Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CART) has revolutionized the treatment of patients with refractory/relapsed large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL). Limited biopsy data indicate that a higher activated CD8+ T-cell density is associated with tumor response. However, tumor biopsies fail to capture the systemic kinetics of CD8+ T-cells. Therefore, we conducted an exploratory phase 2 single-arm trial utilizing a zirconium-89-labeled one-armed anti-CD8α antibody (89ZED88082A) to enable whole-body imaging of CD8+ T-cells through positron emission tomography (PET) (NL9034; EUCTR2020-004749-35-NL). Imaging analysis was performed in 23 patients with R/R LBCL, encompassing 251 lesions before (pre-CART) and after infusion (post-CART). Primary endpoint was to determine the whole-body distribution of the tracer in normal and tumor tissues before and after CART. 89ZED88082A uptake in normal tissues varied over time. Tumor uptake was heterogeneous between and within patients. At the lesion level, higher pre-CART 89ZED88082A tumor uptake was associated with higher post-CART tumor uptake at day +2. As secondary endpoints, no tracer-related side effects occurred and above median pre-CART 89ZED88082A tumor uptake was associated with a longer time to progression, while lesions that relapsed exhibited consistently low uptake. Exploratory analysis showed a 42% tumor volume reduction from pre-CART to post-CART day +7. In conclusion, 89ZED88082A has the potential to detect lesions at risk for progression and worse patient outcome, emphasizing the critical role of a CD8-permissive tumor microenvironment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autologous CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of patients with refractory or relapsed large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL), increasing the 2-year overall survival rate from 20% to 54% in the third line1. Consequently, as the target antigen recognition domain of the CAR T-cell can be altered, this therapeutic approach has been explored in other hematologic and even solid malignancies2,3,4,5. Yet, its full potential is limited by poor CAR T-cell tumor trafficking, short persistence, intrinsic tumor resistance, and an immunosuppressive microenvironment2,6. Despite considerable efforts, the (CAR) T-cell dynamics before and after infusion and the tumor response shortly following infusion remain insufficiently characterized to date.

The current understanding of CD8+ (CAR) T-cell behavior during CAR T-cell therapy is primarily derived from single-lesion biopsies. These biopsy data showed that a higher pre-treatment tumor density of CD8+ T-cells with an activated phenotype and a relatively increased tumor influx of CD8+ T-cells post-treatment were associated with objective tumor response7,8. Remarkably, in post-treatment samples, only 1–12% of the tumor-infiltrating T-cells expressed the CAR, indicating the majority consisted of bystander T-cells. These, like their CAR+ counterparts, exhibited signs of activation8. Activated bystander-phenotype-positive T-cells were capable of anti-leukemic cytotoxicity in an in vitro model, suggesting a potential role for this subset in enhancing the CAR T-cell response9,10.

However, a single-lesion biopsy fails to capture both the whole-body systemic kinetics and heterogeneity of the CD8 + T-cell infiltration in all tumor lesions or the temporal dynamics of the tumor response in the patient before and during CAR T-cell therapy.

In this work, we conduct a single-center trial using a zirconium-89 (89Zr)-labeled one-armed anti-CD8α antibody (89ZED88082A) for the non-invasive whole-body visualization of CD8+ T-cells by positron emission tomography (PET) in patients with R/R LBCL9. To study the distribution of CD8 + T-cells in normal organs and tumor tissues both before (pre-CART) and after CAR T-cell therapy (post-CART), 89ZED88082A-PET scans are performed first in the period between apheresis and lymphodepletion (LD) and again within the first week after axicabtagene ciloleucel infusion. Three patient cohorts are studied at progressively shorter intervals between CAR T-cell infusion and post-CART imaging, from post-CART day +7, to day +5, to day +2. We show that 89ZED88082A tumor uptake is heterogeneous between and within patients. In addition, higher pre-CART tumor uptake is associated with higher post-CART day +2 tumor uptake. Furthermore, we demonstrate that above-median 89ZED88082A tumor uptake before CAR T-cell therapy is predictive for lesions at risk of progression and, as a result, worse patient outcome, confirming the importance of an immune-permissive tumor microenvironment in CAR T-cell therapy.

Results

Trial population and safety

From June 2021 to October 2023, 35 consecutive patients were assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1a). Of the 27 patients included, three patients withdrew informed consent before the first tracer infusion. One patient was non-evaluable due to CAR T-cell production failure. Twenty-three patients underwent pre- and post-CART 89ZED88082A administrations (37 mBq, 10 mg) and subsequent PET scans in three consecutive cohorts (Table 1). Cohort 1 consisted of seven patients, and cohorts 2 and 3 each consisted of eight patients. The median age of patients was 64 years, ranging from 39–80. Among them, 10 patients (43%) were diagnosed with diffuse LBCL, not otherwise specified (DLBCL NOS), while six patients (26%) had transformed follicular lymphoma (tFL). Additionally, five patients (22%) were classified with high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and two patients (9%) with EBV-positive DLBCL. Before apheresis, 17 patients (74%) had stage III–IV disease, including four (17%) with secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Eighteen patients (78%) received bridging therapy to reduce tumor burden before CAR T-cell infusion and/or disease-related clinical symptoms, including radiotherapy (n = 10, 44%), systemic therapy (n = 6, 26%), or a combination (n = 2, 9%). All patients were treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta®), an autologous CART cell product generated ex vivo by retroviral transduction and comprising a CD19-directed CAR construct, the complete transmembrane and intracellular signaling domains of CD28, and the cytoplasmic portion of CD3-ξ.

a CONSORT flow diagram summarizing patient selection and inclusion. A total of 35 patients were assessed for eligibility; six declined participation, and two were excluded for other reasons. Of the 27 included patients, three patients withdrew consent, and one patient was non-evaluable due to CAR T-cell production failure. This resulted in 23 evaluable patients with the following cohort distribution: cohort 1 (n = 7), 2 (n = 8), and 3 (n = 8). b Schematic of the study design visualizing the trajectory for all the 3 cohorts.

In the first cohort, post-CART 89ZED88082A-imaging was performed +7 days after CAR T-cell infusion. As ultrasound-guided biopsies revealed an unexpectedly rapid tumor response at day +7 post-CART, the protocol was amended to perform 89ZED88082A-PET at day 5 in cohort 2 to optimally study the (CAR) T-cell influx in the tumor lesions and subsequently in cohort 3 at days +2, +4, and +7 after CAR T-cell infusion (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 4). The median time between pre-CART and post-CART imaging was 30 days for cohort 1 (day +7), 24 days for cohort 2 (day +5), and 21 days for cohort 3 (day +2). To exclude the influence of tracer kinetics on SUVmean and SUVpeak values, the presented analyses include 89ZED88082A uptake measures extracted from PET scans that were performed two days after 89ZED88082A-tracer infusion, unless otherwise noted (e.g., for cohort 3, only day +2 after CAR T-cell infusion).

