Abstract

As wireless technologies advance and new applications emerge, ensuring secure and resilient networks is increasingly critical. Here, we propose a wireless security mechanism based on a meta-encryptor (ME) with low-complexity architecture leveraging the unique capability of information metasurface. ME controls electromagnetic waves in time, space, and frequency domains, and, combined with encryption strategies, enables elastic, complementary multi-dimensional security. Three advanced security dimensions are demonstrated: (1) directional beam secure transmission that confines transmissions to intended receivers; (2) dual channel direct and hybrid modulations that distribute information while complementing resilient cryptography; and (3) wide range frequency-hopping transmission to effectively mitigate eavesdropping. By unifying multiple security functions on a single platform, a V-band prototype attains 100 Mbps while realizes wireless security, allowing flexible and elastic configuration without using conventional baseband mixing and bulky hardware. ME highlights the potential of information metasurface for next-generation secure wireless networks with low complexity and high efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid evolution of wireless communications and the emergence of new applications such as smart homes, autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, and telemedicine, the demand for higher data rates, ultra-low latency, and seamless connectivity is on the rise1. However, this increased reliance on wireless technology also comes with an increased risk of security vulnerabilities2. For example, unauthorized access, interception, or manipulation of smart home and telemedicine devices can cause privacy breaches and even endanger lives. And therefore, as we move towards the research of 6 G3,4, it is crucial to address these security concerns to ensure the safety and privacy of users. The development of secure and resilient wireless networks should be a top priority for researchers and industry professionals alike. Recently, cryptography-based security technologies, quantum key distribution (QKD), physical layer security (PLS), and related approaches have been proposed as promising solutions for enhancing wireless communication security.

The wireless security technologies, which rely on conventional encryption algorithms implemented at the upper layers of the protocol stack, typically demand complex operations and significant computational resources5. Resource-constrained devices, such as those in the Internet of Things (IoT), often cannot handle intricate encryption, leading to performance bottlenecks or the use of weaker, more vulnerable schemes6. Additionally, the security of conventional encryption algorithms depends on the complexity of underlying mathematical problems, and advancing computational power increases the risks to these algorithms7,8. Recently, novel methods such as deep learning and artificial intelligence have been applied to enhance the wireless security through detecting and mitigating threats within wireless signals9. However, these approaches are vulnerable to adversarial attacks and require significant computational resources. QKD offers theoretically unbreakable encryption, but faces many challenges due to limited maturity, high complexity, and substantial cost10. PLS enhances wireless security by leveraging the inherent physical characteristics of wireless channels11,12. For instance, PLS leverages differences between the legitimate channel and potential eavesdropping channels, along with channel randomness and reciprocity, to ensure that the intercepted signals provide minimal or no useful information to the unauthorized parties8. Supported by advancements in hardware, various PLS techniques have been progressively proposed, including artificial noise generation13, directional beamforming14, and channel-based secure key generation15. Frequency hopping, a class of spread-spectrum signaling, is widely explored for wireless security. By pseudo-randomly cycling across a hopset with short dwell times, the frequency hopping spreads energy in the frequency domain, yielding strong low probability of intercept/detection16. When an eavesdropper is limited to a narrowband subset of frequencies, excluding vulnerable tones from the hopset further strengthens the security and link reliability. The frequency hopping is particularly attractive at mmWave and terahertz bands, where abundant spectrum enables large hopsets and high hop agility. Relying solely on a single technology, however, poses challenges such as excessive computational overhead, high system complexity, and significant hardware costs. These challenges are expected to escalate with the growing data volumes and hardware demands of mmWave and terahertz frequencies. Consequently, developing an integrated wireless security architecture that combines multiple encryption technologies, supports flexible configuration and elastic selection, and achieves an optimal balance between security, efficiency, and cost is crucial for future networks.

The advent of information metasurface (IM) presents innovative opportunities to address the challenges of achieving simplified, cost-effective, and efficient wireless security in the communication systems17,18,19. IM enables the programmable manipulation of electromagnetic (EM) waves by incorporating tunable materials20,21,22 or devices23,24,25 in subwavelength artificial atoms, effectively bridging the EM physics and digital information26,27. By dynamically controlling the state of IM, a range of phenomena and functions can be achieved, including beam tracking28, dynamic focusing29,30, imaging31, holography32,33, cloaking34,35, radar application36,37, and harmonics generation and manipulation38,39. In the wireless communication scenarios, IM has been proven to significantly enhance the flexibility and performance of communication systems, including achieving channel customization, expanding signal coverage, improving energy efficiency, and adapting to environments40,41. Crucially, direct modulation of digital information via IM allows for simplified transmitters that deliver stable and versatile communication functions without complex and expensive high-performance hardware42,43,44. This provides a cost-effective solution for wireless communications in the mmWave and terahertz frequency bands45. Despite the growing interest in communication systems by IM, the potential of IM to enhance wireless security through flexible EM environments and digital information control has yet to be fully explored.

Integrated IMs have begun to find applications in enhancing wireless security. By meticulously designing the beamforming coding strategies, IM can manipulate channels to increase the mutual information between the transmitter and intended users while minimizing the information available to eavesdroppers, which can effectively safeguard the transmission confidentiality46,47,48. When combined with space-time coding modulation, IM further enhances the wireless security through techniques such as directional beamforming with direct information modulation49,50, multi-frequency modulation via complex structures51, and polarization-based encryption52,53. Despite such recent progress, most studies have been focused on using IM to implement or enhance single wireless security technology, leaving its full potential under-explored. For example, based on the above discussion, it is foreseeable that frequency hopping implemented natively on IMs designed for ultra-wideband operation can use their ultra-wideband characteristics and high-speed diode-based control elements to realize highly agile hop patterns, without requiring the additional high-agility RF front end. This will further advance the frequency hopping and provide new options for wireless security. It is imperative to develop innovative EM manipulation mechanisms and coding strategies to further enhance the functionality and performance of IM. Such advancements would enable IM to simplify the system complexity while equipping wireless communication with a robust security architecture that can provide multi-dimensional protection, flexible configuration, and elastic selection, achieving an optimal balance between security, cost, and efficiency. These capabilities are particularly attractive in the emerging 6 G and IoT scenarios, where stringent size, weight, and power (SWaP) constraints restrict the use of large phased arrays or heavy cryptographic processors. For example, the secure vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2X) communication requires roadside units to deliver confidential control signals to legitimate vehicles only, while industrial IoT networks demand low-cost ceiling-mounted devices that can distribute confidential commands directionally to authorized sensors. These representative cases highlight the practical demands for metasurface-based wireless security architectures.

