Abstract

X-ray imaging requires effective light transmission through scintillation screens. However, solid or solution-based scintillators suffer from photon scattering and attenuation. While prior efforts have focused on improving light extraction in solid-state scintillators through nanostructuring or optical engineering, challenges remain in mitigating internal scattering losses. Here, we report a liquid scintillator-based strategy that eliminates light scattering by exploiting in-situ coordination between lanthanide ions and ionic liquid ligands. This coordination chemistry ensures high structural homogeneity and optical transparency. Combined with self-absorption-free lanthanides, this approach achieves over 93% scintillation light transmittance, boosting X-ray imaging spatial resolution to 26 lp mm-1 within a 1 mm scintillation screen. Our scintillators exhibit long-term stability and environmental compatibility, leveraging the inherent properties of ionic liquids for sustained and biocompatible X-ray imaging. Their fluidic and shape-adaptive nature enables the development of convex and zoom scintillation lenses, facilitating uniform omni-angle X-ray detection and in-situ zoom X-ray imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

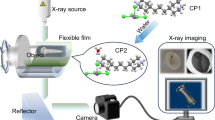

The increasing demand for high-contrast X-ray imaging in applications such as chest X-rays and security scanning has led to extensive research into improving imaging clarity1,2,3,4,5,6. A major challenge in X-ray imaging systems is optical crosstalk caused by lateral photon scattering, which degrades image resolution. Most existing systems rely on solid scintillation films, where uneven particle distribution within the polymer substrate leads to severe light scattering (Fig. 1)7,8,9. Several approaches have been explored to mitigate this issue. Reducing film thickness or diluting the scintillating particle concentration can lower photon collisions but also diminish radioluminescence intensity10. Glass and single-crystal scintillators offer improved transparency due to their uniform structure11,12,13, but their fabrication typically requires high temperatures, and they are challenging to integrate with commercial flat-panel detectors. Metamaterials can leverage waveguiding effects to enhance light extraction but are costly, time-consuming to produce, and limited by directional emission, restricting large-scale implementation14,15,16. Thus, a cost-effective, scalable approach to reducing light scattering without compromising scintillation performance remains an urgent need.

Solid scintillators, composed of micron-sized particles, suffer from severe light scattering, limiting scintillation light transmission. Solution mixture scintillators, with solute aggregation in the range of > 100 nm, exhibit moderate scattering, reducing optical clarity. In contrast, intrinsic liquid scintillators, with molecular-level homogeneity (< 1 nm particle size), minimize light scattering, enabling superior light penetration and enhanced X-ray imaging performance.

Inspired by the intrinsic transparency of water, liquid scintillators offer a promising solution. Highly homogeneous and optically clear, they eliminate photon scattering by design. While liquid scintillators have been explored using luminescent solutes dissolved or dispersed in solvents such as 2,5-diphenyloxazole@toluene (PPO@toluene), CsPbBr3@octane, and CsPb2Br5-CsPbBr3@H2O, these mixtures still suffer from concentration-dependent limitations17,18,19. Moreover, many existing liquid scintillators contain toxic lead or flammable organic solvents, raising safety concerns for practical applications. Developing a truly transparent, stable, and biocompatible liquid scintillator remains a key challenge in advancing X-ray imaging technologies.

We propose the development of intrinsic liquid scintillators by combining lanthanide ions with ionic liquids (Fig. 2a). Trivalent lanthanide ions, known for their high atomic numbers and stable electronic structures, effectively attenuate X-rays while providing abundant empty orbitals for coordination with functional ionic liquid ligands20,21,22. Ionic liquids, which are room-temperature molten salts, offer high electron density and strong electrostatic interactions, further enhancing coordination stability23. The in-situ coordination between lanthanide ions and ionic liquid ligands results in intrinsically homogeneous and transparent liquid scintillators24. Moreover, the non-volatility of ionic liquids improves the long-term stability, environmental safety, and biocompatibility of the scintillators.

a Schematic illustration of lanthanide-ion (Ln3+, Ln = Tb, Eu) coordination with ionic liquid (IL) ligands to form intrinsic liquid scintillators. The chemical structure shows Ln3+ coordinated with IL anions via sulfate and bromide functional groups. The inset fluorescence image demonstrates X-ray-induced luminescence of Tb(IL)3 and Eu(IL)3. b Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of IL precursors and Tb(IL)3 scintillators. The coordination between S = O groups and Tb3+ is evidenced by the shift in the S = O stretching vibration mode from 1169 cm−1 to 1488 cm−1 and the appearance of the Tb-O vibration mode. c, Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) fitting of Tb(IL)3 (top) compared to Tb(NO3)3 in acetone (bottom), confirming the formation of Tb–O-S coordination bonds (~2.17 Å) in the IL system, distinct from the Tb–O-N coordination (~2.26 Å) in the nitrate complex dissolved in acetone.

