in Methods). GLE could thus enable online training of these models, similarly to how82 demonstrate local learning with RTRL, but with the added benefits discussed above. Since such neuron dynamics are a de-facto standard for neuromorphic architectures72, GLE could thus open an interesting new application area for these systems, especially in light of their competitive energy footprint83,84.

As GLE is strongly motivated by biology, it currently only considers real-valued parameters for all connections, including the self-recurrent ones, in contrast to the complex-valued parameters in LRUs. However, an extension of GLE to complex activities appears straightforward, by directly incorporating complex time constants into prospective and retrospective operators, or, equivalently, by extending them to second order in time. With this modification, GLE would also naturally extend to the domain of complex-valued neural networks (CVNNs)85.

Neurophysiology