Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are widely distributed persistent pollutants in water resources that pose serious environmental and health threats. Current per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance destruction strategies are energy-intensive, nonselective, and often generate recalcitrant short-chain fluorinated byproducts. Herein, we report a near-ultraviolet to visible light-driven complete defluorination approach of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance based on ligand-to-metal charge transfer, wherein commercially available Cu2+ salts serves as the electron acceptor from per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance to initiate the defluorination reaction. The feasibility of the degradation reaction is explored under controlled conditions, in which perfluorooctanoic acid is completely degraded and defluorinated within 300 min. Spectroscopic analyses, intermediates identification, and density functional theory calculations confirm that electron transfer from perfluorooctanoic acid to Cu2+ selectively initiates a single-pathway chain-shortening degradation mechanism. The degradation rate of perfluoroalkyl acids increases as chain length decreased. Ultrashort-chain trifluoroacetic acid achieves more than 99% degradation and defluorination within 60 min. This degradation approach is also effective for perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids and is potentially adaptable to a broader range of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance classes, offering opportunities for extension to other homogeneous or heterogeneous Cu2+-based remediation systems, as the reactivity pattern has been substantiated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been extensively utilized since the 1940s for the production of various industrial and consumer products, such as textiles, firefighting foams, pesticides, and paper products, owing to their unique physicochemical properties1,2. However, their widespread and prolonged use has raised significant environmental and public health concerns3. Among them, perfluoroalkyl acids (PFCA) such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and legacy alternatives, ether-containing PFAS such as hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA, commonly known as GenX), have been widely studied4 because of their widespread distribution, detection in rivers, groundwater, oceans, and even in drinking water5,6. Stable and high-energy C−F bonds ( ≈ 536 kJ/mol) contribute to the environmental persistence of these compounds, leading to their designation as “forever chemicals.”7 Prolonged exposure to even low concentrations of these compounds has been linked to severe health risks, including developmental disorders, immune system dysfunction, reproductive toxicity, and increased risk of cancer8,9,10. In response to these environmental and health concerns, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has proposed stringent limits of 4 ng/L for PFOA and 10 ng/L for GenX in drinking water11, thereby intensifying the demand for effective PFAS removal technologies.

Various promising technologies, including electrochemical12,13,14, advanced oxidation and reduction15, sonochemical16, and thermochemical17 treatments, have been investigated for degrading PFAS. However, these chemical techniques often fail to achieve highly efficient degradation and complete mineralization of PFAS in aqueous environments due to high energy requirements, the formation of refractory intermediates, and interference from complex matrices, which significantly limit their sustainability and practical applicability18. Currently, nondestructive technologies such as carbon adsorption, membrane filtration, and ion exchange systems are commonly used to remove PFAS from water19. Nevertheless, these physical removal methods generate concentrated PFAS organic waste solvents (e.g., dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methyl alcohol (MeOH), and acetonitrile (MeCN)) that require further treatment to prevent secondary pollution20. As a result, a key research focus is the treatment of high-concentration PFAS21,22. Recent advancements in reaction systems for the degradation of high-concentration PFAS include NaOH-mediated defluorination in DMSO at 120 °C23, electrochemical degradation in MeCN using Cu+ electrocatalysts with triazole-based ligands24, the reaction system of a super-reducing photocatalyst (KQGZ) at 60 °C in DMSO25, and multiphoton visible-light systems based on benzo[g,h,i]perylenemonoimide (BPI) that selectively cleave C–F bonds26. Despite achieving partial defluorination of PFAS, these reaction systems require elevated temperatures or complex, strongly reducing catalysts. There remains an urgent need for strategies that enable rapid and complete defluorination under mild conditions.

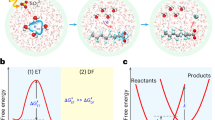

Photoredox methods have emerged as valuable tools for degrading PFAS27, utilizing photons as a clean and selective energy source to generate aggressive oxidative species (e.g., hydroxyl radicals (HO•) and holes (h+)) or reductive species (e.g., hydrated electrons (eaq−)) under mild conditions (Fig. 1a). However, these methods are hindered by uncontrolled degradation pathways and the generation of harmful byproducts (e.g., trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), fluorotelomer carboxylic acids (FTCA), and fluoromethane)13,28, which are relatively difficult to degrade, resulting in partial defluorination of PFAS. Recently, Nocera et al. 29. reported that TFA can be activated to generate trifluoromethyl radicals and react with a variety of arenes to form C(sp2)−CF3 bonds via the photoexcitation of Ag2+-centered complexes through a ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) process. Inspired by this work, we propose that a mild LMCT process can be employed for the degradation of PFAS. LMCT involves complexes of transition metals with an empty valence shell, wherein an electron from a high-energy ligand orbital is excited and transitioned into a low-lying metal-centered orbital, and it has shown promise as an effective approach for generating reactive intermediates from inert substrates30,31,32. Cu2+ is an ideal candidate for environmental applications because of its low cost, terrestrial abundance, and low toxicity33, and it can initiate photocatalysis reactions via single-electron transfer and directly interact with substrates in its coordination sphere34. Recent studies have also shown that LMCT activation enabled the formation of alkyl radicals from alkyl acids via near-UV excitation of Cu²⁺ carboxylates, followed by carbon dioxide (CO2) extrusion (Fig. 1b)35,36,37. For PFAS containing carboxyl groups, decarboxylation is often the critical step in the oxidative degradation process. Thus, Cu2+ has significant potential for PFAS degradation through the LMCT process under mild visible light, which avoids the challenges of uncontrolled reactive species-based methods (Fig. 1a).

This study investigated the complete degradation and defluorination of PFOA in a model system using a Cu2+-initiated photochemical approach under near-UV to visible light. Key experimental parameters, including light source, Cu2+ source, solvent, and PFOA concentration, were systematically evaluated. Both experimental and computational analyses were conducted to elucidate the LMCT-induced degradation mechanism, which aligned well with the identified degradation intermediates. Additionally, the photodegradation efficiencies of other legacy and novel PFAS, including PFCA with different chain lengths and ether-containing PFAS, were assessed under identical conditions. This comprehensive investigation provides valuable insights into the potential of Cu2+-initiated degradation as a promising strategy for PFAS treatment.