Results

Coordination in lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators

To validate our approach, we synthesized an ionic liquid ligand featuring an imidazole ring connected to a sulfonate group via a carbon chain, surrounded by free bromide ions (Br-). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy confirmed its structure, with characteristic peaks matching those reported for similar compounds (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1)21,25. The electron-rich sulfonate group facilitates coordination with lanthanide ions, while the heavy Br- enhances X-ray attenuation.

To induce coordination, we mixed the ionic liquid with lanthanide ions in acetone at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis of Tb3+ complexes revealed a shift in the sulfonate stretching vibration from ~1169 cm−1 to ~1488 cm−1, along with the appearance of a Tb-O vibration mode, confirming the formation of Tb-O bond in the Tb(IL)3 (Figs. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3)25,26. X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES, Supplementary Fig. 4) showed a higher peak intensity at the Tb L3 edge in Tb(IL)3 compared to Tb(NO3)3 dissolved in acetone (Tb(NO3)3@acetone), indicating stronger Tb-O coordination in Tb(IL)327,28. X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis confirmed a reduced Tb-O bond length (~2.17 Å in Tb(IL)3 vs. ~2.26 Å in Tb(NO3)3@acetone) (Fig. 2c). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations showed that a Tb3+ ion is coordinated with three ionic liquid ligands by forming Tb-O and Tb-S bonds, as evidenced by the average Fuzzy bond order of 0.85 and 0.26, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). This strong coordination enhances the viscosity of Tb(IL)3 (0.32 Pa•s), improving its stability and fluidic control (Supplementary Fig. 5).

By coordinating with different lanthanide ions, such as Tb3+ and Eu3+, our liquid scintillators enabled continuous color tuning in scintillation, ranging from green (CIE 1931 (0.39, 0.54)) to yellow (CIE 1931 (0.47, 0.49)) and red (CIE 1931 (0.62, 0.34)). This tunability was demonstrated in an X-ray excited multi-colored ‘NUS’ pattern (Inset in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Scintillation enhancement by dual-channel energy transfer

Lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators function as intrinsic liquid complexes, where lanthanide cations serve as emitters and organic ligands act as energy antennas. The energy transfer from ligands to lanthanide ions enhances luminescence, including radioluminescence29,30. To investigate this mechanism, we first analyzed the excitation-emission energy alignment of ionic liquid ligands and lanthanide ions under UV and X-ray excitation at room temperature (Fig. 3a). Under UV excitation, ionic liquid ligands showed photoluminescence peaks at ~386 nm and ~412 nm, corresponding to the S1-S0 singlet transitions of monomeric and polymeric ligands, respectively. The emission energy of ionic liquid ligands is insufficient to excite Tb3+, preventing energy transfer. In contrast, high-energy X-ray irradiation shifted radioluminescence to ~363 nm that overlaps with the Tb3+ excitation spectrum. Such a spectral match could trigger efficient resonance singlet energy transfer because of the short Tb-O bond length (~2.17 Å)31. We speculated that displacement of Br- ions through X-ray photon collisions is the cause of the blue shift, as Br- ions are weakly bound to the IL frameworks32,33. Time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations revealed that the dissociation of Br- ions lowers the high occupied molecular orbit (HOMO) level of IL, thus expanding HOMO-LUMO gap (Supplementary Fig. 7). This singlet energy transfer process was confirmed by the decreased radioluminescence intensity of ligands upon Tb3+ coordination (Fig. 3b). However, we found that this singlet-involved energy transfer accounts for only ~1.9% of the total radioluminescence enhancement in Tb(IL)3 scintillator (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, it is highly likely that triplet excitons contribute more to the radioluminescence of Tb(IL)334. To explore this possibility, we measured the low-temperature (77 K) luminescence spectrum of IL and determined that its triplet energy state is located at ~2.73 eV, which is slightly higher than the 5D4 emitting state of Tb3+ (Fig. 3c). This moderate energy gap (~0.19 eV) facilitates efficient energy transfer from the IL triplet state to the 5D4 emitting state of Tb3+, thereby further boosting the radioluminescence20. Thus, in addition to the direct Tb3+ radioluminescence, ionic liquid ligands contribute to effective radioluminescence enhancement through dual-channel energy transfer involving both singlet and triplet excitons (Fig. 3d).

