Abstract

Sound holography has shown great capability in reconstructing the arbitrary complex sound fields, with potential applications in various scenarios. To overcome the limitations of existing technologies in terms of capacity and security, here we propose and experimentally demonstrate a mechanism of orbital angular momentum- (OAM-) and frequency-dependent high-capacity encrypted hologram through multi-dimensional multiplexing acoustic metasurface. By customizing the acoustic response of the metasurface based on a theoretically-derived transfer function, we bestow the metasurface with mode and spectrum selectivity simultaneously such that multiple predesigned images can be stored in parallel and restored with specific combinations of vortex mode and wavelength, thereby realizing the double-key-secured high-capacity holography. A distinct example of image reconstruction of multiple patterns is experimentally demonstrated, achieving as many independent hologram channels as the working frequency number multiplied by the OAM mode number and high-quality reconstruction of sound field information with strong confidentiality. Our methodology offers an avenue for building ultrahigh-capacity holographic information systems in acoustics, with far-reaching impact on encrypted sound communication and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acoustic holography, a disruptive technique to record and reconstruct the full-wave information of arbitrary targets precisely, has sparked tremendous interest among scientists and engineers of many disciplines, with great potential in diverse applications spanning from ultrasonic transcranial imaging to particle manipulations1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Conventional acoustic hologram techniques usually capitalize on sophisticated phased arrays composed of numerous individually addressed transducers to reshape the spatial sound field as required8,9. In addition to the high cost and complexity of fabrication, the bulky size of transducer units, which is usually as large as the wavelength scale, especially in the ultrasonic range, will unavoidably restrict the space-bandwidth product as well as the hologram resolution. In stark contrast, the recently emerging acoustic metamaterials and metasurfaces with exceptional properties unattainable in nature offer a solution to mold the wavefront into almost arbitrary profile with significantly higher degrees of freedom (DoF) than conventional phased arrays at a fraction of the cost and complexity10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. As a result, the cutting-edge developments combining acoustic holography with metamaterials/metasurfaces revolutionize the technique of achieving high-quality acoustic holograms and demonstrate various fascinating progress, including the creation of complicated patterns of acoustic vortex knots18 and arbitrarily shaped microbubble cavitation fields19, among others20,21,22,23.

Nevertheless, most of the existing acoustic metasurfaces can only produce one fixed holographic pattern at a particular imaging plane, leading to limitations in terms of information capability and flexibility24,25,26,27. Along with this, the holographic information is also easy to be reproduced or intercepted just by illuminating the metasurface with simple waves. To improve the sound information capacity, recent efforts have focused on frequency-multiplexing sound holography, for which distinct patterns are encoded onto different driving frequencies28,29,30,31. However, information capacity in these approaches is still severely limited by spectrum crosstalk and operation bandwidth. Despite spin and polarization multiplexing mechanisms having been proven to be effective in optical holography32,33,34,35,36, their realization in acoustic systems is impossible due to the lack of physical dimensions of acoustic spin and polarization, resulting in the few channels available for storing acoustic hologram information. On the other hand, orbital angular momentum (OAM) provides a new DoF independent of polarization or spin for multiplexing a set of orthogonal modes on the same frequency channel to achieve high spectrum efficiency, which also plays important roles in rotational Doppler shift, edge image processing, and high-speed optical/acoustic communications37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. In recent investigations within the realms of optics and microwaves, increasing attention has been directed towards OAM-multiplexing holography that superposes OAM of light/microwave into metasurfaces45,46,47,48, yet whose direct translation into acoustics will result in unpractical size due to the long wavelength of sound waves. To date, OAM manipulation has still been a missing piece of the puzzle in multi-dimensional multiplexing sound holography. This challenge may be attributed to the lack of an effective mechanism for simultaneously modulating the multiple dimensions of sound, including both OAM and frequency. As a consequence, realizing high-capacity and high-security sound holograms still remains an elusive and unresolved challenge.

