Abstract

Achieving a significant reduction in the cost of proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) is an imminent goal, and decreasing the overall platinum loading in the membrane electrode assembly (MEA) is regarded as a critical means to achieve this objective. However, as the Pt loading decreases, the MEA performance drops sharply, which is mainly impeded by the mass transport resistance at the triple phase boundaries (TPBs) for O2 and H+ to reach the catalyst active site through the ionomer. In this research, we propose an effective strategy to achieve precise control of the three-phase microenvironment within catalyst layer by introducing thiophene sulfur (C-S-C) species onto the surface of the carbon support. FIB/slice-STEM EDX mapping (STEM-EDX mapping of focused ion beam-processed and microtome-sliced samples) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation clearly demonstrate that the interaction between thiophene sulfur and the sulfonic group on the ionomer’s side chains enhances the uniformity of the ionomer distribution, thereby promoting the formation of ideal TPBs. Consequently, the local oxygen transport resistance in the catalytic layer is reduced from 0.236 s cm−1 to 0.047 s cm−1. This improvement achieves a high rated power density of 1.06 W cm−2@0.67 V and a Pt utilization efficiency of 8.47 W mgPGM−1, with Pt loading as low as 0.125 mgPt cm−2. These findings exceed the technology targets set by the United States Department of Energy (DOE).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs), as a mobile and portable hydrogen energy conversion device, are mainly used in automotive applications, offering great potential for a sustainable economy in the future1,2,3. However, the widespread adoption of fuel cell technology still remains impeded. In addition to the lack of hydrogen infrastructure, the main obstacle to its development remains the cost of PEMFC systems, with platinum group metal (PGM) catalysts accounting for 42% of the total cost4,5. If the cost of PGM catalysts remains at current level, their proportion of total system costs will increase with production scale-up. The current Pt usage is 22.5 g Pt per 90 kw stack, which is still far from the ultimate utilization target of 5 g platinum6. Further reduction of platinum use is the key to widespread commercialization of PEMFC.

In the actual PEMFC, oxygen reduction reaction occurs at the catalyst-ionomer-gas triple phase boundaries (TPBs). The catalyst, as a crucial component, can significantly enhance fuel cell performance through precisely engineered design and structural optimization to improve intrinsic ORR activity. For instance, CoOx@Pt/C catalyst that consists of Pt nanoparticles with sparsely embedded cobalt oxide (CoOx) clusters7 and Pt@Gnp/KB, an ultrafine pure Pt catalyst protected by graphene nanopockets and supported on Ketjenblack carbon8, demonstrate high performance in single-cell tests and have broken through DOE Target of 8 W mgPGM−1 Pt utilization in MEA. However, the process of oxygen and protons required for the reaction reaching the active site through the ionomer remains equally critical. The reduction in PGM loading of MEA leads to a reduction in the number of catalytic sites, which will require simultaneously increasing the intrinsic ORR activity of the catalyst and the rate of reactant delivery to each active site6,9. Therefore, it is crucial to build ideal TPBs, which means enhancing the ORR activity of the catalyst, and more importantly, promoting oxygen transport, as well as ensuring the proton accessibility of the catalyst sites, and finally, to maximize the performance of fuel cell.

On the one hand, catalyst nanoparticles, which are typical solid phases at TPBs, were constructed as the interfacial structure of metal nanoparticles/ionomer10,11. In this interface, due to the strong adsorption of the -SO3H of nafion with Pt12, the poisoning effect of the sulfonic acid group drastically reduces the activity of Pt. What’s more, the ionomer tends to aggregate around the nanoparticles, potentially generating an markedly high resistance of oxygen transport13,14. Several methods have been used to improve the distribution of the ionomer in the interface in order to solve these problems15. Carbon layers on the surface of the catalyst particles act as protective “armor” to mitigate the excessive contact between the ionomer and the metal particles16,17. It is also possible to add cyclohexanol to the slurry to coordinate with the ionomer, or develop covalent organic framework (COF) nanosheet ionomer18,19, which inhibits the dense laminar folding of the ionomer backbone near the Pt surface20. The uniform distribution of ionomer in the catalyst layer can reduce the oxygen transport resistance and enhance the proton transport capacity in the TPBs, thus the ideal triple phase boundaries can be obtained by regulating the distribution of ionomer21,22,23,24.

On the other hand, in fact, the catalyst generally consists of high surface-area carbon-supported nanoparticles such as Pt. Of course, there are also carbon/ionomer interfaces, so the influence of structure and properties of carbon support surface on the distribution of the ionomer should not be ignored11. Yarlagadda et al.25 have been proposed porous carbons with a preferred pore opening of 4−7 nm can give catalysts with both high ORR activities and transport properties. This approach of restricting ionomer access to the platinum surface at the molecular scale by screening the carbon carrier’s pore size enabled a fuel cell performance with a Pt utilization exceeding the DOE Target of 8 W mgPGM−1. This result represents a significant step toward a sustainable Pt usage level for transportation. Recently, nitrogen doping of carbon support has been demonstrated to be a feasible strategy to obtain a more homogeneous ionomer distribution26,27,28,29. This is attributed to Coulombic attraction between the N functional groups (e.g., −NHX) on the carbon support and the sulfonic acid groups (SO3−) of the ionomer, which facilitates a more uniform dispersion of the ionomer. The in-depth investigations of the different nitrogen doping methods and conditions reveal that the modulation of the ionomer distribution by functional groups on the carbon carrier surface is affected by combination of the type of nitrogen precursor, the mixing ratio, and the annealing temperature28,29,30. In addition to the mainstream N doping, the oxygen content on the carbon support surface also affects the homogeneity of the ionomer distribution due to the noncovalent interaction31,32, which in turn affects the performance of PEMFC.

Obviously, the method of modifying carbon support to regulate ionomer has gradually attracted attention, but the related studies are relatively limited at present, and there is a lack of more designs of carbon modification to regulate the distribution of ionomer, especially the regulation of the functional groups to balance between ionomer-alloy nanoparticles and ionomer-carbon, finally to obtain the homogeneous ionomer distribution. More importantly, there is a paucity of direct evidence of the ionomer distribution and in-depth analysis of the interaction mechanism in this field.

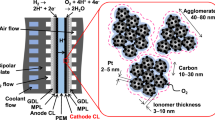

Here, we propose a strategy to create the triple phase boundaries with high activity and low oxygen mass transfer resistance by regulating the distribution of ionomer in the catalyst layer through S-modified carbon support. Our method entails incorporating thiophene S (C-S-C) onto the carbon support and prepares Pt3Co alloy supported catalyst (Pt3Co/S-KB) (Fig. 1). This approach aims to enhance the intrinsic activity of the catalyst, and more importantly, achieve a spatially uniform distribution of the ionomer (as directly evidenced by FIB/ slice-STEM), reducing the resistance to mass transport of oxygen while ensuring proton transport, which directly contributes to the observed high power density in fuel cells at low Pt loading. Furthermore, the interaction between thiophene S on the carbon support and the side chain sulfonic acid groups of the ionomer was elucidated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analysis. The proposed S-modified carbon support broadens the research direction of carbon carrier surface modification, affecting the ionomer distribution, provides guidance for the micro-regulation of the ideal TPBs of the catalyst layer, and contributes to further cost reduction for large-scale commercialization of PEMFC.