Results

Photochemical degradation of PFOA in the presence of Cu2+

We set out to develop a simple, low-energy, and highly effective photochemical method for efficient defluorination of PFAS by combining a commercially available copper salt with an affordable and efficient light source. We initially explored this model in the context of the degradation of PFOA, one of the most extensively detected PFAS38. A mixture of PFOA (1.0 equiv.), cupric trifluoromethane sulfonate (Cu[OTf]2; 2.0 equiv.), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH; 1.0 equiv.) in MeCN was exposed to a λmax = 365 nm light-emitting diode lamp (LED) for 300 min, resulting in a 100% degradation rate (dPFAS) and a 100% defluorination rate (dF-) of PFOA. These results were further validated by the complete absence of PFOA and fluorinated intermediate signals in both the fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance (19F NMR) spectra and the high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) chromatograms (Fig. 2a, entry 1 and 2b, c; Supplementary Fig. 2). This result is remarkable, as few technologies can achieve the complete breakdown of PFOA with such low energy consumption and and simplicity, especially considering that fluorinated intermediates are typically more challenging to degrade than PFOA itself39.

Control reactions were conducted to substantiate the proposed transformation mechanism of PFOA. The concentrations of fluoride ions (F−) and trifluoromethanesulfonic acid ions ([OTf]−) were measured at regular intervals using an ion-selective electrode and HPLC-MS/MS, respectively, to confirm that the F− in the solution originated exclusively from the degradation of PFOA (Supplementary Fig. 3). No degradation was observed in the absence of Cu2+ or light irradiation (Fig. 2a, entries 2–3). Additional testing of LED light sources40,41 revealed that near-UV to visible light could effectively induce the defluorination reaction (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). Increasing the excitation wavelength to λmax = 405 nm and 445 nm resulted in pronounced decreases in both the degradation rate and the defluorination rate. Nevertheless, >99% defluorination was still achieved within 900 min (15 h) and 2700 min (45 h), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, irradiation with a λmax = 500 nm LED produced negligible reactivity (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, the presence of an equimolar base was found to be essential for the deprotonation of PFOA, a prerequisite for its effective coordination with copper (Fig. 2a, entry 4; Supplementary Fig. 6). Notably, effective defluorination can also be achieved by replacing NaOH with potassium hydroxide (KOH) or aqueous ammonia (NH4OH) (Supplementary Fig. 6), which extends the range of applications of this method. As expected, the omission of oxygen (O2) (under nitrogen (N2) conditions) resulted in minimal degradation and defluorination of PFOA, owing to the absence of an external oxidant required to reoxidize Cu+ to Cu2+. (Fig. 2a, entry 5).

The choice of solvent was critical, with only MeCN being efficient (Fig. 2a, entry 6; Supplementary Fig. 7). It has been suggested that nitrile ligation to copper might have been necessary to stabilize the copper complexes for the LMCT process42. Furthermore, MeCN is a suitable solvent for slowing the inefficient ligand exchange process because of its lower coordination energy with copper, which was supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Fig. 8)43. Further evaluation of cost-effective commercial copper sources revealed that replacing Cu(OTf)2 with other Cu2+ salts were also capable of promoting the degradation and defluorination of PFOA (Fig. 2a, entry 7; Supplementary Fig. 9). Cu sources with low solubility, such as cupric sulfate (CuSO4), cupric oxide (CuO), cupric hydroxide (Cu(OH)2), and cupric fluoride (CuF2), or those with nondissociating anions, such as cupric chloride (CuCl2), could not efficiently react with deprotonated PFOA to form photosensitive copper perfluorocarboxylate, leading to reduced photoreactivity. Notably, cupric tetrafluoroborate (Cu(BF4)2) was also effective in facilitating this transformation, likely due to the superior leaving ability of the BF₄⁻ group44. Finally, to validate the scalability of the reaction, experiments were conducted across a wide range of scales, from an environmentally relevant level (0.0001 mmol) (Fig. 2a, entry 8) to a larger scale (5.0 mmol) (Fig. 2a, entry 9), consistently achieving efficient degradation and defluorination of PFOA.

Structural and photophysical features of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate

To investigate the photoexcitation properties of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate, a series of UV-Vis spectroscopies was conducted. In solutions containing only the Cu2+ salt or deprotonated PFOA, an absorption peak appeared at approximately 200 nm. However, the combination of the Cu2+ salt, PFOA, and NaOH resulted in a pronounced absorption band at λmax = 265 nm, extending beyond 400 nm and partially overlapping with the emission spectrum of the LED light source (Fig. 3a).

a Absorption spectra of various solutions ([Cu2+]: [PFOA]: [NaOH] = 2:1:1, [PFOA] = (0.5 mmol/L)). b Job’s method for deprotonated PFOA and Cu2+ salt. Solid lines represent the best fit. View of the molecular structure of the (c) 2:1 and (d) 1:1 stoichiometric complexes (carbon, gray; oxygen, red; copper, orange; and nitrogen, blue). e In situ FTIR analysis of CO2 evolution and C−F signal reduction during the reaction. f Concentrations of intermediates and (g) F mass balance over time. Error bars represent standard deviation.

To determine the stoichiometry of the complex, Job’s method45 was employed by maintaining constant total concentrations of the deprotonated PFOA and Cu2+ while systematically varying their molar ratios. The analysis revealed a molar fraction of 0.67 for deprotonated PFOA within the complex under sufficient component availability, suggesting that two PFOA molecules coordinate with one Cu2+ (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 10). When the Cu²⁺ concentration exceeds that of PFOA, the coordination stoichiometry can shifts to 1:1. To explore this phenomenon theoretically, both 1:1 and 1:2 stoichiometric complexes were constructed using the B3LYP functional with DFT-D3BJ dispersion correction (Fig. 3c, d)46. In both structures, the carboxylate group of PFOA chelated the copper center through its two oxygen atoms. The calculated LMCT excitation energies were 3.68 eV and 3.79 eV for the 1:1 and 1:2 Cu2+-PFOA complexes, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12). Notably, the lowest excitation energy of uncoordinated PFOA is as high as 5.91 eV, accounting for its intrinsic resistance to direct photolysis. These results of these calculations indicate that higher Cu²⁺ concentrations facilitate the formation of coordination complexes with reduced LMCT excitation thresholds, thereby enhancing the accessibility of the electron transfer process under light irradiation.

