Abstract

Compared to the well-known polar amplification in a warmer or cooler world, the trend of tropical surface air temperature gradient is frequently overlooked. Through analyzing various observations, assimilation data, proxy data, and modeling, here we show that annual- and zonal-mean tropical (30oS-30oN) meridional surface air temperature gradient (TMSTG) exhibits small changes in a wide range of climates from extremely cold to extremely hot. This phenomenon is robust to CO2 concentration, solar constant, land-sea configuration, vegetation coverage, heat transport, and cloud parameterization. The quasi-invariance of the TMSTG is maintained by the small gradient of incoming solar radiation and by the dynamics of horizontal weak temperature gradient (WTG) and convective moist adiabat (CMA) in the tropics. When planetary obliquity or rotation period is increased, the quasi-invariant region becomes larger. TMSTG’s quasi-invariance is a fundamental and useful law that can be used to reconstruct or predict Earth’s tropical climate in the past and future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meridional surface air temperature gradient has important effects on the climate system through affecting the Hadley and Ferrel cells, subtropical and midlatitude jets, eddies and waves, and polar ice and snow coverages1,2,3,4,5,6. In general, the equator-to-pole surface temperature gradient becomes larger in a cooler climate and smaller in a warmer climate, with the high latitudes being more sensitive than low latitudes, known as “polar amplification”2,7,8,9. Besides the widely known sea ice and snow albedo feedback, poleward energy transport, cloud feedback, water vapor feedback, lapse rate feedback, and Planck feedback also contribute to the polar amplification10,11,12,13. Contrast to the polar amplification, here we show that zonal-mean tropical meridional surface temperature gradient (TMSTG) nearly does not change in a wide range of climates. This finding has critical implications for reconstructing past climate and predicting future climate change.

Tropical surface temperature gradient is much smaller than that in the middle and high latitudes. For example, under the present-day climate, the equator-to-30°S/N zonal-mean surface temperature difference is ~6.6 °C whereas it is ~20.1 °C for 30°S/N to 60°S/N and ~30.5 °C for 60°S/N to 90°S/N. More importantly, the changes of TMSTG under external forcings such as increasing CO2 are very small. In observations, the surface temperature changes in the tropics from 30°S to 30°N are nearly uniform during the last few decades14. In the doubling CO2 experiment using the model EC-Earth, the warming magnitude at 30°S/N, ~1.9 °C, is very close to that at the equator, ~2.0 °C (Fig. 1 in ref. 15). In abrupt 4×CO2 experiments, the multimodel-mean warming magnitude at 30°S(N), 5 °C, is nearly the same as that at the equator (Fig. 2c of ref. 16). Similar phenomenon of the small change in surface temperature gradient between the equator and 30°S/N was found in other studies of global warming10,14,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, the range of the climate states investigated in their studies is narrow, within ~7 K in global mean compared to present. Due to the narrow range of the climates investigated in previous studies, the small change of the TMSTG was usually viewed as a coincidence rather than as a physical rule; as a result, the trend of TMSTG was usually overlooked. An exception is the study by ref. 19, within which the highest CO2 concentration examined is 16 times the pre-industrial (PI) level and the changes in tropical surface temperature are about 10–12 °C. However, ref. 19 focused on the hemispheric asymmetry in polar warming amplification rather than tropical surface temperature responses. In this study, the range of CO2 concentration covers from 0.04 times to 28 times PI, and the changes of tropical surface temperature reaches 30 °C, much larger than that in previous studies.

Circles: between the equator (5°S-5°N average) and 30°S/N (TSeq-30); triangles: between the equator and 60°S/N (TSeq-60); diamonds: between the equator and 90°S/N (TSeq-90). The gray dashed line, with a slope of −0.08 and an intercept of 6.95, is the linear regression between TSeq-30 and global-mean surface temperature (GMST). Different colors represent different datasets. More details about the datasets are shown in the “Methods”.

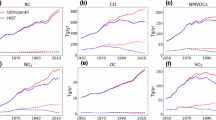

a Surface temperature changes between 2013–2022 and 1979–1988 in National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) and ECMWF Reanalysis 5th Generation (ERA5) reanalysis data; b surface temperature differences between Last Glacier Maximum (LGM)/Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) and pre-industrial (PI) in modeling data and assimilation data; c differences between abrupt 4×CO2 and PI experiments in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) simulations. d–f are paleo-climate modeling data from ref. 31: d zonal-mean surface temperatures, e surface temperature differences between different periods and PI, and (f) zonal-mean surface temperature gradient in units of oC km-1. In panels (d)-(f), lines in cool colors represent relatively cold climates, and lines in warm colors represent relatively hot climates. Gray shading indicates the tropical region where we focus.

Whether the independent feature of the TMSTG to background state can be applied to much cooler or hotter climates is unknown. Under large external forcings, the spatial distributions of land-sea configuration, cloud feedback, and ocean heat transport in the tropics may change. For example, if more lands locate at the subtropics than that at the deep tropics or vice versa, the meridional gradient of surface albedo can change significantly. Under this condition and other similar changes, it is important to know whether the meridional gradient of surface air temperature will also have large responses. Here, we plan to uncover this mystery through multivariate data analyses, energy budget analyses, and sensitivity and mechanism-denial experiments for a wide range of climates.

We explore the changes of TMSTG when the background climate states undergo very large changes, from 6.2 to 36.1 °C in global mean. We focus on annual- and zonal-mean properties and ignore west-to-east difference (such as the warm pool—cold tongue contrast), basin-specific changes (such as the tropical Pacific), land-sea contrast, and the warming asymmetry between the two hemispheres, which were investigated in past works such as refs. 23,24,25,26. We use TSeq-30, defined as the averaged surface temperature in the belt of 5°S-5°N minus the averaged surface temperature at 30°S and 30°N, to quantify the TMSTG. Multiple datasets, including observations, proxy data, assimilation data, and modeling (see “Methods”) are employed in this study. The TMSTG remains largely unchanged despite the great fluctuations in global-mean surface temperature (Fig. 1).