Top Panel: The synthesis process of Pt-Co alloy catalyst supported by small molecule-assisted impregnation method directly on the traditional carbon support EC300 (Grey arrow) and on the modified S-KB (Blue arrow). The main difference is that S-KB modified thiophene S; Bottom Panel: The difference of ionomer distribution and mass transport in the catalyst layers of Pt3Co/S-KB (lower left) and Pt3Co/KB (lower right). The ionomer in the catalyst layer of Pt3Co/S-KB is evenly distributed, which increases the effective coverage of the ionomer, improves the proton conductivity, and reduces the oxygen transport resistance. It improves the uneven distribution of ionomer in the Pt3Co/KB catalyst layer, alleviates the high oxygen transport caused by the accumulation of ionomer around some catalyst particles, and the poor H+ accessibility caused by the absence of ionomer around some catalyst particles.

Results

Carbon support and catalyst characterization

First, the S-containing precursor sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine and the pristine Ketjenblack (KB-EC300JD) were mixed in a mixed solvent (Vwater: Vethanol = 1: 1). The feeding ratios varied (mass ratios of sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine: pristine Ketjenblack (KB-EC300JD) = 1:3, 1:2 and 1:1) in order to modulate the amount of S-containing functional groups on the surface of the carbon carriers (Table S1). The mixture was pyrolyzed at 900 °C for 2 h to synthesize the S-functionalized carbon support (denoted as S-KB; see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information for details). For comparison, pristine Ketjenblack (KB-EC300JD) without S-modification was used as the control sample throughout this work. Subsequently, a small molecule-assisted impregnation method was used to realize small-sized Pt3Co alloy catalysts burdened on carbon supports (Fig. 1). Metal precursors (i.e. H2PtCl6 and (CH3COO)2Co) and S-containing molecule additives (to avoid additional elements) were wet-impregnated onto corresponding carbon support with a total metal loading of 20 wt% (Table S3). And in the high-temperature H2-annealing synthesis, the S-containing small molecules (C3H8S) significantly inhibited the sintering of metal particles, guaranteeing the formation of small- sized intermetallic compounds nanoparticle catalysts as confirmed by the subsequent Figs. 2e and S7.

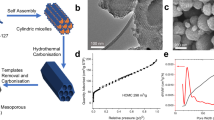

a XRD patterns of KB and S-KB. b HAADF-STEM images, and the corresponding EDS elemental mappings of C and S in S-KB. c High-resolution deconvoluted XPS spectra of S2p for KB and S-KB. d XRD patterns of Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB. e TEM image of Pt3Co/S-KB. Inset: histogram of particle size statistics. f EDS electronic mappings of Pt, Co, and S of representative Pt3Co/S-KB.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments conducted on the comparison sample KB and S-KB, which represents the S-functionalized carbon support (Fig. 2a), demonstrated that the two samples exhibited almost identical peaks of pure C (PDF #97-067-1182). Combined with N2 adsorption-desorption results (Fig. S11 and Table S10), the similar specific surface area and pore size distribution before and after S modification indicated that the modification of S did not change the fundamental physical phase and crystal structure of the carbon support33,34. However, the elemental distribution of S-KB (Fig. 2b) was distinctly different from that of KB (Fig. S1), with the S signal in S-KB being clearly visible and essentially coinciding with the distribution of C signal, unlike the nearly undetectable S signal in KB. Elemental analysis revealed that the S content of S-KB was within the range of 1.2–1.65 at % (Table S2). On the surface of S-KB, two types of S groups were identified, thiophene S (C-S-C) and oxidized S (S-Ox) (Fig. 2c) (In contrast, the S 2p spectrum of KB showed no signal)35,36,37. Both of these S species were present in the S-modified carbon carriers with different feeding ratios, and the percentage of thiophene S increased with the increase of S-containing precursors (Figs. S2, S3 and Table S4). In contrast, the contribution of oxidized S was very small (Figs. S2 and S3). Therefore, it can be assumed that the species of thiophene S (C-S-C) was mainly introduced onto the carbon support.

Subsequently, the physical and chemical properties of the catalysts supported on these carriers were studied. The composition of synthesized samples was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Table S3). In Figs. 2d and S5, the diffraction peaks of the (111) and (200) crystal faces of the catalyst shifted to a higher angle compared with pure Pt (PDF # 006-4924), representing the incorporation of Co, which reducing the interplanar spacing. Combined with ICP-OES results, the molar ratio of Pt and Co was determined to be 3:1, indicating that the alloy catalysts were Pt3Co.Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Figs. 2e, f and S6) showed that the Pt3Co catalysts were effectively dispersed on the S-modified carbon support (S-KB) with an average particle size of 2.1 ± 0.4 nm. The catalyst particle size and distribution of Pt/C and Pt3Co/KB were very similar to that of Pt3Co/S-KB (Figs. S4, S7 and S8). It is worth noting that the loading of Pt3Co alloy did not affect the existence and properties of thiophene S on the surface of the catalyst support (Figs. S9 and S10), and its content increased with the increase of the feed ratio (0.713 at % (Pt3Co/S-KB 1:3) < 1.030 at % (Pt3Co/S-KB 1:2) < 1.344 at %(Pt3Co/S-KB 1:1)), which is controllable (Table S5). Of course, Pt3Co/KB also detected the presence of S species, but mainly oxidized S (S-Ox) (Fig. S9), which was due to the addition of small molecule S during the catalyst loading process. Otherwise, the alloy catalyst particles may be severely sintered at high temperatures (highly uneven particle distribution and wide particle size distribution shown in the XRD calculated results in Fig. S12 and TEM images in Fig. S15), and the ORR performance was also significantly deteriorated (Figs. S13, S14 and Table S6), which are consistent with reported results of catalyst synthesis35,38,39.

ORR activity and fuel cell performance

In the half-cell test, the performance of Pt3Co catalysts before and after the introduction of thiophene S was similar, indicating that this modification of the carbon support did not significantly affect the intrinsic ORR activity of the catalysts (Figs. S16–S19). Similar catalyst particle sizes (Figs. 2e and S7) and Pt 4f XPS results (Fig. S20) supported this conclusion. However, all Pt3Co catalysts exhibited markedly higher ORR activity than commercial Pt/C (all Pt3Co catalysts’ MAs were more than 1 A mgPt−1 for comparison, Pt/C had the value of 0.247 A mgPt−1) (Figs. S18 and S19). As revealed by the XPS spectra (Fig. S20), the Pt 4 f peaks in all Pt3Co catalysts exhibit a positive shift in binding energy relative to Pt/C. This observation indicates the existence of modified electronic effect, which is known to optimize the ORR activity by weakening the binding of ORR intermediates and Pt40,41,42. Considering that the improvement of the actual MEA’s performance needs highly active catalyst and the efficient construction of the triple phase boundary of catalytic layer at the same time, the Pt3Co catalyst with high ORR activity was designed and synthesized, which laid the foundation for the subsequent improvement of MEA’s performance.

