Abstract

Swarmalators - entities that combine swarming with synchronization - offer a powerful framework for understanding systems where spatial organization and internal degrees of freedom are bidirectionally coupled. Such interplay arises in diverse natural and engineered systems, from Japanese tree frogs and magnetic domain walls to robotic swarms. In contrast to an established theoretical framework, experimental realizations with tunable coupling between motion and phase remain elusive. Here, we present a controllable swarmalator system based on feedback-controlled self-propelling colloidal particles orbiting around reference points and interacting via hydrodynamic flows. We show that synchronization and spatial dynamics co-evolve, giving rise to collective states including synchronized clusters, rotating aggregates, and dispersive phases using a single control parameter. A rapid change of this parameter between regimes of attractive and repulsive phase-mediated interactions yields dynamic regimes inaccessible to systems with static interactions. Simulations incorporating squirmer and lubrication forces support our findings. We also find a new interaction channel through synchronization-dependent forces perpendicular to the connection axis between swarmalators. In general, our platform provides a versatile testbed for probing swarmalator physics but also offers novel strategies for the design of self-organizing active matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the emergence of collective behavior from local interactions is a central question in the study of complex systems. In nature, large-scale spatio-temporal patterns frequently arise without centralized coordination as seen, e.g., from the coordinated motion in animal groups1,2,3 or the synchronized flashing of fireflies4,5, chirping of crickets6 or waving of crabs7. Two foundational models—the Vicsek model, which captures spatial organization via local alignment8, and the Kuramoto model, which describes phase synchronization among coupled oscillators9—have provided key insights into such emergent phenomena. However, many real-world systems feature an inseparable interplay between spatial and oscillatory dynamics, rendering these models individually insufficient. Examples include chorusing frogs10, swimming sperm cells11, interacting magnetic colloids12, or magnetic domain walls13, where agents not only exhibit translational motion but also internal oscillations which are mutually coupled. To address this type of behavior, the concept of swarmalators (swarming oscillators), i.e., agents that exhibit both collective motion and synchronization, has been proposed14. Bidirectional coupling between these modes, where spatial proximity alters phase dynamics and phase differences modify motion, yields rich behaviors such as synchronized clustering, rotating waves, and ring-like assemblies15,16.

Although several of the above-mentioned systems exhibit phenomenological signatures of swarmalator behavior, the underlying mechanisms linking synchronization to motion in these systems are usually not clear and, accordingly, cannot be controlled. Understanding the coupling mechanisms in more detail is not only crucial to describe experimental swarmalators within existing theoretical frameworks but also important for spatio-temporal control in swarm robotics17,18,19, self-assembled micro machines20,21,22,23, and neuromorphic or reservoir computing24,25.

In this work, we present an experimental realization of a swarmalator system using feedback-controlled self-propelled colloidal particles (denoted as active Brownian particles (ABPs)) with independently tunable spatial and oscillatory dynamics. Active particles are especially well suited for realizing swarmalators, since they pose a comparably easy way of manipulating high numbers of moving agents and because the interactions between active particles have yielded basic swarmalator characteristics before12,26. Hydrodynamic interactions at high particle density mediate strong coupling between motion and phase. By tuning a single control parameter, we observe transitions between tightly synchronized, dense clusters and loosely connected, weakly synchronized states, in good agreement with numerical simulations. Our explicit understanding of the coupling mechanism enables us, for the first time, to describe and understand our system within the theoretical framework of swarmalators. Crucially, our system exhibits not only synchronization-dependent attraction, but also lateral interaction forces that drive collective rotation dynamics reminiscent of rotating biological clusters, such as those formed by bacteria or starfish embryos27,28. Furthermore, because the timescales for synchronization and clustering of the swarmalators are clearly separated, we can dynamically modulate their interaction strength to access non-equilibrium swarmalator states inaccessible under static conditions. Our results demonstrate a controllable experimental platform for swarmalators and expand the theoretical framework to include previously unexplored physical interactions.

Results

Synchronization of oscillating ABPs

To experimentally realize oscillators, we employed ABPs whose propulsion directions are individually controlled by an incident laser beam29,30,31. The ABPs we used were made from carbon-coated silica spheres (radius a = 3 μm) suspended in a near-critical water-lutidine mixture. Illumination with a focused laser heats each particle slightly above the critical temperature of the solvent, inducing local demixing and self-propulsion. Crucially, when the laser is laterally offset from the particle center, propulsion occurs opposite to the offset direction (Fig. 1a; for details, see Methods section “Experimental realization of oscillating ABPs”). To encode a phase into each ABP’s motion, we programmed them to perform quasi-circular oscillations around designated target positions. This was implemented by continuously steering each particle i in the (memorized) direction of its reference position qi using a control signal delayed by one time step δt (Fig. 1b; Methods section “Experimental realization of oscillating ABPs”). As a consequence of this control scheme, each ABP performs an orbiting motion around its reference position qi32,33 with the oscillating phase defined by \(\theta={\tan }^{-1}\left({u}_{y}/{u}_{x}\right)\) and the spatial components ux and uy of the propulsion velocity u. In our experiments, the time delay was set to δt = 0.4 s, which is identical to the time interval between recordings of the particle positions. In combination with a propulsion speed of \(\left\vert {{{\bf{u}}}}\right\vert \approx\) 2 μm/s, this yields in an average oscillation radius of R ≈ 1 μm (Fig. 1c). The initial direction of rotation is random for each particle and may spontaneously reverse due to thermal fluctuations. When operating several such oscillators with small distances \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert\) between their reference points, their oscillation becomes highly synchronized (see Supplementary video 1). Figure 1d shows experimental snapshots of synchronized oscillators with their trajectories colored according to time, where the synchronization is visible in the form of particles moving in the same directions at the same time. Such synchronization is due to hydrodynamic interactions as discussed in detail below. As a measure of synchronization σi of oscillator i with its neighbors j, we use

