Abstract

AlphaFold2 (AF2) revolutionized protein structure prediction, yet it is often conflated with the protein folding problem. Structure prediction seeks a static conformation, whereas folding concerns the dynamic process of structure formation. We challenge the current status quo, showing that AF2 has implicitly learned some folding principles. Its learned biophysical energy function, though imperfect, enables rapid discovery of folding pathways within minutes. Operating AF2 without multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) or templates forces sampling across its entire energy landscape, akin to ab initio modeling. Among over 7000 proteins, a fraction folds from sequence alone, highlighting the smoothness of AF2’s learned surface. Iterating and recycling predictions uncover intermediate structures consistent with experiments, suggesting a “local-first, global-later” mechanism. For designed proteins with optimized local interactions, AF2’s landscape becomes too smooth to reveal intermediates. These findings illuminate what AF2 has learned and open avenues for probing protein folding mechanisms and experimental intermediates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AlphaFold2 (AF2) revolutionized the protein structure prediction field1. Its success has led to an array of applications, and assessment of the transferability to other problems such as protein-protein and protein-peptide prediction2,3,4. Some efforts have focused on assessing the limits and understanding what AF2 has learned to increase its versatility and applicability. For instance, modifying multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) leverages different co-evolutionary signals in AF2 to identify multiple biologically relevant states5,6,7. AF2 was prevalent in CASP15 (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction) for single protein structure prediction, where differences in prediction accuracy were primarily due to the quality of MSAs used within AF28. AF2’s performance has lead many to question whether the protein folding problem has been solved9,10,11.

While the protein structure prediction problem focuses on generating static images of a protein’s folded state, the protein folding problem seeks to understand the dynamic processes involved in folding, including the pathways and intermediates that occur. Experimentally characterizing these folding pathways and intermediates is challenging due to the short transition times and the need for high-resolution data. Although computational methods based on physical and chemical principles offer a theoretical approach, they are limited by the accuracy of force fields and the extensive timescales required to simulate folding trajectories (as shown in Fig. 1, right). In this study, we explore the capability of AF2 beyond its traditional role in structure prediction, investigating its potential to provide insights into protein folding intermediates.

In physics-based approaches, extensive sampling is required to identify the native basin, whereas in AF2, MSAs or protein templates quickly guide structure refinement to narrower regions of conformational space, effectively bypassing other regions. We employ an AF2-ab initio approach, iteratively generating structures with the help of last round prediction to navigate the smooth energy function learned by AF2 starting from single sequence alone. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A recent study proposes that AF2 has learned an approximate biophysical energy function for structure prediction, where the co-evolutionary signal from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) is necessary to find a native conformation with low energy, and the structural module further provides refined structure predictions12. By back-propagating the structural loss and using gradient descent optimization to perturb the input sequence, the model can improve structure prediction accuracy without MSAs. This suggests that AF2 can act as an “energy minimizer” to iteratively improve the quality of the structure prediction. Previously, we observed that AF2 can detect the nuance of local interaction effect in alternating protein folding pathways for a set of four closely related proteins, in agreement with ϕ and ψ – value analysis data and extensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations13. Here, we propose that the predicted conformations along iterative structure predictions with AF2 could be representative of protein folding intermediates.

We first select a handful of proteins whose folding processes have been widely characterized by experiments and computer simulations – protein G, protein L, ubiquitin, and SH3. The original protein sequence is used to construct the sequence representation followed by an iterative structure prediction process. In the initial step of the iteration, neither template structure information nor MSAs are used. In subsequent iterations, the sequence information is combined with the last predicted structure as a template for next round prediction. As a further application of the methodology, we apply this protocol on the mutants of protein G and protein L to identify whether AF2 could detect changes in folding routes between the wild-type and mutant sequences. We then apply this protocol to designed sequences for these folds, showing that indeed they have smoother folding routes with less frustrations in AF2 compared to their original sequence. Finally, we assess the transferability of this approach by going beyond these six proteins and querying a large set of proteins representative of different folds and sizes from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)14.

Results

MSAs or templates can facilitate sampling AF2’s learned energy landscape

While MSAs remain a good way to navigate AF2’s learned energy surface, it is not necessarily the only way. For instance, testing a set of decoy structures into the model without co-evolutionary information showed discriminating behavior for structure quality12. This ability to forego MSAs and use structural data has also been applied to enhance prediction accuracy using single-sequence queries with a generator-discriminator approach. They first generate an AF2 structure prediction for the query sequence in the generator model, and predicted structure serves as the input of a discriminator model. The loss of discriminator model is then used by the generator model to update query sequence with gradient descent for the next round of prediction. In this way structures of higher quality from single sequence alone are generated.

