Abstract

Voltage-controlled nanofiltration offers a promising approach for precise, on-demand molecular separation. However, its application in organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) remains underexplored, given the poor solute dissociation in organic solvents. Here, we fabricate conductive and robust conjugated microporous polymer (CMP) membranes to investigate voltage-controlled OSN. Our results show that while solvent permeance slightly decreases with the applied voltage, due to the uneven electron density distribution of solvent molecules, solute rejection is significantly enhanced. This enhancement arises from a dual-barrier mechanism comprising ion migration in the bulk solution and a Donnan-like equilibrium at the feed-membrane interface under an applied voltage. Specifically, in methanol, applying a positive voltage increases the rejection of positively charged methylene blue (MB) from 8.3 % at 0 V to 91.3 % at 5 V. Our study also reveals that the degree of solute dissociation contributes significantly to the effectiveness of voltage-controlled rejection. Lastly, the successful separation of mixed dyes of similar size, together with the enhanced rejection of real pharmaceutical and agrochemical compounds under applied voltage, highlights the potential of in-situ voltage application in OSN for addressing challenging separations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic solvent waste has emerged as one of the most critical challenges faced by the chemical and pharmaceutical industries1. Large quantities of organic solvents used as raw materials, solvents, or cleaning agents become waste during manufacturing processes1,2. The costs associated with the separation, recovery, or disposal of these high volumes of waste solvents can account for 40% to 80% of production expenses1,3,4. Compared to traditional separation processes, membrane-based organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) is an environmentally friendly and energy-efficient alternative that shows great promise in addressing this issue4,5,6,7.

In a typical nanofiltration (NF) membrane process, solute rejection depends not only on size sieving but also on electrostatic interactions via the Donnan effect4, which has been widely explored to enhance rejection. Two approaches for leveraging the Donnan effect include functionalizing membrane materials with ionic groups or applying electric voltage to conductive membranes to create voltage-gated membranes, with the latter offering a more direct, robust, rapid, reversible, and in situ controllable approach8,9,10,11. Both strategies have been extensively studied in aqueous NF. For example, Yi et al.9 demonstrated that the rejection of methyl orange (MO) in water increased from 27.2 ± 3.8% to 87.8 ± 3.1% when a voltage of 3 V was applied to an Mxene/carbon nanotube (CNT) membrane cathode. However, in the transition from aqueous NF to OSN, the role of the Donnan effect remains underexplored12,13, with limited experimental evidence linking solute rejection to surface charge in OSN tests using polyelectrolyte, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and ionic covalent organic framework (iCOF) membranes5,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Additionally, studies on voltage-gated OSN membranes are scarce, and the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood10,25. From the authors’ perspective, this gap is largely attributed to the reduced dissociation of solutes in organic solvents compared to water, raising concerns about the extent to which membrane surface charge can influence solute rejection.

The experimental study of ion dissociation in organic solvents dates back to 1899, when Jones measured the dissociation of electrolytes in various organic solvents, discovering that in alcoholic solvents, the dissociation degree of salts largely depends on the solvent’s dielectric constant26. Specifically, the dissociation degree of sodium iodide and sodium bromide in methanol can reach up to 60%. Later, Hartley et al.27 found that many acids, including HCl, HClO3, and HClO4, behave as strong electrolytes in methanol and ethanol. More recent experimental and simulation work on ion dissociation is primarily based on the theory that ion pairs exist in several equilibrium phases, including free ions, solvent-separated ion pairs (SSIPs), contact ion pairs (CIPs), and aggregates (AGGs)28,29. Free ions and SSIPs consist of fully solvated cations or anions, while in CIPs and AGGs, one or more solvent molecules in the primary solvation shell of the cation or anion are replaced by one or more counterions. The degree of dissociation is related to the relative populations of charged SSIPs and free ions versus non-charged CIPs and AGGs. It is primarily influenced by the physicochemical properties of the solute and solvent systems30,31. Although the second Wien effect describes the enhancement of ionization in weak electrolytes under electric fields in non-polar media32,33, this effect only becomes significant at extremely high field strengths (on the order of kV/cm)33,34. Therefore, in the absence of such strong external fields, the dissociation of solutes is mainly governed by the intrinsic properties of the solute and the organic solvent.

