Abstract

Upgrading fatty acid derivatives is a promising route to sustainable diesel and jet fuels, but conventional processes require high temperature, pressure, and large H₂ input, while contaminants in waste oil deactivate catalysts, demanding costly purification. Here, we present an integrated electrochemical strategy combining anodic decarboxylation, cathodic proton reduction, and olefin hydrogenation in one reactor, upgrading fatty acid derivatives to long-chain alkanes under mild conditions (60 °C, 1 atm) without external hydrogen. A high alkane yield of 88.9% is achieved and the reported performance is competitive. Experiments and calculations reveal that fatty acid chain length governs product yield and distribution by influencing –H departure and Cγ–Cβ–COOH bond cleavage barriers. This approach shows high activity and selectivity toward diverse feedstocks, including unsaturated fatty acids, esters, mixtures, crude acids, and waste oils. Powered by solar energy, approximately 40 g of long-chain alkanes are produced in a 1 L reactor, highlighting its scalability and potential for green fuel synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long-chain hydrocarbons, including long-chain alkanes used as diesel and jet fuels, as well as long-chain olefins employed as chemical intermediates, are extensively utilized. Currently, large-scale production of long-chain hydrocarbons primarily relies on petroleum refining, which consumes a significant amount of electricity and emits substantial amounts of toxic and greenhouse gases1,2,3,4. Additionally, the resulting products often contain high levels of sulfur and harmful polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, failing to meet with the stringent international environmental and safety standards5,6,7. Therefore, developing high-yield, mild, and environmentally friendly synthetic routes for long-chain alkanes has become a priority.

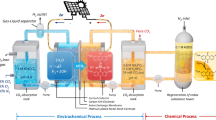

Fatty acids (CxHyCOOH), derived primarily from edible oils, represent valuable feedstock for synthesizing long-chain hydrocarbons due to their structural similarity with –CHx– unit8,9,10,11. In contrast to edible oils, non-edible oils are more cost-effective as they do not encroach upon food resources, thus avoiding competition with the food industry for raw materials. Annually, factories and catering services generate thousands of tons of waste oils, rich in fatty acids and their derivatives, highlighting a significant source of potential raw materials for sustainable energy solutions12. Typically, waste oil undergoes some treatment processes such as anaerobic digestion, aerobic treatment, and co-incineration, which can nonetheless give rise to considerable environmental concerns. Besides, waste oil can be transformed into sustainable fuels through the HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) process, which includes the steps like pretreatment (Fig. S1), catalytic hydrogenation, cracking, isomerization, and fractionation (Fig. 1a)13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, these methods require harsh conditions, such as temperatures exceeding 250 °C and elevated H2 pressures ( ≥ 2 MPa), to reduce the carboxyl group (–COOH) or promote the cleavage of carbon-carbon bonds. Such requirements make these methods unsuitable for achieving commercial viability while simultaneously reducing energy consumption and reliance on fossil fuel-derived hydrogen. In reality, integrating hydrogen species into the reaction system is crucial as it significantly reduces the need for extra H2 input, addressing a common challenge in many catalytic systems. For instance, the decarboxylation of fatty acids to long-chain alkanes can be facilitated by hydrogen species derived from the photocatalytic reduction of water on the Pt/TiO2 catalyst9. To fully eliminate the reliance on fossil fuel–derived H₂, an electrocatalytic system can be employed to achieve both higher efficiency and an adequate supply of hydrogen species21. In such a system, the hydrogen species generated at the cathode are expected to be directly utilized for olefin hydrogenation. However, there is no report on an electrochemical decarboxylative coupled with hydrogenation strategy for the transformation of waste oils into alkanes, which entirely eliminates fossil fuel-derived H₂ input, while delivering high product yields22,23. Therefore, developing methods for such high-profit alkane production under mild conditions and without relying on fossil fuel-derived H2 is imperative for advancing sustainable synthesis.

Here, we demonstrate a highly efficient electrochemically coupled approach that can proceed smoothly even with elevated contaminant levels (like water, salt (mainly NaCl), lipid polymers, food particles/colloid) in the feedstock, obviating the need for costly purification (Fig. 1b). Moreover, the hydrogen species generated through cathodic reduction is directly supplied for the hydrogenation of long-chain olefins produced via anodic oxidation, ensuring efficient integration of these processes. The productivity can be readily optimized. Our method consistently achieves high yields for saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, as well as their esters and mixtures. Investigations reveal that the chain length determines the transformation from carbocations to alkenes accounting for the barriers of –H departure and Cγ–Cβ–COOH bond scission. Importantly, our approach facilitates the conversion of crude fatty acids and waste oils to valuable products. Besides, we have successfully scaled up long-chain alkane production by seamlessly integrating decarboxylation and hydrogenation within a single reactor. This study introduces a comprehensive strategy for the conversion of waste oils into long-chain hydrocarbons, showcasing its potential for industrial applications.

Results and discussion

The production of long-chain alkanes from fatty acids via electrochemical coupling. In the process of electrochemically coupled conversion from fatty acids to long-chain alkanes, three key reactions occur, including anodic decarboxylation to olefins, cathodic proton reduction, and olefin hydrogenation. During anodic decarboxylation, solvents and reactants are prone to competitive adsorption and oxidation, which would result in a markedly low conversion of fatty acids. In addition, it is critical to avoid hydrogen evolution reactions (HER) at the cathode, as this would limit the availability of H species to complete olefin hydrogenation. We began by exploring the electro-decarboxylation of fatty acids in the conditions, including stearic acid (C18), KHCO3, n-Bu4NI, and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), but trace of product was observed. Extensive testing of various solvents and bases, detailed in Tables S1, S2, identifies EtOH and KOH as the most effective for the conversion process.

Notably, a reduced KOH concentration of 0.4 equivalent also maintains yields (Fig. S2), which is beneficial for scale-up production. In contrast, the higher KOH concentrations decay yields due to local fatty acid depletion caused by OH⁻ ion buildup at the anode. In the term of electrolyte stability and conductivity, the n-Bu4NPF6 electrolyte with the concentration of 0.06 M appears optimal, as indicated in Table S3, Fig. S3. Under these refined conditions, the yield of long-chain olefins can reach 83%. Additionally, to minimize solvent usage in a large-scale process, the concentrations of fatty acid are increased to 0.1 M and 0.2 M, which both yield satisfactory results (Fig. S4). The post-electrolysis analysis identifies 1-n-heptadecene as the major product at 54%, alongside 2-n-heptadecene (23%), 3-n-heptadecene (10%), 4-n-heptadecene (4%), and branched olefins (9%). A small portion of the feedstock is converted into heptadecanol ether, constituting less than 10% of the total products.