(see Fig. 1e). Here, 〈. . . 〉T denotes the average over time intervals T = 10 δt and Nj the number of neighbors j of oscillator i. Accordingly, σi can vary between +1 and −1, corresponding to in- and out-of-phase oscillations, respectively. Figure 1f shows an array of about 250 oscillators, with their reference positions arranged on a hexagonal lattice at a spacing of \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert\) = 12 μm. The ABPs are color-coded according to their local synchronization σi. The experiments are complemented by numerical simulations incorporating the same geometry and hydrodynamic interactions between ABPs (see Methods section “Simulation model” and SI section 5). At short inter-oscillator distances, the system exhibits large synchronized domains interspersed with only narrow domain walls of weak coherence. As the spacing \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert\) between neighboring reference positions increases, the mean synchronization across the array decreases (Fig. 1g; Supplementary video 1). This spatially dependent synchronization is a hallmark of swarmalator systems.

a An active colloid (gray, ABP) with velocity u propelled by a laser spot (green). b An ABP propelled toward a reference position (red) with a time delay δt with the use of a laser spot (green). During δt, the particle moves the distance δr, and the particle misses the reference site, leading to an oscillation around the reference position. c Trajectory (light to dark blue as a function of time) of an oscillating ABP around its reference position (red) from experiments. The ABP position is sampled every δt, with straight lines connecting successive points to depict the trajectory. d Experimental snapshot of three ABPs orbiting around their reference positions in phase. Their trajectories are colored according to time (red to blue). The ABPs are moving in roughly the same direction in each time step, visualizing the synchronization of their oscillation. e Definition of the synchronization of two oscillators i and j, \({\sigma }_{ij}={\langle \cos \left({\theta }_{i}-{\theta }_{j}\right)\rangle }_{T}\). f Experimental snapshot of an array of around 250 oscillators whose reference positions q are arranged on a hexagonal grid with a distance \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert=\) 12 μm between neighboring reference positions. The ABPs are colored according to the mean synchronization to their neighbors \({\sigma }_{i}={\langle {\sigma }_{ij}\rangle }_{j}\) (black denotes defect ABPs). For an animated version, see Supplementary video 1. g Average synchronization \({\langle {\sigma }_{ij}\rangle }_{ij}\) of oscillators as a function of their reference point distance ∣qij∣. Closed symbols: 400 oscillators on a grid as shown in (f). Open symbols: isolated doublets of oscillators. Blue lines show simulation results based on the force field shown in (j), including defect particles (see SI section 3; Fig. S7 for the synchronization without defects). Error bars and light colored areas correspond to the standard deviation. h Illustration of the experiment used to map out the forces between ABPs. One oscillating ABP with its target position (red) is placed close to a passive tracer particle, and the velocity of the tracer upass is recorded as a function of its position \(\left({r}_{\perp }| {r}_{\parallel }\right)\) in the reference frame of the velocity uact of the oscillating ABP to determine the hydrodynamic forces. i Force field experienced by a passive tracer particle close to an oscillating ABP as a function of its position \(\left({r}_{\perp }| {r}_{\parallel }\right)\) perpendicular and parallel to the ABP. j The force field of a combination of a squirmer with β = 0.25 and lubrication forces, as used in our simulations. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

To probe the underlying hydrodynamic coupling mechanism, we measured the velocity of a passive colloid placed near a moving ABP as a function of its relative position (Fig. 1h, i). The resulting strongly anisotropic velocity field and the associated force distribution indicates that hydrodynamic interactions mediate the coupling, consistent with prior observations in colloidal oscillators11,34,35. The measured flow field agrees well with a superposition of a squirmer model (with active stress parameter β = 0.25) and short-range lubrication forces (Fig. 1j; Methods section “Simulation model” and SI section 5). Incorporating this interaction model into simulations quantitatively reproduces the experimentally observed distance-dependent synchronization (Fig. 1g, snapshots in Fig. S1, for more details about the hydrodynamic synchronization see SI section 4).

Motile oscillators

In addition to phase oscillations, a characteristic feature of swarmalators is a translational degree of freedom, with mutual coupling between position and phase. Experimentally, we implement this by allowing the ABP’s reference positions qi,t to evolve dynamically in time. At each time step δt, they are updated according to

Here, di,t = Ri,t − qi,t is the displacement between the time-averaged particle position \({{{{\bf{R}}}}}_{i,t}=\frac{1}{T}{\sum }_{t-T}^{t}{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i,t}\) and the reference position qi,t and Γ is a freely adjustable coupling parameter. As a result of this rule, the reference positions acquire a time-varying velocity that depends on the displacement di,t and is therefore sensitive to the orbiting dynamics of the ABPs. The averaging window T is chosen to slightly exceed a typical oscillation period (6–8 δt) and is consistent with that used to compute the synchronization parameter σi in equation (1); moderate variations in T do not qualitatively affect the behavior of the system. To prevent phoretic clustering of the ABPs, we include a short-range repulsive interaction between neighboring reference positions as usual in swarmalator models (see Methods section “Reference position update”).