Iteratively sampling AF2’s energy landscape slows down structure prediction, but can yield important insights into AF2’s folding funnel

Inspired by findings from this study12, we sought to evaluate the potential of AF2 for predicting folding intermediates through iteratively using query sequence and structure prediction. Here, AF2 predicts a structure from our single sequence query, and the prediction will be combined together with the sequence query for the next iteration (see Fig. 1, left). There are two routes in AF2 to achieve this. One is its internal recycling scheme which is a key design to gradually increase structure prediction accuracy1. Additionally, similar to how the template structure is processed in12, we can use the prediction from each round as distograms and combine it with pair representation from primary sequence to perform another prediction, which we call an iteration. Recycling and iteration steps can be used either independently or simultaneously. The prediction is repeated until the convergence of both structure prediction and its confidence scores. Thus, this approach foregoes the use of MSAs and focuses on examining AF2’s ability to navigate its learned energy surface from single sequence to the native state.

AF2 correctly predicts protein folding pathways for six small proteins

The structures generated along iterative prediction of AF2 for six small proteins (protein G, L and their mutants, ubiquitin, and the SH3 domain) are in excellent agreement with experimentally known intermediates and even transition states (see detailed description in Supplementary Discussion). Notably, the average pLDDT scores, which indicate prediction confidence, increased as the structures approached their native conformations. Another common trend across these proteins is that early intermediates with native-like regions exhibited low pLDDT scores, which increased as other structural elements fell into place, even though their conformations remained the same (see FigS. 2 and 3). Proteins G and L share a common topology despite of low sequence similarity and different folding pathways. Their mutants have different kinetics and the mutant of protein G even alternates folding pathways of its wild type. Our method revealed specific folding intermediates consistent with previous experiments and computational findings13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, demonstrating AF2’s capacity to capture intricate folding pathways. To assess AF2 predictions against experiments, we compared the order of native contact formation with experimental ψ-value analysis available for protein G and its mutant, protein L, and ubiquitin. In ψ-value analysis, a native contact is expected to appear in the transition state ensemble (TSE) when the ψ-value approaches 117. We therefore examined when each long-range native contact first appeared in AF2’s iterative predictions (see definition in the caption of Supplementary Fig. 1) and overlaid experimental ψ-values for the corresponding residue pairs. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the full heatmaps, while Supplementary Fig. 2A provides a direct comparison for the contacts with ψ-values. To qualitatively assess agreement, we used two thresholds: (1) on the folding-step axis, we considered the step at which each protein folded into a conformation best matching the experimental TSE; (2) on the ψ-value axis, given the inherent experiment uncertainties and the challenge to draw an exact line, we used 0.5 as an approximate cutoff to distinguish whether a contact is likely present in the TSE. Overall, across all four proteins, AF2’s predicted ordering of contact formation aligned well with experimental observation of TSE: contacts with high ψ-values (approaching 1) generally appeared just below the TSE folding step in AF2 (green points), whereas those with low ψ-values were typically observed later, above the TSE folding step (blue).

Each subplot represents predictions for each protein with increasing number of recycling for AlphaFold2 from 0 to 10. The structure predictions are shown for the iteration that finally finds the native state with the least recyclings. All structures before converging to the native and the structure at the 20th iteration aligned with the native (colored in gray) in that iteration are depicted (colored by pLDDT scores). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In protein G, the iterative structure predictions show a folding pathway starting with a native C-terminal hairpin formation, followed by a register-shifted N-terminal hairpin, before proceeding to find the native fold (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2B). We also found that AF2 is sensitive to sequence changes introduced in the mutant of protein G, folding through the N-terminal with a more locally favorable turn than the native sequence after designed mutations, in good agreement with experiments17. Similarly, protein L starts folding through the N-terminal hairpin first, with subsequent iterations gradually folding the C-terminal hairpin. Once again, AF2 detects a much smoother folding landscape for protein Lmut that follows a pathway similar to that of the original sequence20. Some subtle but important details about their folding pathways observed previously can be easily identified from our iterative predictions, such as the formation of a register-shifted N-terminal hairpin in the transition state which then refolds to the native protein G conformation17 and the folding of the C-terminal hairpin in a later step because of the low stability in its turn region for protein L20. Our findings also extend to ubiquitin and the SH3 domain, where AF2 successfully predicted folding intermediates that match known observations27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The AF2 folding pathway of ubiquitin exhibits the early formation of an N-terminal hairpin and samples different C-terminal conformations before establishing the correct end-to-end contacts that lead to the folded state – reflecting previous findings29,31. For the SH3 domain, the iterative method preserved the middle three β-strands early on, with N- and C-terminal native contacts forming later, aligned well with the low-populated, on-pathway folding intermediate observed in NMR (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2C)34.

Most α-helices in these systems are predicted to fold and unfold either fully or partially through MD simulations and are only stabilized once they pack against other native structural elements13. However, AF2 typically predicts these helices early on, even with low pLDDT scores (see Fig. 2 and 3). Such “overstabilization” of α-helix in AF2 was also reported in independent studies3.

