Abstract

An efficient interface between a spin qubit and single photons is a key enabling system for quantum science and technology. We report on a coherently controlled diamond nitrogen-vacancy center electron spin qubit that is optically interfaced with an open microcavity. Through Purcell enhancement and an asymmetric cavity design, we achieve efficient collection of resonant photons, while on-chip microwave lines allow for spin qubit control at a 10 MHz Rabi frequency. With the microcavity tuned to resonance with the nitrogen-vacancy center’s optical transition, we use excited state lifetime measurements to determine a Purcell factor of 7.3 ± 1.6. Upon pulsed resonant excitation, we find a coherent photon detection probability of 0.5% per pulse. Although this result is limited by the finite excitation probability, it already presents an order of magnitude improvement over the solid immersion lens devices used in previous quantum network demonstrations. Furthermore, we use resonant optical pulses to initialize and read out the electron spin. By combining the efficient interface with spin qubit control, we generate two-qubit and three-qubit spin-photon states and measure heralded Z-basis correlations between the photonic time-bin qubits and the spin qubit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optically active solid-state qubits are promising physical systems for quantum networking1,2,3,4. Among several candidates5,6,7,8, the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond is one of the most-studied, with the realization of qubit teleportation9 across a multi-node quantum network10 and metropolitan-scale heralded entanglement11. Furthermore, efficient quantum frequency conversion to telecom wavelength12,13 and hybrid entanglement of photons and nuclear spins14,15 have been demonstrated. The NV center offers excellent spin qubit properties16 and the nitrogen nuclear spin17 together with nearby carbon-13 spins18 can function as a multi-qubit register19,20 to store21,22,23 and process24,25,26 quantum states with high fidelities27. The main challenges for the generation of spin-photon states with the NV center is the relatively low zero-phonon line (ZPL) emission of ~3%28 and the reduced optical coherence in the presence of charge noise hindering integration into nanophotonic devices29,30,31,32. State-of-the-art quantum network nodes9 are thus realized with solid immersion lenses (SIL)33, in which the NV center retains lifetime-limited optical linewidth34. In practice, such systems have shown ZPL detector click probabilities around 5 × 10−4 upon pulsed resonant excitation9,10,35,36.

In this work, we realize the integration of a NV center into a fiber-based Fabry-Pérot microcavity37,38 in combination with coherent microwave spin control, enabling the generation of spin-photon states. This platform features bulk-like optical coherence of the NV center by incorporating a micrometer-thin diamond membrane into the cavity39,40 and a Purcell-enhanced emission into the ZPL combined with an efficient photon extraction. We quantify the coupling of the NV center’s readout transition to the cavity modes with the Purcell factor by measuring the reduction of the excited state lifetime. Further, we investigate the cavity-coupled readout transition with a photoluminescence excitation (PLE) measurement to determine the optical linewidth, a Hanbury Brown and Twiss (HBT) experiment to verify single-photon emission, and a saturation measurement, which reveals a ZPL detector click probability that is an order of magnitude higher compared to standard solid immersion lens systems. Moreover, we demonstrate coherent control of the NV center’s electron spin and characterize its coherence properties in a Ramsey and a Hahn-Echo measurement. Finally, we use our platform to generate spin-photon states of the electron spin qubit with one and two time-bin encoded ZPL photon qubits. We herald on the photon detection in their time-bin states and observe the correlation with the corresponding spin qubit readout.

Results

Interfacing diamond nitrogen-vacancy center spin qubits with an optical microcavity

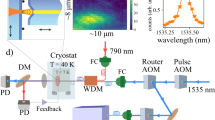

In this section, we conceptually outline the optical interfacing of NV centers which are coupled to a fiber-based Fabry-Pérot microcavity as schematically depicted in Fig. 1a. At its heart, a sample mirror with a bonded diamond membrane faces a laser-ablated spherical mirror on the tip of an optical fiber forming the microcavity38. Using the experimental setup presented in Fig. 1b, the cavity-coupled NV centers are optically addressed via the microcavity, which is mounted inside a closed-cycle optical cryostat. Details about the low-vibration cryogenic microcavity setup can be found in ref. 41, and the fabrication of the diamond device, which is also used in earlier work40, is reported in ref. 39.

a Schematic of the fiber-based Fabry-Pérot microcavity. The NV center is hosted in a diamond membrane bonded to a planar sample mirror that faces a spherical mirror on the tip of an optical fiber, forming the cavity. The cavity mirrors are dielectric Bragg mirrors. b Schematic experimental setup to efficiently interface a NV center qubit with an optical microcavity. The cavity-coupled NV center spin qubit is controlled with microwave signals, which are delivered via a gold stripline that is embedded into the sample mirror. Outside the cryostat, a permanent magnet is mounted to apply a static magnetic field to the qubit. The optical readout of the cavity-coupled NV center is achieved using free-space cross-polarized resonant excitation and detection using the horizontal (H) and vertical (V) polarization cavity mode via the sample mirror side. Additional lasers for charge repump, spin initialization, and cavity locking are deployed in fiber via the fiber mirror side. c Energy diagram showing the investigated Ex, Ey, E1 and E2 excited states of the cavity-coupled NV center with the spin qubit states ms = 0 and ms = − 1. The microwave qubit control, as well as the optical interface for readout and spin initialization, is depicted. The cavity is on resonance with the NV center Ey transition for readout.

