Abstract

The observed zonal sea surface temperature gradient in the tropical Pacific has strengthened over the last 150 years, but many CMIP6 models simulate a forced weakening of this gradient over the same period. This has spurred a multi-decade debate over whether models are correctly representing dynamics in the tropical Pacific and whether the observed strengthening is a forced response. We comprehensively assess all observed and modeled gradient trends of 20 years or longer from 1870-2024 across five observational datasets and 14 CMIP6 large ensembles and find that models are not able to match many long-term trends in the observed gradient, especially those that end more recently. Models that are able to match these trends do so through excessive internal variability that compensates for their gradient-weakening forced responses. We additionally find that trends in the observed gradient strengthen at an increasing rate with time, a forced response that is in contrast to the behavior of most models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the equatorial Pacific Ocean, the sea surface temperature (SST) difference between the West Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP) and the cold tongue in the east plays a particularly outsized role in global climate. The mean state of this gradient (ΔSSTwest-east) is established by the easterly trade winds that pile up warm water in the WPWP and deepen the thermocline in the west, while shoaling it in the east, where wind-driven upwelling of cold water causes the formation of the cold tongue. This mean state influences both regional and global climate. Atmospheric heating associated with deep convection over the WPWP contributes to the ascending branch of the Hadley circulation and drives the circumtropical Walker circulation, as well as Rossby waves that propagate poleward to help establish extratropical stationary waves that govern regional climates worldwide. The cold tongue in the east, as a consequence of upwelling, takes up more heat from the atmosphere than any other region on Earth1 and outgasses more CO2 than any other region2. The mean state is, however, not stable and varies on interannual to decadal timescales, with impacts on global and regional precipitation and temperature variability, air-sea CO2 fluxes3, and tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic and Pacific4,5. It has also been argued that changes in the gradient affect climate sensitivity through low-level cloud feedbacks6, and the global warming rate via changes in ocean heat uptake7.

Observations show a statistically significant strengthening in the gradient since 18808,9,10. In contrast, many models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP, most recently CMIP6) simulate a forced response that weakens the gradient. Arguments aimed at explaining why rising greenhouse gases (GHGs) should weaken the gradient rest on atmospheric and surface heat flux mechanisms. Knutson and Manabe11 and Betts12 argued that rising tropical tropospheric static stability, a consequence of rising moisture content and latent heat release in deep convection, will weaken overturning. Knutson and Manabe additionally argue that because of the nonlinearity of the Clausius–Clapeyron relation, regions with colder SST (the cold tongue) must warm more than regions with higher SST (the WPWP) to balance reduced surface longwave cooling with enhanced latent heat loss. Both effects would weaken the Walker circulation, further reducing the zonal SST gradient. Vecchi and Soden13, building on Held and Soden14, used climate models to show that, under increased radiative forcing, water vapor content in the lower troposphere increases faster with temperature than precipitation does, also requiring a reduction in Walker circulation strength that translates into a weakened equatorial Pacific zonal SST gradient. In contrast, arguments that support a strengthening gradient response to increasing GHGs9,15,16 focus on the Ocean Dynamical Thermostat mechanism17, which postulates that the shallow thermocline and upwelling in the eastern and central equatorial Pacific should restrict increases in SST in these regions, relative to the WPWP, leading to an increase in the gradient. In either case, the Bjerknes18,19 feedback works to amplify the tendency in the gradient response.

The difference between the observed gradient changes and forced response in models has spurred a debate over whether observed changes reflect internal variability, thus obscuring a forced response, or whether climate models are incorrectly representing forced gradient changes. Some studies have found that models can match observed trends, even when the forced response is a weakening gradient, via internal variability20,21. Other studies10,22,23 have argued that observed trends are at or beyond the limit of what climate models can generate, raising a question about whether the weakening forced response in models is due to model mean-state biases or misrepresentation of dynamics9,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Nevertheless, previous studies assessing relationships between observed and modeled responses in the gradient have been performed over different time periods and include different models, and it is likely that their results are sensitive to these choices.

The apparently contradictory results of earlier studies that have compared observations and models raise the important questions of whether and, more importantly, why the choice of specific time periods and models may influence the ability of models to match observed trends. To comprehensively address these questions, we compare all observed trends of 20 years or longer in ΔSSTwest-east (1870–2024) to those from 14 CMIP6 large ensembles and consider the time-varying contributions of forced responses and internal variability to the ability of models to match observed trends in ΔSSTwest-east; collectively, our approach aligns with best practices recently articulated by Simpson et al.32. Because GHG-driven forcing has increased over the historical period33, we additionally analyze the time evolution of gradient trends in models and observations to identify whether their magnitudes are changing over time and are thus consistent with a response to intensifying GHG forcing.

Results

Model ability to capture trends is sensitive to trend choice, with models failing to capture recent trends

To characterize model performance over all time periods, we compare observed trends to the full 337-member grand ensemble comprising 14 CMIP6 large ensembles (Table 1, Fig. 1a) and each large ensemble individually (Fig. 1d). To rigorously address unavoidable observational uncertainties, we include five datasets in this analysis (HadISST, COBE, COBE2, Kaplan, ERSSTv5; Table 2), which collectively represent a variety of data sources, bias corrections, and interpolation techniques. The reliability of SST reconstructions in the early, sparsely sampled periods of these datasets has been validated using a number of techniques, including initializations of ENSO hindcasts34, reconstruction of verifiable SST fields from subsampled data35,36, and use of early reconstructed SST data as a boundary condition for atmospheric general circulation models, including in the 20th Century Reanalysis product37. An earlier study also demonstrates consistent positive trends for the period 1900–2013 in the tropical Pacific zonal SST gradient for five fully interpolated observational datasets from the same lineage as those included in this study, as well as all 100 members of the uninterpolated HadSST3 ensemble that samples a range of bias correction methods and their associated uncertainties22. Our analysis additionally quantifies observational uncertainty by representing each observed trend using a confidence interval derived from a probability distribution estimated from the five SST datasets (see “Methods” section). An observed trend is considered to have been matched by a given model ensemble if the 5–95% range in modeled trend values overlaps the observed trend probability distribution by >5% (see “Methods” section). This is a notably permissive test for models that is more objective and conservative than prior work that has addressed the question of whether observed trends in ΔSSTwest-east are encompassed by the model range of variability.