Results

Small changes of TMSTG in a wide range of climate states

Figure 1 shows the surface temperature differences between the equator and other latitudes (30°S/N, 60°S/N, and 90°S/N) in different datasets. Among all the datasets, the global-mean surface temperature varies from 6.2 to 36.1 °C. Clearly, the changes of TSeq-30 are much smaller than that between the equator and 60°S/N or 90°S/N. The statistical slope of the linear regression of TSeq-30 and global-mean surface temperature is −0.08 (gray dashed line in Fig. 1), meaning that for each 50 °C increase or decrease in global-mean surface temperature, TSeq-30 would change by only 4.0 °C. Meanwhile, among the different datasets, there are significantly divergences in the surface temperature difference between the equator and 60°S/N or between the equator and 90°S/N, but the trend in TSeq-30 is very consistent.

The small change of TSeq-30 is robust. Two groups of reanalysis data (Figs. 1 and 2a), three groups of assimilation data (Figs. 1 and 2b), three groups of proxy data, and 14 groups of numerical global-climate experiments (Figs. 1 and 2c) are used in the analyses. The proxy data consists of seven different periods, ~70, 50, 30, 5 million years ago (Ma), Last Glacier Maximum (LGM; ~21,000 years ago), Holocene (~6000 years ago), and Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM; ~56 Ma)8,27,28. The assimilation data include three different periods, LGM, Holocene, and PETM. CO2 concentration in the numerical simulations covers a wide range, from 10 to 3374 ppmv in Valdes’s study29 and from 280 to 7840 ppmv in Li’s study30, as well as solar constant from 1305 to 1365 W m−2 in Valdes’s study29 and from 1302 to 1361 W m−2 in Li’s study30. Various fully coupled atmosphere-ocean models are used, including CESM1.2, HadCM3, and 17 models in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). This implies that the conclusion does not depend on the models used, especially on convection and cloud parameterization schemes.

In all these climates, not only the global-mean surface temperature, but also other components of the climate system such as global monsoon pattern related to the large changes of land-sea configuration, the strengths of the Hadley cells and Walker circulation, the location of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), the strengths of baroclinic instability and jets, the strength and/or direction of wind-driven and thermohaline circulations, and the coverages of polar ice and snow, vary dramatically8,29,31,32,33,34,35,36, but the TMSTG exhibits small decreases or increases. This indicates that the tropical zonal-mean surface temperature gradient is not determined by the details of the above processes and is mainly determined by some simple factors or processes.

A clear example for the insensitivity of the TSeq-30 is shown in Fig. 2d–f from the simulation data of the climate evolution during the past 540 million years30. The changes of land-sea configuration and CO2 concentration are quite large in their experiments. The global-mean surface temperature ranges from 12.7 °C for 290 Ma to 26.4 °C for 480 Ma, and the equator-to-pole surface temperature difference varies from 59.2oC for the pre-industrial period (PI) to 22.3 °C for 230 Ma (Fig. 2e). However, the changes of TSeq-30 are small, within 3.1 °C as shown in Fig. 2e; this can also be clearly seen from Fig. 2f, which shows the meridional surface temperature gradient in units of oC per km. In this wide range of climate states, the changes of tropical surface temperature gradient are within 0.2 °C per 100 km, whereas the changes in the high latitudes are 5–10 times larger, reaching 1.0–2.0 °C per 100 km.

Underlying mechanisms

The two main mechanisms of the quasi-invariance of the TMSTG are the meridional distribution of solar radiation and the key dynamical processes of constraining the tropical climate: weak temperature gradient (WTG) and convective moist adiabat (CMA), as illustrated in Fig. S1.

For the incoming solar radiation, its tropical meridional gradient of modern Earth is small. At the equator, the annual-mean incoming solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere (TOA) is 415 W m−2 while it is 361 W m−2 at 30°S/N, indicating a difference of 54 W m−2 or 13% of the equatorial value. If the effect of a planetary albedo of ~0.3 is included, the difference decreases from 54 to 38 W m−2. The underlying reason is the moderate obliquity of modern Earth (23.3°) and thereby the incoming solar radiation is approximately a cosine function of latitude, which has small gradients at low latitudes. In historical Earth, for all the datasets shown in Fig. 1, the changes of planetary obliquity and eccentricity are small, within 2° and 0.06, respectively. Therefore, the changes of the meridional gradient of the incoming solar radiation are tiny even when solar constant changes greatly (Fig. 3a).

a Incoming solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere (TOA). b The net shortwave radiation flux at the surface. c Air temperature at 500 hPa (other levels in the free troposphere have the same trend, shown in Fig. S4). d Changes in air temperature at 500 hPa, relatively to the pre-industrial (PI) experiment. e Changes in clear-sky greenhouse effect at TOA. f Changes in downward longwave radiation flux at the surface. In (a–c), the black line is for the ERA5 reanalysis data for the period of 2013–2022. All other data are from CESM1.2 simulations from 540 Ma to PI. All variables are for zonal and annual mean. The clear-sky greenhouse effect (\({G}_{c}\)) is defined as the difference between surface upwelling longwave flux and clear-sky outgoing longwave radiation at TOA (OLRc), \({G}_{c}\equiv \sigma {{T}_{s}}^{4}-{OLRc}\), where \({T}_{s}\) is surface temperature and \(\sigma\) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant.