In this article, we propose a multi-dimensional multiplexing acoustic hologram mechanism by exploiting OAM as a new manipulation dimension and marrying it with frequency multiplexing to superpose separate patterns into different OAM/frequency modes, which significantly enlarges the information capacity of the holographic sound field. To this end, we develop a novel dual-multiplexing acoustic metasurface with OAM and frequency selectivity and realize, for the first time, the high-capacity high-security acoustic OAM hologram. The orthogonality of OAM modes and frequencies guarantees the double-key confidentiality of image information because each holographic pattern can only be effectively reconstructed by the corresponding combination of specific OAM and frequency. To practically implement this scheme, a unit cell of meta-pixels with amplitude-phase decoupled modulation function at arbitrary frequency components is systematically designed, which is capable of restoring the high-capacity multiplexed information of holographic sound fields in subwavelength spatial resolution. Two proof-of-concept examples of reconstructing four Arabic numerals and four alphabet letters are demonstrated both numerically and experimentally, which show good agreement with the design and verify the advantage of our proposed mechanism in terms of high-quality, large capacity, and enhanced security.

Results

The theory of multi-dimensional multiplexing sound holography

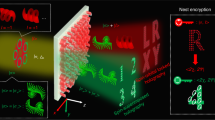

Figure 1 schematically illustrates our proposed multi-dimensional multiplexing acoustic hologram mechanism, in which acoustic holography information is stored in a monolayered metasurface and can be reconstructed by illuminating the metasurface with incident waves carrying specific keys. In our mechanism, two multiplexing DoFs, OAM and frequency, are simultaneously introduced to increase the information capacity of holographic patterns. To be specific, on the one hand, coexisting orthogonal OAM modes at the same frequency help improve spectral efficiency and relax the requirement for spectrum width. On the other hand, each OAM mode can be broadened to several parallel ones with separate wavelengths, which eliminates the dependence on high-order OAM modes with strong divergence effects and thereby improves the imaging quality of reconstructed patterns. In addition, these two manipulation DoFs also serve as two physical keys, which means that the information hidden in the hologram metasurface can be unveiled solely by OAM beams with specific topological charges and frequencies, as will be theoretically elucidated later. As a result, our proposed OAM- and frequency-dependent mechanism can effectively extend the multiplexing dimension of acoustic holography, making the high-capacity information effectively stored in the double-encrypted holograms and rendering the information exceedingly difficult to decipher, which is beyond the capabilities of existing methods.

The multiple holographic images are stored in different OAM and frequency channels and can be reconstructed by illuminating the holography metasurface with incident beams with the corresponding combination of specific OAM and frequency. The diagram illustrates a specific multiplexing example involving two OAM modes (±1) and two frequency channels.

To implement our mechanism, we begin by analyzing how customizing the acoustic response of the metasurface (i.e., amplitude, phase, frequency, and OAM) enables the introduction of OAM and frequency multiplexing dimensions, which will be theoretically derived in what follows. For a specific targeted holographic image, a pre-processing of spatial sampling is performed to ensure the OAM selectivity of our mechanism (Fig. 2a), which is commonly used in the holography technique48,49. If spatial sampling is omitted or the sampling interval is too small, donut-shaped artifacts may overlap and cause constructive interference, which in turn degrades OAM selectivity (see Supplementary Note 1 for more details). Here, we discretize the holographic image into N pixels with a sampling interval of 2λ, which can effectively prevent spatial overlap of the output while preserving high information density. \({A}_{n}^{l}\) and \({\varPhi }_{n}^{l}\) are the amplitude and phase of the n-th pixel (\(n=1,2,3,{{\mathrm{..}}}.,N\)) of the holographic image to be encoded in the l-th OAM channel at frequency \(f\). The metasurface is composed of M units. Then, the relationship between the acoustic response of the metasurface and the targeted holographic image can be established by the following matrix equation:

