Abstract

Crop rotation is widely practiced to improve agricultural sustainability, yet its impact on microbial diversity remains unclear. We conduct a global meta-analysis of 2406 paired observations to examine the effects of crop rotation on microbial diversity based on high-throughput sequencing data. We show that crop rotation significantly increases bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness, but has no effect on bacterial beta diversity. In contrast, crop rotation significantly increases fungal beta diversity without affecting fungal Shannon diversity and species richness. Changes in microbial communities are linked to soil pH, and available nitrogen and phosphorus. Notably, legume vs. non-legume, arbuscular mycorrhiza vs. non- arbuscular mycorrhiza, C3 vs. C4, and annual vs. perennial crop transitions, as well as climate and soil factors, affect the response ratios of microbial metics to crop rotation. Furthermore, the response ratios of bacterial Shannon diversity, bacterial species richness, and fungal species richness are positively related to the response ratio of crop yield. Our study reveals positive but differential effects of crop rotation on bacterial and fungal diversities, which are linked to improved crop productivity. Our findings thus have implications for using crop rotation to conserve soil microbial biodiversity, which is related to soil health and function, and enhance global food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

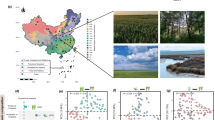

The increasing global demand for agricultural crop production necessitates the more efficient use of existing croplands to enhance productivity and meet the growing need for food security1. Traditional monocultural cropping systems rely heavily on the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which can cause significant environmental challenges, including soil degradation and nutrient loss2, and reduce agricultural sustainability. In this context, maintaining and enhancing soil health and productivity have become critical for sustainable agricultural intensification. Crop rotation, the sequential cultivation of different crops on the same land3, has been practiced for centuries as a strategy to restore soil health and increase crop productivity4. Unlike monocultural continuous cropping systems, crop rotation enhances soil carbon (C) input through increased above- and belowground litter inputs, including the release of root exudates5,6. Increased organic matter input improves soil structure by increasing the formation and stability of aggregates, which increases soil porosity; those effects collectively enhance soil function, including nutrient cycling and retention7,8 (Fig. 1).

‘+’ represents expected positive responses to crop rotation, while ‘+/−’ denotes either positive, negative or no responses to crop rotation. The symbol ‘?’ highlights three critical questions: 1) does crop rotation reshape microbial diversity and structure on a global scale? If so, do bacterial and fungal community diversities and structures respond to crop rotation in the same way? and 2) how do the transitions between different crop types in a crop rotation, crop transition, crop growth stage, rotational cycles, crop species richness, soil characteristics, and climatic factors modulate these responses? The conceptual diagram was created using BioRender elements (Created in BioRender. Ma, S. (https://BioRender.com/bncog3m).

Soil microbial communities harbor immense diversity, with billions of microorganisms in a single gram of soil9. Soil microbial diversity plays a crucial role in ecosystem functions, including litter decomposition and organic matter mineralization10,11,12. Additionally, microbial community structure, particularly the existence of rare and keystone microbial taxa, also serves as a major driver of ecosystem functions13,14. Variations in the release of root exudates and soil nutrients induced by crop rotation directly alter resource availability for soil microbes, reshaping bacterial and fungal diversity and structure15,16 (Fig. 1). Additionally, soil pore systems provide diverse habitats for microorganisms17, with the microenvironment within aggregates protect microbes from environmental and biological stresses such as drought and predation18. Together, changes induced by crop rotation provide a greater amount of and more diverse resources for microbes and drive changes in microbial diversity and community structure.

A meta-analysis conducted about ten years ago and a more recent meta-analysis investigated the impact of crop rotation on soil microbial diversity19,20; however, many of the studies included in those two meta-analyses were based on data from community-level physiological profiling, a method that primarily reflects microbial functional metabolic diversity rather than taxonomic diversity21, limiting our understanding of the responses of true microbial taxonomic diversity to crop rotation. In contrast, high-throughput sequencing provides quantitative delineations of microbial species and a more comprehensive characterization of microbial community Shannon diversity, microbial species richness, and microbial community structure22. Despite advancements in methodology for analyzing microbial communities and the greater availability of sequencing data, global analysis of how soil microbial communities respond to crop rotation globally based on high-throughput sequencing data is lacking (Fig. 1). Moreover, soil bacteria tend to be more sensitive than fungi to changes in nutrient availability16 and are also more vulnerable to environmental disturbances23. These differences are further influenced by their competitive interactions for soil resources24. However, whether bacterial and fungal communities respond differently to resource availability and environmental changes induced by crop rotation remains unclear (Fig. 1).

Plant communities with a mixture of species have been shown to have higher soil nutrient availabilities, microbial biomass, and microbial functions compared to monocultures25,26,27. In crop rotational systems, however, the sequential rotation of multiple crop species over time differs from cultivating multiple species simultaneously on the same piece of land. Crop rotation represents dynamic shifts in plant species composition over time. The extent to which the number of crop species in a rotation (species richness), the number of rotational cycles, and rotation duration influence soil microbial community responses also remains unclear. Moreover, multiple factors, such as the crop type or the management practices28, the soil condition29, the spatial scale30, and the climate31, influence soil microbial diversity and community structure. However, the roles of management practices (e.g., crop type, rotational cycle, and rotation duration), soil characteristics (e.g., soil texture and other physicochemical properties), and climatic conditions in shaping microbial responses to crop rotation remain poorly understood (Fig. 1).

To address these knowledge gaps, we conduct a global meta-analysis based on 2406 paired observations from 148 studies, solely based on high-throughput sequencing data, to evaluate the effects of crop rotation on bacterial and fungal diversity and structure. This comprehensive approach allows us to address two critical questions (Fig. 1): 1) does crop rotation reshape microbial diversity and structure on a global scale? If so, do bacterial and fungal community diversities and structures respond to crop rotation in the same way? and 2) how do the transitions between different crop types in a crop rotation, the number of rotational cycles, rotation duration, crop species richness, crop growth stage, soil characteristics, and climatic factors modulate these responses? Specifically, our global meta-analysis shows that crop rotation increases bacterial, but not fungal, alpha diversity, with the opposite effects on the beta diversity, and alters the community structures of both groups. Those effects were stronger under legume-to-non-legume transitions, more rotational cycles, and longer durations. Furthermore, higher microbial diversity is positively associated with crop yield, suggesting the potential role for microbial diversity to serve as an indicator for sustainable soil and crop management. These findings provide strong evidence for the complex interactions among crop rotation, crop management, environmental factors, and soil microbial communities, offering practical strategies for sustainable agricultural management worldwide.

Results

Overall effects of crop rotation on soil microbial communities

Crop rotation significantly increased bacterial Shannon diversity (response ratio = 0.013, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.008 – 0.019) and species richness (0.039, CI: 0.023 – 0.057) (Fig. 2a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), did not affect bacterial beta diversity (−0.080, CI: −0.184 – 0.020) (Fig. 2c, and Supplementary Fig. 1c), but changed bacterial community structure (0.974, CI: 0.942 – 1.055) (Fig. 2d, and Supplementary Fig. 1d). For fungal communities, crop rotation did not affect their Shannon diversity (0.001, CI: −0.018 – 0.017) and species richness (0.011, CI: −0.010 – 0.037) (Fig. 3a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1e, f), but significantly increased their beta diversity (0.165, CI: 0.055 – 0.269) and changed their community structure (1.014, CI: 0.932 – 1.095) (Fig. 3c, d, and Supplementary Fig. 1g, h).