This computational insight was further supported by experimental data. At a fixed concentration of deprotonated PFOA, stepwise increases in Cu2+ concentration led to an increase in intensity that plateaued at a 1:1 Cu2+/PFOA molar ratio, accompanied by a redshift of the absorption maximum from 249 to 265 nm (Supplementary Fig. 13). Correspondingly, substoichiometric additions of Cu2+ (e.g., 0.1–0.75 equiv.) resulted in sluggish degradation, whereas stoichiometric addition (1.0 equiv., 1:1 Cu2+/PFOA molar ratio) significantly enhanced both degradation and defluorination efficiencies (Supplementary Fig. 14). Further increases in Cu2+ concentration beyond stoichiometric levels (e.g., 4 equiv.) offered no markedly improvement.

Preliminary mechanistic studies supported that photoexcited LMCT from PFOA to Cu2+ initiated the degradation process. Under a N2 atmosphere, the initial addition of 1.0 equiv. Cu2+ resulted in minimal defluorination ( < 1% after 60 min) (Supplementary Fig. 15). Subsequent addition of another 1.0 equiv. Cu2+ did not significantly improve the defluorination efficiency. In the absence of an external oxidant (e.g., O2), the Cu+ species generated via LMCT could not be reoxidized to Cu2+, thereby disrupting the reaction cycle of Cu+/Cu2+ (Supplementary Fig. 15). This accumulation of Cu+ was confirmed by the formation of the purple [Cu(biq)2]+ complex (λmax = 546 nm) upon the addition of 2,2’-biquinoline (biq) (Supplementary Fig. 16)42. Although the introduction of 2.0 equiv. peroxide oxidant moderately enhanced the defluorination, a substantial increase in efficiency was observed only after transferring the system to aerobic conditions (Supplementary Fig. 15). Sustained regeneration of Cu2+ is thus essential to maintain the photoreaction, supporting the electron transfer from PFOA to Cu2+ and subsequently proposed mechanism (Fig. 4, complete defluorination of 1.0 equiv. of PFOA required 7.0–14.0 equiv. of Cu2+).

Using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent, electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy provided compelling evidence for the involvement of O2 in the reaction. In the presence of Cu2+ and deprotonated PFOA, a distinct DMPO−Superoxide radical (O2•−) adduct signal was detected in the system (Supplementary Fig. 17a), which was absent in the control system containing only Cu2+. These results provide direct evidence for the involvement of O2: following the LMCT process, Cu2+ species can be regeneration through the oxidation of Cu+ by O2 (ECu(II)/Cu(I)* = − 1.54 V vs SCE; Eox = +0.33 V for O2)47, as described in Eq. 148.

Mechanisms of photochemical degradation of PFOA

The photoexcited LMCT process can generate perfluoroalkyl carboxyl radicals29, which subsequently lead to the release of CO2, as confirmed by in situ FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 3e). A continuous increase in the CO2 signal at 2343 cm−1 was observed during the course of the reaction29. Meanwhile, the characteristic C = O band at 1650 cm−1 remained largely unchanged49, while the C−F stretching signals (1000–1300 cm−1) gradually diminished after 9 min of irradiation50. This spectral evolution is consistent with a chain-shortening mechanism involving the sequential removal of the CF2 unit and the formation of short-chain carboxylic acids, as previously documented in the literature51.

As described above, the presence of O2•− was confirmed by ESR spectroscopy in our reaction system. We also investigated the potential involvement of other reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the defluorination of perfluoroalkyl carboxyl radicals, particularly HO• and singlet oxygen (1O2). Notably, no signal corresponding to TEMP − 1O2 was observed (Supplementary Fig. 17c). A weak DMPO − HO• signal was detected in the presence of Cu2+ alone (Supplementary Fig. 17b), which likely originated from the photochemical LMCT process between coordinated water molecules and Cu2+ under light irradiation52,53 (Eq. 2). In contrast, a markedly stronger DMPO − HO• signal was observed in the system containing both Cu2+ and deprotonated PFOA, suggesting that O2•− may be converted to HO•, as supported by previous literature (Eqs. 3, 4)54. A number of studies have demonstrated that although O2•− and HO• cannot initiate PFOA degradation, they can facilitate specific steps in the degradation process, such as the hydroxylation during chain-shortening55,56,57. Given their comparable auxiliary roles, the higher oxidative potential of HO•, and the technical challenges associated with effectively quenching O2•− in MeCN, our investigation primarily focused on the involvement of HO•. The addition of tert-butanol (tBuOH) and MeOH, both known HO• scavengers (kHO• = 3.8–7.6 × 108 and 9.7 × 108 M−1 s−1, respectively)58, caused only a slight decrease in the defluorination efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 18), indicating that HO• plays a minor promotional role and is not the dominant factor responsible for PFOA defluorination in this reaction system.

Degradation intermediates of PFOA were identified. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled with high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometry (HRMS) was used for suspected screening. In addition to the chain-shortening products (short-chain PFCA), no other possible fluorinated byproducts, such as H/F exchange products (for example, C7F14HCOO− and C7F13H2COO−), were detected (Supplementary Fig. 19). Target analysis of PFCA, including PFOA, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA, C7), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFHxA, C6), perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA, C5), perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA, C4), perfluoropropanoic acid (PFPrA, C3), and TFA (C2), was quantified via HPLC-MS/MS (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

As the reaction time increased, the concentrations of PFCA (C2–C7) initially increased but then decreased, with nearly all PFCA disappearing within 300 min (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 2b). The fluorine mass balance59 showed that HF was the primary product of PFOA degradation, which steadily increased over time. Short-chain PFCA concentrations peaked at 60 min (51%), before declining. As the irradiation time increased, the fluorine mass was close to 100% and remained stable, confirming that all degradation intermediates and products (HF) of PFOA were accounted for (Fig. 3g)60.