a Excitation (Ex.) and emission (Em.) spectra of Tb(IL)3 under UV (PL, top) and X-ray (RL, bottom) excitation. b Radioluminescence (RL) spectra of Tb(IL)3 and free IL ligands, showing reduced IL emission upon coordination with Tb3+. Inset: magnified view of the RL spectrum (300–450 nm region). c Emission spectra of the ionic liquid at room temperature (RT) and 77 K, and excitation spectrum of Tb(IL)3, ranging from 400 nm to 525 nm. d Schematic diagram illustrating energy conversion processes involved in Tb(IL)3 under X-ray excitation. In addition to direct excitation of Tb3+, IL ligands transfer their singlet excitonic energy to the high-lying 5G2, 5L6, 5G6, and 5D3 states of Tb3+, while triplet energy is directly transferred to the 5D4 emitting state of Tb3+. e Radioluminescence spectra of 4 mm thick Tb(IL)3, PPO@toluene (64 mg mL−1), and CsPbBr3@toluene (0.18 mg mL−1) samples, prepared in highly transparent states by optimizing emitter concentrations. f Comparison of radioluminescence intensity as a function of X-ray dose rate for Tb(IL)3 and PPO@toluene.

To demonstrate the advantages of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators, we evaluated the scintillation performance of Tb(IL)3 by comparing its radioluminescence with existing liquid scintillators. To maintain transparency, traditional PPO was dissolved in toluene at a maximum concentration of 64 mg mL−1, while CsPbBr3 nanocrystals were dispersed in toluene at 0.18 mg mL−1. Unlike these systems, Tb(IL)3 scintillators maintained transparency regardless of concentration, allowing for a higher emitter density. As a result, their X-ray-excited radioluminescence photon counts are ~2.33 times higher than PPO@toluene and ~30.8 times higher than CsPbBr3@toluene, respectively (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 9). Furthermore, by benchmarking the integrated radioluminescence counts with a commercial Bi4Ge3O12 (BGO) scintillator, the light yield of the Tb(IL)3 is calculated to be ~2771 photons per MeV, significantly larger than a typical liquid scintillator 10% PPO@LAB ( ~ 100 photons per MeV) (Supplementary Fig. 10)35. This promising light yield is also attributed to their high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY, Supplementary Fig. 11). Moreover, the high atomic numbers of Tb and Br contribute to superior X-ray attenuation, surpassing commercial PPO@toluene across X-ray energies from 2 keV to 400 keV (Supplementary Fig. 12). This enhanced attenuation improves X-ray sensitivity, as evidenced by the steeper slope of the radioluminescence intensity curve as a function of X-ray dose rate (84.63 for Tb(IL)3 vs. 32.55 for PPO@toluene) (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 13). Consequently, Tb(IL)3 achieved an X-ray detection limit of 21.48 nGyair s−1, ~2.6 times lower than PPO@toluene (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Elimination of light scattering and self-absorption

Beyond their scintillation performance, lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators effectively mitigate self-absorption and light scattering. To assess these properties, we compared Tb(IL)3 with conventional PPO@toluene at equivalent molar concentrations (1 mmol PPO@3 mmol toluene) (Fig. 4a, b). PPO@toluene scintillators suffer from self-absorption due to the intrinsic bandgap emission of PPO, whereas the large Stokes shift of lanthanide f-f transitions minimizes self-absorption in Tb(IL)3 scintillators36,37. Dynamic light scattering analysis further revealed solute aggregation (~1.5 µm) in PPO@toluene due to solubility limits, resulting in noticeable light scattering and image blurring. In contrast, Tb(IL)3, as an intrinsic liquid, showed no aggregation, effectively eliminating light scattering.