a Heatmap presenting mean values of observed linear trends in ΔSSTwest-east with the trend start years on the x-axis and the trend end years on the y-axis (the primary diagonal represents trends of 20 years and the upper left corner represents the longest trend of 153 years). The dashed red line indicates the trend end year of 2000 as a visual reference point. b Heatmap as in (a). Hatching indicates observed trends within the 95% confidence interval estimated by the 337-member grand ensemble comprising 14 large ensembles from CMIP6. The black diagonal line serves as a visual reference for 100-year trends. c Heatmap presenting the percentile ranges of model trends that encompass the observed mean trends. Areas outside of the contours (>95% and <5%) indicate periods for which the observed trends lie outside of the 5–95% model range. Squares or rectangles in (a–c) indicate trend periods covered in previous studies, as listed in the legend. d Same as in (b), but hatching in each subplot indicates observed trends captured by a specific model, with shortened model name (see Table 1) and number of ensemble members indicated in the subplot title. Inset percentages indicate the proportion of all observed trends not matched by the model; panels in (d) are in descending order of the percentage of the observed trends that are matched. Squares in each model subplot indicate trend periods for which the specific model was included in the previous studies, as listed in the legend, while triangles represent trends for which the model was not included in the respective previous studies (all models in d were included in Seager et al.10).

While the grand model ensemble captures many shorter observed trends and those trends that fall earlier in the observational interval (Fig. 1b, c), it largely fails to capture longer trends that end in recent decades (as recognized in a previous commentary6, although just for the period after 1950), with observed trend values increasingly approaching the limits of the model range for trends ending in more recent years (Fig. 1c). In particular, while the ensemble captures 84% of trends ending before 2000, it captures only 55% ending after 2000, and only 9% ending after 2020. 79% of observed trends shorter than 100 years fall within the range of trends across the model ensemble; only 50% of trends longer than 100 years are captured, and of those that end after 2000, only 29% are captured. 2% of 100-year or longer trends ending after 2020 are captured. These results remain largely unchanged when comparing observed trends to a bootstrapped grand ensemble that includes 10 randomly selected ensemble members per model so that each model is equally represented; they are also robust across all leave-one-out combinations of the five observational products (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). While there is a broad spectrum of performance across the individual models – with models like MIROC 1 capturing all but 21% of the trends and others, such as INM, failing to capture 64% of trends – the percentage of trends captured across all models decreases after 2000 (Fig. 1d).

Within the context of all calculated trends, our analyses clearly demonstrate that the conclusions from previous studies are sensitive to the chosen analysis period: studies concluding that models are unable to match observations focused on trend periods that end in more recent years or span longer intervals, while studies that have placed observed trends within the range of model variability focus on trends that either end less recently or are shorter (Fig. 1). Studies in the former group additionally include a greater number of models than those in the latter, indicating that the chosen model ensembles also influence derived conclusions. Assessments over the largest possible ensembles are therefore necessary, given the wide range in model performance with regard to observed trends (Fig. 1d).

Models with oversized internal variability capture almost all trends despite their forced response

Observations and model ensembles include both internal variability and a forced response. Isolating these components is difficult in observations but straightforward in large ensembles. The forced response for each model is calculated as its ensemble mean; averaging across many simulations with common forcing removes the internal variability that is uncorrelated across ensemble members. Subtracting the forced response from all ensemble members yields an internal variability ensemble for each model in which trend ranges are centered about zero. The magnitude of this internal variability will influence the ability of each model to capture observed trends (see “Internal variability magnitude calculations” section), confirmed by the percentage of trends captured by each model (Fig. 2a), which is shown to positively and strongly relate to their estimated magnitude of internal variability (Fig. 2b).

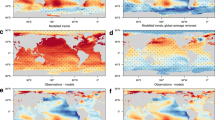

a Heatmaps presenting mean values of observed linear trends in the tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient (ΔSSTwest-east) with the trend start years on the x-axis and the trend end years on the y-axis (the primary diagonal represents trends of 20 years, and the upper left corner represents the longest trend of 153 years). Hatching indicates trends captured by the range of internal variability in each large ensemble, and inset percentages indicate the proportion of all trends that are not captured. Models are in descending order of the percentage of the observed trends that they capture. b Standard deviation of trends in observations and large ensembles for trend lengths up to 140 years. c Standard deviation distributions of detrended zonal gradient over the period 1870–2024 for models (in boxplots, orange line represents median, box represents interquartile range, whiskers represent 90% range and circles represent outliers) and five observational products (blue shaded region; note that some products do not span full time range); models with standard deviation in observational range (gray shaded region). a–c Red triangles or red lines indicate models in Group A (for which more trends are captured when the forced response is removed), blue triangles or blue lines indicate models in Group B (for which a similar number or fewer trends are captured when the forced response is moved).