The mechanism of PFOA chain-shortening photochemical degradation was proposed based on the detected degradation intermediates and DFT calculations (Fig. 4a). According to previous studies, the formation of C7F15COO• marked the initial step in PFOA degradation18,27,61. Under basic conditions, PFOA predominantly existed as an anion with an electron removal energy of 138.73 kcal/mol (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step I), making its degradation difficult without Cu2+. In contrast, through photoexcited LMCT of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate, C7F15COO− could lose an electron to form C7F15COO• with a favorable change in Gibbs free energy between the byproduct and reactant (ΔG) of −85.63 kcal/mol, which was also significantly lower than that for the reaction with HO• (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step Ⅰ). This radical subsequently underwent decarboxylation to generate C7F15• with a transition state (TS) energy barrier ΔG‡ of only 2.53 kcal/mol, indicating that the reaction occurred easily (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step I). Given the well-known strong oxidizing ability of Cu2+ toward carbon-centered radicals, the resulting C7F15• radical was likely oxidized by Cu2+ to form a cationic species (ΔG = −75.48 kcal/mol). This cationic intermediate then reacted with OH− to produce C7F15OH (ΔG = −88.62 kcal/mol) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step Ⅱ). A direct reaction between C7F15• and HO• was also plausible, as it resulted in a highly negative ΔG (−94.31 kcal/mol) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step Ⅱ). Both pathways are plausible for this system. The Cu+ generated in steps Ⅰ and II could be reoxidized to Cu2+ by O2, concurrently producing O2•⁻, which led to the formation of HO• by Eqs. 3, 4. C7F15OH subsequently eliminated HF to form C6F13COF. Although this elimination reaction exhibited a high energy barrier (ΔG‡ = 42.12 kcal/mol) under standard conditions, the barrier decreased to 7.85 kcal/mol in the presence of two water molecules, enhancing the feasibility of this reaction (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step Ⅲ)62. C6F13COF was attacked by OH− to form C6F13FCOOH−, with the ΔG of −56.28 kcal/mol. This intermediate then underwent an additional low-barrier HF elimination step (ΔG‡ = 6.87 kcal/mol) to yield C6F13COO−, which has one fewer carbon atom than PFOA (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2, step Ⅳ). Degradation of C6F13COO− occurred through similar chain-shortening and defluorination steps, ultimately converting PFOA into CO2 and HF.

LMCT photochemical degradation of other PFAS

To assess whether similar degradation occurred in other PFAS systems, we first conducted photochemical degradation experiments on additional C2–C9 PFCA. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, both degradation and defluorination rates progressively declined with increasing PFCA chain length. TFA (C2), the most abundant PFAS in the environment and a terminal degradation product of many PFAS63, exhibited the fastest kinetics, reaching >99% degradation and defluorination within 60 min and complete removal by 120 min. In contrast, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA, C9) displayed the slowest reactivity. Notably, C4 and C6 PFCA, which are increasingly employed as alternatives to PFOA64, achieved degradation and defluorination efficiencies exceeding 99% and 98%, respectively, within 180 min. These findings contrast with prior studies reporting greater stability and lower reactivity of short-chain PFCA23,65,66,67. Most of these earlier works investigated PFCA degradation through strong oxidative or reductive processes, in which the inherent chemical stability of short-chain PFCA limited their susceptibility to bond cleavage. In this system, however, the degradation is initiated by the LMCT pathway. Coordination with Cu2+ yielded similar excited-state energies across chain lengths (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Table 3), resulting in comparable electron loss rates. This indicates that the initial step of degradation—electron loss from PFCA triggered by LMCT—proceeds at a similar rate regardless of chain length. However, during the degradation process, longer-chain PFCA were converted into shorter-chain PFCA, which remained reactive, thereby slowing the overall degradation and defluorination of the parent PFCA. As a consequence, long-chain PFCA exhibit overall slower degradation and defluorination rates compared to their short-chain counterparts.

a Concentration and (b) defluorination rate changes of C2-C9 PFCA over time. c Relationship between the PFCA chain length and excited energy level. d Concentration and defluorination rate changes of GenX. e HPLC-MS/MS chromatograms of GenX degradation. f Concentration and defluorination rate changes of three additional PFECA. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Photodegradation experiments were also conducted on perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids (PFECA), representing another major class of PFAS contaminants. GenX, a six-carbon PFECA formed by the dimerization of two hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) molecules (structural formula in Supplementary Table 6), is a substitute for PFOA that exhibits comparable or even higher toxicity and bioaccumulation compared to PFOA68. As shown in Fig. 6d, GenX exhibited >99% degradation and defluorination rates within 180 min in this system. Targeted analysis of possible degradation products was performed, identifying TFA and PFPrA as intermediates (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Fig. 20). The concentrations of these intermediates initially increased and then decreased as GenX degraded. Unlike PFOA, the literature concerning the photooxidation degradation pathway of GenX is limited69. It has been reported that GenX degrades poorly in a UV/persulfate system, likely due to the CF3 group at the α-carbon acting as a barrier to prevent cleavage by SO4−• or HO• at the carboxyl group70. Instead of relying on radical attack, we exploited its reaction characteristics (Fig. 4b). In the presence of Cu2+, GenX first lost an electron through the LMCT process, with a favorable ΔG of −85.07 kcal/mol, followed by decarboxylation to generate C3F7OCF(CF3)• (ΔG‡ = 2.76 kcal/mol) (Supplementary Fig. 21, Supplementary Table 4). Owing to the ether oxygen replacing the γ-carbon, the generated radical could directly cleave the C − O bond, producing CF3COF and C3F7•, with a calculated ΔG‡ of 13.08 kcal/mol (Supplementary Table 4, Path A)69,71. These two species could then follow the defluorination pathway described for PFOA to form TFA and PFPrA. Alternatively, C3F7OCF(CF3)• reacted similarly to a perfluoroalkyl radical, forming a perfluoroalkyl alcohol (C3F7OCF(CF3)OH), which then lost hydrogen fluoride to generate a perfluoroalkyl ester (C3F7OC(CF3)OF). Through hydrolysis, the ester continued to defluorinate via the PFOA reaction pathway (Supplementary Table 4, Path B)4,72.

