Abstract

In hydrogen-bonded materials and biosystems, microscopic proton ordering, which is strongly influenced by the quantum nature of protons, underpins diverse macroscopic phenomena, including phase transitions, chemical reactions, biomolecular processes and collective proton transfer. Yet resolving proton arrangements and characterizing their quantum behavior at the atomic scale remain challenging due to the small size of protons and the lack of effective approaches. Here, we exploit bond-resolved atomic force microscopy and spectroscopy (BR-AFM/AFS) to probe signatures of proton ordering in surface-confined benzimidazole (BI) assemblies. By performing BR-AFS along the apparent H-bond between proton donor and acceptor nitrogen atoms, we extract information consistent with H-bonding directionality and signatures compatible with quantum proton delocalization. We observe anomalous rotational-symmetry breaking in the proton order of the cyclic hexamers, arising from the coexistence of both localized and quantum-delocalized protons. The chirality of a single hexamer can be reversibly switched by altering its adsorption registry combined with collective transfer of six protons. Path-integral molecular dynamics calculations unravel that nuclear quantum effects promote proton delocalization and concomitant reduction of donor-acceptor distance. Our findings enable atomic-level detection of complex proton orders, engineering proton-based quantum states, and elucidation of long-range proton transfer mechanisms in molecular architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen bonds are profoundly influenced by nuclear quantum effects (NQEs) owing to the low mass of the proton1,2,3. To fully understand many fundamental biological and chemical processes mediated by H-bonds–such as enzymatic reactions4,5,6, signaling7, and the dynamics of water8–the quantum nature of protons must be considered. In two- or three-dimensional molecular crystals, where intermolecular H-bonding motifs create specific proton arrangements9,10,11,12, NQEs can significantly impact proton ordering, thereby dramatically altering structural and physical properties. For example, quantum delocalization drives proton order-disorder transition and H-bond symmetrization in high-pressure phases of ice13, and promotes high-temperature superconductivity in sulphur hydrides14. Recent high-resolution scanning probe studies of small molecules on atomically flat surfaces in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) have provided preliminary evidences for proton sharing, including water-hydroxyl complexes on Cu(110)15, long-range-ordered Zundel cations on Au(111) and Pt(111)16, and H-bonded one-dimensional 2,5-diamino-1,4-benzoquinonediimines chains on Au(111)17. However, these observations have so far relied primarily on imaging, while complementary spectroscopic evidence remains limited.

Another challenge is to extend the investigation of proton ordering and NQEs from small interfacial molecular systems, such as water18, to those with heavier skeletons10. In this regard, the imidazole ring represents an ideal candidate. Capable of both donating and accepting a proton, it serves as an important building block in biological systems, facilitating low-barrier H-bonds (LBHB)4,5. Moreover, single-component crystals of imidazole derivatives can achieve above-room-temperature ferroelectricity, with electric polarization switchable via cooperative proton transfer through the H-bonds (N − H···N ⇄ N···H − N)19.

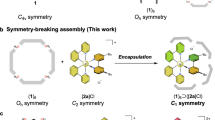

In this work, we introduce an approach based on bond-resolved atomic force microscopy and spectroscopy (BR-AFM/AFS) for determining H-bond directionality in benzimidazole (BI) architectures on Ag(111). We reveal the conventional unidirectional H-bonding in linear BI chains, while in cyclic hexamers, we unravel ground-state proton orders featuring coexisting localized and quantum-delocalized protons (states 1 and 4 in Fig. 1). We further demonstrate that a single hexamer can interconvert reversibly among four proton-ordering states (Fig. 1). Changing the adsorption registry suppresses proton delocalization, whereas a collective six-proton transfer not only reverses the chirality of the cyclic H-bonds but also restores the non-classical H-bonds (Fig. 1). Our work highlights the important role of NQEs and the local environment on proton ordering, as well as correlated nature of many-body proton transfer20,21 within interfacial molecular architectures.

The −8.5°-L (state 1) and +8.5°-R (state 4) configurations are the two ground states, each hosting cyclic H-bonds with coexisting localized and quantum-delocalized protons. Rotating (denoted as Rot) the ground-state hexamer by ±17° changes the adsorption registry and yields the intermediate +8.5°-L (state 2) and −8.5°-R (state 3) configurations, in which proton delocalization is suppressed. A collective six-proton transfer (CPT) converts 2–4 or 3–1, reversing the cyclic H-bonding directionality and restoring the delocalized protons. For clarity, only the imidazole ring of BI is shown: N (blue) and H (red). R and L denote the chirality of the cyclic H-bonds. PIMD calculations reveal asymmetric proton sharing in non-classical H-bonds (blue shading), contrasted with localized protons in classical H-bonds (pink/orange shading).

Results

Probing H-bond directionality via force spectroscopy

The five-membered imidazole ring in the BI molecule contains two nitrogen atoms. For clarity, we refer to the pyridine-like nitrogen as “N site” and the pyrrole-like nitrogen as “NH site” (see Fig. 2a). Upon adsorption on Ag(111), the prochiral BI molecule transforms into a chiral entity, denoted as either the l- or r-enantiomer (Fig. 2a). At submonolayer coverage, BI molecules self-assemble into various structures, including extended molecular chains, closed loops and six-membered clusters (Fig. 2b), driven by attractive intermolecular N − H···N hydrogen bonding provided by the imidazole ring22. The chains grow along the \(\left\langle 11\bar{2}\right\rangle\) directions of Ag(111) (Fig. 2b), indicating a preferred epitaxy. To specify the N − H···N bond directionality in this system, it is essential to distinguish between the N and NH sites in the imidazole ring. Fig. 2c depicts a constant-current STM image of a single BI molecule recorded with a CO-functionalized tungsten tip (see also Supplementary Fig. 3), permitting submolecular resolution23. Note that a single-lobe feature appears on both sides of the molecule, adjacent to the N and the NH sites, with the latter being more prominent (cf. the molecular structure in Fig. 2c and the detailed discussion below). Using frequency shift (Δf) imaging in constant-height mode24, both pentagonal and hexagonal rings are clearly resolved (Fig. 2d), with slight expansion and distortion due to CO bending at the tip apex25,26. However, the N and NH sites cannot be differentiated.