To achieve voltage-controlled OSN, we selected conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs), characterized by their extended π-conjugated skeleton and permanent microporosity, as the membrane material. These materials were chosen for their unique combination of electron conductivity and strong potential in OSN applications35,36,37,38,39. Feed solutions containing dyes of varying charges and sizes in different organic solvents were used to evaluate membrane rejection under applied voltage. Our findings reveal that membrane performance is highly influenced by the interplay between the applied voltage, solute structure, and solvent properties. Lastly, the model fitting in this work demonstrates that the responsive change in solute rejection with respect to the magnitude of the applied voltage can be effectively predicted.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of PTCB membranes

In this study, 1,3,5-tris(N-carbazolyl) benzene (TCB), featuring a phenyl core with three electroactive carbazole groups, was selected as the monomer for electropolymerization (see Fig. 1a). Our previous study revealed that it could form CMP membranes with a pore size of approximately 0.52 nm36,40. As shown in Fig. 1a, PTCB membranes were grown on the CNT/Nylon-66 supports using cyclic voltammetry (CV), scanned from 0 to 1.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The corresponding CV curve is shown in Fig. 1b. During the first anodic scan (Fig. S4), an oxidative peak appears at 1.22 V, corresponding to the oxidation of carbazole groups into radical cations. These radicals rapidly couple to form dimeric carbazole cations36,41. In the cathodic scan, the dimerized carbazole cations are reduced back to their neutral state, resulting in a reduction peak at 1.10 V. In subsequent cycles, both the oxidation and reduction peak currents increase gradually with each scan, indicating the progressive growth of the PTCB film. After 10 CV cycles, a continuous PTCB membrane with a highly crosslinked structure is formed on the CNT/Nylon-66 support. SEM images (Fig. 1c, d) reveal that the PTCB membrane has a smooth surface morphology and a dense structure, with a thickness of approximately 150 nm.

a Schematic of the electropolymerization (EP) process and the setup of the three-electrode cell. b Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of 1,3,5-tris(N-carbazolyl)benzene (TCB) electropolymerization at a scan rate of 25 mV s-1. c SEM image showing the surface morphology of the PTCB membrane. d SEM image showing the cross section of the PTCB membrane. e Contact angles of the PTCB membrane with various organic solvents-acetone (Ac), ethanol (EtOH), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol (MeOH), and water. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). f Zeta potential of the PTCB membrane in buffered aqueous solutions. g Surface conductivity of the CNT/Nylon-66 support and the PTCB membrane. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The surface properties of the OSN membranes, including contact angle and zeta potential, were investigated. The contact angle was measured to assess the wettability of PTCB membranes with various organic solvents (Fig. 1e). The contact angle increases in the order of acetone, ethanol, DMF, methanol, and water, indicating that solvents with lower polarity exhibit better compatibility with the membrane. Zeta potential measurements revealed that the membrane carries a negative charge (−28.3 to −32.2 mV) in the pH range of 6.1–6.9 (Fig. 1f). Additionally, the membrane’s conductivity is a crucial factor for evaluating its feasibility for voltage-controlled OSN process. The PTCB membrane exhibits an electronic conductivity of 1.44 S cm−1 (Fig. 1g), which falls within the conductivity range of semiconductors (10−8 to 102 S cm-1)42, making it suitable as an electrode in the voltage-controlled OSN tests.

OSN performance of PTCB membranes under applied voltage

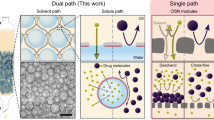

The PTCB membranes were tested in a dead-end setup for OSN. The conductive PTCB membrane functioned as the working electrode, while the cell shell acted as the counter electrode. As shown in Fig. 2a, voltage was applied directly to the membrane to modulate the electric potential and charge density on its surface (see details in Fig. S3).

a Schematic illustration of voltage-controlled OSN test, with the PTCB membrane serving as the working electrode, and the chemical structures of the dye molecules used in the experiment. The molecular structures of the dyes used in this study-methylene blue (MB, cationic), methyl orange (MO, anionic), crystal violet (CV, cationic), and the neutral dye Sudan IV (SIV)-are shown. b Molecular electrostatic potential maps of the organic solvents tested in this study-acetone (Ac), ethanol (EtOH), methanol (MeOH), and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). c Pure organic solvent permeance of the PTCB membrane under different applied voltages, ranging from 0 V to −5 V for negative voltages and from 0 V to 5 V for positive voltages. Filled and open markers represent the first and second test cycles, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3. d MB rejection in ethanol as a function of the applied voltage to the membrane. e Reversible changes in the rejection of the PTCB membrane for CV in methanol as the applied voltage switches between 0 and 3 V. f Rejection behavior of dye molecules with positive and negative charges in methanol as a function of voltage applied to the membrane. All feed solutions contain 50 ppm of dye.

First, we investigated the effect of applying voltage to the membrane on the permeance of pure organic solvents, including methanol, ethanol, acetone, and DMF (Fig. 2b, c). When applying a negative voltage, stepping from 0 V to −5 V, the permeance continuously decreases. We attribute this change to the distribution of electrons (Fig. 2b) within the molecules. For all organic solvents studied, the oxygen atom carries a significant partial negative charge due to its high electronegativity, while the positive charge is more distributed across the rest of the molecule, resulting in a lower charge density compared to the negative charge on the oxygen. Under a negative electric potential, repulsive interactions dominate, which explains the permeance behavior. Our study provides experimental evidence that negative electric potential can influence the transport of neutrally charged molecules in a membrane, a finding further supported by the results in later sections, where the neutral dye SIV exhibits higher rejection under a negative voltage compared to the condition with no applied voltage, and lower rejection under a positive voltage. On the other hand, when a positive voltage is applied from 0 V to 3 V, the permeance remains unchanged. However, as the voltage increases beyond 3 V to 5 V, it begins to decrease, which may be due to the viscoelectric effect43,44 that leads to higher viscosity at increased voltage. All tests were cycled twice to ensure that the permeance changes were not influenced by external experimental factors.