To increase the decarboxylation efficiency, various electrode materials were evaluated (Fig. 2a). Notably, under identical conditions, the yield obtained with a platinum (Pt) electrode is disappointingly low at less than 10% within 10-hour period. This poor yield is attributed to the propensity to catalyze the oxidation of ethanol24,25,26, which diverts the reaction away from the desired decarboxylation pathway. In contrast to metal, low-cost carbon materials without heteroatom (N, P, B) doping exhibit weak adsorption and minimal alcohol oxidation27,28,29. However, these materials possess a favorable affinity for electro-decarboxylation of carboxylic acids30. The performances of carbon-based materials show significant improvement: Acetylene black (AB) and carbon black (CB) achieve yields of 20–30%, whereas graphite (G) delivers the higher yield of approximate 60%. Furthermore, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), with its large specific surface area attributed to layered structure, enhances electron transfer and mass transport at the solid-electrolyte interface, further boosting the yield to 78%. To further optimize performance, porosity was introduced into the GO structure by etching with KOH at 100 °C, producing a material referred to as p-rGO31. The successfully synthesized p-rGO exhibits a well-defined porous structure, as demonstrated by transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Fig. S5), X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Fig. S6), and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analyses (Fig. S7). One point to note is that BET shows the reduced surface area for p-rGO considering that general BET characterization has limitations in micropores. Because electrolyte ions can effectively access microporous structures, the elelectrochemically active surface area (ECSA) measurement can be a more representative evaluation of electrochemically active surface sites of porous structures. As shown in Fig. S8, the ECSA of p-rGO remains comparable to that of rGO, most likely indicating similar density of electrochemically active surface sites. As reported, the presence of carbon defects can significantly enhance substrate adsorption and accelerate charge-transfer rate32,33. As shown in Fig. S9, Raman spectra demonstrate the D band at 1350 cm−1 and G band at 1570 cm−1, which corresponds to the breathing mode of structural disorder and the in-plane stretching mode of sp2 hybridized carbon atoms, respectively. Compared with rGO, the higher peak intensity (I) ratio (ID/IG) of p-rGO corresponds to the higher concentration of structural defects. Further characterization using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy reveals that the rGO contains a mix of sp³C–O and sp²C–O bonds, while the p-rGO is primarily composed of sp²C–O bonds (Fig. S10). The absence of a distinct C–H bending vibration in p-rGO, observed in rGO, indicates the removal of sp³CHₓ units, which associates with the formation of the porous structure. High-resolution C 1 s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Fig. S11) further supports this finding, with the p-rGO exhibiting a lower binding energy and higher sp²C/sp³C ratio, directly linking its improved performance to the porous architecture. These structural and chemical improvements underline the advantage of p-rGO over commercial carbon materials, as reflected in the enhanced electrochemical performance. However, due to its low adhesion to carbon paper, a composite material comprising rGO and p-rGO in a 5:1 mass ratio was developed. As expected, this composite material significantly outperforms its individual counterparts, achieving a yield of ~90%. In contrast, the bare carbon paper (CP), composed of carbon fibers, affords only ~10% product yield. Throughout the electrochemical process, the FEs remain consistently high (Fig. S12), demonstrating high stability of electricity consumption during the entire process.

a Screening of electrode materials with stearic acid (0.3 mmol), KOH (1.2 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), EtOH (20 mL) and voltage of 3.5 V. b Yield of n-heptadecane from 1-heptadecene hydrogenation using Pt/C and carbon as the cathode in EtOH under otherwise same conditions. c Hydrogenation barrier of olefins as a function of H–H distance, ranging from 0.74 Å (H₂ molecule) to 1.32 Å (two separated H atoms). d Productivity of olefins under different voltages and different moles of fatty acid at 3.5 V. e H2 input-free performances of electrochemically coupled decarboxylation and hydrogenation at different voltages with stearic acid (0.3 mmol), KOH (1.2 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), EtOH (20 mL). The voltage was not iR corrected. Source data for Fig. 2 are provided as a Source Data file.

Further exploration into the voltage-dependent performance (Fig. S13a) reveals that, while the yields for the p-rGO and commercial G are nearly identical at 2 V, FE of p-rGO is 10% higher. As the applied voltage is increased, the difference in both yields and FEs becomes more pronounced, indicating that elevated voltages are more conducive to the decarboxylation process. This can be attributed to higher anode voltages enhancing interaction with negatively charged carboxylates, which in turn form carboxylate layers on the electrode surface that prevent other substances from accessing the electrode (Fig. S13b), consistent with the Frumkin effect. Additionally, the p-rGO exhibits high stability and durability, maintaining high performance over five consecutive cycles without any significant activity loss, as documented in Fig. S14. Moreover, the E–t curves over five consecutive cycles were shown in Fig. S15. The highly consistent profiles of these curves indicate minimal fluctuation, thereby confirming the high stability of the material during the electrocatalytic decarboxylation process. Furthermore, the Raman and FT-IR spectra demonstrate that the structure of the p-rGO can be well preserved (Figs. S9, S10). This stability underscores the potential of the optimized system for scalable and sustainable production processes.

To couple electrochemical decarboxylation and hydrogenation, we introduced a Pd/activated carbon (Pd/C, 20 wt.% Pd) catalyst into the solution, known for its hydrogenation performance on olefins34,35,36. Even when the Pd/C vs. olefin mass ratio is reduced from 0.01 to 0.001, there is no discernible impact on the completion time and yield (Fig. S16), underscoring the robust hydrogenation capacity of Pd/C.