a bacterial Shannon, b bacterial species richness, c bacterial community beta diversity, and d bacterial community structure. The number of paired observations is shown beside each attribute, with the number of publications in parentheses. Error bars represent the mean effect size ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Solid yellow circles indicate mean values less than zero, which were significantly lower under crop rotation compared to continuous monoculture; solid blue circles indicate mean values greater than zero, which were significantly higher. Open circles indicate no significant effect of crop rotation. For each pair of subgroups, the statistical significance was determined using two-sided Z-tests. P-values from the pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple testing. Subgroups with the same letters are not significantly different, while those with different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). The QM statistic is computed using the one-sided chi-square test. AM: arbuscular mycorrhiza crop, MAP: mean annual precipitation, MAT: mean annual temperature. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

a fungal Shannon, b fungal species richness, c fungal community beta diversity, and d fungal community structure. The number of paired observations is shown beside each attribute, with the number of publications in parentheses. Error bars represent the mean effect size ± 95% CIs. Solid yellow circles indicate mean values less than zero, which were significantly lower under crop rotation compared to continuous monoculture; solid blue circles indicate mean values greater than zero, which were significantly higher. Open circles indicate no significant effect of crop rotation. For each pair of subgroups, the statistical significance was determined using two-sided Z-tests. P-values from the pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple testing. Subgroups with the same letters are not significantly different, while those with different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). The QM statistic is computed using the one-sided chi-square test. AM: arbuscular mycorrhiza crop, MAP: mean annual precipitation, MAT: mean annual temperature. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Crop management influences the effect of crop rotation on soil microbial communities

The effect of crop rotation on bacterial Shannon diversity (0.021, CI: 0.011 – 0.032 vs. 0.010, CI: −0.001 – 0.020), fungal beta diversity (0.107, CI: −0.108 – 0.323 vs. −0.074, CI: −0.277 – 0.129), and their community structure (1.042, CI: 0.853 – 1.23 vs. 0.82, CI: 0.637 – 1.004) was significantly higher when transitioning from legume to non-legume crops than in the reverse transition (Figs. 2a, d and 3c, d). In contrast, the effects of crop rotation on bacterial beta diversity (−0.308, CI: −0.519 – −0.097 vs. −0.177, CI: −0.371 – 0.017), fungal Shannon diversity (−0.080, CI: −0.119 – −0.042 vs. 0.030, CI: −0.007 – 0.067), and species richness (−0.040, CI: −0.080 – 0.000 vs. 0.025, CI: −0.014 – 0.063) were significantly lower when transitioning from legume to non-legume crops compared to the reverse transition (Figs. 2c and 3a, b). The response ratios of soil microbial indices were also affected by AMF vs. non-AMF, C3 vs. C4, annual vs. perennial transitions, management practices such as tillage vs. no tillage and crop residue retention vs. no retention, soil compartments such as rhizosphere vs. bulk soil, and plant growth stages (Figs. 2 and 3, and see Supplementary Note 1 for details).

The response ratio of bacterial beta diversity, but not other microbial attributes, to crop rotation significantly decreased with increasing crop species richness (F(1, 101.3) = 21.5, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Similarly, the response ratio of fungal beta diversity significantly reduced with increasing number of rotational cycles (F(1, 96.9) = 5.6, P = 0.020) (Supplementary Fig. 2o). In contrast, crop rotation duration did not affect any response ratios of microbial attributes (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). However, subgroup analyses showed that crop rotation had significantly greater effects on bacterial Shannon diversity (0.018, CI: 0.008 – 0.028 vs. 0.013, CI: 0.003 – 0.022) and species richness (0.071, CI: 0.036 – 0.107 vs. 0.033, CI: 0.002 – 0.064) in three-species systems than in two-species systems (Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, the opposite was observed for bacterial beta diversity (−0.677, CI: −0.889 – −0.464 vs. 0.026, CI: −0.149 – 0.201) and fungal community structure (0.608, CI: 0.385 – 0.831 vs. 1.079, CI: 0.908 – 1.251) (Figs. 2c and 3d).

Response ratios for bacterial Shannon diversity (0.020, CI: 0.008 – 0.032 vs. −0.003, CI: −0.015 – 0.010), beta diversity (0.041, CI: −0.173 – 0.254 vs. −0.210, CI: −0.425 – 0.006), and community structure (1.285, CI: 1.094 – 1.476 vs. 0.714, CI: 0.522 – 0.906), and fungal species richness (−0.004, CI: −0.051 – 0.043 vs. −0.040, CI: −0.088 – 0.008) and community structure (1.538, CI: 1.322 – 1.751 vs. 0.684, CI: 0.466 – 0.902), were significantly higher in systems with ≤1 rotational cycle than in those with 1-3 cycles (Figs. 2a, c, d and 3b, d). In contrast, bacterial species richness (0.049, CI: 0.014 – 0.085 vs. −0.001, CI: −0.037 – 0.034) and fungal beta diversity (0.108, CI: −0.102 – 0.318 vs. −0.110, CI: −0.311 – 0.090) were higher in the 1-3 cycle group than in the ≤1 rotational cycle group (Figs. 2b and 3c). Crop rotation significantly increased bacterial species richness (0.104, CI: 0.062 – 0.146 and 0.101, CI: 0.048 – 0.155), and community structure (0.902, CI: 0.694 – 1.110 and 0.797, CI: 0.572 – 1.022) in systems with 5-10 and > 10 cycles (Fig. 2a, b, d), and significantly increased fungal species richness (0.114, CI: 0.048 – 0.180), beta diversity (0.755, CI: 0.519 – 0.991), and community structure (0.595, CI: 0.362 – 0.828) in 5-10 cycles (Fig. 3b–d). Response ratios for bacterial species richness (0.104, CI: 0.056 – 0.153; 0.236, CI: 0.165 – 0.307 vs. 0.014, CI: −0.024 – 0.053) and community structure (1.271, CI: 1.053 – 1.489; 1.215, CI: 0.964 – 1.466 vs. 0.956, CI: 0.761 – 1.151), and fungal species richness (0.160, CI: 0.085 – 0.235; 0.152, CI: 0.061 – 0.242 vs. −0.060, CI: −0.115 – −0.006) and beta diversity (0.357, CI: 0.118 – 0.596; 0.661, CI: 0.378 – 0.944 vs. −0.092, CI: −0.286 – 0.101) were significantly higher in the 10-20 (duration of crop rotation) and 20-30 year groups than in the ≤5-year group (Figs. 2b, d and 3b, c). However, the response ratio of fungal community structure (0.788, CI: 0.581 – 0.995; 0.837, CI: 0.596 – 1.078 vs. 1.120, CI: 0.932 – 1.307) to rotation was significantly lower in the 10-20 and 20-30 year groups than in the ≤5-year group (Fig. 3d). Finally, the response ratios of bacterial Shannon diversity (0.034, CI: 0.012 – 0.055 vs. 0.004, CI: −0. 008– 0.016), and fungal species richness (0.052, CI: −0.046 – 0.150 vs. −0.060, CI: −0.115 – −0.006) and beta diversity (0.511, CI: 0.238 – 0.784 vs. −0.092, CI: −0.286 – 0.101) to rotation were significantly higher in the 5-10 year group than in the ≤ 5 year group (Figs. 2a and 3b, c).

Climate and soil factors modulate the impact of crop rotation on soil microbial communities

Random forest models identified mean annual temperature (MAT) and precipitation (MAP), longitude, and latitude as significant predictors for the response ratios of bacterial species richness (% Increase in MSE (%IncMSE) = 21.4%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 12.3% P = 0.020; %IncMSE = 13.1% P = 0.030; %IncMSE = 14%, P = 0.010, respectively), beta diversity (%IncMSE = 16.6%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 20.2%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 18.9%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 21.4%, P = 0.010, respectively), community structure (%IncMSE = 18.4%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 22.8%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 22.6%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 24.9%, P = 0.010, respectively), fungal Shannon diversity (%IncMSE = 26.2%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 21.4%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 15.9%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 14.2%, P = 0.030, respectively), beta diversity (%IncMSE = 18.3%, P = 0.020; %IncMSE = 14.4%, P = 0.040; %IncMSE = 14.9%, P = 0.040; %IncMSE = 15.2%, P = 0.040, respectively), and community structure (%IncMSE = 27%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 20.8%,, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 27.5%, P = 0.01; %IncMSE = 23.7%, P = 0.010, respectively) (Fig. 4). Additionally, the response ratios of bacterial Shannon diversity (%IncMSE = 12.2%, P = 0.010), species richness (%IncMSE = 15.5%, P = 0.040), beta diversity (%IncMSE = 17.6%, P = 0.010), and community structure (%IncMSE = 13.9%, P = 0.030), along with fungal beta diversity (%IncMSE = 14.9%, P = 0.020) and community structure (%IncMSE = 21.6%, P = 0.010), were significantly influenced by soil organic carbon (SOC) (Fig. 4a–d, g, h). Soil pH significantly predicted the response ratios of bacterial species richness (%IncMSE = 15.8%, P = 0.020) and community structure (%IncMSE = 19.1%, P = 0.010), and fungal community structure (%IncMSE = 15.1%, P = 0.010) (Fig. 4b–d, g, h). Crop rotational duration and the number of crop rotation cycles significantly predicted the response ratios of bacterial community structure (%IncMSE = 13.8%, P = 0.020; %IncMSE = 13.9%, P = 0.020, respectively), and fungal Shannon diversity (%IncMSE = 15.9%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 14%, P = 0.010, respectively), species richness (%IncMSE = 11.7%, P = 0.049; %IncMSE = 11%, P = 0.049, respectively), and community structure (%IncMSE = 23%, P = 0.010; %IncMSE = 20.7%, P = 0.010, respectively) (Fig. 4d–f, h).