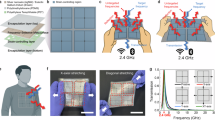

Building upon the concept of IM, we propose a novel architecture termed the meta-encryptor (ME). This architecture aims to enable a simplified wireless secure communication system to support multi-dimensional encryption, flexible configuration, and elastic selection, while avoiding any increase in system complexity. ME is constructed using a 2-bit IM as the core component, complemented by a robust EM manipulation mechanism and an intelligent control system. With its ultra-wideband capability and the flexibility to independently regulate both fundamental and harmonic waves, ME establishes a new security paradigm to integrate multiple advanced wireless security measures into a single programmable platform, including PLS based on directional transmission, elastic cryptographic strategies utilizing the multi-channel configurations, and ultra-wideband frequency-hopping communication. Figure 1 illustrates three primary wireless security functions of the secure wireless communication system driven by ME. As shown in the figure, the proposed security architecture demonstrates the capability to integrate multiple wireless security technologies, enabling the realization of multi-dimensional wireless security. The first-level encryption is called directional secure transmission. Dual-channel beamforming can be attained by flexibly manipulating the corresponding phase coding sequences of the fundamental and harmonic beams, allowing confidential information to be securely transmitted through precisely directed beams. In contrast to the conventional directional PLS, ME prevents leakage that would otherwise arise from suboptimal beamforming on a single channel. The second-level encryption is realized through dual-channel and hybrid modulation secure transmission. As shown in Fig. 1, an advanced coding strategy for the ME array is used to distribute the information across multiple channels. This design enables the elastic selection of various cryptography strategies and supports both linear and nonlinear transmissions using identical or distinct modulation schemes. As a result, an eavesdropper cannot extract accurate information from any single channel. Within this workflow, ME can integrate with conventional cryptographic algorithms, providing stronger and more flexible protection as needed. The most significant level of encryption is frequency-hopping secure transmission. This coding strategy empowers ME to control the EM waves over an ultra-wideband spectrum, enabling robust frequency-hopping communication that effectively thwarts eavesdroppers by unpredictable frequency changes, and all of them do not significantly increase the hardware overhead. Then, we develop an experiment system prototype operating in V-band that supports secure directional transmission within the range of ±45o. This prototype facilitates the QPSK modulation on the fundamental-wave channel (Channel 1) and QPSK or M-ary FSK modulation on the harmonic-wave channel (Channel 2), in which both channels maintain operations over 20 GHz. Remarkably, the single aperture ME array achieves a 100Mbps data rate while providing wireless security. Taken together, the ME provides an IM-native multi-dimensional security architecture with the elastic complementarity. Security primitives are distributed across orthogonal EM degrees of freedom, including spatial/angle, spectral/frequency, temporal, and channel partitioning, while remaining compatible with the conventional cryptography. ME enables elastic selection of one or more dimensions to match the application needs and hardware constraints, and the complementary among dimensions maintains the confidentiality even if one dimension is partially compromised. This integration shifts the objective from pursuing a single “strongest” defense to a coordinated and low-overhead solution that pragmatically balances the security, complexity, and cost.

Confidential information is distributed across two distinct channels: the fundamental channel (Channel 1) and the harmonic channel (Channel 2), based on the elastic encryption strategy specified by the user. The beam deflecting direction is determined according to the intend receiver’s location. A space-time coding is then generated using the ME’s EM manipulation mechanism and coding strategy, and this coding is loaded onto the ME array via the controller to modulate the incident carrier. Finally, the receiver captures the reflected wave and demodulates the transmitted data. The system demonstrates three key wireless security features: 1 Directional Secure Transmission: information directed to the receiver in the specified direction is inaccessible to Eavesdropper I positioned in other directions; (2) Dual-Channel and Hybrid Modulation Secure Transmission: accurate demodulation requires simultaneous reception of data from both channels and knowledge of the predefined encryption strategy, which prevents Eavesdropper II from demodulating the data; and (3) Frequency-Hopping Secure Transmission: the system employs a dynamic frequency-hopping strategy in an ultra-wideband range, ensuring that the eavesdroppers cannot demodulate the data without the knowledge of the current carrier frequency.

Results

Design of meta-atom and ME array

We design a 2-bit IM array operating in the V-band. Figure 2a shows the structure of the metasurface element (meta-atom), which consists of a sandwich-like structure, with a copper reflection coating on the bottom layer, a dielectric spacer in the mid-layer, and two stepped copper patches and a rectangular copper patch on the top structure. The element also contains two positive-intrinsic-negative (PIN) diodes that act as RF switches to dynamically adjust the input impedance of the ME array element. As a result, the element can exhibit four distinct reflection states corresponding to the phase changes of 0,\(\pi /2\),\(\pi\), and \(3\pi /2\) for the perpendicularly incident EM waves. In addition, the copper patches also serve as a component of the biasing circuits for driving the PIN diodes, with the rectangular patch linking to the back plane through a via and serving as a ground for the biasing voltage.

a Perspective view of the meta-atom and the equivalent circuit of the PIN diode. b Top view of the meta-atom. The optimized element sizes are p = 2400 μm, w1 = 380 μm, w2 = 260 μm, w3 = 860 μm, w4 = 100 μm, s1 = 240 μm, s2 = 360 μm, h1 = 1000 μm, a = 300 μm, b = 200 μm, t1 = 35 μm, t2 = 508 μm, and t3 = 100 μm. c Side view of the meta-atom. d Amplitude and phase of the reflection spectrum for different diode switching states.

In this design, the dielectric substrate is selected as Rogers RT/duroid 5880, with a dielectric constant of 2.2 and a low loss tangent of 0.0009. The PIN diodes are Macom’s MA4AGBLP912 AlGaAs Beamlead diodes. For the resistor-inductor-capacitor (RLC) series model shown in Fig. 2a, the model parameters at the target frequency are \(R={{{\rm{8}}}}\,\Omega \,\), \(C={{{\rm{27fF}}}}\), and \(L={{{\rm{30pH}}}}\), respectively. The meta-atom structure and the corresponding geometric parameters were then optimized through the full-wave simulation, as shown in Fig. 2b, c. To comprehensively analyze the reflection spectra of the ME element, we conduct full-wave simulations using CST Microwave Studio 2022 through separately switching the “On/Off” state of the two PIN diodes in each meta-atom. The reflection phase results under different diode configurations are depicted in Fig. 2d. Specifically, in the “Off-On” state, the reflection phase at 54.9 GHz is denoted as \(\theta\). This phase shifts to \(\theta+\pi /2\) in the “On-On” state, \(\theta+\pi\) in the “Off-Off” state, and \(\theta+3\pi /2\) in the “On-Off” state. The reflection loss across all four states is found to be below 3.7 dB, meeting the design criteria for a 2-bit metasurface array. Subsequently, we design and fabricate a ME array comprising 12 × 8 elements for experimental validation (see “Methods” for details). In this array, all PIN diodes within each column are interconnected to share the same control signal. It is important to note that, due to limitations in processing and manufacturing technologies, the fabricated samples achieve optimal performance at 52.8 GHz.

Wideband dual-channel direct modulations based on ME

In IM-based direct wireless communications, the metasurface array can dynamically modify the characteristics of EM waves in real time according to the transmitted information. Controlled by a square-wave-like signal characterized by period \({T}_{0}\), duty cycle \(D\), and time delay \({t}_{0}\) from the ME controller, a monochromatic plane wave \({E}_{i}(f)\) with frequency \({f}_{c}\) incident on the ME array results in a reflected wave \({E}_{r}(f)\), which can be expressed as45:

in which \({c}_{n}=hDSa(n\pi D)\), \({\omega }_{0}=2\pi {f}_{0}\), and \({f}_{0}=1/{T}_{0}\). The parameter \(h\) depends on the two reflection patterns and can be written by \(h={\Gamma }_{a}-{\Gamma }_{b}=|h|{e}\,^{j{\varphi }_{f}}\), where the reflection coefficients corresponding to the high and low levels of the square-wave-like control signal are \({\Gamma }_{a}={A}_{a}{e}^{j{\varphi }_{a}}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}={A}_{b}{e}^{j{\varphi }_{b}}\), respectively (see Supplementary Information Note 1 for details).