To investigate the cathodic proton reduction process, we examined the electrochemically-assisted hydrogenation of 1-n-heptadecene via using ethanol oxidation as sacrificial anodic reaction. Both ethanol and water, as proton donors, can undergo cathodic electron transfer, converting protons into adsorbed hydrogen atoms that act as reducing agent in the electrolytic hydrogenation of organics37. Also, studies indicate that ethanol and water together enhance hydrogen species adsorption and that adding Pt/C or Pd/C catalysts to the solution promotes hydrogenation of alkynes to alkenes and ketones to alcohols38. Moreover, the absence of alkane formation in aprotic solvents like CH3CN and dimethylformamide (DMF) (Table S4) suggests that the reductive hydrogen species originates from ethanol rather than hydroxide ion (OH⁻). As reported, on Pt/C cathode—the common catalyst for HER across nearly all pH conditions—hydrogen atoms readily combine to form H2 gas (with ΔG close to zero)39, yet the alkane yield is only 7.6% (Fig. 2b). Instead, graphite’s sp² hybridized carbon atoms, forming strong in-plane covalent bonds, exhibit the weaker interaction with hydrogen atoms, which aids in hydrogen atom diffusion and utilization40,41. The barrier for hydrogen gas formation on graphite is rather higher than on platinum, resulting in a higher concentration of weakly adsorbed hydrogen species on the graphite surface over the larger voltage range. Significantly, our experiments demonstrate that alkane yield increases to 82% when graphite rod is used as the cathode. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to suggest barrierless olefin hydrogenation for separated H atoms. It is evident that when H species transition from H2 molecule to separated H atoms, the barrier of olefin hydrogenation decreases significantly (Fig. 2c).

This brief overview presents a synopsis of the coupled synergy between electrochemical decarboxylation and hydrogenation. At the anode, the high potentials enhance the adsorption of carboxylates, forming a shielding layer that minimizes adsorption and oxidative competition with other substances. As shown in Fig. 2d, the productivity at the voltage of 5.5 V is 2.2 times higher than that at the voltage of 3.5 V, meaning that the productivity can be improved significantly through increasing the voltages. Another phenomenon reflecting the promoting effect of high-concentration substrate adsorption on the reaction is the concentration-dependent performance test. As shown in Fig. 2d, the initial reaction rate increases by 10 times and 5 times when the mole of fatty acids only increases from 0.1 to 0.3 mol and from 0.3 to 0.6 mol, respectively. These results suggest that increasing the voltage and concentration of fatty acid is very important to accelerate the electrochemical kinetics. On the other hand, for electrochemical cathodic reaction, EtOH can be reduced on the cathode through electron supply and hydrogen ion acceptance, producing reductive hydrogen species. The high barrier required to release H₂ gas on the graphite means that these species are not primarily volatilized as H₂; instead, they are directed to Pd catalyst, which facilitates the hydrogenation of olefins to alkanes. As a consequence of coupling decarboxylation and hydrogenation, the selectivity for long-chain alkanes exceeds 95% at the voltages of 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5 V, with ~80% conversion, signifying a seamless conversion from fatty acids to long-chain alkanes without interference (Fig. 2e). Note that the higher voltage promotes more H species at the cathode to well synergize the hydrogenation and decarboxylation rate. Therefore, the reported productivity of long-chain alkanes is competitive, compared with relevant photocatalytic and thermocatalytic studies (Fig. S17, Table S5)18,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

Conversion of fatty acids with different chain length and waste fatty acid derivatives. The composition of waste oil is complex, containing a variety of fatty acids and derivatives with different chain lengths. To better understand the mechanism of electrochemical coupling conversion of waste oil and further improve the conversion rate of waste oil, we probed the conversion behavior of fatty acids with different chain length. Fatty acids ranging from C11 to C22 were utilized in this study (Fig. 3a). Fatty acids with under 10 carbons primarily produced nucleophilic products, such as ethers and alcohols, rather than long-chain olefins. C11 and C12 fatty acids achieve moderate yields (30 ~ 40%) of C10 and C11 olefins, respectively. In contrast, for C13–C22 fatty acids, the yields of C12–C21 olefins are significantly higher, reaching 60–90% and peaking with C16 fatty acid. The GCMS spectra of products are shown in Figs. S18~S29.

a Yield and (b) selectivity of decarboxylation into olefins using different carbon-chain length of fatty acids with acid (0.3 mmol), KOH (1.2 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), EtOH (20 mL) and current of 10 mA. c Scheme of the reaction pathways of different 1-n-carbocations from decarboxylation of fatty acids. d The components in crude soybean oil, crude tall oil and waste catering oil. e The results of conversion of crude soybean oil, crude tall oil, and waste catering oil. a The products are olefins; b The products are alkanes. Entry 4 differed from Entry 3 solely by the addition of Pd/C catalyst, with all other reaction conditions held constant. Source data for Fig. 3 are provided as a Source Data file.

The cyclic voltametric results also indicate non-trivial differences in product distribution based on chain length (Figs. 3b, S30). For C11 to C13 fatty acids, 1-n-olefin accounts for only 30 ~ 40% of the olefins, with the remainder being thermodynamically more stable olefins. Instead, for C14 to C19 fatty acids, the 1-n-olefin proportion rises to around 50%, indicating that long-chain fatty acids are more likely to retain the α-carbocations after decarboxylation. Intriguingly, with further chain elongation in C20 to C22 fatty acids, a two-carbon atom departure in the carbocations follows –COOH group removal. Figure 3c illustrates the reaction pathways of carbocations with different carbon length. Obviously, the kinetics of α-carbocation transformation partially determines the olefin production, thereby affecting the efficiency of final alkane.

The chain-length-dependent kinetics of α-carbocation (R–CH2+) is crucial for improving the yield and selectivity of olefins. The initial intermediate species formed during fatty acid decarboxylation is the α-carbocation, and its transformation pathways may be: (1) Directly converting into 1-n-olefins; or (2) Undergoing rearrangement to form other, more stable carbocations, which then convert into other types of olefins. The higher proportion of 1-n-olefins is primarily attributed to α-carbocations, which are favored by reaction kinetics. In contrast, rearranged olefins originate from rearranged carbocations, such as β- and γ-carbocations, and their formation is driven by the thermodynamic stability of internal alkenes. Collectively, the longer the carbon chain, the more favorable the stabilization and dehydrogenation kinetics of the α-carbon carbocation, thereby improving the yield and selectivity.

DFT calculations were performed to examine the dehydrogenation behaviors of α- or β-carbocations derived from fatty acids of varying chain length (Fig. S31, the atomic coordinates of the optimized computational models refer to the provided supplementary data). (a) Short-chains (e.g., C10): Geometry optimization failed to stabilize the α-carbocation, indicating its tendency to rearrange into the more stable β-carbocation. The β-carbocation favors OH quenching over high-barrier dehydrogenation, aligning with the lower olefin yield and selectivity observed for C11 fatty acid. (b) Long-chains (e.g., C15, C17): The α-carbocation is structurally stabilized, enabling low-barrier dehydrogenation to olefins without OH assistance, consistent with the higher olefin yield and selectivity from C16 and C18 fatty acids. (c) Longer-chains (e.g., C19, C21): Besides olefin formation, the α-carbocation can undergo low-barrier Cβ–Cγ bond cleavage, generating a truncated species with two fewer carbons, explaining the chain-shortened products observed.