For the experiments in this study, the two orthogonal, linear polarization modes of the microcavity must be considered. Due to birefringence in the diamond membrane, the frequency degeneracy of these cavity modes is lifted, which is identified as a polarization mode splitting in the optical cavity response. In our lab frame, the low frequency (LF) and high frequency (HF) cavity mode is referred to as horizontal and vertical polarization cavity modes, respectively. The NV center’s optical dipole of the readout transition around 637 nm couples to both polarization cavity modes, enabling resonant excitation and detection in a cross-polarized fashion42. Nanosecond-short optical excitation pulses are coupled into the vertical polarization cavity mode through the sample mirror via the reflection of a polarizing beamsplitter. Upon excitation, the NV center ZPL emission into the horizontal polarization cavity mode is coupled out through the sample mirror and detected by a fiber-coupled single-photon detector in transmission of the polarizing beamsplitter. This cross-polarization filtering reaches high suppression values of the excitation laser and is actively optimized during the experiments via piezo rotation mounted waveplates. In addition, a cavity lock laser at 637 nm is launched over the optical fiber mirror into the horizontal polarization cavity mode and is detected in cavity transmission by the same single-photon detector. This signal is used in the experiments to run a side-of-fringe lock that feeds back on the piezo that is controlling the fiber mirror position to maintain a constant cavity length. More details about the experimental setup and the methods to maintain a high excitation laser suppression and to lock the cavity are described in the Methods section.

To prepare the NV center in its negatively charged state an off-resonant 515 nm charge repump laser is deployed over the fiber mirror next to a second, 637 nm laser to initialize the NV center in its ms = 0 spin ground state via the E1 transition (see Fig. 1c). A permanent magnet outside the cryostat creates a static magnetic field at the position of the NV center, which Zeeman-splits the NV center’s ms = ± 1 spin states, allowing us to define a qubit subspace consisting of the ms = 0 and ms = −1 states. Microwave pulses for qubit control are delivered via a gold stripline, which is embedded into the sample mirror43.

All reported uncertainties in this work correspond to one standard deviation confidence intervals.

Coupling a single nitrogen-vacancy center to the microcavity

With the full spatial and spectral tunability of the microcavity44, we select a position on the diamond membrane that is close to the mirror-embedded gold stripline, exhibits a high cavity quality factor, and a well-coupled NV center. At the selected position, a frequency splitting between the horizontal and vertical polarization cavity mode of (9.56 ± 0.02) GHz is observed, which we attribute to birefringence due to the presence of strain in the diamond membrane. The individual cavity polarization mode shows a linewidth of (1.69 ± 0.02) GHz, which corresponds to a quality factor of 280 × 103. With the determined cavity geometry, a cavity mode volume of 86 λ3 is simulated. Accounting for our residual cavity vibration level of 22 pm, this results in a maximal vibration-averaged Purcell factor of 12 for a NV center that is perfectly coupled to a single cavity mode45. In addition, a cavity mode outcoupling efficiency through the sample mirror of 39% is calculated by taking the mirror coating transmission losses into account (see Supplementary Note 1 for the cavity characterization details).

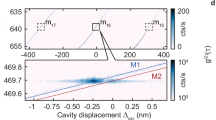

For the investigated cavity we find a NV center that is coupled with its Ey transition (readout transition) at a frequency of 470.377 THz (−23.34 GHz with respect to 470.4 THz). Figure 2a shows a PLE measurement of this transition in the LF cavity mode, resulting in a linewidth of (45 ± 3) MHz determined by a Gaussian fit. We attribute the additional broadening above the expected linewidth of 1/2πτP,LF ≈ 20 MHz for the Purcell-reduced lifetime τP,LF in the LF cavity mode as stated below to spectral diffusion. The determined transition linewidth is typical for NV centers with bulk-like optical properties, and the used experimental PLE sequence involving 515 nm repump laser pulses39. Furthermore, we find the NV center’s Ex transition at a frequency of 10 GHz. This corresponds to a transverse strain with Ex-Ey excited state splitting of ~33 GHz, which is larger compared to typical bulk samples. We note that we also find less strained NV centers in the diamond membrane (see Supplementary Note 9 for measurements of a second cavity-coupled NV center). Next to the NV center transitions associated with the ms = 0 spin state, we find emission lines at −26.0 GHz as well as −24.5 GHz that are associated with the ms = ± 1 spin states. We attribute these to the NV center’s E1 and E2 transitions, where we use the former as our spin initialization transition. In all measurements, a static magnetic field of about 37.5 G is present along the NV center crystal axis. See Supplementary Note 2 for the PLE measurements of the other transitions and details about the used sequences.

a PLE measurement of the NV center’s Ey transition (readout transition) in the LF cavity mode with a Gaussian fit (solid line) and a full width at half maximum (FWHM) linewidth. The background-corrected (bg-corr.) zero-phonon line (ZPL) counts are plotted over the excitation laser frequency with respect to (w.r.t.) 470.4 THz. Details about the PLE measurement sequence and the applied background correction are presented in Supplementary Note 2. b Pulsed resonant saturation measurement of the readout transition in the LF cavity mode, together with a linear fit as a guide for the eye. The probability (prob.) of a ZPL detector click is plotted over the laser pulse peak power. The inset shows the time-resolved detector counts for a laser pulse peak power of 35 μW measured free-space before the objective and the used integration window from 3 ns to 30 ns with respect to the excitation pulse center. The small peak at a detection time of about −5 ns is light of the excitation pulse that is backscattered into the free-space detection before reaching the cryostat. c Lifetime measurements of the NV center’s Ey excited state on cavity resonance in the LF and HF cavity modes, as well as off resonance in the LF mode. Details about the applied background correction are outlined in Supplementary Note 4. The fit windows of 5 ns to 18 ns are represented by the length of the solid lines of the monoexponential fits. The data is normalized (norm.) and offset for visual clarity. d Second-order correlation measurement of the readout transition in the LF cavity mode for a pulse train of 30 consecutive short resonant excitation pulses. In this measurement, the integration window of (b) is used. The triangular function capturing the finite pulse train (black dashed line) is shown next to the fit function that also includes the spin flipping process (black solid line).