a–h Variable importance analysis based on random forest models for eight microbial attributes: a bacterial Shannon, b bacterial species richness, c), bacterial community beta diversity, d bacterial community structure, e), fungal Shannon, f fungal species richness, g), fungal community beta diversity, and (h), fungal community structure. Mean squared errors (MSE) show the importance of main predictors, and the higher percentage of increase in MSE means more important. The independent variables include mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), longitude, latitude, the number of rotational cycles, species richness, rotation duration, soil pH, and soil organic carbon (SOC). (i–l) SEM analysis for soil microbial metrics. Arrows represent the directional influence of one variable on another. Numbers beside the arrows indicate the corresponding standardized path coefficients (r). All coefficients are statistically significant at α = 0.05, tested using two-sided significance tests, with P-values shown in parentheses. R2marginal and R2conditional represent the level of deviance of the variable explained by all paths from the fixed effects and both the fixed and random effects (StudyID), respectively. Fisher’s C statistic is compared against a chi-square distribution (right-tailed test) and the corresponding P-value to evaluate overall model fit. Solid lines signify significant effects of causality, dashed lines signify no-significant effects of causality. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Climate factors and initial soil properties had generally limited effects on the response ratios of microbial diversity and structure indices (Supplementary Figs. 3–5), but subgroup analyses revealed significant regional differences. Crop rotation effects on the response ratio of bacterial beta diversity and community structure were dependent on the latitude of the study site (Fig. 2c, d; and Supplementary Note 1), while those on bacterial and fungal community structure were dependent on the longitude (Figs. 2d and 3d; and Supplementary Note 1). The crop rotation effects on bacterial species richness, fungal species richness, beta diversity and community structure were related to MAP (Figs. 2b and 3b–d; and Supplementary Note 1), while that on bacterial and fungal species richness and fungal beta diversity were related to MAT (Figs. 2b and 3b, c; and Supplementary Note 1). Crop rotation significantly altered both bacterial and fungal community structures (0.974, CI: 0.942 – 1.055 and 1.014, CI: 0.932 – 1.095) (Figs. 2d and 3d), with significantly decreased fungal species richness in fine-textured soils (−0.107, CI: −0.206 – −0.008) (Fig. 3b), but not in other soil textural classes.

Structural equation modeling showed that MAT indirectly increased the response ratio of bacterial Shannon diversity by enhancing the response ratio of soil pH (standardized path coefficient = 0.31, P = 0.035, Fisher’s C = 4.50, df = 2; Fig. 4i), and crop species richness indirectly increased the response ratio of fungal species richness by enhancing the response ratio of SOC (standardized path coefficient = 0.44, P = 0.001, Fisher’s C = 8.13, df = 2; Fig. 4l); no other relationships were found (Fig. 4j, k, and Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, crop transition effects on bacterial and fungal metrics were strongly shaped by latitude, longitude, MAT, and MAP, with certain transitions (e.g., legumes to non-legumes, C3 to C4, AM to non-AM) exhibiting contrasting responses under different environmental conditions (Supplementary Figs. 7–10 and Supplementary Note 2).

Relationships between response ratios of microbial attributes and soil physicochemical properties and crop yield

The response ratios of bacterial Shannon diversity (Spearman’s R = 0.27, P = 0.0001) and bacterial species richness (R = 0.20, P = 0.006) were positively correlated with that of soil pH (Fig. 5a), and the response ratio of bacterial community structure was positively correlated with those of soil pH (R = 0.34, P < 0.0001), total nitrogen (N) (R = 0.24, P = 0.016), nitrate (NO3-) (R = 0.29, P = 0.039), and available potassium (R = 0.21, P = 0.041) (Fig. 5a). The response ratio of fungal species richness was positively correlated with those of soil pH (R = 0.25, P = 0.002), SOC (R = 0.26, P = 0.004), and ammonium (NH4+), while the response ratio of fungal beta diversity was negatively correlated with those of NO3- (R = −0.33, P = 0.03), and NH4+ (R = −0.33, P = 0.037) (Fig. 5b). Finally, the response ratio of crop yield was positively correlated to those of bacterial Shannon diversity (R = 0.30, P = 0.007), bacterial species richness (R = 0.34, P = 0.021) and fungal species richness (R = 0.39, P = 0.023), but the response ratio of crop yield was not correlated to those of beta diversity and community structure of both bacteria and fungi (Fig. 5c).

a Spearman’s correlations between response ratios of bacterial attributes and response ratios of soil physicochemical properties, b Spearman’s correlations between response ratios of fungal attributes and response ratios of soil physicochemical properties, c Spearman’s correlations between response ratios of microbial attributes and response ratios of crop yield. Soil physicochemical properties include pH, organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), nitrate (NO3-), ammonium (NH4+), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), and available nitrogen (AN). Black lines represent the average responses with their 95% CIs shaded in grey. n represents the number of observations. P values indicate significance (two-sided) and are adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method with sequentially modified Bonferroni correction (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001).

Discussion

Crop rotation differently affects bacterial and fungal diversities

Two previous meta-analyses relied on data either partially or fully from community-level physiological profiling, which does not provide information on taxonomic diversity19,20. These meta-analyses either only reported on bacterial diversity without information on fungal diversity19 or only on microbial Shannon diversity and species richness, without differentiating between bacterial and fungal diversities20. In contrast, our meta-analysis is based on high-throughput sequencing data, distinguishes between bacterial and fungal communities, and reveals that bacterial and fungal communities responded differently to crop rotation. Specifically, we found that crop rotation significantly increased bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness (Fig. 2a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), consistent with a previous meta-analysis that also reported increased bacterial Shannon diversity under crop rotation19. Crop rotation introduces more diverse plant species into the agroecosystem, thereby increasing inputs of aboveground litter and belowground root exudates6,32. The more diverse substrates that become available in crop rotation systems create wider ecological niches, fostering greater bacterial alpha diversity33. Additionally, many soil bacteria species are known to co-evolve with specific crop hosts and exhibit strong host preferences34. The introduction of different crops can therefore reshape rhizosphere microbial communities through distinct crop-microbe interactions35. This host-specific selection likely contributes to increased bacterial diversity under crop rotation.

Similar to bacteria, some fungal species, such as mycorrhizal and endophytic fungi, are also known to co-evolve with specific crop hosts and exhibit strong host preferences36, we did not find crop rotation effects on fungal Shannon diversity and species richness (Fig. 3a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1e, f), in contrast to the significant positive effects observed for bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness. The lack of crop rotation effects on fungal Shannon diversity and species richness may be partly explained by primer biases; the ITS primers commonly used in publications included in this meta-analysis are known to preferentially amplify saprotrophic fungi while under amplify mycorrhizal taxa, potentially leading to an underestimation of the mycorrhizal community compared to the saprotrophic community. Moreover, the different responses of bacterial and fungal Shannon diversity and species richness to crop rotation (Figs. 2a, b and 3a, b) likely reflect their contrasting resistance and resilience to environmental change. Bacterial communities are generally more dynamic and responsive to environmental variation due to their faster growth rates, greater dispersal capacity, and flexible resource-use strategies37,38. These traits confer lower resistance but higher resilience39. Consequently, crop rotation, by altering root exudates, nutrient availability, and soil structure, may stimulate bacterial turnover and community restructuring, leading to increased bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness. In contrast, fungal communities often display higher resistance but lower resilience than bacterial communities39. They tend to maintain relatively stable structures under environmental disturbances. Many filamentous fungi, particularly saprotrophic decomposers, grow slowly, have long generation times, and form persistent mycelial networks24. These traits stabilize fungal community composition and support the gradual decomposition of complex organic compounds40, which may limit their ability to rapidly adjust to changes induced by crop rotations. This limitation may explain the absence of significant changes in fungal Shannon diversity and species richness that were observed in our study.

