Abstract

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) can reduce aviation greenhouse gas emissions, yet their production scale-up to meet policy goals remains unexplored. Here, we describe the Global SAF Capacity Database to quantify global and European Union (EU) SAF capacity, comparing it to production capacity announcements. Despite announcements of 9.1 Mt year−1 (2.2 Mt year−1 in the EU) by 2024 and 38.9 Mt year−1 (9.3 Mt year−1 in the EU) by 2030, only 24% (26% in the EU) of the announced capacity was realized on time by 2024. Over 40% of the announced capacity for 2030 risks delays or cancellations. Using a diffusion model parametrized by announced capacity, realization rates, expected demand, and historical growth analogs, we calculate SAF potential scale-up to meet net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Even if SAF follows the rapid scale-up of solar and wind energy, the global and EU capacity will fall short of respective targets by 42% and 18% in 2030, and 7% and 5% in 2050.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, global aviation accounts for 2–3% of greenhouse gas emissions, and its climate impact is expected to grow in the absence of significant mitigation measures due to air traffic growth1. Achieving net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 is ambitious as aviation is a hard-to-abate sector due to its reliance on energy-dense fuels and non-CO2 impacts2,3. Proposed solutions include operational changes, improved aircraft technology, and the utilization of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF)4. SAF, including bio-based and synthetic fuels, can replace conventional jet fuel without infrastructure changes and is expected to represent at least 60% of aviation’s emission reductions5,6. While various production pathways exist to produce SAF, its production remains costly due to high feedstock prices, high conversion costs, and/or low conversion efficiencies7,8.

Policymakers have adopted measures to support production scaling and stimulate demand. In its long-term aspirational goal (LTAG), the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has defined several scenarios of net-zero carbon emissions by 20509. For the near term, ICAO has adopted a vision to reduce CO2 emissions in international aviation 5% by 2030 compared to the 2019 baseline using SAF and other aviation cleaner fuels10. Individual governments are also moving forward with SAF adoption plans. The European Union’s ReFuelEU plan mandates SAF blending at EU airports, starting at 2% in 2025 and progressively increasing to 70% by 205011. Other countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, India, Brazil, and China, are implementing or proposing similar demand-side regulations. In contrast, the United States focuses on supply-side measures such as tax credits and subsidies to stimulate the production of SAF. In light of these policy efforts, global SAF production in 2024 doubled compared to 2023, yet production volumes remain low at 0.3% of global jet fuel production12. Considering the ambitious targets for scaling up SAF and achieving climate goals for aviation, there is a need to evaluate the current worldwide SAF production capacity and assess the feasibility of achieving the short- and long-term policy targets for increasing SAF adoption. For this purpose, it is important to understand the potential SAF supply growth while accounting for technological success and SAF demand uncertainties.

In this paper, we quantify the current SAF production capacity and the future potential deployment to meet global and EU aviation climate goals out to 2050. The EU is a key focus, representing the largest mandated SAF market through 2050. First, we develop the Global SAF Capacity Database (DB), which contains data on companies producing or planning to produce SAF. This data is sourced from public announcements between 2013 and 2024. Using this DB, we quantify the operational SAF production capacity in 2024 and the announced SAF capacity by 2030, globally and in the EU, categorized by production region and conversion technology. We further classify SAF production projects in our database by development status, and define the historic realization rate of announced SAF capacity defined as the proportion of announced capacity that became operational. From this, we calculate the difference between the SAF capacity that was expected to be operational by the end of 2024 and the capacity that became operational, denoted as the realization gap. We then define the potential scale-up of SAF production capacity deployment out to 2050. For this purpose, we integrate the estimated production capacity by the end of 2025 and the observed realization rate derived from the Global SAF Capacity DB into a technology diffusion model that accounts for heterogeneous growth rates derived from historical analogies in energy technologies, 1) biofuels (biodiesel and biogasoline) and ethanol and 2) solar, and wind power. Finally, the potential scale-up of SAF production capacity is compared to the global aviation’s climate targets set by ICAO and the EU’s SAF mandate.

Results

Global SAF production capacity and realization gaps

We collated the global SAF production capacity announcements through 2030 and the realization gap using data from public announcements. As shown in Table 1, all operational SAF production facilities in 2024 are located in North America, Europe, and East Asia, with the United States and Spain having the largest number of operational facilities (four each). By 2030, SAF production capacity is announced in additional regions, particularly South America and Southeast Asia. If announced projects succeed, the United States will maintain the highest number of operating facilities (44), followed by France (11) and China, Spain, and the United Kingdom (10). In addition, a capacity increase of at least 5.0 Mt year−1 would be realized annually through 2030, except for 2029 (Fig. 1a), if all announced projects are realized. This corresponds to a cumulative SAF production capacity of 35.1 Mt year−1 by 2030. The majority of SAF volumes would be produced in North America (37%), Europe (26%), and South and East Asia (23%). Smaller cumulative contributions, totaling 4.7 Mt year−1, are anticipated in Central and South America (9%), the Middle East and Africa (3%), and Oceania (2%) (Fig. 1b).

The figure shows the new SAF capacity by announced realization year and world region (a) and the cumulative SAF capacity from announcements to be operational by 2030, by world region (b). The capacity, expressed in Mt year−1, is based on the average jet fuel ratio (midpoint between low and high ratio in Supplementary Table 1). The lower announced capacity in 2029 reflects a common tendency for companies to target operation either by 2030 or before 2028.