where \({G}_{nm}=\frac{\exp [{{\rm{j}}}(-2\pi f{r}_{nm}/{c}_{0})]}{4\pi {r}_{nm}}\) is the Green’s function of a point source in free space, rnm is the distance between the n-th image pixel and the m-th unit of the metasurface, and c0 is the sound speed in air. Through matrix inversion of Eq. (1), we can obtain the complex amplitude profile \({p}^{f,l}\) required for generating the corresponding holographic image (Step 1 in Fig. 2b). By encoding \({p}^{f,l}\) with an additional helical phase distribution of -lθ (θ is the azimuth angle and l is the topological charge of the OAM mode), the hologram metasurface is imprinted with OAM and frequency selectivity (Step 2 in Fig. 2b), which means that only emitting an OAM mode with inverse topological charge (l) and corresponding frequency (f) can decode and restore the information hidden in the hologram and consequently recover the fundamental spatial mode with a relatively stronger intensity distribution in each pixel of the holographic image. Then, the OAM- and frequency-multiplexing acoustic hologram can be realized by superposing multiple OAM- and frequency-selective responses on the metasurface (Step 3 in Fig. 2b). Based on this, the general transfer function of the metasurface can be written as follows

where f0 is the frequency of the incident wave, and \(\delta\) is the Kronecker delta function. In the above, by utilizing the Green’s function of a point source in free space and the matrix inversion method, we directly calculate the phase and amplitude mask of the metasurface, without satisfying the paraxial approximation condition. Therefore, the transfer function between the image and hologram metasurface established in our mechanism remains effective even when the metasurface’s size and imaging distance are relatively small. Thanks to this, our mechanism can operate within a compact physical size and demonstrates a remarkable advantage in terms of improved information density. To verify the above theoretical derivations, here we first showcase a simple example of reconstructing four distinct holographic images (alphabet letters A, B, C, and D) stored in two OAM channels and two frequency channels through numerical calculations. In such a case, the detailed process of deriving the phase and amplitude profile on the multiplexing metasurface is illustrated in Fig. 2a, b. The results in Fig. 2c reveal that the multi-dimensional multiplexing holograms accordingly respond to incident OAM beams with different topological charges and working frequencies, which shows the successful reconstruction of the designated holographic patterns in the image plane in a high-quality and low-crosstalk way. The above results verify the effectiveness of our mechanism in extending the hologram multiplexing dimension and boosting information capacity. Besides, our mechanism offers an advantage over traditional phase-only devices in achieving high-quality hologram reconstruction, as demonstrated by a representative example in Supplementary Note 2. In our theoretical design, OAM selectivity and imaging encoding are accomplished through multiplying the hologram by an ideal helical phase. This means that retrieving the image’s information requires illuminating the metasurface with a perfect vortex beam. However, the vortex beam experiencing propagation in the real-world system cannot hold a perfect pattern. To inspect its influence, we further analyze the tolerance of our mechanism to phase disturbance typically induced by diffraction, medium inhomogeneities, volume scattering, and beyond, and the results in Supplementary Note 3 demonstrate the high robustness of our mechanism against these factors.

a Pre-processing of spatial sampling on the target images. b The schematic diagram of the derivation of phase and amplitude profiles of the metasurface for realizing the OAM- and frequency-multiplexed acoustic hologram. The formula \({{\bf{x}}}={G}^{-1}{{\bf{y}}}\) indicates matrix inversion to obtain the amplitude-phase profile of the metasurface, where x and y are the complex amplitude profiles of the metasurface’s acoustic response and target image, and G is Green’s function. c Target images (upper) and numerically calculated OAM- and frequency-dependent holographic images (lower) for four cases of different beam incidence with topological orders l = ±1 and frequencies f1 = 13720 Hz and f2 = 17150 Hz.

