Abstract

Retrogressive thaw slumps are an increasingly prevalent form of abrupt permafrost thaw that can reshape ecosystem carbon exchange, yet their impacts remain poorly quantified. Here we show, using chamber measurements of fluxes at five young slumps during the 2024 growing season and a complementary August 2025 survey at five young and two older slumps, that thaw slumps shift alpine grasslands on the interior Tibetan Plateau from a carbon sink toward a carbon source. Exposed, vegetation-free surfaces halve respiration but reduce gross primary productivity by approximately four-fifths, producing a large increase in net CO2 release relative to undisturbed ground. CH4 uptake occurs but is too small to offset these losses. Cross-age comparisons show that the CO2 anomaly diminishes with time, with net exchange trending toward undisturbed levels. Together these results support a single-peak trajectory: expansion of exposed areas drives a source state, followed by partial recovery as vegetation re-establishes. These findings highlight the critical role of thaw slumps in reshaping alpine grassland carbon dynamics and underscore the need to incorporate abrupt thaw and its age dependence into carbon–climate models under ongoing permafrost degradation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Permafrost underlies ~22% of the Northern Hemisphere’s land area1 and stores about half of the global belowground organic carbon, estimated at roughly 1035 ± 150 Pg within the top three meters2,3,4. Accelerating climate warming has induced widespread permafrost thaw5,6, potentially mobilizing substantial carbon stocks as greenhouse gases, a process known as the permafrost carbon feedback (PCF)4,7. Despite advances in modeling permafrost carbon emissions, large uncertainties persist in PCF projections4, attributed to variations in permafrost distribution datasets2,8,9, substrate heterogeneity10,11, and the complexity of thaw dynamics. Traditional approaches have primarily modeled permafrost thaw as a gradual process at rates of centimeters per decade12,13. However, recent evidence highlights abrupt thaw events, such as thermokarst landforms14,15,16, which can mobilize significant carbon pools within days to a few years, considerably increasing both actual carbon release and uncertainty in carbon emission estimates12,17,18. By contrast, thermokarst landscapes account for roughly 20% of Arctic permafrost regions, yet they contain about half of the soil organic carbon (SOC) stored there, with the potential to increase century-scale carbon emissions by up to 40% relative to gradual thaw alone14,18,19. Thus, neglecting abrupt thaw processes likely leads to substantial underestimation of PCF magnitude17,18,20, underscoring the critical need to better quantify and incorporate these dynamics into global climate models13.

In Arctic circumpolar permafrost regions, extensive studies have characterized thermokarst processes through both large-scale modeling approaches focused on long-term carbon emissions21,22,23 and detailed small-scale field investigations of greenhouse gas fluxes24,25,26. Such research has highlighted significant and complex impacts of thermokarst features on regional carbon and nitrogen cycling. However, despite this breadth of research, specific studies addressing the impacts of retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS), a prominent type of hillslope thermokarst, on ecosystem carbon dynamics remain limited even in the well-studied Arctic regions. On the Tibetan Plateau (TP), where permafrost spans more than one million km2 8 and stores ~33 Pg of SOC3,27,28, local permafrost exhibits distinctive traits, including thicker active layers, warmer ground temperatures, and lower ice content compared to Arctic regions29. Over recent decades, the TP has experienced warming at ~1.5–2 times the global average rate5, resulting in pronounced permafrost degradation30,31 and increasing thermokarst occurrences, including thermo-erosion gullies (TEG), thermokarst lakes (TL), and RTS16,32,33, analogous to those observed in Arctic regions15,34. While the impacts of TEG and TL on carbon dynamics have been extensively documented on the TP35,36,37,38,39,40, the role of RTS remains notably understudied.

RTS and TEG, both classified as hillslope thermokarst features triggered by ground ice thaw, differ markedly in scale, spatial extent, and microtopography. These distinctions raise important, yet unresolved, questions regarding how RTS specifically influence greenhouse gas fluxes and whether RTS-affected landscapes serve as carbon sources or sinks. Importantly, these critical gaps in understanding the carbon dynamics associated with RTS exist not only on the TP, but also persist in Arctic circumpolar permafrost regions, underscoring the need for further investigation across global permafrost regions.

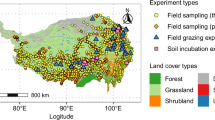

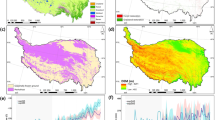

To fill these knowledge gaps, we conducted systematic field measurements of CO2 and CH4 fluxes at five representative young RTS sites spanning four successional initiation years (2016–2019) on the interior TP (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1) throughout the 2024 growing season (May to October), and a complementary survey in August 2025 at the five young and additional two older thaw slump sites initiated in 1992 (Supplementary Fig. S21) and 2010 (Supplementary Fig. S22). The climate conditions, soil properties, vegetation characteristics and permafrost conditions at these study sites41,42,43 are representative of the broader region, where increasing RTS occurrences have been reported16,32. Considering the pronounced morphological disturbances associated with RTS, we hypothesized substantial alterations in carbon dynamics following RTS occurrence, especially in vegetation-removed (exposed) areas. Specifically, our objectives were to: (1) quantify alterations in CO2 and CH4 fluxes across distinct morphological patches created by RTS, including the disturbed patch types of exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR), disturbed ground (DG), and the undisturbed patch type of control (CO) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. S1–S5, Supplementary Table S2); (2) evaluate the seasonal net carbon budgets of RTS-affected landscapes; and (3) characterize the temporal impact patterns of RTS on alpine grassland carbon budgets. Our findings aim to provide critical insights for integrating abrupt thaw dynamics into global PCF projections, thus supporting climate adaptation strategies in rapidly warming permafrost ecosystems.

a Distribution of permafrost in the northern hemisphere. Map based on the previous work1 and the dataset “Ground Temperature Map, 2000–2016, Northern Hemisphere Permafrost” (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.888600; licence: CC-BY-3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)77. The cartographic layout and colour scheme were adapted, but the underlying data were not modified. b Permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau (TP). Map derived from the dataset “Permafrost Distribution on the Tibetan Plateau” (https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-11-2527-2017-supplement; licence: CC-BY-3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/)8. Only map styling and annotation were edited; the source data were not changed. c Locations of the five studied RTS sites (BL, BR, FS, FN and FX) on a colored elevation background. Elevation data are from the dataset “Topographic data of Qinghai Tibet Plateau (2021)” (https://doi.org/10.11888/SolidEar.tpdc.272210)78, used here with permission from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. The elevation values were kept unchanged; only colour rendering and site markers were added. Numbers in parentheses indicate initiation year. Red bars represent changes in RTS area over observation periods, values beneath bars (m2) indicate 2024 RTS areas, and percentages (%) above bars are mean annual areal expansion rates over observation periods. d–i Representative photographs illustrating the morphological patch types identified within the RTS sites (Photo credit: Guanli Jiang, captured in July and August 2024). Ground surfaces were categorized into four types used for flux measurements: control (gray), exposed (orange), vegetated raft (blue), and disturbed ground (green). A minor category, drape (purple), was mapped for area statistics but excluded from flux measurements due to collar installation constraints (see Methods). Detailed plot layouts for each patch type at all five RTS sites are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1–S5.