No side effects associated with 89ZED88082A were observed (secondary endpoint). Adverse events of grade ≥3 due to CAR T-cell therapy were consistent with reports from previous studies10,11 (Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Normal tissue distribution

Primary endpoint of this study was to determine the whole-body distribution of the tracer in normal tissue and tumor lesions before and after CAR T-cell therapy. Regarding the normal tissue distribution, the highest uptake was observed in the spleen, which was lower post-CART day +7 than pre-CART (mean standardized uptake value (SUVmean) 19.6, 95%CI [14.6–24.7] and 26.1, 95%CI [23.3–28.9], respectively; P = 0.06; Fig. 2a–f, Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, lower uptake in the liver and small intestine was observed post-CART day +7 compared to pre-CART (SUVmean 3.6, 95%CI [3.1–4.1] to 2.2, 95%CI [1.4–3.0]; P < 0.01 and 1.6 to 1.1; P = 0.01, respectively), along with decreased bone marrow uptake (SUVmean 2.4, 95%CI [2.0–2.8] to 1.8, 95%CI [1.1–2.5]; P = 0.07; Fig. 2g). For healthy lymph nodes, the geometric mean SUVmean over time ranged from 0.45 to 0.72 (all P > 0.40; Fig. 2h). After CAR T-cell infusion, the brain showed an increase in 89ZED88082A uptake from pre-CART to day +5 (SUVmean 0.18, 95%CI [0.12–0.24] to 0.35, 95%CI [0.26–0.44]; P < 0.01). Blood pool uptake showed an increase from pre-CART to day +2, before declining to pre-CART values again. To investigate, as a secondary endpoint, whether blood pool 89ZED88082A uptake reflected circulating CD8+ T-cell levels and potential CAR T-cell expansion, we compared 89ZED88082A uptake to CD8 DNA levels from venous blood samples. Pre-CART or post-CART SUVmean in the aorta did not correlate to the circulating CD8+ T-cells (n = 18; P = 0.76 and n = 4; P = 0.65, respectively). This most likely is caused by the availability of unbound 89ZED88082A in the circulation, compromising PET-sensitivity in the vascular components. Levels of unbound 89ZED88082A are likely to be higher at day +2 due to the short timeframe after lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CAR T-cell infusion, resulting in a limited recovery in T-cell levels and CAR T-cell expansion.

a Maximum intensity projection of pre-CART 89ZED88082A PET scan. A video version is available in Supplementary Movie 1. b–e The same patient’s transversal 89ZED88082A PET/CT views visualizing uptake in different areas. The arrow in (e) indicates this patient’s tumor lesion. f–h Estimated 89ZED88082A tissue uptake presented as geometric mean SUVmean (lines and dots) with 95% confidence interval bands over time at pre-CART, and days +2, +5 and +7 post-CART (n = 23 patients), resulting from linear mixed models based on pre-CART and post-CART days +2 (cohort 3; n = 8 patients), +5 (cohort 2; n = 8 patients), and +7 (cohort 1; n = 7 patients). CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. LD, lymphodepletion. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

89ZED88082A uptake in tumor tissue before CAR T-cell therapy

With respect to the primary endpoint, we next evaluated the whole-body distribution of the tracer in tumor lesions before and after CAR T-cell therapy. In 23 patients, 251 tumor lesions were included for PET analysis, which revealed that peak and maximum standardized uptake values (SUVpeak and SUVmax) were highly correlated (r: 0.95; Supplementary Fig. 2). Thereafter, SUVpeak was considered as the primary 89ZED88082A tumor uptake metric. Lesions were generally small in size (median diameter 1.8 cm [Interquartile range (IQR) 1.3−2.9]), and the median number of lesions per patient was 11 [IQR 3–14]. A partial volume correction (PVC) was applied to all lesions to compensate for the systematic underestimation of the SUVpeak in small lesions, as pre-defined in the statistical analysis plan (Supplementary Fig. 3). The median per patient geometric mean SUVpeak pre-CART was 4.8 [IQR 3.0–6.4]. No substantial differences were observed between the cohorts in the median number of lesions per patient, lesion diameter, or geometric mean SUVpeak.

Heterogeneity in tumor tracer uptake was evident across and within individual patients (Fig. 3a, c), with a higher uptake in patients with EBV+ compared to EBV- DLBCL (geometric mean SUVpeak 11.3, 95%CI [5.6–22.6] vs 4.1, 95%CI [3.2–5.1]; P < 0.01; Fig. 3d). EBV+ DLBCL is associated with a higher presence of CD8+ T-cells in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, resulting in a dysfunctional exhausted T-cell population12. Therefore, these patients (n = 2) were excluded for further tumor tissue analyses.

a, b Pre- and post-CART uptake (unadjusted SUVpeak) in 251 lesions of 23 patients, ordered by geometric mean SUVpeak per patient, visualizing lesion size (diameter) and site (nodal/extranodal). Post-CART uptake was measured at days +2 (cohort 3; n = 8 patients, 79 lesions), +5 (cohort 2; n = 8 patients, 63 lesions) and +7 (cohort 1; n = 7 patients, 109 lesions) after CAR T-cell therapy. Both pre- and post-CART 89ZED88082A PET/CT imaging was performed 2 days after tracer injection. Black horizontal lines depict the geometric mean SUVpeak per patient. c Axial views of 89ZED88082A PET/CT imaging representing heterogeneity within a patient at pre-CART, showing limited (i), intermediate (ii), and high (iii) uptake in tumor lesions. d Violin plot of pre-CART SUVpeak in EBV+ (n = 37 lesions) and no EBV+ (n = 214 lesions) LBCL tumor lesions (exact P = 0.00469). e Violin plot of pre-CART SUVpeak in nodal (n = 148) and extranodal (n = 62; spleen excluded) lesions. f Violin plot of pre-CART SUVpeak in nodal and several extranodal sites. g Violin plot of pre-CART lesion volume (mL) in non-irradiated (n = 57) and target radiotherapy (n = 20) lesions of patients undergoing bridging radiotherapy (n = 9 patients; exact P = 9.9 × 10−6). h Violin plot of pre-CART SUVpeak in non-irradiated (n = 57) and target radiotherapy (n = 20) lesions. d–h Black vertical lines are 95% CI of the geometric mean; white dots are the geometric means. P-values were obtained from linear mixed models that accounted for clustering within patients, using a two-sided Wald test with restricted maximum likelihood for factors with three or more levels (h), and a likelihood ratio test with maximum likelihood for two-level factors (d–g). e–h Analyses based on non-EBV+ LBCL patients, with 214 lesions in 21 patients. Adj., volume-adjusted. CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

89ZED88082A tumor uptake did not differ between nodal and extranodal lesions (geometric mean SUVpeak 3.8, 95%CI [2.9–5.0] vs 4.2, 95%CI [3.0–5.6]; P = 0.58; Fig. 3e). Spleen lesions (n = 4) were not considered for this specific analysis to more accurately estimate nodal and extranodal lesion 89ZED88082A uptake, as spleen tissue exhibits a distinct uptake pattern compared to other lesion sites, potentially because of spill-in effects from high background uptake. Geometric mean SUVpeak in nodal lesions ranged from 2.9 to 7.0 (P = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 4a), and in all nodal and extranodal lesion locations from 3.1 to 38.8 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Interestingly, brain lesions showed similar tracer uptake (SUVpeak 3.2, 95%CI [1.7–5.9]) as other extranodal lesion sites (P = 0.36; Fig. 3f).

To assess the effect of bridging radiation therapy on the CD8+ T-cell infiltration within the tumor as a secondary endpoint, we compared irradiated and non-irradiated lesions in patients receiving radiotherapy (n = 9; 77 lesions). Lesions receiving target dose radiation had pre-CART a larger volume than non-target lesions (21.3 mL (n = 20) vs 2.4 mL (n = 57); P < 0.01; Fig. 3g). Geometric mean pre-CART SUVpeak (volume-adjusted) did not differ between target radiotherapy lesions and non-irradiated lesions (3.9, 95%CI [2.5–6.2] and 4.3, 95%CI [2.9–6.5], respectively; P = 0.61; Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 5).