Globally, 2030 production capacity is expected to remain dominated by the conversion process of hydro-processed esters and fatty acids (HEFA). Each year, except for 2029, at least 48% of the newly added capacity is projected to come from HEFA (Fig. 2a). By 2030, cumulative HEFA-based SAF production is projected to reach 22.2 Mt year−1, representing approximately 63% of the total cumulative announced SAF capacity (35.10 Mt year−1, based on the average jet fuel yield ratio, see Fig. 2c). Beyond HEFA, Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) SAF is expected to account for 11% of total cumulative SAF capacity by 2030, followed by Power-to-Liquid (PtL) and Fischer-Tropsch (FT), contributing 8% and 10% respectively. Co-processing is anticipated to make up 6.5%, although future announcements for this technology are not always made public, which may mean this pathway is underestimated. Other conversion technologies collectively account for 1.5%. We note that these figures reflect announced capacities, which may not fully translate into operational capacity by 2030. In particular, HEFA production may face constraints due to limited feedstock availability and scalability challenges. As such, diversifying SAF production technologies will likely be needed to achieve the announced SAF production plans.

The figure shows the new SAF capacity by announced realization year globally (a) and in the EU (b) and the cumulative SAF capacity by realization year derived from announcements globally (c) and in the EU (d). All figures are generated using the average jet fuel ratio from Supplementary Table 1 and are representative of SAF production capacities if all announced projects are realized. Other SAF production technologies include catalytic hydrothermalysis, hydrothermal liquefaction, pyrolysis, solar thermochemistry, and synthesized iso-paraffins.

In the EU, the composition of the SAF capacity by conversion process differs from the global trend. Through 2027, HEFA technology would continue to dominate EU-based SAF production capacity, if all announced projects are realized, accounting for 89% of newly added capacity (Fig. 2b). Starting in 2028, significant Power-to-Liquid (PtL) volumes are announced for entry into the EU supply. Of the 1.5 Mt year−1 new SAF capacity, which has been announced to become operational in 2028 and 2029, 80% would come from announced PtL facilities. PtL refers to a technology pathway that produces liquid fuels by using renewable electricity to generate hydrogen (via electrolysis), which is then combined with captured carbon dioxide to synthesize hydrocarbons (e.g. via Fischer-Tropsch or Methanol routes) suitable for aviation fuel. PtL technologies thus represent an additional pathway to diversify SAF production. Yet, several challenges for PtL persist, such as technological maturity, elevated production costs, high overarching demand for low-carbon electricity and green hydrogen, as well as securing sufficient and sufficiently cheap CO2 sources13. The cumulative announced capacity for all conversion technologies in the EU is 8.1 Mt year−1 in 2030. This exceeds the estimated 2.8 Mt year−1 required to meet the 2030 ReFuelEU mandate. In addition to overall SAF targets, the EU mandate requires synthetic fuels (PtL) to make up 1.2% of all jet fuel supplied at EU airports by 2030 which translates into 0.6 Mt year−1 of PtL SAF14. With the cumulative announced PtL capacity in the EU reaching 1.76 Mt year−1 by 2030, the synthetic fuel requirements could be met with internal production. Globally, the announced capacity exceeds the near-term ICAO vision of 5% emission reduction, which is reported to require 23 Mt year−1 of SAF15. The potential surplus derived from the announced capacity suggests that the SAF requirements in 2030 could be met, provided that 66% and 34% of the announced capacity, respectively, globally and in the EU, is realized on time. However, successful on-time completion of a significant number of announced projects will likely face challenges. Many projects may experience delays, cancellations, or failures. To illustrate the gap between announced production capacity and realized capacity, we compare the announced SAF capacity globally and in the EU over the past five years (see Fig. 3).

The figure shows the cumulative SAF production capacity globally (a) and in the European Union (EU) (b) announced during and before a specific year versus realized SAF capacity. The light red area defines the SAF capacity range assuming high jet ratio and low jet ratio (see Supplementary Table 1). The difference between the announced SAF capacity by 2023 and by 2024 and the SAF capacity operational in 2023 and 2024 constitutes the respective realization gap in 2023 and 2024 which can be more clearly visualized in the panels on the right hand side. The range between low and high jet fuel ratios is shown for announcements made by 2024 and realized capacity, in addition to the capacity reflecting the average jet fuel ratio. The data reveal a steady increase in announced capacity, reaching 38.9 Mt year−1 (ranging from 24.2 to 53.6 Mt year−1) and 9.3 Mt year−1 (7.2–11.4) in 2030, globally and in the EU, respectively. These values are higher than the cumulative announced capacity shown in Fig. 2c,d as they include capacity from all announced projects, including failed and paused projects. a This also includes the value of global SAF production in 2024 of 1 Mt year −1 as reported by the International Air Transport Association (IATA)12 whereas (b) includes the value of EU SAF production of 0.3 Mt year−1 in 2023 as reported by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA)51.

Through 2024, the realized SAF capacity has consistently fallen short of announced volumes. The difference between announced and actual operational capacity constitutes the realization gap. Historical data shows that this gap has widened. In 2023, the realization gap was 4.04 Mt year−1 globally and 0.81 Mt year−1 for the EU, and rose to 6.92 Mt year−1 and 1.66 Mt year−1 in 2024, globally and in the EU, respectively. This widening gap indicates that most of the SAF capacity planned to be operational by 2024 failed to materialize which highlights the challenges associated with turning announcement plans into operational capacity. We note that recently reported global SAF production volumes (~1 Mt year−1)12 reveal that even operating facilities produce at lower levels than their installed capacity. Furthermore, inactive capacity (i.e., failed and paused projects) exceeds realized capacity through 2024, globally and in the EU. This is partly due to project delays, as only 24% (global) and 26% (EU) of the announced SAF production capacity for 2024 became operational on time (see Supplementary Fig. 1a,c). Delays and cancellations of SAF production projects stem from factors such as technical and operational challenges, high costs, lack of competitiveness, limited regulation, weak demand, and feedstock constraints, with the specific reasons differing by technology (see Supplementary Table 2). Fischer–Tropsch projects are impeded with technical and operational challenges, while HEFA projects are mainly constrained by feedstock availability and poor competitiveness under volatile market conditions. PtL projects, in turn, face delays due to immature technology and limited access to affordable green hydrogen and captured CO2 of the new global announced capacity for 2024, 45% is still in early or advanced stages of construction. Similar trends persist when examining the announced capacity by 2030,model with 84% of the announced capacity remaining under development, with approximately half in the early stages and 10% failed or paused (see Supplementary Fig. 1b,d). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect the realization gap will widen in the coming years.