Results

Changes in soil carbon stocks following RTS occurrence

RTS not only dramatically altered the microtopography of alpine grasslands, but also led to substantial changes in soil carbon stocks. To quantify these effects, we analyzed soil samples collected across all RTS sites (see Methods). To reduce spatial heterogeneity effects (Supplementary Fig. S6a, b), data were normalized, revealing significant differences in soil carbon densities among the patch types (Supplementary Fig. S6c, d). Relative to undisturbed control patches, exposed patches showed significant reductions in SOC density, decreasing by 52 ± 34.3% and 38 ± 29.4% in the 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil layers, respectively (Fig. 2a, c). Conversely, vegetated raft and disturbed ground patches exhibited slight increases in SOC density compared to undisturbed patches; however, these differences were not statistically significant.

a, c Alterations in soil organic carbon (SOC) densities at 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil depths. b, d Alterations in total carbon (TC) densities at 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil depths. e–h Alterations in gas fluxes of ecosystem respiration (ER), net ecosystem exchange (NEE), gross primary productivity (GPP) and CH4 during the 2024 growing season. Mean values from undisturbed control (CO) patches at each RTS site served as baselines (SOC density: 3.5 ± 1.3 kg m−2 (0–15 cm), 2.2 ± 0.7 kg m−2 (15–30 cm); TC density: 6.9 ± 2.0 kg m−2 (0–15 cm), 5.7 ± 1.7 kg m−2 (15–30 cm); ER: 1.4 ± 0.2 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1; NEE: −0.6 ± 0.2 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1; GPP: 2.0 ± 0.3 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1; CH4 flux: −2.7 ± 0.1 nmol CH4 m−2 s−1; mean ± SD). Percent changes of fluxes for each measurement in disturbed patches (exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR) and disturbed ground (DG)) relative to the mean value for control patches at each site were then pooled across all RTS sites for statistical analysis. IQR denotes interquartile range. Statistical significance was determined by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) performed directly on the original measurements from disturbed and control patches. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001; n.s. non-significant).

Similar patterns were observed for total carbon (TC) stocks. Within the 0-15 cm layer, TC densities in EX patches significantly decreased by 25 ± 21.6% relative to controls (Fig. 2b). Although TC densities also declined at 15–30 cm depths in exposed patches, these reductions were not statistically significant (Fig. 2d). Vegetated raft and disturbed ground patches showed only minor, statistically non-significant variations in TC densities compared to undisturbed areas (Fig. 2b, d).

Alterations in CO2 and CH4 fluxes induced by RTS

RTS also markedly altered CO2 flux dynamics in alpine grasslands. Measurements using static closed-chamber methods (see Methods) across five RTS sites during the 2024 growing season revealed significant differences in CO2 fluxes among patch types. ER was consistently lower in exposed patches compared to other patch types at all sites (Supplementary Figs. S7, S8). Specifically, relative to undisturbed areas, average ER in exposed patches decreased by 49 ± 20.1%, GPP decreased by 82 ± 19.7%, and NEE increased by 181 ± 70.9% (Fig. 2e–g). In vegetated raft and disturbed ground patches, all CO2 fluxes including ER, NEE and GPP, exhibited minor and statistically non-significant variations relative to control patches. CH4 fluxes remained generally negative (uptake) across all patch types, averaging between −2.7 ± 0.1 nmol m−2 s−1 in control patches and −2.3 ± 0.2 nmol m−2 s−1 in vegetated raft patches. Although slight variability was observed among patch types, these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Figs. S7, S8).

Key drivers influencing ER and GPP variability

Given the pronounced differences in ER and GPP among patch types, we used partial least-squares path modeling (PLS-PM) to identify mechanisms regulating their variability (see Methods). The analysis identified ground temperature (Supplementary Fig. S9a) and vegetation conditions (Supplementary Fig. S10) as the dominant regulators of ER, with microtopographic patch types exerting significant direct effects and additional indirect effects through vegetation and other intermediates. Soil moisture contributed positively but with a weaker total effect than vegetation and ground temperature (Fig. 3a, c). For GPP, soil moisture and vegetation were the dominant factors, while patch type and ground temperature were secondary contributors (Fig. 3b, d). Notably, substrate availability (Supplementary Fig. S11) and soil physical properties (Supplementary Fig. S12) showed no significant effects on either ER or GPP in our sites, which likely reflects comparatively lower SOC stocks and distinct soil characteristics relative to many Arctic tundra systems26,44,45.

Partial least-squares path modeling (PLS-PM) illustrating multipath relationships for ER (a) and GPP (b). Patch types (exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR), disturbed ground (DG), control (CO)) represent distinct morphological categories within retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS) sites. RTS age denotes time since initiation. Soil chemical properties include salinity and pH at 0–10 cm. Soil moisture is volumetric water content at 0–10 cm. Ground temperature was measured at 10 cm depth. Vegetation is represented by normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), aboveground biomass, and belowground biomass at 0–10 cm and 10–30 cm. Substrate refers to SOC content at 0–15 cm, normalized within site. Soil physical properties include sand content and bulk density at 0–15 cm. Arrows indicate statistically significant pathways, with red and grey lines representing positive and negative effects, respectively. Only significant paths are shown. Line thickness and numerical values indicate the strength of each relationship. Significance levels are indicated by asterisks (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001). R2 and GOF denote the coefficient of determination and Goodness-of-Fit. Standardized effect sizes of environmental factors influencing ER (c) and GPP (d).

The PLS-PM analyses revealed two principal pathways by which RTS influences ER (Fig. 3a): (1) Microtopographic regulation (Patch type): Patch type acted as a key upstream factor, directly influencing ER, as well as indirectly modulating it through significant effects on vegetation conditions, soil moisture and ground temperature. This highlights the substantial impact of RTS-induced microtopographic alterations on ecosystem carbon dynamics. (2) Ground temperature regulation: Ground temperature was the most influential direct factor controlling ER, underscoring the central role it plays in directly regulating respiratory processes. For GPP, the PLS-PM results (Fig. 3b) indicated that microtopographic patch types primarily influenced vegetation conditions, which in turn regulated GPP indirectly.