a Comparison of transmission (T) and radioluminescence (RL) spectra for Tb(IL)3 and PPO@toluene. b Dynamic light scattering analysis of solute aggregation in Tb(IL)3 and PPO@toluene. Insets: Optical photos of a radiation symbol placed behind each scintillator (scale bars: 5 mm). Tb(IL)3 remains a homogeneous liquid with no detectable aggregation, allowing clear image transmission, while PPO@toluene exhibits significant scattering. c Modulation transfer function curve (MTF) of Tb(IL)3. Inset: A reference photograph used for MTF evaluation (scale bar: 8 mm). d X-ray imaging of a standard resolution test pattern. Scale bar: 1.5 mm. e, Grayscale analysis of the test pattern, showing resolved image resolutions from 14.3 to 20 lp mm−1. f X-ray imaging of real-world objects, including a metal pendant, an integrated circuit chip, and an electronic circuit board. Scale bars: 5 mm.

With reduced self-absorption and light scattering, lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators enable enhanced X-ray imaging performance. To evaluate their imaging capability, Tb(IL)3 was immobilized in a flat cuvette, simulating a solid scintillation film (Supplementary Fig. 15). The customized cuvette featured an optical distance of 1 mm, significantly thicker than typical solid scintillation films (nanometers to micrometers) designed for high spatial resolution (> 20 lp mm−1)38,39,40. In conventional scintillators, increased thickness leads to greater self-absorption and light scattering, degrading imaging quality. Notably, despite its 1 mm attenuation thickness, Tb(IL)3 achieved a spatial resolution of 26 lp mm−1 (Fig. 4c). Using this system, we demonstrated high-resolution X-ray imaging of a standard resolution test pattern, a metal pendant, and electronic chips (Figs. 4d–f). These results reveal the potential of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators for low-dose X-ray imaging, allowing increased attenuation thickness without sacrificing light output. Moreover, the relatively short lifetime decay (~686.67 μs) and negligible afterglow (40 ms to background level) highlight the potential of Tb(IL)3 liquid scintillator for X-ray imaging applications (Supplementary Fig. 16)41.

Evaluation of environmental stability and biocompatibility

We next investigated the stability of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators, which benefit from the non-volatility of ionic liquids42,43,44. This property prevents evaporation-related degradation, unlike traditional organic solvents. Tb(IL)3 scintillators showed negligible mass loss at both room temperature and 80 °C for 30 min, whereas PPO@toluene lost over 50% of its original mass even at room temperature due to toluene evaporation (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 17). This evaporation led to solute aggregation and fluctuations in radioluminescence, causing overexposure artifacts in continuous X-ray imaging. In contrast, the non-volatile nature of Tb(IL)3 ensures stable radioluminescence, enabling uninterrupted X-ray imaging for ~12 min without degradation (Figs. 5b, c, and Supplementary Fig. 18). Furthermore, Tb(IL)3 scintillators exhibit high stability under harsh radiation (151.2 Gy) when their operational temperature is below 80 °C (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20). In addition, Tb(IL)3 scintillators retain ~84.5% of their original radioluminescence intensity following a sudden increase in humidity (Supplementary Fig. 21). Of note, long-term operation under high humidity is not recommended due to the hygroscopic nature of the ionic liquid45.

a Weight loss of Tb(IL)3 and PPO@toluene over time at room temperature (~20 °C) and 80 °C. Insets: Optical images of both scintillators under different conditions. b Radioluminescence stability of Tb(IL)3 (top) and PPO@toluene (bottom) under on-off X-ray exposure at a dose rate of 278 µGyair s−1. c Comparison of X-ray imaging stability over 12 minutes. The circuit pattern imaged with PPO@toluene becomes distorted, while Tb(IL)3 maintains imaging clarity. Scale bar: 1 cm. d Environmental impact assessment using fresh leaves stored in a sealed petri dish. Leaves remain fresh in Tb(IL)3 for 31 hours but wither in PPO@toluene due to solvent toxicity. Scale bar: 3.5 cm. e Schematic and optical images of the MTT assay evaluating cell viability in Tb(IL)3 and PPO@toluene, with H2O as a reference. Scale bar: 9 mm. f MTT assay results showing absorbance at 570 nm. Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired student’s t-test (two-tailed with criteria of significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001) were calculated. Tb(IL)3 exhibits no significant toxicity, while PPO@toluene significantly reduces cell viability.