In the sequences of all following measurements, we start by applying a 515 nm charge repump laser pulse to prepare the NV center with high probability in its negatively charged state, and a spin initialization laser pulse to initialize the NV center in its ms = 0 spin state (see Supplementary Note 6 for details). Figure 2c shows lifetime measurements of the NV center’s Ey excited state using 2 ns short resonant excitation pulses (see Supplementary Note 3 for details about the excitation pulse). The Purcell-reduced lifetime is measured in the LF and HF cavity modes with the cavity being on resonance with the readout transition. An off resonance lifetime is determined in the LF mode by detuning the cavity from the readout transition by −4 GHz. The lifetime measurement data is fitted with monoexponential curves. We observe that the data start to deviate from a monoexponential behavior for detection times ≳20 ns. We attribute this to signal of other (weaker coupled) NV centers or fluorescence of the cavity mirrors, and therefore restrict the fit window size. Details about the applied background subtraction and the influence of the fit window are further outlined in Supplementary Note 4. From the monoexponential fit, we determine an off resonance lifetime of τoff = (9.5 ± 0.4) ns and a Purcell-reduced lifetime of τP,LF = (7.8 ± 0.2) ns and τP,HF = (9.0 ± 0.2) ns for the LF and HF cavity mode, respectively. The off resonance lifetime differs from the expected excited state lifetime of 12.4 ns for low-strained NV centers34. We attribute this to strain-induced mixing in the excited states46,47. In Supplementary Note 4, we show a complementary investigation of this mechanism with time-resolved detection during continuous wave resonant excitation. The determined lifetimes allow to calculate the Purcell factor

with the NV center Debye-Waller factor β0 = 0.0328. The Purcell factors for the LF and HF cavity mode are FP,LF = 7.3 ± 1.6 and FP,HF = 2.0 ± 1.4. In all the following measurements, we use the stronger coupling to the LF cavity mode to enhance the NV center emission and the HF cavity mode for excitation. Based on the determined Purcell factor the NV center coherently emits βLF = β0FP,LF/(β0FP,LF + 1) ≈ 18% into the LF cavity mode, which corresponds to a cavity outcoupled ZPL emission of about 7% and a maximal detector click probability of about 1.4% per excitation pulse for our setup efficiency and detection time window (see Supplementary Note 10 for details).

In Fig. 2b, the saturation behavior of the NV center readout transition is studied. For that, the peak power of the short excitation laser pulse is varied, and the ZPL detector click probability after the first excitation pulse is measured. A ZPL detector click probability of 0.5% per pulse is determined for the highest power applied, which outperforms the standard NV center quantum network node setups based on solid immersion lenses by an order of magnitude9,10,35,36. In addition, the detector click probability still increases in a linear fashion for the investigated laser power regime showing that higher detector click probabilities can be reached if more laser power is applied. In the experiments, we are limited to the investigated laser power regime due to the efficiency of our short optical laser pulse generation setup.

Furthermore, we confirm single-photon emission by performing a pulsed resonant HBT experiment on the readout transition. In the experiment, we perform in total 55 × 106 measurement sequence repetitions in which we apply a train of short excitation pulses with a consecutive time separation of 126 ns. Figure 2d shows the second-order correlation function for 30 consecutive excitation pulses. The second-order correlation function exhibits clear antibunching at zero pulse number difference. Further, it shows two bunching-like features, which we attribute to the spin flipping probability into the ms = ± 1 states for larger pulse number differences and the probability to decay back into the ms = 0 state from the intersystem crossing singlet state for small pulse number differences. We fit the data with a triangular function as expected for the finite pulse train multiplied by a monoexponential function capturing the spin flipping process (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). The exponential decay for small pulse number differences is not included, since the amount of affected data points is insufficient for a reliable fit. We quantify an antibunching value of g(2)(0) = 0.034 ± 0.005 by the ratio of measured coincidences in the zero bin to the triangular fit amplitude.

Coherent microwave control of the nitrogen-vacancy center spin qubit

The NV center electron spin is coherently manipulated with microwave pulses, which are delivered via an about 10 μm distant gold stripline. Before microwave spin manipulation a 515 nm charge repump laser pulse prepares the NV center with high probability in its negatively charged state and the spin is optically initialized in its ms = 0 ground state with a spin initialization laser pulse and a fidelity of (93.5 ± 0.9)% (see Supplementary Note 6 for details about the initialization and qubit readout analysis). The applied magnetic field along the NV center crystal axis splits the ms = ± 1 states by about 210 MHz, enabling selective driving of the ms = 0 and ms = − 1 qubit subsystem. After spin manipulation, the qubit is read out via the readout transition using the short excitation pulses and the same integration window as introduced in Fig. 2b. Figure 3a shows the statistics of detected photons for our spin qubit readout after spin initialization in the ms = ± 1 or ms = 0 state. This measurement is used as a readout fidelity calibration, and its dependency on the number of used short readout pulses is presented in the inset. The average fidelity Favg of the ms = ± 1 readout fidelity F±1 and the ms = 0 readout fidelity F0 plateaus for larger readout pulse numbers and is optimal around 200 pulses, which is used in the following experiments. These readout fidelities are used for qubit readout correction, where the finite ms = 0 spin state initialization fidelity is also taken into account. We note that the average readout fidelity is not limited by laser power, but rather the average number of emitted photons before the studied NV center spin flips. The outcoupled ZPL emission of about 7% for our system is comparable to the collected non-coherent phonon sideband (PSB) emission used for readout in a SIL setup, rendering high-fidelity qubit readout possible48.