Although differences in CH4 fluxes among patches were not statistically significant, we examined two environmental factors that could influence CH4 dynamics. High soil sand content was consistent across patches (Supplementary Fig. S12b), which generally favors CH4 emissions by enhancing soil aeration. However, water-filled pore space in the 0–15 cm topsoil varied among patches but averaged below 30 percent (Supplementary Fig. S12c), which is lower than the 50–90 percent reported for northern TP sites where persistent anaerobic conditions favored higher CH4 production35. Thus, persistent anaerobic conditions conducive to CH4 emissions were unlikely at our study sites. At FN and FS sites, we also assessed microbial functional groups involved in CH4 metabolism (see Methods). The relative abundances of methanogenic and methanotrophic taxa did not differ among patch types (Supplementary Fig. S13), which is consistent with the absence of significant CH4 flux contrasts. This coherence among environmental conditions, microbial community composition, and CH4 fluxes strongly suggests that CH4 emissions in our study area were constrained by unfavorable conditions for anaerobic microbial activity.

Discussion

Using measured CO2 flux data, we quantified seasonal carbon budgets (CO2-C) during the 2024 growing season for each RTS site (see Methods). Results indicated that although FS and BL sites had transitioned into net carbon sources, the other three RTS sites remained net carbon sinks, albeit with substantially reduced sink capacities (Fig. 4a). During the 2024 growing season, RTS occurrences led to additional carbon emissions ranging from 181.4 to 1672.5 kg CO2-C across the five RTS sites (Fig. 4b). Variability in these emissions primarily reflected differences in total RTS area and proportional distributions of distinct patch types (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table S1). Consistent with this pattern, the three sites that remained weak sinks (BR, FN, and FX) had relatively large combined areal fractions of vegetated raft and disturbed ground (VR + DG: 72.6%, 56.4%, and 68.2%, respectively), which likely buffered the carbon source effect associated with exposed patches, as indicated by patch-resolved CO2 flux contrasts (Fig. 2g–i). By contrast, FS had the highest fraction of exposed area (~75.0%) and the lowest fraction of vegetated raft and disturbed ground (~24.4%), which accords with its clear carbon source status. BL also became a source, even though its fraction of exposed area (~33.6%) was lower than that at FN (~43%), indicating that while area composition provides the major control, site-level differences in vegetation productivity and related properties can partially modulate the net outcome. Although exposed patches exhibited net CH4 uptake during the 2024 growing season (Fig. 2j), the magnitude (−2.6 ± 0.6 mg CH4-C m−2 day−1; mean ± SD) was negligible, offsetting merely ~0.74% of CO2-C emissions (351.3 ± 195.2 mg CO2-C m−2 day−1; mean ± SD), thus insufficient to mitigate their carbon-source characteristics.

a Seasonal carbon budgets for each RTS site during the 2024 growing season. Red bars represent carbon budgets of disturbed RTS areas (exposed, vegetated raft and disturbed ground patches), while navy bars indicate budgets for undisturbed alpine grassland areas with equivalent extents. Negative values denote net carbon uptake (sink), and positive values represent net carbon emissions (source). The detailed method for carbon budget calculation is described in Methods. b Additional carbon emissions attributed to RTS occurrence during the 2024 growing season, calculated as differences between disturbed RTS areas and their undisturbed counterparts. c Areal distributions of patch types (exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR), disturbed ground (DG) and drape) at each RTS site. Percentage values (%) indicate the areal fractions of exposed patches within each RTS during July–August 2024.

Tracking changes in the areal fraction of exposed patches across the five young RTS from 2019 to 2024 shows that areal fraction of exposed patches increases in step with total area expansion and is particularly evident at the two youngest sites (FN and FX, initiated in 2019) (Supplementary Fig. S14). This rapid expansion amplifies the landscape-scale carbon source effect because the immediate flux response is dominated by newly exposed, vegetation-free ground surfaces.

RTS disturbance also reshapes soil carbon dynamics. During the 2024 growing season, cumulative CO2-C emissions from exposed patches across the five RTS corresponded to ~7.6 ± 1.24% of the 0–30 cm topsoil SOC stock. In these vegetation-free patches, limited litter inputs constrain replenishment, so microbial decomposition continues to deplete SOC, with the labile particulate organic carbon (POC) fraction declining faster than the more stable mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC). Consistent with this mechanism, the POC fraction decreases with RTS age in exposed patches across the five young RTS sites (Supplementary Fig. S15). Diminishing POC availability moderates ER in exposed patches over time, slowing further strengthening of the carbon source effect at the landscape scale. Concurrently, as headwall retreat advances onto steeper, more ice-poor hillslopes, the geomorphic driver of rapid areal growth weakens, slowing the expansion of exposed patches and signaling an approach to a stabilization stage.

In this stabilization stage, total RTS area and patch fractions become stable and vegetation re-establishes on formerly bare ground. The return of photosynthetic capacity increases GPP and drives NEE back toward undisturbed levels (Supplementary Fig. S34). Under these conditions, the carbon balance shifts back toward a net sink, strengthening site-level carbon sink effect while diminishing carbon source effect.

Taken together, observations from the 2024 growing season and the August 2025 age-contrast campaign (see Supplementary Note: Age-contrast analyses across the RTS chronosequence) support a single-peak trajectory of RTS-induced carbon budget alteration on the TP (Fig. 5b). During the expansion stage, increasing exposed patches progressively weaken the grassland carbon sink, eventually reaching peak carbon source conditions. During the subsequent stabilization stage, as thaw slump stabilizes and revegetation progresses, carbon source effect wanes and the system partially recovers toward a net carbon sink. Hence, the areal fraction of exposed patches and the pace of vegetation recovery emerge as the primary determinants of post-RTS carbon dynamics.

a Conceptual representation of CO2 and CH4 fluxes associated with three major thermokarst landforms: retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS), thermo-erosion gullies (TEG) and thermokarst lakes (TL). Upward arrows indicate emission and downward arrows indicate uptake. Arrow lengths illustrate direction of change only and not flux magnitude. White stars mark statistically significant changes in gas flux. Flux patterns for TEG and TL are adapted from previous studies35,50,52,53. b Conceptual trajectory for RTS effects on the carbon budget of alpine grasslands. RTS development comprises two stages: expansion and stabilization. During the expansion stage, total slump area increases rapidly together with the areal fraction of exposed, vegetation-free surfaces. These newly exposed patches are defined by bare ground lacking established vegetation communities, a relatively high proportion of particulate organic carbon (POC) in soil organic carbon (SOC), and a net carbon-source state. As exposed area expands, the site-level carbon budget shifts from a sink to a source. During the subsequent stabilization stage, the fraction of exposed area ceases to increase. Vegetation progressively colonizes bare ground and forms stable communities. Due to limited carbon replenishment before vegetation is fully established, the fraction of POC in SOC decreases significantly. With vegetation recovery and depletion of labile carbon (POC), emissions from exposed patches decrease and the site-level carbon budget trends back toward a sink. c Conceptual pattern illustrating the impact of TEG on the carbon budget of alpine grasslands. d Reported CO2 and CH4 fluxes datasets for major thermokarst landforms. Datasets for TEG and TL are from previous studies. For TEG, CH4 fluxes are derived from the dataset obtained from July to August, 201635; CO2 fluxes are derived from the dataset obtained from May to October, 201850. For TL, CO2 diffusion fluxes and CH4 diffusion fluxes are sourced from the dataset obtained from May to August, and September, 202053; CH4 ebullition fluxes are sourced from the dataset obtained from June to October, 202052.