At the surface, after being scattered and absorbed by atmosphere and clouds, the meridional gradient of tropical solar radiation becomes even smaller than that at TOA (Fig. 3b). The cloud shortwave radiative effect (negative, reflecting back to the space) in the deep tropics (between ~15°S and 15°N) is relatively higher than that in the subtropics (Fig. 2a, b). The deep tropics is the region where deep convection and large-scale upwelling motions (related to the Hadley cells) occur, so that more clouds form there. The clear-sky shortwave absorption by the air (positive) in the deep tropics is also relatively greater than that in the subtropics (Fig. S2c), mainly because the deep tropics has higher water vapor concentration. As a result, both the cloud shortwave radiative effect and the shortwave absorption by water vapor act to reduce the meridional solar radiation gradient, making the surface shortwave radiation in the tropics being more uniform than that at TOA.

Correspondingly, the forced changes of surface temperature gradient due to the change in solar radiation are teeny, within 0.8 °C (Fig. S3a; also see ref. 33). If the obliquity is artificially increased from 23.3° to 40° with all other factors being unchanged and thereby the meridional gradient of incoming solar radiation weakens, the value of TSeq-30 decreases greatly from 10.8 to 4.9 °C (Fig. 4a, b for an aqua-planet with no meridional ocean heat transport). Meanwhile, the meridional range of the small change of the TMSTG expands poleward. When the obliquity is artificially decreased from 23.3° to 0°, TSeq-30 increases (Fig. 4b).

a Incoming solar radiation in the experiments of changing obliquity (0°, 23.3°, and 40°). Surface temperatures in the experiments of (b) changing obliquity, (c) changing ocean heat transport (OHT; 100%, 40% and 0% of pre-industrial level), (d) turning off cloud radiative effects, and (e) changing planetary rotation rate (4, 1, and 1/10 of modern rate (Ωe)). f Air temperatures at 500 hPa in the experiments of changing planetary rotation rate. In each group, the CO2 concentration is the same except the dashed lines. The black dashed line in (b) is an experiment in which the obliquity is 23.3°, but the CO2 concentration is increased from 1120 (solid lines) to 2240 ppmv (dashed line). The red dashed lines in (e, f) is for the experiment of the rotation rate being Ωe/10, but CO2 concentration is increased from 280 (solid lines) to 1120 ppmv (dashed line). The vertical dotted lines in (e) indicate the corresponding latitudes where the surface temperature difference between the equator and the specific latitude is 8 °C. All the sensitivity experiments are performed using a slab-ocean model; the varying obliquity experiments (a, b) are under an aqua-planet configuration with no lands, and the other experiments are with modern Earth’s land-sea configuration (see “Methods”).

For the dynamical processes, in horizontal direction, due to the smallness of the Coriolis force within 30° of both hemispheres, large free-tropospheric temperature gradients cannot be sustained, and gravity waves and the Hadley cells are effective to homogenize the horizontal air temperature, named as the WTG approximation37,38,39,40,41. Any perturbation in isobaric surface cannot be maintained by the balance between the Coriolis force and pressure gradient but otherwise will be eventually diminished by the outward propagation of gravity waves and the effect of the Hadley cells on horizontal heat transport.

In the vertical direction, the free troposphere above the planetary boundary layer nearly follows CMA in the tropics from the equator to 30°S/N of all the climate states (Fig. S5). Why is the subtropical temperature profile close to moist adiabat, given that the subtropics (from ~15°S/N to 30°S/N) is in large-scale downwelling motions? Several processes influence the air temperature in the subtropical regions, including adiabatic compression heating related to large-scale downwelling, radiative cooling associated with atmospheric longwave emission to the space, and horizontal heat transport/adjustment related to the Hadley cells, eddies, and internal gravity waves. In Chapter 18.4 in ref. 40, the author stated that: “In a process analogous to geostrophic adjustment, internal waves propagating away from convection maintain weak horizontal temperature gradients and ensure that the lapse rate does not deviate too far from saturated adiabatic anywhere in the tropics”.

Due to the combined dynamical constraints of WTG and CMA, any change of air temperature (increasing or decreasing) in the free troposphere should link to a change in surface temperature, and vice versa. Therefore, the changes of free-tropospheric air temperature and surface air temperatures are nearly uniform in the tropics (Figs. 3c, d and 2d).

Another view to understand the quasi-invariance of the TMSTG is radiation transfer. The change of zonal-mean clear-sky greenhouse effect (\({G}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\)) and of the downward longwave radiation at the surface in different climate states exhibit a meridional uniform pattern in the south-north direction (Fig. 3e, f). The variation of \({G}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) is contributed by the changes in greenhouse gas concentrations (mainly water vapor and CO2), vertically-mean air temperature, and lapse rate. Detailed analyses are shown in Fig. S6. The mixing ratios of CO2, CH4 and N2O are nearly uniform in both horizontal and vertical directions at least in the troposphere. Water vapor concentration roughly follows the Clausius–Clapeyron relation, and thereby its greenhouse effect has a peak over the equator. However, the lapse rate feedback is negative and has a valley over the equator, which compensates the meridional heterogeneity in water vapor greenhouse effect. The strong negative lapse rate feedback in the tropics is caused by the amplification of upper-tropospheric warming in a warmer climate42,43. The strength of temperature feedback is basically constant in the tropics. The direct CO2 forcing in the subtropics is relatively higher than that in the deep tropics, due to the masking effect of high-concentration water vapor and deep convective clouds in the deep tropics44. Overall, due to the above compensation processes, the clear-sky greenhouse effect exhibits a uniform pattern in the tropics. Thereby, the corresponding forced tropical surface temperature changes are nearly uniform (Fig. S3b). Moreover, in different climate states, the changes of clear-sky greenhouse effect are several to ten times larger than that of other factors such as cloud radiative effect and meridional heat transport (see also Figs. S3c–e, Fig. 6 in ref. 33, and Fig. S2 in ref. 45).

Figure S7 shows the annual- and zonal-mean effective emission level of the climate system (atmosphere and surface), and the differences in the effective emission level between each paleoclimate experiment and PI experiment. The effective emission temperature is calculated as: \({T}_{{{\rm{e}}}}={({OLR}/\sigma )}^{\frac{1}{4}}\) where \({OLR}\) is the outgoing longwave radiation and \(\sigma\) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, and the effective emission level is the pressure where the air temperature is equal to the effective emission temperature. It is clear that the emission pressure level in different latitudes is not the same and it has large changes among different experiments, but the changes between different experiments are nearly uniform, especially in the tropics. This again suggests that the changes of tropical air temperature and surface air temperature should be nearly uniform.