The four wild-type proteins analyzed here belong to a well-characterized set of two-state folding proteins35. When extended to the full set, our analysis reveals that AF2 successfully predicts native-like conformations for approximately half of these proteins (see Supplementary Fig. 3). As with proteins G and L, folding trajectories exhibit notable heterogeneity even among proteins sharing conserved topologies. For example, Sso7d, a member of the SH3 fold family, follows a distinct folding trajectory. In contrast to the SH3 domain in our dataset, which lacks native N- and C-terminal contacts in the transition state ensemble (TSE) and only acquires them after the rate-limiting step, Sso7d initiates folding from a nucleus that excludes a structured N-terminal hairpin, which forms only later as the protein reaches its native conformation (see Supplementary Fig. 4). This variation is consistent with previous experimental ϕ-value analysis36.

Iterative structure predictions follow a “local first, global later” folding mechanism

One aspect of the protein folding problem explores whether a universal principle governs the folding patterns of most proteins, while also providing specific behavior for each unique sequence. Levinthal’s paradox suggests the existence of a physical principle that prevents the exploration of all possible conformations because the search process would be impractical timewise37. Folding funnels offer an explanation that folding happens as the free energy decreases while the remaining conformational space for searching is reduced38,39.

One common pattern from the above iterative structure predictions is that these six proteins tend to follow a “local first, global later” folding mechanism. We measure conformations predicted with this iterative approach by three metrics (see Fig. 4)–absolute contact order (ACO, a topological parameter that represents the average of native contact distance along sequence40,41), effective contact order (ECO, differs from ACO in that the native contact considers both spatial and sequence effects42), and the ratio of short and long range contacts (see “Methods”). The initial iterations favor local contacts, as seen by low ACO and ECO scores. This further leads to contacts that remain close in terms of ECO, but are higher in ACO. Effectively, once a contact is established, it brings residues that are far in the sequence (high ACO) close in space (low ECO), reducing the entropic penalty for conformational search process. The ratio of short and long range contacts delivers the same message that structure predictions favor short interactions in the beginning, which facilitates the formation of longer range contacts in later iterations.

For smaller proteins that fold, such as the widely studied fast-folding proteins, the peptide chain tends to follow a collapse-condensate mechanism, which shows the semi-folded structure resembles the final shape that was driven by hydrophobic collapse and others21. As the length of the protein sequence increases, the chance of establishing long-range interactions becomes smaller. Thus, short-range interactions that are more prevalent in the unfolded state can reduce conformational search space to assist the folding of the overall topology.

Generated sequences by ProteinMPNN encode smoother energy landscapes with more optimized local interactions than naturally occurring sequences

Machine learning models trained on existing knowledge of protein structures and sequences have been successful in predicting sequences given a desired template topology. Sequences generated from ProteinMPNN, for example, have high correlation between pLDDT from AF2 single sequence prediction and true LDDT-Cα against template structure43. The prevalence of more favorable local interactions in designed sequences over natural ones can be indicative that evolutionary pressure does not need to over-stabilize every local structure element.

To test this hypothesis, we predicted 20 sequences with ProteinMPNN based on the native structure for the six targets. For each one of them, we repeated the iterative structure prediction strategy. Supplementary Figs. 6–17 showcase our results for the evolution of pLDDT score and RMSD against the template backbone using AF2 models 1 and 2 during iterative structure predictions. For most of the sequences, AF2 is able to predict structures resembling the template topology after only a few iterations, independent of the number of recycles. The folding funnels are smooth enough that AF2 is able to predict the structures in a single leap, with no detected potential intermediates. Interestingly, RosettaFold was also found to predict the structures of de novo designed proteins with high accuracy from single sequences, despite differences in both its architecture and training data from AF244. Among the six targets, Protein G mutant presents the smoothest iterative predictions, where all 20 sequences rapidly found the conformation they were designed from. SH3 has a larger number of exceptions, where the number of recycles affects the iterative predictions, and we see more failures in predicting native-like structures. Similarly, we also see this happens in a few cases for the remaining proteins. However, future experiments are required to distinguish whether this is because they are failed sequence designs by ProteinMPNN or their native structure cannot be predicted with AF2 using our single sequence based approach.