Evidence for this trajectory is consistent across a chronosequence that includes the five young and two older RTS (Supplementary Figs. S21–S23): we observe coherent alterations in greenhouse-gas fluxes during disturbance and progressive recovery (Supplementary Figs. S8, S31, S33). Moreover, statistical comparisons of patch-type ER show no significant among-site differences across the five young slumps during the 2024 growing season (Supplementary Fig. S16), indicating that the disturbance signal is stable across sites at short timescales. The transition toward full carbon sink recovery driven by revegetation in exposed patches likely requires longer timescales, potentially decades, consistent with our inclusion of older sites. Although our flux measurements are confined to May–October 2024 and August 2025, the combination of season-long observations and cross-age contrasts captures the fundamental pattern of RTS impacts on ecosystem carbon dynamics and illuminates the key mechanisms governing their temporal evolution.

To date, continuous growing-season measurements of carbon-related greenhouse gas fluxes in RTS-affected areas remain scarce, with limited existing data from Arctic Alaska26. Comparing our TP findings (May–October 2024) with those from Alaska (June–August 2009–2011) highlights substantial regional differences. For instance, undisturbed patches around RTS exhibited higher average ER in Alaska (2.07 ± 0.2 g CO2-C m−2 day−1, mean ± SE, based on monthly data from June to August) than on the TP (1.47 ± 0.1 g CO2-Cm-2 day−1, mean ± SE, based on monthly data from May to October). Although ER was significantly reduced in exposed patches in both regions (by 57% in Alaska and 48% on the TP), vegetated raft patches showed contrasting ER patterns: higher than controls by 26% in Alaska but slightly and non-significantly lower on the TP. Similarly, CH4 dynamics differed notably. Soil CH4 concentrations at 10–15 cm in Alaska were significantly elevated in exposed and vegetated raft patches, whereas on the TP, CH4 fluxes did not differ significantly among patch types. These regional discrepancies likely reflect heterogeneity in permafrost properties. Active layer were shallower (~35 cm) in Alaska26,46,47 than in our study region on the TP (1.6–2.2 m)48. SOC stocks in Alaska (organic layer to 12.6 ± 0.8 cm: 6.9 ± 0.5 kg m−2; mineral layer to 35 cm: 7.4 ± 0.5 kg m−2)26 exceeded those in our TP sites (0–15 cm: 3.5 ± 0.6 kg m−2; 15–30 cm: 2.2 ± 0.3 kg m−2), consistent with previous local data (0–20 cm: 5.7 ± 1.2 kg m−2; 20–40 cm: 5.0 ± 0.8 kg m−2)49 (all values are presented as mean±SE). Ground temperature and soil moisture also differed substantially between regions. In Alaska, mean ground temperatures at 15 cm were significantly higher in exposed (10.8 °C) and vegetated raft (9.7 °C) patches than in controls (6.4 °C)26. Conversely, on the TP, ground temperatures at 10 cm were significantly lower in these disturbed patches than in controls. For soil moisture, no significant differences among patch types were observed in the top 6 cm layer in Alaska, while on the TP the 0–10 cm layer was significantly drier in exposed patches than in other patch types. Despite these environmental differences, the influence of RTS on carbon dynamics appears broadly comparable in both Arctic and the TP regions, although the magnitude and direction of specific responses depend on local permafrost conditions.

In addition to regional contrasts, a comparison of the three major thermokarst landforms on the TP, namely RTS, TEG, and TL, also highlights diverse and distinct impacts on alpine grassland carbon cycling (Fig. 5a). TEG, another hillslope thermokarst landform formed by ground ice thaw, also creates vegetated raft, drape, and exposed surfaces, yet the areal fraction of exposed patches in TEG is generally low (6.3 ± 1.2%, n = 3)26. Consequently, the TEG carbon budget is predominantly influenced by vegetated raft and drape patches that tend to retain original vegetation. The effect of TEG on carbon cycling further depends on time since collapse, because enhanced vegetation growth after TEG occurrence can strengthen the carbon sink effect over time50,51 (Fig. 5c). TL, a lowland thermokarst feature on the TP, also exerts a strong influence on carbon dynamics by converting alpine grasslands from carbon sinks to sources37,52,53, with relatively high emission rates53. Fluxes associated with TL also vary with grassland type and with ice-melting and drainage events37,39,40. These comparisons show that, although the landforms share abrupt-thaw origins, their influences on carbon cycling are strongly differentiated (Fig. 5a, d). Clarifying the mechanisms behind these differences is essential for robust predictions of alpine ecosystem feedback to climate change. Within this broader context, our results extend prior thermokarst research by providing multi-site, patch-resolved flux evidence for an RTS-specific single-peak trajectory in alpine grassland carbon balance.

Importantly, our current dataset does not adequately capture gas fluxes from RTS headwall areas, the most active zones of permafrost collapse where thawing of exposed ground ice drives rapid upslope retreat. In these newly collapsed areas, thaw-induced exceptionally high soil water content (Supplementary Fig. S17) prevents safe and valid collar-based measurements; similar practical constraints likely apply to prior collar-based studies in Alaska26. Outside the headwall areas, the RTS surfaces we monitored were generally well drained because of local topography and high evaporation rates typical of the alpine environment, whereas persistently saturated headwall areas likely sustain anaerobic microenvironments that can act as episodic CH4 sources. More broadly, our study focused on vertical ground-atmosphere exchanges of CO2 and CH4 over accessible patches and did not quantify lateral carbon export along paths of collapsed material movement and slump rill water. Such pathways can mobilize sediments and dissolved or particulate organic and inorganic carbon that bypass chamber-based measurements and are subsequently oxidized, transported, or buried downstream. Accordingly, the “carbon budget” here refers only to the seasonal CO2 and CH4 balance of the measured ground surface, not to a complete landscape carbon budget that integrates both vertical and lateral fluxes.

In summary, thermokarst landforms are both a visible manifestation and an accelerator of permafrost degradation, who drives pulses of greenhouse gas release that differ markedly from the gradually thaw of intact permafrost. Future research on thermokarst carbon cycling should prioritize: (1) year-round, in situ monitoring of greenhouse gas fluxes, particularly in hydrologically dynamic zones such as RTS headwalls, to capture seasonal and episodic emissions; (2) high-resolution mapping of thermokarst initiation and evolution, so that developmental stages are clearly defined and impacts can be quantified; and (3) integrated modeling of abrupt and gradual permafrost thaw processes. Advancements in these areas will significantly enhance predictive accuracy, inform targeted climate adaptation strategies, and support climate policy designed to mitigate the broader impacts of permafrost thaw. Given accelerating warming and permafrost degradation, such efforts are both urgent and essential.