The non-volatility of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators also enhances their environmental friendliness and biocompatibility. To illustrate this, we examined leaf aging in sealed environments containing either Tb(IL)3 or PPO@toluene (Fig. 5d). After 31 h, Schefflera Actinophylla leaves remained fresh in the Tb(IL)3 environment, whereas those in PPO@toluene withered. Similar results were observed with Murraya leaves (Supplementary Fig. 22). This enhanced environmental compatibility suggests that Tb(IL)3 scintillators can be safely disposed of with minimal environmental impact.

To assess biocompatibility, we conducted a methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Fig. 5e, f), which measures mitochondria activity in living cells via the reduction of MTT to formazan, detectable at 570 nm absorbance (Supplementary Fig. 23)46. In well-plate experiments, cells exposed to the volatile PPO@toluene environment showed significantly lower absorbance, indicating reduced viability due to toluene evaporation. In contrast, Tb(IL)3, like H2O, preserved cell viability, confirming its non-toxic nature. These results highlight lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators as good candidates for low-toxic medical imaging and X-ray therapy.

Fluidity and shape-adaptivity for scintillation lens

We next demonstrated the potential of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators for uniform omni-angle X-ray detection and scintillation lenses. Conventional solid scintillation films are limited by their fixed geometry, restricting their detection angles. Planar scintillation films can only effectively detect X-rays at specific angles, whereas liquid scintillators can adapt to different shapes. However, existing solution-based liquid scintillators suffer from poor transparency, making uniform omni-angle detection challenging19. The high transparency and homogeneity of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators provides a solution, enabling uniform omni-angle detection by coupling them with transparent spherical containers (Supplementary Fig. 24).

Lenses, typically fabricated from homogeneous materials with a uniform refractive index, are critical for light manipulating47. Taking advantage of the transparency and fluidity of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators, we developed convex scintillation lenses to enhance X-ray imaging (Fig. 6). By filling a convex, hollow, transparent container with the liquid scintillator, we created a self-magnifying scintillation lens capable of in-situ enlarged X-ray imaging (Fig. 6a). Compared to common planar X-ray imaging, which struggles to resolve fine structures, our convex scintillation lens concurrently captures and magnifies X-ray images, allowing fine electrode features (~50 µm spacing), to be clearly distinguished (Fig. 6b, c and Supplementary Fig. 25).

a Schematic of the convex scintillation lens enabling in-situ enlarged X-ray imaging (IEI). b, c Comparison between conventional X-ray imaging and IEI of an electronic component. The zoomed-in region shows improved resolution with the convex scintillation lens. Grayscale intensity analysis comparing conventional zoom-in imaging (top) and IEI (bottom), demonstrating enhanced resolution with clearly resolved 50 µm electrode structures. Scale bars: 2.5 mm. d Schematic of the zoom scintillation lens, which is equipped with a digital auto-injector for liquid scintillator injection. e Adjustable focal length enabled by controlling step distance of auto-injector. Scale bars: 7.5 mm. f Working principle of the zoom scintillation lens, where different lens curvatures (R) alter the focal length, enabling tunable magnification for X-ray imaging. Right panel: X-ray images of chip pins captured at different magnifications. Scale bars: 5 mm.

To further enhance adaptability, we developed a zoom scintillation lens with tunable focal lengths for variable magnification (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 26). This was achieved by automatically injecting lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators into a container with transparent, flexible, and stretchable capping films. Adjusting the injected liquid volume controls internal pressure, dynamically modifying the convexity of the films and thus the focal length (Fig. 6e). Optical simulations were used to determine the effective focal length of the zoom lens, assuming a scintillating light wavelength of 555 nm and a refractive index of 1.493 for Tb(IL)3. By varying the lens cross-sectional radius (R), we achieved a tunable focal length ranging from ~2 cm to infinity (Fig. 6f). This zoom scintillation lens demonstrated adjustable magnification up to ~3.5\(\times\) for X-ray imaging of chip pins (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28).