Figure 2a, b illustrate the dynamics resulting from equation (2): an ABP circles around a motile reference point, which itself moves. The mean squared displacement (MSD) provides a quantitative measure of activity36, and we use it to characterize the mobility of the swarmalator population and its dependence on the coupling parameter Γ. The MSD of isolated oscillators for different Γ values is shown in Fig. 2c. For Γ = 0, reference positions remain fixed, and the MSD shows oscillations at short times and eventually saturates. For finite values of Γ, the reference positions move due to fluctuations in the mean position Ri,t of the ABPs. This leads to an increasing value of the MSDs at large times with a Γ-dependent exponent α. Figure 2d shows that α, obtained from fits to simulated MSDs, increases from 0 to 1 with increasing \(\left\vert \Gamma \right\vert\) (for Γ > -0.2), indicating diffusive motion in the limit of large Γ. For strong negative coupling (Γ < − 0.2), reference positions outrun the ABPs orbits, inducing ballistic motion and quenching of oscillations. Because the ABPs cease to oscillate in this regime, we restrict our analysis to Γ≥ − 0.2 in the subsequent sections.

a Illustration of a motile oscillator consisting of an ABP (gray) with position ri and velocity ui oscillating around its reference position qi with phase θi. The ABP and reference position trajectories are illustrated in blue and red, respectively. According to equation (2), qi is moved in the direction of the displacement di of the ABP position Ri averaged over the interval T = 10δt. b Experimental snapshot of the motion resulting from the update scheme in (a) with Γ = − 0.1. The trajectory of the ABP is shown in light to dark blue as a function of time, and that of its reference position in red. c Mean squared displacement (MSD) of the motile oscillators from experiments with low particle densities for different values of Γ (left: Γ < 0, right: Γ > 0, median curves over particles). The dashed gray lines mark ∝ τ2 (left) and ∝ τ (right). See SI section 6 for the definition of the MSD. For Γ = 0, the MSDs show oscillations as expected for an ABP orbiting around a fixed position. When \(\left\vert \Gamma \right\vert\) increases, the exponent α of the MSD increases, showing a transition from stationary to diffusive (α = 1) and ballistic (α = 2) motion. d Long time exponent α of the MSDs against Γ obtained from fitting simulated curves. The dashed lines mark ballistic (α = 2), diffusive (α = 1) and no motion (α = 0). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Synchronization-dependent swarmalator motion

So far, we have shown that ABP oscillations synchronize as a function of the inter-oscillator distance ∣qij∣, with reference positions evolving dynamically according to equation (2). What fundamentally distinguishes swarmalators from simple motile oscillators, however, is the bidirectional coupling between phase synchronization and translational motion. In our system, this coupling arises naturally through hydrodynamic interactions, particularly pronounced at high particle densities. Figure 3a, b shows experimental and simulation snapshots for coupling values Γ = 0.2 and Γ = − 0.1, respectively. In both cases, systems were initialized with identical ABP densities and evolved for over 6000δt. For Γ = 0.2, oscillators mutually attract, leading to the emergence of dense, highly synchronized clusters. In contrast, for Γ = − 0.1, this cohesion breaks down: the system expands, the particle density decreases, and synchronization is lost (also see Supplementary video 2).

a, b Snapshots from experiment (left) and simulation (right) for Γ = 0.2 and Γ = −0.1 (see Supplementary video 2 for animated versions). The swarmalators are colored according to the synchronization averaged over their neighbors σi (black denotes defect ABPs). With Γ > 0, the swarmalators form highly synchronized clusters, while for Γ < 0 the swarmalators disperse and the synchronization is low. c Fraction fc of particles in clusters (with at least one neighbor closer than 15 μm) in experiment (black symbols) and simulation (blue line) against Γ. The error bars and light colored area correspond to the standard deviation between different runs. d A swarmalator with its reference position qi (red) and mean particle position \({{{{\bf{R}}}}}_{i}={\langle {{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}\rangle }_{T}\) (blue). d∥,ij is the displacement di = Ri − qi of the ABP from its reference position projected onto the connection vector qij = qj − qi to the reference position qj of a neighbor. e Heat map of d∥,ij averaged over particles against the synchronization σij with and distance \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert\) to neighbors. Figure S2 shows d∥,ij as a function of σij averaged over distances 8–15 μm. f Relative velocity of neighbors in a distance of 8–15 μm for different values of Γ (color of the curve) for negative (left) and positive (right) Γ. Light colored areas are the standard deviation for different experimental runs. For negative Γ we observe a repulsive interaction for high synchronization (positive relative velocity), while for positive Γ, synchronized swarmalators attract each other (negative relative velocity). In all experiments and simulations, 400 swarmalators were initialized in an area of size 400 × 280 μm, and allowed to relax until no two reference positions are within 10 μm separation using the exclusion algorithm in Methods section “Reference position update”. This gave a density of around 0.003 μm−2 at the end of the relaxation step. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Figure 3c shows that the experimentally measured fraction fc of oscillators within clusters (defined as those with at least one neighbor within ∣qij∣ ≤ 15 μm distance) increases continuously with Γ, consistent with simulations. Notably, isolated oscillators display diffusive motion for both positive and negative Γ (Fig. 2d), indicating that the observed structure formation at high densities must arise from interactions between oscillators. Considering the reference point update rule equation (2), this behavior results from the displacement di,t of oscillating ABPs from their reference positions.