The extent to which observed trends can be explained by internal variability has been characterized by the significance of observed trends relative to null hypotheses based on stationary statistics22 or relative to trends in unforced climate model control runs38. The climate model approach, however, relies on the assumption that models realistically reproduce observed internal variability; this assumption does not hold for all models at all trend lengths, with model internal variability lying above or below the observational range depending on model and trend length (Fig. 2b). It is possible that observed variability over the observational interval may represent an anomalously low period of variability. Nevertheless, proxy-based reconstructions provide insight on this point, and recent estimates of the gradient variance39,40 indicate that this variance (which, in models, positively relates to magnitude of internal variability as reflected in Fig. 2c) in the observational interval is actually high relative to the last 500–1000 years (Supplementary Fig. 3). Consequently, the 20th century appears to be a reasonable period to estimate internal variability in the observational gradient and suggests internal gradient variability in some models may be too large and thus allow more observed gradient trends to be captured for unrealistic reasons. Restricting the ensemble to only those models with internal variability similar to the observations yields an ensemble estimate that does not capture most long-term trend estimates ending after 2000 (Supplementary Fig. 4). This finding is consistent with other studies showing that recently-ending trends are not explained by internal variability and thus may be considered forced9,10,22,23.

The dominant role of ENSO in tropical Pacific SST variability, as well as models’ wide range in ENSO representation41, suggests modeled ENSO characteristics as a possible explanation for the large range of magnitudes in the modeled internal variability. These magnitudes, however, are not entirely explained by the modeled ENSO representation: ENSO variance explains just 45% of variance in gradient trends (r = 0.67, p ≪ 0.05; see Supplementary Fig. 5), implying influences from other factors.

For half of the models considered herein, the internal variability ensembles capture at least 5% more of the observed trends than their parent ensembles (compare inset percentages in Figs. 1d and 2a). We classify these models as Group A (Fig. 2 red triangles, Supplementary Table 1). Those models for which internal variability does not capture more trends than the parent ensembles are classified as Group B (Fig. 2, blue triangles, Supplementary Table 1). The implication is that the forced responses in the Group A models are toward a weakening ΔSSTwest-east, which is confirmed across almost all timescales in Fig. 3a. While previous studies have highlighted this weakening gradient in models over specific periods10,20,21,22,23, the ubiquity of the weakening trends over almost all intervals in some models (e.g., MIROC 1 and 2, EC-Earth3, MPI 1, GISS) is strikingly in contrast to observations (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, Group B models demonstrate either muted strengthening or muted weakening trends throughout, which is qualitatively closer to the observed trends. Mean gradient trends for each trend length are universally and clearly strengthening in observations, modestly strengthening for almost all models in Group B, and universally and clearly weakening in Group A models (Fig. 3b).

a Heatmaps presenting simulated linear trends in the forced component of tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient (ΔSSTwest-east) trends, separated by model group, with the trend start years on the x-axis and the trend end years on the y-axis (the primary diagonal represents trends of 20 years and the upper left corner represents the longest trend of 153 years). Per group, the top subplot shows the mean of forced trends for all large ensembles in the given group, and smaller subplots below show individual forced responses by each large ensemble. b Mean trend for each trend length for observations (black dashed line) and the range across model groups (red shaded range for Group A and blue shaded range for Group B). Note that this is calculated by taking the mean of all trends in a given time interval (along diagonals in a plots).

Across this group of large ensembles, the mean forced response for each large ensemble is negatively correlated with the mean magnitude of internal variability (r = −0.83, p ≪ 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating that models in each group capture observed trends for different reasons (see “Methods” section). Group A models have oversized internal variability (Fig. 2b) that aids their ability to capture observed gradient trends, even as their forced responses weaken the gradient. In contrast, Group B models capture some observed trends because, despite undersized internal variability, their forced responses are neutral or weakly positive. While Group A large ensembles match, on average, a greater percentage of the observed trends than Group B, this is solely because oversized internal variability overwhelms a forced response that is opposite to the observed gradient strengthening. Both groups, it should be remembered, still struggle to capture the longest trends ending in the most recent years via internal variability alone, or combined with their forced response.

Observations and models exhibit contrasting changes in trends consistent with opposing forced responses

We next examine whether trends in ΔSSTwest-east are themselves showing systematic changes over time. A positive second-order trend (see “Methods” section and dashed lines in Fig. 4b) over the observational interval indicates that ΔSSTwest-east is increasing at a growing rate or decreasing at a slowing rate; a negative value indicates that ΔSSTwest-east is decreasing at a growing rate, or increasing at a slowing rate (Supplementary Fig. 7). Radiative forcing has been increasing at a growing rate over this full analysis interval42. If zonal gradient trends are sensitive to this forcing, forced responses should grow larger over time and thus induce non-zero second-order trends in the gradient. For both models and observations, significant positive or negative second-order trends in ΔSSTwest-east, either increasing or decreasing at a growing rate, are therefore interpreted as indicative of a forced response. On the other hand, gradient changes attributable solely to internal variability should yield no long-term significant changes in ΔSSTwest-east trends. For observations, the second-order trend is positive for almost all trend lengths (with a small range of marginally insignificant trends with lengths between 74 and 78 years, all with 0.05 < p-value < 0.08), reflecting that ΔSSTwest-east is increasing at a growing rate (Fig. 4b, c). This finding is robust even if observed trends ending after 1997 are excluded to eliminate the influence of the recent decades of cool tropical Pacific SSTs following the 1997/1998 El Niño43. In contrast, five of the seven Group A models show consistent negative second-order trends across almost all trend lengths, indicating that ΔSSTwest-east is decreasing at a growing rate. The remaining two models (MPI (LR) and MPI (HR)) exhibit insignificant second-order trends for many trend lengths. Group B models show less consistent behavior, with two models (CanESM5 and ACCESS) exhibiting uniformly negative second-order trends, mirroring the evolution of the forced response observed in most Group A models, while the remaining models yield combinations of positive and negative trends.