In summary, this work introduces lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators as a class of intrinsic liquid scintillators, offering a scattering-free, self-adaptive, and highly transparent platform for high-resolution X-ray imaging. Unlike conventional solid and solution-based scintillators, which suffer from light scattering, self-absorption, and geometric rigidity, our approach utilizes strong in-situ coordination between lanthanide ions and ionic liquid ligands to create a homogeneous, non-volatile, and shape-adaptable liquid scintillator. At the fundamental level, this study reveals a scintillation mechanism driven by dual-channel energy transfer involving both singlet and triplet energy transfer processes, where ionic liquid ligands efficiently transfer and recycle excitonic energy to lanthanide emitters, significantly enhancing radioluminescence. This insight provides a framework for designing liquid-phase scintillators with optimized energy transfer pathways. By harnessing their fluidic and adaptive properties, we demonstrate convex and zoom scintillation lenses that enable omni-angle X-ray detection and tunable magnification, capabilities that were previously unattainable with solid scintillators. These results highlight the potential of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators for advanced X-ray imaging applications, including microfluidic radiation sensors, AI-assisted high-contrast imaging, and low-dose medical diagnostics.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

1-Methylimidazole (99%), 2-bromoethanol (95%), 1,4-butanesultone (> 99%(GC)), europium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Eu(NO3)3•6H2O, 99.99% metals basis), terbium(III) nitrate pentahydrate (Tb(NO3)3•5H2O, 99.9% metals basis), and ethyl acetate (anhydrous 99.8%) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Ltd. Acetonitrile (ACN, anhydrous 99.8%) and acetone (ACS reagent, > 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Synthesis of lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators

Lanthanide (Ln)-ionic liquid (IL) scintillators, Ln(IL)3, were synthesized through a two-step process. First, 30 mmol 1-methylimidazole (2.46 g) and 30 mmol 2-bromoethanol (3.744 g) were mixed and heated at 67 °C for ~24 h with magnetic stirring in an oil bath. The resulting product (3.102 g) was then combined with 37.5 mmol 1,4-butanesultone (5.106 g) in 75 mL acetonitrile and reacted at 80 °C for 18 h in a reflux system to obtain ILs. After reaction, the ILs were washed three times with ethyl acetate. Finally, 1 mmol Ln(NO3)3•xH2O (Ln=Tb or Eu) was mixed with 3 mmol ILs (0.897 g) in 1.5 mL acetone, stirred at room temperature for 30 min, and then rotary evaporated at 40 °C to remove residual solvents, yielding the final Ln(IL)3 scintillators.

Characterization

Optical transmission spectra were acquired with a commercial spectrophotometer (Cary 7000, Agilent). Molecular aggregation behavior in liquid was assessed by dynamic light scattering (Malvern Zeta-sizer). X-ray-excited radioluminescence spectra were collected with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (FS5 and FS1000, Edinburgh) coupled to an X-ray source (4 W, Amptek). Steady-state photoluminescence and excitation spectra were recorded using an Edinburgh FLS-980 spectrophotometer. X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements at the Tb L3 edge were conducted on the 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained using an AVATAR360 spectrometer (Nicolet). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz spectrometer using D2O as the solvent. The refractive index was determined using an Abbe refractometer (1WAJ), and viscosity was measured with a rotational rheometer (Physica MCR-92).

Toxicity assay

For cytotoxicity assessment, 100 µL of the Tb(IL)3, PPO@toluene, or H2O was introduced into the center of each well in a 96-well plate. HEK293T (ATCC) cells were seeded surrounding the test region at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells per well and cultured for 48 h at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, the culture medium was discarded, and 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg mL−1) was added to each well. The cells were then incubated for another 4 h to allow metabolically active cells to reduce MTT into formazan crystals. Dimethyl sulfoxide was subsequently added to dissolve the crystals, and after standing for 20 min at room temperature, the absorbance at 570 nm was recorded using a microplate reader.

Optical simulation

The simulation was performed based on the modeling of electromagnetic wave propagation with a ray-tracing approach. The wavelength of incident light was set to 555 nm. The refractive index (n) of the scintillator lens is 1.493. The cross-sectional radius (R) is set to 0.75 cm and 0.375 cm, respectively. The effective focal length is determined through ray tracing.

Calculation

Geometry optimizations were conducted within the framework of density functional theory (DFT) using the dispersion-corrected hybrid PBE0-D3(BJ) functional. The 6-311 G** basis set was applied to all nonmetal atoms, while the Stuttgart small-core pseudopotential (MWB54) basis set was used for rare-earth elements. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations were carried out using the atom-centered density matrix propagation (ADMP) method. Excited-state electronic properties were investigated via time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) calculations. All computations were performed using the Gaussian 16 package, employing the polarizable continuum model to account for solvation effects in C8H15BrN2O3S solvent48,49. Fuzzy bond order analyses were performed using the Multiwfn program50.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file or upon request from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Du, X. et al. Efficient and ultrafast organic scintillators by hot exciton manipulation. Nat. Photonics 18, 162 (2024).