From Figs. 3c and S4, one can find that the WTG region is limited to between 20°S and 20°N. However, the quasi-invariance of the TMSTG can extend to 30°S and 30°N (Figs. 1 and 2). This implies that the combined effect of the three key factors (shortwave radiation, WTG and CMA) can make the response of the surface air temperature to external forcing(s) be more uniform than that suggested by the WTG only. Therefore, in this paper, we focus on the region from 30°S to 30°N, not limited to the range from 20°S to 20°N only.

If planetary rotation rate is decreased, the WTG region becomes wider and the value TSeq-30 decreases substantially. When the planetary rotation rate is decreased to 1/10 of modern value, the WTG region expands from ~30°S/N to ~60°S/N (Fig. 4f), and the meridional range of the small change of the TMSTG also expands poleward (red dashed line versus red solid line in Fig. 4f). Meanwhile, the width of the Hadley cells exhibits the same trend (Fig. S8), because the latitudinal boundary of the Hadley Cell is inversely proportional to the rotation angular velocity40,46. The expansion of the Hadley cells transports more energy poleward, also acting to extend the WTG area.

Besides of the incoming solar radiation and clear-sky greenhouse effect, changes in other factors, including surface albedo, cloud feedback, and meridional heat transport, can also influence the TMSTG, but their effects are small. Three examples are shown in Fig. S9, including the 480 Ma experiment within which almost all of the continents were joined together in the Southern Hemisphere (named as the Gondwana supercontinent), the 250 Ma experiment within which all major lands were assembled into one continent in the low and middle latitudes (known as the Pangea supercontinent), and the 10 Ma experiment within which the land-sea configuration is close to modern Earth. For all these three experiments, CO2 concentration is 2800 ppmv and solar constant is the same as modern Earth (1361 W m−2), so the results are ready to more clearly exhibit the effect of varying land-sea configuration.

As shown in Fig. S9e, surface albedo changes dramatically among the three experiments due to the migration of the continents and the changes of land vegetation distributions, but surface temperature and its meridional gradient nearly do not change in the tropics. The underlying mechanism is that planetary albedo nearly does not change (Fig. S9f), which in turn is due to the fact that ~88% of planetary albedo is contributed from atmospheric processes, and surface albedo makes a small contribution (Fig. S10). Atmospheric processes (mainly shortwave absorption/scattering and cloud reflection) greatly attenuate the contribution of surface to planetary albedo47.

The global ocean overturning circulation and therefore meridional ocean heat transport changes largely in these three experiments (Fig. S9i–l), but they also have a small effect on the TMSTG (Fig. S9d). In order to further verify the effect of ocean heat transport, we did several sensitivity experiments: As the ocean heat transport is reduced to 40% of the modern level or even zero, the value of TSeq-30 increases from 8.0 to 11.1 °C or 12.7 °C, respectively (Fig. 4c). These results indicate that the change of ocean heat transport does affect the TMSTG, but its effect is limited within ~4.7 °C. Moreover, the changes of tropical cloud radiative effects are small (Figs. S3 and S9g). If the cloud radiative effects were artificially turned off, the surface is ~20.3 °C hotter in global mean, but the value of TSeq-30 exhibits a small decrease (Fig. 4d). These sensitivity experiments further confirm the robustness of the quasi-invariance of the TMSTG.

Discussion

We find that the changes of tropical meridional surface zonal-mean air temperature gradient under different climate states are small in a wide range of climate states. Analyses and sensitivity experiments suggest that the quasi-invariance of the TMSTG is robust to the data used (observation, proxy, assimilation, and simulation) and to various factors such as the type of external radiative forcing (CO2 concentration or solar constant), land-sea configuration, land vegetation coverage, and the strength of cloud radiative effect.

The main factors dominating the quasi-invariance of the tropical surface temperature gradient are the weak gradient of tropical solar radiation and two tropical dynamical processes: WTG and CMA. The dynamical processes cause the clear-sky greenhouse effect at the top of the atmosphere and the downward longwave radiation flux at the surface to be nearly uniform in the tropics.

Earth climate is a very complex system, so it is extremely difficult but important to find the fundamental rules. Here we uncover one of the rules. Until now, we have not found any other paper that clearly concluded that the changes of tropical meridional surface air temperature gradient should be small under large external forcings. We believe that the reason is that most of previous studies employed relatively small changes of external forcings and meanwhile they focused on the polar amplification, the warming contrast between land and ocean, or the warming asymmetry between the two hemispheres. The topic we discuss here was largely overlooked in previous studies.

Our finding is crucial because it can be used to reconstruct surface air temperature in the past as paleoclimate proxy data is always rare. For a certain period, as long as the zonal-mean surface temperature at one latitude in the tropics is known, the whole tropical zonal-mean surface temperature can be roughly estimated. The tropics (30°S-30°N) covers 50% area of Earth’s surface. This rule is also useful for predicting future climate change as it implies that the zonal-mean tropical meridional surface temperature gradient will not change much even under very large anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases. This rule can also be used to constrain the free parameter—diffusivity in one-dimensional (1D) or 2D simple energy balance models48, which do not solve the complex 3D atmospheric and oceanic circulations. For different climate states, energy balance model should obtain similar tropical surface temperature gradient through adjusting the value of the diffusivity. Other climate models should also be restricted by this rule.

Under what condition(s) will the quasi-invariance of the tropical meridional surface air temperature gradient fail? As shown above, the underlying three key processes for the quasi-invariance of the tropical meridional surface air temperature gradient are related to shortwave radiation, WTG, and CMA. For shortwave radiation, it mainly depends on the incoming solar radiation, so there will be no exceptions as long as the planetary obliquity does not change much (see Fig. 4).