a Ball-and-stick models of BI molecules. r and l denote the NH site on the right and left side, respectively. Color code: C, grey; H, white; N, blue. b Overview STM image of BI assemblies on Ag(111). Setpoint: Us = 100 mV, It = 10 pA. c, d STM (c) (setpoint: Us = 100 mV, It = 10 pA) and AFM (d) images of a single BI molecule on Ag(111) measured with a CO-tip. e Line-FS along the dashed arrow in (d), extracted Fmin(d) curve (left projection; orange) and two F(z) curves recorded at peak positions (right projection). f Bond-resolved AFM image of a BI chain. g Zoomed-in image of (f) with scaled molecular models superimposed. h Line-FS along the dashed arrow in (g), extracted Fmin(d) curve (left projection; orange) and two F(z) curves recorded at peak positions (right projection). All the AFM images were recorded at a tip height of z = −30 pm relative to the STM setpoint (Us = 20 mV, It = 5 pA) above the bare surface. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To distinguish between pyridine and pyrrole-like nitrogen atoms, we performed site-specific force-distance spectroscopy [FS or F(z)], which records ∆f changes as a function of tip-sample distance27,28,29,30. Fig. 2e depicts a set of F(z) spectra recorded along a path that traverses two corner sites of the imidazole ring (see dashed arrow in Fig. 2d). The left projection in Fig. 2e displays the Fmin values extracted from each F(z) spectrum as a function of the lateral tip position d along the path. The Fmin(d) curve exhibits an asymmetric M-shape, with two peaks of unequal height separated by ≈ 4.6 Å, matching the apparent distance between two nitrogen sites in the imidazole ring (cf. Fig. 2d). The right projection in Fig. 2e shows two F(z) curves extracted at the maxima of the two peaks in the Fmin(d) curve (cf. blue and red points in left projection in Fig. 2e), with Fmin(N) − Fmin(NH) ≈ 7 pN (cf. Supplementary Fig. 4). FS provides contrast consistent with differences between N and NH sites mainly through atomic-scale electrostatic interactions with the CO tip, reflecting the distinct electron density distributions of these two sites, as elaborated below. Notably, our results are consistent with prior FS characterization of naphthalocyanine molecule, which distinguishes the inner nitrogen sites with and without hydrogen31.

Next, we applied line-FS to determine the H-bonding directionality in an open chain (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 5). Although the bright intermolecular contrast in BR-AFM image cannot be directly interpreted as an H-bond32,33,34, the probe-particle (pp) model reveals that the “bright line” arises from the relaxation of the probe particle (CO molecule) above the potential landscape formed by two neighboring atoms26. When the sharp line coincides with an H-bond, it traces the path between the proton donor and acceptor atoms. Accordingly, FS measurements were performed along the bright connections between neighboring imidazole rings (Fig. 2f, g), crossing two adjacent nitrogen atomic sites. Along the apparent H-bonds, characteristic M-shaped Fmin(d) curves are also obtained with the first peak consistently higher than the second (left projection in Fig. 2h; Supplementary Fig. 6d). Two F(z) curves recorded at two peak positions show a clear difference at Fmin (right projection in Fig. 2h), with Fmin(N) − Fmin(NH) ≈ 4 pN. Therefore, the H-bond directionality in the BI chain adopts a left-pointing N···H − N configuration (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 6). This assignment is corroborated by two additional observations: (i) the appearance of a dark depression at the right-side termination, attributed to a pyridine-like N atom35 (white arrow in Fig. 2f); (ii) the apparent length of the single (C − N) bond being greater than that of the double (C = N) bond (Supplementary Fig. 7)25. Although the experimentally measured apparent distance between intra- or intermolecular N and NH sites are systematically larger or smaller than the DFT-calculated values (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 6e) due to CO-tip bending, this does not hinder the accurate discrimination between the two sites.