The lack of crop rotation effects on bacterial beta diversity (Fig. 2c, and Supplementary Fig. 1c) was likely related to crop rotation practices reducing environmental filtering by moderating soil pH and nutrient levels41. Combined with the high dispersal ability and metabolic redundancy of bacteria42, these conditions contribute to community convergence across treatments. In contrast, fungal beta diversity significantly increased under crop rotation (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 1g), which may be attributed to fungal communities being driven by dual drivers of host-specific root secretions and diffusion restrictions43. While crop rotation homogenized some soil properties, it may not remove variation in root exudates, organic matter inputs, and microhabitat conditions, resulting in increased fungal beta diversity. Moreover, fungi generally have more constrained dispersal mechanisms compared to bacteria44, which may further amplify variability in fungal community composition across microenvironments. Consequently, crop rotation did not affect fungal alpha diversity but increased beta diversity, reflecting their dependence on stable resource inputs and sensitivity to micohabitat heterogeneity45. Despite these contrasting diversity responses, crop rotation significantly altered both bacterial and fungal community structure (Fig. 3d, h), due to the introduction of diverse plant species, which contribute varying types of root exudates and plant residues to the soil46. These inputs increase the diversity of available resources, supporting distinct microbial groups. Additionally, crop rotation modifies soil conditions such as pH and organic carbon content47 that also influence microbial community structure.

Crop transitions differently affect bacterial and fungal communities

The increase in bacterial Shannon diversity and shifts in bacterial community structure after legume to non-legume crop type transition (Fig. 2a, d) are mainly due to changes in N availability and soil nutrient cycling. Legumes fix atmospheric N through rhizobia symbiosis and enrich the soil with bioavailable N, i.e., ammonium and nitrate48,49. When replaced by non-legumes, plants rely more on soil N, altering bacterial competition and selection pressures50. This shift favors bacteria taxa involved in N mineralization and decomposition, leading to increased diversity and structural changes. Additionally, legumes are known to release root exudates rich in flavonoids and phenolics, which can selectively enrich certain bacterial taxa in the rhizosphere51. Previous studies have shown that such compounds play key roles in shaping bacterial community composition, particularly by promoting symbiotic and beneficial bacteria such as Rhizobium and Pseudomonas52,53. Therefore, the loss or reduction of these compounds during transitions from legumes to non-legumes may contribute to more pronounced bacterial community restructuring, compared to the reverse transition, where symbiotic N-fixing bacteria gradually re-establish dominance51. Moreover, the increased fungal community beta diversity and shifts in fungal structure with a legume to non-legume crop type transition (Fig. 3c, d) were likely due to disruptions in fungal symbioses. Many legumes are associated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), which enhance phosphorus uptake and shape fungal communities54. Replacing legumes with non-legumes can break these AMF-dependent networks and increase beta diversity by recruiting saprotrophic and pathogenic fungi55. Differences in litter input and root architecture between legumes and non-legumes further influence soil microhabitats and resource availability for fungi56, promoting new fungal taxa and greater spatial heterogeneity.

The significantly greater changes in fungal Shannon diversity and species richness observed in non-legume-to-legume crop transitions compared with the reverse transition (Fig. 3e, f) are likely driven by legumes promoting specific plant-fungal mutualisms, particularly with AMF, thereby increasing fungal diversity57. Consequently, when non-legumes replace legumes, the potential for further diversity gains is limited, resulting in smaller observed changes. This interpretation is further supported by the larger increases in fungal Shannon diversity and species richness observed in non-AM-to-AM crop transitions, compared with the reverse transition (Fig. 3a, b). Such mutualisms may provide a competitive advantage to previously rare fungal taxa, enhancing species richness. Additionally, legumes contribute more C and complex root exudates, stimulating microbial activity and supporting diverse fungal groups, particularly saprotrophic and mycorrhizal fungal groups58. The introduction of legumes into a crop rotation system allows fungal communities to gradually assemble, fostering species coexistence and increasing alpha diversity. Crop rotation effects on bacterial and fungal diversity were strongly influenced by C3 vs. C4, annual vs. perennial transitions, tillage vs. no tillage, crop residue retention vs. no retention, rhizosphere vs. bulk soil, and plant growth stage. Transitions between crops with contrasting photosynthetic pathways, life cycles, or mycorrhizal associations, as well as differences in root exudation patterns and residue inputs, were key drivers of microbial community responses (please see Supplementary Discussion for details).

Crop species richness and rotational timescales shape microbial community responses to crop rotation

Increasing crop species richness from two to three species enhanced the effects of crop rotation on bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness (Fig. 2a, b). This may be because two-species rotations often involve highly contrasting crops, such as legumes and non-legumes, which cause strong shifts in rhizosphere conditions. Such contrasts can lead to greater microbial turnover through changes in root exudates, nutrient inputs, and crop-specific microbial associations46. In contrast, three-species rotations may include crops with overlapping functional traits or nutrient demands, resulting in more moderate shifts in soil conditions and microbial communities. However, crop rotation reduced the response of bacterial beta diversity (Fig. 2c), possibly because more diverse plants in rotation systems increase functional redundancy, leading to more similar bacterial communities within a site and consequently reducing beta diversity59.

In systems with ≤1 cycle, response ratios for multiple bacterial and fungal attributes were highest (Figs. 2a, c, d and 3b, d), likely reflecting the strong disturbance effect of breaking long-term monoculture, which can disrupt pathogen accumulation and alter competitive hierarchies in microbial communities60. At an intermediate range of 1-3 cycles, bacterial species richness and fungal beta diversity increased (Figs. 2b and 3c), suggesting that communities were in a transitional phase of reassembly. In the 5-10 cycle range, crop rotation consistently enhanced bacterial alpha diversity and fungal richness and beta diversity (Figs. 2a, b and 3b, c), indicating the establishment of more stable crop-microbe associations and the accumulation of legacy effects that promote diversity61.

The higher bacterial species richness and community structure, and fungal species richness and beta diversity in the 10-20 and 20-30 year groups than in the ≤5 year group (Figs. 2b, d and 3b, c) indicate that crop rotational duration also shaped microbial responses. Long-term crop rotations promote persistent changes in soil organic matter quality and nutrient cycling, which cumulatively enhance alpha and beta diversity62,63. However, the lower fungal community structure in the 10-20 and 20-30 year groups than in the ≤5 year group (Fig. 3d) may be caused by long-term rotation gradually filtering fungal communities towards a stable set of taxa well adapted to the rotation regime, thereby reducing compositional variability and the magnitude of structural changes64. In contrast, the highest responses in bacterial Shannon diversity and fungal richness and beta diversity in the 5-10 year group (Figs. 2a and 3b, c) suggest that intermediate durations in crop rotation may represent a transitional stage in which rotation-driven changes in plant biomass input, soil resource availability, and microhabitats have accumulated enough to stimulate microbial diversification, but community convergence towards a stable core community has not yet fully occurred20.

Climatic and soil factors modulate microbial community responses to crop rotation

Our findings also indicate that both climatic variables and soil properties are key drivers of microbial responses to crop rotation, although their effects are highly context dependent. Random forest analysis identified MAT, MAP, latitude, and longitude as strong predictors of multiple bacterial and fungal diversity and community structure metrics, underscoring the role of biogeographic and climatic gradients in shaping rotation effects19,62. Higher MAP (> 1200 mm) amplified the effects of rotation on fungal species richness and community structure (Fig. 3b, d), likely because greater precipitation enhances soil water availability, promotes plant biomass production, and increases plant litter inputs, which in turn increase substrate availability for fungi through organic matter decomposition65. In contrast, low MAP (≤600 mm) had higher bacterial species richness and fungal beta diversity (Figs. 2b and 3c), potentially because limited water availability increases heterogeneity across treatments in soil moisture and nutrient availabilities, fostering niche differentiation and enhancing microbial turnover66. Microbial responses were weaker at intermediate MAT (8-15 °C) (Figs. 2b and 3c), possibly due to relatively stable soil thermal regimes in these regions, which limit rotation-induced changes in resource availability and habitat conditions. In such environments, microbial communities often maintain stable diversity and composition in the absence of extreme climatic stresses12,67, resulting in reduced responsiveness to additional management interventions such as changes in crop rotation.