Calculations above have mentioned that fatty acids with different chain length follow different pathways, thus mixtures encompassing a spectrum of fatty acids were used to suggest that different fatty acids would not interfere with each other. Indeed, all mixtures yield olefins at yields of 70 ~ 95%, underscoring the industrial viability of our method in manufacturing long-chain hydrocarbons. Besides, for unsaturated fatty acids, it is worth noting that our decarboxylation approach can circumvent the formation of alkyl radicals through employing porous carbon material, which are known to non-Kolbe, heterolytic decarboxylation pathways and minimize surface radical accumulation, thus preventing unwanted radical self-coupling and coupling with unsaturated fatty acids53,54,55. As shown in Table S6 and Fig. S32, unsaturated fatty acids achieve high olefin yields of 70 ~ 80% with high selectivity. Also, fatty acid esters were leveraged in one pot, commonly sourced from animal fats and plant oils, in our decarboxylation process. By elevating the KOH to 1.4 equivalent and incorporating H2O to facilitate preliminary ester hydrolysis, the yields of 70 ~ 80% can be successfully achieved (Table S6), highlighting the efficiency in converting esters to valuable olefins.

Further, the conversion of industrial crude fatty acids was operated to verify the feasibility of electrochemical approach. For the production of ‘green’ alkanes, it is advantageous to utilize non-food feedstock to prevent competition with the food sector56,57. Crude soybean and tall oil fatty acids were directly reacted, which are by-products from soybean oil refining and the pulp industry, respectively. Soybean oil is predominantly composed of C18 and C20 acids/esters, with 48.8% additives, whereas tall oil mainly contains C18 acids/esters and 10% additives (Figs. 3d, S33). Both oils demonstrate high yields of around 85%. The conversion of soybean oil yields a mix of C17, C19, and other olefins, whereas tall oil primarily produces C17 olefins (Fig. 3e). Typically, a variety of organic compounds in waste fatty acids impede the conversion of fatty acids in the way of thermocatalysis and photocatalysis for deactivating catalysts and outcompeting for transformation reactions. Therefore, in the study of contaminants, various additives were introduced into the system. Significantly, the contaminants do not adversely affect the electrolytic process (Fig. S34). This resistance to interference could be due to the isolating effect of carboxyl monolayers on the electrode58, and the high local concentration of fatty acids at the solid-electrolyte interface. As supported in Fig. S13, the higher potential significantly boosts the FE.

Waste non-edible oils from catering, a mixture of triglycerides, phospholipid, C16 and C18 fatty acids/esters, along with food residues, salt, water, flavors, and other organic compounds (Fig. 3d), can be effectively processed using our method. As shown in Fig. S35, the waste oil does not include fatty acids with low carbon-chain length, whereas the main component of fatty acids is C16 and C18 acids which can be converted with high yields as displayed in Fig. 3a. Meanwhile, triglyceride and phospholipid readily undergo saponification in strong alkaline solutions, and then exist in two distinct forms in the system after hydrolysis: Glycerine/phosphate and C18 fatty acid that further proceeds decarboxylation. Unlike conventional technique, our electrolytic approach allows for direct use of the waste oil without any prior treatment. It achieves good conversion and high selectivity, even at the feedstock scale of up to 10 grams (Fig. 3e). In general, these clearly illustrate the substantial advantage of our method over traditional methods.

Production of long-chain alkanes from solar cells. Based on the previous confirmation of high activity and stability in the two-electrode system, we have scaled up and utilized solar cells to explore its potential for practical production. Here, utilizing a custom-built reactor (1 L) with three pairs of electrodes (Fig. 4a), large-scale production was successfully demonstrated via this approach. The construction of the electrochemical setup is provided in Fig. S36. Upon the consecutive cycles, 40 grams of long-chain olefins are obtained with 67% yield, which are subsequently converted into approximate 40 grams of long-chain alkanes through hydrogenation. Moreover, the electrochemically coupled decarboxylation and hydrogenation in the reactor yields 12% long-chain olefins and 55% long-chain alkanes (Fig. 4b). It is worth noting that the resulting alkenes or alkanes from the reaction have very low polarity, with retention factors (Rf) values of almost 1 when using petroleum ether as the eluent, while other impurities have Rf values less than 0.1. The significant difference in Rf values makes it easy to separate them from other polar molecules using column chromatography. This greatly reduces the difficulty of subsequent purification, resulting in alkanes with the purity of over 95% after purification. Alternatively, product can be purified through slurry washing in petroleum ether combined with vacuum distillation. The product obtained from slurry washing has the purity of around 70 ~ 80%, and after distillation, the product with the purity as high as 99% can be achieved. These purification methods can be completed in just one hour, significantly shortening the production time from waste oil to long-chain alkanes, thereby reducing the cost of products. According to the comparison presented in Table S8, our product can serve as a viable substitute for diesel fuels. Furthermore, compared to commercial gasoline, petro-diesel, biodiesel, and ethanol fuels, it exhibits the higher calorific value, which translates to greater energy output and improved fuel economy at a lower cost. Notably, the reactor design is compatible with photovoltaic cells, enhancing the sustainability and economic viability of the process. This confirms that our method effectively scales up the production of long-chain alkanes.

a Scale-up production with stearic acid (10 × 7 g, 35 × 7 mmol), KOH (0.78 × 7 g, 14 × 7 mmol), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M) and voltage of 15 V. b Yields of long-chain alkanes and olefins under scale-up decarboxylation and coupling situation. Life cycle (c) FED and (d) GGE of long-chain alkanes production via our method and the default production method (in GREET) in China. Standard electricity structure is the default values in the GREET software. Our electrochemically coupled system involves the utilization of solar energy through solar cells during the transformation, thus the process of the conversion from fatty acids to long-chain alkanes should consider the utilization of solar energy. Source data for Fig. 4 are provided as a Source Data file.