Design of meta-pixels

For the purpose of realizing the OAM- and frequency-dependent hologram, the acoustic response of the metasurface needs to be customized according to Eq. (2), which calls for the simultaneous modulation of the phase, amplitude, frequency, and OAM characteristics of sound. This is challenging for the existing metamaterial/metasurface unit cells with few controllable DoFs. Here, we propose the design of an acoustical meta-pixel structure capable of all-dimensional sound wave modulation in air, which serves as the basic building block of our multi-dimensional hologram metasurface. The proposed meta-pixel, whose geometry is shown in Fig. 3a, is judiciously designed to contain multiple subunits and each subunit consists of three functional parts, namely, an amplitude modulator, a phase modulator and two spectral filters, whose cross-sections are marked by red, blue, and black outlines, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3b. The length, width, and height of the i-th layer of subunit 1 and subunit 2 are \({W}_{i}^{1,\,2}\), \({D}_{i}^{1,\,2}\), and \({H}_{i}^{1,\,2}\), respectively. Here we showcase a structural design with two subunits that work at dual frequencies of f1 = 13720 Hz and f2 = 17150 Hz. In such a design, we introduce controllable impedance mismatch to realize full-range amplitude modulation, which is implemented by adjusting the width \({D}_{i}^{1,\,2}\) of the impedance modulation layer. Furthermore, to simultaneously control the transmitted phase within the same spatial dimension, the effective refractive index of the units is precisely tailored by lengthening or shortening the equivalent propagation distance of the zig-zag pipe of the phase modulator (i.e., varying \({H}_{6}^{1,\,2}\)). In addition, the spectral filters on two sides ensure that acoustic waves at the specific frequency interact exclusively with their corresponding subunit, without penetrating into the other, thereby providing strong frequency selectivity. However, the sound waves propagating within these three parts are mutually coupled, resulting in difficulties in traversing the full parameter space of amplitude-phase at different frequencies in a decoupled way. To address this, we theoretically derive the transfer function of the meta-pixel and, based on it, determine the decoupled points within two-dimensional parameter spaces defined by \({H}_{4}^{1,\,2}\) and \({H}_{5}^{1,\,2}\), at which the meta-pixel enables decoupled amplitude-phase modulation at each frequency component (see Supplementary Note 4 for detailed theoretical derivations and the procedure for determining the decoupling points). The specific geometrical parameters of the meta-pixel are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

a Schematic diagram of a meta-pixel consisting of two amplitude-phase modulation subunits with high frequency selectivity. Subunits 1 and 2 are marked as S1 and S2, respectively. b Cross-sectional view of S1 and S2. \({W}_{i}^{1,\,2}\), \({D}_{i}^{1,\,2}\), and \({H}_{i}^{1,\,2}\) are the length, width, and height of the i-th layer of S1 and S2, respectively. Specifically, \({H}_{6}^{1,\,2}\) is the total length of the zig-zag pipe in Layer 6. c Transmission curves of subunit 1 and subunit 2 from 12 kHz to 20 kHz. d The amplitude distribution of the internal sound field through the unit cell at 13720 Hz (left) and 17150 Hz (right).

Next, we use numerical simulation to demonstrate the amplitude-phase decoupled modulation functionality as well as the frequency multiplexing performance of our designed meta-pixel. Throughout the paper, the simulations are conducted with a finite element method based on COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS 6.1 software. Figure 3c shows the transmission spectra of subunit 1 and subunit 2 within a frequency range of 12 kHz to 20 kHz. It can be seen that at 13720 Hz, the transmission coefficient of subunit 1 (0.99) is much higher than that of subunit 2 (0.18), and the situation is opposite at 17150 Hz (the transmission coefficient is 0.17 for subunit 1 and 0.99 for subunit 2). For a clearer illustration, we also simulate in Fig. 3d the acoustic pressure distribution through the whole meta-pixel at two operation frequencies f1 and f2, respectively. These results suggest that the response of subunit 1 (2) is dominant when the driving frequency is f1 (f2), while the contribution from the other is negligible thanks to the effective sound-blocking effect by the corresponding spectral filters, enabling independent modulation on each frequency channel with low crosstalk, as demanded in our mechanism.