Potential scale-up of future SAF capacity deployment

The adoption and diffusion of technologies like SAF depend heavily on mandates and incentives due to high initial costs and unequal market competition16. Research on technology diffusion highlights the role of both push factors (e.g., investments in human capital and funding) and pull factors (e.g., market demand stimulation through incentives, volume mandates)17,18. Stable government policies have shown to be effective for scaling up other renewable energy technologies such as wind and solar energy, by boosting market demand, supporting production, and improving investors’ confidence. In contrast, inconsistent policies can increase risks, reduce investments, and may escalate deployment costs19. Adoption of energy transition technologies faces uncertainty, influenced by socio-economic, technological, and institutional factors that make the diffusion process difficult to quantify20. Generally, diffusion is a three-phase process that is typically represented by S-curve models. An initial phase of high costs and slow growth21, an upscaling phase with learning effects, cost reductions, and market expansion22, and a saturation phase with slower growth due to technological, economic, and/or social limits23. Modeling technology diffusion is challenging due to limited data, uncertainty, and complex future dynamics24 and flawed forecasting methods based on arbitrary assumptions often yield unreliable results25. Recent research seeks to address these issues by defining a range of feasible technology growth pathways modeled using historically analogous data26,27, and applying probabilistic methods to account for uncertainty rather than relying on fixed scenarios28,29,30,31,32.

In this work, we integrate these approaches with the Global SAF capacity DB to define the future potential scale-up of SAF production capacity on both the global and EU scale. The range of feasible outcomes is modeled through uncertainties in three key parameters that influence market ramp-up and the technology diffusion function: the initial value of the ramp-up (initial capacity), the growth rate, and the saturation level. We use Global SAF Capacity DB data to inform the stochastic logistic technology diffusion model. The analysis begins in 2025 and defines a range of SAF production capacity potential scale-up to 2050. While the DB provides announced capacity data up to 2030, we base the initial capacity for the market ramp-up on the expected SAF capacity for 2025 and the derived historical realization rate. Future announcements of new projects with an expected operational timeline before 2030 may be made publicly available. Thus, using the current 2030 announcement data excludes future potential values, possibly introducing a negative bias in the initial capacity parameter)r. We note that using the announced 2025 capacity data as the initial value also carries uncertainty, as projects that are announced to become operational in 2025 may face delays (even those in advanced stages such as under construction, final investment decision, or front-end engineering design), as discerned in this work (Fig. 3). Conversely, projects expected for 2024 but still under construction may become operational in 2025. In addition, new announcements of projects starting operations in 2025 may be made publicly available in 2025 (i.e., co-processing of renewable feedstocks for SAF production at existing petroleum refineries). To account for these uncertainties, we construct a probability distribution for the initial capacity parameter in 2025 (details in “Methods”).

In addition to the initial capacity, the growth rate influences the future diffusion of technology. To account for growth-related uncertainty, we model SAF production capacity potential scale-up using historical analogs. While considering the emergence growth rate of crude oil refining would be an appropriate historical analog due to technology similarity, this is not an appropriate choice as a result of significantly different historical context in which oil refining diffused and, consequently, the relatively low growth rates during its emerging phase (see Supplementary Fig. 4). We consider the growth rates of biofuels (biogasoline and biodiesel) and ethanol as one historical analogy, representing emerging fuel technologies promoted to displace the use of fossil crude oil. Additionally, we use a second growth trajectory from solar and wind energy as a benchmark for the successful deployment of renewable energy technologies. Despite their technological differences from SAF, wind and solar energy are valuable proxies because they were developed to replace fossil fuels and benefited from substantial policy support, technological advancements, and cost reductions during commercialization19. The historic growth rates of these technologies are used to fully explore the range of potential SAF production capacity growth.

The final parameter defining the potential scale-up SAF production capacity is the market saturation, which we model using policy targets from ICAO and the EU SAF mandate. We assume a gradual SAF demand increase, following a linearly interpolated function between short- and long-term targets. Globally, we consider ICAO’s vision of 5% emissions reductions by 2030 (requiring 23 Mt year−1 of SAF)15 and complete jet fuel replacement with SAF in 2050, as outlined in the ICAO’s Long-Term Aspirational Goal (LTAG) scenarios, specifically the scenario which assumes complete fossil jet fuel replacement by SAF in 2050 under high jet fuel demand (see Table 2). Further details on scenario selection are provided in Methods. This approach assumes SAF diffusion is constrained by aviation fuel demand forecasts, linked to air traffic growth, and policy targets for SAF adoption. Sensitivity analyses are conducted for the other scenarios, LTAG’s F2–Low and F2–Medium (see Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6), which assume lower air traffic growth. For the EU, the demand function follows the ReFuelEU mandate, which requires SAF use at airports to increase from 2% in 2025 to 70% by 2050. This implies a SAF demand of 2.8 Mt year−1 by 2030 and 35.7 Mt year−1 by 2050 (see “Methods” for details)33. Beyond the demand magnitude, we consider the concept of demand anticipation34 as developed in ref. 32. This represents the years investors foresee SAF policy targets being met, influencing SAF capacity deployment. We assume a default anticipation period of one year. This means that in our model, the required capacity in the target year is aimed to be realized one year earlier, reflecting the need for the SAF industry to build in temporal contingency for meeting SAF policy targets and mandates. In addition, we explore alternative scenarios with demand anticipation set at zero and two years (see Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 10).