Anomalous symmetry breaking in BI-hexamer proton order

Next, we focus on self-assembled BI hexamers, which are homochiral owing to their H-bonding motif. These hexamers adopt four different adsorption configurations (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9), denoted as ∓8.5°-L/R or ∓40°-L/R. The rotation angle (∓8.5° or ∓40°) is defined between the high-symmetry axes of the hexamer and the close-packed directions of the Ag(111) surface (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 8), while the clockwise (+) or counterclockwise (–) turn is associated with handedness (R/L) of the cyclic H-bonds in the hexamer36,37. Fig. 3a, b show a BR-AFM image and the DFT-optimized adsorption geometry of the −8.5°-L hexamer. The center of the hexamer occupies an hcp hollow site (cf. Supplementary Fig. 10), giving rise to threefold rotational symmetry: the benzene ring in L1, L3 and L5 sits over a hollow site, whereas in L2, L4 and L6 it sits on a top site. Notably, the +8.5°-R also adopts an hcp-centered geometry with C3 symmetry (Supplementary Fig. 10b), and DFT calculations show that both enantiomorphic configurations are planar on the surface with nearly identical adsorption energies (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a–c Bond-resolved AFM image (a), DFT-optimized structure (b), and proton-order-resolved AFM image (c) of the –8.5°–L hexamer on Ag(111). d, f Simulated AFM images at z’ = 4.40 Å (d) and z’ = 5.10 Å (f). e, Electrostatic potential map at 1.52 Å above the topmost atoms corresponding to (b). g Experimentally obtained Fmin(d) curves (black solid dots) for six H-bonds, ordered clockwise (dashed arrow in a). Red and blue curves are site-dependent F(z) spectra taken at two peak positions. h Concatenated simulated Δfmin(d) profiles along six H-bonds, corresponding to colored arrows in (d). i, j Zoom-in of a representative Δfmin(d) profile showing two maxima (i), and simulated ∆f(z) spectra at the N and NH sites extracted at those maxima (j). Experimental AFM images were recorded at z = −30 pm (a) and z = 25 pm (c) relative to the STM setpoint (Us = 20 mV, It = 5 pA) above Ag(111). Orange shading in (g) marks H-bonds assigned as non-classical. AFM imaging heights (experimental and simulated) in (a, c, d, f) are indicated by dashed lines in the corresponding force-spectroscopy plots (g, j). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine the cyclic H-bonding directionality in the hexamer, we first analyzed bond-order contrast in experimentally obtained BR-AFM images but found no systematic trend (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). By contrast, applying the same analysis to AFM images simulated with different effective tip charge38 reveals a clear bond-order contrast consistent with the expected chiral motif (Supplementary Fig. 14), and we clarify this discrepancy below. To gain further insight, we performed line-FS characterizations (see also Supplementary Figs. 15–18). Fig. 3g depicts six datasets, measured consecutively for the six H-bonds in the −8.5°-L following a clockwise sequence (red arrow in Fig. 3a). Each panel displays a characteristic M-shaped Fmin(d) curve along with two F(z) spectra recorded at two peak positions (red and blue points and curves in Fig. 3g). An overall trend can be discerned: along the measurement path, the second peak in the M-shaped Fmin(d) curves is predominantly higher than the first. Therefore, the Fmin(d) curves show features compatible with a clockwise N − H···N bonding scheme in the −8.5°-L (Fig. 3b). For comparison, line-FS measurements were also conducted for the +8.5°-R hexamer, revealing a counterclockwise N − H···N bonding scheme (Supplementary Fig. 15d, h).

To further support our interpretation, we calculated electrostatic potential (ESP) of the −8.5°-L hexamer on Ag(111) using DFT and simulated both AFM images and site-dependent FS with the PPAFM code39 and a negatively charged CO tip40,41. The ESP map reveals that the N site has a more negative potential than the NH site (Fig. 3e). In particular, the simulated M-shaped ∆fmin(d) curve with unequal peak heights for all six H-bonds (Fig. 3h,i), together with the corresponding ∆f(z) curves at the N and NH sites (Fig. 3j), reproduces the experimental results (Fig. 3g), thus validating the line-FS approach for determining H-bond directionality.

A closer inspection of Fig. 3g shows that, for H-bonds L3-L4 and L4-L5 in the −8.5°-L hexamer, the two Fmin(d) peaks have nearly equal heights: |Fmin(N) − Fmin(NH)| ≲ 1 pN, (Supplementary Figs. 15i and 17c; Supplementary Note 2). For such H-bonds, the extracted F(z) curves at peak positions overlap near their minima (orange-highlighted plots in Fig. 3g). At a tip-sample distance corresponding to Fmin, the AFM image of −8.5˚-L shows a single-lobe feature corresponding to the N-site in the imidazole ring on the right-hand side of the BI molecule for H-bonds L1-L2, L5-L6 and L6-L1. By contrast, a double-lobe feature is clearly observed in L3-L4 and L4-L5 and faintly in L2-L3 (Fig. 3c). Similar patterns are also observed for the +8.5˚-R hexamer (Supplementary Fig. 15f). However, the equal-peak M-shaped Fmin(d) curves and the corresponding double-lobe AFM features deviate from the DFT-based PPAFM simulations (Fig. 3f, h). Such observations imply that the donor and acceptor nitrogen sites become indistinguishable, reminiscent of both symmetric H-bonds15,42 and LBHBs4,5, and suggest the possibility of proton delocalization within the H-bond. AFM imaging near Fmin, together with line-FS characterization on multiple as-grown ∓8.5°-L/R and ∓40°-L/R hexamers, consistently reveals anomalous rotational-symmetry breaking of proton order (Supplementary Figs. 19-21). This contrasts with the nearly C6-symmetric, flower-like pattern from the PPAFM simulation (Fig. 3f) and with the computed M-shaped ∆fmin(d) profiles with unequal peak heights expected for equivalent H-bonds (Fig. 3h). Moreover, neither small biases (Supplementary Fig. 22) nor a CO-terminated tip41 perturb the broken-symmetry proton order, although it is not discernible by tunneling spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 23). In different hexamers, one, two or three of the six H-bonds exhibit signatures of proton delocalization. Across a total of 56 cases, the mean fraction of non-classical H-bonds is ≈40% (see Supplementary Note 3).

Unravelling proton delocalization via PIMD simulations

To examine the influence of NQEs on proton ordering in the BI hexamer, we performed ab initio molecular dynamics simulations using both conventional and path-integral schemes (AIMD/PIMD)43 at 50 K. Compared to AIMD, which considers nuclei as classical particles, PIMD treats both electrons and nuclei quantum mechanically, providing a more accurate description of proton behaviours17,44. To simplify the system, we modelled a gas-phase BI dimer (L3-L4) with its initial geometry extracted from the optimized −8.5°-L-hexamer/Ag(111) (Supplementary. Fig. 24a; see also “Methods”). Fig. 4a depicts the probability distributions of a proton between two nitrogen atoms–N (donor) and N′ (acceptor)–as a function of reaction coordinates RC derived from PIMD and AIMD calculations. The RC is defined as

where RNH and RN′H are the instantaneous NH and N′H distances, respectively (see inset in Fig. 4a). The PIMD calculations reveal that the proton is delocalized between two nitrogen atoms, in stark contrast to the AIMD results, where the proton remains covalently bonded to the donor atom (Fig. 4a,b). Free energy is calculated from

where P(RC) is the probability distribution of RC and kB is the Boltzmann constant. Under full quantum description, the free energy profile features a double-well valley at RC ≈ -0.18 and 0.16, separated by a small free energy barrier of ≈ 6 meV at RC = 0 (Fig. 4b). This may considerably enhance proton tunneling, leading to the occurrence of proton delocalization (see a snapshot from the PIMD simulations in Fig. 4a). Conversely, the AIMD-calculated free-energy profile displays a single valley at RC ≈ -0.18, indicating that thermally activated proton transfer is rare. This is consistent with the relatively large classical reaction energy barrier (≈ 32 meV) computed for proton transfer in the H-bond of the BI dimer using the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method with zero-point energy (ZPE) correction (Supplementary Fig. 24b).