89ZED88082A in tumor lesions from pre-CART to post-CART

Among the 21 evaluable patients, 89ZED88082A tumor uptake first declined from a geometric mean SUVpeak of 4.0 (95%CI [3.3–4.8]) pre-CART to 2.4 (95%CI [1.8–3.3]) post-CART day +5, whereafter an increasing trend to 3.6 (95%CI [2.8–4.7]) post-CART day +7 was observed (P < 0.01; Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 6a). Within and between patients, tumor heterogeneity was observed for post-CART SUVpeak, and in the dynamics from pre-CART to post-CART as well (Fig. 3b, Fig. 4b, d and Supplementary Movie 2).

a Estimated tumor uptake presented as geometric mean SUVpeak and volume over time (lines and dots) with 95% confidence bands, resulting from linear mixed models based on pre-CART (full cohort without EBV+ LBCL patients; n = 21 patients, 214 lesions) and post-CART days +2 (cohort 3; n = 8 patients, 79 lesions), +5 (cohort 2; n = 7 patients, 49 lesions) and +7 (cohort 1; n = 6 patients, 86 lesions) values. b Transversal views of 89ZED88082A PET/CT scans of para-iliac tumor lesions pre- and post-CART day +2. Arrows indicate regions of tumor tracer uptake, with corresponding CT images shown to the right. c Lesion-level correlation between pre- and post-CART day +2 (cohort 3; n = 8 patients, 79 lesions; exact P = 4.1 × 10−12) SUVpeak. The red line shows the linear mixed model regression fit with 95% confidence interval bands. P-value is based on a likelihood ratio test under maximum likelihood. d 89ZED88082A PET/CT transversal views of representative patient (cohort 3) with a mediastinal tumor lesion at pre-CART, post-CART days +2, +4, and +7. Adj., volume-adjusted. CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. LD, lymphodepletion. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Tumor lesions in cohort 3 were used to study the primary objective at the lesion-level, the relation of CD8+ T-cell infiltration between pre-CART and post-CART day +2 after CAR T-cell infusion. A higher pre-CART SUVpeak was associated with a higher post-CART SUVpeak (β = 0.71, 95%CI [0.54–0.88] (log-scale); P < 0.01), where 47% of the variability in the post-CART SUVpeak was explained by the pre-CART SUVpeak (Fig. 4c). Additionally, in cohort 3, specific 89ZED88082A tumor uptake pre-CART was also present post-CART day +2, +4, and +7 (Fig. 4d). To illustrate pre- and post-CART uptake among different patient tumor responses, a case series is represented in Supplementary Fig. 7.

As an explorative analysis in addition to the above-described primary endpoint analysis, we aimed to determine the observed rapid volume reduction post-CART, which hampered the feasibility of biopsies. Delineated tumor volume across all lesions reduced from pre-CART to post-CART day +7 by 42% (P = 0.02; Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 6b).

In the available pre-CART tumor biopsies from seven patients (one collected before 89ZED88082A tracer infusion and six after), analyzed as a secondary endpoint, localized CD8+ T-cell expression as determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) correlated slightly with the SUVpeak of the same lesion (Pearson correlation 0.65; P = 0.11; Fig. 5c). In tissue samples, Kist de Ruijter et al. already confirmed the correlation of CD8+ T-cell density by IHC and autoradiography signal magnitude in tumor tissues9. In our cohort, 89ZED88082A autoradiography signal matched visually with performed CD8+ IHC in three patients (pre-CART n = 2; post-CART n = 1; Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 8). Limited CAR T-cell infiltration was observed in this post-CART biopsy.

a, b Pre- and post-CART visualizations of autoradiography signal of 89ZED88082A uptake and CD8, CD19, and CAR IHC staining, as measured by biopsy. c Pearson correlation between percentage pre-CART tumor CD8+ cells measured by biopsy and 89ZED88082A tumor SUVpeak (n = 7 lesions from 7 patients). P-values is based on a two-sided t-test for Pearson correlation coefficients. Adj., volume-adjusted. CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Clinical outcome and CAR T-cell related toxicities

Additional secondary endpoints of this study included the association between 89ZED88082A uptake and the response to CAR T-cell therapy, CAR T-cell related toxicity and cytokine levels.

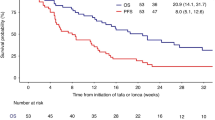

The median follow-up was 8.8 months (range 2.4–30.0), with the data cut-off on March 26, 2024. The overall response rate in 21 patients was 95%, 16 (76%) experienced a complete response (CR), four had a partial response (PR), and one progressive disease (PD). The 4.3 (95%CI [3.3–5.7]) geometric mean SUVpeak of the tumor lesions in patients who obtained a CR was 23% higher than the geometric mean SUVpeak 3.5 (95%CI [2.2–5.6]) in patients with no CR (P = 0.36; Fig. 6b). When considering only PD or disease-related death as events, patients with an above-median pre-CART geometric mean 89ZED88082A tumor uptake (≥3.9) had a longer time to progression (TTP) than patients with below median uptake (P = 0.02; Fig. 6a). These patients with an above-median pre-CART geometric mean 89ZED88082A tumor uptake had a fivefold lower hazard of progression compared to patients with a below-median uptake (hazard ratio (HR) 0.21 95%CI [0.04–0.80]; P = 0.02). Although two patients died from infections, the association between pre-CART 89ZED88082A uptake ( ≥ 3.9) and progression-free survival (PFS) was comparable to TTP (P = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 9), with an HR of 0.25 (95%CI [0.06–0.82]; P = 0.02). For overall survival, above-median pre-CART geometric mean 89ZED88082A tumor uptake showed a similar pattern (P = 0.25; Fig. 6a), with an HR of 0.46 (95%CI [0.11–1.75]; P = 0.26).

a Time to progression and overall survival curves (in months) according to pre-CART geometric mean SUVpeak lower and higher than the median (3.9). P-values were derived using the log-rank test. b Violin plot representing the relationship of pre-CART SUVpeak in patients achieving complete response or not (CR: 145 lesions in 16 patients, no CR: 69 lesions in five patients). c Violin plot representing the relationship of pre-CART tumor SUVpeak in patients with CRS grade ≥2 (150 lesions in 11 patients) and patients with CRS grade <2 (64 lesions in 10 patients). d, e Violin plot representing the relationship in pre-CART (d) and post-CART (e) brain SUVmean between patients with ICANS grade ≥2 (n = 12) and patients with ICANS grade <2 (n = 9). b–e Black vertical lines are the geometric mean 95% CI; white dots are the geometric means. P-values were obtained from linear mixed models that accounted for clustering within patients, using a likelihood ratio test with maximum likelihood. Adj., volume-adjusted. CART, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. CR, complete remission. CRS, cytokine release syndrome. geom, geometric. ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Higher pre-CART 89ZED88082A tumor uptake at the lesion level was associated with a longer time to progression, with an HR of 0.52 per 10-unit increase in SUVpeak (95%CI [0.19–1.49]; P = 0.22). Additionally, in cohort 3, both pre- and post-CART 89ZED88082A uptake in almost all of the relapsed lesions was below median uptake (n = 6 out of 7 lesions in 3 patients; SUVpeak < 3.9 for pre-CART; SUVpeak < 2.9 for post-CART; Supplementary Table 3).

Metabolic active tumor volume (MATV) at baseline and before lymphodepleting therapy, determined on 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) PET/CT scans, is a known predictor for CAR T-cell outcome13,14. Therefore, we aimed to allow a comparison of MATV to 89ZED88082A uptake. Using previously determined cut-offs (480 mL) to identify patients with a high MATV before lymphodepleting therapy (approximately 6 days before infusion)15, these patients had a shorter time to progression than patients with a low MATV (P = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 10a–c). There was no evident relation between pre-CART MATV and pre-CART 89ZED88082A SUVpeak (β = 0.0, 95%CI [−0.05–0.6]; P = 0.96; Supplementary Fig. 10d).