Further, to confirm the feasibility of the proposed triple phase boundaries modulation strategy for promoting the homogeneous distribution of the ionomer through the introduction of thiophene S, the MEA was prepared by a catalyst-coated membrane (CCM) approach. In all the prepared MEAs, the Pt loading of the cathode and anode was fixed at 0.10 and 0.025 mgPGM cm−2 (Table S7), respectively. For fair comparison, the anode catalysts were all made with commercial Pt/C, and all the materials used in the preparation of the MEAs were identical, in addition to the cathode catalyst. Obviously, the polarization curves of Pt3Co/KB without S-modification of the carbon support have largely coincided with those of the comparison sample Pt/C. After the introduction of thiophene S, the performance of Pt3Co/S-KB has significantly improved, and the enhancement is particularly pronounced in the high current density region. It is noteworthy that the performance improvement of Pt3Co/S-KB with different thiophene S content was different. Among them, the highest measurable power density has reached 1.7 W cm−2 for Pt3Co/S-KB 1:2 (Figs. 3a and S22) (Pt3Co/S-KB in the subsequent text refers to Pt3Co/S-KB 1:2). Calculation of specific rated power at 0.67 V, which is the cell voltage for the heat rejection limit in light duty vehicles43, is indispensable for evaluating the intrinsic activity and Pt utilization (normalizing the power by the total PGM loading) efficiency from a practical perspective of PEMFCs. The H2/air fuel cell employing the Pt3Co/S-KB catalyst achieved a rated power density of 1.06 W cm−2, outperforming those with Pt/C (0.424 W cm−2) and Pt3Co/KB (0.525 W cm−2) (Fig. 3b), and surpassing the DOE target of 1.00 W cm−2 4,44. Furthermore, the Pt3Co/S-KB MEA exhibited a high Pt utilization of 8.47 W mgPGM−1 (Fig. 3b), outperforming the DOE target (8.0 W mgPGM−1). These power performances of Pt3Co/S-KB are competitive with the top reported performances for Pt-based catalysts (Table S8), and it is currently one of the most promising catalysts in terms of reducing the cost of fuel cells by lowering the Pt content.

a H2-air fuel cell polarization curves of Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB. Anode: 0.025 mgPt cm−2 of Pt/C; cathode:0.1 mgPt cm−2 of catalysts; temperature:94 °C; 100% relative humidity (RH); backpressure:150 kPaabs; Electrode active area: 25 cm2. b Comparison of the rated power density (@0.67 V) and Pt utilization (rated power of MEAs normalized by the total PGM loading) obtained in H2/air tests. DOE targets are indicated by the blue dashed and dotted lines. In order to verify the repeatability of the data, we conducted 3 tests and presented them in the form of averages ± standard deviation. c DRT plots of Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB at 1 A/cm2. d Total O2 mass transport resistance measured for Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB catalyst MEAs over the respective pressure in O2 concentration of 1%, whereas the regression line enables separation between \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) and \({R}_{o2}^{P,{dep}}\). e Nyquist plots of EIS spectra under H2/N2. Lower right corner: The proton transfer impedance values of each sample obtained by fitting and calculating. f ECSA of the Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB, and Pt3Co/S-KB catalyst MEAs at 30% and 100% relative humidity (RH), and the difference between them. g–i Polarization curves of H2-air fuel cell with Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB, and Pt3Co/S-KB as the cathode at 30% and 100% relative humidity (RH). j voltage loss of different catalyst MEAs from 100 % RH to 30 % RH at 1 A cm−2.

In order to analyze the underlying causes of the significant differences in the performance of MEAs before and after the S modification of carbon support, we carried out electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests45. Subsequently, to deeply explore the polarization process of each catalyst in fuel cells, representative peaks were precisely decoupled using the distribution of relaxation time (DRT) technology (Fig. S23)46. It is clear that in the low current density region (Fig. S23a, b), whether it is Pt/C, Pt3Co/KB, or Pt3Co/S-KB, the main representative charge transfer resistance in EIS (representing the kinetics of electrode reaction) or cathode charge transfer impedance of the P2 peaks in DRT shows minimal variation. This is evidence that the intrinsic activity of catalyst has limited influence on the performance of full cell. In contrast, significant differences emerge in the high current density regions (Figs. S23c, d and 3c). The oxygen mass transfer impedance (evident in the low-frequency region of EIS spectra and corresponding to P1 peaks in DRT analysis) demonstrates a pronounced reduction for Pt3Co/S-KB—approximately half lower than Pt3Co/KB and substantially lower than Pt/C. Notably, the observed difference in the P2 peaks (representing the cathode charge transfer impedance) here is mainly due to the reverse influence of the substantial difference in the oxygen transfer impedance represented by the P1 peaks45,46. The decreased magnitude of EIS-DRTs for Pt3Co/S-KB with different feed ratios was different, but the trend of improving the mass transfer process was consistent (Fig. S24). All these findings prove that the significant improvement of the MEA performance is not only attributed to the improvement of the intrinsic activity of the catalyst, but also because the introduction of thiophene S on the carbon support improves the oxygen mass transfer process at the TPBs.

To quantify the oxygen mass transfer resistance (Rtotal), we performed limiting current measurements at 1 mol% O2 concentration and several total pressure (110-250 kPa) (Figs. S25, S26 and 3d)47,48,49. The oxygen mass transport resistance (Rtotal) is typically described by a model comprising two distinct elements. These are: (i) a pressure-dependent resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{dep}}\)), attributed mainly to the molecular diffusion of oxygen; and (ii) a pressure-independent resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\)), which encompasses the cumulative contributions from Knudsen diffusion and the transport of O2 through the ionomer film covering the catalyst particles50,51. In detail, by varying the total pressure, the fitted Rtotal curve produces an intersection with the vertical coordinate, the intercept distance of which is the pressure-independent oxygen transport resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\)), while the product of the slope of the fitted curve and the gas pressure is the pressure-dependent oxygen transport resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{dep}}\)). Since the same flow field structure and gas diffusion layer (GDL) were used for all MEA measurements, any differences observed were attributed to variations in the catalyst layer, while the contribution of the diffusion medium and microporous layer remained constant. The comparable SEM images of the catalyst layer surfaces (Fig. S29) and mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) results (Fig. S31) for both Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB demonstrated that the introduction of thiophene S did not significantly affect either the large-scale micromorphology (micron-scale) or pore size distribution of the catalyst layer. Moreover, it has been emphasized in the literature that the main problem with low platinum loading cathodes is the abnormally high proportion of pressure-independent transport resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\))6,50,52,53,54. The intercept data of the fitted curves in Fig. 3d (the “b” in the equation \(y={kx}+b\) obtained from the fitting of the curve) clearly shows that the MEA prepared from S-modified Pt3Co/S-KB exhibits significantly lower \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) (0.047 s cm−1). While the data of Pt3Co/KB and Pt/C are 0.236 s cm−1 and 0.214 s cm−1, which are 5 times and 4.55 times higher than that of Pt3Co/S-KB. It is noted that with the increase of thiophene S content, the \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) decreased first and then increased (Figs. S26 and S27), which was consistent with the corresponding MEA’s performance (Figs. S21 and S22) and EIS-DRT results (Figs. S23 and S24), indicating that the regulation of thiophene S content is also crucial. Of course, the \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) of all Pt3Co/S-KBs were significantly lower than that of Pt3Co/KB before thiophene S modification. What’s more, considering that presenting I–V curves measured under low oxygen partial pressure conditions offers the most direct and compelling evidence to illustrate differences in oxygen transport resistance, polarization curves have been tested under reduced oxygen concentration (10% O) for all three catalyst-based MEAs. The results (Fig. S28) clearly demonstrated that the MEA with Pt3Co/S-KB catalyst still maintained robust performance with cathode gas feed of low oxygen (10% O2). We propose that the introduction of thiophene S may lead to more uniform ionomer distribution and cover the catalyst surface with a thinner layer of ionomer, which could reduce \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\), and ultimately lead to a significant increase in the MEA performance.