To study the effect of voltage application on rejection, we tested membrane rejection of dye solutions containing dyes with different charges and molecular weights, including methylene blue (MB, positively charged, 319.9 Da), methyl orange (MO, negatively charged, 327.33 Da), Sudan IV (SIV, neutral, 380.44 Da), and crystal violet (CV, positively charged, 407.99 Da), in various organic solvents.

Figure 2d shows the membrane rejection of MB, a positively charged molecule, under different applied voltages. From 0 to 2 V, the membrane’s rejection of MB increases significantly from 13% to 80%. Interestingly, when the voltage is returned to 0 V, the rejection drops back to 10%. This result indicates that a strong electrostatic repulsion effect can be achieved between the charged membrane and the molecules. We also conducted cyclic tests, where the voltage was switched on and off successively during filtration. As shown in Fig. 2e, for CV in methanol, the rejection exhibits clear switching behavior with the applied voltage and remains stable over three cycles. At 0 V, the rejection is around 86%, while a voltage of 3 V corresponds to a rejection of approximately 96%. A similar result was observed for MB in ethanol (Fig. S6). These results indicate the potential for in situ regulation of molecular transport in OSN under an applied voltage.

Next, we verified the voltage-controlled enhancement of rejection for dyes with different charges. We tested the rejection using three dyes: MB, MO, and SIV, which are positively, negatively, and neutrally charged, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2f, the rejection of MB increases significantly (from 13.2% to 80.2%) when a positive voltage is applied to the membrane. In comparison, it decreases when a negative voltage is applied (from 29.3% to 10.1%). For MO, the rejection also increases under a negative voltage (from 34.5% to 81.0%). Notably, all these changes in rejection are reversed when the voltage is turned off. For neutral SIV, the rejection increases slightly under a negative voltage and decreases under a positive voltage. This behavior is likely due to the uneven distribution of charge density, particularly the high electronegativity of oxygen and nitrogen atoms, which leads to an overall repulsion effect when interacting with a negatively charged membrane.

Dual-barrier mechanism for voltage-enhanced solute rejection

After confirming the effectiveness of the voltage-controlled approach for rejection enhancement in OSN, we then aimed to: (1) investigate the membrane’s rejection response to different applied voltage magnitudes, and (2) examine the influence of various solvents and solutes on the effectiveness of voltage-assisted rejection enhancement.

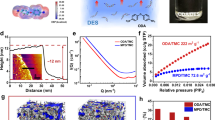

Figure 3a illustrates that increasing the voltage magnitude leads to higher solute rejection for all dyes in methanol. Specifically, as the applied voltage increases stepwise from 0 V to 5 V (positive potential for MB and CV, negative potential for MO), the rejection of MB, MO, and CV in methanol increases incrementally from 8.3%, 50.0%, and 93.6% to 91.3%, 97.4%, and 99.1%, respectively. Similar trends are found for MB (Fig. 3b) and MO (Fig. 3c) in various solvents.

a Rejection of methylene blue (MB), methyl orange (MO), and crystal violet (CV) in methanol as a function of applied voltage (0−5 V). A negative voltage is applied for MO, while a positive voltage is applied for MB and CV. b Rejection of MB in various organic solvents under applied voltages of 0−5 V. c Rejection of MO in various organic solvents under applied voltages of 0−5 V. d Schematic of the voltage-controlled OSN system using MB as a model solute. An electric field is established in the bulk solution under the applied voltage, analogous to a supercapacitor configuration. e Chronoamperometric response of the membrane in a 50 ppm MB methanol solution under different applied voltages, indicating electric double layer (EDL) charging and steady-state leakage current. f Membrane charge density and leakage current in a 50 ppm MB methanol solution under different applied voltages. g Schematic illustration of two solute states in organic solvents: contact ion pair (CIP) and solvent-separated ion pair (SSIP), with yellow ellipses representing solvent molecules. h Optimized geometries of MB in the CIP state in methanol (left) and acetone (right), with distances between the chloride ion and the nearest atom on the MB cation indicated.

Owing to the distinct, case-dependent characteristics of the feed solutions, comprising various organic solvents and low concentrations of small organic molecules, and the unique structural features of the CMP membrane as an electrode, the factors influencing solute rejection are not straightforward. To aid understanding, the voltage-controlled OSN system can be viewed as analogous to a non-classical supercapacitor, as illustrated in Fig. 3d using MB as an example.