Other PFECA also exhibited efficient degradation (Fig. 6f), including perfluoro(4-methoxybutanoic) acid (PFMOBA), perfluoro-2,5-dimethyl-3,6-dioxaheptanoic acid (HFPO-TA(C7)), and perfluoro-2,5-dimethyl-3,6-dioxaoctanoic acid (HFPO-TA(C8)). As a representative linear monoether-PFECA73, PFMOBA exhibited a degradation efficiency comparable to that of PFPeA with the same carbon chain length. Targeted HPLC-MS/MS screening revealed that the degradation of PFMOBA did not produce short-chain PFCA such as TFA or PFPrA (Supplementary Fig. 22). Based on these observations, we propose that PFMOBA degradation proceeds through progressive CF2 unit removal near the carboxyl group, leading to the formation of CF3 − O − CF2COOH. Subsequent LMCT-induced decarboxylation generates CF3 − O − CF2• radical, which follows parallel A/B pathways similar to those proposed for GenX degradation, ultimately producing CF3OH and COF2 that can rapidly hydrolyze.

For the diether-PFECA, HFPO-TA(C7) and HFPO-TA(C8) were first identified and reported by Yao et al. 74 in 2022 in the High-Tech Fluorochemical Industrial Zone of Changshu (China), with their concentrations showing significant increases from 2016 to 2021. Notably, HFPO-TA(C7) was detected at an exceptionally high concentration (0.447 mg/L) in wastewater treatment plant effluents, accounting for 82% of the total PFAS load, likely indicating its application as a substitute for PFOA in fluoropolymer manufacturing74. In this current study, both HFPO-TA(C7) and HFPO-TA(C8) exhibited comparable overall degradation efficiencies. In the initial stage, their degradation followed pathways analogous to those proposed for GenX, and subsequently proceeded through linear monoether-PFECA degradation routes similar to PFMOBA. Targeted HPLC-MS/MS analysis detected only TFA as an intermediate (Supplementary Fig. 22). Importantly, due to the presence of a methyl group rather than an ethyl group at the ether linkage distal to the carboxyl group, HFPO-TA(C7) generated fewer TFA intermediates during degradation and achieved complete defluorination more rapidly than HFPO-TA(C8).

Advantages and challenges of the present system

In contrast to recently reported PFOA degradation methods conducted in organic concentrates or diluted aqueous systems, our photochemical reaction platform achieved rapid and highly efficient degradation and defluorination (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Table 5)16,23,24,25,51,67,75,76,77,78,79,80. As discussed in the Introduction section, most previously reported strategies relying on reactive species-based pathways were limited by uncontrolled degradation reactions and suffered from incomplete defluorination and the formation of multiple fluorinated byproducts. Our system harnessed the intrinsic reactivity of PFOA to trigger a single-pathway chain-shortening degradation via a photoinduced LMCT mechanism, ultimately achieving up to 100% defluorination. Moreover, this strategy exhibited exceptional efficacy toward short-chain PFCA, as exemplified by its remarkable performance in TFA, along with significant advantages in reaction rate and energy efficiency (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Table 5)23,25,80,81,82,83,84. TFA was widely regarded as a persistent end-product of PFAS degradation, and previously reported methods for its decomposition were extremely limited and inefficient63,82,83. Therefore, our system addressed a critical bottleneck in the remediation of short-chain PFCA, extending the applicability of photochemical strategies to even the most recalcitrant PFAS.

Moreover, the reaction proceeded effectively under near-UV to visible light without requiring elevated temperatures or an inert atmosphere, offering a practical and adaptable strategy. This feature was particularly advantageous for the treatment of MeCN-based desorption eluates from PFCA-laden adsorbents, where PFCA predominantly existed in their anionic form (thereby disrupting both electrostatic and non-electrostatic interactions involved in PFCA adsorption)85,86. Building upon this observation, we designed an integrated adsorption-degradation experiment (Supplementary Text 3, Supplementary Fig. 23a). A total of 50.0 L of simulated PFCA-contaminated water was treated using our previously reported home-made capture column filled with carbonaceous adsorbents87. PFCA was subsequently desorbed using MeCN containing NH4OH, achieving recovery rates exceeding 98% from the adsorbent (Supplementary Fig. 23b). The resulting eluates were then directly subjected to photocatalytic degradation after introducing Cu[OTf]2, achieving degradation and defluorination rates exceeding 99% for PFCA within 540 min under the described conditions (Supplementary Fig. 23c). This approach effectively integrated adsorption enrichment and light-driven degradation into a single streamlined workflow. Therefore, this integrated adsorption-degradation workflow illustrates a promising strategy for translating the mechanistic insights from our study into a scalable and practical solution for PFAS remediation.

Despite the high efficacy of Cu(OTf)2 and Cu(BF4)2 in driving the photochemical degradation, a key limitation of this method lies in the use of fluorinated copper salts in homogeneous systems. This raises concerns regarding the introduction of additional fluorochemicals, difficulties in metal recovery, and post-reaction effluent management. To address these challenges, we implemented a straightforward liquid-liquid extraction protocol for post-reaction separation. Upon completion of the reaction, 5.0 mL of 1.0 mol/L NaOH aqueous solution was added to the 20 mL MeCN-based reaction mixture, followed by vigorous shaking and phase separation (Supplementary Fig. 24). Ion analysis confirmed that the resulting H2O phase effectively captured all the [OTf]−, F−, and Cu2+. Upon drying the MeCN phase with 3 Å molecular sieves, the solvent was directly recyclable and retained its efficacy in promoting PFOA complete degradation and defluorination within 300 min. To further improve the environmental sustainability and practical applicability of this strategy, future efforts should prioritize the development of heterogeneous copper-based systems that retain the high reactivity of Cu(OTf)2 and Cu(BF4)2 while eliminating the need for fluorinated components. Given that the photoexcited LMCT of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate has been established as the key trigger for defluorination reaction, promising directions include immobilizing Cu²⁺ centers onto solid supports or designing ligand-engineered frameworks to enable recyclable reaction platforms.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive investigation of the near-UV to visible light-driven photochemical degradation mechanism of PFAS in the presence of Cu2+. Leveraging the LMCT of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate, the described photoexcited degradation mechanism enables energy-efficient permineralization of PFAS under light excitation, featuring a straightforward system, well-defined intermediate, high fluoride ion recovery, and a singular degradation pathway. This thorough mechanistic investigation, supported by experimental data and DFT calculations, revealed that the chain-shortening degradation reaction was initiated by the LMCT process. PFCA with different chain lengths and various perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids exhibited excellent degradation and defluorination efficiencies in this system. The observed reactivity of perfluoroalkyl anions underscores their potential for developing targeted degradation strategies for various PFAS. Understanding the unique chemical properties and reactivity patterns of PFAS is crucial for designing effective remediation methods. Furthermore, these insights guide future research into the degradation pathways of other persistent organic pollutants and have valuable implications for pollutant degradation in concentrated nonaqueous phases under near-UV to visible light. This work provides valuable perspectives for tackling PFAS contamination and advancing environmental remediation efforts.