Scaling AF2 iterative structure prediction to diverse protein folds

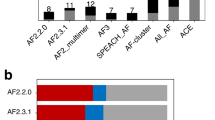

General principles of protein folding have been sought by theories and experiments for decades. Multiple factors were proposed in accurately predicting protein folding rates including contact order, packing compactness, and secondary structure compositions41,45,46,47. However, none of the existing models can provide the folding mechanism of each individual protein at atomistic level. Continuous development of computer simulation methods with ever-increasing computing power led to good agreement with experimental observations, but their capability is mostly limited to small globular proteins. We took one step further to scale our iterative structure prediction with AF2 on the known protein folds. The sequences were chosen from PDB by the following criteria: (1) we downloaded sequences of protein monomer structures deposited by March 5th, 2023 with length ranging from 30 to 250; (2) we filtered sequences whose deposited model has a resolution higher than 3 Å; (3) we clustered the remaining sequences using the easy-linclust tool provided in MMseqs2 with default options48. Overall, we collected 7418 sequences from the PDB to perform iterative structure prediction with AF2. For each sequence, we run iterative predictions with recyclings 0, 1, 3, 5, and 8 for 500 iterations. Figure 5A shows the first two dimensions of t-SNE embedding for our selected protein space after converting each native structure into a topology based feature vector using Gauss Integral49. This plot shows the diversity of selected protein folds in secondary structures and the ability of iterative structure prediction to correctly fold a small subset of sequences (success indicated by the final structure closer than 3 Å to the native state in the middle right plot of Fig. 5A). We also found that sequences sharing similar folds with SH3 and ubiquitin in PDB are close to each other in the embedding. Not surprisingly, AF2’s ability to fold proteins through an iterative approach is inversely proportional to protein size (Fig. 5B). In particular, for fragments below 50 residues, the success rate is around 20%, which helps explain AF2’s success in predicting the bound structure of peptides without MSAs3. However, for proteins over 100 residues, the success rate rapidly falls below 5%. Moreover, to directly test transferability, we examined proteins in our dataset released both before and after the AF2 training cutoff date (April 30th, 2018). The result shows that the success rate (fraction predicted within 3 Å RMSD) is indistinguishable between the two sets (background shaded gray vs. white, see Supplementary Fig. 18). We excluded data prior to 2000 due to the limited number of available structures, and the apparent drop in 2023 reflects that our collection only included entries released up to March 5th, 2023. We run predictions with both models that can take template structures in AF2 - models 1 and 2, which were fine-tuned with different number of extra sequences and training samples. We can see that the best structure prediction of each model after 500 iterations differs in terms of RMSD against their native structure for many targets (Fig. 5C). The secondary structure distribution of our curated subset from PDB shows several trends that can be representative of all protein structures in PDB: (1) the percentage of coil-like fragments that appear in this clustered subset is around 36%, (2) protein structures with all β-sheets are rare, and (3) most structures have α-helix between 0 ~40%, while structures with larger portions of α-helix are also frequent (see Fig. 5D). Naturally, as a trained model with structures in PDB, AF2 tends to predict well for α-helix rich structures but fails for structures with more coil fragments (see Fig. 5E). Such prediction bias towards α-helix in this large-scale prediction is consistent with our observation of their appearance during the early stage along iterative predictions above (Figs. 2,3).

A structural feature based t-SNE embedding plot colored based on four different properties: ratio of β-sheets (left) and α-helix (middle left) over the sum of both, sequences the AlphaFold2-ab initio folds to within 3 Å of native (middle right), and positions of SH3 (red) and ubiquitin (black) like proteins (right). B Histogram (blue): probability density for the length of all selected sequences. Line: the percentage of proteins folded into structure less than 3 Å from native decreases with longer sequences for both predictions by model 1 (red) and model 2 (gray). C Comparison of predictions from model 1 and 2 in terms of the lowest RMSD against native structure from all iterative predictions. D The percentage of secondary structure distribution of each type for all selected structures. E Percentage of proteins fold into structure less than 3 Å from native versus the amount of secondary structure for each type. F, G The lowest RMSD from iterative predictions for SH3 (F) and ubiquitin (G) like proteins by model 1 (red) and 2 (gray). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discovery of folding intermediates in SH3, ubiquitin-like proteins, and beyond

An intriguing aspect of the protein folding problem is determining whether proteins with the same fold share similar folding mechanisms. This can reveal whether differences in sequence lead to alternative folding pathways that converge on the same final conformation. In our study of proteins G, L, and their mutants, we observed that subtle sequence changes in protein G could enhance local interactions, altering the folding pathways from which the native conformation is achieved. In contrast, the folding pathway for protein L and its mutant remained consistent despite sequence variations. With the large-scale iterative predictions, we extended our investigation to other proteins with different folds. We discovered that structures with folds similar to SH3 and ubiquitin cluster closely together in structure-based embeddings (see Fig. 5A, right). However, despite sharing the same conformation overall (see their structural alignment in Supplementary Fig. 19), not all proteins within each fold type could be accurately predicted, and the two AF2 models produced differing results (see Fig. 5F, G). Among all SH3 and ubiquitin like proteins, only a few achieved conformations with less than 3 Å from the native structure. Despite low sequence similarity, these seven proteins appear to follow the same folding pathway as the SH3 protein we studied above (PDB entry: 2HDA), where the middle three β-sheets stack together first, awaiting the formation of interactions between the N- and C-terminal strands (Supplementary Fig. 20). Predictions from ubiquitin like proteins also demonstrate that they likely have similar folding intermediates where the first two β-strands tend to fold early on, followed by the assembly of native interactions at both termini (Supplementary Fig. 21). However, we are unsure whether those SH3 and ubiquitin-like proteins that did not find their native structure after iterative predictions fold in different pathways or also share similar folding patterns.