In solution, MB dissociates into MB+ and Cl- ions, while the membrane is held at a positive potential and serves as the working electrode. Before permeating the membrane, the dissociated MB+ ions (the target species to be rejected) encounter two electrostatic barriers. Barrier 1 originates from ion migration in the bulk feed solution, where the electric field between the two electrodes drives MB⁺ away from the membrane surface. This process is dependent on the solute dissociation in the bulk solution. Barrier 2 corresponds to a Donnan-like effect at the feed-membrane interface, representing a thermodynamic exclusion due to the charges on the membrane matrix. In a classical Donnan effect, the membrane charge density is fixed by the density of permanently charged functional groups. In contrast, in a voltage-controlled system, the effective charge density is influenced by solute dissociation in the bulk solution and the enhanced charge density at the membrane interface in the electric field, leading to the formation of enhanced electric double layer (EDL), which will be discussed in detail in later sections. Therefore, this exclusion phenomenon is referred to as a Donnan-like effect rather than a classical Donnan effect.

To investigate how these two barriers influence membrane rejection under an applied voltage, it is essential to quantify the membrane surface charge density and the steady-state current in the circuit. Therefore, chronoamperometry (CA) measurements were conducted using MB and MO solutions in different organic solvents (Figs. 3e and S7). As shown in Fig. 3e, a voltage step from 0 V to 1–5 V was applied, and the resulting current response was recorded as a function of time. The initial sharp current spike, followed by a rapid decay, corresponds to membrane charging, during which chloride ions migrate into the membrane pores to form the EDL. After this transient process, once the membrane surface becomes saturated, the current stabilizes at a steady plateau that reflects the leakage (ohmic) current typically observed in supercapacitors.

It is well known that the membrane charge density directly determines the Donnan potential. By integrating the initial current during the EDL charging process shown in Figs. 3e and S7, we obtained the membrane charge density (\({{{\rm{\sigma }}}}\)), as presented in Figs. 3f and S7. For all solute-solvent pairs, increasing the applied voltage from 1 V to 5 V leads to a rapid rise in \({{{\rm{\sigma }}}}\) at low voltages, followed by a plateau at higher voltages. This saturation behavior originates from counterion crowding within the PTCB pores, which limits further counterion migration and suppresses additional EDL charging at higher voltages. Such a phenomenon is typical of nanoporous electrodes45. This observation is further supported by the cyclic voltammetry (CV) results shown in Fig. S8. At lower voltages, the CV curves exhibit a tilted rectangular shape, characteristic of capacitive behavior associated with EDL charging. At higher voltages, the current increases almost linearly with voltage, indicating that EDL charging has reached saturation, and additional voltage is mainly dropped across the bulk solution as ohmic resistance.

On the other hand, the steady-state leakage current observed in the CA curves (Fig. 3e) reflects the migration rate of MB⁺ ions in the bulk solution under different applied voltages, since the current in the bulk is carried solely by ions. As shown in Figs. 3f and S7, this current exhibits a linear voltage dependence, indicating that the migration of MB⁺ away from the membrane increases proportionally with the applied voltage.

To quantitatively distinguish the respective contributions of the Donnan-like effect and ion migration to solute rejection enhancement, a detailed mathematical model and data-fitting procedure are presented in SI Note S2, titled “Mathematical relationships between applied voltage and solute rejection, and experimental fitting.” The model, based on membrane charge density and leakage current data, accurately predicts the membrane’s solute rejection as a function of applied voltage, using only a few fitting parameters.

Solute dissociation as a key factor in voltage-enhanced OSN performance

As shown in Fig. 3b, c, as the voltage increases, the rejection trends depend strongly on the solvent environment. Most dye-solvent systems display a gradual increase in rejection with voltage; however, three pairs deviate from this trend: MB in acetone, MO in DMF, and MO in acetone. For MB in acetone and MO in DMF, rejection decreases with increasing voltage, while for MO in acetone, the rejection dropped so sharply that further measurements were not feasible. These intriguing deviations prompted us to investigate the underlying mechanisms: why does voltage enhance rejection in some solvent systems but not in others? Gaining this understanding is also crucial for practical applications, as it allows us to predict whether voltage-controlled OSN will be effective for a specific real-case system.

A natural hypothesis is that these variations arise from differences in solute dissociation across solvents. We hypothesize that dissociation influences rejection through two main mechanisms. First, the extent of dissociation is expected to determine how the applied voltage is distributed between the EDL and the bulk solution, thereby shaping the local electric field (illustrated in Fig. S11 and Note S3). Second, only dissociated ionic species are likely to experience electrostatic repulsion in both the bulk solution and the EDL, whereas undissociated neutral molecules do not, and may even be attracted to the charged membrane surface through induced dipole interactions.