A life-cycle assessment utilizing GREET software reveals that our process is more sustainable than conventional diesel (CD) production and photocatalytic methods, with significant savings in fossil energy depletion (FED) and reduced greenhouse gas emissions (GGE) (Figs. S37, 4c, d, more details in the supplementary information). The FED of our method is marginally lower than that of CD production and nearly five times lower than photocatalytic approach. Similarly, GGE is approximately two and ten times less than those of CD and photocatalytic methods, respectively9. In addition, when solar energy is utilized through solar cells in the system, the FED and GGE are decreased. Moreover, with the inventories from China, the USA, and the European Union (EU) provided for comparative analysis, the FED and GGE present similar results with China (Fig. S38), suggesting that such sustainability can also be realized in other countries when they employ our approach to produce fuels. Significantly, compared with the default production method in GREET, implementing this system on an industrial scale for 100 kt of long-chain alkanes could save around 2192 TJ of fossil energy and reduce GGEs by 112.2 kt, offering an overwhelming advantage over CD production.

In summary, a strategy of electrochemically coupled decarboxylation and hydrogenation was developed for converting fatty acids into long-chain alkanes under ambient conditions (open system, 60 °C, atmospheric pressure and zero H2 input), achieving high productivity and selectivity across a range of carbon-chain lengths. Moreover, the electrochemical performance can be flexibly adjusted by voltage and concentration of fatty acid to avoid competitive adsorption and oxidation of other substances, to achieve high Faradaic efficiency. Additionally, the transformation mechanism from carbocations to alkenes evolved with chain length, progressing through OH–-assisted dehydrogenation, self-dehydrogenation, and β-carbon-carbon bond scission adjacent to the COO– group. Significantly, our system effectively handled various feedstocks, including unsaturated fatty acids, esters, mixtures, crude fatty acids, and waste oil, yielding high selectivity and productivity. Furthermore, the scalable production of long-chain olefins and alkanes was feasible in a straightforward reactor setup. Further improvement was proposed: the reaction setup could be improved by adopting a flow device to maintain a high concentration of fatty acid59; and a base that is soluble in ethanol at room temperature (25 °C) could be used, such as N(n-Bu)4OH. Our approach offers significant reduction in fossil fuel usage and greenhouse gas emissions, outperforming conventional diesel production and photocatalytic process.

Methods

Reagents and materials

Stearic acid was obtained from Meryer (lot #M20114). Potassium hydroxide (KOH) and ethanol were sourced from China National Pharmaceutical Group Corp (lots #10017018 and #10009218, respectively). n-Bu4NPF6 was acquired from Alfa (lot #A17196). All reagents were purchased in their highest commercial purity and used without additional purification. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on 0.25 mm E. Merck silica gel plates (60F-254), with visualization through 254 nm UV light and the iodine fuming technique. Column chromatography utilized Aladdin silica gel (100–200 mesh, particle size 0.075 ~ 0.147 mm). All the electrolyte should be prepared freshly.

Preparation of p-rGO

Graphene oxide (GO, 100 mg) was dispersed in ethanol (EtOH, 10 mL), and sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 100 mg) was introduced in a single batch while stirring. The mixture was continuously stirred at 25 °C for 12 h. Post-centrifugation, the precipitate was washed with copious amounts of distilled deionized water and EtOH, then dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h to yield the reduced graphene oxide (rGO). GO (90 mg) was dispersed in a 1 wt.% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution (60 mL) and refluxed in a round-bottom flask under continuous stirring for 1 h. The resulting treated GO was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and re-dispersed in 60 mL of deionized water. Concentrated hydrochloric acid (36 ~ 38%, 1.5 mL) was then slowly added to the dispersion. The mixture was refluxed for an additional hour, followed by filtration and thorough washing with distilled water and ethanol. Finally, the residue was treated with sodium NaBH4 (100 mg) in ethanol (15 mL) and stirred for 10 h. Afterward, the mixture was centrifuged, and the precipitate was washed extensively with distilled water and EtOH. The product was dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h to obtain porous reduced graphene oxide (p-rGO).

A mixture of rGO and p-rGO in a 5:1 mass ratio was dispersed in EtOH and stirred for 12 h. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the resulting precipitate was washed twice with ethanol. Finally, the product was dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h to yield the composite material.

Preparation of the working electrodes

Prior to the fabrication of the working electrodes, carbon papers were cleaned with a water-EtOH mixture. 10 mg of the catalyst was then dispersed in 0.5 mL of EtOH using ultrasonication for 30 min. Subsequently, 5 μL of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) solution (60%) was added. The resulting ink was drop-casted onto the conductive side of a carbon paper substrate (2 cm by 2 cm).

Optimization of reaction parameters for electrochemical decarboxylation into olefin

Unless otherwise specified, all optimization reactions were performed on a 0.30 mmol scale. The initial screening of solvents, electrolytes, and bases was conducted using a standard protocol: Stearic acid (1.0 equivalent), base (1.2 equivalents), electrolyte (0.06 M), solvent (20 mL), at 60 °C and 3.5 V. For each optimization step, one parameter was varied while the others were held constant. Specifically, the concentration of n-Bu4NPF6 was optimized with the following conditions: Stearic acid (1.0 equivalent), KOH (1.2 equivalent), varying electrolyte concentrations (0.01, 0.06, 0.1, or 0.5 M), in ethanol (20 mL), at 60 °C and 3.5 V. Similarly, the KOH concentration was optimized under the following conditions: Stearic acid (1.0 equivalent), varying KOH amounts (0.4, 1.2, 2.0, or 2.8 equivalents), a fixed electrolyte concentration (0.06 M), in ethanol (20 mL), at 60 °C, and 3.5 V.

General procedure for electrochemical decarboxylative olefin with fatty acid as substrate

The reactor was loaded with carboxylic acid (0.3 mmol), KOH (1.2 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), and EtOH (20 mL). A reactor cap fitted with a working electrode (anode) and a counter electrode (graphite rod) was then inserted into the reaction mixture. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min without an electric current to ensure complete dissolution of the reagents. Following this, the reaction system was subjected to electrolysis at a constant voltage of 3.5 V or a constant current of 10 mA at 60 °C for 10 h. Subsequently, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified via column chromatography using petroleum ether as the eluent to yield long-chain olefins. Time-dependent and voltage-dependent reactions were also conducted under identical conditions, followed by the same post-treatment process. The resulting products were characterized using GCMS to determine the olefin types.