Methods

Chemicals

A full list of chemical reagents is provided in Supplementary Table 6. Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were procured from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification.

Photochemical degradation of PFAS

Batch photochemical degradation of PFAS was conducted in a photochemical reactor equipped with a 365 nm LED lamp and 40.0 mL quartz tubes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, 0.2 mmol of the Cu sources was added to a 10.0 mL MeCN solution containing 0.1 mmol PFAS, followed by 0.1 mmol (4.0 mg) NaOH. The mixture was exposed to air, covered with a lid featuring gas exchange holes and stirred thoroughly in the dark. For reactions under 405, 445, and 500 nm LEDs, a sealed lid without gas exchange holes was used instead. The quartz tube was placed 5.0 cm in front of a 365 nm LED light source and irradiated while being maintained at 21.4 ± 0.2 °C using a fan cooling system (Supplementary Table 1). The emission spectrum of the LED is shown in Supplementary Fig 4. The reaction mixture was magnetically stirred at 500 rpm. An N2 atmosphere was established either by experimenting with a N2 glove box. For the dark control group, the quartz tube was completely covered with aluminum foil to prevent light exposure. Aliquots (50.0 µL or 500.0 µL) were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals and stored at 4 °C until subsequent analysis. Each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure data accuracy.

The dPFAS and dF- are two key parameters used to evaluate the extent of PFAS destruction in the system. The dPFAS refers to the reduction in the concentration of PFAS molecules in solution over time, indicating the breakdown of the parent PFAS compound. In contrast, the dF- reflects the extent to which fluorine atoms from both the parent PFAS and its fluorinated degradation products are converted into inorganic fluoride ions (which would demonstrate C–F bond cleavage). This parameter assesses the overall efficiency of fluorine removal from the system, rather than merely the disappearance of the parent PFAS compound.

The dPFAS was calculated by Eq. 5:

where Ct is the measured PFAS concentration (mol/L) at time t, C0 is the initial PFAS concentration (mol/L), t is time (min).

The dF- was calculated by Eq. 6:

where CF- was the concentration of fluoride ion (mol/L); C0 was the initial concentration of PFAS (mol/L); and n corresponded to the number of fluorine atoms in one PFAS molecule.

Analytical methods

Target analysis and quantification of PFAS were performed using HPLC (Agilent Technologies 1260 series, U.S.) coupled with MS/MS (Agilent 6460 Triple Quad system, U.S.). The degradation intermediates of PFOA and GenX were identified using UPLC (Ultimate 3000 Series, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled with HRMS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), and their detailed operation conditions and procedures are described in Supplementary Text 1. The ESR signal detection and spectroscopic analyses are described in detail in Supplementary Text 1. The concentration of F− was determined using an ion-selective electrode connected to an HQ30D portable multimeter (HACH, U.S.). The detection limit for F− was 0.01 mg/L. The F– concentration was further verified by ion chromatography using a Thermo Scientific ICS5000+ system.

Computational methods

Theoretical calculations were performed using DFT with the Gaussian 16 C.01 software package. The structures of the studied PFAS molecules were fully optimized using the B3LYP functional with the DFT-D3BJ dispersion correction. The molecular excitation transitions were analyzed by the natural transition orbital (NTO) method using the Multiwfn program. The NTO method simplifies complex excitations by representing them as pairs of “hole” and “electron” orbitals derived from the transition density matrix. This approach provides intuitive visualization of electronic transitions and facilitates the interpretation of excited states. Details are provided in Supplementary Text 2. Cartesian coordinates of optimized structures are provided in the Source Data file.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Xiao, F. Emerging poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: a review of the current literature. Water Res. 124, 482–495 (2017).

Evich, M. G. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science 375, eabg9065 (2022).

Schymanski, E. L. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 million and growing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 16918–16928 (2023).

Vakili, M. et al. Removal of HFPO-DA (GenX) from aqueous solutions: a mini-review. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130266 (2021).

Ehsan, M. N., Riza, M., Pervez, M. N. & Liang, Y. Source identification and distribution of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the freshwater environment of USA. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 2021–2046 (2025).

Andrea, K. T. et al. Predictions of groundwater PFAS occurrence at drinking water supply depths in the United States. Science 386, 748–755 (2024).

Guglielmi, G. How to destroy ‘forever chemicals’: cheap method breaks down PFAS. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02247-0 (2022).

Sunderland, E. M. et al. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 29, 131–147 (2018).

Poothong, S., Papadopoulou, E., Padilla-Sánchez, J. A., Thomsen, C. & Haug, L. S. Multiple pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs): from external exposure to human blood. Environ. Int. 134, 105244 (2019).

Poothong, S., Thomsen, C., Padilla-Sánchez, J. A., Papadopoulou, E. & Haug, L. S. Distribution of novel and well-known poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in human serum, plasma, and whole blood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13388–13396 (2017).

Furlow, B. US EPA sets historic new restrictions on toxic PFAS in drinking water. Lancet Oncol. 25, 181 (2024).

Saleh, L. et al. PFAS degradation by anodic electrooxidation: influence of BDD electrode configuration and presence of dissolved organic matter. Chem. Eng. J. 489, 151355 (2024).

Jia, H., Yunjie, Z. & Lan, L. Enhanced selective photocatalytic reduction and oxidation of perfluorooctanoic acid on Bi/Bi5O7I decorated with poly (triazine imide). J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 136257 (2024).

Niu, J., Lin, H., Gong, C. & Sun, X. Theoretical and experimental insights into the electrochemical mineralization mechanism of perfluorooctanoic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 14341–14349 (2013).

Cui, J., Gao, P. & Deng, Y. Destruction of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with advanced reduction processes (ARPs): a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3752–3766 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Electrostatic field in contact-electro-catalysis driven C–F bond cleavage of perfluoroalkyl substances. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402440 (2024).