The dissociation of solutes in organic solvents can be understood through the framework of solute partitioning among different species-free ions, solvent-separated ion pairs (SSIPs), contact ion pairs (CIPs), and aggregates (AGGs), as illustrated in Fig. 3g. Free ions and SSIPs can be regarded as dissociated species that act as charge carriers, whereas CIPs and AGGs are effectively undissociated. To understand how solvent properties govern the dissociation behavior of small organic molecule salts, using MB and MO as examples, a systematic study was conducted through density functional theory (DFT), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and experiments. DFT studies provide a molecular-level picture of the solvation and speciation of MB and MO. Geometry optimizations for the CIP and SSIP of MB and MO in different organic solvents were performed (Figs. 3h and S19–26). As shown in Figs. 3h and S19–21, although the initial distance between the cation and anion was set the same across all solvents in the CIP structure, after optimization, the distance between the chloride ion and the closest atom on the cation significantly increases in methanol and ethanol, while remaining very close in acetone. Similar results were also observed for MO (Fig. S22–24). Additionally, we calculated the free energy for the transition from CIPs to SSIPs for MB in different organic solvents. As shown in Fig. S27, the free energy difference in acetone is much higher than in the other solvents, indicating a greater energetic barrier for MB to dissociate into SSIPs. We further employed FTIR spectroscopy to provide direct evidence for the differences in solvent-solute interactions across various solvents, results and descriptions are shown in Fig. S28 and Note S6. Both the simulation and experimental results consistently indicate that the dissociation degree of MB and MO in alcohols is significantly higher than in acetone.

MD simulations were performed to confirm the role of solute dissociation in Donnan-like equilibrium at the feed-membrane interface (Fig. S29). Systems were constructed using methanol (Fig. S29a, b) and acetone (Fig. S29c, d) as solvents. In methanol under neutral membrane conditions (Fig. S29a), MB+ and Cl− dissociate effectively to form SSIPs, where electrostatic repulsion between co-ions prevents MB+ aggregation and van der Waals interactions allow some MB+ adsorption onto the membrane surface. When the PTCB membrane is positively charged (Fig. S29b), Cl- are enriched in the PTCB membrane, and co-ions (MB+) are depleted, indicating a pronounced Donnan-like equilibrium that enhances MB+ rejection. In contrast, in acetone, regardless of the membrane charge state (neutral, Fig. S29c; or positively charged, Fig. S29d), poor solute dissociation eliminates like-charge electrostatic repulsion, allowing MB⁺·Cl- pairs to agglomerate into larger clusters in solution. Correspondingly, the number density profiles of MB+ and Cl- along the z-direction (Fig. S30) show that in methanol under positive voltage (Fig. S30b), MB+ is effectively excluded from the membrane surface, whereas in acetone (Fig. S30d), the MB+ distribution remains largely unaffected by membrane charge.

Voltage-controlled OSN for selective separation of dye mixtures, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals

As demonstrated by the results, applying voltage to the PTCB membrane significantly alters the rejection of charged molecules in organic solvents, enabling the selective separation of mixtures that are otherwise difficult to separate. We chose a mixture of MO and MB in methanol (50 ppm for each dye), because the two dyes have similar molecular weights but opposite charges, making their separation particularly challenging. As shown in Fig. 4a, when no voltage is applied (0 V), the rejection for MO and MB are 82.4% and 43.2%, respectively. However, when a 5 V positive voltage is applied to the PTCB membrane, the rejection of MO reaches nearly 100%. At the same time, the rejection of MB slightly decreases, showing a negative rejection due to the electrostatic attraction with the membrane. The corresponding permeate color changes during filtration, as shown in Fig. 4b. At 5 V, less MO and more MB pass through the membrane compared to 0 V, resulting in a shift from green to blue in the permeate color.

a UV-vis spectra of the permeate solutions at different applied voltages during the separation of methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) mixtures. b Corresponding color change during filtration. c Chemical structures of selected pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. d Rejection of the pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals before and after applying voltage. The applied voltages were 5 V for BAC and 3 V for PB, PQ, and DQ.

Moreover, to demonstrate the broad applicability of the voltage-controlled OSN process, several widely used pharmaceuticals including benzalkonium chloride (BAC) and pyridostigmine bromide (PB), as well as agrochemicals such as paraquat (PQ) and diquat (DQ), were dissolved in methanol and tested for membrane rejection before and after voltage application (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 4d, the rejection of all four solutes significantly increases upon applying voltage, highlighting the strong potential of voltage-controlled OSN for diverse separation applications.