A defining feature of swarmalators is that their motion depends jointly on their distance and phase synchronization. To probe this relationship, we analyzed di,t as a function of both the reference point separation ∣qij∣ and the pairwise synchronization σij. Figure 3e presents the average longitudinal displacement component d∥,ij of di,t, projected along the direction \(\hat{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}}\) to neighboring oscillators. The data reveals a clear dependence of d∥,ij on both distance ∣qij∣ and synchronization σij, confirming that motility in our system is jointly modulated by spatial proximity and synchronization—consistent with theoretical swarmalator models. Figure S2 shows a graph of d∥,ij against σij averaged over distance ∣qij∣ between 8 and 15 μm. When two oscillators i and j are negatively synchronized, the longitudinal displacement d∥,ij is negative, indicating that each ABP is, on average, displaced away from its neighbor relative to its own reference position. Conversely, for positively synchronized pairs, ABPs are displaced toward each other (i.e., d∥,ij > 0). The magnitude of this displacement decays with increasing separation between reference positions. This behavior provides a mechanistic explanation for the Γ-dependent clustering observed in Fig. 3a, b. When two oscillators are synchronized, their ABPs tend to shift toward each other, yielding positive d∥,ij values (Fig. 3d). For positive Γ, this displacement drives the reference positions closer together via equation (2), thereby promoting aggregation. In contrast, for negative Γ, the reference points move opposite to the displacement, causing synchronized oscillators to effectively repel. This interpretation is supported by direct measurements of the relative velocities between neighboring reference positions (Fig. 3f), which vary systematically with Γ, confirming the predicted dependence of effective interactions on the sign of Γ. Simulations based on the hydrodynamic interaction model detailed in Section “Synchronization of oscillating ABPs” reproduce the experimentally observed trends in both ABP displacement and relative reference-point velocity (Fig. S3). Moreover, the nature of the interaction between oscillators depends sensitively on the character of their hydrodynamic propulsion mechanism: whether they behave as pushers, pullers, or neutral squirmers (Figs. S9, S10). This underscores the critical role of the hydrodynamic flow fields generated by the orbiting ABPs34,37.

Our results show that the motile oscillators exhibit synchronization-dependent motion and a distance-dependent synchronization. Taken together, these features are hallmarks of swarmalator behavior, consistent with theoretical studies. Standard swarmalator models are characterized by two parameters, the synchronization strength K, and the spatial interaction parameter J, controlling the synchronization-dependent attraction (J > 0) or repulsion (J < 0)14,38,39. For constant, distance-independent attraction, theory predicts that swarmalators with K > 0 and J > 0 form a single, dense, synchronized cluster14. However, when attraction decays with distance—as in our system—smaller, isolated synchronized clusters are expected39,40, in agreement with our experimental observations for Γ > 0 (Fig. 3a). The regime J < 0 corresponding to Γ < 0 is rarely explored theoretically. In our experiments, it leads to dispersed, weakly synchronized swarmalators.

Swarmalator model

Beyond a simple qualitative comparison, our quantitative characterization of the interactions among swarmalators enables us to model their dynamics within the general swarmalator framework. Specifically, we represent the phase coupling between oscillating colloids as a distance-dependent, Kuramoto-like coupling term (for more details, see SI section 4). With the oscillation frequency ω0 of isolated swarmalators, the corresponding equation of motion for the phase can be written as

Here, Δθij(t) is the phase difference between neighboring swarmalators and ξi,θ(t) Gaussian, δ-correlated noise. Opposed to frequently used swarmalator models with long-range coupling14, hydrodynamic interactions results in a shorter-ranged \({\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert }^{-3}\) decay of the synchronization41.

As demonstrated in the previous section, the swarmalators in our experiments exhibit attraction or repulsion depending jointly on their relative position and phase synchronization. This interaction is mediated by the longitudinal displacement d∥,ij of each ABP along the direction of its neighbor. We find that d∥,ij can be well described by the empirical relation \({d}_{\parallel,ij}\propto | {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}{| }^{-2}\sin (\pi {\sigma }_{ij})\). With the assumption that the net displacement di,t is the superposition of displacements in the direction of neighbors, i.e., \({{{{\bf{d}}}}}_{i,t}=1/{N}_{j}{\sum }_{j}{d}_{\parallel,ij}\cdot \hat{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}}\), the motion of swarmalators can be described as

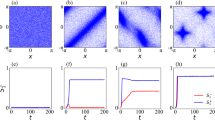

ξi,q(t) is Gaussian, δ-correlated noise, and Frep,ij adds a repulsive force for small distances (see Methods section “Reference position update”). For more details on the motivation of equation (4), see SI section 7. By integrating equations (3) and (4) with K > 0 and varying J, we recover both the synchronized clusters and the dispersed states observed in experiments and simulations (Fig. 4; Fig. S4; Supplementary video 3). The model also enables exploration of anti-synchronizing interactions (K < 0), which are not accessible in our experiments due to the synchronizing interactions of the oscillators. Hydrodynamic anti-synchronization is, however, in principle possible and has been reported in other colloidal systems34,42,43,44. For K < 0 and J > 0, the system evolves into a dispersed, weakly synchronized state. In contrast, when both synchronization and spatial interaction are repulsive (K < 0, J < 0), swarmalators self-organize into chain-like aggregates in which adjacent particles oscillate in antiphase. We can rationalize these effectively one-dimensional structures considering that denser configurations lead to frustrated phase arrangements, destabilizing synchronization, and inducing repulsion between synchronized pairs. Similar alternating phases have also been observed in numerical simulations of swarmalators with entirely different coupling and interaction mechanisms45. This suggests that the states observed in Fig. 4 are rather generic beyond the specific swarmalator realization in our study. By using synchronization, cluster size, and cluster asphericity as order parameters, the data for different J and K values separate into four distinct phases: synchronized clusters, dispersed-synchronized, chain-like anti-synchronized, and dispersed anti-synchronized states (see SI section 8).