Besides of the WTG, a more precise constraint on tropical climate is weak buoyancy or density gradient, which states the horizontal gradient of buoyancy or density should be small in the free troposphere of the tropics49,50,51. For atmosphere mixed with water vapor, the ideal gas equation can be written as p = \(\rho {R}_{{{\rm{d}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\), where p is air pressure, \(\rho\) is air density, \({R}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\) is the gas constant for dry air, and \({T}_{v}\) is the virtual temperature. For a given pressure (or isobaric plane), the \({T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\) is inversely proportional to \(\rho\), which is a measure of air buoyancy. So, \({T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\) can be used to represent buoyancy, and for a given pressure level, a high \({T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\) means a lower local buoyancy and vice versa. Therefore, weak buoyancy gradient implies that weak \({T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\) gradient in the tropical free troposphere. Fig. S11 shows that indeed the horizontal \({T}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\) gradient in the tropical free troposphere is small in a wide range of climates, especially in the latitudes between 20°S and 20°N.

For CMA, it will not change as long as the tropics or the deep tropics are in convection. The timescale of convection is always much shorter than that of large-scale circulation. For example, for modern Earth, the characteristic height of the tropical troposphere (\(H\)) is about 10 km, and the typical vertical velocity of the Hadley cells is about 6 \(\times\) 10−3 m s−1, so that the timescale of the Hadley cells is in the order of 20 days4. Based on mass conservation (or the mass continuity equation), this timescale can also be obtained based on the typical horizontal velocity of 2 m s−1 and the horizontal scale of 3330 km, from the equator to 30°S or 30°N. While the typical vertical velocity of convection is in the order of 1–10 m s−1, so that the timescale of convection is about 103–104 s, always much shorter than that of the large-scale circulation. Therefore, moist adiabatic profiles can persist as least in the deep tropics.

For WTG, the key process is the propagation of gravity waves over planetary scales. As long as the gravity wave propagation is much faster than other processes (such as Hadley circulations, eddies, or radiative transfer), the behavior of WTG can persist. The timescale of the gravity wave is equal to \(L/\sqrt{{gh}}\), where \(L\) is the horizontal scale (~3330 km, i.e., the width of the tropics in each hemisphere), \(g\) is the gravity, and \(h\) is the equivalent depth. For Earth’s deep tropics, the value of \(h\) is in the range of 12–50 m but can reach as high as 200 m under deep convective heating52. Therefore, the phase velocity of the internal gravity wave should be in the range of 10–45 m s-1, and thereby the timescale of the gravity wave propagation from the equator to 30°S or 30°N is about 7 \(\times\)104–3 \(\times\) 105 s. The timescale of longwave radiative cooling process in the atmosphere is approximately equal to \({c}_{{{\rm{p}}}}{{P}_{{{\rm{s}}}}} / 4g \sigma {{T}_{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{3}\), where \({c}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure, \({P}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\) is the surface pressure, \(\sigma\) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, and \({T}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\) is the effective temperature. For modern Earth, the radiation timescale is about 30 days. However, for extremely hot climate (such as \({T}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\) > 2000 K for hot Jupiters) or very thin atmosphere (such as \({P}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\) < 1000 Pa for Mars), the timescale of longwave radiative cooling will be comparable to or even less than the propagation timescale of gravity waves, so that the horizontal temperature gradient will be mainly determined by radiation processes rather than gravity wave adjustment53,54.

The above analyses suggest that the quasi-invariance of the tropical meridional surface temperature gradient can persist in a wider range of climates than that shown in this paper, but not for planets with very thin atmosphere or with temperature higher than about 2000 K. Future work is required to verify this speculation.

Methods

Observations

This study employs reanalysis data from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) reanalysis project and ECMWF Reanalysis 5th Generation (ERA5). The mean surface air temperatures in 1979–1988 and 2013–2022 are used in Figs. 1 and 2a. The horizontal resolution of the reanalysis data is 2.5° × 2.5° for NCEP reanalysis data and 0.25° × 0.25° for the ERA5 data. In this manuscript, we focus on surface air temperature. We have also analyzed surface skin temperature and found that it has the same trend.

Proxy data

The proxy data for seven distinct periods (~70, ~50, ~30, ~5 Ma, LGM, Holocene, and PETM) utilized in the present work are sourced from refs. 8,27,55. The global-mean surface temperatures of 70, 50, 30, and 5 Ma are from model simulations in ref. 30 since ref. 8 did not show the global-mean surface temperatures. For LGM and Holocene, the global-mean surface temperatures are calculated by the respective assimilation data. For PETM, the global-mean surface temperature is calculated by the simulation that can capture major climatic features of proxy data (with CO2 concentration of 2565 ppmv). TSeq-30 for each period is determined by averaging all the proxy data points in the 5°S-5°N belt and then subtracting the average of all data points between 25°S-35°S and 25°N-35°N (because the rareness of the data; note that for model simulation data, the values at 30°S/N are used, please see the main text). The members of proxy data points used are 2, 12, 5, 13, 68, 68, and 4 for the tropics, and 4, 9, 6, 18, 48, 53, and 2 for the subtropics. The error range of each period is calculated as follows: First, we calculate the root mean square of the errors for the equator and 30°. Then, using the error propagation formula, we get the error between the equator and 30° by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of these two errors. Note that the error ranges for 5 Ma in ref. 8 are missing.

Assimilation data

We utilize three groups of assimilation data from refs. 28,55,56. The data assimilation methods in these three studies are similar. They combined large collections of proxy data of sea surface temperature with climate models to generate a new reconstruction of temperatures. The climate model they used is iCESM, an extension of the Community Earth System Model (CESM) capable of simulating the transport and transformation of water isotopes in hydrological processes. The data assimilation technique is based on ensemble square-root Kalman filter. Reference 28 focused on the LGM and late Holocene (4–0 kyrs ago), and ref. 55 studied the PETM. Reference 56 focused on the climate evolution from LGM to present, with time intervals of 200 years. The horizonal resolution of all three groups of assimilation data is 2.5° × 0.9° in longitude-latitude.