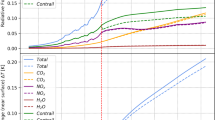

With the assumptions outlined above, two key findings emerge (see Fig. 4). First, neither growth trajectory, modeled following developments of similar energy products or successful energy technologies, achieves the short- or long-term targets set by ICAO. Even when following the more aggressive historical growth rates of wind and solar, the 95th percentile of the distribution of global SAF capacity falls below the targets. The median gap to the policy targets (i.e., the difference between the policy target and the distribution’s median) in 2030 amounts to 15.4 Mt for the biofuels and ethanol growth rates (Fig. 4a) and 9.5 Mt for the solar and wind growth rates (Fig. 4b). In 2030, following the growth rates of biofuels and ethanol, the median SAF production capacity is 7.4 Mt year−1 (68% below the target) with an interquartile range (IQR) of 6.5 –8.7 Mt year−1. With solar and wind growth rates, the median SAF production capacity reaches 13.5 Mt year−1 (42% lower than the target) with an IQR of 11.1–16.3 Mt year−1. In 2050, following the growth rates of biofuels and ethanol, the median SAF production capacity is 169 Mt year−1 (75% below the target) with an interquartile range (IQR) of 97–273 Mt year−1. With solar and wind growth rates, the median SAF production capacity reaches 634 Mt year−1 (7% below the target) with an IQR of 563–661 Mt year−1. The second key finding is that adopting successful technology growth rates, like those observed for the solar and wind industries, in the emergence phase could cause a substantial acceleration of scale-up. Under this scenario, capacity additions increase notably after 2039, in line with the linear demand function. This shift in growth does not happen by 2050 if the path follows biofuels and ethanol emergence growth rates. This differential illustrates the potential of employing accelerated adoption rates. The effect of demand anticipation is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7. More extended anticipation highlights the short- and long-term global SAF supply shortages when the distribution follows the growth rates experienced by biofuels and ethanol, whereas aligning growth paths experienced by wind and solar globally plays a role in achieving the long-term target.

The figure shows the potential global scale-up parametrized using historical biofuels and ethanol emergence growth rates (a) and, historical solar and wind growth rates (b). The colored area indicates the interval between 5th and 95th percentile. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) short term and long term SAF use targets are plotted for comparison. For the short term, the SAF capacity required to meet ICAO’s 5% emission reduction vision by 2030 is provided. In 2050, the fuel demand in 2050 as indicated in the long-term aspirational goal (LTAG) F2–High scenario is shown. The gap is calculated relative to the policy target rather than the demand function, since the aim of this study is to assess whether the installed capacity is sufficient to achieve the targets set by policymakers.

Modeling the future deployment with ethanol and biofuels’ growth rates shows that the EU SAF capacity will fall short of the targets set by the ReFuelEU mandate (Fig. 5). In 2030, the target gap is 1.21 Mt year−1 with the capacity IQR of 1.4–1.8 Mt year−1. By 2050, the target gap widens to 12.6 Mt year−1, which is 35% below the required production capacity to meet the EU SAF Mandate. If the regional growth rates experienced in the EU’s wind and solar energy sectors are followed, then the gap with both the short-term and long-term targets is reduced. Under this scenario, the median capacity shortfall reduces to 0.52 Mt in 2030 with the 90th percentile of distributions reaching the EU SAF mandate target of 2.8 Mt year−1. By 2050, while the 95th percentile approaches the target reaching 35.2 Mt year−1, the median EU SAF capacity remains at 33.9 Mt year−1, 5% below the target (IQR of 31.1–34.8 Mt year−1). We note that, in the EU, after 2034 the SAF capacity distribution shifts towards higher capacity additions, aligning more closely with the linear demand growth. By 2050 the difference between the median and 95th percentile narrows to only 1.3 Mt year−1, suggesting a higher probability of closing the gap with the policy target if the EU SAF production capacity follows the regional growth paths of solar and wind energy. Moreover, anticipating the demand by two years (see Supplementary Fig. 10) raises the median capacity to 34.6 Mt year−1 (IQR is 32.3–35.3 Mt year−1), reducing the gap to only 3% below the SAF production capacity needed to meet the EU SAF mandate in 2050.

The figure shows the potential scale-up in the EU parametrized using historical biofuels and ethanol (a), and historical solar and wind growth rates (b). The colored area indicates the interval between 5th and 95th percentile. The EU SAF mandate in 2030 and 2050 are also plotted for comparison. The gap is calculated relative to the policy target rather than the demand function, since the aim of this study is to assess whether the installed capacity is sufficient to achieve the targets set by policymakers.

Discussion

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) are widely recognized as a solution for reducing aviation-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and diversifying aviation energy sources. However, significant debate surrounds the pace and scale of the SAF market ramp-up, contributing to uncertainties about the potential to meet climate targets. To address this, we developed the Global SAF Capacity DB, which revealed a sharp increase in SAF production capacity announcements in recent years. Yet, by 2024, only 24% of the announced capacity was realized on time. Our findings show that project failures and delays outnumber successful completions, with most projects experiencing delays. This has led to a growing realization gap between announced and operational capacity, reaching 4.04 Mt year−1 by 2023 and rising to 6.92 Mt year−1 by 2024 globally.

Using a stochastic diffusion model, we further quantified the future SAF capacity potential scale-up globally and in the EU. The model draws on the growth rates of historical analogs, with similar technology features as SAF (biofuels and ethanol), and fast-growing energy transition technologies (wind and solar energy). Our findings highlight challenges in scaling global SAF production capacity to meet both the global and EU targets. Relying on biofuels and ethanol growth trajectory alone is not sufficient to meet the SAF targets globally or in the EU. At a global level, even if SAF follows the faster historical growth patterns of wind and solar energy, production will fall short of achieving short-term targets and is likely to miss the long-term 2050 goal. This is mainly because high growth rates take years to translate into high annual capacity additions. In this respect, the results indicate that the critical shifts for annual capacity additions to align with demand would likely occur around the late 2030s if SAF deployment follows solar and wind growth rates. Based on this analysis, to reach the 2050 target, global SAF capacity would need to grow at an average compounded rate of 23% per year from 2025 to 2050. For comparison, this is equivalent to the annual global growth rate of nuclear energy capacity between 1960 and 198635, when nuclear power underwent a major worldwide expansion. However, in the EU context, if the more rapid regional growth of wind and solar power is followed, the gap to policy targets could be narrowed as the shifts towards higher capacity additions aligned with the demand is projected to occur in the mid-2030s. Policy-driven sustained demand could be a determinant for achieving SAF adoption targets. Anticipating demand ahead and following wind and solar energy growth patterns increases the likelihood of reducing the gap with the policy targets.