K and J are the parameters governing the distance-dependent synchronization and synchronization-dependent attraction or repulsion, respectively (see equations (3) and (4)). a For K < 0, J > 0, the swarmalators arrange randomly without synchronization. b For K > 0, J > 0, highly synchronized clusters emerge. c For K < 0, J < 0, the swarmalators arrange in chain-like structures in which adjacent swarmalators have opposite phases. d For K > 0, J < 0, the swarmalators synchronize but repel each other. The colors denote the phases of the swarmalators as indicated in (d). For a quantitative description of the four phases, see SI Section 8. Additional snapshots for different parameter values are provided in Fig. S4, and an animated phase diagram is available in Supplementary video 3. For all J, K values, the noise was fixed with an amplitude Dθ = Dη = 0.001, where \(\langle {\xi }_{i,\theta }(t){\xi }_{j,\theta }(t^{\prime} )\rangle={D}_{\theta }\delta (t-t^{\prime} )\) and \(\langle {{{{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}}}_{i,\eta,}(t)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}}}_{j,\eta }(t^{\prime} )\rangle=d{D}_{\eta }\delta (t-t^{\prime} )\), where d is the dimensionality (here d = 2). We set ω0 = 1, integration time-step dt = 0.005/ω0, and ran the simulation for a total time of 20,000/ω0.

Outlook

Previous numerical studies of swarmalator systems have predominantly focused on quasi-static pattern formation, where steady-state configurations emerge rapidly. In contrast, our experimental system evolves on markedly longer timescales. Notably, the two principal observables—phase synchronization (σ) and the fraction of swarmalators in clusters (fc)—exhibit different relaxation dynamics (Fig. 5a). Following a change in the coupling parameter Γ, synchronization decays rapidly (within a few oscillation periods τosc), whereas structural reorganization, as measured by fc, proceeds over tens of τosc. This timescale separation gives rise to non-trivial state trajectories when Γ is modulated dynamically. In particular, switching Γ between positive and negative values generates a closed loop in the (σ, fc) state space (Fig. 5b), where the system transiently explores configurations that are inaccessible under static coupling. These intermediate states depend on the switching direction, reflecting a form of hysteresis. At higher switching rates, the system no longer equilibrates between transitions, but remains in a transient intermediate state, displaying a form of dynamic memory (Fig. 5c, d). Since this effect is a direct consequence of the asynchronous relaxation of spatial and phase degrees of freedom, we expect it to be a generic feature of swarmalators, which offers additional possibilities regarding the control of swarmalator systems46.

a The mean fraction of swarmalators in clusters 〈fc〉 relaxes slower than the mean synchronization 〈σ〉 after a switch in Γ (the light colored areas show the SEM over multiple runs). We selected Γ = −05 and Γ = 0.2 here, because these values result in the same swarmalator motility (see Fig. S11; SI section 6). b Switching back and forth between two values of Γ results in a loop in the 〈fc〉–〈σ〉 space, because the system visits different states depending on the direction of the switching. 〈σ〉 and 〈fc〉 are averaged over multiple runs. c State loop in the 〈fc〉–〈σ〉 space in simulations, for slow switching (every 400δt) of Γ (gray, as in (b)) as well as for fast switching (every 200δt) from different initial Γ (purple and orange). 〈σ〉 and 〈fc〉 are averaged over 50 runs. d Illustration of the state loop with two smaller loops (purple and orange) that are a result of faster switching in Γ from different initial values of Γ (see inset). e Heat map of the averaged normal displacement \({\langle {d}_{\perp,ij}\rangle }_{ij}\) against the synchronization σij and reference point distance \(\left\vert {{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{ij}\right\vert\) between neighboring swarmalators in experiment. f The normal (perpendicular) displacement d⊥,ij is defined as the component of the displacement di orthogonal to the direction to the neighboring reference point qij, multiplied by the sign of the angular velocity of i. g Snapshots of a rotating swarmalator cluster in simulations at different times (colors yellow to green to blue). h Mean and standard deviation of the angular velocity ω of a rotating cluster as a function of the number N of swarmalators in the system and the coupling parameter Γ in simulations In (g, h), the swarmalators were initialized on a hexagonal grid with a separation of 8 μm, the system was allowed to relax for 3000δt, and the data was collected and averaged over 30,000δt. In (a, b, c), the initial density is around 0.003 μm−2. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Besides gaining control over swarmalator systems, another important direction in swarmalator research is the search for new types of interactions that can expand the range of phenomena these models can explain47,48. The swarmalators in our experiments reveal a qualitatively new interaction channel in the form of synchronization-dependent forces, which are not limited to the axis connecting swarmalators to which theoretical models are usually restricted. We find that the hydrodynamic interactions also give rise to lateral forces, i.e., forces acting orthogonal to the connecting axis, arising from an orthogonal component of particle displacement d⊥ (Fig. 5e, f), depending on synchronization and distance. Similar to the parallel displacement, which gives rise to the synchronization-dependent attraction (see Fig. 3), this lateral displacement results in a rotational motion of swarmalators around each other. This kind of rotational motion originating from hydrodynamics is observed in multiple biological systems, like groups of starfish embryos27, but has not been reproduced in swarmalator models before. In the phenomenological model in the section “Swarmalator model”, we have omitted these lateral forces for simplicity, but this effect can be readily incorporated by adding another term to equation (4). Figure 5g, h shows a simulation snapshot of a rotating cluster of swarmalators and the size and Γ-dependent angular velocity. The rotation speed of the cluster can also be tuned by Γ, which couples the hydrodynamic interactions of the swarmalators to their motion. Importantly, the individual particles have no intrinsic chirality; instead, symmetry is broken through noise-assisted flips in rotation and synchronization mediated by hydrodynamic interactions, resulting in an emergent global rotation of the entire cluster with the same sense as its constituent swarmalators (see Fig. 5e, SI section 9). Incorporating lateral forces into swarmalator models fundamentally enriches the emergent phenomenology, enabling the formation of dynamic rotational states reminiscent of biological systems, such as vortical structures in bacterial colonies and starfish embryo aggregates27,28. Our results, therefore, expand the physical scope of swarmalator dynamics and underscore the need to include anisotropic interaction channels in future theoretical frameworks.