Alinezhad, A. et al. Mechanistic investigations of thermal decomposition of perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids and short-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 8796–8807 (2023).

Verma, S., Varma, R. S. & Nadagouda, M. N. Remediation and mineralization processes for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 794, 148987 (2021).

Yu, H., Chen, H., Fang, B. & Sun, H. Sorptive removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from aqueous solution: enhanced sorption, challenges and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 861, 160647 (2022).

Altarawneh, M., Almatarneh, M. H. & Dlugogorski, B. Z. Thermal decomposition of perfluorinated carboxylic acids: kinetic model and theoretical requirements for PFAS incineration. Chemosphere 286, 131685 (2021).

Wenjiao, L. et al. Remediation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contaminated soil via soil washing with various water-organic solvents. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 135943 (2024).

Gutiérrez, A., Maletta, A., Aparicio, S. & Atilhan, M. A theoretical study of low concentration per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) remediation from wastewater by novel hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents (HDES) extraction agents. J. Mol. Liq. 383, 122101 (2023).

Trang, B. et al. Low-temperature mineralization of perfluorocarboxylic acids. Science 377, 839–845 (2022).

Sinha, S., Chaturvedi, A., Gautam, R. K. & Jiang, J. J. Molecular Cu electrocatalyst escalates ambient perfluorooctanoic acid degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27390–27396 (2023).

Zhang, H., Chen, J. X., Qu, J. P. & Kang, Y. B. Photocatalytic low-temperature defluorination of PFASs. Nature 635, 610–617 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Photocatalytic C–F bond activation in small molecules and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Nature 637, 601–607 (2025).

Liu, F., Guan, X. & Xiao, F. Photodegradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in water: a review of fundamentals and applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 439, 129580 (2022).

Luo, P. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) from water: A mini review. Environ. Pollut. 343, 123212 (2023).

Campbell, B. M. et al. Electrophotocatalytic perfluoroalkylation by LMCT excitation of Ag(II) perfluoroalkyl carboxylates. Science 383, 279–284 (2023).

May, A. M. & Dempsey, J. L. A new era of LMCT: leveraging ligand-to-metal charge transfer excited states for photochemical reactions. Chem. Sci. 15, 6661–6678 (2024).

An, Q., Chang, L., Pan, H. & Zuo, Z. Ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) catalysis: harnessing simple cerium catalysts for selective functionalization of inert C–H and C–C bonds. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 2915–2927 (2024).

Birnthaler, D., Narobe, R., Lopez-Berguno, E., Haag, C. & König, B. Synthetic application of bismuth LMCT photocatalysis in radical coupling reactions. ACS Catal. 13, 1125–1132 (2023).

Fang, Y. & Guo, Y. Copper-based non-precious metal heterogeneous catalysts for environmental remediation. Chin. J. Catal. 39, 566–582 (2018).

Hossain, A., Bhattacharyya, A. & Reiser, O. Copper’s rapid ascent in visible-light photoredox catalysis. Science 364, 9713 (2019).

Dow, N. W. et al. Decarboxylative borylation and cross-coupling of (hetero)aryl acids enabled by copper charge transfer catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6163–6172 (2022).

Xu, P., Su, W. & Ritter, T. Decarboxylative sulfoximination of benzoic acids enabled by photoinduced ligand-to-copper charge transfer. Chem. Sci. 13, 13611–13616 (2022).

Li, Q. Y. et al. Decarboxylative cross-nucleophile coupling via ligand-to-metal charge transfer photoexcitation of Cu(ii) carboxylates. Nat. Chem. 14, 94–99 (2022).

Maosen, Z. et al. Identification of emerging PFAS in industrial sludge from North China: Release risk assessment by the TOP assay. Water Res 268, 122667 (2024).

Reddy, C. V. et al. A critical science mapping approach on removal mechanism and pathways of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water and wastewater: a comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. J. 492, 152272 (2024).

Arima, Y. et al. Multiphoton-driven photocatalytic defluorination of persistent perfluoroalkyl substances and polymers by visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408687 (2024).

Gao, J. et al. Photochemical degradation pathways and near-complete defluorination of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl substances. Nat. Water 1, 381–390 (2023).

Xu, P., López-Rojas, P. & Ritter, T. Radical decarboxylative carbometalation of benzoic acids: a solution to aromatic decarboxylative fluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5349–5354 (2021).

Avila, D. V., Brown, C. E., Ingold, K. U. & Lusztyk, J. Solvent effects on the competitive β-scission and hydrogen atom abstraction reactions of the cumyloxyl radical. Resolution of a long-standing problem. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 466–470 (1993).

Lozada, J., Lin, W. X., Cao-Shen, R. M., Tai, R. A. & Perrin, D. M. Salt metathesis: Tetrafluoroborate anion rapidly fluoridates organoboronic acids to give organotrifluoroborates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215371 (2023).

Renny, J. S., Tomasevich, L. L., Tallmadge, E. H. & Collum, D. B. Method of continuous variations: applications of Job plots to the study of molecular associations in organometallic chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, e201311998 (2013).

Moellmann, J. & Grimme, S. DFT-D3 study of some molecular crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 7615–7621 (2014).

Mandal, T., Katta, N., Paps, H. & Reiser, O. Merging Cu(I) and Cu(II) photocatalysis: Development of a versatile oxohalogenation protocol for the sequential Cu(II)/Cu(I)-catalyzed oxoallylation of vinylarenes. Org. Inorg. Au 3, 171–176 (2023).

Xu, L., Yan, K., Mao, Y. & Wu, D. Enhancing the dioxygen activation for arsenic removal by Cu0 nano-shell-decorated nZVI: synergistic effects and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 384, 123295 (2019).

Alonso-de-Linaje, V. et al. Enhanced sorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate by hydrotalcites. Environ. Technol. Innov. 21, 101231 (2020).

Gao, X. & Chorover, J. Adsorption of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid to iron oxide surfaces as studied by flow-through ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Environ. Chem. 9, 148–157 (2012).

Liu, X. et al. Fe3+ promoted the photocatalytic defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) over In2O3. EST Water 1, 2431–2439 (2021).

Reichlea, A. & Reiser, O. Light-induced homolysis of copper(II)-complexes – a perspective for photocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 14, 4449–4462 (2023).