a Heatmap presenting mean values of observed linear trends in ΔSSTwest-east with the trend start years on the x-axis and the trend end years on the y-axis (the primary diagonal represents trends of 20 years, and the upper left corner represents the longest trend of 153 years). Hatching indicates trends captured by the grand model ensemble. Diagonal lines serve as a reference for plots in (b), where red intervals indicate trends not captured by the model ensemble. b Trend values in the ΔSSTwest-east for sliding windows of three different lengths. Observational results are shown with black and red lines (red intervals indicate trends not captured; gray shading indicates observational uncertainty, defined as two standard errors above and below the trend value); results for the full model ensemble are represented by the blue shaded regions. Also shown is the second-order trend or best-fit linear regression of observed trends (dashed gray lines) and the mean of the model trend range (dashed blue lines). Inset percentages indicate the proportion of trends not captured by the model ensemble. c Second-order trends in observations (significant trends shown by black dashed line, insignificant trends shown by black dotted line) on the x-axis as a function of trend length on the y-axis. Observations show gradient strengthening trends of all lengths that are growing over time, with trends between lengths of 74 and 78 years being marginally insignificant (0.05 < p-value < 0.08). The range in the second-order trends is shown for Group A models (red shaded region) and Group B models (blue shaded region) with the 30, 80, and 130-year values, corresponding to the panels shown in (b), marked by horizontal lines. Note that models with significant values for <50% of trend lengths have been omitted from the represented ranges (MPI (LR), MPI (HR), CNRM 1, CNRM 2 are excluded).

This collection of results indicates that observations display increasingly positive trends as radiative forcing has intensified at a growing rate, while most Group A models and two Group B models show increasingly negative trends. Not only does this support the conclusion that many models exhibit forced ΔSSTwest-east changes that are opposite to those in observations, but it also indicates that ΔSSTwest-east trends in these models are diverging from observed trends with time. This divergence relates directly to changes in the mean state ΔSSTwest-east, rather than changes in ENSO. Observations demonstrate positive trends in both skewness (a measure of ENSO nonlinearity in which positive values indicate stronger or more frequent El Niño events relative to La Niña events) and variance of Niño 3 SST anomaly (SSTA; see Supplementary Fig. 8) over this period and, hence, observed El Niños are getting stronger and/or more frequent, consistent with Cai et al.44. This alone would act to weaken ΔSSTwest-east, implying that the observed strengthening must be related to other processes and is more likely a change in the mean state. Group A models, on the other hand, demonstrate increasing ENSO variance and either a reduction or very little change in skewness. This implies an increase in amplitude of both El Niño and La Niña events, which would not be reflected in consistent and growing gradient-weakening trends. Therefore, these forced trends in the models also likely represent a change in the mean state rather than a change in ENSO, though one that is in the opposite direction to observations.

Discussion

There is a growing discrepancy between the modeled trends in ΔSSTwest-east and the observed gradient strengthening. This discrepancy arises because models simulate either weakening (Group A) or only modestly strengthening (Group B) gradients in response to radiative forcing. Our results clearly demonstrate that observed gradient strengthening over periods ending in recent decades cannot be captured by models, especially by those with realistic internal variability. We also support the hypothesis that the observed strengthening is consistent with a forced response to GHGs by identifying consistently positive second-order trends in observations. Our results additionally reconcile and explain contradictory findings from previous studies. Work that has analyzed trends over longer periods of increasing radiative forcing, thus periods with higher signal-to-noise ratios, demonstrates that models do not span the observed trends because they simulate a forced response that is either muted or opposite to the observed response. In contrast, studies finding that models likely span the observed range of trends have focused on periods that either end less recently, thus excluding the most recent years with the highest level of external forcing, or are shorter and therefore more likely to be impacted by internal variability.

While a forced response that strengthens the gradient has been replicated using a simple dynamical model9,17, there are several reasons why CMIP6 models might not capture the same response. For example, Seager et al.9 attribute model biases to excessively high relative humidity and wind speeds that are too low over the eastern Pacific cold tongue, a feature related to the double Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) bias in models, although further studies have shown that thermodynamic effects alone cannot account for this warming trend45. Zhuo et al.26 also show that bias-correcting the mean SST in CESM2 yields a more La Niña-like response to rising GHGs. Alternatively, or perhaps additionally, Jiang et al.25,46 propose that models fail to connect thermocline cooling (which happens in observations and across model ensembles) to the surface through insufficient vertical shear-driven mixing and excessive thermal stratification. Kang et al.28,29 and Dong et al.27 also argue that model misrepresentation of Southern Ocean cooling and its teleconnections to the tropical Pacific may play a role, while Heede and Fedorov30 propose that the observed lack of warming in the eastern equatorial Pacific may be partially explained by aerosol masking of the CO2 effect, with models inconsistently simulating the interplay between the two effects. Identifying dynamical explanations for the forced response across models and observations is beyond the scope of this study, but the relationship that we have identified, whereby models with internal variability that is too strong also tend to have forced trends toward a weakening gradient, is an avenue worthy of future exploration for dynamical diagnoses. Kohyama et al.47 have shown that in one model with realistic ENSO nonlinearity (defined as stronger and less frequent El Niños amidst weaker but more frequent La Niñas), weakening ENSO variance under forcing drives an enhanced zonal SST gradient. Hayashi et al.48 classify models according to whether they show high or low nonlinear dynamic heating efficiency (NDHE), another measure of ENSO nonlinearity. For models with higher, and thus more realistic NDHE, increasing ENSO variance under forcing rectifies the mean state of the gradient to be more El Niño-like, showing that the arguments of Kohyama et al.47 hold for the opposite case of increasing ENSO variance. Interestingly, the Hayashi et al.48 grouping of models based on whether they demonstrate high or low NDHE closely resembles our respective classification of models into Groups A and B (see Supplementary Table 2). It is possible that this nonlinear rectification of the mean state partially explains the significant anti-correlation between forced response trends and the magnitude of internal variability in models. While this effect likely plays no role in Group B models, for which Niño 3 SSTA skewness and thus ENSO nonlinearity is underestimated (Supplementary Fig. 8), for Group A models, high and increasing ENSO variance and more realistic ENSO nonlinearity are consistent with, respectively, a higher magnitude of internal variability and a ΔSSTwest-east-weakening forced response through nonlinear rectification onto the mean state. In agreement with this hypothesis, we note that this anti-correlation is not significant for either individual model group (Supplementary Fig. 6), but is larger for Group A than Group B, implying a more direct connection between the magnitude of internal variability and the sign of forced response for these models. Given that the correlation is strongest and significant only for the full model group, it is likely that this nonlinear rectification only partially explains the relationship between forced responses and the magnitudes of internal variability. Another potential contributing effect is the role that simulated cloud feedbacks play in SST variability (and change) within models6. We additionally acknowledge the lack of consensus over whether changes in ENSO variance rectify the mean state, or vice versa49,50,51.