Methods

Study region and representativeness

Field investigations were conducted at five RTS sites in the interior TP, spanning the Beiluhe Basin to the Fenghuoshan Mountains (Fig. 1). The region is characterized by continuous, ice-rich permafrost with volumetric ice contents of 30–50% at elevations from 4700 to 5100 m. According to long-term observations from the Qinghai-Beiluhe Plateau Frozen Soil Engineering Safety National Observation and Research Station (Beiluhe Station) during 2004–2024, regional air temperature increased by 0.38 °C per decade, accompanied by a precipitation increase of 67.3 mm per decade. Permafrost degradation occurred concurrently, with active layer thickness (ALT) increasing by 58.2 cm per decade and mean annual ground temperature (MAGT) rising by 0.22 °C per decade. Thermokarst activity across the Plateau has intensified, including a 41.36% increase in thermokarst lake area and an 8.58% increase in lake number from 1988 to 2020 within 5 km on either side of the Qinghai-Tibet Highway (QTH)33. The number of RTS near the QTH also increased by more than elevenfold from 2008 to 202116.

To evaluate geographic representativeness, we overlaid our sites on a recent inventory of 3805 RTS mapped in 2016 to 202254 (Supplementary Fig. S18). A 250 km by 250 km interior window along the QTH contains 2349 RTS, about 61.7% of the inventory, while accounting for less than 3% of the Plateau area. Our five sites fall within this interior core of RTS activity. Sites in this corridor were selected because the corridor coincides with continuous, ice-rich permafrost and typical alpine grassland where topography and ground-ice conditions favor slump formation. Repeated collar-based flux monitoring also requires safe and reliable access, which is difficult at many remote, roadless slumps. This site-selection rationale is consistent with established practice for thermokarst carbon studies that relies on repeated observations at a limited number of representative sites on the TP37,39,50 and in the Arctic25,26.

Environmental comparability further supports representativeness. Regional mean annual air temperature (MAAT) along the permafrost belt of the QTH spans about −5.6 to −1.7 °C and mean annual precipitation (MAP) about 397–829 mm55,56; our sites experience MAAT of −6 to −3.4 °C and MAP of 300–400 mm57,58. Soils are Gelisols59 with sandy-clay to sandy-loam textures that are widespread across the Plateau’s frozen-soil domain42. Vegetation is dominated by alpine steppe and alpine meadow60,61, the two principal types across the TP permafrost region42. All five sites occur in continuous, ice-rich permafrost8 (Fig. 1b) with ALT between 1.6 and 2.2 m48, which is consistent with the Plateau-wide average of about 2.3 m and within the broader regional range where roughly 80% fall between 0.8 and 3.5 m62. Site-level MAGT span −0.3 to −3.5 °C, corresponding mainly to sub-stable and transitional stability classes that together comprise a large fraction (~52.5%) of Plateau permafrost63. These comparisons indicate that our sites are environmentally representative of the interior TP permafrost zone.

Substrate conditions are also within regional ranges. To assess substrate representativeness, we compared topsoil SOC, TN, C/N, and pH with published values for thaw slumps and permafrost soils on the Plateau (Supplementary Table S3). Across the five sites, SOC at 0–15 cm ranged from 5.8 to 34.5 g kg−1, TN at 0–15 cm ranged from 0.87 to 2.82 g kg−1, the C/N ratio at 0–15 cm was 5.6 to 12.2, and pH at 0–10 cm was 6.7 to 8.0. These values fall within published ranges at comparable depths, supporting the broader applicability of our flux-based interpretations on the TP.

RTS investigation

The initial year of each RTS was confirmed through analysis of satellite imagery, field observations, and communications with local residents. Following each monthly gas flux measurement campaign, drone surveys were conducted at each RTS site using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with RGB (DJI Zenmuse X5 on DJI Matrice 210) and multispectral cameras (DJI Phantom 4 Multispectral). Orthophoto mosaics and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) maps derived from drone images were processed using PIX4Dmapper software (v4.3.31). Areas of disturbed ground patches within each RTS were delineated by visual inspection using a handheld GPS. The processed drone images, NDVI data, and GPS-derived disturbed ground patch boundaries were integrated and analyzed in QGIS (v3.22, OSGeo) to quantify the spatial extent of all morphological patch types.

Measurement of gas flux

Gas fluxes (ER, NEE, CH4 flux) were measured monthly during the 2024 growing season (May-October) using the static closed-chamber method. GPP was calculated as the difference between ER and NEE.

Each RTS site was classified into four patch types based on disturbance characteristics: control (CO), exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR), and disturbed ground (DG) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Control, exposed, vegetated raft, and the additional category of drape have been described previously in RTS-affected areas of the Arctic26; DG is defined here to reflect the actual field conditions on the TP (Supplementary Fig. S19). Control represents undisturbed areas located at least 5 m beyond any visible RTS disturbance. Exposed is defined as nearly bare ground with no vegetation or only sparse, scattered plants insufficient to form an established plant community, typically situated in the upper and middle portions of the slump. These surfaces are primarily mineral soils exposed after removal of the organic layer during slump formation. In occasional cases, sliding or rolling rafts exposed previously buried organic layers, which we grouped with exposed patches due to their indistinguishable appearance in the field. Vegetated raft consists of detached ground fragments that largely preserve the original vegetation mat and occur mainly in upper and middle sections of the slump. Disturbed ground occurs mainly near the slump toe where sliding and compression create gently undulating, but largely intact, vegetated surfaces. Disturbed ground is common on the TP because active layers are generally thicker here48; compression at the toe can deform but not overturn the vegetation mat. Comparable disturbed ground in RTS have not been reported in Arctic regions where thinner active layers26,46,47 are unlikely to produce this morphology. A minor additional category, drape, resembles vegetated raft but remains partly attached to surrounding unsubsidized ground. Drape patches accounted for only 0.44–1.31% of total RTS area and were excluded from flux measurements due to the difficulty of installing collars, although they were mapped for area statistics.

In 2024, 38 measurement plots across the four patch types with side lengths ranging from 5 to 15 m depending on slump size were established at the five RTS sites. Each plot was equipped with five replicate metal collars with grooves on top (square base, 18.5 cm side length) installed before April 2024 (Supplementary Figs. S1–S5, Supplementary Table S2).

Gas sampling was conducted monthly (08:00–12:00 local time). Five clear Plexiglas chambers (internal volume: 16.06 L) were sealed onto collars via a water-filled groove ensuring an airtight seal. Chamber air was sequentially sampled into pre-evacuated multilayer foil bags (200 ml, Delin Gas Packing, Dalian, China) using an automated sampling device over 11 min (five samples per collar). Prior to each sampling, chamber air was circulated for 1 min to homogenize internal air. Internal temperature and pressure were recorded (UT330C, Uni-Trend Technology, Dongguan, China). Laboratory gas chromatography analyses were performed using an Agilent 8860 GC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). ER and CH4 fluxes were measured using opaque covers to inhibit photosynthesis; transparent chambers (94% PAR transmittance, measured by SM206-PAR, Sanpometer, Shenzhen, China) were used for NEE measurements. Concurrently, ground temperature (10 cm depth), volumetric water content, pH and salinity (0–10 cm depth) around each collar were measured using a portable sensor (LD-WSYP, Leaneed Technology, Weifang, China) between 09:00-10:00 local time.