CMIP6

The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project is sponsored by the Working Group on Coupled Modeling (WGCM) and is currently in its 6th phase (CMIP6). This study uses the abrubt-4×CO2 experiments (forced by an abrupt quadrupling of CO2 at year 1) and pre-industrial control experiments (piControl). A total of 27 experiments from 17 models are analyzed. The final 50 years (years 101–150) of the abrubt-4×CO2 experiments are used. In Fig. 2, we compare each abrubt-4×CO2 experiment with equilibrium state of corresponding model’s piControl experiment.

PMIP4

Paleoclimate Modeling Intercomparison Project Phase 4 (PMIP4) is one of the CMIP-endorsed project, aiming to analyze paleoclimate data, mainly including the past 1000 years, the past 2000 years, the middle Holocene, the LGM, the middle Pliocene, and the Last Interglacial (~127 thousand years ago, labeled as Lig127k). We use 39 experiments of 14 models (4 for LGM, 12 for Lig127k, 14 for Middle Holocene, 4 for Middle Pliocene, and 5 for past 1000 or 2000 years). The corresponding piControl experiments in CMIP6 are also used to calculate zonal-mean surface temperature differences as shown in Fig. 2b.

Other modeling data

Community Earth System Model (CESM) is a fully coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). In ref. 30, a group of slice experiments from 540 Ma to PI are designed, with time intervals of 10 million years and horizontal resolution of 3.75° × 3.75°. Solar constant, paleogeography, and CO2 concentration are chosen as boundary conditions30,57,58. Dynamic vegetation is used in all the experiments. All of the three factors vary with time (Group 1). In the other two groups, CO2 concentration is fixed to 2800 ppmv (Group 2) and CO2 concentration is fixed to 2800 ppmv and meanwhile solar constant is fixed to 1361 W m−2 (Group 3)33,36.

Reference 27 conducted several CESM experiments focusing on the PETM using CESM. They tested four different CO2 concentrations (280, 840, 1680, and 2520 ppmv) and altered cloud microphysical processes. The horizonal resolution they used is 2.5° × 1.9° in longitude-latitude. Reference 32 designed the CESM experiments of ~95, 55, and 14 Ma using different CO2 concentrations and vegetation types. They used the same resolution as ref. 27.

Reference 29 used a specific version of the Hadley Centre Model, HadCM359 with the horizontal resolution of 3.75° × 2.5° in longitude-latitude. They conducted two groups of 109 climate model simulations covering the entire Phanerozoic. In the first group, the CO2 concentrations are the best-fit local regression curve from ref. 60. This group of experiments is labeled as “Group 1” in Fig. 1. In Group 2, they selected the CO2 values that were influenced by some non-public paleogeographic reconstructions and best matched the terrestrial proxy data. The CO2 curve in the second group is a heavily smoothed version of the Foster curve. In their experiments, both solar constant and paleogeography vary with time57,58.

Sensitivity experiments

Several sensitivity experiments using the atmospheric component of CESM are designed to further verify our conclusions. All the experiments are coupled to a well-mixed ocean rather than a dynamical ocean. Sea surface temperature is calculated based on the prescribed mixed layer depth and surface energy fluxes61. The prescribed surface energy fluxes can vary seasonally, but not interannually, and act as meridional ocean heat transport equivalently. We design four groups of slab-ocean sensitivity experiments based on the PI experiment in ref. 30. The horizontal resolution of the sensitivity experiments is 3.75° × 3.75°. All the slab-ocean experiments are run for at least 100 model years, and the last 50-year averages are used for analyses.

In the first group, the latitudinal distribution of incoming solar radiation is tested. We keep the solar constant unchanged, which is 1361 W m−2. To change the latitudinal distribution of the incoming solar radiation, we employ two different obliquities, 0° and 40°, and compare with the default obliquity, 23.3°. When the obliquity is larger, there is more annual-mean shortwave radiation reaching the polar regions and meanwhile the tropics has less shortwave radiation (Fig. 4a). It should be noticed that in this group of experiments, we apply a hypothetical aquaplanet, whose surface is entirely covered by water with no landmasses, in order to exclude the hemispherical asymmetry caused by continents. The horizontal resolution is changed to 2.5° × 1.9° in longitude-latitude. The surface energy flux is set to be zero, and the ocean mixed layer depth is set to 50 m everywhere. Moreover, to avoid the planet turning into a snowball Earth state, we increase the CO2 concentration to 1120 ppmv (i.e., 4 times of the value in the PI experiment). We also run an experiment in which the CO2 concentration is 2240 ppmv and the obliquity is 23.3° to test the changes of TMSTG. The results are shown in Fig. 4a, b.

In the second group, different surface energy fluxes are examined. We set the surface energy flux to respectively 100%, 40%, and 0% (i.e., no ocean heat of the value in the fully coupled PI experiment, in order to explore whether the different energy fluxes can affect the tropical meridional surface temperature gradient. Other external forcings, including CO2 concentration (280 ppmv), solar constant (1361 W m−2), land-sea distribution, and ocean mixed layer depth, are set to be consistent with the fully coupled PI experiment. The horizontal resolution is also the same as the fully coupled PI experiment. The results are shown in Fig. 4c.

In the third group of slab-ocean sensitivity experiments, we examine the effect of clouds by turning on or turning off cloud radiative effects. Other forcings, including CO2 concentration, solar constant, ocean mixed layer depth, and surface energy flux are set to be the same as that in the fully coupled PI experiment. The results are shown in Fig. 4d.