Heede et al.52,53 argue that the observed gradient strengthening is a transient forced ocean dynamical thermostat response, by which increasing radiative forcing is currently strengthening both cold upwelling in the central-eastern equatorial Pacific and the zonal Pacific Walker circulation. According to their arguments, this response is expected to diminish in the coming decades due to other forced ocean-atmosphere responses, including thermodynamically driven Walker cell weakening and warming of subtropical surface waters that feed the thermocline. While it is possible that the representation of gradient trends by CMIP6 models may align with observations in the future, these models are currently being used to project regional responses to climate change. As such, their growing disagreement with the current physical reality is concerning5. Moreover, if observed changes are characteristic of a forced strengthening gradient, there is a strong case to be made that this disagreement arises because models are unable to capture the dynamics of this forced response over the past decades.

By examining trends in the ΔSSTwest-east over all start and end dates and interval lengths between 1870 and 2024, using many large ensembles and observational SST datasets, this study robustly demonstrates that models rarely reproduce observed trends that end in recent decades, especially those that are over the longest intervals. Furthermore, we have shown that models most capable of matching observed trends do so via excessive internal variability, despite forced responses toward weakening gradients. We also identify a growing rate of strengthening of the observed gradient that is consistent with a response to increasing radiative forcing. This forced response is not reproduced by any of the analyzed models, which exhibit either a growing rate of gradient weakening or a muted and inconsistent forced response. Notably, a strengthening zonal gradient that is becoming increasingly apparent in observations is consistent with the identification of an emerging Pacific Climate Change Pattern in surface atmosphere and upper ocean fields, that is distinct from natural variability, as presented by Jiang et al.54. Collectively, our findings add to the evidence that the strengthening zonal gradient in the equatorial Pacific includes a forced response that CMIP6 models fail to reproduce. As the magnitude of radiative forcing continues to increase, the inability of models to correctly represent the response to this forcing is likely to continue to widen the gap between real and projected climate changes in multiple regions worldwide.

Methods

CMIP6 large ensembles

To compare observed gradient trends to those simulated by CMIP6 large ensembles (also referred to hereafter as ‘models’), this study uses the surface temperature (‘ts’) variable of 14 large ensembles within the CMIP6 archive (337 ensemble members in total). Ensembles were selected on the basis of having ten or more historical runs and at least one SSP245 scenario realization, all with uniform initial conditions, physics, and forcing schemes. The selected models are: CanESM5, MIROC6, MIROC-ES2L, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, GISS-E2-1-G, IPSL-CM6A-LR, CNRM-CM6-1, CNRM-ESM2-1, CESM2, INM-CM5-0, UKESM1-0-LL, ACCESS-ESM1-5, and EC-Earth3. To encompass our entire period of interest, we concatenate historical runs with SSP245 scenario runs. For historical runs for which scenario runs with identical variant labels are available (i.e., runs that are continuous from historical to future scenarios), runs are concatenated as such; in cases for which matching pairs cannot be identified, historical runs are randomly paired with one of the scenario runs available from the same model.

Observed SST datasets

We use five observational SST analysis products: the Hadley Center Global Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature dataset (HadISST v1.155, available at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Extended Reconstructed SST V5 (ERSSTv556, available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html), COBE Sea Surface Temperature (COBE57, available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe.html), COBE-SST 2 and Sea Ice (COBE235, available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe2.html), Kaplan Extended SST V3 (Kaplan36, available at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.KAPLAN/.EXTENDED/.v3/.ssta/). HadISST incorporates both in situ and satellite data into analysis; COBE2 and ERSSTv5 rely primarily on in situ observations, supplementing with satellite data to reconstruct SST variability in data-sparse regions; COBE and Kaplan rely solely on in situ measurements. All data products use Optimal Interpolation to fill coverage gaps; Kaplan additionally applies Optimal Smoothing. Because each dataset includes errors and uncertainties, the inclusion of all five provides a sample of the observational uncertainty and, therefore, a fairer test of the ability of models to capture observed trends.

SST zonal gradient trends

We define the Pacific zonal gradient as the difference in area-weighted SST anomaly (SSTA) between a previously defined western tropical Pacific box (140°–170°E, 3°S–3°N) and eastern tropical Pacific box (170°–90°W, 3°S–3°N)10. Positive values indicate a relatively warmer western Pacific and a relatively cooler eastern Pacific, while negative values indicate a reduced SSTA difference between the two regions. We calculate SSTA by removing the mean monthly SST from each grid cell over the entire period defined for this study (1870–2024). This was performed for each observational dataset and each ensemble member of the 14 large ensembles.

On both observational and model gradient time series, we perform a linear least-squares regression using monthly data for all 9180 trends longer than 20 years between years 1870 and 2024. Trends were calculated in sliding windows, incremented annually according to the calendar year. Slopes are computed in units of K per decade.