Although soil properties such as SOC and pH are well known to influence microbial communities, initial soil properties did not affect microbial responses to crop rotation in this study (Supplementary Fig. 5). The importance of initial soil properties may have been diminished by the ability of crop rotation to alter soil conditions through changes in root exudate and litter inputs4. Moreover, climatic factors (Fig. 4a–h) may exert a stronger influence on microbial responses to crop rotation than initial soil properties, suggesting that shifts in microbial communities are more dependent on current environmental conditions than on pre-existing soil characteristics68. However, soil texture influenced microbial responses, with crop rotation significantly altering bacterial and fungal community structures and reducing fungal species richness in fine-textured soils (Figs. 2d and 3b, d). Soils with higher clay content retain more nutrients and water, creating stable microhabitats that may intensify microbial competition and lead to changes in community structure69. Reduced niche availability may favor dominant fungal taxa and suppress the establishment of new taxa. Additionally, lower oxygen availability in fine-textured soils may inhibit certain aerobic fungi, further contributing to the observed decline in fungal species richness17.

Stronger responses in bacterial beta diversity at mid- (20–40°) and high latitudes (> 40°) (Fig. 2c) likely reflect greater contrasts in seasonal temperature and photoperiod, which can alter crop growth cycles, residue quality, and the amount of root exudates released, thereby amplifying shifts in rhizosphere resource availability and community turnover70. The greater impacts of crop rotation on bacterial and fungal community structure in the 0-180° range (Figs. 2d and 3d) were potentially linked to regions, especially in China, that are characterized by higher cropping intensity, shorter fallow periods, and more diverse crop rotations2,71. These conditions are known to increase heterogeneity in soil habitats and promote community restructuring.

Structural equation modeling further clarified indirect pathways (Fig. 4i–l). MAT indirectly increased the response of bacterial Shannon diversity by enhancing the response of soil pH (Fig. 4i), indicating that temperature-driven shifts in pH, likely through changes in mineral weathering rates, organic matter decomposition, and plant-soil interactions, can cascade to shape bacterial diversity responses72. Similarly, higher crop species richness indirectly promoted the response ratio of fungal species richness by increasing the response ratio of SOC to rotation (Fig. 4l). This SOC gain likely reflects greater residue-derived and mineral-associated organic C inputs from diverse crops, which favor saprotrophic fungi through enhanced extracellular enzyme activity and hyphal foraging, thereby expanding niche availability62,73.

Our subgroup analyses further reveal that geographic and climatic contexts strongly moderate the effects of crop transitions on soil microbial diversity (Supplementary Figs. 7–10). At high latitudes (> 40°), legume-to-non-legume and C3-to-C4 transitions enhanced bacterial Shannon diversity and species richness but reduced fungal Shannon diversity, likely because shorter growing seasons and cooler temperatures favor bacterial taxa capable of exploiting rapid nutrient pulses from legume residues, while limiting fungal colonization and turnover67,74. In contrast, at mid-latitudes (20-40°), transitions from non-AM to AM crops and from perennial to annual crops increased both bacterial and fungal diversity, potentially due to shifts in root symbiotic associations and residue quality that provide more diverse substrates and microhabitats75. Longitudinal differences were also evident: C3-to-C4 transitions had stronger effects in eastern hemispheric regions (0-180°) where crop diversity and intensive management promote higher root biomass and rhizodeposition76, whereas AM-to-non-AM transitions had stronger effects in western hemispheric regions (≤0°) likely disrupted established mycorrhizal networks, altering fungal community structure and reducing competitive exclusion63. Under arid conditions (MAP ≤ 600 mm), C3-to-C4 transitions increased bacterial and fungal diversity, consistent with the higher water-use efficiency and greater belowground carbon inputs of C4 species that enhance niche heterogeneity in water-limited soils77. In cold climates (MAT ≤ 8 °C), both AM-to-non-AM and C3-to-C4 transitions increased bacterial and fungal diversity, likely because these shifts introduce new litter and root exudates that stimulate microbial turnover in otherwise resource-limited systems78.

Soil microbial alpha diversity is linked to the crop yield benefits of crop rotation

The positive relationships between the response ratios of pH and microbial Shannon diversity and species richness (Fig. 5a, b) suggest that crop rotation may enhance microbial diversity by increasing soil pH79; higher pH levels towards neutrality have been shown to be associated with greater microbial diversity80. Crop rotation practices are known to mitigate soil acidification and alleviate nutrient limitations, thereby increasing microbial niche diversity and contributing to higher microbial richness81,82. Furthermore, the positive association between the response ratios of microbial alpha diversity and crop yield (Fig. 5c) indicates that crop rotation benefits are linked between microbial diversity and improved soil functioning, such as greater crop productivity83. Diverse microbial communities supported by crop rotation can enhance nutrient cycling, accelerate organic matter decomposition, and suppress soil-borne pathogens, ultimately supporting higher yields84.

In conclusion, our global meta-analysis demonstrates that crop rotation enhances bacterial alpha diversity but has no effect on fungal alpha diversity. It increases fungal beta diversity but not bacterial beta diversity. Moreover, crop rotation changes the structure of both bacterial and fungal communities. These effects are stronger in legume to non-legume transitions in crop rotations and with more rotational cycles and longer durations. We also find that higher microbial alpha diversity is associated with increased crop yield, suggesting a potential role of microbial diversity in enhancing productivity. These findings suggest that microbial diversity has the potential to serve as a useful indicator for optimizing soil and crop management. Region-specific optimization is essential: in high-latitude regions (> 40°), transitions from C3 to C4 crops and from legumes to non-legumes perform best; in mid-latitudes (20–40°), transitions from AM to non-AM crops and from perennial to annual crops are more effective. In humid areas (MAP > 1200 mm), rotations from legumes to non-legumes yield the greatest benefits, whereas in arid zones (MAP ≤ 600 mm), transitions from C3 to C4 crops are optimal. Under cold climates (MAT ≤ 8 °C), both AM to non-AM and C3 to C4 transitions provide the greatest advantages, while in intermediate temperature zones, more diverse crop sequences are required to sustain microbial responses. Eastern hemispheric regions (0-180° longitude) benefit most from C3 to C4 rotations, whereas western hemispheric regions (≤0° longitude) benefit more from AM to non-AM rotations. Future research should focus on microbial functional responses and crop type transitions under diverse agroecosystems to better integrate soil microbiomes into sustainable agricultural systems and maximize the benefits of crop rotation.

Although this meta-analysis includes a large number of studies, most studies were conducted in a few regions, particularly in East Asia and North America. In contrast, regions such as Africa, Central and South Asia, Oceania, Central and South America, and parts of Europe are considerably underrepresented. This imbalance in the spatial distribution of the studies may limit the generalizability of our findings, particularly in investigating the variability of climate and soil effects on the responses of microbial communities to crop rotation. Future research should aim to address these regional gaps to better assess global patterns of microbial responses to crop rotation and to understand how environmental conditions shape these responses.

Methods

Literature search

We conducted a comprehensive search for peer-reviewed publications with pairwise observations of soil microbial communities in crop rotation vs. continuous monoculture practices on a global scale. The search spanned three databases: Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com/), Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), and the China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI, http://www.cnki.net/), covering the period of January 1, 2010 to July 15, 2025. The search terms used were ‘bacterial communities OR bacterial diversity OR fungal communities OR fungal diversity OR microbial community OR biota OR bacteria OR fungi OR microbiome OR bacterial alpha OR fungal alpha OR bacterial richness OR fungal richness OR bacterial Shannon OR fungal Shannon OR 16S rRNA OR ITS OR high-throughput sequencing’ AND ‘crop rotation’. The process for selecting publications to include in this meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart85 (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Initially, 11255 publications were identified (8849 from Web of Science, 2000 from Google Scholar, and 406 from CNKI). Those publications were screened based on the title, abstract, and keywords. We included studies that specifically examined the effects of crop rotation on 8 soil microbial variables: bacterial Shannon diversity, bacterial species richness, bacterial beta diversity, bacterial community structure, fungal Shannon diversity, fungal species richness, fungal beta diversity, and fungal community structure. After this initial screening, 464 from Web of Science, 159 from Google Scholar, and 163 publications from CNKI remained in the database. These publications were then imported into EndNote 20, where duplicates and thesis-type papers were removed, leaving 704 publications for full-text screening.