AF2 identifies differential stability in Fibronectin type III domain repeats

Fibronectin (FN) type III, a key component in extracellular matrices, is a 368 residue protein whose modular domain topology is foldable in AF2 through our current single sequence approach. FNIII is composed of four modules called repeats, numbered 7 to 10 (III7–10). Our iterative structure predictions with recycling number greater or equal to one obtain final structures in close agreement with the experimental structure50, with a small deviation in dihedrals between III7 and III8 (see Fig. 6A). Interestingly, AF2 finds significant differences in the folding of the different domains. With domain III7 finding the native structure rapidly (single iteration), while III8 and III10 remain partially folded, and III9 remains unfolded. In subsequent steps, both III8 and III10 fold, and so does most of the III9 repeat – but the overall assembly of the domains is incorrect, and AF2’s confidence score remains low. After a few more iterations, the linkers between III8–9 and III9–10 are accurately predicted, but the one between III7-8 (linker 1) keeps changing the orientation during later iterations without entering the native conformation. We hypothesize this is because the linker 1 region is more flexible than the other two linkers. Although detailed descriptions of the folding pathways for this four-repeat protein are not available, several studies have reported similar observations.

A Iterative structure predictions of Fibronectin type III with AlphaFold2 using different number of recycles. The repeat names and location of integrin binding loop containing RGD peptides are labeled. B The evolution of structure prediction in terms of residue wise pLDDT along representative iterations. The secondary structure classification of native structure is depicted above. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Experimental studies from51,52 indicate that III9 is the least stable one among the four repeats with equilibrium stability (ΔGf) of -1.2( ± 0.5) kcal mol−1 compared to -6.1( ± 0.1) kcal mol−1 for III10, and the loop region containing the sequences Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) from the III10 can bind integrin themselves. This aligns with our iterative predictions in that III9 is unstructured in the beginning and the last repeat to find native conformation while the RGD region remains flexible with low pLDDT scores throughout the iterative predictions. It has also been suggested that III9 and III10 act independently in that the mutations of one domain have no effect on the other53. Additionally, a thorough experimental study on the dynamics and stability of Fibronectin recently found that III7 appears to have no effect on the stability of the rest of modules since III7-10 and III8-10 are comparably stable while III8 was found to help stabilize III9 and III1054. Those experimental evidence help us explain why AF2 is able to come up with a conformation resembling the crystal structure despite of its long sequence length overall: (1) the folding of all four repeats are mostly driven by local interactions in each repeat, similarly for the linkers in between, and (2) the more stable repeat likely has more locally favorable interactions so III7 and III10 can be predicted early on while the least stable III9 folded at the end. This indicates that our iterative structure prediction can help provide the relative stability information among the Fibronectin repeats.

Discussion

Unraveling the protein folding process at an atomic level is critical for understanding protein functions and their roles in diseases. This task largely depends on two intertwined factors: a highly accurate energy function that describes intricate molecular interactions and efficient sampling methods that can quickly explore the vast conformational space of proteins, which have high degrees of freedom. Traditional computational simulations often struggle with inaccuracies in force fields and insufficient conformational sampling. Even when extensive sampling is achieved, distilling insights about protein folding pathways can be challenging, as some methods may bias the folding route (e.g., through restraints in MELD55 or the use of fragments in Rosetta56). Recovering statistically significant pathways is complex, as shown in our extensive studies of protein G, protein L, and their mutants using various MD simulation methods and others13,57,58.

Recent advancements have shown that the millions of trained parameters in AF2 can act as a sort of biophysical energy function that AF2 navigates to predict structure12. Our study aims to enhance our understanding of what AF2 has learned about protein structures and explore whether this learned energy surface can be leveraged to simulate the protein folding process. Unlike traditional physics-based methods (e.g., sampling along atomistic or coarse-grained force fields), AF2’s energy function appears to be smoother and more precise when native-like interactions are found. It has been particularly successful in using multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to identify regions of phase space for structure determination1,5,6,7, likely due to co-evolutionary information providing shortcuts to different conformational spaces.

A previous study examined whether structure prediction models, including AF2, can help enhance our understanding of the protein folding process. Their conclusion is none of them has predictive power for intermediate conformations and the folding rate constant59. However, by customizing ways of operating AF2, our results indicate that in the absence of MSAs, AF2 accurately captures the protein folding intermediates observed experimentally, resembling more of an ab initio approach. Not surprisingly, the structure prediction success rate decreases with increasing sequence length, a limitation in line with the success of ab initio methods like Rosetta, MELD, or UNRES60, which have been effective for sequences of similar lengths. Interestingly, AF2-ab initio is also successful for proteins composed of independently foldable domains despite their longer length with sequence alone, as the case of Fibronectin shows.