a, b Probability distributions (a) and free-energy profiles (b) for the proton along the reaction coordinates in the BI dimer at 50 K, obtained from PIMD (red lines) and AIMD (blue lines) simulations. Inset: representative PIMD configuration with a delocalized proton (red spheres). c Time traces of NN′ distances and RC of BI dimer obtained from PIMD simulations. The variation of the average NN′ distance (red line) and RC with time and their quantum fluctuations (grey shading) are shown in (c). Orange shading marks intervals with RC ≈ 0 accompanied by shortened NN’. d Representative LAMMPS-PIMD snapshots of the −8.5°-L-hexamer on Ag(111) surface showing coexisting localized and delocalized protons (red spheres). e, f Proton probability distributions and free-energy profiles along RC in L3-L4 (e) and L4-L5 (f) within the hexamer at 5 K. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further analyzed the temporal variations of NN′ distance and RC (Fig. 4c) to reveal the connection between NN′-distance distribution and proton delocalization. At the quantum mechanical level with PIMD, the averaged NN′ distance decreases moderately from ≈ 2.7 to ≈ 2.6 Å, accompanied by the occurrence of proton delocalization, where the averaged RC approaches zero (orange-highlighted region in Fig. 4c). For AIMD calculations, the NN′ distance oscillates around an equilibrium value of ≈ 2.7 Å (upper plot in Supplementary Fig. 24c). Intriguingly, the time-dependent RC evolution obtained from quantum simulations reveals a change in the sign (lower plot in Fig. 4c), corresponding to a proton tunneling process from N to N′, which is absent in the AIMD calculations (lower plot in Supplementary Fig. 24c). Within the timescale (10−13 s) of the quantum simulation, proton tunneling from N to N′ only occurs once due to the low free energy barrier (≈ 6 meV), which corresponds to a transfer rate on the scale of 1012 s−1 based on the quantum transition state theory method applicable to water tetramer45. Accordingly, we infer a rapid back-and-forth dynamic behavior of delocalized protons, which underlies the nearly overlapped F(z) spectra recorded at two nitrogen sites of the non-classical H-bonds (orange-highlighted plots in Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 15). Since line-FS integrates over time, it reflects the time-averaged proton positions.

Notably, in BR-AFM images non-classical H-bonds appear shorter than classical ones (Supplementary Fig. 25), consistent with PIMD findings (Fig. 4c) and prior theoretical predictions44. However, such geometrical effects cannot be reproduced at the DFT level (Supplementary Fig. 26). To capture the coexistence of localized and delocalized protons in cyclic H-bonds (Fig. 3c, g), we performed PIMD simulations of a constrained BI-hexamer/Ag(111) surface at 5 K using the reaction force field46 (Methods; Supplementary Fig. 27). Starting from the DFT-relaxed −8.5°-L hexamer (Fig. 3b), the N···N distances of L3–L4 and L4–L5 were shortened slightly relative to other N···N spacings (Fig. 4d; and Supplementary Fig. 27a). The resulting proton probability distributions and free-energy profiles for L3–L4 and L4–L5 are presented in Fig. 4e,f. First, proton delocalization occurs only in shortened H-bonds (≈ 2.4 Å)42, whereas for N···N ≳ 2.8 Å the proton remains localized at the donor atom (Fig. 4d). Second, L3–L4 and L4–L5 display unequal proton probability distributions and corresponding asymmetric free-energy profiles. In the gas-phase dimer (Fig. 4a), removing one proton yields two mirror-symmetric configurations that interconvert via proton tunneling, producing a symmetric probability distribution. In the hexamer, however, L5 retains a localized proton on its left side, whereas L3 is proton-deficient on its right side. Proton tunneling could therefore transiently generate a benzimidazolium cation at L5 and a radical BI species at L3. Although such fleeting states are not resolved in time-averaged FS measurements, they may account for the suppressed proton delocalization in L3–L4 and L4–L5.

Controllable transitions among four proton-ordering states

We demonstrate that a single BI hexamer can reversibly interconvert among four distinct proton-ordering states: two ground states containing non-classical H-bonds and two intermediate states in which classical H-bonds prevail (Figs. 1, 5). At liquid nitrogen temperature, STM scans induce conformational change of hexamers between two equivalent adsorption configurations (Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Movie 1). This implies that a single hexamer can switch between two enantiomorphic structures when the chirality of the cyclic H-bonds is reversed through collective transfer of all six protons (cf. Supplementary Fig. 11). To verify this assumption, we performed tip manipulations on hexamers at 5 K (Supplementary Figs. 28, 29; and Supplementary Movie 2). Fig. 5a presents an AFM image of a − 8.5˚-L hexamer in its ground state (state 1; cf. Fig. 3c). After tip manipulation, the hexamer rotated 17° around its center (Fig. 5b). Line-FS analysis of this configuration (+8.5°-L) reveals that the clockwise H-bonding directionality persists, while non-classical H-bonds are significantly suppressed in this intermediate state 2, as evidenced by the downshift of the ∆Fmin values for L3-L4 and L4-L5 relative to state 1 (shaded area in Fig. 5h). Intriguingly, +8.5°-L can be transformed into +8.5°-R (state 4) via multiple proton transfer induced by inelastic tunneling electrons47. The CO-tip was positioned above the NH site of a BI molecule (green dot in Fig. 5b), and the bias voltage was ramped from zero to 0.5 V while keeping the feedback-loop open. A sudden jump in the ∆f(V) curves was observed at 0.36 V (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 30), matching the NH stretching mode energy (Supplementary Fig. 31). This operation re-established the non-classical H-bonds, yielding +8.5°-R ground state (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 32b, f). The reverse transition (state 4 to state 1) follows a similar pathway (Figs. 1, 5d–f; and Supplementary Figs. 33, 34), proceeding via intermediate state 3. Importantly, multiple-proton transfer could not be triggered in states 1 and 4, indicating that ground-state proton ordering of hexamer is interlocked with its adsorption configuration.