Methods

Experimental realization of oscillating ABPs

The Janus colloids we used as ABPs were prepared by coating commercially available silica particles (radius 3 μm) with 80 nm of carbon on one hemisphere. We dispersed these particles in a binary mixture of water and 26.8 wt% 2,6-Lutidine, which has a critical demixing temperature of 34 °C. The dispersion was placed inside a quartz glass sample cell with a height of 200 μm, which was kept at 28 °C. Focusing a laser with a wavelength of 532 nm on these particles heats up the carbon cap, which leads to anisotropic demixing of the critical mixture around them and self-phoretic motion. The propulsion speed can be controlled via the laser intensity. We controlled the motion direction by offsetting the center of the laser spot from the particle center by 2.4 μm. Using an acousto-optical deflector, we scanned the laser beam over the particles at 100 kHz, allowing us to move multiple hundreds of ABPs in parallel. To achieve continuous steering of the particles, we captured microscope images, detected the particle positions, and steered each particle towards its assigned reference position in a feedback loop at 2.5 Hz. As the particles move after the image capture at time t, the laser spots, which we apply at t + δt (δt = 0.4 s), push them in directions misaligned with the reference position. This kind of time delay and direction mismatch in the steering signal leads to a continuous oscillating motion of the ABPs around their reference points32. The ABPs used in this study do, in principle, show negative phototaxis, i.e., their uncapped side and therefore their swimming direction reorient to point down light intensity gradients with reorientation times in the order of 1 s30. However, we find that in our experiments, where we change the driving direction of each ABP with 2.5 Hz (i.e., a delay time of δt = 0.4 s), the colloids can not reorient sufficiently fast and are most of the time oriented with their carbon cap pointing in the direction orthogonal to the substrate they are moving on. As a result, the Janus colloids employed as ABPs here essentially behave like isotropic active colloids.

The relaxation time of the propulsion mechanism of the ABPs is around 0.1 s30. Since the time δt in between changes of the laser spot positions is larger than this propulsion relaxation time, the ABPs react quasi-instantaneously to changes in the driving direction.

To compensate for the mechanical instabilities of the optical setup that result in slight misalignments between the laser focus and the ABP positions, we carried out periodical recalibrations throughout all our measurements.

Simulation model

The motion of the swarmalators is described by an ABP model of self-propelled particles with hydrodynamic interactions. An ABP experiences a propulsion force fp acting along an orientation vector ei. The motion of such an ABP at position ri is governed by

where γ is the damping coefficient related to the fluid viscosity, Dt is the thermal translational diffusion coefficient of the particle, and ζi is a Gaussian random process with 〈ζi(t)〉 = 0 and \(\langle {{{{\boldsymbol{\zeta }}}}}_{i}(t){{{{\boldsymbol{\zeta }}}}}_{j}({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle={\delta }_{ij}\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime} })\). For a particle speed of u0, the required propulsion force is given by fp = γu0. The swarmalators interact hydrodynamically via the interaction FHI(ri) = γUHI(ri), due to the movement of the fluid by each swarmalator. Here, the flow field UHI(ri) is given by

where the sum is over all particles j within some cutoff distance RHI, i.e., ∣ri − rj∣ < RHI. The first term Uflow,j is the hydrodynamic force generated at the position of particle i due to the self-propulsion of the particle j, and is modeled using the squirmer flow field49,50

with r = ri − rj, r = ∣r∣ and \(\hat{{{{\bf{r}}}}}={{{\bf{r}}}}/r\). The first term decaying as 1/r2 is due to a force dipole of strength p = − 3βu0a2/4, and the second term corresponds to a source dipole of strength s = u0a3/2, where β is the squirmer parameter that measures the asymmetry in the flow field and a is the particle radius. For β > 0, we have a puller, and for β < 0, we have a pusher. For light-activated colloids, we expect no strong dipole contributions, i.e., ∣β∣ < 1.

In addition to the squirmer (far-field) interactions, we also include (near-field) lubrication forces between swarmalators51, as squirmer interactions alone are insufficient to account for the strong hydrodynamic interactions observed in the experiment (see SI section 2; Fig. S6). The flow field related to lubrication forces is given by

where \(\dot{{{{\bf{r}}}}}={\dot{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}_{i}-{\dot{{{{\bf{r}}}}}}_{j}\) is the relative velocity between particle j and i, h = r − 2a is the shortest distance between the surface of the two particles, and \(\Theta (r)=\exp (-r/{R}_{0})\) is a cutoff function whose decay radius R0 is determined by matching the data to the experiment (see SI section 2; Fig. S6).

The ABP orientation vector ei(t) at any time instant t is determined by the position of the laser spot li(t), so that ei(t) = (ri(t) − li(t))/∣ri(t) − li(t)∣, as the particle moves in the direction away from the laser spot. By choosing this update scheme that matches the experimental setup, we are able to closely replicate the experimental conditions and obtain very good agreement for the single particle motion (see SI section 1; Fig. S5). The laser spot is updated every delay time δt, with the update rule

where l0 is the distance from the particle center at which the laser is illuminated, and qi,t − ri,t is the displacement vector between the particle's reference position qi and the particle's position ri one delay time prior, i.e., at (t + δt) − δt. The system lies in the regime of low Reynolds number, so that we simulate equation (5) in the over-damped regime, i.e., m/γ ≪ δt, so that effectively

The equation of motion (5) is solved using the Velocity-Verlet integration scheme52. All the simulation parameters along with the corresponding experimental values are collected in Table 1.