The frequency domain reflection coefficient of the fundamental wave is given by \({\Gamma }_{f}=D{\Gamma }_{a}+(1-D){\Gamma }_{b}\). Based on the characteristics of the ME array, \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\) are selected to have equal amplitude coefficients and orthogonal phase coefficients. By appropriately choosing \(D\), the phase of the reflected fundamental wave can be manipulated across the entire range from 0 to \(2\pi\). For harmonic manipulation, considering the impact of the state-contrast phase \({\varphi }_{f}\) introduced by the periodic switching of the reflection coefficient, and based on Eq. (1), the amplitude and phase coefficients of the \(n\) th-order (\(n\ne 0\)) harmonic can be expressed as follows:

Here, \({\varphi }_{0}\) denotes the initial phase, incorporating the intrinsic modulation phase terms \(-\pi nD\) and \(\angle Sa(n\pi D)\), plus an arbitrary fixed reference phase \({\varphi }_{ref}\). As observed, once \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\) are determined, both \({\varphi }_{0}\) and \({\varphi }_{f}\) will be consequently determined. Thus, the final phase of the reflected harmonic depends on \({t}_{0}\), and adjusting \({t}_{0}\) does not alter the phase of fundamental wave. Moreover, modulating the duty cycle \(D\) will change the distribution of EM energy between the fundamental wave and the harmonics. The reflected harmonics can achieve the desired phase by varying \({t}_{0}\). Therefore, by first selecting appropriate values for \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\), and subsequently choosing an appropriate \({t}_{0}\), independent regulation of the reflected fundamental and the harmonic waves can be achieved (see Supplementary Information Note 2 for details).

Furthermore, we develop a specific operation mechanism for ME applications. By switching the PIN diode states of the 2-bit ME array, and selecting different combinations of two orthogonal reflection coefficients \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\), four fundamental signals with a phase difference of \(\pi /2\) are generated. With \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\) fixed, the time delay \({t}_{0}\) cycles through \(0\), \(-{T}_{0}/4\), \(-{T}_{0}/2\), and \(-3{T}_{0}/4\) as prescribed by Eq. (2), thereby producing a harmonic phase gradient of \(\pi /2\). Additionally, to ensure that the modulated EM energy is primarily distributed between the fundamental wave and the 1st-order harmonic, the duty cycle \(D\) of the ME element switching between \({\Gamma }_{a}\) and \({\Gamma }_{b}\) is consistently maintained at 0.5 (see Supplementary Information Note 3 for details). Under this configuration, the usable energy accounts for 70.265%, substantially reducing the power wasted in unwanted higher-order harmonics.

Then, by applying the generalized Snell’s law54, we can further design specific phase distributions for the fundamental and the harmonic waves, thereby enabling independent beamforming for them. According to Eq. (1), under the current control mechanism, the equivalent reflection coefficient for the fundamental wave is calculated as \(\cos (({\varphi }_{a}-{\varphi }_{b})/2){e}^{i({\varphi }_{a}+{\varphi }_{b})/2}\), with an equivalent phase coefficient of \(({\varphi }_{a}+{\varphi }_{b})/2\). This enhances the robustness of the fundamental phase and mitigates phase response deterioration resulting from ME processing, mounting, and frequency offsets. Regarding the harmonics, as per Eq. (2), the deterioration of the meta-atom’s reflection coefficient affects only the amplitude distribution and introduces additional phase shift, without altering the phase gradient of the reflected harmonics as if the time delay is fixed for the modulation signals. Consequently, our ME control mechanism demonstrates significant potential, establishing a robust foundation for the seamless integration of multi-dimensional wireless security technologies, including multi-channel distributed resilient secure transmission, directional secure transmission, and ultra-wideband frequency hopping.

Next, dual-channel information transmission can be achieved by employing the ME array as a hardware platform for direct information modulating. In this process, whether the fundamental or the harmonic wave channel, the information is encoded in the reflection coefficient. For simplicity, the equivalent reflection coefficient of the fundamental or harmonic wave generated by the ME array is denoted as \(\gamma (t)\), which can be expressed as follows:

Here, \({\gamma }_{m}(t)\) denotes the equivalent reflection coefficient resulting from mapping the transmission signal of the fundamental or harmonic channel. The function \(g(t)\) represents the basic pulse shaping function and \(T^{\prime}=n{T}_{0}\) is the duration of an information symbol. \(M\) is a symbol set with cardinality \(|M|\), and each information symbol \({\gamma }_{m}(t)\) contains the information bits of \({\log }_{2}|M|\). For amplitude and phase modulations, a single information symbol is expressed as \({\gamma }_{m}(t)={A}_{m}{e}^{j{\varphi }_{m}},0\le t\le T^{\prime}\), where \({A}_{m}\) and \({\varphi }_{m}\) denote the distinct equivalent reflection amplitude and phase coefficients of the ME-reflected fundamental or harmonic waves, corresponding to the amplitude and phase of the constellation points. Thus, a variety of wireless communication modulation schemes, including QPSK and 16QAM, can be implemented (see Supplementary Information Note 4 for details). Building on the ME’s capability to tune harmonic frequency, we implement M-ary FSK by selecting constellation point from the set \({\gamma }_{m}(t)={e}^{j2\pi {f}_{m}t},{f}_{m}\in M={f}_{1},{f}_{2},\cdots,{f}_{m}\). The frequencies \({f}_{1},{f}_{2},\cdots,{f}_{m}\) serve as the symbol alphabet. By adjusting the time-coding frequency applied to the ME array, the FSK order can be chosen on demand, enabling arbitrary-order FSK (see Supplementary Information Note 5 for details). Hence, the presented EM manipulation mechanism establishes a mapping between the information data and the ME’s equivalent reflection coefficients through designing an appropriate space-time coding sequence for different harmonic orders. This enables the direct modulation of EM wave by the ME, thereby constructing a multi-dimensional secure wireless communication architecture based on ME.

ME-based multi-dimensional wireless security architecture

Construction of the ME platform

The proposed ME platform integrates three complementary mechanisms of wireless security. Firstly, directional secure transmission is operated in the spatial domain by steering the beam toward the legitimate receiver while suppressing signal leakage in other directions. Secondly, dual-channel and hybrid modulation secure transmissions are carried out in the waveform domain by distributing the information across both fundamental and harmonic channels and integrating with the cryptographic primitives, such that the interception of a single channel cannot reveal the confidential data. At the same time, the heterogeneous modulations make the eavesdropper’s detection and synchronization be complicated. Thirdly, frequency-hopping secure transmission is performed in the spectral domain by dynamically varying the carrier frequency, which further prevents the unauthorized interception. As a unified framework, such three mechanisms reinforce one another across spatial, waveform, and spectral domains, thus enabling multi-dimensional and robust wireless security in a single metasurface-based platform. Building on the ME manipulation mechanism outlined in the previous section, we designed an FPGA-based controller, which was integrated with the array via the driving circuit to form a complete ME. The use of an FPGA-based controller not only enables flexible space-time coding but also points to the feasibility of compact and low-power integration, which is crucial for SWaP-constrained platforms such as roadside V2X units and industrial IoT gateways. Subsequently, we developed a platform for a ME-based multi-dimensional security wireless communication system, as depicted in Fig. 3a. We demonstrated three wireless security schemes, with the process emphasized by the red key pattern in the figure representing the critical step in implementing wireless security. The corresponding encryption concepts are further illustrated in Fig. 3b–d. On the transmitter side (Alice), the host converts the information to be transmitted, such as images, videos, and other file types, into a bit stream. As discussed above, the ME is capable of simultaneously manipulating both the fundamental and harmonic waves, which are utilized for information modulation across two designated data transmission channels: Channel 1 (Fundamental) and Channel 2 (Harmonic). For the same set of transmitted information, its bit stream is distributed and transmitted across these channels using the same or hybrid modulation scheme according to a specific protocol and a selected elastic encryption scheme, as shown in Fig. 3c. An eavesdropper, referred to as Eve, cannot demodulate the correct information by intercepting only one channel. Furthermore, even if Eve captures the information from both channels but does not know its modulation and integration scheme, the correct information still cannot be successfully demodulated.