We used the following criteria for further screening: (1) the reported research was based on high-throughput sequencing data, while data collected using other methods (community-level physiological profiling, plate enumeration, phospholipid fatty acid, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, and terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism) were excluded. Our study focuses on taxonomic diversity, not microbial functional metabolic diversity; (2) studies must be based on field experiments comparing soil microbial communities under crop rotation and continuous monoculture; (3) each study must include at least one crop rotation group and one continuous monoculture control, allowing paired comparisons between crop rotation and continuous monoculture treatments; and (4) studies must have at least three replicates, with mean values and standard error (SE) or standard deviation (SD) reported and directly extractable from the text, tables, or figures. Ultimately, 148 studies distributed globally (Supplementary Fig. 12) met the criteria; those studies include 2406 paired observations.

Data extraction

For each included study, we extracted data on the eight soil microbial variables described earlier. The data collected includes means, the number of replicates, and SD/SE values. When SE or SD was not reported, SD was estimated as 10% of the mean reported in a particular study86. If the publication provided variance data without specifying whether it was SD or SE, we assumed the data to be SE by default. When only SE was available, SD was calculated using the formula SE ×\(\sqrt{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\). For data reported in the figures, values were extracted using the GetData Graph Digitizer, version 2.26 (https://getdata-graph-digitizer.software.informer.com/). For data reported in box plots, means were estimated using quantile estimation87. We also collected data on soil physicochemical properties, including soil pH, soil organic C (SOC), total nitrogen (N), ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3–), available phosphorus, available potassium, and available N, and crop yield. When only soil organic matter was reported, we converted it to SOC by soil organic matter by 1.72488. Soil pH reported in the studies was measured using either water (1:1, 1:2.5, or 1:5 ratios) or calcium chloride (CaCl2, 1:2.5 ratio), and all values were standardized to a 1:2.5 water ratio89. Additionally, we recorded information on crop species used in both crop rotation and continuous monoculture treatments, rotational cycle, management practices (tillage and retention), species richness (number of crop species in the rotation system), rotation duration, mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), and soil texture. Topographical factors such as altitude and climate variables (MAT and MAP) were either obtained from the studies or extracted from the WorldClim 2 database based on the location of the study site90.

Calculation of microbial alpha diversity

We employed metrics such as Shannon diversity and species richness91 to analyze microbial alpha diversity. Microbial species richness was assessed through various indicators, including OTU/ASV counts, Chao1, and ACE, as reported across studies. We tested the differences in the response ratios among these metrics within each study using a fixed-effects model with the species richness metric as a moderator. The results showed no significant differences among the species richness estimates derived from these metrics in most observations, suggesting that using different metrics introduces minimal bias in species richness analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13). Therefore, we used a fixed-effects model to calculate the overall species richness for each study, based on 121 bacterial and 102 fungal case studies that included at least two types of alpha diversity metrics.

Crop rotation effects on microbial Shannon diversity and species richness

The effect of crop rotation on microbial parameters was estimated for each study, and the natural logarithm-transformed (ln) response ratio (RR) was calculated as:

Where the variance (Vi) was calculated as:

where \(\overline{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}}\) and \(\overline{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}\) represent the mean values of a given variable under crop rotation and continuous monoculture treatments, respectively; \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) are the corresponding standard deviations, and \({{{{\rm{n}}}}}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{n}}}}}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) are the sample sizes for the continuous monoculture and crop rotation treatments, respectively.

Crop rotation effects on microbial beta diversity and community structure

We used ordination analysis methods, including principal component analysis, redundancy analysis, correspondence analysis, principal coordinate analysis, and nonmetric multidimensional scaling92 to examine the microbial community data. In this study, we extracted sample positions on the first two axes from an ordination analysis and calculated Euclidean distances within and between treatments: within continuous monoculture (Dc), within crop rotation (Dt), and between continuous monoculture and crop rotation (Db). We then computed the means and sample sizes of these distances.

To assess the effect of crop rotation on microbial beta diversity and community structure, we calculated the response ratio for beta diversity (RRbeta) and structure (RRstructure) as follows93:

where \(\overline{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}\), \(\overline{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}}\), \(\overline{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}}\) and \(\overline{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}+{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}}\) represent the means of Dc, Dt, Db, and Dc + Dt, respectively.

Their Vi was calculated as:

where \(\overline{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{1}}\) and \(\overline{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}_{2}}\) are the means of the two components in Eqs. 3 or 4; \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1}\) and \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{2}\) are the corresponding standard deviations of the two components, and \({{{{\rm{n}}}}}_{1}\) and \({{{{\rm{n}}}}}_{2}\) are the sample sizes of the two components.

When RRbeta < 0, beta diversity decreases with crop rotation; otherwise, it increases with crop rotation. An RRstructure < 0 indicates that crop rotation does not affect microbial community structure, while RRstructure > 0 signifies changes in community structure.

Calculation of the overall response ratio

To estimate the overall response ratio, we employed a multivariate meta-analytic model using the rma.mv() function in the metafor package (version 4.8) in R, specifying StudyID as a random effect to account for heterogeneity among studies94. This approach captures systematic differences while assuming random variability in response ratios across studies. Model parameters were estimated using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) method, which provides stable overall effect estimates while controlling for inter-study heterogeneity. To obtain the confidence intervals for the response ratio, we employed the bootstrap method with 1000 resamples using the boot package (version 1.3.31) in R to calculate bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap confidence intervals95. Groups with small sample sizes (< 10) were excluded from these analyses. Funnel plots96 based on a random-effects meta-analysis model were constructed to assess potential publication bias, and Egger’s test and Rosenthal’s fail-safe number analysis were conducted to examine funnel plot asymmetry97,98. A significant Egger’s test indicated publication bias. However, if the fail-safe number exceeded 5n + 10, publication bias was considered absent91. No publication bias was found in this meta-analysis (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted using crop type transition in a rotation, management practice, the number of rotational cycles, duration, crop species richness, soil texture, latitude, longitude, MAP, and MAT as moderators in a multivariate model to examine differences in response ratio across subgroups described below. Legume transition in a rotation was categorized into three subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 15): (1) from ‘legume’ (where legume crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘non-legume’ (where non-legume crops are introduced in a rotation), (2) from ‘non-legume’ (where non-legume crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘legume’ (where legume crops are introduced in a rotation), and (3) from ‘non-legume’ (crop species in continuous monoculture) to ‘non-legume’ (crop species in crop rotation system). AM crop transition in a rotation was categorized into three subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 15): (1) from ‘AM’ (where AM crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘non-AM’ (where non-AM crops are introduced in a rotation), (2) from ‘non-AM’ (where non-AM crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘AM’ (where AM crops are introduced in a rotation), and (3) from ‘AM’ (crop species in continuous monoculture) to ‘AM’ (crop species in a crop rotation system). No “non-AM to non-AM” transition group was included because such cases were not reported in the studies compiled in our database. C3 and C4 crop transition in a rotation was categorized into three subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 15): (1) from ‘C3’ (where C3 crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘C4’ (where C4 crops are introduced in a rotation), (2) from ‘C4’ (where C4 crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘C3’ (where C3 crops are introduced in a rotation), and (3) from ‘C3’ (crop species in continuous monoculture) to ‘C3’ (crop species in a crop rotation system). No “C4 to C4” transition group was included because such cases were not reported in the studies compiled in our database. Annual and perennial crop transition in a rotation was categorized into four subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 15): (1) from ‘annual’ (where annual crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘perennial’ (where perennial crops are introduced in a rotation), (2) from ‘perennial’ (where perennial crops are continuously monocropped) to ‘annual’ (where annual crops are introduced in a rotation), (3) from ‘annual’ (crop species in continuous monoculture) to ‘annual’ (crop species in a crop rotation system), and (4) from ‘perennial’ (crop species in continuous monoculture) to ‘perennial’ (crop species in a crop rotation system). Crop growth stage refers to the stage of crop growth when soil samples were collected. The crop growth stage was divided into four sub-groups: the vegetative stage, the reproductive stage, the maturity stage, and the harvest stage. The terminologies used to describe the vegetative stage in the literature include early vegetative, eight vegetative, V6 growth stage, vigorous growth, budding stage, seedling stage, topping stage, and prosperous long-term stage. The terminologies used to describe the reproductive stage include the flowering stage, anthesis, blister stage, silking stage, tasseling to silking plant growth stage, pod setting stage, podding stage, grain filling stage, and tobacco boom stage. The maturity stage includes the maturity stage, and the harvest stage includes harvest and postharvest periods.