Reference position update

To couple the motion of the swarmalator to its rotational oscillations, a reference-point update rule based on the swarmalators past trajectory is implemented, with reference position qi,t updated every delay time as

where \({{{{\bf{R}}}}}_{i,t}=\frac{1}{T}{\sum }_{t-T}^{t}{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i,t}\) is the average position of the swarmalator measured over the last T time steps, and Γ controls the strength of the displacement of the new reference position. Moreover, to prevent the reference positions from coming too close together—which could cause collision between particles—an exclusion algorithm between the reference positions is implemented following a Monte-Carlo procedure. Thus, every reference update qi,t is accepted with probability

where

and VLJ is the truncated Lennard-Jones potential given by

Here \({R}_{\max }\) is the minimum desired reference-point separation. The particle distribution around the reference points indicates that particles can reach distances of up to 2.0 μm from their reference positions (see Fig. S5a), thereby suggesting a minimum center-to-center separation of \({R}_{\max }=10\) μm (particle radius 3 μm) for the reference points to avoid overlapping ABPs. We therefore set ϵ/kbT = 0.2, so that while particles typically maintain a separation of \({R}_{\max }\), strong hydrodynamic forces can bring the particles closer together. Given the initialization density is around 0.003 μm−2, for weak or no clustering (Γ ≃ 0.0), the clustering coefficient is expected to remain low, as there is, on average, only one particle per box of side length 18 μm. Therefore, we choose a cutoff of 15 μm to measure clustering in the system. Additionally, in simulations, particles closer than 6.25 μm are excluded from the analysis, since lubrication forces become too strong and the behavior is uncontrolled and ill-defined.

Data availability

The experiment and simulation data that support the results of this study is available at Zenodo DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1586231053. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The simulation code and analysis scripts that were used in this study are available at Zenodo DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1586231053.

References

Buhl, J. et al. From disorder to order in marching locusts. Science 312, 1402–1406 (2006).

Tunstrøm, K. et al. Collective states, multistability and transitional behavior in schooling fish. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002915 (2013).

Bialek, W. et al. Statistical mechanics for natural flocks of birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4786–4791 (2012).

Ramírez-Ávila, G. M., Kurths, J., Depickère, S. & Deneubourg, J.-L. Modeling fireflies synchronization. In Proc. A Mathematical Modeling Approach from Nonlinear Dynamics to Complex Systems, (ed. Macau, E. E. N.) Vol. 22 131–156 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78512-7_8 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Sarfati, R., Hayes, J. C. & Peleg, O. Self-organization in natural swarms of Photinus carolinus synchronous fireflies. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg9259 (2021).

Hartbauer, M. Chorus model of the synchronizing bushcricket species Mecopoda elongata. Ecol. Model. 213, 105–118 (2008).

Aizawa, N. Synchronous waving in an ocypodid crab, Ilyoplax pusilla: analyses of response patterns to video and real crabs. Mar. Biol. 131, 523–532 (1998).

Vicsek, T., Czirók, A., Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I. & Shochet, O. Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1226–1229 (1995).

Kuramoto, Y. Self-entrainment of a population of coupled non-linear oscillators. In Proc. International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics (ed. Araki, H.) 420–422 (Heidelberg, 1975).

Aihara, I. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics in collective frog choruses examined by mathematical modeling and field observations. Sci. Rep. 4, 3891 (2014).

Yang, Y., Elgeti, J. & Gompper, G. Cooperation of sperm in two dimensions: synchronization, attraction, and aggregation through hydrodynamic interactions. Phys. Rev. E 78, 061903 (2008).

Yan, J., Bloom, M., Bae, S. C., Luijten, E. & Granick, S. Linking synchronization to self-assembly using magnetic Janus colloids. Nature 491, 578–581 (2012).

Hrabec, A. et al. Velocity enhancement by synchronization of magnetic domain walls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 227204 (2018).

O’Keeffe, K. P., Hong, H. & Strogatz, S. H. Oscillators that sync and swarm. Nat. Commun. 8, 1504 (2017).

O’Keeffe, K. et al. A solvable two-dimensional swarmalator model. Proc. R. Soc. A 480, 20240448 (2024).

Ansarinasab, S., Nazarimehr, F., Ghassemi, F., Ghosh, D. & Jafari, S. Spatial dynamics of swarmalators’ movements. Appl. Math. Comput. 468, 128508 (2024).

Barcis, A. & Bettstetter, C. Sandsbots: robots that sync and swarm. IEEE Access 8, 218752–218764 (2020).

Ceron, S., Xiao, W. & Rus, D. Reciprocal and non-reciprocal swarmalators with programmable locomotion and formations for robot swarms. In Proc. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 12233–12239 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10610540/ (IEEE, 2024).

Monaco, J. D., Hwang, G. M., Schultz, K. M. & Zhang, K. Cognitive swarming in complex environments with attractor dynamics and oscillatory computing. Biol. Cybern. 114, 269–284 (2020).

Xie, H. et al. Reconfigurable magnetic microrobot swarm: multimode transformation, locomotion, and manipulation. Sci. Robot. 4, eaav8006 (2019).

Aubret, A., Youssef, M., Sacanna, S. & Palacci, J. Targeted assembly and synchronization of self-spinning microgears. Nat. Phys. 14, 1114–1118 (2018).

Thampi, S. P., Doostmohammadi, A., Shendruk, T. N., Golestanian, R. & Yeomans, J. M. Active micromachines: microfluidics powered by mesoscale turbulence. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501854 (2016).

Martinet, Q., Aubret, A. & Palacci, J. Rotation control, interlocking, and self—positioning of active cogwheels. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2200129 (2023).