Subsequently, the bit streams transmitted through Channels 1 and 2 are mapped into corresponding time coding sequences. To ensure that the information-bearing signals are directionally transmitted to the intended recipient, Bob, a space coding sequence based on his specific location is calculated and superimposed on the time coding sequences to form the final space time coding sequences (see Supplementary Information Note 6 for details). Next, the ME controller translates these space time coding sequences into a control signal, which is then loaded onto the array to direct the signals accurately towards Bob. Since Eve is not located in the direction of the signal transmission, he receives the signal with a significantly reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Furthermore, any deviation from the intended direction of reception alters critical parameters, such as the signal phase, making it impossible for Eve to demodulate the correct information, as illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Next, the control signal is transmitted to the ME array via the FPGA and driver circuit as a complete ME, facilitating the modulation of the incident wave. As aforementioned, the ME has the capability to modulate EM waves across a wide frequency range. Consequently, the frequency of the incident wave can be adjusted according to a specific protocol and elastic cryptography scheme, allowing the ME to effectively modulate these frequencies. Eve, who either operates at a fixed frequency or is unaware of the frequency variation protocol, will be unable to accurately demodulate the information, as depicted in Fig. 3d.

At the receiving end (Bob), the signals are initially processed through a superheterodyne down-conversion module. Following this, the signals sampled by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) are converted into frequency spectrum data using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Utilizing the pre-defined encoding protocol, the bit streams from Channels 1 and 2 are demapped from this frequency spectrum data. The host then re-codes these bit streams to reconstruct the transmitted files. The ME-based multi-dimensional secure wireless communication prototype platform utilized in our experiment builds upon the previously developed metasurface-based direct wireless communication system prototype45, as shown in Fig. 4a, b (see “Methods” for details). It aims to deliver a balanced security solution for wireless communication through multi-dimensional integration, flexible configuration, and elastic selection, all achieved without the need for additional equipment.

Advantages of the proposed ME platform over the conventional alternatives in terms of hardware and control complexity are described below. On one hand, compared with the phased-array beamforming, ME requires only a single RF source and an FPGA controller to drive the metasurface. In contrast, the phased arrays demand a dedicated RF chain and phase shifter for each antenna, which leads to higher hardware cost, higher power consumption and more complicated calibration as the array size grows. On the other hand, compared with the conventional cryptographic approaches, the ME platform maintains the information confidentiality only through space-time coding, incurring negligible computational delay. Cryptographic solutions, however, rely on complex encryption and decryption algorithms that introduce substantial computational overhead and latency, and require high-performance chips and computer. Meanwhile, ME provides elastic and complementary security in multiple dimensions, enabling configuration to application and hardware constraints and preserving secrecy and link quality under partial compromise of any single dimension. Overall, the ME architecture achieves multi-dimensional security functions with a much simpler, lower-cost, and more energy-efficient implementation, making it particularly attractive for the SWaP-constrained wireless devices.

Directed secure transmission

The first security layer (L1) employs the physical-layer security (PLS) via directional transmission. This approach leverages ME’s dual-channel control to simultaneously steer the beams on Channels 1 and 2. As with the conventional metasurfaces, applying space coding sequences derived from the generalized Snell’s law to the two channels, the beams can be steered accordingly (see Supplementary Information Note 7 for details). Positioned on the intended boresight, Bob receives a signal with high phase stability and an increased SNR. By contrast, Eve, being off-axis, experiences degraded phase stability and reduced SNR, along with symbol-dependent and non-collinear amplitude-phase responses, rendering reliable demodulation unlikely.

We conducted information modulation and communication experiments on Channel 1 and Channel 2 to validate the directional secure transmission capabilities of the prototype platform. The concept is shown in Fig. 3b, demonstrating how the ME array is controlled through various space coding sequences to enable directional information transmission. In this experiment, Channels 1 and 2 were configured to transmit distinct images. We set a steering angle of 25o by loading the space coding sequence “301123001233.” We then emulated users at different azimuths by rotating the turntable in Fig. 4a across ±60o in 5o increments and measured the bit-error rate (BER) at each angle (Fig. 5a). In addition, the symbol duration for Channel 1 and Channel 2 is set to be \(T^{\prime}={T}_{0}\), with the modulation frequency for each channel fixed at 2.5 MHz, yielding a data transmission rate of 5 Mbps per channel. As demonstrated in Fig. 5b, Bob at the intended boresight reliably recovers the transmission, evidenced by the reconstructed image and the received constellation. Both channels exhibit BERs below 10-8, supporting reliable demodulation and a high-quality QPSK link. Because the experimental aperture is finite, the steered beam is comparatively broad. Consequently, off-axis BER does not jump abruptly to an undecodable regime; and reliable recovery can persist for angular offsets of roughly 5–10o. The broader mainlobe also improves the robustness at Bob. To achieve tighter directional secrecy (greater angular selectivity), one can scale to a larger ME array.

For Eve at large off-axis angles, low SNR and poor phase stability preclude the correct demodulation on either Channel 1 or Channel 2, yielding severely distorted constellations. In these regions, BERs for both channels are typically greater than 0.1 and tend toward the random-guessing limit of 0.5 (Fig. 5c). Because of finite beam-steering performance of the ME aperture and ambient multipath, occasional leakage can arise in unintended directions, most notably on Channel 1, where the fundamental is more interference-prone. As illustrated in Fig. 5(d), Channel 1 can exhibit BER close to 10-2, permitting partial message recovery. In contrast to the conventional metasurface-based directional PLS, our ME applies distinct space coding loading methods to Channels 1 and 2 for beam forming; under these conditions, Channel 2 remains undecodable. Distributing the payload across both channels (see the next subsection) therefore maintains system-level secrecy, since the message remains protected as long as at least one channel fails to demodulate. An experimental demonstration of the ME-based directional secure transmission is provided in Supplementary Video 1.

We next interpret the results through the lens of PLS using the classical wiretap communication model. Let the received SNRs at Bob and Eve be \({\gamma }_{b}\) and \({\gamma }_{e}\). Their channel capacities are \({\bar{c}}_{b}=\,\log (1+{\gamma }_{b})\) and \({\bar{c}}_{e}=\,\log (1+{\gamma }_{e})\). To quantify the performance, we use the normalized secrecy capacity55,

Furthermore, we constructed a link budget model for theoretical analysis that simultaneously considers both the Alice-Bob and Alice-Eve channels. The received SNR at \(i\in \{b,e\}\) can be expressed as

where \({P}_{t}\) is the transmitting power, \({G}_{t}\) and \({G}_{r}\) are the gains of transmitter and receiver antennas, \(G({\theta }_{i})\) denotes the ME-induced reflection gain at angle \({\theta }_{i}\), \({L}_{FSPL}\) is the free-space path loss (FSPL), \({N}_{0}\) is the additive white Gaussian noise power spectral density at −174 dBm/Hz, B is the system bandwidth, and NF is the noise figure of the entire system. The security benefit introduced by the ME is embedded in \(G({\theta }_{i})\), where the reflection gain is maximized at the intended direction (25° for Bob) and attenuated otherwise (e.g., 5° for Eve). Due to the domination of FSPL, the multipath effect can be neglected in this research. Based on this model, the SNR values of Bob and Eve can be evaluated and then substituted to obtain the secrecy capacity.