He, T. et al. Copper iodide inks for high-resolution X-ray imaging screens. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 1362 (2023).

Gao, C. et al. Synthetic data accelerates the development of generalizable learning-based algorithms for X-ray image analysis. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 294 (2023).

Chapman, H. N. & Nugent, K. A. Coherent lensless X-ray imaging. Nat. Photonics 4, 833 (2010).

Cao, C. et al. Emerging X-ray imaging technologies for energy materials. Mater. Today 34, 132 (2020).

Zhu, W. et al. Low-dose real-time X-ray imaging with nontoxic double perovskite scintillators. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 112 (2020).

Gandini, M. et al. Efficient, fast and reabsorption-free perovskite nanocrystal-based sensitized plastic scintillators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 462 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Light management of metal halide scintillators for high-resolution X-ray imaging. Adv. Mater. 36, 2303738 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Ultrastable and flexible glass−ceramic scintillation films with reduced light scattering for efficient X−ray imaging. NPJ Flex. Electron. 8, 31 (2024).

Gan, N. et al. Organic phosphorescent scintillation from copolymers by X-ray irradiation. Nat. Commun. 13, 3995 (2022).

Li, B. et al. Zero-dimensional luminescent metal halide hybrids enabling bulk transparent medium as large-area X-ray scintillators. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102793 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Highly resolved and robust dynamic X-ray imaging using perovskite glass-ceramic scintillator with reduced light scattering. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003728 (2021).

Luo, J., Wei, J., Zhang, Z., He, Z. & Kuang, D. A melt-quenched luminescent glass of an organic–inorganic manganese halide as a large-area scintillator for radiation detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202216504 (2023).

Yi, L., Hou, B., Zhao, H., Tan, H. & Liu, X. A double-tapered fiber array for pixel-dense gamma-ray imaging. Nat. Photonics 17, 494 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Oriented-structured CsCu2I3 film by close-space sublimation and nanoscale seed screening for high-resolution X-ray imaging. Nano Lett. 21, 1392 (2021).

Roques-Carmes, C. et al. A framework for scintillation in nanophotonics. Science 375, 837 (2022).

Mesquita, C. H., Fernandes Neto, J. M., Duarte, C. L., Rela, P. R. & Hamada, M. M. Radiation damage in scintillator detector chemical compounds: a new approach using PPO-Toluene liquid scintillator as a model. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 49, 1669 (2002).

Cho, S. et al. Hybridisation of perovskite nanocrystals with organic molecules for highly efficient liquid scintillators. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 156 (2020).

Lian, H. et al. Aqueous-based inorganic colloidal halide perovskites customizing liquid scintillators. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304743 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Ultrabright molecular scintillators enabled by lanthanide-assisted near-unity triplet exciton recycling. Nat. Photonics 19, 71 (2025).

Ramos, T. J. S., Berton, G. H., Júnior, S. A. & Cassol, T. M. Photostable soft materials with tunable emission based on sultone functionalized ionic liquid and lanthanides ions. J. Lumin. 209, 208 (2019).

Tang, S., Babai, A. & Mudring, A.-V. Europium-based ionic liquids as luminescent soft materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 7631 (2008).

Lei, Z., Chen, B., Koo, Y. & MacFarlane, D. R. Introduction: ionic liquids. Chem. Rev. 117, 6633 (2017).

Morad, V. et al. Luminescent lead halide ionic liquids for high-spatial-resolution fast neutron imaging. ACS Photonics 8, 3357 (2021).

Ramos, T., Viana, R., Schaidhsuer, L., Cassol, T. & Junior, S. Thermoreversible luminescent ionogels with white light emission: an experimental and theoretical approach. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 10934 (2015).

Rodrigues, R. V. et al. Oxysulfate/oxysulfide of Tb3+ obtained by thermal decomposition of terbium sulfate hydrates under different atmospheres. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 122, 765 (2015).

Niu, T. et al. Phase-pure α-FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells via activating lead-iodine frameworks. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309171 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Fully screen-printed perovskite solar cells with 17% efficiency via tailoring confined perovskite crystallization within mesoporous layer. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302654 (2023).