a–f Proton-order-resolved AFM images (top) and simplified chemical-structure models (bottom; N, blue; H, red) for the four states. All AFM images were recorded at z = 25 pm relative to the STM setpoint (Us = 20 mV, It = 5 pA) above Ag(111). Non-classical H-bonds (|∆Fmin | ≲ 1 pN) are shaded blue to emphasize asymmetric proton sharing. GS: ground state; InS: intermediate state; Rot: rotation; CPT: collective proton transfer. g Typical ∆f(V) curves recorded at the green markers in (b, e), indicating the occurrence of CPT. Arrows indicate bias sweeping direction. h, i Comparison of ∆Fmin = Fmin(NH) − Fmin(N) values for six H-bonds in states 1 vs. 2 (h), and 3 vs. 4 (i). Orange shading highlights suppression of delocalized protons. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To rationalize why classical H-bonds dominate in states 2 and 3 (Fig. 5h, i), we performed additional DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 35). We found that, in states 2 and 3, three pyridine-like nitrogen atoms in the hexamer occupy top sites on Ag(111) (highlighted in yellow in Supplementary Figs. 32c, 33c), whereas in states 1 and 4, all pyridine-like nitrogen atoms reside at the hollow sites (Supplementary Fig. 11). This indicates a stronger interaction between the proton-acceptor nitrogen atom and the substrate in the intermediate state configuration, which is corroborated by electron-density-difference analysis,

where ρ represents electron density of each component. Δρ cross sections along the H-bond (∓8.5°-L) indicate greater electron-density redistribution beneath the top-site proton-acceptor nitrogen atom (N′) than that beneath its hollow-site counterpart (cf. dashed rectangles in Supplementary Fig. 35b, d). Strong electronic hybridization causes a pronounced tilting of the N′ atom’s σ orbital (lone pair) out of the in-plane geometry (a black arrow in Supplementary Fig. 35d), thus disfavoring proton tunneling.

Discussion

We probed substrate dependence by depositing BI on other single-crystal surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 36a–d). Notably, on the more inert Au(111), BI hexamers also form and display a similar proton-ordering pattern with broken rotational symmetry, supporting the generality of this phenomenon (Supplementary Fig. 36f–i). Furthermore, to assess isotope effects, we synthesized deuterated BI molecules (D-BI) and carried out a series of experiments. Deuteration was verified by reduced switching voltages for collective proton transfer in D-BI hexamers relative to H-BI counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 37), consistent with the lower N-D stretching energy47. Line-FS measurements of cyclic H-bonds in ∓8.5°-L/R hexamers further reveal both asymmetric and symmetric M-shaped Fmin(d) curves (Supplementary Figs. 38, 39). DFT-based PIMD calculations of a D-BI dimer yields a deuteron probability distribution and free-energy profile comparable to those of H-BI dimer (Supplementary Fig. 40). Our results are in accordance with earlier studies revealing deuteron delocalization in Zundel cations (D5O2+) under both surface-adsorbed and gas-phase UHV conditions16,48, as well as in LBHB between amino groups49.

In summary, we introduced a line-FS based method that provides evidence consistent with H-bonding directionality in BI chains and the chirality of cyclic hexamers. We observe anomalous rotational-symmetry breaking in proton ordering within cyclic H-bonds, stemming from the coexistence of localized and delocalized protons. PIMD calculations show that the quantum tunneling and fluctuation drives this delocalization. We further demonstrate reversible chirality switching of a single hexamer by changing its adsorption registry coupled with collective proton transfer. These results provide microscopic insight into how NQEs and local environment govern proton ordering in surface-confined cyclic H-bonds, thereby paving the way toward engineering exotic material phases and quantum states50. The cooperative motion of protons also offers great opportunities for designing interfacial 2D organic ferroelectrics11.

Methods

Sample preparation

Ag(111)/mica substrates were employed and the Ag(111) surface was prepared by repeated Ar+ ion sputtering at 0.9 keV and annealing at ≈700 K for several cycles. Benzimidazole (Sigma Aldrich, 98%) was fully degassed and then evaporated at around 320 K onto the substrate maintained at room temperature. At low coverage, the molecules favored the formation of hexamers, whereas high coverage led to the formation of extended chains and closed rings.

Synthesis of 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-1-d

The synthesis of 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-1-d (deuterated at the N1 position) involves exchanging the N–H proton with deuterium using a suitable deuterium source. To achieve selective N1-deuteration of unsubstituted benzimidazole, we employed an acid/base-controlled, divergent deuteration protocol specific to N-unsubstituted imidazoles, using trifluoroacetic acid-d (TFA-d) as the deuterium source (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2)51. This method enables selective labeling at the N1 position without affecting the aromatic rings or the C2 position. The reaction was carried out under acidic conditions with CF₃CO₂D (60 equivalents) at 130 °C for 12 h. The extent of deuteration was confirmed by ¹H NMR spectroscopy, where the disappearance of the N–H proton signal indicated successful incorporation of deuterium (for details see Supplementary Note 1).