a Statistics of detected photons for our spin qubit readout after spin initialization in the ms = ± 1 or ms = 0 state. The inset presents the corresponding readout fidelities depending on the number of short excitation pulses used. For the experiments, 200 short readout pulses are used, which leads to fidelities of F±1 = 98.4%, F0 = 10.3% and Favg = 54.4% for the shown calibration with 500 × 103 repetitions. b Coherent Rabi oscillations with a fit (solid line) showing a Rabi frequency of Ω = (10.73 ± 0.02) MHz. The error bars are within the dot size. c Ramsey measurement with an artificial detuning of 50 MHz. The inset shows the used microwave pulse sequence, where a delay time-dependent phase is applied to the second pulse to generate the artificial detuning. The fit (solid line) captures a beating signature of (2.68 ± 0.05) MHz which is attributed to the coupled nitrogen nuclear spin and the free-induction decay of \({T}_{2}^{*}=(170\pm 20)\,{{{\rm{ns}}}}\) with an exponent of n = 1.0 ± 0.2. The error bars are within the dot size. d Hahn-Echo measurement with its microwave pulse sequence in the inset. The gray solid line is a guide for the eye of a Gaussian decay curve with an amplitude of 0.9 and a decay time of 180 μs. The error bars are within the dot size.

In Fig. 3b, coherent Rabi oscillations with a Rabi frequency of Ω = (10.73 ± 0.02) MHz are shown for our spin qubit at a microwave frequency of 2.773 GHz. Based on the fitted contrast of the Rabi oscillations and correcting for the finite ms = 0 spin state initialization fidelity, a microwave π pulse fidelity of (83 ± 9)% is extracted.

For the next experiments, a π pulse and a π/2 pulse are calibrated by varying the amplitude of five consecutively applied π pulses that minimize the probability to readout ms = 0. The π pulse duration is fixed to 64 ns, and half of that duration is used for the π/2 pulse. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the qubit coherence is probed in a Ramsey experiment with an artificial detuning of 50 MHz by applying a delay time-dependent phase shift to the second π/2 pulse. The observed beating signature is attributed to the hyperfine coupling of the nitrogen nuclear spin, which is included in the fit model (see Supplementary Note 7 for details). By fitting the measurement data, a free-induction decay time of \({T}_{2}^{*}=(170\pm 20)\,{{{\rm{ns}}}}\) is determined, which is short compared to typical \({T}_{2}^{*}\) times for these diamond devices (see Supplementary Note 9 for data of a second cavity-coupled NV center).

Using a Hahn-Echo experiment as presented in Fig. 3d, the qubit coherence can be largely recovered by choosing an appropriate total delay time τ, which mitigates quasi-static magnetic field fluctuations. In this measurement, three revivals are observed and a Gaussian decay curve with a time constant of 180 μs is displayed as a guide for the eye in Fig. 3d. The revivals occur around decoupling interpulse delay times τ/2 that correspond to integer multiples of the bare Larmor period of the carbon-13 nuclear spin bath of about 25 μs (γC13 = 1.0705 kHz/G and B = 37.5 G)49.

Generation of spin-photon states

In this section, we use our system to generate two-qubit and three-qubit spin-photon states and measure heralded correlations between the photonic and spin states. Figure 4a depicts the used pulse sequence, which combines spin qubit microwave control with the short resonant excitation pulses to generate spin-dependent photonic time-bin qubits. After optical initialization, the spin qubit is brought into equal superposition with a π/2 microwave pulse, followed by two resonant excitation pulses with an intermediate microwave π pulse. This generates the Bell state \(\left\vert {{{\rm{NV}}}}\,{{{\rm{spin}}}},{{{\rm{photon}}}}\right\rangle=(\left\vert 1,{{{\rm{E}}}}\right\rangle+\left\vert 0,{{{\rm{L}}}}\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) between the spin qubit states ms = 0 (\(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\)) and ms = − 1 (\(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\)) and the photonic qubit in the time-bin basis of early (\(\left\vert {{{\rm{E}}}}\right\rangle\)) and late (\(\left\vert {{{\rm{L}}}}\right\rangle\)) as used for remote entanglement generation in quantum network demonstrations5,35,50. The generated photon is measured by a single-photon detector, which heralds an early or late detection event. The spin qubit is optically read out in its Z-basis by 200 short readout pulses. The qubit readout probabilities conditioned on a photon heralding event in the early or late time-bin are shown in Fig. 4b (see Supplementary Note 6 for details about the applied qubit readout correction and Supplementary Note 8 for an X-basis spin qubit readout). A photon detection event in the late time-bin heralds the qubit in its expected \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) state. For an early time-bin photon detection event, the spin is read out with a probability of 82% in its expected \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) state. We attribute the lower readout probability of the \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) state to our limited microwave π pulse fidelity and an imperfect pulse calibration. In the Bell state correlation measurement, we record 27143 photon heralding events in 5 × 106 attempts, which corresponds to a probability of 0.54% per attempt.