The folding pathways of proteins in AF2 seem to align with the “local-first, global-later” mechanism61,62. AF2 appears to first fold residue pairs that are nearby in sequence without MSAs, and then locks in structural elements as they get closer in space. When MSAs are unavailable, AF2 likely uses structural information from previous iterations to reduce conformational search space. However, this search becomes increasingly difficult as sequence length grows and more disordered regions are introduced. Additionally, AF2’s pLDDT scores, which reflect the confidence in predicted structures, improve as nearby residues become more native-like, suggesting that the per-residue pLDDT score reflects the quality of a fragment within the context of the entire protein. These observations suggest that AF2 is intrinsically tuned to a local-first folding strategy; as a result, it struggles to explore alternative pathways because finding distant nucleation sites would require far more sampling. When the native fold is already known, other approaches26,63 may offer solutions to explore alternative folding mechanisms.

From a technical point, we are using AF2 in a way that it was not designed to work (no MSAs), for a purpose that it was not intended (pathways and folding intermediates). It is unclear what is the right balance between iterations and recyclings and why it works on some protein sequences but not others. Using recycling alone is effective for the six small proteins, but it is slightly less efficient compared to using both together in some cases (Fig. 3). Of over 7000 proteins we tested, AF2 has higher success chances on the smaller proteins, and those with more secondary structure. However, we can see successful predictions distributed across the embeddings that represent diversity in terms of secondary structure and other properties (see Fig. 5). This is interesting in the sense that in the process of learning to predict protein structures, AF2 has learned something deeper about proteins that allows it to fold some small proteins in ways that are compatible with known findings. It is conceivable that future versions of such approaches will learn more and more about the protein folding principles.

In the broader context, evolution does not know about folding pathways or structures; it just has some selection requirements for actions to happen at particular time intervals with robustness and precision. Evolution does not optimize; it just needs things to be good enough. Optimizing interactions might lead to two proteins never unbinding, which might continuously express a gene or limit the release of oxygen into the blood. However, we as a field are learning the principles to optimize sequences that fold robustly and remain stable with tools such as ProteinMPNN. Several designed proteins were introduced in previous CASP events, typically performed well for physics-based ab initio methods. Part of it can be explained by optimized local interactions. Not surprisingly, such protein sequences perform very well for iterative prediction using AF2 without MSAs, folding with few or no apparent intermediates in the majority of cases.

The transient nature of intermediate states poses a challenge to their experimental characterization and limits our ability to quantify the predicted accuracy of AF2. Even when those intermediate states are well characterized, there is no single metric that can be used to demonstrate the prediction accuracy of protein folding process. Furthermore, for systems where intermediates are reported, the results are often qualitative, without atomic details. Hence, the lack of data and objective functions increase the challenge of building a machine learning model for predicting protein folding. Currently, AF2-ab initio could be a valuable tool for generating hypotheses about intermediates and guiding the placement of probes to experimentally verify or refute those hypotheses.

Methods

Absolute contact order, effective contact order and the ratio of short and long range contacts

A contact is defined by a residue pair rij whose pairwise distance dij < 6.5 Å. The set of residue pair distances D: {dij} are selected from native structure given this criterion and we calculate their pairwise distances for both native structure Dnative and each structure prediction Dprediction. Then absolute contact order ACO is defined as \({\overline{C({r}_{ij})}}_{\Delta {d}_{ij} < 0.5\,{\mathring{{{{\mathrm{A}}}}}}}\) for predicted structures based on the number of native contacts it formed compared to the native structure. Similarly, the effective contact order ECO is defined with a simplified version of64 where each effective contact order is the difference between their distance in sequence and the largest distance in sequence among all native contacts in between. The ratio of short and long range contact is approximated by the ratio between the number of native contacts less than 8 residues and more than 16 residues away, respectively. In addition, to balance that different secondary structures have varying adjacent residue distances, we weight each residue by their secondary structure type as the following: \(\frac{3.6}{5}=0.72\) Å for α-helix type since one helical turn has 5 residues with end-to-end distance roughly as 3.6 Å. Similarly, it’s \(\frac{7}{3}\simeq 2.3\) Å for β-strand type and we simply take the average of them for coil type.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Unless otherwise stated, all data supporting the results of this study can be found in the article, supplementary, and source data files. The data generated in this study including large scale iterative structure predictions using single sequence is available in Zenodo database and open for public to download from the following links: dataset_1 (https://zenodo.org/records/13829384), dataset_2 (https://zenodo.org/records/13788039), dataset_3 (https://zenodo.org/records/13766276), dataset_4 (https://zenodo.org/records/13766281), dataset_5 (https://zenodo.org/records/13777196), dataset_6 (https://zenodo.org/records/13772757). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scripts are distributed under a MIT license and can be found from here (https://github.com/PDNALab/AlphaFolding)65 to run iterative structure predictions with AlphaFold2 based on ColabDesign (https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabDesign). A Google Colab notebook version of the script is currently available at (https://github.com/ccccclw/ColabDesign/blob/main/af/examples/alphafolding.ipynb), which also provides an interface to download and visualize our large scale single sequence based iterative structure predictions.