When the ionomer is not uniformly distributed on the catalyst surface, on the one hand, it will cause an increase in the resistance to O2 transport in the thicker regions of the ionomer, on the other hand, in the regions where the ionomer layer is thin or discontinuous, it is also unfavorable to H3O+ transport6,9,55. Firstly, the lower value of the proton transfer impedance (Fig. 3e) for the Pt3Co/S-KB (7.08mΩ) compared to that for Pt3Co/KB (9.32 mΩ) and Pt/C (8.46 mΩ) suggested that the introduction of thiophene S can improve the proton transport process in the catalyst layer, which may be an indirect evidence for the more uniform distribution of ionomer in the MEA prepared by Pt3Co/S-KB. What’s more, we tested the CV curves of the full cells to obtain the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) at 30% RH and 100% RH, respectively (Fig. 3f), and then calculated to obtain the dry proton accessibility (\(\frac{{{\mathrm{ECSA}}}_{30\%{RH}}}{{{\mathrm{ECSA}}}_{100\%{RH}}}\) 28,50,51) (Table S9). The proton accessibility is in the order of Pt3Co/S-KB (93%) > Pt3Co/KB (82%) > Pt/C (73%). Proton accessibility indicates the proximity of the ionomer to the Pt nanoparticles, which is usually influenced by the coverage of the ionomer and the position of the nanoparticles26,48,51. Such high dry proton accessibility of Pt3Co/S-KB supports the high ionomer coverage on the surface. This observation offers corroborating evidence for enhanced ionomer distribution homogeneity. Figure 3g–j shows the effect of decreasing the relative humidity (100%RH to 30%RH) on the performance of different MEAs, and the weak dependence on relative humidity is reflected by the significant decrease in the Pt3Co/S-KB dropping. Excluding the effect of sulfur modification on carbon support surface wettability (Fig. S32), this has important practical significance in the context of commercialization of PEMFC, as high dry proton accessibility reduces humidification requirement and therefore greatly reduces overall stack costs56. We also explored the stability of the Pt3Co/S-KB with constant-potential testing in the H2–air fuel cell (Fig. S33). The Pt3Co/S-KB stably worked at 0.6 V20,57 for more than 85 h without marked current-density decay. The highly stable current demonstrates that the stability of Pt3Co/S-KB is guaranteed. To describe the stability of the Pt3Co/S-KB in more detail, the proton transfer resistance has been tested at several critical time points (fresh, 19H, 43H, 61H, and 88H). The proton transfer impedance curves with minimal change show that the MEA prepared by Pt3Co/S-KB maintains excellent proton conductivity throughout the test, indirectly corroborating the persistent optimization effect of thiophene-S on ionomer distribution.

Ionomer distribution of catalyst layers

To unveil the real distribution of ionomer within the TPBs of the catalytic layer more intuitively, the MEAs which prepared by Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB were both characterized in two ways. Firstly, two MEAs were embedded and sliced, and then observed by STEM-EDX mapping (Fig. S34, the cathode side had been identified by observing the Co signal and Supplementary Information for details). The macroscopic distribution of ionomer before and after thiophene S modification was obtained (only one region of each sample shows here, and the complete 3 regions, which were randomly selected shown in Figs. S35 and S36). On the cathodic catalyst layer of Pt3Co/KB, F signal aggregations were observed in all three regions (orange dashed box marking the regions in Figs. 4a, b and S35), where Pt signals were barely detectable, indicating that these areas were the cluster of larger ionomer, and the overall distribution of ionomer in the catalyst layer was not homogeneous. In contrast, no such cases were found in three random regions of the S-modified Pt3Co/S-KB MEA (Figs. 4f, g and S36), indicating the more uniform ionomer distribution in this catalyst layer. Furthermore, to obtain a deeper microscopic insight of the differences in ionomer distribution in above catalyst layers, the focused ion beam (FIB) and corresponding STEM-EDX mapping were conducted (Fig. S38 and Supplementary Information for details). It can be clearly seen that the alloy nanoparticles represented by Pt signal were all evenly dispersed on the carbon support. For comparison, the accumulations of the F signal were obviously shown on the Pt3Co/KB catalyst layer (orange dotted frame marking the regions in Fig. 4c, d), indicating possible ionomer agglomeration in these regions. As shown in Fig. 4e, on the one hand, the thicker regions of these ionomers will cause the increase of O2 transport resistance; On the other hand, there must be thin or discontinuous regions in the catalyst layer, which hinder the effective transport of H3O+ 6,9. Comparatively, no aggregation of F signal was observed in the catalyst layer of thiophene S-modified Pt3Co/S-KB, suggesting that the ionomer was evenly distributed (Fig. 4h, i). The consensus was reached that a homogeneous ionomer distribution would significantly improve the gas-water transmission in TPBs, as illustrated in Fig. 4j26,27,28,31, explaining the lower independent oxygen transport resistance (Fig. 3d) and the higher dry proton accessibility (Fig. 3f) of Pt3Co/S-KB relative to Pt3Co/KB in the above section.

Slice-STEM EDX mapping of Pt3Co/KB CL (a, b) and Pt3Co/S-KB (f, g). All the samples were made by embedded and sliced the MEAs. The element distribution of Pt (red) and F (yellow) represents the distribution of the catalysts and Nafion ionomer, respectively. The orange dashed frames mark a large number of ionomers here without platinum in the Pt3Co/KB catalyst layer. FIB-STEM-EDX mapping of Pt3Co/KB (c, d) and Pt3Co/S-KB (h, i) CLs. All the samples were cut by FIB from MEAs’ cathode side. The element distribution of Pt (red) and F (yellow) represents the distribution of the catalysts and Nafion ionomer, respectively. The orange dashed circles mark the aggregation of ionomer in the Pt3Co/KB CL. The schematic diagram of ionomer and mass transport processes in the catalytic layers of Pt3Co/KB (e) and Pt3Co/S-KB (j).

Overall, all above results intuitively and clearly showed the difference in the distribution of ionomer in different catalyst layers at different scales - the introduction of thiophene S resulted in a higher degree of uniformity of the ionomer distribution. Direct structural evidence was provided for the significantly improved TPBs’ mass transport process (represented by lower \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\), and higher dry proton accessibility) of Pt3Co/S-KB MEA. It is demonstrated that the proposed modulation strategy, promoting the uniform distribution of the ionomer to obtain an ideal TPBs by introducing thiophene S on the carbon support, is reliable and efficient.

Interfacial interactions between the carbon surface and ionomer

To deeply explore the reason why the introduction of thiophene S affects the distribution of ionomer, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was carried out. First, the carbon support model was constructed (Fig. S39). The three-layer graphene structure was used as the contrast group without modifying S, containing 1920 atoms, with the bottom two layers fixed, allowing the top layer to relax during structural optimization. At the same time, the carbon structure was modified with an increasing ratio of C-S-C: S-Ox (Table S11). The carbon support models were designed to represent the experimentally observed trends reported in Figs. S2 and S9 in the supporting information. Furthermore, the MD model that represents the systems was constructed. Each basic MD model consisted of the above carbon carrier model, Nafion, O2, H2O, and hydronium ions (H3O+). The model had dimensions of 49.19 Å × 49.19 Å in the XOY plane. The structure of each Nafion chain was modeled with a backbone of fluorinated carbon, featuring ten side chains terminating in sulfonic acid groups (SO3−) (Fig. S40). Eight Nafion chains were placed in each system. COMPASS force field was adopted for all four systems58,59. The NVT ensemble was used to achieve a final equilibrate state of the systems at 298 K over a period of 1 ns. The height in the Z-direction of the model was selected to be about 100 Å (representing a more effective interaction region) to capture the dynamic snapshot after reaching equilibrium, as shown in Fig. 5a–d.

a–d The spatial distribution of the ionomer, O2 and H2O over carbon surfaces with different ratio of C-S-C:S-Ox (represent KB,S-KB 1:3,S-KB 1:2 and S-KB 1:1) after MD simulations (Capturing the dynamic snapshot of 100 Å from 200 Å modeled in the Z direction). e The interface energy between the ionomer and the carbon surface with different thiophene S content. The calculated \({E}_{{\mathrm{int}}}\) is a negative value, the bigger absolute value indicates a stronger interaction in the system and vice versa. f, g RDFs at different thiophene S content: S (thiophene S) − S (side chain) (f) and S (thiophene S) − C (main chain) (g). h The interaction between the surface of traditional carbon support (top) or carbon support modified with thiophene S (bottom) and sulfonic acid group. i Ionomer tends to accumulate among the catalyst particles due to their strong interaction with Pt. j The attraction of thiophene S on the carrier to the ionomer alleviates the buildup of the ionomer around the Pt-based nanoparticles and promotes a uniform ionomer distribution across the entire catalyst layer. k Too high content of thiophene S leads the attraction of carrier to the ionomer far exceed the interaction of the catalyst particles, which results in more ionomer accumulating on the carbon carrier, but the ionomer around the catalyst nanoparticles is thin, and even the particles are exposed, this prevents sufficient protons required for the reaction to reach the three-phase interface through the ionomer.