The numerically simulated results in Fig. 4a demonstrate the ability of our designed meta-pixel in achieving nearly decoupled control of the phase and amplitude DoF, enabling independent tuning of each across its full range by varying only a single structural parameter. This substantially reduces the complexity of the metasurface design. The slight fluctuations observed in the amplitude and phase distributions may result from weak contributions of parameters other than \({H}_{4}^{1,2}\) and \({H}_{5}^{1,2}\), which are not considered in the current study for the sake of simplifying the theoretical calculations and structural design. Then, we select 4 discrete amplitude values and 8 discrete phase values to form 4 × 8 amplitude and phase combinations, thereby establishing a corresponding structural parameter library, as shown in Fig. 4b. Such an amplitude and phase discretization is precise enough to accurately mold the wavefront and achieve high-quality sound field reconstruction (see Supplementary Note 5 for the comparison of imaging quality with different discretization orders). Notice that the number of frequency channels can be further boosted by increasing the state density of the hybrid meta-pixel (see Supplementary Note 6 for another example of 3 frequency channels).

a Transmitted amplitude and phase vary with the combination of \([{D}_{4}^{1},{H}_{6}^{1}]\) (top) and \([{D}_{4}^{2},{H}_{6}^{2}]\) (bottom), at 13720 Hz and 17150 Hz. Superscript 1 (2) represents the subunit 1 (2). b Structural parameter libraries of combinations of \([{D}_{4}^{1},{H}_{6}^{1}]\) (top) and \([{D}_{4}^{2},{H}_{6}^{2}]\) (bottom) corresponding to 4×8 combinations of transmitted amplitude and phase at 13720 Hz and 17150 Hz. The radial and angular axes represent transmission amplitude and phase, respectively.

Experimental realization of the high-capacity encrypted holography

Next, we will experimentally demonstrate the proposed mechanism for high-capacity double-key-secured sound holography. Four digits of Arabic numerals from 1 to 4 are selected as the target and encoded in four channels containing two frequency channels (f1 = 13720 Hz and f2 = 17150 Hz) and two OAM channels (topological charges of ±1). Specifically, numeral 1 is encoded on the OAM beam with a topological charge of l = +1 at f1, denoted as the channel (f1; l = +1). Similarly, numerals 2, 3, and 4 are encoded on channels (f1; l = −1), (f2; l = +1), and (f2; l = −1), respectively. The four images are distributed across two distinct regions on the same imaging plane, with numerals 1 and 3 in one region and numerals 2 and 4 in the other. According to the method discussed above, we can easily calculate the required transmitted amplitude and phase profiles of the hologram metasurface for reconstructing holographic images at different frequencies, without any sophisticated optimization algorithm, as shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5b shows the fabricated metasurface sample comprising 40 × 40 meta-pixels via three-dimensional (3D) printing technology at 0.1 mm precision, whose overall geometric size is 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.06 m3. This number of unit cells provides sufficient DoFs to enable a high-quality hologram while simultaneously preserving the system’s compactness. To exclude the influence of unwanted reflection waves, the experiment is conducted in an anechoic chamber. As shown in Fig. 5c, OAM beams are emitted from a circular speaker array with a radial size of 0.12 m and spread towards the receiving metasurface over a distance of 1.2 m. In experiment, we first measured the reconstructed two-dimensional holographic sound field in a 0.4 × 0.4 m2 square region 0.15 m behind the metasurface. The one-dimensional acoustic intensity profiles at some specific positions marked by the dashed lines in Fig. 5d were also measured. During the measurement, a 1/4-in. free-field microphone (Brüel & Kjær type-4961) fixed on a 3D stepping motor is used to measure the acoustic intensity distribution point by point.

a Theoretically calculated transmitted amplitude and phase profiles of the hologram metasurface for reconstructing the desired holographic images at 13720 Hz (top) and 17150 Hz (bottom). The amplitude is plotted in arbitrary units (arb. units). b Photograph of the fabricated metasurface sample. The size of the sample is 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.06 m3. c Experimental setup. d Left panel: Simulated (Sim.) two-dimensional acoustic intensity distribution under different OAM and frequency incidences; Middle panel: experimental (Exp.) two-dimensional acoustic intensity patterns under different OAM and frequency incidences; Right panel: simulated (dashed line) and measured (solid line) one-dimensional acoustic intensity profiles along dashed lines marked in the left panel.