Gas fluxes were calculated according to an established equation64 and with temperature and pressure corrections:

Where F is gas flux (mg m−2 h−1), \(\rho\) is gas density (mg m−3), V is inner chamber volume (m3), A is collar-enclosed ground area (m2), P and T are average pressure (hPa) and temperature (K) inside the chamber during sampling, respectively; To (273.15 K) and Po (1013.25 hPa) are the standard temperature and pressure, and \(\frac{dC_{t}}{dt}\) is gas concentration change rate (ppm h−1). Fluxes were measured repeatedly on the same collars each month in the 2024 growing season; concentration time points within an 11-min chamber closure were used to fit the flux slope and are not independent samples. For ease to compare with other studies, gas flux units were finally converted to μmol gas m−2 s−1 (for CO2 fluxes) and nmol gas m−2 s−1 (for CH4 flux).

Calculation of seasonal carbon budgets

For each RTS site, monthly measured CO2 fluxes (NEE) were averaged by patch type and multiplied by their corresponding areas to obtain monthly carbon budgets. Summing these monthly budgets from May to October 2024 yielded the seasonal carbon budget for each patch type. The total seasonal carbon budget for each RTS was then calculated as the sum of seasonal carbon budgets across disturbed patch types (exposed, vegetated raft, and disturbed ground). For comparative purposes, seasonal carbon budgets for undisturbed alpine grassland were computed using averaged monthly NEE values measured in all control patches, scaled to match the combined area of the disturbed patches (excluding drape patches). Negative values indicate net carbon uptake (carbon sink), whereas positive values indicate net carbon emission (carbon source). In this study, daily NEE was approximated using values measured during 8:00–12:00 AM, following a simplified calculation method justified by previous methodological and empirical studies demonstrating high consistency between morning measurements and daily averages, typically with errors ranging from 5 to 15%65,66,67,68.

Soil and vegetation investigations

Soil and vegetation surveys were conducted in July 2024. Because near-surface horizons contain the processes that dominate chamber-measured CO2 and CH4 exchange, including root respiration, microbial decomposition, and rapid post-disturbance changes in moisture and vegetation69,70,71,72, we focused our soil measurements on the shallow profile most relevant to surface fluxes. Soil was sampled at two depth intervals (0–15 cm, 15–30 cm). Five individual soil cores were taken around the installed collars using an auger in each plot, then weighed and combined in equal proportions to form a representative composite sample. These were one-time composite samples per plot and are treated as independent samples. Depending on plot size, one to four composite soil samples per plot were collected, stored frozen, and transported to the laboratory. In the laboratory, Samples were air-dried, homogenized and sieved (2 mm mesh), and analyzed for TC content using an elemental analyzer (Vario MACRO cube; Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). SOC content was determined using the Walkley-Black method, involving potassium dichromate digestion followed by ferrous sulfate titration. For exposed patches, POC content was additionally measured using the Walkley-Black method after isolating the particulate fraction by sieving samples through a 0.53 μm mesh. Soil texture was analyzed using a Malvern Masterizer 2000 (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK), after organic matter and carbonate removal with 30% H2O2 and 30% HCl. Soil natural density, bulk density and gravimetric water content were determined using cutting-ring sampling and oven-drying methods. Water-filled pore space (WFPS) was calculated as:

where \(WFPS\) is soil water-filled pore space (%), \(SWC\) is soil gravimetric water content (g g−1), \(BD\) is soil bulk density (g cm−3) and \(PD\) is soil particle density assumed to be 2.65 g cm−3. Vegetation surveys in each plot documented plant population structure, coverage, and biomass (aboveground, and belowground at 0–10 cm and 10–30 cm depths).

Soil microbial analysis

Soil microbial samples (0–15 cm depth) were collected at FN and FS sites once in August 2024 near installed collars using sterile augers. Samples were subsampled, aseptically homogenized, frozen, and stored at −80 °C before DNA extraction. DNA extraction was performed using the PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, USA). Bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 regions were amplified with primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′); archaeal V4-V6 regions used primers 524F10extF (5′-TGYCAGCCGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and Arch958RmodR (5′-YCCGGCGTTGAVTCCAATT-3′). PCR utilized TransStart Fastpfu DNA polymerase (TransGen Biotech, China) on an ABI GeneAmp 9700 thermal cycler. PCR products were confirmed (2.0% agarose gel), purified (AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit, Axygen, USA), quantified (QuantiFluor-ST, Promega, USA), pooled, and prepared into sequencing libraries (TruSeq kit, Illumina, USA), followed by Illumina HiSeq paired-end sequencing.

Reads were quality-filtered using Cutadapt73, denoised using the DADA2 plugin in QIIME 274,75, classified using the SILVA 138 reference database via the QIIME 2 classify-sklearn algorithm with default settings, removing singletons and mitochondrial contaminants. Final bacterial and archaeal taxonomy tables were generated from domain to species level. Functional annotation was performed using the Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX) database following established protocols76, restricting to experimentally validated taxa. Functional group relative abundances were computed (total-sum-scaling of annotated ASVs), focusing on methanogenic and methylotrophic archaea, and methanotrophic bacteria.

Statistical analyses

Linear regressions were used to assess regional trends in air temperature and precipitation, as well as changes in key permafrost parameters, including active layer thickness and mean annual ground temperature. All hypothesis tests were two-sided with α = 0.05. Residual normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and Q-Q plots, and homoscedasticity with Levene’s test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests was used to evaluate differences in soil carbon stocks and gas fluxes among groups at a significance level of P < 0.05. To explore pathways by which RTS affects CO2 fluxes (ER and GPP), we employed partial least-squares path modeling (PLS-PM). Unless noted, summary values are reported as mean ± SE. Boxplots show median, interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers of 1.5 IQR. For ANOVA we report P value and Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons. For regressions we report the R2, P, and 95% confidence intervals for fitted lines. For PLS-PM we report R2 and Goodness-of-Fit (GOF).