In our measurements, Bob’s lower BER corresponds a higher \({\gamma }_{b}\), while Eve exhibits a lower \({\gamma }_{e}\). Using the data obtained during the experiment in Fig. 5 (Bob at 25° and Eve at 5°), we estimate the SNRs and, per (4), obtain a normalized secrecy capacity of \({\bar{c}}_{s}=0.306\). Moreover, further improvements in \({\bar{c}}_{s}\) are limited by the ME aperture. According to array theory, enlarging the effective aperture size reduces the half-power beamwidth, which concentrates more radiated power towards Bob and increases the received SNR. Regarding sidelobes, the peak sidelobe of a uniformly excited array remains approximately unchanged, but the larger aperture leads to a denser angular distribution of sidelobes. Consequently, an eavesdropper located outside the main lobe is more likely to fall into a low-gain region, which effectively reduces \({\gamma }_{e}\). In terms of the link-budget model, aperture scaling therefore increases \(G({\theta }_{b})\) while decreasing \(G({\theta }_{e})\). Substituting them into the normalized secrecy capacity expression (4) implies that a higher secrecy level is achieved. Hence, a larger ME aperture not only improves the beamforming precision but also enhances the spatial selectivity and strengthens PLS.

Dual-channel and hybrid modulation secure transmission

The second security layer (L2) implements dual-channel secure transmission, in which two channels are controlled simultaneously yet independently. The confidential payload is partitioned and distributed across the channels under a prescribed allocation protocol and cryptographic scheme. This approach ensures that if Eve accesses data from only one channel or lacks the decryption method, the confidential information remains indecipherable. Figure 3c illustrates this fundamental concept. Additionally, the harmonic channel supports various modulation techniques, including linear and non-linear methods such as FSK and QAM. These techniques allow for the design of diverse and adaptable cryptographic schemes. Devices with abundant computational resources employ complex, resource-intensive cryptographic schemes, while resource-constrained devices utilize simpler alternatives, ensuring flexible configuration and elastic selection of wireless security.

Firstly, we demonstrate an encryption method using QPSK modulation for both Channels 1 and 2 as an example. The data is distributed across the two channels using a specific coding scheme, as depicted in L2-Mode 1 in Fig. 6a. This is one of many cryptographic schemes designed to minimize the impact of security measures on system performance, preserving communication rates and overall efficiency. The information intended for encryption during transmission is first decoded into a binary bit stream. These bit streams are subsequently divided into\(S\) groups, where each group \(s\) (\(0 < s\le S\)) contains \(c\) bits of data. When \(s\) is even, data is allocated to Channel 1 for transmission, and when \(s\) is odd, it is allocated to Channel 2. Essentially, the binary bit stream is alternately distributed to Channel 1 and Channel 2, with each segment consisting of \(c\) bits, where \(c\) is set to be 8 in this example.

a Diagram of different encryption modes. b The possible results that Eve demodulate. c Constellation diagram of Channel 1 and (d) constellation diagram of Channel 2, both demodulated by Bob at a communication rate of 25 Mbps, along with (e) the re-coding image information. f Constellation diagram of Channel 1 and (g) constellation diagram of Channel 2, demodulated by Bob at a communication rate of 100 Mbps, accompanied by (h) the corresponding re-coding image information. i The relationship between the BER received by Bob and the communication rate under Mode 1. In Channel 2 using 4-FSK, the spectra corresponding to the message symbols (j) “00”, (k) “01”, (l) “10”, and (m) “11” are transmitted. n The relationship between the BER received by Bob and the communication rate under Mode 2. o Single-frame data decryption time corresponding to Mode 2 and Mode 3.

Subsequently, the bit streams from both channels are first mapped into time coding sequences, followed by integration of space coding sequences, and then loaded onto the ME array, and ultimately demodulated by the universal software radio peripheral (USRP). It is crucial for Bob to concurrently receive and demodulate signals from both Channel 1 and 2, ensuring that the decoding method at the receiver aligns with our coding scheme at the transmitter to accurately retrieve data. Conversely, the distributed transmission strategy ensures that if Eve intercepts and demodulates only a single channel or lacks the decryption method, she cannot retrieve the correct data. The possible results of Eve’s demodulation of Channel 1 or Channel 2, when done individually, are illustrated in Fig. 6b under “Information demodulated by Eve L2-Mode 1.” It can be attributed to the fact that the program in the previous section can only process single-channel information, and there is a high possibility for incorrect demodulation.

The performance of the dual-channel secure transmission Mode 1 is then evaluated. The constellation diagrams and achievable communication rates for both Channel 1 and Channel 2 remain unaffected by encryption in this mode. Assuming a single-channel information symbol duration of \(T{\hbox{'}}={T}_{0}\), the communication rate of a single ME array aperture equals four times the modulation rate \({f}_{0}\) of a single channel. We configure both Channel 1 and Channel 2 to direct their beams towards 35o and vary the modulation rate of the two channels to assess performance across different communication rates. At a set communication rate of 25Mbps, the constellation diagrams demodulated by Bob for Channel 1 and Channel 2 are depicted in Fig. 6c, d, respectively. Compared to the constellation diagrams shown in Fig. 5, the compactness of the constellations begins to deteriorate due to the increased rate, leading to a decrease in error vector magnitude (EVM) and the appearance of slight noise artifacts in the re-coded images, as illustrated in Fig. 6e. As the communication rate escalates to 100 Mbps, the EVM of the constellation diagrams for Channel 1 and Channel 2, as demodulated by Bob, shows further deterioration, as depicted in Fig. 6f, g. Correspondingly, the re-coded images begin to exhibit significant noise and color distortions, as illustrated in Fig. 6h. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6i, the BER of the proposed prototype platform has been measured with the communication rate varying from 10 Mbps to 100 Mbps. As the communication rate increases, the BER also rises; however, even at the highest tested rate of 100 Mbps, the BER remains below \({10}^{-1}\). In addition, to assess real-world readiness, we evaluate the system performance in multipath and non-line-of-sight (NLoS) environments (see Supplementary Information Note 8 for details). These results conclusively demonstrate the effectiveness of dual-channel distributed transmission in enhancing wireless security (an experimental demonstration is provided in Supplementary Video 2). Importantly, these results were obtained without incorporating additional hardware filtering or sophisticated software algorithm enhancements. In practical applications, implementing a series of optimized operations could significantly lower BER and enhance overall communication performance (see Supplementary Information Note 9 for details). We can also use the ME’s flexible coding to realize higher-order PSK and QAM on the channels, increasing the spectral efficiency and, in turn, enhancing the overall system performance (see Supplementary Information Note 10 for details).

To showcase the system’s configurability, L2-Mode 2 implements a hybrid-modulation secrecy scheme: Channel 1 remains QPSK, whereas Channel 2 employs M-ary FSK. Such heterogeneous modulation is relevant to V2X links, where the infrastructure nodes can employ higher-order modulation while the vehicles with embedded processors rely on simpler schemes, maintaining secrecy without increasing the device complexity. The FSK order can be selected to meet system requirements (e.g., 2-FSK, 4-FSK, or 8-FSK); here we illustrate the 4-FSK case. We denote the modulation periods on Channels 1 and 2 by \({T}_{1}\) and \({T}_{2}\). For Channel 2, symbol “00” maps to \({f}_{1}\) with \({T}_{2}={T}_{1}\); “01” to \({f}_{2}\) with \({T}_{2}={T}_{1}/2\); “10” to \({f}_{3}\) with \({T}_{2}={T}_{1}/3\); and “11” to \({f}_{4}\) with \({T}_{2}={T}_{1}/6\). The Channel 1 message-symbol duration is \(T^{\prime}={T}_{1}\), whereas Channel 2 symbol durations are \(T^{\prime}={T}_{2}\), \(T^{\prime}=2{T}_{2}\), \(T^{\prime}=3{T}_{2}\), and \(T^{\prime}=6{T}_{2}\) for the four symbols, respectively. This design keeps the two channels rate-matched, but the time coding requires fine-grained FPGA timing, imposing stricter demands on the ME controller. With the present hardware, the minimum \({T}_{1}\) is 240 ns, corresponding to \({f}_{1}\) = 4.17 MHz, \({f}_{2}\) = 8.33 MHz, \({f}_{3}\) = 12.5 MHz, and \({f}_{4}\) = 25 MHz. Each of Channels 1 and 2 operates at 8.33 Mbps, giving an aggregate system data rate of 16.67 Mbps. Further scaling would require upgrades to the controller, specifically, higher-performance FPGA logic and clock circuitry to provide finer timing resolution and stability. To verify 4-FSK on Channel 2, we measured harmonic amplitudes for each symbol (Fig. 6j–m), normalized them to the fundamental, and reported linear-scale values. The spectrum shows that the power distribution is consistent with previous theoretical analysis and is concentrated in the fundamental and 1st harmonics. This means that despite the integer multiple relationship between \({f}_{1}\)–\({f}_{4}\), the mutual interference is limited, thus demonstrating the feasibility of 4-FSK.