As presented in Fig. 5d, the experimentally measured two-dimensional acoustic intensity distributions and one-dimensional profiles on the image plane agree well with the simulated results, which both demonstrate the high-quality reconstruction of four Arabic numerals under the specific combination of topological charges and frequencies. This not only shows the ability of the metasurface to effectively modulate the multiple DoFs of sound waves including the OAM and frequency, but also manifests the high-security of our mechanism since holographic pattern information stored in the metasurface can only be released by the incident wave with a specific OAM mode and frequency. In addition, the frequency crosstalk is significantly suppressed, as indicated by the fact that nearly no artifacts can be observed in both simulated and experimental results. Besides, we also showcase in Supplementary Note 7 a more complex case in which all target images fully overlap on the same imaging plane. We select four alphabet letters as the targeted patterns. The simulated and measured results in Supplementary Fig. 14 still exhibit good quality, validating the potential for further increasing information capacity and the mechanism’s independence from the spatial arrangement of the multiplexed images. Moreover, to demonstrate the potential technical advancements enabled by our mechanism, we present in Supplementary Note 7 a representative example of OAM- and frequency-dependent particle assembly, which manifests the significant advantages of our methodology in flexible and diversified sound force manipulation. Beyond this, our mechanism also holds the promise for boosting advances in diverse applications, such as high-capacity encrypted communication and flexible sound wave 3D printing.

Discussion

In summary, we have proposed and experimentally demonstrated a high-capacity encrypted acoustic holography mechanism based on the multi-dimensional multiplexing acoustic metasurface. We theoretically derive the acoustic response of the metasurface for introducing the dual-multiplexing dimensions of OAM and frequency. As a practical implementation, an acoustic structural design of meta-pixels is proposed to modulate all-dimensional information of sound, including amplitude, phase, frequency, and OAM. Thanks to this high-DoF characteristic, the multiplexed metasurface consisting of such meta-pixels enables high-capacity information storage of multiple images with subwavelength spatial resolution and low-frequency crosstalk. We validate our approach through theoretical analysis, numerical simulations, and experimental measurements. All results turn out to be in close alignment with the expected. We anticipate our technology will contribute to the advancement of high-information-capacity acoustic holography and open up new possibilities for underwater communication, ultrasound diagnostics, and treatment.

Method

Numerical simulation

Throughout the paper, the simulations are performed with a finite element method based on COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS 6.1 software. Air is set to be the background medium, for which the mass density and sound speed are 1.21 kg/m3 and 343 m/s, respectively. The material for fabricating the metasurface is UV resin whose mass density and sound speed are 1400 kg/m3 and 2000 m/s, respectively.

Experimental configuration

The experiment is performed in an anechoic room to eliminate any disturbance of reflected sound. The metasurface samples are manufactured via 3D printing technology (0.1 mm in precision). At the emitting end, eight HiVi B1S loudspeakers are arranged axisymmetrically along a 12 cm-radius circle and mounted onto an acrylic glass plate, forming a single-ring circular phased array. A single-chip microcomputer, Arduino Mega 2560, is used to generate the drive signal of each loudspeaker. To emit an acoustic vortex beam with l-th order OAM mode, the phase of the drive signal to each speaker should be φ = lθ, where θ is the azimuthal angle between the speaker and the reference. The metasurface is placed in alignment with the single-ring circular phased array at a relative distance of 1.2 m. At the imaging plane, a microphone (Brüel & Kjær type-4961) is mounted on a 3D stepping motor to measure the pressure field. The scanning step is set to sampling interval d for the two-dimensional sound field measurement and to 1 cm for the one-dimensional acoustic pressure profile measurement, respectively. The signals are recorded with a Brüel&Kjær PULSE3160-A-042 2-channel analyzer. For two-dimensional spatial scanning, the initial scan position is aligned with the center of the first pixel of the hologram image.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All technical details for implementing the simulation are provided in the Manuscript and Supplementary Information. Codes are available from the corresponding authors J.L., B.L., or J.C. upon request.

References

Melde, K., Mark, A. G., Qiu, T. & Fischer, P. Holograms for acoustics. Nature 537, 518–522 (2016).