Discussion

In this work, conductive CMP membranes (PTCB/CNT/Nylon-66) were fabricated for voltage-controlled OSN processes. The rejection of dye molecules was significantly enhanced by applying voltage in situ. In methanol, the rejection of positively charged MB and CV increased from 8.3% and 93.6% at 0 V to 91.3% and 99.1% at 5 V when a positive voltage was applied to the membrane. Similarly, when a negative voltage was applied, the rejection of MO increased from 50% at 0 V to 97.4% at −5 V. We demonstrated that the varying dissociation degrees of dyes in different organic solvents contribute to their distinct behaviors, and the voltage-gated OSN process is expected to work primarily for organic solvents with hydrogen bonds or high polarity. Other interesting phenomena include the differing responses of neutrally charged solvent and solute transport under positive and negative charges on the membrane surface, due to the uneven distribution of electron density on molecules. In conclusion, this work introduces an approach for in situ enhancement of OSN rejection performance and shows great potential in applications such as gradient separation of multiple organic mixtures and the recovery of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals.

Methods

Materials

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs, diameter: 0.78 nm, median length: 1 µm, ≥95%), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, ≥98%), 1,3,5-tris(N-carbazolyl) benzene (TCB, >97%), tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6, ≥99%), diquat dibromide monohydrate (DQ, analytical standard), methylene blue (MB, ≥82%, MW = 319.9 g mol−1), methyl orange (MO, 85%, MW = 327.33 g mol−1), Sudan IV (SIV, ≥80%, MW = 380.44 g mol−1) and crystal violet (CV, ≥90%, MW = 407.98 g mol−1) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Dichloromethane (DCM, >99.8%), acetonitrile (ACN, >99.9%), methanol (>99.8%), ethanol (>99.8%), and acetone (>99.5%) were supplied by Aik Moh Paints & Chemicals Pte Ltd. Pyridostigmine Bromide (PB, >98%) was purchased from Aladdin Scientific. Paraquat dichloride hydrate (PQ, 98%) and Benzalkonium Chloride (BAC, >95%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Commercial Nylon-66 membrane substrates (pore size: 0.22 μm) were purchased from Qiguanchao Tech.

Fabrication of the CNT/Nylon-66 supports

The SWCNT dispersion was prepared by mixing 8 mg of SWCNT powder and 400 mg of SDS in 200 ml of deionized (DI) water, followed by sonication for 4 h at 40 W using a probe sonicator. To remove undispersed SWCNTs, the dispersion was centrifuged three times at 13,400 × g (10,000 rpm, rotor radius = 12 cm) for 1 h each time. The CNT/Nylon-66 substrate was then prepared by filtering 10 ml of the collected SWCNT supernatant onto a commercial Nylon-66 membrane with an effective diameter of 35 mm. The as-prepared CNT/Nylon-66 substrate was washed with DI water three times, each for 10 min, dried overnight at room temperature under vacuum, and then used directly as the substrate for subsequent electropolymerization. The morphology of the CNT/Nylon-66 substrate is shown in Fig. S2.

Electropolymerization process to prepare PTCB membranes

The conductive membrane was fabricated by electropolymerization of 1,3,5-tris(N-carbazolyl) benzene (TCB) on the surface of the CNT/Nylon-66 substrate (Fig. 1a), in a three-electrode system connected to an electrochemical workstation (AUTOLAB, PGSTAT302N). The titanium metal plate, Ag/AgCl electrode, CNT/Nylon-66 substrate were used as the counter, reference, and working electrodes, respectively. The electrolyte solution was prepared by dissolving TCB monomer (0.2 mM) and TBAPF6 (0.1 M) in a solvent mixture consisting of DCM and ACN (3/2, v/v). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was conducted over a voltage range of 0 to 1.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl with a scan rate of 25 mV s−1, running for 10 cycles. The as-prepared membranes were immersed in the mixed solvent (DCM/ACN, 3/2, v/v) to completely remove the supporting electrolyte and unreacted monomers. The membranes were then dried overnight at room temperature under vacuum before being used for separation tests.

Evaluation of voltage-controlled separation performance of PTCB membranes for OSN

The pressure-driven OSN performance under voltage was evaluated using a homemade stainless steel dead-end cell equipped with a suspension stirrer to reduce concentration polarization. One end of a titanium foil strip (10\(\times\)0.5 cm2) was fixed to the surface of the conductive PTCB membrane with adhesive tape. The foil was placed outside the testing area, with the other end connected to the external electrode. The middle section, which was in contact with the cell, was wrapped in polyethylene (PE) film to prevent short-circuiting (see details in Fig. S3). A voltage was applied by connecting the titanium foil and the cell shell to the poles of the sourcemeter (Keithley 2400).

Prior to testing, the membrane was stabilized in the cell at a feed pressure of 6 bar by applying N2 for 5 to 6 h. Tests were then conducted at room temperature (~22 °C). The membrane’s effective area, sealed by an O-ring in the dead-end cell, was approximately 0.785 cm². The feed concentration of various dye solutions was 50 ppm. Permeate was collected after a set period and diluted to the linear range of the UV spectrum. Concentration was measured using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Cary 60), and permeance and rejection were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

where \(J\) is the solvent permeance (L m−2 h−1 bar−1), \(V\) is the permeate volume (L), calculated by dividing the permeate weight by the solvent density. \(A\) is the effective testing membrane area (m2), \(t\) is operating time (h) for permeate collection, \(p\) is the applied pressure (bar), \({R}_{i}\) is the solute rejection (%), and \({C}_{F,i}\) and \({C}_{P,i}\) represent the solute concentrations in the feed and permeate solutions, respectively.