Our results highlight that by 2030, global SAF deployment will fall short of policy targets. In the long term, the feasibility of SAF production in achieving targets will depend on achievable growth rates. Meeting the targets in 2050 will require SAF capacity to expand faster than solar and wind. However, achieving such growth may face additional barriers, including future feedstock availability and substantial capital investments. Feedstock availability will depend on factors such as land use changes for bioenergy, agricultural yields, productivity, waste recovery advancements, and conversion efficiency. While bioenergy and biofuel feedstock supply is expected to grow over the coming decades, the scale of this growth remains uncertain36. Meeting the ICAO target of entirely replacing fossil-based jet fuel by 2050, equivalent to producing 685 Mt year−1 of SAF (~29.5 EJ), necessitates significant feedstock resources. Existing estimates highlight the challenge of biomass availability for hard-to-decarbonize transportation sectors37,38,39. As a result, SAF will need to compete with other sectors such as heavy-duty road transportation and maritime shipping to access limited biomass resources. This suggests that, beyond the challenge of rapidly scaling-up production capacity, SAF adoption will also be constrained by the availability of bio-based feedstocks. From both policy and ecological perspectives, crop waste and residues are the most favorable bioenergy sources, but recent estimates place their primary potential at around 52 EJ year−1 in 205039, consistent with the upper range reported in the IPCC AR638. This makes it challenging to meet the energy needs of hard-to-decarbonize transportation sectors. A complementary strategy to increase feedstock availability involves the large-scale commercialization of PtL technologies. However, challenges remain, including technological readiness, high production costs, the need for large quantities of low-carbon electricity and hydrogen, and availability of CO2 sources. Recent project cancellations or delays and low realization rates for synthetic fuels and renewable hydrogen production are the result of these challenges40,41,42,43. Reaching the necessary SAF production capacity will require substantial capital expenditures (CAPEX). Using ICAO cost estimates44, cumulative global CAPEX is estimated at approximately 1.43 US$ trillion by 2050. If SAF deployment follows the growth trajectories of solar and wind energy, peak annual CAPEX could reach $101 billion (see Supplementary Fig. 11). Previous research suggests that achieving a 50% reduction in aviation emissions will require robust policies and price incentives, with SAF prioritized over other energy or fuel uses for bio-based feedstocks37.

The uncertainties regarding the short-term deployment and the achievable growth rates for SAF pose a risk of a long-term supply-demand mismatch. We highlight two key policy takeaways to mitigate these risks and support the scale-up of SAF capacity. First, low realization rates suggest that relying only on company announcement plans to project future SAF production is unreliable. Industry players may announce SAF production projects for strategic reasons, such as gaining investor and policymaker interest to secure investments or policy support. Our analysis of projects slated to become operational by 2030 reveals that approximately 10% have failed or been paused, while over 40% remain in the early development stages. The continued lack of competitiveness for SAF increases the likelihood of seeing the realization gap widen further in the following years, posing a threat to reaching the short-term aviation emission reduction targets by 2030. Therefore, policymakers should address the barriers that limit SAF scale-up. Second, the uncertainty surrounding SAF plans may discourage investments in capacity additions, as investors might prefer to postpone the efforts until production costs decrease and technology improvements are realized. As a result, the availability of SAF risks being outpaced by jet fuel demand, forcing the aviation sector to continue relying on fossil-based jet fuel. Policymakers could mitigate these risks and stimulate a large supply of SAF by fostering high growth rates, learning from the experience of solar and wind energy growth. Private investment has been crucial in the successful solar and wind energy worldwide capacity growth, especially in later development stages. However, in the emergence growth phase, these technologies frequently relied on government-supported mechanisms outside typical market frameworks, such as feed-in tariffs or long-term contracts19. Adopting strategies from successful energy transition technologies could enhance long-term outcomes and increase the likelihood of meeting aviation’s emission reduction targets.

We close by noting the limitations of this work. First, the Global SAF Capacity DB does not include announcements of SAF production facilities that were not made public at the time of writing. This may have introduced negative biases to the estimation of SAF capacity and the definition of the initial capacity for the diffusion model. However, this likely affects a limited capacity volume from bio-based feedstock co-processing at existing petroleum refineries. Second, the modeled future SAF capacity deployment is dependent on a growing demand pull based on airline operators’ financial ability to uplift SAF. Future research could identify the appropriate measures to sustain the demand in the long term.

Methods

Global sustainable aviation fuel capacity database

The analysis in this work is based on global sustainable aviation fuel projects compiled from public announcements between 2013 and 2024. At the end of 2024, the database contained 425 projects. Each announcement details companies producing or planning to produce sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) and co-products by 2030. 101 of the total announcements do not contain data regarding production capacity volumes or expected entry year and are therefore excluded from this analysis. Each announcement contains information on the SAF project, including the controlling company and applicable partners, location, SAF conversion technology, expected operational start date, announced fuel distillate capacity (SAF and co-products), and development status. For each announcement, an initial public web link is dated to when the announcement was first made, and more web links for updates to the initial announcements are documented.

Each announcement was assigned one of nine status categories. Of these, six categories pertain to active announcements (i.e., announcements of planned facilities or operational facilities), including operational, under construction, final investment decision (FID), front-end engineering design (FEED), feasibility, and concept. The remaining three categories apply to inactive announcements (i.e., announcements that have been closed or are not proceeding), including paused (projects that were announced but are currently idle and may become active again in the future), no update (projects for which no public announcements have been made after 2021, or company is without a functioning website that were expected to be operational by 2024) and failed (projects that were publicly canceled or bankruptcy of the lead company).