Prior to path modeling, we screened continuous predictors for multicollinearity. We computed variance inflation factors (VIF) for 14 continuous variables: sand content (0–15 cm), natural density (0–15 cm), bulk density (0–15 cm), water-filled pore space (0–15 cm), aboveground biomass, belowground biomass (0–10 cm and 10–30 cm), NDVI, SOC, TN, soil moisture (0–10 cm), ground temperature (10 cm), soil salinity (0–10 cm), and pH (0–10 cm). Some variables with VIF greater than 5 were excluded to avoid unstable path estimates, including natural density, water-filled pore space, and TN. The screening procedure is documented with a correlation heat map annotated by VIFs (Supplementary Fig. S20). The remaining continuous predictors were organized into six endogenous latent blocks based on ecological relevance: soil moisture (volumetric water content at 0–10 cm), ground temperature (10 cm depth), soil chemical properties (salinity and pH at 0–10 cm), soil physical properties (sand content and bulk density at 0–15 cm), substrate availability (SOC at 0–15 cm; normalized within each RTS site), and vegetation (NDVI, aboveground biomass, belowground biomass at 0–10 cm and 10–30 cm). Together with two categorical factors, these blocks formed the full model. Patch type (exposed (EX), vegetated raft (VR), disturbed ground (DG), control (CO)) and RTS age (5, 6, 7, and 8 years) were upstream exogenous factors that influence intermediate latent variables and ultimately ER and GPP. All numeric variables were standardized prior to modeling to remove scale effects. Path relationships were defined based on ecological logic. Model performance was evaluated using the GOF index. Data preprocessing and PLS-PM analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.2; R Core Team, 2023) with the stats and plspm packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information and from the figshare data repository https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30391033. The raw bacterial sequence data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation under accession code CRA032711. The raw archaeal sequence data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation under accession code CRA032712. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No custom code or algorithms were developed for this study. Analyses were conducted in R (v4.3.2) using standard packages as described in Methods. No additional code files are required to reproduce the results.

References

Obu, J. et al. Northern Hemisphere permafrost map based on TTOP modelling for 2000-2016 at 1 km2 scale. Earth Sci. Rev. 193, 299–316 (2019).

Gruber, S. Derivation and analysis of a high-resolution estimate of global permafrost zonation. Cryosphere 6, 221–233 (2012).

Hugelius, G. et al. Estimated stocks of circumpolar permafrost carbon with quantified uncertainty ranges and identified data gaps. Biogeosciences 11, 6573–6593 (2014).

Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature 520, 171–179 (2015).

Kuang, X. & Jiao, J. J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 3979–4007 (2016).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Hugelius, G. et al. Permafrost region greenhouse gas budgets suggest a weak CO2 sink and CH4 and N2O sources, but magnitudes differ between top-down and bottom-up methods. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy. 38, e2023GB007969 (2024).

Zou, D. et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 11, 2527–2542 (2017).

Ran, Y. et al. New high-resolution estimates of the permafrost thermal state and hydrothermal conditions over the Northern Hemisphere. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 865–884 (2022).

Treat, C. C. et al. Tundra landscape heterogeneity, not interannual variability, controls the decadal regional carbon balance in the Western Russian Arctic. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5188–5204 (2018).

Siewert, M. B., Lantuit, H., Richter, A. & Hugelius, G. Permafrost Causes Unique Fine-Scale Spatial Variability Across Tundra Soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy. 35, e2020GB006659 (2021).

Nitzbon, J. et al. Fast response of cold ice-rich permafrost in northeast Siberia to a warming climate. Nat. Commun. 11, 2201 (2020).

Miner, K. R. et al. Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 3, 55–67 (2022).

Olefeldt, D. et al. Circumpolar distribution and carbon storage of thermokarst landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 13043 (2016).

Lewkowicz, A. G. & Way, R. G. Extremes of summer climate trigger thousands of thermokarst landslides in a High Arctic environment. Nat. Commun. 10, 1329 (2019).

Luo, J. et al. Inventory and Frequency of Retrogressive Thaw Slumps in Permafrost Region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099829 (2022).

Anthony, K. W. et al. 21st-century modeled permafrost carbon emissions accelerated by abrupt thaw beneath lakes. Nat. Commun. 9, 3262 (2018).

Turetsky, M. R. et al. Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw. Nat. Geosci. 13, 138–143 (2020).

Natali, S. M. et al. Permafrost carbon feedbacks threaten global climate goals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2100163118 (2021).

Turetsky, M. R. et al. Permafrost collapse is accelerating carbon release. Nature 569, 32–34 (2019).

Anthony, K. W. et al. Methane emissions proportional to permafrost carbon thawed in Arctic lakes since the 1950s. Nat. Geosci. 9, 679–682 (2016).

Matthews, E., Johnson, M. S., Genovese, V., Du, J. & Bastviken, D. Methane emission from high latitude lakes: methane-centric lake classification and satellite-driven annual cycle of emissions. Sci. Rep 10, 12465 (2020).

Ramage, J. et al. The Net GHG Balance and Budget of the Permafrost Region (2000-2020) From Ecosystem Flux Upscaling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 38, e2023GB007953 (2024).

Beamish, A., Neil, A., Wagner, I. & Scott, N. A. Short-term impacts of active layer detachments on carbon exchange in a High Arctic ecosystem, Cape Bounty, Nunavut, Canada. Polar Biol. 37, 1459–1468 (2014).

Jensen, A. E., Lohse, K. A., Crosby, B. T. & Mora, C. I. Variations in soil carbon dioxide efflux across a thaw slump chronosequence in northwestern Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 025001 (2014).

Abbott, B. W. & Jones, J. B. Permafrost collapse alters soil carbon stocks, respiration, CH4, and N2O in upland tundra. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 4570–4587 (2015).

Mu, C. et al. Editorial: Organic carbon pools in permafrost regions on the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau. Cryosphere 9, 479–486 (2015).

Mu, C. et al. Acceleration of thaw slump during 1997-2017 in the Qilian Mountains of the northern Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Landslides 17, 1051–1062 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Contrasting characteristics, changes, and linkages of permafrost between the Arctic and the Third Pole. Earth Sci. Rev. 230, 104042 (2022).

Ran, Y., Li, X. & Cheng, G. Climate warming over the past half century has led to thermal degradation of permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Cryosphere 12, 595–608 (2018).

Zhao, L. et al. Investigation, Monitoring, and Simulation of Permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: A Review. Permafr. Periglac. 35, 412–422 (2024).

Luo, J., Niu, F., Lin, Z., Liu, M. & Yin, G. Recent acceleration of thaw slumping in permafrost terrain of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: An example from the Beiluhe Region. Geomorphology 341, 79–85 (2019).

Zhou, G. et al. Accelerating thermokarst lake changes on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 14, 2985 (2024).

Kokelj, S. V. & Jorgenson, M. T. Advances in Thermokarst Research. Permafr. Periglac. 24, 108–119 (2013).

Yang, G. et al. Changes in Methane Flux along a Permafrost Thaw Sequence on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 1244–1252 (2018).

Wang, G. et al. Divergent Trajectory of Soil Autotrophic and Heterotrophic Respiration upon Permafrost Thaw. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 10483–10493 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Large methane emission during ice-melt in spring from thermokarst lakes and ponds in the interior Tibetan Plateau. Catena 232, 107454 (2023).

Yang, G. et al. Characteristics of methane emissions from alpine thermokarst lakes on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 14, 3121 (2023).

Mu, C. et al. Methane emissions from thermokarst lakes must emphasize the ice-melting impact on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 16, 2404 (2025).