Stahla, J. & König, B. A survey of the iron ligand-to-metal charge transfer chemistry in water. Green. Chem. 26, 3058–3071 (2024).

Luo, Z. et al. Environmental implications of superoxide radicals: from natural processes to engineering applications. Water Res. 261, 122023 (2024).

Javed, H. et al. Discerning the relevance of superoxide in PFOA degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 7, 653–658 (2020).

Glass, S. et al. Iron doping of hBN enhances the photocatalytic oxidative defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 22803–22811 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Mechanistic insight into the photo-oxidation of perfluorocarboxylic acid over boron nitride. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8942–8952 (2022).

Buxton, G. V., Greenstock, C. L., Helman, P. H. & Ross, A. B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 17, 513–886 (1988).

Duan, L. et al. Efficient photocatalytic PFOA degradation over boron nitride. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 7, 613–619 (2020).

Carter, K. E. & Farrell, J. Oxidative destruction of perfluorooctane sulfonate using boron-doped diamond film electrodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 6111–6115 (2008).

Chen, J., Qu, R., Pan, X. & Wang, Z. Oxidative degradation of triclosan by potassium permanganate: kinetics, degradation products, reaction mechanism, and toxicity evaluation. Water Res 103, 215–223 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Moores, A., Liu, J. & Ghoshal, S. New Insights into the degradation mechanism of perfluorooctanoic acid by persulfate from density functional theory and experimental data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 8672–8681 (2019).

Arp, H. P. H., Gredelj, A., Glüge, J., Scheringer, M. & Cousins, I. T. The global threat from the irreversible accumulation of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 19925–19935 (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. Nontarget identification of novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in soils from an oil refinery in southwestern China: a combined approach with TOP assay. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 20194–20205 (2023).

Qu, R. et al. Experimental and theoretical insights into the photochemical decomposition of environmentally persistent perfluorocarboxylic acids. Water Res 104, 34–43 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Kinetics and mechanism insights into the photodegradation of hydroperfluorocarboxylic acids in aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 348, 644–652 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from water by plasma treatment: insights into structural effects and underlying mechanisms. Water Res 253, 121316 (2024).

Wasel, O., King, H., Choi, Y. J., Lee, L. S. & Freeman, J. L. Differential developmental neurotoxicity and tissue uptake of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance alternatives, GenX and PFBS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 19274–19284 (2023).

Yang, L. H. et al. Is HFPO-DA (GenX) a suitable substitute for PFOA? A comprehensive degradation comparison of PFOA and GenX via electrooxidation. Environ. Res. 204, 111995 (2021).

Bao, Y. et al. Degradation of PFOA substitute: GenX (HFPO-DA ammonium salt): oxidation with UV/persulfate or reduction with UV/sulfite?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 11728–11734 (2018).

Zhu, Y. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of GenX in water using a new adsorptive photocatalyst. Water Res 220, 118650 (2022).

Pica, N. E. et al. Electrochemical oxidation of hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX): mechanistic insights and efficient treatment train with nanofiltration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12602–12609 (2019).

Miller, K. E. & Strynar, M. J. Improved tandem mass spectrometry detection and resolution of low molecular weight perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acid isomers. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 9, 747–751 (2022).

Yao, J. et al. Nontargeted identification and temporal trends of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a fluorochemical industrial zone and adjacent Taihu Lake. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7986–7996 (2022).

Li, Y., Che, N., Liu, N. & Li, C. Degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) using multiphase Fenton-like technology by reduced graphene oxide aerogel (rGAs) combined with BDD electrooxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 478, 147443 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Electro-Fenton degradation of PFOA in nano-confined spaces: the new degradation mechanism that only cathode involved. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 374, 125388 (2025).

Song, D. et al. Degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid by chlorine radical triggered an electrochemical oxidation system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 9416–9425 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Surface hydrophobicity of boron nitride promotes PFOA photocatalytic degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 483, 149134 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. Efficient removal of PFOA with an In2O3/persulfate system under solar light via the combined process of surface radicals and photogenerated holes. J. Hazard. Mater. 423, 127176 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Efficient decomposition of perfluoroalkyl substances by low concentration indole: new insights into the molecular mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 3530–3539 (2024).

Hori, H., Manita, R., Yamamoto, K., Kutsuna, S. & Kato, M. Efficient photochemical decomposition of trifluoroacetic acid and its analogues with electrolyzed sulfuric acid. J. Photoch. Photobio. A 332, 167–173 (2017).

Hori, H., Takano, Y., Koike, K., Takeuchi, K. & Einaga, H. Decomposition of environmentally persistent trifluoroacetic acid to fluoride ions by a homogeneous photocatalyst in water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 418–422 (2003).

Jiao, H. et al. Photoreductive defluorination of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in the aqueous phase by hydrated electrons. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 132724 (2022).

Bentel, M. J. et al. Defluorination of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) with hydrated electrons: Structural dependence and implications to PFAS remediation and management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 3718–3728 (2019).

Dixit, F., Dutta, R., Barbeau, B., Berube, P. & Mohseni, M. PFAS removal by ion exchange resins: a review. Chemosphere 272, 129777 (2021).

Ren, Z. et al. Combination of adsorption/desorption and photocatalytic reduction processes for PFOA removal from water by using an aminated biosorbent and a UV/sulfite system. Environ. Res. 228, 115930 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Rapid and efficient removal of ultrashort- and short-chain PFAS from contaminated water by pyrogenic carbons: a strategy via polypyrrole nanostructured coating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 16034–16045 (2025).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22036004 to H.S.), the Haihe Laboratory of Sustainable Chemical Transformations (Grant No. 24HHWCSS00017 to H.S.), the Science and Technology Major Project of Tianjin (Grant No. 23JCZDJC00390 to H.S.), the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Project at Southwest United Graduate School (Grant No. 202402AO370002 to P.Z.), and the 111 program, Ministry of Education, China (Grant No. B17025 to H.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z., H.S., and J.G. designed the research. J.G. performed the research. H.Y. and B.F. discussed and commented on the results and the manuscript. P.Z. and J.G. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yan-biao Kang, Xin Liu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, J., Zhang, P., Yu, H. et al. Photoexcited LMCT of Cu2+ perfluorocarboxylate for initiating efficient defluorination. Nat Commun 16, 11628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66739-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66739-z