Calculating the combined observed trend

Combined error-weighted average trend values are calculated for each start-end date combination across all five observational datasets as follows58:

where xwav is the weighted average trend, xi is the trend value from each observational dataset, and σi is the standard error associated with the linear trend. Uncertainties in the weighted average trend (‘combined uncertainty’) were calculated as

The standard error is a representation of the uncertainty of the linear least-squares regression fit arising from variance in the underlying data. In this case, this variance includes both the variability of the physical system as well as potential data errors and uncertainties. For each of these datasets, the ratio between the standard error in the slope and the gradient variance is very similar, indicating that the proportion of the standard slope error attributable to physical variability versus data errors is likely comparable across all datasets. Furthermore, the standard errors for each trend across all datasets are similar, justifying the choice of the slope standard error as a metric of observational uncertainty.

Identification of trends captured by models

To identify the observed trends that are ‘captured’ by models, the following test is applied: if a trend value within the 5–95% range of the model realizations has a greater than 5% likelihood of falling within the range of observational trend uncertainty, that trend is considered captured by the model. The uncertainty range of the combined observed trend is defined by a probability density function with a mean of the weighted average observed trend and a standard deviation of the combined uncertainty. Traditional parametric ‘difference of means’ tests are not applicable in this context because assessment of each trend requires the comparison of a parametric (observational) and a non-parametric (model) distribution. As such, by treating the model distribution, with its discrete points, as a known range and the observations as a probability distribution, this test enables the calculation of the likelihood that these two distributions overlap significantly (i.e., p-value > 5%).

Isolation of model forced response and internal variability

For each model, the forced response in the gradient is calculated as the mean gradient value across all ensemble members because averaging across many simulations with common forcing removes the internal variability that is uncorrelated across ensemble members. Trends in this mean gradient are then calculated as described in the “SST zonal gradient trends” section and are considered to be the forced trends in the gradient. To calculate the internal variability of each model, the forced response in the gradient is removed from each ensemble member’s gradient time series. Trends in this gradient are then calculated for each ensemble member to create an internal variability ensemble for each model.

Internal variability magnitude calculations

Calculating the true magnitude of internal variability in observations is complicated by the fact that only one realization of the real world is available. As shown in one of the results of this study, long-term changes in trends appear to be consistent with a forced response. As such, by removing the long-term linear trend in observed trend values for each trend length, we aim to remove the influence of external forcing and, to the degree possible, isolate the internal variability in the observational gradient. We then estimate the magnitude of this internal variability by calculating the standard deviation of the observational internal variability trends for each trend length. While it is possible to isolate the internal variability in models by removing the forced response, in order to directly compare a measure of internal variability in models to that in observations, we instead apply the same metric used to calculate the observed internal variability to each ensemble member in every model. For each trend length, we linearly detrend each ensemble member’s trend values and then calculate the combined detrended standard deviation across the full ensemble for each model. The use of intermember standard deviation to quantify internal variability magnitude has also been used in other studies (e.g., Olonscheck et al.20; Wang et al.59). The additional step of detrending at each trend length allows for a comparison to be made between modeled and observed internal variability. Note that this method for estimating the magnitude of internal variability is specific to Fig. 2b.

Correlation between forced response and internal variability

The Pearson correlation coefficient between models’ forced response and internal variability is calculated based on the mean forced response and mean magnitude of internal variability for each ensemble. Mean forced response is calculated as the average of all 9180 trends, while mean internal variability magnitude is calculated as the average internal variability magnitude (as described in the “Internal variability magnitude calculations” section) across all trend lengths.

Second-order linear trends

To compare long-term changes in trends between models and observations, we calculate second-order trends. For observations, all trends are calculated for a given trend length using a sliding analysis window; the weighted least-squares regression of these trends is then calculated, with weights of 1/σwav2. Only significant trends are included (p-value < 0.05). For forced responses in the model ensembles, a least-squares regression is applied to all trends for each trend length for each model, with only significant values included.

ENSO analysis

Niño 3 SSTA is calculated as the area-weighted mean SSTA in the Niño 3 region (150°W–90°W, 5°S–5°N). Skewness and standard deviation are calculated on the detrended annual mean model and observational data. Annual mean values are calculated with the year being defined from May to April to better represent the ENSO cycle. Model SSTA is detrended by subtracting the ensemble mean SSTA, while observations are detrended by subtracting the 60-year low-pass filtered SSTA. For models, ensemble mean values are shown, where the mean across the ensemble is calculated after skewness and standard deviation have been calculated for each ensemble member.

Data availability

The observational datasets used to reproduce the results of this paper are publicly available at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.KAPLAN/.EXTENDED/.v3/.ssta/data.nc (Kaplan), https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html (HadISST), https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html (ERSSTv5), https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe.html (COBE), and https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cobe2.html (COBE2). CMIP6 data are publicly available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search. The Cook and Cane39 SST reconstruction is publicly available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/paleo/treering/reconstructions/cook2024/cook2024-R15-ENSO-Rec-1500-2000.txt. The Steiger et al.40 PHYDA equatorial Pacific zonal SST gradient reconstruction is publicly available at https://zenodo.org/records/1198817.

Code availability

The analysis scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.3708170.v1.

References

Valdivieso, M. et al. An assessment of air–sea heat fluxes from ocean and coupled reanalyses. Clim. Dyn. 49, 983–1008 (2017).

Takahashi, T. et al. Global sea–air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 1601–1622 (2002).

McKinley, G. A., Follows, M. J. & Marshall, J. Mechanisms of air-sea CO2 flux variability in the equatorial Pacific and the North Atlantic. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18, 2003GB002179 (2004).

Sarachik, E. S. & Cane, M. A. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation Phenomenon (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Near-term tropical cyclone risk and coupled Earth system model biases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2209631120 (2023).

Rugenstein, M. et al. Connecting the SST pattern problem and the hot model problem. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105488 (2023).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Karnauskas, K. B., Seager, R., Kaplan, A., Kushnir, Y. & Cane, M. A. Observed strengthening of the zonal sea surface temperature gradient across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. J. Clim. 22, 4316–4321 (2009).

Seager, R. et al. Strengthening tropical Pacific zonal sea surface temperature gradient consistent with rising greenhouse gases. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 517–522 (2019).