General procedure for electrochemical decarboxylative olefin with fatty acid ester as substrate

The reactor was loaded with ester (0.3 mmol), KOH (1.4 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), and a solvent mixture of EtOH (18 mL) and distilled water (2 mL). A reactor cap, fitted with a working electrode (anode) and a counter electrode (graphite rod), was then installed into the reaction mixture. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min without an electric current to ensure complete dissolution of the reagents. Subsequently, the reaction system was subjected to electrolysis at a constant voltage of 3.5 V at 60 °C for 20 h. After the reaction, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by column chromatography using petroleum ether as the eluent to yield long-chain olefins.

General procedure for electrochemical decarboxylative olefin with crude soybean oil and tall oil as substrates

The reactor was loaded with oil (100 mg), KOH (20 mg), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M) and EtOH (20 mL). A reactor cap, complete with an anode (working electrode) and a cathode (graphite rod), was then placed into the reaction mixture. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min without an electric current to dissolve the reagents. Following this, electrolysis was conducted at a constant voltage of 3.5 V at 60 °C for 10 h. Post-reaction, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was subjected to purification via column chromatography using petroleum ether as the eluent. In crude soybean oil, the mass fraction of fatty acids is 51.2%, which includes 2.3% of C16 fatty acids/esters, 30% of C18 fatty acids/esters, 11.4% of C20 fatty acids/esters, and 7.5% of other fatty acids/esters. In addition to these, there are 48.8% unidentified additives. In crude tall oil, the mass fraction of fatty acids is 90%, which includes 5.5% of C16 fatty acids/esters, 79.8% of C18 fatty acids/esters, 3.2% of C20 fatty acids/esters, and 1.5% of other fatty acids/esters. In addition to these, there are 10% unidentified additives.

The description of specific parameters for GCMS

Column oven temperature: 25 °C; injection port temperature: 25 °C; carrier gas: He; inlet pressure: 100 kPa; total flow rate: 50 mL/min; column flow rate: 1.93 mL min−1; linear velocity: 49.7 cm s−1; purge flow rate: 3 mL min−1; split ratio: −1. GC column: Rtx-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness: 0.25 μm). Ion source temperature: 230 °C; interface temperature: 280 °C; mass scan range: m/z 50–550.

Some specific formulas were described as following:

where np is the mole of the product, n’ is the theoretical moles of the product, ni is the mole of the specific product, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol−1), I is the current (A), t is the reaction time (s or h), mcat is the catalyst mass (g).

Note that the moles of the products were determined by weighing actual mass of the purified product after purifying the reaction mixture through flash column chromatography. The measurements of Faraday efficiency were only performed once.

Coupling reaction of decarboxylation and hydrogenation

The electrochemical reaction conditions were as following: Stearic acid (1.0 equivalent), KOH (1.2 equivalents), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), and EtOH (20 mL) at a temperature of 60 °C and voltages of 3.5, 4.5, or 5.5 V. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at 60 °C without an electric current to ensure the reagents were fully dissolved. Following this, a palladium on carbon (Pd/C, 20 wt.% Pd) catalyst was introduced with a substrate-to-catalyst mass ratio of 1:0.001. The reaction was then stirred for 10 to 15 h at the specified voltages. Post-reaction, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by column chromatography using petroleum ether as the eluent. This process yielded long-chain alkanes along with a small quantity of long-chain olefins.

General procedure for electrochemical transformation from waste catering oil to alkanes

The reactor (1 L) was loaded with waste catering oil (10 g), KOH (2 g), n-Bu4NPF6 (0.06 M), and EtOH (450 mL) + H2O (50 mL). A reactor cap, fitted with three pairs of anodes (working electrodes) and cathodes (graphite rods), was then installed into the reaction mixture. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min without an electric current. Then a palladium on carbon (Pd/C, 20 wt.% Pd, 20 mg) catalyst was added. The reaction system was then subjected to electrolysis at a constant current of 40 mA at 60 °C. After the reaction, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by column chromatography using petroleum ether as the eluent.

We sourced the waste catering oil from the slop bucket in the canteen of Central China Normal University. The waste oil could contain H2O, salt (mainly NaCl), food residue, fatty acids/esters (including C16, C17, C18), triglyceride, and amide. The mass fraction of fatty acids is 25.7%, which includes 4.5% of C16 fatty acids/esters, 1% of C17 fatty acids/esters, and 21.2% of C18 fatty acids/esters.

Contaminant study

In the contaminant study, using stearic acid as the feedstock and maintaining the previously mentioned conditions, various additives (each at 0.3 mmol) were introduced into the reaction system. The additives tested included isopropyl benzene, methyl styrene, phenylacetylene, benzaldehyde, acetophenone, acetonitrile, epoxy phenylethane, and bromobenzene.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical experiments were performed using a CHI760E workstation with a standard three-electrode configuration. The working electrode consisted of carbon paper loaded with the catalyst material, while a graphite rod and an Ag/AgCl electrode served as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Prior to testing, the solution was purged with pure nitrogen for 5 min to remove dissolved oxygen. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were carried out at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1.

Catalyst characterization

Morphological analysis was performed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM; H-7000FA, 100 kV). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using an X-Pert diffractometer (D8 ADVANCE) with graphite monochromatized Cu-Kα radiation. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) measurements were conducted on a VARIAN 600 M spectrometer. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS, EI) analyses were carried out using a SHIMADZU QP2020 smart chromatograph. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS50FTIR spectrometer (Thermo, U.S.A.). Raman spectra were examined with a Thermo Scientific DXR Raman Microscope utilizing a 534 nm laser wavelength. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected on a ThermoFisher EscaLab 250Xi X-ray photoelectron spectrometer equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source (Ephoton = 1486.6 eV), operated at a 10 mA filament current and 14.7 keV filament voltage. The Si2p peak (103.7 eV) of SiO2 additive was employed as a reference for calibration. Specific surface area (SSA) and pore size distribution were determined by Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis using a high-speed automated surface area and pore size analyzer (TriStar II 3020 V1.03.01).

DFT calculations

Computational simulations were performed using Gaussian 09 and Gauss View 5.08, employing the B3LYP hybrid functional. Initial model estimations were made based on the reaction characteristics. Geometry optimization and frequency calculations for transition states were initially conducted at the B3LYP/6-31 G(+)** level with optimization settings specified for a transition state (opt = (calcfc, ts, noeigen)). The calculations targeted a Berny-type transition state. Force constant calculations were performed once. For models containing OH, the charge and multiplicity were set to 0 and singlet, respectively. Conversely, for models without OH, the charge and multiplicity were set to 1 and doublet. Once the transition state was identified, intrinsic reaction coordinates were calculated using IRC at the same computational level, exploring both forward and reverse directions. Force constant calculations were also performed once for these steps.