We then evaluated Mode 2 under the same data-distributing secrecy scheme as Mode 1. As in Mode 1, single-channel interception by Eve, even with the correct demodulator, fails to reconstruct the payload, as presented in Fig. 6b. Owing to the added frequency dimension and heterogeneous modulation, the two channels obey incompatible detection models, forcing Eve to perform multi-hypothesis joint detection and synchronization; Mode 2 is therefore substantially harder to decode. We next profiled BER versus data rate (Fig. 6n). Though BER rises with rate, it remains below 10-3 across all configurations, confirming the efficacy of the QPSK/4-FSK hybrid modulation link. In addition, we show the related experiments in Supplementary Video 3.

To demonstrate the elastic configurability, we introduce L2-Mode 3, which integrates the lightweight cryptography into Mode 2 framework. The raw payload is segmented into fixed-length frames, each processed independently using ChaCha20 stream cipher. ChaCha20 is an ARX-based cipher with a 256-bit key, widely recognized for its efficiency and strong security margin. We firstly mask the keystream via XOR, followed by a keyed and invertible intra-frame permutation (Fisher-Yates) whose randomness is generated from ChaCha20 under a domain-separated counter to avoid keystream reuse. The permuted ciphertext is demultiplexed across the two channels by sending alternating bytes (even/odd). At the receiver, Bob reconstructs the ciphertext by re-interleaving the two streams, recomputing and inverting the permutation, and finally XORing with the corresponding keystream to recover the original payload. For an eavesdropper, a single-channel capture is empirically indistinguishable from white Gaussian noise. Even if both channels are obtained, without the correct key and nonce, decryption remains infeasible. Figure 6(b) illustrates this outcome, where demodulated data of Eve appears white-noise-like.

Since Mode 3 preserves the distribution and modulation scheme of Mode 2, its baseline link performance is comparable. The cryptographic algorithm in Mode 3, which integrates with our dual-channel and hybrid-modulation secure-transmission scheme, provides higher security for data transmission, but substantially increases the user’s resource consumption. Under identical host-USRP demodulator settings, Modes 1 and 2 recover a frame within 2 ms, whereas Mode 3 takes over 30 ms for the same frame length, as shown in Fig. 6o. These results highlight the elastic configuration of ME, allowing the users to select appropriate cryptographic methods according to available resources to balance between the computational efficiency and security. For detailed experimental demonstration, please see Supplementary Video 4.

Frequency hopping secure transmission

The ME and manipulation mechanism we designed are capable of controlling EM waves over a wideband range. This capability enables ultra-wideband frequency hopping communication and provides unprecedented security for wireless communication. Prior to implementing an experimental prototype platform with frequency hopping communication capabilities, we conducted experiments to verify the ultra-wide operating bandwidth of the ME. As shown in Fig. 7a, during the experiment, the host sends standard commands for programmable instruments (SCPI) to the transmitter signal source to control the system’s operating frequency. The receiver synchronously adjusts its local oscillator output frequency under its host control to ensure that the USRP consistently processes the 1 GHz received signal. To maintain clock accuracy and system synchronization, the FPGA used as ME controller also generates synchronization and trigger signals for the signal source. The receiver’s synchronization signal is directly cascaded with that of the transmitter. In practical applications, a GPS disciplined oscillator can be employed to achieve system-wide synchronization. To evaluate the respective operating bandwidth of the two channels, Channels 1 and 2 are configured to transmit data at a communication rate of 1 Mbps for each, using QPSK modulation and directed at 35o. By bilaterally adjusting the system’s operating frequency starting from 52.8 GHz, we observe that the BER of both channels are below 10-2 within the frequency range of ~42–63 GHz, as shown in Table 1. Additionally, we provide a deeper analysis of the impact of frequency offset and phase distortion on the ME’s wideband performance (see Supplementary Information Note 11 for details). In instances where no error bits have been detected after measuring more than 108 data bits, we record the BER as < 1 × 10-8. Beyond this frequency range, the BER of Channel 1 rapidly increases to 4.98 × 10-2 at 41.5 GHz and 2.36 × 10-2 at 64 GHz. Conversely, for Channel 2 alone, the BER is 1.36 × 10-5 at 41.5 GHz and 8.53 × 10-6 at 74.7 GHz, indicating sustained effective communication. The relative stability of Channel 2’s BER compared to Channel 1 can be attributed to its signal generation method. Channel 1 utilizes a fundamental signal produced by an RF signal source, which is more susceptible to environmental noise and multipath effects. On the contrary, Channel 2’s harmonic signal, generated through ME modulation, is less affected by such external factors. These results not only confirm that our prototype platform can operate within an ultra-wideband range but also highlight the ME’s capability to effectively manipulate the phase of EM waves across this extensive bandwidth. This enables ultra-wideband frequency hopping communication, significantly enhancing wireless security. Since multi-dimensional wireless security communication based on ME requires the simultaneous utilization of Channel 1 and Channel 2, we select a frequency range of 43-63 GHz, totaling 20 GHz for frequency hopping communication. This design choice also aligns with the industrial IoT environments, where narrowband interference from motors and switching devices is common, making wideband hopping essential for both confidentiality and robustness.

a Experimental configuration diagram. b Frequency codebook diagram. c Image received and demodulated by Bob with a frequency hopping interval of 55.04 ms. Stripe-like error distortions in the image are caused by the long response time of the signal source. d The variation of the BER of data received by Bob with respect to the frequency switching interval.

In the experimental configuration, we randomly select \(n\) frequencies (\({f}_{M1},{f}_{M2},{..}.,{f}_{Mn}\)) within the range of 43-63 GHz. The time duration is divided into \(m\) time slots, each maintaining a constant frequency to ensure uniform time intervals for frequency switching. A predefined frequency-switching sequence is established between these time slots, facilitating cyclic switching among the selected\(n\) frequencies. This sequence forms a frequency code book, employed in frequency-hopping communication, as illustrated in Fig. 7b. At the transmitter, the frequency codebook is sent to the signal source by the host through SCPI commands. Concurrently, parameters such as time slots \(m\) are sent from the host to the FPGA controller. The FPGA controller then generates the corresponding trigger signals based on these parameters. Upon detecting the rising edge of a trigger signal, the signal source switches the system’s operating frequency in accordance with the frequency codebook. Successful reception of the data by Bob depends on his mixer’s local oscillator source switching frequencies in synchronization with Alice. This ensures that the transmitted data is received at the intermediate frequency and correctly demodulated. Since Eve lacks access to the frequency codebook and cannot monitor full bandwidth simultaneously, the transmission security is significantly enhanced, achieving a higher level of wireless security.