a Pulse sequence to generate spin-photon states involving microwave pulses (in purple) for qubit control and short excitation pulses (in red) to generate spin-dependent time-bin photons. In the experiments, a microwave decoupling interpulse delay time of τ/2 = 23568 ns is used. b Conditional probabilities of the spin qubit readout in the Z-basis states ms = 0 (\(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\)) and ms = − 1 (\(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\)) after successful heralding an early (\(\left\vert {{{\rm{E}}}}\right\rangle\)) or late (\(\left\vert {{{\rm{L}}}}\right\rangle\)) photon of the spin-photon Bell state. The error bars are within the black dot size. c Conditional probabilities of the spin qubit readout in the Z-basis after a successful double heralding event of the photonic state \(\left\vert {{{\rm{L}}}},{{{\rm{E}}}}\right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert {{{\rm{E}}}},{{{\rm{L}}}}\right\rangle\) of the spin-photon Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state. The error bars are within the black dot size.

Furthermore, the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state \(\left\vert {{{\rm{NV}}}}\,{{{\rm{spin}}}},{{{\rm{photon}}}},{{{\rm{photon}}}}\right\rangle=(\left\vert 0,{{{\rm{E}}}},{{{\rm{L}}}}\right\rangle+\left\vert 1,{{{\rm{L}}}},{{{\rm{E}}}}\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) can be generated by repeating the center sequence with the two short resonant excitation pulses before readout (see case N = 2 in Fig. 4a). The correlations after a successful double photon heralding event are displayed in Fig. 4c. After heralding a correct two photon state, the expected spin state is read out with similar probabilities as in the Bell state measurement. In total, we measure 5242 two photon heralding events in 220 × 106 attempts, which corresponds to a probability of 2.4 × 10−5 per attempt.

Discussion

We have equipped a coherent NV center spin qubit with an efficient spin-photon interface by coupling it to an open microcavity. Coherent qubit control is realized with microwave pulses, and qubit initialization as well as qubit readout are achieved with optical pulses in a cross-polarized resonant excitation and detection scheme. Moreover, we have demonstrated the quantum networking capabilities of our system by generating two-qubit and three-qubit spin-photon states and measuring heralded correlations between the photonic time-bin and the spin qubit states.

For the presented system, we project a saturation ZPL detector click probability of 1.4% per pulse, by improving the excitation efficiency without modifying the microcavity. Furthermore, improving the device quality to eliminate additional cavity losses suggests a ZPL detector click probability of about 5%, which corresponds to a cavity outcoupled ZPL emission of 26%. Moreover, the system can be further optimized by implementing a charge-resonant check procedure of the optical transitions to mitigate spectral diffusion, improving charge state and qubit initialization fidelities51, as well as microwave pulse shaping for high-fidelity qubit control27.

Our work opens up opportunities to explore quantum networking with Purcell-enhanced NV centers, promising remote entanglement generation with higher rates and fidelities. Furthermore, we expect that the here developed methods provide guidance for other solid-state qubits to realize efficient spin-photon interfaces based on microcavities for quantum network applications45,52,53,54,55.

Methods

Cryogenic cavity setup and microwave pulse delivery

We use a floating stage closed-cycle optical cryostat (Montana Instruments HILA) with a base temperature of about 6 K and a sample mirror holder temperature of about 8 K. The spherical fiber mirror, which faces the sample mirror, is made out of a single-mode optical fiber with a pure silica core and a polyimide protection coating (Coherent FUD-4519, S630-P) and is mounted on a cryo-compatible positioning stage (JPE CPSHR1-a). A room temperature objective (Zeiss LD EC Epiplan-Neofluar), which is thermally shielded, is used to optically interface the sample mirror side of the cavity. The objective is positioned with three linear nanopositioning stages (Physik Instrumente Q-545) in a tripod configuration. A permanent neodymium disc magnet (Supermagnete S-70-35-N), which is mounted on the lid of the cryostat, is used to create a static magnetic field at the position of the sample mirror. Further details about the cryogenic setup can be found in ref. 41.

The setup is operated with a computer and the Python-based software QMI version 0.4456. The data is stored and analyzed with the Python framework quantify-core. The actual measurement sequences are timed and executed by an interplay between a microcontroller (Jäger Computergesteuerte Messtechnik Adwin Pro II) and an arbitrary waveform generator (Tektronix AWG5014C). Microwave pulses are generated with a single sideband modulated vector signal generator (Rohde & Schwarz SMBV100A), amplified by a microwave amplifier (Mini-Circuits ZHL-50W-63+), and delivered to the cryostat via a home-built microwave switch. At the qubit frequency of 2.773 GHz we measure about 26 dB transmission loss through the cryostat. Further details about the microwave wiring and a picture of the sample mirror with mirror-embedded gold striplines can be found in ref. 41.