Life cycle assessment

The GREET 2021 software was utilized to construct calculation models. The energy contribution of each input resource was calculated as a proportion of the total energy input. Data regarding soy oil production, soybean farming, transportation, H2, and solvent alcohol were sourced from the GREET software database. The electricity considered was generated from a mix of sources, with inventories from China, the USA, and the European Union provided for comparative analysis. Production data for the Pd/C catalyst was derived from literature47. The raw materials for electrolyte production included ethylene, methane, ammonia, and electricity, enabling us to construct an LCA for the life cycle of electrolyte. The life cycle FED and GHG emissions were calculated by integrating the estimated materials and energy inputs into the GREET 2021 software.

GHG and FED were calculated based on the equations as following:

where mCO2, mCH4 and mN2O are emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O, respectively, kg; LHVi is the lower heating value of primary fossil energy i, MJ kg−1; Ci is consumption amount of primary fossil energy i, kg.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, S.-Y., Zhang, Q., McLellan, B. & Zhang, T.-T. Review on the petroleum market in China: history, challenges and prospects. Petrol. Sci. 17, 1779–1794 (2020).

Mochida, I., Okuma, O. & Yoon, S.-H. Chemicals from direct coal liquefaction. Chem. Rev. 114, 1637–1672 (2013).

Zaikin, Y. A. & Zaikina, R. F. Upgrading and refining of crude oils and petroleum products by ionizing irradiation. Top. Curr. Chem. 374, 34 (2016).

Brennecke, J. F. & Freeman, B. Reimagining petroleum refining. Science 369, 254–255 (2020).

Vetere, A., Pröfrock, D. & Schrader, W. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of three classes of sulfur compounds in crude oil. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 10933–10937 (2017).

Lim, J., Pyun, J. & Char, K. Recent approaches for the direct use of elemental sulfur in the synthesis and processing of advanced materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3249–3258 (2015).

Fang, J., Rietjens, I. M. C. M., Carrillo, J.-C., Boogaard, P. J. & Kamelia, L. Evaluating the in vitro developmental toxicity potency of a series of petroleum substance extracts using new approach methodologies (NAMs). Arch. Toxicol. 98, 551–565 (2024).

Xu, P. et al. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat. Commun. 4, 1409 (2013).

Huang, Z. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic alkane production from fatty acid decarboxylation via inhibition of radical oligomerization. Nat. Catal. 3, 170–178 (2020).

Hu, Q. et al. Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: Perspectives and advances. Plant J. 54, 621–639 (2008).

Tuck, C. O., Pérez, E., Horváth, I. T., Sheldon, R. A. & Poliakoff, M. Valorization of biomass: deriving more value from waste. Science 337, 695–699 (2012).

Math, M. C., Kumar, S. P. & Chetty, S. V. Technologies for biodiesel production from used cooking oil - A review. Energy Sustain. Dev. 14, 339–345 (2010).

Leung, D. Y. C., Wu, X. & Leung, M. K. H. A review on biodiesel production using catalyzed transesterification. Appl. Energy 87, 1083–1095 (2010).

Gerpen, J. V. Biodiesel processing and production. Fuel Process. Technol. 86, 1097–1107 (2005).

Lestari, S., Maki-Arvela, P., Beltramini, J., Lu, G. Q. & Murzin, D. Y. Transforming triglycerides and fatty acids into biofuels. ChemSusChem 2, 1109–1119 (2009).

Zhang, J. & Zhao, C. Development of a bimetallic Pd-Ni/HZSM-5 catalyst for the tandem limonene dehydrogenation and fatty acid deoxygenation to alkanes and arenes for use as biojet fuel. ACS Catal. 6, 4512–4525 (2016).

Gosselink, R. W. et al. Reaction pathways for the deoxygenation of vegetable oils and related model compounds. ChemSusChem 6, 1576–1594 (2013).

Snåre, M., Kubičková, I., Mäki-Arvela, P., Eränen, K. & Murzin, D. Y. Heterogeneous catalytic deoxygenation of stearic acid for production of biodiesel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45, 5708–5715 (2006).

Zhang, Z. et al. Catalytic decarbonylation of stearic acid to hydrocarbons over activated carbon-supported nickel. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2, 1837–1843 (2018).

Peng, B., Yuan, X., Zhao, C. & Lercher, J. A. Stabilizing catalytic pathways via redundancy: selective reduction of microalgae oil to alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9400–9405 (2012).

Shi, Q. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic Valorization of biomass-derived succinic acid into ethylene coupled with hydrogen production over an ultrathin BiOx-covered TiO2. ACS Catal. 14, 10728–10736 (2024).

Xu, G., Zhang, Y., Fu, Y. & Guo, Q. Efficient hydrogenation of various renewable oils over Ru-HAP catalyst in water. ACS Catal. 7, 1158–1169 (2017).

Sági, D., Solymosi, P., Holló, A., Varga, Z. & Hancsók, J. Waste polypropylene and waste cooking oil as feedstocks for an alternative component containing diesel fuel production. Energy Fuels 32, 3519–3525 (2018).

Michaud, S. E., Barber, M. M., Rivera Cruz, K. E. & McCrory, C. C. L. Electrochemical Oxidation of primary alcohols using a Co2NiO4 catalyst: Effects of alcohol identity and electrochemical bias on product distribution. ACS Catal. 13, 515–529 (2022).

Jin, C., Sun, X., Chen, Z. & Dong, R. Electrocatalytic activity of PdNi/C catalysts for allyl alcohol oxidation in alkaline solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 135, 433–437 (2012).

Fu, X. Y., Wan, C. Z., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. F. Noble metal based electrocatalysts for alcohol oxidation reactions in alkaline media. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2106401 (2022).

Watanabe, H., Asano, S., Fujita, S. -i, Yoshida, H. & Arai, M. Nitrogen-doped, metal-free activated carbon catalysts for aerobic oxidation of alcohols. ACS Catal. 5, 2886–2894 (2015).

Fu, H. et al. Modification strategies for development of 2D material-based electrocatalysts for alcohol oxidation reaction. Adv. Sci. 11, 2306132 (2023).

Meng, J. et al. Metal-free boron/phosphorus Co-doped nanoporous carbon for highly efficient benzyl alcohol oxidation. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200518 (2022).