Since SAF production outputs also results in co-products (e.g., renewable diesel, naphtha, etc.), the announcements provided vary in detail on products’ specific volumes. Some announcements specify the volume of each product, including SAF capacity volumes. However, many announcements only state the total fuel output. For these announcements, the total fuel output (SAF and co-products) is adjusted using a range of possible SAF ratios to estimate the SAF production capacity. This range includes a minimum and maximum SAF ratio derived from literature sources based on the conversion technologies. Supplementary Table 1 provides the low and high SAF ratios assumed. Adjusting the total distillate capacity using the low and high ratio defines a range of SAF capacity values employed in this analysis. However, the low and high ratios are not employed when the SAF volume is explicitly stated, in this case, the SAF-specific production volume data is used.

Modeling approach for defining the potential scale-up of future sustainable aviation fuel capacity

The technology diffusion pattern is characterized by slow initial growth followed by exponential growth before reaching the market, saturation, which can be described by an S-shaped curve and a logistic function from45. Three parameters determine the standard logistic function (1), the initial value of the projections, the growth rate, and the saturation or asymptote46:

Where C(t) = capacity in year t, S = asymptote or market saturation, k = growth constant, \({{{{\rm{t}}}}}_{0}\) = inflection point.

Here, we conduct an uncertainty analysis of global SAF capacity growth by considering the uncertainties of these three parameters. For this purpose, we use the Global SAF Capacity DB data to model and adapt a stochastic logistic technology diffusion model26,32. The standard formulation of the logistic function in (1) becomes:

The model accounts for uncertainties of two key parameters: the initial capacity of the projections and the annual growth rate. We employ Monte Carlo sampling (N = 50,000) for both parameters. The modeled uncertainty around these parameters and the definition of the asymptote are described below. Among the available diffusion models, such as, for example, Bass, Gompertz, and Sharif-Kabir growth models, the adapted logistic function is selected for this study due to its balance of simplicity, flexibility, and its ability to capture both the initial slow uptake and the saturation of technology deployment. This differs from linear models, which fail to account for market saturation, and more complex models (e.g., Bass and Sharif-Kabir models), which require additional parameter assumptions about market interactions47. The adapted logistic function employed in this work provides a compromise between the symmetric standard logistic curve and the asymmetric Gompertz function32. This ensures that the diffusion approaches more gradually the demand function while considering an early-stage lower adoption, making it well-suited for modeling potential SAF production scale-up under uncertainty.

Initial capacity

We use a truncated normal distribution to represent the initial SAF capacity in 2025. The lower truncation (lower bound) is set as the operational SAF capacity in 2024. This capacity ranges between a low and high value based on the SAF ratio (see Supplementary Table 1), with an average value shown in Fig. 3. The upper truncation (upper bound) is defined by the total SAF capacity of projects expected to be operational by the end of 2025, using the high SAF ratio. This upper bound represents the maximum potential capacity if all active announcements come online as planned. The mean and standard deviation of the distribution are calculated by imposing two conditions. The first condition is that the expected value of the truncated distribution is set to match the capacity corresponding to a 24% realization rate of the globally announced SAF capacity expected to be operational by 2025 (26% for the European Union). This ratio is derived from the Global SAF Capacity DB analysis, the realization gap, and the SAF projects’ development status (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The assumption is that the SAF capacity realization rate in 2025 will remain consistent with its historical average of 24% globally and 26% within the EU. This can be expressed more formally as shown in (3):

Where ∅ = probability density function of the normal distribution and \(\Phi\) = cumulative density function of the normal distribution. (3) applies to both the global and EU, with the realization rates equal to 24% and 26%, respectively.

For the second condition, we compute the cumulative probability that the 2025 SAF capacity is equal to or less than the sum of the current operational capacity and the additional announced 2025 capacity. This includes projects currently under construction and projects that have completed FID. This cumulative probability is equal to 1, and it is used to set the second condition, as in (4):

Where

(4) refers to the global context, but for the EU context is adapted by considering the EU-specific capacity data. The mean and standard deviation of the truncated normal distribution are derived by solving these nonlinear Eqs. (3) and (4).

Growth rate

Similar to the approach for defining the initial capacity in 2025, we construct a truncated normal probability distribution to model the uncertainty of the growth rate. Two distributions are created, one global and the other for the EU, each reflecting the historical growth rates of biofuels and ethanol and solar and wind energy in the emerging growth phase.

We source historical data on biofuels production (biodiesel and biogasoline) and wind and solar energy installed capacity from the Statistical Review of World Energy 2024 released by the Energy Institute48. For ethanol, we use the Historical Adoption of TeCHnology (HATCH) Dataset, which provides time-series data on technology adoption for various technologies, including annual ethanol production35,49. While biofuels, wind, and solar data are available at both global and EU levels, ethanol data is only available globally. Therefore, we use global ethanol annual production data to build the truncated distributions for global and EU cases. To derive growth rates, we fit exponential models to the historical data of 1) biofuels and ethanol and, 2) solar and wind using sliding five-year intervals and then compute growth rates for each interval. Then, we consider only the periods of fastest growth to construct the truncated normal distributions (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). For each distribution, the lower truncation (lower bound) and upper truncation (upper bound) (3) are determined by the minimum and maximum growth rates observed in historical data for biofuels and ethanol, as well as wind and solar capacity. Table 3 summarizes the key parameters of the truncated normal distributions for both the initial capacity in 2025 and the emergence growth rates. Supplementary Fig. 4 illustrates each technology’s growth rate’s probability distributions.

Market saturation and demand function

The final parameter to define the logistic probabilistic model is market saturation. Globally, we assume the targets adopted by ICAO of 5% emissions reductions by 2030 and the full replacement of jet fuel demand by SAF in 2050, as outlined in the ICAO’s Long-Term Aspirational Goal (LTAG) scenarios. For 2030, ICAO reports that the 5% emission reduction translates into approximately 23 million tonnes (Mt) of SAF required annually to meet the target15. Considering a jet fuel demand of approximately 345 Mt year−1 9 provided in the ICAO LTAG mid-traffic scenario, this value thus assumes an average SAF carbon intensity of 22.3 gCO2eq. MJ−1.