Twelve patients (57%) experienced grade ≥2 CAR T-cell-related cytokine release syndrome (CRS), of which nine (43%) had also grade ≥2 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). ICANS grade ≥2 was observed in three patients (14%). Tocilizumab and steroids were administered in eleven patients (52%), whereas tocilizumab and steroids alone were prescribed in respectively four (19%) and three (14%) patients. Pre-CART tumor SUVpeak did not differ between patients with CRS grade <2 and grade ≥2 (4.2 95%CI [2.9–6.2] and 4.0 95%CI [2.9–5.5], respectively; P = 0.84; Fig. 6c). Pre-CART SUVmean of the brain tissue was 0.16 (95%CI [0.07–0.25]) in patients with ICANS grade <2, and 0.22 (95%CI [0.01–0.42]) in those with ICANS grade ≥2 (P = 0.30; Fig. 6d). No substantial differences between patients with ICANS grade <2 and ≥2 were observed for post-CART brain SUVmean (0.29 95%CI [0.18–0.40] and 0.33 95%CI [0.08–0.59], respectively; P = 0.56; Fig. 6e).

Analysis of pre-CART 89ZED88082A uptake in relation to cytokine levels over time showed no clear pattern (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Discussion

Capturing the dynamics of the CD8+ T-cell distribution before and during CAR T-cell therapy is essential in understanding its complex mechanism of action and identifying patients at risk for non-response to CAR T-cell therapy. This first whole-body 89ZED88082A PET imaging study in the setting of CAR T-cell therapy demonstrated that the high 89ZED88082A uptake in spleen tissue decreased over time after lymphodepleting therapy and CAR T-cell infusion. A similar decreasing pattern was observed for bone marrow, while lymph nodes remained stable over time. Interestingly, brain 89ZED88082A uptake increased from pre-CART to post-CART day +5. We observed heterogeneity in tumor 89ZED88082A uptake between and within patients, both pre- and post-CART, and in the dynamics from pre-to post-CART. At a lesion level, higher 89ZED88082A uptake pre-CART was associated with higher uptake post-CART day +2. An overall 42% tumor volume reduction from pre-CART to post-CART at day +7 was noticed. Overall, patients with above median geometric mean pre-CART tumor 89ZED88082A uptake had a longer TTP and PFS.

This study demonstrated that an overall CD8+-involved tumor microenvironment prior to CAR T-cell therapy was associated with improved patient outcomes and showed an unexpectedly rapid clinical response post-CART, hampering the feasibility of performing biopsies in the first cohort. At the lesion level, the CD8+ T-cell infiltration varied per tumor lesion, and a CD8-permissive tumor microenvironment before CAR T-cell therapy resulted in a higher infiltration after CAR T-cell infusion and a lower hazard of disease progression at that site, emphasizing the added value of evaluating the CD8+ T-cell microenvironment more comprehensively. By enabling serial, systemic assessment of lymphoma lesions, 89ZED88082A-PET may serve to identify patients with specific lesions at risk of disease progression in the context of CAR T-cell therapy that would not be feasible with biopsy-based methods.

The first-in-human study using 89ZED88082A in patients with solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors showed high specificity and sensitivity of this Zirconium-labeled one-armed antibody tracer, including the ability to characterize the complex dynamics of CD8+ T-cells in the context of immunotherapy. These characteristics and the availability of a feasible, reproducible, and in-house acquired imaging protocol, including optimal “cold” dosage and imaging time point, supported the use of 89ZED88082A in our patient population9,16,17. In that study, high 89ZED88082A uptake at baseline was also associated with improved OS9. Additionally, 68Ga-grazytracer PET, targeting granzyme B secreted by activated CD8 T-cells, showed superior predictive value for PFS in patients with solid tumors and lymphoma compared to RECIST, PERCIST, or Lugano response criteria18. This approach may offer an opportunity to relate total T-cells versus active effector T-cells in patients and contribute to identifying patients or lesions at risk for CAR T-cell therapy failure at baseline18. In addition, strategies have emerged that aim to directly image the CAR T-cells. While these approaches remain largely investigational, they offer great potential for specific monitoring of CAR T-cell proliferation and persistence in vivo after CAR T-cell infusion, rather than predictive capacity prior to CAR T-cell infusion19,20,21,22.

Part of the improved response to CAR T-cell therapy in a high CD8-infiltrated tumor microenvironment might be explained by the role of bystander T-cells amplifying the response to CAR T-cell therapy8,23,24,25. Our data support this hypothesis, as do earlier but more limited studies based on single-lesion biopsies7. An immune-inflamed tumor microenvironment, consisting of a high T-cell infiltrate of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T-cells, may preserve essential chemokines and cytokines to support T-cell function7,25,26. Besides the reported improved T-cell function in such an immune-inflamed tumor, the influx and activation of CAR T-cells within the tumor microenvironment result in interleukin (IL)−2 and IL–15 secretion, which can serve as a spark that sets the fire for bystander T-cell activation8,23. In a nonhuman primate model, these activated bystander T-cells were capable of TCR-independent killing of tumor cells, potentially contributing to the overall cytotoxic effect of CAR T-cell therapy23.

Interestingly, following CAR T-cell infusion, a rapid change of immune tumor microenvironment features but a marked paucity of CAR T-cells compared to total intratumoral CD3+ T-cells was observed after day +5 or later in biopsies from DLBCL patients following axicabtagene ciloleucel infusion7,8. In addition, a low number of cells expressing the CAR transcript was noted, suggesting no decrease in the CAR surface protein due to receptor internalization upon recognition. In contrast, peak expansion of CAR T cells in peripheral blood is typically observed between days +7 and +14 with reduced detection of activation markers on peripheral CAR T-cell before day +58,11,27. This provides evidence for the rapid antitumor activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in a “hit-and-run” model, supported by the rapid tumor volume decrease from pre-CART to post-CART day +7 observed in this study. Definitive evaluation of this hypothesis requires future investigations, including biopsies obtained at earlier post-CART intervals or employing in vivo CAR T-cell imaging to delineate the CAR T-cell dynamics.

In this cohort, two patients with EBV+ DLBCL were included. EBV+ DLBCL is a very rare disease entity with a prevalence of only 4.1% of the subtype DLBCL not otherwise specified in Western countries28. It is characterized by a higher presence of CD8+ T-cells in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, resulting in a dysfunctional exhausted T-cell population12. Therefore, this disease entity presents as a distinct subtype of DLBCL with a mechanistically different disease biology, and therefore also impacts both CD8+ T-cell tumor presence and CAR T-cell outcomes (CR rates of 55% in EBV-related LBCL compared to 64% in EBV− LBCL)29,30. The higher CD8+ T-cell tumor infiltration in patients with EBV+ DLBCL was also observed within our study, as the pre-CART SUVpeak in these patients was significantly higher compared to the remainder of the cohort. Given the abbreviated increased CD8+ T-cell presence caused by a different disease biology and consequently higher tracer uptake, these patients (n = 2) were omitted in the primary tumor analyses in accordance with the predefined statistical analysis plan. As a result, the presented study findings are not fully generalizable to this specific population, and EBV-related LBCL should be studied separately.

This study has limitations. The used 89ZED88082A-tracer provided a comprehensive overview of the total CD8+ T-cell compartment and its application, both pre-and post-CART, enabled direct comparison between these settings. However, specific CAR T-cell behavior could not be extrapolated from these data, as CD8+CAR+ T-cells could not be distinguished from CD8+CAR- T-cells. After the study began, the protocol was amended to shorten the interval between CAR T-cell infusion and post-CART 89ZED88082A scans to better assess T-cell influx. As a result, each cohort consisted of a limited number of patients, consequently precluding bold conclusions based on the post-CART imaging results. However, linear mixed models were utilized to mitigate this limitation, which are designed to incorporate multiple observations at various time points for each patient. Also, multiple comparisons across tissues, time points, and outcomes were performed, which may increase the risk of false-positive findings. As initial response rates, but not the PFS and OS, were high in this cohort, the analysis between patients with a complete response compared to no complete response may have been influenced due to reduced statistical power. In addition, we observed a high prevalence of small lesions ( < 4.2 mL), which are prone to partial volume effects such as underestimation of the SUVpeak. To address this, we applied a previously established data-driven mathematical approach9, prioritizing the inclusion of small lesions, given lymphoma’s characteristic tendency to present in this way.