Laser pulse generation and delivery

We use one 637 nm continuous wave diode laser each for cavity locking (Newport Newfocus Velocity TLB-6300-LN) and spin initialization (Toptica DL Pro 637 nm). To modulate the laser intensity and generate microsecond-long optical pulses with high on/off ratios, two cascaded in-fiber acousto-optic modulators (AOM, Gooch and Housego Fiber-Q 633 nm) are used. Both lasers are combined free-space by a 50:50 non-polarizing beamsplitter (Thorlabs BS016). Then, a Glan-Taylor polarizer (Thorlabs GT10-A) and a half-wave and quarter-wave plate (Thorlabs WPH05M-633 and WPQ05M-633) are used to set and control the polarization. Finally, the 637 nm lasers are overlapped with the 515 nm repump laser (Hübner Photonics Cobolt 06-MLD) by a dichroic mirror (Semrock Di01-R532) and coupled into a single-mode fiber, which is connected to the cavity fiber.

A frequency-doubled, high-power tunable diode laser (Toptica TA-SHG Pro 637 nm) is used for readout as well as for cross-polarization control. For that, the laser is split by a 50:50 fiber beamsplitter (Thorlabs PN635R5A2) into two in-fiber paths. In the path for cross-polarization control, two in-fiber AOMs are used for modulation, whereas in the readout laser path, a temperature-stabilized electro-optical amplitude modulator (EOM, Jenoptik AM635) is deployed additionally. This allows for faster intensity modulation and the generation of nanosecond-short resonant excitation pulses. The EOM is DC biased by a programmable bench power supply (Tenma 72-13360) using a bias-tee (Mini-Circuits ZX85-12G-S+) and a DC block (Mini-Circuits BLK-89-S+) to control a constant transmission level. In addition, fast electrical pulses are generated with a home-built standalone pulse generator57 and applied to the EOM via the RF input of the bias-tee to generate nanosecond-short excitation pulses (see Supplementary Note 3 for their characterization). Finally, both in-fiber paths are combined with a 75:25 fiber beamsplitter (Thorlabs PN635R3A2) whose 75% output is connected to a polarization-maintaining fiber (Thorlabs P3-630PM-FC-2) before free-space launching. The 25% output is connected to a power meter (Thorlabs PM100USB with head S130VC) for laser power monitoring. To preserve a high polarization extinction ratio in both paths in-line fiber polarizers (Thorlabs ILP630PM-APC) are used.

All 637 nm lasers are stabilized on a wave meter (HighFinesse WS-U).

Free-space cross-polarization optics

The cavity is interfaced from the sample mirror side with free-space cross-polarization optics as depicted in Fig. 1b. The collimated beam leaving the cryostat chamber is guided by broadband dielectric mirrors (Thorlabs BB03-E03) on the optical table and is reflected off a dichroic mirror (Semrock Di02-R635) before reaching the polarization optics. Next, the beam passes through half-wave and quarter-wave plates (Thorlabs WPH05M-633 and WPQ05M-633), which are mounted in piezo rotation stages (Newport AG-PR100 controlled by Newport AG-UC8). These wave plates map the excitation and detection polarization of the polarizing beamsplitter cube (PBS, Thorlabs PBS202) to the cavity polarization modes.

In the excitation path of the PBS the readout laser is launched from the polarization-maintaining fiber into free-space (Thorlabs KT120 with objective RMS10X) and passes a Glan-Thompson polarizer (Thorlabs GTH10M-A), followed by a quarter-wave and half-wave plate, which are mounted in piezo rotation stages as well.

In the detection path of the PBS, the light is filtered by a Glan-Thompson polarizer (Thorlabs GTH10M-A), an angle-tunable etalon (Light Machinery custom coating, ≈ 100 GHz full width at half maximum (FWHM) at 637 nm), and a bandpass filter (Thorlabs FBH640-10). Finally, the light is coupled (Thorlabs KT120 with objective RMS10X) into a single-mode fiber (Thorlabs P3-630A-FC-2) and detected by a single-photon detector (Picoquant Tau-SPAD-20). For the HBT experiment shown in Fig. 2d, a 50:50 fiber beamsplitter (Thorlabs TW630R5A2) is added, and a second single-photon detector (Laser Components Count-10C-FC) is used. The detectors are connected to a single-photon counting module (Picoquant Hydraharp 400) and the counter module of the microcontroller. The gating of the single-photon detectors is used to protect them against blinding during the application of the spin initialization laser.

Microcavity operation

For the resonant cross-polarization excitation and detection scheme used in this work, it is essential to keep the cavity on resonance with the NV center and to maintain a high excitation laser suppression during the measurements. To ensure these operational conditions, we probe the cavity resonance as well as the excitation laser suppression interleaved with the experimental sequences and stream the data to a computer in real-time to run an optimization routine next to the measurement. In both cases, the probe laser light is detected with the ZPL single-photon detector and recorded with the counter module of the microcontroller. This technique allows for live feedback on the order of Hertz, which is sufficient to compensate for drifts of the cavity resonance and the cross-polarization filtering. With the methods outlined in the following, it is possible to run measurements remotely for days.

To keep the cavity on resonance with the readout transition of the NV center, a side-of-fringe lock is deployed. For that, the cavity lock laser is frequency-tuned to the fringe of the cavity mode, and the single-photon detector counts are recorded during interleaved 100 μs long probe laser pulses. The recorded counts are streamed to a computer that uses a proportional control loop programmed in Python to optimize on a specified set value. The proportional control loop feeds back on the piezo that is controlling the fiber mirror position and, by that, locks the cavity on resonance. The cavity lock laser power is adjusted such that a count rate of about 700 kHz is measured when the cavity is on resonance with the cavity lock laser. For every specified set value, the cavity lock laser frequency can be adjusted such that the cavity is on resonance with the NV center.