For the mid- and long term, LTAG includes nine scenarios, reflecting three fuel consumption mixes (F1, F2, F3) and three levels of future jet fuel demand based on projected air traffic (Low, Medium, High)9. It is important to note that the LTAG fuel scenarios account for emissions reductions from both flight operations and aircraft technology improvements. F1 represents the most conservative scenarios, assuming that alternative fuels will not replace fossil-based jet fuel by 2050. F3 represents the most optimistic scenarios, where fossil-based jet fuel is fully replaced by alternative fuels before 2050. F2 assumes a complete replacement of jet fuel demand by alternative fuels in 2050. In this work, we focus on the F2 scenarios. Once the most appropriate fuel scenarios are identified, we select the most suitable air traffic forecast. For this purpose, we compare the projected jet fuel demand for 2024 in the F2 low, medium, and high scenarios and the actual jet fuel demand in 2024. Demand has rebounded to pre-COVID levels to approximately 8 million barrels per day (or 351 Mt year−1), following a sharp decrease in recent years. This value is closest to the jet fuel demand provided in the High traffic LTAG scenarios (equal to 339 Mt year−1), so we select F2–High as the baseline scenario. This provides the demand for jet fuel in the long term (2050). However, we also consider the Low and Medium scenarios, calculating the future SAF production capacity potential scale-up by including F2-Low and F2–Medium (see Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6). For the EU, the demand function is defined by the ReFuelEU mandate of SAF use at airports by 2050. The European Commission has adopted a SAF blending mandate for fuel supplied to EU airports, with minimum SAF shares gradually increasing from 2% in 2025 to 70% in 2050. The required jet fuel demand at EU airports in 2030 is estimated to range between 45.7 and 47.3 Mt year−1, depending on the extent of aircraft and engine technology advancements and air traffic management (ATM) improvements33. The mid-point estimate of 46.5 Mt year−1 corresponds to SAF demand of approximately 2.8 Mt year−1 by 2030 (Table 2). For 2050, the projected jet fuel demand range at EU airports increases from 43.8 to 58.0 Mt year−1 33. This implies a corresponding SAF demand between 30.7 and 40.6 Mt year−1. A mid-point value of 35.7 Mt year−1 is used for SAF demand in 2050, with sensitivity analyses conducted using the lower and upper bounds of the estimated range (see Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available in the GitHub repository https://github.com/almartll/Global-SAF-scale-up. Data from the Global SAF Capacity DB is also provided in the GitHub repository. Data on wind and solar power capacity is taken from the Statistical Review of World Energy 2024 released by the Energy Institute48. For ethanol, we use the Historical Adoption of TeCHnology (HATCH) Dataset, which provides time-series data on technology adoption for various technologies, including annual ethanol production35,49.

Code availability

The model code including all input data is available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/almartll/Global-SAF-scale-up50.

References

IEA. Aviation. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/aviation (2023).

Vardon, D. R., Sherbacow, B. J., Guan, K., Heyne, J. S. & Abdullah, Z. Realizing “net-zero-carbon” sustainable aviation fuel. Joule 6, 16–21 (2022).

Sharmina, M. et al. Decarbonising the critical sectors of aviation, shipping, road freight and industry to limit warming to 1.5–2 °C. Clim. Policy 21, 455–474 (2021).

Bergero, C. et al. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 404–414 (2023).

ATAG. Waypoint 2050. https://aviationbenefits.org/media/167417/w2050_v2021_27sept_full.pdf (2021).

IATA. Net Zero 2050: Sustainable Aviation Fuels. https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/pressroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-sustainable-aviation-fuels/ (2024).

Ueckerdt, F. et al. Potential and risks of hydrogen-based e-fuels in climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 384–393 (2021).

Chong, C. T. & Ng, J.-H. Limitations to sustainable renewable jet fuels production attributed to cost than energy-water-food resource availability. Nat. Commun. 14, 8156 (2023).

ICAO. Report on the Feasibility of a Long-term Aspirational Goal for International Civil Aviation CO2 Emission Reductions. https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/LTAG/Documents/REPORT%20ON%20THE%20FEASIBILITY%20OF%20A%20LONG-TERM%20ASPIRATIONAL%20GOAL_en.pdf (2022).

ICAO. ICAO Conference Delivers Strong Global Framework to Implement a Clean Energy Transition for International Aviation. https://www.icao.int/Newsroom/Pages/ICAO-Conference-delivers-strong-global-framework-to-implement-a-clean-energy-transition-for-international-aviation.aspx (2023).

European Commission. ReFuelEU Aviation. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-modes/air/environment/refueleu-aviation_en (2023).

IATA. Disappointingly Slow Growth in SAF Production. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2024-releases/2024-12-10-03/ (2024).

Dieterich, V., Buttler, A., Hanel, A., Spliethoff, H. & Fendt, S. Power-to-liquid via synthesis of methanol, DME or Fischer–Tropsch-fuels: a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 3207–3252 (2020).

Sky NRG. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Market Outlook. https://skynrg.com/skynrg-releases-sustainable-aviation-fuel-market-outlook-2024/ (2024).

ICAO. Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/pages/SAF.aspx (2024).

Narayanan, V. K. Managing Technology and Innovation for Competitive Advantage. (Pearson Education, 2001).

Mowery, D. & Rosenberg, N. The influence of market demand upon innovation: a critical review of some recent empirical studies. Res. Policy 8, 102–153 (1979).

Frosch, R. A. The customer for R&D Is always wrong!. Res. Technol. Manag. 39, 22–27 (1996).

Gallagher, K. S., Grübler, A., Kuhl, L., Nemet, G. & Wilson, C. The energy technology innovation system. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 37, 137–162 (2012).

Rao, K. U. & Kishore, V. V. N. A review of technology diffusion models with special reference to renewable energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14, 1070–1078 (2010).