89ZED88082A imaging in the CAR T-cell therapy setting showed potential for identifying early lesions at risk for relapse while also being associated with longer TTP at the patient-level. This provides a window of opportunity to increase the CD8+ T-cell influx pre-CART and thereby improve CAR T-cell outcome. Interestingly, lower pre-CART MATV at the patient-level was associated with longer TTP as well. Pre-CART 89ZED88082A uptake and MATV were not correlated at the lesion level, suggesting that these measures represent distinct mechanisms influencing CAR T-cell outcomes and emphasizing the need to improve both to optimize CAR T-cell therapy outcomes.

Several methods have been described to potentially induce CD8+ (CAR) T-cell influx, including microenvironmental alkalization, armored CAR T-cells secreting cytokines, bispecific antibodies or enzymes, and low-dose radiation therapy31,32,33,34,35. Repurposing the use of radiotherapy is a compelling option. The addition of irradiation (4–8 Gy) prior to CAR T-cell infusion induced proliferation and infiltration of CAR T-cells and endogenous CD8+ T-cells in murine models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and lymphoma34,35. Moreover, in patients with ovarian cancer, low-dose irradiation (1 Gy) increased a Type 1 T-helper-, CD8+- and effector memory T-cell-signature and was essential in establishing a response to a combinatorial immunotherapy33. We observed, however, equal 89ZED88082A uptake in lesions receiving target dose irradiation and non-irradiated lesions. Notably, evaluating the impact of radiotherapy on CD8+ T-cell influx was challenging, given the study design. No additional 89ZED88082A infusion and PET scan was performed before radiotherapy, as the long washout period of 89Zr precluded such evaluations. Recently, preliminary results from a phase 1 dose-escalation study demonstrated the safety of an 18F-labeled CD8-targeted PET tracer, which allows for same-day imaging with rapid tracer clearance, enabling sequential scans within a short timeframe21. Overall, serial CD8 PET imaging holds the potential to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies aimed at increasing the permissiveness of the tumor microenvironment, which is especially essential in moving CAR T-cell therapy forward in solid malignancies. However, validation studies mapping CD8+-behavior in the context of CAR T-cell therapy and its relation to CAR T-cell outcomes are crucial in achieving this.

In conclusion, 89ZED88082A PET imaging enabled systemic evaluation of the CD8+ T-cell distribution before and during CAR T-cell therapy, revealing heterogeneity in CD8+ T-cell presence between and within patients, including low uptake before and after CAR T-cell therapy in lesions that subsequently relapsed. Early PET imaging demonstrated the association between pre-CART 89ZED88082A lesion uptake and post-CART uptake. In addition, major rapid tumor volume reduction was observed following CAR T-cell infusion, implicating a fast CAR T-cell therapy action mechanism. We demonstrated that higher tumor 89ZED88082A uptake in tumor lesions before CAR T-cell therapy is predictive for TTP and PFS, confirming the importance of an immune-permissive tumor microenvironment in CAR T-cell therapy.

Methods

Study design

The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients included provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen and the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects as competent authorities (METc 2020/559; International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) NL9034; EUCTR2020-004749-35-NL (accessible via the ICTRP search portal (https://www.who.int/tools/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal, first registration date 2020-11-04). First patient and the last patient were included on 2021-06-11 and 2023-09-28, respectively. The latest version of the study protocol is available as Supplementary Note 1 in Supplementary Information.

The primary objective was to study the distribution of CD8+ T-cells in normal tissues and tumor lesions before and after CAR T-cell therapy. Secondary objectives and endpoints included assessment of safety, tumor heterogeneity, and the influence of irradiation on 89ZED88082A uptake, the correlation of 89ZED88082A uptake with clinical outcomes, localized CD8 T-cell expression identified in a biopsy, and CAR T-cell expansion and associated cytokines.

This single-center, single-arm exploratory imaging trial comprised three cohorts. Eligible patients had histologically confirmed relapsed/refractory LBCL after at least two lines of therapy. They were accepted for CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy according to the criteria set by the Dutch CAR-T tumor board10. To limit heterogeneity in CAR T-cell dynamics caused by differences in the CAR T-cell product, only patients who were planned to receive axicabtagene ciloleucel were included. Eligible patients had measurable disease as defined by the Lugano criteria, from which a biopsy could safely be obtained. In cohorts 2 and 3, a biopsy was non-mandatory. Within this study, no discrepancies between sex and gender were noted. Sex was extracted from the electronic patient files and subsequently checked with the treating physician for patient-reported difference on gender.

After apheresis (day −28) and optional bridging therapy, patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) for three consecutive days (day −5 until day −3) before receiving a single infusion of CAR T-cells (day 0), according to standard practice. Baseline tumor burden before apheresis and before lymphodepleting chemotherapy was evaluated using [18F]FDG PET/CT scans assessed according to the Lugano criteria36.

Pre-CART 89ZED88082A-imaging was performed between optional bridging therapy and the start of lymphodepleting chemotherapy in all three cohorts. In the first cohort, post-CART 89ZED88082A-imaging was performed +7 days after CAR T-cell infusion. As ultrasound-guided biopsies revealed an unexpectedly rapid tumor response at day +7 post-CART after the start of the study, the protocol was amended to optimally study the (CAR) T-cell influx in the tumor lesions, and 89ZED88082A-PET was performed at day 5 in cohort 2, and subsequently in cohort 3 at days +2, +4, and +7 after CAR T-cell infusion (Supplementary Table 6).

89ZED88082A and [18F]FDG-tracer and PET procedures

Genentech Inc. supplied the DFO-conjugated one-armed antibody CED88004S, which was subsequently radiolabeled (89ZED88082A) in the UMCG, according to good manufacturing practice guidelines9,37. 89ZED88082A was stored until use at 2–8 °C for a max of 96 h. For all three cohorts, 89ZED88082A-tracer injections (37 MBq, 10 mg) were administered 2 days before a PET scan9. For [18F]FDG-PET imaging, patients were instructed to fast and avoid exercise at least 4–6 h before intravenous [18F]FDG injection (3 MBq/kg activity). Plasma glucose levels were <198 mg/dL before [18F]FDG administration, and imaging was performed 60 min ( ± 5 min) after [18F]FDG administration.

Both 89ZED88082A- and [18F]FDG-PET scans with low-dose CTs were performed on a Biograph Vision Quadra (128-slice)38, Biograph Vision 600 (128-slice)39, or Biograph mCT (40-slice)40; the scan procedure consisted of the skull to mid-thigh or whole-body (skull-feet) up to 15 bed positions. 89ZED88082A-PET and [18F]FDG-PET scans with low-dose CT were performed on a Biograph Vision Quadra (128-slice)38, Biograph Vision 600 (128-slice)39, or Biograph mCT (40-slice)40; the scan procedure consisted of the skull to mid-thigh or whole-body (skull-feet) up to 15 bed positions. PET images were reconstructed according to the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) Research Ltd. (EARL) standard 1 compliant reconstruction, as reported by the EANM41,42. One 89ZED88082A-PET scan was reconstructed according to the EARL standard 2 compliant protocol; therefore, a 7-mm Gaussian filter was applied to convert EARL2 to EARL1-compliant data43.