References

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 1–11 (2021).

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2021).

Tsaban, T. et al. Harnessing protein folding neural networks for peptide-protein docking. Nat. Commun. 13, 176 (2022).

Chang, L. & Perez, A. Ranking Peptide Binders by Affinity with AlphaFold. Angewandte Chemie International Edition (2022).

Alamo, D. D., Sala, D., Mchaourab, H. S. & Meiler, J. Sampling alternative conformational states of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2. eLife 11, e75751 (2022).

Wayment-Steele, H. K. et al. Predicting multiple conformations via sequence clustering and AlphaFold2. Nature 7996, 832–839 (2023).

Schafer, J. W. & Porter, L. L. Evolutionary selection of proteins with two folds. Nat. Commun. 14, 5478 (2023).

Elofsson, A. Progress at protein structure prediction, as seen in CASP15. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 80, 102594 (2023).

Chen, S.-J. et al. Protein folds vs. protein folding: differing questions, different challenges. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214423119 (2023).

Thorp, H. H. Proteins, proteins everywhere. Science 374, 1415–1415 (2021).

Moore, P. B., Hendrickson, W. A., Henderson, R. & Brunger, A. T. The protein-folding problem: Not yet solved. Science 375, 507–507 (2022).

Roney, J. P. & Ovchinnikov, S. State-of-the-art estimation of protein model accuracy using AlphaFold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 238101 (2022).

Chang, L. & Perez, A. Deciphering the Folding Mechanism of Proteins G and L and Their Mutants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 32, 14668–14677(2022).

Berman, H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 (2000).

Nauli, S., Kuhlman, B. & Baker, D. Computer-based redesign of a protein folding pathway. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 602–605 (2001).

Nauli, S. et al. Crystal structures and increased stabilization of the protein G variants with switched folding pathways NuG1 and NuG2. Protein Sci. 11, 2924–2931 (2002).

Baxa, M. C. et al. Even with nonnative interactions, the updated folding transition states of the homologs Proteins G & L are extensive and similar. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 8302–8307 (2015).

Kim, D. E., Fisher, C. & Baker, D. A breakdown of symmetry in the folding transition state of protein L. J. Mol. Biol. 298, 971–984 (2000).

Yoo, T. Y. et al. The Folding Transition State of Protein L Is Extensive with Nonnative Interactions (and Not Small and Polarized). J. Mol. Biol. 420, 220–234 (2012).

Kuhlman, B., O’Neill, J. W., Kim, D. E., Zhang, K. Y. & Baker, D. Accurate computer-based design of a new backbone conformation in the second turn of protein L. J. Mol. Biol. 315, 471–477 (2002).

Lindorff-Larsen, K., Piana, S., Dror, R. O. & Shaw, D. E. How fast-folding proteins fold. Science 334, 517–520 (2011).

Lapidus, L. J. et al. Complex pathways in folding of protein G explored by simulation and experiment. Biophys. J. 107, 947–955 (2014).

Maity, H. & Reddy, G. Folding of protein L with implications for collapse in the denatured state ensemble. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2609–2616 (2016).

Maity, H. & Reddy, G. Transient intermediates are populated in the folding pathways of single-domain two-state folding protein L. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 165101 (2018).

Mitsutake, A. & Takano, H. Folding pathways of NuG2-a designed mutant of protein G-using relaxation mode analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 044117 (2019).

Bitran, A., Jacobs, W. M. & Shakhnovich, E. Validation of DBFOLD: an efficient algorithm for computing folding pathways of complex proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008323 (2020).

Sosnick, T. R., Dothager, R. S. & Krantz, B. A. Differences in the folding transition state of ubiquitin indicated by ψ and ϕ analyses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 101, 17377–17382 (2004).

Went, H. M. & Jackson, S. E. Ubiquitin folds through a highly polarized transition state. Protein Eng. Des. Selection 18, 229–237 (2005).

Krantz, B. A., Dothager, R. S. & Sosnick, T. R. Discerning the structure and energy of multiple transition states in protein folding using ϕ-analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 463–475 (2004).

Várnai, P., Dobson, C. M. & Vendruscolo, M. Determination of the transition state ensemble for the folding of ubiquitin from a combination of ψ and ϕ analyses. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 575–588 (2008).

Piana, S., Lindorff-Larsen, K. & Shaw, D. E. Atomic-level description of ubiquitin folding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5915–5920 (2013).

Grantcharova, V. P., Riddle, D. S. & Baker, D. Long-range order in the src SH3 folding transition state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7084–7089 (2000).

Riddle, D. S. et al. Experiment and theory highlight role of native state topology in SH3 folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1016–1024 (1999).

Neudecker, P. et al. Structure of an intermediate state in protein folding and aggregation. Science 336, 362–366 (2012).

Lawrence, C., Kuge, J., Ahmad, K. & Plaxco, K. W. Investigation of an anomalously accelerating substitution in the folding of a prototypical two-state protein. J. Mol. Biol. 403, 446–458 (2010).