STM/AFM measurements

The scanning tunneling microscopy and atomic force microscopy (STM/AFM) measurements were conducted in a Polar STM/AFM system (Scienta Omicron) at 4.8 K with a base pressure of better than 2 × 10−10 mbar. The qPlus sensor used had a resonance frequency (f0) of 24.5 kHz, a spring constant (k0) of ≈1800 N m−1, and a quality factor (Q) greater than 150000 at 4.8 K. An etched tungsten (W) tip was used in the experiment, which was pulsed and poked into the metal surface to ensure a clean, symmetric, and atomically sharp front edge. Oscillation amplitudes of 0.5 Å were employed. All STM and AFM images were recorded in constant-current and constant-height modes, respectively, using a CO-terminated tip unless otherwise stated. The bias voltage was applied to the sample with respect to the tip. AFM images were acquired at a bias voltage of 0 V. The scanning height (z) of AFM images is relative to STM setpoint on the bare Ag(111) surface, with z > 0 indicating an increase in the tip-sample distance, and z < 0 indicating a decrease in the tip-sample distance. Image processing was carried out by using Nanotec WSxM software52.

Statistics and reproducibility

All STM and AFM measurements were repeated on multiple samples and with different tips, yielding consistent results. The representative images shown in the main text were selected from reproducible datasets obtained under similar experimental conditions.

BR-AFS measurements

Force spectroscopies [FS or F(z)] were measured with Us = 0 V. To perform line-FS on an H-bond, a BR-AFM image was first obtained for the H-bond. Following this, FS measurements were conducted along the bright line between the two molecules. Finally, another bond-resolved AFM image was recorded after line-FS to ensure no noticeable drift had occurred. Short-range F(z) were obtained by subtracting long-range FS recorded on Ag(111) and converting ∆f(z) to F(z) via the Sader-Jarvis method53.

Rotation and collective proton transfer via tip manipulation

Before manipulation, the tip was cleaned/sharpened by repeated pulsing/ poking on Ag(111). For an as-grown hexamer (∓8.5°-L/R), the tip was placed over one molecule at Us = 10 mV, It = 10 pA; feedback was then disabled and the tip lowered until It ≈ 20 nA to enlarge tip-molecule interaction. Lateral motion at 1 nm s-1 rotated the hexamer into an intermediate state (±8.5°-L/R), which preserves cyclic H-bond chirality. We then imaged the hexamer, positioned the tip at an NH site, and ramped the bias until an abrupt ∆f change at |Us | ≈ 0.35 V indicating collective proton transfer; a follow-up AFM image confirmed the ground state (±8.5°-R/L). The protocol was repeated > 30 times with high reproducibility.

DFT calculations and AIMD simulations

DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)54,55, with the projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials56,57. The exchange-correlation effect was described by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional58 within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). The modelled adsorption structure consists of a BI hexamer adsorbed on the three-layer Ag(111) substrate of a 7√3×12 unit cell and the thickness of the vacuum slab is larger than 11 Å. During structural optimization, the substrate was fixed, and the cutoff energy of the plane wave basis set was set to 520 eV. Due to the large scale of the absorption model, the structural optimizations were considered converged when the maximum force on each atom was less than 0.01 eV Å−1. Only the Γ point in the Brillouin zone was sampled. DFT-D3 method with Becke-Johnson damping function59 was used to account for the van der Waals interaction for the surface adsorption.

In ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) based on the classical nuclear approximation and the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) calculations, the cutoff energy was set to 600 eV and the degrees of freedom in z-direction were fixed. The maximum force on each atom was less than 0.005 eV Å−1 after the CI-NEB calculation had reached convergence. The AIMD simulations were performed for 1935 fs with a time step of 0.1935 fs at a temperature of 50 K. The canonical (NVT) ensemble was sampled using the Langevin thermostat60,61.

Ab-initio PIMD calculation

Ab-initio based PIMD simulations employing 8 beads were performed using the i-PI software62, combined with the time-dependent ab initio package (TDAP)63,64,65 implemented in Quantum Espresso66,67. The SG15 Optimized Norm-Conserving Vanderbilt (ONCV) pseudopotentials68,69 was used to describe the core electrons. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional58 was adopted to describe the exchange-correlation effect. The kinetic energy cutoff for wavefunctions and for charge densities were set to 100 Ry and 400 Ry, respectively. The PIMD simulations were performed for 385 fs with a time step of 0.1935 fs at 50 K. The canonical (NVT) ensemble was sampled with the Path Integral Langevin Equation (PILE) thermostat70. PIMD based on the force field was performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)71 and the reaction force field46.

The BI dimer was derived from the optimized−8.5°-L structure and pre-optimized in the gas phase prior to AIMD/PIMD simulations. In the calculations, one proton was removed from the BI dimer, resulting in a negatively charged species. This modification places the remaining proton in a symmetric environment, which promotes quantum delocalization within the intermolecular hydrogen bond. At each time step, the reaction coordinate, defined as \({{{\rm{RC}}}}=\,\frac{{d}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}\,}\,-\,{d}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}{\prime} {{{\rm{H}}}}\,}}{{d}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}}\,+\,{d}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}{\prime} {{{\rm{H}}}}\,}},\) was determined by independently extracting the positions of N, N’, and H from all beads, and all possible combinations were enumerated. The resulting probability distribution and free energy profiles of the reaction coordinate were smoothed using a 3-point discrete convolution kernel with a weight of [0.2, 0.6, 0.2] across 200 intervals, followed by a sliding rectangular window filter spanning 9 bins.

PIMD simulation based on force field

Force field-based PIMD simulations were performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)71,72 and the reaction force field46. The normal mode path-integral driver73 implemented within LAMMPS were used to carry out the simulations. A Nose-Hoover massive chain thermostat74 was used to sample the canonical (NVT) ensemble of 32 beads at a temperature of 5 K. The total duration of the simulations was 20 ps with a time step of 0.2 fs. During the simulations, the molecular backbone (C and N atoms) and the substrate (Ag atoms) were fixed. The probability distribution and free energy profiles of the reaction coordinate were smoothed by applying a 3-point discrete convolution kernel with a weight of [0.1, 0.8, 0.1] across 200 intervals. The simulated BI-hexamer on Ag(111) surface exhibited an asymmetric structure (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 27), where the threefold rotational symmetry was broken by rotating molecules L2, L3, L5, and L6 by ≈ 4.8° towards L4 around the center of the hexamer.