Different rotation rates are tested in the fourth group of experiments. Denoting the present rate as Ωe, three different rotation rates of 4Ωe, 1Ωe, and Ωe/10 are chosen. In this group, the surface energy flux is also set to be zero. By default, the CO2 concentration is set to be 280 ppmv. We also run an additional experiment in which the CO2 concentration is 1120 ppmv and the rotation rate is Ωe/10 to test the changes of TMSTG. The results are shown in Fig. 4e, f.

Parallel offline radiative transfer (PORT) tool

The Parallel Offline Radiative Transfer (PORT) tool is a tool for conducting radiation transfer calculations62. As a part of CESM, it facilitates radiation computation in isolation, enabling the calculation of radiative fluxes without climate feedbacks. In this study, we take 10 Ma as an example and utilize the PORT to compare changes in radiative forcing resulting from variations in CO2 concentration (2800 ppmv versus 728 ppmv), lapse rate feedback, temperature feedback, and water vapor feedback. The results are shown in Fig. S6.

Data availability

The data of sensitivity experiments generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2682814363. The simulation data of the past 540 million years in ref. 31 are archived in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19920662.v1. The CMIP6 data can be found in https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/?project=CMIP6/. The NCEP reanalysis data can be found in https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/reanalysis/. The simulation output in refs. 28, 32 can be found in https://doi.org/10.1029/2021PA004383 and https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax1874. The assimilation data in refs. 29,56,57 can be found in https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03984-4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2617-x, and https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2205326119.

Code availability

All figures were created using NCL (NCAR Command Language), and the code can be obtained at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14835818.

References

Rind, D. Latitudinal temperature gradients and climate change. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 5943–5971 (1998).

Karamperidou, C., Cioffi, F. & Lall, U. Surface temperature gradients as diagnostic indicators of midlatitude circulation dynamics. J. Clim. 25, 4154–4171 (2012).

Hassanzadeh, P., Kuang, Z. & Farrell, B. F. Responses of midlatitude blocks and wave amplitude to changes in the meridional temperature gradient in an idealized dry GCM. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5223–5232 (2014).

Hartmann, D. L. Global Physical Climatology (Elsevier Science, 2016).

Coppin, D. & Bony, S. On the interplay between convective aggregation, surface temperature gradients, and climate sensitivity. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 10, 3123–3138 (2018).

Rantanen, M., Räisänen, J., Sinclair, V. A. & Järvinen, H. Sensitivity of idealised baroclinic waves to mean atmospheric temperature and meridional temperature gradient changes. Clim. Dyn. 52, 2703–2719 (2019).

Ballantyne, A. P. et al. Significantly warmer Arctic surface temperatures during the Pliocene indicated by multiple independent proxies. Geology 38, 603–606 (2010).

Zhang, L., Hay, W. W., Wang, C. & Gu, X. The evolution of latitudinal temperature gradients from the latest Cretaceous through the present. Earth Sci. Rev. 189, 147–158 (2019).

Gaskell, D. E. et al. The latitudinal temperature gradient and its climate dependence as inferred from foraminiferal δ18O over the past 95 million years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111332119 (2022).

Manabe, S. & Wetherald, R. T. The effects of doubling the CO2 concentration on the climate of a general circulation model. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 3–15 (1975).

Holland, M. M. & Bitz, C. M. Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models. Clim. Dyn. 21, 221–232 (2003).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Nat. Geosci. 7, 181–184 (2014).

Taylor, P. C. et al. Process drivers, inter-model spread, and the path forward: a review of amplified Arctic warming. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 758361 (2022).

Bintanja, R., Graversen, R. G. & Hazeleger, W. Arctic winter warming amplified by the thermal inversion and consequent low infrared cooling to space. Nat. Geosci. 4, 758–761 (2011).

Singh, H., Feldl, N., Kay, J. E. & Morrison, A. L. Climate sensitivity is sensitive to changes in ocean heat transport. J. Clim. 35, 2653–2674 (2022).

Jones, G. S., Stott, P. A. & Christidis, N. Attribution of observed historical near-surface temperature variations to anthropogenic and natural causes using CMIP5 simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 4001–4024 (2013).

Casagrande, F., Buss de Souza, R., Nobre, P. & Lanfer Marquez, A. An inter-hemispheric seasonal comparison of polar amplification using radiative forcing of a quadrupling CO2 experiment. Ann. Geophys. 38, 1123–1138 (2020).

Hill, S. A., Burls, N. J., Fedorov, A. & Merlis, T. M. Symmetric and antisymmetric components of polar-amplified warming. J. Clim. 35, 6757–6772 (2022).

Chung, E.-S. et al. Cold-season Arctic amplification driven by Arctic ocean-mediated seasonal energy transfer. Earth’s Future 9, e2020EF001898 (2021).

Holland, M. M. & Landrum, L. The emergence and transient nature of Arctic amplification in coupled climate models. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 719024 (2021).

Xie, A. et al. Polar amplification comparison among Earth’s three poles under different socioeconomic scenarios from CMIP6 surface air temperature. Sci. Rep. 12, 16548 (2022).

Joshi, M. M., Gregory, J. M., Webb, M. J., Sexton, D. M. H. & Johns, T. C. Mechanisms for the land/sea warming contrast exhibited by simulations of climate change. Clim. Dyn. 30, 455–465 (2008).

Fedorov, A. V. et al. Patterns and mechanisms of early Pliocene warmth. Nature 496, 43–49 (2013).

Fedorov, A. V., Burls, N. J., Lawrence, K. T. & Peterson, L. C. Tightly linked zonal and meridional sea surface temperature gradients over the past five million years. Nat. Geosci. 8, 975–980 (2015).

Seager, R. et al. Strengthening tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient consistent with rising greenhouse gases. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 517–522 (2019).

Zhu, J., Poulsen, C. J. & Tierney, J. E. Simulation of Eocene extreme warmth and high climate sensitivity through cloud feedbacks. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1874 (2019).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Glacial cooling and climate sensitivity revisited. Nature 584, 569–573 (2020).