Obviously, as the content of thiophene S (C-S-C) on the support gradually increased, the deposited Nafion chains on the fixed height of the carbon support surface increased. It was verified by specifically counting the counted corresponding atoms of ionomer within a 0.6-nm proximity to the surface of carbon support (Fig. S41). At the same time, the interaction energy between carbon support and the ionomer was also predicted in the systems (Fig. 5e). Apparently, this value also increased with the increasing of thiophene S. All these results indicated that the thiophene S-modified carbon support enhanced the interaction with hydrated PFSA ionomer. Therefore, the interaction between thiophene S and the specific structures of PFSA ionomer was further analyzed at the atomic scale. To describe the probable distance between carbon support and groups in Nafion ionomer during the MD simulations, the radial distribution functions (RDFs) were calculated (Supplementary Information for details). As shown in Fig. 5f, g, the distance between S in thiophene S and S in side chain sulfonic acid group decreased obviously with the rise of thiophene S content, while the distance between S in thiophene S and C in the main chain remained essentially the same. Based on this, it is believed that thiophene S may mainly interact with the SO3− in nafion side chain (Fig. 5h), which in turn explains the increase of the interaction energy (Fig. 5e) and the raised number of the ionomer within a certain height of the carbon support (Figs. 5a–d and S41).

Considering the strong interaction between Pt and ionomer12,14,19,20,29,57 (Fig. 5i), the attraction of thiophene S to ionomer could provide the possibility to alleviate the accumulation of ionomer around the alloy particles. The competition between these two interactions is consistent with the more homogeneous ionomer distribution across the catalyst layer (Fig. 5j), suggesting a possible mechanism behind both the significant reduction in the \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) of the thiophene S-modified MEAs (Fig. S26) and the enhanced performance of the MEAs (Figs. S21 and S22). However, it is also noted that after excessive thiophene S modification in the carbon support (Pt3Co/S-KB 1:1, representatively), both the \({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\) and the performance were conversely poor compared to Pt3Co/S-KB 1:2. This can be interpreted that when the thiophene S content is too high, the attraction of the carrier to the ionomer may far exceeds the interaction of the catalyst particles, potentially resulting in more ionomer accumulating on the carbon carrier, but the ionomer around the catalyst nanoparticles is thin and even the particles are exposed, which could prevent sufficient protons required for the reaction to reach the three-phase interface through the ionomer (Fig. 5k), and ultimately leads to the MEA performance degrade. Consequently, it is very essential to regulate the content of thiophene-S. The modification of carbon support with appropriate content of thiophene S is thus proposed to be necessary to achieve an optimal balance between ionomer-alloy nanoparticles and ionomer-S-KB, so as to facilitate the uniform distribution of ionomer in the catalyst layer, which can reduce the oxygen transport resistance, ensure proton transport, establish an effective TPBs, and finally obtain a high-performance fuel cell with low platinum loading (as illustrated in Fig. 3, sample Pt3Co/S-KB(1:2)). Additionally, it should be noted that the molecular dynamics simulations, while providing valuable atomistic insights, employ simplified models and force fields that may not fully capture the complexity of the actual catalytic environment under operating conditions.

Discussion

In summary, we have proposed a TPBs control strategy for catalyst layer of low Pt loading PEMFC by the introduction of thiophene S (C-S-C) onto carbon support. Firstly, Pt3Co alloy catalyst was used to ensure high ORR activity. More importantly, the interaction of thiophene S and ionomer obtained the more homogeneous ionic film around the catalyst particles, which gave these TPBs the ability to promote a balanced and sufficient provision of both protons and O2 to catalyst active centers, which is evident from very high dry proton accessibility and very low pressure-independent oxygen transport resistance. Ultimately, we have achieved highly fuel cell performance under low-Pt-loading conditions and broken through the DOE-rated power target and Pt utilization target. And it has been visually demonstrated by FIB/slice-STEM EDX mapping that the uniformity of ionomer distribution was promoted by introducing thiophene S onto carbon support. We further elucidated the interaction of thiophene S with the specific structure of ionomer by calculating radial distribution functions (RDFs), interaction energy, and interface energy through molecular dynamic (MD) simulation analysis. Finally, we emphasized the importance of regulating the content of thiophene S. Only by modifying the carbon support with the appropriate content of thiophene S can we obtain an effective balance between ionomer- alloy nanoparticles and ionomer-S-KB, which resulted in the uniform distribution of ionomer. This work lays the groundwork for a deeper understanding and further regulate the microscopic TPBs of catalyst layer, supporting the exploitation and fabrication of next-generation MEAs with low platinum loading.

Methods

Synthesis of Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB 1:x(x = 1, 2 and 3)

In this study, commercial Ketjenblack EC300JD carbon powders (Lion Specialty Chemicals Co., Ltd.) were used as the pristine carbon support for further modification. Sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine (98 %, Sigma-Aldrich) was chosen as the sulfur precursor, composed of cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc) as the parent structure and sulfonic acid group (-SO3H, usually 2-4 sulfonated sites per molecule) as the periphery. The sulfonic acid group in sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine decomposes and releases SOX and sulfur radicals during high-temperature pyrolysis. The sulfur radicals are easily inserted into the C-C bond to form the target thiophene S60,61, 2-4 sulfonated sites in each molecule of the precursor ensure the final S incorporation. In a typical procedure, water and ethanol were mixed at a volume ratio of 1:1 to obtain the solvent. Then, sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine (C32H16N8Co(SO3)n = 1-4) and pristine carbon support were added to 200 ml of the above mixed solvent at a mass ratio of 1:3, 1:2, and 1:1 (Table S1). The system underwent 2 h of stirring and sonication, resulting in a uniform dispersion. Then it was dried with a rotary evaporator to obtain black powders. Following this, the resulting powder underwent a 2-h heat treatment at 900 °C in a N2 environment. A constant heating ramp of 5 °C min−1 was applied, followed by uncontrolled cooling until room temperature was reached. For purification, the samples were immersed in a sulfuric acid solution (0.5 M) and kept at 80 °C for a duration of 8 h. Following this treatment, they were repeatedly rinsed with deionized water and finally dried under vacuum at 60 °C overnight, denoted as S-KB 1:2. S-KB 1:1 and S-KB 1:3 were synthesized under identical conditions except for the mass ration of S-containing precursor (Sulfonated cobalt phthalocyanine C32H16N8Co(SO3)n=1-4) and pristine carbon support, which became 1:1/1:3.The small molecule-assisted impregnation method was used to realize small-sized Pt3Co alloy catalysts burdened on S-functionalized carbon supports.