Yang, D., Li, H. M. & Li, H. R. Recent advances in the luminescent polymers containing lanthanide complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 514, 215875 (2024).

Kukinov, A. A. et al. X-ray excited luminescence of organo-lanthanide complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 16288 (2019).

Jares-Erijman, E. A. & Jovin, T. M. FRET imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1387 (2003).

Lushchik, C. H. B. Chapter 8-Creation of Frenkel defect pairs by excitons in alkali halides. Mod. Probl. Condens. Matter Sci. 13, 473 (1986).

Feng, G. et al. Free and bound states of ions in ionic liquids, conductivity, and underscreening paradox. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021024 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Organic phosphors with bright triplet excitons for efficient X-ray-excited luminescence. Nat. Photonics 15, 187 (2021).

Caravaca, J., Land, B. J., Yeh, M. & OrebiGann, G. D. Characterization of water-based liquid scintillator for Cherenkov and scintillation separation. Eur. Phys. J. C. 80, 867 (2020).

Cho, S. et al. Optimal design and characteristic analysis of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals hybridized with 2,5-diphenyloxazole molecules for UV and X-ray detection. Mater. Today Chem. 35, 101851 (2024).

Qin, X., Liu, X., Huang, W., Bettinelli, M. & Liu, X. Lanthanide-activated phosphors based on 4f-5d optical transitions: theoretical and experimental aspects. Chem. Rev. 117, 4488 (2017).

Wu, H. et al. One-dimensional scintillator film with benign grain boundaries for high-resolution and fast X-ray imaging. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh1789 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. High-confidentiality X-ray imaging encryption using prolonged imperceptible radioluminescence memory scintillators. Adv. Mater. 35, 2309413 (2023).

Yuan, J. et al. Highly efficient stable luminescent radical-based X-ray scintillator. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27095 (2023).

Luo, Z. et al. A new promising new choice for modern medical CT scanners: cerium-doped gadolinium yttrium gallium aluminum garnet ceramic scintillator. Appl. Mater. Today 35, 101986 (2023).

Chao, L. et al. Room-temperature molten salt for facile fabrication of efficient and stable perovskite solar cells in ambient air. Chem 5, 995 (2019).

Miao, W. & Chan, T. H. Ionic-liquid-supported synthesis: a novel liquid-phase strategy for organic synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 897 (2006).

Welton, T. Ionic liquids in catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 2459 (2004).

Cuadrado-Prado, S. et al. Experimental measurement of the hygroscopic grade on eight imidazolium based ionic liquids. Fluid Phase Equilibr 278, 36 (2009).

Guo, R., Liu, Q., Wang, W., Tayebee, R. & Mollania, F. Boron nitride nanostructures as effective adsorbents for melphalan anti-ovarian cancer drug. Preliminary MTT assay and in vitro cellular toxicity. J. Mol. Liq. 325, 114798 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Tunable liquid lenses: emerging technologies and future perspectives. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2300274 (2023).

Frisch M. J. et al., Gaussian 16, revision a. 03, gaussian, inc., wallingford ct., Gaussian16 (Revision A. 03), (2016).

Bernales, V. S., Marenich, A. V., Contreras, R., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models for ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 9122 (2012).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation, and the Prime Minister’s Office of Singapore under its Competitive Research Program (CRP Award No. NRF-CRP23-2019-0002, X.L.) and NRF Investigatorship Programme (Award No. NRF-NRFI05-2019-0003, X.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62288102, X.Q.), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2024J01303, X.Q.). We also thank Y. Gu, Y. Liu, and J. Xu for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Q., X.Q., and X.L. conceived and designed the experiments. X.L. supervised the project. J.Q. and C.G. prepared scintillators and conducted experiments and characterizations. M.C. fabricated liquid lenses. C.C., L.C., and Y.C. offered XAFS tests and analysis. W.C. and X.Q. conducted quantum mechanical calculations. H.J. and Q.C. assisted with X-ray measurements. J.Q., X.Q., and X.L. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lei Lei and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, J., Gu, C., Chen, M. et al. Scattering-free lanthanide-ionic liquid scintillators for high-resolution and adaptive X-ray imaging. Nat Commun 16, 11609 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66754-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66754-0