Density functional theory

All geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d,p) level of theory, without symmetry constraints. Single-point energies were calculated using the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set, with zero-point energy (ZPE) and thermal corrections applied. A hybrid explicit/implicit solvation model was employed to describe the solvation effect on the dissociation of dyes, explicitly including several solvent molecules. The number of solvent molecules was incrementally increased until it was sufficient to describe the CIP state of the ion pairs. The SMD solvation model was used to account for the solvation effect beyond the first solvation shell implicitly.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data, atomic coordinates of DFT-optimized structures, and initial and final molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory configurations have been deposited in the Zenodo repository and are publicly accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17580899 (ref. 46). All other relevant raw data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The script files used for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations performed with the LAMMPS software are available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17580899 (ref. 46).

References

Nie, L. et al. Realizing small-flake graphene oxide membranes for ultrafast size-dependent organic solvent nanofiltration. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9184 (2020).

Henderson, R. K. et al. Expanding GSK’s solvent selection guide—embedding sustainability into solvent selection starting at medicinal chemistry. Green. Chem. 13, 854–862 (2011).

Lively, R. P. & Sholl, D. S. From water to organics in membrane separations. Nat. Mater. 16, 276–279 (2017).

Marchetti, P., Jimenez Solomon, M. F., Szekely, G. & Livingston, A. G. Molecular separation with organic solvent nanofiltration: a critical review. Chem. Rev. 114, 10735–10806 (2014).

Vandezande, P., Gevers, L. E. M. & Vankelecom, I. F. J. Solvent resistant nanofiltration: separating on a molecular level. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 365–405 (2008).

Zhu, T. et al. A responsive 3D covalent organic framework membrane with tunable pore sizes for molecular sieving. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2505907 (2025).

Lu, Y. et al. Monolayer graphene membranes for molecular separation in high-temperature harsh organic solvents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2111360118 (2021).

Liu, Z., Wang, W., Xie, R., Ju, X.-J. & Chu, L.-Y. Stimuli-responsive smart gating membranes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 460–475 (2016).

Yi, G. et al. Selective molecular separation with conductive MXene/CNT nanofiltration membranes under electrochemical assistance. J. Membr. Sci. 658, 120719 (2022).

Gao, T. et al. Electrically modulated nanofiltration membrane based on an arch-bridged graphene structure for multicomponent molecular separation. ACS Nano 17, 6627–6637 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Improving ion rejection of conductive nanofiltration membrane through electrically enhanced surface charge density. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 868–877 (2019).

Amirilargani, M., Sadrzadeh, M., Sudhölter, E. J. R. & de Smet, L. C. P. M. Surface modification methods of organic solvent nanofiltration membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 289, 562–582 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Solvent-resistant nanofiltration membranes based on multilayered polyelectrolyte complexes. Chem. Mater. 20, 3876–3883 (2008).

Ahmadiannamini, P. et al. Multilayered polyelectrolyte complex based solvent resistant nanofiltration membranes prepared from weak polyacids. J. Membr. Sci. 394-395, 98–106 (2012).

Hua, D. & Chung, T.-S. Polyelectrolyte functionalized lamellar graphene oxide membranes on polypropylene support for organic solvent nanofiltration. Carbon 122, 604–613 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Reduced graphene oxide membranes for ultrafast organic solvent nanofiltration. Adv. Mater. 28, 8669–8674 (2016).

Ahmadiannamini, P. et al. Influence of polyanion type and cationic counter ion on the SRNF performance of polyelectrolyte membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 403-404, 216–226 (2012).

Li, X. et al. Morphology and performance of solvent-resistant nanofiltration membranes based on multilayered polyelectrolytes: study of preparation conditions. J. Membr. Sci. 358, 150–157 (2010).

Van der Bruggen, B., Schaep, J., Wilms, D. & Vandecasteele, C. Influence of molecular size, polarity and charge on the retention of organic molecules by nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 156, 29–41 (1999).

Lai, X., Wang, C., Wang, L. & Xiao, C. A novel PPTA/PPy composite organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) membrane prepared by chemical vapor deposition for organic dye wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 45, 102533 (2022).

Yuan, J. et al. Oriented ionic covalent organic framework membranes for efficient organic solvent nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 688, 122120 (2023).

Xu, M. et al. Charged boron nitride nanosheet membranes for improved organic solvent nanofiltration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 12524–12533 (2023).