To synthesis small-sized Pt3Co alloy catalysts burdened on S-functionalized carbon supports, 0.128 mmol H2PtCl6·6H2O (97 %, Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.233 mmol (CH3COO)2Co·4H2O (≥99.5 %, Sigma-Aldrich) were first dissolved in 80 mL ETOH by stirring for 10 min. Then, the addition of 22 μl 1-Propanethiol (S-containing molecule additives) (≥99.5 %, Sigma-Aldrich) initiated a 30-min stirring process, leading to the generation of a homogeneous, grass-green solution. The aforementioned solution was mixed with 100 mg of the respective carbon support (S-KB 1:1/S-KB 1:2/S-KB 1:3). Stirring was continued overnight to ensure homogeneity prior to drying the mixture using a rotary evaporator. The obtained powder was annealed in a two-stage protocol: 2 h at 900 °C followed by 4 h at 600 °C, with program-controlled heating and cooling at 5 °C min−1 and concluding with natural cooling to room temperature. For purification, the resulting material was treated with 0.5 M H2SO4 for 8 h at 80 °C. This procedure was followed by exhaustive rinsing with deionized water and final overnight vacuum drying at 60 °C. A Pt3Co/KB reference catalyst was synthesized following the same method, only differing in the carbon support, which was commercial Ketjenblack EC300JD. The commercially available Pt/C catalyst selected for our work was TKK TEC10E20E (20%, Tanaka), utilizing high-surface-area carbon supports. The control samples Pt3Cowithout S/KB and Pt3Cowithout S/S-KB were prepared following identical synthesis protocols as other catalysts, with the sole exception of omitting S-containing small molecule additives (1-Propanethiol) during precursor impregnation. The final Pt loading was determined by ICP-OES and is shown in Table S1 for each type of catalyst.

Physical characterization

The elemental composition of materials was quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) on a Avio® 500 instrument (PerkinElmer). This study employed a Bruker D8-ADVANCE diffractometer for obtaining the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. The system utilizes Cu Kα radiation with a fixed wavelength of 1.5406 Å. The operational parameters for the X-ray generator were set at 40 kV for the voltage and 40 mA for the current. The morphology and particle size of the synthesized samples were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These observations were carried out on an FEI Talos F200S microscope, which was operated with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was acquired on a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha+ spectrometer with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The obtained spectra were referenced by setting the adventitious carbon C 1s peak to 284.8 eV. For the deconvolution of Pt 4f peaks, the fitting procedure adhered to the following constraints: a fixed area ratio of 4:3 (4f 7/2:4f 5/2), a full width at half maximum (FWHM) ratio of 1:1, and a spin-orbit splitting value (ΔEPt 4f7/2, 5/2) of approximately 3.35 eV.

Electrochemical characterization

The electrocatalytic performance was assessed using a rotating disk electrode (RDE) setup. To fabricate the working electrode, a catalyst ink was first prepared by ultrasonically dispersing 2 mg catalyst in a mixture containing 890 μL of isopropanol (IPA), 100 μL of ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ), and 10 μL of a 5 wt% Nafion® aqueous solution. Then, 10 μL of the ink was precisely loaded onto a polished glassy carbon (GC) disk electrode (5 mm diameter) that was housed within a PTFE sleeve. The coated electrode was dried under rotation prior to electrochemical characterization. All electrochemical measurements were conducted at a constant temperature of 25 °C. A CHI-660 electrochemical workstation was employed for these tests. The three-electrode system consisted of a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) as the reference and a carbon rod serving as the counter electrode. The RDE system was sourced from Pine Research Instruments. The CV tests were performed in an electrolyte of 0.1 M HClO4, which had been saturated with N2 gas. A voltage range from 0 to 1.2 V (vs. RHE) was employed for the scanning, with the rate set to 50 mV s−1.

The electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was derived from the charge associated with the hydrogen underpotential deposition (\({H}_{{upd}}\)) region in the cyclic voltammograms. The calculation assumed a standard value of \(210\,{\mathrm{\mu C}}/{{\mathrm{cm}}}_{{\mathrm{PGM}}}^{2}\) for PGM materials, and the CV data were collected in an N2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte. The charge corresponding to hydrogen adsorption/desorption (\({Q}_{H}\)) was obtained by integrating the respective peaks around the potential window from 0.007 to 0.398 V (vs. RHE). Prior to integration, the capacitive contribution was subtracted by establishing a baseline at the current value of 0.398 V. The ECSA was then calculated using Eq. (1).

where \({m}_{{Pt}}\) represents the platinum loading on the working electrode. For improved accuracy, the value of \({Q}_{H}\) used in the calculation was taken as the average of the charges from the adsorption and desorption processes.

To probe the ORR activity, the catalysts were investigated using RDE. The electrolyte used was a 0.1 M HClO4 solution, which was saturated with high-purity O2 gas prior to all measurements. The electrode was rotated at 1600 rpm, scanning the potential from 0 to 1.2 V (vs. RHE) at a rate of 10 mV s−1.

PEMFC characterization

Membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) were fabricated using a catalyst-coated membrane (CCM) approach. The catalyst inks, formulated from ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ), isopropanol (IPA), and a 5% Nafion ionomer solution with weight ratios of 0.5 I/C, 1% solid content, and a mIPA/multrapure water of 9:1. Subsequently, these inks were applied onto an 8 μm Gore membrane via ultrasonic spraying. SEM characterization (Fig. S29) confirmed the quality of the resulting CCM, revealing crack-free surfaces and a homogeneous catalyst distribution. The loading at the cathode was set to 0.1 mgPt cm−2 for Pt3Co/KB or Pt3Co/S-KB, while the anode employed a commercial 10 wt.% Pt/C at 0.025 mgPt cm−2. The as-synthesized CCM was then hot-pressed between two gas diffusion layers to form 5 × 5 cm2 MEAs. Single-cell performance was characterized with a Scribner 850e test station under H2-Air. The tests were conducted at 94 °C or 80 °C with both gases at 100% relative humidity. During testing, the gas stoichiometry was 1.5 at the cathode and 2.0 at the anode. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted on a Zahner Zennium Pro workstation (Germany) coupled with the fuel cell test station. In this setup, the test station provided the DC load, while the impedance instrument superimposed a 5% AC perturbation in galvanostatic mode. The applied frequency spectrum spanned from 100 mHz to 50 kHz, and data were collected at various current densities. The acquired spectra were subsequently subjected to distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis.

Oxygen transport resistance test for MEA

The total oxygen mass transfer resistance (\({R}_{{total}}\)) in different MEAs was evaluated through the limit current test at 80 °C and 100%RH. During the test, hydrogen (H2) was employed as the anode gas, the cathode gas was nitrogen oxygen mixture (O2 content 1%), the flow rate was 300 and 800 sccm, and the test voltage was 0.4-0.1 V under the conditions of back pressure of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 bar. The current density value is recorded every 0.05 V, and the maximum current density is the limit current density. Equation (2) provides an approximate method for determining the total oxygen transport resistance:

where \({R}_{{total}}\) is the total oxygen transport resistance; \({C}_{{O}_{2}}\) is oxygen concentration; \({P}_{{abs}}\) is the total pressure; \({P}_{H2O}\) is the pressure of water vapor at this temperature; \({x}_{{o}_{2}-{dry}}\) is the dry O2 ratio; and \({i}_{{\mathrm{lim}}}\) is the limit current density.

According to Baker et al.62, the total O2 mass transport resistance (\({R}_{{total}}\)) can be separated in a presser dependent (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{dep}}\)) and pressure independent (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\)) part (Eq. (3)) representing intermolecular gas diffusion and Knudsen diffusion/transport through the ionomer/liquid water layer, respectively.