Valdes, P. J., Scotese, C. R. & Lunt, D. J. Deep ocean temperatures through time. Clim 17, 1483–1506 (2021).

Li, X. et al. A high-resolution climate simulation dataset for the past 540 million years. Sci. Data 9, 16548 (2022).

Lunt, D. J. et al. Palaeogeographic controls on climate and proxy interpretation. Climate 12, 1181–1198 (2016).

Acosta, R. P., Ladant, J. B., Zhu, J. & Poulsen, C. J. Evolution of the Atlantic intertropical convergence zone, and the South American and African monsoons over the past 95-Myr and their impact on the tropical rainforests. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 37, e2021PA004383 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Climate variations in the past 250 million years and contributing factors. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 38, e2022PA004503 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Emergence of the modern global monsoon from the Pangaea megamonsoon set by palaeogeography. Nat. Geosci. 16, 1041–1046 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. The Hadley circulation in the Pangea era. Sci. Bull. 68, 1060–1068 (2023).

Yuan, S. et al. Controlling factors for the global meridional overturning circulation: a lesson from the Paleozoic. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm7813 (2023).

Charney, J. G. A note on large-scale motions in the tropics. J. Atmos. Sci. 20, 607–609 (1963).

Pierrehumbert, R. T. Thermostats, radiator fins, and the local runaway greenhouse. J. Atmos. Sci. 52, 1784–1806 (1995).

Sobel, A. H. & Bretherton, C. S. Modeling tropical precipitation in a single column. J. Clim. 13, 4378–4392 (2000).

Vallis, G. K. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Byrne, M. P. et al. Theory and the future of land-climate science. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1079–1086 (2024).

Colman, R. A comparison of climate feedbacks in general circulation models. Clim. Dyn. 20, 865–873 (2003).

Yoshimori, M., Yokohata, T. & Abe-Ouchi, A. A comparison of climate feedback strength between CO2 doubling and LGM experiments. J. Clim. 22, 3374–3395 (2009).

Merlis, T. M. Direct weakening of tropical circulations from masked CO2 radiative forcing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13167–13171 (2015).

Wei, M. et al. Simulated warming hole in paleo-Pacific oceans. J. Clim. 37, 3359–3376 (2024).

Held, I. M. & Hou, A. Y. Nonlinear axially symmetric circulations in a nearly inviscid atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 37, 515–533 (1980).

Donohoe, A. & Battisti, D. S. Atmospheric and surface contributions to planetary albedo. J. Clim. 24, 4402–4418 (2011).

North, G. R. Theory of energy-balance climate models. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 2033–2043 (1975).

Yang, D., Zhou, W. & Seidel, S. D. Substantial influence of vapor buoyancy on tropospheric air temperature and subtropical cloud. Nat. Geosci. 15, 781–788 (2022).

Yang, D. & Seidel, S. D. The incredible lightness of water vapor. J. Clim. 33, 2841–2851 (2020).

Seidel, S. D. & Yang, D. The lightness of water vapor helps to stabilize tropical climate. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1951 (2020).

Wheeler, M. & Kiladis, G. N. Convectively coupled equatorial waves: analysis of clouds and temperature in the wavebumber-frequency domain. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 374–399 (1999).

Perez-Becker, D. & Showman, A. P. Atmospheric heat redistribution on hot Jupiters. Astrophys. J. 776, 134 (2013).

Komacek, T. D. & Showman, A. P. Atmospheric circulation of hot Jupiters: dayside–nightside temperature differences. Astrophys. J. 821, 16 (2016).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Spatial patterns of climate change across the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205326119 (2022).

Osman, M. B. et al. Globally resolved surface temperatures since the last glacial maximum. Nature 599, 239–244 (2021).

Gough, D. O. Solar interior structure and luminosity variations. Phys. Sol. Var. 74, 21–34 (1981).

Scotese, C. R. & Wright, N. M. PALEOMAP paleodigital elevation models (PaleoDEMS) for the Phanerozoic. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/records/5460860 (2018).

Valdes, P. J. et al. The BRIDGE HadCM3 family of climate models: Hadcm3@bristol v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 3715–3743 (2017).

Foster, G. L., Royer, D. L. & Lunt, D. J. Future climate forcing potentially without precedent in the last 420 million years. Nat. Commun. 8, 14845 (2017).

Kiehl, J. T., Shields, C. A., Hack, J. J. & Collins, W. D. The climate sensitivity of the community climate system model version 3 (CCSM3). J. Clim. 19, 2584–2596 (2006).

Conley, A. J., Lamarque, J. F., Vitt, F., Collins, W. D. & Kiehl, J. PORT, a CESM tool for the diagnosis of radiative forcing. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 469–476 (2013).

Wei, M., Yang, J., Hu, Y., Kaspi, Y. & Nie, J. Quasi-invariance of Tropical Meridional Surface Temperature Gradient in a Wide Range of Climates. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26828143 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful discussions with Feng Ding, Yonggang Liu, and Yi Zhang and for the numerical simulations or technical support from Mingyu Yan, Xiang Li, Jiaqi Guo, Jiawenjing Lan, Qifan Lin, Xiujuan Bao, Shuai Yuan, Zhibo Li, Kai Man, Zihan Yin, Jing Han, and Jian Zhang. This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grants 42488201 and National Key Research and Development Program of China Grants 2024YFF0807903. The simulations were performed at the High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. and Y.H. led and designed the research. M.W. performed the simulations and analyzed the data. M.W., J.Y., Y.K., Y.H. and J.N. did the mechanism analyses. J.Y. and M.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the analyses of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Vishal Dixit and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, M., Yang, J., Hu, Y. et al. Quasi-invariance of tropical meridional surface temperature gradient in a wide range of climates. Nat Commun 17, 123 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66811-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66811-8