For the cross-polarization filtering, interleaved 10 nW probe pulses of the cross-polarization control laser are applied for 400 μs while recording the single-photon detector counts. These counts represent the current excitation laser suppression and are streamed to a computer that runs a hill climbing type algorithm programmed in Python. The algorithm makes iterative changes to the four piezo rotation mounted wave plates as introduced in Fig. 1b to minimize the recorded counts. With this polarization suppression control loop, typical long-term count rates are <2 kHz for 10 nW probe pulses, which corresponds to excitation laser suppression values >60 dB.

Data availability

The measurement data generated in this study have been deposited in the 4TU.ResearchData database under accession code https://doi.org/10.4121/6f8031ae-dd61-4b4f-adf4-d20bc88ed9ac58.

Code availability

Code that supports this manuscript is available on request.

References

Kimble, H. J. The quantum internet. Nature 453, 1023–1030 (2008).

Wehner, S., Elkouss, D. & Hanson, R. Quantum internet: a vision for the road ahead. Science 362, eaam9288 (2018).

Ruf, M., Wan, N. H., Choi, H., Englund, D. & Hanson, R. Quantum networks based on color centers in diamond. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 070901 (2021).

Janitz, E., Bhaskar, M. K. & Childress, L. Cavity quantum electrodynamics with color centers in diamond. Optica 7, 1232 (2020).

Bernien, H. et al. Heralded entanglement between solid-state qubits separated by three metres. Nature 497, 86–90 (2013).

Knaut, C. M. et al. Entanglement of nanophotonic quantum memory nodes in a telecom network. Nature 629, 573–578 (2024).

Ruskuc, A. et al. Multiplexed entanglement of multi-emitter quantum network nodes. Nature 639, 54–59 (2025).

Afzal, F. et al. Distributed Quantum Computing in Silicon. ArXiv:2406.01704 [quant-ph] (2024).

Hermans, S. L. N. et al. Qubit teleportation between non-neighbouring nodes in a quantum network. Nature 605, 663–668 (2022).

Pompili, M. et al. Realization of a multinode quantum network of remote solid-state qubits. Science 372, 259–264 (2021).

Stolk, A. J. et al. Metropolitan-scale heralded entanglement of solid-state qubits. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp6442 (2024).

Tchebotareva, A. et al. Entanglement between a diamond spin qubit and a photonic time-bin qubit at telecom wavelength. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 063601 (2019).

Geus, J. F. et al. Low-noise short-wavelength pumped frequency downconversion for quantum frequency converters. Opt. Quantum 2, 189 (2024).

Javadzade, J., Zahedian, M., Kaiser, F., Vorobyov, V. & Wrachtrup, J. Efficient nuclear spin-photon entanglement with optical routing. Phys. Rev. Appl. 24, 024059 (2025).

Chang, X.-Y. et al. Hybrid entanglement and bit-flip error correction in a scalable quantum network node. Nat. Phys. 21, 583–589 (2025).

Abobeih, M. H. et al. One-second coherence for a single electron spin coupled to a multi-qubit nuclear-spin environment. Nat. Commun. 9, 2552 (2018).

Van Der Sar, T. et al. Decoherence-protected quantum gates for a hybrid solid-state spin register. Nature 484, 82–86 (2012).

Childress, L. et al. Coherent dynamics of coupled electron and nuclear spin qubits in diamond. Science 314, 281–285 (2006).

Bradley, C. E. et al. A ten-qubit solid-state spin register with quantum memory up to one minute. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031045 (2019).

Van De Stolpe, G. L. et al. Mapping a 50-spin-qubit network through correlated sensing. Nat. Commun. 15, 2006 (2024).

Reiserer, A. et al. Robust quantum-network memory using decoherence-protected subspaces of nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021040 (2016).

Bradley, C. E. et al. Robust quantum-network memory based on spin qubits in isotopically engineered diamond. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 122 (2022).

Bartling, H. P. et al. Entanglement of spin-pair qubits with intrinsic dephasing times exceeding a minute. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011048 (2022).

Taminiau, T. H., Cramer, J., van der Sar, T., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal control and error correction in multi-qubit spin registers in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 171–176 (2014).

Kalb, N. et al. Entanglement distillation between solid-state quantum network nodes. Science 356, 928–932 (2017).

Abobeih, M. H. et al. Fault-tolerant operation of a logical qubit in a diamond quantum processor. Nature 606, 884–889 (2022).

Bartling, H. et al. Universal high-fidelity quantum gates for spin qubits in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 034052 (2025).

Riedel, D. et al. Deterministic enhancement of coherent photon generation from a nitrogen-vacancy center in ultrapure diamond. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031040 (2017).

Faraon, A., Santori, C., Huang, Z., Acosta, V. M. & Beausoleil, R. G. Coupling of nitrogen-vacancy centers to photonic crystal cavities in monocrystalline diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 033604 (2012).

Ishikawa, T. et al. Optical and spin coherence properties of nitrogen-vacancy centers placed in a 100 nm thick isotopically purified diamond layer. Nano Lett. 12, 2083–2087 (2012).

Lekavicius, I., Oo, T. & Wang, H. Diamond Lamb wave spin-mechanical resonators with optically coherent nitrogen vacancy centers. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 214301 (2019).

Jung, T. et al. Spin measurements of NV centers coupled to a photonic crystal cavity. APL Photonics 4, 120803 (2019).