Yu, W. J. et al. Acoustography by beam engineering and acoustic control node: BEACON. Adv. Sci. 11, 2403742 (2024).

Gu, Y. et al. Acoustofluidic holography for micro- to nanoscale particle manipulation. ACS. Nano. 14, 14635–14645 (2020).

Namin, B. G. & Hojjat, Y. Remote control of fluid motion in a channel by acoustic holography. Ultrasonics 140, 107303 (2024).

Lin, Q. et al. Acoustic hologram–induced virtual in vivo enhanced waveguide (AH-VIEW). Sci. Adv. 10, eadl2232 (2024).

Marzo, A. & Drinkwater, B. W. Holographic acoustic tweezers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 84–89 (2019).

Jiménez-Gambín, S., Jiménez, N., Benlloch, J. M. & Camarena, F. Holograms to focus arbitrary ultrasonic fields through the skull. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 014016 (2019).

Long, B., Seah, S. A., Carter, T. & Subramanian, S. Rendering volumetric haptic shapes in mid-air using ultrasound. ACM Trans. Graph. 33, 1–10 (2014).

Hirayama, R., Martinez Plasencia, D., Masuda, N. & Subramanian, S. A volumetric display for visual, tactile and audio presentation using acoustic trapping. Nature 575, 320–323 (2019).

Zou, H. Y. et al. Acoustic metagrating holograms. Adv. Mater. 36, e2401738 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. A review of tunable acoustic metamaterials. Appl. Sci. 8, 1480 (2018).

Cummer, S. A., Christensen, J. & Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16001 (2016).

Chen, Y. & Hu, G. Broadband and high-transmission metasurface for converting underwater cylindrical waves to plane waves. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044046 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. Fine manipulation of sound via lossy metamaterials with independent and arbitrary reflection amplitude and phase. Nat. Commun. 9, 1632 (2018).

Memoli, G. et al. Metamaterial bricks and quantization of meta-surfaces. Nat. Commun. 8, 14608 (2017).

Jin, Y. B., Kumar, R., Poncelet, O., Mondain-Monval, O. & Brunet, T. Flat acoustics with soft gradient-index metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 10, 143 (2019).

Li, Y., Liang, B., Gu, Z. M., Zou, X. Y. & Cheng, J. C. Reflected wavefront manipulation based on ultrathin planar acoustic metasurfaces. Sci. Rep. 3, 2546 (2013).

Zhang, H. K. et al. Creation of acoustic vortex knots. Nat. Commun. 11, 3956 (2020).

Kim, J., Kasoji, S., Durham, P. G. & Dayton, P. A. Acoustic holograms for directing arbitrary cavitation patterns. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 051902 (2021).

Fan, S.-W. et al. Broadband tunable lossy metasurface with independent amplitude and phase modulations for acoustic holography. Smart Mater. Struct. 29, 105038 (2020).

Akram, M. T., Jang, J. Y. & Song, K. Forward and backward multibeam scanning controlled by a holographic acoustic metasurface. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 24008 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Static passive meta-sonar for dynamic sound beam scanning. Sci. Bull. 68, 1862–1866 (2023).

Xu, M., Harley, W. S., Ma, Z., Lee, P. V. S. & Collins, D. J. Sound-speed modifying acoustic metasurfaces for acoustic holography. Adv. Mater. 35, e2208002 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Acoustic holographic rendering with two-dimensional metamaterial-based passive phased array. Sci. Rep. 6, 35437 (2016).

Wang, H. P. et al. Ultrathin acoustic metasurface holograms with arbitrary phase control. Appl. Sci. 9, 3585 (2019).

Li, W., Lu, G. & Huang, X. Acoustic hologram of the metasurface with phased arrays via optimality criteria. Mech. Syst. Signal Pr. 180, 109420 (2022).

Miao, X.-B. et al. Deep-learning-aided metasurface design for megapixel acoustic hologram. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 021411 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Systematic design and experimental demonstration of transmission‐type multiplexed acoustic metaholograms. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2101947 (2021).