AFM simulations

AFM images and force–distance spectra were simulated with the open-source probe-particle model26,39. Parameters: the effective lateral stiffness k = 0.50 N m−1, radial stiffness = 30 N m−1; oscillation amplitude A = 100 pm. The CO-functionalized tip was modeled as a \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)-like charge quadrupole41 with Q = − 0.10 e (where e denotes the elementary charge). Tip–sample interactions combined Lennard–Jones potentials with DFT-based electrostatics computed for BI hexamer on Ag(111).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, X. -Z., Walker, B. & Michaelides, A. Quantum nature of the hydrogen bond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6369–6373 (2011).

Markland, T. E. & Ceriotti, M. Nuclear quantum effects enter the mainstream. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 0109 (2018).

Fang, W., Chen, J., Feng, Y., Li, X. -Z. & Michaelides, A. The quantum nature of hydrogen. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 38, 35–61 (2019).

Cleland, W. W. & Kreevoy, M. M. Low-barrier hydrogen bonds and enzymic catalysis. Science 264, 1887–1890 (1994).

Frey, P. A., Whitt, S. A. & Tobin, J. B. A low-barrier hydrogen bond in the catalytic triad of serine proteases. Science 264, 1927–1930 (1994).

Wang, L., Fried, S. D., Boxer, S. G. & Markland, T. E. Quantum delocalization of protons in the hydrogen-bond network of an enzyme active site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18454–18459 (2014).

Dai, S. et al. Low-barrier hydrogen bonds in enzyme cooperativity. Nature 573, 609–613 (2019).

Ceriotti, M. et al. Nuclear quantum effects in water and aqueous systems: experiment, theory, and current challenges. Chem. Rev. 116, 7529–7550 (2016).

Desiraju, G. R. Supramolecular synthons in crystal engineering – a new organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 34, 2311–2327 (1995).

Barth, J. V. Molecular architectonic on metal surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 375–407 (2007).

Horiuchi, S. & Tokura, Y. Organic ferroelectrics. Nat. Mater. 7, 357–366 (2008).

Pan, D. et al. Surface energy and surface proton order of ice Ih. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 155703 (2008).

Benoit, M., Marx, D. & Parrinello, M. Tunnelling and zero-point motion in high-pressure ice. Nature 392, 258–261 (1998).

Errea, I. et al. Quantum hydrogen-bond symmetrization in the superconducting hydrogen sulfide system. Nature 532, 81–84 (2016).

Kumagai, T. et al. Symmetric hydrogen bond in a water-hydroxyl complex on Cu(110). Phys. Rev. B 81, 045402 (2010).

Tian, Y. et al. Visualizing Eigen/Zundel cations and their interconversion in monolayer water on metal surfaces. Science 377, 315–319 (2022).

Cahlík, A. et al. Significance of nuclear quantum effects in hydrogen bonded molecular chains. ACS Nano 15, 10357–10365 (2021).

Guo, J., Li, X.-Z., Peng, J., Wang, E.-G. & Jiang, Y. Atomic-scale investigation of nuclear quantum effects of surface water: Experiments and theory. Prog. Surf. Sci. 92, 203–239 (2017).

Horiuchi, S. et al. Above-room-temperature ferroelectricity and antiferroelectricity in benzimidazoles. Nat. Commun. 3, 1308 (2012).

Castro Neto, A. H., Pujol, P. & Fradkin, E. Ice: A strongly correlated proton system. Phys. Rev. B 74, 024302 (2006).

Drechsel-Grau, C. & Marx, D. Collective proton transfer in ordinary ice: local environments, temperature dependence and deuteration effects. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 2623–2635 (2017).

Costa, P. S. et al. Structure and proton-transfer mechanism in one-dimensional chains of benzimidazoles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 5804–5809 (2016).

Jelínek, P. High resolution SPM imaging of organic molecules with functionalized tips. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 343002 (2017).

Gross, L., Mohn, F., Moll, N., Liljeroth, P. & Meyer, G. The chemical structure of a molecule resolved by atomic force microscopy. Science 325, 1110–1114 (2009).

Gross, L. et al. Bond-order discrimination by atomic force microscopy. Science 337, 1326–1329 (2012).

Hapala, P. et al. Mechanism of high-resolution STM/AFM imaging with functionalized tips. Phys. Rev. B 90, 085421 (2014).

van der Heijden, N. J. et al. Characteristic contrast in Δfmin maps of organic molecules using atomic force microscopy. ACS Nano 10, 8517–8525 (2016).

Berwanger, J., Polesya, S., Mankovsky, S., Ebert, H. & Giessibl, F. J. Atomically resolved chemical reactivity of small Fe clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 096001 (2020).

Wagner, M., Meyer, B., Setvin, M., Schmid, M. & Diebold, U. Direct assessment of the acidity of individual surface hydroxyls. Nature 592, 722–725 (2021).

Giessibl, F. J. Probing the nature of chemical bonds by atomic force microscopy. Molecules 26, 4068 (2021).

Mohn, F., Gross, L., Moll, N. & Meyer, G. Imaging the charge distribution within a single molecule. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 227–231 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Real-Space Identification of Intermolecular Bonding with Atomic Force Microscopy. Science 342, 611–614 (2013).

Hämäläinen, S. K. et al. Intermolecular contrast in atomic force microscopy images without intermolecular bonds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 186102 (2014).

Mönig, H. et al. Quantitative assessment of intermolecular interactions by atomic force microscopy imaging using copper oxide tips. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 371–375 (2018).

Klappenberger, F. et al. Functionalized graphdiyne nanowires: on-surface synthesis and assessment of band structure, flexibility, and information storage potential. Small 14, 1704321 (2018).