Seager, R., Henderson, N. & Cane, M. Persistent discrepancies between observed and modeled trends in the tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Clim. 35, 4571–4584 (2022).

Knutson, T. R. & Manabe, S. Time-mean response over the tropical Pacific to increased C02 in a coupled ocean-atmosphere model. J. Clim. 8, 2181–2199 (1995).

Betts, A. K. Climate-convection feedbacks: some further issues. Clim. Chang. 39, 35–38 (1998).

Vecchi, G. A. & Soden, B. J. Global warming and the weakening of the tropical circulation. J. Clim. 20, 4316–4340 (2007).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Cane, M. A. et al. Twentieth-century sea surface temperature trends. Science 275, 957–960 (1997).

Seager, R. & Murtugudde, R. Ocean dynamics, thermocline adjustment, and regulation of tropical SST. J. Clim. 10, 521–534 (1997).

Clement, A. C., Seager, R., Cane, M. A. & Zebiak, S. E. An ocean dynamical thermostat. J. Clim. 9, 2190–2196 (1996).

Bjerknes, J. A possible response of the atmospheric Hadley circulation to equatorial anomalies of ocean temperature. Tellus 18, 820–829 (1966).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Olonscheck, D., Rugenstein, M. & Marotzke, J. Broad consistency between observed and simulated trends in sea surface temperature patterns. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086773 (2020).

Watanabe, M., Dufresne, J.-L., Kosaka, Y., Mauritsen, T. & Tatebe, H. Enhanced warming constrained by past trends in equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature gradient. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 33–37 (2021).

Coats, S. & Karnauskas, K. B. Are simulated and observed twentieth century tropical pacific sea surface temperature trends significant relative to internal variability? Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9928–9937 (2017).

Wills, R. C. J., Dong, Y., Proistosecu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Systematic climate model biases in the large-scale patterns of recent sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100011 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. On the future zonal contrasts of equatorial Pacific climate: perspectives from observations, simulations, and theories. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 82 (2022).

Jiang, F., Seager, R., Cane, M. A., Karamperidou, C. & Brizuela, N. G. Subsurface Cooling and Sea Surface Temperature Pattern Formation Over the Equatorial Pacific. JGR Oceans 130, e2024JC022222 (2025).

Zhuo, J.-Y. et al. A more La Niña-like response to radiative forcing after flux adjustment in CESM2. J. Clim. 38, 1037–1050 (2024).

Dong, Y., Armour, K. C., Battisti, D. S. & Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. Two-way teleconnections between the southern ocean and the tropical Pacific via a dynamic feedback. J. Clim. 35, 6267–6282 (2022).

Kang, S. M., Shin, Y., Kim, H., Xie, S.-P. & Hu, S. Disentangling the mechanisms of equatorial Pacific climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf5059 (2023).

Kang, S. M. et al. Global impacts of recent Southern Ocean cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300881120 (2023).

Heede, U. K. & Fedorov, A. V. Eastern equatorial Pacific warming delayed by aerosols and thermostat response to CO2 increase. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 696–703 (2021).

Watanabe, M. et al. Possible shift in controls of the tropical Pacific surface warming pattern. Nature 630, 315–324 (2024).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Confronting Earth system model trends with observations. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt8035 (2025).

Meehl, G. A. et al. in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis (eds Solomon, S. et al.) 747–845 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007).

Chen, D., Cane, M. A., Kaplan, A., Zebiak, S. E. & Huang, D. Predictability of El Niño over the past 148 years. Nature 428, 733–736 (2004).

Hirahara, S., Ishii, M. & Fukuda, Y. Centennial-scale sea surface temperature analysis and its uncertainty. J. Clim. 27, 57–75 (2014).

Kaplan, A. et al. Analyses of global sea surface temperature 1856–1991. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 18567–18589 (1998).

Compo, G. P. et al. The twentieth century reanalysis project. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 1–28 (2011).

Bordbar, M. H., Martin, T., Latif, M. & Park, W. Role of internal variability in recent decadal to multidecadal tropical Pacific climate changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 4246–4255 (2017).

Cook, E. R. & Cane, M. A. Tree rings reveal ENSO in the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109759 (2024).

Steiger, N. J., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, E. R. & Cook, B. I. A reconstruction of global hydroclimate and dynamical variables over the Common Era. Sci. Data 5, 180086 (2018).

Bayr, T. et al. Error compensation of ENSO atmospheric feedbacks in climate models and its influence on simulated ENSO dynamics. Clim. Dyn. 53, 155–172 (2019).

Miller, R. L. et al. CMIP6 historical simulations (1850–2014) with GISS-E2.1. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13, e2019MS002034 (2021).

Seager, R. et al. Ocean-forcing of cool season precipitation drives ongoing and future decadal drought in southwestern North America. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 141 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Adam, O., Shourky Wolff, M., Garfinkel, C. I. & Byrne, M. P. Increased uncertainty in projections of precipitation and evaporation due to wet-get-wetter/dry-get-drier biases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL106365 (2023).

Jiang, F., Seager, R. & Cane, M. A. Historical subsurface cooling in the tropical Pacific and its dynamics. J. Clim. 37, 5925–5938 (2024).

Kohyama, T., Hartmann, D. L. & Battisti, D. S. La Niña–like mean-state response to global warming and potential oceanic roles. J. Clim. 30, 4207–4225 (2017).

Hayashi, M., Jin, F.-F. & Stuecker, M. F. Dynamics for El Niño-La Niña asymmetry constrain equatorial-Pacific warming pattern. Nat. Commun. 11, 4230 (2020).

Fedorov, A. V. & Philander, S. G. Is El Niño changing? Science 288, 1997–2002 (2000).

Jin, F., An, S., Timmermann, A. & Zhao, J. Strong El Niño events and nonlinear dynamical heating. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1120 (2003).