Zeng, L. S. et al. High-resolution manifold acoustic holography based on high-pixel-array binary metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. 37, e2420229 (2025).

Lin, Q. et al. Multi-frequency acoustic hologram generation with a physics-enhanced deep neural network. Ultrasonics 132, 106970 (2023).

Zhu, Y. & Assouar, B. Systematic design of multiplexed-acoustic-metasurface hologram with simultaneous amplitude and phase modulations. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 045201 (2019).

Ye, W. M. et al. Spin and wavelength multiplexed nonlinear metasurface holography. Nat. Commun. 7, 11930 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Reflective chiral meta-holography: multiplexing holograms for circularly polarized waves. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 25 (2018).

Xu, H. X. et al. Wavevector and frequency multiplexing performed by a spin-decoupled multichannel metasurface. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 1900710 (2020).

Zhou, H. Q. et al. Polarization-encrypted orbital angular momentum multiplexed metasurface holography. ACS. Nano. 14, 5553–5559 (2020).

Gou, Y. et al. Non-interleaved polarization-frequency multiplexing metasurface for multichannel holography. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201142 (2022).

Jiang, X., Liang, B., Cheng, J. C. & Qiu, C. W. Twisted acoustics: metasurface-enabled multiplexing and demultiplexing. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800257 (2018).

Liu, J. J., Liang, B., Yang, J., Yang, J. & Cheng, J. C. Generation of non-aliased two-dimensional acoustic vortex with enclosed metasurface. Sci. Rep. 10, 3827 (2020).

Liu, J.-J., Ding, Y.-J., Wu, K., Liang, B. & Cheng, J.-C. Compact acoustic monolayered metadecoder for efficient and flexible orbital angular momentum demultiplexing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 213502 (2021).

Sun, Z. Y. et al. Underwater acoustic multiplexing communication by pentamode metasurface. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 205303 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Twisting linear to orbital angular momentum in an ultrasonic motor. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201575 (2022).

Wang, W., Liu, J., Liang, B. & Cheng, J. Controlling acoustic orbital angular momentum with artificial structures: from physics to application. Chinese Phys. B 31, 094302 (2022).

Wu, K. et al. Metamaterial-based real-time communication with high information density by multipath twisting of acoustic wave. Nat. Commun. 13, 5171 (2022).

Liu, J., Li, Z., Liang, B., Cheng, J.-C. & Alu, A. Remote water-to-air eavesdropping with a phase-engineered impedance matching metasurface. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301799 (2023).

Ren, H. et al. Complex-amplitude metasurface-based orbital angular momentum holography in momentum space. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 948–955 (2020).

Ren, H. et al. Metasurface orbital angular momentum holography. Nat. Commun. 10, 2986 (2019).

Fang, X. et al. High-dimensional orbital angular momentum multiplexing nonlinear holography. Adv. Photonics 3, 015001 (2021).

Fang, X., Ren, H. & Gu, M. Orbital angular momentum holography for high-security encryption. Nat. Photonics 14, 102–108 (2019).

He, G. et al. Multiplexed manipulation of orbital angular momentum and wavelength in metasurfaces based on arbitrary complex-amplitude control. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 98 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1404402 to B.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12304493 to J.L.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grants No. BK20233001 to B.L. and No. BK 20230767 to J.L.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. KG202501 to J.L.), High-Performance Computing Center of Collaborative Innovation Center of Advanced Microstructures and A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. J.L. acknowledges the support from Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (Grant No. 2023QNRC001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and B.L. conceived the idea; Y.Z., F.L., and W.W. performed the theoretical simulations; Y.Z., F.L., K.W., and J.L. designed and carried out the experiments; Y.Z., F.L., J.L., B.L., and J.C. wrote the paper; J.L., B.L., and J.C. guided the research. All authors contributed to data analysis and discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yabin Jin, Tony Huang, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Yq., Li, F., Wu, K. et al. Orbital angular momentum- and frequency-dependent high-capacity encrypted hologram through multi-dimensional multiplexing acoustic metasurface. Nat Commun 16, 11692 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66793-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66793-7