Duong, P. H. et al. Mechanistic study of pH effect on organic solvent nanofiltration using carboxylated covalent organic framework as a modeling and experimental platform. Sep. Purif. Technol. 282, 120028 (2022).

Lu, Y., Liu, W., Liu, J., Li, X. & Zhang, S. A review on 2D porous organic polymers for membrane-based separations: processing and engineering of transport channels. Adv. Membr. 1, 100014 (2021).

Sarihan, A. et al. Exploiting the electrical conductivity of poly-acid doped polyaniline membranes with enhanced durability for organic solvent nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 579, 11–21 (2019).

Jones, H. C. The Electrolytic dissociation of certain salts in methyl and ethyl alcohols, as measured by the boiling-point method. Z. Phys. Chem. 31U, 114–141 (1899).

Murray-Rust, D. M. & Hartley, H. B. The dissociation of acids in methyl and in ethyl alcohol. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 126, 84–106 (1997).

Fulfer, K. D. & Kuroda, D. G. Ion speciation of lithium hexafluorophosphate in dimethyl carbonate solutions: an infrared spectroscopy study. PCCP 20, 22710–22718 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Dominant solvent-separated ion pairs in electrolytes enable superhigh conductivity for fast-charging and low-temperature lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 18, 8350–8359 (2024).

Xing, L. et al. Deciphering the ethylene carbonate–propylene carbonate mystery in Li-ion batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 282–289 (2018).

Lee, H. et al. Why does dimethyl carbonate dissociate Li salt better than other linear carbonates? Critical role of polar conformers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 10382–10387 (2020).

Nackaerts, R., De Maeyer, M. & Hellemans, L. Field dissociation effect on ion-pairs in a non-polar medium. J. Electrost. 7, 169–186 (1979).

Onsager, L. Deviations from Ohm’s law in weak electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 2, 599–615 (1934).

Park, J. K., Ryu, J. C., Kim, W. K. & Kang, K. H. Effect of electric field on electrical conductivity of dielectric liquids mixed with polar additives: DC conductivity. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 12271–12276 (2009).

Liang, B. et al. Microporous membranes comprising conjugated polymers with rigid backbones enable ultrafast organic-solvent nanofiltration. Nat. Chem. 10, 961–967 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. Precise sub-angstrom ion separation using conjugated microporous polymer membranes. Acs Nano 15, 11970–11980 (2021).

Zhou, Z. et al. Flexible ionic conjugated microporous polymer membranes for fast and selective ion transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2108672 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Electropolymerization of robust conjugated microporous polymer membranes for rapid solvent transport and narrow molecular sieving. Nat. Commun. 11, 5323 (2020).

Lu, Y., Liu, W., Wang, K. & Zhang, S. Electropolymerized thin films with a microporous architecture enabling molecular sieving in harsh organic solvents under high temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 20101–20110 (2022).

Jia, Y. et al. Control of microporous structure in conjugated microporous polymer membranes for post-combustion carbon capture. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2407499 (2024).

Guo, D. et al. Electropolymerized conjugated microporous nanoskin regulating polysulfide and electrolyte for high-energy Li–S batteries. ACS Nano 14, 17163–17173 (2020).

Sharaf, S. M. In Advances in Functional and Protective Textiles (eds Shahid ul-Islam & Bhupendra Singh Butola) 141-167 (Woodhead Publishing, 2020).

Duff, A. W. The viscosity of polarized dielectrics. Phys. Rev. 4, 23–38 (1896).

Hao, T. Viscosities of liquids, colloidal suspensions, and polymeric systems under zero or non-zero electric field. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 142, 1–19 (2008).

Kondrat, S., Georgi, N., Fedorov, M. V. & Kornyshev, A. A. A superionic state in nano-porous double-layer capacitors: insights from Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 11359–11366 (2011).

Jia, Y. et al. Dataset for “Voltage-Controlled Organic Solvent Nanofiltration Using Conjugated Microporous Polymer Membranes.” (Zenodo, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from Cambridge Centre for Carbon Reduction in Chemical Technology Phase 2 (C4T2, A-0005328-01-00; received by S.Z.), Ministry of Education of Singapore (A-0009181-00-00; received by S.Z.) and Jiangsu Future Membrane Technology Innovation Center (BM2021804). This work was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 22078289; received by P.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D., Y.J. and S.Z. designed the research. J.D., Y.J., P.L. and S.Z. conducted the experiments and data analysis. Y.J. performed the DFT calculations, MD simulations, and mathematical modelling. Y.L. and C.F. assisted in the OSN tests. The paper was prepared by Y.J. and J.D., and reviewed by P.L. and S.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Y., Du, J., Lu, Y. et al. Voltage-controlled organic solvent nanofiltration using conjugated microporous polymer membranes. Nat Commun 17, 236 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66941-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66941-z

This article is cited by

-

Voltage-controlled organic solvent nanofiltration using conjugated microporous polymer membranes

Nature Communications (2025)