Bento, N., Wilson, C. & Anadon, L. D. Time to get ready: Conceptualizing the temporal and spatial dynamics of formative phases for energy technologies. Energy Policy 119, 282–293 (2018).

Wilson, C. Up-scaling, formative phases, and learning in the historical diffusion of energy technologies. Energy Policy 50, 81–94 (2012).

Rogers, E. The Difussion of Innovations New York (Free Press, 1980).

Geels, F. W., Sovacool, B. K., Schwanen, T. & Sorrell, S. The socio-technical dynamics of low-carbon transitions. Joule 1, 463–479 (2017).

Baumgärtner, C. L., Way, R., Ives, M. C. & Farmer, J. D. The need for better statistical testing in data-driven energy technology modeling. Joule 8, 2453–2466 (2024).

Edwards, M. R. et al. Modeling direct air carbon capture and storage in a 1.5 °C climate future using historical analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2215679121 (2024).

Kazlou, T., Cherp, A. & Jewell, J. Feasible deployment of carbon capture and storage and the requirements of climate targets. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1047–1055 (2024).

Way, R., Ives, M. C., Mealy, P. & Farmer, J. D. Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition. Joule 6, 2057–2082 (2022).

Zielonka, N. & Trutnevyte, E. Probabilities of reaching required diffusion of granular energy technologies in European countries. iScience 28, 111825 (2025).

Zielonka, N., Wen, X. & Trutnevyte, E. Probabilistic projections of granular energy technology diffusion at subnational level. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad321 (2023).

Trutnevyte, E., Zielonka, N. & Wen, X. Crystal ball to foresee energy technology progress?. Joule 6, 1969–1970 (2022).

Odenweller, A., Ueckerdt, F., Nemet, G. F., Jensterle, M. & Luderer, G. Probabilistic feasibility space of scaling up green hydrogen supply. Nat. Energy 7, 854–865 (2022).

EASA. European Aviation Environmental Report. https://www.easa.europa.eu/eco/eaer (2025).

Nemet, G. F. Demand-pull, technology-push, and government-led incentives for non-incremental technical change. Res. Policy 38, 700–709 (2009).

Nemet, G., Greene, J., Zaiser, A. & Hammersmith, A. Historical Adoption of Technologies (HATCH) Dataset. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10231865 (2023).

Errera, M. R., Dias, T. A. D. C., Maya, D. M. Y. & Lora, E. E. S. Global bioenergy potentials projections for 2050. Biomass-. Bioenergy 170, 106721 (2023).

Staples, M. D., Malina, R., Suresh, P., Hileman, J. I. & Barrett, S. R. H. Aviation CO2 emissions reductions from the use of alternative jet fuels. Energy Policy 114, 342–354 (2018).

Chum, H. et al. Bioenergy. in IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation. (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Daehn, K., Coleman, E., Aoudi, L. & Allroggen, F. Global Bioenergy Availability. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/157942 (2025).

Kold, L. Arcadia Hit by Delay: Won’t be Able to Deliver Green Aviation Fuels Until 2028. https://energywatch.com/EnergyNews/Cleantech/article17501728.ece (2024).

Odenweller, A. & Ueckerdt, F. The green hydrogen ambition and implementation gap. Nat. Energy 10, 110–123 (2025).

Laity, E. Uniper and Sasol Cancel 200MW Hydrogen Project Amid Market Hurdles. https://www.h2-view.com/story/uniper-and-sasol-cancel-200mw-hydrogen-project-amid-market-hurdles/2115832.article/ (2024).

QCIntel. ST1 Pauses e-SAF Project with Vattenfall Citing Low Demand. https://www.qcintel.com/biofuels/article/st1-pauses-e-saf-project-with-vattenfall-citing-low-demand-34997.html (2025).

ICAO. SAF Rules of Thumb. https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Pages/SAF_RULESOFTHUMB.aspx.

Cherp, A., Vinichenko, V., Tosun, J., Gordon, J. A. & Jewell, J. National growth dynamics of wind and solar power compared to the growth required for global climate targets. Nat. Energy 6, 742–754 (2021).

Ang, B. W. & Ng, T. T. The use of growth curves in energy studies. Energy 17, 25–36 (1992).

Posch, M., Grubler, A. & Nakicenovic, N. Methods of Estimating S-shaped Growth Functions: Algorithms and Computer Programs (IIASA, 1988).

Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy 2024. https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (2024).

Nemet, G., Greene, J., Müller-Hansen, F. & Minx, J. C. Dataset on the adoption of historical technologies informs the scale-up of emerging carbon dioxide removal measures. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 397 (2023).

Martulli, A., Brandt, K., Allroggen, F. & Malina, R. The potential scale-up of sustainable aviation fuels production capacity to meet global and EU policy targets. Glob. SAF Scale- v1. 0. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17293416 (2025).

EASA. State of the EU SAF Market in 2023. https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/general-publications/state-eu-saf-market-2023 (2024).

Acknowledgements

A.M., F.A., and R.M. acknowledge funding for part of this research by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration through ASCENT, the FAA Center of Excellence for Alternative Jet Fuels and the Environment, project 01 through FAA Award Number 13C-AJFE-MIT under the supervision of Prem Lobo. KB acknowledge funding for part of this research by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration through ASCENT, the FAA Center of Excellence for Alternative Jet Fuels and the Environment, project 01 through FAA Award Number 13-C-AJFE-WaSU under the supervision of Prem Lobo. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the FAA. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr. Kristin C. Lewis for the contributions in providing SAF production announcements for the development of the Global SAF Capacity database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and R.M. jointly conceived and designed the study. A.M. implemented the model, performed the analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. K.B. contributed to data collection and assisted with manuscript editing and review. F.A. and R.M. contributed to manuscript editing and review. R.M. acquired the financial support for the project leading to this publication and supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mariam Ameen, and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martulli, A., Brandt, K., Allroggen, F. et al. The potential scale-up of sustainable aviation fuels production capacity to meet global and EU policy targets. Nat Commun 16, 11619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66686-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66686-9