In detail, by varying the total pressure, the fitted \({R}_{{total}}\)l curve produces an intersection with the vertical coordinate, the intercept distance of which is the pressure-independent oxygen transport resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{ind}}\)), while the product of slope of the fitted curve and the gas pressure is the pressure-dependent oxygen transport resistance (\({R}_{o2}^{P,{dep}}\)). Since all MEAs were identical aside from the catalyst, any observed differences were attributed to the catalyst layer, while the contribution from the diffusion medium and microporous layer remained constant.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the Materials Studio Forcite Modules. First a three-layer graphene structure was constructed as a control group, containing 1920 atoms, with the bottom two layers fixed, allowing the top layer to relax during structural optimization (Model 1). Subsequently, three models containing different proportions of S-Ox and C-S-C were constructed. About 1/4 of S-Ox in Model 2 was replaced by C-S-C, about 1/3 of S-Ox in Model 3 was replaced by C-S-C, and about 1/2 of S-Ox in Model 4 is replaced by C-S-C. The specific number of atoms was C1816O24S55, C1816O21S55, C1814O17S55.

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulations commenced with the construction and optimization of all molecules and ions, including H2O, O2, nafion−, and H3O+. Each Nafion ionomer was modeled with a backbone of fluorinated carbon, featuring ten side chains terminating in sulfonic acid groups (SO3−). Each system comprised mixtures of 8 Nafion chains, a specific quantity of oxygen molecules, water molecules, and hydronium ions, with the hydration level λ (the ratio of H2O and H3O+ to SO3−)63 maintained at 10. Key parameters for the carbon carriers and the triple-phase model are provided in Table S12. All molecular structures present in this work—namely Nafion, graphite sheets, H2O, O2 and H3O+—were described using the COMPASS force field58,59. Key parameters of the COMPASS Force Field are listed in Table S13. Interactions were handled using the Ewald particle mesh summation method. The accuracy for this method was set to 10−5 kcal mol−1. To handle Van der Waals interactions, the atom-based method was employed. The interactions were truncated at a distance of 10 Å. Atomic partial charges were automatically assigned by the COMPASS forcefield based on its parameterization scheme. The system underwent geometric optimization three times using the smart algorithm. This was followed by an anneal simulation starting at 298 K, reaching a midcycle temperature of 800 K, repeated for three cycles. Finally, the systems were equilibrated at 298 K using an NVT ensemble within 1 ns.

Radial distribution functions (RDFs)

The radial distribution function (RDF), denoted as \({RDF}\left(r\right)\), quantifies the probability density of locating another atom B at a distance r from a reference particle A, as defined by Eq. (4):

Here, the term \({n}_{B}\) is interpreted as the count of B atoms residing in a thin spherical shell (thickness \({dr}\)) around A. The denominator involves \({N}_{B}\), the total count of B atoms, and V, the system’s total volume63.

The interaction energy (Eint), indicating the intensity of interaction between the components in the system, is derived from Eq. (5):

where Etotal and Ecomponentt represent the total energy of system and that of each component in the system, respectively. The calculated \({E}_{{\mathrm{int}}}\) is a negative value; the bigger absolute value indicates a stronger interaction in the system and vice versa.

FIB/slice-STEM EDX mapping analysis of catalyst layer

MEAs of Pt3Co/KB and Pt3Co/S-KB samples were initially coated with a Gatan-J1 epoxy mixture to improve stiffness, placed in a mold filled with the Embed 812 epoxy, out-gassed to remove air at the MEA/epoxy interface, and cured at room temperature for 8 h. The cured molds were microtomed at room temperature on a Leica EM UC7, using a 35° diamond knife with a boat. The electron transparent MEA cross-sections were floated on water before transferring to TEM grids (Fig. S34). Finally, they were observed by STEM EDX mapping.

For cross-sectional characterization, the GDL of the MEA was gently separated to reveal the cathode catalyst layer. The sample was then secured on a TEM holder using conductive tape. Using a ZEISS Crossbeam 540 system, we performed sequential ion beam milling: initial coarse milling at 30 kV with 20–30 nA beam current created U-shaped trenches approximately 20 μm in length and 5 μm in depth (Fig. S38c). The target region was then isolated from the bulk material while maintaining connection at one end. Subsequent fine milling at reduced currents (1 nA) progressively thinned the sample to electron transparency (Fig. S38d, e). The FIB-prepared cross-sections were subsequently analyzed by STEM-EDX to examine the ionomer distribution within the catalyst layers.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information, Source Data. Source Data files have been deposited in Figshare under accession code DOI link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3041710064. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Weydahl, H. et al. Fuel cell systems for long-endurance autonomous underwater vehicles – challenges and benefits. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 5543–5553 (2020).

Ustolin, F. & Taccani, R. Fuel cells for airborne usage: energy storage comparison. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 43, 11853–11861 (2018).

Debe, M. K. Electrocatalyst approaches and challenges for automotive fuel cells. Nature 486, 43–51 (2012).

Abdel-Baset, T. et al. USCAR Fuel cell technical team roadmap. https://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/02/f8/fctt_roadmap_june2013.pdf (2013)

Ohma, A. et al. Analysis of proton exchange membrane fuel cell catalyst layers for reduction of platinum loading at Nissan. Electrochim. Acta 56, 10832–10841 (2011).

Kongkanand, A. & Mathias, M. F. The priority and challenge of high-power performance of low-platinum proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1127–1137 (2016).

Peng, B. et al. Embedded oxide clusters stabilize sub-2 nm Pt nanoparticles for highly durable fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 7, 818–828 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Pt catalyst protected by graphene nanopockets enables lifetimes of over 200,000 h for heavy-duty fuel cell applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-01895-3 (2025).

Weber, A. Z. & Kusoglu, A. Unexplained transport resistances for low-loaded fuel-cell catalyst layers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 17207–17211 (2014).

Sun, R. et al. Periodic evolution of the ionomer/catalyst interfacial structures towards proton conductance and oxygen transport in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. Nano Energy 75, 104919 (2020).

Park, J.-H., Shin, M.-S. & Park, J.-S. Effect of dispersing solvents for ionomers on the performance and durability of catalyst layers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 391, 138971 (2021).

Subbaraman, R., Strmcnik, D., Paulikas, A. P., Stamenkovic, V. R. & Markovic, N. M. Oxygen reduction reaction at three-phase interfaces. ChemPhysChem 11, 2825–2833 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. 3D generation and reconstruction of the fuel cell catalyst layer using 2D images based on deep learning. J. Power Sources Adv. 14, 100084 (2022).

Jinnouchi, R., Kudo, K., Kitano, N. & Morimoto, Y. Molecular dynamics simulations on O2 permeation through nafion ionomer on platinum surface. Electrochim. Acta 188, 767–776 (2016).

Jinnouchi, R. et al. The role of oxygen-permeable ionomer for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 4956 (2021).

Hu, Y., Guo, X., Shen, T., Zhu, Y. & Wang, D. Hollow porous carbon-confined atomically ordered PtCo3 intermetallics for an efficient oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 12, 5380–5387 (2022).

Shin, S. et al. Carbon-embedded Pt alloy cluster catalysts for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400599 (2024).

Zhang, Q. et al. Covalent organic framework–based porous ionomers for high-performance fuel cells. Science 378, 181–186 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Oxygen- and proton-transporting open framework ionomer for medium-temperature fuel cells. Science 385, 1115–1120 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Blocking the sulfonate group in Nafion to unlock platinum’s activity in membrane electrode assemblies. Nat. Catal. 6, 392–401 (2023).