For the 89ZED88082A-PETs, normal tissues were delineated with TotalSegmentator44 (for 3D Slicer v5.4.045) to assess tracer biodistribution; in the case of apparent tumor infiltration, spherical volumes of interest (VOIs) were drawn in a non-pathogenic tissue region, where sphere size was dependent on the specific tissue. Tumor lesions were identified on diagnostic CT and [18F]FDG PET scans and then manually delineated on the 89ZED88082A-PET/CT, with the assistance of semi-automated algorithms using the MUST-segmenter if there was visible uptake13. In the case of no or limited 89ZED88082A-uptake, lesions were manually delineated in RayStation (v14.0.100.0; RaySearch Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden) using the corresponding low-dose CT. [18F]FDG PET tumor lesions were semi-automatically delineated with an SUV threshold of 2.5 using the MUST-segmenter, with manual adjustments for CNS localizations or overflowing into healthy tissue to ensure only tumor lesions were included13,15,46,47,48. For every patient, a maximum inclusion of 30 tumor lesions was applied. Afterwards, delineated tumor volumes and SUV metrics were extracted, where SUVs were calculated based on body weight, net injected radioactivity dose, and radioactivity within a tissue/lesion VOI.

Bridging therapy

For all eligible patients, the Dutch CAR-T tumor board considered bridging therapy comprising all therapies between apheresis and CAR T-cell infusion, including local radiotherapy, systemic therapy (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, corticosteroids), or a combination. Bridging therapy was administered to control and/or reduce tumor volume (debulking) and/or symptomatic relief, depending on individual patient and disease characteristics. Radiotherapy doses were delivered using intensity-modulated radiotherapy or volumetric-modulated arc therapy and planned using RayStation (v 11B), ranging from 8 to 20 Gy in 2 to 5 fractions. All patients underwent a planning CT, and the [18F]FDG PET/CT scan was matched, if applicable.

Tumor tissue analysis

For tumor tissue analysis, if considered feasible and safe, biopsies were performed before and/or after CAR T-cell infusion. Seven biopsies were obtained pre-CART (one before 89ZED88082A infusion, six after 89ZED88082A infusion) and four biopsies post-CART. Whenever possible, pre-treatment biopsies were performed, preferably two days after tracer infusion, following the 89ZED88082A PET/CT scan. For post-treatment biopsies, the procedure was conducted within five days after the second tracer infusion and within three days of the 89ZED88082A PET/CT scan. The tissue was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. If a pre-treatment biopsy was not feasible, archival tissue from the confirmed relapsed/refractory disease after progression on two earlier immunochemotherapy treatments was used for analysis. Before IHC staining for CD3-, CD8-, CAR T-, and CD19 expression, 4 µm tissue sections were analyzed using autoradiography. When applicable, consecutively cut slides were used for autoradiography and IHC to enhance results comparability.

Slides were exposed to a multipurpose phosphor storage plate (PerkinElmer) for two to five days, and exposures were captured using a Typhoon phosphor imager. Autoradiography images were scaled and visibly matched to IHC staining results based on slide position. CD3- and CD8-expression was determined with an automated stainer (Ventana Benchmark Ultra, Ventana Medical Systems) using anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody 2GV6 (Ventana; ready-to-use) and anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody C4/144B (DAKO/Agilent; dilution 1:20), respectively. CD8 T-cell density, expressed as an estimated percentage of the total cell population based on a hematoxylin and eosin staining, was scored by L.V., who was blinded for tracer uptake on the 89ZED88082A PET/CT-scan and the outcome of CAR T-cell therapy. CD8 T-cell density in the biopsy was correlated with the SUVpeak of the corresponding lesion.

To detect infiltrating CAR T-cells in post-treatment biopsies, slides were stained with an anti-Whitlow KIP1 antibody, kindly provided by Kite Pharma (dilution 1:400). To detect tumor presence, automated CD19 IHC staining (LE-CD19 antibody, Thermo Fisher; dilution 1:1600) was performed.

Measurement of circulating T-cells and cytokines

Plasma and serum were collected at days 0, +7, and +28. Plasma samples were collected in EDTA tubes (BD Biosciences), and serum samples were processed using standard serum separator tubes (BD Biosciences). Samples were harvested after centrifugation for 10 min at 1500 g and stored at −80 °C. Before processing, serum or plasma samples were thawed and analyzed using the following Simple Plex cartridges (Bio-Techne): Cytokine panel 1 human (IL–1β/IL–1F2, IL–12 p70, IL–10, IL–2, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a, IL–4, IL–6) and a custom-built cytokine panel human (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL–17A, IL–5, C-X-C motif ligand 8/IL–8). Both panels were carried out according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The cartridges were analyzed using the Ella system (Bio-Techne), and data processing was performed using the Simple Plex Runner software (Bio-Techne). Analyte values were reported as pg/mL.

To determine circulating CD8+- and CAR T-cells, gDNA was extracted using a QIAmp DNA Blood Mini kit (#51104, Qiagen GmbH) from the same time points. The manufacturer’s instructions were followed. The concentration of extracted gDNA was measured using Multiskan Sky (Thermo Fisher). The PCR mixture of 25 µL, containing 0.75 µL mix of primers (80 µM) and probes (80 µM) targeting FMC63 (FWD: TGAAACTGCAGGAGTCAGGA, REV: CTGAGACAGTGCATGTGACG, Probe: FAM-CTGGCCTGGTGGCGCCCTCA-MGB/NFQ; generated based on Schubert et al.49) or CD8 (FWD: GGGCCCTCTCCTAAATGTCG, REV: TCGGGACTTACTGTGGTTGC, Probe: /56-FAM/CTACATCTG/ZEN/GGCGCCCTTGGC/3IABkFQ/; generated with benchling.com and ordered via Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT)) and GATA2 (FWD: TGGCGCACAACTACATGGAA, REV: CGAGTCGAGGTGATTGAAGAAGA, Probe: /5SUN/TGCTGCCTC/ZEN/CAGACGAGGTG/3IABkFQ/; generated with benchling.com and ordered via Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT)), 11.75 µL TaqMan fast advanced master mix (#4444557, Thermo Fisher) and 100 ng gDNA. A standard curve (101 to 106 copies/ng gDNA) and a non-target control were included in all experiments. All reactions were performed in triplicate.

The amplification conditions used were: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 min, 58 °C for 5 s, and 65 °C for 20 s. qPCR was performed using a QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher).

The copy numbers were calculated using the formula: copy number per cell = qPCR copy#/µL of FMC63 or CD8 / qPCR copy#/µL of GATA2 x 2. Values were reported as copies/µL gDNA.

Clinical outcomes and toxicities

Tumor response evaluations were performed on day +28, months +3, +6, and +12 after CAR T-cell infusion using [18F]FDG-PET/CT scans assessed according to the Lugano criteria36. For the time-to-event analysis, follow-up time started at CAR T-cell infusion. TTP was determined from the time of CAR T-cell infusion to disease progression or death due to lymphoma as the definition of an event. Censoring was performed for the death of any other cause than PD or, in case of no death, the last known follow-up date. OS and PFS were defined as the time from CAR T-cell infusion until death from any cause, as well as PFS, PD, or death from any cause. Censoring was performed in patients still alive at the last known follow-up date50. Safety was assessed according to common terminology criteria for adverse events v5.0 of the National Cancer Institute and followed until abated or a stable situation. Monitoring of tracer-related adverse events will be executed from the day of infusion until 30 days after tracer infusion. The CAR T-cell-related toxicities, CRS and ICANS, were graded according to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria51.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses followed a pre-defined statistical analysis plan (SAP). Standard descriptive statistics summarized key patient, tissue, and tumor characteristics. No sex- or gender-based analyses were performed, as this was not considered a confounding factor in the normal organ and tumor tissue CD8+ T-cell distribution. Primary results and conclusions were based on excluding EBV-positive lymphomas, according to the SAP. The relationship between 89ZED88082A uptake in normal tissues and tumor lesions and various study factors (e.g., imaging time points post-CAR T-cell infusion, adverse events, prior irradiation, and treatment response) was assessed using linear mixed-effect models. As input, we used the values measured at pre-CART (full cohort) and post-CART days +2 (cohort 3), +5 (cohort 2) and +7 (cohort 1), which all were collected 2 days after 89ZED88082A tracer injection. These models included random intercepts to account for repeated measurements within individual patients. Random slopes were evaluated to determine whether their inclusion would improve model fit. Additionally, Pearson correlation coefficients were applied to clustered data52.