Hadden, J. P. et al. Strongly enhanced photon collection from diamond defect centers under microfabricated integrated solid immersion lenses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 241901 (2010).

Hermans, S. L. N. et al. Entangling remote qubits using the single-photon protocol: an in-depth theoretical and experimental study. New J. Phys. 25, 013011 (2023).

Hensen, B. et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 526, 682–686 (2015).

Humphreys, P. C. et al. Deterministic delivery of remote entanglement on a quantum network. Nature 558, 268–273 (2018).

Vahala, K. J. Optical microcavities. Nature 424, 839–846 (2003).

Hunger, D. et al. A fiber Fabry-Perot cavity with high finesse. New J. Phys. 12, 065038 (2010).

Ruf, M. et al. Optically coherent nitrogen-vacancy centers in micrometer-thin etched diamond membranes. Nano Lett. 19, 3987–3992 (2019).

Ruf, M., Weaver, M., van Dam, S. & Hanson, R. Resonant excitation and Purcell enhancement of coherent nitrogen-vacancy centers coupled to a Fabry-Perot microcavity. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 024049 (2021).

Herrmann, Y. et al. A low-temperature tunable microcavity featuring high passive stability and microwave integration. AVS Quantum Sci. 6, 041401 (2024).

Yurgens, V. et al. Cavity-assisted resonance fluorescence from a nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 112 (2024).

Bogdanović, S. et al. Robust nano-fabrication of an integrated platform for spin control in a tunable microcavity. APL Photonics 2, 126101 (2017).

Bogdanović, S. et al. Design and low-temperature characterization of a tunable microcavity for diamond-based quantum networks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 171103 (2017).

Herrmann, Y. et al. Coherent coupling of a diamond tin-vacancy center to a tunable open microcavity. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041013 (2024).

Manson, N. B., Harrison, J. P. & Sellars, M. J. Nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond: model of the electronic structure and associated dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 74, 104303 (2006).

Goldman, M. L. et al. State-selective intersystem crossing in nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. B 91, 165201 (2015).

Robledo, L. et al. High-fidelity projective read-out of a solid-state spin quantum register. Nature 477, 574–578 (2011).

Ryan, C. A., Hodges, J. S. & Cory, D. G. Robust decoupling techniques to extend quantum coherence in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 200402 (2010).

Pfaff, W. et al. Unconditional quantum teleportation between distant solid-state quantum bits. Science 345, 532–535 (2014).

Brevoord, J. M. et al. Heralded initialization of charge state and optical-transition frequency of diamond tin-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 054047 (2024).

Bayer, G. et al. Optical driving, spin initialization and readout of single SiV- centers in a Fabry-Perot resonator. Commun. Phys. 6, 300 (2023).

Zifkin, R., Rodríguez Rosenblueth, C. D., Janitz, E., Fontana, Y. & Childress, L. Lifetime reduction of single germanium-vacancy centers in diamond via a tunable open microcavity. PRX Quantum 5, 030308 (2024).

Hessenauer, J. et al. Cavity enhancement of V2 centers in 4H-SiC with a fiber-based Fabry-Perot microcavity. Opt. Quantum 3, 175 (2025).

Ulanowski, A., Früh, J., Salamon, F., Holzäpfel, A. & Reiserer, A. Spectral multiplexing of rare-earth emitters in a co-doped crystalline membrane. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2302897 (2024).

Raa, I. T. et al. QMI - Quantum Measurement Infrastructure, a Python 3 framework for controlling laboratory equipment https://data.4tu.nl/datasets/6d39c6db-2f50-4a49-ad60-5bb08f40cb52 4TU.ResearchData (2023).

Vermeulen, R. F. L. Pulse generator and method for generating pulses https://research.tudelft.nl/en/publications/pulse-generator-and-method-for-generating-pulses Patent: OCT-20-006 Applicant: TU Delft (2020).

Fischer, J. et al. Data underlying the publication “Spin-Photon Correlations from a Purcell-enhanced Diamond Nitrogen-Vacancy Center Coupled to an Open Microcavity" https://doi.org/10.4121/6f8031ae-dd61-4b4f-adf4-d20bc88ed9ac 4TU.ResearchData (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Raymond Vermeulen for designing and building the standalone pulse generator used to modulate the electro-optical amplitude modulator. We thank Martin Eschen for laser-ablating the fiber mirror. We thank Jiwon Yun, Kai-Niklas Schymik, Conor Bradley, Alexander Stramma, and Mariagrazia Iuliano for helpful discussions. We thank Alexander Stramma for feedback on the manuscript. We acknowledge financial support from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) through the Spinoza prize 2019 (project number SPI 63-264) and from the EU Flagship on Quantum Technologies through the project Quantum Internet Alliance (EU Horizon 2020, grant agreement no. 820445).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F. and Y.H. contributed equally to this work. J.F. and Y.H. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. J.F., Y.H., and S.S. developed and built the cross-polarization filtering setup. J.F. developed the cavity lock and the polarization suppression control. J.F., Y.H., and C.F.J.W. developed and built the short optical laser pulse generation setup. J.F. and C.F.J.W. developed the microwave qubit control. S.S. characterized the cavity fiber. M.R. fabricated the diamond device. J.F., Y.H., and R.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. R.H. supervised the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, J., Herrmann, Y., Wolfs, C.F.J. et al. Spin-photon correlations from a Purcell-enhanced diamond nitrogen-vacancy center coupled to an open microcavity. Nat Commun 16, 11680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66722-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66722-8