Guerois, R. & Serrano, L. The SH3-fold family: Experimental evidence and prediction of variations in the folding pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 304, 967–982 (2000).

Levinthal, C. Are there pathways for protein folding? J. de. Chim. Phys. 65, 44–45 (1968).

Dill, K. A. Theory for the folding and stability of globular proteins. Biochemistry 24, 1501–1509 (1985).

Leopold, P. E., Montal, M. & Onuchic, J. N. Protein folding funnels: a kinetic approach to the sequence-structure relationship. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8721–8725 (1992).

Ivankov, D. N. et al. Contact order revisited: Influence of protein size on the folding rate. Protein Sci. 12, 2057–2062 (2003).

Ouyang, Z. & Liang, J. Predicting protein folding rates from geometric contact and amino acid sequence. Protein Sci. 17, 1256–1263 (2008).

Weikl, T. R. & Dill, K. A. Folding rates and low-entropy-loss routes of two-state proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 329, 585–598 (2003).

Dauparas, J. et al. Robust deep learning-based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 376, 49–56(2022).

Baek, M. & Baker, D. Deep learning and protein structure modeling. Nat. Methods 19, 13–14 (2022).

Plaxco, K. W., Simons, K. T. & Baker, D. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins11Edited by P. E. Wright. J. Mol. Biol. 277, 985–994 (1998).

Weikl, T. R., Palassini, M. & Dill, K. A. Cooperativity in two-state protein folding kinetics. Protein Sci. 13, 822–829 (2004).

Gromiha, M. & Selvaraj, S. Comparison between long-range interactions and contact order in determining the folding rate of two-state proteins: application of long-range order to folding rate prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 310, 27–32 (2001).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Røgen, P. & Fain, B. Automatic classification of protein structure by using Gauss integrals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 119–124 (2003).

Leahy, D. J., Aukhil, I. & Erickson, H. P. 2.0 Å crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell 84, 155–164 (1996).

Litvinovich, S. V. et al. Formation of amyloid-like fibrils by self-association of a partially unfolded fibronectin type III module11Edited by R. Huber. J. Mol. Biol. 280, 245–258 (1998).

Plaxco, K. W., Spitzfaden, C., Campbell, I. D. & Dobson, C. M. A comparison of the folding kinetics and thermodynamics of two homologous fibronectin type III modules11Edited by P. E. Wright. J. Mol. Biol. 270, 763–770 (1997).

Steward, A., Adhya, S. & Clarke, J. Sequence conservation in Ig-like Domains: the role of highly conserved proline residues in the fibronectin type III superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 318, 935–940 (2002).

Su, Y., Iacob, R. E., Li, J., Engen, J. R. & Springer, T. A. Dynamics of integrin α5β1, fibronectin, and their complex reveal sites of interaction and conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102323 (2022).

MacCallum, J. L., Perez, A. & Dill, K. A. Determining protein structures by combining semireliable data with atomistic physical models by Bayesian inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 6985–6990 (2015).

Leman, J. K. et al. Macromolecular modeling and design in Rosetta: recent methods and frameworks. Nat. Methods 17, 665–680 (2020).

Adhikari, U. et al. Computational estimation of microsecond to second atomistic folding times. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6519–6526 (2019).

Bogetti, A. T., Leung, J. M. G. & Chong, L. T. LPATH: a semiautomated Python tool for clustering molecular pathways. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling 63, 7610–7616 (2023).

Outeiral, C., Nissley, D. A. & Deane, C. M. Current structure predictors are not learning the physics of protein folding. Bioinformatics 38, btab881 (2022).

Czaplewski, C., Karczyńska, A., Sieradzan, A. K. & Liwo, A. UNRES server for physics-based coarse-grained simulations and prediction of protein structure, dynamics and thermodynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W304–W309 (2018).

Voelz, V. A. & Dill, K. Exploring zipping and assembly as a protein folding principle. Proteins 66, 877 – 888 (2007).

Rollins, G. C. & Dill, K. General mechanism of two-state protein folding kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11420 – 11427 (2014).

Ooka, K. & Arai, M. Accurate prediction of protein folding mechanisms by simple structure-based statistical mechanical models. Nat. Commun. 14, 6338 (2023).

Fiebig, K. M. & Dill, K. A. Protein core assembly processes. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 3475–3487 (1993).

Chang, L. & Perez, A. Source code of this work is accessible in Zenodo: Pdnalab/alphafolding. (2025).

Acknowledgements

A.P. and L.C. thank NIH-NIGMS for funding through grant R01GM149646-01 (A.P.). We are also thankful for the use of HiperGator computational resources at the University of Florida.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and A.P. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. L.C. performed all computations and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, L., Perez, A. Rapid estimation of protein folding pathways from sequence alone using AlphaFold2. Nat Commun 17, 170 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66870-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66870-x