For normal tissue analyses, the SUVmean (average SUV value across the delineated volume) was used as the 89ZED88082A uptake measure; for tumor tissue analyses, the SUVpeak (average SUV value within a 1 mL region of highest uptake across the delineated volume) was preferred over the SUVmax (maximum single-voxel SUV value within the delineated volume), as the SUVpeak is reported to be (slightly) more robust53,54. Next, SUVpeak was naturally log-transformed to account for the skewness of the distribution. Results were back-transformed to retrieve estimated geometric means. Normal tissue SUVmean was analyzed without transformation. 89ZED88082A uptake model estimates were obtained under restricted maximum likelihood, with 95% CIs based on Satterthwaite denominator degrees of freedom and Wald-based P-values (under restricted maximum likelihood) for factor-level comparisons ( > 2-factor levels) and likelihood ratio test (under maximum likelihood) P-values for variable-level comparisons.

For normal tissue visualizations over time from pre- to post-CART, temporal uptake curves were fitted using imaging time points as a continuous variable, where the best fit (linear, log-linear, or quadratic) was selected using Akaike’s Information Criterion under maximum likelihood55. To compare 89ZED88082A uptake between the different time points, the linear mixed model approach was applied as described earlier, in addition to a likelihood ratio test under maximum likelihood to obtain a variable-level P-value, also using Wald statistics under restricted maximum likelihood.

For the analysis of 89ZED88082A tumor uptake, a mathematical correction was applied to address measurement errors caused by partial volume effects, aiming to mitigate potential underestimations of SUVpeak in smaller lesions. This was performed under the assumption that, on average, low-volume lesions and high-volume lesions have equal CD8 cell numbers, resulting in, on average, identical true (geometric) mean SUVpeak values and that any differences in (geometric) mean SUVpeak are due to partial volume effects. For this, the volume-SUVpeak relation using pre-CART data only from lesions without radiotherapy bridging was assessed (170 lesions in 17 patients) by using a 4-knot restricted cubic spline. This revealed that lesions ≥5 mL showed no relation between SUVpeak and volume, while lesions <5 mL showed a decrease in measured geometric mean SUVpeak with decreasing volume. To determine the expected SUVpeak of each lesion relative to the average lesion of 5 mL, the SUVpeak of each lesion was first expressed as the difference from the estimated geometric mean SUVpeak for lesions of the same volume. This difference was adjusted by adding the geometric mean SUVpeak of 5 mL lesions. Pseudocode for partial volume correction calculation is provided in Supplementary Note 2.

This volume-adjusted SUVpeak was analyzed for all primary and secondary endpoints, assuming the relation between volume and 89ZED88082A uptake in the pre-CART data covers the partial volume effect complications. The described approach for linear mixed models was applied to investigate the dose-response relation for individual tumor lesions in patients who received bridging radiotherapy. Still, a non-linear relation using a restricted cubic spline was also assessed.

To assess the relation between patient-level 89ZED88082A SUVpeak and TTP, PFS, and OS, tumor SUVpeak was summarized per patient by calculating the geometric mean SUVpeak of all lesions within each patient. Geometric mean SUVpeak was analyzed both categorically based on a median-split and continuously (assuming linearity). More optimal cut-offs were not investigated due to the small sample size. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were employed, while Firth-penalized Cox models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and C-indexes, assessing the ability of pre-CART SUVpeak to differentiate between patients with a short versus long event-free duration. Standard univariable analysis was used to correlate 89ZED88082A tumor/tissue uptake with adverse events, ICANS and CRS. Because of the small sample size and, therefore, limited statistical power, no multivariable analysis was conducted.

Statistical analysis was performed using R v4.3.3. All P-values were retrieved without correcting for multiple testing, and P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

De-identified data not subject to privacy concerns, including (unadjusted) SUV metrics extracted from the 89ZED88082A PET-scan, are provided in the Source Data File. Due to the sensitive nature of the data and the potential risk of participant re-identification inherent in this small cohort, the clinical data and detailed lesion characteristics cannot be made publicly available. This restriction is in accordance with the informed consent provided by study participants, UMCG guidelines, and relevant Dutch legislation (GDPR/AVG, WMO). Data may be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to completion of a data sharing agreement. All requests will be reviewed within four weeks. Data will become available upon publication of this manuscript and will remain available for ten years. Data will likely be shared electronically. The study protocol is available as Supplementary Note 1 in Supplementary Information. The remaining data are available within the Article, Supplementary Information or Source Data file. Genentech developed CED88004s and is the owner of its intellectual property. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Pseudocode to calculate the partial volume correction is provided as Supplementary Note 2 in Supplementary Information.

References

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Comparison of 2-year outcomes with CAR T cells (ZUMA-1) vs salvage chemotherapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 5, 4149–4155 (2021).

Albelda, S. M. CAR T cell therapy for patients with solid tumours: key lessons to learn and unlearn. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 47–66 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med 382, 1331–1342 (2020).

Shah, B. D. et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet 398, 491–502 (2021).

Berdeja, J. G. et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 398, 314–324 (2021).

Ruella, M., Korell, F., Porazzi, P. & Maus, M. V. Mechanisms of resistance to chimeric antigen receptor-T cells in haematological malignancies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 976–995 (2023).

Scholler, N. et al. Tumor immune contexture is a determinant of anti-CD19 CAR T-cell efficacy in large B-cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 28, 1872–1882 (2022).

Chen, P. H. et al. Activation of CAR and non-CAR T cells within the tumor microenvironment following CAR T cell therapy. JCI Insight 5, e134612 (2020).

Kist de Ruijter, L. et al. Whole-body CD8+ T cell visualization before and during cancer immunotherapy: a phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 2601–2610 (2022).

Spanjaart, A. M. et al. The Dutch CAR-T tumorboard experience: population-based real-world data on patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma referred for CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy in the Netherlands. Cancers 15, 4334 (2023).

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2531–2544 (2017).

Cohen, M. et al. Cytotoxic response against Epstein-Barr virus coexists with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma tolerogenic microenvironment: clinical features and survival impact. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Keijzer, K. et al. Semi-automated 18F-FDG PET segmentation methods for tumor volume determination in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients: a literature review, implementation and multi-threshold evaluation. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 1102–1114 (2023).

Hubbeling, H. et al. Metabolic tumor volume response after bridging therapy determines chimeric antigen receptor T-cell outcomes in large B-cell lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res 30, 5083–5093 (2024).

Keijzer, K. et al. Reducing and controlling metabolic active tumor volume prior to CAR T-cell infusion can improve survival outcomes in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 14, 41 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. The role of CD8 PET imaging in guiding cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 15, 1428541 (2024).

Wei, W. et al. ImmunoPET: concept, design, and applications. Chem. Rev. 120, 3787–3851 (2020).

Shen, X. et al. 68Ga-grazytracer PET for noninvasive assessment of response to immunotherapy in solid tumors and lymphomas: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Nat. Commun. 15, 8791 (2024).

Kurtz, K. et al. Engineering CAR-T cells for radiohapten capture in imaging and radioimmunotherapy applications. Theranostics 13, 5469–5482 (2023).

Keu, K. V. et al. Reporter gene imaging of targeted T cell immunotherapy in recurrent glioma. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaag2196 (2017).

Minn, I. et al. Imaging CAR T cell therapy with PSMA-targeted positron emission tomography. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw5096 (2019).

Sakemura, R. et al. Development of a clinically relevant reporter for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell expansion, trafficking, and toxicity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 9, 1035–1046 (2021).

Kaminski, J. et al. B-cell-directed CAR T-cell therapy activates CD8+ cytotoxic CARneg bystander T cells in patients and nonhuman primates. Blood 144, 46–60 (2024).