Kaspar, C., Ravoo, B. J., Van Der Wiel, W. G., Wegner, S. V. & Pernice, W. H. P. The rise of intelligent matter. Nature 594, 345–355 (2021).

Tanaka, G. et al. Recent advances in physical reservoir computing: a review. Neural Netw. 115, 100–123 (2019).

Zhang, B., Sokolov, A. & Snezhko, A. Reconfigurable emergent patterns in active chiral fluids. Nat. Commun. 11, 4401 (2020).

Tan, T. H. et al. Odd dynamics of living chiral crystals. Nature 607, 287–293 (2022).

Petroff, A. P., Wu, X.-L. & Libchaber, A. Fast-moving bacteria self-organize into active two-dimensional crystals of rotating cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 158102 (2015).

Bäuerle, T., Fischer, A., Speck, T. & Bechinger, C. Self-organization of active particles by quorum sensing rules. Nat. Commun. 9, 3232 (2018).

Lozano, C., Ten Hagen, B., Löwen, H. & Bechinger, C. Phototaxis of synthetic microswimmers in optical landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 12828 (2016).

Gomez-Solano, J. R. et al. Tuning the motility and directionality of self-propelled colloids. Sci. Rep. 7, 14891 (2017).

Chen, P.-C., Kroy, K., Cichos, F., Wang, X. & Holubec, V. Active particles with delayed attractions form quaking crystallites. Europhys. Lett. 142, 67003 (2023).

Wang, X., Chen, P.-C., Kroy, K., Holubec, V. & Cichos, F. Spontaneous vortex formation by microswimmers with retarded attractions. Nat. Commun. 14, 56 (2023).

Kotar, J., Leoni, M., Bassetti, B., Lagomarsino, M. C. & Cicuta, P. Hydrodynamic synchronization of colloidal oscillators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7669–7673 (2010).

Hu, M. et al. A hovering bubble with a spontaneous horizontal oscillation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2413880121 (2024).

Reichert, J. & Voigtmann, T. Tracer dynamics in crowded active-particle suspensions. Soft Matter 17, 10492–10504 (2021).

Theers, M., Westphal, E., Qi, K., Winkler, R. G. & Gompper, G. Clustering of microswimmers: interplay of shape and hydrodynamics. Soft Matter 14, 8590–8603 (2018).

Lizarraga, J. U. F. & De Aguiar, M. A. M. Synchronization and spatial patterns in forced swarmalators. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 30, 053112 (2020).

Sar, G. K., O’Keeffe, K. & Ghosh, D. Effects of coupling range on the dynamics of swarmalators. Phys. Rev. E 111, 024206 (2025).

Lee, H. K., Yeo, K. & Hong, H. Collective steady-state patterns of swarmalators with finite-cutoff interaction distance. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 31, 033134 (2021).

Golestanian, R., Yeomans, J. M. & Uchida, N. Hydrodynamic synchronization at low Reynolds number. Soft Matter 7, 3074–3082 (2011).

Damet, L., Cicuta, G. M., Kotar, J., Lagomarsino, M. C. & Cicuta, P. Hydrodynamically synchronized states in active colloidal arrays. Soft Matter 8, 8672 (2012).

Leptos, K. C. et al. Antiphase synchronization in a flagellar-dominance mutant of Chlamydomonas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 158101 (2013).

Maestro, A. et al. Control of synchronization in models of hydrodynamically coupled motile cilia. Commun. Phys. 1, 28 (2018).

Adorjáni, B., Libál, A., Reichhardt, C. & Reichhardt, C. J. O. Motility-induced phase separation and frustration in active matter swarmalators. Phys. Rev. E 109, 024607 (2024).

Sar, G. K., Anwar, M. S., Moriamé, M., Ghosh, D. & Carletti, T. Strategy to control synchronized dynamics in swarmalator systems. Phys. Rev. E 111, 034212 (2025).

Acharya, S., Sar, G. K. & Ghosh, D. A two-dimensional swarmalator system with Winfree-type phase coupling. Proc. R. Soc. A 481, 20250315 (2025).

Anwar, M. S., Sar, G. K., Carletti, T. & Ghosh, D. A two-dimensional swarmalator model with higher-order interactions. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 85, 1475–1499 (2025).

Blake, J. R. A spherical envelope approach to ciliary propulsion. J. Fluid Mech. 46, 199–208 (1971).

Lighthill, M. J. On the squirming motion of nearly spherical deformable bodies through liquids at very small Reynolds numbers. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 5, 109–118 (1952).

Ishikawa, T., Simmonds, M. P. & Pedley, T. J. Hydrodynamic interaction of two swimming model micro-organisms. J. Fluid Mech. 568, 119–160 (2006).

Grønbech-Jensen, N. & Farago, O. A simple and effective Verlet-type algorithm for simulating Langevin dynamics. Mol. Phys. 111, 983–991 (2013).

Heuthe, V.-L., Iyer, P., Gompper, G. & Bechinger, C. Data and Code Avalibility for “Tunable colloidal swarmalators with hydrodynamic coupling” https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15862310 (2025).

Acknowledgements

V.L.H. and C.B. acknowledge funding from the DFG Centre of Excellence 2117, Germany Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behavior (ID:422037984), and C.B. acknowledges funding by the ERC through the Adv. Grant BRONEB (101141477).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.L.H. and P.I. contributed equally to this work. V.L.H. and C.B. conceptualized the study. V.L.H. performed experiments and data analysis, and prepared the figures. P.I. and G.G. designed the simulations. P.I. performed numerical simulation and data analysis. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications Dibakar Ghosh, Nariya Uchida, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heuthe, VL., Iyer, P., Gompper, G. et al. Tunable colloidal swarmalators with hydrodynamic coupling. Nat Commun 16, 10984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66830-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66830-5