Ernst, K. H. Molecular chirality at surfaces. Phys. Status Solidi B 249, 2057–2088 (2012).

Raval, R. Chiral expression from molecular assemblies at metal surfaces: insights from surface science techniques. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 707–721 (2009).

van der Lit, J., Di Cicco, F., Hapala, P., Jelinek, P. & Swart, I. Submolecular resolution imaging of molecules by atomic force microscopy: the influence of the electrostatic force. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 096102 (2016).

Oinonen, N. et al. Advancing scanning probe microscopy simulations: a decade of development in probe-particle models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 305, 109341 (2024).

Ellner, M. et al. The electric field of CO tips and its relevance for atomic force microscopy. Nano Lett. 16, 1974–1980 (2016).

Peng, J. et al. Weakly perturbative imaging of interfacial water with submolecular resolution by atomic force microscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 122 (2018).

Benoit, M. & Marx, D. The shapes of protons in hydrogen bonds depend on the bond length. ChemPhysChem 6, 1738–1741 (2005).

Marx, D. & Hütter, J. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics: Basic Theory And Advanced Methods. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Li, X.-Z., Probert, M. I. J., Alavi, A. & Michaelides, A. Quantum nature of the proton in water-hydroxyl overlayers on metal surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 066102 (2010).

Feng, Y. et al. The collective and quantum nature of proton transfer in the cyclic water tetramer on NaCl(001). J. Chem. Phys. 148, 102329 (2018).

Zhang, W. & van Duin, A. C. T. Improvement of the ReaxFF Description for Functionalized Hydrocarbon/Water Weak Interactions in the Condensed Phase. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 4083–4092 (2018).

Kumagai, T. et al. Thermally and vibrationally induced tautomerization of single porphycene molecules on a Cu(110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 246101 (2013).

McCunn, L. R., Roscioli, J. R., Johnson, M. A. & McCoy, A. B. An H/D isotopic substitution study of the H5O2+·Ar vibrational predissociation spectra: exploring the putative role of Fermi resonances in the bridging proton fundamentals. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 321–327 (2008).

Drago, V. N. et al. An N⋯H⋯N low-barrier hydrogen bond preorganizes the catalytic site of aspartate aminotransferase to facilitate the second half-reaction. Chem. Sci. 13, 10057–10065 (2022).

Fillaux, F., Cousson, A. & Gutmann, M. J. Proton transfer across hydrogen bonds: from reaction path to Schrödinger’s cat. Pure Appl. Chem. 79, 1023–1039 (2007).

Kaga, A., Saito, H. & Yamano, M. Divergent and chemoselective deuteration of N-unsubstituted imidazoles enabled by precise acid/base control. Chem. Commun. 60, 8920–8923 (2024).

Horcas, I. et al. WSXM: a software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78, 013705 (2007).

Sader, J. E. & Jarvis, S. P. Accurate formulas for interaction force and energy in frequency modulation force spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1801–1803 (2004).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Abinitio molecular-dynamics for liquid-metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Hoover, W. G., Ladd, A. J. C. & Moran, B. High-strain-rate plastic flow studied via nonequilibrium molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1818–1820 (1982).

Evans, D. J. Computer “experiment” for nonlinear thermodynamics of Couette flow. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 3297–3302 (1983).

Kapil, V. et al. i-PI 2.0: a universal force engine for advanced molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 236, 214–223 (2019).

Meng, S. & Kaxiras, E. Real-time, local basis-set implementation of time-dependent density functional theory for excited state dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 054110 (2008).

Lian, C., Guan, M. X., Hu, S. Q., Zhang, J. N. & Meng, S. Photoexcitation in solids: first principles quantum simulations by real-time TDDFT. Adv. Theor. Simul. 1, 1800055 (2018).

Lian, C., Zhang, S. J., Hu, S. Q., Guan, M. X. & Meng, S. Ultrafast charge ordering by self-amplified exciton-phonon dynamics in TiSe2. Nat. Commun. 11, 43 (2020).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Hamann, D. R. et al. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Schlipf, M. & Gygi, F. Optimization algorithm for the generation of ONCV pseudopotentials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 196, 36–44 (2015).

Ceriotti, M., Parrinello, M., Markland, T. E. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Efficient stochastic thermostatting of path integral molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 124104 (2010).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Cao, J. & Berne, B. J. A Born–Oppenheimer approximation for path integrals with an application to electron solvation in polarizable fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 99, 2902–2916 (1993).

Tuckerman, M. E., Berne, B. J., Martyna, G. J. & Klein, M. L. Efficient molecular dynamics and hybrid Monte Carlo algorithms for path integrals. J. Chem. Phys. 99, 2796–2808 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank X.-Z.L. for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant Nos. 2023YFA1407000 (Y.-Q.Z.), 2021YFA1400502 (K.W.), 2021YFA1400503 (C.Z.), and 2021YFA1400201(C.Z., S.M.), National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 12174431 (Y.-Q.Z.), 12025407 (S.M.), and CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research YSBR-047 (C.Z., S.M.). M.R. and S.K. thank the support from DFG-CRC 1573 4 f for Future project B2 (M.R., S.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-Q.Z. and K.W. conceived the experiments. F.G. performed the STM/AFM measurements and analyzed the data with contributions from Y.L., P.C. and L.C. Moreover, C.Y. and C.Z. carried out the DFT and AIMD/PIMD simulations and conducted the analysis. L.Z., E.-G.W. and S.M. contributed to the interpretation of the experimental results. S.K. and R.M. synthesized the deuterated molecules. Y.-Q.Z., F.G., C.Y., C.Z. and K.W. co-wrote the manuscript with input and contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bruno de la Torre, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, F., Yang, C., Lyu, Y. et al. Anomalous rotational-symmetry breaking in proton arrangement of surface-confined cyclic hydrogen bonds revealed by atomic force spectroscopy. Nat Commun 17, 153 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66848-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66848-9