Meier, S. L., Satpathy, A. T. & Wells, D. K. Bystander T cells in cancer immunology and therapy. Nat. Cancer 3, 143–155 (2022).

Ortiz-Muñoz, G. et al. In situ tumour arrays reveal early environmental control of cancer immunity. Nat. Med 618, 827–833 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Large B-cell lymphoma microenvironment archetype profiles. Cancer Cell 43, 1347–1364.e13 (2025).

Hamilton, M. P. et al. CAR19 monitoring by peripheral blood immunophenotyping reveals histology-specific expansion and toxicity. Blood Adv. 8, 3314–3326 (2024).

Bourbon, E. et al. Clinicopathological features and survival in EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified. Blood Adv. 5, 3227–3239 (2021).

Nair, R. et al. CD19 CAR-T Outcomes in Patients with EBV-Positive DLBCL. Blood 140, 3800–3802 (2022).

Nastoupil, L. J. et al. Standard-of-care axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: results from the US lymphoma CAR T consortium. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3119–3128 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Microenvironmental alkalization promotes the therapeutic effects of MSLN-CAR-T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, e009510 (2024).

Carcopino, C., Erdogan, E., Henrich, M. & Kobold, S. Armoring chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells as micropharmacies for cancer therapy. Immunooncol. Technol. 24, 100739 (2024).

Herrera, F. G. et al. Low-dose radiotherapy reverses tumor immune desertification and resistance to immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 12, 108–133 (2022).

Kostopoulos, N. et al. Local radiation enhances systemic CAR T cell efficacy by augmenting antigen cross-presentation and T-cell infiltration. Blood Adv. 8, 6308–6320 (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Systemic tumor regression with synergy therapy: radiotherapy and CAR-T. Cell Death Discov. 10, 479 (2024).

Cheson, B. D. et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 3059–3067 (2014).

Gill, H. et al. The production, quality control, and characterization of ZED8, a CD8-specific 89Zr-labeled immuno-PET clinical imaging agent. AAPS J. 22, 22 (2020).

Prenosil, G. A. et al. Performance characteristics of the Biograph Vision Quadra PET/CT system with a long axial field of view using the NEMA NU 2-2018 standard. J. Nucl. Med 63, 476–484 (2022).

van Sluis, J. et al. Performance characteristics of the digital biograph vision PET/CT system. J. Nucl. Med. 60, 1031–1036 (2019).

Rausch, I. et al. Performance evaluation of the Biograph mCT Flow PET/CT system according to the NEMA NU2-2012 standard. EJNMMI Phys. 2, 26 (2015).

Boellaard, R. et al. The Netherlands protocol for standardisation and quantification of FDG whole body PET studies in multi-centre trials. Eur. J. Nucl. Med Mol. Imaging 35, 2320–2333 (2008).

Boellaard, R. et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 42, 328–354 (2015).

Kaalep, A. et al. Quantitative implications of the updated EARL 2019 PET–CT performance standards. EJNMMI Phys. 6, 28 (2019).

Wasserthal, J. et al. TotalSegmentator: robust segmentation of 104 anatomic structures in CT images. Radio. Artif. Intell. 5, 5 (2023).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson Imaging 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

Breen, W. G. et al. Metabolic PET/CT analysis of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma prior to axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR-T infusion: predictors of progressive disease, survival, and toxicity. Blood Cancer J. 13, 1–5 (2023).

Eude, F. et al. Reproducibility of baseline tumour metabolic volume measurements in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: is there a superior method?. Metabolites 11, 1–16 (2021).

Barrington, S. F. & Meignan, M. Time to prepare for risk adaptation in lymphoma by standardizing measurement of metabolic tumor burden. J. Nucl. Med 60, 1096–1102 (2019).

Schubert, M. L. et al. Assessment of CAR T cell frequencies in axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel patients using duplex quantitative PCR. Cancers 12, 2820 (2020).

Cheson, B. D. et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 579–586 (2007).

Lee, D. W. et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 25, 625–638 (2019).

Lorenz, D. J., Datta, S. & Harkema, S. J. Marginal association measures for clustered data. Stat. Med 30, 3181–3191 (2011).

Jauw, Y. W. S. et al. Noise-induced variability of immuno-PET with zirconium-89-labeled antibodies: an analysis based on count-reduced clinical images. Mol. Imaging Biol. 20, 1025–1034 (2018).

Lodge, M. A., Chaudhry, M. A. & Wahl, R. L. Noise considerations for PET quantification using maximum and peak standardized uptake value. J. Nucl. Med 53, 1041–1047 (2012).

Säfken, B., Rügamer, D., Kneib, T. & Greven, S. Conditional model selection in mixed-effects models with caic4. J. Stat. Softw. 99, 1–30 (2021).

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and their informal caregivers, the CAR T-cell clinical trial office, and L. Pot, affiliated with the Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands, for clinical tracer production coordination. This study was funded by a research grant from Genentech, made available to the University Medical Center Groningen, and a PPP-allowance of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (PPP 2023-018). This is an investigator-initiated trial with the University Medical Center Groningen as sponsor. Therefore, the sponsor, represented by the principal investigator, was involved in the study design, data collection and analysis and manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.v.M. A.G.H.N., J.A.v.D., G.A.H., S.P.W., A.U., and E.G.E.d.V. designed the study. T.v.M., J.A.v.D., J.W.d.B., and A.G.H.N. were responsible for clinical patient coordination. Data acquisition was carried out by J.A.v.D, J.W.d.B., T.v.M., K.K., A.G.H.N., L.V.v.D., S.P.W., A.U., and M.N.L.H., and K.K., A.G.H.N., A.H.B., J.v.S., and W.N. were responsible for image acquisition. J.W.d.B., N.A.M.S., F.R.P., L.V., and A.D. conducted translational research. S.G.E., K.K., J.W.d.B., and L.V.v.D. carried out the statistical analysis. T.v.M., E.G.E.d.V., and A.G.H.N. provided supervision. J.W.d.B., K.K., J.A.v.D., T.v.M., A.G.H.N., and E.G.E.d.V. wrote the manuscript with input, edits, and approval from G.A.H., A.D., A.H.B., J.v.S., M.N.L.H., L.V., W.N., S.P.W., A.U., and S.G.E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.N.L.H. reports institutional financial support for advisory boards/consultancy from Merck and institutional financial support for clinical and preclinical studies from Amgen, Bayer, and Servier. L.V.v.D received funding unrelated to this project from NWO ZonMw via the VENI (NWO-09150162010173), individual career development grant, and Dutch Cancer Society Young Investigator Grant (KWF-13529). A.D. received research funding from Takeda. A.U. and S.P.W. are employees and stockholders of Genentech Inc., a member of the Roche group. S.G.E. received teaching fees from MSD. E.G.E.d.V. reports institutional financial support for advisory boards/consultancy from NSABP, Daiichi Sankyo, and Crescendo Biologics and institutional financial support for clinical trials or contracted research grants from Amgen, Genentech, Roche, Bayer, Servier, Regeneron, and Crescendo Biologics. A.G.H.N. received research funding from Siemens and Genentech. T.v.M. received research grants from Genentech, Celgene/BMS, and Siemens made available to the institution; personal fees from Kite/Gilead, Janssen, and Eli Lilly (advisory boards or consultancy); and honoraria from Kite/Gilead and Celgene/BMS (speaker fees). A.H.B. reports research grants from Siemens, paid to the institution, outside submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chongyang Duan, Roni Shouval and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Boer, J.W., Keijzer, K., van Doesum, J.A. et al. Whole-body CD8+ T-cell PET imaging in patients with large B-cell lymphoma before and during CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy: a phase 2 study. Nat Commun 16, 11629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66767-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66767-9