The soil compartment was categorized into two subgroups: rhizosphere soil and non-rhizosphere soil. Considering that some experimental sampling was conducted during different growing seasons and did not cover an entire rotational cycle, the number of rotational cycles in some cases was a non-integer. Therefore, we grouped the number of rotational cycles into five categories: rotational cycle ≤1 (≤1), 1 <rotational cycle ≤3 (1–3), 3 <rotational cycle ≤5 (3-5), 5 <rotational cycle ≤10 (5-10), and rotational cycle > 10 (> 10). Rotational duration was grouped into five categories: rotational duration ≤5 (≤5), 5 <rotational duration ≤10 (5–10), 10 <rotational duration ≤ 20 (10–20), 20 <rotational duration ≤30 (20–30), and rotational duration > 30 (> 30). Species richness was categorized into three subgroups: 2, 3, and > 3 species in a crop rotation. Soil texture was classified into three subgroups following the USDA system: (1) fine (e.g., clay, clay loam, silty clay loam, silty clay), (2) medium (e.g., silt, loam, silty loam, sandy silt loam), and (3) coarse (e.g., sandy loam, sandy clay loam, loamy sand, silty sand, sand) textures. Tillage practice was categorized into two subgroups: (1) no-tillage and (2) tillage. Crop residue retention practice was categorized into two subgroups: (1) no-retention and (2) crop residue retention. In addition, we found that V3-V4, V4, and V4-V5 were the most commonly used target regions for bacterial amplicon sequencing, while ITS1 was most frequently used for fungal sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 16). Although crop rotation effects on bacterial species richness, fungal species richness, and fungal beta diversity were significantly different across different target regions (Supplementary Fig. 16b, f, g), the small sample sizes for several regions made these differences less representative and potentially susceptible to sampling bias. Consequently, the overall variation in response ratios attributable to the target region was considered negligible. Pairwise comparisons between subgroups were performed using the estimated coefficients and their variance-covariance matrix. The difference in response ratios was calculated for each pair of subgroups, and statistical significance was determined using Z-tests. The P-values from the pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple testing, and significance letters (e.g., a, b, c) were assigned to each subgroup using the multcompView package (version 0.1.10). Subgroups with the same letters were not significantly different, while those with different letters were different (P < 0.05). The effects of crop rotation were considered significant when the 95% confidence intervals did not overlap with zero.

Factors influencing the effect of crop rotation on microbial communities

We assessed whether the response ratio (RR) was influenced by rotational cycle (C), crop species richness (R), and rotation duration (D) using a linear mixed model weighted by 1/Vi91. Ten candidate models were evaluated, with the best-fitting models selected based on the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values (Supplementary Table 1). For bacterial Shannon diversity and fungal species richness, Eq. 6 was the best-fit model. For bacterial species richness, bacterial community structure, and fungal beta diversity, Eq. 7 was the best-fit model, while Eqs. 8–10 were the best-fit models for fungal community structure, fungal Shannon diversity, and bacterial beta diversity, respectively.

To determine if soil microbial responses to crop rotation varied with environmental conditions, we incorporated individual environmental covariates (E) such as latitude, longitude, MAP, MAT, and baseline soil properties (e.g., pH, SOC, total N, NO3−, NH4+, available phosphorus, available potassium, and available nitrogen) into the models. Soil properties in the continuous monoculture treatment served as background values.

For bacterial Shannon diversity and fungal species richness, the best-fit model was:

For bacterial species richness, bacterial community structure, and fungal beta diversity, the best-fit model was:

For fungal community structure, the best-fit model was:

For fungal Shannon diversity, the best-fit model was:

For bacterial beta diversity, the best-fit model was:

Here, β represents the estimated coefficients; \({{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}_{{{{\rm{study}}}}}\) represents the study-level random effect to control for within-study autocorrelation, and ɛ denotes sampling error. All analyses were conducted using restricted maximum likelihood estimation in the lme4 package (version 1.1.37) in R99.

In addition, we employed a random forest (RF) model with a permutation-based significance test to evaluate the relative importance of environmental variables in explaining soil microbial metrics. The analysis was performed using the rfPermute package (version 2.5.4) in R. The model was built with 500 decision trees, and missing values were handled using the na.roughfix method. The importance of the variables was assessed based on the percentage increase in mean squared error (MSE), which quantifies the reduction in prediction accuracy when a variable is randomly permuted. Statistical significance was determined by generating permutation-based P-values through random shuffling of predictor variables and comparing their importance scores to the observed values. Variables with P < 0.05 were considered significant contributors to the variation in microbial diversity metrics.

Structural equation modeling was performed using the piecewiseSEM package (version 2.3.0)100 in R to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of environmental variables on microbial response ratios. The SEM framework was based on the hypothesis that MAT, rotational duration (duration), and crop species richness influence the response ratios of soil physicochemical properties (e.g., pH and SOC), which in turn impact the response ratios of microbial attributes. Due to the covariance between MAT and MAP, only MAT was included in the model. A piecewise approach was used to fit a system of linear mixed-effects models (using the lme function in the nlme package, version 3.1.164), with StudyID included as a random effect to account for study-level heterogeneity. The initial model included all hypothesized pathways, where MAT, duration, and species richness had direct paths to the response ratios of pH and SOC, which in turn indirectly affected the response ratios of microbial attributes. We refined the model iteratively by removing paths and variables; in total, seven alternative models were constructed (Supplementary Fig. 17). All models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation to ensure comparability of AIC values across candidate models. Variables included in the SEM framework were the response ratios of soil pH, SOC, and microbial attributes, along with MAT, crop rotation duration, and crop species richness. Model fit was evaluated using Fisher’s C statistics and their associated P-values to assess the overall goodness-of-fit. AIC values were used to compare competing models, with lower AIC values indicating better model fit (Supplementary Table 2). Finally, we examined relationships between the response ratios of soil microbial variables and the response ratios of soil properties and crop yield. All P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method with sequential Bonferroni correction via the p.adjust function in the vegan package (version 2.6.4)101.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available at Zenodo under (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17536604) which archives the GitHub repository (https://github.com/aijingjing1314/Crop_rotation_global_meta_analysis)102. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code and results generated in this study are available at Zenodo under (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17536604), which archives the GitHub repository (https://github.com/aijingjing1314/Crop_rotation_global_meta_analysis)102.

References

Denning, G. Sustainable intensification of agriculture: the foundation for universal food security. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 7 (2025).

Zhao, J. et al. Does crop rotation yield more in China? a meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 245, 107659 (2020).

Fan, X. & Schütze, N. Assessing crop yield and water balance in crop rotation irrigation systems: Exploring sensitivity to soil hydraulic characteristics and initial moisture conditions in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 300, 108897 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. Crop rotation increases Tibetan barley yield and soil quality on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Food 6, 151–160 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Tan, C., Wang, R., Li, J. & Wang, X. Conservation tillage rotation enhanced soil structure and soil nutrients in long-term dryland agriculture. Eur. J. Agron. 131, 126379 (2021).

Gale, W. J., Cambardella, C. A. & Bailey, T. B. Root-derived carbon and the formation and stabilization of aggregates. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64, 201–207 (2000).

Ball, B. C., Bingham, I., Rees, R. M., Watson, C. A. & Litterick, A. The role of crop rotations in determining soil structure and crop growth conditions. Can. J. Soil Sci. 85, 557–577 (2005).