In our experiments, we configured the directional secure transmission angle to 35o and set the dual-channel secure transmission mode to L2-Mode 1. We prepared a frequency- hopping codebook and set the communication rate for each channel to be 1 Mbps, achieving an overall system communication rate of 2 Mbps (see Supplementary Information Note 12 for details). Data reception was then tested under various frequency-hopping intervals. Figure 7(c) displays the received and demodulated data image when the frequency-hopping interval is set to 55.04 ms. Notably, stripe-like error distortions are visible in the image, attributed to the relatively long frequency switching response time of the employed RF signal source (Keysight E8257D, with a CW switching speed of ~7 ms). This delay leads to signal distortion during the frequency switching process, ultimately affecting data re-code. However, this impact diminishes as the frequency-hopping interval increases. We measured the BER at various hopping intervals (13.76 ms, 55.04 ms, 137.6 ms, 550.4 ms), as shown in Fig. 7d. The results indicate that even at the shortest interval of 13.76 ms, BER remains below \({10}^{-1}\). Therefore, the designed ME array, manipulation mechanism, and control strategy effectively accomplish the task of frequency-hopping encrypted communication (an experimental demonstration is provided in Supplementary Video 5). The performance of frequency-hopping communications can be further improved by incorporating software processing algorithms and adopting RF signal sources with faster CW switching speeds.

Discussion

We propose a novel multi-dimensional wireless security transmission architecture, termed ME, leveraging the dual-channel and ultra-wideband direct information modulation capabilities of the IM. This innovative framework encompasses directional secure transmission, distributed and hybrid modulation secure transmission, and frequency-hopping secure transmission. It integrates multiple security technologies, supports flexible configuration, and allows for elastic selection, all without requiring additional hardware. As a representative example, we conduct experimental validation of ME in the V band. Firstly, our method achieves beamforming within a range of ±45o, facilitating directional and secure information transmission. Secondly, through dual-channel control of EM waves via the ME array, either identical or hybrid modulation schemes, combined with cryptographic protocols, enable distributed transmission across two channels. This approach ensures wireless security while maintaining a communication rate of up to 100 Mbps. Thirdly, frequency-hopping communication is realized in the 43 ~ 63 GHz, significantly enhancing system security. In future applications, users can flexibly select one or more wireless security technologies and configure cryptographic schemes as needed, providing an optimized balance between security, efficiency, and cost.

Building on this work and addressing the limitations identified in the manuscript, we will pursue several directions. We will design higher-performance and larger-aperture ME arrays, equalize state amplitudes, and reduce phase-gradient errors, targeting higher data rates and broader operating bandwidths. A larger aperture will sharpen beam pointing and strengthen directional secrecy. We will upgrade the control hardware and bias network to shorten edge times and raise the symbol rate. With a richer codebook, we plan to employ higher-order modulation to boost spectral efficiency and secrecy margin. In parallel, we will analyze the control and bias networks, timing skew, and power/ground signatures, and extend the design to mitigate side-channel leakage. We will implement adaptive frequency hopping with online hopset adaptation and per-hop power allocation; using the measured interference statistics, we will constrain hop collisions and increase effective SNR. We will also build an anti-jamming testbed to assess the ME robustness, including controlled studies of barrage and partial-band jamming under hopping. Finally, through the system co-design, we will investigate network synchronization and multi-user scheduling to translate ME into the practical mmWave and THz links.

Taken together with continued advances in ME hardware and control, these steps should enable the deployment of elastic, complementary and multi-dimensional security in the next-generation wireless systems. The resulting ME-based architecture is expected to deliver a low-complexity, low-cost, and highly reliable solution for future secure communications.

Methods

Fabricated ME array

The ME array we fabricated, which consists of 12 × 8 meta-atoms, is depicted in Fig. 8a. As a component of ME, this design of array is not the main contribution of this study. The array used here was designed in the same way as the array used in our previous work to verify the theory of simultaneous manipulation of fundamental and harmonic waves56. To provide a detailed view of the actual state of the meta-atom, an optical microscope magnified image is presented in Fig. 8b. The array is fabricated using printed circuit board (PCB) technology, with PIN diodes bonded using conductive silver glue. The primary reasons for deviations in the optimal operating frequency include: (1) Influence of PCB Process Accuracy: The accuracy of the PCB manufacturing process may cause deviations between actual sample sizes and design specifications. As evident from Fig. 8b, the precision of the manufactured sample is not optimal. These processing errors, alongside the tolerance levels, which are comparable to the meta-atom size, can lead to a shift in the resonance point. (2) Parasitic Capacitance from Surface Mounting: The surface mounting process of the PIN diodes introduces parasitic capacitance that affects the meta-atom’s performance. As shown in Fig. 8b, the bonding points are not uniform, which will also influence the performance.

Experimental system prototype construction

The primary components of the system are illustrated in Fig. 4a, b. Several enhancements were implemented to meet the requirements of the current experiment. Specifically, the frequency multiplier, mixer, and horn antenna were substituted with models compatible with the V band. Additionally, the FPGA controller and host system were upgraded to support dual-channel signal processing at the software level. The FPGA controller also enables the output of a trigger signal for controlling frequency hopping communication.

The experimental setup operates as follows: The transmission signal originates from a microwave signal source (Agilent E8257D), which undergoes frequency multiplication via a quadrupler (ATMicrowave AT-AM4-4575-18TY) before being radiated by a horn antenna. As a component of the ME, under the directive control of the host, the FPGA controller (Xilinx Kintex-7 XC7K325T) and its associated driver circuitry generate space-time coding sequence signals. These control signals are then imparted onto the ME array, enabling precise directional steering and information modulation for both Channel 1 and Channel 2. At the receiving end, due to the carrier signal frequency being higher than the reception frequency of typical instruments, a superheterodyne structure is employed to down-convert the signals received by the horn antenna. These signals are mixed using a mixer (ATMicrowave AT-MIX-5075H) and down-converted to 1 GHz. A microwave signal source (Agilent E8257D) connected to a quadrupler (ATMicrowave AT-AM4-4575-18TY) generates the local oscillator signal required for this process. If the directionality of the beam after ME array modulation is to be measured, the setup includes a spectrum analyzer (Keysight N9010A) coupled with a turntable to capture the directional pattern. Alternatively, if the communication performance of the platform is under evaluation, the setup is connected to a Universal Software Radio Peripheral (USRP) which samples the signal and performs baseband operations. This configuration enables the acquisition of received spectrum data, de-mapping of the bit stream, and re-coding to recover the transmitted image.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are presented in the paper and in the Supplementary information, or can be made available upon request by contacting the corresponding authors.

References

Shi, Y. et al. Task-oriented communications for 6G: vision, principles, and technologies. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 30, 78–85 (2023).

Mao, B., Liu, J., Wu, Y. & Kato, N. Security and privacy on 6G network edge: a survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 25, 1095–1127 (2023).

Dang, S., Amin, O., Shihada, B. & Alouini, M.-S. What should 6G be? Nat. Electron. 3, 20–29 (2020).

You, X. et al. Towards 6G wireless communication networks: vision, enabling technologies, and new paradigm shifts. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 64, 110301 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Physical Layer Security in Wireless Cooperative Networks. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Illi, E. et al. Physical Layer Security For Authentication, Confidentiality, And Malicious Node Detection: A Paradigm Shift In Securing IoT Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 26, 347–388 (2024).

Iwamoto, M., Ohta, K. & Shikata, J. Security formalizations and their relationships for encryption and key agreement in information-theoretic cryptography. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 64, 654–685 (2018).

Wu, Y. et al. A survey of physical layer security techniques for 5G wireless networks and challenges ahead. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 36, 679–695 (2018).

Waqas, M. et al. The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in wireless networks security: principle, practice and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 5215–5261 (2022).

Diamanti, E., Lo, H.-K., Qi, B. & Yuan, Z. Practical challenges in quantum key distribution. Npj Quantum Inf. 2, 1–12 (2016).