Kodama, K., Nagai, T., Kuwaki, A., Jinnouchi, R. & Morimoto, Y. Challenges in applying highly active Pt-based nanostructured catalysts for oxygen reduction reactions to fuel cell vehicles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 140–147 (2021).

Katzenberg, A. et al. Dynamic emergence of nanostructure and transport properties in perfluorinated sulfonic acid ionomers. Macromolecules 53, 8519–8528 (2020).

Li, Y., Intikhab, S., Malkani, A., Xu, B. & Snyder, J. Ionic liquid additives for the mitigation of nafion specific adsorption on platinum. ACS Catal. 10, 7691–7698 (2020).

Zhang, G., Munoz, M. & Etzold, B. J. M. Accelerating oxygen-reduction catalysts through preventing poisoning with non-reactive species by using hydrophobic ionic liquids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2257–2261 (2016).

Yarlagadda, V. et al. Boosting fuel cell performance with accessible carbon mesopores. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 618–621 (2018).

Ott, S. et al. Ionomer distribution control in porous carbon-supported catalyst layers for high-power and low Pt-loaded proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Mater. 19, 77–85 (2020).

Yan, X. et al. Structural and transport properties of ultrathin perfluorosulfonic acid ionomer film in proton exchange membrane fuel cell catalyst layer: a review. J. Power Sources 536, 231523 (2022).

Ott, S. et al. Understanding the performance increase of catalysts supported on n-functionalized carbon in PEMFC catalyst layers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169, 054520 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Engineering triple-phase boundary in Pt catalyst layers for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310428 (2024).

Ott, S. et al. Property-reactivity relations of N-doped PEM fuel cell cathode catalyst supports. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 306, 121118 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Unraveling the effects of carbon corrosion on oxygen transport resistance in low pt loading proton exchange membrane fuel cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 540–554 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Tailoring a three-phase microenvironment for high-performance oxygen reduction reaction in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Matter 3, 1774–1790 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Surface structure engineering of ptpd nanoparticles for boosting ammonia oxidation electrocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 28816–28825 (2022).

Pillai, H. S. et al. Interpretable design of Ir-free trimetallic electrocatalysts for ammonia oxidation with graph neural networks. Nat. Commun. 14, 792 (2023).

Song, T.-W. et al. Small molecule-assisted synthesis of carbon supported platinum intermetallic fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Commun. 13, 6521 (2022).

Yin, P. et al. Sulfur stabilizing metal nanoclusters on carbon at high temperatures. Nat. Commun. 12, 3135 (2021).

Xie, R. et al. Maximizing thiophene–sulfur functional groups in carbon catalysts for highly selective H2 O2 electrosynthesis. ACS Catal. 14, 4471–4477 (2024).

Yang, C.-L. et al. Sulfur-anchoring synthesis of platinum intermetallic nanoparticle catalysts for fuel cells. Science 374, 459–464 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Structurally ordered intermetallic platinum–cobalt core–shell nanoparticles with enhanced activity and stability as oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 12, 81–87 (2013).

Qiao, Z., Wang, C., Zeng, Y., Spendelow, J. S. & Wu, G. Advanced nanocarbons for enhanced performance and durability of platinum catalysts in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Small 17, 2006805 (2021).

Hou, J. et al. Platinum-group-metal catalysts for proton exchange membrane fuel cells: from catalyst design to electrode structure optimization. EnergyChem 2, 100023 (2020).

Nie, Y. et al. Low-electronegativity Mn-contraction of ptmn nanodendrites boosts oxygen reduction durability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317987 (2024).

Pan, Y.-T. et al. Ordered CoPt oxygen reduction catalyst with high performance and durability. Chem. Catal. 2, 3559–3572 (2022).

Lefebvre, M. C. Characterization of ionic conductivity profiles within proton exchange membrane fuel cell gas diffusion electrodes by impedance spectroscopy. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2, 259 (1999).

Yuan, H. et al. Understanding dynamic behavior of proton exchange membrane fuel cell in the view of internal dynamics based on impedance. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 134035 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. High-precision identification of polarization processes of proton exchange membrane fuel cells through relaxation time analysis: Targeted experimental design and verification. Appl. Energy 367, 123377 (2024).

Garlyyev, B. et al. Optimizing the size of platinum nanoparticles for enhanced mass activity in the electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9596–9600 (2019).

Padgett, E. et al. Editors’ choice—connecting fuel cell catalyst nanostructure and accessibility using quantitative Cryo-STEM tomography. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, F173–F180 (2018).

Wan, Z. H. et al. Determination of oxygen transport resistance in gas diffusion layer for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 42, 2225–2233 (2018).

Islam, M. N. et al. Designing fuel cell catalyst support for superior catalytic activity and low mass-transport resistance. Nat. Commun. 13, 6157 (2022).

Li, A. et al. Air oxidation of carbon supports boosts the low-humidity fuel cell performance. Chem. Commun. 60, 4226–4229 (2024).

Nonoyama, N., Okazaki, S., Weber, A. Z., Ikogi, Y. & Yoshida, T. Analysis of oxygen-transport diffusion resistance in proton-exchange-membrane fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, B416 (2011).

Cheng, K. et al. The local oxygen transport resistance of ultra-low platinum loading cathode catalyst layer. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 17, 220518 (2022).

Owejan, J. P., Owejan, J. E. & Gu, W. Impact of platinum loading and catalyst layer structure on PEMFC performance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160, F824–F833 (2013).

Kreuer, K., Rabenau, A. & Weppner, W. Vehicle mechanism, A new model for the interpretation of the conductivity of fast proton conductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 21, 208–209 (1982).

Handbook of Fuel Cells: Fundamentals, Technology and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470974001 (Wiley Interscience, 2010).

Chen, F. et al. Overcoming the limitation of ionomers on mass transport and Pt activity to achieve high-performing membrane electrode assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30388–30396 (2024).

Sun, H., Ren, P. & Fried, J. R. The COMPASS force field: parameterization and validation for phosphazenes. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 8, 229–246 (1998).

Sun, H. COMPASS: an ab initio force-field optimized for condensed-phase applications-overview with details on alkane and benzene compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 7338–7364 (1998).

Peng, J., Zhu, R., Wei, G., Wang, L. & Yu, C. Rough-surfaced polybenzimidazole membranes incorporating sulfonated porous aromatic frameworks for simultaneous enhancement of proton conduction and membrane electrode assembly optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155136 (2024).

Zheng, Y.-H. et al. Thermal decomposition and oxidation of cation exchange resins with and without Na 2 CO 3 –K 2 CO 3 salt. Environ. Technol. Innov. 28, 102601 (2022).

Caulk, D. A. & Baker, D. R. Heat and water transport in hydrophobic diffusion media of PEM fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1237 (2010).

Duan, X. et al. The design strategy of Pt-based electrocatalysts: insights from mass transport of fuel cells. Mater. Today Energy 40, 101503 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Ionomer distribution control via thiophene S-modification of carbon support for high-power proton exchange membrane fuel cells. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30417100 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB4301703 of T.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22278123 of Jia Li), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22538003 of Jianguo Liu), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52202234 of T.Y.) and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by BAST (BYESS2023073 of T.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z.: Writing—original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jia Li: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. C.W.: Validation, Formal analysis. X.L.: Methodology, Formal analysis. Q.Y.: Methodology, Formal analysis. Q.Z. K.L. and Y.W.: Validation, Investigation. T.Y.: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. J.L.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Project administration. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the paper. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Marcelo M. Mariscal, Jasna Jankovic, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Li, J., Wang, C. et al. Ionomer distribution control via thiophene S-modification of carbon support for high-power proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat Commun 16, 11670 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66813-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66813-6