Mu, M. et al. Thermokarst lake drainage halves the temperature sensitivity of CH4 release on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Nat. Commun. 16, 1992 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Distribution of soils and landform relationships in the permafrost regions of Qinghai-Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 60, 2216–2228 (2015).

Wang, Z. -w et al. Mapping the vegetation distribution of the permafrost zone on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 13, 1035–1046 (2016).

Luo, S., Wang, J., Pomeroy, J. W. & Lyu, S. Freeze-Thaw Changes of Seasonally Frozen Ground on the Tibetan Plateau from 1960 to 2014. J. Clim. 33, 9427–9446 (2020).

Weintraub, M. & Schimel, J. Interactions between carbon and nitrogen mineralization and soil organic matter chemistry in arctic tundra soils. Ecosystems 6, 129–143 (2003).

Oberbauer, S. F. et al. Tundra CO2 fluxes in response to experimental warming across latitudinal and moisture gradients. Ecol. Monogr. 77, 221–238 (2007).

Hinzman, L., Goering, D. & Kane, D. A distributed thermal model for calculating soil temperature profiles and depth of thaw in permafrost regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 28975–28991 (1998).

Bockheim, J. G. Importance of cryoturbation in redistributing organic carbon in permafrost-affected soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71, 1335–1342 (2007).

Wu, Q., Hou, Y., Yun, H. & Liu, Y. Changes in active-layer thickness and near-surface permafrost between 2002 and 2012 in alpine ecosystems, Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau, China. Glob. Planet. Change 124, 149–155 (2015).

Yuan, Z.-Q. et al. Responses of soil organic carbon and nutrient stocks to human-induced grassland degradation in a Tibetan alpine meadow. Catena 178, 40–48 (2019).

Yang, G. et al. Phosphorus rather than nitrogen regulates ecosystem carbon dynamics after permafrost thaw. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5818–5830 (2021).

Zheng, Z. et al. Partial offset of soil greenhouse gases emissions by enhanced vegetation carbon uptake upon thermokarst formation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf340 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. High methane emissions from thermokarst lakes on the Tibetan Plateau are largely attributed to ebullition fluxes. Sci. Total Environ. 801, 149692 (2021).

Mu, C. et al. High carbon emissions from thermokarst lakes and their determinants in the Tibet Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2732–2745 (2023).

Xia, Z. et al. Widespread and rapid activities of retrogressive thaw slumps on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 2016 to 2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109616 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. TPHiPr: a long-term (1979–2020) high-accuracy precipitation dataset (1/30∘, daily) for the Third Pole region based on high-resolution atmospheric modeling and dense observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 621–638 (2023).

Fu, Z. et al. Non-temperature environmental drivers modulate warming-induced 21st-century permafrost degradation on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 16, 7556 (2025).

Yin, G., Niu, F., Lin, Z., Luo, J. & Liu, M. Effects of local factors and climate on permafrost conditions and distribution in Beiluhe basin, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 581, 472–485 (2017).

Jiang, G. et al. Development of a rapid active layer detachment slide in the Fenghuoshan Mountains, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Permafr. Periglac. 33, 298–309 (2022).

US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Keys to Soil Taxonomy (US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2003).

Wang, G., Li, Y., Wu, Q. & Wang, Y. Impacts of permafrost changes on alpine ecosystem in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. China Ser. D. 49, 1156–1169 (2006).

Yuan, Z.-Q., Epstein, H. & Li, G.-Y. Grazing exclusion did not affect soil properties in alpine meadows in the Tibetan permafrost region. Ecol. Eng. 147, 105657 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al. Numerical modeling of the active layer thickness and permafrost thermal state across Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 11,604–611,620 (2017).

Cheng, G. et al. Characteristic, changes and impacts of permafrost on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 2783–2795 (2019).

Rolston, D. Gas flux. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part I. Physical and Mineralogical Methods, Agronomy Monograph (ed. Klute, A.) (American Society of Agronomy, Inc. and Soil Science Society of America, Inc., 1986).

Reichstein, M. et al. On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration:: review and improved algorithm. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 1424–1439 (2005).

Sims, D. et al. Midday values of gross CO2 flux and light use efficiency during satellite overpasses can be used to directly estimate eight-day mean flux. Agric. Meteorol. 131, 1–12 (2005).

Papale, D. et al. Towards a standardized processing of Net Ecosystem Exchange measured with eddy covariance technique: algorithms and uncertainty estimation. Biogeosciences 3, 571–583 (2006).

Moffat, A. M. et al. Comprehensive comparison of gap-filling techniques for eddy covariance net carbon fluxes. Agric. Meteorol. 147, 209–232 (2007).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006).

Jochheim, H. et al. Dynamics of soil CO2 efflux and vertical CO2 production in a European Beech and a Scots Pine forest. Front. Glob. Change 5, 826298 (2022).

Le Mer, J. & Roger, P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: a review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 37, 25–50 (2001).

Wordell-Dietrich, P. et al. Vertical partitioning of CO2 production in a forest soil. Biogeosciences 17, 6341–6356 (2020).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353, 1272–1277 (2016).

Obu, J., Westermann, S., Kääb, A. & Bartsch, A. Ground Temperature Map, 2000-2016, Northern Hemisphere Permafrost (PANGAEA, 2018).

Qi, S. Topographic data of Qinghai Tibet Plateau (2021) (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF0801903, G.J.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371141, G.J.), and the Gansu Science and Technology Programme (23JRRA641, S.G.). We thank Jie Zhang, Ziheng Chen, Pengpeng Yang, Zhanxian Lei, Chao Liu, Zhengtao Wu, Jianwei Wang, Baoping Huang, Guilong Wu, Hongting Zhao, Yali Liu and Shouji Pang for their assistance with fieldwork at high altitude; this study would not have been possible without their support. We are grateful to Jing Luo, Gaosen Zhang, Xiaodong Wu, Zhongqiong Zhang, Xinyue Zhong, Lei Wang, Zhiqiang Wei, Qian Xu, and Hao Cui for information support, and to Professor Yongzhi Liu, Professor Yu Sheng, Ruixia He and Zhiheng Du for assistance with data acquisition and instrumentation. We also thank Professor Cunde Xiao for project coordination and Ziyun Wu for contributions to the conceptual figure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.J. and Q.W. conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. G.J., Q.W., Z.F., L.W., X.M., Y.Z.Y., Y.H.Y. and B.E. contributed to scientific discussions and manuscript revisions. G.J., X.M., S.G., L.Z. and Z.F. prepared the figures. G.J., Z.F., X.M. and L.Z. conducted laboratory analyses and data processing. G.J., X.M., L.Z. and W.H. contributed to data interpretation. G.J., Q.W., Z.F., X.M., L.Z., L.W. and W.D. carried out the field investigations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, G., Men, X., Fu, Z. et al. Thaw slumps alter ecosystem carbon budget in alpine grassland on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat Commun 17, 190 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66869-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66869-4