Angueira, P. et al. A survey of physical layer techniques for secure wireless communications in industry. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 24, 810–838 (2022).

Mitev, M., Chorti, A., Poor, H. V. & Fettweis, G. P. What physical layer security can do for 6G security. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 4, 375–388 (2023).

Soltani, R., Goeckel, D., Towsley, D., Bash, B. A. & Guha, S. Covert wireless communication with artificial noise generation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 17, 7252–7267 (2018).

Xu, L., Wang, B., Li, H. & Cheng, Z. Enhancing physical layer security in dual-function radar-communication systems with hybrid beamforming architecture. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 13, 1566–1570 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Security analysis of triangle channel-based physical layer key generation in wireless backscatter communications. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 18, 948–964 (2023).

Letafati, M., Kuhestani, A., Behroozi, H. & Ng, D. W. K. Jamming-resilient frequency hopping-aided secure communication for internet-of-things in the presence of an untrusted relay. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 19, 6771–6785 (2020).

Li, L., Zhao, H., Liu, C., Li, L. & Cui, T. J. Intelligent metasurfaces: control, communication and computing. eLight 2, 7 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. High-performance cost efficient simultaneous wireless information and power transfers deploying jointly modulated amplifying programmable metasurface. Nat. Commun. 14, 6002 (2023).

Mu, X., Xu, J., Liu, Y. & Hanzo, L. Reconfigurable intelligent surface-aided near-field communications for 6G: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 19, 65–74 (2024).

Buchnev, O., Podoliak, N., Kaltenecker, K., Walther, M. & Fedotov, V. A. Metasurface-Based Optical Liquid Crystal Cell as an Ultrathin Spatial Phase Modulator for THz Applications. ACS Photonics 7, 3199–3206 (2020).

Fu, X. et al. Flexible Terahertz beam manipulations based on liquid-crystal-integrated programmable metasurfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 22287–22294 (2022).

Chen, B. et al. Electrically addressable integrated intelligent terahertz metasurface. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd1296 (2022).

Huang, M. et al. Evolutionary games-assisted synchronization metasurface for simultaneous multisource invisibility cloaking. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401909 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. A tunable metasurface with switchable functionalities: from perfect transparency to perfect absorption. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1901548 (2020).

Takeshita, H. et al. Frequency-hopping wave engineering with metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 15, 196 (2024).

Cui, T. J., Qi, M. Q., Wan, X., Zhao, J. & Cheng, Q. Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e218–e218 (2014).

Leitis, A. et al. All-dielectric programmable huygens’ metasurfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910259 (2020).

Lan, F. et al. Real-time programmable metasurface for terahertz multifunctional wave front engineering. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 191 (2023).

Forouzmand, A. & Mosallaei, H. A tunable semiconductor-based transmissive metasurface: dynamic phase control with high transmission level. Laser Photonics Rev. 14, 1900353 (2020).

Wu, X. Y. et al. An ultrathin, fast-response, large-scale liquid-crystal-facilitated multi-functional reconfigurable metasurface for comprehensive wavefront modulation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402170 (2024).

Sleasman, T. et al. Computational imaging with dynamic metasurfaces: a recipe for simple and low-cost microwave imaging. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 64, 123–134 (2022).

Venkatesh, S., Lu, X., Saeidi, H. & Sengupta, K. A high-speed programmable and scalable terahertz holographic metasurface based on tiled CMOS chips. Nat. Electron. 3, 785–793 (2020).

Wang, P. et al. Efficient manipulation of near-field terahertz waves: individually addressable transmissive meta-device. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2400617 (2024).

Soric, J., Ra’di, Y., Farfan, D. & Alù, A. Radio-transparent dipole antenna based on a metasurface cloak. Nat. Commun. 13, 1114 (2022).

Liao, J. et al. Polarization-insensitive metasurface cloak for dynamic illusions with an electromagnetic transparent window. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 16953–16962 (2023).

Wang, S. R. et al. Radar micro-doppler signature generation based on time-domain digital coding metasurface. Adv. Sci. 11, 2306850 (2024).

Bagheri, M. O., Gharamohammadi, A., Abu-Sardanah, S., Ramahi, O. M. & Shaker, G. Radar near-field sensing using metasurface for biomedical applications. Commun. Eng. 3, 1–15 (2024).

Wang, X. & Caloz, C. Spread-spectrum selective camouflaging based on time-modulated metasurface. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69, 286–295 (2021).

Taravati, S. & Eleftheriades, G. V. Microwave space-time-modulated metasurfaces. ACS Photonics 9, 305–318 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. Transmissive RIS for B5G communications: design, prototyping, and experimental demonstrations. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 6605–6615 (2023).

Chen, J., Liang, Y.-C., Cheng, H. V. & Yu, W. Channel estimation for reconfigurable intelligent surface aided multi-user mmWave MIMO systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 22, 6853–6869 (2023).

Tang, W. et al. Wireless communications with programmable metasurface: new paradigms, opportunities, and challenges on transceiver design. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 27, 180–187 (2020).

Chen, M. Z. et al. Accurate and broadband manipulations of harmonic amplitudes and phases to reach 256 QAM millimeter-wave wireless communications by time-domain digital coding metasurface. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwab134 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Nonlinear information metasurface for second-harmonic generation, manipulation, and backscatter communication. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 28752–28763 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Toward Sub-Terahertz: space-time coding metasurface transmitter for wideband wireless communications. Adv. Sci. 10, 2304278 (2023).

Shu, F. et al. Beamforming and transmit power design for intelligent reconfigurable surface-aided secure spatial modulation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 16, 933–949 (2022).

Zhang, J., Du, H., Sun, Q., Ai, B. & Ng, D. W. K. Physical layer security enhancement with reconfigurable intelligent surface-aided networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 16, 3480–3495 (2021).

Wang, H. L., Ma, H. F. & Cui, T. J. A polarization-modulated information metasurface for encryption wireless communications. Adv. Sci. 9, 1–1 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. A wireless communication scheme based on space- and frequency-division multiplexing using digital metasurfaces. Nat. Electron. 4, 218–227 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Two-dimensional and high-order directional information modulations for secure communications based on programmable metasurface. Nat. Commun. 15, 6140 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Metasurface-assisted wireless communication with physical level information encryption. Adv. Sci. 9, 2204558 (2022).

Sun, S., Gou, Y., Cui, T. J. & Ma, H. F. High-security nondeterministic encryption communication based on spin-space-frequency multiplexing metasurface. PhotoniX 5, 38 (2024).

Wang, H. L. et al. Multichannel highly secure wireless communication system with information camouflage capability. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk7557 (2024).

Yu, N. et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 334, 333–337 (2011).

Ma, J. et al. Security and eavesdropping in terahertz wireless links. Nature 563, 89–93 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Ultra-wideband simultaneous manipulations of fundamental and harmonic waves based on space-time coding metasurface: basic principles and mmwave applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401482 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant U23A20279 (received by X.F.) and 62288101 (received by T.J.C.), the 111 Project under grant 111-2-05 (received by T.J.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., X.F. and T.J.C. conceived the idea. Y.L., W.G., X.F., and C.H. developed and carried out the theoretical analysis. Y.L. and X.F. designed, fabricated and measured the meta-encryptor. Y.L., X.F., and L.Z. conducted the experiments. T.J.C. and X.F. supervised the whole project. Y.L. drafted the manuscript. X.F., W.G., C.H., L.Z., L.J., and T.J.C. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Vasileios Ataloglou and Hamidreza Taghvaee for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Gao, W., Fu, X. et al. Meta-encryptor with multi-dimensional security architecture for wireless communications. Nat Commun 16, 11635 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66668-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66668-x