Sun, D. & Zhang, T. A regulatory effect of ENSO on the time-mean thermal stratification of the equatorial upper ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, 2005GL025296 (2006).

Heede, U. K., Fedorov, A. V. & Burls, N. J. Time scales and mechanisms for the tropical pacific response to global warming: a tug of war between the ocean thermostat and weaker walker. J. Clim. 33, 6101–6118 (2020).

Heede, U. K., Fedorov, A. V. & Burls, N. J. A stronger versus weaker Walker: understanding model differences in fast and slow tropical Pacific responses to global warming. Clim. Dyn. 57, 2505–2522 (2021).

Jiang, F., Seager, R. & Cane, M. A. A climate change signal in the tropical Pacific emerges from decadal variability. Nat. Commun. 15, 8291 (2024).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 2002JD002670 (2003).

Huang, B. et al. NOAA extended reconstructed sea surface temperature (ERSST), version 5. NOAA Natl. Centers Environ. Inf. https://doi.org/10.7289/V5T72FNM (2017).

Ishii, M., Shouji, A., Sugimoto, S. & Matsumoto, T. Objective analyses of sea-surface temperature and marine meteorological variables for the 20th century using ICOADS and the Kobe Collection. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 865–879 (2005).

Taylor, J. R. An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements (University Science Books, Sausalito, CA, 1997).

Wang, Z., Dong, L., Song, F., Zhou, T. & Chen, X. Uncertainty in the past and future changes of tropical Pacific SST zonal gradient: internal variability versus model spread. J. Clim. 37, 1465–1480 (2024).

Hajima, T. et al. MIROC MIROC-ES2L model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.5602 (2019).

Tachiiri, K. et al. IPCC DDC: MIROC MIROC-ES2L model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 61354109163 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPMIMILS245 (2023).

Tatebe, H. & Watanabe, M. MIROC MIROC6 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.5603 (2018).

Shiogama, H., Abe, M. & Tatebe, H. IPCC DDC: MIROC MIROC6 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 226446044578 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPMIMIS245 (2023).

EC-Earth Consortium (EC-Earth). EC-Earth-Consortium EC-Earth3 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.4700 (2019).

EC-Earth Consortium (EC-Earth). IPCC DDC: EC-Earth-Consortium EC-Earth3 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 954182681733 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPEEE3S245 (2023).

Jungclaus, J. et al. MPI-M MPI-ESM1.2-HR model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.6594 (2019).

Schupfner, M. et al. IPCC DDC: DKRZ MPI-ESM1.2-HR model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 253312723735 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPDKME2S245 (2023).

NASA Goddard Institute For Space Studies (NASA/GISS). NASA-GISS GISS-E2.1G model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.7127 (2018).

NASA Goddard Institute For Space Studies (NASA/GISS). IPCC DDC: NASA-GISS GISS-E2.1G model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 429413367635 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPGIGEGS245 (2023).

Danabasoglu, G. NCAR CESM2 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.7627 (2019).

Danabasoglu, G. IPCC DDC: NCAR CESM2 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 176648172973 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPNRCESS245 (2023).

Wieners, K.-H. et al. MPI-M MPI-ESM1.2-LR model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.6595 (2019).

Wieners, K.-H. et al. IPCC DDC: MPI-M MPI-ESM1.2-LR model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 261343177426 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPMXML2S245 (2023).

Volodin, E. et al. INM INM-CM5-0 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.5070 (2019).

Volodin, E. et al. IPCC DDC: INM INM-CM5-0 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 44269271848 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPINIC0S245 (2023).

Voldoire, A. CMIP6 simulations of the CNRM-CERFACS based on CNRM-CM6-1 model for CMIP experiment historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.4066 (2018).

Voldoire, A. IPCC DDC: CNRM-CERFACS CNRM-CM6-1 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 279966763395 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPCECC1S245 (2023).

Boucher, O. et al. IPSL IPSL-CM6A-LR model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.5195 (2018).

Boucher, O. et al. IPCC DDC: IPSL IPSL-CM6A-LR model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 399922142248 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPIPICLS245 (2023).

Seferian, R. CNRM-CERFACS CNRM-ESM2-1 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.4068 (2018).

Voldoire, A. IPCC DDC: CNRM-CERFACS CNRM-ESM2-1 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 227670899787 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPCECE1S245 (2023).

Tang, Y. et al. MOHC UKESM1.0-LL model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.6113 (2019).

Good, P. et al. IPCC DDC: MOHC UKESM1.0-LL model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 428986973716 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPMOU0S245 (2023).

Swart, N. C. et al. CCCma CanESM5 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.3610 (2019).

Swart, N. C. et al. IPCC DDC: CCCma CanESM5 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 657574315652 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPCCCES245 (2023).

Ziehn, T. et al. CSIRO ACCESS-ESM1.5 model output prepared for CMIP6 CMIP historical. Earth Syst. Grid Fed. https://doi.org/10.22033/ESGF/CMIP6.4272 (2019).

Ziehn, T. et al. IPCC DDC: CSIRO ACCESS-ESM1.5 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 322109789319 Bytes World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/AR6.C6SPCSAES245 (2023).

Acknowledgements

H.B., R.S., and J.S. were supported by the US NSF through award AGS-2101214. R.S. was additionally supported by NSF award OCE-2219829. We thank Ibuki Sugiura for her valuable contributions in the early stages of project conceptualization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.B., R.S., and J.S. Methodology: H.B., R.S., and J.S. Investigation: H.B. Visualization: H.B. Supervision: R.S. and J.S. Writing—original draft: H.B. Writing—review & editing: R.S. and J.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Masaki Toda and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Byrne, H., Seager, R. & Smerdon, J.E. CMIP6 models cannot capture long-term forced changes in the tropical Pacific sea surface temperature gradient. Nat Commun 17, 142 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66839-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66839-w