Holzhäuser, F. J., Mensah, J. B. & Palkovits, R. Non-)Kolbe electrolysis in biomass valorization – a discussion of potential applications. Green. Chem. 22, 286–301 (2020).

Su, C. et al. Tandem catalysis of amines using porous graphene oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 685–690 (2015).

Zhu, J. & Mu, S. Defect engineering in carbon-based electrocatalysts: Insight into intrinsic carbon defects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001097 (2020).

Lee, W. J., Lim, J. & Kim, S. O. Nitrogen dopants in carbon nanomaterials: Defects or a new opportunity?. Small Methods 1, 1600014 (2017).

Teschner, D. et al. The roles of subsurface carbon and hydrogen in palladium-catalyzed alkyne hydrogenation. Science 320, 86–89 (2008).

Liu, X. et al. Selective hydrogenation of citral to 3,7-dimethyloctanal over activated carbon supported nano-palladium under atmospheric pressure. Chem. Eng. J. 263, 290–298 (2015).

Gómez-Sainero, L. M., Seoane, X. L., Fierro, J. L. G. & Arcoya, A. Liquid-phase hydrodechlorination of CCl4 to CHCl3 on Pd/carbon catalysts: Nature and role of Pd active species. J. Catal. 209, 279–288 (2002).

Conway, B. E. & Tilak, B. V. Interfacial processes involving electrocatalytic evolution and oxidation of H2, and the role of chemisorbed H. Electrochim. Acta 47, 3571–3594 (2002).

Wu, W., Wu, X.-Y., Wang, S.-S. & Lu, C.-Z. Catalytic hydrogen evolution and semihydrogenation of organic compounds using silicotungstic acid as an electron-coupled-proton buffer in water-organic solvent mixtures. J. Catal. 378, 376–381 (2019).

Anantharaj, S. & Noda, S. Layered 2D PtX2 (X = S, Se, Te) for the electrocatalytic HER in comparison with Mo/WX2 and Pt/C: Are we missing the bigger picture?. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1461–1478 (2022).

Jiao, Y., Zheng, Y., Davey, K. & Qiao, S.-Z. Activity origin and catalyst design principles for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution on heteroatom-doped graphene. Nat. Energy 1, 16130 (2016).

Liu, X. & Dai, L. Carbon-based metal-free catalysts. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16064 (2016).

Sun, X., Chen, J. & Ritter, T. Catalytic dehydrogenative decarboxyolefination of carboxylic acids. Nat. Chem. 10, 1229–1233 (2018).

Tlahuext-Aca, A., Candish, L., Garza-Sanchez, R. A. & Glorius, F. Decarboxylative olefination of activated aliphatic acids enabled by dual organophotoredox/copper catalysis. ACS Catal. 8, 1715–1719 (2018).

Luo, N. et al. Visible-light-driven coproduction of diesel precursors and hydrogen from lignocellulose-derived methylfurans. Nat. Energy 4, 575–584 (2019).

Hopen Eliasson, S. H., Chatterjee, A., Occhipinti, G. & Jensen, V. R. Green solvent for the synthesis of linear α-olefins from fatty acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 4903–4911 (2019).

Liu, Y., Yang, X., Liu, H., Ye, Y. & Wei, Z. Nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon supported Pt nanoparticles as a highly efficient catalyst for decarboxylation of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids to alkanes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 218, 679–689 (2017).

Jeništová, K. et al. Hydrodeoxygenation of stearic acid and tall oil fatty acids over Ni-alumina catalysts: Influence of reaction parameters and kinetic modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 316, 401–409 (2017).

Berenblyum, A. S., Podoplelova, T. A., Shamsiev, R. S., Katsman, E. A. & Danyushevsky, V. Y. On the mechanism of catalytic conversion of fatty acids into hydrocarbons in the presence of palladium catalysts on alumina. Petrol. Chem. 51, 336–341 (2011).

Berenblyum, A. S., Danyushevsky, V. Y., Katsman, E. A., Podoplelova, T. A. & Flid, V. R. Production of engine fuels from inedible vegetable oils and fats. Petrol. Chem. 50, 305–311 (2010).

Lestari, S. et al. Diesel-like hydrocarbons from catalytic deoxygenation of stearic acid over supported Pd nanoparticles on SBA-15 catalysts. Catal. Lett. 134, 250–257 (2010).

dos Santos, T. R., Harnisch, F., Nilges, P. & Schröder, U. Electrochemistry for biofuel generation: Transformation of fatty acids and triglycerides to diesel-like olefin/ether mixtures and olefins. ChemSusChem 8, 886–893 (2015).

Wang, W.-C. & Tao, L. Bio-jet fuel conversion technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 53, 801–822 (2016).

Manley, D. W. et al. Unconventional titania photocatalysis: Direct deployment of carboxylic acids in alkylations and annulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13580–13583 (2012).

Manley, D. W. & Walton, J. C. A clean and selective radical homocoupling employing carboxylic acids with titania photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 16, 5394–5397 (2014).

Holzhäuser, F. J. et al. Electrochemical cross-coupling of biogenic di-acids for sustainable fuel production. Green. Chem. 21, 2334–2344 (2019).

Pattanaik, B. P. & Misra, R. D. Effect of reaction pathway and operating parameters on the deoxygenation of vegetable oils to produce diesel range hydrocarbon fuels: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 73, 545–557 (2017).

Hill, J., Nelson, E., Tilman, D., Polasky, S. & Tiffany, D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. PNAS 103, 11206–11210 (2006).

Hintz, H. A. & Sevov, C. S. Catalyst-controlled functionalization of carboxylic acids by electrooxidation of self-assembled carboxyl monolayers. Nat. Commun. 13, 1319 (2022).

Noël, T., Cao, Y. & Laudadio, G. The fundamentals behind the use of flow reactors in electrochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 2858–2869 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52202202, 22472005, 22406009 and 21972052). D.M. acknowledges support from the Tencent Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M., S.O., X.R. and Z.W. conceived the project. W.W. and X.L. performed most of the reactions. W.W., X.L., Z.W., H.Y., Q.Z., X.R., S.O., T.Z. and D.M. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All of the authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Wang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Wei, Z., Luo, X. et al. Sustainable alkane production from waste fatty acids via electrochemically coupled decarboxylation and hydrogenation. Nat Commun 17, 140 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66858-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66858-7