Yang, X. et al. Diversifying crop rotation increases food production, reduces net greenhouse gas emissions and improves soil health. Nat. Commun. 15, 198 (2024).

Anthony, M. A., Bender, S. F. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Enumerating soil biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304663120 (2023).

Wardle, D. A. et al. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304, 1629–1633 (2004).

Van Der Heijden, M. G., Bardgett, R. D. & Van Straalen, N. M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 11, 296–310 (2008).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 7, 10541 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Rare microbial taxa as the major drivers of ecosystem multifunctionality in long-term fertilized soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 141, 107686 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Mineral-solubilizing microbial inoculant positively affects the multifunctionality of anthropogenic soils in abandoned mining areas. J. Environ. Manag. 344, 118553 (2023).

Fang, K. et al. Differential responses of soil bacteria, fungi and protists to root exudates and temperature. Microbiol. Res. 286, 127829 (2024).

Ai, C. et al. Distinct responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to changes in fertilization regime and crop rotation. Geoderma 319, 156–166 (2018).

Hartmann, M. & Six, J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 4–18 (2023).

Erktan, A., Or, D. & Scheu, S. The physical structure of soil: Determinant and consequence of trophic interactions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 148, 107876 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. Changes in soil microbial biomass, diversity, and activity with crop rotation in cropping systems: A global synthesis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 186, 104815 (2023).

Venter, Z. S., Jacobs, K. & Hawkins, H.-J. The impact of crop rotation on soil microbial diversity: A meta-analysis. Pedobiologia 59, 215–223 (2016).

Li, C. et al. The use of Biolog Eco microplates to compare the effects of sulfuric and nitric acid rain on the metabolic functions of soil microbial communities in a subtropical plantation within the Yangtze River Delta region. Catena 198, 105039 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Globally nitrogen addition alters soil microbial community structure, but has minor effects on soil microbial diversity and richness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 179, 108982 (2023).

Yang, Y. & Wu, P. Soil bacterial community varies but fungal community stabilizes along five vertical climate zones. Catena 195, 104841 (2020).

Wang, C. & Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial–fungal competition for soil resources. The ISME J. 18, wrae073 (2024).

Chen, C., Chen, H. Y. H., Chen, X. & Huang, Z. Meta-analysis shows positive effects of plant diversity on microbial biomass and respiration. Nat. Commun. 10, 1332 (2019).

Chen, X., Chen, H. Y. H. & Chang, S. X. Meta-analysis shows that plant mixtures increase soil phosphorus availability and plant productivity in diverse ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1112–1121 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. Promoting effect of plant diversity on soil microbial functionality is amplified over time. One Earth 7, 2139–2148 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Forest conversion to plantations: A meta-analysis of consequences for soil and microbial properties and functions. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5643–5656 (2021).

Philippot, L., Chenu, C., Kappler, A., Rillig, M. C. & Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 226–239 (2024).

Knight, C. G. et al. Soil microbiomes show consistent and predictable responses to extreme events. Nature 636, 690–696 (2024).

Labouyrie, M. et al. Patterns in soil microbial diversity across Europe. Nat. Commun. 14, 3311 (2023).

Steinauer, K., Chatzinotas, A. & Eisenhauer, N. Root exudate cocktails: the link between plant diversity and soil microorganisms? Ecol. Evol. 6, 7387–7396 (2016).

Sexton, J. P., Montiel, J., Shay, J. E., Stephens, M. R. & Slatyer, R. A. Evolution of ecological niche breadth. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evol. Syst. 48, 183–206 (2017).

Sieber, M., Traulsen, A., Schulenburg, H. & Douglas, A. E. On the evolutionary origins of host–microbe associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2016487118 (2021).

Berg, G. & Smalla, K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 1–13 (2009).

Mesny, F., Hacquard, S. & Thomma, B. P. Co-evolution within the plant holobiont drives host performance. EMBO Rep. 24, e57455 (2023).

Allison, S. D. & Martiny, J. B. H. Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 11512–11519 (2008).

Meyer, A. F., Lipson, D. A., Martin, A. P., Schadt, C. W. & Schmidt, S. K. Molecular and metabolic characterization of cold-tolerant alpine soil Pseudomonas sensu stricto. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 483–489 (2004).

Gao, C. et al. Co-occurrence networks reveal more complexity than community composition in resistance and resilience of microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 13, 3867 (2022).

Rousk, J. & Bååth, E. Fungal and bacterial growth in soil with plant materials of different C/N ratios. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62, 258–267 (2007).

Jiang, Y. et al. Crop rotations alter bacterial and fungal diversity in paddy soils across East Asia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 95, 250–261 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Metabolic flexibility allows bacterial habitat generalists to become dominant in a frequently disturbed ecosystem. ISME J. 15, 2986–3004 (2021).

Lanfranco, L., Fiorilli, V. & Gutjahr, C. Partner communication and role of nutrients in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. N. Phytologist 220, 1031–1046 (2018).

Chaudhary, V. B., Aguilar-Trigueros, C. A., Mansour, I. & Rillig, M. C. Fungal dispersal across spatial scales. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evol. Syst. 53, 69–85 (2022).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688 (2014).

Lu, J. et al. Rotational strip peanut/cotton intercropping improves agricultural production through modulating plant growth, root exudates, and soil microbial communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 359, 108767 (2024).

Zheng, F. et al. Positive effects of crop rotation on soil aggregation and associated organic carbon are mainly controlled by climate and initial soil carbon content: a meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 355, 108600 (2023).

Mylona, P., Pawlowski, K. & Bisseling, T. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Cell 7, 869–885 (1995).

Li, C. et al. The positive effects of mineral-solubilizing microbial inoculants on asymbiotic nitrogen fixation of abandoned mine soils are driven by keystone phylotype. Sci. Total Environ. 882, 163663 (2023).

Hibbing, M. E., Fuqua, C., Parsek, M. R. & Peterson, S. B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 15–25 (2010).

Leoni, F., Hazrati, H., Fomsgaard, I. S., Moonen, A.-C. & Kudsk, P. Determination of the effect of co-cultivation on the production and root exudation of flavonoids in four legume species using LC–MS/MS analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 9208–9219 (2021).

Qiu, X. et al. Fulvic acid promotes legume–rhizobium symbiosis by stimulating endogenous flavonoids synthesis and secretion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 6133–6142 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Flavones enrich rhizosphere Pseudomonas to enhance nitrogen utilization and secondary root growth in Populus. Nat. Commun. 16, 1461 (2025).

Li, Y., Ran, W., Zhang, R., Sun, S. & Xu, G. Facilitated legume nodulation, phosphate uptake and nitrogen transfer by arbuscular inoculation in an upland rice and mung bean intercropping system. Plant Soil 315, 285–296 (2009).

Scheublin, T. R., Ridgway, K. P., Young, J. P. W. & Heijden, M. G. A. V. D. Nonlegumes, legumes, and root nodules harbor different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6240–6246 (2004).

Pioli, S. et al. Linking plant litter microbial diversity to microhabitat conditions, environmental gradients and litter mass loss: Insights from a European study using standard litter bags. Soil Biol. Biochem. 144, 107778 (2020).

Van Der Heijden, M. G. A., de Bruin, S., Luckerhoff, L., van Logtestijn, R. S. P. & Schlaeppi, K. A widespread plant-fungal-bacterial symbiosis promotes plant biodiversity, plant nutrition and seedling recruitment. ISME J. 10, 389–399 (2015).

Ballhausen, M.-B. & de Boer, W. The sapro-rhizosphere: carbon flow from saprotrophic fungi into fungus-feeding bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 102, 14–17 (2016).

Philippot, L., Griffiths, B. S. & Langenheder, S. Microbial community resilience across ecosystems and multiple disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 85, e00026–00020 (2021).

Lupwayi, N. Z., Rice, W. A. & Clayton, G. W. Soil microbial diversity and community structure under wheat as influenced by tillage and crop rotation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30, 1733–1741 (1998).

Peralta, A. L., Sun, Y., McDaniel, M. D. & Lennon, J. T. Crop rotational diversity increases disease suppressive capacity of soil microbiomes. Ecosphere 9, e02235 (2018).

McDaniel, M. D., Tiemann, L. K. & Grandy, A. S. Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta-analysis. Ecol. Appl. 24, 560–570 (2014).